- Find People

- ScholarShip Home

- ECU Main Campus

- Honors College

AN ANALYSIS OF THE INFLUENCE OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS ON INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT

Display/Hide MLA, Chicago and APA citation formats .

- Political Science

xmlui.ArtifactBrowser.ItemViewer.elsevier_entitlement

83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best nuclear weapon topic ideas & essay examples, 📌 simple & easy nuclear weapon essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on nuclear weapon, ❓ research questions about nuclear weapons.

- Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb? In addition to unleashing catastrophic damage upon the people of Japan, the dropping of the bombs was the beginning of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the U.S.

- Means of Destruction & Atomic Bomb Use Politics This information relates to the slide concerning atomic energy, which also advocates for the participation of the Manhattan Project’s researchers and policy-makers in the decision to atomic bombing during World War II. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Truman’s Decision the Dropping an Atomic Bomb The operations planned for late 1945 and early 1946 were to be on mainland Japan, and the military fatalities on both sides, as well as civilian deaths, would have very certainly outweighed the losses caused […]

- Can a Nuclear Reactor Explode Like an Atomic Bomb? The fact is that a nuclear reactor is not designed in the same way as an atomic bomb, as such, despite the abundance of material that could cause a nuclear explosion, the means by which […]

- Ethics and Sustainability. Iran’s Nuclear Weapon The opponents of Iran’s nuclear program explain that the country’s nuclear power is a threat for the peace in the world especially with regards to the fact that Iran is a Muslim country, and its […]

- The Decision to Drop the Atom Bomb President Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a decision of unprecedented complexity and gravity and, without a doubt, the most difficult decision of his life.

- E. B. Sledge’s Views on Dropping the A-Bomb There is a pointed effort to present to the reader the reality of war in all its starkness and raw horror. However, in the case of a war veteran like E.B.

- The Atomic Bomb of Hiroshima The effects of the bombing were devastating; the explosion had a blast equivalent to approximately 13 kilotons of TNT. Sasaki says that hospitals were teaming with the wounded people, those who managed to survive the […]

- Middle East: Begin Doctrine and Nuclear Weapon Free Zone This happens to be the case despite the fact that many countries and different members of the UN have always been opposed to the validity and applicability of this foreign doctrine or policy.

- Atomic Bomb as a Necessary Evil to End WWII Maddox argued that by releasing the deadly power of the A-bomb on Japanese soil, the Japanese people, and their leaders could visualize the utter senselessness of the war.

- Nuclear Weapon Associated Dangers and Solutions The launch of a nuclear weapon will not only destroy the infrastructure but also lead to severe casualties that will be greater than those during the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks.

- Why the US Decided to Drop the Atomic Bomb on Japan? One of the most notable stains on America’s reputation, as the ‘beacon of democracy,’ has to do with the fact that the US is the only country in the world that had used the Atomic […]

- The Marshallese and Nuclear Weapon Testing The other effects that the Marshallese people suffered as a result of nuclear weapon testing had to do with the high levels of radiations that were released.

- Was the American Use of the Atomic Bomb Against Japan in 1945 the Final Act of WW2 or the Signal That the Cold War Was About to Begin Therefore, to evaluate the reasons that guided the American government in their successful attempt at mass genocide of the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, one must consider not only the political implications behind the actions […]

- Leo Szilard’s Petition on the Atomic Bomb The group of scientists who created the weapon of mass destruction tried to prevent the usage of atomic bombs with the help of providing the petition to the President.

- Atomic Audit: Nuclear Posture Review Michael notes that the use of Weapons of Mass Destruction, such as nuclear bombs, tends to qualify the infiltration of security threats in the United States and across the world.

- Why the US used the atomic bomb against Japan? There are two main reasons that prompted the United States to use the atomic bomb against Japan; the refusal to surrender by Japan and the need for the US to assert itself.

- The Use of Atomic Bomb in Japan: Causes and Consequences The reason why the United States was compelled to employ the use of a more lethal weapon in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan has been at the heart of many scholarly writings.

- The Tradition of Non Use of Nuclear Weapon It is worth noting that since 1945 the concept of non use of nuclear weapons have occupied the minds of scholars, the general public and have remain the most and single important issues in the […]

- Was it Necessary for the US to Drop the Atomic Bomb? When it comes to discussing whether it was necessary to drop atomic bombs on Japan’s cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945, it is important to take into account the specifics of geopolitical […]

- Iran and Nuclear Weapon However, whether world leaders take action or not, Iran is about to get the nukes, and the first target will be Israel followed by American and the rest of the world.

- An Analysis of the United States’ Nuclear Weapon and the Natural Resources Used to Maintain it

- The Rise Of The Nuclear Weapon Into A Political Weapon

- Iran: Nuclear Weapon and United States

- Military And Nuclear Weapon Development During The Cold War

- Nuclear Weapons And Responsibility Of A Nuclear Weapon

- The Trinity Project: Testing The Effects of a Nuclear Weapon

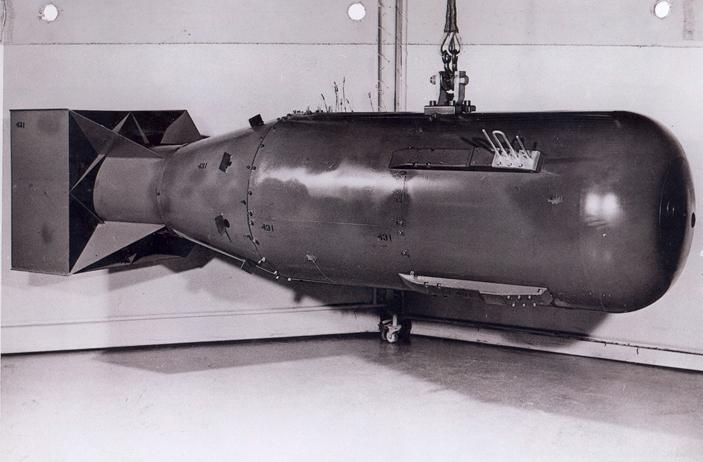

- An Analysis of the First Nuclear Weapon Built in 1945

- The Problem With Nuclear Weapons Essay – Nuclear weapon

- The Soviet Union Tested A Nuclear Weapon

- An Argument in Favor of Nuclear Weapon Abolition

- An Analysis of the Major Problem in Nuclear Weapon in World Today

- WWII and the Lack of Nuclear Weapon Security

- The Controversy Of Indivisible Weapons Composition – Cold War, Nuclear weapon

- The Never Ending Genocide : A Nuclear Weapon, Stirring Debate

- Nuclear Weapon Should Be Destroyed from All Countries

- Atomic Dragon: Chinese Nuclear Weapon Development and the Risk of Nuclear War

- The Nuclear Weapon Of Mass Destruction

- Nuclear Weapon Programmes of India and Pakistan: A Comparative Assessment

- Use of Hydroelectric Dams and the Indian Nuclear Weapon Problem

- Detente: Nuclear Weapon And Cuban Missile Crisis

- The Danger Of Indivisible Weapons – Nuclear weapon, Cool War

- Terrorism: Nuclear Weapon and Pretty High Likelihood

- The United States and Nuclear Weapon

- Nuclear Weapon And Foreign Policy

- The Environmental and Health Issues of Nuclear Weapon in Ex-Soviet Bloc’s Environmental Crisis

- Science: Nuclear Weapon and Supersonic Air Crafts

- Justified Or Unjustified: America Builds The First Nuclear Weapon

- The Controversial Issue of the Justification for the Use of Nuclear Weapon on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to End World War II

- Using Of Nuclear Weapon In Cold War Period

- Nuclear Weapon Funding In US Defense Budget

- Nuclear Weapon: Issues, Threat and Consequence Management

- An Analysis of Advantages and Disadvantage of Nuclear Weapon

- The Repercussion Of The North Korea’s Nuclear Weapon Threat On Globe

- A History of the SALT I and SALT II in Nuclear Weapon Treaties

- Free Hiroshima And Nagasaki: The Development And Usage Of The Nuclear Weapon

- The World ‘s First Nuclear Weapon

- The Effects Of Nuclear Weapon Development On Iran

- What Nuclear Weapons and How It Works?

- Can Nuclear Weapons Destroy the World?

- What Happens if a Nuclear Bomb Goes Off?

- Why Do Countries Have Nuclear Weapons?

- What Food Would Survive a Nuclear War?

- Why North Korea Should Stop It Nuclear Weapons Program?

- How Far Underground Do You Need to Be to Survive a Nuclear War?

- Why Nuclear Weapons Should Be Banned?

- Why Is There Such Focus on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, as Opposed to Other Kinds of Weapons?

- How Long Would It Take for Earth to Be Livable After a Nuclear War?

- What Are the Problems With Nuclear Weapons?

- How Have the Threats Posed by Nuclear Weapons Evolved Over Time?

- How Would the World Be Different if Nuclear Weapons Were Small Enough and Easy Enough to Make to Be Sold on the Black Market?

- How Big Is the Probability of Nuclear Weapons During Terrorism?

- Why Are Nuclear Weapons Important?

- Why Have Some Countries Chosen to Pursue Nuclear Weapons While Others Have Not?

- How Far Do You Need to Be From a Nuclear Explosion?

- Do Nuclear Weapons Keep Peace?

- Can a Nuclear Weapon Be Stopped?

- Do Nuclear Weapons Expire?

- What Do Nuclear Weapons Do to Humans?

- What Does the Case of South Africa Tell Us About What Motivates Countries to Develop or Relinquish Nuclear Weapons?

- Should One Person Have the Authority to Launch Nuclear Weapons?

- Does the World Need Nuclear Weapons at All, Even as a Deterrent?

- Will Most Countries Have Nuclear Weapons One Day?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, September 27). 83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/

"83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 27 Sept. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 27 September.

IvyPanda . 2023. "83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/.

- Nuclear Energy Essay Titles

- Atmosphere Questions

- Pollution Essay Ideas

- Hiroshima Topics

- Air Pollution Research Ideas

- Water Pollution Research Topics

- Conflict Research Topics

- North Korea Titles

- Global Issues Essay Topics

- Third World Countries Research Ideas

- US History Topics

- Cold War Topics

- Evacuation Essay Topics

- Hazardous Waste Essay Topics

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Nuclear weapons and international conflict: theories and empirical evidence.

- Daniel S. Geller Daniel S. Geller Daniel S. Geller is Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science at Wayne State University. He conducts research and teaches in the areas of International Politics, Defense Policy, and Foreign Policy. From 2000 through 2010 Dr. Geller served as a consultant to the U.S. Department of State, Office of Technology and Assessments, and in 2009 he was a member of a Senior Advisory Group to the U.S. Strategic Command on the Nuclear Posture Review. Dr. Geller was a Co-Principal Investigator on an NSF grant involving the expansion of the militarized interstate dispute database. He has published extensively in books, journals and edited collections on the subject of interstate war. His most recent books are Nations at War: A Scientific Study of International Conflict (Cambridge University Press) co-authored with J. David Singer and The Construction and Cumulation of Knowledge in International Relations (Blackwell, Ltd.) co-edited with John A. Vasquez.

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.347

- Published online: 27 July 2017

The balance of conventional military capabilities is intrinsic to understanding patterns of war among nations. However, cumulative knowledge relating to the effects of nuclear weapons possession on conflict interaction is largely absent. Framework is provided for analyzing the results of quantitative empirical research on this question and to identify any extant strong and consistent patterns in the interactions of states that can be associated with the possession of nuclear weapons.

Since 1945, a vast, sophisticated, and contradictory literature has developed on the implications of nuclear weaponry for patterns of international conflict and war. This theoretical and empirical work has principally focused on the conflict effects of these weapons for the interaction of nuclear-armed states, although a growing number of studies have explored the impact of a state’s possession of nuclear weapons on the behavior of nonnuclear opponents. Given the destructive capacity of these weapons and their questionable value for battlefield use, most of this work has concentrated on the requirements for successful deterrence. In categorizing the studies, some scholars note that “classical deterrence theory” derives from the Realist paradigm of international politics and subdivide this theory into two complementary strands: structural (or neorealist) deterrence theory and decision-theoretic deterrence theory. In contrast, other analysts choose to classify work on nuclear deterrence into three schools of thought: nuclear irrelevance; risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war; and the nuclear revolution. The essence of these divisions involves a debate about what the possession of nuclear weapons does for a state that controls them. Does the possession of these weapons affect the behavior of nuclear and nonnuclear opponents in disputes over contested values? Do the weapons impart political influence and hold military utility, or are they useless as tools for deterrence, compellence, or war?

- nuclear weapons

- crisis escalation

- nuclear war

- international conflict

- empirical international relations theory

Introduction

The balance of conventional military capabilities is intrinsic to understanding patterns of war among nations (Geller, 2000a ). However, cumulative knowledge relating to the effects of nuclear weapons possession on conflict interaction is largely absent. This article seeks to provide a framework for analyzing the results of quantitative empirical research on this question and to identify any extant strong and consistent patterns in the interactions of states that can be associated with the possession of nuclear weapons.

Since 1945 , a vast, sophisticated, and contradictory literature has developed on the implications of nuclear weaponry for patterns of international conflict and war. 1 This theoretical and empirical work has principally focused on the conflict effects of these weapons for the interaction of nuclear-armed states, although a growing number of studies have explored the impact of a state’s possession of nuclear weapons on the behavior of nonnuclear opponents. Given the destructive capacity of these weapons and their questionable value for battlefield use, most of this work has concentrated on the requirements for successful deterrence. In categorizing the studies, Zagare and Kilgour ( 2000 ), for example, note that “classical deterrence theory” derives from the Realist paradigm of international politics, and they subdivide this theory into two complementary strands: structural (or neorealist) deterrence theory and decision-theoretic deterrence theory. In contrast, Jervis ( 1979 , 1984 , 1988 ), among others, chooses to classify work on nuclear deterrence into three schools of thought: nuclear irrelevance; risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war; and the nuclear revolution. The essence of these divisions involves a debate about what the possession of nuclear weapons does for a state that controls them. Does the possession of these weapons affect the behavior of nuclear and non-nuclear opponents in disputes over contested values? Do the weapons impart political influence and hold military utility or are they useless as tools for deterrence, compellence, or war?

Nuclear strategy has principally concerned itself with the efficacy of nuclear weapons as a deterrent. One school of thought—nuclear revolution theory—characterized by the works of Brodie ( 1946 , 1959 , 1978 ), Waltz ( 1981 , 1990 , 1993 , 2003 ), and Jervis ( 1984 , 1988 , 1989a ), holds that the incredibly rapid and destructive effects of nuclear weapons creates a strong disincentive for nuclear-armed states to engage each other in disputes that might escalate to the level of war. The “nuclear revolution” means that nuclear weapons can deter aggression at all levels of violence and makes confrontations and crises between nuclear-armed states rare events. The maintenance of a nuclear second-strike capability is all that is required for a successful military deterrent force.

A second school of thought—risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war—emphasizes the problem of “risk” in confrontations between states in possession of nuclear weapons. The issue here is that, in disputes between nuclear-armed states, the use of nuclear weapons carries such enormous costs for both sides that any threat to use the weapons lacks inherent credibility. While allowing that a nuclear second-strike capability can deter a full-scale nuclear strike by an opponent, these analysts argue that states will manipulate the risk of dispute escalation and war for the purposes of deterrence and compellence (e.g., Gray, 1979 ; Kahn, 1962 , 1965 ; Schelling, 1960 , 1966 ). In this view, crises and brinkmanship tactics become surrogates for war in confrontations between nations in possession of nuclear weapons (Snyder & Diesing, 1977 ). Associated with this thesis is the concept of the “stability-instability paradox” (Snyder, 1965 ), whereby nuclear-armed states are secure in the deterrence of general nuclear war but are free to exploit military asymmetries (including strategic and tactical nuclear asymmetries as well as conventional military advantages) at lower levels of violence (e.g., Kissinger, 1957 ).

Yet another perspective holds nuclear weapons to be “irrelevant” as special instruments of either statecraft or war (Mueller 1988 , 1989 ). 2 In this argument, nuclear weapons are not substantially different in their deterrent effect from conventional military forces and, in John Mueller’s view, developed nations will not engage each other in either conventional or nuclear wars—having already witnessed the devastation that can be produced with both types of weaponry. A related argument holds that the possession of nuclear weapons provides little or no coercive advantage in confrontations with either nuclear-armed or nonnuclear states. A number of quantitative empirical studies of deterrence failures and successes (in both direct- and extended-deterrence cases) have produced results supportive of this thesis. Additionally, a notable formal mathematical study of deterrence by Zagare and Kilgour ( 2000 ) demonstrates that raising the costs of war above a certain threshold has no effect on deterrence stability. In this work, Zagare and Kilgour also maintain that, while nuclear weapons may increase the costs associated with a deterrent threat, they simultaneously decrease the credibility of the threat—and hence the stability of deterrence. These contrary effects serve to minimize the impact of nuclear weapons on effective deterrence. In short, nuclear and nonnuclear crises should exhibit the same patterns of escalation.

Over the past 35 years, large-scale quantitative empirical studies have attempted to generate evidence relating to these theories. Discussion of some of these works follows.

Nuclear Weapons and Patterns of International Conflict

The nuclear revolution.

The term “nuclear revolution” was coined by Robert Jervis ( 1989a , ch. 1), although the initial recognition of the alterations in patterns of international politics likely to be wrought by nuclear weapons should be credited to Bernard Brodie ( 1946 ). As Jervis has noted:

the changes nuclear weapons have produced in world politics constitute a true revolution in the relationships between force and foreign policy. The fact that neither [the United States nor the Soviet Union] can protect itself without the other’s cooperation drastically alters the way in which force can be used or threatened . . . The result is to render much of our prenuclear logic inadequate. As Bernard Brodie has stressed, the first question to ask about a war is what the political goal is that justifies the military cost. When the cost is likely to be very high, only the most valuable goals are worth pursuing by military means . . . What prospective . . . goals could possibly justify the risk of total destruction? (Jervis, 1989a , p. 13, 24)

Moreover, for Jervis ( 1989b ), that this destruction was essentially unavoidable under any plausible strategy constituted the essence of the nuclear revolution. Jervis ( 1989a , pp. 23–25) went on to enumerate changes in international politics directly attributable to the presence of nuclear weaponry, including the absence of war among the great powers, the declining frequency of great power crises, and the tenuous link between the conventional or nuclear balance among great powers and the political outcomes of their disputes. 3

Kenneth Waltz ( 1981 , 1990 , 1993 , 2003 , 2008 ) has been exceptionally prominent in developing and forwarding the thesis that nuclear weapons are a force for peace and that nuclear proliferation will lead to declining frequencies of war. Waltz argues that nuclear weapons are simply more effective in dissuading states from engaging in war than are conventional weapons:

In a conventional world, states going to war can at once believe that they may win and that, should they lose, the price of defeat will be bearable (Waltz, 1990 , p. 743). A little reasoning leads to the conclusions that to fight nuclear wars is all but impossible and that to launch an offensive that might prompt nuclear retaliation is obvious folly. To reach these conclusions, complicated calculations are not required, only a little common sense (Waltz in Sagan & Waltz, 1995 , p. 113). The likelihood of war decreases as deterrent and defensive capabilities increase. Nuclear weapons make wars hard to start. These statements hold for small as for big nuclear powers. Because they do, the gradual spread of nuclear weapons is more to be welcomed than feared. (Waltz in Sagan & Waltz, 1995 , p. 45)

Given this logic, evidence consistent with an absence of war or the use of force short of war between nuclear-armed states and few (or a declining frequency of) crises between nuclear powers would be supportive of the nuclear revolution thesis.

Empirical Evidence

A number of quantitative empirical studies have produced evidence relevant to the nuclear revolution thesis. In an early study of the effects of nuclear weapons possession, Bueno de Mesquita and Riker ( 1982 ) present both a formal mathematical model and an empirical test of deterrence success. The model assumes the possibility of nuclear war (i.e., the use of nuclear weapons) when nuclear asymmetry exists (only one side possesses nuclear weapons), but assumes the absence of nuclear war among nuclear-armed states. The model indicates a rising probability of nuclear war resulting from nuclear proliferation to the midpoint of the international system, where half of the states possess nuclear weapons, at which point any further proliferation results in a declining probability of nuclear war. When all nations possess nuclear weapons, the probability of nuclear war is zero. The supporting empirical analysis uses early Correlates of War (COW) Project Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) data, for the years 1945 through 1976 , for four classes of dyads: nuclear/nuclear, nuclear/nonnuclear with a nuclear ally, nuclear/nonnuclear, and nonnuclear/nonnuclear. The analysis examines the distribution of threats, interventions, and wars across the four dyad classes and indicates that the presence of a symmetric nuclear threat constrains conflict by reducing its likelihood of escalation to the level of war. The two classes of nuclear/nuclear and nuclear/nonnuclear with a nuclear ally have the highest probabilities of employing only threats and the lowest probabilities of engaging in interventions and wars. This evidence is consistent with the predictions of the nuclear revolution thesis. 4

Rauchhaus ( 2009 ) provides a multivariate analysis of factors associated with both militarized interstate disputes and wars for all dyads between 1885 and 2000 (MID database). The data set used in his study contains 611,310 dyad years, and tests were performed on time sections from 1885–1944 and 1945–2000 . He reports that in symmetric nuclear dyads (both states possess nuclear weapons) the odds of war drop precipitously. Rauchhaus concludes that Waltz and other nuclear revolution theorists find support for their thesis in the patterns uncovered by his study.

Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ) examine the relationship between the severity of violence in international crises and the number of states involved in the crises that possess nuclear weapons. Using data from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project for the years 1918 through 2000 , their results indicate that crises in which nuclear actors are involved are more likely to end without violence and that, as the number of nuclear-armed states engaged in crises increases, the probability of war decreases. This evidence is interpreted as supportive of the nuclear revolution thesis: the presence of nuclear weapon states in international crises has a violence-dampening effect due to the potential consequences of escalation and the use of nuclear force.

In a second study, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) hypothesize that nuclear weapons act as shields against aggressive behavior directed toward their possessors. Specifically, it is postulated that nuclear states will be constrained in engaging in aggressive actions toward other nuclear-armed powers. Data is drawn from the ICB Project for the years 1945 through 2000 , using directed dyads as the unit of analysis. The results indicate that nuclear opponents of other nuclear-armed powers are limited in their use of violent force. However, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a , p. 251) also note that the “restraining effect of nuclear weapons on violent aggression does not appear to affect the propensity for actors to engage each other in general crises, in contrast with the expectations of . . . the ‘nuclear revolution’ model. . .”

Additional results consistent with the nuclear revolution thesis are reported in a study by Sobek, Foster, and Robinson ( 2012 ). Using directed-dyad year with MID data for the period between 1945 and 2001 , the study examines the effects of efforts to develop nuclear weapons on the targeting of the proliferator in militarized disputes. Sobek et al. ( 2012 , p. 160) conclude that “. . .if a state . . . gains nuclear weapons, then the odds of being targeted in a militarized dispute falls.” States developing nuclear weapons are high-frequency targets in MIDs, but “. . .[t]argeting drops precipitously when [joint] acquisition is achieved” (Sobek et al., 2012 , p. 160).

However, Bell and Miller ( 2015 ) present evidence that is counter to the preceding studies. Using data collected by Rauchhaus ( 2009 ), they contend that nuclear dyads are neither more nor less likely to fight wars or engage in sub-war conflicts than are nonnuclear dyads. They argue that the evidence indicating a strong negative probability of war in symmetric nuclear dyads is due to the statistical model used by Rauchhaus, whereas the positive association for nuclear dyads and crisis frequency reported by Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) is due to selection effects (i.e., nuclear weapons possession is more a consequence rather than a cause of conflict).

The nuclear revolution thesis maintains that there should be a general absence of war or the use of force short of war among nuclear-armed states. In addition, there is the expectation of few (or a diminishing number of) crises in nuclear dyads, as the fear of escalation will exert a powerful constraint on aggressive behavior.

Bueno de Mesquita and Riker ( 1982 ) present compelling evidence that nuclear asymmetry or the absence of nuclear weapons on both sides of a conflict are more likely to be associated with war. In their data, between 1945 and 1976 , there were 17 cases of war between nonnuclear states, two cases of war in asymmetric nuclear dyads, and zero cases of war in either nuclear dyads or nuclear/nonnuclear dyads where the nonnuclear party had a nuclear-armed ally. Rauchhaus’s ( 2009 ) study also presents evidence that symmetric nuclear dyads are unlikely to engage in war. The article by Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ) reports results consistent with those of Bueno de Mesquita and Riker ( 1982 ). Specifically, crises ending in war are not uncommon for confrontations engaging nonnuclear states and for confrontations in which only one state possesses nuclear weapons. However, as the number of nuclear participants increases beyond one, the probability of full-scale war diminishes. Only the results of Bell and Miller ( 2015 ) stand in contrast with the findings on symmetric nuclear dyads and the probability of war. Similarly, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) show findings consistent with the nuclear revolution thesis: symmetric nuclear dyads engage in few crises where violence is the “preeminent” form of interaction. This conclusion is also supported by the findings reported by Sobek et al. ( 2012 ). However, Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ) and Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) also note that there appears to be no constraining effect produced by nuclear weapons on the occurrence of crises that exhibit lower levels of hostility in symmetric nuclear dyads.

Since the advent of nuclear weapons in 1945 , there has been one war between nuclear-armed powers: the Kargil War of 1999 involving India and Pakistan (Geller, 2005 , p. 101). This conflict remained at the conventional level and surpassed the threshold of 1,000 battle deaths set by the Correlates of War Project for classification as a war (Singer & Small, 1972 ; Small & Singer, 1982 ). However, Paul ( 2005 , p. 13) argues that, despite the conventional military asymmetry between India and Pakistan (in India’s favor) that existed at the time of the Kargil War, the development of Pakistani nuclear weapons actually permitted Pakistan to launch a conventional invasion of the disputed territory of Kashmir. As Paul explains, only in a long war could India mobilize its material superiority, but as a result of the development of Pakistani nuclear weapons, a long war becomes “inconceivable” without incurring the risk of nuclear escalation. Hence, Pakistan’s leaders were emboldened to initiate a conventional war behind the shield of their nuclear deterrent despite their conventional military inferiority. This sole case of conventional war between nuclear-armed states—and its facilitation by the risk of unacceptable escalation provided by nuclear weapons—stands in stark contradiction to the predictions of nuclear revolution theory. 5

These collective results provide only partial support for the nuclear revolution thesis. As the theory suggests, war between nuclear-armed states should be nonexistent or a very rare event. This prediction, to date (with one notable exception), has been upheld. However, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) report that symmetric nuclear dyads engage in an unexpectedly large number of crises—in contradiction to the predictions of nuclear revolution theory. This is an empirical question that will receive additional examination in the following section.

Risk Manipulation, Escalation, and Limited War

A second school of thought—risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war—finds its archetypal expression in the seminal work of Henry Kissinger ( 1957 ). According to this thesis (and counter to that of nuclear revolution theory), the possession of a nuclear second-strike capability may deter a nuclear attack by an opponent on one’s home territory, but not much else. Kissinger argued that the United States (and its NATO allies) required the ability to conduct successful combat operations at levels of violence below that of general nuclear war if the protection of Europe against Soviet aggression was a political goal. Some years later, Snyder ( 1965 ) discussed this as what was later termed the “stability-instability paradox.” The essence of the paradox was that stability at the level of general nuclear war permitted the exploitation of military asymmetries at lower levels of violence—including strategic (counterforce) and tactical nuclear wars as well as conventional forms of combat. The thesis that strategic nuclear weapons possessed little political or military utility other than deterring a nuclear attack on one’s home territory led to a number of works devoted to the analysis of tactics for coercive bargaining and limited war by Thomas Schelling ( 1960 , 1966 ), Herman Kahn ( 1960 , 1962 , 1965 ), and others. 6

As Snyder and Diesing ( 1977 , p. 450) maintain, the primary effect of the possession of nuclear weapons on the behavior of nuclear adversaries is the creation of new constraints on the ultimate range of their coercive tactics—a result of the extraordinary increase in the interval between the value of the interests at stake in a conflict and the potential costs of war. They note that before the advent of nuclear weapons, this interval was comparatively small and states could more readily accept the risk of war in a coercive bargaining crisis or engage in war in order to avoid the loss of a contested value. In contradistinction, given even small numbers of nuclear weapons in the stockpiles of states, it is far more difficult to conceive of an issue worth incurring the high risk of nuclear war, much less the cost of actually fighting one. 7

According to this thesis, a direct result of the constraints created by the presence of nuclear weapons has been the attempt by nuclear powers to control, in a more finely calibrated manner, the threat and application of force in disputes with other nuclear-armed states. These developments find theoretical and empirical expression in the concept of escalation , which is defined as the sequential expansion of the scope or intensity of conflict (Osgood & Tucker, 1967 , p. 127, 188). 8 In most standard formulations, escalation is conceived as a generally “controllable and reversible process,” 9 which a rational decision maker can employ in conflict situations as an instrument of state policy (Osgood & Tucker, 1967 , p. 188). Decision makers estimate the relative bargaining power of the rivals and engage in increasingly coercive tactics that are designed to undermine the opponent’s resolve. Controlled escalation occurs when each side is capable of inflicting major or unacceptable damage on the other but avoids this while attempting to influence the opponent with measured increases in the conflict level that incorporate the threat of possible continued expansion.

The measured application of force and the ability to control escalation in nuclear disputes are seen—by these strategic theorists—as indispensable for securing political values while minimizing risk and cost (Osgood & Tucker, 1967 , p. 137; Russett, 1988 , p. 284). A preeminent theorist in this school, Herman Kahn ( 1965 , p. 3), described escalation as “an increase in the level of conflict . . . [often assuming the form of] a competition in risk-taking or . . . resolve.” As this theory developed, conflict analysts elaborated the risks involved in the process and incorporated the manipulation of these risks as a possible tactic in one’s strategy. 10

Clearly, nuclear weapons have not altered the values at stake in interstate disputes (and the desire to avoid political loss), but rather have increased the rapid and immediate costs of war. As a result, in a severe conflict between nuclear powers, the decision maker’s dilemma is to construct a strategy to secure political interests through coercive actions that raise the possibility of war without pushing the risk to an intolerable level. Some analysts argue that the solution to this problem has entailed an increase in the “threshold of provocation,” providing greater area of coercive maneuver in the threat, display, and limited use of force (Osgood & Tucker, 1967 , pp. 144–145; Snyder & Diesing, 1977 , p. 451). Hostile interaction between nuclear powers under this higher provocation threshold can range from verbal threats and warnings, to military deployments and displays, to the use of force in limited wars. Hence, in disputes between nuclear powers, it is argued that military force should be viewed as requisite but “potentially catastrophic power” that must be carefully managed and controlled within the bounds of reciprocally recognized constraints (Osgood & Tucker 1967 , p. 137).

It is frequently stated that the principal exemplar of this new form of competition is the local crisis. Obviously, crises have an extensive history in international politics, but the argument is made that the nuclear age has produced an expansion of steps on the escalation ladder and has intensified the maneuvering of nuclear rivals for dominant position in conflicts below the level of all-out war. For example, Snyder and Diesing note that:

the expanded range of crisis tactics in the nuclear era can be linked to a new conception of crises as surrogates for war, rather than merely dangerous incidents that might lead to war. . . [S]ince war is no longer a plausible option between nuclear powers, they have turned to threats of force and the demonstrative use of force short of war as a means of getting their way. The winner of the encounter is the one who can appear the most resolved to take risks and stand up to risks. (Snyder & Diesing, 1977 , pp. 455–456)

Given this logic, conflicts between nuclear powers should reveal different escalatory patterns than conflicts between states where only one side possesses nuclear arms, or conflicts where neither side possesses nuclear arms. Specifically, disputes between nuclear powers should evidence a greater tendency to escalate—short of war—than nonnuclear disputes or disputes, in which only one side possesses a nuclear capability.

Kugler ( 1984 ) presents an empirical test of classical nuclear deterrence theory: the study examines whether nuclear weapons are salient in preventing the initiation or escalation of war to extreme levels. The analysis focuses on crisis interactions involving the United States, the Soviet Union, and China (PRC) with the case set drawn from Butterworth ( 1976 ) and CACI (Mahoney & Clayberg, 1978 , 1979 ). The cases used in the analysis constitute 14 extreme crises where nuclear nations were involved and where nuclear weapons “played a central role” (Kugler, 1984 , p. 477). The results indicate that crises of extreme intensity diminish as the threat of nuclear devastation becomes mutual. In other words, as the capacity of actors to destroy each other with nuclear weapons increases, there is a tendency to decrease the intensity of conflict, and to settle those crises that reach extreme proportions by compromise. This suggests that deterrence of war through the symmetric possession of nuclear weapons is operative in the conflict dynamics of great-power crises.

As Siverson and Miller ( 1993 , pp. 86–87) note, the earliest systematic statistical work on the effect of nuclear weapons possession in the escalation of conflict is by Geller ( 1990 ). This study employs the Correlates of War (COW) Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) data covering 393 MIDs between 1946 and 1976 and uses the MID five-level dispute hostility index in coding the dependent variable. The results indicate that dispute escalation probabilities are significantly affected by the distribution of nuclear capabilities. Comparing the escalatory behavior of nuclear dyads with the escalatory behavior of nonnuclear dyads in militarized disputes, it is reported that symmetric nuclear disputes indicate a far greater tendency to escalate—short of war—than do disputes for nonnuclear pairs: disputes in which both parties possess nuclear weapons have approximately a seven times greater probability (0.238) of escalating of escalating than do disputes in which neither party possesses nuclear arms (0.032). The conclusion indicates that the presence of nuclear weapons impacts the crisis behavior of states, with disputes between nuclear states more likely to escalate, short of war, than disputes between nonnuclear nations.

Huth, Gelpi, and Bennett ( 1993 ) analyze 97 cases of great power deterrence encounters from 1816 to 1984 as a means of testing the explanatory power of two competing theoretical approaches to dispute escalation. Dispute escalation is defined as the failure of the deterrent policies of the defender. Deterrence failure occurs when the confrontation ends in either the large-scale use of force or defender capitulation to the challenger’s demands. For the post- 1945 period, the findings indicate that, for nuclear dyads, the possession of a nuclear second-strike capability by the defender substantially reduces the likelihood of the confrontation ending either in war or in capitulation by the defender. However, the possession of nuclear weapons in great power dyads does not deter the challenger from initiating militarized disputes.

Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ) examine the relationship between the severity of violence in crises and the number of states involved in the confrontations that possess nuclear weapons. Using data from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project, the study includes 434 international crises extending from 1918 through 2001 . The results indicate that symmetric nuclear dyads engage in an unexpectedly large number of crises—and that “crises involving nuclear actors are more likely to end without violence. . . [A]s the number of nuclear actors increases, the likelihood of war continues to fall” (Asal & Beardsley, 2007 , p. 140). The authors also note that their results indicate that there may be competing effects within nuclear dyads: specifically, that both sides will avoid war but engage in sub-war levels of escalatory behavior (Asal & Beardsley 2007 , p. 150, fn. 6).

Rauchhaus ( 2009 ) also attempts to test the effects of nuclear weapons possession on conflict behavior. The data are generated using the EUGene (v.3.203) statistical package for dyad years from 1885 through 2000 and for a subset period from 1946 through 2000 . 11 The findings indicate that, in militarized disputes, symmetric nuclear dyads have a lower probability of war than do dyads where only one nation possesses nuclear arms. Moreover, in dyads where there are nuclear weapons available on both sides (nuclear pairs), the findings indicate that disputes are associated with higher probabilities of crises and the use of force (below the level of war). The author suggests that the results support the implications of Snyder’s ( 1965 ) stability-instability paradox. The results are also supportive of the Snyder and Diesing ( 1977 ) contention that crises have become surrogates for war between nuclear-armed states where the manipulation of risk through coercive tactics is employed to secure political objectives.

A study by Kroenig ( 2013 ) provides similar results. Using an original data set of 52 nuclear crisis dyads drawn from the International Crisis Behavior Project for the years 1945 through 2001 , Kroenig codes the outcomes of nuclear crises against nuclear arsenal size and delivery vehicles, and the balance of political stakes in the crisis. He concludes “. . . that nuclear crises are competitions in risk taking, but that nuclear superiority—defined as an advantage in the size of a state’s nuclear arsenal relative to that of its opponent—increases the level of risk that a state is willing to run” (Kroenig, 2013 , p. 143), and hence its probability of winning the dispute without violence. These results support the contention that crises between nuclear-armed states tend to involve dangerous tactics of brinkmanship and tests of resolve.

Evidence consistent with the risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war thesis would include the presence of severe crises between nuclear powers that exhibit escalatory behavior short of unconstrained war but inclusive of the use of force. The limited conventional war of 1999 between India and Pakistan, initiated and carried out by Pakistan under the umbrella of its nuclear deterrent, is an extreme example of precisely this type of conflict interaction. It captures the logic of Snyder’s stability-instability paradox and incorporates, as well, descriptions by Schelling and by Kahn of the use of limited war (with the risk of greater violence to follow) as a means of persuading an adversary to relinquish a contested value.

Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) report that symmetric nuclear dyads engage in an unexpectedly large number of crises—a finding that is consistent with the Snyder and Diesing ( 1977 ) contention that crises have become surrogates for war among nuclear-armed states. Similarly, Huth, Bennett, and Gelpi ( 1992 ) note that, in great-power dyads, the possession of nuclear weapons by the defender does not deter dispute initiation by a nuclear-armed challenger, and that an outcome of either war or capitulation by the defender is unlikely. In findings not inconsistent with those of Huth et al., ( 1992 ), Kugler ( 1984 ) reports that (between 1946 and 1981 ), as the capacity of nuclear actors to destroy each other increases, there is a tendency to decrease the intensity of the conflict. Both Geller ( 1990 ) and Rauchhaus ( 2009 ), in large-scale quantitative empirical analyses of escalation patterns in nuclear, nonnuclear, and mixed (asymmetric) dyads, report that symmetric nuclear dyads are substantially more likely to escalate dispute hostility levels—short of war—than are nonnuclear pairs of states. In Geller’s study, the findings indicate that disputes in which both parties possessed nuclear weapons had approximately a seven times greater probability of escalation (0.238) than did disputes in which neither party possessed nuclear arms (0.032). Last, Kroenig ( 2013 ) demonstrates that confrontations between nuclear-armed states may be understood as competitions in risk taking and that an advantage in the size of one’s nuclear arsenal is associated with increased levels of risk acceptance and, hence, successful coercion.

These cumulative findings are strongly supportive of the risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war thesis on the effects of symmetric nuclear weapons possession. 12 Moreover, the case of the 1999 limited conventional war between India and Pakistan reflects both the logic of this school of thought as well as the patterns of escalation described in the large-scale quantitative studies of militarized disputes between nuclear-armed states.

Nuclear Irrelevance

The views of John Mueller are most commonly associated with the thesis of “nuclear irrelevance.” Mueller ( 1988 , 1989 ) makes the highly controversial argument that nuclear weapons neither defined the stability of the post-Second World War U.S.-Soviet relationship nor prevented a war between the superpowers; he also maintains that the weapons did not determine alliance patterns or induce caution in U.S.-Soviet crisis behavior. His contention is that the postwar world would have developed in the same manner even if nuclear weapons did not exist.

Mueller’s logic allows that a nuclear war would be catastrophic, but that nuclear weapons simply reinforced a military reality that had been made all too clear by World War II: even conventional war between great powers is too destructive to serve any conceivable political purpose. Moreover, the satisfaction with the status quo shared by the United States and the Soviet Union removed any desire for territorial conquest that might have led to conflict, as each superpower held dominance in its respective sphere of influence. Similarly, provocative crisis behavior was restrained by the fear of escalation—and although the presence of nuclear weapons may have embellished such caution, the mere possibility of fighting another conventional war such as World War II would have induced fear and restraint on the part of decision makers. In short, nuclear weapons may have enhanced Cold War stability, but their absence would not have produced a different world. Mueller closes his argument with the extrapolation that war among developed nations is obsolescent. It may simply be that, in the developed world, a conviction has grown that war among post-industrial states “would be intolerably costly, unwise, futile, and debased” (Mueller, 1988 , p. 78). In this sense, nuclear weapons lack deterrent value among developed states because—absent the incentive for war—there is nothing to deter.

In a related thesis, Vasquez ( 1991 ) holds that it is unlikely—given what is known about the complex conjunction of multiple factors in the steps to war—that any single factor, such as the availability of nuclear weapons, causes or prevents wars. He makes the nuanced argument, in discussing the long post-war peace between the United States and the Soviet Union, that:

There is little evidence to support the claim that nuclear deterrence has prevented nuclear war or that it could do so in the future, if severely tested . . . Nuclear war may have been prevented not because of deterrence, but because those factors pushing the United States and the USSR toward war have not been sufficiently great to override the risks and costs of total war (Vasquez, 1991 , p. 207, 214).

Of principal significance to Vasquez is the absence of a direct territorial dispute between the superpowers. Other factors that Vasquez believes contributed to the long peace include satisfaction with the status quo, the experience of the two world wars, the establishment of rules and norms of interaction between the superpowers, procedures for crisis management, and effective arms control regimes. 13

A second area of application for the nuclear irrelevancy thesis involves asymmetric dyads. Little has been written about the effects of nuclear weapons on the patterns of serious disputes where this technology is possessed by only one side. However, what has been written suggests that in these types of conflicts nuclear weaponry may lack both military and psychological salience. For example, Osgood and Tucker ( 1967 , p. 158) and Blainey ( 1973 , p. 201) argue that tactical nuclear weapons are largely devoid of military significance in either Third World conflicts or insurgencies, where suitable targets for the weapons are absent. An additional disincentive to the use of nuclear weapons against a nonnuclear opponent is that it might be expected to increase the pressures for nuclear proliferation and to incite international criticism and denunciation of the nuclear state (Huth, 1988a , p. 428). It also has been suggested that a sense of fairness or proportionality contributes a moral aspect to the practical military and political inhibitions on using nuclear weapons against a nonnuclear opponent and that the set of these concerns has undermined the efficacy of nuclear power as a deterrent in asymmetric conflicts (Huth & Russett, 1988 , p. 38; Russett, 1989 , p. 184).

Moreover, Waltz ( 1967 , p. 222) and Osgood and Tucker ( 1967 , pp. 162–163) caution against exaggerating the differences due to nuclear weapons between contemporary and historical major power-minor power conflicts. Long before the advent of nuclear weapons, minor powers frequently defied or withstood great power pressure as a result of circumstances of geography, alliance, or an intensity of interests that the major power could not match.

In a similar argument, Jervis ( 1984 , p. 132) examines the logic of escalation in a losing cause (presumably a tactic relating directly to disputes between nuclear and nonnuclear states) and suggests that a threat to fight a war that almost certainly would be lost may not be without credibility—indeed, there may be compelling reasons for actually engaging in such a conflict. Specifically, if the cost of winning the war is higher to the major power than is the value at stake in the dispute, then the confrontation embodies the game structure of “Chicken.” Hence, even if war is more damaging to the minor power than to the major power, the stronger may still prefer capitulation or a compromise solution to the confrontation rather than engaging in the fight. In sum, Jervis ( 1984 , p. 135) argues that: “the ability to tolerate and raise the level of risk is not closely tied to military superiority . . . The links between military power—both local and global—and states' behavior in crises are thus tenuous.”

The third area of application for the nuclear irrelevancy thesis involves policies of extended deterrence. The efficacy of nuclear weapons for the purposes of extended deterrence was an issue of immense importance throughout the Cold War. In fact, the positions on whether American strategic nuclear weapons were sufficient to deter a Soviet-Warsaw Pact invasion of Western Europe or whether substantial conventional and tactical nuclear weapons were necessary for successful deterrence constituted a continuing debate for decades. Nuclear revolution theory contended that the U.S. strategic nuclear arsenal (with its ability to destroy the Soviet Union) was sufficient to induce caution and restraint on the part of the Soviet leadership. However, the strategists who formulated the stability-instability paradox argued that U.S. strategic nuclear weapons would deter a direct nuclear strike on the United States itself, but little else. According to this logic, for the successful extended deterrence of an attack on Europe, the United States and NATO required effective combat forces that could fight at the level of conventional war and even war with tactical nuclear weapons. Escalation dominance was required to sustain extended deterrence. Of course, extended deterrence policies existed long before the development of nuclear weapons and applied to any situation where a powerful defender attempted to deter an attack against an ally by threat of military response. The issue at hand is the effectiveness of a strategic nuclear threat in sustaining a successful extended deterrence policy. The nuclear irrelevancy position is that such weapons lack significance in extended deterrence situations.

In sum, the nuclear irrelevance thesis suggests that nuclear weapons have little salience in the interaction patterns of nuclear-armed dyads. Evidence consistent with this position would indicate that, for symmetric dyads, the possession of nuclear weapons or the nuclear balance does not affect crisis escalation, crisis outcomes, or dispute initiation patterns. In addition, if a set of practical, political, and ethical constraints has weakened the military advantage of possessing nuclear weapons in a serious dispute with a nonnuclear state, then the monopolization of a nuclear capability will not confer a bargaining edge to the nuclear-armed state in an asymmetric crisis. The nuclear irrelevance school would also gain support in findings indicating the absence of substantive effects resulting from possession of nuclear weapons in extended deterrence situations.

In evaluating the empirical evidence regarding the nuclear irrelevance thesis, it is useful analytically to separate the studies into distinct categories: (a) findings involving the effects of nuclear weapons in nuclear-armed dyads; (b) findings involving the interaction patterns of nuclear-armed states against nonnuclear opponents; and (c) findings bearing on extended deterrence situations.

(a) Nuclear dyads . The examination of evidence relating to nuclear revolution theory upheld the prediction that, as the theory suggests, war between nuclear-armed states should be nonexistent or a very rare event (e.g., Asal & Beardsley, 2007 ; Bueno de Mesquita & Riker, 1982 ; Rauchhaus, 2009 ). The success of this prediction (with the exception of the 1999 Kargil War) serves as the principal finding in support of the nuclear revolution thesis. However, this finding holds negative implications for the validity of the nuclear irrelevancy thesis. In other findings counter to the patterns hypothesized by the nuclear irrelevancy thesis, Geller ( 1990 ) reports results that indicate that the distribution of nuclear capabilities affects the patterns of escalation in militarized interstate disputes, and that symmetric nuclear dyads show substantially higher dispute escalation probabilities, short of war, than do nonnuclear dyads. Rauchhaus’s ( 2009 ) findings mirror Geller’s. Similarly, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) note that the crisis behavior of symmetric nuclear dyads differs from that of asymmetric dyads. Only the work of Bell and Miller ( 2015 ) stands in opposition to this general pattern. Using data from Rauchhaus ( 2009 ), Bell and Miller ( 2015 , p. 83) contend that nuclear dyads do not exhibit conflict patterns distinct from nonnuclear dyads either in terms of war or sub-war militarized disputes.

However, other evidence relating to conflict behavior, crisis interaction patterns, or crisis outcomes that indicate that nuclear weapons were inconsequential in the disputes would support the contention that nuclear forces are irrelevant in symmetric dyads. For example, Blechman and Kaplan ( 1978 ) provide an empirical analysis of 215 incidents between 1946 and 1975 , in which the United States used its armed forces for political objectives. Their findings indicate that the strategic nuclear weapons balance between the United States and the Soviet Union did not influence the outcome of competitive incidents involving the two states (Blechman & Kaplan, 1978 , pp. 127–129). Instead, the authors maintain that the local balance of conventional military power was more important in determining the outcomes of the confrontations (Blechman & Kaplan, 1978 , p. 527).

Kugler ( 1984 ) presents an empirical test of nuclear deterrence theory by examining whether nuclear weapons are efficacious in preventing the initiation or escalation of crises to the level of war. The case set is 14 extreme crises between 1946 and 1981 involving the United States, the Soviet Union, and China. Of the 14 crises, five involved nuclear-armed dyads (a nuclear power on each side). He concludes that: “nuclear nations do not have an obvious and direct advantage over other nuclear . . . nations in extreme crises. Rather, conventional [military] capabilities are the best predictor of outcome of extreme crises regardless of their severity” (Kugler, 1984 , p.501).

In contrast to the findings by Blechman and Kaplan ( 1978 ) and Kugler ( 1984 ), a study by Kroenig ( 2013 ) provides different results. Using a data set of 52 nuclear crisis dyads ( 1945–2001 ) drawn from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project, Kroenig codes the outcomes of nuclear crises, nuclear arsenal size and delivery vehicles, and the balance of political stakes in the crisis. He concludes that nuclear superiority—defined as an advantage in the size of a state’s nuclear arsenal relative to that of its opponent—increases the level of risk that a state is willing to run and hence its probability of winning the dispute without violence (Kroenig, 2013 , p. 143).

Huth et al. ( 1992 ) examine militarized dispute-initiation patterns among great power rivalries between 1816 and 1975 as a means of testing a set of explanatory variables drawn from multiple levels of analysis. The principal focus of the study is to investigate the relationship between the structure of the international system and the initiation of great power disputes. However, the analysis does include a variable coded for the possession of nuclear weapons by the challenger’s rival. The findings indicate that the presence of defenders’ nuclear weapons does not deter challengers from initiating militarized disputes among great powers (Huth et al., 1992 , p. 478, 513).

Gartzke and Jo ( 2009 ) examine the effects of nuclear weapons possession on patterns of militarized dispute initiation using a sophisticated multivariate model and data drawn from the COW/MID database for directed dyads over the years 1946 through 2001 . Their findings indicate that nuclear weapons possession has little effect on dispute initiation behavior. The authors note that: “Instead, countries with security problems, greater interest in international affairs, or significant military capabilities are simultaneously more likely to fight and proliferate” (Gartzke & Jo, 2009 , p. 221). The relationship between nuclear weapons and MID initiation is rejected statistically: this finding applies to both symmetric (nuclear) and asymmetric (nuclear/nonnuclear) dyads.

(b) Asymmetric dyads . The nuclear irrelevancy school also maintains that the possession of nuclear weapons confers no bargaining advantage on the nuclear-armed power engaged in a confrontation with a nonnuclear state.

In a seminal study examining the effects of nuclear weapons on conflict interaction patterns, Organski and Kugler ( 1980 , pp. 163–164) identify 14 deterrence cases that occurred between 1945 and 1979 in which nuclear weapons could have been used. Seven of these cases involved a nuclear power in confrontation with a nonnuclear state (or a state with an ineffective nuclear force ). Their findings indicate that in only one case out of the seven did the nuclear-armed state win: “Nonnuclear powers defied, attacked, and defeated nuclear powers and got away with it” (Organski & Kugler, 1980 , p. 176). In the six cases that the nuclear power lost to a nonnuclear state, the winner was estimated to have conventional military superiority at the site of the confrontation (Organski & Kugler, 1980 , p. 177).

In a related study, Kugler ( 1984 ) isolates 14 cases of extreme crisis that occurred between 1946 and 1981 , in which nuclear weapons were available to at least one party in the dispute. Of these 14 cases, nine involved confrontations in which only one state had access to nuclear arms. In all nine cases, the outcomes of the crises favored the nonnuclear challenger. Once again, the balance of conventional military capabilities—not nuclear weaponry—provided the best predictor of crisis outcome (Kugler, 1984 , p. 501).

In an early large-scale study, Geller ( 1990 ) examines conflict escalation patterns in serious interstate disputes among nations with both symmetric and asymmetric types of weapons technology. This study employs the Correlates of War (COW) Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) data, inclusive of 393 MIDs between 1946 and 1976 , and uses the MID five-level dispute hostility index in coding the dependent variable. The findings indicate that, for asymmetric dyads (with only one state in possession of nuclear arms), the availability of nuclear force has no evident inhibitory effect on the escalation propensities of nonnuclear opponents. In fact, the findings show that in this class of confrontation, both nonnuclear dispute initiators and targets act more aggressively than do their nuclear-armed opponents. The summation suggests that in confrontations between nuclear and nonnuclear states, war is a distinct possibility, with aggressive escalation by the nonnuclear power probable. In such cases, it is concluded that the conventional military balance may be determinative of the outcome (Geller, 1990 , p. 307).

In two studies published in 1994 and 1995 , Paul employs the case study method to examine the dynamics of asymmetric war initiation by weaker powers. Paul ( 1994 ) analyzes six cases of war initiation by weaker states against stronger states: three of these cases (China/U.S. in 1950 ; Egypt/Israel in 1973 ; and Argentina/Great Britain in 1982 ) involve nonnuclear nations initiating wars against nuclear-armed opponents. Paul ( 1994 , p. 173) concludes that nuclear weapons appear to have limited utility in averting war in asymmetric dyads. He notes that, with either nuclear or conventional weapons, a significant military advantage may be insufficient to deter a weaker state that is highly motivated to change the status quo. In a more focused study, Paul ( 1995 ) discusses the possible reasons underlying the nonuse of nuclear weapons by nuclear-armed states against nonnuclear opponents. Here he analyzes two cases (Argentina/Great Britain in the Falklands War of 1982 and Egypt/Israel in the Middle East War of 1973 ) in which nonnuclear states initiated wars against nuclear opponents. Paul argues that in both cases nuclear retaliation by the targets was deemed highly improbable by the nonnuclear war initiators due to a combination of limited war goals and taboos (unwritten and uncodified prohibitionary norms) against the use of nuclear weapons.

Rauchhaus ( 2009 ) attempts to test the effects of nuclear weapons possession on conflict behavior for asymmetric as well as for symmetric dyads using data generated by the EUGene (v.3.203) statistical program for dyad years from 1885 through 2000 . The findings indicate that, for asymmetric (nuclear/nonnuclear) dyads (in comparison to symmetric dyads), there is a higher probability of war. Asymmetric dyads are also more likely to be involved in militarized disputes that reach the level of the use of force (Rauchhaus, 2009 , pp. 269–270). In short, the study produces results that hold in opposition to the view that conflict between nuclear and nonnuclear states will be limited. As Rauchhaus ( 2009 , p. 271) concludes: “nuclear asymmetry is generally associated with a higher chance of crises, uses of force, fatalities, and war.”

A study by Beardsley and Asal ( 2009b ) produces findings that stand in counterpoint to the main body of analyses on conflict in asymmetric dyads. This work examines the question of whether the possession of nuclear weapons affects the probability of prevailing in a crisis. The data are drawn from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project for directed dyads covering the years between 1945 and 2002 . The findings indicate that the possession of nuclear weapons provides bargaining leverage against nonnuclear opponents in crises: nuclear actors are more likely to prevail when facing a nonnuclear state (Beardsley & Asal, 2009b , p. 278, 289).

However, with regard to bargaining advantages that may be derived from the possession of nuclear weapons, Sechser and Fuhrmann ( 2013 ) argue (counter to Beardsley & Asal) that compellent threats based on nuclear force may lack credibility due to their indiscriminately destructive effects and the reputational costs that, presumably, would be associated with their use. Drawing on a new data set (Militarized Compellent Threats) containing 242 challenger-target dyads for the period 1918 to 2001 , they report findings indicating that “states possessing nuclear weapons are not more likely to make successful compellent threats [than nonnuclear states] . . . and that nuclear weapons carry little weight as tools of compellence” (Sechser & Fuhrmann, 2013 , p. 174).

An interesting corollary finding is presented by Narang ( 2013 ). Using data collected by Bennett and Stam ( 2004 ) to explore the conflict behavior of regional (non-superpower) nuclear actors from 1945 through 2001 , Narang finds little evidence supporting an existential deterrent effect for nuclear weapons against nonnuclear opponents. Rather, he concludes that the nuclear posture adopted by the nuclear-armed state is determinative of deterrence success, with an “asymmetric escalation” posture superior to either a “catalytic” or “assured destruction” posture in deterring conventional attacks with military force (Narang, 2013 , p. 280, 284–286).

(c) Extended deterrence . The logic of the nuclear irrelevancy thesis suggests that nuclear weapons should be of little salience in extended deterrence situations.

Huth defines deterrence as a policy that seeks to convince an adversary through threat of military retaliation that the costs of using military force outweigh any expected benefits. Extended deterrence is then defined by Huth ( 1988a , p. 424) as a confrontation between a defender and a potential attacker in which the defender threatens the use of military force against the potential attacker’s use of force against an ally (protégé) of the defender. There have been a large number of studies produced on the issue of the efficacy of extended nuclear deterrence—the majority of which report a body of consistent or complementary findings.

As noted in Harvey and James ( 1992 ), Bruce Russett’s ( 1963 ) analysis of 17 crises that occurred between 1935 and 1961 appears to be the first aggregate study of the factors associated with extended deterrence success and failure. Nine crisis cases involved defenders with a nuclear capability, and six of the nine cases resulted in successful extended deterrence. However, Russett draws no conclusions as to the independent effect of nuclear weapons on those outcomes. He does note that military equality on either the local (conventional) or strategic (nuclear) level appears to be a necessary condition for extended deterrence success.

Two studies published by Weede ( 1981 , 1983 ) also deal with the effectiveness of extended nuclear deterrence. Weede examines 299 dyads between 1962 and 1980 for evidence relating to patterns of extended deterrence success or failure. His findings are supportive of the position that nuclear weapons assist in producing extended deterrence success.

In a subsequent study, Huth and Russett ( 1984 ) increased the size of Russett’s ( 1963 ) sample set from 17 to 54 historical cases of extended deterrence from 1900 through 1980 . The findings indicate that the effect of nuclear weapons on extended deterrence success or failure is marginal. Of much greater import are the combined local conventional military capabilities of the defender and protégé; hence, conventional, rather than nuclear, combat power is associated with the probability of extended deterrence success.

In two related studies, Huth ( 1988a , 1988b ) examines 58 historical cases of extended deterrence and reports findings similar to those found in Huth and Russett ( 1984 ). Specifically, the possession of nuclear weapons by the defender did not have a statistically significant effect on deterrence outcomes when the target itself was a nonnuclear power. In addition, the ability of the defender to deny the potential attacker a quick and decisive conventional military victory on the battlefield was correlated with extended deterrence success.

Huth and Russett ( 1988 ) present an analysis of Huth’s ( 1988b ) 58 historical cases of extended deterrence success and failure. In this database, there were 16 cases of extended deterrence crises where defenders possessed nuclear weapons. The findings indicate that a defender’s nuclear capability was essentially irrelevant to extended deterrence outcomes; existing and locally superior conventional military forces were of much greater importance to deterrence success.

Huth ( 1990 ) produced another study based on the data set described in his 1988b book. In this study, he examines the effects of the possession of nuclear weapons by a defender only in extended deterrent crises not characterized by mutual assured destruction (i.e., where the potential attacker either does not possess nuclear weapons or does not possess a significant nuclear capability). He reports that, when the defender has an advantage in conventional forces, nuclear weapons do not play a significant role in the outcomes of extended deterrence confrontations (Huth, 1990 , p. 271).

In an unusual work, Carlson ( 1998 ) combines a formal mathematical model with an empirical test of escalation in extended deterrence crises. Using Huth’s ( 1988b ) data extending from 1885 to 1983 , the analysis examines the 58 cases of extended deterrence crises. Measures include the estimated cost-tolerance of both attackers and defenders. The findings indicate that low cost-tolerance challengers are less likely to escalate a crisis to higher levels of hostility when the defender possesses nuclear weapons.

Fuhrmann and Sechser ( 2014 ) report findings similar to those of Weede ( 1981 , 1983 ) and Carlson ( 1998 ), insofar as the independent extended deterrent effect of nuclear weapons is supported. Using Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) data for the years 1950 through 2000 , and controlling for the effects of contiguity, polity-type of challenger, power ratio, and nuclear status of challenger, they conclude that “formal defense pacts with nuclear states have significant deterrence benefits. Having a nuclear-armed ally is strongly associated with a lower likelihood of being targeted in a violent militarized dispute . . .” (Fuhrmann & Sechser, 2014 , p. 920).

The empirical evidence regarding the nuclear irrelevance thesis has been divided analytically into three distinct categories: (a) findings involving the effect of nuclear weapons in nuclear dyads; (b) findings involving the interaction patterns of nuclear-armed states against nonnuclear opponents; and (c) findings relating to extended deterrence situations.

Regarding Category “a”—the effect of nuclear weapons on conflict patterns in nuclear dyads—the results are mixed. According to the logic of the nuclear irrelevancy thesis, nuclear-armed dyads should show identical conflict patterns to nonnuclear dyads. This prediction is supported by the findings of Bell and Miller ( 2015 ). However, Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ), Bueno de Mesquita and Riker ( 1982 ), and Rauchhaus ( 2009 ) all note that empirical probabilities of war are far lower for nuclear dyads than for nonnuclear dyads. Moreover, Geller ( 1990 ) reports results indicating that the distribution of nuclear capabilities affects escalation patterns in militarized interstate disputes, and that symmetric nuclear dyads show substantially higher dispute escalation probabilities—short of war—than do nonnuclear dyads. Rauchhaus’s ( 2009 ) findings are identical to Geller’s. Similarly, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) note that the crisis behavior of symmetric nuclear dyads differs from that of asymmetric dyads. In sum, contrary to the predictions of the nuclear irrelevancy school, these findings suggest that patterns of war and crisis escalation differ among symmetric nuclear dyads, asymmetric dyads, and nonnuclear dyads.

Nevertheless, there is a body of evidence for nuclear dyads that supports the nuclear irrelevancy thesis; these findings focus on the effects of the nuclear balance on crisis outcomes and the effect of nuclear weapons on patterns of dispute initiation. Both Blechman and Kaplan ( 1978 ; with 215 incidents from 1946 to 1975 ) and Kugler ( 1984 ; five extreme crises between 1946 and 1981 ), report that the balance of nuclear forces in nuclear dyads was less significant in influencing the outcome of confrontations than was the local balance of conventional military capabilities. Only Kroenig’s ( 2013 ) work indicates a crisis bargaining advantage accruing to a state with nuclear superiority in symmetric nuclear dyads. With regard to dispute initiation, Huth et al. ( 1992 ) report a lack of salience regarding the availability of nuclear weapons for great powers and the initiation patterns of their militarized disputes. Gartzke and Jo ( 2009 ) similarly note that nuclear weapons show no statistically significant relationship to the initiation of militarized interstate disputes in either symmetric or asymmetric dyads. In sum, the findings of this subset of studies are consistent with the thrust of the nuclear irrelevancy thesis regarding both the effects of the nuclear balance on crisis outcomes and the effects of the availability of nuclear weapons on dispute initiation patterns.

Category “b”—focusing on the interaction patterns of nuclear-armed states against nonnuclear opponents—provides a second set of cumulative findings. Organski and Kugler ( 1980 ), Kugler ( 1984 ), Geller ( 1990 ), and Rauchhaus ( 2009 ) all conclude that the possession of nuclear weapons provides little leverage in the conflict patterns or outcomes of disputes in asymmetric dyads. Organski and Kugler ( 1980 ) note that, in six cases out of seven, nonnuclear states achieved their objectives in confrontations with nuclear-armed states. Kugler ( 1984 ) reports that in nine crises between nuclear and nonnuclear states, the outcomes in every case favored the nonnuclear party. In both studies, conventional military capabilities at the site of the confrontation provided the best predictor of crisis outcome.