Behavioral Economics Research Paper Topics

This list of behavioral economics research paper topics is intended to provide students and researchers with a comprehensive guide for selecting research topics in the field of behavioral economics. The importance of choosing a pertinent and engaging topic for your research paper is paramount, and this guide is designed to facilitate this crucial process. We offer an extensive list of topics, divided into ten categories, each with ten unique ideas. Additionally, we provide expert advice on how to select a topic from this multitude and how to write a compelling research paper in behavioral economics. Lastly, we introduce iResearchNet’s professional writing services, tailored to support your academic journey and ensure success in your research endeavors.

100 Behavioral Economics Research Paper Topics

Choosing a research paper topic is a critical step in the research process. The topic you select will guide your study and influence the complexity and relevance of your work. In the field of behavioral economics, there are numerous intriguing topics that can be explored. To assist you in this process, we have compiled a comprehensive list of behavioral economics research paper topics. These topics are divided into ten categories, each offering a different perspective on behavioral economics.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- The role of heuristics in decision-making

- Prospect theory and its applications

- Time inconsistency and hyperbolic discounting

- The endowment effect and loss aversion

- Mental accounting and its implications

- The role of anchoring in economic decisions

- Framing effect in marketing strategies

- The paradox of choice: More is less

- Nudge theory in public policy

- Trust game in behavioral economics

- The role of emotions in economic decisions

- Overconfidence bias in financial markets

- Decision-making under uncertainty

- The impact of social norms on economic behavior

- The role of fairness and inequality aversion in economic decisions

- The effect of cognitive dissonance on consumer behavior

- The impact of stress on economic decisions

- The role of regret and disappointment in economic decisions

- The effect of peer influence on economic behavior

- The role of culture in economic decision-making

- The use of nudges in public policy

- The impact of behavioral economics on tax policy

- The role of behavioral economics in health policy

- Behavioral insights in environmental policy

- The influence of behavioral economics on education policy

- The role of behavioral economics in social welfare policy

- The impact of behavioral economics on retirement policy

- Behavioral economics and traffic policy

- The role of behavioral economics in energy policy

- The influence of behavioral economics on housing policy

- The role of behavioral biases in personal financial decisions

- The impact of financial literacy on economic behavior

- Behavioral economics and retirement savings

- The role of behavioral economics in credit card debt

- The impact of behavioral economics on investment decisions

- Behavioral economics and insurance decisions

- The role of behavioral economics in household budgeting

- The impact of behavioral economics on mortgage decisions

- Behavioral economics and financial planning

- The role of behavioral economics in financial education

- The role of behavioral economics in pricing strategies

- Behavioral economics and consumer choice

- The impact of behavioral economics on advertising

- Behavioral economics and product design

- The role of behavioral economics in sales strategies

- Behavioral economics and customer loyalty

- The impact of behavioral economics on branding

- Behavioral economics and e-commerce

- The role of behavioral economics in business negotiations

- Behavioral economics and corporate decision-making

- The role of behavioral economics in health behaviors

- Behavioral economics and healthcare decisions

- The impact of behavioral economics on health insurance choices

- Behavioral economics and preventive health care

- The role of behavioral economics in obesity and diet choices

- Behavioral economics and smoking cessation

- The impact of behavioral economics on medication adherence

- Behavioral economics and mental health

- The role of behavioral economics in exercise and physical activity

- Behavioral economics and alcohol consumption

- The role of behavioral economics in promoting sustainable behavior

- Behavioral economics and energy conservation

- The impact of behavioral economics on recycling behavior

- Behavioral economics and water conservation

- The role of behavioral economics in climate change mitigation

- Behavioral economics and sustainable transportation

- The impact of behavioral economics on sustainable consumption

- Behavioral economics and green investments

- The role of behavioral economics in biodiversity conservation

- Behavioral economics and waste reduction

- The role of behavioral economics in digital marketing

- Behavioral economics and online shopping behavior

- The impact of behavioral economics on social media usage

- Behavioral economics and cybersecurity

- The role of behavioral economics in technology adoption

- Behavioral economics and online privacy decisions

- The impact of behavioral economics on mobile app usage

- Behavioral economics and virtual reality

- The role of behavioral economics in video game design

- Behavioral economics and artificial intelligence

- The role of behavioral economics in educational choices

- Behavioral economics and student motivation

- The impact of behavioral economics on study habits

- Behavioral economics and school attendance

- The role of behavioral economics in academic performance

- Behavioral economics and college enrollment decisions

- The impact of behavioral economics on student loan decisions

- Behavioral economics and teacher incentives

- The role of behavioral economics in educational policy

- Behavioral economics and lifelong learning

- The role of neuroscience in behavioral economics

- Behavioral economics and inequality

- The impact of behavioral economics on economic modeling

- Behavioral economics and big data

- The role of behavioral economics in addressing social issues

- Behavioral economics and virtual currencies

- The impact of behavioral economics on behavioral change interventions

- Behavioral economics and the sharing economy

- The role of behavioral economics in understanding happiness and well-being

- Behavioral economics and the future of work

This comprehensive list of behavioral economics research paper topics provides a wide range of options for your research. Each category offers unique insights into the different aspects of behavioral economics, from fundamental concepts to future directions. Remember, the best research paper topic is one that not only interests you but also has sufficient resources for you to explore. We hope this list inspires you and aids you in your journey to write a compelling research paper in behavioral economics.

Introduction to Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics is an intriguing and dynamic field that bridges the gap between traditional economic theory and actual human behavior. It integrates insights from psychology, judgment, and decision-making into economic analysis, providing a more accurate and nuanced understanding of human behavior.

Traditional economic theory often assumes that individuals are rational agents who make decisions based on maximizing their utility. However, behavioral economics challenges this assumption, recognizing that individuals often act irrationally due to various cognitive biases and heuristics. These deviations from rationality can significantly impact economic decisions and outcomes, making behavioral economics a critical field of study.

Research papers in behavioral economics allow students to delve deeper into specific areas of interest, contributing to their personal knowledge and the broader academic community. These papers can explore a wide range of topics, from understanding the role of cognitive biases in financial decision-making to examining the impact of behavioral interventions on public policy.

The importance of behavioral economics extends beyond academia. It has real-world implications in various sectors, including policy-making, business, finance, and healthcare. By understanding the psychological underpinnings of economic decisions, we can design better products, policies, and interventions that align with actual human behavior.

How to Choose a Behavioral Economics Topic

Choosing a research topic is a critical step in the research process. The topic you select will guide your study, influence the complexity and relevance of your work, and determine how engaged you are throughout the process. In the field of behavioral economics, there are numerous intriguing topics that can be explored. Here are some expert tips to assist you in this process:

- Understanding Your Interests: The first step in choosing a research topic is to understand your interests. What areas of behavioral economics fascinate you the most? Are you interested in how behavioral economics influences policy making, or are you more intrigued by its role in personal finance or marketing? Reflecting on these questions can help you narrow down your options and choose a topic that truly engages you. Remember, research is a time-consuming process, and your interest in the topic will keep you motivated.

- Evaluating the Scope of the Topic: Once you have identified your areas of interest, the next step is to evaluate the scope of potential topics. A good research topic should be neither too broad nor too narrow. If it’s too broad, you may struggle to cover all aspects of the topic effectively. If it’s too narrow, you may have difficulty finding enough information to support your research. Try to choose a topic that is specific enough to be manageable but broad enough to have sufficient resources.

- Assessing Available Resources and Data: Before finalizing a topic, it’s important to assess the available resources and data. Are there enough academic sources, such as books, journal articles, and reports, that you can use for your research? Is there accessible data that you can analyze if your research requires it? A preliminary review of literature and data can save you from choosing a topic with limited resources.

- Considering the Relevance and Applicability of the Topic: Another important factor to consider is the relevance and applicability of the topic. Is the topic relevant to current issues in behavioral economics? Can the findings of your research be applied in real-world settings? Choosing a relevant and applicable topic can increase the impact of your research and make it more interesting for your audience.

- Seeking Advice: Don’t hesitate to seek advice from your professors, peers, or other experts in the field. They can provide valuable insights, suggest resources, and help you refine your topic. Discussing your ideas with others can also help you see different perspectives and identify potential issues that you may not have considered.

- Flexibility: Finally, be flexible. Research is a dynamic process, and it’s okay to modify your topic as you delve deeper into your study. You may discover new aspects of the topic that are more interesting or find that some aspects are too challenging to explore due to constraints. Being flexible allows you to adapt your research to these changes and ensure that your study is both feasible and engaging.

Remember, choosing a research topic is not a decision to be taken lightly. It requires careful consideration and planning. However, with these expert tips, you can navigate this process more effectively and choose a behavioral economics research paper topic that not only meets your academic requirements but also fuels your passion for learning.

How to Write a Behavioral Economics Research Paper

Writing a research paper in behavioral economics, like any other academic paper, requires careful planning, thorough research, and meticulous writing. Here are some expert tips to guide you through this process:

- Understanding the Structure of a Research Paper: A typical research paper includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion. The introduction presents your research question and its significance. The literature review provides an overview of existing research related to your topic. The methodology explains how you conducted your research. The results section presents your findings, and the discussion interprets these findings in the context of your research question. Finally, the conclusion summarizes your research and suggests areas for future research.

- Developing a Strong Thesis Statement: Your thesis statement is the central argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise, and debatable. A strong thesis statement guides your research and helps your readers understand the purpose of your paper.

- Conducting Thorough Research: Before you start writing, conduct a thorough review of the literature related to your topic. This will help you understand the current state of research in your area, identify gaps in the literature, and position your research within this context. Use academic databases to find relevant books, journal articles, and other resources. Remember to evaluate the credibility of your sources and take detailed notes to help you when writing.

- Writing and Revising Drafts: Start writing your research paper by creating an outline based on the structure of a research paper. This will help you organize your thoughts and ensure that you cover all necessary sections. Write a first draft without worrying too much about perfection. Focus on getting your ideas down first. Then, revise your draft to improve clarity, coherence, and argumentation. Make sure each paragraph has a clear topic sentence and supports your thesis statement.

- Proper Citation and Avoiding Plagiarism: Always cite your sources properly to give credit to the authors whose work you are building upon and to avoid plagiarism. Familiarize yourself with the citation style required by your institution or discipline, such as APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, or Harvard. There are many citation tools available online that can help you with this.

- Seeking Feedback: Don’t hesitate to seek feedback on your drafts from your professors, peers, or writing centers at your institution. They can provide valuable insights and help you improve your paper.

- Proofreading: Finally, proofread your paper to check for any grammatical errors, typos, or inconsistencies in formatting. A well-written, error-free paper makes a good impression on your readers and enhances the credibility of your research.

Remember, writing a research paper is a process that requires time, effort, and patience. Don’t rush through it. Take your time to understand your topic, conduct thorough research, and write carefully. With these expert tips, you can write a compelling behavioral economics research paper that contributes to your academic success and the broader field of behavioral economics.

iResearchNet’s Writing Services

In the academic journey, students often encounter challenges that may hinder their ability to produce high-quality research papers. Whether it’s a lack of time, limited understanding of the topic, or difficulties in writing, these challenges can make the process stressful and overwhelming. This is where iResearchNet’s professional writing services come in. We are committed to supporting students in their academic journey by providing top-notch writing services tailored to their unique needs.

- Expert Degree-Holding Writers: At iResearchNet, we understand the importance of quality in academic writing. That’s why we have a team of expert writers who hold degrees in various fields, including economics. Our writers are not only knowledgeable in their respective fields but also experienced in academic writing. They understand the nuances of writing research papers and are adept at producing well-structured, coherent, and insightful papers.

- Custom Written Works: We believe that every research paper is unique and should be treated as such. Our writers work closely with you to understand your specific requirements and expectations. They then craft a custom research paper that meets these requirements and reflects your understanding and perspective.

- In-Depth Research: Good research is the backbone of a compelling research paper. Our writers conduct thorough research using reliable and relevant sources to ensure that your paper is informative and credible. They are skilled at analyzing and synthesizing information, presenting complex ideas clearly, and developing strong arguments.

- Custom Formatting: Formatting is an essential aspect of academic writing that contributes to the readability and professionalism of your paper. Our writers are familiar with various formatting styles, including APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, and Harvard, and can format your paper according to your preferred style.

- Top Quality: Quality is at the heart of our services. We strive to deliver research papers that are not only well-written and well-researched but also original and plagiarism-free. Our writers adhere to high writing standards, and our quality assurance team reviews each paper to ensure it meets these standards.

- Customized Solutions: We understand that each student has unique needs and circumstances. Whether you need a research paper on a complex behavioral economics topic, assistance with a specific section of your paper, or editing and proofreading services, we can provide a solution that fits your needs.

- Flexible Pricing: We believe that professional writing services should be accessible to all students. That’s why we offer flexible pricing options that cater to different budgets. We are transparent about our pricing, and there are no hidden charges.

- Short Deadlines up to 3 hours: We understand that time is of the essence when it comes to academic assignments. Whether you need a research paper in a week or a few hours, our writers are up to the task. They are skilled at working under pressure and can deliver high-quality papers within short deadlines.

- Timely Delivery: We respect your deadlines and are committed to delivering your paper on time. Our writers start working on your paper as soon as your order is confirmed, and we keep you updated on the progress of your paper.

- 24/7 Support: We believe in providing continuous support to our clients. Our customer support team is available 24/7 to answer your questions, address your concerns, and assist you with your order.

- Absolute Privacy: We respect your privacy and are committed to protecting your personal and financial information. We have robust privacy policies and security measures in place to ensure that your information is safe.

- Easy Order Tracking: We provide an easy and transparent order tracking system that allows you to monitor the progress of your paper and communicate with your writer.

- Money Back Guarantee: Your satisfaction is our top priority. If you are not satisfied with our service, we offer a money-back guarantee.

At iResearchNet, we are committed to helping you succeed in your academic journey. We understand the challenges of writing a research paper and are here to support you every step of the way. Whether you need help choosing a topic, conducting research, writing your paper, or editing and proofreading your work, our expert writers are ready to assist you. With our professional writing services, you can focus on learning and leave the stress of writing to us. So why wait? Order a custom economics research paper from iResearchNet today and experience the difference.

Secure Your Academic Success with iResearchNet Today!

Embarking on a research paper journey can be a daunting task, especially when it comes to complex fields like behavioral economics. But remember, you don’t have to do it alone. iResearchNet is here to provide you with the support you need to produce a high-quality, insightful, and impactful research paper.

Our team of expert degree-holding writers is ready to assist you in creating a custom-written research paper that not only meets but exceeds academic standards. Whether you’re struggling with topic selection, research, writing, or formatting, we’ve got you covered. Our comprehensive services are designed to cater to your unique needs and ensure your academic success.

Don’t let the stress of writing a research paper hinder your learning experience. Take advantage of our professional writing services and focus on what truly matters – your learning and growth. With iResearchNet, you can be confident that you’re submitting a top-quality research paper that reflects your understanding and hard work.

So, are you ready to take the leap? Order a custom economics research paper on any topic from iResearchNet today. Let us help you navigate your academic journey and secure your success. Remember, your academic achievement is our top priority, and we’re committed to helping you reach your goals. Order now and experience the iResearchNet difference!

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Articles on Behavioral economics

Displaying 1 - 20 of 52 articles.

Biases against Black-sounding first names can lead to discrimination in hiring, especially when employers make decisions in a hurry − new research

Martin Abel , Bowdoin College

Just in time for back-to -school shopping: How retailers can alter customer behavior to encourage more sustainable returns

Christopher Faires , Iowa State University and Robert Overstreet , Iowa State University

Your political rivals aren’t as bad as you think – here’s how misunderstandings amplify hostility

Daniel F. Stone , Bowdoin College

Medicaid coverage is expiring for millions of Americans – but there’s a proven way to keep many of them insured

Mark Shepard , Harvard Kennedy School

Starbucks fans are steamed: The psychology behind why changes to a rewards program are stirring up anger, even though many will get grande benefits

H. Sami Karaca , Boston University and Jay L. Zagorsky , Boston University

Fundraisers who appeal to donors’ fond memories by evoking their emotions may get larger gifts – new research

Michael Kurtz , Lycoming College

Having COVID-19 or being close to others who get it may make you more charitable

Nancy R. Buchan , University of South Carolina ; Gianluca Grimalda , Kiel Institute for the World Economy , and Orgul Demet Ozturk , University of South Carolina

Microeconomics explains why people can never have enough of what they want and how that influences policies

Amitrajeet A. Batabyal , Rochester Institute of Technology

Declined invitations go over more graciously when lack of money is cited instead of lack of time – new research

Grant Donnelly , The Ohio State University and Ashley Whillans , Harvard University

Women are as likely as men to accept a gender pay gap if they benefit from it

Marlon Williams , University of Dayton

Free beer, doughnuts and a $1 million lottery – how vaccine incentives and other behavioral tools are helping the US reach herd immunity

Isabelle Brocas , USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Selfish or selfless? Human nature means you’re both

Keith Yoder , University of Chicago and Jean Decety , University of Chicago

Kids are probably more strategic about swapping Halloween candy and other stuff than you might think

Margaret Echelbarger , University of Chicago

The urge to punish is not only about revenge – unfairness can unleash it, too

Paul Deutchman , Boston College and Katherine McAuliffe , Boston College

Mandatory face masks might lull people into taking more coronavirus risks

Alex Horenstein , University of Miami and Konrad Grabiszewski , Prince Mohammad Bin Salman College (MBSC) of Business & Entrepreneurship

Why Americans are tiring of social distancing and hand-washing – 2 behavioral scientists explain

Gretchen Chapman , Carnegie Mellon University and George Loewenstein , Carnegie Mellon University

When safety measures lead to riskier behavior by more people

A company’s good deeds can make consumers think its products are safer

Valerie Good , Michigan State University

Paying all blood donors might not be worth it

Gretchen Chapman , Carnegie Mellon University

Here’s how you can be nudged to eat healthier, recycle and make better decisions every day

José Antonio Rosa , Iowa State University

Related Topics

- Behavioral science

- Behavioural economics

- Behavioural science

- New research

- Nudge theory

- Philanthropy and nonprofits

- Quick reads

- Research Brief

Top contributors

Harvard University

Associate Professor of Markets, Public Policy and Law, Boston University

PhD Candidate in Management, Columbia University

Associate Professor of Economics, University of Miami

Assistant Professor of Marketing, Northeastern University

Professor of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University

Associate Professor of Economics, Rady School of Management, University of California, San Diego

Associate Professor of Marketing, Washington University in St. Louis

Professor of Economics and Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University

Associate Professor of Economics, HEC Paris Business School

Marketing PhD Candidate, The Ohio State University

Assistant Professor of Marketing, Tilburg University

Berry Chair of New Technologies in Marketing and Professor of Marketing, The Ohio State University

Research Fellow, Harvard University

Senior lecturer, University of St Andrews

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Featured articles

- Virtual Issues

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B49 - Other

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C01 - Econometrics

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C26 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C31 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions; Social Interaction Models

- C33 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C34 - Truncated and Censored Models; Switching Regression Models

- C35 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions

- C36 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C41 - Duration Analysis; Optimal Timing Strategies

- C44 - Operations Research; Statistical Decision Theory

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- C57 - Econometrics of Games and Auctions

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C62 - Existence and Stability Conditions of Equilibrium

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- C67 - Input-Output Models

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C70 - General

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C73 - Stochastic and Dynamic Games; Evolutionary Games; Repeated Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C83 - Survey Methods; Sampling Methods

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D13 - Household Production and Intrahousehold Allocation

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- D25 - Intertemporal Firm Choice: Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- D29 - Other

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D41 - Perfect Competition

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D47 - Market Design

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D51 - Exchange and Production Economies

- D52 - Incomplete Markets

- D53 - Financial Markets

- D57 - Input-Output Tables and Analysis

- D58 - Computable and Other Applied General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E03 - Behavioral Macroeconomics

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E10 - General

- E12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-Keynesian

- E13 - Neoclassical

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E20 - General

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E40 - General

- E41 - Demand for Money

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E49 - Other

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in E7 - Macro-Based Behavioral Economics

- E70 - General

- E71 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on the Macro Economy

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- F19 - Other

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F40 - General

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F44 - International Business Cycles

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- F63 - Economic Development

- F64 - Environment

- F65 - Finance

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- G02 - Behavioral Finance: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G40 - General

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H30 - General

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H81 - Governmental Loans; Loan Guarantees; Credits; Grants; Bailouts

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I13 - Health Insurance, Public and Private

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I25 - Education and Economic Development

- I26 - Returns to Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- I39 - Other

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J14 - Economics of the Elderly; Economics of the Handicapped; Non-Labor Market Discrimination

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J30 - General

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J32 - Nonwage Labor Costs and Benefits; Retirement Plans; Private Pensions

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- J42 - Monopsony; Segmented Labor Markets

- J44 - Professional Labor Markets; Occupational Licensing

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J50 - General

- J52 - Dispute Resolution: Strikes, Arbitration, and Mediation; Collective Bargaining

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J60 - General

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J71 - Discrimination

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J81 - Working Conditions

- J82 - Labor Force Composition

- J83 - Workers' Rights

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K0 - General

- K00 - General

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K14 - Criminal Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K31 - Labor Law

- K33 - International Law

- K35 - Personal Bankruptcy Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L0 - General

- L00 - General

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L10 - General

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L15 - Information and Product Quality; Standardization and Compatibility

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L20 - General

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L23 - Organization of Production

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive Practices

- L42 - Vertical Restraints; Resale Price Maintenance; Quantity Discounts

- L43 - Legal Monopolies and Regulation or Deregulation

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L50 - General

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L62 - Automobiles; Other Transportation Equipment; Related Parts and Equipment

- L63 - Microelectronics; Computers; Communications Equipment

- Browse content in L7 - Industry Studies: Primary Products and Construction

- L71 - Mining, Extraction, and Refining: Hydrocarbon Fuels

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L81 - Retail and Wholesale Trade; e-Commerce

- L82 - Entertainment; Media

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L93 - Air Transportation

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L96 - Telecommunications

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M0 - General

- M00 - General

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M11 - Production Management

- M14 - Corporate Culture; Social Responsibility

- Browse content in M2 - Business Economics

- M21 - Business Economics

- Browse content in M3 - Marketing and Advertising

- M31 - Marketing

- M37 - Advertising

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M52 - Compensation and Compensation Methods and Their Effects

- M54 - Labor Management

- M55 - Labor Contracting Devices

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N31 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N32 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N34 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N42 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N43 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N44 - Europe: 1913-

- N45 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N9 - Regional and Urban History

- N90 - General, International, or Comparative

- N92 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N94 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O42 - Monetary Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O44 - Environment and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O51 - U.S.; Canada

- O55 - Africa

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P0 - General

- P00 - General

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P26 - Political Economy; Property Rights

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q16 - R&D; Agricultural Technology; Biofuels; Agricultural Extension Services

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q55 - Technological Innovation

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R13 - General Equilibrium and Welfare Economic Analysis of Regional Economies

- R15 - Econometric and Input-Output Models; Other Models

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R21 - Housing Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R33 - Nonagricultural and Nonresidential Real Estate Markets

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- R48 - Government Pricing and Policy

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R51 - Finance in Urban and Rural Economies

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z10 - General

- Z12 - Religion

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The Review of Economic Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Behavioural Economics

Behavioural economics is an approach to economic analysis that blends insights from economics and psychology to explain how people make everyday economic decisions, and how these affect economic outcomes. The collection of articles below covers a variety of research in this area such as asking why people vote, to how much monetary and non-monetary incentives motivate effort, as well as the topics of social welfare dependency, competition for consumer attention, and tax manipulation. These articles have been collated by the editors of The Review of Economic Studies and are free to read until the end of March 2019.

Endogenous Depth of Reasoning Larbi Alaoui and Antonio Penta

The Sunk-Cost Fallacy in Penny Auctions Ned Augenblick

Competition for Attention Pedro Bordalo, Nicola Gennaioli, and Andrei Shleifer

Welfare Dependence and Self-Control: An Empirical Analysis Marc K. Chan

The Demand for Bad Policy when Voters Underappreciate Equilibrium Effects Ernesto Dal Bó, Pedro Dal Bó, and Erik Eyster

Voting to Tell Others Stefano Dellavigna, John A. List, Ulrike Malmendier, and Gautam Rao

What Motivates Effort? Evidence and Expert Forecasts Stefano DellaVigna and Devin Pope

Excusing Selfishness in Charitable Giving: The Role of Risk Christine L. Exley

Inferior Products and Profitable Deception Paul Heidhues, Botond K?szegi, and Takeshi Murooka

Expectations-Based Reference-Dependent Life-Cycle Consumption Michaela Pagel

Quantifying Loss-Averse Tax Manipulation Alex Rees-Jones

“Data Monkeys”: A Procedural Model of Extrapolation from Partial Statistics Ran Spiegler

- Recommend to your Library

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1467-937X

- Print ISSN 0034-6527

- Copyright © 2024 Review of Economic Studies Ltd

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Covering a story? Visit our page for journalists or call (773) 702-8360.

UChicago Class Visits

Top stories.

- Author and ‘Odyssey’ translator Daniel Mendelsohn to deliver Berlin Family Lectures beginning April 23

National study finds in-school, high-dosage tutoring can reverse pandemic-era learning loss

Ethan bueno de mesquita appointed dean of the harris school of public policy, behavioral economics, explained.

Behavioral economics combines elements of economics and psychology to understand how and why people behave the way they do in the real world. It differs from neoclassical economics, which assumes that most people have well-defined preferences and make well-informed, self-interested decisions based on those preferences.

Shaped by the field-defining work of University of Chicago scholar and Nobel laureate Richard Thaler, behavioral economics examines the differences between what people “should” do and what they actually do and the consequences of those actions.

Jump to a section:

What is behavioral economics, what are the origins of behavioral economics research, and who are tversky and kahneman.

- What role have Richard Thaler and University of Chicago economists played in the development of the field?

What is a “nudge” in behavioral economics?

Guide to behavioral economics terms.

Behavioral economics is grounded in empirical observations of human behavior, which have demonstrated that people do not always make what neoclassical economists consider the “rational” or “optimal” decision, even if they have the information and the tools available to do so.

For example, why do people often avoid or delay investing in 401ks or exercising, even if they know that doing those things would benefit them? And why do gamblers often risk more after both winning and losing, even though the odds remain the same, regardless of “streaks”?

By asking questions like these and identifying answers through experiments, the field of behavioral economics considers people as human beings who are subject to emotion and impulsivity, and who are influenced by their environments and circumstances.

This characterization draws a contrast to traditional economic models that have treated people as purely rational actors—who have perfect self-control and never lose sight of their long-term goals—or as people who occasionally make random errors that cancel out in the long run.

Several principles have emerged from behavioral economics research that have helped economists better understand human economic behavior. From these principles, governments and businesses have developed policy frameworks to encourage people to make particular choices.

Behavioral economics has expanded since the 1980s, but it has a long history: According to Thaler, some important ideas in the field can be traced back to 18th-century Scottish economist Adam Smith.

Smith is often remembered for the concept of an “invisible hand” that guides an overall economy to prosperity if each individual makes their own self-interested decisions—a key concept in classical and neoclassical economics. But he also recognized that people are often overconfident in their own abilities, more afraid of losing than they are eager to win and more likely to pursue short-term than long-term benefits. These ideas (overconfidence, loss aversion and self-control) are foundational concepts in behavioral economics today.

More recently, behavioral economics has early roots in the work of Israeli psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman on uncertainty and risk. In the 1970s and ’80s, Tversky and Kahneman identified several consistent biases in the way people make judgments, finding that people often rely on easily recalled information, rather than actual data, when evaluating the likelihood of a particular outcome, a concept known as the “availability heuristic.” For example, people may think shark or bear attacks are a common cause of death if they’ve read about one such attack, but the incidents are actually very rare.

With “prospect theory,” Tversky and Kahneman also demonstrated that framing and loss aversion influence the choices people make. For example, if presented with an opportunity to win $250 guaranteed or gamble on a 25% chance of winning $1,000 and a 75% chance of winning nothing, most people will choose the sure win. But if presented with the chance to lose $750 guaranteed or a 75% chance to lose $1,000 and a 25% chance to lose nothing, most people will risk losing $1,000, hoping for the slim chance that they will lose nothing at all.

This classic example demonstrates that people are more willing to take a greater statistical risk if it means avoiding a $1,000 loss versus obtaining a $1,000 win, which contradicts expected utility theory. Prospect theory and other work by Tversky and Kahneman continues to inform many areas of behavioral economics research today.

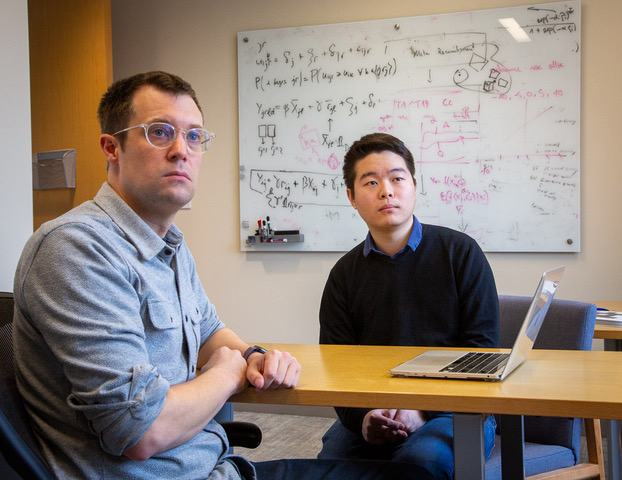

What role have Richard Thaler and behavioral economists at the University of Chicago played in the development of the field?

In the 1980s, Richard Thaler began to build on the work of Tversky and Kahneman, with whom he collaborated extensively. Now the Charles R. Walgreen Distinguished Service Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics at the Booth School of Business, he is today considered a founder of the field of behavioral economics.

Thaler’s research in identifying the factors that guide individuals’ economic decision-making earned him the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 2017. His ideas stem in part from a series of observations he made in graduate school that led him to believe that people’s behavior deviated from traditional economic models in predictable ways.

For example, Thaler observed that he and a friend were willing to forgo a drive to a sporting event due to a snowstorm because they had been given free tickets. But had they purchased the tickets themselves, they would have been more inclined to go, even though the tickets would have been valued at the same price regardless, and the danger of driving in the snowstorm unchanged. This is an example of the “sunk cost fallacy”—the idea that people are less willing to give up on projects they have personally invested in, even if it means more risk.

Thaler is also known for popularizing the concept of the “nudge,” a conceptual device for leading people to make better decisions. A “nudge” takes advantage of human psychology and a number of other concepts in behavioral economics, including mental accounting—the idea that people treat money differently based on context. For example, people are more willing to drive across town to save $10 on a $20 purchase than $10 on a $1,000 purchase, even though the effort expended and the amount of money saved would be the same.

Thaler and other UChicago economists—including Leonardo Bursztyn, Josh Dean, Nicholas Epley, Austan Goolsbee, Alex Imas, John List, Susan Mayer, Sendhil Mullainathan, Devin Pope, Rebecca Dizon Ross and Heather Sarsons—continue to conduct empirical research, including field experiments, that explore behavioral economics from multiple angles.

In behavioral economics, a “nudge” is a way to manipulate people’s choices to lead them to make specific decisions: For example, putting fruit at eye level or near the cash register at a high school cafeteria is an example of a “nudge” to get students to choose healthier options. An essential aspect of nudges is that they are not coercive: Banning junk food is not a nudge, nor is punishing people for choosing unhealthy options.

Thaler’s ideas about nudges were popularized in Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness , his 2008 book with former UChicago legal scholar Cass Sunstein, now of Harvard University. Businesses and governments, including the U.S. government under President Barack Obama, have adapted Thaler and Sunstein’s ideas about nudges into policy.

For example, automatically enrolling employees in 401k plans—and asking them to opt out rather than offering them the chance to opt in—is an example of a nudge to encourage better and more consistent saving for retirement. Another seeks to make organ donation standard practice, by requiring people registering for drivers’ licenses to indicate whether or not they are willing to donate.

The formal term Thaler and Sunstein use to describe a situation designed around nudges is “libertarian paternalism”—libertarian because it preserves choice, but paternalistic because it encourages certain behavior. In Thaler’s words: “If you want people to do something, make it easy.”

The availability heuristic refers to the idea that people often rely on easily recalled information, rather than actual data, when evaluating the likelihood of a particular outcome. For example, people may think shark or bear attacks are a common cause of death if they’ve read about one such attack, but the incidents are actually very rare.

Bounded rationality refers to the fact that people have limited cognitive ability, information and time, and do not always make the “correct” choice from an economist’s point of view, even if information is available that would point them toward a particular course of action.

This might be because they cannot synthesize new information quickly; because they ignore it and instead choose to “go with their gut”; or because they don’t have the time to fully research all options. The term was coined in 1955 by Nobel laureate and UChicago alum Herbert A. Simon, AB’36, PhD’43.

Bounded self-interest is the idea that people are often willing to choose a less-optimal outcome for themselves if it means they can support others. Giving to charity is an example of bounded self-interest, as is volunteering. While these are common activities, they are not captured by traditional economic models, which predict that people act mostly to further their own goals and those of their immediate family and friends, rather than strangers.

Bounded willpower captures the idea that even given an understanding of the optimal choice, people will often still preferentially choose whatever brings the most short-term benefit over incremental progress toward a long-term goal. For example, even if we know that exercising may help us obtain our fitness goals, we may put it off indefinitely, saying we will “start tomorrow.”

Loss aversion is the idea that people are more averse to losses than they are eager to make gains. For example, losing a $100 bill might be more painful than finding a $100 bill would be positive.

Prospect theory refers to a series of empirical observations made by Kahneman and Tversky (1979) in which they asked people about how they would respond to certain hypothetical situations involving wins and losses, allowing them to characterize human economic behavior. Loss aversion is key to prospect theory.

The sunk-cost fallacy is the idea that people will continue to invest in a losing project simply because they are already heavily invested, even if it means risking more losses.

Mental accounting is the idea that people think about money differently depending on the circumstances. For example, if the price of gas goes down, they may begin to buy premium gas, leading them to ultimately spend the same amount, rather than taking advantage of the savings offered by the lower price.

Related Experts

Richard Thaler

Sendhil Mullainathan

Nicholas Epley

More Explainers

Improv, Explained

Cosmic rays, explained

Thaler’s Nudge gets global attention— The University of Chicago

The Two Friends Who Changed How We Think About How We Think— The New Yorker

Richard H. Thaler Facts— The Nobel Prize

7 Richard Thaler Columns That Explain How Human Behavior Affects Economics— The New York Times

NBER Working Paper on Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics from nuts to ‘nudges’— Chicago Booth Review

Related Topics

Latest news, big brains podcast: what dogs are teaching us about aging.

Department of Race, Diaspora, and Indigeneity

Course on Afrofuturism brings together UChicago students and community members

Eclipse 2024

What eclipses have meant to people across the ages

Dark matter

First results from BREAD experiment demonstrate a new approach to searching for dark matter

Where do breakthrough discoveries and ideas come from?

Explore The Day Tomorrow Began

Study finds increase in suicides among Black and Latino Chicagoans

Education Lab

Around UChicago

It’s in our core

New initiative highlights UChicago’s unique undergraduate experience

Alumni Awards

Two Nobel laureates among recipients of UChicago’s 2024 Alumni Awards

Faculty Awards

Profs. John MacAloon and Martha Nussbaum to receive 2024 Norman Maclean Faculty…

Sloan Research Fellowships

Five UChicago scholars awarded prestigious Sloan Fellowships in 2024

Convocation

Prof. John List named speaker for UChicago’s 2024 Convocation ceremony

The College

Anna Chlumsky, AB’02, named UChicago’s 2024 Class Day speaker

UChicago Medicine

“I saw an opportunity to leverage the intellectual firepower of a world-class university for advancing cancer research and care.”

Announcement

Behavioral Economics

- First Online: 11 June 2021

Cite this chapter

- Martin Kolmar 2

Part of the book series: Classroom Companion: Economics ((CCE))

3184 Accesses

In this chapter you will learn …

the basic ideas of behavioral economics.

what a bias is and how a bias can be defined.

important biases.

how to distinguish between non-rational and non-selfish behavior.

models to explain cooperative behavior.

models of boundedly rational behavior.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alloy, L. B., & Abrahamson, L. Y. (1979). Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser?. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108 (4), 441–485.

Article Google Scholar

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably irrational . New York: Harper Collins.

Google Scholar

Arrow, K. J. (1983). Collected papers of Kenneth J. Arrow, Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

Bacon, F. (1620/1939). The New Organon . New York: Liberal Arts Press.

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1994). Better than rational: Evolutionary psychology and the invisible hand. American Economic Review, 84 (2), 327–332.

Frank, R. H., Gilovich, T., & Regan, D. T. (1993). Does studying economics inhibit cooperation? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7 (2), 159–171.

Green, D. M. & Swets, J. A. (1966). Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics . Wiley, New York.

Haselton, M. G., & Nettle, D. (2006). The paranoid optimist: An integrative evolutionary model of cognitive biases. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10 (1), 47–66.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47 (2), 263–291.

Kahneman, D., Tversky, A. (1986). Rational Choice and the Framing of Decisions, The Journal of Business, 59 (4), 251–278.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5 (4), 297–324.

Koehler, J. J. (1993). The influence of prior beliefs on scientific judgments of evidence quality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 56 , 28–55.

Larney, A., Rotella, A., & Barclay, P. (2019). Stake size effects in ultimatum game and dictator game offers: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 151 , 61–72.

Lima, S. L., & Dill, L. M. (1990). Behavioral decisions made under the risk of predation: a review and prospectus. Canadian Journal of Zoology 68 , 619–640.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 (11), 2098–2109.

Mahoney, M. J. (1977). Publication prejudices: An experimental study of confirmatory bias in the peer review system. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1 (2), 161–175.

Pierce, A. H. (1908). The Subconscious Again. Journal of Psychology and Psychological Scientific Method, 5 , 264–271.

Rodrik, D. (2011). The globalization paradox: Democracy and the future of the world economy . New York, London: W.W. Norton.

Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 12 (3), 129–140.

Weber, M., & Camerer, C. (1998). The disposition effect in securities trading: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 33 , 167–184.

Westen, D., Blagov, P. S., Harenski, K., Kilts, C., & Hamann, S. (2006). Neural bases of motivated reasoning: An fMRI study of emotional constraints on partisan political judgment in the 2004 U.S. Presidential election. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18 (11), 1947–1958.

Further Reading

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably irrational: The hidden forces that shape our decisions . Harper Collins.

Bernheim, B. D. (2009). Behavioral welfare economics. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7 , 267–319. MIT Press

Bernheim, D., & Rangel, A. (2008): Choice-theoretic foundations for behavioral welfare economics. In A. Caplin & A. Schotter (Eds.), The foundations of positive and normative economics . Oxford University Press.

Cooper, D., & Kagel, J. (2016). Other-regarding preferences - Selective survey of experimental results. In J. Kagel & A. Roth (Eds.), The handbook of experimental economics (Vol. 2, Chap. 4).

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. (2006). The economics of fairness, reciprocity and altruism – Experimental evidence and new theories. In S.-C. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of giving, reciprocity and altruism (Chap. 8). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Laibson, D., & List, J. A. (2015). Principles of (behavioral) economics. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 105 (5), 385–390.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute for Business Ethics Department of Economics, Universität St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Martin Kolmar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Kolmar, M. (2022). Behavioral Economics. In: Principles of Microeconomics. Classroom Companion: Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78167-5_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78167-5_10

Published : 11 June 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-78166-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-78167-5

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Utility Menu

44d3fa3df9f06a3117ed3d2ad6c71ecc

- Administration

Behavioral Economics

Raj Chetty is the William A. Ackman Professor of Public Economics at Harvard University. He is also the Director of Opportunity Insights, which uses “big...

Benjamin Enke

Benjamin Enke is an Assistant Professor at Harvard's Department of Economics. Ben received his Ph.D. in Economics from Bonn in 2016. His research focuses...

Xavier Gabaix

Xavier Gabaix is Pershing Square Professor of Economics and Finance at Harvard’s economics department. He received his undergraduate degree in mathematics from the Ecole Normale Supérieure (Paris) and obtained his PhD in economics from Harvard University.... Read more about Xavier Gabaix

Jerry Green

Jerry Green is the John Leverett Professor in the University and the David A. Wells Professor of Political Economy in the Department of Economics.... Read more about Jerry Green

David Laibson

David Laibson is a member of the National Bureau of Economic Research, where he is Research Associate in the Asset Pricing, Economic Fluctuations, and Aging Working Groups. Laibsonʼs research focuses on the topic of behavioral economics, and he is a co-leader of the Harvard University Foundations of Human Behavior Initiative. ... Read more about David Laibson

Prior to joining the Economics Department Faculty, Shengwu Li was a Junior Fellow of the Society of Fellows.

Staff Support:...

Matthew Rabin

Matthew Rabin is the Pershing Square Professor of Behavioral Economics in the Harvard Economics Department and Harvard Business School.... Read more about Matthew Rabin

Andrei Shleifer

Andrei Shleifer has worked in the areas of comparative corporate governance, law and finance, behavioral finance, as well as institutional economics. He has published six books, including The Grabbing Hand (with Robert Vishny), and Inefficient Markets: An Introduction to Behavioral Finance , as well as over a hundred articles. In 1999, Shleifer won the John Bates Clark medal of the American Economic Association.... Read more about Andrei Shleifer

Tomasz Strzalecki

Tomasz Strzalecki's research interests are in decision theory and economic theory. He has focused on ambiguity aversion, temporal preferences, and bounded rationality.... Read more about Tomasz Strzalecki

Eric Unverzagt

Faculty Assistant to Professors Pallais ,...

David Y. Yang is a Professor in the Department of Economics at Harvard University and Director of the Center for History and Economics at Harvard. David...

- Behavioral Economics (11)

- Contracts and Organization (1)

- Economic Development (7)

- Econometrics (6)

- Economic History (7)

- Financial Economics (9)

- Industrial Organization (3)

- International Economics (6)

- Labor Economics (11)

- Macroeconomics (16)

- Political Economy (9)