Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods

Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on August 20, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analyzing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyze the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyze the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research : investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research : finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research : collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics : measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology : researching personality traits, preferences and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and in longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- US college students

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18-24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalized to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

Several common research biases can arise if your survey is not generalizable, particularly sampling bias and selection bias . The presence of these biases have serious repercussions for the validity of your results.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every college student in the US. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalize to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions. Again, beware of various types of sampling bias as you design your sample, particularly self-selection bias , nonresponse bias , undercoverage bias , and survivorship bias .

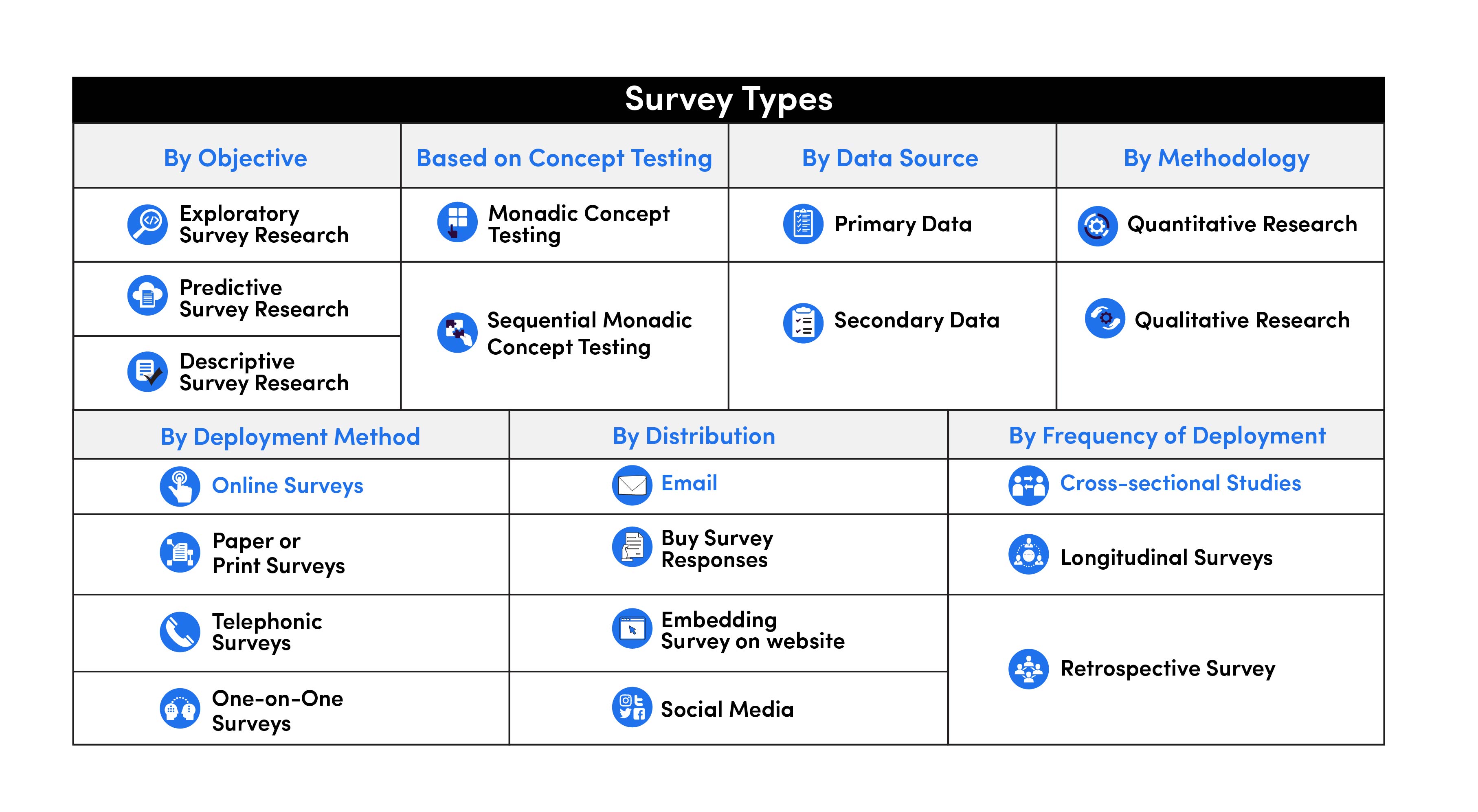

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by mail, online or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves.

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses.

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by mail is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g. residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low, and at risk for biases like self-selection bias .

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyze.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds, which can lead to biases like self-selection bias .

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping mall or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g. the opinions of a store’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations and is at risk for sampling bias .

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data: the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyzes the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analyzed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g. yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g. a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g. age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g. leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analyzed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an “other” field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic. Avoid jargon or industry-specific terminology.

Survey questions are at risk for biases like social desirability bias , the Hawthorne effect , or demand characteristics . It’s critical to use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no indication that you’d prefer a particular answer or emotion.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by mail, online, or in person.

There are many methods of analyzing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also clean the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organizing them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analyzing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analyzed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyze it. In the results section, you summarize the key results from your analysis.

In the discussion and conclusion , you give your explanations and interpretations of these results, answer your research question, and reflect on the implications and limitations of the research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analyzing data from people using questionnaires.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviors. It is made up of 4 or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with 5 or 7 possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyze your data.

The priorities of a research design can vary depending on the field, but you usually have to specify:

- Your research questions and/or hypotheses

- Your overall approach (e.g., qualitative or quantitative )

- The type of design you’re using (e.g., a survey , experiment , or case study )

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods (e.g., questionnaires , observations)

- Your data collection procedures (e.g., operationalization , timing and data management)

- Your data analysis methods (e.g., statistical tests or thematic analysis )

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/survey-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, questionnaire design | methods, question types & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Table of Contents

Survey Research

Definition:

Survey Research is a quantitative research method that involves collecting standardized data from a sample of individuals or groups through the use of structured questionnaires or interviews. The data collected is then analyzed statistically to identify patterns and relationships between variables, and to draw conclusions about the population being studied.

Survey research can be used to answer a variety of questions, including:

- What are people’s opinions about a certain topic?

- What are people’s experiences with a certain product or service?

- What are people’s beliefs about a certain issue?

Survey Research Methods

Survey Research Methods are as follows:

- Telephone surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents over the phone, often used in market research or political polling.

- Face-to-face surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents in person, often used in social or health research.

- Mail surveys: A survey research method where questionnaires are sent to respondents through mail, often used in customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Online surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through online platforms, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Email surveys: A survey research method where questionnaires are sent to respondents through email, often used in customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Mixed-mode surveys: A survey research method that combines two or more survey modes, often used to increase response rates or reach diverse populations.

- Computer-assisted surveys: A survey research method that uses computer technology to administer or collect survey data, often used in large-scale surveys or data collection.

- Interactive voice response surveys: A survey research method where respondents answer questions through a touch-tone telephone system, often used in automated customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Mobile surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through mobile devices, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Group-administered surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to a group of respondents simultaneously, often used in education or training evaluation.

- Web-intercept surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to website visitors, often used in website or user experience research.

- In-app surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to users of a mobile application, often used in mobile app or user experience research.

- Social media surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through social media platforms, often used in social media or brand awareness research.

- SMS surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through text messaging, often used in customer feedback or opinion surveys.

- IVR surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through an interactive voice response system, often used in automated customer feedback or opinion surveys.

- Mixed-method surveys: A survey research method that combines both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, often used in exploratory or mixed-method research.

- Drop-off surveys: A survey research method where respondents are provided with a survey questionnaire and asked to return it at a later time or through a designated drop-off location.

- Intercept surveys: A survey research method where respondents are approached in public places and asked to participate in a survey, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Hybrid surveys: A survey research method that combines two or more survey modes, data sources, or research methods, often used in complex or multi-dimensional research questions.

Types of Survey Research

There are several types of survey research that can be used to collect data from a sample of individuals or groups. following are Types of Survey Research:

- Cross-sectional survey: A type of survey research that gathers data from a sample of individuals at a specific point in time, providing a snapshot of the population being studied.

- Longitudinal survey: A type of survey research that gathers data from the same sample of individuals over an extended period of time, allowing researchers to track changes or trends in the population being studied.

- Panel survey: A type of longitudinal survey research that tracks the same sample of individuals over time, typically collecting data at multiple points in time.

- Epidemiological survey: A type of survey research that studies the distribution and determinants of health and disease in a population, often used to identify risk factors and inform public health interventions.

- Observational survey: A type of survey research that collects data through direct observation of individuals or groups, often used in behavioral or social research.

- Correlational survey: A type of survey research that measures the degree of association or relationship between two or more variables, often used to identify patterns or trends in data.

- Experimental survey: A type of survey research that involves manipulating one or more variables to observe the effect on an outcome, often used to test causal hypotheses.

- Descriptive survey: A type of survey research that describes the characteristics or attributes of a population or phenomenon, often used in exploratory research or to summarize existing data.

- Diagnostic survey: A type of survey research that assesses the current state or condition of an individual or system, often used in health or organizational research.

- Explanatory survey: A type of survey research that seeks to explain or understand the causes or mechanisms behind a phenomenon, often used in social or psychological research.

- Process evaluation survey: A type of survey research that measures the implementation and outcomes of a program or intervention, often used in program evaluation or quality improvement.

- Impact evaluation survey: A type of survey research that assesses the effectiveness or impact of a program or intervention, often used to inform policy or decision-making.

- Customer satisfaction survey: A type of survey research that measures the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of customers with a product, service, or experience, often used in marketing or customer service research.

- Market research survey: A type of survey research that collects data on consumer preferences, behaviors, or attitudes, often used in market research or product development.

- Public opinion survey: A type of survey research that measures the attitudes, beliefs, or opinions of a population on a specific issue or topic, often used in political or social research.

- Behavioral survey: A type of survey research that measures actual behavior or actions of individuals, often used in health or social research.

- Attitude survey: A type of survey research that measures the attitudes, beliefs, or opinions of individuals, often used in social or psychological research.

- Opinion poll: A type of survey research that measures the opinions or preferences of a population on a specific issue or topic, often used in political or media research.

- Ad hoc survey: A type of survey research that is conducted for a specific purpose or research question, often used in exploratory research or to answer a specific research question.

Types Based on Methodology

Based on Methodology Survey are divided into two Types:

Quantitative Survey Research

Qualitative survey research.

Quantitative survey research is a method of collecting numerical data from a sample of participants through the use of standardized surveys or questionnaires. The purpose of quantitative survey research is to gather empirical evidence that can be analyzed statistically to draw conclusions about a particular population or phenomenon.

In quantitative survey research, the questions are structured and pre-determined, often utilizing closed-ended questions, where participants are given a limited set of response options to choose from. This approach allows for efficient data collection and analysis, as well as the ability to generalize the findings to a larger population.

Quantitative survey research is often used in market research, social sciences, public health, and other fields where numerical data is needed to make informed decisions and recommendations.

Qualitative survey research is a method of collecting non-numerical data from a sample of participants through the use of open-ended questions or semi-structured interviews. The purpose of qualitative survey research is to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences, perceptions, and attitudes of participants towards a particular phenomenon or topic.

In qualitative survey research, the questions are open-ended, allowing participants to share their thoughts and experiences in their own words. This approach allows for a rich and nuanced understanding of the topic being studied, and can provide insights that are difficult to capture through quantitative methods alone.

Qualitative survey research is often used in social sciences, education, psychology, and other fields where a deeper understanding of human experiences and perceptions is needed to inform policy, practice, or theory.

Data Analysis Methods

There are several Survey Research Data Analysis Methods that researchers may use, including:

- Descriptive statistics: This method is used to summarize and describe the basic features of the survey data, such as the mean, median, mode, and standard deviation. These statistics can help researchers understand the distribution of responses and identify any trends or patterns.

- Inferential statistics: This method is used to make inferences about the larger population based on the data collected in the survey. Common inferential statistical methods include hypothesis testing, regression analysis, and correlation analysis.

- Factor analysis: This method is used to identify underlying factors or dimensions in the survey data. This can help researchers simplify the data and identify patterns and relationships that may not be immediately apparent.

- Cluster analysis: This method is used to group similar respondents together based on their survey responses. This can help researchers identify subgroups within the larger population and understand how different groups may differ in their attitudes, behaviors, or preferences.

- Structural equation modeling: This method is used to test complex relationships between variables in the survey data. It can help researchers understand how different variables may be related to one another and how they may influence one another.

- Content analysis: This method is used to analyze open-ended responses in the survey data. Researchers may use software to identify themes or categories in the responses, or they may manually review and code the responses.

- Text mining: This method is used to analyze text-based survey data, such as responses to open-ended questions. Researchers may use software to identify patterns and themes in the text, or they may manually review and code the text.

Applications of Survey Research

Here are some common applications of survey research:

- Market Research: Companies use survey research to gather insights about customer needs, preferences, and behavior. These insights are used to create marketing strategies and develop new products.

- Public Opinion Research: Governments and political parties use survey research to understand public opinion on various issues. This information is used to develop policies and make decisions.

- Social Research: Survey research is used in social research to study social trends, attitudes, and behavior. Researchers use survey data to explore topics such as education, health, and social inequality.

- Academic Research: Survey research is used in academic research to study various phenomena. Researchers use survey data to test theories, explore relationships between variables, and draw conclusions.

- Customer Satisfaction Research: Companies use survey research to gather information about customer satisfaction with their products and services. This information is used to improve customer experience and retention.

- Employee Surveys: Employers use survey research to gather feedback from employees about their job satisfaction, working conditions, and organizational culture. This information is used to improve employee retention and productivity.

- Health Research: Survey research is used in health research to study topics such as disease prevalence, health behaviors, and healthcare access. Researchers use survey data to develop interventions and improve healthcare outcomes.

Examples of Survey Research

Here are some real-time examples of survey research:

- COVID-19 Pandemic Surveys: Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, surveys have been conducted to gather information about public attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions related to the pandemic. Governments and healthcare organizations have used this data to develop public health strategies and messaging.

- Political Polls During Elections: During election seasons, surveys are used to measure public opinion on political candidates, policies, and issues in real-time. This information is used by political parties to develop campaign strategies and make decisions.

- Customer Feedback Surveys: Companies often use real-time customer feedback surveys to gather insights about customer experience and satisfaction. This information is used to improve products and services quickly.

- Event Surveys: Organizers of events such as conferences and trade shows often use surveys to gather feedback from attendees in real-time. This information can be used to improve future events and make adjustments during the current event.

- Website and App Surveys: Website and app owners use surveys to gather real-time feedback from users about the functionality, user experience, and overall satisfaction with their platforms. This feedback can be used to improve the user experience and retain customers.

- Employee Pulse Surveys: Employers use real-time pulse surveys to gather feedback from employees about their work experience and overall job satisfaction. This feedback is used to make changes in real-time to improve employee retention and productivity.

Survey Sample

Purpose of survey research.

The purpose of survey research is to gather data and insights from a representative sample of individuals. Survey research allows researchers to collect data quickly and efficiently from a large number of people, making it a valuable tool for understanding attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

Here are some common purposes of survey research:

- Descriptive Research: Survey research is often used to describe characteristics of a population or a phenomenon. For example, a survey could be used to describe the characteristics of a particular demographic group, such as age, gender, or income.

- Exploratory Research: Survey research can be used to explore new topics or areas of research. Exploratory surveys are often used to generate hypotheses or identify potential relationships between variables.

- Explanatory Research: Survey research can be used to explain relationships between variables. For example, a survey could be used to determine whether there is a relationship between educational attainment and income.

- Evaluation Research: Survey research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a program or intervention. For example, a survey could be used to evaluate the impact of a health education program on behavior change.

- Monitoring Research: Survey research can be used to monitor trends or changes over time. For example, a survey could be used to monitor changes in attitudes towards climate change or political candidates over time.

When to use Survey Research

there are certain circumstances where survey research is particularly appropriate. Here are some situations where survey research may be useful:

- When the research question involves attitudes, beliefs, or opinions: Survey research is particularly useful for understanding attitudes, beliefs, and opinions on a particular topic. For example, a survey could be used to understand public opinion on a political issue.

- When the research question involves behaviors or experiences: Survey research can also be useful for understanding behaviors and experiences. For example, a survey could be used to understand the prevalence of a particular health behavior.

- When a large sample size is needed: Survey research allows researchers to collect data from a large number of people quickly and efficiently. This makes it a useful method when a large sample size is needed to ensure statistical validity.

- When the research question is time-sensitive: Survey research can be conducted quickly, which makes it a useful method when the research question is time-sensitive. For example, a survey could be used to understand public opinion on a breaking news story.

- When the research question involves a geographically dispersed population: Survey research can be conducted online, which makes it a useful method when the population of interest is geographically dispersed.

How to Conduct Survey Research

Conducting survey research involves several steps that need to be carefully planned and executed. Here is a general overview of the process:

- Define the research question: The first step in conducting survey research is to clearly define the research question. The research question should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the population of interest.

- Develop a survey instrument : The next step is to develop a survey instrument. This can be done using various methods, such as online survey tools or paper surveys. The survey instrument should be designed to elicit the information needed to answer the research question, and should be pre-tested with a small sample of individuals.

- Select a sample : The sample is the group of individuals who will be invited to participate in the survey. The sample should be representative of the population of interest, and the size of the sample should be sufficient to ensure statistical validity.

- Administer the survey: The survey can be administered in various ways, such as online, by mail, or in person. The method of administration should be chosen based on the population of interest and the research question.

- Analyze the data: Once the survey data is collected, it needs to be analyzed. This involves summarizing the data using statistical methods, such as frequency distributions or regression analysis.

- Draw conclusions: The final step is to draw conclusions based on the data analysis. This involves interpreting the results and answering the research question.

Advantages of Survey Research

There are several advantages to using survey research, including:

- Efficient data collection: Survey research allows researchers to collect data quickly and efficiently from a large number of people. This makes it a useful method for gathering information on a wide range of topics.

- Standardized data collection: Surveys are typically standardized, which means that all participants receive the same questions in the same order. This ensures that the data collected is consistent and reliable.

- Cost-effective: Surveys can be conducted online, by mail, or in person, which makes them a cost-effective method of data collection.

- Anonymity: Participants can remain anonymous when responding to a survey. This can encourage participants to be more honest and open in their responses.

- Easy comparison: Surveys allow for easy comparison of data between different groups or over time. This makes it possible to identify trends and patterns in the data.

- Versatility: Surveys can be used to collect data on a wide range of topics, including attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and preferences.

Limitations of Survey Research

Here are some of the main limitations of survey research:

- Limited depth: Surveys are typically designed to collect quantitative data, which means that they do not provide much depth or detail about people’s experiences or opinions. This can limit the insights that can be gained from the data.

- Potential for bias: Surveys can be affected by various biases, including selection bias, response bias, and social desirability bias. These biases can distort the results and make them less accurate.

- L imited validity: Surveys are only as valid as the questions they ask. If the questions are poorly designed or ambiguous, the results may not accurately reflect the respondents’ attitudes or behaviors.

- Limited generalizability : Survey results are only generalizable to the population from which the sample was drawn. If the sample is not representative of the population, the results may not be generalizable to the larger population.

- Limited ability to capture context: Surveys typically do not capture the context in which attitudes or behaviors occur. This can make it difficult to understand the reasons behind the responses.

- Limited ability to capture complex phenomena: Surveys are not well-suited to capture complex phenomena, such as emotions or the dynamics of interpersonal relationships.

Following is an example of a Survey Sample:

Welcome to our Survey Research Page! We value your opinions and appreciate your participation in this survey. Please answer the questions below as honestly and thoroughly as possible.

1. What is your age?

- A) Under 18

- G) 65 or older

2. What is your highest level of education completed?

- A) Less than high school

- B) High school or equivalent

- C) Some college or technical school

- D) Bachelor’s degree

- E) Graduate or professional degree

3. What is your current employment status?

- A) Employed full-time

- B) Employed part-time

- C) Self-employed

- D) Unemployed

4. How often do you use the internet per day?

- A) Less than 1 hour

- B) 1-3 hours

- C) 3-5 hours

- D) 5-7 hours

- E) More than 7 hours

5. How often do you engage in social media per day?

6. Have you ever participated in a survey research study before?

7. If you have participated in a survey research study before, how was your experience?

- A) Excellent

- E) Very poor

8. What are some of the topics that you would be interested in participating in a survey research study about?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

9. How often would you be willing to participate in survey research studies?

- A) Once a week

- B) Once a month

- C) Once every 6 months

- D) Once a year

10. Any additional comments or suggestions?

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. Your feedback is important to us and will help us improve our survey research efforts.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analysing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyse the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyse the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research: Investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research: Finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research: Collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics: Measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology: Researching personality traits, preferences, and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- University students in the UK

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18 to 24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalised to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every university student in the UK. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalise to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions.

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by post, online, or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by post is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g., residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low.

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyse.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds.

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping centre or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g., the opinions of a shop’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations.

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data : the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyses the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analysed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g., yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g., a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g., age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g., leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analysed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an ‘other’ field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic.

Use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no bias towards one answer or another.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by post, online, or in person.

There are many methods of analysing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also cleanse the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organising them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analysing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analysed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyse it. In the results section, you summarise the key results from your analysis.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviours. It is made up of four or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with five or seven possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyse your data.

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analysing data from people using questionnaires.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/surveys/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples.

ScienceSphere.blog

Mastering The Art Of Writing A Survey Paper: A Step-By-Step Guide

Table of Contents

Importance of survey papers in academic research

Survey papers play a crucial role in academic research as they provide a comprehensive overview of a specific topic or field. These papers serve as valuable resources for researchers, students, and professionals who want to gain a deeper understanding of a subject. By synthesizing existing literature, survey papers help to identify research gaps, highlight key findings, and offer insights into future research directions.

Survey papers are essential for the following reasons:

Summarizing existing knowledge: Survey papers consolidate and summarize the existing body of knowledge on a particular topic. They provide a comprehensive overview of the research conducted in the field, making it easier for readers to grasp the key concepts and findings.

Identifying research gaps: By analyzing the existing literature, survey papers help researchers identify areas where further investigation is needed. They highlight the gaps in knowledge and suggest potential research questions that can contribute to the advancement of the field.

Saving time and effort: Instead of going through numerous individual research papers, survey papers offer a consolidated source of information. Researchers can save time and effort by referring to a well-structured survey paper that provides a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Providing a foundation for new research: Survey papers serve as a foundation for new research. They provide researchers with a solid understanding of the existing literature, enabling them to build upon previous studies and contribute to the field’s knowledge.

Purpose of the blog post

The purpose of this blog post is to guide aspiring researchers and students on how to write an effective survey paper. It will provide a step-by-step approach to help them navigate through the process of selecting a topic, conducting a literature review, outlining the structure, writing the paper, editing and proofreading, formatting and presentation, and finalizing the survey paper.

By following the guidelines outlined in this blog post, readers will be equipped with the necessary tools and knowledge to produce a high-quality survey paper that adds value to the academic community. Whether they are writing a survey paper for a course assignment, a research project, or a publication, this blog post will serve as a comprehensive resource to help them excel in their writing endeavors.

In the next section, we will delve into the basics of survey papers, including their definition, different types, and the benefits of writing one.

Understanding the Basics

A survey paper is a comprehensive review of existing literature on a specific topic or research area. It aims to provide a summary and analysis of the current state of knowledge in the field. Understanding the basics of survey papers is crucial for researchers and academics who wish to contribute to the existing body of knowledge. Here, we will explore the definition of a survey paper, different types of survey papers, and the benefits of writing one.

Definition of a survey paper

A survey paper, also known as a review paper or a literature review, is a type of academic paper that synthesizes and analyzes existing research on a particular topic. It goes beyond summarizing individual studies and aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the field. The goal of a survey paper is to identify trends, patterns, and gaps in the existing literature .

Different types of survey papers

There are several types of survey papers, each with its own purpose and focus. Some common types include:

Traditional survey papers : These provide a broad overview of the topic, covering various aspects and subtopics. They aim to present a comprehensive summary of the existing literature.

Focused survey papers : These focus on a specific aspect or subtopic within a broader field. They delve deeper into a particular area of interest and provide a more detailed analysis.

Systematic review papers : These follow a specific methodology for selecting and analyzing studies. They aim to minimize bias and provide an objective assessment of the available evidence.

Meta-analysis papers : These involve statistical analysis of data from multiple studies to draw conclusions and identify patterns or relationships.

Benefits of writing a survey paper

Writing a survey paper offers several benefits for researchers and academics:

Understanding the research landscape : Conducting a comprehensive literature review allows researchers to gain a deep understanding of the current state of knowledge in their field. It helps identify gaps, controversies, and areas that require further investigation.

Contributing to the field : By synthesizing and analyzing existing research, survey papers provide valuable insights and perspectives. They can help shape the direction of future research and contribute to the advancement of knowledge.

Building credibility : Publishing a well-written survey paper enhances the author’s reputation and credibility in the academic community. It demonstrates expertise in the field and the ability to critically evaluate and synthesize existing research.

Identifying research opportunities : Survey papers often highlight areas where further research is needed. They can inspire new research questions and guide researchers towards fruitful avenues of investigation.

In conclusion, understanding the basics of survey papers is essential for researchers and academics. It involves knowing the definition of a survey paper, different types of survey papers, and the benefits of writing one. By conducting a comprehensive literature review and synthesizing existing research, survey papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a particular field. They provide valuable insights, identify research gaps, and guide future research directions.

Choosing a Topic

Choosing the right topic is a crucial step in writing a survey paper. It sets the foundation for your research and determines the direction of your paper. Here are some key considerations when selecting a topic:

Identifying a Research Gap

To begin, you need to identify a research gap in the existing literature. Look for areas where there is limited or conflicting information, unanswered questions, or emerging trends. This will ensure that your survey paper adds value to the academic community by filling a knowledge gap .

Selecting a Specific Area of Interest

Once you have identified a research gap, narrow down your focus by selecting a specific area of interest within that gap. Choose a topic that aligns with your expertise and interests . This will make the writing process more enjoyable and allow you to bring a unique perspective to the paper.

Ensuring the Topic is Relevant and Significant

When choosing a topic, it is important to consider its relevance and significance. Select a topic that is timely and has practical implications . This will make your survey paper more valuable to readers and increase its impact. Additionally, consider the potential for future research and the broader implications of your chosen topic.

To ensure the relevance and significance of your topic, you can:

- Review recent publications and conference proceedings to identify emerging trends and hot topics in your field.

- Consult with experts and mentors to get their insights and suggestions on potential topics.

- Consider the practical applications of your chosen topic and how it can contribute to real-world problem-solving.

By following these steps, you can choose a topic that is both interesting to you and valuable to the academic community. Remember, the topic you choose will shape the entire survey paper, so take the time to select it wisely.

In conclusion, choosing a topic for your survey paper involves identifying a research gap, selecting a specific area of interest, and ensuring the topic is relevant and significant. By following these guidelines, you can set the stage for a well-rounded and impactful survey paper.

Conducting a Literature Review

Conducting a thorough literature review is a crucial step in writing a survey paper. It involves searching for relevant sources, evaluating their credibility, and organizing and summarizing the literature. This section will guide you through the process of conducting a literature review effectively.

Searching for relevant sources

When conducting a literature review, it is essential to search for relevant sources that contribute to your understanding of the topic. Here are some tips to help you find the right sources:

Utilize academic databases : Academic databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and IEEE Xplore are excellent resources for finding scholarly articles, conference papers, and research studies related to your topic.

Use appropriate keywords : Use specific keywords and phrases that accurately represent your research topic. This will help you narrow down your search and find relevant sources more efficiently.

Explore citation lists : Look for relevant sources in the reference lists of articles and papers you have already found. This can lead you to additional sources that are highly relevant to your research.

Consider different publication types : Apart from academic journals, consider including books, reports, theses, and dissertations in your literature review. These sources can provide valuable insights and perspectives on your topic.

Evaluating the credibility of the sources

It is crucial to evaluate the credibility and reliability of the sources you include in your literature review. Here are some factors to consider when assessing the credibility of a source:

Author’s expertise : Check the credentials and expertise of the author(s) of the source. Look for their affiliations, qualifications, and previous research experience in the field.

Publication venue : Consider the reputation and impact factor of the journal or conference where the source was published. High-quality venues often have a rigorous peer-review process, ensuring the reliability of the research.

Currency of the source : Ensure that the source is up-to-date and reflects the current state of research in the field. This is particularly important in rapidly evolving areas of study.

Peer-reviewed sources : Prefer sources that have undergone a peer-review process. Peer-reviewed articles are evaluated by experts in the field, ensuring the quality and validity of the research.

Organizing and summarizing the literature

Once you have gathered relevant sources, it is essential to organize and summarize the literature effectively. Here are some steps to help you with this process:

Create a citation database : Maintain a database or spreadsheet to keep track of the sources you have found. Include important details such as author names, publication year, title, and relevant notes.

Identify key themes and subtopics : Analyze the literature to identify common themes and subtopics that emerge from the sources. This will help you organize your survey paper and provide a logical flow of ideas.

Summarize the main findings : Write concise summaries of the main findings and key points from each source. Focus on the aspects that are most relevant to your research question or objective.

Identify gaps and controversies : Pay attention to any gaps or controversies in the literature. These can be areas where further research is needed or where different studies present conflicting results.

By following these steps, you can conduct a comprehensive literature review that forms the foundation of your survey paper. Remember to critically analyze and synthesize the information from various sources to provide a balanced and informative overview of the topic.

Outlining the Structure

When writing a survey paper, it is crucial to have a well-structured outline that guides the flow of your content. A clear and organized structure not only helps you present your ideas effectively but also makes it easier for readers to navigate through your paper. In this section, we will discuss the key components of outlining the structure of a survey paper.

The introduction sets the stage for your survey paper and provides essential background information to the readers. It should capture their attention and clearly state the research question or objective of your paper.

Background information : Start by providing a brief overview of the topic and its significance in the field. This helps readers understand the context and relevance of your survey paper.

Research question/objective : Clearly state the main research question or objective that your paper aims to address. This helps readers understand the purpose and focus of your survey.

The main body of your survey paper should be well-organized and structured to present your findings and analysis in a coherent manner. Consider the following points when outlining the main body:

Subtopics and their organization : Identify the key subtopics or themes that you will cover in your survey. These subtopics should be logically organized to provide a smooth flow of ideas. You can use headings and subheadings to clearly indicate the different sections of your paper.

Inclusion of relevant studies and findings : Within each subtopic, include relevant studies, research papers, and findings that contribute to the understanding of the topic. Make sure to cite and reference these sources properly to give credit to the original authors.

The conclusion of your survey paper should summarize the key points discussed in the main body and provide insights for future research directions. Consider the following elements when outlining the conclusion:

Summary of key points : Provide a concise summary of the main findings and insights from your survey. This helps readers grasp the main takeaways from your paper.

Future research directions : Discuss potential areas for further research or gaps that need to be addressed in the field. This encourages readers to explore new avenues and continue the scholarly conversation.

Having a well-structured outline for your survey paper ensures that you cover all the necessary components and present your ideas in a logical and coherent manner. It helps you stay focused and organized throughout the writing process.

Remember to review and revise your outline as needed to ensure that it aligns with the specific requirements and preferences of your survey paper. A well-structured survey paper not only enhances your credibility as a researcher but also contributes to the academic community’s knowledge and understanding of the topic.

Writing the Survey Paper

Writing a survey paper requires careful planning and organization to ensure that the information is presented in a clear and coherent manner. In this section, we will discuss the key steps involved in writing a survey paper.

The introduction of a survey paper plays a crucial role in capturing the reader’s attention and setting the tone for the rest of the paper. It should begin with an engaging opening statement that highlights the importance of the topic. The research question or objective should be clearly stated to provide a roadmap for the paper.

The main body of the survey paper should present a coherent flow of ideas that addresses the research question or objective. It is important to organize the content in a logical manner, using subheadings to divide the paper into sections. Each subtopic should be discussed in detail, providing a comprehensive overview of the existing literature.

When discussing previous studies and findings, it is essential to properly cite and reference the sources. This not only gives credit to the original authors but also adds credibility to the survey paper. Using a consistent citation style throughout the paper is important to maintain uniformity.

The conclusion of the survey paper should summarize the key findings and provide a concise overview of the main points discussed in the main body. It is an opportunity to highlight the significance of the research and its implications for future studies. Recommendations for further research can also be included to encourage future exploration of the topic.

Editing and Proofreading

Once the survey paper is written, it is crucial to thoroughly edit and proofread the content. This involves checking for grammar and spelling errors to ensure clarity and professionalism. It is also beneficial to seek feedback from peers or mentors to gain different perspectives and identify areas for improvement.

Formatting and Presentation

Proper formatting and presentation are essential for a well-structured survey paper. Following the required citation style is crucial to maintain consistency and adhere to academic standards. Headings, subheadings, and paragraphs should be properly formatted to enhance readability. Additionally, including tables, figures, and graphs can help illustrate complex information and enhance the overall presentation of the paper.

Finalizing the Survey Paper

Before submitting the survey paper, it is important to review the overall structure and content. This involves making necessary revisions and improvements to ensure the paper is coherent and cohesive. Proofreading the final version is crucial to eliminate any remaining errors and ensure a polished final product.

In conclusion, writing a survey paper requires careful planning, organization, and attention to detail. By following the steps outlined in this section, you can effectively write a survey paper that contributes to the existing body of knowledge in your field. Mastering the art of writing survey papers will not only enhance your academic research skills but also establish you as a knowledgeable and credible researcher.

Additional Resources:

- Recommended books and articles on survey paper writing

Online tools and platforms for organizing research

References:

List of sources cited in the blog post

Editing and proofreading are crucial steps in the writing process. They ensure that your survey paper is polished, error-free, and effectively communicates your ideas. Here are some essential tips to help you edit and proofread your survey paper effectively:

Checking for grammar and spelling errors

Use grammar and spell-check tools : Utilize grammar and spell-check tools like Grammarly or Microsoft Word’s built-in spell checker to identify and correct any grammatical or spelling errors in your survey paper.

Read your paper aloud : Reading your paper aloud can help you identify awkward sentence structures, grammatical errors, and spelling mistakes that you may have missed while reading silently.

Proofread multiple times : Proofreading is not a one-time task. It is essential to proofread your survey paper multiple times to catch any errors that may have been overlooked during previous rounds of editing.

Ensuring clarity and coherence

Check for clarity of ideas : Ensure that your ideas are presented clearly and concisely. Avoid using jargon or overly complex language that may confuse your readers. Use simple and straightforward language to convey your message effectively.

Maintain coherence and logical flow : Ensure that your survey paper has a logical flow of ideas. Each paragraph should connect smoothly to the next, and there should be a clear progression of thoughts throughout the paper. Use transition words and phrases to guide your readers through the different sections of your survey paper.

Eliminate redundant or irrelevant information : Review your survey paper to identify any redundant or irrelevant information. Remove any content that does not contribute to the overall purpose or argument of your paper. This will help streamline your paper and make it more focused and concise.

Seeking feedback from peers or mentors

Get a fresh pair of eyes : Ask a peer or mentor to review your survey paper. They can provide valuable feedback on areas that may need improvement, such as clarity, organization, or the overall structure of your paper.

Consider different perspectives : When seeking feedback, consider the perspectives of your reviewers. They may offer insights or suggestions that you may not have considered, helping you enhance the quality of your survey paper.

Incorporate feedback effectively : Take the feedback you receive into account and make necessary revisions to your survey paper. Be open to constructive criticism and use it to refine your paper further.

Remember, editing and proofreading are essential steps in the writing process. They help ensure that your survey paper is well-written, error-free, and effectively communicates your research findings. By following these tips, you can enhance the quality and clarity of your survey paper, making it more impactful and engaging for your readers.

Formatting and presentation play a crucial role in the overall quality and readability of a survey paper. Proper formatting ensures that the information is organized and presented in a clear and visually appealing manner. In this section, we will discuss the key aspects of formatting and presentation that you should consider when writing your survey paper.

Following the required citation style

One of the first things you need to consider when formatting your survey paper is the citation style required by your academic institution or the journal you are submitting to. Common citation styles include APA, MLA, and Chicago. Each style has specific guidelines for citing sources, formatting references, and creating in-text citations. It is important to familiarize yourself with the specific requirements of the chosen citation style and consistently apply it throughout your paper.

Properly formatting headings, subheadings, and paragraphs

Headings and subheadings are essential for organizing the content of your survey paper and guiding the reader through the different sections. When formatting headings and subheadings, it is important to follow a consistent hierarchy and formatting style. Typically, main headings are formatted in a larger font size and may be bold or italicized, while subheadings are formatted in a slightly smaller font size. This helps to visually distinguish between different levels of information and makes it easier for the reader to navigate through the paper.

In addition to headings and subheadings, proper formatting of paragraphs is also important. Each paragraph should focus on a single idea or topic and be well-structured with a clear topic sentence and supporting sentences. It is recommended to use a standard font such as Times New Roman or Arial, with a font size of 12 points. Additionally, paragraphs should be indented and have appropriate line spacing to enhance readability.

Including tables, figures, and graphs if necessary

Tables, figures, and graphs can be effective tools for presenting complex data or summarizing key findings in a visual format. When including these elements in your survey paper, it is important to ensure that they are properly labeled and referenced within the text. Tables should have clear column headings and be organized in a logical manner. Figures and graphs should have descriptive captions and be accompanied by a brief explanation in the text.

It is also important to consider the placement of tables, figures, and graphs within the paper. They should be inserted close to the relevant text and be easily accessible to the reader. If necessary, you can also refer to these elements in the text to provide further explanation or analysis.

Formatting and presentation are essential aspects of writing a high-quality survey paper. By following the required citation style, properly formatting headings and paragraphs, and including tables, figures, and graphs when necessary, you can enhance the overall readability and visual appeal of your paper. Remember to consistently apply these formatting guidelines throughout your survey paper to maintain a professional and polished appearance.

After going through the process of conducting a literature review, outlining the structure, writing the survey paper, and editing and proofreading it, you are now ready to finalize your survey paper. This stage involves reviewing the overall structure and content, making necessary revisions and improvements, and proofreading the final version.

Reviewing the overall structure and content

At this stage, it is crucial to review the overall structure and content of your survey paper. Ensure that the paper flows logically and coherently from the introduction to the conclusion. Check if the main body of the paper effectively addresses the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Make sure that each subtopic is adequately covered and that the inclusion of relevant studies and findings supports your arguments.

Making necessary revisions and improvements

During the finalization stage, it is common to identify areas that require revisions and improvements. Pay attention to the clarity and conciseness of your writing. Revise sentences or paragraphs that may be confusing or convoluted . Ensure that your arguments are well-supported by the literature and that you have properly cited and referenced all sources. Eliminate any redundant or irrelevant information that may distract readers from the main points of your survey paper.

Proofreading the final version

Proofreading is a crucial step in finalizing your survey paper. Check for grammar and spelling errors that may have been overlooked during the editing process. Ensure that your paper adheres to the required citation style and that all references are correctly formatted. Read through your paper carefully to ensure clarity and coherence . It may be helpful to read your paper aloud or ask a colleague to review it for you. Their fresh perspective can help identify any remaining errors or areas that need improvement.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your survey paper is of high quality and ready for submission or publication. Finalizing your survey paper requires attention to detail and a commitment to producing a well-structured and well-written piece of academic research.