Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.4: Persuasive Messages

Learning objectives.

i. Outline the structure of a persuasive message ii. Explain the importance of persuasion in professional contexts

Persuasion involves moving or motivating your audience by presenting arguments that convince them to adopt your view or do as you want. You’ve been doing this ever since you learned to speak. From convincing your parents to give you a treat to persuading them to lend you the car keys, you’ve developed more sophisticated means of persuasion over the years simply because of the rewards that come with their success. Now that you’ve entered (or will soon enter) the professional world, honing persuasive strategies for the workplace is vital to your livelihood when the reward is a sale, a promotion, or merely a regular paycheque.

Persuasion begins with motivation. If persuasion is a process and your audience’s action (e.g., buying a product or service) is the goal, then motivating them to accept an argument or a series of positions leading to the decision that you want them to adopt helps achieve that goal. If your goal is to convince a pet owner to spay or neuter their pet, for instance, you would use a few convincing arguments compelling them to accept that spaying or neutering is the right thing to do.

Persuasive Messages Topics

8.4.1: The Rhetorical Triangle

8.4.2: principles of persuasion, 8.4.3: indirect aida pattern of persuasion.

Use the rhetorical triangle by combining logic, emotional appeal, and authority (a.k.a. logos , pathos , and ethos in classical Aristotelian rhetoric) to cater your message to your audience. You could appeal to their sense of reason by explaining the logical consequences of not spaying or neutering their pet: increasing the local cat or dog population, or even producing a litter that you yourself have to deal with, including all the care and expenses related to it. You might appeal to their emotions by saying that the litters resulting from your pet’s mating with strays will suffer starvation and disease in their short lives. You could establish your credibility by explaining that you’ve earned a diploma in the Vet Tech program at Algonquin College and have eight years’ experience seeing the positive results that spaying or neutering has on local dog or cat populations, making you a trustworthy authority on the topic. All of these moves help overcome your audience’s resistance and convince them to follow your advice ( Business Communication for Success , 2015, 14.1). These three appeals can also complement other effective techniques in persuading an audience as we shall see throughout this section.

What’s the best way to succeed in persuading people to buy what you’re selling? Though there may sometimes be a single magic bullet, a combination of strategies has been found to be most effective. Social psychologist Robert Cialdini offers us six principles of persuasion that are powerful and effective no matter what the cultural context. Use them to help persuade people, but also recognize their use by others when determining how you’re being led towards a purchase, perhaps even one you should rightly resist.

- 8.4.2.1: Reciprocity

- 8.4.2.2: Scarcity

- 8.4.2.3: Authority

- 8.4.2.4: Commitment and consistency

- 8.4.2.5: Consensus

- 8.4.2.6: Liking

8.4.2.1: Principle of Reciprocity

I scratch your back; you scratch mine . Reciprocity means that when you give something to somebody, they feel obligated to give something back to you in return, even if only by saying “thank you.” If you are in customer service and go out of your way to meet the customer’s need, you are appealing to the principle of reciprocity with the knowledge that all but the most selfish among us perceive the need to reciprocate—in this case, by increasing the likelihood of making a purchase from you because you were especially helpful. Reciprocity builds trust and a relationship develops, reinforcing everything from personal to brand loyalty. By taking the lead and giving, you build in a moment a sense of obligation motivating the receiver to follow social norms and customs by giving back.

8.4.2.2: Principle of Scarcity

It’s universal to want what you can’t have. People are naturally attracted to the rare and exclusive. If they are convinced that they need to act now or it will disappear, they are motivated to act. Scarcity is the perception of dwindling supply of a limited and valuable product. For a sales representative, scarcity may be a key selling point—the particular car, theater tickets, or pair of shoes you are considering may be sold to someone else if you delay making a decision. By reminding customers not only of what they stand to gain but also of what they stand to lose, the sales rep increases their chances of swaying the customer from contemplation to action, which is to close the sale.

8.4.2.3: Principle of Authority

Notice how saying “According to researchers, . . .” makes whatever you say after these three words sound more true than if you began with “I think that . . . .” This is because you’re drawing on authority to build trust (recall the concept of ethos from the “rhetorical triangle” in §8.4.1 above), which is central to any purchase decision. Who does a customer turn to? A salesperson may be part of the process, but an endorsement by an authority holds credibility that no one with a vested interest can ever attain. Knowledge of a product, field, trends in the field, and even research can make a salesperson more effective by the appeal to the principle of authority. It may seem like extra work to educate your customers, but you need to reveal your expertise to gain credibility. We can borrow a measure of credibility by relating what experts have indicated about a product, service, market, or trend, and our awareness of competing viewpoints allows us insight that is valuable to the customer. Reading the manual of a product is not sufficient to gain expertise—you have to do extra homework. The principle of authority involves referencing experts and expertise.

8.4.2.4: Principle of Commitment and Consistency

When you commit to something, you feel obligated to follow through on it. For instance, if you announce on social media that you’re going to do yoga every day for a month, you feel greater pressure to actually do so than if you resolved to do it without telling anyone. This is because written words hold a special power over us when it feels as though their mere existence makes what we’re doing “official.” If we were on the fence, seeing it now in writing motivates us to act on it and thereby honour our word by going through with the purchase. In sales, this could involve getting a customer to sign up for a store credit card or a rewards program.

8.4.2.5: Principle of Consensus

If you make purchase decisions based on what you see in online reviews, you’re proving how effective the principle of consensus can be. People trust first-person testimonials when making purchase decisions, especially if there are many of them and they’re unanimous in their endorsement. The herd mentality is a powerful force across humanity. If “everybody else” thinks this product is great, then it must be great. Such argumentum ad populum (Latin for “argument to the people”) is a logical fallacy because there’s no guarantee that something is true if the majority believe it. We are genetically programmed to trust our tribe in the absence more credible information, however, because it makes decision-making easier in the fight for survival.

8.4.2.6: Principle of Liking

We are more likely to buy something from someone we like, who likes us, who is attractive, and who we can identify with because we see enough points of similarity between ourselves. These perceptions offer a sense of safe belonging. If a salesperson says they’re going to cut you a deal because they like you, your response is to reciprocate that acceptance by going through with the deal. If you find them easy to look at—no matter which sex—you are predisposed to like them because, from an evolutionary standpoint, attractiveness suggests genetic superiority and hence authority. Furthermore, if the salesperson makes themselves relatable by saying that they had the same problem as you and this is what they did about it, you’re more likely to follow their advice because that bond produces the following argument in your mind: “This person and I are similar in that we share a common problem, they solved it expertly by doing X, and I can therefore solve the same problem in my life by doing X” ( Business Communication for Success , 2015, 14.2) .

Return to the Persuasive Messages Topics Menu

When you consider the tens or hundreds of thousands of TV commercials you’ve seen in your life, you understand how they all take the indirect approach (typically associated with delivering bad news, as we saw in §4.1.2 and §8.3 above) because they assume you will resist parting with your money. Instead of taking a direct approach by simply saying in seven seconds “Come to our store, give us $100, and we’ll give you these awesome sunglasses,” commercials use a variety of techniques to motivate you to ease your grip on your money. They will dramatize a problem-solution scenario, use celebrity endorsements, humour, special effects, jingles, intrigue, and so on. You’re well familiar with the pattern from having seen and absorbed it many times each day of your life, but when you must make a persuasive pitch yourself as part of your professional duties, you may need a little guidance with the typical four-part indirect pattern known as “AIDA”:

8.4.3.1: A – Attention-getting Opening

8.4.3.2: i – interest-building body, 8.4.3.3: d – desire-building details and overcoming resistance, 8.4.3.4: a – action-motivating closing.

When your product, service, or initiative is unknown to the reader, come out swinging to get their attention with a surprise opening. Your goal is to make it inviting enough for the reader to want to stay and read the whole message. The opening can only do that if it uses an original approach that connects the reader to the product, service, or initiative with its central selling feature. This feature is what distinguishes it from others of its kind; it could be a new model of (or feature on) a familiar product, a reduced price, a new technology altogether, etc. A tired, old opening sales pitch that appears to be aimed at a totally different demographic with a product that doesn’t seem to be any different from others of its kind, however, will lose the reader at the opening pitch. One that uses one of the following techniques, however, stands a good chance of hooking the reader in to stick around and see if the pitch offers an attractive solution to one of their problems:

- Imagine cooling down from your half-hour sunbath on the white-sand beach with a dip in turquoise Caribbean waters. This will be you if you book a Caribbean Sun resort vacation package today!

- What if I told you that you could increase your sales by 25% in the next quarter by using an integrated approach to social media?

- Consider a typical day in the life of a FitBit user: . . .

- Is your hard-earned money just sitting in a chequing account losing value from inflation year after year?

- Have you ever thought about investing your money but have no idea where to start?

- Yogi Berra once said, “If you come to a fork in the road, take it!” At Epic Adventures, any one of our Rocky Mountain hiking experiences will elevate you to the highest of your personal highs.

- The shark is the ocean’s top predator. When you’re looking to invest your hard-earned money, why would you want to swim with sharks? Go to a trusted broker at Lighthouse Financial.

- Look around the room. One in five of you will die of heart disease. Every five minutes, a Canadian aged 20 or over dies from heart disease, the second leading cause of death in the country. At the Fitness Stop, keep your heart strong with your choice of 20 different cardio machines and a variety of aerobics programs designed to work with your busy schedule.

The goal here is to get the reader thinking, “Oooh, I want that ” or “I need that” without giving them an opportunity to doubt whether they really do. Of course, the attention-gaining opening is unnecessary if the reader already knows something about the product or service. If the customer comes to you asking for further details, you would just skip to the I-, D-, or A-part of the pitch that answers their questions.

Once you’ve got the reader’s attention in the opening, your job is now to build on that by extending the interest-building pitch further. If your opening was too busy painting a solution-oriented picture of the product to mention the company name or stress a central selling feature, now is the time to reveal both in a cohesive way. If the opening goes “What weighs nothing but is the most valuable commodity in your lives? —Time,” a cohesive bridge to the interest-building bod of the message could be “At Synaptic Communications, we will save you time by . . . .” Though you might want to save detailed product description for the next part, some description might be necessary here as you focus on how the product or service will solve the customer’s problem.

Key to making this part effective is describing how the customer will use or benefit from the product or service, placing them in the centre of the action with the “you” view (see §4.5.2.5.1 above):

When you log into your WebCrew account for the first time, an interactive AI guide will greet and guide you through the design options for your website step by step. You will be amazed by how easy it is to build your website from the ground up merely by answering simple multiple-choice questions about what you want and selecting from design options tailored to meet your individual needs. Your AI guide will automatically shortlist stock photo options and prepare text you can plug into your site without having to worry about permissions.

Here, the words you or your appear 11 times in 3 sentences while still sounding natural rather than like a high-pressure sales tactic.

Now that you’ve hooked the reader in and hyped-up your product, service, or idea with a central selling feature, you can flesh out the product description with additional evidence supporting your previous claims. Science and the rational appeal of hard facts work well here, but the evidence must be appropriate. A pitch for a sensible car, for instance, will focus on fuel efficiency with litres per 100km or range in number of kilometres per battery charge in the case of an electric vehicle, not top speed or the time it takes to get from 0 to 100 km/h. Space permitting, you might want to focus on only two or three additional selling features since this is still a pitch rather than a product specifications (“specs”) sheet, though you can also use this space to point the reader to such details in an accompanying document or webpage.

Testimonials and guarantees are effective desire-building contributions as long as they’re believable. If someone else much like you endorses a product in an online review, you’ll be more likely to feel that you too will benefit from it (see §8.4.1.5 above on the principle of consensus). A guarantee will also make the reader feel as though they have nothing to lose if they can just return the product or cancel a service and get their money back if they don’t like it after all. Costco has been remarkably successful as a wholesaler appealing to individual grocery shoppers partly on the strength of a really generous return policy.

Rhetorically, this point in the pitch also provides an opportunity to raise and defeat objections you anticipate the reader having towards your product, service, or idea. This follows a technique called refutation , which comes just before the conclusion (“peroration”) in the six-part classical argument structure. It works to dispel any lingering doubt in the reader’s mind about the product as pitched to that point.

If the product is a herbicide being recommended as part of a lawncare strategy, for instance, the customer may have reservations about spreading harmful chemicals around their yard. A refutation that assures them that the product isn’t harmful to humans will help here, especially if it’s from a trusted source such as Canada Health or Consumer Reports . Other effective tricks in the vein of emotional appeal (complementing the evidence-based rational appeal that preceded it) include picturing a worst-case scenario resulting from not using the product. Against concerns about using a herbicide, a pitch could use scare-tactics such as talking about the spread of wild parsnip that can cause severe burns upon contact with skin and blindness if the sap gets in your eyes. By steering the customer to picturing their hapless kids running naïvely through the weeds in their backyard, crying in pain, rubbing their eyes, and going blind, you can undermine any lingering reservations a parent may have about using the herbicide.

The main point of your message directs the reader to act (e.g., buy your product or service), so its appearance at the end of the message—rather than at the beginning—is what makes an AIDA pitch indirect. If the AID-part of your pitch has the reader feeling that they have no choice but to buy the product or service, then this is the right time to tell them how and where to get it, as well as the price.

Pricing itself requires some strategy. The following are well-known techniques for increasing sales:

- Charm pricing : dropping a round number by a cent to make it end in a 99 because the casually browsing consumer brain’s left-digit bias will register a price of $29.99 as closer to $20 than $30, especially if the 99 is physically smaller in superscript ($2999).

- Prestige pricing : keeping a round number round and dropping the dollar sign for a luxury item. For instance, placing the number 70 beside a dinner option on a fancy restaurant’s menu makes it look like a higher-quality dish than if it were priced at $6999. To impress a date with your spending power, you’ll go for the 70 option over something with charm pricing.

- Anchoring : making a price look more attractive by leading with a higher reference price. For instance, if you want to sell a well-priced item, you would strategically place a more expensive model next to it so that the consumer has a sense of the price range they’re dealing with when they don’t otherwise know. They’ll feel like they’re getting more of a bargain with the well-priced model. Similarly, showing the regular price crossed out near the marked-down price on the price tag is really successful in increasing sales (Boachie, 2016) .

If the product or service is subscription-based or relatively expensive, breaking it down to a monthly, weekly, or even daily price installment works to make it seem more manageable than giving the entire sum. Equating it to another small daily purchase also works. The cost of sponsoring a child in a drought-stricken nation sounds better when it’s equated with the cost of a cup of coffee per day. A car that’s a hundred dollars per week in lease payments sounds more doable than the entire cost, especially if you don’t have $45,000 to drop right now but are convinced that you must have that car anyway. Framing the price in terms of how much the customer will save is also effective, as is brushing over it in a subordinate clause to repeat the central selling point:

For only §49.99 per month, you can go about your business all day and sleep easy at night knowing your home is safe with Consumer Reports’ top-rated home security system.

Action directions must be easy to follow to clinch customer buy-in. Customers are in familiar territory if they merely have to go to a retail location, pick the unit up off the shelf, and run it through the checkout. Online ordering and delivery is even easier. Vague directions (“See you soon!”) or a convoluted, multi-step registration and ordering process, however, will frustrate and scare the customer away. Rewards for quick action are effective (see §8.4.3.2 above on the principle of scarcity), such as saying that the deal holds only while supplies last or the promo code will expire at the end of the day.

Sales pitches are effective only if they’re credible (see §8.4.2.3 above on the principle of authority). Even one exaggerated claim can sink the entire message with the sense that it’s all just snake-oil smoke and mirrors. Saying that your product is the best in the world, but not backing this up with any third-party endorsement or sales figures proving the claim, will undermine every other credible point you make by making your reader doubt it all (Lehman, DuFrene, & Murphy, 2013, pp. 134-143). We’ll return to topic of avoidable unethical persuasive techniques in §10.2.4 below, but first let’s turn our attention in the next section to a more uplifting type of message.

Key Takeaway

2. Let’s say you have a database of customers who have consented to receiving notices of promotional deals and special offers from the company you work for in the profession of your choosing or an industry adjacent to it (e.g., if you’re training to be a police officer, put yourself in the position of marketing for a company selling tasers to police departments). Write a one-page letter that will be mailed out to each convincing them to purchase a new product or service your company is offering. Follow the indirect AIDA pattern described in §8.4.3 and involve some of the persuasive strategies summarized in §8.4.2 above.

Boachie, P. (2016, July 21). 5 strategies of ‘psychological pricing.’ Entrepreneur . Retrieved from https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/279464

Lehman, C. M., DuFrene, D, & Murphy, R. (2013). BCOM (1st Can. Ed.). Toronto: Nelson Education.

Communication at Work Copyright © 2019 by Jordan Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Persuasive Speaking

Learning objectives.

- Explain how claims, evidence, and warrants function to create an argument.

- Identify strategies for choosing a persuasive speech topic.

- Identify strategies for adapting a persuasive speech based on an audience’s orientation to the proposition.

- Distinguish among propositions of fact, value, and policy.

- Choose an organizational pattern that is fitting for a persuasive speech topic.

We produce and receive persuasive messages daily, but we don’t often stop to think about how we make the arguments we do or the quality of the arguments that we receive. In this section, we’ll learn the components of an argument, how to choose a good persuasive speech topic, and how to adapt and organize a persuasive message.

Foundation of Persuasion

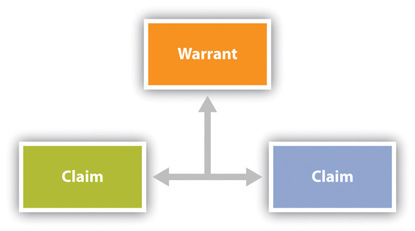

Persuasive speaking seeks to influence the beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors of audience members. In order to persuade, a speaker has to construct arguments that appeal to audience members. Arguments form around three components: claim, evidence, and warrant. The claim is the statement that will be supported by evidence. Your thesis statement is the overarching claim for your speech, but you will make other claims within the speech to support the larger thesis. Evidence , also called grounds, supports the claim. The main points of your persuasive speech and the supporting material you include serve as evidence. For example, a speaker may make the following claim: “There should be a national law against texting while driving.” The speaker could then support the claim by providing the following evidence: “Research from the US Department of Transportation has found that texting while driving creates a crash risk that is twenty-three times worse than driving while not distracted.” The warrant is the underlying justification that connects the claim and the evidence. One warrant for the claim and evidence cited in this example is that the US Department of Transportation is an institution that funds research conducted by credible experts. An additional and more implicit warrant is that people shouldn’t do things they know are unsafe.

Figure 11.2 Components of an Argument

The quality of your evidence often impacts the strength of your warrant, and some warrants are stronger than others. A speaker could also provide evidence to support their claim advocating for a national ban on texting and driving by saying, “I have personally seen people almost wreck while trying to text.” While this type of evidence can also be persuasive, it provides a different type and strength of warrant since it is based on personal experience. In general, the anecdotal evidence from personal experience would be given a weaker warrant than the evidence from the national research report. The same process works in our legal system when a judge evaluates the connection between a claim and evidence. If someone steals my car, I could say to the police, “I’m pretty sure Mario did it because when I said hi to him on campus the other day, he didn’t say hi back, which proves he’s mad at me.” A judge faced with that evidence is unlikely to issue a warrant for Mario’s arrest. Fingerprint evidence from the steering wheel that has been matched with a suspect is much more likely to warrant arrest.

As you put together a persuasive argument, you act as the judge. You can evaluate arguments that you come across in your research by analyzing the connection (the warrant) between the claim and the evidence. If the warrant is strong, you may want to highlight that argument in your speech. You may also be able to point out a weak warrant in an argument that goes against your position, which you could then include in your speech. Every argument starts by putting together a claim and evidence, but arguments grow to include many interrelated units.

Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

As with any speech, topic selection is important and is influenced by many factors. Good persuasive speech topics are current, controversial, and have important implications for society. If your topic is currently being discussed on television, in newspapers, in the lounges in your dorm, or around your family’s dinner table, then it’s a current topic. A persuasive speech aimed at getting audience members to wear seat belts in cars wouldn’t have much current relevance, given that statistics consistently show that most people wear seat belts. Giving the same speech would have been much more timely in the 1970s when there was a huge movement to increase seat-belt use.

Many topics that are current are also controversial, which is what gets them attention by the media and citizens. Current and controversial topics will be more engaging for your audience. A persuasive speech to encourage audience members to donate blood or recycle wouldn’t be very controversial, since the benefits of both practices are widely agreed on. However, arguing that the restrictions on blood donation by men who have had sexual relations with men be lifted would be controversial. I must caution here that controversial is not the same as inflammatory. An inflammatory topic is one that evokes strong reactions from an audience for the sake of provoking a reaction. Being provocative for no good reason or choosing a topic that is extremist will damage your credibility and prevent you from achieving your speech goals.

You should also choose a topic that is important to you and to society as a whole. As we have already discussed in this book, our voices are powerful, as it is through communication that we participate and make change in society. Therefore we should take seriously opportunities to use our voices to speak publicly. Choosing a speech topic that has implications for society is probably a better application of your public speaking skills than choosing to persuade the audience that Lebron James is the best basketball player in the world or that Superman is a better hero than Spiderman. Although those topics may be very important to you, they don’t carry the same social weight as many other topics you could choose to discuss. Remember that speakers have ethical obligations to the audience and should take the opportunity to speak seriously.

You will also want to choose a topic that connects to your own interests and passions. If you are an education major, it might make more sense to do a persuasive speech about funding for public education than the death penalty. If there are hot-button issues for you that make you get fired up and veins bulge out in your neck, then it may be a good idea to avoid those when speaking in an academic or professional context.

Choose a persuasive speech topic that you’re passionate about but still able to approach and deliver in an ethical manner.

Michael Vadon – Nigel Farage – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Choosing such topics may interfere with your ability to deliver a speech in a competent and ethical manner. You want to care about your topic, but you also want to be able to approach it in a way that’s going to make people want to listen to you. Most people tune out speakers they perceive to be too ideologically entrenched and write them off as extremists or zealots.

You also want to ensure that your topic is actually persuasive. Draft your thesis statement as an “I believe” statement so your stance on an issue is clear. Also, think of your main points as reasons to support your thesis. Students end up with speeches that aren’t very persuasive in nature if they don’t think of their main points as reasons. Identifying arguments that counter your thesis is also a good exercise to help ensure your topic is persuasive. If you can clearly and easily identify a competing thesis statement and supporting reasons, then your topic and approach are arguable.

Review of Tips for Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

- Not current. People should use seat belts.

- Current. People should not text while driving.

- Not controversial. People should recycle.

- Controversial. Recycling should be mandatory by law.

- Not as impactful. Superman is the best superhero.

- Impactful. Colleges and universities should adopt zero-tolerance bullying policies.

- Unclear thesis. Homeschooling is common in the United States.

- Clear, argumentative thesis with stance. Homeschooling does not provide the same benefits of traditional education and should be strictly monitored and limited.

Adapting Persuasive Messages

Competent speakers should consider their audience throughout the speech-making process. Given that persuasive messages seek to directly influence the audience in some way, audience adaptation becomes even more important. If possible, poll your audience to find out their orientation toward your thesis. I read my students’ thesis statements aloud and have the class indicate whether they agree with, disagree with, or are neutral in regards to the proposition. It is unlikely that you will have a homogenous audience, meaning that there will probably be some who agree, some who disagree, and some who are neutral. So you may employ all of the following strategies, in varying degrees, in your persuasive speech.

When you have audience members who already agree with your proposition, you should focus on intensifying their agreement. You can also assume that they have foundational background knowledge of the topic, which means you can take the time to inform them about lesser-known aspects of a topic or cause to further reinforce their agreement. Rather than move these audience members from disagreement to agreement, you can focus on moving them from agreement to action. Remember, calls to action should be as specific as possible to help you capitalize on audience members’ motivation in the moment so they are more likely to follow through on the action.

There are two main reasons audience members may be neutral in regards to your topic: (1) they are uninformed about the topic or (2) they do not think the topic affects them. In this case, you should focus on instilling a concern for the topic. Uninformed audiences may need background information before they can decide if they agree or disagree with your proposition. If the issue is familiar but audience members are neutral because they don’t see how the topic affects them, focus on getting the audience’s attention and demonstrating relevance. Remember that concrete and proxemic supporting materials will help an audience find relevance in a topic. Students who pick narrow or unfamiliar topics will have to work harder to persuade their audience, but neutral audiences often provide the most chance of achieving your speech goal since even a small change may move them into agreement.

When audience members disagree with your proposition, you should focus on changing their minds. To effectively persuade, you must be seen as a credible speaker. When an audience is hostile to your proposition, establishing credibility is even more important, as audience members may be quick to discount or discredit someone who doesn’t appear prepared or doesn’t present well-researched and supported information. Don’t give an audience a chance to write you off before you even get to share your best evidence. When facing a disagreeable audience, the goal should also be small change. You may not be able to switch someone’s position completely, but influencing him or her is still a success. Aside from establishing your credibility, you should also establish common ground with an audience.

Build common ground with disagreeable audiences and acknowledge areas of disagreement.

Chris-Havard Berge – Shaking Hands – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Acknowledging areas of disagreement and logically refuting counterarguments in your speech is also a way to approach persuading an audience in disagreement, as it shows that you are open-minded enough to engage with other perspectives.

Determining Your Proposition

The proposition of your speech is the overall direction of the content and how that relates to the speech goal. A persuasive speech will fall primarily into one of three categories: propositions of fact, value, or policy. A speech may have elements of any of the three propositions, but you can usually determine the overall proposition of a speech from the specific purpose and thesis statements.

Propositions of fact focus on beliefs and try to establish that something “is or isn’t.” Propositions of value focus on persuading audience members that something is “good or bad,” “right or wrong,” or “desirable or undesirable.” Propositions of policy advocate that something “should or shouldn’t” be done. Since most persuasive speech topics can be approached as propositions of fact, value, or policy, it is a good idea to start thinking about what kind of proposition you want to make, as it will influence how you go about your research and writing. As you can see in the following example using the topic of global warming, the type of proposition changes the types of supporting materials you would need:

- Proposition of fact. Global warming is caused by increased greenhouse gases related to human activity.

- Proposition of value. America’s disproportionately large amount of pollution relative to other countries is wrong .

- Proposition of policy. There should be stricter emission restrictions on individual cars.

To support propositions of fact, you would want to present a logical argument based on objective facts that can then be used to build persuasive arguments. Propositions of value may require you to appeal more to your audience’s emotions and cite expert and lay testimony. Persuasive speeches about policy usually require you to research existing and previous laws or procedures and determine if any relevant legislation or propositions are currently being considered.

“Getting Critical”

Persuasion and Masculinity

The traditional view of rhetoric that started in ancient Greece and still informs much of our views on persuasion today has been critiqued for containing Western and masculine biases. Traditional persuasion has been linked to Western and masculine values of domination, competition, and change, which have been critiqued as coercive and violent (Gearhart, 1979).

Communication scholars proposed an alternative to traditional persuasive rhetoric in the form of invitational rhetoric. Invitational rhetoric differs from a traditional view of persuasive rhetoric that “attempts to win over an opponent, or to advocate the correctness of a single position in a very complex issue” (Bone et al., 2008). Instead, invitational rhetoric proposes a model of reaching consensus through dialogue. The goal is to create a climate in which growth and change can occur but isn’t required for one person to “win” an argument over another. Each person in a communication situation is acknowledged to have a standpoint that is valid but can still be influenced through the offering of alternative perspectives and the invitation to engage with and discuss these standpoints (Ryan & Natalle, 2001). Safety, value, and freedom are three important parts of invitational rhetoric. Safety involves a feeling of security in which audience members and speakers feel like their ideas and contributions will not be denigrated. Value refers to the notion that each person in a communication encounter is worthy of recognition and that people are willing to step outside their own perspectives to better understand others. Last, freedom is present in communication when communicators do not limit the thinking or decisions of others, allowing all participants to speak up (Bone et al., 2008).

Invitational rhetoric doesn’t claim that all persuasive rhetoric is violent. Instead, it acknowledges that some persuasion is violent and that the connection between persuasion and violence is worth exploring. Invitational rhetoric has the potential to contribute to the civility of communication in our society. When we are civil, we are capable of engaging with and appreciating different perspectives while still understanding our own. People aren’t attacked or reviled because their views diverge from ours. Rather than reducing the world to “us against them, black or white, and right or wrong,” invitational rhetoric encourages us to acknowledge human perspectives in all their complexity (Bone et al., 2008).

- What is your reaction to the claim that persuasion includes Western and masculine biases?

- What are some strengths and weaknesses of the proposed alternatives to traditional persuasion?

- In what situations might an invitational approach to persuasion be useful? In what situations might you want to rely on traditional models of persuasion?

Organizing a Persuasive Speech

We have already discussed several patterns for organizing your speech, but some organization strategies are specific to persuasive speaking. Some persuasive speech topics lend themselves to a topical organization pattern, which breaks the larger topic up into logical divisions. Earlier, in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech” , we discussed recency and primacy, and in this chapter we discussed adapting a persuasive speech based on the audience’s orientation toward the proposition. These concepts can be connected when organizing a persuasive speech topically. Primacy means putting your strongest information first and is based on the idea that audience members put more weight on what they hear first. This strategy can be especially useful when addressing an audience that disagrees with your proposition, as you can try to win them over early. Recency means putting your strongest information last to leave a powerful impression. This can be useful when you are building to a climax in your speech, specifically if you include a call to action.

Putting your strongest argument last can help motivate an audience to action.

Celestine Chua – The Change – CC BY 2.0.

The problem-solution pattern is an organizational pattern that advocates for a particular approach to solve a problem. You would provide evidence to show that a problem exists and then propose a solution with additional evidence or reasoning to justify the course of action. One main point addressing the problem and one main point addressing the solution may be sufficient, but you are not limited to two. You could add a main point between the problem and solution that outlines other solutions that have failed. You can also combine the problem-solution pattern with the cause-effect pattern or expand the speech to fit with Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

As was mentioned in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech” , the cause-effect pattern can be used for informative speaking when the relationship between the cause and effect is not contested. The pattern is more fitting for persuasive speeches when the relationship between the cause and effect is controversial or unclear. There are several ways to use causes and effects to structure a speech. You could have a two-point speech that argues from cause to effect or from effect to cause. You could also have more than one cause that lead to the same effect or a single cause that leads to multiple effects. The following are some examples of thesis statements that correspond to various organizational patterns. As you can see, the same general topic area, prison overcrowding, is used for each example. This illustrates the importance of considering your organizational options early in the speech-making process, since the pattern you choose will influence your researching and writing.

Persuasive Speech Thesis Statements by Organizational Pattern

- Problem-solution. Prison overcrowding is a serious problem that we can solve by finding alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

- Problem–failed solution–proposed solution. Prison overcrowding is a serious problem that shouldn’t be solved by building more prisons; instead, we should support alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

- Cause-effect. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-cause-effect. State budgets are being slashed and prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-effect-effect. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to increased behavioral problems among inmates and lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-effect-solution. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals; therefore we need to find alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence is an organizational pattern designed for persuasive speaking that appeals to audience members’ needs and motivates them to action. If your persuasive speaking goals include a call to action, you may want to consider this organizational pattern. We already learned about the five steps of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech” , but we will review them here with an example:

- Hook the audience by making the topic relevant to them.

- Imagine living a full life, retiring, and slipping into your golden years. As you get older you become more dependent on others and move into an assisted-living facility. Although you think life will be easier, things get worse as you experience abuse and mistreatment from the staff. You report the abuse to a nurse and wait, but nothing happens and the abuse continues. Elder abuse is a common occurrence, and unlike child abuse, there are no laws in our state that mandate complaints of elder abuse be reported or investigated.

- Cite evidence to support the fact that the issue needs to be addressed.

- According to the American Psychological Association, one to two million elderly US Americans have been abused by their caretakers. In our state, those in the medical, psychiatric, and social work field are required to report suspicion of child abuse but are not mandated to report suspicions of elder abuse.

- Offer a solution and persuade the audience that it is feasible and well thought out.

- There should be a federal law mandating that suspicion of elder abuse be reported and that all claims of elder abuse be investigated.

- Take the audience beyond your solution and help them visualize the positive results of implementing it or the negative consequences of not.

- Elderly people should not have to live in fear during their golden years. A mandatory reporting law for elderly abuse will help ensure that the voices of our elderly loved ones will be heard.

- Call your audience to action by giving them concrete steps to follow to engage in a particular action or to change a thought or behavior.

- I urge you to take action in two ways. First, raise awareness about this issue by talking to your own friends and family. Second, contact your representatives at the state and national level to let them know that elder abuse should be taken seriously and given the same level of importance as other forms of abuse. I brought cards with the contact information for our state and national representatives for this area. Please take one at the end of my speech. A short e-mail or phone call can help end the silence surrounding elder abuse.

Key Takeaways

- Arguments are formed by making claims that are supported by evidence. The underlying justification that connects the claim and evidence is the warrant. Arguments can have strong or weak warrants, which will make them more or less persuasive.

- Good persuasive speech topics are current, controversial (but not inflammatory), and important to the speaker and society.

- When audience members agree with the proposal, focus on intensifying their agreement and moving them to action.

- When audience members are neutral in regards to the proposition, provide background information to better inform them about the issue and present information that demonstrates the relevance of the topic to the audience.

- When audience members disagree with the proposal, focus on establishing your credibility, build common ground with the audience, and incorporate counterarguments and refute them.

- Propositions of fact focus on establishing that something “is or isn’t” or is “true or false.”

- Propositions of value focus on persuading an audience that something is “good or bad,” “right or wrong,” or “desirable or undesirable.”

- Propositions of policy advocate that something “should or shouldn’t” be done.

- Persuasive speeches can be organized using the following patterns: problem-solution, cause-effect, cause-effect-solution, or Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

- Getting integrated: Give an example of persuasive messages that you might need to create in each of the following contexts: academic, professional, personal, and civic. Then do the same thing for persuasive messages you may receive.

- To help ensure that your persuasive speech topic is persuasive and not informative, identify the claims, evidence, and warrants you may use in your argument. In addition, write a thesis statement that refutes your topic idea and identify evidence and warrants that could support that counterargument.

- Determine if your speech is primarily a proposition of fact, value, or policy. How can you tell? Identify an organizational pattern that you think will work well for your speech topic, draft one sentence for each of your main points, and arrange them according to the pattern you chose.

Bone, J. E., Cindy L. Griffin, and T. M. Linda Scholz, “Beyond Traditional Conceptualizations of Rhetoric: Invitational Rhetoric and a Move toward Civility,” Western Journal of Communication 72 (2008): 436.

Gearhart, S. M., “The Womanization of Rhetoric,” Women’s Studies International Quarterly 2 (1979): 195–201.

Ryan, K. J., and Elizabeth J. Natalle, “Fusing Horizons: Standpoint Hermenutics and Invitational Rhetoric,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 31 (2001): 69–90.

Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.7: Persuasive messages

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 36643

- Melissa Ashman

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University via KPUOpen

A persuasive message is the central message that intrigues, informs, convinces, or calls to action. Persuasive messages are often discussed in terms of reason versus emotion. Every message has elements of ethos, or credibility; pathos, or passion and enthusiasm; and logos, or logic and reason. If your persuasive message focuses exclusively on reason with cold, hard facts and nothing but the facts, you may or may not appeal to your audience. People make decisions on emotion as well as reason, and even if they have researched all the relevant facts, the decision may still come down to impulse, emotion, and desire. On the other hand, if your persuasive message focuses exclusively on emotion, with little or no substance, it may not be taken seriously. Finally, if your persuasive message does not appear to have credibility, the message may be dismissed entirely.

In general, appeals to emotion pique curiosity and get our attention, but some attention to reason and facts should also be included. That doesn’t mean we need to spell out the technical manual on the product on the opening sale message, but basic information about design or features, in specific, concrete ways can help an audience make sense of your message and the product or service. Avoid using too many abstract terms or references, as not everyone will understand these. You want your persuasive message to do the work, not the audience.

Typical format of a persuasive message

The four parts of a persuasive message are shown in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Your persuasive message will compete with hundreds of other messages your audience receives and you want it to stand out (Price, 2005). One effective way to do that is to make sure your attention statement (or hook) and introduction clearly state how your audience will benefit. For example:

- Will the product or service save time or money?

- Will it make them look good?

- Will it entertain them?

- Will it satisfy them?

Regardless of the product or service, the audience is going to consider first what is in it for them. A benefit is what the audience gains by doing what you’re asking them to do and this is central to your persuasive message. They may gain social status, popularity, or even reduce or eliminate something they don’t want. Your persuasive message should clearly communicate the benefits of your product or service (Winston & Granat, 1997).

Strategies for persuasive messages

Your product or service may sell itself, but you may want to consider using some strategies to help ensure your success:

- Start with your greatest benefit . Use it in the headline, subject line, caption, or attention statement. Audiences tend to remember the information from the beginning and end of a message, but have less recall about the middle points. Make your first step count by highlighting the best feature first.

- Take baby steps . Promote, inform, and persuade on one product or service at a time. You want to hear “yes,” and if you confuse the audience with too much information, too many options, steps to consider, or related products or service, you are more likely to hear “no” as a defensive response as the audience tries not to make a mistake. Avoid confusion and keep it simple.

- Know your audience . The more background research you can do on your audience, the better you can anticipate their specific wants and needs and tailor your persuasive message to meet them.

- Lead with emotion, and follow with reason . Gain the audience’s attention with drama, humour, or novelty and follow with specific facts that establish your credibility, provide more information about the product or service, and lead to your call to action.

These four steps can help improve your persuasive messages. Invest your time in planning and preparation, and consider the audience’s needs as you prepare your messages. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) provides an example of a persuasive email message.

In this message, the writer has combined emotion and reason and reinforced their credibility in order to create interest in their service, hopefully leading to a sale.

Price, D. (2005). How to communicate your sales message so buyers take action now! Retrieved from ezinearticles.com/?How-To-Communicate-Your-Sales-Message-So-Buyers-Take-Action-Now!&id=89569.

Winston, W., & Granat, J. (1997). Persuasive advertising for entrepreneurs and small business owners: How to create more effective sales messages . New York, NY: Routledge.

Attribution

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 13.6 “Sales message” in Business English for Success and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.4 Persuasive Messages

Persuasion is an act or process of presenting arguments to move, motivate, or change your audience. Aristotle taught that rhetoric, or the art of public speaking, involves the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion. Persuasion can be implicit or explicit and can have both positive and negative effects. In the professional world honing persuasive strategies is vital to your livelihood when the reward is a sale, a promotion, or merely a regular paycheque.

Persuasion begins with motivation. If persuasion is a process and your audience’s action (e.g., buying a product or service) is the goal, then motivating them to accept an argument or a series of positions leading to the decision that you want them to adopt helps achieve that goal. No matter what, you want your audience to stick around long enough to read your whole piece. How do you manage this magic trick? Simple- you appeal to them! You get to know what sparks their interest, what makes them curious, and what makes them feel understood. Aristotle provided us with three ways to appeal to an audience, and they’re called logos, pathos, and ethos . You’ll learn more about each appeal in the discussion below, but the relationship between these three appeals is also often called the rhetorical triangle as shown in Activity 9.3.

Activity 9.3 | The Rhetorical Triangle

Latin for emotion, pathos is the fastest way to get your audience’s attention. People tend to have emotional responses before logical ones. Be careful though. Too much pathos can make your audience feel emotionally manipulated or angry because they’re also looking for the facts to support whatever emotional claims you might be making so they know they can trust you.

Latin for logic, logos is where those facts come in. Your audience will question the validity of your claims; the opinions you share in your writing need to be supported using science, statistics, expert perspective, and other types of logic. However, if you only rely on logos , your writing might become dry and boring, so even this should be balanced with other appeals.

Latin for ethics, ethos is what you do to prove to your audience that you can be trusted, that you are a credible source of information. (See logos .) It’s also what you do to assure them that they are good people who want to do the right thing. This is especially important when writing an argument to an audience who disagrees with you. It’s much easier to encourage a disagreeable audience to listen to your point of view if you have convinced them that you respect their opinion and that you have established credibility through the use of logos and pathos , which show that you know the topic on an intellectual and personal level.

You can also gain ethos through your use of sources. Reliable, appropriate sources act as expert voices that provide a perspective you don’t have. Layout, graphic design choices, white space, style and tone: all of these factors influence your ethos.

Fundamentals of Business Communication Revised (2022) Copyright © 2022 by Venecia Williams & Nia Sonja is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

give the audience all the information they will need to act on the request. Which of the following is a suitable strategy to persuade the audience in dire situations? direct request. Which of the following is true of problem-solving persuasive messages? They allow you to disarm opposition by means of reasoning.

Problem-solving reports are not considered to be true persuasive messages because they May be written by employees or by consulting companies for clients. If your report uses published sources, you should include

To persuade your audience that your problem solving method is effective and appropriate, you need to provide evidence and rationale for your choices and actions. Evidence can include data, facts ...

There is no one “correct” answer, but many experts have studied persuasion and observed what works and what doesn’t. Social psychologist Robert Cialdini offers us six principles of persuasion that are powerful and effective: Reciprocity. Scarcity. Authority. Commitment and consistency.

Persuasion begins with motivation. If persuasion is a process and your audience’s action (e.g., buying a product or service) is the goal, then motivating them to accept an argument or a series of positions leading to the decision that you want them to adopt helps achieve that goal. If your goal is to convince a pet owner to spay or neuter ...

Foundation of Persuasion. Persuasive speaking seeks to influence the beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors of audience members. In order to persuade, a speaker has to construct arguments that appeal to audience members. Arguments form around three components: claim, evidence, and warrant. The claim is the statement that will be supported by ...

Persuasive messages are often discussed in terms of reason versus emotion. Every message has elements of ethos, or credibility; pathos, or passion and enthusiasm; and logos, or logic and reason. If your persuasive message focuses exclusively on reason with cold, hard facts and nothing but the facts, you may or may not appeal to your audience.

Identify the need (i.e., Problem) Satisfy the need (i.e., Solution to the problem) Present a vision or solution; Take action; This simple organizational pattern can help you focus on the basic elements of a persuasive message when time is short and your performance is critical.

9.4 Persuasive Messages. Persuasion is an act or process of presenting arguments to move, motivate, or change your audience. Aristotle taught that rhetoric, or the art of public speaking, involves the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion. Persuasion can be implicit or explicit and can have both positive and ...