Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $746.00

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Research Anthology on Mental Health Stigma, Education, and Treatment, VOL 1

Purchase options and add-ons.

- ISBN-10 1668433346

- ISBN-13 978-1668433348

- Publisher Medical Information Science Reference

- Publication date March 31, 2021

- Language English

- Dimensions 8.5 x 1 x 11 inches

- Print length 456 pages

- See all details

Product details

- Publisher : Medical Information Science Reference (March 31, 2021)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 456 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1668433346

- ISBN-13 : 978-1668433348

- Item Weight : 2.94 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.5 x 1 x 11 inches

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

About database About data repository

Research Anthology on Mental Health Stigma, Education, and Treatment

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Here are the instructions how to enable JavaScript in your web browser .

This site uses cookies to make them easier to browse. Learn more about how we use cookies .

Advertisement

Interventions to Reduce Stigma Related to Mental Illnesses in Educational Institutes: a Systematic Review

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 05 May 2020

- Volume 91 , pages 887–903, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ahmed Waqas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3772-194X 1 ,

- Salma Malik 2 ,

- Ania Fida 3 ,

- Noureen Abbas 4 ,

- Nadeem Mian 5 ,

- Sannihitha Miryala 6 ,

- Afshan Naz Amray 7 ,

- Zunairah Shah 8 &

- Sadiq Naveed 9

21k Accesses

40 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This investigation reviews the effectiveness of anti-stigma interventions employed at educational institutes; to improve knowledge, attitude and beliefs regarding mental health disorders among students. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist guidelines were followed and protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42018114535). Forty four randomized controlled trials were considered eligible after screening of 104 full-text articles against inclusion and exclusion criteria.

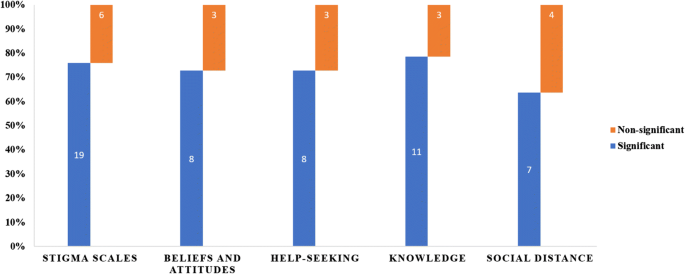

Several interventions have been employed to tackle stigma toward psychiatric illnesses, including education through lectures and case scenarios, contact-based interventions, and role-plays as strategies to address stigma towards mental illnesses. A high proportion of trials noted that there was a significant improvement for stigma (19/25, 76%), attitude (8/11, 72%), helping-seeking (8/11, 72%), knowledge of mental health including recognition of depression (11/14, 78%), and social distance (4/7, 57%). These interventions also helped in reducing both public and self-stigma. Majority of the studies showed that the anti-stigma interventions were successful in improving mental health literacy, attitude and beliefs towards mental health illnesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Promoting Gender Equality: A Systematic Review of Interventions

Michaela Guthridge, Maggie Kirkman, … Melita J. Giummarra

Insiders’ Insight: Discrimination against Indigenous Peoples through the Eyes of Health Care Professionals

Lloy Wylie & Stephanie McConkey

What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review

Antonia Aguirre Velasco, Ignacio Silva Santa Cruz, … Sarah Rowe

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health disorders are prevalent worldwide, with detrimental personal, social and financial consequences [ 1 ]. It is estimated that adult mental and substance disorders account for 7% of all global burden of diseases and 19% of all years lived with disability [ 2 ]. Overall, mental health illnesses account for 16% of the global burden of disease and injury in people aged 10–19 years, with suicide being the third leading cause of deaths in adolescence [ 2 ]. Adolescents with behavioral disorders are particularly vulnerable to social exclusion and stigma, educational difficulties, overall poor health and risk-taking behaviors (e.g. sexual risk taking, substance use and aggression) [ 3 ]. Despite their presentation as a major public health concern, these conditions often go undetected and untreated. And individuals with mental health disorders report distress and poor access to healthcare due to fear of stigma, prejudice and discrimination in the society [ 3 ]. Among adolescents especially, the prevalent stigma in the educational setting, can exacerbate loneliness and isolation, often associated with suicidal behaviors [ 3 ].

Stigma, in general, is conceptualized as a feeling of disgrace, shame, and self-blame that results in social exclusion, isolation, and embarrassment [ 4 ]. Elliot et al., report that branding of individuals with mental illnesses is often associated with deviance, dangerousness and social illegitimacy [ 5 ]. These individuals, therefore, experience “label avoidance” restricting help-seeking and fearing negative reactions from others [ 4 ]. These stigmatizing perceptions toward individuals with mental illnesses can manifest in discriminatory forms such as withholding access to care, coercive treatment, avoidance, and segregated institutions ( structural stigma ) [ 6 ]. Thus, these individuals are burdened by the distress of their symptoms and the distress of the stigma.

The stigma is often divided in two forms; public stigma and self-stigma [ 6 ]. Public stigma is described as the attitude and reaction of general population towards people with mental illnesses while self-stigma corresponds to the internalized shame, guilt and poor self-image caused by acceptance of the societal prejudice [ 6 ]. Unfortunately, stigma towards mental illnesses is prevalent among all strata of our society including medical professionals [ 6 ]. This stigma is often aggravated by the stereotypical and prejudiced portrayal of mental illnesses in the media. Empirical investigations on media reporting suggest that individuals with mental illnesses are shown as deviants: “homicidal maniacs”, weaker individuals, and one with childlike perceptions [ 6 ]. Mental health illnesses and associated stigma lead to a vicious cycle resulting in poor access to mental and physical healthcare, decreased life expectancy, social exclusion in form of academic termination, unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and contact with criminal justice systems [ 7 ].

The issue of stigma toward mental illnesses is even more complex among adolescents- According to De-Luca, research in this domain is scarce (accounting for 3% of research) [ 8 ]. It is important to understand it among youth, delineate processes and barriers especially mental health attitudes and knowledge and help-seeking behaviors [ 8 ]. This is especially important because adolescence is a crucial period in an individual’s psychosocial and emotional development. At this age, the need for peer approval and inclusive social networks dictate how an adolescent cope with the double burden of mental health problems and rejection from classmates [ 8 ]. Understanding the dynamics of stigma and effects of peer perception in educational settings on identity development of the youth with mental illnesses is particularly important. This has been found to be a significant barrier in over 68% of the countries globally in a survey conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) [ 8 ].

The WHO explicitly recommends developing programs to improve stigma and psychiatric outcomes. Recent reviews examining anti-stigma interventions in high-income countries, have shown short-term improvement in knowledge, awareness and in attitude towards mental health illnesses [ 9 ]. Studies measuring long-term effectiveness (beyond four weeks) suggested improvement in attitude and knowledge but these benefits could not translate into improvement in behavioral outcomes [ 9 ]. However, there have been fewer to no evidence synthesis efforts for educational institute -based interventions especially in the low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Therefore, to address this paucity of data, the present review aims to summarize evidence pertaining to anti-stigma interventions for mental illnesses in educational institutes.

This systematic review follows the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist [ 10 ]. Its protocol was registered apriori in PROSPERO (CRD42018114535).

Operational Definitions

Using the framework of consensus study report on The Evidence for Stigma Change , we defined public stigma as societal reaction to an individual’s mental illness [ 11 ]. We included evidence pertaining to all the societal groups irrespective of education, socioeconomic strata or occupation. Self-stigma was defined as internalized feelings of shame, guilt and worthlessness in reaction to societal stigma [ 11 ].

Search Process

To gain an understanding of these interventions in a broader scope, we did not limit ourselves to specific psychiatric diagnoses, and made use of general search terms pertaining to psychiatric illnesses. However, we also included several terms pertaining to common mental disorders among adults and pediatric population to ensure none of the disorders important in the context of global mental health are missed. Eight academic databases including CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Global Health Library, Virtual Health Library, POPLINE, Psycarticles, and Psycinfo and Web of Science, were searched on September 17th, 2018, using search terms noted in Table 1 . No restrictions or database filters were applied regarding language, time period or publication year. The database search was also augmented by manual searching of bibliography of eligible studies.

Study Selection

After automated removal of duplicates from bibliographic records using Endnote, we scrutinized their titles and abstracts against our pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full texts of eligible titles identified in this phase were further scrutinized against the eligibility criteria. This phase was performed by two reviewers working independently from one another, under supervision of a senior reviewer.

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effectiveness of interventions or campaigns in educational institutions (schools, colleges, universities), that were primarily aimed to reduce stigma related to psychiatric disorders. No restriction of age, language, race, gender, ethnicity, geographic location, publication year will be applied. We did not consider any interventions which were not conducted in context of academic institutions.

Data Extraction & Analysis

Data extraction pertaining to eligible studies was performed using a standardized template by one reviewer, including bibliographic details, institutional and regional affiliations, characteristics of the study sample, and characteristics of interventions. Characteristics of study sample included the characteristics of the population of interest, age and geographical scope. While the characteristics of intervention focused on the targeted diagnosis, names of scales utilized to assess stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illnesses, and the primary outcomes measured. The interventions were stratified in three groups, according to their deliver agents: medical doctors, nurses, and psychology professionals. We also classified the interventions according to their theoretical orientations and noted the content of interventions. Later, a careful analysis of the theoretical orientation and content of interventions by the senior authors, based on an adapted version of matching and distillation framework. This enabled us to unpack these interventions into common elements or strategies employed.

Risk of bias in the studies was assessed using the Cochrane’s tool for assessment of risk of bias in RCTs across several matrices: a) randomization procedure b) allocation concealment c) blinding of participants and personnel d) blinding of outcome assessors e) attrition bias f) Other biases. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed by two independent reviewers and any disagreement were resolved by discussion or the guidance of senior reviewer. Unfortunately, due to methodological and statistical heterogeneity, we deferred the application of meta-analysis, to yield the pooled effectiveness of these interventions in reduction of stigma towards mental illnesses.

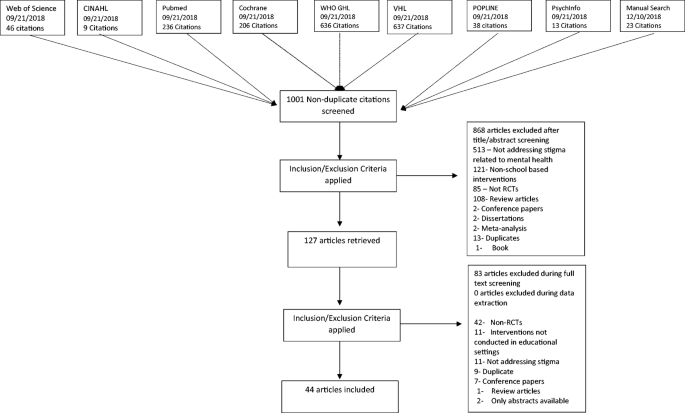

Our academic searches yielded a total number of 978 non-duplicate references, which were screened for eligibility based on their titles and abstracts. Out of these, 104 full texts were retained after exclusion of 868 citations. Thereafter, 44 RCTs s were deemed eligible after a careful review of their full texts, against the inclusion and exclusion criteria set apriori. Detailed results have been presented in PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Study Characteristics

The eligible publications were published between the years 1998 and 2018. A majority of these interventions were conducted in high income countries and regions including USA ( n = 15), Australia ( n = 7), Greece ( n = 4), UK ( n = 3), Germany (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Portugal (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 1), Hong Kong (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), Japan ( n = 2), and Korea (n = 1). While only 6 studies were conducted in upper and lower middle-income countries including China (n = 2), Russia ( n = 2) Nigeria (n = 1) and Brazil (n = 1). Low income countries did not contribute to any RCTs in this domain.

Setting & Delivery of Interventions

Most of the evidence was from RCTs conducted in the context of urban settings ( n = 27), followed by mixed settings ( n = 5), suburban (n = 4), and rural (n = 1). The geographical region was unspecified in seven studies. A higher proportion of interventions ( n = 20) were conducted in school settings (primary school, secondary schools, high school). This was followed by graduate schools/university setting ( n = 6), undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in psychology courses (n = 5), non-psychology undergraduate setting ( n = 3), and adult schools (n = 2). Six studies were conducted in medical schools (n = 3) and nursing schools (n = 3). Among these studies, 25 were conducted in adults or predominantly adult population, 18 in adolescents or predominantly adolescent population, and one in children. The age ranged varied widely with lowest mean age of 13 years [ 12 ] and highest was 43.1 years [ 13 ].

Quality Rating

Random sequence generation was at a high/unclear risk of bias among 22 trials and allocation concealment (29 RCTs). Frequencies of studies reporting a high risk/unclear across other domains of Cochrane risk of bias tool were: blinding of outcome assessors ( n = 35), blinding of participants and personnel ( n = 31), attrition bias ( n = 14), other sources of bias ( n = 5), and selective reporting ( n = 1). A total of 35 studies were rated as having a high risk of overall bias i.e. ≥ 3 matrices of risk of bias tool were rated as having unclear or high risk of bias for these studies (Figs. 2 and 3 ). Figure 2 presents a clustered bar chart exhibiting frequencies of high, unclear and low risk bias across all matrices of Cochrane risk of bias tool.

Risk of Bias Graph

Mental health conditions targeted in stigma reduction interventions

Mental Health Conditions

Mental health illnesses, in general, were the target of these interventions in 24 studies whereas six studies targeted depression. Other targeted diagnoses were psychosis and schizophrenia ( n = 6), autism spectrum disorder ( n = 2), anxious-ambivalent attachment ( n = 1), anorexia nervosa (n = 1), and suicide (n = 1). One study focused on both depression and Tourette syndrome whereas one study addressed depression and schizophrenia. One intervention addressed engagement in psychotherapy treatment. A summary of mental health condition targeted is mentioned in fig. 3 .

Intervention Characteristics

Delivery agents of interventions included researchers ( n = 17), specialist psychiatrists, and psychologists ( n = 7), trained mental health professionals (n = 6), school teachers/course instructors ( n = 4), graduate students ( n = 2), and peers with lived experiences (n = 2) and researchers and teachers as delivery agent (n = 1). This information was missing for five studies. Numbers of sessions ranged from 1 to 8 sessions where a high proportion of interventions ( n = 25) were delivered in only one session. The numbers of sessions were unspecified in seven studies. Studies delivered the following number of interventions: two sessions(n = 4), three session (n = 4), four sessions (n = 1) and six sessions (n = 2) and eight sessions (n = 1). The duration for whole program was categorized into studies with duration of one day ( n = 11), one day to one week ( n = 8), one to four weeks ( n = 3), and longer than one month ( n = 20). The duration was not mentioned in one study [ 14 ] while another study had mixed duration depending on the type of intervention employed [ 15 ]. The longest duration of an intervention was 48 weeks [ 16 ]. The duration for each session varied from 20 min to 12 h.

Strategies & Elements of Interventions

These stigma reduction interventions constituted several different strategies as summarized in fig. 4 , most common of which were psychoeducation through lectures and discussion with mental health professionals and use of case vignettes and scenario-based interventions. Psychoeducation was also delivered via online platforms including website messages, video-based instructions, and educational short messaging service (SMS). Another important strategy highlighted in this review was contact-based learning where two most important intervention elements were role play and contact-based learning with individuals struggling with mental illnesses. The included interventions used either one teaching method or a mix of the above-mentioned.

Summary of strategies employed in stigma reduction interventions

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation was employed in 25 studies using a variety of delivery techniques, mostly based on etiological models of psychiatric illnesses. These interventions educated participants about different attributes of mental health disorders such as epidemiological factors, clinical features, course of illnesses, and available treatment options. They were delivered through didactic lectures [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ], photographic images of billboard messages [ 14 ], short educational messages [ 25 , 26 ], video messages [ 27 ], structured courses and workshops for students [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ], and distribution of booklets and slideshows [ 29 ]. Some of authors utilized a multimodal approach for delivering their interventions, for instance, Papish et al. (2013) structured a course on different mental illnesses using teaching methods such as didactic teaching, case-based teaching with group discussions, and an optional movie night [ 28 ]. Pereira and colleagues (2014) used a mixed approach by using tutorials, videos, interactive discussion, web conference, and written text support to educate participants [I3]. A few of these interventions provided an overview of etiology of mental health disorders; biogenetic, biochemical, neurobiological, biopsychosocial, and contextual factors. Banntanye et al. [ 17 ] formulated an educational intervention based on genetic and heritability of mental health disorders as well as a biopsychosocial model involving a complex interplay of biological, social, and psychological factors [ 17 ]. Two more models were part of several interventions, for instance, the contextual model linked complicated life situations with etiology of mental health disorders and biomedical factors where neurochemical changes in the brain were studied as a cause of psychiatric disorders [ 30 ]. Using a similar model, Han and colleagues presented neurobiological factors as a cause of mental health disorders, in their interventions [ 19 ].

Bespoke Multimodal Stigma Reduction Interventions

Three studies used Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) [ 31 , 32 , 33 ] as a structured training module to address risk factors and clinical features of common mental health disorders including depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, psychosis, and eating disorders. This intervention program also educated participants on strategies to assist someone experiencing mental health crises. Two interventions tested the effectiveness of health education tools, the fotonovlea or Secret Feelings that addressed misconceptions and stigmatizing attitudes through posed photographs, captions, and soap opera narratives [ 34 , 35 ]. The Same or Not Same intervention focused on education about schizophrenia followed by an opportunity to contact with individuals struggling with schizophrenia. In the Video-Education Intervention, a video was followed by educational message. In this intervention, there was information about the cause, timeline, course of illness, and different myths [ 36 ]. In a classroom-based intervention used in two studies, projective cards were used to understand misperceptions about mental illnesses and discussion to overcome these misperceptions was carried out. In last part, patient’s narratives and role of media were also added [ 37 , 38 ].

Case vignettes or scenario-based techniques were employed in six interventions to enhanced understanding of different aspects of mental health disorders [ 15 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Mann et al. evaluated change in stigmatizing attitudes by comparing scenario-based teaching to provide an opportunity to read education material on mental illnesses [ 15 ]. Similar intervention was carried out by using case vignettes [ 40 ] and documentary film [ 42 ] to address stigma. In another intervention, participants were delivered a lecture on schizophrenia whereas second group had a scenario-based activity of four individuals with schizophrenia in remission [ 39 ]. It highlights the living arrangements, daily activities, needs, interests and social support system of individuals with schizophrenia [ 39 ]. Nam and colleagues (2015) used documentary to create stigma manipulating scenarios among college students with anxious-ambivalent attachment [ 42 ]. In another study, the intervention group received didactic lectures regarding factual knowledge about mental health and illness followed by case vignettes. The myths associated with mental illness, positive attitudes toward persons with mental illness, and resources to receive mental health care were examined during a group activity [ 43 ].

Contact-based interventions were assessed in 10 studies by using direct interaction with patients [ 12 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ] and filmed or video techniques [ 12 , 45 , 48 , 51 , 52 ]. In an intervention, two service users on DVD described personal view of mental health and stigma followed by fact-based experience in nine key areas related to mental health disorders [ 45 ]. In Live intervention group, this exercise was conducted in live sessions whereas the control interventions delivered information about mental health and related stigma through a lecture [ 45 ]. In Our Own Voice (IOOV) , two group facilitators with history of mental health disorders addressed five components including “Dark Days, Acceptance, Treatment, Coping Mechanism, and Success. It also had corresponding videotaped sessions for each component [ 46 , 47 ]. The eBridge intervention was structured on personalized feedback about symptoms in individuals with history of suicidal behaviors along with access to resources based on the principles of motivational interviewing [ 53 ]. Self-affirmation psychotherapy was provided in a study by Lannin and colleagues [ 54 ]. In this program, an individual with mental illness is advised to repeat a positive statement or set of such statements about the self on a regular basis to inspire positive view of the self and reduce negative thinking, or low self-esteem [ 54 ]. Chisholm and colleagues (2016) work especially among adolescents concluded that educational interventions provide far more promising results than contact-based interventions [ 44 ]. Although not consistent with previous literature reporting this comparison [ 44 ], Chrisholm et al., argue for a different teaching approach for adolescents keeping in view their level of maturation, influence of the media, and that the information processing and understanding of mental illnesses differ among adolescents, as proposed in several conceptual frameworks [ 44 ].

The eligible studies reported effectiveness of these intervention on a heterogeneous body of scales, which measured stigma toward psychiatric illnesses, pre and post knowledge among participants, attitudinal and intentional changes, and recognition of psychiatric symptomatology. Moreover, help-seeking practices were also measured in these interventions. A lot of importance was placed on public stigma rather than self-stigma. The most frequent outcome was stigma ( n = 25), followed by changes in knowledge levels (n = 25), attitude ( n = 11), help-seeking (n = 11), social distance ( n = 9), and recognition and literacy regarding depression ( n = 5). Majority of studies reported an improvement in stigmatizing attitudes towards mental health disorders with improvement in both public and self-stigma (Fig. 5 ).

Proportion of studies demonstrating reduction in stigma related outcomes

Among 25 studies addressing stigma, where a higher proportion ( n = 19) studies reported a significant improvement in stigma levels at the study endpoint. In a study, comparing biogenetic intervention with a multifactorial intervention, there was no difference among both intervention groups from baseline line to study endpoint [ 17 ]. However, there was a significant improvement among these intervention groups from the control group. While deciphering between personal and public stigma, five studies reported stigma-related outcomes for these two concepts (personal = 3, public = 2) with only one study showing non-significant improvement [ 33 ]. Another study saw improvement at the first timepoint, but it failed to last until second visit. Out of five studies showing non-significant or no improvement, three reported non-significant change [ 14 , 26 , 40 ] whereas two reported no change from baseline to study endpoint [ 23 , 47 ].

The study on biological anti stigma intervention by Boucher and colleagues (2014) attributed non-significant improvement in stigma scores to the conceptualization of depression in as a brain disease whereas depression results from various biolopsychological factors [ 14 ]. Two studies using psychoeducation as a tool of change pointed out that lack of significant improvement in stigma is possibly due to sole use of educational interventions [ 23 , 26 ]. Pinto-Foltz and colleagues had a smaller sample size resulting in the lack of significant improvement in stigma scores [ 47 ].

Beliefs and Attitudes

The attitude was reported in 11 studies with improvement in eight studies at the study endpoint compared to baseline. One study reported improvement in authoritarianism and social restrictiveness (sub-scales of Community Attitudes Toward Mental Illness scale) while benevolence and community mental health ideology subscales failed to show significant improvements [ 42 ]. In remaining three studies, there was non-significant or lack of improvement. The duration of program has limited impact on the favorable results as one intervention had duration of three days [ 43 ]. The two other studies had duration of one [ 24 ] and eight weeks [ 32 ]. Winkle et al. (2017) reported small effect size for flyer or control group and medium effect size for the experimental group [ 22 ]. After a psychiatry clerkship, medical students reported improvement in stigmatizing attitudes but there was no improvement in attributions regarding responsibility and readiness to provide care to patients with mental illnesses [ 50 ]. Moreover, the lack of educational intervention may not be sufficient to change beliefs [ 26 , 36 ]. This underscores the need to strengthen medical school clerkships as well as enhancing the ways to interact with this patient population.

Help-Seeking

Intention and attitude to seek help were reported in 11 studies with improvement in eight studies. One study reported similar improvement among the intervention and control groups because the control group also received psychoeducation through brochures on depression [ 35 ]. In remaining three studies, there was non-significant or lack of improvement post-intervention [ 23 ]. In a rural-area based study, there was improvement in stigma and attitudes but it failed to materialize this change into help-seeking behaviors [ 23 ]. It is worth noting that adolescents in rural areas were more likely to turn to family and friends than seeking help from professionals such as school counselors [ 23 ]. In another study, the lack of improvement was regarded to inadequate dosage or duration of the program among adolescents [ 29 ]. The causation of depression as “neurological disease” was also a barrier and may have prevented college students from seeking help [ 14 ].

Knowledge of Mental Health Disorders and Treatment

The knowledge of mental health disorder and treatment was assessed in nine studies and depression literacy in five studies. Out of these 14 studies, 11 reported significant improvement in help-seeking with no improvement in three studies. It is interesting to note that two studies reported improvement in knowledge regarding depressive disorders and relevant treatment but engagement in these treatments was non-satisfactory, with a drop rate exceeding 44% [ 23 , 29 ]. The lack of improvement in three studies was reported due to lack of past experience or contact with individuals with mental illnesses [ 33 , 47 ]. In study by Pinto-Foltz, the improvement was more noticeable at 4 and 8-week timepoints among intervention group, owing to past exposure of participants in control group to mental health information [ 4 ]. For Depression Fotonovela intervention, lack of difference in improvement among both experimental and control groups was due to ceiling effect and higher baseline knowledge scores [ 34 ].

Social Distance

The social distance was assessed in seven studies with four studies reporting favorable results. Majority of the studies with favorable results had two important components including opportunity to contact with individuals with mental illness ( n = 3) and participants with a background in medicine or nursing ( n = 4). In one of these studies, a combination of two education strategies didactic education and video group fared better than the education group alone. Three of the studies reported a non-significant outcome; these studies lacked contact with individuals diagnosed with mental health disorders. Moreover, participants in these interventions were adult individuals with no background in relevant professions [ 34 ], middle school students, or students enrolled in psychology courses [ 55 ].

This article reviews the evidence for various aspects of stigma towards mental health disorders in educational settings. These interventions were carried out in university, college, and school settings, targeting a wide range of mental health disorders. Duration of intervention varied widely with most of the interventions lasting for more than four weeks. For outcome measure, majority of studies reported significant improvement for stigma (19/25, 76%), attitude (8/11, 72%), help-seeking (8/11, 72%), knowledge of mental health including recognition of depression (11/14, 78%), and social distance (4/7, 57%). It is worthwhile to appreciate that all these outcomes measure are intercalated and have a directional effect on each other.

Most of the studies included in this review focused on reduction of public stigma rather than self-stigma, two different yet highly intercalated concepts. The reviewed interventions targeted one or more of the core stigmatizing behaviors especially fear and exclusion and authoritarianism that people with mental illnesses face and inspire benevolence and compassion among the intervention recipients [ 56 ]. This was done through different strategies, most frequently being psychoeducation through didactic lectures. Other strategies were contact-based interventions, and role-plays to address stigma towards mental illnesses. Reduction of self-stigma was done through a specialized program of self-affirmation therapy, to inspire moral and adaptive adequacy of the self, with a main aim to inspire positive view of self [ 54 ].

All of these interventions followed the recommendations proposed by Corrigan et al., who recommended three ways to combat public stigma: protest, education, and contact to combat the existing stigma [ 56 ]. The latter approaches were employed frequently, however, protest in response to the stigmatizing environment propagated by public statements, media reports, and advertisements was absent in these initiatives [ 56 ]. In addition, it is also imperative to engage health care providers, stakeholders, policymakers, for development of campus-based policies combating stigma [ 57 ]. We did not find any interventions designed at the policy level as well as the system level or reporting their effectiveness and wide-ranging implications and socioeconomic benefits.

A plethora of research in recent decades has shown that stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illnesses are strongly driven by sociocultural and religious factors, as well as individual factors especially empathy and experience and education levels [ 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 ]. This is particularly relevant in context of low- and middle-income countries where such attitudes and beliefs toward mental illnesses are prevalent even among the learned. For instance, the belief in djinni possession, black magic and divine punishment as causes of mental illnesses are rampant in the Indian subcontinent. This requires the development of very culture specific interventions in these countries. And yet only one of the interventions targeting stigma toward mental illnesses has been developed in these countries [ 62 ]. This is a major gap that must be addressed by development of interventions that aim to mitigate negative cultural and social norms as well as inspire benevolence toward people with mental illnesses. It can be argued that development, testing and implementation of relevant interventions in poorer nations can foster an alternative and correct view of mental illness resulting in improved knowledge and linkage to services.

This systematic review has several strengths. An electronic search of academic databases combined with manual searching for references provides an exhaustive search for relevant evidence. It provides an overview of RCTs of interventions targeting stigma towards mental health in educational settings as well as the strategies used in each intervention and different components of these interventions. Combined with a qualitative assessment of the theoretical orientation of these intervention as well as assessment of risk of bias, makes this review an important source for development and testing of future interventions in this area. However, this review also has several limitations. Due to heterogeneity, varying intervention design, and different outcome measures, meta-analysis could not be performed. It is also important to consider the higher risk of bias in included studies while interpreting the results of these studies. These interventions were important in challenging the stereotypes and prejudice by providing an opportunity of social contact with individuals with mental illnesses, engaging in myth-busting, and increasing awareness of mental illnesses through education via text, lecture, or film [ 7 ]. However, due to lack of meta-analytic evidence, it is difficult to ascertain if a single component intervention is any better than its multi-component counterparts such as DVD or direct contact group work better than other. Although, generally a greater improvement was reported with comprehensive approaches to combat stigma [ 45 ].

This review provides some promising empirical support for anti-stigma interventions regarding mental health disorders aimed at students. These interventions were somewhat successful in reducing both self and public stigma. This highlights the need for progressively thorough, better-quality evaluations conducted with more diverse samples of the population. As it appears that short-term interventions often only have a transient effect, the implication is that researchers should study longer term interventions and to use the intervening time and outcome data to improve the interventions along the way. Future research should explore to what extent changes in students’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs can result in earlier help seeking.

Sickel AE, Seacat JD, Nabors NA. Mental health stigma: impact on mental health treatment attitudes and physical health. J Health Psychol. 2019;24(5):586–99.

PubMed Google Scholar

Rehm J, Shield KD. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(2):10.

World Health Organization. (2019). Adolescent mental health. Retrieved 15 December 2019, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

Schomerus G, Stolzenburg S, Freitag S, Speerforck S, Janowitz D, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Stigma as a barrier to recognizing personal mental illness and seeking help: a prospective study among untreated persons with mental illness. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269(4):469–79.

Elliott GC, Ziegler HL, Altman BM, Scott DR. Understanding stigma: dimensions of deviance and coping. Deviant Behav. 1982;3(3):275–300.

Google Scholar

Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2002;1(1):16–20.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gronholm PC, Henderson C, Deb T, Thornicroft G. Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: the state of the art. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(3):249–58.

World Health Organization. Department of Mental Health, Substance Abuse, World Psychiatric Association, International Association for Child, Adolescent Psychiatry, & Allied Professions. (2005). Atlas: child and adolescent mental health resources: global concerns, implications for the future. World Health Organization.

Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, Rose D, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1123–32.

A. Liberati, D. G. Altman, J. Tetzlaff, C. Mulrow, P. C. Gøtzsche, J. P. Ioannidis, ... & D Moher. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of internal medicine, 151(4), W-65.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: the evidence for stigma change: National Academies Press; 2016.

Ranson NJ, Byrne MK. Promoting peer acceptance of females with higher-functioning autism in a mainstream education setting: a replication and extension of the effects of an autism anti-stigma program. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(11):2778–96.

Pereira CA, Wen CL, Miguel EC, Polanczyk GV. A randomised controlled trial of a web-based educational program in child mental health for schoolteachers. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(8):931–40.

Boucher LA, Campbell DG. An examination of the impact of a biological anti-stigma message for depression on college students. J Coll Stud Psychother. 2014;28(1):74–81.

Mann CE, Himelein MJ. Putting the person back into psychopathology: an intervention to reduce mental illness stigma in the classroom. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(7):545–51.

Yamaguchi S, Koike S, Ojio Y, Shimada T, Watanabe KI, Ando S. Filmed social contact v. internet self-learning to reduce mental health-related stigma among university students in Japan: a randomized controlled trial. Early intervention in psychiatry, 8. 2014.

Bannatyne A, Stapleton P. Educating medical students about anorexia nervosa: a potential method for reducing the volitional stigma associated with the disorder. Eat Disord. 2015;23(2):115–33.

Giannakopoulos G, Assimopoulos H, Petanidou D, Tzavara C, Kolaitis G, Tsiantis J. Effectiveness of a school-based intervention for enhancing adolescents' positive attitudes towards people with mental illness. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):79–83.

Han DY, Chen SH. Reducing the stigma of depression through neurobiology-based psychoeducation: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68(9):666–73.

Kosyluk KA, Al-Khouja M, Bink A, Buchholz B, Ellefson S, Fokuo K, et al. Challenging the stigma of mental illness among college students. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(3):325–31.

Sakellari E, Lehtonen K, Sourander A, Kalokerinou-Anagnostopoulou A, Leino-Kilpi H. Greek adolescents' views of people with mental illness through drawings: mental health education's impact. Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16(3):358–64.

Winkler P, Janoušková M, Kožený J, Pasz J, Mladá K, Weissová A, et al. Short video interventions to reduce mental health stigma: a multi-Centre randomised controlled trial in nursing high schools. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(12):1549–57.

Swartz K, Musci RJ, Beaudry MB, Heley K, Miller L, Alfes C, et al. School-based curriculum to improve depression literacy among US secondary school students: a randomized effectiveness trial. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1970–6.

Sharp W, Hargrove DS, Johnson L, Deal WP. Mental health education: an evaluation of a classroom based strategy to modify help seeking for mental health problems. J Coll Stud Dev. 2006;47(4):419–38.

Finkelstein J, Lapshin O, Wasserman E. Randomized study of different anti-stigma media. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(2):204–14.

Kashihara J. Examination of stigmatizing beliefs about depression and stigma-reduction effects of education by using implicit measures. Psychol Rep. 2015;116(2):337–62.

Esters IG, Cooker PG, Ittenbach RF. Effects of a unit of instruction in mental health on rural adolescents' conceptions of mental illness and attitudes about seeking help. Adolescence. 1998;33(130):469–76.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Papish A, Kassam A, Modgill G, Vaz G, Zanussi L, Patten S. Reducing the stigma of mental illness in undergraduate medical education: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):141.

Perry Y, Petrie K, Buckley H, Cavanagh L, Clarke D, Winslade M, et al. Effects of a classroom-based educational resource on adolescent mental health literacy: a cluster randomised controlled trial. J Adolesc. 2014;37(7):1143–51.

Rusch LC, Kanter JW, Brondino MJ. A comparison of contextual and biomedical models of stigma reduction for depression with a nonclinical undergraduate sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(2):104–10.

Burns S, Crawford G, Hallett J, Hunt K, Chih HJ, Tilley PM. What’s wrong with John? A randomised controlled trial of mental health first aid (MHFA) training with nursing students. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):111.

Hart LM, Morgan AJ, Rossetto A, Kelly CM, Mackinnon A, Jorm AF. Helping adolescents to better support their peers with a mental health problem: a cluster-randomised crossover trial of teen mental health first aid. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;52(7):638–51.

Lipson SK, Speer N, Brunwasser S, Hahn E, Eisenberg D. Gatekeeper training and access to mental health care at universities and colleges. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(5):612–9.

Cabassa LJ, Oh H, Humensky JL, Unger JB, Molina GB, Baron M. Comparing the impact on Latinos of a depression brochure and an entertainment-education depression fotonovela. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(3):313–6.

Unger JB, Cabassa LJ, Molina GB, Contreras S, Baron M. Evaluation of a fotonovela to increase depression knowledge and reduce stigma among Hispanic adults. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(2):398–406.

Chan JY, Mak WW, Law LS. Combining education and video-based contact to reduce stigma of mental illness:“the same or not the same” anti-stigma program for secondary schools in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(8):1521–6.

Economou M, Louki E, Peppou LE, Gramandani C, Yotis L, Stefanis CN. Fighting psychiatric stigma in the classroom: the impact of an educational intervention on secondary school students’ attitudes to schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58(5):544–51.

Economou M, Peppou LE, Geroulanou K, Louki E, Tsaliagkou I, Kolostoumpis D, et al. The influence of an anti-stigma intervention on adolescents' attitudes to schizophrenia: a mixed methodology approach. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2014;19(1):16–23.

Chung KF, Chan JH. Can a less pejorative Chinese translation for schizophrenia reduce stigma? A study of adolescents’ attitudes toward people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(5):507–15.

Howard KA, Griffiths KM, McKetin R, Ma J. Can a brief biologically-based psychoeducational intervention reduce stigma and increase help-seeking intentions for depression in young people? A randomised controlled trial. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2018;30(1):27–39.

Nam SK, Choi SI, Lee SM. Effects of stigma-reducing conditions on intention to seek psychological help among Korean college students with anxious-ambivalent attachment. Psychol Serv. 2015;12(2):167–76.

Vila-Badia R, Martínez-Zambrano F, Arenas O, Casas-Anguera E, García-Morales E, Villellas R, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention for reducing social stigma towards mental illness in adolescents. World journal of psychiatry. 2016;6(2):239–47.

Oduguwa AO, Adedokun B, Omigbodun OO. Effect of a mental health training programme on Nigerian school pupils’ perceptions of mental illness. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2017;11(1):19.

Chisholm K, Patterson P, Torgerson C, Turner E, Jenkinson D, Birchwood M. Impact of contact on adolescents’ mental health literacy and stigma: the SchoolSpace cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009435.

Clement S, van Nieuwenhuizen A, Kassam A, Flach C, Lazarus A, De Castro M, et al. Filmed v. live social contact interventions to reduce stigma: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(1):57–64.

Corrigan PW, Rafacz JD, Hautamaki J, Walton J, Rüsch N, Rao D, et al. Changing stigmatizing perceptions and recollections about mental illness: the effects of NAMI’s in our own voice. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(5):517–22.

Pinto-Foltz MD, Logsdon MC, Myers JA. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a knowledge-contact program to reduce mental illness stigma and improve mental health literacy in adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(12):2011–9.

Staniland JJ, Byrne MK. The effects of a multi-component higher-functioning autism anti-stigma program on adolescent boys. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(12):2816–29.

Campbell M, Shryane N, Byrne R, Morrison AP. A mental health promotion approach to reducing discrimination about psychosis in teenagers. Psychosis. 2011;3(1):41–51.

Chung KF. Changing the attitudes of Hong Kong medical students toward people with mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(11):766–8.

Gonçalves M, Moleiro C, Cook B. The use of a video to reduce mental health stigma among adolescents. Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;5(3):204–11.

Koike S, Yamaguchi S, Ojio Y, Ohta K, Shimada T, Watanabe K, et al. A randomised controlled trial of repeated filmed social contact on reducing mental illness-related stigma in young adults. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(2):199–208.

King CA, Eisenberg D, Zheng K, Czyz E, Kramer A, Horwitz A, et al. Online suicide risk screening and intervention with college students: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(3):630–6.

Lannin DG, Guyll M, Vogel DL, Madon S. Reducing the stigma associated with seeking psychotherapy through self-affirmation. J Couns Psychol. 2013;60(4):508–19.

Woods DW, Marcks BA. Controlled evaluation of an educational intervention used to modify peer attitudes and behavior toward persons with Tourette’s syndrome. Behav Modif. 2005;29(6):900–12.

Rüsch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(8):529–39.

Byrne P. Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6(1):65–72.

Waqas A, Zubair M, Ghulam H, Ullah MW, Tariq MZ. Public stigma associated with mental illnesses in Pakistani university students: a cross sectional survey. PeerJ. 2014;2:e698.

Haddad M, Waqas A, Qayyum W, Shams M, Malik S. The attitudes and beliefs of Pakistani medical practitioners about depression: a cross-sectional study in Lahore using the revised depression attitude questionnaire (R-DAQ). BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):349.

Haddad M, Waqas A, Sukhera AB, Tarar AZ. The psychometric characteristics of the revised depression attitude questionnaire (R-DAQ) in Pakistani medical practitioners: a cross-sectional study of doctors in Lahore. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):333.

Waqas A, Naveed S, Makhmoor A, Malik A, Hassan H, Aedma KK. Empathy, experience and cultural beliefs determine the attitudes towards depression among Pakistani medical students. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56(1):65–74.

Choudhry FR, Mani V, Ming LC, Khan TM. Beliefs and perception about mental health issues: a meta-synthesis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2807–18.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Population Health Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Ahmed Waqas

Program Director: Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Fellowship, Institute of Living/Hartford Healthcare, Hartford, CT, USA

Salma Malik

King Edward Medical University, Lahore, Pakistan

FMH College of Medicine & Dentistry, Lahore, Pakistan

Noureen Abbas

Mental Health Counselor, PICACS, Washington, USA

Nadeem Mian

Integrated Psychiatric Consultants, Kansas, KS, USA

Sannihitha Miryala

Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan

Afshan Naz Amray

Weiss Memorial Hospital, Illinois, Chicago, USA

Zunairah Shah

Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas, USA

Sadiq Naveed

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ahmed Waqas .

Ethics declarations

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This information is not applicable because this is a review article.

Informed Consent

Additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Waqas, A., Malik, S., Fida, A. et al. Interventions to Reduce Stigma Related to Mental Illnesses in Educational Institutes: a Systematic Review. Psychiatr Q 91 , 887–903 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09751-4

Download citation

Published : 05 May 2020

Issue Date : September 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09751-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Institutions

- Mental health

- Interventions

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Strategies to Reduce Mental Illness Stigma: Perspectives of People with Lived Experience and Caregivers

Associated data.

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due institutional policy but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Background: Reducing the stigma surrounding mental illness is a global public health priority. Traditionally, anti-stigma campaigns were led by mental health professionals/organisations and had an emphasis on increasing mental health literacy. More recently, it has been argued that people with lived experience have much to contribute in terms of extending and strengthening these efforts. The purpose of this paper was to elicit views and suggestions from people with lived experience (PWLE) as well as from informal caregivers of people with mental health conditions, on effective strategies to combat the stigma surrounding mental illness. Methods: Six focus group discussions (FGDs) were carried out with PWLE recruited at outpatient services at the Institute of Mental Health, Singapore, and five FGDs were carried out with informal caregivers who responded to advertisements for the study between March and November 2018. In all, the sample comprised 42 PWLE and 31 caregivers. All the FGDs were transcribed verbatim and were analysed using thematic analysis. A pragmatic approach was adopted for the study, and the researchers did not assume any particular philosophical orientation. Results: Four overarching themes depicting strategies to combat stigma were identified through thematic analysis. They were (1) raising mental health awareness, (2) social contact, (3) advocacy by influential figures or groups, and (4) the legislation of anti-discriminatory laws. Conclusions: These strategies were in line with approaches that have been used internationally to disrupt the process of stigma. Our study has further identified nuanced details on how these strategies can be carried out as well as possible areas of priority in the Singapore landscape.

1. Introduction

The stigma of living with a mental health condition has been described as being worse than the experience of the illness itself [ 1 ]. The aversive reactions that members of the general population have towards people with mental illness is known as public stigma and can be understood in terms of (i) stereotypes, (ii) prejudice, and (iii) discrimination [ 2 ]. Common stereotypes associated with people with mental health conditions are that they are dangerous, incompetent, and weak in character. Prejudice refers to the agreement with these stereotypes, while discrimination refers to behavioural reactions to these prejudices [ 3 ].

Beyond the interpersonal manifestations of public stigma towards people with mental health conditions, societal-level conditions such as institutional policies and practices and cultural norms have also been found to be biased against people with mental health conditions, resulting in a lack of opportunities and resources being afforded to them [ 4 ]. These socio-political disinclinations, known as structural stigma, result in people with mental health conditions being excluded from employment, living in unstable and unsafe conditions, being disqualified from health insurance, and being subjected to coercive hospitalisation and treatment [ 5 , 6 ]. The deprivation of opportunities and poor-quality resources provided to those with mental health conditions have severe bearings, as evidenced by the gross overrepresentation of individuals with mental health conditions in the criminal justice system and among those living in poverty [ 7 ]. People with mental health conditions also have significantly higher morbidity and mortality rates [ 8 ], and consequent to all the above, have a lower quality of life compared to the general population [ 9 , 10 ].

Through repeated encounters with public and structural stigma, individuals with mental health conditions are inclined to internalise these reactions, a phenomenon known as self-stigma. A systematic review found that exposure to public stigma predicts self-stigma at a later time [ 11 , 12 ]. A person’s own stigmatizing views towards mental illness is associated with lower readiness to appraise his or her own symptoms as potentially indicating a mental health problem and thus reduces help-seeking behaviour [ 13 ]. This could be because the individual seeks to avoid the label of mental illness for him- or herself [ 14 ], fathomably to guard themselves against the negative self-perceptions associated with it and the potential consequences of shame and reduced empowerment [ 15 ]. Indeed, self-stigma decreases one’s self-esteem and self-efficacy, leading to the “why try effect”, where people with mental health conditions question their worthiness and capability to pursue personal goals [ 16 , 17 ], leading to a loss of self-respect and increased shame and hopelessness [ 18 , 19 ]. Over time, higher levels of self-stigma have been found to be associated with suicidal ideation [ 18 , 20 ].

Due to these adverse effects of stigma, stigma-reduction is seen as a global public health priority [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Anti-stigma programmes were traditionally conducted by or in substantial consultation with groups representing psychiatric expertise [ 25 ]. However, several criticisms have been raised towards this approach in the recent years. First, the emphasis on medical understandings of mental health problems and the importance of adhering to psychiatric interventions have been criticised as fulfilling the psychiatric services agenda rather than the interest of people with mental health conditions and eclipsing inputs from other standpoints [ 3 , 26 ]. Next, mental health professionals have been found to be just as likely to stigmatise those with mental health conditions [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Thus, is has been argued that the professional expertise that mental health professionals have in providing mental health services may be insufficient in impacting the social spheres in which stigma operate, and it may be timely for them to move to a supporting role [ 30 ].

In recent years, anti-stigma programmes have involved people with lived experience to allow direct or parasocial interactions between target audiences and people with mental health conditions. Contact-based interventions have demonstrated the clearest evidence in reducing stigmatising attitudes, desire for social distancing and discrimination [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Contact-based interventions typically involve brief contact between members of a majority group and a stranger representing the stigmatized population who is quite different from a naturally occurring contact. Stigma is reduced by providing an opportunity for interpersonal contact between people who have mental illness and individuals who may hold stigma towards them. A key ingredient of contact-based interventions is the delivery of testimonies by service users [ 34 ]. The efficacy of contact-based education has led to calls for collaborations with individuals with mental health conditions to offer their experiential wisdom in challenging stigma, representing the voice of those who struggle with mental health difficulties and shedding light on blind spots and gaps in previous strategies [ 3 , 35 ]. Corrigan asserted that just as disability rights groups have adopted the slogan of “no policy or action should be taken about a group without full participation of that group”, the same should be applied to alleviate mental health stigma [ 30 ]. Additionally, while we have thus far described the negative processes that arise from stigma, there are people with mental health conditions who do not agree with the hackneyed stereotypes and respond with indignation that seems to empower and energise them to advocate for changes to the ways in which they are treated [ 2 ]. Their inputs towards initiatives that are aimed at improving service delivery and de-stigmatisation programmes have been found to lead to novel results and have been described as a strength of those programmes [ 35 , 36 ].

Singapore is a small, highly urbanised, multi-cultural country located at the Southern tip of the Malayan Peninsula. The resident population is made up of 75.9% Chinese, 15.0% Malay, 7.5% Indian, and 1.6% other ethnicities [ 37 ]. A developed country, the culture of Singapore can be described as a combination of Eastern and Western cultures, and English is the primary language of instruction. Stigma towards mental illness remains prevalent in Singapore today. An earlier nationwide survey revealed that 38.3% of the population believed that people with mental illness are dangerous, and 49.6% felt that people need to be protected from psychiatric patients [ 38 ]. A decade later, another population survey, which used a vignette-based approach, reported that 50.8% of respondents indicated that mental illness was a sign of personal weakness, 42.8% were unwilling to work closely with a person with mental health conditions on a job, and 70.2% were unwilling to have a person with mental health conditions marry into their family [ 39 ]. A recent qualitative study of daily encounters of personal stigma reported themes such as social exclusion, subjection to contemptuous treatment, and rejection by employers following the declaration of a mental health condition [ 40 ].

Anti-stigma activities in Singapore have been conducted by the state psychiatric institution, the Institute of Mental Health (IMH), the National Council of Social Service, the Health Promotion Board (statutory boards), and non-profit organisations such as the Singapore Association for Mental Health and Silver Ribbon Singapore, who have the collective aims of improving mental health literacy, access to mental health care, and improving the reintegration of people with mental health conditions into the community [ 41 , 42 ]. However, the involvement of individuals with mental health conditions in anti-stigma campaigns is lacking. The purpose of this paper was thus to elicit views and suggestions from people with lived experience (PWLE) and informal caregivers of people with mental health conditions on effective strategies to combat stigma.

The present study is part of a larger study that aimed to examine the nature of mental illness stigma in Singapore from the perspectives of five stakeholder groups, namely PWLE, informal caregivers, members of the general public, professionals working in mental health settings, and policy makers. The main purpose of this research was to provide actionable knowledge. It took a pragmatic approach common in health services research and did not assume any particular methodological orientation [ 43 ]. Only data from PWLE and caregivers were used in this analysis. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before initiating study related procedures.

2.1. Participants

PWLE and caregivers were recruited through referrals by their clinicians or self-referral by learning about the study though poster advertisements placed in waiting areas at the IMH outpatient clinics. The IMH is Singapore’s largest provider of mental health care, providing pharmacological and psychosocial treatments as well as psychosocial rehabilitation for a range of subspecialties, including child and adolescent psychiatry, affective disorders, and psychosis. It has also spearheaded mental health education and anti-stigma events for the public. All the participants were required to be Singapore citizens and permanent residents, aged 21 years old and above, and could not be a student or professional from the mental health field.

PWLE recruitment was limited to two types of psychiatric diagnoses, mood and psychotic disorders, to attain a more homogenous account of encounters with stigma. The groups were also separated by diagnosis to facilitate the identification of members in a group with each other and to provide comfort when expressing themselves. In all, six Focus Group Discussions (FGD) were conducted with PWLE between March to May 2018 (three with individuals with mood disorders, three with those with psychosis-related disorders). Referred and self-referred PWLE were deemed clinically stable by their treating clinicians and were able to provide informed consent.

Although the poster advertisements indicated that the study sought caregivers of individuals with psychosis-related or mood disorders, no attempt was made to confirm the diagnosis of their care recipients with the treating clinicians. The caregiver group was independent of the PWLE group. Unlike the PWLE FGDs, the caregivers were not separated based on the diagnosis of their care recipient. As the initial FGDs did not identify any issue with this approach, the team carried out the rest of the FGDs in a similar manner. In all, five FGDs were conducted with caregivers between June and November 2018.

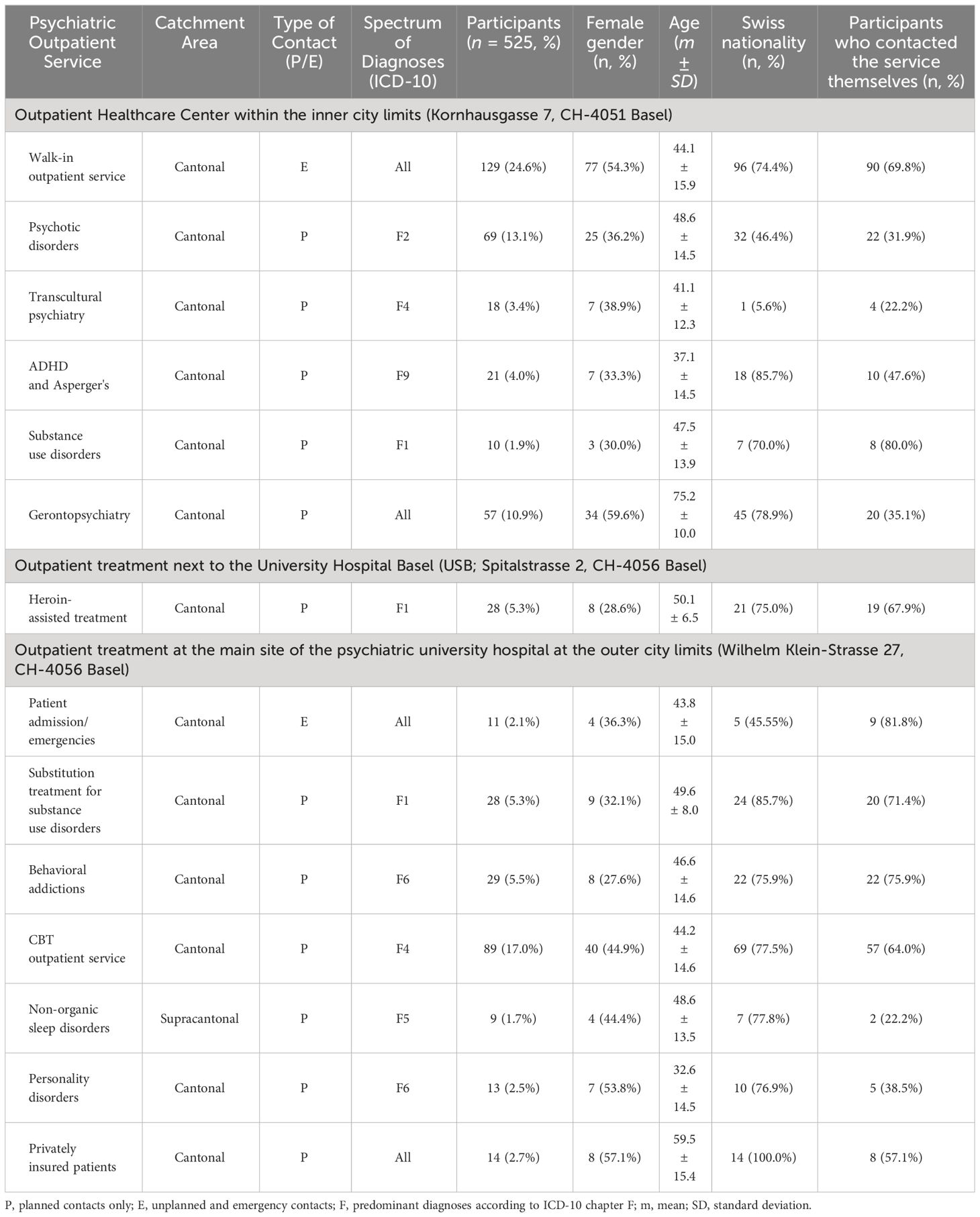

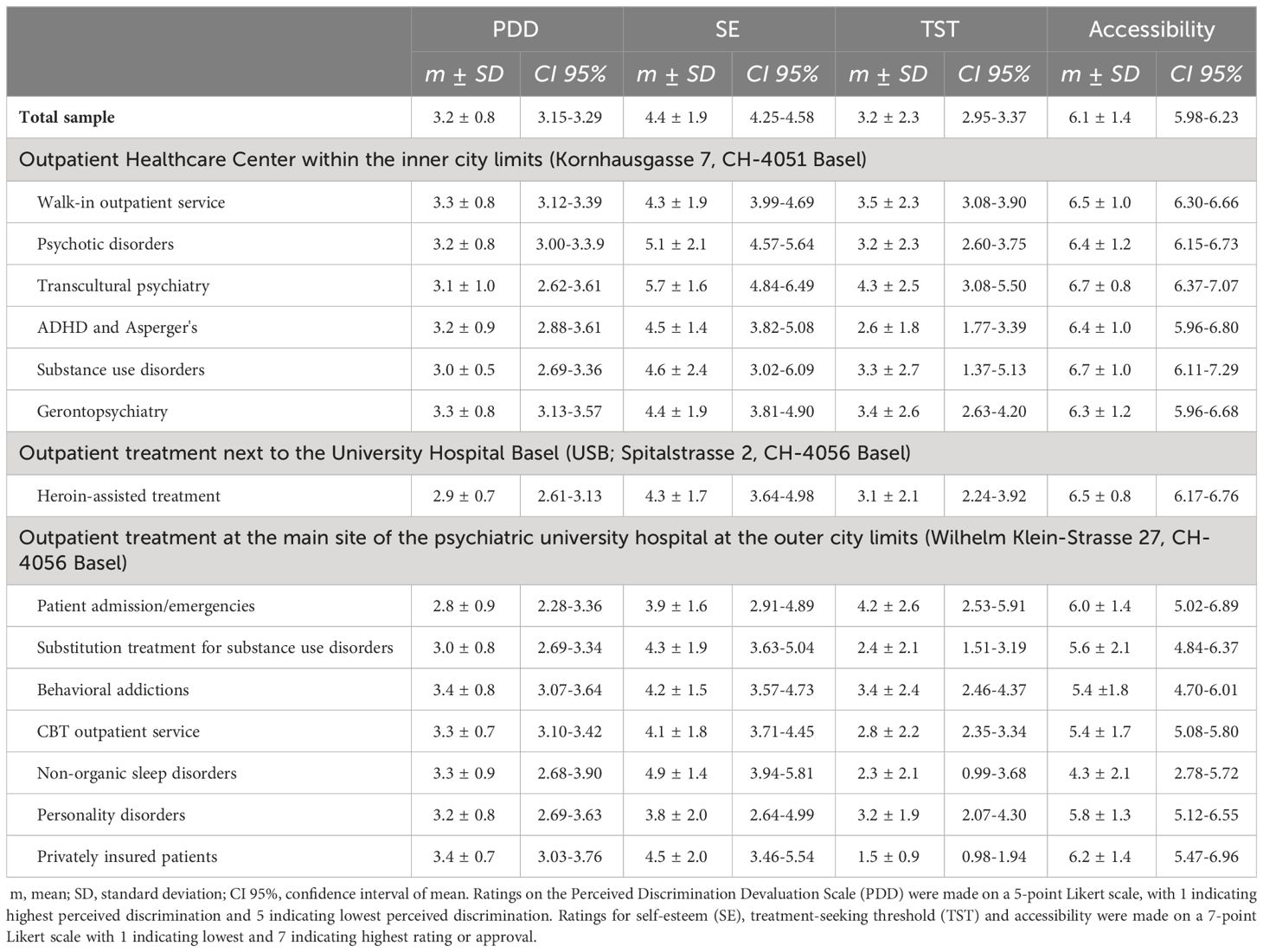

The PWLE FGDs ranged from 5–8 participants, while the caregiver FGDs ranged from 4–9 participants. The sociodemographic profiles of the PWLE and caregiver participants are presented in Table 1 . Participants received an inconvenience fee at the end of the FGD. All FGDs were conducted in English.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

# 1 missing PWLE response for Highest Completed Education.

2.2. Data Collection

The FGDs were conducted in a closed room that was relatively free from distractions in a community club, which was chosen because it is a neutral venue. Each FGD was conducted by two study team members, who served as the facilitator or the note taker for the day. The facilitators (either MS or SS) were trained and experienced in qualitative research methodologies. CMJG, OWJ, GTTH, SS, and MS took turns as note-takers in the different FGDs.

After individual consent was taken to participate in the research and to audio-record the session, each participant filled out a sociodemographic form that collated information about age, gender, education level, ethnicity, and brief information about their illness (for PWLE) or caregiving relationship (for caregivers), and the completed form was returned to the facilitator. Participants were assured that all of the data collected from them would be kept confidential, the transcripts would be de-identified such that names and other identifying features would be omitted, the audio-recording would be deleted after transcription, and that there were no correct or incorrect answers before the discussion commenced.

The experienced facilitators used a topic guide comprising open-ended questions that had been developed by the research team so that the data collected across the various FGDs would be as uniform as possible. Few specific questions were designed to elicit information that could be best addressed by a particular target group. The topic guide covered areas of mental illness stigma such as encounters of stigma and reasons for stigma. The team formulated the questions in a manner similar to that recommended by Krueger et al. [ 44 ], the recommendations of whom comprised the following: The questions should elicit information that directly relates to the study’s objectives. The questions should be easy for the participants to understand and should be phrased in a neutral manner so as not to bias participant responses. The questions can be answered by all the participants. Questions should be open-ended and not answered with a “yes” or “no” to facilitate descriptive responses. The questions should not make the participants uncomfortable when answering, and they should not trigger defensive responses. The team brainstormed the questions to answer the objectives of the research, and one researcher drafted the questioning route, rephrased, and reordered the questions to form a logical flow. The draft was circulated to the rest of the team, and suggestions were incorporated. The team aimed to keep the final total number of questions between 10–12. Decisions to omit questions were based on importance in addressing the research objectives, with final decisions being made by the lead investigator (MS). The questions were then tested out, using the first focus group as a pilot. The items that were used to elicit responses to the research question addressed in this paper was from the final segment of the topic guide: “How do you think stigma towards people with mental illness can be reduced” and “Have you heard of campaigns to reduce stigma towards those with mental illness? Is there anything that can be done better?”. The facilitator probed for range and depth of responses and sought clarification for responses that were unclear using neutral questions. Attempts were made to encourage responses from all members. The entire duration of each FGD lasted between 1.5–2 h. FGDS were carried out one at a time, first with the PWLE and then with the caregivers. At the end of each FGD, there was a debrief between the facilitator and note-taker, and a comprehensive summary was provided to the rest of the research team soon after to reflect on each session, to ensure that any problems were identified early and addressed, and emerging themes and unique points that had been raised were discussed. The FGDs were later transcribed verbatim for analysis. The decision was made by the team to cease data collection for PWLE and the caregiver groups when no new themes were identified, i.e., when data saturation was reached.

2.3. Analysis

The data were analysed using an inductive thematic analysis method [ 45 ]. Transcripts were first distributed amongst five study team members (SS, CMJG, GTTH, OWJ, and MS) for familiarisation with the collected data. Subsequently, each study team member independently identified preliminary codes from their respective transcripts. The study team members then came together, and through an iterative process of comparing the codes and combining, discarding, and redefining the codes, collaboratively decided on the final list of codes. A codebook was developed by the coders (SS, CMJG, GTTH, OWJ, and MS), in which each code was characterised by a description, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and typical and atypical exemplars to guide the coding process. To ensure coding consistency among the study team members, one transcript was first coded to establish inter-rater reliability. The study team continued to discuss, refine the codebook, and repeat the coding with another transcript until a satisfactory inter-rater reliability score was achieved (Cohen’s Kappa score > 0.75). Transcripts were then distributed among the study team members for coding. Data analysis was completed with Nvivo Version 11.0. (QSR International Pty Ltd. Hawthorn East, Australia).

After coding all transcripts, the codes were sorted such that similar codes were grouped together to form potential themes. Codes that did not seem to fit into any theme at first were revisited as the themes were gradually refined. Relationships between these themes were also examined, and different levels (main theme and sub-themes) were identified. Any remaining codes were compared against the revised themes to determine fit. The initial themes were drafted by SS, JCMG, GTTH, OWJ, and MS and presented to CSA for further refinement before finalisation.

Strategies to ensure the quality of the findings recommended by Anney [ 46 ] were exercised in this research. Data were triangulated from two different informant sources: patients and caregivers. The transcripts were read and re-read by five researchers independently. The interpretations were compared, and regular meetings were held to discuss differences until a consensus was reached. These informant and researcher triangulations aimed to increase the credibility of the findings. To ensure transferability, the participants were sampled in such a way that there was good distribution by age, gender, education level, and ethnicity, and for the caregivers, relationship with the care-recipient. Finally, for confirmability, intentional record keeping of summaries and reflections after each FGD as well as decisions made during the coding and analysis were documented to maintain an audit trail.

Four overarching themes depicting the strategies to combat stigma were identified. They included (1) raising mental health awareness, (2) social contact, (3) advocacy by influential figures or groups, and (4) legislation of anti-discriminatory laws. It was not uncommon for participants to refer to two or more approaches in a single quote. While we have selected quotes to illustrate the main theme, they may cross-cover other themes to some degree. To ensure that standard usage of English was maintained, minimally corrected verbatim of quotes are presented.

3.1. Raising Mental Health Awareness

There were two subthemes pertaining to the strategy of raising mental health awareness, which can be described as the “who and how” and “what” of this approach.

3.1.1. Target Groups/Setting and Methods

Anti-stigma awareness initiatives for the general population were frequently suggested by participants, and they recommended outreach through both traditional and social media as well as popular mass events such as marathons and festivals in order to reach a wide range of members of the public from the young to the old. They also emphasised that these efforts should be carried out repeatedly, reasoning that increased exposure to the topic will lead to greater familiarity and with time, greater acceptance of this taboo subject.

You all have to do a lot of campaigns, running it tends to stick in their minds (Male, 37 years, Psychosis-related disorder, PWLE FGD 5)

Educating the public because it is very important. More on media because there are many people on the internet or computer, TV and all sorts ah, newspaper of course, articles, so that more people will come to know so that lesser, I mean to accept slowly. The stigma will grow weaker and weaker, not that strong. (Female, 65 years, Caregiver FGD 3)