Factors impacting acceptance of e-learning in India: learners' perspective

Asian Association of Open Universities Journal

ISSN : 2414-6994

Article publication date: 21 July 2022

Issue publication date: 5 October 2022

This study aims to identify the most significant factors that influence acceptance of e-learning in India. As e-learning has gained popularity in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to be one of the most sustainable methods of education, it is pertinent to examine learners' perception towards its acceptance. There is limited literature available on this subject in India, especially factoring in impact of the pandemic.

Design/methodology/approach

This study empirically analyses data of 331 adult e-learners in India, who have enrolled for one of the following e-learning formats: higher education, private coaching, test preparation, re-skilling and online certifications, corporate training and hobby and language-related learning. Their perception is examined on the basis of a model developed using the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model. Data are analysed through structural equation modelling using SPSS and AMOS statistical tools.

The result of the study shows that Infrastructure Dependability, Effectiveness of Design and Content of Courses and Student's Competency with Computers are the top three factors impacting e-learning acceptance in India.

Research limitations/implications

This study makes several theoretical contributions. Additionally, research findings and recommendations will facilitate education providers, corporates in the education industry and policymakers to focus on the significant areas for enhancing the acceptance of e-learning.

Originality/value

This study identifies and confirms important factors that influence e-learning acceptance and suggests opportunities for further in-depth research and analysis.

- Acceptance of e-learning

- Factors influencing acceptance of e-learning

- Factors impacting acceptance of e-learning

- E-Learning acceptance

- Acceptance of online learning

Duggal, S. (2022), "Factors impacting acceptance of e-learning in India: learners' perspective", Asian Association of Open Universities Journal , Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 101-119. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-01-2022-0010

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Sanya Duggal

Published in the Asian Association of Open Universities Journal . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/ legalcode

1. Introduction

Education is a US$6 tn industry worldwide, as per Barclays Research and HolonIQ, an education intelligence provider. It is expected to grow to $7.3 tn by 2025 and to $10 tn by 2030 ( Barclays and HolonIQ, 2020 ). The segment of the education industry enabled by technology is called “education technology” or “EdTech” ( Barclays and HolonIQ, 2020 ).

Technology enables various services and solutions across levels in the education space. It encompasses learning, teaching, assessment, credentialing and certification, student data management and research management ( HolonIQ, 2021 ). However, only 3.1% of the total education expenditure worldwide is currently on digital aspects, which is expected to grow to 5.5% by the year 2025 ( HolonIQ, 2020 ). HolonIQ also estimates EdTech to become a US $404 Bn market by 2025 from US$183 bn in 2019 worldwide ( HolonIQ, 2020 ).

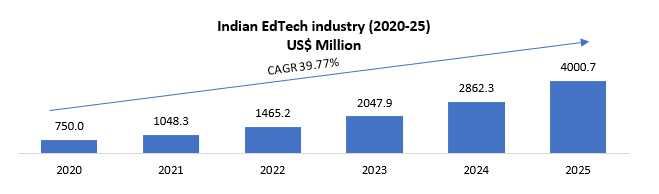

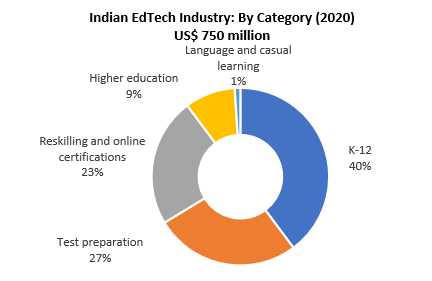

As of 2020, education in India is a US$117 Bn market with 360 Mn learners ( PGA Labs, 2020 ). It is expected to grow 2x to US$225 Bn by 2025 ( PGA Labs, 2020 ). The adoption of technology has been on a consistent rise in India's education sector in the last 10 years ( KPMG, 2017 ). Inc42 DataLabs estimated the Indian EdTech market to reach US$2.8 Bn in 2020. Aided by strong COVID-19 tailwinds, the report estimates its growth to be US$10.4 Bn by 2025 ( Inc42 Data Labs, 2020 ).

Online learning or e-learning is the largest segment of EdTech, attracting its maximum paid customers ( Nasscom, 2018 ). E-learning refers to learning provided via electronic means. It enables the availability of the learning process and educational curriculum outside the traditional classrooms (HolonIQ, 2021) . E-learning offers many benefits such as convenience, saving of time and costs, timely updates, flexibility and easy monitoring of learners' progress. Further, the online learning audience is vast and varied, ranging from school children to retired or working professionals ( KPMG, 2017 ).

E-learning promotes self-education, and with the availability of small and smart schools, it works well. Students are not restricted to gain knowledge within their domestic boundaries; they can now attend sessions across the nation with the help of the Internet. E-learning ensures many benefits such as the following: (1) Irrespective of the distance, it ensures communication between the parties with the help of a dialogues room, digital classroom and emails. (2) 24-h availability of the resources leads to no fixed time frame as teachers are available even after working hours. (3) Even after personal responsibilities, as per the time availability, everyone can learn ( Abed, 2019 ).

There is a change in sense of equality as well; earlier in traditional classrooms, it was observed that weak students hesitated in asking questions and did not share their opinions, but in e-learning, they have a platform where they can send their queries via email and can discuss one-to-one as well ( Sharp, 2000 ). Education is the basic and very strong beam behind the success of any nation ( Baiyere and Li, 2016 ). After COVID-19, the education sector suffered a lot because of the closing and suspension of schools. The sudden suspension left no choice for the education industry and made it vulnerable too. In these times, teachers and educators started trying and using various e-platforms to educate everyone. In this situation, information and communication technology offered edge over the traditional methods with e-learning and virtual universities ( Alsoud and Harasis, 2021 ). COVID-19 created a crisis in the education system and left it with a number of challenges. Challenge of one-to-one education, challenge of virtual education and many more challenges were faced by the world ( Edelhauser and Lupu-Dima, 2020 ).

The e-learning space in India hit an inflection point as the COVID-19 pandemic set in during H1 of 2020 ( Inc42 Data Labs, 2020 ). The pandemic compelled educational institutes and learners to use e-learning for continuing education. In this prevailing situation, it becomes more important to understand the perception of learners towards acceptance of e-learning and evaluate factors that can influence its acceptance positively. There is limited literature on this topic, especially research that (1) factors in the impact of the pandemic and (2) is greater in audience scope and includes adult learners.

Therefore, there is a need to identify the significant factors that affect the acceptance of e-learning systems and consequentially prioritise their effectiveness to improve the overall e-learning outcomes. In India, there are a few research papers on similar topics, especially on e-learning carried out by universities, but it is necessary to increase the scope to include other adult learners and thus support the success of the e-learning ecosystem. This study aims to evaluate factors that affect acceptance of e-learning and is targeted to users in the higher education space, test preparers over the age of 20 years, working professionals investing in re-skilling and online certifications and corporate training and users over the age of 20 years for hobby and language-related learning.

To summarise, the main objectives of this research are to (1) identify the impact of factors that influence the acceptance of e-learning systems in India for adult learners and (2) suggest ways to improve students' e-learning acceptance in India. This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the concepts and covers the extant literature, Section 3 has the research model and lays the hypothesis, Section 4 covers the research method, Section 5 provides the results of this research, Section 6 shares the discussion and Section 7 provides conclusions.

2. Relevant studies

This section examines the meaning of e-learning and past studies on the subject. It also explores the factors that affect the acceptance of e-learning. Based on these findings, a research model and hypotheses are developed in Section 3 .

2.1 E-learning

E-learning is a training or learning procedure that is created, managed and delivered using different information technology (IT) tools which can be local or global ( Masie, 2016 ). E-learning is defined as a learning methodology that is dependent on Internet communications and facilitates interaction between students and lecturers through suitably designed content and resources ( Resta and Patru, 2010 ).

Along the lines of Nguyen et al. (2014) , this research takes e-learning to be a learning method based on the Internet that is conducted through a formal educational program and is managed by a learning management system (LMS). It is meant to ensure collaboration and interaction and thus satisfy the learning demands of any learners irrespective of time and place. Pham and Huynh (2017) noted that there is a difference in e-learning in developed and developing countries. In developing countries like India, e-learning has been applied in the recent few years and proper technology infrastructure to support education is still underway.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has emphasised the change in learning from traditional teaching to online teaching. Now, most schools and universities have provided a hybrid system of teaching so that those who can’t come to school because of physical disabilities can now attend schools and higher education. In many governments of foreign countries like Georgia, the Education Ministry of Georgia has provided Microsoft Teams to all the public schools and also started TV schools (The Government of Georgia, 2020) .

2.2 Past studies on e-learning

The National Center for Education Statistics has reported an increment in the requirement for e-learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As per Biswas et al. (2020) , there has been a surge in the research on understanding students' perceptions and expectations of e-learning. Studies also reveal that learners' perceptions and acceptance are affected by a number of factors.

However, there are very limited studies that focus on the factors affecting acceptance of e-learning in India during the COVID-19 timeframe, especially the ones that cover adult learners, i.e., learners over the age of 18 years.

2.3 Factors affecting acceptance of e-learning

E-learning is essentially an information system; thus, the acceptance of e-learning can be measured just like the acceptance of any other information system or technology. Acceptance of a technology system can also be factored as the success of that system, and thus, this study will consider all factors that contribute to the acceptance or success of a technology system.

According to Seddon (1997) , there are three aspects that evaluate an information system's success. These are (1) quality of a system as measured by timeliness, relevance and accuracy; (2) perceptual measurements such as user satisfaction and perceived usefulness and (3) perceived benefits that can range from organisational to individual to social.

DeLone and McLean (2003) added service quality as an additional contributing factor of the information system success model to the above-listed factors.

Pham and Huynh (2017) measured the success of an e-learning system through independent variables covering perceived usefulness, computer self-efficacy, email interaction, face-to-face interaction, ease of use and social presence.

There are two more models that can be used to understand the acceptance of a technology system: Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Davis et al. (1989) developed the TAM using Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975) Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). The TAM explains that there are two main factors affecting the acceptance of information systems: perceived easiness in use and perceived usefulness. This was further explained by Venkatesh and Davis (2000) who suggested the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM2), an extension to explore the determinants of perceived easiness of use and perceived usefulness.

Venkatesh et al. (2003) proposed the UTAUT to reason the factors affecting user behaviour towards acceptance of information systems. The UTAUT proposes that four factors affect acceptance: effort expectancy, performance expectancy, facilitating conditions and social influence. Venkatesh et al. (2012) developed UTAUT2 by adding three new factors to these four: exchange value, convenience and habit.

Over the years, the UTAUT has been used as the foundational theory to explore the acceptance attributes of e-learning. Incorporating the context of e-learning systems, the UTAUT focuses on the following four factors:

2.3.1 Performance expectancy

Acceptance of e-learning is influenced by the design and content of the courses and the collaboration of students, as per Laily et al. (2013) and Selim (2007) . These could be considered as the two factors within performance expectancy.

2.3.2 Effort expectancy

This factor can be interpreted as the ease of use of e-learning systems by e-learners. As per Laily et al. (2013) , the computer competency of students affects acceptance of e-learning systems.

2.3.3 Social influence

As per Selim (2007) , lecturers/teachers play an important role in the acceptance of e-learning as they are in the capacity of advising students, implementing tests, organising events online and engaging students. This is representative of the factor of social influence.

2.3.4 Facilitating conditions

Conditions such as dependable infrastructure, platform/provider/university support and accessibility of Internet affect e-learning, as per Selim (2007) . These crucial factors can be considered as facilitating conditions for e-learning acceptance.

3. Research model and hypotheses

3.1 research model.

On the basis of the discussion mentioned earlier, the UTAUT model is selected as the foundational theory for this study as the UTAUT covers a majority of factors that affect the acceptance of e-learning. The UTAUT is the “unified theory of acceptance and use of technology” model that was formulated by Venkatesh et al. in "User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view” (2003). This model aims to explain a user's intentions and dependencies to use an information system and the ensuing usage behaviour. It is based on four key constructs, first being performance expectancy, second effort expectancy, third social influence and fourth facilitating conditions (see Figure 1 ).

For the proposed research model, seven constructs, being directly based on these 4 dimensions of the UTAUT model, are drawn in this study. The seven defined constructs are as follows: Effectiveness of Instructor or Lecturer, Student's Competency with Computers, Student's Collaboration Interests, Effectiveness of Design and Content of Courses, Accessibility of Essential Resources, Infrastructure Dependability and Provider Support Received.

It can be observed, as mentioned in Section 2 , that constructs “Student's Collaboration Interests” and “Effectiveness of Design and Content of Courses” can be associated to performance expectancy; construct “Student's Competency with Computers” is related to effort expectancy; “Effectiveness of Instructor or Lecturer” is associated to social influence and “Accessibility of Essential Resources”, “Infrastructure Dependability” and “Provider Support Received” tie into facilitating conditions (see Figure 2 ).

3.2 Hypothesis statements

The seven hypothesis statements are developed from the seven factors obtained through the review and analysis so far.

3.2.1 Instructor

There is a significant impact of the instructor on e-learning acceptance of students.

3.2.2 Computer competency

There is a significant impact of computer competency on e-learning acceptance of students.

3.2.3 Collaboration interests

There is a significant impact of collaboration of students on the e-learning acceptance of students.

3.2.4 Design and content of courses

There is a significant impact of content and design of the courses on the e-learning acceptance of students.

3.2.5 Accessibility of essential resources

There is a significant impact of accessibility of essential resources on the e-learning acceptance of students.

3.2.6 Infrastructure dependability

There is a significant impact of infrastructure dependability on the e-learning acceptance of students.

3.2.7 Platform/provider/institution support

There is a significant impact of platform/provider support on the e-learning acceptance of students.

4.1 Methodology

Step 1 : Preliminary Quantitative Research. The first version of the questionnaire was circulated to 40 participants who had prior experience with e-learning. These data were collected, and reliability was tested using Cronbach's alpha test and exploratory factor analysis. On the basis of the discrepancies observed in this set, minor modifications were made to the survey questionnaire. The final survey was then circulated to students and working professionals to capture responses.

Step 2 : Final Quantitative Research. The final questionnaire was sent to students at higher education institutes and to the professionals across different age groups, domains and industries. The only requirement was that the survey participant must have undertaken an e-learning course in the last one year. The data collected were analysed through Cronbach's alpha analysis, exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modelling (SEM).

4.2 Measurement scales

A 5-point Likert scale was used to solicit responses from the participants to gather their inputs to each variable. The variables rolled up to 8 constructs – 7 were factors impacting e-learning acceptance, and the 8th construct gauged the acceptance of e-learning by participants. The first construct, Effectiveness of Instructor, had 6 variables developed from Soong et al. (2001) and Volery and Lord (2000) . The second construct, Student's Competency with Computers, drew 5 variables from Soong et al. (2001) . The third construct, Student's Collaboration Interests, had 5 variables again from Soong et al. (2001) . The fourth construct, Effectiveness of Design and Content of Courses, had 5 scales from Soong et al. (2001) . The fifth construct, Accessibility of Essential Resources, had 6 items from Volery and Lord (2000) . The sixth construct, Infrastructure Dependability, developed 4 items from Volery and Lord (2000) . The seventh construct, Provider Support Received, had 6 items based on Selim (2007) . The eight construct, What Do You Feel About E-Learning, measured e-learning acceptance and was developed on 7 items from Selim (2007) and Nehari and Bender (1978) .

Here are the variables used for each construct (see Table 1 ).

4.3 Data gathering and analysis

According to the research by Hoang and Chu (2008) , the minimum sample size for analysis of data must be higher than 5 times the observed variables. In this study, 44 variables were observed, developed from 8 underlying factors. Thus, the minimum sample size requirement was 220 (44 × 5). In order to get sufficient data, the survey was shared with over 1,000 participants and the aim was to collect about 300 responses.

5. Results and observations

After the data were collected, it was analysed with the help of Cronbach's alpha analysis, exploratory factor analysis, CFA and SEM. To this effect, the statistical tools IBM SPSS and IBM SPSS AMOS were used.

5.1 Overview of data collected

Data for this research were collected through the random sampling method. The survey questionnaire was circulated via email, social networking websites and university forums and in person also. A total of 388 responses were received from the survey. Out of these, there were 331 valid responses. Invalid responses comprised of respondents who had not taken any e-learning course, who gave the same answer to every question, etc.

The following is a demographic overview of the data received ( N = 331) (see Table 2 ).

5.2 Cronbach's alpha analysis

Cronbach’s alpha measures the reliability of a set of data. It determines the internal consistency by checking how closely items are related to a construct. A scale can be considered reliable if its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ( α ) is greater than 0.6. Also, as Nguyen and Nguyen (2011) defined, the item correlation within a group must be greater than 0.3 and if it is not so, the item must be removed.

On analysing the results from this survey, it was found that the Cronbach’s alpha of all constructs was greater than 0.6. However, there were 4 items that had to be removed owing to correlations lesser than 0.3. Here is a summary (see Table 3 ).

5.3 Exploratory factor analysis

Exploratory factor analysis is a multivariate technique that is used to identify underlying relationships between a set of data variables. The first step within this is the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett test, which indicates the suitability of data for purposes of structure detection. The KMO coefficient in these data was 0.930, indicating that exploratory factor analysis could be used since the coefficient was >0.5.

It showed that hypothesis of correlation within the variables must be rejected as Sig. = 0.000. Further, with Eigenvalue ≥ 1, with the “principal component analysis” method, using “Promax” rotation along with Kaiser normalisation, there were 7 factors extracted from the 40 measured variables. There were no variables with low loading (<0.3) factor coefficients, and thus, no variables had to be removed at this stage. This output could be used next for CFA (see Figures 3 and 4 ).

5.4 Confirmatory factor analysis

CMIN – Chi-square

CMIN/df – Chi-square/degree of freedom

GFI – Goodness of fit index

CFI – Comparative fit index

TLI – Tucker–Lewis Index

RMSEA – Root mean square error approximation

According to Nguyen (2013) , for a model to be considered fit as per market data, the values of TLI, GFI and CFI must be ≥ 0.9, RMSEA ≤ 0.08 and CMIN/df ≤ 3.

Initially as the estimates are calculated, TLI = 0.861, GFI = 0.758, CFI = 0.872, RMSEA = 0.073 and CMIN/df = 2.771, which clearly did not meet the criteria. In the next iterations, variables are removed one by one based on variables with low weights as per the standardized regression weights table. In this order, the following variables were removed: AER4, AER6, Outcome 6, SCC1, Outcome 7, ELI2, Outcome 3, ID3, ELI1, ELI6, AER2, PSR1, PSR2, PSR6 and ECD1. Finally, the following values were estimated: CMIN = 430.083, CMIN/df = 1.741, GFI = 0.905, CFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.958 and RMSEA = 0.047.

This determined that the model could be fit to the survey data. The final CFA result, as created in AMOS software, was as follows (see Figure 5 ).

5.5 Structural equation model analysis

SEM is a multivariate statistical technique that is used to determine structural relationships between latent constructs and measured variables. SEM analysis is based on CFA. As the determined model was fit for survey data, the next step here was to build the structural relationship between the variables.

Here is the finalised SEM result, as presented in AMOS (see Figure 6 ).

Analysing the text output of this diagram, the following values are noted that are to be used to accept/reject the hypothesis of this study.

The P -value is considered to be a piece of evidence against the null hypothesis, and a p -value less than 0.05 (ideally ≤0.05) is statistically significant, leading to the null hypothesis being rejected. To that effect, only one hypothesis from the observed 7 is rejected (H07-PSR, rest 6 are accepted) (see Table 4 ).

6. Discussion

This analysis showed that Infrastructure Dependability (0.217), the Effectiveness of Design and Content of Courses (0.159), Student's Competency with Computers (0.059), Student's Collaboration Interests (0.057) and Effectiveness of Instructor (0.008) had a significant impact on the e-learning acceptance of students, in that order. Accessibility of essential resources (−0.035) had insignificant impact on e-learning acceptance. Provider/platform/university technical support has no impact on the acceptance of e-learning by students.

These results are quite similar to prior research by Selim (2007) and Laily et al. (2013) which had the collaboration of students, course content and IT infrastructure as the top three impact factors. However, in this study, two of these factors are the same, and collaboration of students is the differentiating factor as this study has student's competency with computers instead. From the research by Pham and Huynh (2018) , competency with computers, social presence and student collaboration was drawn as the top three factors. Again, computer competency is common in the top three factors in the current study.

E-learning in India is still at a nascent stage, and the results of this study can be explained in that context. Infrastructure dependability refers to the core technology (computer/laptop) and communications network (Internet connectivity) required for e-learning to function. Many parts of India have undependable Internet connectivity, and poor networks now and then are common in most areas of the country. Thus, dependable infrastructure is the first and foremost requirement for e-learning acceptance. Secondly, the quality and learning outcome of e-learning is driven by the content of the courses offered and the way that they are designed. Perceived good-quality content and user-friendly structuring tend to lead to higher acceptance of e-learning. Thirdly, as noted in the earlier part of the study, a vast majority of e-learning is currently driven by re-skilling and certification courses. EdTech in India has been popularised only in the last 8–10 years; thus, this re-skilling and certification learning audience is mid/late technology adopters and not digital natives. Their competency in using computers is workable and might not be extremely proficient. This explains why computer competency criteria rank in the top third.

Moving to the other two criteria, students' collaboration interests rank very close to the computer competency criteria. Students enjoy collaborating with instructors and peers over online learning, and this enhances their acceptability of the e-learning format. This coalesces with the proven fact that students have lesser inhibitions or fears when participating online vs participating in traditional formats. The last factor, the effectiveness of the instructor, points to the collaboration encouraged by the facilitator by asking questions, involving students in discussions and encouraging acceptance of e-learning. This factor ranking last could be majorly attributed to the fact that most of the e-learning designed in India presently is in recorded formats vs being live teaching. The majority of re-skilling and certification courses are pre-recorded and leave hardly any room for live discussions. The test preparation category and higher education tend to have live interactions with teachers, but the quantum of this category in overall e-learning is low.

Accessibility of essential resources has an insignificant impact on e-learning acceptance. These resources include good connectivity, satisfactory browsing speed, no bandwidth problems when browsing, easy-to-use e-learning websites, etc. These can be understood as convenience factors as opposed to necessity factors. In India, the first technology requirement is core hardware and software and a dependable network (infrastructure dependability factor), and convenience comes as secondary or not a priority. This explains why accessibility falls in the insignificant impact category.

Lastly, provider/platform/university technical support has no impact on the acceptance of e-learning by students. This factor is not at all influencing in e-learning acceptance as it is least expected/required by students. E-learning acceptance is not dependent on this criterion at all.

7. Conclusion

7.1 conclusions.

This study has reviewed past literature on the acceptance of e-learning and created a model to test the factors affecting acceptance of e-learning in India. The model used in this study was based on the UTAUT model and comprised of 7 factors covering 44 variables developed from past research.

Data were collected to understand users' behaviours regarding e-learning acceptance. From a total of 388 responses received, 331 could be analysed for the study. The data analysis was conducted with the help of Cronbach analysis, exploratory factor analysis, CFA and SEM. This was carried out with the help of tools like SPSS and AMOS.

The results of the study showed that infrastructure dependability, effectiveness of design and content of courses and students’ competency with computers were the top three factors impacting e-learning acceptance in India. Students’ collaboration interests and effectiveness of instructor also had a significant impact on the e-learning acceptance of Indian students.

7.2 Recommendations

Infrastructure Dependability . On a micro-level, different organisations can take active steps to improve the infrastructure required by their e-learners. For example, for online corporate training, companies can ensure that their employees have well-functioning laptops and proper network connectivity. In case of higher education, universities can provide laptops/tablets or other devices to students as part of the onboarding resources. Further, Shuja et al. (2019) showed that mobile platforms contribute to students’ improved academic performance. This insight can be utilised by test preparation organisations and other institutes to ensure that their e-learning content is mobile-friendly.

Effectiveness of Design and Content of Courses . Learning online is different from learning in traditional formats and requires understanding behaviours and drivers of learners. To that effect, design and content of e-courses must be updated and revised regularly. E-learning content must also be broken into smaller pieces, infused with more effective methods like videos, whiteboarding and live interactions and structured in easily consumable ways. More innovative techniques like gamification can also be introduced to improve content design effectiveness.

Student's Competency with Computers . Platforms, organisations and institutes can equip students with learning resources to improve their computer competency. They can provide the option to learn both basic and advanced computer features and skills. One example to do this could be to include a 5-min optional introduction to a new user upon enrolling in a platform. Another example could be a short virtual training to higher education students during on-boarding procedures.

Student's Collaboration Interests . Different online activities and games can be included in course content to have students interact and collaborate more. Virtual workshops can encourage group participation and presentation. An information portal or collaboration tool such as Microsoft Teams or Google Meet can be provided to students for effective participation. These activities can be scored and measured for enhanced effect.

Effectiveness of Instructor . An instructor can improve effectiveness by involving students more in classes. Instructors can encourage students to speak and participate, ask questions, conduct activities, etc. They can also improvise on the format and structure of classes to change from simply sharing presentations online to include videos, app-based games, quick quizzes, etc.

These recommendations are indicative and not exhaustive; however, their implementation can help in improving the acceptance of e-learning.

7.3 Contributions

This study makes several theoretical contributions to academia. It adds new and current dimensions to previous research on the subject, including the impact on COVID-19. The findings discovered herein can be used as premises for further research.

Additionally, this study brings out results for industry use. Research findings and recommendations covered herein will facilitate education providers, corporates in the education industry and policymakers to focus on the significant areas for enhancing the acceptance of e-learning in India.

7.4 Limitations and future research

There are a few limitations of this study, enumerated as hereunder: (1) The sample size of 331 is small and limited. (2) The data sample might be limited to urbanised populations and might not reflect the acceptance factors in rural areas or students belonging to very-low- or very-high-income groups. (3) The seven factors included for consideration in the study might not be exhaustive, and there could be potential factors (more current or innovative) not included in the study.

Thus, as with all research, there is scope for further work from this study. The small size can be expanded to allow for wider coverage of geographical area, even beyond India, or to rural populations, within India. It would be helpful to introduce other potentially impacting variables to this research for further findings. Further, each of the top impacting factors can be explored in greater detail to find potential areas of the highest impact.

The UTAUT model, adapted from Venkatesh et al . (2003)

The proposed research model

KMO and Barlett's test result

Exploratory factor analysis result

Final standardised CFA result

Final standardised structural equation model analysis result

Scale adaptation variables used in the constructs

Demographic data of survey participants

Cronbach’s alpha analysis results

Hypothesis testing results

Abed , E.K. ( 2019 ), “ Electronic learning and its benefits in education ”, EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education , Vol. 15 No. 3 , em1672 .

Alsoud , A.R. and Harasis , A.A. ( 2021 ), “ The impact of covid-19 pandemic on student's e-learning experience in Jordan ”, Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research , Vol. 16 No. 5 , pp. 1404 - 1414 .

Baiyere , A. and Li , H. ( 2016 ), “ Application of a virtual collaborative environment in a teaching case ”, in AMCIS 2016: Surfing the IT Innovation Wave - 22nd Americas Conference on Information Systems .

Baleghi-Zadeh , S. , Ayub , A.F.M. , Mahmud , R. and Daud , S.M. ( 2017 ), “ The influence of system interactivity and technical support on learning management system utilization ”, Knowledge Management and E-Learning , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 50 - 68 .

Barclays and HolonIQ ( 2020 ), “ Education technology: out with the old school ”, available at: https://www.investmentbank.barclays.com/our-insights/education-technology-out-with-the-old-school.html ( accessed 15 May 2021 ).

Benigno , V. and Trentin , G. ( 2000 ), “ The evaluation of online courses ”, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning , Vol. 16 No. 3 , pp. 259 - 270 .

Biswas , K. , Asaduzzaman , T.M. , Evans , D. , Fehrler , S. , Ramachandran , D. and Sabarwal , S. ( 2020 ), TV-Based Learning in Bangladesh: Is it Reaching Students? World Bank, Washington, DC , https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34138 .

Davis , F.D. , Bagozzi , R.P. and Warshaw , P.R. ( 1989 ), “ User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models ”, ManagementScience , Vol. 35 No. 8 , pp. 982 - 1003 .

DeLone , W.H. and McLean , E.R. ( 2003 ), “ The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update ”, Journal of Management Information Systems , Vol. 19 No. 4 , pp. 9 - 30 .

Edelhauser , E. and Lupu-Dima , L. ( 2020 ), “ Is Romania prepared for eLearning during the COVID-19 pandemic? ”, Sustainability , Vol. 12 No. 13 , p. 5438 .

Fishbein , M. and Ajzen , I. ( 1975 ), Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research , Addison-Wesley Publishing Company , Reading, MA .

Govindasamy , T. ( 2001 ), “ Successful implementation of e-learning: pedagogical considerations ”, The Internet and Higher Education , Vol. 4 Nos 3-4 , pp. 287 - 299 .

Harasim , L. , Hiltz , S.R. , Teles , L. and Turoff , M. ( 1995 ), Learning Networks: A Field Guide to Teaching and Learning Online , The MIT Press , Cambridge, MA .

Hoang , T. and Chu , N.M.N. ( 2008 ), “ Phân tích dữ liệu nghiên cứu với SPSS (tập 1 & 2) ”, HCMC: NXB. Hồng Đức .

HolonIQ ( 2020 ), “ Global EdTech market to reach $404B by 2025-16.3% CAGR ”, available at: https://www.holoniq.com/notes/global-education-technology-market-to-reach-404b-by-2025/ ( accessed 15 May 2021 ).

HolonIQ ( 2021 ), “ 2021 global learning landscape ”, available at: https://www.globallearninglandscape.org/ (accessed 16 May 2021) .

Inc42 Data Labs ( 2020 ), “ The future of education: Indian startups chase $10 Bn Edtech opportunity ”, available at: https://inc42.com/datalab/the-future-of-education-indian-startups-chase-10-bn-edtech-market/ ( accessed 16 May 2021 ).

KPMG ( 2017 ), “ Online education in India: 2021 ”, available at: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/in/pdf/2017/05/Online-Education-in-India-2021.pdf ( accessed 16 May 2021 ).

Laily , N. , Kurniawati , A. and Puspita , I.A. ( 2013 ), “ Critical success factor for e-learning implementation InstitutTeknologi Telkom bandung using structural equation modeling ”, in Paper presented at the International Conference on Information and Communication Technology , Bandung, Indonesia , 20–22 March 2013 .

Masie , E. ( 2016 ), “ E-learning definition of Masie Elliot learning center ”, available at: https://www.elearninglearning.com/masie/ ( accessed 16 May 2021 ).

MES ( 2020 ), “ Ministry of education, science, culture and sport of Georgia. ‘Ministry of education, science, culture and sport of georgiato strengthen distance learning methods’ ”, available at: https://www.mes.gov.ge/content.php?id=10271&lang=eng ( accessed 16 June 2020 ).

Nasscom ( 2018 ), “ EdTech – the advent of digital education ”, available at: https://nasscom.in/knowledge-center/publications/edtech-advent-digital-education ( accessed 16 May 2021 ).

Nehari , M. and Bender , H. ( 1978 ), “ Meaningfulness of a learning experience: a measure for educational outcomes in higher education ”, Higher Education , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 11 .

Nguyen , D.T. ( 2013 ), “ Phương pháp nghiên cứu khoa học trong kinh doanh ”, HCMC: NXB. Tài Chính .

Nguyen , D.T. and Nguyen , T.M.T. ( 2011 ), “ Nghiên cứu khoa học Marketing: Ứng dụng mô hình cấu trúc tuyến tính SEM ”, HCMC: NXB. Lao Động .

Nguyen , T.D. , Nguyen , T.M. , Pham , Q.T. and Misra , S. ( 2014 ), “ Acceptance and use of e-learning based on cloud computing: the role of consumer innovativeness ”, Lecture Notes in Computer Science , No. 8583 , pp. 159 - 174 .

Owston , R.D. ( 1997 ), “ Research news and comment: the world wide web: a Technology to enhance teaching and learning ”, Educational Researcher , Vol. 26 No. 2 , pp. 27 - 33 .

PGA Labs ( 2020 ), “ The great ‘un-lockdown’: Indian EdTech – disruptions and opportunities for the next decade ”, available at: https://www.praxisga.com/PraxisgaImages/ReportImg/pga-labs-ivca-report-the-great-un-lockdown-indian-edtech-Report-3.pdf ( accessed 16 May 2021 ).

Pham , Q. T. and Huynh , M. C. ( 2017 ), “ Impact factor on learning achievement and knowledge transfer of students through e-learning system at Bach Khoa University, Vietnam ”, Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing Networking and Informatics (ICCNI) , IEEE , doi: . https://doi.org/10.5585/iji.v6i3.235 .

Pham , Q.T. and Huynh , M.C. ( 2018 ), “ Learning achievement and knowledge transfer: the impact factor of e-learning system at Bach Khoa University, Vietnam ”, International Journal of Innovation , Vol. 6 No. 3 , pp. 194 - 206 .

Resta , P. and Patru , M. ( 2010 ), Teacher Development in an E-Learning Age: A Policy and Planning Guide , UNESCO , Paris .

Seddon , P.B. ( 1997 ), “ A respecification and extension of the DeLone and McLean model of IS success ”, Information Systems Research , Vol. 8 No. 3 , pp. 240 - 253 .

Selim , H.M. ( 2007 ), “ Critical success factors for e-learning acceptance: confirmatory factor models ”, Computers and Education , Vol. 49 No. 2 , pp. 396 - 413 .

Sharp , S. ( 2000 ), “ Internet usage in education for technology horizon in education ”, Vol. 27 No. 10 , pp. 12 - 14 .

Shuja , A. , Qureshi , I.A. , Schaeffer , D.M. and Zareen , M. ( 2019 ), “ Effect of m-learning on students' academic performance mediated by facilitation discourse and flexibility ”, Knowledge Management and E-Learning , Vol. 11 No. 2 , pp. 158 - 200 .

Soong , B.M.H. , Chan , H.C. , Chua , B.C. and Loh , K.F. ( 2001 ), “ Critical success factors for online course resources ”, Computers and Education , Vol. 36 No. 2 , pp. 101 - 120 .

Venkatesh , V. and Davis , F.D. ( 2000 ), “ A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies ”, ManagementScience , Vol. 46 No. 2 , pp. 186 - 204 .

Venkatesh , V. , Moms , M.G. , Davis , G.B. and Davis , F.D. ( 2003 ), “ User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view ”, MISQuarterly , Vol. 27 No. 3 , pp. 425 - 478 .

Venkatesh , V. , Thong , J.Y.L. and Xu , X. ( 2012 ), “ Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology ”, MIS Quarterly , Vol. 36 No. 1 , pp. 157 - 178 .

Volery , T. and Lord , D. ( 2000 ), “ Critical success factors in online education ”, The International Journal of Educational Management , Vol. 14 No. 5 , pp. 216 - 223 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Edtech Startups in India: Leveraging the New Normal

2021, Academia Letters

Related Papers

International Journal of Management Analytics (IJMA)

Chandni Somyani

This qualitative research paper aims to provide a comprehensive review of the Ed-Tech sector in India by examining its current state, identifying key trends, and exploring the factors contributing to its growth and challenges. It investigates the diverse range of educational technologies being employed, including online platforms, mobile applications, virtual classrooms, and adaptive learning systems. The research critically examines the effectiveness and impact of these technologies on teaching and learning outcomes, as well as their influence on student engagement, accessibility, and equity. This research delves into the factors driving the growth of the Ed-Tech sector in India, such as increasing smartphone penetration, improved internet connectivity, favorable government initiatives, and changing attitudes toward online learning. It also investigates the challenges faced by the sector, such as the digital divide, inadequate teacher training, concerns regarding data privacy and security, and the need for regulatory frameworks. It examines their strategies, business models, and partnerships, highlighting successful practices and lessons learned. By providing an in-depth analysis of the Ed-Tech sector in India, this research paper offers valuable insights for policymakers, educators, investors, and stakeholders in the field of education. The outcomes of the study entail to the previous literature vis Ed-Tech, helping to inform future initiatives, policies, and investments in the Indian education system

International Journal of Research -GRANTHAALAYAH

The Indian educational technology (Edtech) industry has been experiencing remarkable growth in recent years, driven by a range of factors, including increased demand, investor interest, and mergers and acquisitions. The COVID-19 pandemic has also played a significant role in accelerating the growth of the industry. With the closure of schools and universities during lockdowns, there was a surge in demand for online education solutions. In India, the growth rate of edtech firms decreased during the year 2022. An analysis of customer reviews from 2020 to 2022 are used in this article to determine why edtech firms succeed and fail.

International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET)

IJRASET Publication

The fast adoption of digital technology in the Indian educational system has resulted in a paradigm change in recent years. This research paper aims to study the changing landscape of digital education systems in India and its impact on the education industry. The paper draws on an extensive literature review and associated data analysis to provide insight into the key drivers and challenges of this paradigm shift.

INTERANTIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT

Damini Dutta

The growing and widespread use of digitalization is redefining the learning and teaching process in India. Online learning has been accelerated by growing and common use of digital technologies and the learning and teaching process has been redefined in India. The pandemic has also led to the emergence of various EdTech (Education Technology) companies in India and worldwide. Due to this reason, a lot of changes are being made in the education industry. Traditional techniques and classroom teaching and learning methods are no longer sustainable. Change in consumer demands and new economic frameworks are also making a challenge to businesses. To ensure continuity, business analysts play a vital role in EdTech organizations to adapt with regular changes.

The emergence of online education is a major contribution of the tech-savvy world that has widely played its role even before and after the pandemic. Most governments of the world have swiftly shut down the educational institutions to control the pandemic of covid-19. An incomprehensible number of states, regions and nations have closed their learning bases, with more than 91% of the world’s vast (UNESCO) neighborhood schools and universities closed. Many of the countries have implemented localized lockdowns which impacted millions of additional learners. UNESCO itself is supporting countries in their efforts to slow down the impact of institution closure particularly for more disadvantaged and vulnerable communities around the globe to facilitate the continuity of education for all through the remote learning. The World Bank is also actively functioning with the ministries of education in several countries to support their efforts to utilize various educational technologies to provide remote learning opportunities to the students during the educational institutions closure due to covid-19 pandemic. According to Dr. Howard Taylor (Executive Director, of Global Partnership to End Violence)- “The coronavirus pandemic has led to an unprecedented rise in online education in the present time.” According to UNICEF- ”Because of school closures and strict prevention measures more and more families will be relying on the technology and digital solutions to keep the children learning, entertained and connected to the outer world, but not all the children have the necessary knowledge, skills and resources to keep themselves safe with the online methods. In this situation of pandemic, learning can be moved to online and the knowledge can be transferred virtually using multimedia media tools. It’s not like that online education was not popular before but the pandemic situation made it almost necessary for every learner to shift to the online method due to the social circumstances which have aroused due to the pandemic thing.

Human Choice and Computers

mathura thapliyal

IJIRIS Journal Division

When it comes to online learning in education, the model has been pretty straightforward - up until the early 2000s education was in a classroom of students with a teacher who led the process. Physical presence was a nobrainer, and any other type of learning was questionable at best. Then the internet happened, and the rest is history. Elearning is a rapidly growing industry, the effects of which we can trace back to the 1980s and even well before that (in the form of distance learning and televised courses).Now that affordable e-learning solutions exist for both computers and internet, it only takes a good e-learning tool for education to be facilitated from virtually anywhere. Technology has advanced so much that the geographical gap is bridged with the use of tools that make you feel as if you are inside the classroom. E-learning offers the ability to share material in all kinds of formats such as videos, slideshows, word documents and PDFs. Conducting webinars (live online classes) and communicating with professors via chat and message forums is also an option available to users

Advances in Library and Information Science

Reeta Sharma

The education marketplace in India is changing dramatically, whether at school, university, or at advanced or professional course levels. In today's context, the need of the hour is to augment knowledge in every sphere to remain abreast of the competitive landscape. On the other hand, with the constant advent of ICT and rapid invasion of internet in the knowledge society, the online delivery models are becoming user friendly, interactive, and dynamic. Universities and colleges face significant constraints in raising revenue, growing classroom capacity, and increasing student enrolments; student graduation rates remain a major concern and graduating students are finding it difficult to find suitable jobs with corporations, who are demanding greater and varied skills and competencies. Online education platforms are constantly evolving as a great savior by providing suitable professional courses to the right aspirants at the right time, at the right place. This chapter is an explor...

RELATED PAPERS

Boletín del Archivo Epigráfico

Boletín del Archivo Epigráfico UCM

Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences

Lucinda Johnson

Georges BOU ABBOUD

Science Immunology

Eilat Shinar

Joaquim Ros

Pakistan Journal of Phytopathology

sobiya shafique

harry coccossis

Molecular Psychiatry

Aline Sampaio

International Journal of Computer Applications

Syed Asif Ali

Microchimica Acta

Encarnación Lorenzo

IEEE Sensors Journal

Riset, Ekonomi, Akuntansi dan Perpajakan (Rekan)

Donny Setiawan

Mulla Bozkurt

Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing

Powder Metallurgy and Metal Ceramics

Vladimir Filonenko

Rice (New York, N.Y.)

Jinming Zhang

Virchows Archiv A Pathological Anatomy and Histology

Robert Maurer

International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering

M. Rochette

Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine

Lissette delgado-cruzata

Judy Branfman

Mehmet Akif Ersoy üniversitesi fen bilimleri enstitüsü

Child Abuse & Neglect

Luise Poustka

MRS Proceedings

Daryl Ludlow

Nikolai Orlov

Springer eBooks

Myriam Laroussi

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

Is India ready to accept an EdTech-intensive system in post pandemic times? A strategic analysis of India’s “readiness” in terms of basic infrastructural support

- Research Article

- Published: 06 July 2022

- Volume 49 , pages 253–261, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Rohit Kumar Nag ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3559-2259 1

2417 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The pandemic situation has forced most of the countries to plummet toward a virtual, distant learning format in recent years since 2020. While there are certain undeniable benefits of a virtual, technology-infused setup, it essentially calls for a complete paradigm shift for a country like India which has otherwise been a practitioner of traditional classroom teaching. Despite that, the recent boom in the EdTech market in India coupled with recent government policies indicate that India is going for that paradigm shift. The key thing to note here is that an EdTech-intensive setup is not as primitive as the traditional one. Its feasibility demands more rigorous infrastructural support. This paper looks into the very basic infrastructural requirements of the system in light of a very straightforward strategic analysis model—Objective and Key Results. Under this setup, India’s readiness is measured in terms of the availability of electricity, internet, and digital equipment with the intention of making an accessible, affordable and inclusive EdTech-driven education system. Moving one step further, this paper also tallies the recent policies with the specific shortcomings of the existing system to determine whether or not India is moving on the right path to progress. In a nutshell, it is found that there is ample room for improvement in the current arrangement for implementing a large-scale EdTech-enabled system, but the progress is most certainly happening in the right direction. Recent policies make quite an argument in favor of doing away with the digital divide and building an effective and inclusive EdTech-powered education system for the future generations of citizens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools' digital capacity and transformation: A literature review

Stella Timotheou, Ourania Miliou, … Andri Ioannou

21st Century Skills

Educational experiences with Generation Z

Marcela Hernandez-de-Menendez, Carlos A. Escobar Díaz & Ruben Morales-Menendez

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In March 2020, after WHO declared the COVID-19 to be a global pandemic, the majority of the countries imposed a “lockdown” to control the spread of this virus, putting an immediate halt to all sorts of economic and social activities. This frozen state of the economies directly impacted all sectors including the education sector as well. A compulsion to find an alternative mode of operation became the burning necessity. In this situation, most of the countries adopted remotely operated distant learning as their key technique to continue the functioning of their respective education sectors. This is where it is to be vehemently pointed out that this adoption was a compulsion and this has impacted the education sector and its stakeholders in various ways depending on several preparedness and acceptance parameters. In other words, a sudden paradigm shift is expected to impact different cohorts of stakeholders differently due to the difference in their ability to accept and manage the so-called “new normal”. Therefore, at the beginning of 2022, while the world moves toward a post-COVID-19 situation, it is increasingly important to discuss the impact of these modifications on the stakeholders. In recent days, the global education scenario has leaned toward technology-infused teaching and learning which includes components of distant learning and remote operations. Specifically, after the pandemic, the world has acknowledged not only the benefits but the sheer necessity of a virtual platform in the education sector. So, instead of a temporary solution to mobilize an otherwise frozen economy, technology-infused operation is being widely thought as the future face of the global education industry.

This is where both the context and the intent of this particular paper come from. Switching to a more technology-infused system is not a minor modification, it is a gigantic leap to a completely different paradigm. Therefore, the prerequisites of this jump are expected to be different than the existing traditional classroom system which has been operating for centuries now. But in the modern setup, the method of teaching and learning is operated through Information and Communication Technology (ICT). Therefore, if ICT being the driving force of the education industry becomes the norm, the prerequisites are to be taken care of to ensure smooth and inclusive operation for optimum yield. In other words, the “readiness” factor is to be considered with utmost importance in order to make this transition a successful and productive one. This particular paper specifically focuses on the situation in India to assess its readiness in taking on an ICT-powered education system. Put differently, this paper scrolls through India’s recent moves to embrace ICT-powered education, the challenges that come with it, and policies to cater to those challenges.

Evolution of educational technology in India

In a world that is espousing ICT-powered education, India is certainly not falling behind. While it is true that India’s education sector is primarily reliant on traditional classroom teaching approach, recent developments in the Indian education sector show clear inclination toward Educational Technology (EdTech). EdTech offers a certain range of major benefits over the traditional setup. Firstly, EdTech allows customization and personalization of the curricula based on individual specific requirements and abilities. Secondly, the involvement of ICT provides ease of access to educational content for both learners and instructors. Lastly, EdTech enables distant learning and remote operations, as discussed previously, removing geographical constraints of learning (Zhang and Aslan 2021). In short, it can be said that EdTech provides a structural easement and thus accelerates the very process of delivering education. This in turn translates into economic growth through increased labor productivity, technological innovation, and implementation of newer technology (Hanushek and Woessmann 2010 ). This is where the social and economic interest begins to grow for any country to implement EdTech.

India is home to the largest population of learners belonging to the K-12 system with a reported enrollment rate (2017–2018) of approximately 250 million learners in 1.5 million schools across the nation (Statista survey data). Therefore, augmenting the education system to reap the benefits of EdTech and ICT-driven learning will surely contribute to the overall human capital formation and subsequent increment in productivity along with technological innovations in India translating into higher economic growth. Incentivized by this motive, the Indian education sector has become the cultivation ground of budding EdTech ventures in recent years. Both private sector and public sector initiatives have been seen to be growing in order to make EdTech more mainstream and an integrated part of the Indian education system.

The stepping stone of the Indian EdTech ecosystem is the launch of the EDUSAT satellite. In September 2004, a project of INR 5.5 billion was conducted by the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) in order to launch this satellite which was designed to cater exclusively to the educational requirements of the country. In specific, the satellite was used to create virtual classrooms in remote areas of India to deliver education through visualization offered by video programs telecast by the satellite (Nagaratinam 2015 ). In 2008, private players came into the field and e-learning platforms like Extramarks and Khan Academy became popular in India. With this, gradually EdTech started providing successful business models to startups in the Indian market with a vast user base. This gradual increment came to its peak and turned into an EdTech boom in 2015–2016. According to the reports published in The Economic Times and estimations done by Nasscom, in 2015 alone, nearly a thousand EdTech startups came forward to join the EdTech venture in India with an estimated funding of USD 125 million. At the same time, Indian students started joining other internationally recognized platforms as well. According to a MyStory report, in 2015, more than 1.5 million learners joined online courses on the popular US-based platform Coursera.

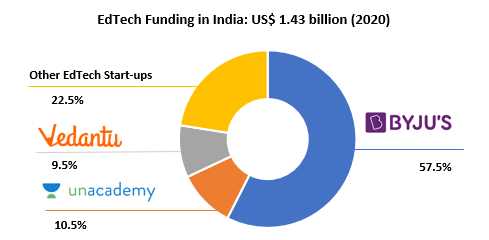

This rapid growth has only seen an upward trajectory in terms of consumption over time. Parallel to the great potential of the Indian market, the Indian education industry has become the breeding ground of many blooming and booming EdTech startups. Currently, there are approximately 4530 EdTech startups in India of which more than 400 were founded after 2019. Very recently, Indian EdTech startups have attracted nearly $4 billion worth of investments in the past two years, of which $2.2 billion was invested in 2020 alone right after the nationwide lockdown had frozen the education sector of the country. An additional $1.9 billion investment done in 2021 has added 3 more Indian names to the list of global EdTech unicorns (valued at over $1 billion). The Indian name Byju’s, existing in the world EdTech unicorns list since 2017, has now become a decacorn with a valuation of $21 billion (HolonIQ 2022 ). Unacademy, Emeritus, and upGrad are three more Indian EdTech startups that have been included in the list in August 2021, followed by Vedantu in September of that year. Very recently, another Indian startup, Lead School made it to the list in January 2022 (HolonIQ 2022 ). It is to be noted here that Byju’s is currently the world’s largest EdTech startup catering to more than 100 million registered users. These figures make it evident that India is a very lucrative market for EdTech. Additionally, the company has reported that its average user engagement time has gone up by 30% during the pandemic, average daily engagement time has gone up from 71 to 100 min (Economic Times, February 2021).

While on the one hand, the above discussion elaborates privately pursued EdTech ventures in India, like the initiative of EDUSAT, recent government policies also have a keen focus on EdTech. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 is the government’s newest arrow in the quiver to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 (to provide quality education to its citizens) which inherits the very concept of EdTech in the day to day educational operations. As already discussed, EdTech has three main components through which it enhances the educational outcomes: customizability of content, accessibility of content, and remote operations. NEP caters to all three of these components. In order to identify and acknowledge student-specific characteristics and infuse them in the learning process, NEP proposes detailed renovation and reintroduction of the e-learning platforms, e.g., SWAYAM and DIKSHA; this will make the system more “student-centered”. Providing e-content and QR code energized textbooks across the entire country through these platforms will give ease of access to educational content. Additionally, keeping in mind the paucity of digital resources, NEP also proposes to use standardized multimedia platforms i.e. radio and television to deliver educational content to the general populace. Apart from this, the top one hundred universities across the country are permitted to start online courses from 30 May 2020 itself which allows students to access courses according to their requirement and preferences without worrying about geographical barriers and the hustles of relocating.

Considering the overall scenario, it is safe to say that EdTech in India is not just an alternative for an otherwise frozen system. The gigantic growth and immaculate presence of EdTech in the veins of the current educational practice in India put forth a clear signal that EdTech is ready to become an integral part of the next generation Indian education system. This brings forth the motivation to discuss different preparedness parameters in the Indian socioeconomic framework to ensure a fruitful and inclusive operation of EdTech in the country.

In the economics of education literature, it is well established that EdTech appreciably widens the horizon of possibilities in the education sector. Most importantly, it accepts the heterogeneity among students to provide a more engaging and well-suited experience of learning (Al Hadwer et al. 2019) which was otherwise missing in the traditional “one-size-fits-all” system. Simultaneously, it is also undeniable that the infrastructural requirement of a majorly EdTech-driven system is not as primitive as the traditional classroom teaching setup. The most critical divisive factor between the two is the requirement for digital infrastructure as EdTech systems highly rely on ICT. This raises the concern to study the “readiness” factor of any country prior to implementing a large-scale EdTech transfiguration (Adam et al. 2021 ).

It is very important to note here that the readiness factor primarily consists of infrastructural preparedness and access to digital resources which in turn depend on the socioeconomic condition and governance of a particular country. These factors are very country-specific and contain irregularity. Conclusions drawn on the basis of parameters observed in one country, cannot be relevant in the case of another. Therefore, because of the irregularity of the domain, the literature is unable to come to a generalized opinion about the readiness (or feasibility in other words) of a full-scale adoption of an EdTech driven system. This question has to be answered on a country level. Specifically, in a developing country like India, the question of readiness is of utmost importance, because within-the-country variations are also to be considered in a large country like India with such a vast population. These within-the-country variations can put barriers among the population and hinder the inclusivity of the venture in totality. This paper attempts to strategically analyze the situation and assess the very basic readiness factors in the way of embracing an EdTech-intensive system in India.

Research question and methodology

With the compulsive switch to the virtual platform along with the push of NEP 2020, a permanent paradigm shift in the Indian education sector is imminent. This paper attempts to assess whether or not India is ready for that shift. The main problem with such a discussion is the subjectivity of the term “readiness” itself. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to have a precise definition of the term “readiness” in order to clearly establish the territory of the upcoming discussion as well as map the procedure of analysis step by step.

With that purpose in hand, one of the most straightforward strategic planning models, Objective and Key Results (OKR) is considered here (Grove 2015 ). OKR is all about setting a specific achievement, also known as the “objective”, and deploying a few measurable quantitative parameters of progress, also known as “key results”, which are then tracked to know how close or how far one is from their respective objective. This particular framework can be adopted quite suitably here. The first step is to identify the objective at hand. Obviously, the objective is to make India ready for an EdTech-intensive education system in post-pandemic times .

The next step is to find out the measurable quantitative parameters (i.e. the key results) to reflect the progress toward the said objective. In order to set up the key results, an approach known as the Key Performance Indicators (KPI) is used. It essentially states that there are a few crucial (measurable) performance parameters that are responsible for the overall effectiveness of the system. Here, studying the literature, one can easily say the first and foremost parameter which is responsible for making an EdTech driven system successful is the availability of the internet along with digital devices. ICT being the building block of EdTech, without internet and digital devices it is simply not possible for any EdTech system to function. The necessity for these is well documented in the literature. However, if one moves one step further, there is a more rudimentary factor to be considered—electricity! Without electricity, it is once again impossible to power up the equipment.

Therefore, electricity, internet, and availability of digital devices can be considered three primary factors which affect the performance of the EdTech system. These are quantifiable parameters as well. Simply by considering the penetration rate, a picture of progress toward the desired “readiness” can be painted. Hence, the research question boils down to the following,

Is India ready to accept an EdTech-intensive system in post-pandemic times , where readiness is measured in terms of

availability of electricity

availability of internet connectivity

availability of digital resources.

In other words, the fields of electricity, internet connectivity, and digital resource availability will be reviewed in detail to figure out how far or how close India is to attaining the desired readiness to have an effective EdTech transfiguration of the education system in the country. In this context, within-the-country variations are also pointed out to render the picture of inclusivity in the system. Additionally, this paper will also take a quick glance at the recent government policies to see if the policies are at par with the measures necessary to address any shortcomings of the current arrangement.

Implication of the key performance indicators

While the data clearly reflects a flourishing business for the EdTech hubs in India, it is important to ensure its inclusivity while discussing a nationwide application. In fact, the transition to a new paradigm affects different cohorts in different ways in conformity with their distinctive values of readiness. Therefore, it is important to include all the stakeholders across all geographic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds while deciding on the future footsteps of the Indian education system. Notwithstanding the individual preferences and capabilities and their respective effects, infrastructural constraints are to be widely discussed in this regard as well in the context of a developing country like India. This is where the aforementioned “key results” are going to come into play. To understand this wide-ranging diversity across the country, and how that affects the readiness under consideration, the situation is reviewed on the basis of those predetermined parameters: electricity, internet, and access to digital resources.

Key performance indicators

Availability of electricity.

In reference to infrastructural preparedness, the most primary technical requirement of an ICT-driven system has to be electricity. According to the World Bank Global Electrification Database, in 2019, more than 97% of Indian households have electricity added to the list of their available basic amenities. This is undoubtedly a remarkable leap forward from 88% in 2015 and 89.5% in 2016. However, the vast land of India is not so uniform to be treated as a single entity. A very basic division would tell that among the 1.2 billion population, more than 833 million reside in rural areas whereas only 377 million are urban residents (Indian Census 2011). While the situations in rural and urban India are not quite similar, on average the disparity is not that pronounced. In fact, since 2015, the electrification process in rural India has been quite successful according to the data given by the Council of Energy, Environment, and Water (CEEW) (Agrawal et al. 2020 ). The average daily supply of electricity to an urban household is 22 h compared to their rural counterparts, lagging behind only by a minuscule 2 h with an average daily supply of 20 h. However, a further division with respect to states can take one deeper into the scenario. On the one hand, despite the very successful rural electrification project, 2.4 percent of households (mostly rural) still have no electricity in their houses due to the affordability factor. This 2.4 percent of households majorly belong to the states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Bihar. Three of these states, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Bihar have been part of the ACCESS program (The Access to Clean Cooking Energy and Electricity—Survey of States) and have shown steep increment in electrification in the rural areas along with Jharkhand, Odisha, and West Bengal. Despite that, there are still people in these states who can not afford electricity. Compared to only 12.5 h daily in 2015, the average electricity availability has significantly increased to 18.5 h daily in 2020. In 2020, 73 percent of rural consumers have reported to be satisfied with the facilities related to the availability of electricity in their households which is a significant increase from only 23 percent in 2015 and 55 percent in 2018. Therefore, despite some hindrance, the overall situation in terms of availability of electricity in rural India has significantly improved after 2015. However, specific states, e.g., Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Jharkhand, and Bihar are still behind (Indian Residential Energy Survey 2020) with less than 18 h of supply in rural areas and about 20 h in urban areas which lie quite below the average line for India as a whole. In sum, it indicates that while there is some lack of consistency across all states and demographic variations of the country, the holistic picture of the entire country shows a significant improvement over the past few years. But there is definitely room for improvement. For instance, two-third of rural households and two-fifth of urban households still face abrupt power disconnection at least once a day as reported by CEEW. In a nutshell, a significant trend of improvement is evident with some space for refinement in the way of building a sustainable system.

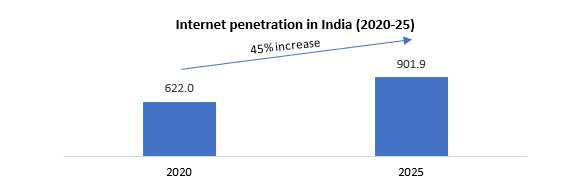

Availability of internet

In the queue, the next is access to the internet. After the introduction of the “Digital India” programme in 2015, several steps were taken in the way of revolutionizing the telecom industry in India and it has significantly increased access to the internet through mobile networks. One of the major contributions came from Jio telecom services introduced by the Reliance group in 2016. In 2021, the world’s second-largest online market (behind China) India had over 560 million internet users with a projected number of 650 million in 2023 (Statista, August 2021). It is true that this constitutes only around half of the existing population in the country. In other words, the internet penetration is only 47% in India (Keelery 2021 ). However, here as well, it is to be noted that this number was only 27% in 2015 (and about 4% in 2007), therefore, it can be thought of as quite a leap forward in the past few years. However, it is important to mention here that while the disparity among the number of internet users in rural and urban India is relatively low, there is a significant gender bias when it comes to the rural population where 58% of the users are male and the rest 42% are female (Statista 2021). Similar to electricity, a disparity is observed from state to state. While the average penetration rate in India is 40 percent, it is 68 percent in Delhi followed by Kerala at 56%. Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal belong to the bottom of the list with a slightly above 30 percent penetration rate (Statista, March 2022).

Availability of digital equipment

Availability of digital equipment has been seen to be the epicenter of the quibble in many cases during the COVID-19 lockdown in the country. In fact, many students have reportedly committed suicide after being deprived of the privilege to join online lectures due to the lack of a smartphone or similar device. Including the incidents that happened in Mysuru, Karnataka (August 2020); Satara, Maharashtra (September 2020), and Punjab (June 2020), scarcity of digital resources has surely been a major contributing factor in the loss of nearly 12,500 lives of students in 2020 alone as reported by Times of India in November 2021 (Kumar 2021 ). The data shows that the number of smartphone users in India is nearly 748 million in 2020 (Statista, September 2021) which is around 57% of the entire population. More importantly, it is to be noted here, that usually, young students do not own their own devices. For instance, a student studying in kindergarten is not expected to have his or her own device. Moreover, as per world bank reports, the per capita income of an Indian individual is USD 1927 which if calculated, turns out to be USD 160 per month. The average price of a smartphone is recorded to be USD 196 in 2020–2021 (Statista, December 2021). Therefore, affordability becomes an issue in this case, specifically for low-income groups. This establishes the fact that in terms of access to digital equipment, there is a serious disparity among people belonging to different socioeconomic backgrounds when it comes to the availability of digital resources. This is one of the major problems dreading the EdTech-driven system. Inclusivity is expected to be hindered in this case.

Recent policies: direction and effects