These tables present detailed data on the demographic characteristics, educational history, sources of financial support, and postgraduation plans of doctorate recipients. Explore the Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED) data further via the interactive data tool and the new Restricted Data Analysis System . Kelly Kang Survey Manager, SED Human Resources Statistics Program, NCSES

- All Formats (.zip 6.7 MB)

- PDF (.zip 5.8 MB)

- Excel (.zip 871 KB)

- MORE DOWNLOADS OPTIONS

Doctorate recipients from U.S. colleges and universities

Doctorate-granting institutions, field and demographic characteristics of doctorate recipients, educational history of doctorate recipients, financial support for graduate education of doctorate recipients, postgraduation commitments of doctorate recipients, statistical profile of doctorate recipients.

Typical Graduate Student Age [Data for Average Age]

Graduate students can come straight from undergraduate study or they can be a little bit older after spending some time in industry. No matter what the subject you’ll find a wide variety of graduate student demographics and ages.

According to the OECD, the average age of master’s students is 24 and the average age of PhD entry is 27. In the US the average age of students studying for a graduate degree is 33 years old with a 22% of the graduates being over 40 years old.

In my experience, there has often been a wide variety of ages in grad school. In both my masters and my PhD years I was working alongside some mature age students. No matter the age, I enjoyed working alongside all students who were able to support each other during their studies.

If you are worried that you are too old to enter grad school and return to school, fear not.

As long as you enter your course with an apprentice mindset, do not look down on those who are younger than you, and work collaboratively you will likely have a fantastic time.

If you’d like to watch my YouTube video about this subject you can check it out in the link below.

In this article, we will look at the average age of graduate students and the data presented for master’s and PhD students by universities.

Grad Student Ages – Average ages?

According to some online sources, the average graduate student today is 33 years old, although students in doctoral programs are a bit older on average.

However, the average graduate student in the United States is typically between 22 and 28 years old. There are often 30’s and 40’s around, as well as super-brilliant under-21’s.

Some people decide to go back to university after some time in their careers because through their work or life experience they realise that they need or want an advanced degree to further their careers.

According to the data provided by Louisiana State University, the average age at which a student achieves a masters degree is of over 430 international student advising centres in more than 80 countries, the average age of a US graduate student is 31 years.

Here are some more graphs that will show you the median age of different students in a variety of institutions.

South-eastern University

Here is the distribution of students from south-eastern University in 2021 .

You’ll notice that there is a bimodal distribution. That is, a number of graduate students are between the ages of 22 and 24 but there is also a peak between 40 and 49.

This is likely due to the fact that the second peak is due to those who have entered a professional career and want a career change or to up-skill in their current role.

The University of British Columbia

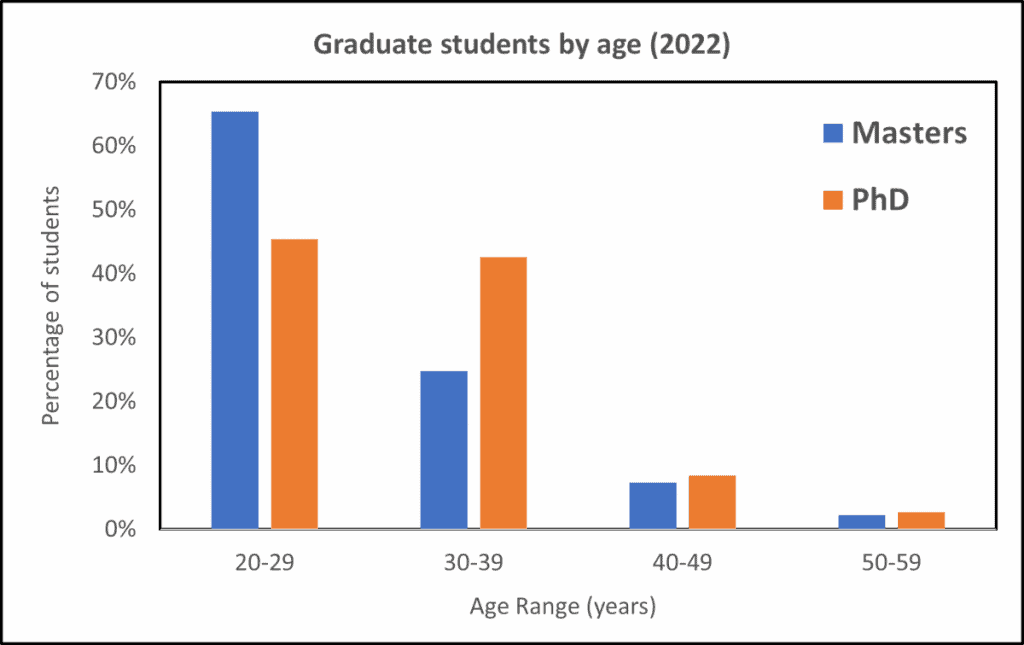

The University of British Colombia in Vancouver also presented their 2022 cohort demographic statistics for Masters and PhD students between the ages of 20 and 60.

You can see the results of this in the graph below.

Age at completion of doctoral degree

Lastly, in the table below we have the median age at doctorate for a number of fields and demographic characteristics in the United States of America.

You can see that the average PhD age for completion is 31.5 in the United States. The US has a much older cohort upon completion because their degrees typically take 5 to 7 years because there is a large coursework component at the beginning of their PhD.

I graduated from my PhD when I was 25. I did my undergraduate which included a Masters year. That means my undergraduate was done in four years. Then, I moved to Australia to do a PhD as an international student which meant I needed to be finished in three years.

Therefore I did my undergraduate, masters, PhD in seven years total. That is pretty much as fast as anyone can do it.

However, it is not a race and some people benefit greatly from taking their time, doing part or all of their education part-time, or waiting until they are financially stable before returning to their studies.

Why People Wait to Get Graduate Degrees

There are a number of reasons why people wait to get graduate degrees.

For many, it’s a matter of finishing up their undergraduate degree and taking some time to transition into the workforce before then re-enrolling in a graduate program to improve skills that they can then use to access higher pay scales in their current role.

For others, it’s a question of work experience – they want to be sure they’re making the most of their time and earning potential before going back to school.

And for the majority of students, it’s simply a question of finances. College is expensive, and many students graduate with a lot of debt. Going back to school for a graduate degree can add even more debt to that total.

But there are also plenty of people who go back to school for their graduate degree right after finishing their undergraduate degree. For some, it’s a matter of getting into the program they really want or earning a higher salary. For others, it’s simply a passion for learning. Whatever the reason, there are plenty of people who choose to go back to school immediately after finishing their undergraduate degree.

Will graduate schools care how old you are?

Graduate schools may care about your age if you’re an undergrad student applying to a graduate program. Sometimes a graduate program requires some professional experience so that you can get the most out of your program.

If you have work experience, your age may not be as important to admission committees. However, if you’re exploring a new field or degree, your advisor or the admissions committee may feel that your age puts you at a disadvantage.

In science programs, for example, research experience is often a requirement for admission, and mature students may have an easier time completing this requirement. Some programs also prefer or require that their students be of a certain age range. Your advisor can tell you more about the requirements of specific programs.

Are you too old for a graduate degree?

The answer is no, you are never too old to get a graduate degree. In fact, according to National Center for Education Statistics, the average age of graduate students is 33 years old.

This means that 1 in 5 students is over the age of 40!

So don’t worry, there are plenty of people in your situation.

Just remember that grad school is not for everyone, so make sure you really think about what you want to get out of it before making a decision.

You can be any age and still get a graduate degree. There are many benefits to getting a graduate degree, such as improved job prospects and increased earnings potential. If you are thinking about going back to school, then you should definitely consider getting a graduate degree.

Wrapping up

This article has been through everything you need to know about a typical graduate student age and has presented some data for various institution’s graduate students.

Ultimately, as long as graduate school is something that you see value in and you are willing to spend the time, money, and effort in getting your next qualification it could be a valuable addition to your CV.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138

- The Age of New Humanities Ph.D.'s

- K - 12 Education

- Higher Education

- Funding and Research

- Public Life

- Associate’s Degrees in the Liberal Arts and Humanities

- Demographics of Associate’s Degree Recipients in the Humanities

- Bachelor’s Degrees in the Humanities

- Humanities Bachelor’s Degrees as a Second Major

- Disciplinary Distribution of Bachelor’s Degrees in the Humanities

- Institutional Distribution of Bachelor's Degrees in the Humanities

- Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Bachelor's Degrees in the Humanities

- Gender Distribution of Bachelor’s Degrees in the Humanities

- Most Frequently Taken College Courses

- Postsecondary Course-Taking in Languages Other than English

- Advanced Degrees in the Humanities

- Humanities’ Share of All Advanced Degrees Conferred

- Disciplinary Distribution of Advanced Degrees in the Humanities

- Institutional Distribution of Master’s Degrees in the Humanities

- Institutional Distribution of Doctoral Degrees in the Humanities

- Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Advanced Degrees in the Humanities

- Years to Attainment of a Humanities Doctorate

- Gender Distribution of Advanced Degrees in the Humanities

- The Relationship between Funding and Time to Ph.D.

- Paying for Doctoral Study in the Humanities

- Debt and Doctoral Study in the Humanities

- Attrition in Humanities Doctorate Programs

- The Interdisciplinary Humanities Ph.D.

- English Language and Literature Degree Completions

- Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Degrees in English Language and Literature

- Gender Distribution of Degrees in English Language and Literature

- History Degree Completions

- Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Degrees in History

- Gender Distribution of Degrees in History

- Degree Completions in Languages and Literatures Other than English

- Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Degrees in Languages and Literatures Other than English

- Gender Distribution of Degrees in Languages and Literatures Other than English

- Philosophy Degree Completions

- Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Degrees in Philosophy

- Gender Distribution of Degrees in Philosophy

- Degree Completions in the Academic Study of Religion

- Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Degrees in Religion

- Gender Distribution of Degrees in Religion

- Humanities Degree Completions: An International Comparison

- U.S. Students Pursuing Study Abroad

The Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED) reveals that the median age of humanities and arts students who completed a Ph.D. in 2020 was almost three years higher than for doctorate recipients in general, with a comparatively large share of older students earning the degree. This may come as little surprise, since doctoral students in the humanities and arts tend to take longer to complete a Ph.D. than their counterparts in other fields . However, the gap in age at completion is not fully explained by the difference in time to completion, as doctorate recipients in the humanities and arts spend only about one year longer in their doctoral programs than students earning a Ph.D. in other fields.

( Note: These indicators present data for Ph.D.’s in both the humanities and the arts, which the National Science Foundation’s National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics combines in its public reporting of findings from the SED. But because the humanities produce substantially more PhDs each year than the fine/performing arts , the SED provides useful insight about the state of doctoral education in the humanities.)

- The median age of new humanities and arts Ph.D.’s was 34.2 years in 2020—almost three years older than the median among new doctorate recipients generally (31.5 years; Indicator II-28a ). Only doctoral degree recipients in education had a higher median age (38.5 years).

- From 1994 to 2020, the median age of new doctoral degree recipients in all fields combined declined by 2.6 years, from 34.1 to 31.5. In the humanities and arts, the median age fell by 1.5 years, from 35.7 to 34.2—similar to every other field except education, where the median fell by more than five years (from 43.6 to 38.5).

- In the humanities and arts, 22% of new doctoral degree recipients in 2020 were age 30 or younger, as compared to 68% of the graduates in physical/earth sciences and 36% of those in the behavioral/social sciences ( Indicator II-28b ). A substantial plurality of new Ph.D.’s in the humanities and arts, 39%, were ages 31–35—the largest share in that age group for any field. Another 18% of humanities and arts Ph.D.’s were over 40. The only field with a larger share of degree recipients over 40 was education.

- Throughout the 2010–2020 time period, the median age of women earning humanities and arts Ph.D.’s was modestly lower than that of men (33.8 years versus 34.4 years in 2020; findings not visualized). Similarly, a comparison of the broad disciplinary categories within the humanities employed by the data collector 1 revealed only small differences in age at receipt of the doctorate across the ten-year period.

- 1 The compared disciplines are history, languages and literatures other than English, and “Letters.” The latter encompasses: American literature (U.S. and Canada); classics; comparative literature; creative writing; English language; English literature (British and Commonwealth); rhetoric and composition; and speech and rhetorical studies.

* Includes agricultural sciences and natural resources; biological and biomedical sciences; and health sciences. ** Includes earth, computer, and information sciences, as well as mathematics. The latter three fields were reported separately beginning in 2015.

Source: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities (Data Tables, Years 1994–2020), https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/doctorates (accessed 2/15/2022). Table numbers for years: 1994 to 1998—A-3a; 1999 to 2001, 2005—18; 2002 to 2004—17; 2006, 2008—20; 2007 (included in 2008 report)—S-20; 2009—24; and 2010 to 2020—27. Data presented by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Humanities Indicators ( www.humanitiesindicators.org ).

The data on which this indicator is based are collected as part of the federal Survey of Earned Doctorates , a national census of recently graduated doctorate recipients.

For additional indicators related to the completion of a doctorate in the humanities, see “Debt and Doctoral Study in the Humanities,” “Years to Attainment of a Humanities Doctorate,” “Paying for Doctoral Study in the Humanities,” and “Attrition in Humanities Doctorate Programs.”

For trends in the number of doctorate completions in the humanities, see “Advanced Degrees in the Humanities.”

* Includes agricultural sciences and natural resources; biological and biomedical sciences; and health sciences.

Source: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Earned Doctorates (custom tabulation prepared for the Humanities Indicators by RTI in November 2021). Data presented by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Humanities Indicators ( www.humanitiesindicators.org ).

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Taking On the Ph.D. Later in Life

By Mark Miller

- April 15, 2016

ROBERT HEVEY was fascinated by gardening as a child, but then he grew up and took a 30-year career detour. Mr. Hevey earned a master’s in business and became a certified public accountant, working for accounting firms and businesses ranging from manufacturing to enterprise software and corporate restructuring.

“I went to college and made the mistake of getting an M.B.A. and a C.P.A.,” he recalled with a laugh.

Now 61, Mr. Hevey is making up for lost time. He’s a second-year Ph.D. student in a plant biology and conservation program offered jointly by Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden. Mr. Hevey, whose work focuses on invasive species, started on his master’s at age 53, and he expects to finish his doctorate around five years from now, when he will be 66.

“When I walk into a classroom of 20-year-olds, I do raise the average age a bit,” he says.

While the overall age of Ph.D. candidates has dropped in the last decade, about 14 percent of all doctoral recipients are over age 40, according to the National Science Foundation. Relatively few students work on Ph.D.s at Mr. Hevey’s age, but educators are seeing increasing enrollment in doctoral programs by students in their 40s and 50s. Many candidates hope doctorates will help them advance careers in business, government and nonprofit organizations; some, like Mr. Hevey, are headed for academic research or teaching positions.

At Cornell University, the trend is driven by women. The number of new female doctoral students age 36 or older was 44 percent higher last year than in 2009, according to Barbara Knuth, senior vice provost and dean of the graduate school.

“One of the shifts nationally is more emphasis on career paths that call for a Ph.D.,” Dr. Knuth said. “Part of it is that we have much more fluidity in career paths. It’s unusual for people to hold the same job for many years.”

“The people we see coming back have a variety of reasons,” she added. “It could be a personal interest or for career advancement. But they are very pragmatic and resilient: strong thinkers, willing to ask questions and take a risk in their lives.”

Many older doctoral candidates are motivated by a search for meaning, said Katrina Rogers, president of Fielding Graduate University in Santa Barbara, Calif., which offers programs exclusively for adult learners in psychology, human and organizational development and education.

“Students are asking what they can do with the rest of their lives, and how they can have an impact,” she said. “They are approaching graduate school as a learning process for challenging themselves intellectually, but also along cognitive and emotional lines.”

Making a home for older students also makes business sense for universities and colleges, said Barbara Vacarr, director of the higher education initiative at Encore.org, a nonprofit organization focused on midlife career change. “The convergence of an aging population and an undersupply of qualified traditional college students are both a call to action and an opportunity for higher education.”

Some schools are serving older students in midcareer with pragmatic doctoral programs that can be completed more quickly than the seven or eight years traditionally required to earn a Ph.D. Moreover, many of those do not require candidates to spend much time on campus or even leave their full-time jobs.

That flexibility can help with the cost of obtaining a doctorate. In traditional programs, costs can range from $20,000 a year to $50,000 or more — although for some, tuition expenses are offset by fellowships. The shorter programs are less costly. The total cost at Fielding, for example, is $60,000.

Susan Noyes, an occupational therapist in Portland, Me., with 20 years’ experience under her belt, returned to school at age 40 for a master’s degree in adult education at the University of Southern Maine, then pursued her Ph.D. at Lesley University in Cambridge, Mass. During that time, she continued to work full time and raise three children. She finished the master’s at 44 — a confidence-builder that persuaded her to work toward a Ph.D. in adult learning, which she earned at age 49.

Dr. Noyes, 53, made two visits annually to Lesley’s campus during her doctoral studies, usually for a week to 10 days. She now works as an assistant professor of occupational therapy at the University of Southern Maine.

At the outset of her graduate education, Dr. Noyes wasn’t looking for a career change. Instead, she wanted to update her skills and knowledge in the occupational therapy field. But she soon found herself excited by the chance to broaden her intellectual horizons. “I’ve often said I accidentally got my Ph.D.,” she said.

Lisa Goff took the traditional Ph.D. path, spending eight years getting her doctorate in history. An accomplished business journalist, she decided to pursue a master’s degree in history at the University of Virginia in 2001 while working on a book project. Later, she decided to keep going for her doctorate, which she earned in 2010, the year she turned 50. Her research is focused on cultural history, with a special interest in landscapes.

Dr. Goff had planned to use the degree to land a job in a museum, but at the time, museum budgets were being cut in the struggling economy. Instead, a university mentor persuaded her to give teaching a try. She started as an adjunct professor in the American studies department at the University of Virginia, which quickly led to a full-time nontenure-track position. This year, her fourth full year teaching, her position was converted to a tenure-track job.

“I thought an academic job would be grueling — not what I wanted at all,” she recalls. “But I love being in the classroom, finding ways to get students to contribute and build rapport with them.”

As a graduate student, she never found the age gap to be a challenge. “Professors never treated me as anything but another student, and the other students were great to me,” Dr. Goff said. The toughest part of the transition, she says, was the intellectual shock of returning to a rigorous academic environment. “I was surprised to see just how creaky my classroom muscles were,” she recalled. “I really struggled in that first class just to keep up.”

Mr. Hevey agrees, saying he has experienced more stress in his academic life than in the business world. “I’m using my brain in such a different way now. I’m learning something new every day.”

His advice to anyone considering a similar move? “Really ask yourself if this is something you want to do. If you think it would just be nice to be a student again, that’s wrong. It’s not a life of ease: You’ll be working all the time, perhaps for seven or eight years.”

Mr. Hevey does not expect to teach, but he does hope to work in a laboratory or do research. “I’m certainly not going to start a new career at 66 or 67,” he said. “But I’m not going to go home and sit on the couch, either.”

Make the most of your money. Every Monday get articles about retirement, saving for college, investing, new online financial services and much more. Sign up for the Your Money newsletter here .

Let Us Help You Plan for Retirement

The good news is that we’re living longer. the bad news is you need to save for all those future retirement years. we’re here to help..

For a growing number of older Americans, signing up for a mortgage that is most likely to outlive them makes good economic sense. But there are risks to consider .

If you’re on Medicare, you could save money on prescription drugs this year — in many cases, by thousands of dollars. Here’s why .

Entering your 40s can throw you into an emotional tailspin — one that may lead you to spend more and jeopardize your nest egg. Here is how to avoid that .

It’s difficult to know when to get help managing finances after you retire . Communicating with loved ones, even when you don’t want to, is the first step.

These days, many Americans thinking about retiring feel the stakes are higher than ever. We sought the advice of financial planners on some of the most pressing questions.

Retirement plan administrators are noting an uptick in 401(k) hardship withdrawals . But taking that money out can harm your future financial security.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- JCI Insight

- v.7(6); 2022 Mar 22

Gaps between college and starting an MD-PhD program are adding years to physician-scientist training time

Lawrence f. brass.

1 Department of Medicine, Department of Systems Pharmacology and Translational Therapeutics, and MD-PhD program, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Reiko Maki Fitzsimonds

2 Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology and MD-PhD program, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Myles H. Akabas

3 Departments of Physiology and Biophysics, Neuroscience, and Medicine and MD-PhD program, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, USA.

Associated Data

The average age when physician-scientists begin their career has been rising. Here, we focused on one contributor to this change: the increasingly common decision by candidates to postpone applying to MD-PhD programs until after college. This creates a time gap between college and medical school. Data were obtained from 3544 trainees in 73 programs, 72 program directors, and AAMC databases. From 2013 to 2020, the prevalence of gaps rose from 53% to 75%, with the time usually spent doing research. Gap prevalence for MD students also increased but not to the same extent and for different reasons. Differences by gender, underrepresented status, and program size were minimal. Most candidates who took a gap did so because they believed it would improve their chances of admission, but gaps were as common among those not accepted to MD-PhD programs as among those who were. Many program directors preferred candidates with gaps, believing without evidence that gaps reflects greater commitment. Although candidates with gaps were more likely to have a publication at the time of admission, gaps were not associated with a shorter time to degree nor have they been shown to improve outcomes. Together, these observations raise concerns that, by promoting gaps after college, current admissions practices have had unintended consequences without commensurate advantages.

Introduction

Integrated MD-PhD programs were developed in the 1950s to provide rigorous research training to future physician-scientists that is not part of the standard medical school curriculum ( 1 , 2 ). The earliest programs were few in number and limited in both size and diversity. Candidates to those programs typically applied after their junior year in college and began training within a few months of graduating from college. Since the 1950s, the national need for more physician-scientists and the contribution of MD-PhD programs to meeting that need has been recognized ( 3 – 5 ). As a result, substantial NIH and institutional resources have been invested to increase the number of programs, the number of trainees per program, and the diversity of students enrolled ( 3 , 6 , 7 ). At present, there are approximately 95 active programs, which we defined here as having at least 10 total trainees in the academic year ending in 2021 (AY2021). Fifty of the 95 programs were receiving National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) training support in the form of Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) T32 grants when this manuscript was being written ( 8 ). Nearly 6000 students are currently enrolled ( 9 ), and 600–700 new students begin training each year ( 2 , 10 ).

At the time that MD-PhD programs were expanding, there was considerable discussion about the limited number of undergraduates pursuing careers as physician-scientists ( 3 , 11 – 13 ). Several factors that dissuaded applicants were identified, including the extended training time, the increasing age at which physician-scientists establish independent research careers, the opportunity costs of extended training time, concerns about work/life imbalance, competition for faculty appointments with protected research time, and the challenges of sustaining a research career over many years ( 3 , 14 ). Total training time traditionally includes the time to degree in MD-PhD programs plus the time to complete postgraduate training. The duration of both has increased over the past few decades, such that trainees may not achieve an independent research position until they are in their late 30s or early 40s ( 2 , 13 , 15 ).

Here, we have focused on an underappreciated factor that increases the average age at which physician-scientists launch their independent careers: the growing tendency for undergraduates to postpone applying to MD-PhD programs until after they have finished college, rather than before their senior year. In 2020, two of the authors of the present study invited members of the National Association of MD-PhD Programs to participate in a pilot project to test their anecdotal impression that most students entering MD-PhD programs had waited to apply until after college. Twenty-two programs provided data that suggested that most entering students had done so. Based on that pilot, the present study was launched in early 2021, with invitations to participate sent to the directors of US MD-PhD programs. Most of the directors chose to participate, collectively representing 86% of the 5830 MD-PhD students enrolled in AY2021 and 49 of the 50 programs supported by NIGMS MSTP T32 grants ( 9 ). Participating programs were provided a school-specific link to an anonymous online survey to forward to their trainees. Participating trainees were asked when they graduated from college and when they started medical school. If there was a gap, they were asked why they had waited to apply, how they had used the time, from whom they had obtained advice, and whether they would recommend their choice to others. The survey also asked about their undergraduate research experience and publication record at the time that they applied to MD-PhD programs. A survey sent to directors asked whether their program’s application requested information about gaps and publications and, if they did, how they used this information in making decisions. Finally, we asked program directors for time-to-degree and gap length data for their recent graduates.

The surveys were completed by 3544 trainees (71%) and all but 1 program director. The results were combined with data on all applicants and matriculants obtained from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Matriculant Data File. The results of the trainee survey show that gap prevalence among successful MD-PhD program applicants has steadily increased over the past decade. Although other reasons were identified, the increase reflects a common impression among applicants that a gap spent doing research is necessary for a successful application. The directors’ survey showed that many programs do pay attention to whether an applicant had devoted time after graduation to research but not to the extent that many applicants believe. Notably, we found no evidence in either the literature or this study that gaps shorten the time to degree or improve performance during or after graduation. This does not mean that gaps have no value to individual applicants, just that they should not be viewed as a requirement for admission to an MD-PhD programs.

Online surveys were distributed to students in US MD-PhD programs and their program directors in early 2021. Copies of each survey are included in the Supplemental Methods (supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.156168DS1 The overall survey participation rate for MD-PhD program trainees was 71% (3544 of 5007 trainees in 73 programs, Supplemental Table 1 ). Average participation rates were slightly lower for large programs (≥100 students; 67% participation rate) than for small programs (<60 students; 75%) and for those programs with NIGMS MSTP T32 grants (70%) compared with those without (76%). 54% of participants identified as male, 44% as female, 0.8% as nonbinary, and 0.5% declined to answer; 15% identified themselves as members of one or more groups considered to be underrepresented in medicine (UIM, defined in Methods section). Results from the trainee survey were compared with data from the annual AAMC Matriculating Student Questionnaire (MSQ), which includes questions about time spent between college and medical school. Although the MSQ doesn’t separate answers from MD and MD-PhD students, it predominantly reflects MD candidates, who are approximately 97% of US medical school matriculants.

Gap prevalence has increased substantially.

Herein, we define a “gap” as the time between college graduation and matriculation into an MD-PhD program, with 0 years meaning that the student went straight from college into MD-PhD training with no time in between. Figure 1 illustrates gap prevalence, defined as the percentage of matriculating students who took a gap of ≥1 year, as a function of entry year from 2013 to 2020. The data show that gaps have become more prevalent for medical students in general during this period, but they are even more so for trainees in MD-PhD programs, rising from 53% among those who entered in 2013 to 75% for those who entered in 2020 ( Figure 1A ). Most of the upward trend is observed in those trainees who had a 1- or 2-year gap and not those whose gap lasted 3 or more years ( Figure 1B ).

( A ) Gap prevalence by matriculation year. Data on matriculating medical students (MD and MD-PhD) were obtained from the AAMC MSQ ( n = 12,779–16,668). MD-PhD data from current survey respondents (matriculation year 2013–2020, n = 306, 355, 391, 419, 424, 472, 451, and 519, respectively). ( B ) Shorter versus longer gaps by matriculation year. ( C ) Comparison of gap prevalence for current MD-PhD matriculants derived from present survey data with gap prevalence derived from AAMC data on all MD-PhD program matriculants from 2013–2020 ( n = 605–707/year, 5223 total). ( D ) Comparison of AAMC gap prevalence data for MD-PhD matriculants from 2013 to 2020 ( n = 605–707/ year, 5223 total) with gap prevalence data for those who were not accepted ( n = 957–1064/year, 8007 total). Comparison of gap duration for MD-PhD matriculants compared with those who were not admitted. ( E ) Average gap prevalence for trainees in NIGMS MSTP training grant-supported programs ( n = 49 programs, n = 3068 respondents, 70% participation rate) versus trainees from programs without MSTP grants ( n = 25 programs, n = 474 respondents, 76% participation rate) in 2021. Mean + SD. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles; lines within the boxes indicate medians, and whiskers indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. Points outside of whiskers are shown. Differences are not statistically significant by ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. ( F ) Programs were grouped by those with fewer than 60 trainees (group 1, n = 33 programs, n = 803 respondents, 75% participation rate), programs with 60–99 trainees (group 2, n = 26 programs, n = 1482 respondents, 72% participation rate), and programs with 100 or more trainees (group 3, n = 14 programs, n = 1257 respondents, 67% participation rate). Mean + SD. Differences are not statistically significant by 1-way ANOVA. ( G ) Gap prevalence by gender. NB, nonbinary; NA, declined to answer. ( H ) Gap prevalence by race/ethnicity. NA, declined to answer. ( G and H ) Parenthetical number represents total number of respondents in each group.

Because the survey data covered only 71% of current trainees, we also obtained deidentified AAMC data for all applicants to MD-PhD programs from 2013 to 2020. The data included the year applicants graduated from college, whether they matriculated into an MD-PhD program and the year they entered, and whether they were accepted somewhere or rejected everywhere. Figure 1C compares gap prevalence in the AAMC data set with data obtained in the present survey. The two curves are essentially superimposable, which suggests that there was little if any difference between those who responded to the present survey and those who did not with respect to gap prevalence. Figure 1D compares gap prevalence for those who matriculated into an MD-PhD program with those whose applications were unsuccessful. If anything, gap prevalence was greater among those who were not accepted than those who were, although this difference has gradually declined ( Figure 1D , left). When grouped by gap duration, unsuccessful applicants were more likely to have taken longer gaps ( Figure 1D , right).

The average gap prevalence by program for MD-PhD students varied considerably, ranging from 39% to 100%. There was no significant difference between programs currently funded by NIGMS MSTP T32 grants and those that are not, although the range of gap prevalence was wider in the programs that did not have NIGMS T32 funding (39%–100% vs. 48%–89%) ( Figure 1E ). There was also little difference by program size, gender, or self-identification as a member of a group considered to be UIM ( Figure 1, F–H ).

Gap length distribution.

The data in Figure 2 show the length of the gaps taken by current trainees who answered the survey. Among those who took a gap, durations of 1 or 2 years were by far the most common. Gaps lasting 3 or more years were reported by 629 of 3544 trainees (18%). There were no meaningful differences in gap length distribution by gender or among those who identified as belonging to groups considered to be UIM.

( A and C ) Total number of survey respondents in each group who had a gap of the indicated duration following college graduation. ( B and D ) Percentage of each group who took a gap of the indicated duration. Total number of survey respondents in each group is indicated in Figure 1 , G and H.

Prior research experience.

Figure 3 summarizes data on research experience and publications at the time of application. In general, students who had more research time in college (semesters and summers) were less likely to take a gap ( Figure 3, A and E ). Those who chose to not take a gap were more likely to have done research during the summer after their freshman year ( Figure 3, B and F ) and to have more total summers of research ( Figure 3, C and G ). Overall, 2205 of 3544 survey respondents (62%) reported having a publication at the time of application, with the likelihood of having a publication increasing among those with longer gaps ( Figure 3, D and H ). Each of these differences remained consistent across comparisons by gender and membership in groups considered to be UIM.

Survey respondents were divided into those with no gap ( n = 1196), a 1- to 2-year gap ( n = 1719), and a gap of ≥3 years ( n = 629). ( A–D ) Comparison of women ( n = 1574) and men ( n = 1923). ( E–H ) Comparison of those from groups considered to be underrepresented in medicine (UIM) ( n = 545) to those who are not (non-UIM) ( n = 2868). ( A and E ) Average number of semesters of research during college. ( B and F ) Percentage of those surveyed who reported a summer research experience between freshman and sophomore years. ( C and G ) Average number of summers of research. ( D and H ) Percentage of those surveyed who reported having a publication at the time of submission of their MD-PhD program application.

Undergraduate major and the decision to do a gap.

Most current trainees in MD-PhD programs who responded to the survey indicated that their undergraduate degrees were in the biological sciences. Smaller numbers majored in the physical sciences ( Figure 4A ). The smallest group consisted of those who were social science majors in college. Gap prevalence was greatest (82%) among the social sciences majors, who also tended toward longer gaps. Those who had been physical science majors were least likely to have a gap (61%) ( Figure 4B ).

( A ) Percentage of students reporting an indicated undergraduate major from a dropdown list of majors. Number of respondents and percentage of total ( n = 3544). ( B ) Respondent’s majors were grouped into three categories: social sciences (includes humanities, social sciences, and psychology), biological sciences, and physical sciences (includes chemistry, computer sciences, engineering, mathematics, and physics). The percentage of students in a given category who had no gap (blue), a 1- to 2-year gap (orange), or a gap of 3 or more years (gray) is shown. The total number of students in each category is shown in parentheses. Note that the number of students with majors in the social sciences is much smaller than in the other two categories.

Why did you do a gap?

A large part of the trainee survey focused on the decision to do a gap. Trainees who had taken a gap were asked to select from a predefined list of possible reasons. Their choices are summarized in Table 1 . They were also given the opportunity to select “other” and write in additional reasons ( Supplemental Table 2 ). Multiple selections were allowed, but in a subsequent question they were also asked to identify which of their selections they considered to be the primary reason. The most frequently selected reasons were “I thought that more research experience would make me a more competitive applicant” (66%) and “I wanted more research experience to solidify my decision to pursue a research-active career” (60%). Burnout, learning about MD-PhD programs too late, wanting more clinical experience, and needing to make money were each selected by about one-quarter of respondents. Needing the time to repeat the MCAT, complete prerequisites, and wanting to improve their academic record were selected least frequently. Of the 487 (14%) who selected “other,” the most common reasons were work and fellowship opportunities, not being sure about whether to apply, and needing to reapply. For the most part, there were few differences between men and women, between those who self-identified as UIM and those who did not, and between those whose gap lasted for 1 or 2 years and those whose gap was ≥3 years. However, individuals from groups considered to be UIM were more likely to list the need to make money or repeat the MCAT and were less likely to want to take personal time. Women were more likely than men to say that they were burnt out from school and needed time off. Those who took longer gaps were more likely to list wanting more research experience, more clinical experience, needing to make money, needing to retake the MCAT, improving grades, and prerequisite courses ( Table 1 ).

When asked to select the primary reason that they had chosen to take a gap, 52% of respondents listed a desire for more research experience, either to make them more competitive or to solidify their decision ( Table 2 and Figure 5A ). Notably, 75% of those who took a gap after college said that they did so to maximize their candidacy ( Figure 6A ). Only 10% thought it would not. Nearly everyone who had taken a gap said they would recommend taking one to others ( Figure 6B ). There was little or no difference in this response between men and women, and between those who self-identified as UIM and those who did not. Those who were most certain about the necessity of time between college and MD-PhD training were those with gaps that lasted 3 or more years; however, these differences were small ( Figure 6B ).

The students who had taken a gap were asked for ( A ) their primary reasons for doing a gap, ( B ) what they did during it, and ( C ) from where their advice came. Their choices and the percentage of respondents who selected that choice are shown on the pie charts. See also Tables 1 , ,3, 3 , and and6 6 for all of the reasons that were listed.

For the students who took a gap, responses to whether they felt a gap was necessary to maximize their candidacy and whether they would recommend taking a gap to future applicants. Number of respondents and the percentage of the total respondents for each response is shown. ( A ) The percentage who responded that a gap was necessary broken out by UIM status, gender, and gap duration. ( B ) The percentage of respondents who would recommend a gap by UIM status, gender, and gap duration.

What did you do during your time between college and medical school?

Trainees who had taken a gap were asked to select from a predefined list of possible activities during a gap ( Table 3 ). Multiple selections were allowed, but we also asked for what they considered to be the primary reason ( Table 4 and Figure 5B ). The two most frequently selected activities were “worked/volunteered in a research laboratory” (selected by 80% in Table 3 ) and “studied for and took the MCAT” (48%). 93% of those with a gap of 1 or 2 years and 97% of those taking a longer gap reported being in paid positions. We did not ask whether the pay that the received was sufficient for their living costs or whether they required additional support from other sources, including parents.

Taking the MCAT was especially prevalent among those who took gaps of ≥3 years, 81% of whom listed that as one of their activities. Members of groups considered to be UIM were more likely to list additional coursework and postbaccalaureate research programs. Those with longer gaps were more likely to list additional coursework, work in a field unrelated to medicine, and enrollment in a master’s program. “Other” activities included clinical experiences, but the number of people who selected “other” in Table 3 was small. Among the primary activities listed in Table 4 and Figure 5B , working in a research laboratory was by far the most frequent choice (59%), followed by enrollment in a postbaccalaureate research program (13% overall, 21% for individuals from underrepresented groups). Taken together, this indicates that 72% of those who took a gap were doing research as their primary activity.

We compared the responses to our survey with results from the AAMC MSQ survey, where the three most frequently selected activities were “worked in another career” (49% in 2020), “worked/volunteered in research” (48%), and “worked to improve finances” (40%) ( Table 5 ). The MSQ allowed multiple selections; however, the distribution of reasons to do a gap highlights a striking difference between MD-PhD program trainees and medical students in general.

How did you conclude that a gap was necessary?

By far the most frequent selection was “personal opinion,” a statement that presumably reflects multiple inputs as well as the applicant’s own musings. Other predefined choices in descending frequency were college pre-health advisors, online forums, current MD-PhD students, and advice from MD-PhD program directors ( Table 6 ). The ranked choices that respondents considered to be most influential are shown in Table 7 and Figure 5 C. Among the analyzed subgroups, members of underrepresented groups were more likely to acknowledge advice from program directors, as were men. Women were more likely to include college prehealth advisors and men were more likely to mention online forums. Current trainees who had gaps lasting ≥3 years were less likely to cite advice from college prehealth advisors and current MD-PhD students.

Approximately 71% (2511 trainees) of the 3544 trainees who completed the survey identified their undergraduate school. Assuming the survey respondents are representative of the overall MD-PhD trainee population, most current MD-PhD trainees came from a limited number of colleges. Although there were 385 colleges in all, 288 (75%) were represented in the survey by 5 or fewer respondents. Ranked by number of respondents, the top 30 colleges by respondent number (7.8% of 385) supplied 50% of the survey respondents. In this group of colleges, gap prevalence ranged from 15% to 89% ( Supplemental Figure 1 ). One caveat to the data on undergraduate institution is that 29% of respondents did not provide this information. Trainees who attended small colleges may have felt that identifying their college would make their responses identifiable to their program director and thus may have declined to provide the information.

Results from the survey of program directors.

After trainee survey collection was complete, a brief survey on related issues was sent to the directors of the 73 participating MD-PhD program, nearly all of whom completed it. One purpose of the survey was to ascertain whether trainees’ impressions that significant research experiences were necessary aligned with the preferences articulated by the program directors. The first question asked whether or not gaps are a factor that programs considered when making interview and admission decisions. 19 of 70 program directors (29%) responded “no” ( Figure 7A ). Notably, average gap prevalence among trainees who answered the survey was the same in programs that consider gaps a decision factor (68%) as in those that do not (69%).

( A ) Responses to the following question in the program director’s survey: “Are gaps a factor when deciding whom to interview and admit?” Blue bars show the percentage of directors who responded yes or no. The box-and-whisker plots to the right of each blue bar show the gap prevalence in the programs whose directors answered yes or no. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles; lines within the boxes indicate medians, and whiskers indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. Points above and below the whiskers are shown. Numbers indicate average gap prevalence for the programs ( n = 70). ( B ) Directors who responded that gaps were a factor were asked to indicate the impact on decision making from a dropdown list of responses. The possible choices are shown, with the percentage of respondents choosing a given response ( n = 51).

The 51 program directors who responded that they did take gaps into consideration for interview and admission decisions were then asked, “Which of the following descriptors best reflects how your admissions committee uses that information when evaluating a candidate for interview or acceptance. Assume that the time is spent doing research.” No one indicated a preference for candidates who had just graduated from college or advised candidates to not take a gap ( Figure 7B ). Conversely, none of the program directors indicated they require a research-focused gap, and only 5 (7%) said they strongly prefer it when making decisions. 46 said that they either somewhat prefer candidates who have taken a gap (29 program directors) or that the presence of a gap has no effect on their decisions (17 program directors). Counting the 21 programs that indicated that the existence of a gap is not a factor, this means that 53% (17 + 21 = 38) of the 72 program directors said that either they don’t consider gaps as a factor in their program’s interview and admission decisions or that gaps had no effect on those decisions.

Program directors were then asked if they view a gap spent doing research as being a favorable prognostic indicator for either commitment to complete an MD-PhD program or commitment to a career as a physician-scientist ( Figure 8A ). 71% answered probably or definitely “yes” to the first part of the question; 58% answered probably or definitely “yes” to the second. Notably, however, a sizable fraction of the program directors answered either “not enough to be useful” (24% and 35%) or “no” (6% and 7%) to these same questions, which suggests that, in the very least, there is not a consensus on whether taking a gap to demonstrate commitment will accomplish that goal for applicants.

Are gaps a prognostic factor, and what is the preferred activity during the gap? ( A ) Directors’ opinions regarding the extent to which an applicant choosing to take a gap indicates a commitment to complete the program (blue) and to pursue a career as a physician-scientist (red). Percentage of total responses is shown. ( B ) Directors’ choices from dropdown lists of preferred activity (red) and activity viewed most favorably (blue) ( n = 71).

Despite the lack of unanimity about the use of gap information in decision making, all but one of the program directors indicated that they care how candidates spend their time during a gap between college and medical school. Those 71 directors were then asked about which activities they view favorably and which they most prefer ( Figure 8B ). Working in a research setting or completing a prestigious individual fellowship were by far the most highly preferred activities.

Finally, program directors were asked how they view prior publications at the time of application. 43 (60%) answered “yes” to the question “Do you ask applicants whether they already have research papers submitted, in press, or published in your program’s application?” Of those 43, none considered first author publications to be essential. All 43 said that first author publications were either preferred or good if present but not negative if absent ( Figure 9 ). The corresponding replies for whether coauthor publications were considered essential, preferred, or good were 5%, 56% and 37%, respectively. Notably, a few of the programs that said they asked for publication-related information indicated that they were neutral (i.e., do not really care) about the answer.

The importance of an applicant having publications or abstracts. The directors’ survey asked whether secondary applications asked about publications. If they responded yes ( n = 43 of 71), they were asked to rate the importance of first author papers (blue), coauthored papers (orange), and abstracts (gray). The percentage of responses is shown.

Does taking a gap shorten the time to degree?

With most current students reporting that they took a gap before entering an MD-PhD program and that they typically used the time to work in a research setting, we were interested whether the additional research training and experience prior to matriculation facilitated faster completion of an MD-PhD program. Data on gap length and time to degree for matriculants entering on or after 2006 and graduating by 2021 was requested from all participating programs, of which 41 programs were able to provide information on 2391 graduates. Among the reported graduates, 1103 trainees did not take a gap and 1288 did. There was no difference in the average time to degree for those with gaps of 0, 1, or 2 years ( Figure 10 ). The average time to degree for those with a gap of 3 or more years was approximately 0.6 years (7 months) shorter than for trainees who took a shorter gap or who entered training without a gap ( P < 0.001 by 1-way ANOVA).

Forty-one programs provided deidentified data on 2391 program graduates who entered training after 2006 and graduated by 2021, 1103 with no gap, 581 with a 1-year gap, 401 with a 2-year gap, and 306 with a gap of 3 or more years. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles, and whiskers indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. Points above and below the whiskers are shown. The “+” in each box is the mean; this value is shown above each box. The time to degree was the same for those who took either no gap after college or a gap lasting 1 or 2 years. The average time to degree for those with a gap of 3 or more years was approximately 0.6 years (7 months) shorter ( P < 0.001 by 1-way ANOVA).

Recent events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, have highlighted the importance of biomedical research and the role that physician-scientists play in translating research from bench to bedside in a timely manner. Despite the importance of this career path, concerns have been raised for decades about the inadequate number of physician-scientists and the lack of necessary diversity in the physician-scientist workforce ( 3 , 6 , 16 , 17 ). While MD-PhD programs are not the only path to becoming a physician-scientist, they have attracted considerable attention because of their ability to integrate research and clinical training and because many graduates of these programs have proven to be successful in sustaining research careers ( 2 ). At a few medical schools, MD-PhD students represent 20% or more of each entering class, but nationwide only 3% of medical students are enrolled in an MD-PhD program. With the exception of the 2021 admissions cycle, the number of applications to MD-PhD programs has remained flat, while medical school applications have increased.

A number of factors have been cited to explain this lack of growth in the applicant pool. Notable factors include the time required to complete an MD-PhD program, the opportunity costs of deferred employment, the perception that physician-scientists start their families late and few manage to achieve acceptable work/life balance, limits on the number of positions available for physician-scientists, and lower salaries compared with either full-time clinical practice or tech sector jobs. The training path for physician-scientists often begins before or during college and extends through medical school, residencies, clinical fellowships, and postdocs, especially for those headed for careers in academia. As a result, training to become a physician-scientists can begin at 18 and last until 40 years of age. This path used to be considerably shorter. Reasons for why it has grown include increases in both the time to degree in MD-PhD programs and the time to a first job after postgraduate clinical training is complete ( 2 , 15 ).

Here, we have focused on a less appreciated contributor to the extension of training time — the increased prevalence of gaps taken between college and medical school. The data show that gap prevalence for MD-PhD students rose from 53% in 2013 to 75% in 2020, greatly outstripping the growth in gaps for MD students during the same time period. The dominant reason for this increase was applicants’ belief that gaps would increase their chances of being admitted, especially to the most competitive programs. Most trainees report using the gap period to build their research resumes. Notably, AAMC MSQ survey data show that research year(s) between college and medical school are common. However, the fraction of medical students doing gaps has now become substantially lower than the fraction of entering MD-PhD students ( Figure 1A ), and the reasons appear to be somewhat different. Many entering medical students cited a career shift as part of their decision to apply to medical school after gaining research experience. “Career switch” was not one of the prespecified choices in the current MD-PhD trainee survey, but respondents could write in additional reasons for deciding to do a gap, and 541 chose to do so. Only 16 (3%) described a career switch as a driving factor. That small group had an average gap duration nearly twice as long as those who didn’t describe a career switch (3.8 vs. 2.1 years).

Although large amounts of data were obtained from trainees, it is important to note as a potential limitation that only 71% of current trainees in participating programs chose to complete the survey. Because there is no way to know how the nonresponders would have answered the questions in the survey, we used AAMC data on applicants and matriculants to calculate gap prevalence for all successful and unsuccessful applicants to MD-PhD programs from 2013 to 2020. Those data confirm the rise in gap prevalence observed in our survey and show that unsuccessful applicants as a group were at least as likely to have taken a gap as those who were successful. This excludes the hypothesis that failure to gain admittance was due to a failure to take a gap. However, it does not exclude the possibility that at any given program there is a strong preference (conscious or unconscious) for applicants who have done gaps. The only way to determine the presence of a preference for a gap would be to evaluate program-specific data on those admitted versus those who were not admitted.

The opinions about gaps expressed by MD-PhD program directors proved to be more nuanced than the rush of applicants toward gaps would suggest. Only half (48%) indicated that they somewhat or strongly prefer applicants who have taken a gap, meaning that half of program directors do not. Although an even higher fraction (57%) felt that the decision to take a gap before applying probably or definitely forecasts commitment to a career as a physician-scientist, there are no data available to test this impression. We also found no evidence that time spent doing research in a gap shortens the time to degree, as might be expected if students arrive with greater skills and/or focus.

Why then is gap prevalence increasing? Part of the reason may be following the leader. Because most students in MD-PhD programs have done a research gap, it is not surprising that undergraduates will conclude that this is one way to increase their chances of admission. Compounding that impression is the advice that they get from college prehealth advisors, who often base their recommendations on past experience, and program directors, who emphasize the importance of meaningful, sustained research experiences. It seems that no matter the ambivalence that may be felt by individual program directors, collectively program directors are delivering the message that more research before applying to MD-PhD programs is better, full-time research is better than part time, and having one’s name on publications is desirable, although by no means essential. Advice about the value of gaps is also readily available via internet search engines. Some of it appears in forum discussions among those who have applied or are in the process of applying. Some of these opinions are from businesses selling their services to would-be physicians and physician-scientists.

A final factor that may be influencing admissions policies that favor gaps is the need to meet NIH expectations. NIGMS MSTP T32 grants currently support 50 MD-PhD programs, including, it should be noted, the 3 programs with which the authors of this study are affiliated. Over the past decade NIH expectations for data about applicants and matriculants has changed to require months of full-time research. Coincidentally or not, this change in reporting requirements coincided with the increase in gap prevalence.

What, then, is the harm if entrants into MD-PhD programs spend 1, 2, or 3 years doing full-time research before they dive into medical school? In addition to research and improved competitiveness, trainees in the present study listed a gap as a chance to take a break before an extended and intense training program, a wish to not spend their senior year applying, a desire to confirm their choice of a research-oriented career, and, in some cases, a need to reapply after falling short the first time. All of these reasons are perfectly understandable. Gaps are not without value in individual cases and, for some applicants, that value may be great enough to warrant taking the time. However, several adverse effects are also worth considering, including an extension of the already long time required before MD-PhD trainees can start their careers. Arguably, the greatest potential harm is when gaps result in a decision not to apply to MD-PhD programs, which may especially be the case for individuals from groups that are economically disadvantaged or UIM. Most MD-PhD programs provide tuition waivers and stipends for their students; however, the time invested in training comes with real costs. Training carries large opportunity costs for college graduates who could otherwise be headed toward careers that pay better sooner. For some without adequate family or personal resources, a gap and overall time in training can be a drain on financial resources that may not be fully compensated for by salaries earned many years later, and it may be limiting the diversity of applicants to MD-PhD programs.

At the end of the survey, trainees were invited to share any additional thoughts, and it is worth including a few of them here. Comments from the group that did not take a gap are especially informative. Although many reaffirmed their decision not to do a gap, others expressed regret, believing that they would have been more competitive, more mature, or more prepared if they had done so. Some expressed frustration that research gaps have become the new normal: “Gap years of research should not be a requirement for MD-PhD programs, that’s what the PhD is for.” One respondent reported, “I got feedback on my F30 [NIH fellowship application] that I could’ve had more publications if I’d taken a gap year, which seems like a ridiculous expectation given the length of the MD-PhD program already.” “I think the increasing number of students taking gap years is because of admission preference for the increased experience that comes with a gap year, which doesn’t necessarily reflect an individual’s capability to succeed in the program or future career.” These comments are anecdotal, but we agree with them.

Here is one comment that especially stood out: “The way selection is being done at the moment, you have essentially 90% of every matriculating class compos[ed] of students from research-intensive and/or ‘prestigious’ institutions. This exacerbates the inequities we already know of in undergraduate admissions and also causes the undesirable outcome where our MSTP trainees are not as diverse as can be.” The comment about 90% of matriculating MD-PhD students coming from research-intensive, prestigious institutions is not borne out by the data in this study; however, the comment that a perceived preference for applicants from research-intensive and/or prestigious institutes has an adverse effect on either racial or socioeconomic diversity is worrisome in an era when MD-PhD programs enroll relatively few students from groups considered to be UIM.

In conclusion, the present study shows that the majority of successful MD-PhD applicants are pausing after college to do more research and that they are doing so in part because of what they perceive to be a requirement for admission. That perception may not always be correct and may not be applicable to every program, but the survey data reported here make a compelling case. However, as tempting as it may be to believe, there are at present no data that would allow programs to conclude that gaps improve short- or long-term physician-scientist career outcomes. Unfortunately, the data set assembled in the National MD-PhD Outcomes study did not include college graduation year ( 2 ), which would have made it possible to calculate gap length. Absent such data, we suggest that policies and practices be revisited to assess their effect on applicants and societal needs for an active and diverse physician-scientist workforce. If a consensus emerges in the physician-scientist training community that undergraduates should hear that gaps are fine but not a requirement, then the answers to the survey question “How did you conclude that a gap was necessary?” suggest that applicants are getting the message from multiple sources — including college prehealth advisors, program directors, current MD-PhD students, and online forums — and integrating them amorphously into the most frequent answer “Personal opinion” ( Tables 6 and and7). 7 ). All of these sources will have to be addressed in as many settings as possible, but especially in outreach talks by program directors, on program websites, and in organized events.

In January 2021 an email was sent to a listserv of MD-PhD programs maintained by the National Association of MD-PhD Programs. Program directors were invited to participate in a study of students’ reasons for taking a gap between college and matriculation into MD-PhD programs. 73 MD-PhD programs, including 49 of the 50 NIGMS MSTP-supported programs, agreed to participate. A Qualtrics survey link was sent to each program to distribute to their students. Survey links were tagged with a unique “source” string so that the number of responses from each participating program could be tracked. 3545 completed surveys were received (of a total 5007 students enrolled in the 73 participating institutions). One respondent provided an undergraduate graduation year and MD-PhD matriculation year that indicated a 1-year gap. This individual was excluded from the analysis. The overall response rate to this survey was 70.8%. For multiple response set questions where respondents could “select all that apply,” a subsequent question asked them to identify the primary reason from among those they had chosen.

Deidentified information on applicants and matriculants to MD-PhD programs for each year from 2010 to 2020 was obtained from the AAMC under a data licensing agreement. The information that was provided and used in the present study included the year of college graduation, the outcome of each application (accepted MD-PhD, accepted MD, rejected), and the year of matriculation into an MD-PhD program (from which gap length was calculated). For data on the percentage of matriculating medical students who took a gap, we obtained the AAMC MSQ All Schools Summary Reports for the period from 2013 through 2020 either from the AAMC website ( https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/report/matriculating-student-questionnaire-msq ) or via a request to the AAMC Data Unit.

A follow-up survey of the directors of the participating MD-PhD programs was sent in April and May, 2021. 72 program directors provided data for an overall response rate of 97%. 41 program directors also answered a subsequent request by providing deidentified information on college graduation year, MD-PhD program matriculation year, and MD-PhD graduation year on 2391 program graduates who matriculated in 2006 or after. Gap duration was calculated as year of MD-PhD matriculation minus year of college graduation. Time to degree was calculated as year of MD-PhD graduation minus year of matriculation. We recognize that leaves of absence might alter calculated time to degree but we did not request information on leaves of absence.

The student survey asked all respondents demographic questions regarding race/ethnicity, gender, year of college graduation and MD-PhD program matriculation, college major, questions about the extent of undergraduate research experience, and number of publications at the time of MD-PhD program application. Race and ethnicity choices were consistent with NIH guidelines described in NOT-OD-15-089 ( 18 ); respondents could select all that applied. Respondents could optionally identify their undergraduate institution. Students who had 1 or more years between undergraduate graduation and MD-PhD program matriculation (gap years) were asked multiple-choice and open-ended questions focused on what students did during their gap years, why they chose to take a gap, and their research experiences prior to matriculation. All respondents were provided with an open-ended final question: “Please share any additional thoughts or comments regarding research requirements or gaps taken prior to matriculation in your MD-PhD program.” The survey is provided in Supplemental Methods. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and graphs. Responses were anonymized using the Qualtrics “anonymize response” feature and source identification was removed prior to analysis. No analysis was performed on a program-by-program basis. Responses from each program’s students will be returned to the program director in a fully deidentified format. The trainee survey was reviewed and granted exempted status by the University of Pennsylvania IRB.

For the purposes of this analysis, we defined UIM to include those individuals who self-identified with one or more of the following groups: Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Because of the limited numbers of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander trainees in MD-PhD programs and the increasing number of individuals who self-identify as members of more than one group, we chose in most of this analysis to report UIM as a single group, breaking out individual groups only when we felt that sufficient information was available. For some analyses, we defined program size based on the number of reported students. “MSTP funded” included those programs funded by NIGMS T32 grants during the July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021 fiscal year. Undergraduate majors were categorized as physical sciences (chemistry, computer science, engineering, mathematics, physics), biological sciences (biological and biomedical sciences, health sciences), and social sciences (humanities, social sciences, psychology).

Statistics.

Where indicated in the text and figures, group comparisons were made using a 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test for multiple comparisons after confirming that the data satisfy the assumption of a normal distribution. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Study approval.

The surveys were reviewed by the University of Pennsylvania IRB and deemed to meet eligibility criteria for IRB review exemption, authorized by 45 CFR 46.104, category 2.

Author contributions

LFB, RMF, and MHA collected data, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors express their appreciation to the MD-PhD programs, directors, and trainees who participated in this study; to Brian Sullivan, who as Secretary/Treasurer of the National Association of MD-PhD Programs helped to spread the word; and to Hope Charney at the University of Pennsylvania, who spent hours analyzing hundreds of free text comments in the trainee survey. Data on the MD-PhD applicant and matriculant pool and from the MSQ were provided by the AAMC. This work was supported in part by T32 GM07170 (to LFB), T32 GM007288 (to MHA), and T32 GM136651 (to RMF). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the AAMC.

Version Changes

Version 1. 03/22/2022.

Electronic publication

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Copyright: © 2022, Brass et al. This is an open access article published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Reference information: JCI Insight . 2022;7(6):e156168.https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.156168.

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

What Is The Age Limit for A PhD?

- By Dr Harry Hothi

- August 17, 2020

Introduction

I have seen and personally worked with PhD candidates of all ages, some older than me, some younger. In all my time within academia, I haven’t come across any university that places a limit on the age of an individual that wants to apply for and pursue a full time doctoral degree; indeed the practice of doing so would be rightly considered a form of discrimination at most academic institutions and even against the law in some countries.

However, a quick search on Google is enough to see that the question about age limits for doing a PhD is something that is asked quite often. This leads me to believe that there are many very capable potential doctoral candidates in the world that haven’t pursued their dreams of academic research almost entirely because they believe that they’re too old to do so.

There is No Age Limit for Doing a PhD

Simply put there is no age limit for someone considering doing a PhD. Indeed, on the opposite end of the scale, even the definition of a minimum’ age at which someone can start a PhD is not really well defined.

One of the youngest PhD graduates in recent times is thought to be Kim Ung-Yong who is a South Korean professor who purportedly earned a PhD in civil engineering at the age of 15 [1]. For the vast majority however, the practical considerations of progressing through the different stages of education (i.e. high school, undergraduate degree, a Master’s degree, etc.) mean that most won’t start their PhD projects until they’re at least in their early to mid 20’s; in the UK, for example, the average age for a PhD graduate is between 26 and 27 years old [2].

Meanwhile, the oldest person to be awarded a PhD degree in the United Kingdom is thought to be 95 year old Charles Betty, who gained his doctorate from the University of Northampton in 2018 after completing his 48,000 word thesis on why elderly expats living in Spain decide to return to the UK’ [3].

What does the data say?

According to data published by the National Science Foundation (NSF), a total of 54,904 people earned PhDs at universities in the United States of America in 2016; 46% of all new doctorates were women and 31% were international candidates [4].

Looking at the age distributions available for 51,621 of these new PhD graduates in 2016, 44% (n=22,863) were aged 30 or below, 43% (n=22,038) were aged between 31 and 40 and 13% (n=6,720) were over the age of 40 when they were awarded their doctoral degree. In this same year, over 50% of PhD students in subjects related to physical sciences, earth sciences, life sciences, mathematics, computer sciences and engineering were below the age of 31, whilst less than 10% of these STEM graduates were older than 41.

Conversely, 61% of PhDs in humanities and arts and 52% in other non-engineering and science disciplines gained their doctorates between 31 and 40 years of age. Interestingly, the analysis by the NSF found that 94% of doctoral candidates aged below 31 supported their research financially through research or teaching assistantships, grants or fellowships. Only 36% of PhDs aged over 41 at graduation reported receiving similar types of financial support; approximately 50% of this age group were found to have self-funded their studies.