Advantages and Disadvantages of Interview in Research

Approaching the Respondent- according to the Interviewer’s Manual, the introductory tasks of the interviewer are: tell the interviewer is and whom he or she represents; telling him about what the study is, in a way to stimulate his interest. The interviewer has also ensured at this stage that his answers are confidential; tell the respondent how he was chosen; use letters and clippings of surveys in order to show the importance of the study to the respondent. The interviewer must be adaptable, friendly, responsive, and should make the interviewer feel at ease to say anything, even if it is irrelevant.

Dealing with Refusal- there can be plenty of reasons for refusing for an interview, for example, a respondent may feel that surveys are a waste of time, or may express anti-government feeling. It is the interviewer’s job to determine the reason for the refusal of the interview and attempt to overcome it.

Conducting the Interview- the questions should be asked as worded for all respondents in order to avoid misinterpretation of the question. Clarification of the question should also be avoided for the same reason. However, the questions can be repeated in case of misunderstanding. The questions should be asked in the same order as mentioned in the questionnaire, as a particular question might not make sense if the questions before they are skipped. The interviewers must be very careful to be neutral before starting the interview so as not to lead the respondent, hence minimizing bias.

listing out the advantages of interview studies, which are noted below:

- It provides flexibility to the interviewers

- The interview has a better response rate than mailed questions, and the people who cannot read and write can also answer the questions.

- The interviewer can judge the non-verbal behavior of the respondent.

- The interviewer can decide the place for an interview in a private and silent place, unlike the ones conducted through emails which can have a completely different environment.

- The interviewer can control over the order of the question, as in the questionnaire, and can judge the spontaneity of the respondent as well.

There are certain disadvantages of interview studies as well which are:

- Conducting interview studies can be very costly as well as very time-consuming.

- An interview can cause biases. For example, the respondent’s answers can be affected by his reaction to the interviewer’s race, class, age or physical appearance.

- Interview studies provide less anonymity, which is a big concern for many respondents.

- There is a lack of accessibility to respondents (unlike conducting mailed questionnaire study) since the respondents can be in around any corner of the world or country.

INTERVIEW AS SOCIAL INTERACTION

The interview subjects to the same rules and regulations of other instances of social interaction. It is believed that conducting interview studies has possibilities for all sorts of bias, inconsistency, and inaccuracies and hence many researchers are critical of the surveys and interviews. T.R. William says that in certain societies there may be patterns of people saying one thing, but doing another. He also believes that the responses should be interpreted in context and two social contexts should not be compared to each other. Derek L. Phillips says that the survey method itself can manipulate the data, and show the results that actually does not exist in the population in real. Social research becomes very difficult due to the variability in human behavior and attitude. Other errors that can be caused in social research include-

- deliberate lying, because the respondent does not want to give a socially undesirable answer;

- unconscious mistakes, which mostly occurs when the respondent has socially undesirable traits that he does not want to accept;

- when the respondent accidentally misunderstands the question and responds incorrectly;

- when the respondent is unable to remember certain details.

Apart from the errors caused by the responder, there are also certain errors made by the interviewers that may include-

- errors made by altering the questionnaire, through changing some words or omitting certain questions;

- biased, irrelevant, inadequate or unnecessary probing;

- recording errors, or consciously making errors in recording.

Bailey, K. (1994). Interview Studies in Methods of social research. Simonand Schuster, 4th ed. The Free Press, New York NY 10020.Ch8. Pp.173-213.

Sociology Group

The Sociology Group is an organization dedicated to creating social awareness through thoughtful initiatives like "social stories" and the "Meet the Professor" insightful interview series. Recognized for our book reviews, author interviews, and social sciences articles, we also host annual social sciences writing competition. Interested in joining us? Email [email protected] . We are a dedicated team of social scientists on a mission to simplify complex theories, conduct enlightening interviews, and offer academic assistance, making Social Science accessible and practical for all curious minds.

- How it works

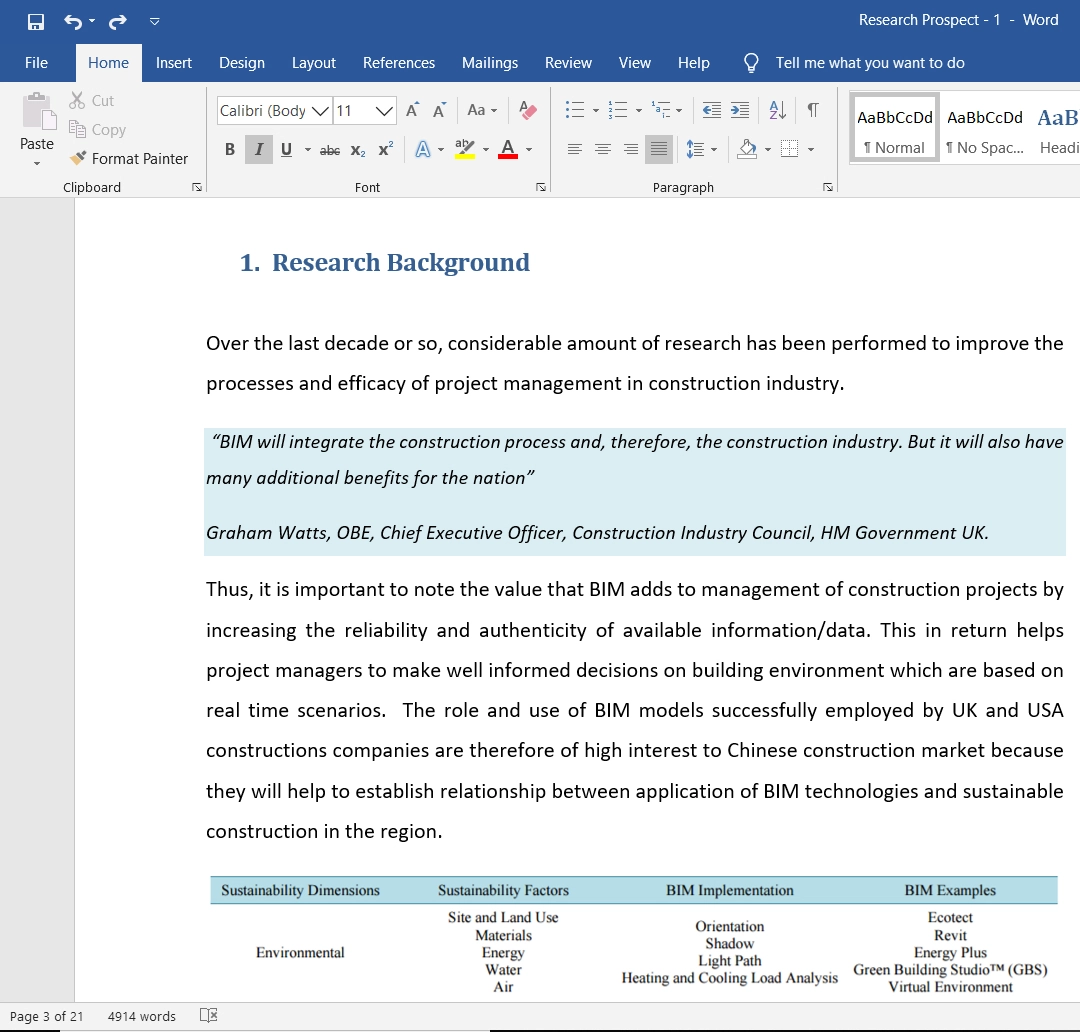

Advantages of Primary Research – Types & Advantages

Published by Jamie Walker at October 21st, 2021 , Revised On August 29, 2023

Are you confused between primary and secondary research ? Not sure whether primary research is the right choice for your research project? Don’t panic! This article provides the key advantages of primary research over secondary research so you can make an informed decision.

Primary research is a data collection method where the researcher gathers all the data him/herself without relying on data acquired in previous studies. That means the collected data can be used to investigate a specific problem or a relationship between different variables.

To carry out primary research, a profound analysis is required, which is one of the reasons why primary research tends to be so valuable.

There are many different types of primary research that can be performed, and it is essential to know the differences between them so you can be sure that you are choosing the right method for your research.

Some of the most common primary research methods include surveys, interviews, ethnographic research, and observations.

Primary research is a valuable research tool that allows researchers and academicians to improve the reliability and validity of their research. It not only facilitates your research work but also enables you to make a mark in your area of study. It is most commonly used when writing a dissertation, thesis, report, journal paper or business report.

Primary research provides researchers with a rich source of in-depth knowledge about a particular research topic. For example, a focus group asks specific questions about a topic. It guides the researcher in drafting their research questions and creating other tools for research.

This makes the material highly tailored to the needs of the primary researcher. Similarly, a survey will enable you to collect responses from the participants of the study against your research questions.

To read about the advantages of secondary research

To read about the disadvantages of secondary research

To read about the disadvantages of primary research .

Types of Primary Research

Primary research must be conducted where secondary data is irrelevant or insufficient and where real first hand data is required. There are four specific forms that researchers use for primary research.

- Interviews: Conduct the interview with the participants in small sitting using interview guide

- Focus group discussions: Conduct small groups for discussion on a particular topic.

- Surveys: Using a brief questionnaire, participants were asked about their thoughts about the specific topic.

- Observations: Observing and reckoning the surroundings, for example, people and other phenomena that can be observed.

Hire an Expert Researcher

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in academic style

- 100% Plagiarism free & 100% Confidential

- Never resold

- Include unlimited free revisions

- Completed to match exact client requirements

Advantages of Primary Research

- The data is drawn from first-hand sources and will be highly accurate and, perhaps that is the most significant advantage of primary research. The questions or experimental set-ups can be constructed as a unique method to achieve the research objectives.

- Doing so, ensures that the data you gather is related and relevant to the research you are conducting and is intended to address your research objectives.

- Primary research ought to be directed towards addressing the core problem or objective of the research study. In other words, there is a clearly defined problem and the design of the research, the data collection methods and the final data set can all be tailored to that problem.

- You can be sure that the collected data is aligned with your specific problem, improving the probability that the data will give you the desired responses. In other words, the data you will gather for your research will be concrete and unambiguous, and directly related to your research objectives.

- With primary data collection, you don’t need to modify the data collected (secondary data), by another researcher who may have a slightly different focus, because you are the owner of your own data.

- Maintaining this degree of scrutiny means that the data you collect from primary sources will be more pertinent and therefore more effective for your research. Since you will be in charge of the data, it is easier to regulate the time span, the scope and the volume of the dataset being used.

The main emphasis of primary research will be on the research topic . This research approach enables the researcher to address the problem and find the most appropriate responses. Moreover, this method is valid and has been tested thousands of times, which makes its use more reliable and increases the probability of obtaining valid data.

Once you understand the nature of primary research and what it entails, you can begin to understand the requirements of your own research project and discover how to locate the specific type of data that you need in order to address your research questions and prepare the best possible research work.

Need Help with Primary Research?

If you are a student, a researcher, or a business looking to collect primary data for a report, a dissertation, an essay, or another type of project, feel free to get in touch with us. You can also read about our primary data collection service here . Our experts include highly qualified academicians, doctors, and researchers who are sure to collect authentic, reliable, up to date and relevant sources for your research study.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to perform primary research.

Performing primary research involves:

- Defining research goals.

- Choosing methods (surveys, interviews, etc.).

- Designing tools and questions.

- Collecting data from sources directly.

- Analyzing data for insights.

- Drawing conclusions based on findings.

You May Also Like

Thematic analysis is commonly used for qualitative data. Researchers give preference to thematic analysis when analysing audio or video transcripts.

Action research for my dissertation?, A brief overview of action research as a responsive, action-oriented, participative and reflective research technique.

In correlational research, a researcher measures the relationship between two or more variables or sets of scores without having control over the variables.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

What Are The Benefits Of Using Interviews In Research?

by Julie Clements | Last updated May 11, 2023 | Published on Nov 5, 2021 | Interview Transcription

Research entails the collection and analysis of data to address a research question. Researchers usually collect both primary and secondary data. Primary research involves the first-hand collection of data directly from the source, while secondary research relies on existing data from previously gathered sources. Interviews are a significant source of primary data, and an academic transcription service provider can capture crucial details of these interactions, facilitating the extraction of in-depth data necessary for the study. Let’s look into the nature of research interviews and their advantages.

The Research Interview Process

Research interviews involve the interviewer and the interviewee or respondent. In market research, interviews are usually conducted to gather data related to consumer preferences, opinions, and behaviors. Academic research interviews are used as a qualitative research method to collect detailed information pertaining to the research topic from individuals or groups in the target population in order to understand their experiences, perspectives, and behaviors. Field surveys are one of the most effective ways to collect primary data through interviews. Questions and responses can be oral or written, depending on the requirement and situation.

Interviews can be conducted through various means, including telephone, in-person, or via video in a face-to-face format. In today’s digital era, there are efficient online survey tools available for conducting field research surveys. Video conferencing interviews, coupled with research transcription services , have emerged as a viable option for qualitative research, enabling researchers to reach a larger pool of participants without the need for travel. Platforms like Zoom provide a cost-effective and convenient alternative to traditional in-person interviews, offering researchers flexibility and ease of use.

Is transcription holding up your research work ? Connect with our online transcription company for accurate and timely transcription services !

Research Interview Methods

The goal of academic research interviews is to obtain rich, nuanced data that can provide insights into complex social phenomena or contribute to theory development. To gain in-depth understanding of their perspectives or exqperience, researchers select participants based on specific criteria, such as their expertise, experience, or demographic characteristics. For instance, in oral history projects, interviews are used to understand people’s testimony about their own lived experiences in a particular period in the past or get information about a historically relevant event that they witnessed.

Academic research interviews may involve open-ended or semi-structured questioning techniques. The main types of interviews that researchers use include:

Direct and indirect : The direct approach involves asking interview questions in a way that the respondent understands the goal of the question and the anticipated response. In indirect interviews, the responder is unaware of the purpose of the questions or the intended response.

Structured and unstructured : Researchers use structured interviews with closed-ended questions in survey research. Structured interviews have a standardized format. As all the respondents are asked the same questions, they maintain uniformity in all the sessions. On the other hand, unstructured interviews offer flexibility as questions are not set, and can be modified based on the respondent’s answers. These interviews are more informal and allow the interviewer to get a better understanding of a situation. Researchers may also use semi-structured interviews which offer some flexibility while following basic research guidelines.

Focus group interviews : This involves interviewing a selected group of people together to gain an understanding of a particular social issue. Conducting focus group interviews require a lot of skill to establish rapport with each respondent and manage and elicit responses from the each person.

Advantages of Interviews for Research

- Allows the researcher to obtain original and unique data directly from a source based on the study’s requirements

- Structured interviews can reach a large section of the target population

- Allows samples to be controlled

- Easy to carry out and obtain reliable results quickly

- Interviews provide a better response than mailed questionnaires, which are useful only for literate respondents

- Asking accurate questions can provide direct and in-depth information about a subject or situation

- Offers flexibility to use different techniques to get the desired information, for e.g., by establishing rapport with the respondents, researchers conducting unstructured interviews can obtain more details without much effort

- Can detect non-response, spontaneity, and biased responses

- Provides non-verbal clues or body language of the interviewee

- In personal face-to-face interviews, questions can be modified to obtain the required information

Online interviews for research offer distinct advantages, including:

- Enables high-quality and in-depth qualitative interviews even when in-person interviews are not feasible.

- Is cost-effective as researchers can obtain quality data without the need for travel to interview participants.

- Allows participants to interact from the comfort of their own homes, providing convenience and flexibility.

- Saves time for both the interviewer and respondent by eliminating the need for travel.

- Potentially generates more honest responses, as respondents may feel more at ease and less nervous compared to in-person interviews.

Preparing the right kind of interview questions for successful primary data collection in qualitative research is important for success. Here are some tips:

- Ask open-ended questions so that respondents can use their own terms when answering them, and not simply ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Keep questions as neutral as possible – don’t use judgmental words that can influence answers. For instance, Instead of: “Is X or Y a better policy”, say: “How effective are X and Y policies at solving the problem”

- Ask one question at a time

- Make sure questions are worded clearly and easy to understand

- Be careful when asking ‘why’ questions as they may make respondents answer defensively.

In both market research and academic research, interviews require careful planning, design, and execution to ensure data validity and reliability. Researchers must establish rapport with participants, develop appropriate interview protocols, and analyze and interpret the collected data rigorously to draw meaningful conclusions. Additionally, ethical considerations, such as obtaining informed consent and protecting participant confidentiality, are important in both market research and academic research interviews.

Research interviews need to be transcribed to capture the content for analysis. This can be a time-consuming process, especially if you need to include spoken words and non-verbal nuances. You need to decide on the level of detail required depending on your research goals. If you are hiring professional transcription services , choose a company that specializes in academic transcription services. Providing specific instructions about your research purposes and associated transcription requirements can help you obtain quality results.

Call (800) 670-2809 ! today to discuss your academic transcription needs! Ask for a Free Trial to test the convenience and quality of our services!

Get accurate transcripts in fast turnaround time and at affordable rates!

Recent Posts

What advantages does lecture transcription bring to learning environments.

Following a prolonged disruption during the pandemic, colleges have predominantly reinstated their in-person courses. However, according to the eighth Annual Changing Landscape of Online Education report released in August 2023, there is a notable preference among...

Interview Transcription Tactics: Best Practices for Efficiency and Accuracy

As a journalist, researcher, content creator, or other professional, conducting interviews to gather firsthand accounts of experiences or opinions is an essential aspect of your work. When it comes to transcribing these interviews, accuracy and efficiency are crucial...

When to Use and When to Avoid Free Transcription Software: A Comprehensive Guide

It becomes clear why business transcription is crucial when you consider the enormous number of notes and takeaways usually generated during business calls. Transcripts can come in handy when the material discussed and reviewed during these daily meetings and...

Charting Progress: The Significance of Data Transcription in Digital Transformation

There's hardly any industry that hasn't been impacted by digitalization. The adoption of digital processes have revolutionized the way organizations operate, enabling them to achieve greater levels of productivity, accuracy, and accessibility. Data transcription plays...

Why You Should be Transcribing Your Instagram Stories and Videos

Embracing media transcription for your Instagram stories and videos ensures that your content is accessible to everyone, including those with hearing impairments or situations where sound isn't an option, fostering inclusivity in your audience engagement. Transcribing...

Related Posts

by Julie Clements | Last updated Feb 16, 2024 | Published on Feb 16, 2024 | Interview Transcription

6 Tips to Transcribe Remote Interviews

by MOS Legal | Last updated Nov 16, 2023 | Published on Aug 1, 2023 | Interview Transcription , Digital Transcription

The prevalence of remote work has increased significantly in recent times. Remote interviews have become a crucial part of the hiring process. Interview transcription services are available to document remote interviews. Transcripts enable hiring managers to review interview highlights or occurrences that are ..

Interviewing Techniques for Assessing Soft Skills: Evaluating Communication, Teamwork, and Adaptability

by Julie Clements | Last updated Nov 16, 2023 | Published on Jul 4, 2023 | Digital Transcription , Interview Transcription

When hiring candidates for a particular role, employers look beyond technical skills. They look for soft skills — those interpersonal and personal attributes that define how we interact with others and navigate the complexities …

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Published on March 10, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

An interview is a qualitative research method that relies on asking questions in order to collect data . Interviews involve two or more people, one of whom is the interviewer asking the questions.

There are several types of interviews, often differentiated by their level of structure.

- Structured interviews have predetermined questions asked in a predetermined order.

- Unstructured interviews are more free-flowing.

- Semi-structured interviews fall in between.

Interviews are commonly used in market research, social science, and ethnographic research .

Table of contents

What is a structured interview, what is a semi-structured interview, what is an unstructured interview, what is a focus group, examples of interview questions, advantages and disadvantages of interviews, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about types of interviews.

Structured interviews have predetermined questions in a set order. They are often closed-ended, featuring dichotomous (yes/no) or multiple-choice questions. While open-ended structured interviews exist, they are much less common. The types of questions asked make structured interviews a predominantly quantitative tool.

Asking set questions in a set order can help you see patterns among responses, and it allows you to easily compare responses between participants while keeping other factors constant. This can mitigate research biases and lead to higher reliability and validity. However, structured interviews can be overly formal, as well as limited in scope and flexibility.

- You feel very comfortable with your topic. This will help you formulate your questions most effectively.

- You have limited time or resources. Structured interviews are a bit more straightforward to analyze because of their closed-ended nature, and can be a doable undertaking for an individual.

- Your research question depends on holding environmental conditions between participants constant.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured interviews. While the interviewer has a general plan for what they want to ask, the questions do not have to follow a particular phrasing or order.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility, but follow a predetermined thematic framework, giving a sense of order. For this reason, they are often considered “the best of both worlds.”

However, if the questions differ substantially between participants, it can be challenging to look for patterns, lessening the generalizability and validity of your results.

- You have prior interview experience. It’s easier than you think to accidentally ask a leading question when coming up with questions on the fly. Overall, spontaneous questions are much more difficult than they may seem.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. The answers you receive can help guide your future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview. The questions and the order in which they are asked are not set. Instead, the interview can proceed more spontaneously, based on the participant’s previous answers.

Unstructured interviews are by definition open-ended. This flexibility can help you gather detailed information on your topic, while still allowing you to observe patterns between participants.

However, so much flexibility means that they can be very challenging to conduct properly. You must be very careful not to ask leading questions, as biased responses can lead to lower reliability or even invalidate your research.

- You have a solid background in your research topic and have conducted interviews before.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking descriptive data that will deepen and contextualize your initial hypotheses.

- Your research necessitates forming a deeper connection with your participants, encouraging them to feel comfortable revealing their true opinions and emotions.

A focus group brings together a group of participants to answer questions on a topic of interest in a moderated setting. Focus groups are qualitative in nature and often study the group’s dynamic and body language in addition to their answers. Responses can guide future research on consumer products and services, human behavior, or controversial topics.

Focus groups can provide more nuanced and unfiltered feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organize than experiments or large surveys . However, their small size leads to low external validity and the temptation as a researcher to “cherry-pick” responses that fit your hypotheses.

- Your research focuses on the dynamics of group discussion or real-time responses to your topic.

- Your questions are complex and rooted in feelings, opinions, and perceptions that cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no.”

- Your topic is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the type of interview you are conducting, your questions will differ in style, phrasing, and intention. Structured interview questions are set and precise, while the other types of interviews allow for more open-endedness and flexibility.

Here are some examples.

- Semi-structured

- Unstructured

- Focus group

- Do you like dogs? Yes/No

- Do you associate dogs with feeling: happy; somewhat happy; neutral; somewhat unhappy; unhappy

- If yes, name one attribute of dogs that you like.

- If no, name one attribute of dogs that you don’t like.

- What feelings do dogs bring out in you?

- When you think more deeply about this, what experiences would you say your feelings are rooted in?

Interviews are a great research tool. They allow you to gather rich information and draw more detailed conclusions than other research methods, taking into consideration nonverbal cues, off-the-cuff reactions, and emotional responses.

However, they can also be time-consuming and deceptively challenging to conduct properly. Smaller sample sizes can cause their validity and reliability to suffer, and there is an inherent risk of interviewer effect arising from accidentally leading questions.

Here are some advantages and disadvantages of each type of interview that can help you decide if you’d like to utilize this research method.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Social desirability bias is the tendency for interview participants to give responses that will be viewed favorably by the interviewer or other participants. It occurs in all types of interviews and surveys , but is most common in semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

Social desirability bias can be mitigated by ensuring participants feel at ease and comfortable sharing their views. Make sure to pay attention to your own body language and any physical or verbal cues, such as nodding or widening your eyes.

This type of bias can also occur in observations if the participants know they’re being observed. They might alter their behavior accordingly.

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest. It is one of 4 types of interviews .

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 30, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/interviews-research/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, unstructured interview | definition, guide & examples, structured interview | definition, guide & examples, semi-structured interview | definition, guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Fam Med Community Health

- v.7(2); 2019

Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour

Melissa dejonckheere.

1 Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Lisa M Vaughn

2 Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

3 Division of Emergency Medicine, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Associated Data

fmch-2018-000057supp001.pdf

Semistructured in-depth interviews are commonly used in qualitative research and are the most frequent qualitative data source in health services research. This method typically consists of a dialogue between researcher and participant, guided by a flexible interview protocol and supplemented by follow-up questions, probes and comments. The method allows the researcher to collect open-ended data, to explore participant thoughts, feelings and beliefs about a particular topic and to delve deeply into personal and sometimes sensitive issues. The purpose of this article was to identify and describe the essential skills to designing and conducting semistructured interviews in family medicine and primary care research settings. We reviewed the literature on semistructured interviewing to identify key skills and components for using this method in family medicine and primary care research settings. Overall, semistructured interviewing requires both a relational focus and practice in the skills of facilitation. Skills include: (1) determining the purpose and scope of the study; (2) identifying participants; (3) considering ethical issues; (4) planning logistical aspects; (5) developing the interview guide; (6) establishing trust and rapport; (7) conducting the interview; (8) memoing and reflection; (9) analysing the data; (10) demonstrating the trustworthiness of the research; and (11) presenting findings in a paper or report. Semistructured interviews provide an effective and feasible research method for family physicians to conduct in primary care research settings. Researchers using semistructured interviews for data collection should take on a relational focus and consider the skills of interviewing to ensure quality. Semistructured interviewing can be a powerful tool for family physicians, primary care providers and other health services researchers to use to understand the thoughts, beliefs and experiences of individuals. Despite the utility, semistructured interviews can be intimidating and challenging for researchers not familiar with qualitative approaches. In order to elucidate this method, we provide practical guidance for researchers, including novice researchers and those with few resources, to use semistructured interviewing as a data collection strategy. We provide recommendations for the essential steps to follow in order to best implement semistructured interviews in family medicine and primary care research settings.

Introduction

Semistructured interviews can be used by family medicine researchers in clinical settings or academic settings even with few resources. In contrast to large-scale epidemiological studies, or even surveys, a family medicine researcher can conduct a highly meaningful project with interviews with as few as 8–12 participants. For example, Chang and her colleagues, all family physicians, conducted semistructured interviews with 10 providers to understand their perspectives on weight gain in pregnant patients. 1 The interviewers asked questions about providers’ overall perceptions on weight gain, their clinical approach to weight gain during pregnancy and challenges when managing weight gain among pregnant patients. Additional examples conducted by or with family physicians or in primary care settings are summarised in table 1 . 1–6

Examples of research articles using semistructured interviews in primary care research

From our perspective as seasoned qualitative researchers, conducting effective semistructured interviews requires: (1) a relational focus, including active engagement and curiosity, and (2) practice in the skills of interviewing. First, a relational focus emphasises the unique relationship between interviewer and interviewee. To obtain quality data, interviews should not be conducted with a transactional question-answer approach but rather should be unfolding, iterative interactions between the interviewer and interviewee. Second, interview skills can be learnt. Some of us will naturally be more comfortable and skilful at conducting interviews but all aspects of interviews are learnable and through practice and feedback will improve. Throughout this article, we highlight strategies to balance relationship and rigour when conducting semistructured interviews in primary care and the healthcare setting.

Qualitative research interviews are ‘attempts to understand the world from the subjects’ point of view, to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations’ (p 1). 7 Qualitative research interviews unfold as an interviewer asks questions of the interviewee in order to gather subjective information about a particular topic or experience. Though the definitions and purposes of qualitative research interviews vary slightly in the literature, there is common emphasis on the experiences of interviewees and the ways in which the interviewee perceives the world (see table 2 for summary of definitions from seminal texts).

Definitions of qualitative interviews

The most common type of interview used in qualitative research and the healthcare context is semistructured interview. 8 Figure 1 highlights the key features of this data collection method, which is guided by a list of topics or questions with follow-up questions, probes and comments. Typically, the sequencing and wording of the questions are modified by the interviewer to best fit the interviewee and interview context. Semistructured interviews can be conducted in multiple ways (ie, face to face, telephone, text/email, individual, group, brief, in-depth), each of which have advantages and disadvantages. We will focus on the most common form of semistructured interviews within qualitative research—individual, face-to-face, in-depth interviews.

Key characteristics of semistructured interviews.

Purpose of semistructured interviews

The overall purpose of using semistructured interviews for data collection is to gather information from key informants who have personal experiences, attitudes, perceptions and beliefs related to the topic of interest. Researchers can use semistructured interviews to collect new, exploratory data related to a research topic, triangulate other data sources or validate findings through member checking (respondent feedback about research results). 9 If using a mixed methods approach, semistructured interviews can also be used in a qualitative phase to explore new concepts to generate hypotheses or explain results from a quantitative phase that tests hypotheses. Semistructured interviews are an effective method for data collection when the researcher wants: (1) to collect qualitative, open-ended data; (2) to explore participant thoughts, feelings and beliefs about a particular topic; and (3) to delve deeply into personal and sometimes sensitive issues.

Designing and conducting semistructured interviews

In the following section, we provide recommendations for the steps required to carefully design and conduct semistructured interviews with emphasis on applications in family medicine and primary care research (see table 3 ).

Steps to designing and conducting semistructured interviews

Steps for designing and conducting semistructured interviews

Step 1: determining the purpose and scope of the study.

The purpose of the study is the primary objective of your project and may be based on an anecdotal experience, a review of the literature or previous research finding. The purpose is developed in response to an identified gap or problem that needs to be addressed.

Research questions are the driving force of a study because they are associated with every other aspect of the design. They should be succinct and clearly indicate that you are using a qualitative approach. Qualitative research questions typically start with ‘What’, ‘How’ or ‘Why’ and focus on the exploration of a single concept based on participant perspectives. 10

Step 2: identifying participants

After deciding on the purpose of the study and research question(s), the next step is to determine who will provide the best information to answer the research question. Good interviewees are those who are available, willing to be interviewed and have lived experiences and knowledge about the topic of interest. 11 12 Working with gatekeepers or informants to get access to potential participants can be extremely helpful as they are trusted sources that control access to the target sample.

Sampling strategies are influenced by the research question and the purpose of the study. Unlike quantitative studies, statistical representativeness is not the goal of qualitative research. There is no calculation of statistical power and the goal is not a large sample size. Instead, qualitative approaches seek an in-depth and detailed understanding and typically use purposeful sampling. See the study of Hatch for a summary of various types of purposeful sampling that can be used for interview studies. 12

‘How many participants are needed?’ The most common answer is, ‘it depends’—it depends on the purpose of the study, what kind of study is planned and what questions the study is trying to answer. 12–14 One common standard in qualitative sample sizes is reaching thematic saturation, which refers to the point at which no new thematic information is gathered from participants. Malterud and colleagues discuss the concept of information power , or a qualitative equivalent to statistical power, to determine how many interviews should be collected in a study. They suggest that the size of a sample should depend on the aim, homogeneity of the sample, theory, interview quality and analytic strategy. 14

Step 3: considering ethical issues

An ethical attitude should be present from the very beginning of the research project even before you decide who to interview. 15 This ethical attitude should incorporate respect, sensitivity and tact towards participants throughout the research process. Because semistructured interviewing often requires the participant to reveal sensitive and personal information directly to the interviewer, it is important to consider the power imbalance between the researcher and the participant. In healthcare settings, the interviewer or researcher may be a part of the patient’s healthcare team or have contact with the healthcare team. The researchers should ensure the interviewee that their participation and answers will not influence the care they receive or their relationship with their providers. Other issues to consider include: reducing the risk of harm; protecting the interviewee’s information; adequately informing interviewees about the study purpose and format; and reducing the risk of exploitation. 10

Step 4: planning logistical aspects

Careful planning particularly around the technical aspects of interviews can be the difference between a great interview and a not so great interview. During the preparation phase, the researcher will need to plan and make decisions about the best ways to contact potential interviewees, obtain informed consent, arrange interview times and locations convenient for both participant and researcher, and test recording equipment. Although many experienced researchers have found themselves conducting interviews in less than ideal locations, the interview location should avoid (or at least minimise) interruptions and be appropriate for the interview (quiet, private and able to get a clear recording). 16 For some research projects, the participants’ homes may make sense as the best interview location. 16

Initial contacts can be made through telephone or email and followed up with more details so the individual can make an informed decision about whether they wish to be interviewed. Potential participants should know what to expect in terms of length of time, purpose of the study, why they have been selected and who will be there. In addition, participants should be informed that they can refuse to answer questions or can withdraw from the study at any time, including during the interview itself.

Audio recording the interview is recommended so that the interviewer can concentrate on the interview and build rapport rather than being distracted with extensive note taking 16 (see table 4 for audio-recording tips). Participants should be informed that audio recording is used for data collection and that they can refuse to be audio recorded should they prefer.

Suggestions for successful audio recording of interviews

Most researchers will want to have interviews transcribed verbatim from the audio recording. This allows you to refer to the exact words of participants during the analysis. Although it is possible to conduct analyses from the audio recordings themselves or from notes, it is not ideal. However, transcription can be extremely time consuming and, if not done yourself, can be costly.

In the planning phase of research, you will want to consider whether qualitative research software (eg, NVivo, ATLAS.ti, MAXQDA, Dedoose, and so on) will be used to assist with organising, managing and analysis. While these tools are helpful in the management of qualitative data, it is important to consider your research budget, the cost of the software and the learning curve associated with using a new system.

Step 5: developing the interview guide

Semistructured interviews include a short list of ‘guiding’ questions that are supplemented by follow-up and probing questions that are dependent on the interviewee’s responses. 8 17 All questions should be open ended, neutral, clear and avoid leading language. In addition, questions should use familiar language and avoid jargon.

Most interviews will start with an easy, context-setting question before moving to more difficult or in-depth questions. 17 Table 5 gives details of the types of guiding questions including ‘grand tour’ questions, 18 core questions and planned and unplanned follow-up questions.

Questions and prompts in semistructured interviewing

To illustrate, online supplementary appendix A presents a sample interview guide from our study of weight gain during pregnancy among young women. We start with the prompt, ‘Tell me about how your pregnancy has been so far’ to initiate conversation about their thoughts and feelings during pregnancy. The subsequent questions will elicit responses to help answer our research question about young women’s perspectives related to weight gain during pregnancy.

Supplementary data

After developing the guiding questions, it is important to pilot test the interview. Having a good sense of the guide helps you to pace the interview (and not run out of time), use a conversational tone and make necessary adjustments to the questions.

Like all qualitative research, interviewing is iterative in nature—data collection and analysis occur simultaneously, which may result in changes to the guiding questions as the study progresses. Questions that are not effective may be replaced with other questions and additional probes can be added to explore new topics that are introduced by participants in previous interviews. 10

Step 6: establishing trust and rapport

Interviews are a special form of relationship, where the interviewer and interviewee converse about important and often personal topics. The interviewer must build rapport quickly by listening attentively and respectfully to the information shared by the interviewee. 19 As the interview progresses, the interviewer must continue to demonstrate respect, encourage the interviewee to share their perspectives and acknowledge the sensitive nature of the conversation. 20

To establish rapport, it is important to be authentic and open to the interviewee’s point of view. It is possible that the participants you recruit for your study will have preconceived notions about research, which may include mistrust. As a result, it is important to describe why you are conducting the research and how their participation is meaningful. In an interview relationship, the interviewee is the expert and should be treated as such—you are relying on the interviewee to enhance your understanding and add to your research. Small behaviours that can enhance rapport include: dressing professionally but not overly formal; avoiding jargon or slang; and using a normal conversational tone. Because interviewees will be discussing their experience, having some awareness of contextual or cultural factors that may influence their perspectives may be helpful as background knowledge.

Step 7: conducting the interview

Location and set-up.

The interview should have already been scheduled at a convenient time and location for the interviewee. The location should be private, ideally with a closed door, rather than a public place. It is helpful if there is a room where you can speak privately without interruption, and where it is quiet enough to hear and audio record the interview. Within the interview space, Josselson 15 suggests an arrangement with a comfortable distance between the interviewer and interviewee with a low table in between for the recorder and any materials (consent forms, questionnaires, water, and so on).

Beginning the interview

Many interviewers start with chatting to break the ice and attempt to establish commonalities, rapport and trust. Most interviews will need to begin with a brief explanation of the research study, consent/assent procedures, rationale for talking to that particular interviewee and description of the interview format and agenda. 11 It can also be helpful if the interviewer shares a little about who they are and why they are interested in the topic. The recording equipment should have already been tested thoroughly but interviewers may want to double-check that the audio equipment is working and remind participants about the reason for recording.

Interviewer stance

During the interview, the interviewer should adopt a friendly and non-judgemental attitude. You will want to maintain a warm and conversational tone, rather than a rote, question-answer approach. It is important to recognise the potential power differential as a researcher. Conveying a sense of being in the interview together and that you as the interviewer are a person just like the interviewee can help ease any discomfort. 15

Active listening

During a face-to-face interview, there is an opportunity to observe social and non-verbal cues of the interviewee. These cues may come in the form of voice, body language, gestures and intonation, and can supplement the interviewee’s verbal response and can give clues to the interviewer about the process of the interview. 21 Listening is the key to successful interviewing. 22 Listening should be ‘attentive, empathic, nonjudgmental, listening in order to invite, and engender talk’ 15 15 (p 66). Silence, nods, smiles and utterances can also encourage further elaboration from the interviewee.

Continuing the interview

As the interview progresses, the interviewer can repeat the words used by the interviewee, use planned and unplanned follow-up questions that invite further clarification, exploration or elaboration. As DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree 10 explain: ‘Throughout the interview, the goal of the interviewer is to encourage the interviewee to share as much information as possible, unselfconsciously and in his or her own words’ (p 317). Some interviewees are more forthcoming and will offer many details of their experiences without much probing required. Others will require prompting and follow-up to elicit sufficient detail.

As a result, follow-up questions are equally important to the core questions in a semistructured interview. Prompts encourage people to continue talking and they can elicit more details needed to understand the topic. Examples of verbal probes are repeating the participant’s words, summarising the main idea or expressing interest with verbal agreement. 8 11 See table 6 for probing techniques and example probes we have used in our own interviewing.

Probing techniques for semistructured interviews (modified from Bernard 30 )

Step 8: memoing and reflection

After an interview, it is essential for the interviewer to begin to reflect on both the process and the content of the interview. During the actual interview, it can be difficult to take notes or begin reflecting. Even if you think you will remember a particular moment, you likely will not be able to recall each moment with sufficient detail. Therefore, interviewers should always record memos —notes about what you are learning from the data. 23 24 There are different approaches to recording memos: you can reflect on several specific ideas, or create a running list of thoughts. Memos are also useful for improving the quality of subsequent interviews.

Step 9: analysing the data

The data analysis strategy should also be developed during planning stages because analysis occurs concurrently with data collection. 25 The researcher will take notes, modify the data collection procedures and write reflective memos throughout the data collection process. This begins the process of data analysis.

The data analysis strategy used in your study will depend on your research question and qualitative design—see the study of Creswell for an overview of major qualitative approaches. 26 The general process for analysing and interpreting most interviews involves reviewing the data (in the form of transcripts, audio recordings or detailed notes), applying descriptive codes to the data and condensing and categorising codes to look for patterns. 24 27 These patterns can exist within a single interview or across multiple interviews depending on the research question and design. Qualitative computer software programs can be used to help organise and manage interview data.

Step 10: demonstrating the trustworthiness of the research

Similar to validity and reliability, qualitative research can be assessed on trustworthiness. 9 28 There are several criteria used to establish trustworthiness: credibility (whether the findings accurately and fairly represent the data), transferability (whether the findings can be applied to other settings and contexts), confirmability (whether the findings are biased by the researcher) and dependability (whether the findings are consistent and sustainable over time).

Step 11: presenting findings in a paper or report

When presenting the results of interview analysis, researchers will often report themes or narratives that describe the broad range of experiences evidenced in the data. This involves providing an in-depth description of participant perspectives and being sure to include multiple perspectives. 12 In interview research, the participant words are your data. Presenting findings in a report requires the integration of quotes into a more traditional written format.

Conclusions

Though semistructured interviews are often an effective way to collect open-ended data, there are some disadvantages as well. One common problem with interviewing is that not all interviewees make great participants. 12 29 Some individuals are hard to engage in conversation or may be reluctant to share about sensitive or personal topics. Difficulty interviewing some participants can affect experienced and novice interviewers. Some common problems include not doing a good job of probing or asking for follow-up questions, failure to actively listen, not having a well-developed interview guide with open-ended questions and asking questions in an insensitive way. Outside of pitfalls during the actual interview, other problems with semistructured interviewing may be underestimating the resources required to recruit participants, interview, transcribe and analyse the data.

Despite their limitations, semistructured interviews can be a productive way to collect open-ended data from participants. In our research, we have interviewed children and adolescents about their stress experiences and coping behaviours, young women about their thoughts and behaviours during pregnancy, practitioners about the care they provide to patients and countless other key informants about health-related topics. Because the intent is to understand participant experiences, the possible research topics are endless.

Due to the close relationships family physicians have with their patients, the unique settings in which they work, and in their advocacy, semistructured interviews are an attractive approach for family medicine researchers, even if working in a setting with limited research resources. When seeking to balance both the relational focus of interviewing and the necessary rigour of research, we recommend: prioritising listening over talking; using clear language and avoiding jargon; and deeply engaging in the interview process by actively listening, expressing empathy, demonstrating openness to the participant’s worldview and thanking the participant for helping you to understand their experience.

Further Reading

- Edwards R, & Holland J. (2013). What is qualitative interviewing?: A&C Black.

- Josselson R. Interviewing for qualitative inquiry: A relational approach. Guilford Press, 2013.

- Kvale S. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. SAGE, London, 1996.

- Pope C, & Mays N. (Eds). (2006). Qualitative research in health care.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected. Reference details have been updated.

Contributors: Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Primary Research: What It Is, Purpose & Methods + Examples

As we continue exploring the exciting research world, we’ll come across two primary and secondary data approaches. This article will focus on primary research – what it is, how it’s done, and why it’s essential.

We’ll discuss the methods used to gather first-hand data and examples of how it’s applied in various fields. Get ready to discover how this research can be used to solve research problems , answer questions, and drive innovation.

What is Primary Research: Definition

Primary research is a methodology researchers use to collect data directly rather than depending on data collected from previously done research. Technically, they “own” the data. Primary research is solely carried out to address a certain problem, which requires in-depth analysis .

There are two forms of research:

- Primary Research

- Secondary Research

Businesses or organizations can conduct primary research or employ a third party to conduct research. One major advantage of primary research is this type of research is “pinpointed.” Research only focuses on a specific issue or problem and on obtaining related solutions.

For example, a brand is about to launch a new mobile phone model and wants to research the looks and features they will soon introduce.

Organizations can select a qualified sample of respondents closely resembling the population and conduct primary research with them to know their opinions. Based on this research, the brand can now think of probable solutions to make necessary changes in the looks and features of the mobile phone.

Primary Research Methods with Examples

In this technology-driven world, meaningful data is more valuable than gold. Organizations or businesses need highly validated data to make informed decisions. This is the very reason why many companies are proactive in gathering their own data so that the authenticity of data is maintained and they get first-hand data without any alterations.

Here are some of the primary research methods organizations or businesses use to collect data:

1. Interviews (telephonic or face-to-face)

Conducting interviews is a qualitative research method to collect data and has been a popular method for ages. These interviews can be conducted in person (face-to-face) or over the telephone. Interviews are an open-ended method that involves dialogues or interaction between the interviewer (researcher) and the interviewee (respondent).

Conducting a face-to-face interview method is said to generate a better response from respondents as it is a more personal approach. However, the success of face-to-face interviews depends heavily on the researcher’s ability to ask questions and his/her experience related to conducting such interviews in the past. The types of questions that are used in this type of research are mostly open-ended questions . These questions help to gain in-depth insights into the opinions and perceptions of respondents.

Personal interviews usually last up to 30 minutes or even longer, depending on the subject of research. If a researcher is running short of time conducting telephonic interviews can also be helpful to collect data.

2. Online surveys

Once conducted with pen and paper, surveys have come a long way since then. Today, most researchers use online surveys to send to respondents to gather information from them. Online surveys are convenient and can be sent by email or can be filled out online. These can be accessed on handheld devices like smartphones, tablets, iPads, and similar devices.

Once a survey is deployed, a certain amount of stipulated time is given to respondents to answer survey questions and send them back to the researcher. In order to get maximum information from respondents, surveys should have a good mix of open-ended questions and close-ended questions . The survey should not be lengthy. Respondents lose interest and tend to leave it half-done.

It is a good practice to reward respondents for successfully filling out surveys for their time and efforts and valuable information. Most organizations or businesses usually give away gift cards from reputed brands that respondents can redeem later.

3. Focus groups

This popular research technique is used to collect data from a small group of people, usually restricted to 6-10. Focus group brings together people who are experts in the subject matter for which research is being conducted.

Focus group has a moderator who stimulates discussions among the members to get greater insights. Organizations and businesses can make use of this method, especially to identify niche markets to learn about a specific group of consumers.

4. Observations

In this primary research method, there is no direct interaction between the researcher and the person/consumer being observed. The researcher observes the reactions of a subject and makes notes.

Trained observers or cameras are used to record reactions. Observations are noted in a predetermined situation. For example, a bakery brand wants to know how people react to its new biscuits, observes notes on consumers’ first reactions, and evaluates collective data to draw inferences .

Primary Research vs Secondary Research – The Differences

Primary and secondary research are two distinct approaches to gathering information, each with its own characteristics and advantages.

While primary research involves conducting surveys to gather firsthand data from potential customers, secondary market research is utilized to analyze existing industry reports and competitor data, providing valuable context and benchmarks for the survey findings.

Find out more details about the differences:

1. Definition

- Primary Research: Involves the direct collection of original data specifically for the research project at hand. Examples include surveys, interviews, observations, and experiments.

- Secondary Research: Involves analyzing and interpreting existing data, literature, or information. This can include sources like books, articles, databases, and reports.

2. Data Source

- Primary Research: Data is collected directly from individuals, experiments, or observations.

- Secondary Research: Data is gathered from already existing sources.

3. Time and Cost

- Primary Research: Often time-consuming and can be costly due to the need for designing and implementing research instruments and collecting new data.

- Secondary Research: Generally more time and cost-effective, as it relies on readily available data.

4. Customization

- Primary Research: Provides tailored and specific information, allowing researchers to address unique research questions.

- Secondary Research: Offers information that is pre-existing and may not be as customized to the specific needs of the researcher.

- Primary Research: Researchers have control over the research process, including study design, data collection methods, and participant selection.

- Secondary Research: Limited control, as researchers rely on data collected by others.

6. Originality

- Primary Research: Generates original data that hasn’t been analyzed before.

- Secondary Research: Involves the analysis of data that has been previously collected and analyzed.

7. Relevance and Timeliness

- Primary Research: Often provides more up-to-date and relevant data or information.

- Secondary Research: This may involve data that is outdated, but it can still be valuable for historical context or broad trends.

Advantages of Primary Research

Primary research has several advantages over other research methods, making it an indispensable tool for anyone seeking to understand their target market, improve their products or services, and stay ahead of the competition. So let’s dive in and explore the many benefits of primary research.

- One of the most important advantages is data collected is first-hand and accurate. In other words, there is no dilution of data. Also, this research method can be customized to suit organizations’ or businesses’ personal requirements and needs .

- I t focuses mainly on the problem at hand, which means entire attention is directed to finding probable solutions to a pinpointed subject matter. Primary research allows researchers to go in-depth about a matter and study all foreseeable options.

- Data collected can be controlled. I T gives a means to control how data is collected and used. It’s up to the discretion of businesses or organizations who are collecting data how to best make use of data to get meaningful research insights.

- I t is a time-tested method, therefore, one can rely on the results that are obtained from conducting this type of research.

Disadvantages of Primary Research

While primary research is a powerful tool for gathering unique and firsthand data, it also has its limitations. As we explore the drawbacks, we’ll gain a deeper understanding of when primary research may not be the best option and how to work around its challenges.

- One of the major disadvantages of primary research is it can be quite expensive to conduct. One may be required to spend a huge sum of money depending on the setup or primary research method used. Not all businesses or organizations may be able to spend a considerable amount of money.

- This type of research can be time-consuming. Conducting interviews and sending and receiving online surveys can be quite an exhaustive process and require investing time and patience for the process to work. Moreover, evaluating results and applying the findings to improve a product or service will need additional time.

- Sometimes, just using one primary research method may not be enough. In such cases, the use of more than one method is required, and this might increase both the time required to conduct research and the cost associated with it.

Every research is conducted with a purpose. Primary research is conducted by organizations or businesses to stay informed of the ever-changing market conditions and consumer perception. Excellent customer satisfaction (CSAT) has become a key goal and objective of many organizations.

A customer-centric organization knows the importance of providing exceptional products and services to its customers to increase customer loyalty and decrease customer churn. Organizations collect data and analyze it by conducting primary research to draw highly evaluated results and conclusions. Using this information, organizations are able to make informed decisions based on real data-oriented insights.

QuestionPro is a comprehensive survey platform that can be used to conduct primary research. Users can create custom surveys and distribute them to their target audience , whether it be through email, social media, or a website.

QuestionPro also offers advanced features such as skip logic, branching, and data analysis tools, making collecting and analyzing data easier. With QuestionPro, you can gather valuable insights and make informed decisions based on the results of your primary research. Start today for free!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

In-App Feedback Tools: How to Collect, Uses & 14 Best Tools

Mar 29, 2024

11 Best Customer Journey Analytics Software in 2024

17 Best VOC Software for Customer Experience in 2024

Mar 28, 2024

CEM Software: What it is, 7 Best CEM Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews

Dana Lynn Driscoll

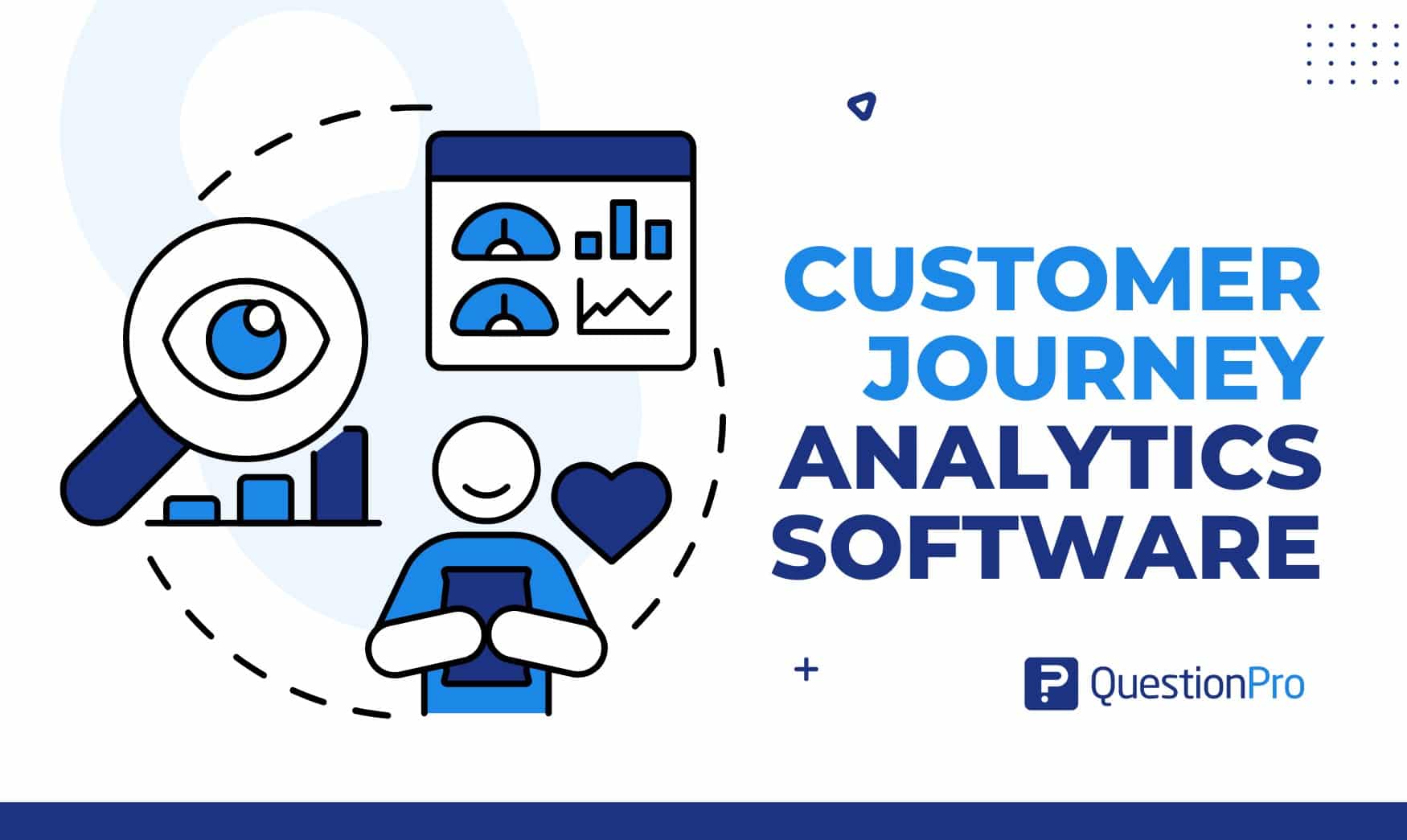

Primary Research: Definitions and Overview

How research is defined varies widely from field to field, and as you progress through your college career, your coursework will teach you much more about what it means to be a researcher within your field. [1] For example, engineers, who focus on applying scientific knowledge to develop designs, processes, and objects, conduct research using simulations, mathematical models, and a variety of tests to see how well their designs work. Sociologists conduct research using surveys, interviews, observations, and statistical analysis to better understand people, societies, and cultures. Graphic designers conduct research through locating images for reference for their artwork and engaging in background research on clients and companies to best serve their needs. Historians conduct research by examining archival materials— newspapers, journals, letters, and other surviving texts—and through conducting oral history interviews. Research is not limited to what has already been written or found at the library, also known as secondary research. Rather, individuals conducting research are producing the articles and reports found in a library database or in a book. Primary research, the focus of this essay, is research that is collected firsthand rather than found in a book, database, or journal.

Primary research is often based on principles of the scientific method, a theory of investigation first developed by John Stuart Mill in the nineteenth century in his book Philosophy of the Scientific Method . Although the application of the scientific method varies from field to field, the general principles of the scientific method allow researchers to learn more about the world and observable phenomena. Using the scientific method, researchers develop research questions or hypotheses and collect data on events, objects, or people that is measurable, observable, and replicable. The ultimate goal in conducting primary research is to learn about something new that can be confirmed by others and to eliminate our own biases in the process.

Essay Overview and Student Examples

The essay begins by providing an overview of ethical considerations when conducting primary research, and then covers the stages that you will go through in your primary research: planning, collecting, analyzing, and writing. After the four stages comes an introduction to three common ways of conducting primary research in first year writing classes:

- Observations . Observing and measuring the world around you, including observations of people and other measurable events.

- Interviews . Asking participants questions in a one-on-one or small group setting.

- Surveys . Asking participants about their opinions and behaviors through a short questionnaire.

In addition, we will be examining two student projects that used substantial portions of primary research:

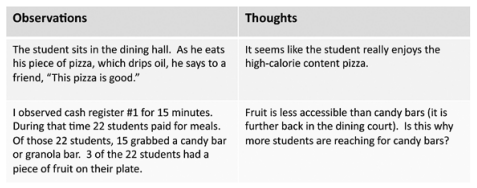

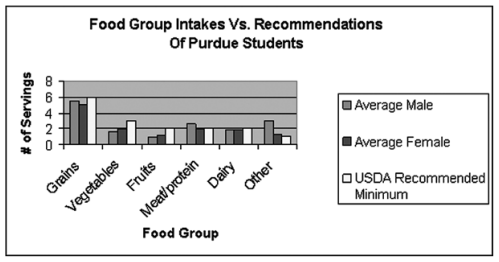

Derek Laan, a nutrition major at Purdue University, wanted to learn more about student eating habits on campus. His primary research included observations of the campus food courts, student behavior while in the food courts, and a survey of students’ daily food intake. His secondary research included looking at national student eating trends on college campuses, information from the United States Food and Drug Administration, and books on healthy eating.

Jared Schwab, an agricultural and biological engineering major at Purdue, was interested in learning more about how writing and communication took place in his field. His primary research included interviewing a professional engineer and a student who was a senior majoring in engineering. His secondary research included examining journals, books, professional organizations, and writing guides within the field of engineering.

Ethics of Primary Research

Both projects listed above included primary research on human participants; therefore, Derek and Jared both had to consider research ethics throughout their primary research process. As Earl Babbie writes in The Practice of Social Research , throughout the early and middle parts of the twentieth century researchers took advantage of participants and treated them unethically. During World War II, Nazi doctors performed heinous experiments on prisoners without their consent, while in the U.S., a number of medical and psychological experiments on caused patients undue mental and physical trauma and, in some cases, death. Because of these and other similar events, many nations have established ethical laws and guidelines for researchers who work with human participants. In the United States, the guidelines for the ethical treatment of human research participants are described in The Belmont Report , released in 1979. Today, universities have Institutional Review Boards (or IRBs) that oversee research. Students conducting research as part of a class may not need permission from the university’s IRB, although they still need to ensure that they follow ethical guidelines in research. The following provides a brief overview of ethical considerations: