- My Preferences

- My Reading List

- The Federalist

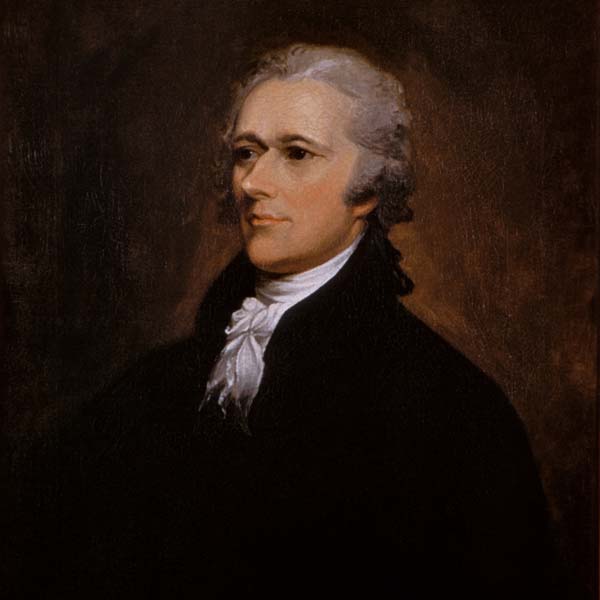

Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay

- Literature Notes

- Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton)

- About The Federalist

- Summary and Analysis

- Section I: General Introduction: Federalist No. 1 (Alexander Hamilton)

- Section I: General Introduction: Federalist No. 2 (John Jay)

- Section I: General Introduction: Federalist No. 3 (Jay)

- Section I: General Introduction: Federalist No. 4 (Jay)

- Section I: General Introduction: Federalist No. 5 (Jay)

- Section I: General Introduction: Federalist No. 6 (Hamilton)

- Section I: General Introduction: Federalist No. 7 (Hamilton)

- Section I: General Introduction: Federalist No. 8 (Hamilton)

- Section II: Advantages of Union: Federalist No. 9 (Hamilton)

- Section II: Advantages of Union: Federalist No. 10 (James Madison)

- Section II: Advantages of Union: Federalist No. 11 (Hamilton)

- Section II: Advantages of Union: Federalist No. 12 (Hamilton)

- Section II: Advantages of Union: Federalist No. 13 (Hamilton)

- Section II: Advantages of Union: Federalist No. 14 (Madison)

- Section III: Disadvantages of Existing Government: Federalist No. 15 (Hamilton)

- Section III: Disadvantages of Existing Government: Federalists No. 16-20 (Madison and Hamilton)

- Section III: Disadvantages of Existing Government: Federalist No. 21 (Hamilton)

- Section III: Disadvantages of Existing Government: Federalist No. 22 (Hamilton)

- Section IV: Common Defense: Federalists No. 23-29 (Hamilton)

- Section V: Powers of Taxation: Federalists No. 30-36 (Hamilton)

- Section VI: Difficulties in Framing Constitution: Federalists No. 37-40 (Madison)

- Section VII: General Powers: Federalists No. 41-46 (Madison)

- Section VIII: Structure of New Government: Federalists No. 47–51 (Madison or Hamilton)

- Section IX: House of Representatives: Federalists No. 52–61 (Madison or Hamilton)

- Section X: United States Senate: Federalists No. 62–66 (Madison or Hamilton)

- Section XI: Need for a Strong Executive: Federalist No. 67 (Hamilton)

- Section XI: Need for a Strong Executive: Federalist No. 68 (Hamilton)

- Section XI: Need for a Strong Executive: Federalists No. 69-74 (Hamilton)

- Section XI: Need for a Strong Executive: Federalists No. 75-77 (Hamilton)

- Section XII: Judiciary: Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton)

- Section XII: Judiciary: Federalist No. 79 (Hamilton)

- Section XII: Judiciary: Federalist No. 80 (Hamilton)

- Section XII: Judiciary: Federalist No. 81 (Hamilton)

- Section XII: Judiciary: Federalist No. 82 (Hamilton)

- Section XII: Judiciary: Federalist No. 83 (Hamilton)

- Section XIII: Conclusions: Federalist No. 84 (Hamilton)

- Section XIII: Conclusions: Federalist No. 85 (Hamilton)

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- Alexander Hamilton Biography

- James Madison Biography

- John Jay Biography

- Essay Questions

- Cite this Literature Note

Summary and Analysis Section XII: Judiciary: Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton)

This section of six chapters deals with the proposed structure of federal courts, their powers and jurisdiction, the method of appointing judges, and related matters.

A first important consideration was the manner of appointing federal judges, and the length of their tenure in office. They should be appointed in the same way as other federal officers, which had been discussed before. As to tenure, the Constitution proposed that they should hold office " during good behaviour ," a provision to be found in the constitutions of almost all the states. As experience had proved, there was no better way of securing a steady, upright, and impartial administration of the law. To perform its functions well, the judiciary had to remain "truly distinct" from both the legislative and executive branches of the government, and act as a check on both.

There had been some question — Hamilton called it a "perplexity," as well he might — about the rights of the courts to declare a legislative act null and void if, in the court's opinion, it violated the Constitution. It was argued that this implied a "superiority of the judiciary to the legislative power." Not at all, Hamilton argued. The courts had to regard the Constitution as fundamental law, and it was, therefore, the responsibility of the courts "to ascertain its meaning as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body." The same should apply to actions taken by the executive.

In this essay Hamilton discussed the question of whether the Supreme Court should have the authority to declare acts of Congress null and void because, in the Court's opinion, they violated the Constitution. Hamilton answered in the affirmative; such a power would tend to curb the "turbulence and follies of democracy." But others have disagreed with Hamilton about this. Among those who have wished to curtail the Supreme Court's power to invalidate acts of Congress have been Presidents Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. The issue is still a live one, as is evident from the heated debates of recent years.

Previous Federalists No. 75-77 (Hamilton)

Next Federalist No. 79 (Hamilton)

has been added to your

Reading List!

Removing #book# from your Reading List will also remove any bookmarked pages associated with this title.

Are you sure you want to remove #bookConfirmation# and any corresponding bookmarks?

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

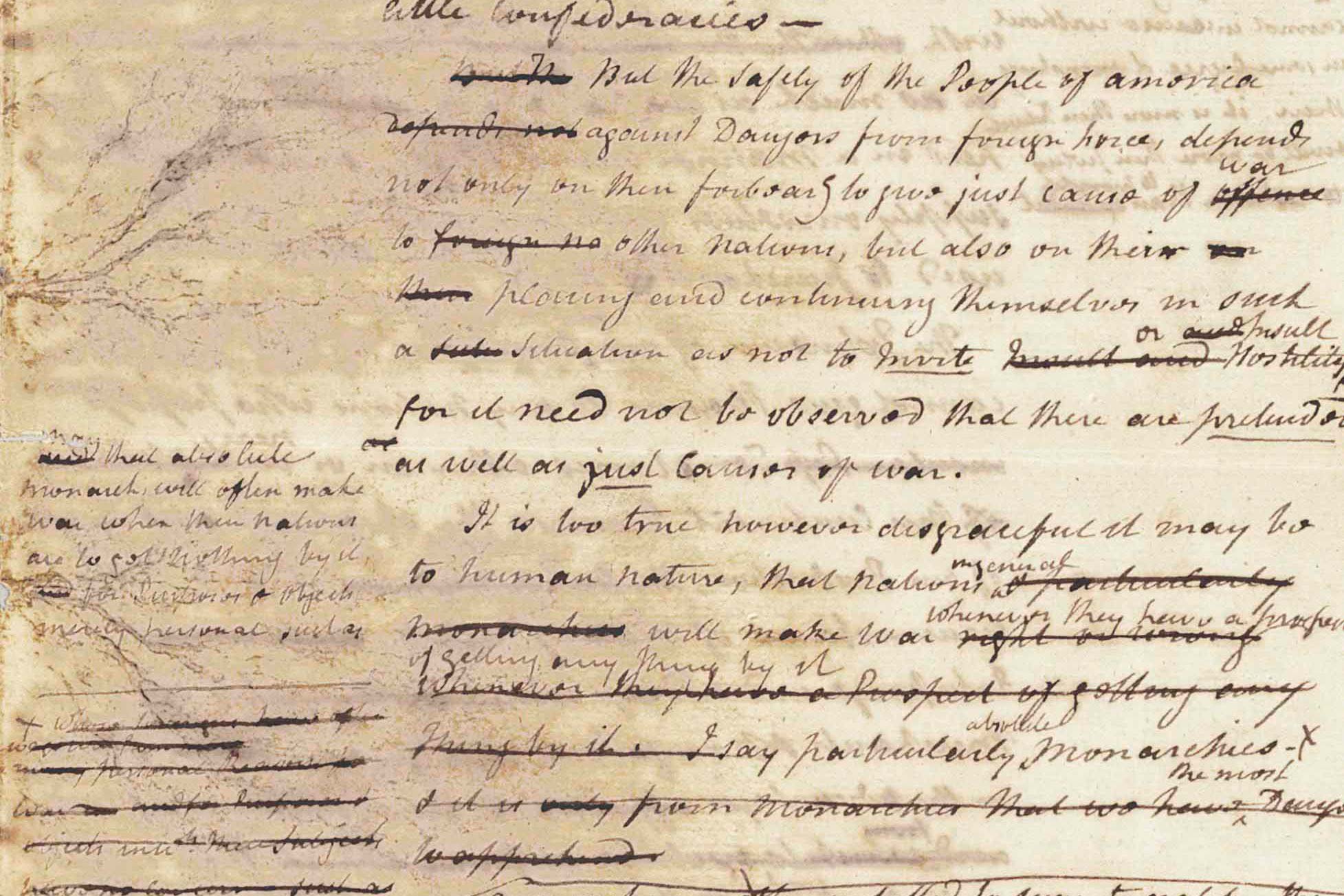

The first amendment, historic document, federalist 78 (1788).

Alexander Hamilton | 1788

On May 28, 1788, Alexander Hamilton published Federalist 78—titled “The Judicial Department.” In this famous Federalist Paper essay, Hamilton offered, perhaps, the most powerful defense of judicial review in the American constitutional canon. On the one hand, Hamilton defined the judicial branch as the “least dangerous” branch of the new national government. On the other hand, he also emphasized the importance of an independent judiciary and the power of judicial review. With judicial independence, the Constitution put barriers in place—like life tenure and salary protections—to ensure that the federal courts were independent from the control of the elected branches. And with judicial review, federal judges had the power to review the constitutionality of the laws and actions of the government—ensuring that they met the requirements of the new Constitution. Other than Marbury v. Madison (1803), Hamilton’s essay remains the most famous defense of judicial review in American history, and it even served as the basis for many of Chief Justice John Marshall’s arguments in Marbury itself.

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

According to the plan of the convention, all judges who may be appointed by the United States are to hold their offices DURING GOOD BEHAVIOR; which is conformable to the most approved of the State constitutions and among the rest, to that of this State. . . . The standard of good behavior for the continuance in office of the judicial magistracy, is certainly one of the most valuable of the modern improvements in the practice of government. In a monarchy it is an excellent barrier to the despotism of the prince; in a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body. And it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government, to secure a steady, upright, and impartial administration of the laws.

Whoever attentively considers the different departments of power must perceive, that, in a government in which they are separated from each other, the judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them. The Executive not only dispenses the honors, but holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse, but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments. . . .

There is no position which depends on clearer principles, than that every act of a delegated authority, contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid. To deny this, would be to affirm, that the deputy is greater than his principal; that the servant is above his master; that the representatives of the people are superior to the people themselves; that men acting by virtue of powers, may do not only what their powers do not authorize, but what they forbid.

If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the constitutional judges of their own powers, and that the construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the other departments, it may be answered, that this cannot be the natural presumption, where it is not to be collected from any particular provisions in the Constitution. It is not otherwise to be supposed, that the Constitution could intend to enable the representatives of the people to substitute their WILL to that of their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose, that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Nor does this conclusion by any means suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both; and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the former. They ought to regulate their decisions by the fundamental laws, rather than by those which are not fundamental. . . .

If, then, the courts of justice are to be considered as the bulwarks of a limited Constitution against legislative encroachments, this consideration will afford a strong argument for the permanent tenure of judicial offices, since nothing will contribute so much as this to that independent spirit in the judges which must be essential to the faithful performance of so arduous a duty.

This independence of the judges is equally requisite to guard the Constitution and the rights of individuals from the effects of those ill humors, which the arts of designing men, or the influence of particular conjunctures, sometimes disseminate among the people themselves, and which, though they speedily give place to better information, and more deliberate reflection, have a tendency, in the meantime, to occasion dangerous innovations in the government, and serious oppressions of the minor party in the community. . . . Until the people have, by some solemn and authoritative act, annulled or changed the established form [of government], it is binding upon themselves collectively, as well as individually; and no presumption, or even knowledge, of their sentiments, can warrant their representatives in a departure from it, prior to such an act. But it is easy to see, that it would require an uncommon portion of fortitude in the judges to do their duty as faithful guardians of the Constitution, where legislative invasions of it had been instigated by the major voice of the community.

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

The Federalist Papers

By alexander hamilton , james madison , john jay, the federalist papers summary and analysis of essay 78.

Hamilton begins by telling the readers that this paper will discuss the importance of an independent judicial branch and the meaning of judicial review. The Constitution proposes the federal judges hold their office for life, subject to good behavior. Hamilton laughs at anyone who questions that life tenure is the most valuable advance in the theory of representative government. Permanency in office frees judges from political pressures and prevents invasions on judicial power by the president and Congress.

The judicial branch of government is by far the weakest branch. The judicial branch posses only the power to judge, not to act, and even its judgments or decisions depend upon the executive branch to carry them out. Political rights are least threatened by the judicial branch. On occasion, the courts may unfairly treat an individual, but they, in general, can never threaten liberty.

The Constitution imposes certain restrictions on the Congress designed to protect individual liberties, but unless the courts are independent and have the power to declare laws in violation of the Constitution null and void, those protections amount to nothing. The power of the Supreme Court to declare laws unconstitutional leads some people to assume that the judicial branch will be superior to the legislative branch. Hamilton examines this argument, starting with the fact that only the Constitution is fundamental law. To argue that the Constitution is not superior to the laws suggest that the representatives of the people are superior to the people and that the Constitution is inferior to the government it gave birth to. The courts are the arbiters between the legislative branch and the people; the courts are to interpret the laws and prevent the legislative branch from exceeding the powers granted to it. The courts must not only place the Constitution higher than the laws passed by Congress, they must also place the intentions of the people ahead of the intentions of their representatives. This is not a matter of which branch is superior: it is simply to acknowledge that the people are superior to both. It is futile to argue that the court's decisions, in some instances, might interfere with the will of the legislature. People argue that it is the function of Congress, not the courts, to pass laws and formulate policy. This is true, but to interpret the laws and judge their constitutionality are the two special functions of the court. The fact that the courts are charged with determining what the law means does not suggest that they will be justified in substituting their will for that of the Congress.

The independence of the courts is also necessary to protect the rights of individuals against the destructive actions of factions. Certain designing men may influence the legislature to formulate policies and pass laws that violate the Constitution or individual rights. The fact that the people have the right to change or abolish their government if it becomes inconsistent with their happiness is not sufficient protection; in the first place, stability requires that such changes be orderly and constitutional. A government at the mercy of groups continually plotting its downfall would be in a deplorable situation. The only way citizens can feel their rights are secure is to know that the judicial branch protects them against the people, both in and outside government, who work against their interests.

Hamilton cites one other important reason for judges to have life tenure. In a free government there are bound to be many laws, some of them complex and contradictory. It takes many years to fully understand the meaning of these laws and a short term of office would discourage able and honest men from seeking an appointment to the courts; they would be reluctant to give up lucrative law practices to accept a temporary judicial appointment. Life tenure, modified by good behavior, is a superb device for assuring judicial independence and protection of individual rights.

With a view toward creating a judiciary that would constitute a balance against Congress, the Convention provided for the independence of the courts from Congress. Hamilton opposes vesting supreme judicial power in a branch of the legislative body because this would verge upon a violation of that "excellent rule," the separation of powers. Besides, due to the propensity of legislative bodies to party division, there is "reason to fear that the pestilent breath of faction may poison the fountains of justice." Hamilton, therefore, praises the Constitution for establishing courts that are separated from Congress. He is pleased to note that to this organizational independence there is added a financial one.

Another factor contributing to the independence of the judiciary is the judges' right to hold office during good behavior. It is in connection with his advocacy of that "excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of that reprehensive body," that "citadel of the public justice," that Hamilton pronounces judicial review as being part of the Constitution. Judicial review is another barrier against too much democracy. Exercised by state courts before the Federal Convention met, and taken for granted by the majority of the members of the Convention, as well as by the ratifying conventions in the states, judicial review is expounded by Hamilton as a doctrine reaching a climax and a conclusion in this Federalist paper.

Starting out from the premise that "a constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judged, as a fundamental law," Hamilton considers judicial review as a means of preserving that constitution and, thereby, free government. To be more concrete, when Hamilton considers the judiciary both as a barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body and as the citadel of public justice, i.e., the citadel for the protection of the individual's life, liberty, and property, he states that judicial review means a curb on the legislature's encroachments upon individual rights. Parallel to every denial of legislative power in essay seventy-eight goes an assertion of vested rights. Note that the Supreme Court did not ultimately grant itself the explicit power of judicial review until the case Marbury v. Madison in 1803.

Although he considers a power-concentration in the legislature as despotism, Hamilton does not perceive a strong judiciary as a threat to free government. He admits that individual oppression may now and then proceed from the courts, but he is emphatic in adding that the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter. When the judge unites integrity with knowledge, power is in good hands. As the "bulwarks of a limited Constitution against legislative encroachments," they will use that power for the protection of the individual's rights rather than for infringements upon those rights.

Through judicial review vested rights are protected not only from the legislature, they are also protected from the executive. An executive act that is sanctioned by the courts and - since it is the duty of the judges to declare void legislative acts contrary to the Constitution - that is thus in conformity with the will of the people as laid down in the Constitution, cannot be an act of oppression.

The Federalist Papers Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for The Federalist Papers is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

how are conflictstoo often decided in unstable government? Whose rights are denied when this happens?

In a typical non-democratic government with political instability, the conflicts are often decided by the person highest in power, who abuse powers or who want to seize power. Rival parties fight each other to the detriment of the country.

How Madison viewed human nature?

Madison saw depravity in human nature, but he saw virtue as well. His view of human nature may have owed more to John Locke than to John Calvin. In any case, as Saul K. Padover asserted more than a half-century ago, Madison often appeared to steer...

How arguable and provable is the author of cato 4 claim

What specific claim are you referring to?

Study Guide for The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers study guide contains a biography of Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About The Federalist Papers

- The Federalist Papers Summary

- The Federalist Papers Video

- Character List

Essays for The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison.

- A Close Reading of James Madison's The Federalist No. 51 and its Relevancy Within the Sphere of Modern Political Thought

- Lock, Hobbes, and the Federalist Papers

- Comparison of Federalist Paper 78 and Brutus XI

- The Paradox of the Republic: A Close Reading of Federalist 10

- Manipulation of Individual Citizen Motivations in the Federalist Papers

Lesson Plan for The Federalist Papers

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to The Federalist Papers

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- The Federalist Papers Bibliography

E-Text of The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers e-text contains the full text of The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison.

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 1-5

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 6-10

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 11-15

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 16-20

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 21-25

Wikipedia Entries for The Federalist Papers

- Introduction

- Structure and content

- Judicial use

- Complete list

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

The federalist no. 78, [28 may 1788], the federalist no. 78 1.

[New York, May 28, 1788]

To the People of the State of New-York.

WE proceed now to an examination of the judiciary department of the proposed government.

In unfolding the defects of the existing confederation, the utility and necessity of a federal judicature have been clearly pointed out. 2 It is the less necessary to recapitulate the considerations there urged; as the propriety of the institution in the abstract is not disputed: The only questions which have been raised being relative to the manner of constituting it, and to its extent. To these points therefore our observations shall be confined.

The manner of constituting it seems to embrace these several objects—1st. The mode of appointing the judges—2d. The tenure by which they are to hold their places—3d. The partition of the judiciary authority between different courts, and their relations to each other.

First. As to the mode of appointing the judges: This is the same with that of appointing the officers of the union in general, and has been so fully discussed in the two last numbers, that nothing can be said here which would not be useless repetition.

Second. As to the tenure by which the judges are to hold their places: This chiefly concerns their duration in office; the provisions for their support; and 3 the precautions for their responsibility.

According to the plan of the convention, all the judges who may be appointed by the United States are to hold their offices during good behaviour , which is conformable to the most approved of the state constitutions; and 4 among the rest, to that of this state. Its propriety having been drawn into question by the adversaries of that plan, is no light symptom of the rage for objection which disorders their imaginations and judgments. The standard of good behaviour for the continuance in office of the judicial magistracy is certainly one of the most valuable of the modern improvements in the practice of government. In a monarchy it is an excellent barrier to the despotism of the prince: In a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body. And it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government, to secure a steady, upright and impartial administration of the laws.

Whoever attentively considers the different departments of power must perceive, that in a government in which they are separated from each other, the judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them. The executive not only dispenses the honors, but holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse, but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary on the contrary has no influence over either the sword or the purse, no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society, and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither force nor will , but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even 5 for the efficacy of its judgments. 6

This simple view of the matter suggests several important consequences. It proves incontestibly that the judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power; * that it can never attack with success either of the other two; and that all possible care is requisite to enable it to defend itself against their attacks. It equally proves, that though individual oppression may now and then proceed from the courts of justice, the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter; I mean, so long as the judiciary remains truly distinct from both the legislative and executive. For I agree that “there is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers.” † And 9 it proves, in the last place, that as liberty can have nothing to fear from the judiciary alone, but would have every thing to fear from its union with either of the other departments; that as all the effects of such an union must ensue from a dependence of the former on the latter, notwithstanding a nominal and apparent separation; that as from the natural feebleness of the judiciary, it is in continual jeopardy of being overpowered, awed or influenced by its coordinate branches; and 11 that as nothing can contribute so much to its firmness and independence, as permanency in office, this quality may therefore be justly regarded as an indispensable ingredient in its constitution; and in a great measure as the citadel of the public justice and the public security.

The complete independence of the courts of justice is peculiarly essential in a limited constitution. By a limited constitution I understand one which contains certain specified exceptions to the legislative authority; such for instance as that it shall pass no bills of attainder, no ex post facto laws, and the like. Limitations of this kind can be preserved in practice no other way than through the medium of the courts of justice; whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the constitution void. Without this, all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing.

Some perplexity respecting the right of the courts to pronounce legislative acts void, because contrary to the constitution, has arisen from an imagination that the doctrine would imply a superiority of the judiciary to the legislative power. It is urged that the authority which can declare the acts of another void, must necessarily be superior to the one whose acts may be declared void. As this doctrine is of great importance in all the American constitutions, a brief discussion of the grounds on which it rests cannot be unacceptable.

There is no position which depends on clearer principles, than that every act of a delegated authority, contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act therefore contrary to the constitution can be valid. To deny this would be to affirm that the deputy is greater than his principal; that the servant is above his master; that the representatives of the people are superior to the people themselves; that men acting by virtue of powers may do not only what their powers do not authorise, but what they forbid.

If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the constitutional judges of their own powers, and that the construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the other departments, it may be answered, that this cannot be the natural presumption, where it is not to be collected 12 from any particular provision in the constitution. It is not otherwise to be supposed that the constitution could intend to enable the representatives of the people to substitute their will to that of their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is in fact, and must be, regarded by the judges as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs 13 to them to ascertain its meaning as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcileable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought of course to be preferred; or 14 in other words, the constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Nor does this 15 conclusion by any means suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both; and that where the will of the legislature declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people declared in the constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter, rather than the former. They ought to regulate their decisions by the fundamental laws, rather than by those which are not fundamental.

This exercise of judicial discretion in determining between two contradictory laws, is exemplified in a familiar instance. It not uncommonly happens, that there are two statutes existing at one time, clashing in whole or in part with each other, and neither of them containing any repealing clause or expression. In such a case, it is the province of the courts to liquidate and fix their meaning and operation: So far as they can by any fair construction be reconciled to each other; reason and law conspire to dictate that this should be done: Where this is impracticable, it becomes a matter of necessity to give effect to one, in exclusion of the other. The rule which has obtained in the courts for determining their relative validity is that the last in order of time shall be preferred to the first. But this is mere rule of construction, not derived from any positive law, but from the nature and reason of the thing. It is a rule not enjoined upon the courts by legislative provision, but adopted by themselves, as consonant to truth and propriety, for the direction of their conduct as interpreters of the law. They thought it reasonable, that between the interfering acts of an equal authority, that which was the last indication of its will, should have the preference.

But in regard to the interfering acts of a superior and subordinate authority, of an original and derivative power, the nature and reason of the thing indicate the converse of that rule as proper to be followed. They teach us that the prior act of a superior ought to be prefered to the subsequent act of an inferior and subordinate authority; and that, accordingly, whenever a particular statute contravenes the constitution, it will be the duty of the judicial tribunals to adhere to the latter, and disregard the former.

It can be of no weight to say, that the courts on the pretence of a repugnancy, may substitute their own pleasure to the constitutional intentions of the legislature. This might as well happen in the case of two contradictory statutes; or it might as well happen in every adjudication upon any single statute. The courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise will instead of judgment , the consequence would equally be the substitution of their pleasure to that of the legislative body. The observation, if it proved any thing, would prove that there ought to be no judges distinct from that body.

If then the courts of justice are to be considered as the bulwarks of a limited constitution against legislative encroachments, this consideration will afford a strong argument for the permanent tenure of judicial offices, since nothing will contribute so much as this to that independent spirit in the judges, which must be essential to the faithful performance of so arduous a duty.

This independence of the judges is equally requisite to guard the constitution and the rights of individuals from the effects of those ill humours which the arts of designing men, or the influence of particular conjunctures, sometimes disseminate among the people themselves, and which, though they speedily give place to better information and more deliberate reflection, have a tendency in the mean time to occasion dangerous innovations in the government, and serious oppressions of the minor party in the community. Though I trust the friends of the proposed constitution will never concur with its enemies * in questioning that fundamental principle of republican government, which admits the right of the people to alter or abolish the established constitution whenever they find it inconsistent with their happiness; yet it is not to be inferred from this principle, that the representatives of the people, whenever a momentary inclination happens to lay hold of a majority of their constituents incompatible with the provisions in the existing constitution, would on that account be justifiable in a violation of those provisions; or that the courts would be under a greater obligation to connive at infractions in this shape, than when they had proceeded wholly from the cabals of the representative body. Until the people have by some solemn and authoritative act annulled or changed the established form, it is binding upon themselves collectively, as well as individually; and no presumption, or even knowledge of their sentiments, can warrant their representatives in a departure from it, prior to such an act. But it is easy to see that it would require an uncommon portion of fortitude in the judges to do their duty as faithful guardians of the constitution, where legislative invasions of it had been instigated by the major voice of the community.

But it is not with a view to infractions of the constitution only that the independence of the judges may be an essential safeguard against the effects of occasional ill humours in the society. These sometimes extend no farther than to the injury of the private rights of particular classes of citizens, by unjust and partial laws. Here also the firmness of the judicial magistracy is of vast importance in mitigating the severity, and confining the operation of such laws. It not only serves to moderate the immediate mischiefs of those which may have been passed, but it operates as a check upon the legislative body in passing them; who, perceiving that obstacles to the success of an iniquitous intention are to be expected from the scruples of the courts, are in a manner compelled by the very motives of the injustice they meditate, to qualify their attempts. This is a circumstance calculated to have more influence upon the character of our governments, than but few may be aware of. 17 The benefits of the integrity and moderation of the judiciary have already been felt in more states than one; and though they may have displeased those whose sinister expectations they may have disappointed, they must have commanded the esteem and applause of all the virtuous and disinterested. Considerate men of every description ought to prize whatever will tend to beget or fortify that temper in the courts; as no man can be sure that he may not be to-morrow the victim of a spirit of injustice, by which he may be a gainer to-day. And every man must now feel that the inevitable tendency of such a spirit is to sap the foundations of public and private confidence, and to introduce in its stead, universal distrust and distress.

That inflexible and uniform adherence to the rights of the constitution and of individuals, which we perceive to be indispensable in the courts of justice, can certainly not be expected from judges who hold their offices by a temporary commission. Periodical appointments, however regulated, or by whomsoever made, would in some way or other be fatal to their necessary independence. If the power of making them was committed either to the executive or legislature, there would be danger of an improper complaisance to the branch which possessed it; if to both, there would be an unwillingness to hazard the displeasure of either; if to the people, or to persons chosen by them for the special purpose, there would be too great a disposition to consult popularity, to justify a reliance that nothing would be consulted but the constitution and the laws.

There is yet a further and a weighty reason for the permanency of the 18 judicial offices; which is deducible from the nature of the qualifications they require. It has been frequently remarked with great propriety, that a voluminous code of laws is one of the inconveniences necessarily connected with the advantages of a free government. To avoid an arbitrary discretion in the courts, it is indispensable that they should be bound down by strict rules and precedents, which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them; and it will readily be conceived from the variety of controversies which grow out of the folly and wickedness of mankind, that the records of those precedents must unavoidably swell to a very considerable bulk, and must demand long and laborious study to acquire a competent knowledge of them. Hence it is that there can be but few men in the society, who will have sufficient skill in the laws to qualify them for the stations of judges. And making the proper deductions for the ordinary depravity of human nature, the number must be still smaller of those who unite the requisite integrity with the requisite knowledge. These considerations apprise us, that the government can have no great option between fit characters; and that a temporary duration in office, which would naturally discourage such characters from quitting a lucrative line of practice to accept a seat on the bench, would have a tendency to throw the administration of justice into hands less able, and less well qualified to conduct it with utility and dignity. In the present circumstances of this country, and in those in which it is likely to be for a long time to come, the disadvantages on this score would be greater than they may at first sight appear; but it must be confessed that they are far inferior to those which present themselves under the other aspects of the subject.

Upon the whole there can be no room to doubt that the convention acted wisely in copying from the models of those constitutions which have established good behaviour as the tenure of their 19 judicial offices in point of duration; and that so far from being blameable on this account, their plan would have been inexcuseably defective if it had wanted this important feature of good government. The experience of Great Britain affords an illustrious comment on the excellence of the institution.

J. and A. McLean, The Federalist , II, 290–99, published May 28, 1788, numbered 78. This essay appeared on June 14 in The [New York] Independent Journal: or, the General Advertiser and is numbered 77. In New-York Packet it was begun on June 17 and concluded on June 20 and is numbered 78.

1 . For background to this document, see “The Federalist. Introductory Note,” October 27, 1787–May 28, 1788 .

2 . See essay 22 .

3 . “and” omitted in Hopkins description begins The Federalist On The New Constitution. By Publius. Written in 1788. To Which is Added, Pacificus, on The Proclamation of Neutrality. Written in 1793. Likewise, The Federal Constitution, With All the Amendments. Revised and Corrected. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by George F. Hopkins, at Washington’s Head, 1802). description ends .

4 . “and” omitted in Hopkins.

5 . “even” omitted in Hopkins.

6 . “efficacious exercise even of this faculty” substituted for “efficacy of its judgments” in Hopkins.

7 . “The celebrated” omitted in Hopkins.

8 . H’s reference is to Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws , Book XI, Ch. 6.

9 . “And” omitted in Hopkins.

10 . The reference is to Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws , Book XI, Ch. 6.

11 . “and” omitted in Hopkins.

12 . “recollected” substituted for “collected” in Hopkins.

13 . “must therefore belong” substituted for “therefore belongs” in Hopkins.

14 . “or” omitted in Hopkins.

15 . “the” substituted for “this” in Hopkins.

16 . H is referring to “The Address and Reasons of Dissent of the Minority of the Convention of the State of Pennsylvania to their Constituents.” Signed by twenty-one members of the Pennsylvania Ratifying Convention, the address appeared in The Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser on December 18, 1787, six days after Pennsylvania had ratified the Constitution.

“Martin’s speech” presumably refers to an address by Luther Martin, a member of the Constitutional Convention and bitter foe of the proposed Constitution, before the Maryland House of Delegates on January 27, 1788.

17 . “imagine” substituted for “be aware of” in Hopkins.

18 . “the” omitted in Hopkins.

19 . “their” omitted in Hopkins.

Authorial notes

[The following note(s) appeared in the margins or otherwise outside the text flow in the original source, and have been moved here for purposes of the digital edition.]

* The celebrated 7 Montesquieu speaking of them says, “of the three powers above mentioned, the Judiciary is next to nothing.” Spirit of Laws, vol. I, page 186. 8

† Idem. page 181. 10

* Vide Protest of the minority of the convention of Pennsylvania, Martin’s speech, &c. 16

Index Entries

You are looking at.

The American Founding

Federalist No. 78

May 28, 1788

INTRODUCTION

This is the first of five essays by Publius (in this case, Hamilton) on the judiciary. The heart of this essay covers the case for the duration of judges in office. Publius points out that their lifetime appointments are guaranteed only “during good behavior.” He calls the insistence on this standard “one of the most valuable of the modern improvements in the practice of government.” To insure that judges maintain this standard, resisting encroachments from the legislature (to which presumably they would be vulnerable by means of bribes or threats), the Constitution gives them “permanent tenure.”

Publius then makes the famous claim that the judiciary “will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution. . . . It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL but merely judgment.” As “the weakest of the three departments of power,” it needs fortification.

It is the “duty” of the courts “to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the constitution void.” Without an independent judiciary to fulfill this task, any rights reserved to the people by the Constitution “would amount to nothing,” since the legislature cannot be relied upon to police itself. This arrangement does not render the judiciary the supreme branch of government. Rather, it ensures that the Constitution remain the supreme law of the land.

Publius’s argument here recognizes the possibility that in a representative government there are competing contenders to represent the people. Those elected to Congress rightly claim to act on the people’s authority; yet the Constitution, having been ratified by the people, itself represents the people’s will, and will have priority over more recently elected representatives. Publius contrasts this rule with that which applies in representative governments without a written constitution. In those systems, if a law is passed which contradicts an earlier law, judges are obliged to rule that the more recently passed law invalidates the first. But in a Constitutional system, any law contradicting the Constitution will be ruled invalid.

Implicitly, Publius recognizes the fallibility of the people and their representatives. He asserts, in effect, that the proposed Constitution insures that the careful, considered judgment of the Framers — made after considerable debate and compromise — will have priority over “dangerous innovations in the government” pushed by “designing men.”

He also predicts that a judicial branch with permanent tenure will discourage the appointment of incompetent or dishonest judges, while also preventing unconstitutional legislation from even being proposed.

We proceed now to an examination of the judiciary department of the proposed government.

In unfolding the defects of the existing Confederation, the utility and necessity of a federal judicature have been clearly pointed out. It is the less necessary to recapitulate the considerations there urged as the propriety of the institution in the abstract is not disputed; the only questions which have been raised being relative to the manner of constituting it, and to its extent. To these points, therefore, our observations shall be confined.

The manner of constituting it seems to embrace these several objects: 1st. The mode of appointing the judges. 2nd. The tenure by which they are to hold their places. 3d. The partition of the judiciary authority between different courts and their relations to each other.

First. As to the mode of appointing the judges: this is the same with that of appointing the officers of the Union in general and has been so fully discussed in the two last numbers that nothing can be said here which would not be useless repetition.

Second. As to the tenure by which the judges are to hold their places: this chiefly concerns their duration in office; the provisions for their support, and the precautions for their responsibility.

According to the plan of the convention, all the judges who may be appointed by the United States are to hold their offices during good behavior; which is conformable to the most approved of the State constitutions, and among the rest, to that of this State. Its propriety having been drawn into question by the adversaries of that plan is no light symptom of the rage for objection which disorders their imaginations and judgments. The standard of good behavior for the continuance in office of the judicial magistracy is certainly one of the most valuable of the modern improvements in the practice of government. In a monarchy it is an excellent barrier to the despotism of the prince; in a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body. And it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government to secure a steady, upright and impartial administration of the laws.

Whoever attentively considers the different departments of power must perceive that, in a government in which they are separated from each other, the judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them. The executive not only dispenses the honors but holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society, and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.

This simple view of the matter suggests several important consequences. It proves incontestably that the judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power; that it can never attack with success either of the other two; and that all possible care is requisite to enable it to defend itself against their attacks. It equally proves that though individual oppression may now and then proceed from the courts of justice, the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter: I mean, so long as the judiciary remains truly distinct from both the legislative and executive. For I agree that “there is no liberty if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers.” [1] And it proves, in the last place, that as liberty can have nothing to fear from the judiciary alone, but would have everything to fear from its union with either of the other departments; that as all the effects of such a union must ensue from a dependence of the former on the latter, notwithstanding a nominal and apparent separation; that as, from the natural feebleness of the judiciary, it is in continual jeopardy of being overpowered, awed or influenced by its coordinate branches; and that as nothing can contribute so much to its firmness and independence as permanency in office, this quality may therefore be justly regarded as an indispensable ingredient in its constitution, and in a great measure as the citadel of the public justice and the public security.

The complete independence of the courts of justice is peculiarly essential in a limited Constitution. By a limited Constitution, I understand one which contains certain specified exceptions to the legislative authority; such, for instance, as that it shall pass no bills of attainder, no ex post facto laws, [2] and the like. Limitations of this kind can be preserved in practice no other way than through the medium of the courts of justice, whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the Constitution void. Without this, all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing.

Some perplexity respecting the right of the courts to pronounce legislative acts void, because contrary to the Constitution, has arisen from an imagination that the doctrine would imply a superiority of the judiciary to the legislative power. It is urged that the authority which can declare the acts of another void must necessarily be superior to the one whose acts may be declared void. As this doctrine is of great importance in all the American constitutions, a brief discussion of the grounds on which it rests cannot be unacceptable.

There is no position which depends on clearer principles than that every act of a delegated authority, contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act therefore contrary to the constitution can be valid. To deny this would be to affirm that the deputy is greater than his principal; that the servant is above his master; that the representatives of the people are superior to the people themselves; that men acting by virtue of powers may do not only what their powers do not authorize, but what they forbid.

If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the constitutional judges of their own powers and that the construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the other departments it may be answered that this cannot be the natural presumption where it is not to be collected from any particular provisions in the Constitution. It is not otherwise to be supposed that the Constitution could intend to enable the representatives of the people to substitute their will to that of their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is in fact, and must be regarded by the judges as, a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course; to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Nor does this conclusion by any means suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both, and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the former. They ought to regulate their decisions by the fundamental laws rather than by those which are not fundamental.

This exercise of judicial discretion in determining between two contradictory laws is exemplified in a familiar instance. It not uncommonly happens that there are two statutes existing at one time, clashing in whole or in part with each other, and neither of them containing any repealing clause or expression. In such a case, it is the province of the courts to liquidate and fix their meaning and operation. So far as they can, by any fair construction, be reconciled to each other, reason and law conspire to dictate that this should be done; where this is impracticable, it becomes a matter of necessity to give effect to one in exclusion of the other. The rule which has obtained in the courts for determining their relative validity is that the last in order of time shall be preferred to the first. But this is mere rule of construction, not derived from any positive law but from the nature and reason of the thing. It is a rule not enjoined upon the courts by legislative provision but adopted by themselves, as consonant to truth and propriety, for the direction of their conduct as interpreters of the law. They thought it reasonable that between the interfering acts of an equal authority that which was the last indication of its will, should have the preference.

But in regard to the interfering acts of a superior and subordinate authority of an original and derivative power, the nature and reason of the thing indicate the converse of that rule as proper to be followed. They teach us that the prior act of a superior ought to be preferred to the subsequent act of an inferior and subordinate authority; and that, accordingly, whenever a particular statute contravenes the Constitution, it will be the duty of the judicial tribunals to adhere to the latter and disregard the former.

It can be of no weight to say that the courts, on the pretense of a repugnancy, may substitute their own pleasure to the constitutional intentions of the legislature. This might as well happen in the case of two contradictory statutes; or it might as well happen in every adjudication upon any single statute. The courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise WILL instead of JUDGMENT, the consequence would equally be the substitution of their pleasure to that of the legislative body. The observation, if it proved any thing, would prove that there ought to be no judges distinct from that body.

If, then, the courts of justice are to be considered as the bulwarks of a limited Constitution against legislative encroachments, this consideration will afford a strong argument for the permanent tenure of judicial offices, since nothing will contribute so much as this to that independent spirit in the judges which must be essential to the faithful performance of so arduous a duty.

This independence of the judges is equally requisite to guard the Constitution and the rights of individuals from the effects of those ill humors which the arts of designing men, or the influence of particular conjunctures, sometimes disseminate among the people themselves, and which, though they speedily give place to better information, and more deliberate reflection, have a tendency, in the meantime, to occasion dangerous innovations in the government, and serious oppressions of the minor party in the community. Though I trust the friends of the proposed Constitution will never concur with its enemies in questioning that fundamental principle of republican government which admits the right of the people to alter or abolish the established Constitution whenever they find it inconsistent with their happiness; yet it is not to be inferred from this principle that the representatives of the people, whenever a momentary inclination happens to lay hold of a majority of their constituents incompatible with the provisions in the existing Constitution would, on that account, be justifiable in a violation of those provisions; or that the courts would be under a greater obligation to connive at infractions in this shape than when they had proceeded wholly from the cabals of the representative body. Until the people have, by some solemn and authoritative act, annulled or changed the established form, it is binding upon themselves collectively, as well as individually; and no presumption, or even knowledge of their sentiments, can warrant their representatives in a departure from it prior to such an act. But it is easy to see that it would require an uncommon portion of fortitude in the judges to do their duty as faithful guardians of the Constitution, where legislative invasions of it had been instigated by the major voice of the community.

But it is not with a view to infractions of the Constitution only that the independence of the judges may be an essential safeguard against the effects of occasional ill humors in the society. These sometimes extend no farther than to the injury of the private rights of particular classes of citizens, by unjust and partial laws. Here also the firmness of the judicial magistracy is of vast importance in mitigating the severity and confining the operation of such laws. It not only serves to moderate the immediate mischiefs of those which may have been passed but it operates as a check upon the legislative body in passing them; who, perceiving that obstacles to the success of an iniquitous intention are to be expected from the scruples of the courts, are in a manner compelled, by the very motives of the injustice they meditate, to qualify their attempts. This is a circumstance calculated to have more influence upon the character of our governments than but few may be aware of. The benefits of the integrity and moderation of the judiciary have already been felt in more states than one; and though they may have displeased those whose sinister expectations they may have disappointed, they must have commanded the esteem and applause of all the virtuous and disinterested. Considerate men of every description ought to prize whatever will tend to beget or fortify that temper in the courts; as no man can be sure that he may not be tomorrow the victim of a spirit of injustice, by which he may be a gainer today. And every man must now feel that the inevitable tendency of such a spirit is to sap the foundations of public and private confidence and to introduce in its stead universal distrust and distress.

That inflexible and uniform adherence to the rights of the Constitution, and of individuals, which we perceive to be indispensable in the courts of justice, can certainly not be expected from judges who hold their offices by a temporary commission. Periodical appointments, however regulated, or by whomsoever made, would in some way or other, be fatal to their necessary independence. If the power of making them was committed either to the executive or legislature there would be danger of an improper complaisance to the branch which possessed it; if to both, there would be an unwillingness to hazard the displeasure of either; if to the people, or to persons chosen by them for the special purpose, there would be too great a disposition to consult popularity to justify a reliance that nothing would be consulted but the Constitution and the laws.

There is yet a further and a weighty reason for the permanency of the judicial offices which is deducible from the nature of the qualifications they require. It has been frequently remarked with great propriety that a voluminous code of laws is one of the inconveniences necessarily connected with the advantages of a free government. To avoid an arbitrary discretion in the courts, it is indispensable that they should be bound down by strict rules and precedents which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them; and it will readily be conceived from the variety of controversies which grow out of the folly and wickedness of mankind that the records of those precedents must unavoidably swell to a very considerable bulk and must demand long and laborious study to acquire a competent knowledge of them. Hence it is that there can be but few men in the society who will have sufficient skill in the laws to qualify them for the stations of judges. And making the proper deductions for the ordinary depravity of human nature, the number must be still smaller of those who unite the requisite integrity with the requisite knowledge. These considerations apprise us that the government can have no great option between fit characters; and that a temporary duration in office which would naturally discourage such characters from quitting a lucrative line of practice to accept a seat on the bench would have a tendency to throw the administration of justice into hands less able and less well qualified to conduct it with utility and dignity. In the present circumstances of this country and in those in which it is likely to be for a long time to come, the disadvantages on this score would be greater than they may at first sight appear; but it must be confessed that they are far inferior to those which present themselves under the other aspects of the subject.

Upon the whole, there can be no room to doubt that the convention acted wisely in copying from the models of those constitutions which have established good behavior as the tenure of their judicial offices, in point of duration; and that so far from being blamable on this account, their plan would have been inexcusably defective if it had wanted this important feature of good government. The experience of Great Britain affords an illustrious comment on the excellence of the institution.

1. Publius here quotes Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, XI, 6.

2. Article I, section 9 of the Constitution states that “No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed.” A bill of attainder is a law declaring an individual guilty of treason or other felony without a trial; an ex post facto law is a law that makes citizens vulnerable to prosecution for actions they took before the law was passed.

Federalist 78

- Constitution

- Federal Government

- Political Culture

- May 28, 1788

Introduction

This is the first of five essays by Publius (in this case, Hamilton) on the judiciary. The heart of this essay covers the case for the duration of judges in office. Publius points out that their lifetime appointments are guaranteed only “during good behavior.” He calls the insistence on this standard “one of the most valuable of the modern improvements in the practice of government.” To insure that judges maintain this standard, resisting encroachments from the legislature (to which presumably they would be vulnerable by means of bribes or threats), the Constitution gives them “permanent tenure.”

Publius then makes the famous claim that the judiciary “will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution. . . . It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL but merely judgment.” As “the weakest of the three departments of power,” it needs fortification.

It is the “duty” of the courts “to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the constitution void.” Without an independent judiciary to fulfill this task, any rights reserved to the people by the Constitution “would amount to nothing,” since the legislature cannot be relied upon to police itself. This arrangement does not render the judiciary the supreme branch of government. Rather, it ensures that the Constitution remain the supreme law of the land.

Publius’s argument here recognizes the possibility that in a representative government there are competing contenders to represent the people. Those elected to Congress rightly claim to act on the people’s authority; yet the Constitution, having been ratified by the people, itself represents the people’s will, and will have priority over more recently elected representatives. Publius contrasts this rule with that which applies in representative governments without a written constitution. In those systems, if a law is passed which contradicts an earlier law, judges are obliged to rule that the more recently passed law invalidates the first. But in a Constitutional system, any law contradicting the Constitution will be ruled invalid.

Implicitly, Publius recognizes the fallibility of the people and their representatives. He asserts, in effect, that the proposed Constitution insures that the careful, considered judgment of the Framers — made after considerable debate and compromise — will have priority over “dangerous innovations in the government” pushed by “designing men.”

He also predicts that a judicial branch with permanent tenure will discourage the appointment of incompetent or dishonest judges, while also preventing unconstitutional legislation from even being proposed.

Source: George W. Carey and James McClellan, eds., The Federalist: The Gideon Edition , (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001), 401-408.

We proceed now to an examination of the judiciary department of the proposed government.

In unfolding the defects of the existing Confederation, the utility and necessity of a federal judicature have been clearly pointed out. It is the less necessary to recapitulate the considerations there urged as the propriety of the institution in the abstract is not disputed; the only questions which have been raised being relative to the manner of constituting it, and to its extent. To these points, therefore, our observations shall be confined.

The manner of constituting it seems to embrace these several objects: 1st. The mode of appointing the judges. 2nd. The tenure by which they are to hold their places. 3d. The partition of the judiciary authority between different courts and their relations to each other.

First . As to the mode of appointing the judges: this is the same with that of appointing the officers of the Union in general and has been so fully discussed in the two last numbers that nothing can be said here which would not be useless repetition.

Second. As to the tenure by which the judges are to hold their places: this chiefly concerns their duration in office; the provisions for their support, and the precautions for their responsibility.

According to the plan of the convention, all the judges who may be appointed by the United States are to hold their offices during good behavior; which is conformable to the most approved of the State constitutions, and among the rest, to that of this State. Its propriety having been drawn into question by the adversaries of that plan is no light symptom of the rage for objection which disorders their imaginations and judgments. The standard of good behavior for the continuance in office of the judicial magistracy is certainly one of the most valuable of the modern improvements in the practice of government. In a monarchy it is an excellent barrier to the despotism of the prince; in a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body. And it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government to secure a steady, upright and impartial administration of the laws.

Whoever attentively considers the different departments of power must perceive that, in a government in which they are separated from each other, the judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them. The executive not only dispenses the honors but holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society, and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.

This simple view of the matter suggests several important consequences. It proves incontestably that the judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power; that it can never attack with success either of the other two; and that all possible care is requisite to enable it to defend itself against their attacks. It equally proves that though individual oppression may now and then proceed from the courts of justice, the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter: I mean, so long as the judiciary remains truly distinct from both the legislative and executive. For I agree that “there is no liberty if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers.” [1] And it proves, in the last place, that as liberty can have nothing to fear from the judiciary alone, but would have everything to fear from its union with either of the other departments; that as all the effects of such a union must ensue from a dependence of the former on the latter, notwithstanding a nominal and apparent separation; that as, from the natural feebleness of the judiciary, it is in continual jeopardy of being overpowered, awed or influenced by its coordinate branches; and that as nothing can contribute so much to its firmness and independence as permanency in office, this quality may therefore be justly regarded as an indispensable ingredient in its constitution, and in a great measure as the citadel of the public justice and the public security.

The complete independence of the courts of justice is peculiarly essential in a limited Constitution. By a limited Constitution, I understand one which contains certain specified exceptions to the legislative authority; such, for instance, as that it shall pass no bills of attainder, no ex post facto laws, [2] and the like. Limitations of this kind can be preserved in practice no other way than through the medium of the courts of justice, whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the Constitution void. Without this, all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing.

Some perplexity respecting the right of the courts to pronounce legislative acts void, because contrary to the Constitution, has arisen from an imagination that the doctrine would imply a superiority of the judiciary to the legislative power. It is urged that the authority which can declare the acts of another void must necessarily be superior to the one whose acts may be declared void. As this doctrine is of great importance in all the American constitutions, a brief discussion of the grounds on which it rests cannot be unacceptable.

There is no position which depends on clearer principles than that every act of a delegated authority, contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act therefore contrary to the constitution can be valid. To deny this would be to affirm that the deputy is greater than his principal; that the servant is above his master; that the representatives of the people are superior to the people themselves; that men acting by virtue of powers may do not only what their powers do not authorize, but what they forbid.

If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the constitutional judges of their own powers and that the construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the other departments it may be answered that this cannot be the natural presumption where it is not to be collected from any particular provisions in the Constitution. It is not otherwise to be supposed that the Constitution could intend to enable the representatives of the people to substitute their will to that of their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is in fact, and must be regarded by the judges as, a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course; to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Nor does this conclusion by any means suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both, and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the former. They ought to regulate their decisions by the fundamental laws rather than by those which are not fundamental.

This exercise of judicial discretion in determining between two contradictory laws is exemplified in a familiar instance. It not uncommonly happens that there are two statutes existing at one time, clashing in whole or in part with each other, and neither of them containing any repealing clause or expression. In such a case, it is the province of the courts to liquidate and fix their meaning and operation. So far as they can, by any fair construction, be reconciled to each other, reason and law conspire to dictate that this should be done; where this is impracticable, it becomes a matter of necessity to give effect to one in exclusion of the other. The rule which has obtained in the courts for determining their relative validity is that the last in order of time shall be preferred to the first. But this is mere rule of construction, not derived from any positive law but from the nature and reason of the thing. It is a rule not enjoined upon the courts by legislative provision but adopted by themselves, as consonant to truth and propriety, for the direction of their conduct as interpreters of the law. They thought it reasonable that between the interfering acts of an equal authority that which was the last indication of its will, should have the preference.

But in regard to the interfering acts of a superior and subordinate authority of an original and derivative power, the nature and reason of the thing indicate the converse of that rule as proper to be followed. They teach us that the prior act of a superior ought to be preferred to the subsequent act of an inferior and subordinate authority; and that, accordingly, whenever a particular statute contravenes the Constitution, it will be the duty of the judicial tribunals to adhere to the latter and disregard the former.

It can be of no weight to say that the courts, on the pretense of a repugnancy, may substitute their own pleasure to the constitutional intentions of the legislature. This might as well happen in the case of two contradictory statutes; or it might as well happen in every adjudication upon any single statute. The courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise WILL instead of JUDGMENT, the consequence would equally be the substitution of their pleasure to that of the legislative body. The observation, if it proved any thing, would prove that there ought to be no judges distinct from that body.