- Inflation Calculator

Current US Inflation Rates: 2000-2024

- Historical Inflation Rates: 1914-2024

- Consumer Price Index Data from 1913 to 2024

- Consumer Price Index – Release Schedule

- Inflation vs. Consumer Price Index (CPI), How They Are Different

- Core Inflation Rates

- Rates for I Bonds

- Grocery Store Prices

- Energy Prices: Gasoline, Electricity and Fuel Oil

- Average Inflation Rates

- Monthly US Inflation Rates: 1913-Present

- Gasoline Inflation (1968-2023)

- Food Inflation (1968-2023)

- Health Care Inflation (1948-2023)

- College Inflation (1978-2023)

- Airfare Inflation (1964-2023)

- Gasoline Prices Adjusted for Inflation

- Electricity Prices By Year And Adjusted For Inflation

- Milk Prices By Year And Adjusted For Inflation

- Coffee Prices By Year And Adjusted For Inflation

- Bacon Prices By Year And Adjusted For Inflation

- Egg Prices By Year And Adjusted For Inflation

- Inflation Calculator: By Month and Year (1913-2023)

- Inflation in New York, Newark and Jersey City Metropolitan Area

- Inflation in Los Angeles, Long Beach and Anaheim Metropolitan Area

- About & Contact Us

SOURCES: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Haver Analytics.

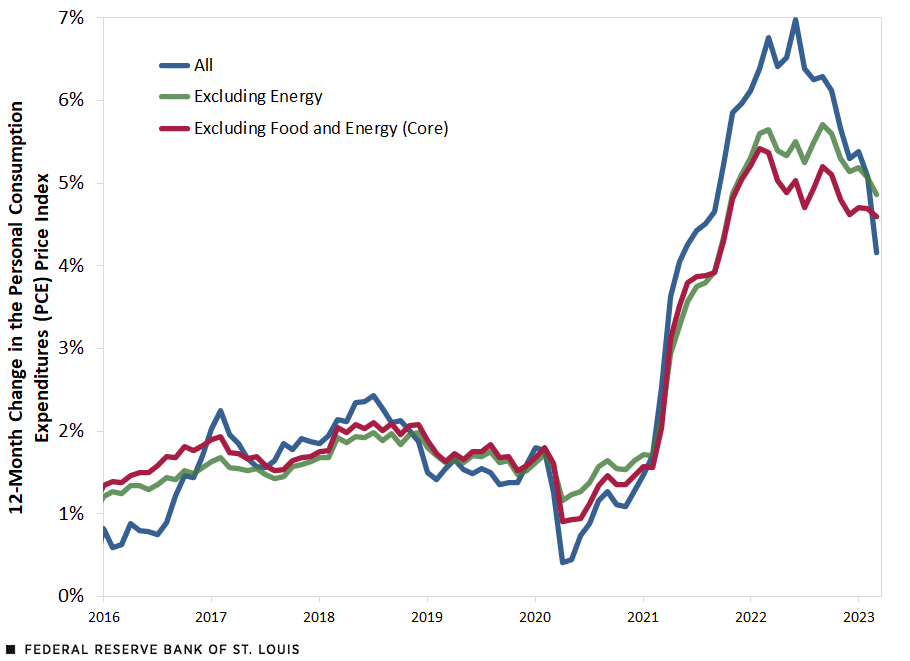

In the period prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, prices were growing at an average annual rate of 1.8%, slightly below the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. This growth process, which we call inflation, was arrested at the onset of the pandemic and resumed toward the end of 2020, though at a significantly faster rate. We can see that energy prices played an important role in this period, as the acceleration and subsequent deceleration in inflation were less pronounced once we excluded them. The index excluding energy and food and the index excluding energy show a steadier, more consistent increase.

The second figure shows inflation rates, measured as the 12-month change in the corresponding price index. For all three indexes considered, annual inflation has persistently exceeded 2% since March 2021. This figure shows clearly how energy contributed to inflation dynamics. However, when we exclude energy prices, inflation is still very high, staying over 5% annually for all of 2022 and just under 5% in March 2023. When looking at core PCE, i.e., excluding both food and energy, there is a modest moderation in inflation from its peak, but it is much less pronounced than with headline inflation.

Annualized PCE Inflation Rates

The first table provides a summary of inflation rates over various periods of interest. The first, 2016-19, covers the years immediately prior to the pandemic, when inflation was close to the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. Next are the years 2020, 2021 and 2022. Finally, the period labeled “COVID-19” covers the whole pandemic period, between March 2020 and March 2023. All inflation rates are annualized to make them comparable across periods of different lengths.

The table highlights how inflation accelerated in 2021 and 2022. Overall, the aggregate price level rose at an average annual rate of 4.3% since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This rate moderates to 4.1% annually when we exclude energy prices and 3.9% annually when we exclude both food and energy prices. These rates are between 2.1 and 2.5 percentage points higher than the pre-pandemic period and well in excess of the Federal Reserve’s 2% target.

Breaking Down Inflation

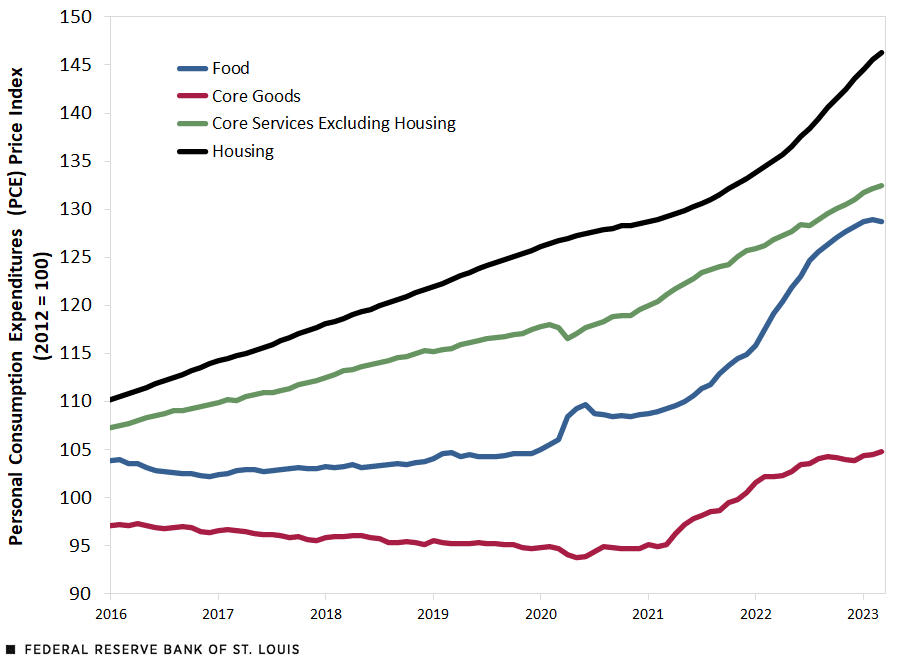

The second table decomposes inflation excluding energy into four big categories: food, core goods, core services excluding housing, and housing. The contribution of these components in total consumption expenditures is, roughly, 8%, 22%, 50% and 16%, respectively (the remaining 4% reflects expenditures in energy goods and services).

The behavior of these components was very different during the pre-pandemic period: Food experienced almost no inflation, core goods prices were actually declining (mostly driven by durables), while core services excluding housing and housing were both growing above the Federal Reserve’s target rate. The pandemic changed these trends: Since 2021, all components have been growing at rates higher than 2% annually. For the overall pandemic period, food experienced the fastest inflation rate (6.6% annually), followed by housing (4.8% annually). In recent communications, Fed Chair Jerome Powell has identified the category “core services excluding housing” as key in understanding inflation dynamics. As Powell explained in his Nov. 30, 2022, speech, the reason is that “ wages make up the largest cost in delivering these services .” Inflation in this category has largely behaved the same as for the core price index and remains well above 2%.

Components of the PCE Price Index Excluding Energy

Above, the third figure shows the evolution of prices of the main components discussed earlier.

Notably, the price of core goods seems to have stabilized during the second half of 2022, while inflation in food prices has decelerated markedly over the same period. In contrast, the rate at which the price of core services excluding housing is increasing shows no signs of slowing down. Similarly, housing services actually experienced a significant acceleration in inflation in 2022. It is well understood that housing prices tend to lag other prices, This is because rents are renewed infrequently (e.g., once a year) and because owner-occupied housing prices are also measured largely using rent data. so the most recent observations may reflect this lag rather than a current trend. Even if this were the case, core services excluding housing—which account for half of consumption expenditures—continue to rise steadily and are a major contributor to overall inflation.

Inflation Is Widespread

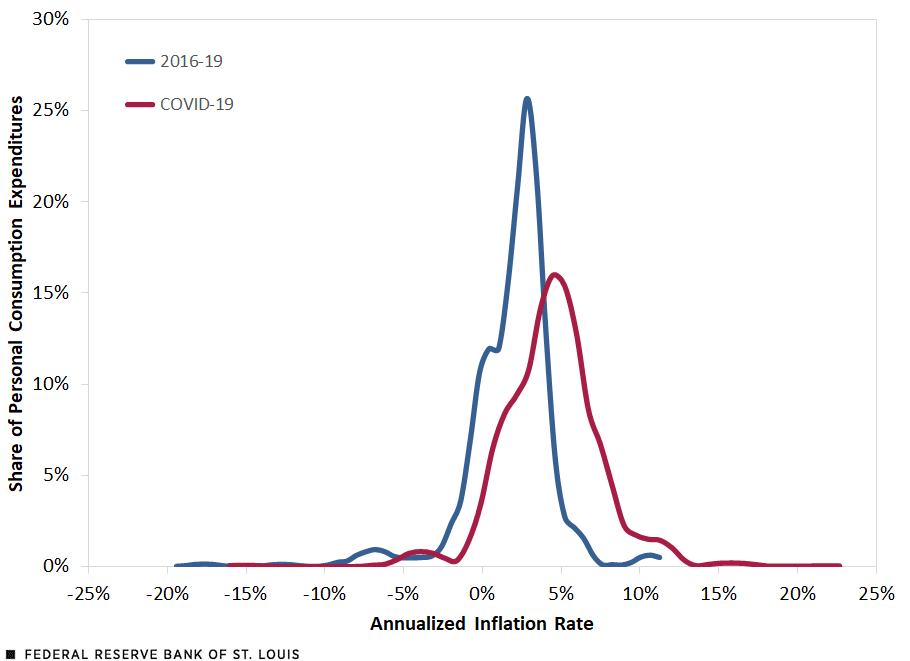

We can further analyze inflation across individual product categories by computing their annualized price change and expenditure share in each period. The fourth figure estimates the distribution of inflation across product categories, with annualized price changes on the horizontal axes and the corresponding expenditure shares on the vertical axes. The disaggregated data published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis consist of 244 product categories with monthly series on expenditures, prices and real quantities. There is some double counting in the report, so the actual number of product categories is slightly smaller. See NIPA tables 2.4.4U, 2.4.5U and 2.4.6U. For a full description of the methodology, see my blog post “ How Widespread Are Price Increases in the U.S.? ” (Oct. 19, 2021). I considered two periods: the pre-pandemic period (2016-19) and the COVID-19 period (March 2020 to March 2023). Focusing on the COVID-19 period as a whole removes the effects of temporary surges in prices and provides a better overall picture.

Estimated Distribution of PCE Inflation

SOURCES: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

NOTES: Distributions are computed with kernel density estimation in Stata, using the optimal bandwidth for each period. The COVID-19 period covers March 2020 to March 2023.

The pandemic has shifted the distribution of inflation to the right. That is, during the COVID-19 period, a larger share of consumption expenditures were on products that experienced higher inflation rates than in the pre-pandemic years. The current high inflation episode is a widespread phenomenon and not the result of a few outliers.

The distribution of inflation across product categories also highlights several important differences between the pre-pandemic and COVID-19 periods. From 2016 to 2019, 18% of consumption expenditures were on products experiencing negative inflation; this proportion drops to less than 1% in the COVID-19 period. Conversely, the share of expenditures on products experiencing more than 5% annual inflation was only 5% in the pre-pandemic period and rose to over 40% during the COVID-19 period. These are significant changes that help us understand the nature of the current high inflation.

In my next post , I’ll examine the impact of fiscal and monetary policies during this inflationary episode and provide a plausible outlook for the near future.

- For previous work on this subject, see my blog posts “ 2021: The Year of High Inflation ” (April 12, 2022) and “ Inflation Is Still High and Widespread ” (Oct. 17, 2022).

- There are many alternative measures of underlying or trend inflation. For a recent take, see Kevin Kliesen’s April 18, 2023, Economic Synopses essay, “ Measures of ‘Trend’ Inflation .”

- As Powell explained in his Nov. 30, 2022, speech, the reason is that “ wages make up the largest cost in delivering these services .”

- This is because rents are renewed infrequently (e.g., once a year) and because owner-occupied housing prices are also measured largely using rent data.

- The disaggregated data published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis consist of 244 product categories with monthly series on expenditures, prices and real quantities. There is some double counting in the report, so the actual number of product categories is slightly smaller. See NIPA tables 2.4.4U, 2.4.5U and 2.4.6U. For a full description of the methodology, see my blog post “ How Widespread Are Price Increases in the U.S.? ” (Oct. 19, 2021).

Fernando M. Martin is an economist and senior economic policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. His research interests include macroeconomics, monetary economics, banking and public finance. He joined the St. Louis Fed in 2011. Read more about his work .

Related Topics

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Media questions

All other blog-related questions

What is inflation?

Inflation has been top of mind for many over the past few years. But how long will it persist? In June 2022, inflation in the United States jumped to 9.1 percent, reaching the highest level since February 1982. The inflation rate has since slowed in the United States , as well as in Europe , Japan , and the United Kingdom , particularly in the final months of 2023. But even though global inflation is higher than it was before the COVID-19 pandemic, when it hovered around 2 percent, it’s receding to historical levels . In fact, by late 2022, investors were predicting that long-term inflation would settle around a modest 2.5 percent. That’s a far cry from fears that long-term inflation would mimic trends of the 1970s and early 1980s—when inflation exceeded 10 percent.

Get to know and directly engage with senior McKinsey experts on inflation.

Ondrej Burkacky is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Munich office, Axel Karlsson is a senior partner in the Stockholm office, Fernando Perez is a senior partner in the Miami office, Emily Reasor is a senior partner in the Denver office, and Daniel Swan is a senior partner in the Stamford, Connecticut, office.

Inflation refers to a broad rise in the prices of goods and services across the economy over time, eroding purchasing power for both consumers and businesses. Economic theory and practice, observed for many years and across many countries, shows that long-lasting periods of inflation are caused in large part by what’s known as an easy monetary policy . In other words, when a country’s central bank sets the interest rate too low or increases money growth too rapidly, inflation goes up. As a result, your dollar (or whatever currency you use) will not go as far today as it did yesterday. For example: in 1970, the average cup of coffee in the United States cost 25 cents; by 2019, it had climbed to $1.59. So for $5, you would have been able to buy about three cups of coffee in 2019, versus 20 cups in 1970. That’s inflation, and it isn’t limited to price spikes for any single item or service; it refers to increases in prices across a sector, such as retail or automotive—and, ultimately, a country’s economy.

How does inflation affect your daily life? You’ve probably seen high rates of inflation reflected in your bills—from groceries to utilities to even higher mortgage payments. Executives and corporate leaders have had to reckon with the effects of inflation too, figuring out how to protect margins while paying more for raw materials.

But inflation isn’t all bad. In a healthy economy, annual inflation is typically in the range of two percentage points, which is what economists consider a sign of pricing stability. When inflation is in this range, it can have positive effects: it can stimulate spending and thus spur demand and productivity when the economy is slowing down and needs a boost. But when inflation begins to surpass wage growth, it can be a warning sign of a struggling economy.

Introducing McKinsey Explainers : Direct answers to complex questions

Inflation may be declining in many markets, but there’s still uncertainty ahead: without a significant surge in productivity, Western economies may be headed for a period of sustained inflation or major economic reset , as Japan has experienced in the first decades of the 21st century.

What does seem to be changing are leaders’ attitudes. According to the 2023 year-end McKinsey Global Survey on economic conditions , respondents reported less fear about inflation as a risk to global and domestic economic growth . But this sentiment varies significantly by region: European respondents were most concerned about the effects of inflation, whereas respondents in North America offered brighter views.

What causes inflation?

Monetary policy is a critical driver of inflation over the long term. The current high rate of inflation is a result of increased money supply , high raw materials costs , labor mismatches , and supply disruptions —exacerbated by geopolitical conflict .

In general, there are two primary types, or causes, of short-term inflation:

- Demand-pull inflation occurs when the demand for goods and services in the economy exceeds the economy’s ability to produce them. For example, when demand for new cars recovered more quickly than anticipated from its sharp dip at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, an intervening shortage in the supply of semiconductors made it hard for the automotive industry to keep up with this renewed demand. The subsequent shortage of new vehicles resulted in a spike in prices for new and used cars.

- Cost-push inflation occurs when the rising price of input goods and services increases the price of final goods and services. For example, commodity prices spiked sharply during the pandemic as a result of radical shifts in demand, buying patterns, cost to serve, and perceived value across sectors and value chains. To offset inflation and minimize impact on financial performance, industrial companies were forced to increase prices for end consumers.

Learn more about McKinsey’s Growth, Marketing & Sales Practice.

What are some periods in history with high inflation?

Economists frequently compare the current inflationary period with the post–World War II era , when price controls, supply problems, and extraordinary demand in the United States fueled double-digit inflation gains—peaking at 20 percent in 1947—before subsiding at the end of the decade. Consumption patterns today have been similarly distorted, and supply chains have been disrupted by the pandemic.

The period from the mid-1960s through the early 1980s in the United States, sometimes called the “Great Inflation,” saw some of the country’s highest rates of inflation, with a peak of 14.8 percent in 1980. To combat this inflation, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates to nearly 20 percent. Some economists attribute this episode partially to monetary policy mistakes rather than to other causes, such as high oil prices. The Great Inflation signaled the need for public trust in the Federal Reserve’s ability to lessen inflationary pressures.

Inflation isn’t solely a modern-day phenomenon, of course. One very early example of inflation comes from Roman times, from around 200 to 300 CE. Roman leaders were struggling to fund an army big enough to deal with attackers from multiple fronts. To help, they watered down the silver in their coinage, causing the value of money to slowly fall—and inflation to pick up. This led merchants to raise their prices, causing widespread panic. In response, the emperor Diocletian issued what’s now known as the Edict on Maximum Prices, a series of price and wage controls designed to stop the rise of prices and wages (one helpful control was a maximum price for a male lion). But because the edict didn’t address the root cause of inflation—the impure silver coin—it didn’t fix the problem.

How is inflation measured?

Statistical agencies measure inflation first by determining the current value of a “basket” of various goods and services consumed by households, referred to as a price index. To calculate the rate of inflation over time, statisticians compare the value of the index over one period with that of another. Comparing one month with another gives a monthly rate of inflation, and comparing from year to year gives an annual rate of inflation.

In the United States, the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes its Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures the cost of items that urban consumers buy out of pocket. The CPI is broken down by region and is reported for the country as a whole. The Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index —published by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis—takes into account a broader range of consumer spending, including on healthcare. It is also weighted by data acquired through business surveys.

How does inflation affect consumers and companies differently?

Inflation affects consumers most directly, but businesses can also feel the impact:

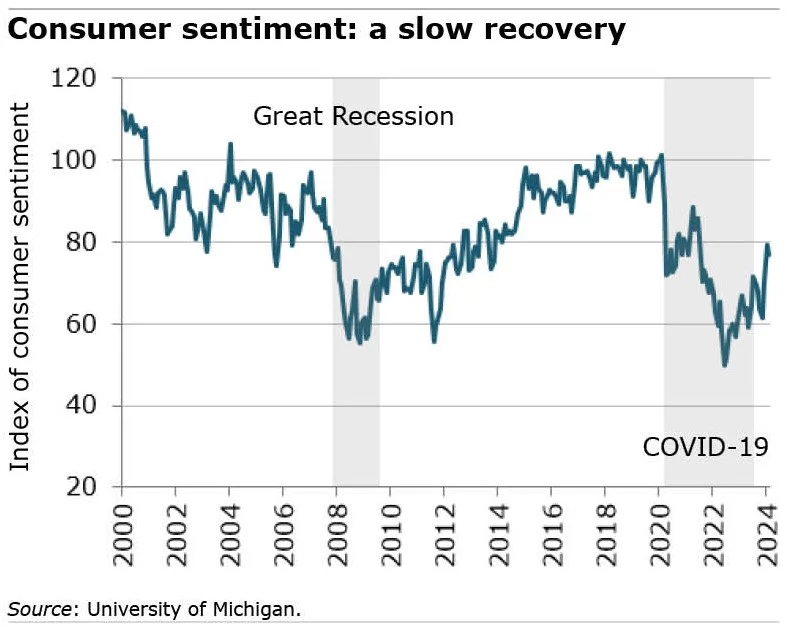

- Consumers lose purchasing power when the prices of items they buy, such as food, utilities, and gasoline, increase. This can lead to household belt-tightening and growing pessimism about the economy .

- Companies lose purchasing power and risk seeing their margins decline , when prices increase for inputs used in production. These can include raw materials like coal and crude oil , intermediate products such as flour and steel, and finished machinery. In response, companies typically raise the prices of their products or services to offset inflation, meaning consumers absorb these price increases. The challenge for many companies is to strike the right balance between raising prices to cover input cost increases while simultaneously ensuring that they don’t raise prices so much that they suppress demand.

How can organizations respond to high inflation?

During periods of high inflation, companies typically pay more for materials , which decreases their margins. One way for companies to offset losses and maintain margins is by raising prices for consumers. However, if price increases are not executed thoughtfully, companies can damage customer relationships and depress sales —ultimately eroding the profits they were trying to protect.

When done successfully, recovering the cost of inflation for a given product can strengthen relationships and overall margins. There are five steps companies can take to ADAPT (adjust, develop, accelerate, plan, and track) to inflation:

- Adjust discounting and promotions and maximize nonprice levers. This can include lengthening production schedules or adding surcharges and delivery fees for rush or low-volume orders.

- Develop the art and science of price change. Instead of making across-the-board price changes, tailor pricing actions to account for inflation exposure, customer willingness to pay, and product attributes.

- Accelerate decision making tenfold. Establish an “inflation council” that includes dedicated cross-functional, inflation-focused decision makers who can act quickly and nimbly on customer feedback.

- Plan options beyond pricing to reduce costs. Use “value engineering” to reimagine a portfolio and provide cost-reducing alternatives to price increases.

- Track execution relentlessly. Create a central supporting team to address revenue leakage and to manage performance rigorously. Traditional performance metrics can be less reliable when inflation is high .

Beyond pricing, a variety of commercial and technical levers can help companies deal with price increases in an inflationary market , but other sectors may require a more tailored response to pricing.

Learn more about our Financial Services , Industrials & Electronics , Operations , Strategy & Corporate Finance , and Growth, Marketing & Sales Practices.

How can CEOs help protect their organizations against uncertainty during periods of high inflation?

In today’s uncertain environment, in which organizations have a much wider range of stakeholders, leaders must think about performance beyond short-term profitability. CEOs should lead with the complete business cycle and their complete slate of stakeholders in mind.

CEOs need an inflation management playbook , just as central bankers do. Here are some important areas to keep in mind while scripting it:

- Design. Leaders should motivate their organizations to raise the profile of design to a C-suite topic. Design choices for products and services are critical for responding to price volatility, scarcity of components, and higher production and servicing costs.

- Supply chain. The most difficult task for CEOs may be convincing investors to accept supply chain resiliency as the new table stakes. Given geopolitical and economic realities, supply chain resiliency has become a crucial goal for supply chain leaders, alongside cost optimization.

- Procurement. CEOs who empower their procurement organizations can raise the bar on value-creating contributions. Procurement leaders have told us time and again that the current market environment is the toughest they’ve experienced in decades. CEOs are beginning to recognize that purchasing leaders can be strategic partners by expanding their focus beyond cost cutting to value creation.

- Feedback. A CEO can take a lead role in playing back the feedback the organization is hearing. In today’s tight labor market, CEOs should guide their companies to take a new approach to talent, focusing on compensation, cultural factors, and psychological safety .

- Pricing. Forging new pricing relationships with customers will test CEOs in their role as the “ultimate integrator.” Repricing during inflationary times is typically unpleasant for companies and customers alike. With setting new prices, CEOs have the opportunity to forge deeper relationships with customers, by turning to promotions, personalization , and refreshed communications around value.

- Agility. CEOs can strive to achieve a focus based more on strategic action and less on firefighting. Managing the implications of inflation calls for a cross-functional, disciplined, and agile response.

A practical example: How is inflation affecting the US healthcare industry?

Consumer prices for healthcare have rarely risen faster than the rate of inflation—but that’s what’s happening today. The impact of inflation on the broader economy has caused healthcare costs to rise faster than the rate of inflation. Experts also expect continued labor shortages in healthcare—gaps of up to 450,000 registered nurses and 80,000 doctors —even as demand for services continues to rise. This drives up consumer prices and means that higher inflation could persist. McKinsey analysis as of 2022 predicted that the annual US health expenditure is likely to be $370 billion higher by 2027 because of inflation.

This climate of risk could spur healthcare leaders to address productivity, using tech levers to boost productivity while also reducing costs. In order to weather the storm, leaders will need to quickly set high aspirations, align their organizations around them, and execute with speed .

What is deflation?

If inflation is one extreme of the pricing spectrum, deflation is the other. Deflation occurs when the overall level of prices in an economy declines and the purchasing power of currency increases. It can be driven by growth in productivity and the abundance of goods and services, by a decrease in demand, or by a decline in the supply of money and credit.

Generally, moderate deflation positively affects consumers’ pocketbooks, as they can purchase more with less money. However, deflation can be a sign of a weakening economy, leading to recessions and depressions. While inflation reduces purchasing power, it also reduces the value of debt. During a period of deflation, on the other hand, debt becomes more expensive. And for consumers, investments such as stocks, corporate bonds, and real estate become riskier.

A recent period of deflation in the United States was the Great Recession, between 2007 and 2008. In December 2008, more than half of executives surveyed by McKinsey expected deflation in their countries, and 44 percent expected to decrease the size of their workforces.

When taken to their extremes, both inflation and deflation can have significant negative effects on consumers, businesses, and investors.

For more in-depth exploration of these topics, see McKinsey’s Operations Insights collection. Learn more about Operations consulting , and check out operations-related job opportunities if you’re interested in working at McKinsey.

Articles referenced:

- “ Investing in productivity growth ,” March 27, 2024, Jan Mischke , Chris Bradley , Marc Canal, Olivia White , Sven Smit , and Denitsa Georgieva

- “ Economic conditions outlook during turbulent times, December 2023 ,” December 20, 2023

- “ Forward Thinking on why we ignore inflation—from ancient times to the present—at our peril with Stephen King ,” November 1, 2023

- “ Procurement 2023: Ten CPO actions to defy the toughest challenges ,” March 6, 2023, Roman Belotserkovskiy , Carolina Mazuera, Marta Mussacaleca , Marc Sommerer, and Jan Vandaele

- “ Why you can’t tread water when inflation is persistently high ,” February 2, 2023, Marc Goedhart and Rosen Kotsev

- “ Markets versus textbooks: Calculating today’s cost of equity ,” January 24, 2023, Vartika Gupta, David Kohn, Tim Koller , and Werner Rehm

- “ Inflation-weary Americans are increasingly pessimistic about the economy ,” December 13, 2022, Gonzalo Charro, Andre Dua , Kweilin Ellingrud , Ryan Luby, and Sarah Pemberton

- “ Inflation fighter and value creator: Procurement’s best-kept secret ,” October 31, 2022, Roman Belotserkovskiy , Ezra Greenberg , Daphne Luchtenberg, and Marta Mussacaleca

- “ Prime Numbers: Rethink performance metrics when inflation is high ,” October 28, 2022, Vartika Gupta, David Kohn, Tim Koller , and Werner Rehm

- “ The gathering storm: The threat to employee healthcare benefits ,” October 20, 2022, Aditya Gupta , Akshay Kapur , Monisha Machado-Pereira , and Shubham Singhal

- “ Utility procurement: Ready to meet new market challenges ,” October 7, 2022, Roman Belotserkovskiy , Abhay Prasanna, and Anton Stetsenko

- “ The gathering storm: The transformative impact of inflation on the healthcare sector ,” September 19, 2022, Addie Fleron, Aneesh Krishna , and Shubham Singhal

- “ Pricing during inflation: Active management can preserve sustainable value ,” August 19, 2022, Niels Adler and Nicolas Magnette

- “ Navigating inflation: A new playbook for CEOs ,” April 14, 2022, Asutosh Padhi , Sven Smit , Ezra Greenberg , and Roman Belotserkovskiy

- “ How business operations can respond to price increases: A CEO guide ,” March 11, 2022, Andreas Behrendt , Axel Karlsson , Tarek Kasah, and Daniel Swan

- “ Five ways to ADAPT pricing to inflation ,” February 25, 2022, Alex Abdelnour , Eric Bykowsky, Jesse Nading, Emily Reasor , and Ankit Sood

- “ How COVID-19 is reshaping supply chains ,” November 23, 2021, Knut Alicke , Ed Barriball , and Vera Trautwein

- “ Navigating the labor mismatch in US logistics and supply chains ,” December 10, 2021, Dilip Bhattacharjee , Felipe Bustamante, Andrew Curley, and Fernando Perez

- “ Coping with the auto-semiconductor shortage: Strategies for success ,” May 27, 2021, Ondrej Burkacky , Stephanie Lingemann, and Klaus Pototzky

This article was updated in April 2024; it was originally published in August 2022.

Want to know more about inflation?

Related articles.

What is supply chain?

How business operations can respond to price increases: A CEO guide

Five ways to ADAPT pricing to inflation

Unpacking the Causes of Pandemic-Era Inflation in the US

After several decades of relatively low and stable inflation, in 2021 the US experienced a sharp rise in the pace of price increases. The annual inflation rate, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, was 1.7 percent in February 2021 but rose to more than 5 percent in June 2021. It continued rising for another year, peaking at about 9 percent in June 2022.

The rise in the inflation rate has been attributed to many factors. The US response to the COVID-19 pandemic included a series of federal initiatives, notably the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan, which collectively authorized roughly $5 trillion in government spending. These programs contributed to strong consumer and business demand, which tightened labor markets (between mid-2021 and early 2022 the ratio of job vacancies to unemployed workers doubled), putting upward pressure on wages and prices.

Rising commodity prices and supply chain disruptions were the principal triggers of the recent burst of inflation. But, as these factors have faded, tight labor markets and wage pressures are becoming the main drivers of the lower, but still elevated, rate of price increase.

On the supply side, supply chain disruptions had an important inflationary impact, particularly in 2021 and 2022. The auto industry is a case in point. US auto production dropped from 11.7 million vehicles in July 2020, roughly the pre-pandemic rate, to less than 9 million in the fall of 2021, reflecting shortages of computer chips and other inputs. The combination of strong demand and supply chain bottlenecks led to further pressure on prices, particularly on prices of durable goods. Rising prices of food and energy added importantly to inflation. Notably, the crude oil market was disrupted by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022. The price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil rose from less than $70 per barrel in the late summer of 2021 to more than $100 per barrel for most of the period between March and July of 2022, pushing up gasoline prices and the costs of many industrial inputs.

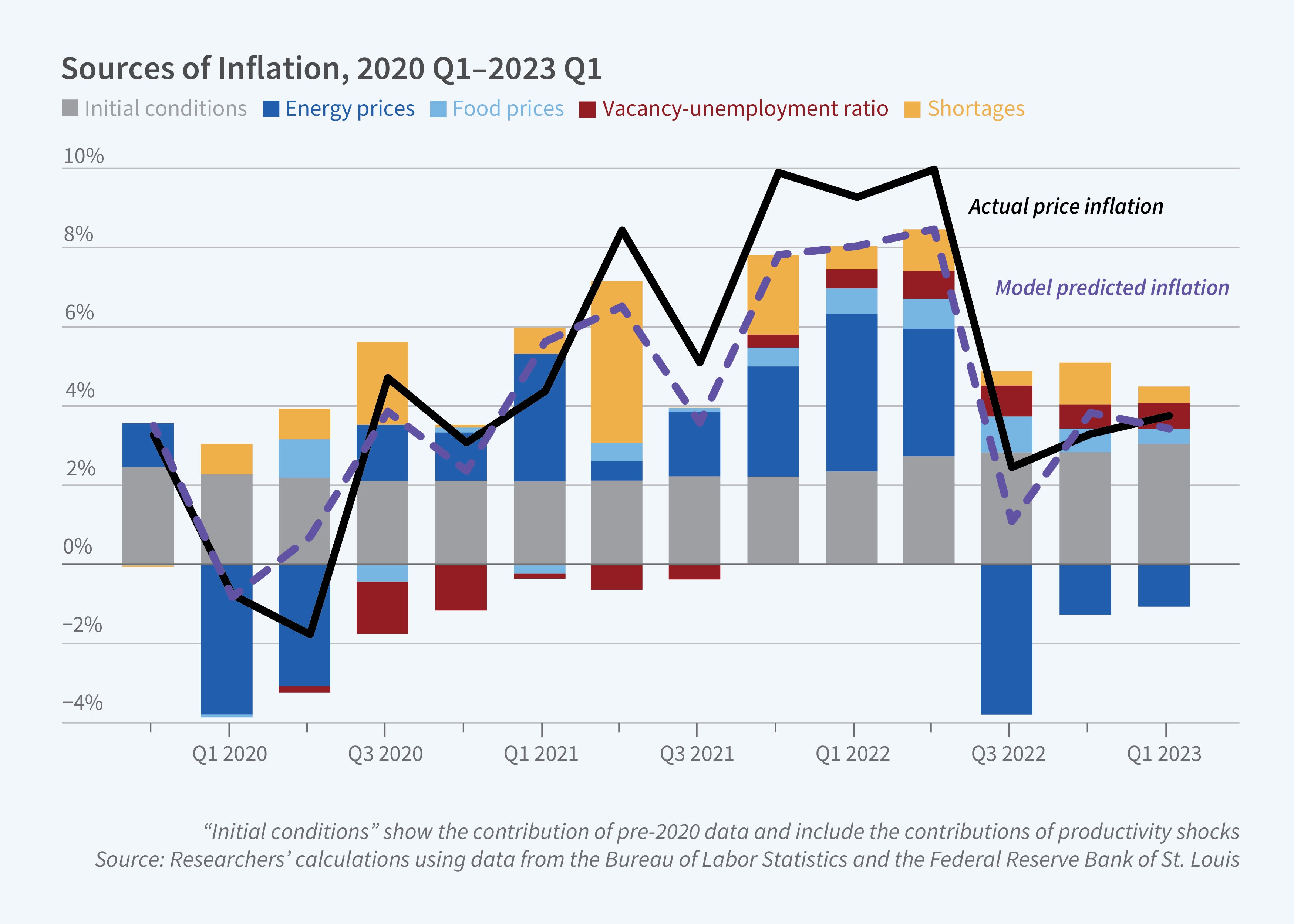

The relative importance of these factors, and others, in contributing to US inflation that began in mid-2021 is an open question. In What Caused the US Pandemic-Era Inflation? (NBER Working Paper 31417), Olivier J. Blanchard and Ben S. Bernanke study the historical comovement of wages, prices, and inflation expectations in an effort to measure the relative contributions of the sources of the recent US inflation shock. They estimate the relationships between price inflation, wage inflation, commodity price shocks, shortages, and labor market tightness over the period from 1990 to the start of the pandemic, and then use their estimates to simulate the inflationary effects of the various shocks that buffeted the US economy from the beginning of 2020 to early 2023.

The researchers find that energy prices, food prices, and price spikes due to shortages were the dominant drivers of inflation in its early stages, although the second-round effects of these factors, directly through their effects on other prices or indirectly through higher inflation expectations and wage bargaining, were limited. The contribution of tight labor markets to inflation was initially quite modest. But as product market shocks have faded, the tight labor market and the resulting persistence in nominal wage increases have become the main factors behind wage and price inflation. This source of inflation is unlikely to recede without macroeconomic policy intervention.

— Leonardo Vasquez

Researchers

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

Inflation is no longer at a 40-year high but still stubborn: These are the items still expensive

Advertiser disclosure.

We are an independent, advertising-supported comparison service. Our goal is to help you make smarter financial decisions by providing you with interactive tools and financial calculators, publishing original and objective content, by enabling you to conduct research and compare information for free - so that you can make financial decisions with confidence.

Bankrate has partnerships with issuers including, but not limited to, American Express, Bank of America, Capital One, Chase, Citi and Discover.

How We Make Money

The offers that appear on this site are from companies that compensate us. This compensation may impact how and where products appear on this site, including, for example, the order in which they may appear within the listing categories, except where prohibited by law for our mortgage, home equity and other home lending products. But this compensation does not influence the information we publish, or the reviews that you see on this site. We do not include the universe of companies or financial offers that may be available to you.

- Share this article on Facebook Facebook

- Share this article on Twitter Twitter

- Share this article on LinkedIn Linkedin

- Share this article via email Email

- • Federal Reserve

- • Personal finance

- • Budgeting

The Bankrate promise

At Bankrate we strive to help you make smarter financial decisions. While we adhere to strict editorial integrity , this post may contain references to products from our partners. Here's an explanation for how we make money .

Founded in 1976, Bankrate has a long track record of helping people make smart financial choices. We’ve maintained this reputation for over four decades by demystifying the financial decision-making process and giving people confidence in which actions to take next.

Bankrate follows a strict editorial policy , so you can trust that we’re putting your interests first. All of our content is authored by highly qualified professionals and edited by subject matter experts , who ensure everything we publish is objective, accurate and trustworthy.

Our banking reporters and editors focus on the points consumers care about most — the best banks, latest rates, different types of accounts, money-saving tips and more — so you can feel confident as you’re managing your money.

Editorial integrity

Bankrate follows a strict editorial policy , so you can trust that we’re putting your interests first. Our award-winning editors and reporters create honest and accurate content to help you make the right financial decisions. Here is a list of our banking partners .

Key Principles

We value your trust. Our mission is to provide readers with accurate and unbiased information, and we have editorial standards in place to ensure that happens. Our editors and reporters thoroughly fact-check editorial content to ensure the information you’re reading is accurate. We maintain a firewall between our advertisers and our editorial team. Our editorial team does not receive direct compensation from our advertisers.

Editorial Independence

Bankrate’s editorial team writes on behalf of YOU — the reader. Our goal is to give you the best advice to help you make smart personal finance decisions. We follow strict guidelines to ensure that our editorial content is not influenced by advertisers. Our editorial team receives no direct compensation from advertisers, and our content is thoroughly fact-checked to ensure accuracy. So, whether you’re reading an article or a review, you can trust that you’re getting credible and dependable information.

How we make money

You have money questions. Bankrate has answers. Our experts have been helping you master your money for over four decades. We continually strive to provide consumers with the expert advice and tools needed to succeed throughout life’s financial journey.

Bankrate follows a strict editorial policy , so you can trust that our content is honest and accurate. Our award-winning editors and reporters create honest and accurate content to help you make the right financial decisions. The content created by our editorial staff is objective, factual, and not influenced by our advertisers.

We’re transparent about how we are able to bring quality content, competitive rates, and useful tools to you by explaining how we make money.

Bankrate.com is an independent, advertising-supported publisher and comparison service. We are compensated in exchange for placement of sponsored products and services, or by you clicking on certain links posted on our site. Therefore, this compensation may impact how, where and in what order products appear within listing categories, except where prohibited by law for our mortgage, home equity and other home lending products. Other factors, such as our own proprietary website rules and whether a product is offered in your area or at your self-selected credit score range, can also impact how and where products appear on this site. While we strive to provide a wide range of offers, Bankrate does not include information about every financial or credit product or service.

Key takeaways

- The current inflation rate is 3.5%, with shelter, motor vehicle insurance and energy the current main contributors.

- Prices have risen 20.4% since the pandemic-induced recession began in February 2020, with just 5% of the nearly 400 items the Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks cheaper today.

- The Federal Reserve is closely monitoring inflation and has raised interest rates to combat it, but the U.S. economy remains resilient — threatening to keep inflation elevated.

Prices aren’t rising as quickly as they once were, but the worst inflation crisis in 40 years is far from over.

Since February 2020, consumer prices have jumped 20.4 percent, a Bankrate analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows. That’s well above the historic average for a four-year period. For comparison, inflation rose 18.9 percent in the 2010s, 28.4 percent in the 2000s and 32.4 percent in the 1990s.

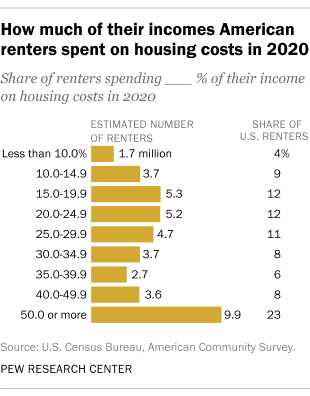

A little bit of inflation is good for consumers. The economy keeps growing and businesses continue expanding, hiring workers and bumping up their pay along the way. Too much inflation, however, feels akin to taking a pay cut . The post-pandemic price burst means Americans would need about $1,200 to buy the same goods and services that cost $1,000 when the coronavirus-induced recession occurred. High inflation has consequences beyond just affordability, complicating saving for emergencies or investing for retirement .

The latest reports from the consumer price index (CPI) — the ultimate scorecard for consumers wishing to track how much the goods and services they frequently buy are rising — have dashed experts’ hopes for a quicker-than-expected return to “goldilocks” inflation. Economists in Bankrate’s latest quarterly poll say there’s a risk that inflation could stay hot until 2026 .

Looking for the latest information on consumer prices? Here’s a round-up of where inflation is improving — and where it’s still remaining stubborn.

The lack of progress toward 2 percent inflation is now a trend. — Greg McBride, Bankrate Chief Financial Analyst

Highlights of the latest statistics on inflation

- Overall inflation in March 2024: 3.5%, up from 3.2% in February

- Core prices (excluding food and energy): 3.8%, no improvement from last month’s 3.8% increase

- Food away from home (dining out at restaurants): 4.2%, down from 4.5%

- Food at home (groceries): 1.2%, up from 1%

- Services: 5.3%, up from 5% in February

- Energy: 2.1%, up from -1.7% in February

- Gasoline: 1.3%, up from -3.9% in February

- Motor vehicle insurance: up 22.2%, up from 20.6% in February

- New vehicles: -0.1%, down from 0.4% in February

- Used cars and trucks: -1.9%, down from -1.4% in February

What is the current inflation rate?

Inflation rose 3.5 percent in March from a year ago, the sharpest increase since September, the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics report showed. Excluding the volatile food and energy categories, so-called core prices held at 3.8 percent in March.

The latest figures suggest that slowing inflation is now losing some momentum. Inflation hasn’t improved for 10 months, when the annual rate hit 3 percent for the first time in June 2023. Core prices have also begun moving sideways, barely improving from the 4 percent level they officially reached four months ago in October.

Taken together, however, inflation is still well below its peak in June 2022, when it smashed 9.1 percent.

Prices that are rising the most

Of the nearly 400 items that BLS tracks, more than 2 in 3 (or 67 percent) increased in price between March 2023 and 2024. Almost half (49 percent) picked up speed from the prior 12-month period and rose faster than the Fed’s preferred 2 percent target (45 percent).

According to BLS, these are the prices that increased most over the past year:

Month-over-month price changes can also give consumers a more real-time look at the prices that have recently been popping, though consumers should take seasonal variations into account. BLS doesn’t seasonally adjust all of its items, and year-over-year inflation rates can better smooth out those variations.

According to BLS, these are the prices that increased most over the past month:

Why is inflation so high right now?

Consumers might look at the massive 30.1 percent increase in video discs and other media — the largest increase ever — and wonder why the overall inflation rate is just 3.5 percent. To put it simply, the Bureau of Labor Statistics assigns weights to each individual good or service it tracks, based on how prevalent it’s considered to be in a consumer’s monthly budget.

Currently, the largest contributors to inflation are shelter, motor vehicle insurance and energy.

- Taken together, energy and shelter were responsible for more than half of the monthly 0.4 percent increase in prices between February and March 2024, BLS said.

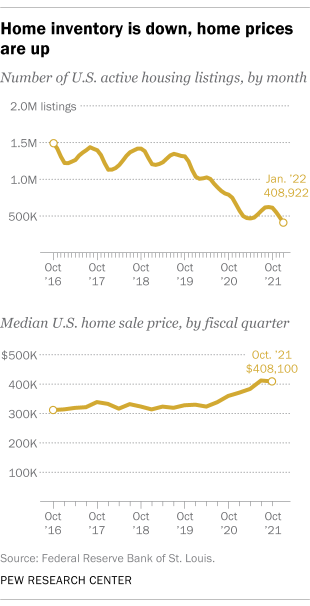

- Over the past 12 months, shelter has accounted for more than half (56 percent) of the increase in prices. Put another way, if shelter had remained stable, prices would have only risen 1.5 percent from a year ago.

- Over the past 12 months, inflation would have risen just 2.9 percent had motor vehicle insurance costs remained stable.

The drivers of inflation have changed dramatically since the initial post-pandemic price burst. When price pressures peaked in June 2022, shelter was driving just 20 percent of the annual increase in prices. But as consumers emerged from lockdowns with massive pent-up demand at the same time as global supply shortages, energy was driving about a third (32 percent) of inflation, while food prices were driving 15 percent of inflation.

The changing drivers of inflation have evolved as much as the U.S. economy. Supply chains have untangled since the pandemic, helping take the pressure off of goods inflation. However, services such as rent, insurance and even the price of dining out can take months, if not years, to fluctuate — depending on what’s happening with labor costs and consumer spending.

To combat inflation, officials on the Federal Reserve have lifted borrowing costs from a rock-bottom level of near-zero percent to a 23-year high of 5.25-5.5 percent. Yet, the U.S. economy has remained surprisingly resilient, underpinned by a job market with an unemployment rate below 4 percent for the longest stretch of time since the 1960s.

“Rapidly rising housing costs continue to be the economy’s Achilles’ heel and the inventory crunch brought about by mortgage rate hikes isn’t exactly helping,” says Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter. “While we are seeing deflation in core goods prices, it is simply not enough to offset the enduring heat in services inflation.”

Post-pandemic inflation: What’s risen the most and what’s gotten cheaper

Of the nearly 400 items BLS tracks, just 19 (or roughly 5 percent) are cheaper today than they were pre-pandemic. More than 2 in 5 (45 percent) of those items rose at a faster clip than overall inflation.

To be sure, prices are expected to rise in the healthiest of economies — though only gradually, at a goalpost of around 2 percent a year.

According to BLS, these are the top 10 items that have jumped the most in price since the pandemic:

Meanwhile, the items that have dropped in price the most since the pandemic are primarily goods and electronics — largely thanks to improving supply chains.

Inflation breakdown by product category

Looking for an easy analysis of how inflation is impacting the key items in your budget? Here’s what Bankrate found.

Over the past 12 months, gasoline prices have risen 1.3 percent, well below the peak jump of 59.9 percent in June 2022 but still the first year-over-year increase since September 2023. Those recent gains have been evident at the pump: Fuel prices have increased across all 50 states over the past month, AAA data shows. Taken together, prices at the pump are still 34.8 percent more expensive than they were in February 2020.

Grocery prices (formally known as food at home) rose 1.2 percent from a year ago and are still 25.2 percent more expensive than they were before the pandemic, BLS data indicates. At their peak, grocery prices soared 13.5 percent in July 2022 from a year ago.

Of the major shopping categories:

- Meats: up 3.4 percent over the past year and 26.5 percent since February 2020

- Fish and seafood: down 2.6 percent from a year ago but still up 16 percent since the start of the pandemic-induced recession

- Dairy: down 1.9 percent over the past year but still 18.9 percent more expensive since the pandemic

- Fruits and vegetables: up 2 percent over the past year but 18.2 percent more expensive than before the pandemic

- Sugar and sweets: up 4.3 percent from a year ago and 28 percent since the pandemic

Meanwhile, the price of dining out (formally known as full service meals and snacks) jumped 4.2 percent from a year ago, capping off a 25.8 percent increase since the pandemic.

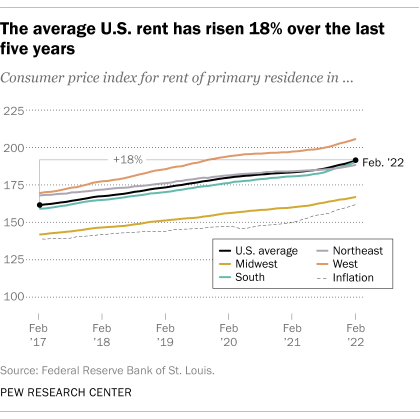

Rent has become one of the most costly categories of a consumer’s budget.

Rent of primary residence in March jumped 5.7 percent from a year ago, BLS data shows. To be sure, rent prices aren’t rising as quickly as they once were, at one point surging 8.8 percent over a 12-month period back in March and April 2023. Yet, Americans who’ve had to sign new leases since the outbreak are feeling the pinch: Rent is up 22.6 percent since the pandemic.

Real-time measures show that rents aren’t rising as quickly as they were at the height of post-pandemic lockdowns, though a sharper slowdown hasn’t yet been reflected in the official BLS monthly report. One reason could be because of lags, even longer than usual for shelter prices as leases and housing agreements take longer to roll over from the previous year. Another could simply be because homes have stayed pricey , keeping more renters on the sidelines than usual.

Inflation hasn’t just made the prices of key household essentials — but the costs of vacations and travel, too. Airline ticket prices, for example, once soared as much as 43 percent from a year ago in September 2022.

Those prices are finally starting to level off, though a resurgence in fuel and energy costs could jeopardize that slowdown in prices.

- Airfares: down 7.1 percent from a year ago and 0.3 percent cheaper since February 2020

- Car and truck rental: down 8.8 percent from a year ago but up 24.5 percent since the pandemic

- Hotels and motels (lodging away from home): down 2.4 percent from last year but 13.8 percent more expensive than before the pandemic

Car ownership

Owning a car has been especially pricey since the pandemic, from the cost of the car itself and the interest rates that finance it to the repair and insurance costs required for upkeep.Making car inflation hard to escape, the majority of households (roughly 92 percent) owned at least one car in 2022, according to the Census Bureau.

- Motor vehicle insurance: up 22.2 percent from a year ago and 43.5 percent since the start of the pandemic in 2020

- Vehicle repair: up 11.6 percent from a year ago and 45.7 percent since February 2020

- New vehicles: down 0.1 percent since March 2023 but still 20.7 percent more expensive since February 2020

- Used vehicles: down 1.9 percent since March 2023 but 30.2 percent more expensive

- Leased vehicles: up 1.1 percent from a year ago and 39.4 percent since the start of the pandemic

The different methods of measuring inflation: PCE versus CPI

- Overall inflation in March 2024: 2.7% from a year ago, up from the 2.5% pace in February

- Core prices (excluding food and energy): 2.8% from a year ago, matching last month’s 2.8% annual pace

- Food prices: up 1.5% from a year ago, up from 1.3% in February

- Services: up 4% from a year ago, up slightly from 3.9% in February

- Energy: up 2.6% from a year ago after dropping 2.3% in February

Fed policymakers look at the full picture of economic data when setting interest rates. But officially, they prefer a different measure to see whether they’re succeeding at controlling inflation: the Department of Commerce’s personal consumption expenditures (PCE) index.

But that preference has been keeping Fed watchers on their toes. Lately, the PCE index has been indicating slower inflation, with overall prices just half a percentage point above the Fed’s target — compared to a hotter 1.5 percentage points as shown with CPI.

Those variations have always been afoot. Mainly, they’re because of methodology differences . For starters, PCE takes consumers’ substitutions into account (for example, one family’s decision to buy fish over meat for one month because it’s cheaper).

But another key difference is to blame lately. Both agencies estimate an item’s relative importance differently, with BLS’ gauge giving the most weight to the category of inflation that’s coincidentally been the hottest: shelter.

For Fed officials, the story remains largely the same: Inflation is slowing but still stubbornly above their 2 percent goalpost. Yet, when officials do decide to change policy — including cutting interest rates — the variations could make the decision trickier. Fed officials don’t want to risk cutting interest rates too soon, for fear that it could stoke even higher inflation if it causes demand to rise again.

“While this report is not what the Fed wants to see, most of the inflationary gains are concentrated in housing and car insurance, sectors that are expected to calm down eventually,” says Tuan Nguyen, U.S. economist at RSM. “It’s reasonable to expect that inflation could start going down again in the next month or two.”

Takeaways for consumers

For consumers, the message is clear: Inflation has cooled dramatically since peaking in the summer of 2022, though it remains undefeated. The ultimate question now is whether the U.S. economy’s resilience is keeping inflation elevated . If it is, the Fed might need to slow the financial system down more to finish the job, ultimately risking consumers’ paychecks and employment if it dents the robust job market.

- Expect higher-for-longer rates from the Fed: Fed Chair Jerome Powell has said that officials need to cut interest rates long before prices hit 2 percent on an annual basis. If they don’t, they risk slowing the economy down too much for too long. Yet, officials say they need more confidence that inflation is retreating back to their target, meaning interest rates are likely to remain high — keeping borrowing costs expensive but savings yields lucrative.

- Comparison shop as much as you can : Consumers know to compare offers from multiple lenders before locking in a loan. Why not the same for the items you buy on a regular basis? Comparison shopping can help make sure you’re buying the cheapest product on the market. Compare prices at multiple retailers, see if any stores offer price match and craft a budget. If a product or ingredient pushes your spending goal over the edge, consider swapping it out for something else.

- Use the personal finance tools at your disposal: Finding the right credit card that helps you earn rewards on the purchases you were already going to make can be another way to pad up your wallet. Just be sure you’re not carrying a balance. A 20.75 percent interest rate will never outweigh the cash back .

- Save for emergencies and find the right account: Historically, investing in the markets has been the best way to beat inflation, but today’s high-rate era means savers can find a market-like return without any of the risk . Stash your cash in a high-yield account or add a longer-term CD to your portfolio, so you can lock in these elevated yields for the long haul.

See how all items BLS regularly tracks have changed over time

Methodology.

Related Articles

National average money market account rates for April 2024

What is the average interest rate for savings accounts?

Current CD rates for April 2024

How to use Zelle: A beginner’s guide to digital payments

Fed’s new inflation targeting policy seeks to maintain well-anchored inflation expectations

April 06, 2021

The 2007–09 global financial crisis packed an economic punch that led the Federal Reserve to its first-ever monetary policy framework review. The Fed concluded this effort by announcing a major change in its monetary policy strategy—moving from what has been described as flexible “inflation targeting” to flexible “average inflation targeting.”

The change reflects lessons learned over time and from other countries and represents an evolution of the framework to better adapt monetary policy to the challenges of a low-inflation, low-interest-rate environment.

Monetary policy evolution

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered its policy rate—the federal funds rate—to near zero in response to the financial crisis. It also decided to keep an “ample” level of reserves in the banking system, changing the way monetary policy guides the federal funds rate . The Fed also expanded its toolkit and communication practices with balance-sheet policies supported by forward guidance. Forward guidance refers to a commitment by the central bank on the future path of the policy rate.

The FOMC issued its first statement of longer-run goals and policy strategy in 2012 and subsequently amended it in 2019. That statement included the Fed’s first explicit commitment to an inflation rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE). That strategy is often referred to as flexible inflation targeting.

The changing U.S. economy

The Fed’s most recent (2019–20) review of its monetary policy framework (strategy, policy tools and communication practices) was motivated by growing awareness of structural transformations of the economy, including diminished sensitivity of inflation to resource slack.

This is not just a U.S. phenomenon; countries around the world have had similar experiences. Recent research suggests the downward drift in longer-term inflation expectations and the disinflationary pressures arising from diminishing pricing power and globalization have been important factors holding down inflation.

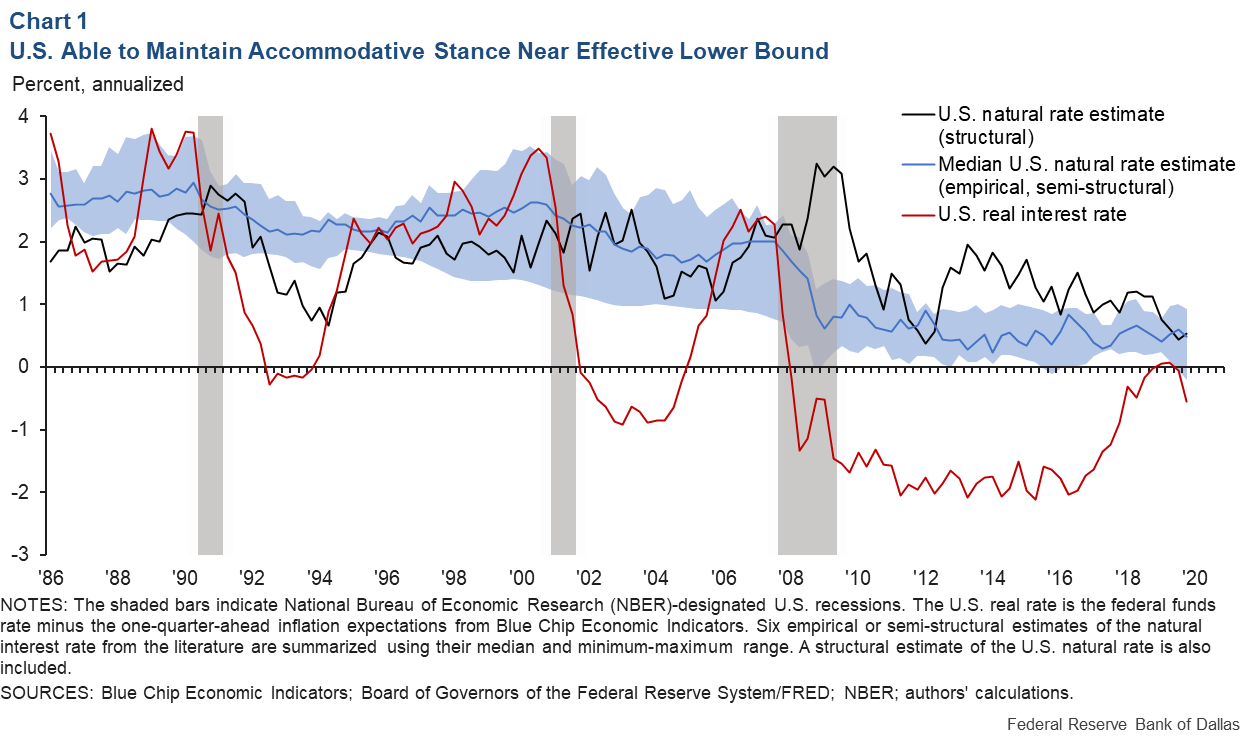

Downloadable chart | Chart data

The decline in the natural rate is a worldwide phenomenon resulting from population aging, slowing productivity growth and globalization.

A decline in the natural rate reduces the space to stimulate the U.S. economy through cuts in the federal funds rate, leaving the Fed more reliant on other policy tools such as balance sheet policies and forward guidance. The likelihood of being constrained by the effective lower bound—that is, when interest rates cannot fall below zero—is greater in low-interest-rate environments.

The Fed’s strategy change, acknowledging a new environment

Fed Chair Jerome Powell announced the more significant changes resulting from the Fed’s monetary policy framework review on Aug. 27, 2020.

The statement of longer-run goals and policy strategy explicitly acknowledges the challenges posed by the proximity of interest rates to the effective lower bound. By reducing the Fed’s scope to support the economy through interest rate cuts, the lower bound increases downward risks to employment and inflation. The statement also highlights that the Fed is prepared to use its full range of tools to achieve its dual-mandate objectives—stable prices and maximum sustainable employment.

Notably, the Fed changed its language on inflation, replacing its 2 percent inflation target commitment, and instead said it will “[seek] to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time.”

This change is a substantial departure from the previous flexible inflation-targeting regime. Monetary policy under inflation targeting was symmetric—the Fed would equally respond to overshooting and undershooting of the target. The Fed lets “bygones be bygones,” since it does not attempt to make up for past inflation deviations from target.

By comparison, average inflation targeting means that policymakers would consider those deviations and can allow inflation to modestly and temporarily run above the target to make up for past shortfalls, or vice versa .

How monetary policy could change

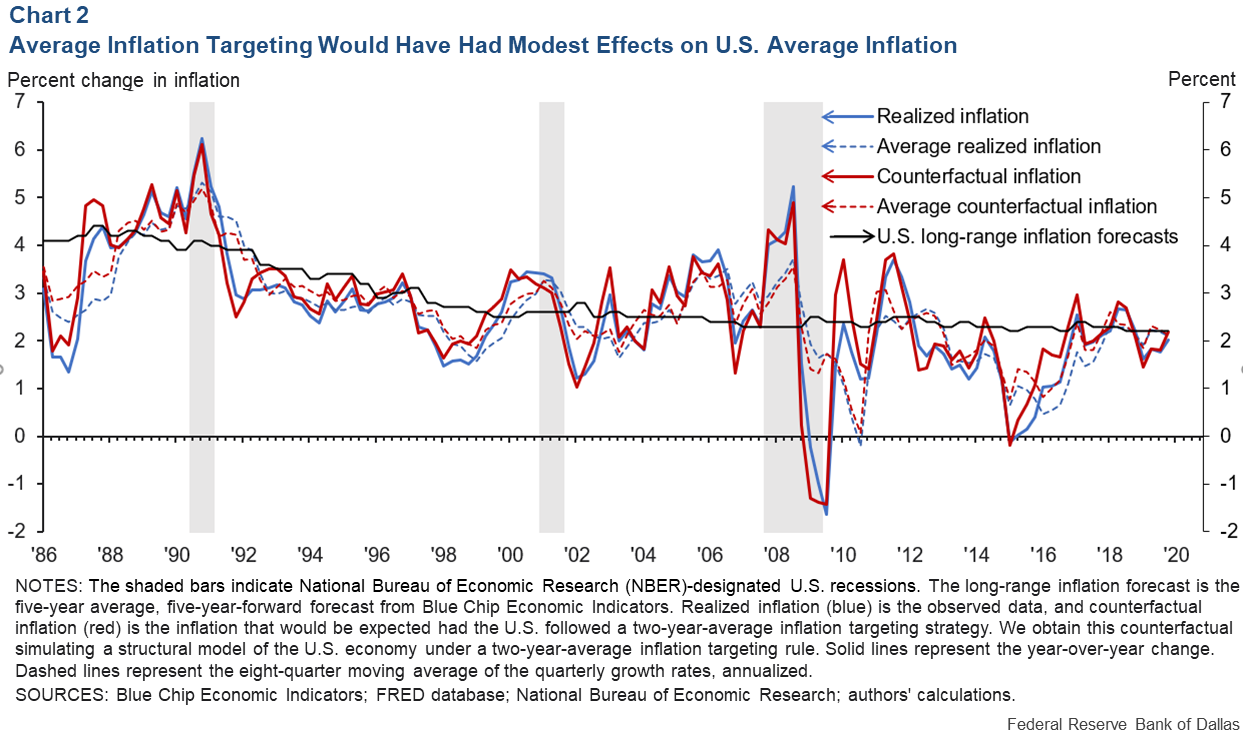

Based on an estimated medium-scale structural model of the U.S. and global economies , we explore how inflation would have behaved had the Federal Reserve adopted a regime of flexible average inflation targeting from 1986 (following a period of high U.S. inflation) to 2019 ( Chart 2 ).

The behavior of households and firms is modeled at the individual level, with agents fully informed and rational. In our counterfactual scenario—in which policymakers react to two-year-average inflation rather than to contemporaneous inflation alone—key structural parameters on preferences and technology remain unchanged at their estimated values. We assume the economy is hit with the same sequence of domestic and foreign shocks (including monetary ones).

Our counterfactual analysis suggests that, if long-run inflation expectations had remained as observed in the data, the cyclical part of U.S. inflation would have been only 0.1 percentage points higher on average under average inflation targeting than what occurred under the previous monetary policy regime.

This finding does not explicitly consider the intent of policymakers. Monetary policy implementation could also have been different (perhaps even more aggressive at providing accommodation) under the average inflation targeting regime.

Staying well-anchored around long-run expectations is arguably an important rationale for average inflation targeting. We also do not explicitly consider that if long-run inflation expectations had firmed up in this counterfactual, it would have likely resulted in higher overall realized inflation.

Why ‘Average Inflation Targeting’ Then?

When aggregate demand shocks drive the economy to the effective lower bound, theory suggests that the cumulative effect also puts sustained downward pressure on inflation. The concern is that below-target inflation outcomes may become entrenched in lower, below-target inflation expectations. This would pose a challenge to the Fed in meeting its dual-mandate goals.

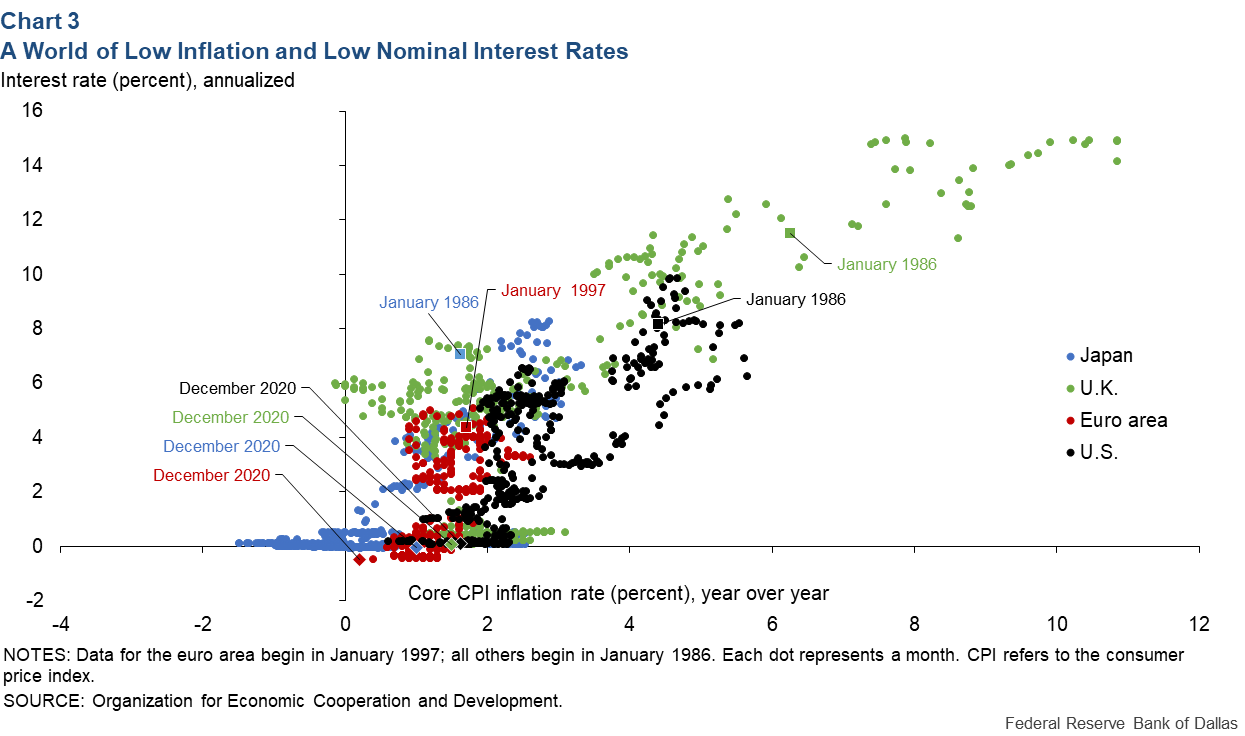

There might be a number of plausible long-run outcomes for the economy. One is consistent with monetary policy implemented in the U.S. since the ‘80s, after inflation was tamed and inflation expectations became anchored around the Fed’s target. Another possible outcome is the low-nominal-interest-rate, deflationary regime observed in Japan during the same period ( Chart 3 ). Average inflation targeting allows policy space for the Fed to “make up” for lost inflation to sustain the former equilibrium.

By adopting average inflation targeting, the Fed is communicating that 2 percent is not a ceiling for inflation and that it may let inflation exceed 2 percent modestly and temporarily to make up for past low inflation. The key aim of this policy shift is anchoring inflation expectations.

Monetary Policy Continues to Evolve

The Fed’s evolving understanding of the economy and its reassessment of the natural rate of interest have led to arguably the most significant policy change since 2012. The new strategy of flexible average inflation targeting provides more flexibility to pursue the central bank’s maximum employment and price stability mandates in the current low-interest-rate environment.

It also reinforces the importance of keeping U.S. inflation expectations well-anchored. However, as our understanding of monetary policy transmission and the economy evolves, the Fed will become challenged anew and will continue adapting to achieve broad-based growth consistent with its long-run inflation target.

About the Authors

Enrique Martínez-García

Martínez-García is a senior research economist and advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Jarod Coulter

Coulter is a research analyst in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Valerie Grossman

Grossman is a researcher and the web content manager in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Related Articles

Welcome to FRED, Federal Reserve Economic Data. Your trusted source for economic data since 1991.

Trending Search Terms:

Browse data by:.

FRED Will Remove Wilshire Index Data on June 3, 2024

FRED & DDP Partnership

Women are the majority of the college-educated workforce

State revenue from death and gift taxes

More Popular Series

Release Calendar

Subscribe to the FRED newsletter

Advertisement

Supported by

The Fed’s Favorite Inflation Index Remained Stubborn in March

Hopes for substantial cuts in interest rates are fading as inflation shows more staying power than expected.

- Share full article

By Jeanna Smialek

The Federal Reserve’s most closely watched inflation measure remained stubborn in March, the latest evidence that price increases are not fading as quickly as policymakers would like, and another reason that interest rates may stay higher for longer.

Investors came into 2024 hopeful that Fed officials would cut rates substantially this year, but those hopes have been fading as inflation has shown much more staying power than expected. Wall Street increasingly sees lower rates coming much later in the year, if the Fed manages to cut them at all.

The latest Personal Consumption Expenditures index reading could keep the Fed on a cautious path as it considers when to lower borrowing costs.

The overall inflation index rose by 2.7 percent in the year through March, up from 2.5 percent in February and slightly more than economists had expected.

Fed officials typically keep a close eye on a measure that strips out food and fuel costs, both of which are volatile, to get a sense of the underlying inflation trend. That “core” measure increased by 2.8 percent on an annual basis, in line with its February reading.

Inflation was coming down steadily in late 2023, but in recent months progress has stalled. That has left policymakers reassessing how soon and how much they might be able to cut borrowing costs. Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, signaled last week that central bankers were not seeing the progress that they were hoping to witness before lowering rates.

If inflation continues to hover above the Fed’s 2 percent target, it could prod officials to keep interest rates high for an extended time. Policymakers raised interest rates to 5.33 percent between March 2022 and last summer, and have held them at that level since. They think that is high enough to eventually weigh on the economy — in economics parlance, it is “restrictive.”

But some economists have begun to question just how restrictive it is, because growth has remained solid and hiring rapid even after months of relatively high rates.

Data released Friday showed that momentum continued in March: Consumer spending rose 0.8 percent for the second consecutive month, ahead of forecasters’ expectations. Americans’ after-tax income continued to rise faster than prices.

Given the momentum, some economists are wondering if Fed officials could begin to contemplate raising rates again.

Fed governor Michelle Bowman has already said that while it was not her “base line outlook” she saw “the risk that at a future meeting we may need to increase the policy rate further.”

For now, though, markets have simply pushed back their expectations for rate cuts. Investors are betting that the Fed might make its first move in September or later, based on market pricing , though a growing share think that it may not manage to cut rates at all this year.

Jeanna Smialek covers the Federal Reserve and the economy for The Times from Washington. More about Jeanna Smialek

A Global Database of Inflation

April 2024 version -- data updated to 2023

The World Bank’s Prospects Group has constructed a global database of inflation. The database covers up to 209 countries over the period 1970-2023, and includes six measures of inflation in three frequencies (annual, quarterly, and monthly):

- Headline consumer price index (CPI) inflation

- Food CPI inflation

- Energy CPI inflation

- Core CPI inflation

- Producer price index inflation

- Gross domestic product deflator

The database also provides aggregate inflation for global, advanced-economy, and emerging market and developing economies as well as measures of global commodity prices.

The research paper , by Jongrim Ha, M. Ayhan Kose, and Franziska Ohnsorge, provides detailed information on the database and shows three potential applications of the database: the evolution of global inflation since 1970, the behavior of inflation during global recessions, and the role of common factors in explaining movements in different measures of inflation.

Data Download

The inflation data are available for download in Excel and Stata . The commodity price data are available here . The database is updated twice a year.

When using the data, please cite the following paper as the data source: Ha, Jongrim, M. Ayhan Kose, and Franziska Ohnsorge (2023). "One-Stop Source: A Global Database of Inflation." Journal of International Money and Finance 137 (October): 102896.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in the working paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank and its affiliated organizations.

For more information, please contact Jongrim Ha ([email protected]).

Inflation data (Excel)

Inflation data (Stata, zip)

Commodity price data (zip)

Other Studies on Inflation

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

The Inflation Plateau

Prices have been rising faster than expected for the past three months. What’s going on?

Just a few months ago, America seemed to have licked the post-pandemic inflation surge for good. Then, in January, prices rose faster than expected. Probably just a blip. The same thing happened in February. Strange, but likely not a big deal. Then March’s inflation report came in hot as well. Okay—is it time to panic?

The short answer is no. According to the most widely used measure, core inflation (the metric that policy makers pay close attention to because it excludes volatile prices such as food and energy) is stuck at about 4 percent, double the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. But that’s a long way from the crisis of 2022, when core inflation peaked at nearly 7 percent and the price of almost everything was going up dangerously fast. Instead, we seem to be facing a last-mile problem: Inflation has mostly normalized, but wringing out the final few percentage points in a handful of categories is proving harder than expected. There are two conflicting views of what exactly is going on, each with drastically different implications for how the Federal Reserve should respond. One camp worries that the Fed could lose control of inflation all over again; the other fears that the central bank will—whoops— unnecessarily bring the U.S. economy to its knees.

The “vanishing inflation” view is that today’s still-rising prices reflect a combination of statistical quirks and pandemic ripple effects that will almost surely resolve on their own. This camp points out that basically all of the current excess inflation stems from auto insurance and housing. The auto-insurance story is straightforward: Car prices spiked in 2021 and 2022, and when cars get more expensive, so does insuring them. Car inflation yesterday leads to car-insurance inflation today. That’s frustrating for drivers right now, but it carries a silver lining. Given that car inflation has fallen dramatically over the past year, it should be only a matter of time before insurance prices stabilize as well.

Annie Lowrey: Inflation is your fault

Housing, which made up a full two-thirds of excess inflation in March, is a bit more complicated. You might think that housing inflation would be calculated simply by looking at the prices of new homes or apartments. But for the majority of Americans who already own their home, it is calculated using a measure known as “owners’ equivalent rent.” Government statisticians try to determine how much money homeowners would reasonably charge for rent by looking at what people in similar homes are paying. This way of calculating housing prices has all kinds of flaws. One issue is that inflation data are calculated monthly, but most renters have one- or two-year leases, which means the official numbers usually lag the real housing market by a year or more. The housing market has cooled off considerably in the past year and a half, but the inflation data are still reflecting the much-hotter market of early 2023 or late 2022. Sooner or later, they too should fall. “The excess inflation we have left is in a few esoteric areas that reflect past price increases,” Ernie Tedeschi, the director of economics at Yale’s Budget Lab, told me. “I’m not too worried about inflation taking off again.”

The “hot wages” camp tells a very different story. Its members note that even as price increases appeared to be settling back down at the beginning of 2024, wages were still growing much faster than they did before the pandemic. When wages are rising quickly, many employers, especially those in labor-intensive service industries, raise prices to cover higher salary costs. That may show up in the data in different ways—maybe it’s groceries one month, maybe airfares or vehicle-repair costs another month—but the point is that as long as wages are hot, prices will be as well. “The increase in inflation over the last three months is higher than anything we saw from 1992 to 2019,” Jason Furman, the former director of Barack Obama’s Council of Economic advisers, told me. “It’s hard to say that’s just some fluke in the data.”

Adherents of the “vanishing inflation” idea don’t deny the importance of wages in driving up prices; instead, they point to alternative measures that show wage growth closer to pre-pandemic levels. They also emphasize the fact that corporate profits are higher today than they were in 2019, implying that wages have more room to grow without necessarily pushing up prices.

Although this dispute may sound technical, it will inform one of the most pivotal decisions the Federal Reserve has made in decades. Last year, the central bank raised interest rates to their highest levels since 2001, where they have remained even as inflation has fallen dramatically. Raising interest rates makes money more expensive for businesses and consumers to borrow and, thus, to spend, which is thought to reduce inflation but can also raise unemployment. This leaves the Fed with a tough choice to make: Should it keep rates high and risk suffocating the best labor market in decades, or begin cutting rates and risk inflation taking off again?

If you believe that inflation is above all the product of strong wage growth, then cutting interest rates prematurely could cause prices to rise even more. This is the view the Fed appears to hold. “Right now, given the strength of the labor market and progress on inflation so far, it’s appropriate to allow restrictive policy further time to work,” Fed Chair Jerome Powell said in a Q&A session following the release of March’s inflation data. Translation: The economy is still too hot, and we aren’t cutting interest rates any time soon.

Michael Powell: What the upper-middle class left doesn’t get about inflation

If, however, you believe that the last mile of inflation is a product of statistical lags, keeping interest rates high makes little sense. In fact, high interest rates may paradoxically be pushing inflation higher than it otherwise would be. Many homeowners, for instance, have responded to spiking interest rates by staying put to preserve the cheap mortgages they secured when rates were lower (why give up a 3 percent mortgage rate for a 7 percent one?). This “lock-in effect” has restricted the supply of available homes, which drives up the prices.

High rates may also be partly responsible for auto-insurance costs. Insurance companies often invest their customers’ premium payments in safe assets, such as government bonds. When interest rates rose, however, the value of government bonds fell dramatically, leaving insurers with huge losses on their balance sheets. As The New York Times ’s Talmon Joseph Smith reports , one reason auto-insurance companies have raised their premiums is to help cover those losses. In other words, in the two categories where inflation has been the most persistent, interest rates may be propping up the exact high prices that they are supposed to be lowering.

The Fed’s “wait and see” approach comes with other risks as well. Already, high rates have jacked up the costs of major life purchases, made a dysfunctional housing market even more so, and triggered a banking crisis. They haven’t made a dent in America’s booming labor market—yet. But the longer rates stay high, the greater the chance that the economy begins to buckle under the pressure. Granted, Powell has stated that if unemployment began to rise, the Fed would be willing to cut rates. But lower borrowing costs won’t translate into higher spending overnight. It could take months, even years, for them to have their full effect. A lot of people could lose their jobs in the meantime.

Given where inflation seemed to be headed at the beginning of this year, the fact that the Federal Reserve finds itself in this position at all is frustrating. But given where prices were 18 months ago, it is something of a miracle. Back then, the Fed believed it would be forced to choose between a 1970s-style inflation crisis or a painful recession; today it is deciding between slightly higher-than-typical inflation or a somewhat-less-stellar economy. That doesn’t make the central bank’s decision any easier, but it should perhaps make the rest of us a bit less stressed about it.

Support for this project was provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

We, the voters

Why experts say inflation is relatively low but voters feel differently.

Ailsa Chang

A report from Purdue University found that a majority of consumers expect food prices to keep rising in the coming year, which could sour voter sentiment. Scott Olson/Getty Images hide caption

A report from Purdue University found that a majority of consumers expect food prices to keep rising in the coming year, which could sour voter sentiment.

A lot goes into planning a personal budget – and the price of food and how it fluctuates with inflation can be a big part of that.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, food prices rose by 25 percent from 2019 to 2023 . And a report from Purdue University found that a majority of consumers expect food prices to keep rising in the coming year .

Are food prices as bad as consumers think?

All Things Considered host Ailsa Chang spoke with Joseph Balagtas, a professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University and the lead author of that report.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.