Work-Integrated Learning and Career Services

Cover letter writing, do you need a cover letter.

If you want to make a good impression, generally every resume should be accompanied by a cover letter. Your cover letter and resume should show why you would be a good fit for the organization, by introducing your talents and skills as they relate to the job posting.

Some people in the hiring process may not read the cover letter, but those who do read it really care about it. Some won’t read the resume if it did not come with a cover letter.

Types of Cover Letters

Invited letter.

- Used when responding to an advertisement

- Focused on matching your qualifications to the position requirements

I am applying for the position of (name of position) with (name of company) as advertised in the (name of newspaper, website, job board) on (date). With my experience in (related field) and my (name of studies), I possess the skills and knowledge required to be successful in this position.

Networking Letter

- Used when applying to an organization that does not have an advertised position

- Used to generate an informational meeting

- If a referral has been made, mention the person who referred you

- The name of a current employee/contact may catch the employer’s attention

In a recent conversation with Jane Doe, I learned of a possible opening in the (department). I am writing to express my interest in a (position name) with (company name). As you will see in the attached resume, my skills, abilities and experience make me an ideal candidate for this position.

Essential Elements

- Header – Include the phone number and an appropriate email address where you can be reached, and applicable online profiles (LinkedIn, portfolio, professional website)

- Address Block – Date of when you are submitting your application Employer’s address including the recipient’s full name and company name Subject line indicating the position name and/or reference number as advertised Salutation addressing a specific person or if unknown, consider using something neutral, naming the hiring team, or the person to whom the position reports to

- Opening – Invite the reader to read the rest of your cover letter, answering the employer’s question “Why should I hire you?”

- Middle – Summarizes your education, experience and skills according to the job requirements

- Closing – Express your interest, thank the reader appropriately, and wrap your letter up with a call to action – ask for an interview

- Signature Block – Includes complimentary closing (Sincerely,) and your printed name

Sample Middle Section

Putting it all together.

- Research the employer and position, and tailor your cover letter according to the requirements

- Write clearly and highlight both technical and soft skills

- Reflect your attitude, personality, motivation, and enthusiasm

- Indicate how you learned about the position or the organization

- Sound skilled and confident

- Proofread! Proofread! Proofread!

- Keep a copy of every letter you send out

Don’t

- Use a one-size-fits-all approach

- Focus on your own needs

- Mention your weaknesses

- Beg, demand or show desperation

- Overuse “I”, “me”, and “mine”

- Repeat your resume word for word

- Be vague when describing your background

- Paragraph Style – Create a paragraph(s) highlighting your qualifications using the statements from the My Accomplishments column

- Bullet Style – Create a bulleted list of qualifications using the statements from the My accomplishments column

- T Style – Create a table of qualifications using the Job Requirements and My Accomplishments columns

RRC Polytech campuses are located on the lands of Anishinaabe, Ininiwak, Anishininew, Dakota, and Dené, and the National Homeland of the Red River Métis.

We recognize and honour Treaty 3 Territory Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, the source of Winnipeg’s clean drinking water. In addition, we acknowledge Treaty Territories which provide us with access to electricity we use in both our personal and professional lives.

Learn more ›

- Skip to main content

- Skip to search

- Skip to footer

Center for Engaged Learning

Work-integrated learning.

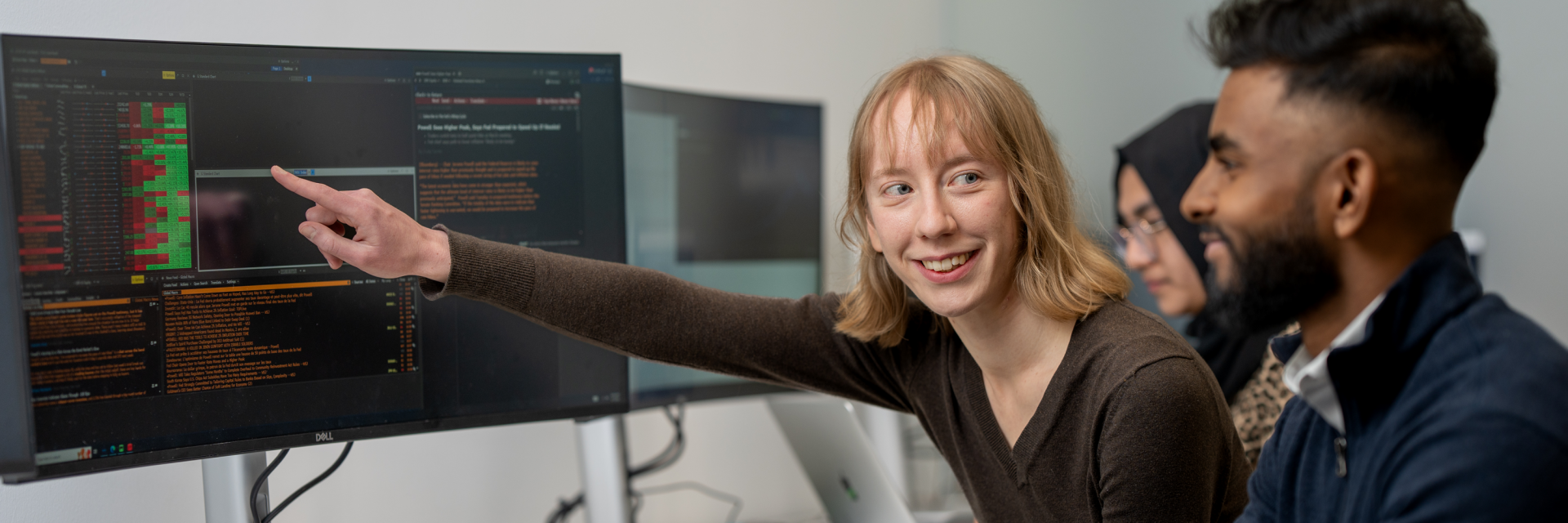

Work-integrated learning (WIL) is an approach to education that allows students to obtain work experiences related to what they are learning in a classroom setting (International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, n.d; Jackson 2016). Ferns, Campbell, and Zegwaard (2014) describe WIL as “a diverse concept designed to blend theoretical concepts with practice-based learning” (p. 2). This includes a variety of pedagogies:

- Internships allow students to be supervised by a professional in their field of study and are typically one-term work agreements that resemble what a traditional job might look like (Cooper et al. 2010; International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, n.d.; Virginia Tech 2019).

- Apprenticeships often allow students to engage in work before they begin their academics, and the institution might not be involved in the placement or the assessment of the student (Arnold 2011).

- Service-learning is an opportunity for students to carry out a service to a community while applying what they have learned in a classroom (Knight-McKenna, n.d.). Service-learning differs from volunteering as students are intentionally integrating course content.

- Practicums place students in a work setting to gain skills and competencies that are evaluated by a supervisor within that setting (Cooper et al. 2010). Students are required to have some form of training before completing the experience and often are required to take a specific course simultaneously with the experience (Cooper et al. 2010; International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, n.d.).

- Cooperative education is a work experience used for course credit, is specifically aligned with a student’s career goals, and maintains a focus on theory and practice (Cooper et al. 2010; International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, n.d.).

- Fieldwork allows students to observe and participate in work settings and has a focus on enhancing what the student is currently learning in the classroom (Bleakney 2019; Cooper et al. 2010).

The definitions and characteristics that constitute WIL include not only in-person WIL, but also non-physical, non-placement, online placement, or simulated WIL. This variety is particularly important when local, regional, or global factors limit students’, employers’, and employees’ access to regular workplace environments.

WIL experiences within higher education enable students to have opportunities to actively participate in their desired careers, ultimately preparing for professional employment. WIL programs and experiences initially catered to a handful of disciplines, specifically professional degree programs that spanned across education, law, and medicine (Brown 2010). With an emerging breadth of applicability within WIL, the academic and degree-oriented parameters have opened up opportunities for participation across disciplines. However, work-integrated learning experiences do not only have to be professional in nature. Students may opt to engage in service-learning opportunities, work with community-based learning organizations, or participate in other fieldwork, practicums or simulations (Cooper et al. 2010) within the context of their field of study (Kay et al. 2019; Papakonstantinou and Rayner 2015; Reid and Trigwell 1998). The variety in WIL placements allows for students to develop various skills and capacities, such as civic engagement, which can serve them well in society.

Back to Top

What makes it a high-impact practice?

WIL, as a field of knowledge, sees students as creative, social, and scholarly beings. In WIL, learning can be recognized as situated because what students learn depends on where they are and what tools are available for them to act and reflect on their experiences (Pennbrant and Svensson 2018). Students can understand the relevance of academic content, the emphasis on critical reflection, and the need for theoretical and practical learning, all while developing as professionals (Hay 2020).

However, these positive results can only be achieved when the WIL experience is a positive and high-quality one. Focusing on some of the eight identified key characteristics of high-impact practices (HIPs) (Kuh et al. 2017) and the six practices that foster student engagement (Moore 2021) makes it possible to observe where WIL is being done well, positively impacting students and their futures:

Fostering significant student investment and effort. WIL experiences generally require participating students to invest quite a large amount of their time and effort into the experience, taking initiative to develop their own expertise (Jackson 2016).

Facilitating relationships and building networks. WIL experiences create opportunities for students to make connections with professionals in their industry of interest. These connections allow students to establish professional networks from which they can draw resources, connections, and feedback (Jackson 2016; Moore 2021).

Offering connections to broader contexts and real-world applications of learning. Creating connections through WIL experiences justifies their learning and education (Kuh et al. 2017) and also helps students build faith in their own expertise (Jackson 2016; Zegwaard and McCurdy 2014). Students gain a broad insight into their chosen industry as well as a better understanding of attitudes, roles, and responsibilities of professional working environments (Jackson 2016).

Including opportunities for reflection and feedback. WIL experiences positively impact students the most when they are given opportunities to reflect on what they learned and how they will apply that new knowledge to their future (Hughes et al. 2013; Jackson 2015; Papakonstantinou and Rayner 2015; Zegwaard and McCurdy 2014).

Research-Informed Practices

Effective WIL design requires careful consideration of many factors and is widely acknowledged as both difficult and costly to implement for higher education institutions (Jackson 2015). Nevertheless, the following shared understandings/practices commonly found in successful work-integrated learning practices lead to meaningful learning opportunities:

- Preparation : Emphasis should be placed on preparing WIL partners and students by addressing administrative tasks, ensuring smooth communication, and creating awareness of requirements and expectations of both sides (Edwards et al. 2015; Fleming et al. 2018; Martin et al. 2011; Orrell 2011; Smith 2012).

- Curriculum : The curriculum must integrate with the needs of an industry and vice-versa, as well as identify learning outcomes, utilize assessment, and incorporate feedback to be effective (Bates 2005; Council on Higher Education 2011; McRae and Johnston 2016).

- Learning : The alignment of teaching and student activities with experiential components is necessary, so that students can apply academic learning to real-world settings and gain important industry and behavioral skills (Council on Higher Education 2011; Martin et al. 2011; Sachs et al. 2016; Smith 2012).

- Authenticity : Authenticity calls for ensuring that students be involved in an experience that replicates a real workplace setting, with equivalent requirements and expectations, appropriate levels of autonomy and responsibility, and meaningful consequences (Sachs et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2016).

- Flexibility: Institutions must seek diverse relationships with local employers to have opportunities for multiple fields of study, allow student some choice in the location and scope of the placement to best fit their daily lives, and support students’ professional development (Reid and Trigwell 1998; Kay et al. 2019).

- Broaden/advance skill set: Professional skills, effective communication, cooperation and teamwork, time management, and problem-solving are all skills that are considered essential to any profession and should be taught in WIL programs (Reid and Trigwell 1998; Papakonstantinou and Rayner 2015; Hughes et al. 2013). By broadening and advancing students’ skill sets, WILs set students up to be successful in any professional setting.

- Partnerships: Industry partners often are responsible for the workplace environment and introducing disciplinary innovations; institutions maintain accreditation and provide access to resources; and students negotiate intended outcomes for their work, particularly in “learner-led” partnerships (Reid and Trigwell 1998). Maintaining interaction among members in the three-way partnership ultimately allows for support and growth of students to be central.

- Supervision: Each WIL experience should have some sort of supervision from both the university and the workplace (Martin et al. 2011; Smith et al. 2016). Supervision provides a point of reference for the student at the university where they can turn for advice, support, and oversight (Martin et al. 2011), as well as a way to gain a responsive, nurturing, and educational relationship (Fleming et al. 2018; Smith 2012).

- Assessment: Assessments should reflect the complexity of the learning outcomes within an authentic workplace environment that promotes theory to practice learning (Jackson 2015; Martin et al. 2011).

- Reflection: Reflection is a vital practice that should be incorporated before, during (through learning circles and journaling), and after the experience, ideally in formats that allows students to look back and make sense of their journey (Jackson 2015; Smith et al. 2016).

Embedded and Emerging Questions for Research, Practice, and Theory

Boundaries and intersections.

There is no standard definition or model of WIL that is used across institutions. Common definitions for WIL may be useful within particular academic disciplines or industries to ensure that necessary learning objectives and skills are being obtained. Studies, such as Stewart and Chen (2009), note that without a standardized model for WIL, it is difficult to ensure students have a worthwhile experience. For instance, supervisors who are not given guidelines for hosting an intern or apprentice may not provide an opportunity that enables the student to thrive or develop a sense of professional self. Therefore, research should continue to explore ideal outcomes or skills gained through WIL, whether for disciplinary WIL experiences or cross-disciplinary WIL, even if the approach taken varies.

WIL both intersects with and is challenged by other high-impact practices (HIPs). Completing research with a faculty member could be considered WIL if it is treated as a job, but it could also be viewed as a barrier to engaging in other WIL opportunities. For instance, degree programs, HIPs, and other educational experiences that can take a great deal of time can limit opportunities for internships or other forms of professional practice (Schnoes et al. 2018). It is important to acknowledge that lack of participation in WIL does not mean that a student is not having a fully enriching experience. How can institutions balance the need for professional preparation (often through WIL) with undergraduate research experiences and other academic demands? A common goal exists between these various HIPs, that of strengthening the skill set of students and adding real-world application, so all should be considered in relation to one another.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for all programs to adapt their offerings to make them more accessible and equitable for learners and employers. Even before the outbreak of COVID-19, Kay et al. (2019) explored emerging models of WIL that are grounded in expanding engagement with the community, establishing flexibility in the programs, and creating equitable experiences for students by using technology.

A few of the adapted models that are considered to be more equitable for students are programs such as micro-placements (placements in a workplace that last two to ten days where students work on a highly focused project), virtual options, and working in incubators (places that support start-ups and emerging businesses and where students can support the new business as they begin their venture).

Scholars and practitioners agree that WIL experiences benefit all students, and underserved and underrepresented students often experience even greater gains from these opportunities (Brown 2010; Dean et al. 2021; Ferns et al. 2014; Jackson 2015; Kay et al. 2019; Lester and Costley 2010). Some student populations are more likely to encounter barriers to participating in WIL, though. For example, students with families often are not only balancing student and worker roles, but also extra family-care responsibilities. Income is a frequent barrier for participation in WIL; some programs tackle this with financial aid (Wake Technical Community College 2021), but there is still work to be done to minimize financial barriers.

Many universities have begun to search for more equitable means for providing WIL opportunities. Many of the adaptations and expansions seen so far have been focused on addressing two areas for students: time and access to locations. Virtual experiences and remote-work have become common-place alternatives to going to a workplace, especially as the pandemic endures. Schools need to consider the strain on students and resources as they carry out certain WIL programs, such as co-ops.

Another potential limitation may be the reason a program is created; while the goal is for WIL opportunities to be created for the benefit of the students, companies or organizations that register for or implement WIL programs often need the labor (Ferns et al. 2014; Cantor 1995; Kellogg Community College 2020) and sometimes may not prioritize professional development and learning for the student over their need to produce or function at low costs. This situation can result in interns or apprentices–often unpaid–being overworked for little personal gain or professional development.

Unpaid opportunities for students to engage in WIL are common but inherently inequitable. Itano-Bosse et al. (2021) suggested one mechanism for creating more accessibility within WIL is to provide funding for companies to take on students. One such challenge of sustaining WIL practices is funding—both for the work experiences and institutional support offered to each student. Unfortunately, there is not a singular solution for this challenge in any research conducted thus far. However, institutions are working individually to find solutions that allows students the opportunity to engage in WIL while also being fiscally responsible.

It is evident that much work needs to be done in order to provide WIL experiences that are accessible and sustainable.

Additional Future Research

WIL scholars and practitioners should continue to explore questions like:

- How does a student’s socioeconomic status impact their experience of WIL?

- What role does the quality and degree of mentorship and supervision play in the results of a WIL experience?

- What could a longitudinal study of students who took part in WIL illustrate about long-term impacts of WIL?

- How does when a student participates in WIL (e.g., class year) influence their access to and experience of WIL experiences?

Increasingly diverse student populations highlight the need for more research with specific student groups and identities—what are best practices for equity and access for all students, not just those with privilege and resources? Does—or should—effective WIL look different in minority-serving institutions than in predominantly white institutions? Does WIL look different for students with families, students with disabilities, students learning the local language, or students who are continuing their education after starting a career?

Ultimately, how can colleges best serve the students enrolled in their programs, acknowledging that those populations are changing?

Key Scholarship

Alanson, Erik R., Erin M. Alanson, Brittany Arthur, Aaron Burdette, Christopher Cooper, and Michael Sharp. 2020. “Re-envisioning Work-Integrated Learning During a Pandemic: Cincinnati’s Experiential Explorations Program.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 21 (5): 505-519.

About this Journal Article:

This study examines the array of WIL opportunities offered and how they were reimagined and adapted to fit the needs of the people involved during the COVID-19 global health crisis. The flexible and innovative measures taken by the University of Cincinnati to continue and improve upon their offerings show that, for UC, student well-being and the health and success of faculty-scholars, administrators, and students is of the utmost importance to them. While it is still too early to have conclusive evidence on the success of the newer programs, the fact that we can see how well-adapted these programs can be shows that Work-Integrated Learning can survive and thrive in the most turbulent times.

Batholmeus, Petrina, and Carver Pop. 2019. “Enablers of Work-Integrated Learning in Technical Vocational Education and Training Teacher Education.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 20 (2): 147-159.

This qualitative study defines and examines enabling factors in industry-based work-integrated learning (WIL) integration into technical-vocational education and training (TVET) teacher education in South African universities. The initiative is specifically designed for TVET lecturers because the WIL that schoolteachers would typically undertake in school placements is not relevant to preparing technical-vocational students for an industry workplace.

Brown, Natalie. 2010. “WIL [ling] to Share: An Institutional Conversation to Guide Policy and Practice in Work-Integrated Learning.” Higher Education Research & Development 29 (5): 507-518. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.502219 .

Through the implementation of a roundtable discussion of staff from various disciplines, Natalie Brown aimed to provide a space for University of Tasmania (UTAS) staff to recognize the potential and challenges of the practice of WIL. Understood as a way to provide students with an experience that integrates industry learning and academic coursework, WIL has been seen as beneficial to both students and industry members. While students can experience learning in context and enhance their employability, industry can participate in preparing graduates for a career. Yet, the absence of a general structure and collaboration in curriculum development allows gaps to remain within WIL opportunities.

Cantor, Jeffrey A. 1995. “Apprenticeships Link Community‐Technical Colleges and Business and Industry for Workforce Training.” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 19 (1): 47-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066892950190105 .

This article focuses on how apprenticeships build relationships between community/technical colleges and the workforce. Cantor completed a research study that examines how effective cooperative apprenticeships are and how they have successful outcomes for linking employers and the community college system. This study was a 2-year case study in which Cantor studied multiple apprenticeship programs that produced interesting findings about collaboration and why employers and community colleges work with each other. According to Cantor, collaborations occur mostly when partnerships derive mutual exchanges, partnerships access monies and resources, partnerships can mediate conflicts, and contractual relationships exist (p. 53). Cantor notes that the intentionality of apprenticeships is really valuable and doesn’t just benefit the student but also the stakeholders involved with the apprenticeship. Cantor closes the article with suggestions and recommendations for developing and expanding successful apprenticeship programs.

Christman, Scott. 2012. “Preparing for Success Through Apprenticeship.” Technology and Engineering Teacher 72 (1): 22-28.

This source provides a historical perspective of apprenticeships and then uses the Newport News Shipbuilding Company’s apprentice school as a case study, to look at the modern apprenticeship model and how students can benefit from these styles of programs. Christman wrote the article through the lens of a labor shortage in technical jobs within the engineering industry. The article provides an understanding of the apprenticeship system in the 21st century and recommends rethinking the current educational model to provide a complementary blend of college academic courses and career training with relevant work experiences.

Cooper, Lesley, Janice Orrell, and Margaret Bowden. 2010. Work Integrated Learning: A Guide to Effective Practice. Routledge.

About this Book:

Chapter 2 of Cooper, Orell, and Bowden’s book provides a definition of WIL, specifically defining some of the specific experiences of WIL. These terms include WIL experiences such as internships, practicums, and fieldwork. This definition is important given the fact that certain WIL experiences often overlap in terminology and can be confusing to differentiate at times. Additionally, the authors focus on specifically defining professional learning, service-learning, and cooperative learning as the three different models of WIL. Lastly, the authors describe the benefits and outcomes of WIL experiences for students. The most critical benefit of a WIL experience is that it allows students to put theory learned in the classroom setting into practice in the workplace. Upon reflection after completing a WIL experience, the integration of theory to practice is deepened and allows for tremendous professional growth within a student.

Dean, Bonnie A, Michelle J. Eady, and Hannah Milliken. 2021. “The Value of Embedding Work-Integrated Learning and Other Transitionary Supports into the First Year Curriculum: Perspectives of First Year Subject Coordinators.” Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability 12 (2): 51-64.

The authors sought to determine how WIL can be integrated into students’ experiences of transitioning to college during their first year. Ten Subject Coordinators were interviewed, and each participant was asked to explain how their subject supported first-year students’ transition into college and then asked about WIL. They found that most important experiences fall into either an academic or social category. Results show that the academic experience supports the first transition, social experiences support the second, and WIL can and should be implemented in the third transition, a student’s transition into becoming a professional .

Hughes, Karen, Aliisa Mylonas, and Pierre Benckendorff. 2013. “Students’ Reflections on Industry Placement: Comparing Four Undergraduate Work-Integrated Learning Streams.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 14 (4): 265-279.

Through the review of student reflections after the completion of their WIL program, Hughes et al. conclude that these opportunities for application-based professional development provide graduates with “a range of transferable skills and informed industry perspectives” (277). Students emphasized in their reflections the ability to put their coursework and subject knowledge into practice, recognizing the skills they held and potential areas of improvement. The immersion allowed students to recognize what industry professionals expected of their employees and understand what is needed to be successful in their discipline. Further, WIL students reflected upon their career choice as a whole, utilizing program experience to confirm the professional path they had selected and to recognize the culture surrounding the industry.

Jackson, Denise, and Nicholas Wilton. 2016. “Developing Career Management Competencies Among Undergraduates and the Role of Work-Integrated Learning.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (3): 266-286.

Denise Jackson and Nicholas Wilton’s research determines and evaluates the impact of WIL on the development of undergraduate students’ career management competencies. As a result of their research, the authors claim that work placements and other variations of WIL positively impact the development of opportunity awareness, decision-making learning, and transition learning. The research in this study was conducted by gathering data through self-assessment with an online survey.

Jackson, Denise. 2016. “Developing Pre-Professional Identity in Undergraduates Through Work-Integrated Learning.” Higher Education 74 (5): 833-853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0080-2 .

Jackson examines how work-integrated learning (WIL) enhances pre-professional identity in undergraduate students. Jackson finds that work placements positively affected the evolution of pre-professional identities. Students reported that personal reflection of their experience and appraisal were the most critical aspects of their WIL experience that strongly affected their pre-professional identities. Based on the triggers that were identified to progress pre-professional identities, Jackson also offers a variety of ways that practitioners can additionally enhance pre-professional identities in students. The author highlights that WIL allows students to understand expectations, attitudes, and responsibilities that are associated with their aspired profession, and progresses students professionally while they are still in college so that they are better prepared for their careers upon graduation.

Jackson, Denise. 2015. “Employability Skill Development in Work-Integrated Learning: Barriers and Best Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (2): 350-367. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.842221 .

Jackson defines WIL as “the practice of combining traditional academic study, or formal learning, with student exposure to the world-of-work in their chosen profession, has a core aim of better preparing undergraduates for entry into the workforce” (350). In this paper, Jackson explores the influence that the work placement design, content, and coordination had on the student’s development of employability skills. Facilitating WIL effectively, in a way that will benefit the future career of the student, requires careful planning to ensure that the student has the best possible experience while also learning from challenges. Jackson found that the students’ perceptions as to what was most important in their learning aligned with the principles for best practice for WIL design.

Kay, Judie, Sonia Ferns, Leoni Russell, Judith Smith, and Theresa Winchester-Seeto. 2019. “The Emerging Future: Innovative Models of Work-Integrated Learning.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 20 (4): 401-413.

WIL is becoming foundational to higher education experiences across various Australian universities. In order to develop a breadth of industry partners and implementation of this practice in various disciplines, Kay et al. examine how institutions are seeking to abide by shifting work cultures and making WIL programs more adaptable. By reviewing current literature and exploring emerging models alongside university WIL facilitators through semi-structured interviews, the researchers seek to understand new approaches to WIL. This reflection on WIL emphasizes the efforts of institutions to expand opportunities for engaged learning experiences for students.

O’Banion, Terry U. 2019. “A Brief History of Workforce Education in Community Colleges.” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 43 (3): 216-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1547668 .

O’Banion’s article provides the history of workforce education in community colleges. Additionally, he highlights the issues and four current developments of workforce education. Workforce education is very much embedded in community colleges, as many higher education leaders indicate that workforce education may be the primary purpose of a student even attending college, and especially in community college. O’Banion notes that vocational education became very prevalent in 2003, and has evolved through apprenticeship training, trade school, and career and technical education for the past one hundred years.

Papakonstantinou, Theo, and Gerry Rayner. 2015. “Student Perception of Their Workplace Preparedness: Making Work-Integrated Learning More Effective.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 16 (1): 23-24.

Wanting to learn more about how students in WIL placements felt about their employability and application of coursework once completing their program, Papkonstantinou and Rayner sought to gauge student perspectives through various surveys. Utilizing a Likert scale, a sample of Monash University students reflected upon their WIL experience and the obtained skills and value immediately after completing their placement through the survey, then completing a follow-up at least six months after.

See all Work-Integrated Learning entries

Model Programs

Community college of philadelphia.

The Community College of Philadelphia has worked with the District 1199C Training and Upgrading Fund and local government to create a work-integrated learning program for their Early Childhood Education degree program. This program was created to support high-quality, accelerated career pathways for daycare and other early childhood workers. The apprenticeship program allows full-time childcare workers who hold a Child Development Associate (CDA) certificate to earn an Associate’s degree in Early Childhood Education. This is a two-year program in which employees in local childcare centers receive 18 college credits for prior on-the-job learning along with wage increases and mentors.

The program has reported a 30% increase in overall wages for students who complete their apprenticeship. It also provides funding that covers students’ tuition costs and requires employers to offer fair wages with regular raises to correlate with the increasing skill development.

Delaware County Community College

The Delaware County Community College in Pennsylvania offers a plumbing apprenticeship certificate for individuals who are interested in gaining essential skills that would prepare them for an occupation in the field. Students who participate in this certificate program learn basic skills and the knowledge necessary for practicing in the area.

This certificate program allows flexibility for students by being a part-time program. Although some courses require prerequisites, students are able to complete the program at their own pace. Also, by requiring that students work with a master plumber, this community college is ensuring that students are exposed a diverse range of skills and knowledge. This program is a model for other initiatives because of its integration of HIP characteristics; master plumbers will be able to provide more constructive feedback and expect high performance, and they will ensure that their employees demonstrate competence through their work.

Wake Technical Community College

Wake Technical Community College’s WakeWorks Program allows students to earn a paycheck and professional training while earning a degree or professional credential in classes. Apprenticeship placements include apartment maintenance technicians, automotive system technicians, carpenters, electrical contractors, EMT/paramedics, HVAC technicians, plumbers, and tower technicians. The program, funded by the county, includes up to $1,000 in scholarship for tuition, fees, books, and tools; on-the-job training alongside classroom education; and a paycheck. The end result is the nationally recognized Journeyworker’s Certificate.

Since this program is not limited to degree-seeking students and provides both financial aid and income to participants, it is more accessible to diverse student populations. It also does not limit participation to students who live in Wake County, further extending its impact. The WakeWorks program aims to support local businesses as well by helping them meet staffing requirements with highly skilled employees when participants of the program graduate.

Kellogg Community College

Kellogg Community College offers a variety of apprenticeships for all the industrial trades curricula at the institution, including Industrial Electricity and Electronics, Industrial Machining Technology, Industrial Pipefitting, Renewable Energy, and Industrial Welding. Students participating in the apprenticeship programs are employed by locally registered companies. Students are typically enrolled in their apprenticeships for four years and are able to obtain over 8,000 hours of real work experience.

This program is especially notable because it is personalized to the student. Students are not required to obtain an apprenticeship, so if they would prefer to solely focus on their coursework, they are able to do so. Overall, students are able to leave the institution with an education that is debt-free and applicable experience that is valuable for their future careers.

The University of Cincinnati (UC)

The university has twelve types of WIL across its colleges and programs. UC set four markers of quality WIL: “Intentional (experiences are structured with trained educators as facilitators); Learner-centered and holistic (concerned with learning and growth of the student as a whole); Collaborative with the learner’s community or communities (contextualized to include real-world complexities, situated within real-world contexts); and Dependent on the inclusion of rigorous preflexive, reflexive, and reflective pedagogic strategies” (p. 507).

When the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020, UC was able to reexamine their long history of WIL and rebuild it in a framework that fits within the constraints of the pandemic. This adjustment brought to light new ventures such as virtual experiences, micro-co-ops, and upskilling (teaching employees additional skills to expand their capabilities).

For more information regarding all of the individual programs and the university’s response to COVID-19 as it relates to work-integrated learning, read Re-envisioning work-integrated learning during a pandemic: Cincinnati’s experiential explorations program .

University of Waikato

Researchers interviewed 18 students pursuing postgraduate degrees after having graduated from University of Waikato and found that students who took part in a work-integrated learning (WIL) degree reported that their experience positively influenced their decision to go on to postgraduate degrees. The students reported that the biggest influence was the opportunity to see the job they wanted in an authentic environment. As they learned the “hierarchy” of the lab environment, the students perceived that the more education a person had received, the more influence and credit they had in the research being done.

The practice of hands-on experience, mentorship, and reflectivity all make the University of Waikato’s WIL program a great example of WIL as a high-impact practice. For more information go to the University of Waikato’s WIL website .

The University of California at San Francisco

The Graduate Student Internships for Career Exploration (GSICE) program at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) offers hands-on work experiences in the form of three-month internships. These work opportunities are often outside a doctoral student’s specialized research area, as the program is intended to expose students to a variety of PhD-level careers beyond the traditional research postdoctoral position (postdoc).

The GSICE centers student needs in a two-part approach: (1) an eight-week course designed to build career-exploration and decision-making skills, and (2) the internship program. Numerous students cited that the course itself provided enough perspective to determine their career goals, so they opted not to complete an internship (Schnoes et al. 2018).

UCSF supports students taking full-time internships by providing leaves of absence, during which students do not have to pay tuition but still maintain health insurance and requiring that these full-time positions include remuneration. The GSICE also allows for students to complete part-time internships while enrolled or participate in post-graduation internships.

Australian Work-Integrated Research Higher Degree (WIRHD)

Within the realm of Australian higher education programs in engineering, the push towards work-integrated learning as an integral part of degree programs is due to the increased belief that PhD students are trained too narrowly and are not prepared to work in their industry outside of academia (Stewart and Chen 2009). The WIRHD enables students to spend a substantive amount of time with their industrial partner, learning from and working with professionals in their field of interest who are not pursuing academic research as a career.

Students serve as full-time research candidates instead of direct employees of their partners. This flexibility allows them to be a student first, and an employee second. On the other hand, challenges of the WIRHD program include increased isolation, lack of supervision, and time management. As the program develops, researchers hope a more normalized introductory course will set the standard so that company assignments are fair, and expectations are uniform for all students.

Related Blog Posts

Facilitating integration of and reflection on engaged and experiential learning.

Since 2019, I’ve been working with my colleague Paul Miller to create an institutional toolkit for fostering both students’ self-reflection and their mentoring conversations with peers, staff, and faculty in order to deepen students’ educational experiences. Our institution, Elon University,…

A Global Perspective: Interning While Studying Abroad

In my previous blog post, “Interning Abroad: Work-Integrated Learning in a Global Context,” I discussed the positive impact of having an internship while studying abroad as an undergraduate student. In this post, I would like to delve deeper into my…

Interning Abroad: Work-Integrated Learning in a Global Context

Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) focuses on integrating students’ course-based learning with real-world practical situations and experiences. Internships are a specific example of WIL that allow students to apply their academic studies to relevant experiences at companies, organizations, and nonprofits, small or…

View All Related Blog Posts

Featured Resources

Mentoring internships online or in hybrid/flex models.

In response to shifts to online learning due to COVID-19 in spring 2020 and in anticipation of alternate models for higher education in fall 2020 and beyond, we have curated publications and online resources that can help inform programmatic and…

Alanson, Erik R., Erin M. Alanson, Brittany Arthur, Aaron Burdette, Christopher Cooper, and Michael Sharp. 2020. “Re-envisioning Work-Integrated Learning During a Pandemic: Cincinnati’s Experiential Explorations Program.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 21 (5): 505–519.

Arnold, Christine, Peggy Sattler, and Richard Wiggers. 2011. “Combining Workplace Training with Postsecondary Education: The Spectrum of Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) Opportunities from Apprenticeship to Experiential Learning.” Canadian Apprenticeship Journal 19 (5): 1-33.

Bates, Lyndel. 2005. Building a Bridge Between University and Employment: Work-Integrated Learning . Research Brief No 2005/08. Queensland Parliamentary Library. https://documents.parliament.qld.gov.au/explore/researchpublications/researchbriefs/2005/200508.pdf

Batholmeus, Petrina, and Carver Pop. 2019. “Enablers of Work-Integrated Learning in Technical Vocational Education and Training Teacher Education.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 20 (2): 147–159.

Berzoff, Joan, and James Drisko. 2015. “Preparing PhD-Level Clinical Social Work Practitioners for the 21st Century.” Journal of Teaching in Social Work 35 (1-2): 82-100.

Billett, Stephen. 2009. “Realizing the Educational Worth of Integrating Work Experiences in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (7): 827-843.

Bleakney, Julia. 2019. “What Is Work-Integrated Learning?” Center for Engaged Learning (blog), Elon University. September 13, 2019. https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/what-is-work-integrated-learning/ .

Bowen, Tracey. 2016. “Depicting the Possible Self: Work-Integrated Learning Students’ Narratives on Learning to Become a Professional.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 17 (4): 399-411.

Bowen, Tracey. 2020. “Work-Integrated Learning Placements and Remote Working: Experiential Learning Online.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 21 (4): 377–386.

Brooks, Ruth. 2012. “Evaluating the Impact of Placements on Employability [Paper Presentation].” Employability, Enterprise and Citizenship in Higher Education 2012 Conference, Manchester, United Kingdom.

Brown, Natalie. 2010. “WIL [ling] to Share: An Institutional Conversation to Guide Policy and Practice in Work-Integrated Learning.” Higher Education Research & Development 29 (5): 507-518. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.502219 .

Cantor, Jeffrey A. 1995. “Apprenticeships Link Community‐Technical Colleges and Business and Industry for Workforce Training.” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 19 (1): 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066892950190105 .

Chilvers, Dominic, Kathryn Hay, Jane Maidment, and Raewyn Tudor. 2021. “The Contribution of Social Work Field Education to Work-Integrated Learning.” International Journal of Work – Integrated Learning 22 (4): 433-444.

Choy, Sarojni, and Brian Delahaye. 2011. “Partnerships Between Universities and Workplaces: Some Challenges for Work-Integrated Learning.” Studies in Continuing Education 33 (2): 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2010.546079 .

Christman, Scott. 2012. “Preparing for Success Through Apprenticeship.” Technology and Engineering Teacher 72 (1): 22-28.

Community College of Philadelphia. 2018. “A New Apprenticeship in Philadelphia Strengthens Education for Early Learners.” February 14, 2018. https://www.ccp.edu/about-us/news/news/new-apprenticeship-philadelphia-strengthens-education-early-learners .

Cooper, Lesley, Janice Orrell, and Margaret Bowden. 2010. Work Integrated Learning: A Guide to Effective Practice . Taylor & Francis Group.

Dean, Bonnie A., Michelle J. Eady, and Hannah Milliken. 2021. “The Value of Embedding Work-Integrated Learning and Other Transitionary Supports into the First Year Curriculum: Perspectives of First Year Subject Coordinators.” Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability 12 (2): 51–64.

Delaware County Community College. 2021. “Plumbing Apprenticeship Certificate.” https://catalog.dccc.edu/academic-programs/programs-study/plumbing-apprenticeship-certificate/ .

Dorasamy, Nirmala. 2012. “Reflections on Work Integrated Learning.” International Review of Qualitative Research 5 (1): 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2012.5.1.105 .

Eady, Michelle, Ina Machura, Radhika Jaidev, Kara Taczak, Michael-John Depalma, and Lilian Mina. 2021. “Writing Transfer and Work-Integrated Learning in Higher Education: Transnational Research Across Disciplines.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 2021 22 (2): 183-197.

Edwards, Daniel, Kate Perkins, Jacob Pearce, and Jennifer Hong. 2015. Work Integrated Learning in STEM in Australian Universities: Final Report. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). https://research.acer.edu.au/higher_education/44/ .

Ferns, Sonia, Matthew Campbell, and Karsten Zegwaard. 2014. “Work Integrated Learning.” In Work Integrated Learning in the Curriculum , edited by Sonia Ferns, 1–6. Milperra, Australia: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA).

Fleming, Jenny, Kathryn McLachlan, and T. Judene Pretti. 2018. “Successful Work-Integrated Learning Relationships: A Framework for Sustainability.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 19 (4): 321-335.

Fleming, Jenny, and T. Judene Pretti. 2019. “The Impact of Work-Integrated Learning Students on Workplace Dynamics.” Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sports and Tourism Education 25: 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.100209 .

Greer, A. Dominique, Abby Cathcart, and Larry Neale. 2016. “Helping Doctoral Students Teach: Transitioning to Early Career Academia Through Cognitive Apprenticeship.” Higher Education Research & Development 35 (4): 712-726. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1137873 .

Hay, Kathryn. 2020. “What Is Quality Work-Integrated Learning? Social Work Tertiary Educator Perspectives.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 21 (1): 51–61.

Hughes, Karen, Aliisa Mylonas, and Pierre Benckendorff. 2013. “Students’ Reflections on Industry Placement: Comparing Four Undergraduate Work-Integrated Learning Streams.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 14 (4): 265-279.

Itano-Bosse, Miki, Rochelle Wijesingha, Wendy Cukier, Ruby Latif, and Henrique Hon. 2021. “Exploring Diversity and Inclusion in Work-Integrated Learning: An Ecological Model Approach.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 22 (3): 253-368.

Jackson, Denise, and Nicholas Wilton. 2016. “Developing Career Management Competencies Among Undergraduates and the Role of Work-Integrated Learning.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (3): 266-286.

Jackson, Denise. 2016. “Developing Pre-Professional Identity in Undergraduates through Work-Integrated Learning.” Higher Education 74 (5): 833–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0080-2 .

Jackson, Denise. 2015. “Employability Skill Development in Work-Integrated Learning: Barriers and Best Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (2): 350-367. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.842221 .

Jacobs, James. 2009. “Meeting New Challenges and Demands for Workforce Education.” In Reinventing the Open Door: Transformational Strategies for Community Colleges , edited by Gunder Myran, 109–121. Washington, DC: Community College Press.

Kay, Judie, Sonia Ferns, Leoni Russell, Judith Smith, and Theresa Winchester-Seeto. 2019. “The Emerging Future: Innovative Models of Work-Integrated Learning.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 20 (4): 401-413.

Kellogg Community College. 2020. “Apprenticeship.” Accessed January 8, 2022. https://www.kellogg.edu/academics/departments/industrial-trades/apprenticeships/ .

Kuh George, Ken O’Donnell, and Carol Geary Schneider. 2017. “HIP’s at Ten.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 49 (5): 8-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2017.1366805 .

Mackaway, Jacqueline. 2016. “Students on the Edge: Stakeholder Conceptions of Diversity and Inclusion and Implications for Access to Work-Integrated Learning.” Refereed Proceedings of the 2nd International Research Symposium on Cooperative and Work-Integrated Education, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada : 105–114. University of Waikato.

Martin, Andy, Malcolm Rees, and Manvir Edwards. 2011. Work Integrated Learning: A Template for Good Practice: Supervisors’ Reflections . Wellington: Ako Aotearea. https://ako.ac.nz/assets/Knowledge-centre/RHPF-c43-Work-Integrated-Learning/RESEARCH-REPORT-Work-Integrated-Learning-A-Template-for-Good-Practice-Supervisors-Reflections.pdf .

McLennan, Belinda, and Shay Keating. 2008. “Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) in Australian Universities: The Challenges of Mainstreaming WIL [Paper Presentation].” Australian Learning and Teaching Council (ALTC) National Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services (NAGCAS) National Symposium 2008, Melbourne, Australia.

McRae, Norah, and Nancy Johnston. 2016. “The Development of a Proposed Global Work-Integrated Learning Framework.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 17 (4): 337-348.

McRae, Norah, and Karima Ramji. 2017. “Intercultural Competency Development Curriculum: A Strategy for Internationalizing Work-Integrated Learning for the 21st Century Global Village.” In Work-Integrated Learning in the 21 st Century: Global Perspectives on the Future , edited by Tracey Bowen and Maureen Drysdale, 129–143. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Moore, Jessie L. 2021. “Key Practices for Fostering Engaged Learning.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 53 (6): 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2021.1987787 .

O’Banion, Terry U. 2019. “A Brief History of Workforce Education in Community Colleges.” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 43 (3): 216–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1547668 .

Oktay, Julianne S., Jodi M. Jacobson, and Elizabeth Fisher. 2013. “Learning through Experience: The Transition from Doctoral Student to Social Work Educator.” Journal of Social Work Education 49 (2): 207-221.

Orrell, Janice. 2011. Good Practice Report: Work-Integrated Learning . Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Learning and Teaching Council. https://www.newcastle.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/90034/WIL-Good-Practice-Report.pdf .

Papakonstantinou, Theo, and Gerry Rayner. 2015. “Student Perception of Their Workplace Preparedness: Making Work-Integrated Learning More Effective.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education. 16 (1): 23-24.

Pennbrant, Sandra, and Lars Svensson. 2018. “Nursing and Learning: Healthcare Pedagogics and Work-Integrated Learning.” Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 8 (2): 179-194. http://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-08-2017-0048 .

Purdie, Fiona, Lisa Ward, Tina McAdie, Nigel King, and Maureen Drysdale. 2013. “Are Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) Students Better Equipped Psychologically for Work Post-Graduation Than Their Non-Work-Integrated Learning Peers? Some Initial Findings from a UK University.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 14 (2): 117-125.

Reid, Anna, and Keith Trigwell. 1998. “Introduction: Work-Based Learning and the Students’ Perspective.” Higher Education Research & Development 17 (2): 141-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436980170201 .

Rowe, Patricia. 2017. “Toward a Model of Work Experience in Work Integrated Learning.” In Work-Integrated Learning in the 21 st Century: Global Perspectives on the Future , edited by Tracey Bowen and Maureen Drysdale, 3-17. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Sachs, J., A. Rowe, and M. Wilson . 2016. Good Practice Report: Work Integrated Learning (WIL) . Dept of Education and Training (DET).

Schnoes, Alexandra, Anne Caliendo, Janice Morand, Teresa Dillinger, Michelle Naffziger-Hirsch, Bruce Moses, Jeffery Gibeling, Keith Yamamoto, Bill Landstädte, Richard McGee, and Theresa O’Brien. 2018. “Internship Experiences Contribute to Confident Career Decision Making for Doctoral Students in the Life Sciences.” CBE Life Sciences Education : 17 (1). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-08-0164 .

Siu, Kin Wai Michael. 2011. “Work-Integrated Learning in Postgraduate Design Research: Regional Collaboration Between the Chinese Mainland and Hong Kong.” In Work-Integrated Learning in Engineering, Built Environment and Technology: Diversity of Practice in Practice , edited by Patrick Keleher, Arun Patil, and R. E. Harreveld, 164-183. Hershey, PA: IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60960-547-6.ch008 .

Smith, Calvin. 2012. “Evaluating the Quality of Work-Integrated Learning Curricula: A Comprehensive Framework.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (2): 247-262.

Smith, Calvin, Sonia Ferns, and Leoni Russell. 2016. “Designing Work-Integrated Learning Placements that Improve Student Employability: Six Facets of the Curriculum that Matter.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 17 (2): 197-211.

Smith, Calvin, and Kate Worsfold. 2015. “Unpacking the Learning–Work Nexus: ‘Priming’ as Lever for High-Quality Learning Outcomes in Work-Integrated Learning Curricula.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (1): 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.806456 .

Snyder, Tom. 2017. “Apprenticeship Programs at Community Colleges.” The Blog – Huffington Post. December 6, 2017. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/tom-snyder/apprenticeship-programs-at-community-colleges_b_8918366.html .

Stewart, Rodney A., and Le Chen. 2009. “Developing a Framework for Work Integrated Research Higher Degree Studies in an Australian Engineering Context.” European Journal of Engineering Education 34 (2): 155-169.

Tesfai, Lul. 2019. “Creating Pathways to College Degrees Through Apprenticeships.” New America. September 19, 2019. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/creating-pathways-postsecondary-credentials-through-apprenticeships/ .

Trede, Franziska. 2012. “Role of Work-Integrated Learning in Developing Professionalism and Professional Identity.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 13 (3): 159–167.

Treptow, Reinhold. 2013. “The South African PhD: Insights from Employer Interviews.” Perspectives in Education 31 (2): 83-91.

Universities Australia, BCA, ACCI, AIG, and ACEN. 2015. “National Strategy on Work Integrated Learning in University Education.” http://cdn1.acen.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/National-WIL-Strategy-in-university-education-032015.pdf .

Valencia-Forrester, Faith. 2019. “Internships and the PhD: Is This the Future Direction of Work-Integrated Learning in Australia?” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 20 ( 4): 389-400.

Wake Technical Community College. 2021. “WakeWorks Apprenticeship .” https://www.waketech.edu/programs-courses/wakeworks/apprenticeship/ .

Warford, Laurance J. 2009. “Reinventing Career Pathways and Continuing Education.” In Reinventing the Open Door: Transformational Strategies for Community Colleges , edited by Gunder Myran, 122-138. Washington, DC: Community College Press.

Weldon, Anthony, and Jake K. Ngo. 2019. “The Effects of Work-Integrated Learning on Undergraduate Sports Coaching Students’ Perceived Self-Efficacy.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 20 (3): 309–319.

Winberg, Christine, Penelope Engel-Hills, James Garraway, and Cecila Jacobs. 2011. Work-Integrated Learning: Good Practice Guide. HE Monitor No. 12. Pretoria, South Africa: Council on Higher Education. https://www.theeducationscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CHE-Work-Integrated-Learning-Good-Practice-Guide.pdf .

Zegwaard, Karsten, and Susan McCurdy. 2014. “The Influence of Work-Integrated Learning on Motivation to Undertake Graduate Studies.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 15: 13-28.

The Center thanks the members of the 2023 cohort of the Elon University Masters of Arts in Higher Education program for contributing the initial content for this resource: Jordan Ballantyne, Kelsey Baron, Ivy Breivogel, Toni Formato, Mackenzie Hahn, Cotrayia Hardison, Martha Lopez Lavias, Charlie Presar, Sadie Richey, Odaly Rivas, Amy Smith, and Rebecca Wiles. The initial content was edited by Sophie Winston, the Center’s 2021-2022 Publishing Intern.

Work-integrated learning

Gain work experience with an industry partner for academic credit

- For students

- Careers and Employability

- Work experience

Work-integrated learning combines academic theory with meaningful workplace practice within the curriculum to help you develop your employability.

If you are in the final year of your coursework , work-integrated learning provides an opportunity to put theory into practice, develop your personal and professional skills, establish networks, and find out what it’s like to work in your area of study. It bridges the gap between your academic studies and your career.

Taking part in a WIL course will develop:

- an awareness of workplace culture and expectations

- a practical appreciation of your career

- industry insights

- experiences for your CV/job application

- career capability by gaining employability and transferable skills.

Entry requirements

To be eligible to take a work-integrated learning course, you must be in the final year of your degree program, with space to take an elective and a minimum overall GPA of 4. If you are organising your own internship, the proposed experience must meet minimum requirements and be approved as well. Once approved, you can enrol in the course.

Find out if you're eligible

First step is to complete the WIl Application form, to access the form go to the process for the WIL Applications via this link. The form will check your eligibility towards your program and you will find out if you are eligible to take a work-integrated learning course. If you are eligible, you will be provided with additional information about next steps to complete your application for your WIL course.

Important dates for Semester 1, 2024

Applications closed.

BEL work-integrated learning options

There are three different options for undertaking a work-integrated learning course. Learn about your options, the process for each and get in touch to express interest.

Find 100 hours of work experience related to your field of study with a host organisation, on-site or online.

Industry consulting project

Work in a team with other students and an industry partner online or on-campus over a semester.

- Capstone intensive

Work in a team with other students in a 2-week on-campus intensive.

Express Interest

Get in touch to let us know that you are interested. We can match you to opportunities as they become available or help you canvas for your own internship.

Upcoming WIL Consults

Book a consult with a WIL Adviser and Employability Specialist

BEL Work-integrated Learning (WIL) Group Consult

Bel career starter.

- Contact us / Book an appointment

- Internship for academic credit

- Industry project for academic credit

- Student Work Experience Program

- Career workshops

- Application support

- Connect with industry

- First-year students

- International students

- Upcoming events

BEL Careers and Employability

[email protected] +61 7 3365 4222 8:30am–4:30pm M-F Colin Clark Courtyard, Room 107

Thanks for starting your application to {{companyName}}.

To complete your application you must do one of the following:

Forward an email from your mobile device with your resume attached to {{fromEmail}}

Reply to this email from your laptop or desktop computer with your resume attached.

Thank you for your interest, The Recruiting Team

Reply to this email from your laptop or desktop computer with your cover letter attached.

In order to create an account with us and submit applications for positions with our company you must read the following Terms and Agreements and select to agree before registering.

In the event that you do not accept our Terms and Agreements you will not be able to submit applications for positions with our company.

You agree to the storage of all personal information, applications, attachments and draft applications within our system. Your personal and application data and any attached text or documentation are retained by Jibe Apply in accordance with our record retention policy and applicable laws.

You agree that all personal information, applications, attachments and draft applications created by you may be used by us for our recruitment purposes, including for automated job matching. It is specifically agreed that we will make use of all personal information, applications, attachments and draft applications for recruitment purposes only and will not make this information available to any third party unconnected with the our recruitment processes.

Your registration and access to our Careers Web Site indicates your acceptance of these Terms and Agreements.

Dear ${user.firstName},

Thanks for choosing to apply for a job with ${client.display.name}! Please verify ownership of your email address by clicking this link .

Alternatively, you can verify your account by pasting this URL into your browser: ${page.url}?id=${user.id}&ptoken=${user.token}

Please note that your job application will not be submitted to ${client.display.name} until you have successfully verified ownership of your email address.

The ${client.display.name} Recruiting Team

Nice to meet you. 👋

Lets quickly set up your profile

to start having tailored recommendations.

You agree to the storage of all personal information, applications, attachments and draft applications within our system. Your personal and application data and any attached text or documentation are retained by Sequoia Apply in accordance with our record retention policy and applicable laws.

This career site protects your privacy by adhering to the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). We will not use your data for any purpose to which you do not consent.

We store anonymized interaction data in an aggregated form about visitors and their experiences on our site using cookies and tracking mechanisms. We use this data to fix site defects and improve the general user experience.

We request use of your data for the following purposes:

Job Application Data

This site may collect sensitive personal information as a necessary part of a job application. The data is collected to support one or more job applications, or to match you to future job opportunities. This data is stored and retained for a default period of 12 months to support job matching or improve the user experience for additional job applications. The data for each application is transferred to the Applicant Tracking System in order to move the application through the hiring process. \nYou have the right to view, update, delete, export, or restrict further processing of your job application data. To exercise these rights, you can e-mail us at [email protected] . \nConversion Tracking \nWe store anonymized data on redirects to the career site that is used to measure the effectiveness of other vendors in sourcing job candidates.

Consent and Data Privacy

This application protects your privacy by adhering to the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Jibe will not use your data for any purpose to which you do not consent.\n

We request use of your data for the following purposes:\n \n User Authentication \n

\n This site retains personally identifiable information, specifically e-mail addresses, as a necessary part of user login. This data is retained for the duration of the user profile lifecycle and enables user authentication.\n

\n \n Usage Analytics \n

We store anonymized usage data to measure and improve the effectiveness of this CRM application in filling job requisitions and managing talent communities.\n

\n \n E-mails to Candidates \n

We collect your personal information such as name and email address. This information is used when you send marketing or contact emails to candidates.\n\n

Enter your email address to continue. You'll be asked to either log in or create a new account.

Need help finding the right job? Join our Talent Network

There was an error verifying your account. Please click here to return home and try again.

You are about to enter an assessment system which is proprietary software developed and produced by Kenexa Technology, Inc. The content in this questionnaire has been developed by Kenexa Technology, Inc., Kenexa’s Suppliers and/or Yum Restaurant Services Group, Inc.’s (“Company”) third party content providers and is protected by International Copyright Law. Under no condition may the content be copied, transmitted, reproduced or reconstructed, in whole or in part, in any form whatsoever, without express written consent by Kenexa Technology, Inc. or the applicable third party content provider. Under no circumstances will Kenexa Technology, Inc. be responsible for content created or provided by Company’s third party content providers.

IN NO EVENT SHALL KENEXA, AN IBM COMPANY, KENEXA’S SUPPLIERS OR THE COMPANY’S THIRD PARTY CONTENT PROVIDERS, BE LIABLE FOR ANY DAMANGES WHATSOEVER INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, DAMAGES FOR LOSS OF VOCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY ARISING OUT OF THE USE OF, THE PERFORMANCE OF, OR THE INABILITY TO USE THIS KENEXA ASSESSMENT SYSTEM OR THE CONTENT, REGARDLESS OF WHETHER OR NOT THEY HAVE BEEN ADVISED ABOUT THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES.

By clicking below, you are also confirming your identity for purposes of the questionnaire. You may not receive assistance, refer to any written material, or use a calculator (or similar device) while completing the questionnaire.

Unless otherwise directed by the Questionnaire Administrator, you are only authorized to take each requested questionnaire once. Failure to comply may result in disqualification. All Kenexa SelectorTM questionnaires are monitored.

- Received an offer letter? Here’s what’s next.

- You will be joining as a Scholar Trainee.

- Online Assessment (80 minutes)

- Aptitude Test - Verbal, Analytical, Quantitative (Each section has 20 minutes/ 20 questions)

- Written Communication Test (20 minutes)

- Upon selection in the Online Assessment, candidates will be required to go through Business Discussion Round

- 10th Standard: Pass

- 12th Standard: Pass

- Graduation – 60% or 6.0 CGPA and above as applicable by the University guidelines

- 2021, 2022 and 2023

- Bachelor of Computer Application - BCA

- Bachelor of Science- B.Sc. Eligible Streams-Computer Science, Information Technology, Mathematics, Statistics, Electronics and Physics

- Open school or distance education is allowed for 10th & 12th only.

- One Backlog is allowed at the time of Online Assessment.

- Candidates are expected to clear the backlogs along with the 6th semester.

- Mandatory to have studied Core Mathematics as one subject in Graduation.

- Business Maths & Applied Maths will NOT be considered as Core Mathematics in Graduation.

- Max 3 years of GAP in education allowed (between 10th to commencement of graduation).

- No Gaps are allowed in Graduation. Graduation should be completed within 3 years from the start of graduation.

- Should be an Indian Citizen or should hold a PIO or OCI card, in the event of holding a passport of any other country.

- Bhutan and Nepal Nationals need to submit their citizenship certificate.

- Candidates will be invited for the test process, who have completed 3 months cool-off period.

A web browser is a piece of software on your computer. It lets you visit webpages and use web applications.

It's important to have the latest version of a browser. Newer browsers save you time, keep you safer, and let you do more online.

Try a different browser - all are free and easy to install. Visit whatbrowser.org for more information.

If you are using a later version of Internet Explorer, please make sure you are not in compatibility mode of an older version of the browser.

- Business ethics

- Equal opportunities

- Inclusion and diversity

- Sustainability

- Life at Wipro

- Spirit of Wipro

- Leadership blogs

- Work environment

- Meet our people

Featured careers

- Technology careers

- Delivery careers

- Digital careers

- Consulting careers

- Sales careers

- Digital operations and platforms

- Corporate functions careers

- Walk-in at Wipro

- Begin Again careers

- Hiring of Persons with Disabilities

- Work Integrated Learning Program

- Legal Program

- Campus Global

- Elite - National Talent Hunt

- Join our talent network!

- Campus careers

- India careers

- USA careers

- Global careers

- Europe & Africa

- UK & Ireland

- Continental Europe

- Be Bold Network

- Asia & Australia

- Middle East

- English (US)

Work Integrated Learning Program 2023

Planning out your future is not always easy! Do you opt for higher education, or should you start working right away? The first option boosts your career but will mean an upfront investment. The latter enables you to get a head start on your career — but what about future growth? And there’s always the uncertainty of finding the right job at the right time. The solution is simple. Wipro’s Work Integrated Learning Program 2023 offers BCA and BSc students a chance to do it all! Start working at Wipro while pursuing an M.Tech degree from a premier university. Here’s the best part — we sponsor your degree too. Interested?

Eligibility Criteria

Year of passing, qualification, other criteria, joining details, stipend details.

Period: (INR Per Month) 1st Year: You will receive a stipend of INR 15,000 + 488 (ESI) + Joining Bonus of Rs.75,000 along with the 1st month Stipend. 2nd Year: You will receive a stipend of INR 17,000 + 533 (ESI). 3rd Year: You will receive a stipend of INR 19,000 + 618 (ESI). 4th Year: You will receive a stipend of INR 23,000 One time Joining Bonus - 75000 INR Merge Bonuses for the 1st 3 years post completion of the M.Tech degree. Post the completion of the program, designation will be Senior Project Engineer and compensation will range from INR 6,00,000 p.a onwards depending on performance. Other Benefits: • M.Tech degree fully sponsored by Wipro. • Group Life Insurance of INR 14 Lakhs p.a • Group Personal Accident Cover of INR 12 lakhs p.a Performance Bonus is applicable only to full time employees recruited after successful completion of WILP program. Bonus details are mentioned below: End of 1st year: 1,00,000 to 1,50,000 End of 2nd year: 1,00,000 to 1,50,000 End of 3rd year: 1,00,000 to 1,50,000

Training Agreement

You will be required to sign a training agreement for 60 months upon joining. Please Note: You will be liable to pay a sum of INR 75,000 on pro rata basis if you leave the organisation before 5 years of the training agreement are up.

Selection Process

Every eligible candidate must go through below online assessment details appended for your reference..

It is entirely the responsibility of Wipro to permit/limit the participation of each candidate in the Work Integrated Learning Program 2023 recruitment process. Reservations Parameters and selection procedure belongs solely to the discretion of Wipro. Wipro is not obligated to disclose any information at any stage of the selection process. Wipro also reserves the right to make an initial offer if the provisionally selected candidate does not meet certain conditions, which are a prerequisite for employment. Wipro also reserves the right to be held liable to any candidate if he/she is found to be involved in any illegal activity, for example: misperception, fraud, production of illegal documents, etc. Wipro will inform candidates about the results of the recruitment by individual e-mails or other means of communication provided by individual candidates. Please note that at any stage, whether during your online test and/or interview process or upon joining the Company, if it is brought to our notice that you have indulged in malpractices or used illegal means to clear your online assessment, the Company shall withdraw or revoke the offer with immediate effect and we reserve our rights to take suitable action against you as we may deem fit. We are an Equal Opportunity Employer. All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, national origin, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability status, protected veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by law. Any complaints or concerns regarding unethical/unfair hiring practices should be directed to our Ombuds group www.wiproombuds.com

See jobs by:

If you encounter any suspicious mail, advertisements, or persons who offer jobs at Wipro, please email us at [email protected] . Do not email your resume to this ID as it is not monitored for resumes and career applications.

Any complaints or concerns regarding unethical/unfair hiring practices should be directed to our Ombuds Group at [email protected] We are an Equal Opportunity Employer. All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, caste, creed, religion, gender, marital status, age, ethnic and national origin, gender identity, gender expression, sexual orientation, political orientation, disability status, protected veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by law. Wipro is committed to creating an accessible, supportive, and inclusive workplace. Reasonable accommodation will be provided to all applicants including persons with disabilities, throughout the recruitment and selection process. Accommodations must be communicated in advance of the application, where possible, and will be reviewed on an individual basis. Wipro provides equal opportunities to all and values diversity.

- © 2024 Wipro Limited

- Privacy policy

- Terms of use

- Fraud awareness

- Hiring process

Cookies are used on this site to assist in continually improving the candidate experience and all the interaction data we store of our visitors is anonymous. Learn more about your rights on our Privacy Policy page.

- Feeling Distressed?

- A-Z Listing

- Academic Calendar

- People Directory

Work-Integrated Learning (WIL)

what is wil.

By definition, WIL is an educational practice that intentionally integrates academic study in the workplace or a simulated work environment. Students reinforce their learning outcomes and academic theories through practical applications that are relevant to industry or community partners' needs.

EXPLORE TYPES OF WIL

How Does WIL Work?

- WIL is all about innovation. Students work with project partners to develop new solutions to emerging problems that impact industry and/or community stakeholders. Under faculty supervision, the student-driven ideas are presented to the project collaborators with the possibility of implementation. Read what our partners are saying .