- Skip to main navigation

- Skip to utility navigation

- Skip to main content

- Applicant Login

Search form

The wright institute.

- About Wright

- Admissions & Aid

- Clinical (PsyD) Program

- Counseling (MA) Program

- Clinical Services

- Dean's Greeting

- Program Mission Aims & Objectives

- Program Overview

- Field Placement Sequence

- Clinical Faculty

- Assessment Clinic

- Recovery Clinic

- The College Wellness Program

- The Curriculum

- Case Conference Series

- Foundation Series

- Assessment Series

- Intervention Series

- Sociocultural Issues Series

- Research Methods Series

- First Responders Psychology Certificate

- Health Psychology

- Portfolio Review & Qualifying Exam

- The Dissertation

- Academic Calendar

- Charles Alexander, PhD

- Ellen Balis, EdD

- Anita Barrows, PhD

- Calla Belkin, PsyD

- Kinshasa Bennett, PhD

- Dre Berendsen, PsyD

- Anne C. Bernstein, PhD

- Sarah Bharier, PsyD

- Elizabeth Bradshaw, PsyD

- Latoya Conner, PhD

- Karen Davison, PsyD

- Robert Deady, PsyD

- Emily Diamond, PsyD

- Laeeq Evered, PsyD

- Eric Freitag, PsyD

- Peter Goldberg, PhD

- Nathan Greene, PsyD

- Terri Huh, PhD

- Alicia Johnson, PsyD

- Mark Kamena, PhD

- Steve Kanofsky, PhD

- Daniela Kantorová, PsyD

- Diane Kaplan, PhD

- Julia Kasl-Godley, PhD

- Philip Keddy, PhD

- Anatasia S. Kim, PhD

- Stephanie Kuehn, PsyD

- Terry Kupers, MD

- Mary Lamia, PhD

- Hanna Levenson, PhD

- Beate Lohser, PhD

- Jessica Luiz, PsyD

- Sukie Magraw, PhD

- Katie McGovern, PhD

- Matthew McKay, PhD

- L. Deborah Melman, PhD

- Larry Miller, PhD

- Gilbert H. Newman, PhD

- Peter M. Newton, PhD

- Lynn O'Connor, PhD

- Luis Perez-Ramirez, PsyD

- Jayme Peta, PhD

- Becky Pizer, PsyD

- Erica Pool, PsyD

- Sudhanva Rajagopal, PsyD

- Jed Sekoff, PhD

- Pooja Sharma, PsyD

- Biing-Jiun Shen, PhD

- Dale M. Siperstein, PhD

- Veronique Thompson, PhD

- Allyson Troxel-Galang, PsyD

- Temre Uzuncan, PsyD

- Deanna van Ligten, PsyD

- Robert A. Vargas, PsyD

- Leon Wann, PsyD

- Patricia Wood, PhD

- K Wortman, PhD

- Kayoko Yokoyama, PhD

- Sydnie Yoo, PhD

- Post-Doctoral Placements

- Early Employment

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Student Admissions, Outcomes, and Other Data

- Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

- Pipeline to Advanced Degrees

- Student Groups

- Useful Links

- Transcripts & Certifications

The dissertation enables students to develop in-depth understanding of an important clinical problem, and advance their professional identity as scholarly clinicians and psychologists. The dissertation is an original, independent investigation or exposition of a topic relevant to clinical psychology. It may be an original study that contributes new information to the field, or a scholarly synthesis with original applications of existing information to a significant clinical problem.

Sample Dissertation Titles

- The Relationship Between Clinician Training and Treatment Outcomes of Clients in DBT Skills Group at the San Francisco DBT Center

- Adjustment to Disability for Individuals With Spinal Cord Injury: A Comparison of the Minority and Medical Models

- Exploring Clinical Psychology Doctoral Students' Attitudes Towards Adults With Substance Use Disorders

- A Qualitative Study of Therapists' Experiences Practicing Multicultural Psychotherapy

- Families in the ICU Conference: Conflict, Resolution, and the Impact on Decisions at the End of Life

- An Examination of the Relationships Between Conventional and Novel Assessments of Attention and Functional Outcomes in Patients with Unilateral Neglect

- Second Opinions: A Model of Supervision Drawn From Wilfred Bion's Concept of Container/Contained

- The Long-term Effects of Emotionally Focused Therapy Training on Knowledge, Competency, Self-Compassion, and Attachment Style

- Integrating Story Time into the Treatment of Children with Social Phobia

- Control Mastery Theory and Anti-Racism: Interviews with White Control Mastery Therapists about Anti-Racism as a Therapeutic Stance

- White Therapists Addressing White Racism in Treatment: A Theoretical Analysis and Integrative Treatment Model

- On the Process of Psychospiritual Development, Old Age, and the Narrative Theory Model of Personality Development

- What Has Theory Done for Me Lately?: A Qualitative Study of Therapists' Reasons for Preferring Their Theoretical Orientations

- Anger and Depression Among Incarcerated Juvenile Delinquents: A Pilot Intervention

- Eating Disorders in Gay Men: The Link to Shame and the Risk of Suicide

- South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission: A Reckoning of Psychology's Contribution

- Separation Guilt and Recidivism Among Incarcerated Mothers

- Grief and the Foreclosure of Hope: A Phenomenological Investigation of Violent Loss among Inner-City African American Women

- Memory Functions of Youth with Prodromal Schizophrenia

- Ethnic Role Guilt and Academic Underachievement of African American Students

- The Relationship Between Sensory Processing and Play in Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders

- The Serial Visuospatial Learning Test (SVLT): A Psychometric Study

- The In/visible Race in Multicultural Psychology Literature: A Recognition of Whiteness and Power

- Asian Sisters in Action: The Psychosocial Development of Asian American Female Adolescents

- Seeking Meaning from the Past: Examining the Psychological Effects of the Tule Lake Pilgrimage on Japanese American Former Internees and Their Descendants

- What are You? A Qualitative Study on Multiracial Identity Development

- Survivors of Torture and Survivors of Gender Persecution: A Comparative Study of Symptom Severities at Intake

Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology Program

- Program Overview

- UC San Diego

- JDP Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) Committee

- Program Committees

- Student Council

- SDSU Psychology Clinic

- Program Administration

- Program Faculty

- Practicum Supervisors

- Doctoral Students

- Degree Learning Outcomes

- Major Areas of Study

- Clinical Practicum

- Course Catalog

- Facilities & Centers

- Research and Clinical Training

- Student First-Authored Publications

- Selection Process

- What We Consider for a Competitive Application

- How to Apply

- Faculty Mentorship

- Financial Support

- Admission FAQs

- Student Admissions, Outcome, and Other Data

- Basic Needs Resources

- Community/Cultural Centers

- Financial Aid & Scholarships

- Graduate Affairs

- Graduate Housing

- Student Disability Centers

- Student Health & Well-Being

- Student Handbook Table of Contents

- Mentor-Student Guide

- Registration

- Classes / Sample Curriculum

- Cognitive Psychology Requirement

- Statistics and Research Design

- Emphasis in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology

- Emphasis in Quantitative Methods

- Master of Science in Clinical Psychology

- Master of Public Health

- Class Attendance

- Transcripts

- Change in Major Area of Study

- Waiving Courses

- Grounds for Dismissal

- Student Records

- Program Milestone Checklist/Timelines

- Guidance Committee

- Second Year Project

- Clinical Comprehensive Exam

- Behavioral Medicine Comprehensive Exam

- Experimental Psychopathology Comprehensive Exam

- Neuropsychology Comprehensive Exam

- Dissertation

- Advancement to Candidacy

- After Graduation

- Student Funding

- Tuition and Fees

- Establishing Residency

- International Students

- Financial Aid

- Incentive Awards & Program Support

- Travel Funds

- Ethical Standards/Professional Behavior

- Where Do You Go When You Have A Problem, Question, Concern, or Complaint?

- Policy on Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

- Representation of Your Affiliation

- Web page and blog policy

- Membership in APA

- Outside Employment

- Requests to Spend Time Off-Site

- Research Experience

- Human Subjects/IRB

- Practicum Placements

- Accruing Clinical Hours in the Context of Research Activities

- Supervision

- Tracking Clinical Hours

- Practicum Grades

- Policy on Working with Diverse Clients/Patients

- Prerequisites

- JDP Student Awards

- Student Portals

- Campus ID Cards

- E-Mail Accounts

- Change of Address

- Leave of Absence

- Second Year Project Cover Sheet

Dissertation Proposal Defense Announcement

- Final Dissertation Defense Announcement

- Spring Student Evaluation

- Individual Development Plan (IDP)

- MPH Interest Form

- JDP SharePoint

Dissertation Proposal

Dissertation expectations.

The dissertation is an original research project with the student as first author. It may take place within the context of an ongoing research program, but the student is responsible for conducting all phases of the project with support from his/her mentor(s) and Dissertation Committee. All dissertations must have IRB approval from both Universities; some may also require IRB approval from the VA or other agencies (refer to the Human Subjects/IRB webpage). Please discuss this with your mentor at the time you decide the topic of your dissertation.

Dissertations represent empirical studies. The dissertation can be a single document, or can be three first-authored manuscripts describing empirical studies and combined with an introduction and discussion (see 3-Paper Dissertation Option ).

Dissertations are expected to incorporate rigorous scientific design, including methods and analytic approaches appropriate to the aims of the dissertation, and with attention to the need for statistical power, reliability, validity, and replicability. Dissertations completed for the JDP are typically quantitative in analytic approach, or represent a combination of quantitative and qualitative analyses (i.e., mixed methods). A well-designed and well-executed qualitative dissertation may be acceptable, but students considering this approach should consult closely with their mentors and the Co-DCTs before proceeding.

(Approved by Steering Committee, Spring 2017)

TIMELINE: It is expected that you will have successfully defended your dissertation proposal on or before September 1st of the fall you plan to apply for internship. This means that all committee members have approved the final version of your dissertation proposal.

Guidelines for Preparing the Dissertation Proposal Document

Whether you intend to do a traditional or three-paper dissertation, for your proposal defense you need to prepare a dissertation proposal document that:

- thoroughly reviews the relevant scientific literature. This review should support and lead to your proposed hypotheses/aims;

- includes a detailed description of all proposed methods, and what data will result; and

- includes a detailed description of the data analytic procedures you will use to address each hypothesis/aim.

In some cases, students have written grant proposals (e.g., F31s) that essentially cover this same information. In this case, students can use modified/expanded versions of their grant proposals as their dissertation proposals. It is possible that the literature review, in particular, may need to be expanded beyond what is included in a grant proposal.

The dissertation proposal is distributed to the dissertation committee at least two weeks in advance of your proposal defense so that committee members can see that you have expertise in the literature in your chosen area, and they can carefully evaluate the proposed methods and analysis. Proposed methods and analysis are typically the central focus of the discussion at the proposal defense, as it is important that the student, dissertation chair(s), and all committee members are in agreement on how the dissertation will be carried out.

There are sometimes substantive changes to the dissertation proposal that are requested by committee members, and agreed to at the proposal defense. In this case, you should prepare a revised proposal document and/or a written summary explicitly detailing all changes, and circulate this among your committee for approval.

Dissertation Proposal Defense

Each student is required to pass an oral examination (the “proposal defense”) defending the proposed dissertation.

The proposal defense can be scheduled any time after completing two years of the program at full-time status and the second year project. The student must also be in good standing. There is no need to wait until the clinical or the emphasis comprehensive examinations are completed. In fact, we encourage students to propose dissertations early so that there is enough time to collect the data before going on internship.

The dissertation proposal defense is a public meeting. Although the proposal defense will be open to the public, final determination of the content, including “passing” the defense of the proposal, rests with the dissertation committee.

Circulate a copy of your dissertation proposal to your entire committee at least two weeks before your scheduled proposal defense date . Your dissertation committee must formally approve your dissertation proposal before you can go forward and complete the dissertation. Their approval is indicated by each member’s signature on the JDP-3 Form .

Committee Participation at Dissertation Proposal Defense:

Effective Fall Quarter 2022:

Per UC San Diego policy, the default method for the doctoral committee to conduct graduate examinations (doctoral qualifying examination [dissertation proposal] and final dissertation defense) is when the student and all members of the committee are physically present in the same room.

In rare circumstances, the student may submit a request for one committee member to participate remotely. These will only be approved in circumstances that prevent the committee member from participating in person. The following is the procedure for requesting an exception if needed:*

- Step 1) The student must first submit the exception request (including the name of the committee member and reason for the request) to their Dissertation Chair (and Co-Chair if applicable) for approval.

- Step 2) Once approved by the Dissertation Chair (and Co-Chair if applicable), the exception request must be submitted by email to BOTH JDP Co-Directors for final approval. Make sure to copy the Dissertation Chair (and Co-Chair if applicable) and both Program Coordinators on this request.

It is expected that there will be synchronous participation by all committee members in the scheduled proposal or final defense. If an unavoidable situation arises that affects a committee member’s ability to participate synchronously, the committee chair (or co-chairs) may decide how to proceed. The committee chair, or one co-chair, must participate synchronously in the scheduled proposal and final defense.

* Note: The UC San Diego Graduate Council will defer to the graduate programs (Department Chair or Program Director) to review requests for exceptions and to make decisions to allow remote participation.

To refer to UC San Diego’s Rules for Conducting Master’s & Doctoral Examinations go to:

https://grad.ucsd.edu/academics/progress-to-degree/committees.html#Rules-for-Conducting-Master’s-a

The dissertation proposal defense must be publicly announced to all Joint Doctoral Program faculty, students, and staff a minimum of two weeks’ before the defense date .

Please follow these instructions to prepare your announcement.

Dissertation Proposal Defense Announcement Template

Writing the Abstract:

The abstract (not including the announcement details), must be no longer than 350 words .

The most common error in writing the abstract is failure to include a brief but complete description of the research project. A typical abstract should include:

- the questions or hypotheses under investigation;

- the participants, specifying pertinent characteristics;

- the experimental method;

- planned data analytic approaches, including statistical significance levels; and

- the potential implications or applications

For 3-Paper dissertations : You must make it clear that you are proposing a 3-Paper dissertation and clearly list the 3 aims.

Note: The public announcement must occur at least two weeks prior to the scheduled defense date . Failure to meet this requirement may result in a forced delay of the dissertation defense to meet the two week minimum.

Getting Your Announcement Approved

The following is the procedure for getting the abstract and dissertation proposal announcement approved:

STEP 1: Approval of Abstract by Dissertation Chair

The student must first submit the abstract to their Dissertation Chair (and Co-Chair if applicable) for approval. After the student has made any necessary changes required and has final approval by the Dissertation Chair, the student can finalize the proposal announcement.

STEP 2: Approval of Proposal Announcement by a JDP Co-Director

The Dissertation Proposal Announcement (see template above) must be submitted by email to BOTH JDP Co-Directors for final approval. Please make sure you copy your Dissertation Chair (and Co-Chair if applicable) on the email. The email should include the student’s cell phone (or other phone numbers) so they can be called to discuss any questions or concerns the JDP Co-Directors may have; failure to be readily available by phone or email may delay the approval process.

Response to the initial request to review the proposal announcement (including the abstract) should be within a day or two. If either JDP Co-Director does not respond within a couple of days, please contact the respective offices to ensure that they are in town.

The JDP Co-Director(s) may ask you to make changes in the abstract. These requests will be sent to both you and your Dissertation Chair. The public announcement will not be sent out until one of the Co-Director(s) gives final approval.

STEP 3: Submitting the Approved Dissertation Proposal Announcement for Distribution

Once your proposal announcement has been approved by one of the JDP Co-Directors, it is ready to be sent for distribution. Please follow the guidelines listed below when submitting the proposal announcement for distribution.

Formulate an email as follows:

To: Graduate Coordinator of UC San Diego and Program Coordinator of SDSU

Cc: Dissertation Chair; Co-Chair (if applicable); SDSU Co-Director; UC San Diego Co-Director

Subject: [Your name] Dissertation Proposal Defense

Email Body: Please find a copy of my dissertation proposal announcement attached. It has been approved by [Dissertation Chair name] and [JDP Co-Director name].

Attachment: The file should be a Word document, titled “Dissertation Proposal Defense [Your complete name] [date of the defense (e.g. October 10 2019)]”

Reminder: The public announcement must occur at least two weeks prior to the scheduled defense date . Failure to meet this requirement may result in a forced delay of the dissertation defense to meet the two week minimum.

Processing the JDP-3 Form

For detailed steps on how to initiate/complete the JDP-3 Form – Report of the Qualifying Examination and Advancement to Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical Psychology , please visit the JDP-3 Form webpage under Student Handbook/JDP Forms.

Last updated 3/04/2024

- Best Online Programs

- Best Campus Programs

- Behavior Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Counseling & Mental Health

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- General Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Industrial/Organizational

- Marriage Family Therapy

- Social Psychology

- Social Work

- Educational Psychologist

- Forensic Psychologist

- Clinical Psychologist

- Family Psychologists

- Marriage Family Therapist

- School Psychologist

- Social Psychologist

- School Counselors

- Neuropsychologist

- I/O Psychologist

- Sports Psychologist

- Addiction Counselor

- Mental Health Psychologist

- Counseling Psychologist

- Occupational Psychologist

- Child Psychiatrist

- Connecticut

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- West Virginia

- PsyD vs PhD

9 Tips for Your PsyD Dissertation

Though it’s not a requirement in every program, most Psy.D. tracks, regardless of their specialty, include a dissertation as part of what it takes to graduate and complete the program. Psy.D. dissertations are similar to dissertations in other graduate and doctoral programs, but completing one isn’t a simple or easy task.

Check out these tips to help guide you along the path to a successful dissertation process, from picking your topic to defending your work. Also, be sure to closely examine all dissertation requirements at your college, university or professional school. The specific process and prerequisites may vary.

#1 Make a Schedule

Depending on where you’re getting your Psy.D., your college or university may have a specific dissertation schedule set out for you before you even enroll. If so, be sure to stick with that, but if not, make sure you’ve read and understand what’s required for your dissertation. Your school should provide you with a dissertation handbook. Think about the classes you know you’ll need to take, and working backward from your graduation date, set some milestones for your dissertation, including when you’ll set your topic, make your proposal, do your research and more. Being specific and manageable with your milestones will help you stay on track.

#2 Read and Research Before Picking Your Topic

Consult with professionals in the field whom you respect, such as a favorite professor or mentor, about possible research topics. Take time to research and read the existing information and absorb it before you narrow your focus. Consult available literature in the subject, and further refine your possible focus areas.

#3 Pick a Topic You Care About But Don’t Get Too Personal

Formulating your central thesis around a subject that you personally are passionate about can help you maintain momentum during the long process of completing a dissertation. So be sure to focus your work in an area of psychology that excites you. That said, it’s important to pick a topic you have some personal passion for, but it’s best to avoid choosing one that hits too close to home. If you have personal experience in any aspect of psychology, it can be difficult to separate your own life from what’s revealed in your research, and if you aren’t at least somewhat objective, you could let your biases lead you in the wrong direction.

#4 Think About Your Previous Work

Ideally, you’d be able to select a topic that builds upon your previous research in the area, even if the topics aren’t tied closely together. Consider whether your previous academic research can serve as a bridge to a topic that doesn’t at first glance appear connected.

#5 Write As Much As You Can

Don’t worry about having every single bit of research or data before you begin writing. A dissertation is a massive project that can feel incredibly overwhelming when you’re attempting to get your arms around disparate pieces of literature to support your thesis. Writing nearly constantly can help you refine your arguments as you continue researching and finding new and interesting literature. Taking as little as 30 minutes a day can help ensure the data and research remains fresh on your mind.

#6 Write in Whatever Order You Wish

While you certainly should structure your Psy.D. dissertation in a specific way, and your school may have strict requirements on this, that doesn’t necessarily mean you have to write it in that order. Similarly to how movies are made, which is usually not in chronological order, consider approaching your dissertation by jumping around to different sections, and then going back and filling in the gaps. This is particularly helpful for those who are prone to writer’s block, as completing a section can be energizing and give you a sense of accomplishment that doesn’t come from staring at a blank page.

#7 Develop Thick Skin

Avoid being too precious about your work, including the research and the writing itself. Consult with as many trusted people as you can, including your dissertation adviser and committee, and take their notes in stride.

#8 Be Yourself and Stick to Your Values

Yes, there may be times when you get a piece of feedback that feels too negative or critical but is actually valid. However, there may be times when a colleague or adviser gives you a note that seems totally counter to the values that have informed your project to that point. If you are convinced in the importance of a point you’ve made, stick to your guns. This is your project, after all, and you are the one who must defend it.

#9 Practice, Practice, Practice

Researching and writing your dissertation is a huge task, but it’s only one part of the process of actually earning your Psy.D. Dissertation defense brings with it a whole host of new anxieties, and the best way to help curb these is to practice every chance you get. You should be prepared to speak in-depth on the genesis of your topic, your research methodology and results, as well as how you reached your conclusions. The goal isn’t to memorize some script, but you should consider what questions you’ll be asked from as many perspectives as possible.

According to the best research on the subject, about 80% of graduate students (in all fields) who complete their coursework are able to successfully get their dissertations done. So while it’s natural to feel overwhelmed at the start of the process, the reality is most students are able to get them done. If you can follow your school’s guidelines and keep to a manageable schedule, there’s no reason you can’t be among them.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

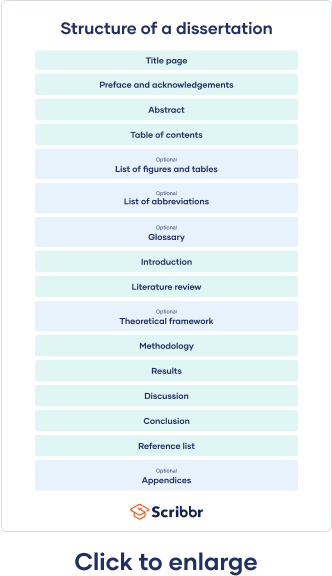

What Is a Dissertation? | Guide, Examples, & Template

A dissertation is a long-form piece of academic writing based on original research conducted by you. It is usually submitted as the final step in order to finish a PhD program.

Your dissertation is probably the longest piece of writing you’ve ever completed. It requires solid research, writing, and analysis skills, and it can be intimidating to know where to begin.

Your department likely has guidelines related to how your dissertation should be structured. When in doubt, consult with your supervisor.

You can also download our full dissertation template in the format of your choice below. The template includes a ready-made table of contents with notes on what to include in each chapter, easily adaptable to your department’s requirements.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

- In the US, a dissertation generally refers to the collection of research you conducted to obtain a PhD.

- In other countries (such as the UK), a dissertation often refers to the research you conduct to obtain your bachelor’s or master’s degree.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Dissertation committee and prospectus process, how to write and structure a dissertation, acknowledgements or preface, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review, methodology, reference list, proofreading and editing, defending your dissertation, free checklist and lecture slides.

When you’ve finished your coursework, as well as any comprehensive exams or other requirements, you advance to “ABD” (All But Dissertation) status. This means you’ve completed everything except your dissertation.

Prior to starting to write, you must form your committee and write your prospectus or proposal . Your committee comprises your adviser and a few other faculty members. They can be from your own department, or, if your work is more interdisciplinary, from other departments. Your committee will guide you through the dissertation process, and ultimately decide whether you pass your dissertation defense and receive your PhD.

Your prospectus is a formal document presented to your committee, usually orally in a defense, outlining your research aims and objectives and showing why your topic is relevant . After passing your prospectus defense, you’re ready to start your research and writing.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The structure of your dissertation depends on a variety of factors, such as your discipline, topic, and approach. Dissertations in the humanities are often structured more like a long essay , building an overall argument to support a central thesis , with chapters organized around different themes or case studies.

However, hard science and social science dissertations typically include a review of existing works, a methodology section, an analysis of your original research, and a presentation of your results , presented in different chapters.

Dissertation examples

We’ve compiled a list of dissertation examples to help you get started.

- Example dissertation #1: Heat, Wildfire and Energy Demand: An Examination of Residential Buildings and Community Equity (a dissertation by C. A. Antonopoulos about the impact of extreme heat and wildfire on residential buildings and occupant exposure risks).

- Example dissertation #2: Exploring Income Volatility and Financial Health Among Middle-Income Households (a dissertation by M. Addo about income volatility and declining economic security among middle-income households).

- Example dissertation #3: The Use of Mindfulness Meditation to Increase the Efficacy of Mirror Visual Feedback for Reducing Phantom Limb Pain in Amputees (a dissertation by N. S. Mills about the effect of mindfulness-based interventions on the relationship between mirror visual feedback and the pain level in amputees with phantom limb pain).

The very first page of your document contains your dissertation title, your name, department, institution, degree program, and submission date. Sometimes it also includes your student number, your supervisor’s name, and the university’s logo.

Read more about title pages

The acknowledgements section is usually optional and gives space for you to thank everyone who helped you in writing your dissertation. This might include your supervisors, participants in your research, and friends or family who supported you. In some cases, your acknowledgements are part of a preface.

Read more about acknowledgements Read more about prefaces

The abstract is a short summary of your dissertation, usually about 150 to 300 words long. Though this may seem very short, it’s one of the most important parts of your dissertation, because it introduces your work to your audience.

Your abstract should:

- State your main topic and the aims of your research

- Describe your methods

- Summarize your main results

- State your conclusions

Read more about abstracts

The table of contents lists all of your chapters, along with corresponding subheadings and page numbers. This gives your reader an overview of your structure and helps them easily navigate your document.

Remember to include all main parts of your dissertation in your table of contents, even the appendices. It’s easy to generate a table automatically in Word if you used heading styles. Generally speaking, you only include level 2 and level 3 headings, not every subheading you included in your finished work.

Read more about tables of contents

While not usually mandatory, it’s nice to include a list of figures and tables to help guide your reader if you have used a lot of these in your dissertation. It’s easy to generate one of these in Word using the Insert Caption feature.

Read more about lists of figures and tables

Similarly, if you have used a lot of abbreviations (especially industry-specific ones) in your dissertation, you can include them in an alphabetized list of abbreviations so that the reader can easily look up their meanings.

Read more about lists of abbreviations

In addition to the list of abbreviations, if you find yourself using a lot of highly specialized terms that you worry will not be familiar to your reader, consider including a glossary. Here, alphabetize the terms and include a brief description or definition.

Read more about glossaries

The introduction serves to set up your dissertation’s topic, purpose, and relevance. It tells the reader what to expect in the rest of your dissertation. The introduction should:

- Establish your research topic , giving the background information needed to contextualize your work

- Narrow down the focus and define the scope of your research

- Discuss the state of existing research on the topic, showing your work’s relevance to a broader problem or debate

- Clearly state your research questions and objectives

- Outline the flow of the rest of your work

Everything in the introduction should be clear, engaging, and relevant. By the end, the reader should understand the what, why, and how of your research.

Read more about introductions

A formative part of your research is your literature review . This helps you gain a thorough understanding of the academic work that already exists on your topic.

Literature reviews encompass:

- Finding relevant sources (e.g., books and journal articles)

- Assessing the credibility of your sources

- Critically analyzing and evaluating each source

- Drawing connections between them (e.g., themes, patterns, conflicts, or gaps) to strengthen your overall point

A literature review is not merely a summary of existing sources. Your literature review should have a coherent structure and argument that leads to a clear justification for your own research. It may aim to:

- Address a gap in the literature or build on existing knowledge

- Take a new theoretical or methodological approach to your topic

- Propose a solution to an unresolved problem or advance one side of a theoretical debate

Read more about literature reviews

Theoretical framework

Your literature review can often form the basis for your theoretical framework. Here, you define and analyze the key theories, concepts, and models that frame your research.

Read more about theoretical frameworks

Your methodology chapter describes how you conducted your research, allowing your reader to critically assess its credibility. Your methodology section should accurately report what you did, as well as convince your reader that this was the best way to answer your research question.

A methodology section should generally include:

- The overall research approach ( quantitative vs. qualitative ) and research methods (e.g., a longitudinal study )

- Your data collection methods (e.g., interviews or a controlled experiment )

- Details of where, when, and with whom the research took place

- Any tools and materials you used (e.g., computer programs, lab equipment)

- Your data analysis methods (e.g., statistical analysis , discourse analysis )

- An evaluation or justification of your methods

Read more about methodology sections

Your results section should highlight what your methodology discovered. You can structure this section around sub-questions, hypotheses , or themes, but avoid including any subjective or speculative interpretation here.

Your results section should:

- Concisely state each relevant result together with relevant descriptive statistics (e.g., mean , standard deviation ) and inferential statistics (e.g., test statistics , p values )

- Briefly state how the result relates to the question or whether the hypothesis was supported

- Report all results that are relevant to your research questions , including any that did not meet your expectations.

Additional data (including raw numbers, full questionnaires, or interview transcripts) can be included as an appendix. You can include tables and figures, but only if they help the reader better understand your results. Read more about results sections

Your discussion section is your opportunity to explore the meaning and implications of your results in relation to your research question. Here, interpret your results in detail, discussing whether they met your expectations and how well they fit with the framework that you built in earlier chapters. Refer back to relevant source material to show how your results fit within existing research in your field.

Some guiding questions include:

- What do your results mean?

- Why do your results matter?

- What limitations do the results have?

If any of the results were unexpected, offer explanations for why this might be. It’s a good idea to consider alternative interpretations of your data.

Read more about discussion sections

Your dissertation’s conclusion should concisely answer your main research question, leaving your reader with a clear understanding of your central argument and emphasizing what your research has contributed to the field.

In some disciplines, the conclusion is just a short section preceding the discussion section, but in other contexts, it is the final chapter of your work. Here, you wrap up your dissertation with a final reflection on what you found, with recommendations for future research and concluding remarks.

It’s important to leave the reader with a clear impression of why your research matters. What have you added to what was already known? Why is your research necessary for the future of your field?

Read more about conclusions

It is crucial to include a reference list or list of works cited with the full details of all the sources that you used, in order to avoid plagiarism. Be sure to choose one citation style and follow it consistently throughout your dissertation. Each style has strict and specific formatting requirements.

Common styles include MLA , Chicago , and APA , but which style you use is often set by your department or your field.

Create APA citations Create MLA citations

Your dissertation should contain only essential information that directly contributes to answering your research question. Documents such as interview transcripts or survey questions can be added as appendices, rather than adding them to the main body.

Read more about appendices

Making sure that all of your sections are in the right place is only the first step to a well-written dissertation. Don’t forget to leave plenty of time for editing and proofreading, as grammar mistakes and sloppy spelling errors can really negatively impact your work.

Dissertations can take up to five years to write, so you will definitely want to make sure that everything is perfect before submitting. You may want to consider using a professional dissertation editing service , AI proofreader or grammar checker to make sure your final project is perfect prior to submitting.

After your written dissertation is approved, your committee will schedule a defense. Similarly to defending your prospectus, dissertation defenses are oral presentations of your work. You’ll present your dissertation, and your committee will ask you questions. Many departments allow family members, friends, and other people who are interested to join as well.

After your defense, your committee will meet, and then inform you whether you have passed. Keep in mind that defenses are usually just a formality; most committees will have resolved any serious issues with your work with you far prior to your defense, giving you ample time to fix any problems.

As you write your dissertation, you can use this simple checklist to make sure you’ve included all the essentials.

Checklist: Dissertation

My title page includes all information required by my university.

I have included acknowledgements thanking those who helped me.

My abstract provides a concise summary of the dissertation, giving the reader a clear idea of my key results or arguments.

I have created a table of contents to help the reader navigate my dissertation. It includes all chapter titles, but excludes the title page, acknowledgements, and abstract.

My introduction leads into my topic in an engaging way and shows the relevance of my research.

My introduction clearly defines the focus of my research, stating my research questions and research objectives .

My introduction includes an overview of the dissertation’s structure (reading guide).

I have conducted a literature review in which I (1) critically engage with sources, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of existing research, (2) discuss patterns, themes, and debates in the literature, and (3) address a gap or show how my research contributes to existing research.

I have clearly outlined the theoretical framework of my research, explaining the theories and models that support my approach.

I have thoroughly described my methodology , explaining how I collected data and analyzed data.

I have concisely and objectively reported all relevant results .

I have (1) evaluated and interpreted the meaning of the results and (2) acknowledged any important limitations of the results in my discussion .

I have clearly stated the answer to my main research question in the conclusion .

I have clearly explained the implications of my conclusion, emphasizing what new insight my research has contributed.

I have provided relevant recommendations for further research or practice.

If relevant, I have included appendices with supplemental information.

I have included an in-text citation every time I use words, ideas, or information from a source.

I have listed every source in a reference list at the end of my dissertation.

I have consistently followed the rules of my chosen citation style .

I have followed all formatting guidelines provided by my university.

Congratulations!

The end is in sight—your dissertation is nearly ready to submit! Make sure it's perfectly polished with the help of a Scribbr editor.

If you’re an educator, feel free to download and adapt these slides to teach your students about structuring a dissertation.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

- Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

More interesting articles

- Checklist: Writing a dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

- Dissertation Binding and Printing | Options, Tips, & Comparison

- Example of a dissertation abstract

- Figure and Table Lists | Word Instructions, Template & Examples

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Dissertation or Thesis Proposal

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

- Operationalization | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

- Purpose and structure of an advisory report

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Shorten your abstract or summary

- Theoretical Framework Example for a Thesis or Dissertation

- Thesis & Dissertation Acknowledgements | Tips & Examples

- Thesis & Dissertation Database Examples

- Thesis & Dissertation Title Page | Free Templates & Examples

- What is a Dissertation Preface? | Definition & Examples

- What is a Glossary? | Definition, Templates, & Examples

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

- What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

What is your plagiarism score?

- How it works

Useful Links

How much will your dissertation cost?

Have an expert academic write your dissertation paper!

Dissertation Services

Get unlimited topic ideas and a dissertation plan for just £45.00

Order topics and plan

Get 1 free topic in your area of study with aim and justification

Yes I want the free topic

Clinical Psychology Dissertation Topics

Published by Owen Ingram at January 3rd, 2023 , Revised On August 11, 2023

Clinical psychology is a highly popular area of research for Masters and PhD nursing students. A well-thought-out and appropriate clinical psychology dissertation topic will address trending issues in the field of clinical psychology. You can develop a clinical psychology dissertation topic or idea by addressing a certain clinical experience.

If you are a nursing student looking for an intriguing topic in clinical psychology, you will find all the necessary information on this page. So without further ado, here is our selection of clinical psychology dissertation topics that you can choose from.

Related Links:

- Cognitive psychology dissertationtopics

- Educational psychology dissertation topics

- Counselling psychology dissertation topics

- Forensic-psychology-dissertation-topics

- Social Psychology Dissertation Topics

- Criminal Psychology Dissertation Ideas

- Neuro Psychology Dissertation Ideas

- Consumer Psychology Dissertation Ideas

- How to Identify and Differentiate Treatment-Resistant Depression?

- Understanding the Reasons People Join the Military

- Comprehensive Treatment for Postpartum Mood Disorders

- Using a Meaning-Making Process to Cope with Death

- What Kind of Relationship Do Teenagers Have with Video Games?

- Depression vs ADHD in Young Children

- Severe and Chronic Mental Illness and Life Quality

- Analyze the views of cancer patients suffering from advanced stages and their partners

- What therapy is available to treat panic attacks and anxiety disorders?

- What treatments and medications work best to treat addiction?

- Describe the many medical approaches to treating insomnia

- Analyze the efficacy of antidepressant medications in therapeutic interventions

- Describe the most successful depression treatments

- How does post-traumatic stress disorder develop?

- Antidepressants: are they addictive? Describe their efficacy and any possible negative effects

- Is behavioural therapy the ideal kind of care for offenders?

- How could psychology be used to treat persistent pain?

- What clinical and demographic factors cause individuals with obsessions and compulsions to have poor insight?

- The educational process for clinical psychologists who sought out personal therapy: a narrative assessment

- Dialysis patients’ psycho-social adjustment to their cases of renal failure and the resulting treatment

- Within a bio-psycho-social paradigm of a psychosis episode, the experiences connected to the psycho-social formulation

- The experiences and how they relate to eating habits in maturity

- A cognitive paradigm for assessing major depressive disorder

- The difficulties in communicating sexual dysfunction symptoms after a heart injury

- What are the main causes of adult anorexia?

- Examine major depressive disorder (MDD) in the context of cognitive theory

- Describe the communication obstacles caused by sexual dysfunction after cardiac trauma

- What relationship exists between adult eating habits and experiences?

- Investigate the idea of body image and identity in people who have had a heart or lung transplant

- Describe the clinical and demographic characteristics that predict insight in people with compulsions and obsessions

- Define schizophrenia and list possible treatments

- What drugs and therapies can be used to treat phobias and paranoia?

Hire Dissertation Specialist

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in an academic style

- Free Amendments and 100% Plagiarism Free – or your money back!

- 100% Confidential and Timely Delivery!

- Free anti-plagiarism report

- Appreciated by thousands of clients. Check client reviews

Something is mesmerising about the human mind. By writing clinical psychology-based dissertation papers, students can engage in formally conducting research on a variety of topics, including intellect, personality, addiction, relationship dynamics, and so on. Use these clinical psychology dissertation topics to start your academic research now!

If you are struggling with your dissertation and need a helping hand, you may want to read about our dissertation writing services.

Free Dissertation Topic

Phone Number

Academic Level Select Academic Level Undergraduate Graduate PHD

Academic Subject

Area of Research

Frequently Asked Questions

How to find clinical psychology dissertation topics.

To find Clinical Psychology dissertation topics:

- Study recent research in the field.

- Focus on emerging therapies or disorders.

- Address gaps in current literature.

- Consider ethical and practical aspects.

- Explore diverse populations or age groups.

- Seek topics aligning with your passion and expertise.

You May Also Like

Are you having trouble finding a good music dissertation topic? If so, don’t fret! We have compiled a list of the best music dissertation topics for your convenience.

Need interesting and manageable Facebook Marketing dissertation topics? Here are the trending Facebook Marketing dissertation titles so you can choose the most suitable one.

Need interesting and manageable coronavirus (covid-19) and global economy dissertation topics? Here are trending titles so you can choose the most suitable one.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

"Are you gonna publish that?" Peer-reviewed publication outcomes of doctoral dissertations in psychology

Spencer c. evans.

1 Clinical Child Psychology Program, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States of America

2 Department of Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States of America

Christina M. Amaro

Robyn herbert.

3 Department of Psychology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, United States of America

Jennifer B. Blossom

4 Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, United States of America

Michael C. Roberts

Associated data.

Data are publicly available from a variety of third party sources. A complete list of data sources has been included as a Supporting Information file, ' S1 File '.

If a doctoral dissertation represents an original investigation that makes a contribution to one’s field, then dissertation research could, and arguably should, be disseminated into the scientific literature. However, the extent and nature of dissertation publication remains largely unknown within psychology. The present study investigated the peer-reviewed publication outcomes of psychology dissertation research in the United States. Additionally, we examined publication lag, scientific impact, and variations across subfields. To investigate these questions, we first drew a stratified random cohort sample of 910 psychology Ph.D. dissertations from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. Next, we conducted comprehensive literature searches for peer-reviewed journal articles derived from these dissertations published 0–7 years thereafter. Published dissertation articles were coded for their bibliographic details, citation rates, and journal impact metrics. Results showed that only one-quarter (25.6% [95% CI: 23.0, 28.4]) of dissertations were ultimately published in peer-reviewed journals, with significant variations across subfields (range: 10.1 to 59.4%). Rates of dissertation publication were lower in professional/applied subfields (e.g., clinical, counseling) compared to research/academic subfields (e.g., experimental, cognitive). When dissertations were published, however, they often appeared in influential journals (e.g., Thomson Reuters Impact Factor M = 2.84 [2.45, 3.23], 5-year Impact Factor M = 3.49 [3.07, 3.90]) and were cited numerous times (Web of Science citations per year M = 3.65 [2.88, 4.42]). Publication typically occurred within 2–3 years after the dissertation year. Overall, these results indicate that the large majority of Ph.D. dissertation research in psychology does not get disseminated into the peer-reviewed literature. The non-publication of dissertation research appears to be a systemic problem affecting both research and training in psychology. Efforts to improve the quality and “publishability” of doctoral dissertation research could benefit psychological science on multiple fronts.

Introduction

The doctoral dissertation—a defining component of the Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree—is an original research study that meets the scientific, professional, and ethical standards of its discipline and advances a body of knowledge [ 1 ]. From this definition it follows that most dissertations could, and arguably should, be published in the peer-reviewed scientific literature [ 1 – 2 ]. For example, research participants typically volunteer their time and effort for the purposes of generating new knowledge of potential benefit; therefore, to breach this contract by not attempting to disseminate one’s findings is to violate the ethical standards of psychology [ 3 ] and human subjects research [ 2 , 4 ]. The nonpublication of dissertation research can also be detrimental to the advancement of scientific knowledge in other ways. Researchers may unwittingly and unnecessarily duplicate efforts from doctoral research when conducting empirical studies, or draw biased conclusions in meta-analytic and systematic reviews that often deliberately exclude dissertations. Many dissertations go unpublished due to nonsignificant and complicated results, exacerbating the “file drawer” problem [ 5 – 6 ]. Indeed, unpublished dissertations are rarely if ever cited [ 7 – 8 ].

The problem of dissertation non-publication is of critical importance in psychology. Some evidence [ 9 ] suggests that unpublished dissertations can play a key role in alleviating file drawer bias and reproducibility concerns in psychological science [ 10 ]. More broadly, the field of psychology—given its unique strengths, breadth, and diversity—poses a useful case study for examining dissertation nonpublication in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Like other scientific disciplines, many Ph.D. graduates in psychology may be motivated to revise and submit their dissertations for publication for the usual reasons offered by academic and research careers. However, other new psychologists might not pursue this goal for a variety of reasons. Those in professional and applied subfields may commit most or all of their working time to non-research activities (e.g., professional practice, clinical training) and have little incentive to seek publication. Even those in more research-oriented subfields increasingly take non-research positions (e.g., industry, consultation, teaching, policy work) or other career paths which do not incentivize publications. Negative graduate school experiences, alternative career pursuits, and personal or family matters can all be additional factors that may decrease the likelihood of publication. Moreover, it is typically a challenging and time-consuming task to revise a lengthy document for submission as one or more journal articles. Still, all individuals holding a Ph.D. in psychology have (in theory) produced an original research study of scientific value, which should (again, in theory) be shared with the scientific community. Thus, for scientific, ethical, and training reasons, it is important to understand the frequency and quality of dissertation publication in psychology.

There is an abundance of literature relevant to this topic, including student or faculty perspectives (e.g., [ 11 – 13 ]) and studies of general research productivity during doctoral training and early career periods (e.g., [ 14 – 19 ]). However, evidence specifically regarding dissertation publication is remarkably sparse and inconsistent [ 8 , 20 – 24 ]. This literature is limited by non-representative samples, biased response patterns, and disciplinary scopes that are either too narrow or too broad to offer insights that are useful and generalizable for psychological science. For example, in the only psychology-specific study to our knowledge, Porter and Wolfle [ 23 ] mailed surveys to a random sample of individuals who earned their psychology doctorates. Of 128 respondents, 59% reported that their dissertation research had led to at least one published article. Unfortunately, this study [ 23 ] and others (e.g., [ 8 ]) are now over 40 years old, offering little relevance to the present state of training and research in psychology. A much more recent and rigorous example comes from the field of social work. Using a literature searching methodology and a random sample of 593 doctoral dissertations in social work, Maynard et al [ 22 ] found that 28.8% had led to peer-reviewed publications. However, this estimate likely does not generalize to psychology and its myriad subfields. Thus, there is a need for more comprehensive, rigorous, and recent data to better understand dissertation publication in psychology.

Accordingly, the present study investigated the extent and nature of dissertation publication in psychology, specifically examining the following questions: (a) How many dissertations in psychology are eventually published in peer-reviewed journals? (b) How long does it take from dissertation approval to article publication? (c) What is the scientific impact of published dissertations (PDs)? and (d) Are there differences across subfields of psychology? Based on the literature and our own observations, we hypothesized that (a) a majority of dissertations in psychology would go unpublished; (b) dissertation publication would occur primarily during the first few years after Ph.D. approval, diminishing thereafter; (c) PDs would show evidence of at least moderate scientific influence via citation rates and journal metrics; and (d) professional/applied subfields (clinical, counseling, school/educational, industrial-organizational, behavioral) would yield fewer PDs than research-oriented subfields (social/personality, experimental, cognitive, neuroscience, developmental, quantitative).

Materials and methods

The dataset of psychology dissertations was obtained directly from ProQuest UMI’s Dissertations and Theses Database (PQDT), which is characterized as “the world’s most comprehensive collection of dissertations and theses. . . [including] full text for most of the dissertations added since 1997. . . . More than 70,000 new full text dissertations and theses are added to the database each year through dissertations publishing partnerships with 700 leading academic institutions worldwide” [ 25 ]. While international coverage varies across countries, PQDT’s repository is estimated to include approximately 97% of all U.S. doctoral dissertations [ 26 ], across all disciplines, institutions, and training models.

Upon request, PQDT provided a database of all dissertations indexed with the term “psychology” in the subject field during the year 2007. This resulted in a total population of 6,580 dissertations, which were then screened and sampled according to pre-defined criteria. The number of dissertations included at each stage in the sampling process is summarized in a PRISMA-style [ 27 ] flow diagram for the overall sample in Fig 1 , and broken down by subfield in Table 1 . Dissertations were excluded if written in a language other than English, for any degree other than Ph.D. (e.g., Psy.D., Ed.D.), or in any country other than U.S. The remaining dissertations were recoded for subfields based on the subject term classification in PQDT, with a few modifications (e.g., combining “neuroscience” and “biological psychology”). This left a remaining sample of 3,866 relevant dissertations, representing our population. This figure is approximately in line with the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Survey of Earned Doctorates [ 28 ] estimate that 3,276 research doctorates in psychology were granted during the year 2007, suggesting that PQDT could be slightly broader or more comprehensive in scope.

Note. PQDT = ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. a Categories of excluded dissertations are mutually exclusive, summing to 100%. b PQDT exclusion criteria were applied sequentially in the order presented; thus, the number associated with each exclusion criterion reflects how many were excluded from the sample that remained after the previous criterion was applied. Adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram [ 27 ].

Note. “Relevant dissertations” refers to all PQDT dissertations that satisfied screening criteria for inclusion. Dissertations were excluded in the eligibility stage based on the date of approval in the full text (see Fig 1 ). Rates of exclusion were not significantly different across subfields. Sampling weights for each subfield were calculated as the proportion in the population (relevant dissertations) divided by proportion in the full sample, after adjusting for the proportions within each subfield that were from excluded for ineligibility.

From this relevant population of 3,866, we drew a stratified random sample of 1,000 dissertations. This number was selected because it represented over 25% of the population and offered sufficient power to obtain 95% CIs less than ±3% for the overall proportion estimates (i.e., the primary research question). As shown in Table 1 , the sampling procedure was stratified by subfield using a formula that sought to balance (a) power for between-group comparisons, aiming to include ≥50 dissertations from each subfield; and (b) representativeness to the population, aiming to include ≥10% of the dissertations from each subfield. This resulted in subfield sample sizes ranging from 59 for general/miscellaneous (75.6% of relevant subfield population) to 179 for clinical (12.5% of relevant subfield population). Ninety (9.0%) dissertations were later found to be ineligible during the full-text review because the approval date was before or after the year 2007. This incongruence was partly explained by copyright or graduation dates differing from the dissertation year, and was not significantly different across subfields. The resulting final sample consisted of 910 dissertations, with subfield samples ranging from 52 (general/miscellaneous) to 159 (clinical). Because this study did not meet the definition of human subjects research, institutional review board approval was not required.

Search timeframe

We aimed to conduct prospective follow-up searches for PDs within a timeframe that was both (a) long enough to capture nearly 100% of PDs and (b) short enough for results to retain their relevancy to the current state of psychological science. Because the literature does not offer dissertation-publication “lag time” statistics for reference, we used the “half-life” of knowledge—i.e., the average time it takes for half of a body of knowledge to become disproven or obsolete [ 29 – 30 ]. Across methodologies, the half-life of knowledge in psychology has been estimated at 7–9 years [ 31 – 33 ]. Accordingly, we selected a prospective search window allowing 0–7 years for dissertations to be published. Because the doctoral dissertations were sampled from the year 2007, follow-up searches were restricted to articles published between 2007 and 2014. We elected to exclude candidate publications from years prior to 2007 for several reasons. First, most U.S. psychology Ph.D. programs follow a more traditional dissertation model (and this would have been even more ubiquitous in 2007), where the dissertation would have to be completed before it could be published in a peer-reviewed journal. Second, even for the minority of programs that might follow less conventional models such as dissertation-by-publication [ 34 ], the lag-time to publication would likely still result in at least one PD appearing in print concurrently with or after the dissertation, and would therefore be captured by our search strategy. Finally, any potential benefits of searching retrospectively were outweighed by the potential risks of introducing unreliability into the data, such as identifying false positives from student publications, master’s theses, pilot studies, or other analyses from the same sample. On the other end of our search window, candidate publications that appeared in print during or after 2015 were also not considered. Post hoc analyses (see Results ) suggested that this 0–7 year timeframe was adequate.

Publication search and coding procedures

Searches for PDs were conducted in two rounds, utilizing scholarly databases in a manner consistent with the evidence regarding their specificity, sensitivity, and quality. Specifically, searches were conducted first in PsycINFO, which has high specificity for psychological, social, and health sciences [ 35 – 36 ]; and second, in Google Scholar, casting a much broader net but still searching for peer-reviewed scholarly journal articles [ 35 , 37 – 40 ]. The objective of these searches was to locate the PDs or to determine that the dissertation had not been published in the indexed peer-reviewed journals. Although it is never possible to definitively ascertain a thing’s non-existence, we added additional steps and redundancies to ensure that our searches were as exhaustive as possible. First, when no PD was found in either scholarly databases, as a final step we conducted Google searches for the dissertation author and title, then reviewed the search results (e.g., CVs posted online, faculty web pages) for possible PDs. Second, all searching/coding procedures were performed at least twice by trained research assistants. If two coders disagreed on whether a PD was found, which article it was, or if either coder was uncertain, these dissertations were then coded by consensus among three or more members of the research team, including master’s-level researchers (SCE and CMA).

In all literature searches, the following queries were entered for each dissertation: (a) title of dissertation, without punctuation or logical operand terms; (b) author/ student’s name; and (c) chair/ advisor’s name. Search results were assessed for characteristics of authorship (student and chair names), content (title, abstract, acknowledgments, methods), and publication type (specifically targeting peer-reviewed journal articles) by which a PD could be positively identified. Determination of PD status was made and later validated based on global judgments of these criteria. Identified PDs were then coded for their bibliographic characteristics. Results were excluded if published in a non-English journal, outside of the 0–7 year (2007–2014) window, or in a non-refereed or non-journal outlet (e.g., book chapters). Because dissertations can contain multiple studies and be published as multiple articles, searches aimed to identify a single article that was most representative of the dissertation, based on the criteria outlined above and by consensus agreement among coders. All searches were conducted and coding was completed between January 2015 and May 2017.

Dissertation, publication, and year

Although the structure and content of doctoral dissertations varies across institutions, countries, and disciplines, the common unifying factor is that the dissertation represents an original research document produced by the student, approved by faculty, and for which a degree is conferred. Accordingly, in using PQDT as our population of U.S. Ph.D. psychology dissertations, we adhere to this broad but essential definition of a dissertation. This definition includes all different models of dissertations (e.g., ranging from traditional monographs to more recent models, such as briefer publication-ready dissertations and dissertation by publication [ 34 ]), but does not differentiate among them.

In this paper and in common scientific usage, “publication” refers to the dissemination of a written work to a broad audience, typically through a journal article. Accordingly, we do not consider indexing in digital databases for theses and dissertations as a publication such as in PQDT, even though it may be called “publishing” by the company. Rather, we define “dissertation publication” as the dissemination of at least part of one’s Ph.D. dissertation research in the form of an article published in a peer-reviewed journal. The peer-reviewed status of the journal was included among the variables that were coded twice with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Lastly, year of publication (2007, 2008, 2009 … 2014) and years since approval (0, 1, 2 … 7) were coded from when the print/final version of the article appeared, given that advance online access varies and is not available in all journals.

The PQDT subject terms were used as a proxy indicator of the subfield of psychology from which the dissertation was generated. As described above, twelve categories were derived ( Table 1 ). We considered five categories as professional/ applied subfields (clinical, counseling, educational/school, industrial-organizational, and behavioral), given that graduates in these fields are trained for careers that often include professional licensure or applied activities (e.g., consultation, program evaluation). In contrast, seven categories were considered research/ academic subfields (cognitive, developmental, experimental, neuroscience, quantitative, and social/personality), given that these subfields train primarily in a substantive or methodological research area. Note that Ph.D. programs in all of these subfields train their students to conduct research; when professional/ applied training components are present, they are there in addition to, not instead of, research training.

Article citations

The influence of PDs was estimated using article- and journal-level variables. At the article level, we used Web of Science to code the number of citations to the PD occurring each year since publication, tracking from 2007 up through year 2016. Importantly, Web of Science has been found to exhibit the lowest citation counts, but the citations which are included are drawn from a more rigorously controlled and higher quality collection of scholarly publications compared to others like Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus [ 35 , 37 – 38 , 40 – 41 ]. Citations were coded and analyzed primarily as the mean number of citations per year in order to account for time since publication. Total citations and citations each year were also calculated.

Journal-level metrics

The following journal impact metrics were recorded for the year in which the PD was published: (a) Impact Factor (IF) and (b) 5-Year IF [ 42 ]; (c) Article Influence Score (AIS) [ 43 ]; (d) Source Normalized Impact (SNIP) [ 44 ]; and (e) SCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR) [ 45 ]. Each of these indices shares different similarities and distinctions from the others and provides different information about how researchers cite articles in a given journal. While each has its limitations, these five indicators together offer a broad overall characterization of a journal’s influence, without over-relying on any single metric. As a frame of reference, the population-level descriptive statistics for each of these journal metrics (2007–2014) are as follows: IF ( M = 1.8, SD = 2.9), 5-year IF ( M = 2.2, SD = 3.0), SNIP ( M = 0.9, SD = 1.0), SJR ( M = 0.6, SD = 1.1), and AIS ( M = 0.8, SD = 1.4).

As described above, all of the dissertation, literature searching, and outcome data used in the present study were obtained from a variety of online sources available freely or by institutional subscription. Links to these sources can be found in the supplementary materials ( S1 File ).

Analytic plan

Overall descriptive analyses were conducted to examine the univariate and bivariate characteristics of the data, including the frequency and temporal distribution of PDs in psychology. Similar descriptive statistics were provided to characterize the nature of and scholarly influence of the PD via article citations and journal impact metrics. Group-based analyses were conducted using chi-square and ANOVAs to assess whether dissertation publication rates and scientific influence differed across subfields of psychology. The 95% CIs surrounding the total weighted estimate were used as an index of whether subfield estimates were significantly above or below average.

Time-to-publication analyses were conducted in three different ways. First, we used weighted Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier survival analyses to model dissertation publication as a time-to-event outcome, both for the overall sample and separately by subfields. Second, because the large majority of dissertations “survived” the publication outcome past our observation window (i.e., most cases were right-censored), we also conducted between-group comparisons regarding subfield publication times for only those whose dissertations were published. Finally, in order to ensure the adequacy of our 0–7 year search window, we fit a distribution to our observed data and projected this trend several years into the future.

Full-sample analyses were conducted using the complex samples option in SPSS Version 24, which yields weighted estimates that are less biased by sample proportions and more generalizable to the population. Distribution model-fitting and projections were estimated in R. For analyses related to dissertation publication outcomes, there were no missing data because all values could be coded based on obtained dissertations. Data availability for journal- and article-level variables are reported in those results tables.

Frequency of and time to publication

The overall weighted estimate showed that 25.6% (95% CI: 23.0, 28.4) of psychology dissertations were published in peer-reviewed journals within the period of 0–7 years following their completion. The unweighted estimate was similar (27.5% [24.6, 30.4]), but reflected sampling bias due to differences between subfields. Thus, weighted estimates are used in all subsequent results. Significant variations were found across subfields (Rao-Scott adjusted χ 2 ( df = 9.65) = 65.28, F (9.65, 8869.62) = 8.28, p < .001). As shown in Table 2 , greater proportions of PDs were found in neuroscience (59.4% [47.8, 70.1]), experimental (50.0% [37.7, 62.3]), and cognitive (41.0% [31.1, 51.8]), whereas much lower rates were found for industrial-organizational (10.1% [5.0, 19.5]) and general/miscellaneous (13.5% [6.5, 25.7]). All other subfields fell between 19.0 and 29.0%. Quantitative and social/personality fell within the 95% CIs for the weighted total, suggesting no difference; however, most other subfields fell above or below this average. Of note, three core professional subfields (clinical, counseling, and school/educational) were all between 19.0 and 20.8%—below average and not different from one another.

a Greater than weighted total

b Less than weighted total.