An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Heart-Healthy Living

- High Blood Pressure

- Sickle Cell Disease

- Sleep Apnea

- Information & Resources on COVID-19

- The Heart Truth®

- Learn More Breathe Better®

- Blood Diseases and Disorders Education Program

- Publications and Resources

- Blood Disorders and Blood Safety

- Sleep Science and Sleep Disorders

- Lung Diseases

- Health Disparities and Inequities

- Heart and Vascular Diseases

- Precision Medicine Activities

- Obesity, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

- Population and Epidemiology Studies

- Women’s Health

- Research Topics

- Clinical Trials

- All Science A-Z

- Grants and Training Home

- Policies and Guidelines

- Funding Opportunities and Contacts

- Training and Career Development

- Email Alerts

- NHLBI in the Press

- Research Features

- Past Events

- Upcoming Events

- Mission and Strategic Vision

- Divisions, Offices and Centers

- Advisory Committees

- Budget and Legislative Information

- Jobs and Working at the NHLBI

- Contact and FAQs

- NIH Sleep Research Plan

- < Back To Research Topics

Obesity Research

Language switcher.

Over the years, NHLBI-supported research on overweight and obesity has led to the development of evidence-based prevention and treatment guidelines for healthcare providers. NHLBI research has also led to guidance on how to choose a behavioral weight loss program.

Studies show that the skills learned and support offered by these programs can help most people make the necessary lifestyle changes for weight loss and reduce their risk of serious health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes.

Our research has also evaluated new community-based programs for various demographics, addressing the health disparities in overweight and obesity.

NHLBI research that really made a difference

- In 1991, the NHLBI developed an Obesity Education Initiative to educate the public and health professionals about obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and its relationship to other risk factors, such as high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol. The initiative led to the development of clinical guidelines for treating overweight and obesity.

- The NHLBI and other NIH Institutes funded the Obesity-Related Behavioral Intervention Trials (ORBIT) projects , which led to the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments to prevent or manage chronic diseases. These studies included families and a variety of demographic groups. A key finding from one study focuses on the importance of targeting psychological factors in obesity treatment.

Current research funded by the NHLBI

The Division of Cardiovascular Sciences , which includes the Clinical Applications and Prevention Branch, funds research to understand how obesity relates to heart disease. The Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science supports the translation and implementation of research, including obesity research, into clinical practice. The Division of Lung Diseases and its National Center on Sleep Disorders Research fund research on the impact of obesity on sleep-disordered breathing.

Find funding opportunities and program contacts for research related to obesity and its complications.

Current research on obesity and health disparities

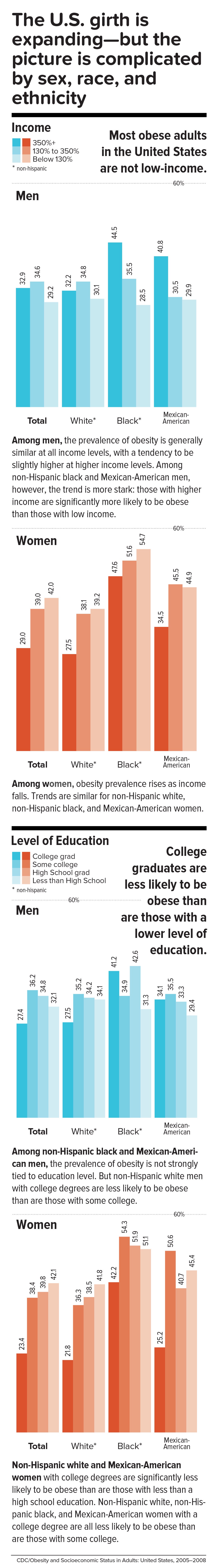

Health disparities happen when members of a group experience negative impacts on their health because of where they live, their racial or ethnic background, how much money they make, or how much education they received. NHLBI-supported research aims to discover the factors that contribute to health disparities and test ways to eliminate them.

- NHLBI-funded researchers behind the RURAL: Risk Underlying Rural Areas Longitudinal Cohort Study want to discover why people in poor rural communities in the South have shorter, unhealthier lives on average. The study includes 4,000 diverse participants (ages 35–64 years, 50% women, 44% whites, 45% Blacks, 10% Hispanic) from 10 of the poorest rural counties in Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Their results will support future interventions and disease prevention efforts.

- The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) is looking at what factors contribute to the higher-than-expected numbers of Hispanics/Latinos who suffer from metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes. The study includes more than 16,000 Hispanic/Latino adults across the nation.

Find more NHLBI-funded studies on obesity and health disparities at NIH RePORTER.

Read how African Americans are learning to transform soul food into healthy, delicious meals to prevent cardiovascular disease: Vegan soul food: Will it help fight heart disease, obesity?

Current research on obesity in pregnancy and childhood

- The NHLBI-supported Fragile Families Cardiovascular Health Follow-Up Study continues a study that began in 2000 with 5,000 American children born in large cities. The cohort was racially and ethnically diverse, with approximately 40% of the children living in poverty. Researchers collected socioeconomic, demographic, neighborhood, genetic, and developmental data from the participants. In this next phase, researchers will continue to collect similar data from the participants, who are now young adults.

- The NHLBI is supporting national adoption of the Bright Bodies program through Dissemination and Implementation of the Bright Bodies Intervention for Childhood Obesity . Bright Bodies is a high-intensity, family-based intervention for childhood obesity. In 2017, a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found that Bright Bodies lowered children’s body mass index (BMI) more than other interventions did.

- The NHLBI supports the continuation of the nuMoM2b Heart Health Study , which has followed a diverse cohort of 4,475 women during their first pregnancy. The women provided data and specimens for up to 7 years after the birth of their children. Researchers are now conducting a follow-up study on the relationship between problems during pregnancy and future cardiovascular disease. Women who are pregnant and have obesity are at greater risk than other pregnant women for health problems that can affect mother and baby during pregnancy, at birth, and later in life.

Find more NHLBI-funded studies on obesity in pregnancy and childhood at NIH RePORTER.

Learn about the largest public health nonprofit for Black and African American women and girls in the United States: Empowering Women to Get Healthy, One Step at a Time .

Current research on obesity and sleep

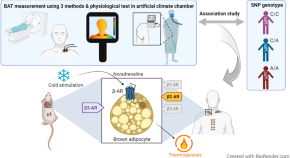

- An NHLBI-funded study is looking at whether energy balance and obesity affect sleep in the same way that a lack of good-quality sleep affects obesity. The researchers are recruiting equal numbers of men and women to include sex differences in their study of how obesity affects sleep quality and circadian rhythms.

- NHLBI-funded researchers are studying metabolism and obstructive sleep apnea . Many people with obesity have sleep apnea. The researchers will look at the measurable metabolic changes in participants from a previous study. These participants were randomized to one of three treatments for sleep apnea: weight loss alone, positive airway pressure (PAP) alone, or combined weight loss and PAP. Researchers hope that the results of the study will allow a more personalized approach to diagnosing and treating sleep apnea.

- The NHLBI-funded Lipidomics Biomarkers Link Sleep Restriction to Adiposity Phenotype, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Risk study explores the relationship between disrupted sleep patterns and diabetes. It uses data from the long-running Multiethnic Cohort Study, which has recruited more than 210,000 participants from five ethnic groups. Researchers are searching for a cellular-level change that can be measured and can predict the onset of diabetes in people who are chronically sleep deprived. Obesity is a common symptom that people with sleep issues have during the onset of diabetes.

Find more NHLBI-funded studies on obesity and sleep at NIH RePORTER.

Learn about a recent study that supports the need for healthy sleep habits from birth: Study finds link between sleep habits and weight gain in newborns .

Obesity research labs at the NHLBI

The Cardiovascular Branch and its Laboratory of Inflammation and Cardiometabolic Diseases conducts studies to understand the links between inflammation, atherosclerosis, and metabolic diseases.

NHLBI’s Division of Intramural Research , including its Laboratory of Obesity and Aging Research , seeks to understand how obesity induces metabolic disorders. The lab studies the “obesity-aging” paradox: how the average American gains more weight as they get older, even when food intake decreases.

Related obesity programs and guidelines

- Aim for a Healthy Weight is a self-guided weight-loss program led by the NHLBI that is based on the psychology of change. It includes tested strategies for eating right and moving more.

- The NHLBI developed the We Can! ® (Ways to Enhance Children’s Activity & Nutrition) program to help support parents in developing healthy habits for their children.

- The Accumulating Data to Optimally Predict obesity Treatment (ADOPT) Core Measures Project standardizes data collected from the various studies of obesity treatments so the data can be analyzed together. The bigger the dataset, the more confidence can be placed in the conclusions. The main goal of this project is to understand the individual differences between people who experience the same treatment.

- The NHLBI Director co-chairs the NIH Nutrition Research Task Force, which guided the development of the first NIH-wide strategic plan for nutrition research being conducted over the next 10 years. See the 2020–2030 Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research .

- The NHLBI is an active member of the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity (NCCOR) , which is a public–private partnership to accelerate progress in reducing childhood obesity.

- The NHLBI has been providing guidance to physicians on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of obesity since 1977. In 2017, the NHLBI convened a panel of experts to take on some of the pressing questions facing the obesity research community. See their responses: Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents (PDF, 3.69 MB).

- In 2021, the NHLBI held a Long Non-coding (lnc) RNAs Symposium to discuss research opportunities on lnc RNAs, which appear to play a role in the development of metabolic diseases such as obesity.

- The Muscatine Heart Study began enrolling children in 1970. By 1981, more than 11,000 students from Muscatine, Iowa, had taken surveys twice a year. The study is the longest-running study of cardiovascular risk factors in children in the United States. Today, many of the earliest participants and their children are still involved in the study, which has already shown that early habits affect cardiovascular health later in life.

- The Jackson Heart Study is a unique partnership of the NHLBI, three colleges and universities, and the Jackson, Miss., community. Its mission is to discover what factors contribute to the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease among African Americans. Researchers aim to test new approaches for reducing this health disparity. The study incudes more than 5,000 individuals. Among the study’s findings to date is a gene variant in African Americans that doubles the risk of heart disease.

Explore more NHLBI research on overweight and obesity

The sections above provide you with the highlights of NHLBI-supported research on overweight and obesity . You can explore the full list of NHLBI-funded studies on the NIH RePORTER .

To find more studies:

- Type your search words into the Quick Search box and press enter.

- Check Active Projects if you want current research.

- Select the Agencies arrow, then the NIH arrow, then check NHLBI .

If you want to sort the projects by budget size — from the biggest to the smallest — click on the FY Total Cost by IC column heading.

A systematic literature review on obesity: Understanding the causes & consequences of obesity and reviewing various machine learning approaches used to predict obesity

Affiliations.

- 1 Centre for Software Technology and Management, Faculty of Information Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Bangi, 43600, Selangor, Malaysia.

- 2 Centre for Software Technology and Management, Faculty of Information Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Bangi, 43600, Selangor, Malaysia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 RIADI Laboratory, University of Manouba, Manouba, Tunisia; College of Computer Science and Engineering, Taibah University, Medina, Saudi Arabia.

- 4 Center for Artificial Intelligence Technology, Faculty of Information Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Bangi, 43600, Selangor, Malaysia.

- PMID: 34426171

- DOI: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104754

Obesity is considered a principal public health concern and ranked as the fifth foremost reason for death globally. Overweight and obesity are one of the main lifestyle illnesses that leads to further health concerns and contributes to numerous chronic diseases, including cancers, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases. The World Health Organization also predicted that 30% of death in the world will be initiated with lifestyle diseases in 2030 and can be stopped through the suitable identification and addressing of associated risk factors and behavioral involvement policies. Thus, detecting and diagnosing obesity as early as possible is crucial. Therefore, the machine learning approach is a promising solution to early predictions of obesity and the risk of overweight because it can offer quick, immediate, and accurate identification of risk factors and condition likelihoods. The present study conducted a systematic literature review to examine obesity research and machine learning techniques for the prevention and treatment of obesity from 2010 to 2020. Accordingly, 93 papers are identified from the review articles as primary studies from an initial pool of over 700 papers addressing obesity. Consequently, this study initially recognized the significant potential factors that influence and cause adult obesity. Next, the main diseases and health consequences of obesity and overweight are investigated. Ultimately, this study recognized the machine learning methods that can be used for the prediction of obesity. Finally, this study seeks to support decision-makers looking to understand the impact of obesity on health in the general population and identify outcomes that can be used to guide health authorities and public health to further mitigate threats and effectively guide obese people globally.

Keywords: Diseases; Machine learning; Obesity; Overweight; Risk factors.

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd.. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Systematic Review

- Machine Learning

- Metabolic Syndrome*

- Obesity* / epidemiology

- Risk Factors

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2021

The lived experience of people with obesity: study protocol for a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies

- Emma Farrell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7780-9428 1 ,

- Marta Bustillo 2 ,

- Carel W. le Roux 3 ,

- Joe Nadglowski 4 ,

- Eva Hollmann 1 &

- Deirdre McGillicuddy 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 181 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6077 Accesses

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

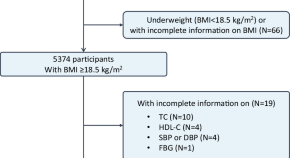

Obesity is a prevalent, complex, progressive and relapsing chronic disease characterised by abnormal or excessive body fat that impairs health and quality of life. It affects more than 650 million adults worldwide and is associated with a range of health complications. Qualitative research plays a key role in understanding patient experiences and the factors that facilitate or hinder the effectiveness of health interventions. This review aims to systematically locate, assess and synthesise qualitative studies in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the lived experience of people with obesity.

This is a protocol for a qualitative evidence synthesis of the lived experience of people with obesity. A defined search strategy will be employed in conducting a comprehensive literature search of the following databases: PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, PsycArticles and Dimensions (from 2011 onwards). Qualitative studies focusing on the lived experience of adults with obesity (BMI >30) will be included. Two reviewers will independently screen all citations, abstracts and full-text articles and abstract data. The quality of included studies will be appraised using the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) criteria. Thematic synthesis will be conducted on all of the included studies. Confidence in the review findings will be assessed using GRADE CERQual.

The findings from this synthesis will be used to inform the EU Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI)-funded SOPHIA (Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy) study. The objective of SOPHIA is to optimise future obesity treatment and stimulate a new narrative, understanding and vocabulary around obesity as a set of complex and chronic diseases. The findings will also be useful to health care providers and policy makers who seek to understand the experience of those with obesity.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42020214560 .

Peer Review reports

Obesity is a complex chronic disease in which abnormal or excess body fat (adiposity) impairs health and quality of life, increases the risk of long-term medical complications and reduces lifespan [ 1 ]. Operationally defined in epidemiological and population studies as a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30, obesity affects more than 650 million adults worldwide [ 2 ]. Its prevalence has almost tripled between 1975 and 2016, and, globally, there are now more people with obesity than people classified as underweight [ 2 ].

Obesity is caused by the complex interplay of multiple genetic, metabolic, behavioural and environmental factors, with the latter thought to be the proximate factor which enabled the substantial rise in the prevalence of obesity in recent decades [ 3 , 4 ]. This increased prevalence has resulted in obesity becoming a major public health issue with a resulting growth in health care and economic costs [ 5 , 6 ]. At a population level, health complications from excess body fat increase as BMI increases [ 7 ]. At the individual level, health complications occur due to a variety of factors such as distribution of adiposity, environment, genetic, biologic and socioeconomic factors [ 8 ]. These health complications include type 2 diabetes [ 9 ], gallbladder disease [ 10 ] and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [ 11 ]. Excess body fat can also place an individual at increased cardiometabolic and cancer risk [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] with an estimated 20% of all cancers attributed to obesity [ 15 ].

Although first recognised as a disease by the American Medical Association in 2013 [ 16 ], the dominant cultural narrative continues to present obesity as a failure of willpower. People with obesity are positioned as personally responsible for their weight. This, combined with the moralisation of health behaviours and the widespread association between thinness, self-control and success, has resulted in those who fail to live up to this cultural ideal being subject to weight bias, stigma and discrimination [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Weight bias, stigma and discrimination have been found to contribute, independent of weight or BMI, to increased morbidity or mortality [ 20 ].

Thomas et al. [ 21 ] highlighted, more than a decade ago, the need to rethink how we approach obesity so as not to perpetuate damaging stereotypes at a societal level. Obesity research then, as now, largely focused on measurable outcomes and quantifiable terms such as body mass index [ 22 , 23 ]. Qualitative research approaches play a key role in understanding patient experiences, how factors facilitate or hinder the effectiveness of interventions and how the processes of interventions are perceived and implemented by users [ 24 ]. Studies adopting qualitative approaches have been shown to deliver a greater depth of understanding of complex and socially mediated diseases such as obesity [ 25 ]. In spite of an increasing recognition of the integral role of patient experience in health research [ 25 , 26 ], the voices of patients remain largely underrepresented in obesity research [ 27 , 28 ].

Systematic reviews and syntheses of qualitative studies are recognised as a useful contribution to evidence and policy development [ 29 ]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this will be the first systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies focusing on the lived experience of people with obesity. While systematic reviews have been carried out on patient experiences of treatments such as behavioural management [ 30 ] and bariatric surgery [ 31 ], this review and synthesis will be the first to focus on the experience of living with obesity rather than patient experiences of particular treatments or interventions. This focus represents a growing awareness that ‘patients have a specific expertise and knowledge derived from lived experience’ and that understanding lived experience can help ‘make healthcare both effective and more efficient’ [ 32 ].

This paper outlines a protocol for the systematic review of qualitative studies based on the lived experience of people with obesity. The findings of this review will be synthesised in order to develop an overview of the lived experience of patients with obesity. It will look, in particular, at patient concerns around the risks of obesity and their aspirations for response to obesity treatment.

The review protocol has been registered within the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42020214560) and is being reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [ 33 , 34 ] (see checklist in Additional file 1 ).

Information sources and search strategy

The primary source of literature will be a structured search of the following electronic databases (from January 2011 onwards—to encompass the increase in research focused on patient experience observed over the last 10 years): PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, PsycArticles and Dimensions. There is no methodological agreement as to how many search terms or databases out to be searched as part of a ‘good’ qualitative synthesis (Toye et al. [ 35 ]). However, the breadth and depth of the search terms, the inclusion of clinical and personal language and the variety within the selected databases, which cover areas such as medicine, nursing, psychology and sociology, will position this qualitative synthesis as comprehensive. Grey literature will not be included in this study as its purpose is to conduct a comprehensive review of peer-reviewed primary research. The study’s patient advisory board will be consulted at each stage of the review process, and content experts and authors who are prolific in the field will be contacted. The literature searches will be designed and conducted by the review team which includes an experienced university librarian (MB) following the methodological guidance of chapter two of the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [ 36 ]. The search will include a broad range of terms and keywords related to obesity and qualitative research. A full draft search strategy for PubMed is provided in Additional file 2 .

Eligibility criteria

Studies based on primary data generated with adults with obesity (operationally defined as BMI >30) and focusing on their lived experience will be eligible for inclusion in this synthesis (Table 1 ). The context can include any country and all three levels of care provision (primary, secondary and tertiary). Only peer-reviewed, English language, articles will be included. Studies adopting a qualitative design, such as phenomenology, grounded theory or ethnography, and employing qualitative methods of data collection and analysis, such as interviews, focus groups, life histories and thematic analysis, will be included. Publications with a specific focus, for example, patient’s experience of bariatric surgery, will be included, as well as studies adopting a more general view of the experience of obesity.

Screening and study selection process

Search results will be imported to Endnote X9, and duplicate entries will be removed. Covidence [ 38 ] will be used to screen references with two reviewers (EF and EH) removing entries that are clearly unrelated to the research question. Titles and abstracts will then be independently screened by two reviewers (EF and EH) according to the inclusion criteria (Table 1 ). Any disagreements will be resolved through a third reviewer (DMcG). This layer of screening will determine which publications will be eligible for independent full-text review by two reviewers (EF and EH) with disagreements again being resolved by a third reviewer (DMcG).

Data extraction

Data will be extracted independently by two researchers (EF and EH) and combined in table format using the following headings: author, year, title, country, research aims, participant characteristics, method of data collection, method of data analysis, author conclusions and qualitative themes. In the case of insufficient or unclear information in a potentially eligible article, the authors will be contacted by email to obtain or confirm data, and a timeframe of 3 weeks to reply will be offered before article exclusion.

Quality appraisal of included studies

This qualitative synthesis will facilitate the development of a conceptual understanding of obesity and will be used to inform the development of policy and practice. As such, it is important that the studies included are themselves of suitable quality. The methodological quality of all included studies will be assessed using the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) checklist, and studies that are deemed of insufficient quality will be excluded. The CASP checklist for qualitative research comprises ten questions that cover three main issues: Are the results of the study under review valid? What are the results? Will the results help locally? Two reviewers (EF and EH) will independently evaluate each study using the checklist with a third and fourth reviewer (DMcG and MB) available for consultation in the event of disagreement.

Data synthesis

The data generated through the systematic review outlined above will be synthesised using thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden [ 39 ]. Thematic synthesis enables researchers to stay ‘close’ to the data of primary studies, synthesise them in a transparent way and produce new concepts and hypotheses. This inductive approach is useful for drawing inference based on common themes from studies with different designs and perspectives. Thematic synthesis is made up of a three-step process. Step one consists of line by line coding of the findings of primary studies. The second step involves organising these ‘free codes’ into related areas to construct ‘descriptive’ themes. In step three, the descriptive themes that emerged will be iteratively examined and compared to ‘go beyond’ the descriptive themes and the content of the initial studies. This step will generate analytical themes that will provide new insights related to the topic under review.

Data will be coded using NVivo 12. In order to increase the confirmability of the analysis, studies will be reviewed independently by two reviewers (EF and EH) following the three-step process outlined above. This process will be overseen by a third reviewer (DMcG). In order to increase the credibility of the findings, an overview of the results will be brought to a panel of patient representatives for discussion. Direct quotations from participants in the primary studies will be italicised and indented to distinguish them from author interpretations.

Assessment of confidence in the review findings

Confidence in the evidence generated as a result of this qualitative synthesis will be assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE CERQual) [ 40 ] approach. Four components contribute to the assessment of confidence in the evidence: methodological limitations, relevance, coherence and adequacy of data. The methodological limitations of included studies will be examined using the CASP tool. Relevance assesses the degree to which the evidence from the primary studies applies to the synthesis question while coherence assesses how well the findings are supported by the primary studies. Adequacy of data assesses how much data supports a finding and how rich this data is. Confidence in the evidence will be independently assessed by two reviewers (EF and EH), graded as high, moderate or low, and discussed collectively amongst the research team.

Reflexivity

For the purposes of transparency and reflexivity, it will be important to consider the findings of the qualitative synthesis and how these are reached, in the context of researchers’ worldviews and experiences (Larkin et al, 2019). Authors have backgrounds in health science (EF and EH), education (DMcG and EF), nursing (EH), sociology (DMcG), philosophy (EF) and information science (MB). Prior to conducting the qualitative synthesis, the authors will examine and discuss their preconceptions and beliefs surrounding the subject under study and consider the relevance of these preconceptions during each stage of analysis.

Dissemination of findings

Findings from the qualitative synthesis will be disseminated through publications in peer-reviewed journals, a comprehensive and in-depth project report and presentation at peer-reviewed academic conferences (such as EASO) within the field of obesity research. It is also envisaged that the qualitative synthesis will contribute to the shared value analysis to be undertaken with key stakeholders (including patients, clinicians, payers, policy makers, regulators and industry) within the broader study which seeks to create a new narrative around obesity diagnosis and treatment by foregrounding patient experiences and voice(s). This synthesis will be disseminated to the 29 project partners through oral presentations at management board meetings and at the general assembly. It will also be presented as an educational resource for clinicians to contribute to an improved understanding of patient experience of living with obesity.

Obesity is a complex chronic disease which increases the risk of long-term medical complications and a reduced quality of life. It affects a significant proportion of the world’s population and is a major public health concern. Obesity is the result of a complex interplay of multiple factors including genetic, metabolic, behavioural and environmental factors. In spite of this complexity, obesity is often construed in simple terms as a failure of willpower. People with obesity are subject to weight bias, stigma and discrimination which in themselves result in increased risk of mobility or mortality. Research in the area of obesity has tended towards measurable outcomes and quantitative variables that fail to capture the complexity associated with the experience of obesity. A need to rethink how we approach obesity has been identified—one that represents the voices and experiences of people living with obesity. This paper outlines a protocol for the systematic review of available literature on the lived experience of people with obesity and the synthesis of these findings in order to develop an understanding of patient experiences, their concerns regarding the risks associated with obesity and their aspirations for response to obesity treatment. Its main strengths will be the breadth of its search remit—focusing on the experiences of people with obesity rather than their experience of a particular treatment or intervention. It will also involve people living with obesity and its findings disseminated amongst the 29 international partners SOPHIA research consortium, in peer reviewed journals and at academic conferences. Just as the study’s broad remit is its strength, it is also a potential challenge as it is anticipated that searchers will generate many thousands of results owing to the breadth of the search terms. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this will be the first systematic review and synthesis of its kind, and its findings will contribute to shaping the optimisation of future obesity understanding and treatment.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Body mass index

Critical appraisal skills programme

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research

Innovative Medicines Initiative

Medical Subject Headings

Population, phenomenon of interest, context, study type

Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy

Wharton S, Lau DCW, Vallis M, Sharma AM, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(31):E875–91. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.191707 .

Article Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. Fact sheet: obesity and overweight. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2020.

Google Scholar

Mechanick J, Hurley D, Garvey W. Adiposity-based chronic disease as a new diagnostic term: the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College Of Endocrinology position statement. Endocrine Pract. 2017;23(3):372–8. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP161688.PS .

Garvey W, Mechanick J. Proposal for a scientifically correct and medically actionable disease classification system (ICD) for obesity. Obesity. 2020;28(3):484–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22727 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Biener A, Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The high and rising costs of obesity to the US health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(Suppl 1):6–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3968-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Department of Health and Social Care. Healthy lives, healthy people: a call to action on obesity in England. London: Department of Health and Social Care; 2011.

Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju SN, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, de Gonzalez AB, et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388(10046):776–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1 .

Sharma AM. M, M, M & M: a mnemonic for assessing obesity. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11(11):808–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00766.x .

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Asnawi A, Peeters A, de Courten M, Stoelwinder J. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;89:309-19. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:309–19.

Dagfinn A, Teresa N, Lars JV. Body mass index, abdominal fatness and the risk of gallbladder disease. 2015;30(9):1009.

Longo M, Zatterale F, Naderi J, Parrillo L, Formisano P, Raciti GA, et al. Adipose tissue dysfunction as determinant of obesity-associated metabolic complications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9).

Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, Westfall AO, Allison DB. Years of life lost due to obesity. 2003;289(2):187-193.

Grover SA, Kaouache M, Rempel P, Joseph L, Dawes M, Lau DCW, et al. Years of life lost and healthy life-years lost from diabetes and cardiovascular disease in overweight and obese people: a modelling study. 2015;3(2):114-122.

Ackerman S, Blackburn O, Marchildon F, Cohen P. Insights into the link between obesity and cancer. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):195–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0263-x .

Wolin K, Carson K, Colditz G. Obesity and cancer. Oncol. 2010;15(6):556–65. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285 .

Resolution 420: Recognition of obesity as a disease [press release]. 05/16/13 2013.

Brownell KD. Personal responsibility and control over our bodies: when expectation exceeds reality. 1991;10(5):303-10.

Puhl RM, Latner JD, O'Brien K, Luedicke J, Danielsdottir S, Forhan M. A multinational examination of weight bias: predictors of anti-fat attitudes across four countries. 2015;39(7):1166-1173.

Browne NT. Weight bias, stigmatization, and bullying of obese youth. 2012;7(3):107-15.

Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Weight discrimination and risk of mortality. 2015;26(11):1803-11.

Thomas SL, Hyde J, Karunaratne A, Herbert D, Komesaroff PA. Being “fat” in today’s world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in Australia. 2008;11(4):321-30.

Ogden K, Barr J, Rossetto G, Mercer J. A “messy ball of wool”: a qualitative study of the dimensions of the lived experience of obesity. 2020;8(1):1-14.

Ueland V, Furnes B, Dysvik E, R¯rtveit K. Living with obesity-existential experiences. 2019;14(1):1-12.

Avenell A, Robertson C, Skea Z, Jacobsen E, Boyers D, Cooper D, et al. Bariatric surgery, lifestyle interventions and orlistat for severe obesity: the REBALANCE mixed-methods systematic review and economic evaluation. 2018;22(68).

The PLoS Medicine Editors. Qualitative research: understanding patients’ needs and experiences. Plos Med. 2007;4(8):1283–4.

Boulton M, Fitzpatrick R. Qualitative methods for assessing health care doi:10.1136/qshc.3.2.107. Qual Health Care. 1994;3:107–13.

Johnstone J, Herredsberg C, Lacy L, Bayles P, Dierking L, Houck A, et al. What I wish my doctor really knew: the voices of patients with obesity. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(2):169–71. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2494 .

Brown I, Thompson J, Tod A, Jones G. Primary care support for tackling obesity: a qualitative study of the perceptions of obese patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(530):666–72.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brown I, Gould J. Qualitative studies of obesity: a review of methodology. Health. 2013;5(8A3):69–80.

Garip G, Yardley L. A synthesis of qualitative research on overweight and obese people’s views and experiences of weight management. Clin Obes. 2011;1(2-3):10–126.

Coulman K, MacKichan F, Blazeby J, Owen-Smith A. Patient experiences of outcomes of bariatric surgery: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Obes Rev. 2017;18(5):547–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12518 .

European Patients’ Forum. “Patients’ Perceptions of Quality in Healthcare”: Report of a survey conducted by EPF in 2016 Brussels: European Patients’ Forum; 2017.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 .

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349(jan02 1):g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647 .

Toye F, et al. Meta-ethnography 25 years on: challenges and insights for synthesising a large number of qualitative studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(80).

Lockwood C, Porrit K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, et al. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: JBI; 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-03 .

Methley AM, et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of spcificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Res. 2014;14.

Covidence. Cochrane Community; 2020. Available from: https://www.covidence.org .

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 .

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Any amendments made to this protocol when conducting the study will be outlined in PROSPERO and reported in the final manuscript.

This project has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (JU) under grant agreement No 875534. The JU receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA and T1D Exchange, JDRF and Obesity Action Coalition. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and will not have a role in collection, analysis and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

Emma Farrell, Eva Hollmann & Deirdre McGillicuddy

University College Dublin Library, Dublin, Ireland

Marta Bustillo

Diabetes Complications Research Centre, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Carel W. le Roux

Obesity Action Coalition, Tampa, USA

Joe Nadglowski

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

EF conceptualised and designed the protocol with input from DMcG and MB. EF drafted the initial manuscript. EF and MB defined the concepts and search items with input from DmcG, CleR and JN. MB and EF designed and executed the search strategy. DMcG, CleR, JN and EH provided critical insights and reviewed and revised the protocol. All authors have approved and contributed to the final written manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Emma Farrell .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:..

PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) 2015 checklist: recommended items to address in a systematic review protocol*.

Additional file 2: Table 1

. Search PubMed search string.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Farrell, E., Bustillo, M., le Roux, C.W. et al. The lived experience of people with obesity: study protocol for a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Syst Rev 10 , 181 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01706-5

Download citation

Received : 28 October 2020

Accepted : 14 May 2021

Published : 21 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01706-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Lived experience

- Patient experience

- Obesity treatment

- Qualitative

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Prevention, prevention, prevention.

Losing weight is hard to do.

In the U.S., only one in six adults who have dropped excess pounds actually keep off at least 10 percent of their original body weight. The reason: a mismatch between biology and environment. Our bodies are evolutionarily programmed to put on fat to ride out famine and preserve the excess by slowing metabolism and, more important, provoking hunger. People who have slimmed down and then regain their weight don’t lack willpower—their bodies are fighting them every inch of the way.

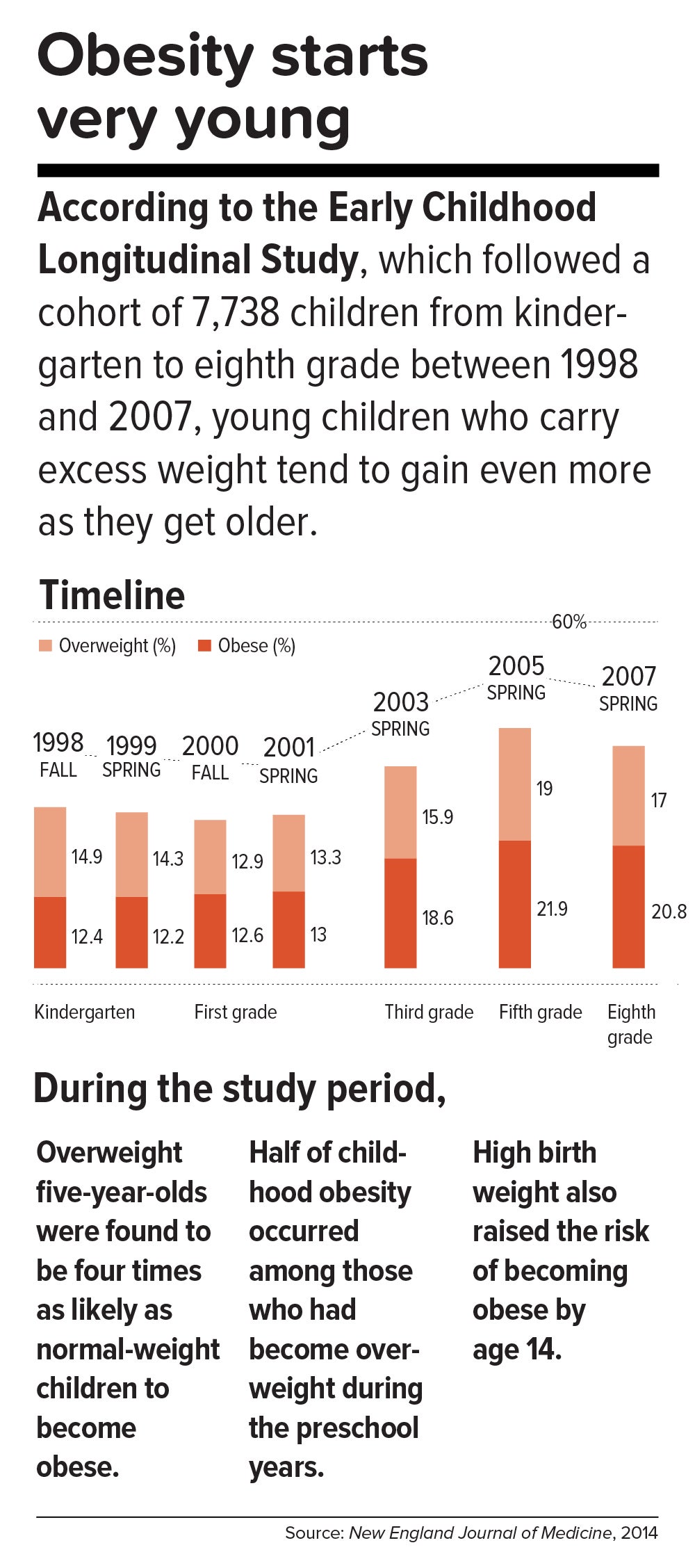

This inborn predisposition to hold on to added weight reverberates down the life course. Few children are born obese, but once they become heavy, they are usually destined to be heavy adolescents and heavy adults. According to a 2016 study in the New England Journal of Medicine , approximately 90 percent of children with severe obesity will become obese adults with a BMI of 35 or higher. Heavy young adults are generally heavy in middle and old age. Obesity also jumps across generations; having a mother who is obese is one of the strongest predictors of obesity in children.

All of which means that preventing child obesity is key to stopping the epidemic. By the time weight piles up in adulthood, it is usually too late. Luckily, preventing obesity in children is easier than in adults, partly because the excess calories they absorb are minimal and can be adjusted by small changes in diet—substituting water, for example, for sugary fruit juices or soda.

Still, the bulk of the obesity problem—literally—is in adults. According to Frank Hu, chair of the Harvard Chan Department of Nutrition, “Most people gain weight during young and middle adulthood. The weight-gain trajectory is less than 1 pound per year, but it creeps up steadily from age 18 to age 55. During this time, people gain fat mass, not muscle mass. When they reach age 55 or so, they begin to lose their existing muscle mass and gain even more fat mass. That’s when all the metabolic problems appear: insulin resistance, high cholesterol, high blood pressure.”

Adds Walter Willett, Frederick John Stare Professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition at Harvard Chan, “The first 5 pounds of weight gain at age 25—that’s the time to be taking action. Because someone is on a trajectory to end up being 30 pounds overweight by the time they’re age 50.”

The most realistic near-term public health goal, therefore, is not to reverse but rather to slow down the trend—and even this will require strong commitment from government at many levels. In May 2017, the Trump administration rolled back recently-enacted standards for school meals, delaying a rule to lower sodium and allowing waivers for regulations requiring cafeterias to serve foods rich in whole grains. If recent expansions in food entitlements and school meals are undermined, “It would be a ‘disaster,’ to use the president’s word,” says Marlene Schwartz, director of the Rudd Center for Obesity & Food Policy at the University of Connecticut. “The federal food programs are incredibly important, not just because of the food and money they provide families, but because supporting better nutrition in child care, schools, and the WIC [Women, Infants, and Children] program has created new social norms. We absolutely cannot undo the progress that we’ve made in helping this generation transition to a healthier diet.”

Get the science right.

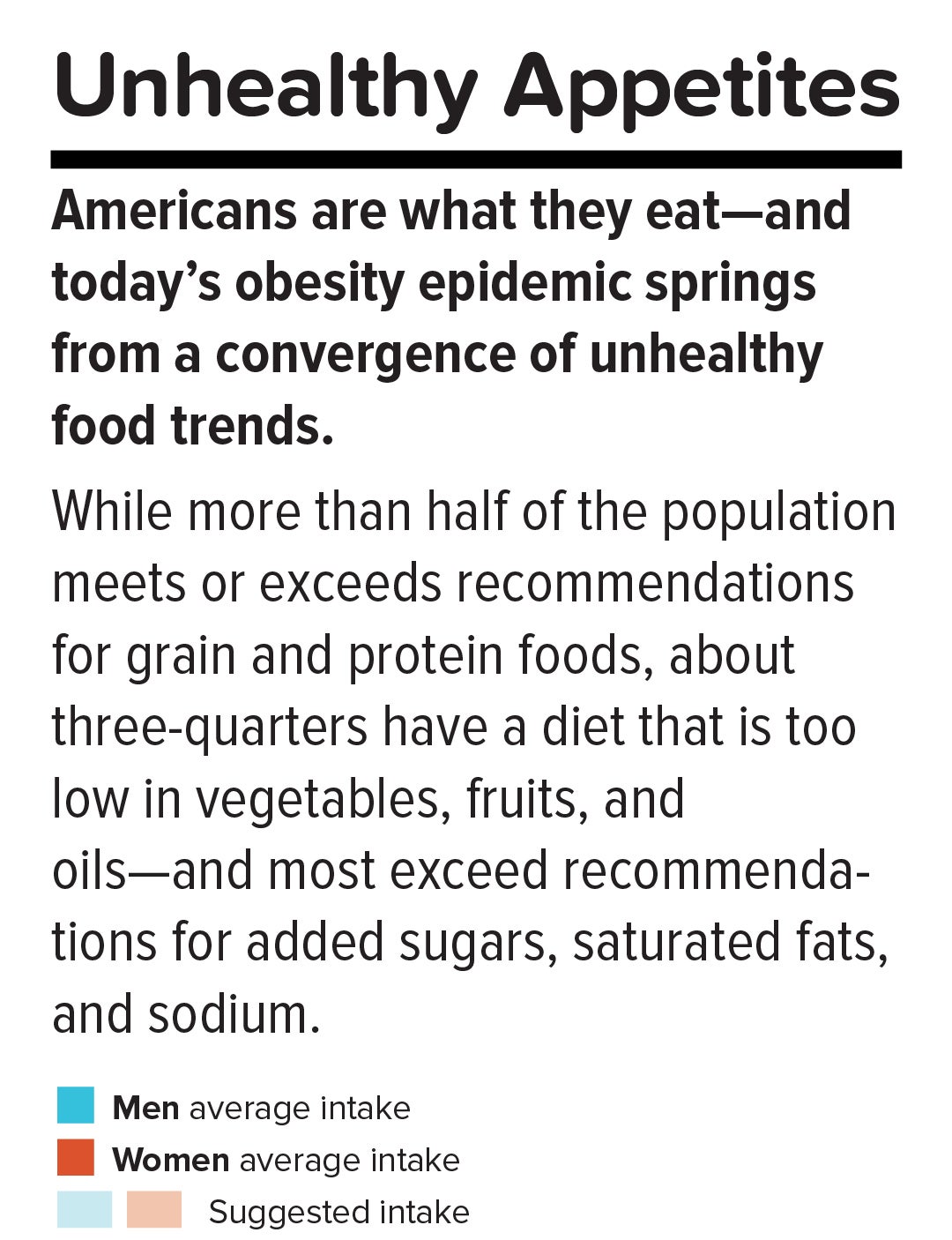

It is impossible to prescribe solutions to obesity without reminding ourselves that nutrition scientists botched things decades ago and probably sent the epidemic into overdrive. Beginning in the 1970s, the U.S. government and major professional groups recommended for the first time that people eat a low-fat/high-carbohydrate diet. The advice was codified in 1977 with the first edition of The Dietary Goals for the United States , which aimed to cut diet-related conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. What ensued amounted to arguably the biggest public health experiment in U.S. history, and it backfired.

At the time, saturated fat and dietary cholesterol were believed to be the main factors responsible for cardiovascular disease—an oversimplified theory that ignored the fact that not all fats are created equal. Soon, the public health blitz against saturated fat became a war on all fat. In the American diet, fat calories plummeted and carb calories shot up.

“We can’t blame industry for this. It was a bandwagon effect in the scientific community, despite the lack of evidence—even with evidence to the contrary,” says Willett. “Farmers have known for thousands of years that if you put animals in a pen, don’t let them run around, and load them up with grains, they get fat. That’s basically what has been happening to people: We created the great American feedlot. And we added in sugar, coloring, and seductive promotion for low-fat junk food.”

Scientists now know that whole fruits and vegetables (other than potatoes), whole grains, high-quality proteins (such as from fish, chicken, beans, and nuts), and healthy plant oils (such as olive, peanut, or canola oil) are the foundations of a healthy diet.

But there is also a lot scientists don’t yet know. One unanswered question is why some people with obesity are spared the medical complications of excess weight. Another concerns the major mechanisms by which obesity ushers in disease. Although surplus body weight can itself directly cause problems—such as arthritis due to added load on joints, or breast cancer caused by hormones secreted by fat cells—in general, obesity triggers myriad biological processes. Many of the resulting conditions—such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, and even Alzheimer’s disease—are mediated by inflammation, in which the body’s immune response becomes damagingly self-perpetuating. In this sense, today’s food system is as inflammagenic as it is obesigenic.

Scientists also need to ferret out the nuanced effects of particular foods. For example, do fermented products—such as yogurt, tempeh, or sauerkraut—have beneficial properties? Some studies have found that yogurt protects against weight gain and diabetes, and suggest that healthy live bacteria (known as probiotics) may play a role. Other reports point to fruits being more protective than vegetables in weight control and diabetes prevention, although the types of fruits and vegetables make a difference.

A 2017 article in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition showed that substituting whole grains for refined grains led to a loss of nearly 100 calories a day—by speeding up metabolism, cutting the number of calories that the body hangs on to, and, more surprisingly, by changing the digestibility of other foods on the plate. That extra energy lost daily—by substituting, say, brown rice for white rice or barley for pita bread—was equivalent to a brisk 30-minute walk. One hundred calories a day, sustained over years, and multiplied by the population is one mathematical equivalent of the obesity epidemic.

A companion study found that adults who ate a whole-grain-rich diet developed healthier gut bacteria and improved immune responses. That particular foods alter the gut microbiome—the dense and vital community of bacteria and other microorganisms that work symbiotically with the body’s own digestive system—is another critical insight. The microbiome helps determine weight by controlling how our bodies extract calories and store fat in the liver, and the microbiomes of obese individuals are startlingly efficient at harvesting calories from food. [To learn more about Harvard Chan research on the gut microbiome, read “ Bugs in the System .”] The hormonal effects of sleep deprivation and stress—two epidemics concurrent and intertwined with the obesity trend—are other promising avenues of research.

And then there are the mystery factors. One recent hypothesis is that an agent known as adenovirus 36 partly accounts for our collective heft. A 2010 article in The Royal Society described a study in which researchers examined samples of more than 20,000 animals from eight species living with or around humans in industrialized nations, a menagerie that included macaques, chimpanzees, vervets, marmosets, lab mice and rats, feral rats, and domestic dogs and cats. Like their Homo sapiens counterparts, all of the study populations had gained weight over the past several decades—wild, domestic, and lab animals alike. The chance that this is a coincidence is, according to the scientists’ estimate, 1 in 10 million. The stumped authors surmise that viruses, gene expression changes, or “as-of-yet unidentified and/or poorly understood factors” are to blame.

Master the art of persuasion.

A 2015 paper in the American Journal of Public Health revealed the philosophical chasm that hampers America’s progress on obesity prevention. It found that 72 to 98 percent of obesity-related media reports emphasize personal responsibility for weight, compared with 40 percent of scientific papers.

A recent study by Drexel University researchers also quantified the political polarization around public health measures. From 1998 through 2013, Democrats voted in line with recommendations from the American Public Health Association 88.3 percent of the time, on average, while Republicans voted for the proposals just 21.3 percent of the time.

Clearly, we can’t count on bipartisan goodwill to stem the obesity crisis. But we can ask what kinds of messages appeal to politically divergent audiences. A stealth strategy may be to avoid even uttering the word “obesity.” On January 1 of this year, Philadelphia’s 1.5-cents-per-ounce excise tax on sugar-sweetened and diet beverages took effect. When Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney lobbied voters to approve the tax, his bid centered not on improving health—the unsuccessful pitch of his predecessor—but on raising $91 million annually for prekindergarten programs.

“That’s something lots of people care about and can get behind—it’s a feel-good policy, and it makes sense,” says psychologist Christina Roberto, assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, and a former assistant professor of social and behavioral sciences and nutrition at Harvard Chan. The provision for taxing diet beverages was also shrewd, she adds, because it spread the tax’s pain; since wealthier people are more likely than less-affluent individuals to buy diet drinks, the tax could not be slapped with the label “regressive.”

But Roberto sees a larger lesson in the Philadelphia story. Public health messaging that appeals to values that transcend the individual is less fraught, less stigmatizing, and perhaps more effective. As she puts it, “It’s very different to hear the message, ‘Eat less red meat, help the planet’ versus ‘Eat less red meat, help yourself avoid saturated fat and cardiovascular disease.’”

Supermarket makeovers

Supermarket aisles are other places where public health can shuffle a deck stacked against healthy consumer choices.

With slim profit margins and 50,000-plus products on their shelves, grocery stores depend heavily on food manufacturers’ promotional incentives to make their bottom lines. “Manufacturers pay slotting fees to get their products on the shelf, and they pay promotion allowances: We’ll give you this much off a carton of Coke if you put it on sale for a certain price or if you put it on an end-of-aisle display,” says José Alvarez, former president and chief executive officer of Stop & Shop/Giant-Landover, now senior lecturer of business administration at Harvard Business School. Such promotional payments, Alvarez adds, often exceed retailers’ net profits.

Healthy new products—like flash-frozen dinners prepared with heaps of vegetables and whole grains, and relatively little salt—can’t compete for prized shelf space against boxed mac and cheese or cloying breakfast cereals. One solution, says Alvarez, is for established consumer packaged goods companies to buy out what he calls the “hippie in the basement” firms that have whipped up more nutritious items. The behemoths could apply their production, marketing, and distribution prowess to the new offerings—and indeed, this has started to happen over the last five years.

Another approach is to make nutritious foods more convenient to eat. “We have all of these cooking shows and upscale food magazines, but most people don’t have the time or inclination—or the skills, quite frankly—to cook,” says Alvarez. “Instead, we should focus on creating high-quality, healthy, affordable prepared foods.”

An additional model is suggested by Jeff Dunn, a 20-year veteran of the soft drink industry and former president of Coca-Cola North America, who went on to become an advocate for fresh, healthy food. Dunn served as president and chief executive officer of Bolthouse Farms from 2008 to 2015, where he dramatically increased sales of baby carrots by using marketing techniques common in the junk food business. “We operated on the principles of the three 3 A’s: accessibility, availability, and affordability,” says Dunn. “That, by the way, is Coke’s more-than-70-year-old formula for success.”

Show them the money.

Obesity kills budgets. According to the Campaign to End Obesity, a collaboration of leaders from industry, academia, public health, and policymakers, annual U.S. health costs related to obesity approach $200 billion. In 2010, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office reported that nearly 20 percent of the rise in health care spending from 1987 to 2007 was linked to obesity. And the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that full-time workers in the U.S. who are overweight or obese and have other chronic health conditions miss an estimated 450 million more days of work each year than do healthy employees—upward of $153 billion in lost productivity annually.

But making the money case for obesity prevention isn’t straightforward. For interventions targeting children and youth, only a small fraction of savings is captured in the first decade, since most serious health complications don’t emerge for many years. Long-term obesity prevention, in other words, doesn’t fit into political timetables for elected officials.

Yet lawmakers are keen to know how “best for the money” obesity-prevention programs can help them in the short run. Over the past two years, Harvard Chan’s Steve Gortmaker and his colleagues have been working with state health departments in Alaska, Mississippi, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Washington, and West Virginia and with the city of Philadelphia and other locales, building cost-effectiveness models using local data for a wide variety of interventions—from improved early child care to healthy school environments to communitywide campaigns. “We collaborate with health departments and community stakeholders, provide them with the evidence base, help assess how much different options cost, model the results over a decade, and they pick what they want to work on. One constant that we’ve seen—and these are very different political environments—is a strong interest in cost-effectiveness,” he says.

In a 2015 study in Health Affairs , Gortmaker and colleagues outlined three interventions that would more than pay for themselves: an excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages implemented at the state level; elimination of the tax subsidy for advertising unhealthy food to children; and strong nutrition standards for food and drinks sold in schools outside of school meals. Implemented nationally, these interventions would prevent 576,000, 129,100, and 345,000 cases of childhood obesity, respectively, by 2025. The projected net savings to society in obesity-related health care costs for each dollar invested: $31, $33, and $4.60, respectively.

Gortmaker is one of the leaders of a collaborative modeling effort known as CHOICES—for Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study—an acronym that seems a pointed rebuttal to the reflexive conservative argument that government regulation tramples individual choice. Having grown up not far from Des Plaines, Illinois, site of the first McDonald’s franchise in the country, he emphasizes to policymakers that at this late date, America cannot treat its way out of obesity, given current medical know-how. Only a thoroughgoing investment in prevention will turn the tide. “Clinical interventions produce too small an effect, with too small a population, and at high cost,” Gortmaker says. “The good news is that there are many cost-effective options to choose from.”

While Gortmaker underscores the importance of improving both food choices and options for physical activity, he has shown that upgrading the food environment offers much more benefit for the buck. This is in line with the gathering scientific consensus that what we eat plays a greater role in obesity than does sedentary lifestyle (although exercise protects against many of the metabolic consequences of excess weight). “The easiest way to explain it,” Gortmaker says, “is to talk about a sugary beverage—140 calories. You could quickly change a kid’s risk of excess energy balance by 140 calories a day just by switching from a sugary drink a day to water or sparkling water. But for a 10-year-old boy to burn an extra 140 calories, he’d have to replace an hour-and-a-half of sitting with an hour-and-a-half of walking.”

Small tweaks in adults’ diets can likewise make a big difference in short order. “With adults, health care costs rise rapidly with excess weight gain,” Gortmaker says. “If you can slow the onset of obesity, you slow the onset of diabetes, and potentially not only save health care costs but also boost people’s productivity in the workforce.”

One of Gortmaker’s most intriguing calculations spins off of the food industry’s estimated $633 million spent on television marketing aimed at kids. Currently, federal tax treatment of advertising as an ordinary business expense means that the government, in effect, subsidizes hawking of junk food to children. Gortmaker modeled a national intervention that would eliminate this subsidy of TV ads for nutritionally empty foods and beverages aimed at 2- to 19-year-olds. Drawing on well-delineated relationships between exposure to these advertisements and subsequent weight gain, he found that the intervention would save $260 million in downstream health care costs. Although the effect would probably be small at the individual level, it would be significant at the population level.

Level the playing field through taxes and regulation.

When public health took on cigarette smoking, starting in the 1960s, it did so with robust policies banning television ads and other marketing, raising taxes to increase prices, making public places smoke-free, and offering people treatment such as the nicotine patch. In 1965, the smoking rate for U.S. adults was 42.2 percent; today, it is 16.8 percent.

Similarly, America reduced the rate of deaths caused by motor vehicle accidents—a 90 percent decrease over the 20th century, according to the CDC—with mandatory seat belt laws, safer car designs, stop signs, speed limits, rumble strips, and the stigmatization of drunk driving.

Change the product. Change the environment. Change the culture. That is also the policy recipe for stopping obesity.

Laws that make healthy behaviors easier are often followed by positive changes in those behaviors. And people who are trying to adopt healthy behaviors tend to support policies that make their personal aspirations achievable, which in turn nudges lawmakers to back the proposals.

One debate today revolves around whether recipients of federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits (formerly known as food stamps) should be restricted from buying sodas or junk food. The largest component of the USDA budget, SNAP feeds one in seven Americans. A USDA report, issued last November, found that the number-one purchase by SNAP households was sweetened beverages, a category that included soft drinks, fruit juices, energy drinks, and sweetened teas, accounting for nearly 10 percent of SNAP money spent on food. Is the USDA therefore underwriting the soda industry and planting the seeds for chronic disease that the government will pay to treat years down the line?

Eric Rimm, a professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Nutrition at the Harvard Chan School, frames the issue differently. In a 2017 study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine , he and his colleagues asked SNAP participants whether they would prefer the standard benefits package or a “SNAP-plus” that prohibited the purchase of sugary beverages but offered 50 percent more money for buying fruits and vegetables. Sixty-eight percent of the participants chose the healthy SNAP-plus option.

“A lot of work around SNAP policy is done by academics and politicians, without reaching out to the beneficiaries,” says Rimm. “We haven’t asked participants, ‘What’s your say in this? How can we make this program better for you?’” To be sure, SNAP is riddled with nutritional contradictions. Under current rules, for example, participants can use benefits to buy a 12-pack of Pepsi or a Snickers bar or a giant bag of Lay’s potato chips but not real food that happens to be heated, such as a package of rotisserie chicken. “This is the most vulnerable population in the country,” says Rimm. “We’re not listening well enough to our constituency.”

Other innovative fiscal levers to alter behavior could also drive down obesity. In 2014, a trio of strong voices on food industry practices—Dariush Mozaffarian, DrPH ’06, dean of Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and former associate professor of epidemiology at the Harvard Chan School; Kenneth Rogoff, professor of economics at Harvard; and David Ludwig, professor in the Department of Nutrition at Harvard Chan and a physician at Boston Children’s Hospital—broached the idea of a “meaningful” tax on nearly all packaged retail foods and many chain restaurants, with the proceeds used to pay for minimally processed foods and healthier meals for school kids. In essence, the tax externalizes the social costs of harmful individual behavior.

“We made a straightforward proposal to tax all processed foods and then use the income to subsidize whole foods in a short-term, revenue-neutral way,” explains Ludwig. “The power of this idea is that, since there is so much processed food consumption, even a modest tax—in the 10 to 15 percent range—is not going to greatly inflate the cost of these foods. Their price would increase moderately, but the proceeds would not disappear into government coffers. Instead, the revenue would make healthy foods affordable for virtually the entire population, and the benefits would be immediately evident. Yes, people will pay moderately more for their Coke or for their cinnamon bear claw but a lot less for nourishing, whole foods.”

Another suggestion comes from Sandro Galea, dean of the Boston University School of Public Health, and Abdulrahman M. El-Sayed, a public health physician and epidemiologist. In a 2015 issue of the American Journal of Public Health , they called for “calorie offsets,” similar to the carbon offsets used to mitigate environmental harm caused by the gas and oil industries. A “calorie offset” scheme could hand the food and beverage industries a chance at redemption by inviting them to invest in such undertakings as city farms, cooking classes for parents, healthy school cafeterias, and urban green spaces.

These ambitious proposals face almost impossibly high hurdles. Political battle lines typically pit public health against corporations, with Big Food casting doubt on solid nutrition science, deeming government regulation a threat to free choice, and making self-policing pledges that it has never kept. On the website for the Americans for Food and Beverage Choice, a group spearheaded by the American Beverage Association, is the admonition: “[W]hether it’s at a restaurant or in a grocery store, it’s never the government’s job to decide what you choose to eat and drink.”

Yet surprisingly, many public health professionals are convinced that the only way to stop obesity is to make common cause with the food industry. “This isn’t like tobacco, where it’s a fight to the death. We need the food industry to make healthier food and to make a profit,” says Mozaffarian. “The food industry is much more diverse and heterogeneous than tobacco or even cars. As long as we can help them—through carrots and sticks, tax incentives and disincentives—to move towards healthier products, then they are part of the solution. But we have to be vigilant, because they use a lot of the same tactics that tobacco did.”

Sow what we want to reap.

Americans overeat what our farmers overproduce.

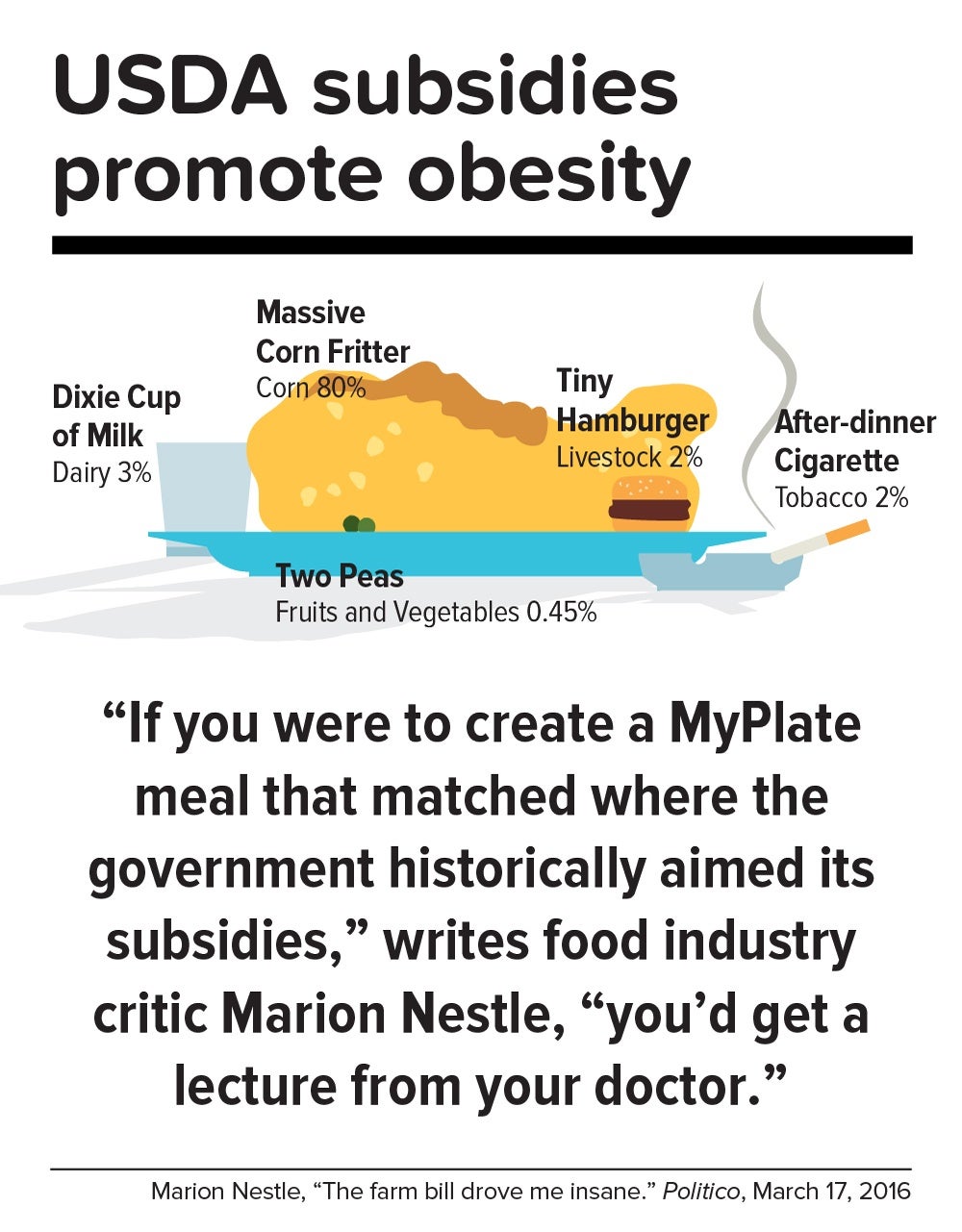

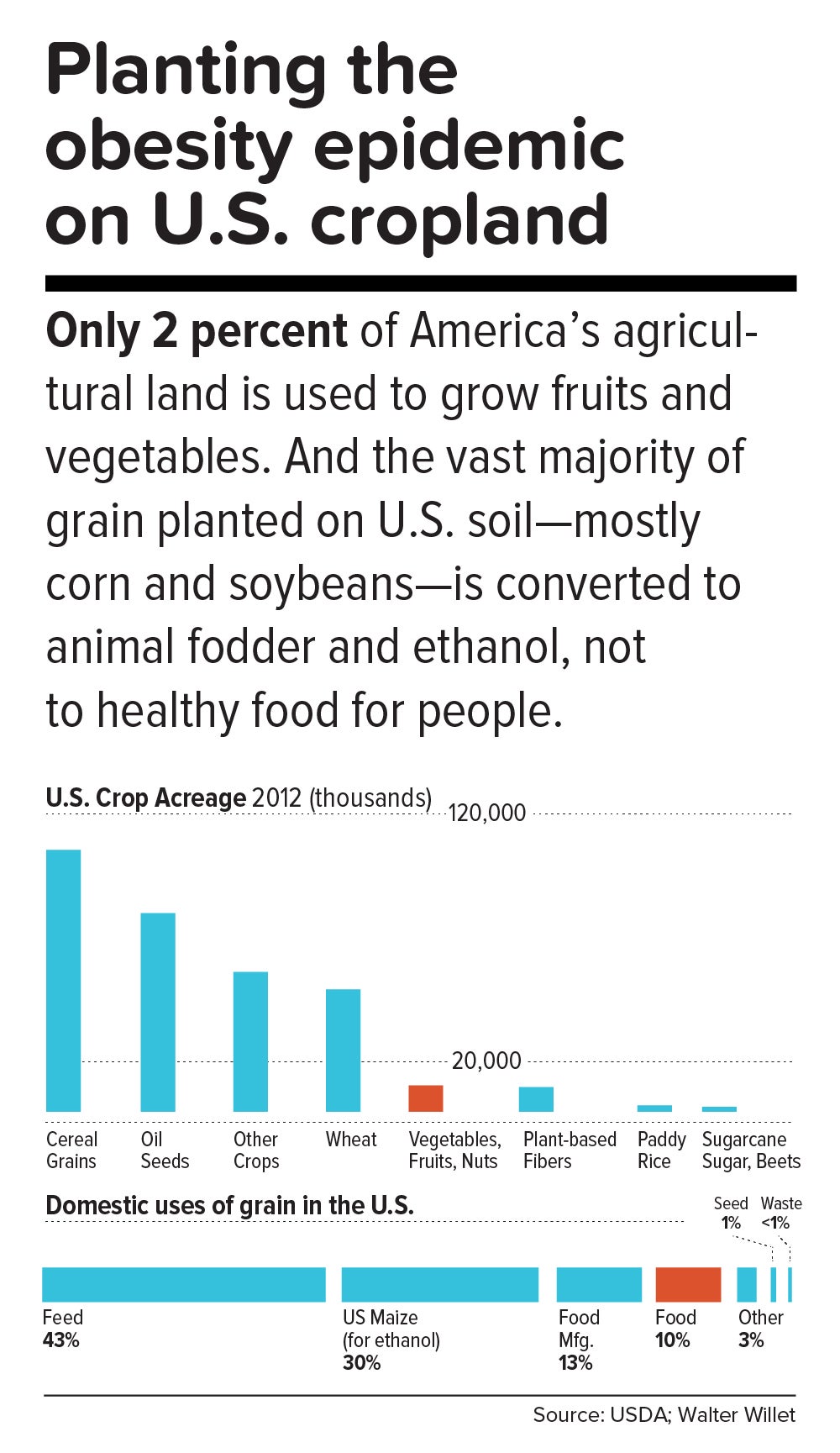

“The U.S. food system is egregiously terrible for human and planetary health,” says Walter Willett. It’s so terrible, Willett made a pie chart of American grain production consumed domestically. It shows that most of the country’s agricultural land goes to the two giant commodity crops: corn and soy. Most of those crops, in turn, go to animal fodder and ethanol, and are also heavily used in processed snack foods. Today, only about 10 percent of grain grown in the U.S. for domestic use is eaten directly by human beings. According to a 2013 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists, only 2 percent of U.S. farmland is used to grow fruits and vegetables, while 59 percent is devoted to commodity crops.

Historically, those skewed proportions made sense. Federal food policies, drafted with the goal of alleviating hunger, preferentially subsidize corn and soy production. And whereas corn or soybeans could be shipped for days on a train, fruits and vegetables had to be grown closer to cities by truck farmers so the produce wouldn’t spoil. But those long-ago constraints don’t explain today’s upside-down agricultural priorities.

In a now-classic 2016 Politico article titled “The farm bill drove me insane,” Marion Nestle illustrated the irrational gap between what the government recommends we eat and what it subsidizes: “If you were to create a MyPlate meal that matched where the government historically aimed its subsidies, you’d get a lecture from your doctor. More than three-quarters of your plate would be taken up by a massive corn fritter (80 percent of benefits go to corn, grains and soy oil). You’d have a Dixie cup of milk (dairy gets 3 percent), a hamburger the size of a half dollar (livestock: 2 percent), two peas (fruits and vegetables: 0.45 percent) and an after-dinner cigarette (tobacco: 2 percent). Oh, and a really big linen napkin (cotton: 13 percent) to dab your lips.”

In this sense, the USDA marginalizes human health. Many of the foods that nutritionists agree are best for us—notably, fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts—fall under the bureaucratic rubric “specialty crops,” a category that also includes “dried fruits, horticulture, and nursery crops (including floriculture).” Farm bills, which get passed every five years or so, fortify the status quo. The 2014 Farm Bill, for example, provided $73 million for the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program in 2017, out of a total of about $25 billion for the USDA’s discretionary budget. (The next Farm Bill, now under debate, will be coming out in 2018.)

By contrast, a truly anti-obesigenic agricultural system would stimulate USDA support for crop diversity—through technical assistance, research, agricultural training programs, and financial aid for farmers who are newly planting or transitioning their land into produce. It would also enable farmers, most of whom survive on razor-thin profit margins, to make a decent living.

In the early 1970s, Finland’s death rate from coronary heart disease was the highest in the world, and in the eastern region of North Karelia—a pristine, sparsely populated frontier landscape of forest and lakes—the rate was 40 percent worse than the national average. Every family saw physically active men, loggers and farmers who were strong and lean, dying in their prime.

Thus was born the North Karelia Project, which became a model worldwide for saving lives by transforming lifestyles. The project was launched in 1972 and officially ended 25 years later. While its initial goal was to reduce smoking and saturated fat in the diet, it later resolved to increase fruit and vegetable consumption.

The North Karelia Project fulfilled all of these ambitions. When it started, for example, 86 percent of men and 82 percent of women smeared butter on their bread; by the early 2000s, only 10 percent of men and 4 percent of women so indulged. Use of vegetable oil for cooking jumped from virtually zero in 1970 to 50 percent in 2009. Fruit and vegetables, once rare visitors to the dinner plate, became regulars. Over the project’s official quarter-century existence, coronary heart disease deaths in working-age North Karelian men fell 82 percent, and life expectancy rose seven years.

The secret of North Karelia’s success was an all-out philosophy. Team members spent innumerable hours meeting with residents and assuring them that they had the power to improve their own health. The volunteers enlisted the assistance of an influential women’s group, farmers’ unions, homemakers’ organizations, hunting clubs, and church congregations. They redesigned food labels and upgraded health services. Towns competed in cholesterol-cutting contests. The national government passed sweeping legislation (including a total ban on tobacco advertising). Dairy subsidies were thrown out. Farmers were given strong incentives to produce low-fat milk, or to get paid for meat and dairy products based not on high-fat but on high-protein content. And the newly established East Finland Berry and Vegetable Project helped locals switch from dairy farming—which had made up more than two-thirds of agriculture in the region—to cultivation of cold-hardy currants, gooseberries, and strawberries, as well as rapeseed for heart-healthy canola oil.

“A mass epidemic calls for mass action,” says the project’s director, Pekka Puska, “and the changing of lifestyles can only succeed through community action. In this case, the people pulled the government—the government didn’t pull the people.”

Could the United States in 2017 learn from North Karelia’s 1970s grand experiment?

“Americans didn’t become an obese nation overnight. It took a long time—several decades, the same timeline as in individuals,” notes Frank Hu. “What were we doing over the past 20 years or 30 years, before we crossed this threshold? We haven’t asked these questions. We haven’t done this kind of soul-searching, as individuals or society as a whole.”

Today, Americans may finally be willing to take a hard look at how food figures in their lives. In a July 2015 Gallup phone poll of Americans 18 and older, 61 percent said they actively try to avoid regular soda (the figure was 41 percent in 2002); 50 percent try to avoid sugar; and 93 percent try to eat vegetables (but only 57.7 percent in 2013 reported they ate five or more servings of fruits and vegetables at least four days of the previous week).

Individual resolve, of course, counts for little in problems as big as the obesity epidemic. Most successes in public health bank on collective action to support personal responsibility while fighting discrimination against an epidemic’s victims. [To learn more about the perils of stigma against people with obesity, read “ The Scarlet F .”]

Yet many of public health’s legendary successes also took what seems like an agonizingly long time to work. Do we have that luxury?

“Right now, healthy eating in America is like swimming upstream. If you are a strong swimmer and in good shape, you can swim for a little while, but eventually you’re going to get tired and start floating back down,” says Margo Wootan, SD ’93, director of nutrition policy for the Center for Science in the Public Interest. “If you’re distracted for a second—your kid tugs on your pant leg, you had a bad day, you’re tired, you’re worried about paying your bills—the default options push you toward eating too much of the wrong kinds of food.”

But Wootan has not lowered her sights. “What we need is mobilization,” she says. “Mobilize the public to address nutrition and obesity as societal problems—recognizing that each of us makes individual choices throughout the day, but that right now the environment is stacked against us. If we don’t change that, stopping obesity will be impossible.”