Biography of Vladimir Putin: From KGB Agent to Russian President

- European History Figures & Events

- Wars & Battles

- The Holocaust

- European Revolutions

- Industry and Agriculture History in Europe

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Early Life, Education, and Career

- Prime Minister 1999

Acting President 1999 to 2000

First presidential term 2000 to 2004, second presidential term 2004 to 2008, second premiership 2008 to 2012.

- Third Presidential Term 2012 to 2018

Fourth Presidential Term 2018

Invasion of ukraine, interference in 2016 us presidential election, personal life, net worth, and religion, notable quotes, sources and references.

- B.S., Texas A&M University

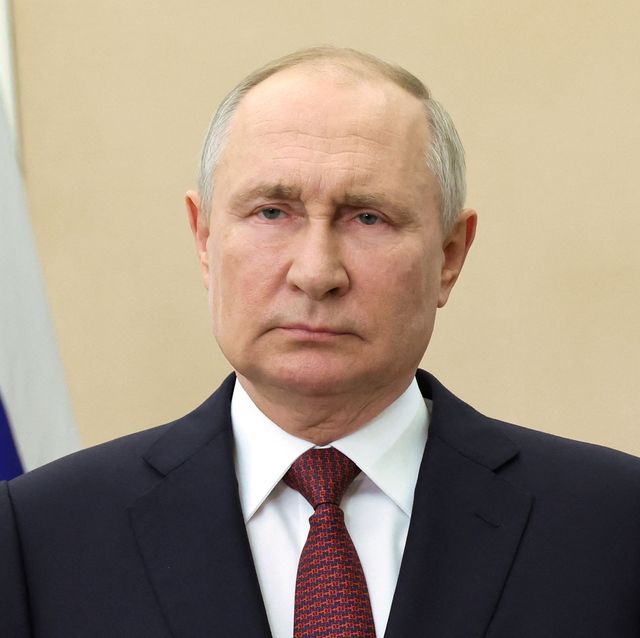

Vladimir Putin is a Russian politician and former KGB intelligence officer currently serving as President of Russia. Elected to his current and fourth presidential term in May 2018, Putin has led the Russian Federation as either its prime minister, acting president, or president since 1999. Long considered an equal of the President of the United States in holding one of the world’s most powerful public offices, Putin has aggressively exerted Russia’s influence and political policy around the world.

Fast Facts: Vladimir Puton

- Full Name: Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin

- Born: October 7, 1952, Leningrad, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia)

- Parents’ Names: Maria Ivanovna Shelomova and Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin

- Spouse: Lyudmila Putina (married in 1983, divorced in 2014)

- Children: Two daughters; Mariya Putina and Yekaterina Putina

- Education: Leningrad State University

- Known for: Russian Prime Minister and Acting President of Russia, 1999 to 2000; President of Russia 2000 to 2008 and 2012 to present; Russian Prime Minister 2008 to 2012.

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was born on October 7, 1952, in Leningrad, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia). His mother, Maria Ivanovna Shelomova was a factory worker and his father, Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin, had served in the Soviet Navy submarine fleet during World War II and worked as a foreman at an automobile factory during the 1950s. In his official state biography, Putin recalls, “I come from an ordinary family, and this is how I lived for a long time, nearly my whole life. I lived as an average, normal person and I have always maintained that connection.”

While attending elementary and high school, Putin took up judo in hopes of emulating the Soviet intelligence officers he saw in the movies. Today, he holds a black belt in judo and is a national master in the similar Russian martial art of sambo. He also studied German at Saint Petersburg High School, and speaks the language fluently today.

In 1975, Putin earned a law degree from Leningrad State University, where he was tutored and befriended by Anatoly Sobchak, who would later become a political leader during the Glasnost and Perestroika reform period. As a college student, Putin was required to join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union but resigned as a member in December 1991. He would later describe communism as “a blind alley, far away from the mainstream of civilization.”

After initially considering a career in law, Putin was recruited into the KGB (the Committee for State Security) in 1975. He served as a foreign counter-intelligence officer for 15 years, spending the last six in Dresden, East Germany. After leaving the KGB in 1991 with the rank of lieutenant colonel, he returned to Russia where he was in charge of the external affairs of Leningrad State University. It was here that Putin became an advisor to his former tutor Anatoly Sobchak, who had just become Saint Petersburg’s first freely-elected mayor. Gaining a reputation as an effective politician, Putin quickly rose to the position of first deputy mayor of Saint Petersburg in 1994.

Prime Minister 1999

After moving to Moscow in 1996, Putin joined the administrative staff of Russia’s first president Boris Yeltsin . Recognizing Putin as a rising star, Yeltsin appointed him director of the Federal Security Service (FSB)—the post-communism version of the KGB—and secretary of the influential Security Council. On August 9, 1999, Yeltsin appointed him as acting prime minister. On August 16, the Russian Federation’s legislature, the State Duma , voted to confirm Putin’s appointment as prime minister. The day Yeltsin first appointed him, Putin announced his intention to seek the presidency in the 2000 national election.

While he was largely unknown at the time, Putin’s public popularity soared when, as prime minister, he orchestrated a military operation that succeeded resolving the Second Chechen War , an armed conflict in the Russian-held territory of Chechnya between Russian troops and secessionist rebels of the unrecognized Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, fought between August 1999 and April 2009.

When Boris Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned on December 31, 1999, under suspicion of bribery and corruption, the Constitution of Russia made Putin acting President of the Russian Federation. Later the same day, he issued a presidential decree protecting Yeltsin and his relatives from prosecution for any crimes they might have committed.

While the next regular Russian presidential election was scheduled for June 2000, Yeltsin’s resignation made it necessary to hold the election within three months, on March 26, 2000.

At first far behind his opponents, Putin’s law-and-order platform and decisive handling of the Second Chechen War as acting president soon pushed his popularity beyond that of his rivals.

On March 26, 2000, Putin was elected to his first of three terms as President of the Russian Federation winning 53 percent of the vote.

Shortly after his inauguration on May 7, 2000, Putin faced the first challenge to his popularity over claims that he had mishandled his response to the Kursk submarine disaster . He was widely criticized for his refusal to return from vacation and visit the scene for over two weeks. When asked on the Larry King Live television show what had happened to the Kursk, Putin’s two-word reply, “It sank,” was widely criticized for its perceived cynicism in the face of tragedy.

October 23, 2002, as many as 50 armed Chechens, claiming allegiance to the Chechnya Islamist separatist movement, took 850 people hostage in Moscow’s Dubrovka Theater. An estimated 170 people died in the controversial special-forces gas attack that ended the crisis. While the press suggested that Putin’s heavy-handed response to the attack would damage his popularity, polls showed over 85 percent of Russians approved of his actions.

Less than a week after the Dubrovka Theater attack, Putting clamped down even harder on the Chechen separatists, canceling previously announced plans to withdraw 80,000 Russian troops from Chechnya and promising to take “measures adequate to the threat” in response to future terrorist attacks. In November, Putin directed Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov to order sweeping attacks against Chechen separatists throughout the breakaway republic.

Putin’s harsh military policies succeeded in at least stabilizing the situation in Chechnya. In 2003, the Chechen people voted to adopt a new constitution confirming that the Republic of Chechnya would remain a part of Russia while retaining its political autonomy. Though Putin’s actions greatly diminished the Chechen rebel movement, they failed to end the Second Chechen War, and sporadic rebel attacks continued in the northern Caucasus region.

During the majority of his first term, Putin concentrated on improving the failing Russian economy, in part by negotiating a “grand bargain” with the Russian business oligarchs who had controlled the nation’s wealth since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Under the bargain, the oligarchs would retain most of their power, in return for supporting—and cooperating with—Putin’s government.

According to financial observers at the time, Putin made it clear to the oligarchs that they would prosper if they played by the Kremlin rules. Indeed, Radio Free Europe reported in 2005 that the number of Russian business tycoons had greatly increased during Putin’s time in power, often aided by their personal relationships with him.

Whether Putin’s “grand bargain” with the oligarchs actually “improved” the Russian economy or not remains uncertain. British journalist and expert on international affairs Jonathan Steele has observed that by the end of Putin’s second term in 2008, the economy had stabilized and the nation’s overall standard of living had improved to the point that the Russian people could “notice a difference.”

On March 14, 2004, Putin was easily re-elected to the presidency, this time winning 71 percent of the vote.

During his second term as president, Putin focused on undoing the social and economic damage suffered by the Russian people during the collapse and dissolution of the Soviet Union, an event he called “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the Twentieth Century.” In 2005, he launched the National Priority Projects designed to improve health care, education, housing, and agriculture in Russia.

On October 7, 2006—Putin’s birthday— Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist and human rights activist, who as a frequent critic of Putin and had exposed corruption in the Russian Army and cases of its improper conduct in the Chechnya conflict, was shot to death as she entered the lobby of her apartment building. While Politkovskaya’s killer was never identified, her death brought criticism that Putin’s promise to protect the newly-independent Russian media had been no more than political rhetoric. Putin commented that Politkovskaya’s death had caused him more problems than anything she had ever written about him.

In 2007, Other Russia, a group opposed to Putin led by former world chess champion Garry Kasparov, organized a series of “Dissenters’ Marches” to protest Putin’s policies and practices. Marches in several cities resulted in the arrests of some 150 protestors who tried to penetrate police lines.

In the December 2007 elections, the equivalent of the U.S. mid-term congressional election, Putin’s United Russia party easily retained control of the State Duma, indicating the Russian people’s continued support for him and his policies.

The democratic legitimacy of the election was questioned, however. While some 400 foreign election monitors stationed at polling places stated that the election process itself had not been rigged, the Russian media’s coverage had clearly favored candidates of United Russia. Both the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe concluded that the elections were unfair and called on the Kremlin to investigate alleged violations. A Kremlin-appointed election commission concluded that not only had the election been fair, but it had also proven the “stability” of the Russian political system.

With Putin barred by the Russian Constitution from seeking a third consecutive presidential term, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was elected president. However, on May 8, 2008, the day after Medvedev’s inauguration, Putin was appointed Prime Minister of Russia. Under the Russian system of government, the president and the prime minister share responsibilities as the head of state and head of the government, respectively. Thus, as prime minister, Putin retained his dominance over the country’s political system.

In September 2001, Medvedev proposed to the United Russia Congress in Moscow, that Putin should run for the presidency again in 2012, an offer Putin happily accepted.

Third Presidential Term 2012 to 2018

On March 4, 2012, Putin won the presidency for a third time with 64 percent of the vote. Amid public protests and accusations that he had rigged the election, he was inaugurated on May 7, 2012, immediately appointing former President Medvedev as prime minister. After successfully quelling protests against the election process, often by having marchers jailed, Putin proceeded to make sweeping—if controversial—changes to Russia’s domestic and foreign policy.

In December 2012, Putin signed a law prohibiting the adoption of Russian children by U.S. citizens. Intended to ease the adoption of Russian orphans by Russian citizens, the law stirred international criticism, especially in the United States, where as many as 50 Russian children in the final stages of adoption were left in legal limbo.

The following year, Putin again strained his relationship with the U.S. by granting asylum to Edward Snowden, who remains wanted in the United States for leaking classified information he gathered as a contractor for the National Security Agency on the WikiLeaks website. In response, U.S. President Barack Obama canceled a long-planned August 2013 meeting with Putin.

Also in 2013, Putin issued a set of highly controversial anti-gay laws outlawing gay couples from adopting children in Russia and banning the dissemination of material promoting or describing “nontraditional” sexual relationships to minors. The laws brought worldwide protests from both the LGBT and straight communities.

In December 2017, Putin announced he would seek a six-year—rather than four-year—term as president in July, running this time as an independent candidate, cutting his old ties with the United Russia party.

After a bomb exploded in a crowded Saint Petersburg food market on December 27, injuring dozens of people, Putin revived his popular “tough on terror” tone just before the election. He stated that he had ordered Federal Security Service officers to “take no prisoners” when dealing with terrorists.

In his annual address to the Duma in March 2018, just days before the election, Putin claimed that the Russian military had perfected nuclear missiles with “unlimited range” that would render NATO anti-missile systems “completely worthless.” While U.S. officials expressed doubts about their reality, Putin’s claims and saber-rattling tone ratcheted up tensions with the West but nurtured renewed feelings of national pride among Russian voters.

On March 18, 2018, Putin was easily elected to a fourth term as President of Russia, winning more than 76 percent of the vote in an election that saw 67 percent of all eligible voters cast ballots. Despite the opposition to his leadership that had surfaced during his third term, his closest competitor in the election garnered only 13 percent of the vote. Shortly after officially taking office on May 7, Putin announced that in compliance with the Russian Constitution, he would not seek reelection in 2024.

On July 16, 2018, Putin met with U.S. President Donald Trump in Helsinki, Finland, in what was called the first of a series of meetings between the two world leaders. While no official details of their private 90-minute meeting were published, Putin and Trump would later reveal in press conferences that they had discussed the Syrian civil war and its threat to the safety of Israel, the Russian annexation of Crimea , and the extension of the START nuclear weapons reduction treaty.

On February 23, 2022, Putin launched an unprovoked military invasion of Ukraine, which had officially declared itself an independent country on August 24, 1991. Putin justified the act with the false narrative that Ukraine was not a real country. That it “belongs” to Russia as part of a “Great Russia” and the “Russian World,” and that there is, according to Putin, no Ukrainian people, no Ukrainian language, and no separate Ukrainian history.

After Russia launched its 2022 invasion, the United States, the European Union (EU), and other NATO member nations condemned Putin, substantially increased military, humanitarian, and economic assistance to Ukraine, and imposed a series of increasingly crippling financial and economic sanctions on Russia. In addition, hundreds of U.S. and other companies withdrew, suspended, or curtailed operations in or with Russia.

On February 8, 1994, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization ( NATO ) accepted Ukraine into its Partnership for Peace, a collaborative arrangement open to all non-NATO European countries and post-Soviet states. Russia became a NATO member in June 1994 and conducted various cooperative activities with NATO, including joint military exercises, until 2014, when NATO formally suspended ties with the country. As the Cold War ended, Russia opposed the eastern expansion of NATO. However, thirteen former Soviet partnership members eventually joined the alliance.

Ukraine is not a NATO member. However, Ukraine is a NATO partner country, which means that it cooperates closely with NATO but it is not covered by the security guarantee in the Alliance’s founding treaty.

The invasion seemed to tarnish Putin’s image among the Russian people, as young citizens, along with middle-aged and even retired people, took to the streets to speak out against a military conflict ordered by their President—a decision in which, they claimed, they had no say.

Putin responded by shutting down public dissent against the attack on Ukraine. By the end of July 2022, a total of over 7,624 protesters had been detained or arrested to 7,624 since the invasion began, according to an independent organization that tracks human rights violations in Russia.

During Putin’s third presidential term, allegations arose in the United States that the Russian government had interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

A combined U.S. intelligence community report released in January 2017 found “high confidence” that Putin himself had ordered a media-based “influence campaign” intended to harm the American public’s perception of Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton , thus improving the electoral chances of eventual election winner, Republican Donald Trump . In addition, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is investigating whether officials of the Trump campaign organization colluded with high ranking Russian officials to influence the election.

While both Putin and Trump have repeatedly denied the allegations, the social media website Facebook admitted in October 2017 that political ads purchased by Russian organizations had been seen by at least 126 million Americans during the weeks leading up to the election.

Vladimir Putin married Lyudmila Shkrebneva on July 28, 1983. From 1985 to 1990, the couple lived in East Germany where they gave birth to their two daughters, Mariya Putina and Yekaterina Putina. On June 6, 2013, Putin announced the end of the marriage. Their divorce became official on April 1, 2014, according to the Kremlin. An avid outdoorsman, Putin publicly promotes sports, including skiing, cycling, fishing, and horseback riding as a healthy way of life for the Russian people.

While some say he may be the world’s wealthiest man, Vladimir Putin’s exact net worth is not known. According to the Kremlin, the President of the Russian Federation is paid the U.S. equivalent of about $112,000 per year and is provided with an 800-square foot apartment as an official residence. However, independent Russian and U.S. financial experts have estimated Putin’s combined net worth at from $70 billion to as much as $200 billion. While his spokespersons have repeatedly denied allegations that Putin controls a hidden fortune, critics in Russia and elsewhere remain convinced that he has skillfully used the influence of his nearly 20-years in power to acquire massive wealth.

A member of the Russian Orthodox Church, Putin recalls the time his mother gave him his baptismal cross, telling him to get it blessed by a Bishop and wear it for his safety. “I did as she said and then put the cross around my neck. I have never taken it off since,” he once recalled.

As one of the most powerful, influential, and often-controversial world leaders of the past two decades, Vladimir Putin has uttered many memorable phrases in public. A few of these include:

- “There is no such thing as a former KGB man.”

- “People are always teaching us democracy but the people who teach us democracy don't want to learn it themselves.”

- “Russia doesn’t negotiate with terrorists. It destroys them.”

- “In any case, I’d rather not deal with such questions, because anyway it’s like shearing a pig—lots of screams but little wool.”

- “I am not a woman, so I don’t have bad days.”

- “ Vladimir Putin Biography .” Vladimir Putin official state biography

- “ Vladimir Putin – President of Russia .” European-Leaders.com (March 2017)

- “ First Person: An Astonishingly Frank Self-Portrait by Russia's President Vladimir Putin .” The New York Times (2000)

- “ Putin’s Obscure Path From KGB to Kremlin .” Los Angeles Times (2000)

- “ Vladimir Putin quits as head of Russia's ruling party .” The Daily Telegraph (2002)

- “ Russian lessons .” Financial Times. September 20, 2008

- “ Russia: Bribery Thriving Under Putin, According To New Report .” Radio Free Europe (2005)

- Steele, Jonathan. “ Putin’s legacy is a Russia that doesn't have to curry favour with the west .” The Guardian, September 18, 2007

- Bohlen, Celestine (2000). “ YELTSIN RESIGNS: THE OVERVIEW; Yeltsin Resigns, Naming Putin as Acting President To Run in March Election .” The New York Times.

- Sakwa, Richard (2007). “Putin : Russia's Choice (2nd ed.).” Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9780415407656.

- Judah, Ben (2015). “Fragile Empire: How Russia Fell in and Out of Love with Vladimir Putin.” Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300205220.

- The History and Geography of Crimea

- What Was the USSR and Which Countries Were in It?

- Saparmurat Niyazov

- Top Books: Modern Russia - The Revolution and After

- The Relationship of the United States With Russia

- Mongolia Facts, Religion, Language, and History

- Population Decline in Russia

- The Russian Revolution of 1917

- Kazahkstan: Facts and History

- Ten Things to Know About Dwight Eisenhower

- John Quincy Adams: Significant Facts and Brief Biography

- What Is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)?

- Boris Yeltsin: First President of the Russian Federation

- World War I and The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

- The Cold War in Europe

- Political Parties in Russia

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin served as president of Russia from 2000 to 2008 and was re-elected to the presidency in 2012, where he has stayed ever since. He previously served as Russia's prime minister.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

1952-present

Latest News: Vladimir Putin Announces 2024 Russian Presidential Run

According to the Associated Press , the 71-year-old Putin, who was first elected president in March 2000, has twice amended the Russian constitution so that he could theoretically remain in power until 2036. He is already the longest-serving Kremlin leader since Joseph Stalin .

Quick Facts

Early life and political career, president of russia: first and second terms, third term as president, chemical weapons in syria, 2014 winter olympics, invasion into crimea, syrian airstrikes, u.s. election hacks, fourth presidential term, invasion of ukraine, seeking fifth presidential term, personal life, who is vladimir putin.

In 1999, Russian president Boris Yeltsin dismissed his prime minister and promoted former KGB officer Vladimir Putin in his place. In December 1999, Yeltsin resigned, appointing Putin president, and he was re-elected in 2004. In April 2005, he made a historic visit to Israel—the first visit there by any Kremlin leader. Putin could not run for the presidency again in 2008, but was appointed prime minister by his successor, Dmitry Medvedev. Putin was re-elected to the presidency in March 2012 and later won a fourth term. In 2014, he was reportedly nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

FULL NAME: Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin BORN: October 7, 1952 BIRTHPLACE: Leningrad (St. Petersburg), Russia SPOUSE: Lyudmila Shkrebneva (1983-2014) CHILDREN: Maria, Yekaterina ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Libra

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was born in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Russia, on October 7, 1952. He grew up with his family in a communal apartment, attending the local grammar and high schools, where he developed an interest in sports. After graduating from Leningrad State University with a law degree in 1975, Putin began his career in the KGB as an intelligence officer. Stationed mainly in East Germany, he held that position until 1990, retiring with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Upon returning to Russia, Putin held an administrative position at the University of Leningrad, and after the fall of communism in 1991, he became an adviser to liberal politician Anatoly Sobchak. When Sobchak was elected mayor of Leningrad later that year, Putin became his head of external relations, and by 1994, Putin had become Sobchak’s first deputy mayor.

After Sobchak’s defeat in 1996, Putin resigned his post and moved to Moscow. There, in 1998, Putin was appointed deputy head of management under Boris Yeltsin’s presidential administration. In that position, he was in charge of the Kremlin's relations with the regional governments.

Shortly afterward, Putin was appointed head of the Federal Security Service, an arm of the former KGB, as well as head of Yeltsin’s Security Council. In August 1999, Yeltsin dismissed his prime minister, Sergey Stapashin, along with his cabinet, and promoted Putin in his place.

In December 1999, Boris Yeltsin resigned as president of Russia and appointed Putin acting president until official elections were held, and in March 2000, Putin was elected to his first term with 53 percent of the vote. Promising both political and economic reforms, Putin set about restructuring the government and launching criminal investigations into the business dealings of high-profile Russian citizens. He also continued Russia's military campaign in Chechnya.

In September 2001, in response to the terrorist attacks on the United States, Putin announced Russia’s support for the U.S. in its anti-terror campaign. However, when the U.S.’s “war on terror” shifted focus to the ousting of Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein , Putin joined German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and French President Jacques Chirac in opposition of the plan.

In 2004, Putin was re-elected to the presidency, and in April of the following year made a historic visit to Israel for talks with Prime Minister Ariel Sharon—marking the first visit to Israel by any Kremlin leader.

Due to constitutional term limits, Putin was prevented from running for the presidency in 2008. (That same year, presidential terms in Russia were extended from four to six years.) However, when his protégé Dmitry Medvedev succeeded him as president in March 2008, he immediately appointed Putin as Russia’s prime minister, allowing Putin to maintain a primary position of influence for the next four years.

On March 4, 2012, Vladimir Putin was re-elected to his third term as president. After widespread protests and allegations of electoral fraud, he was inaugurated on May 7, 2012, and shortly after taking office appointed Medvedev as prime minister. Once more at the helm, Putin has continued to make controversial changes to Russia’s domestic affairs and foreign policy.

In December 2012, Putin signed into a law a ban on the U.S. adoption of Russian children. According to Putin, the legislation—which took effect on January 1, 2013—aimed to make it easier for Russians to adopt native orphans. However, the adoption ban spurred international controversy, reportedly leaving nearly 50 Russian children—who were in the final phases of adoption with U.S. citizens at the time that Putin signed the law—in legal limbo.

Putin further strained relations with the United States the following year when he granted asylum to Edward Snowden , who is wanted by the United States for leaking classified information from the National Security Agency. In response to Putin's actions, U.S. President Barack Obama canceled a planned meeting with Putin that August.

Around this time, Putin also upset many people with his new anti-gay laws. He made it illegal for gay couples to adopt in Russia and placed a ban on propagandizing “nontraditional” sexual relationships to minors. The legislation led to widespread international protest.

In September 2013, tensions rose between the United States and Syria over Syria’s possession of chemical weapons, with the U.S. threatening military action if the weapons were not relinquished. The immediate crisis was averted, however, when the Russian and U.S. governments brokered a deal whereby those weapons would be destroyed.

On September 11, 2013, The New York Times published an op-ed piece by Putin titled “A Plea for Caution From Russia.” In the article, Putin spoke directly to the U.S.’s position in taking action against Syria, stating that such a unilateral move could result in the escalation of violence and unrest in the Middle East.

Putin further asserted that the U.S. claim that Bashar al-Assad used the chemical weapons on civilians might be misplaced, with the more likely explanation being the unauthorized use of the weapons by Syrian rebels. He closed the piece by welcoming the continuation of an open dialogue between the involved nations to avoid further conflict in the region.

In 2014, Russia hosted the Winter Olympics, which were held in Sochi beginning on February 6. According to NBS Sports, Russia spent roughly $50 billion in preparation for the international event.

However, in response to what many perceived as Russia’s recently passed anti-gay legislation, the threat of international boycotts arose. In October 2013, Putin tried to allay some of these concerns, saying in an interview broadcast on Russian television that, “We will do everything to make sure that athletes, fans and guests feel comfortable at the Olympic Games regardless of their ethnicity, race or sexual orientation.”

In terms of security for the event, Putin implemented new measures aimed at cracking down on Muslim extremists, and in November 2013 reports surfaced that saliva samples had been collected from some Muslim women in the North Caucasus region. The samples were ostensibly to be used to gather DNA profiles, in an effort to combat female suicide bombers known as “black widows.”

Shortly after the conclusion of the 2014 Winter Olympics, amidst widespread political unrest in Ukraine, which resulted in the ousting of President Viktor Yanukovych, Putin sent Russian troops into Crimea, a peninsula in the country’s northeast coast of the Black Sea. The peninsula had been part of Russia until Nikita Khrushchev, former Premier of the Soviet Union, gave it to Ukraine in 1954.

Ukraine’s ambassador to the United Nations, Yuriy Sergeyev, claimed that approximately 16,000 troops invaded the territory, and Russia’s actions caught the attention of several European countries and the United States, who refused to accept the legitimacy of a referendum in which the majority of the Crimean population voted to secede from Ukraine and reunite with Russia.

Putin defended his actions, insisting that the troops sent into Ukraine were only meant to enhance Russia’s military defenses within the country—referring to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, which has its headquarters in Crimea. He also vehemently denied accusations by other nations, particularly the United States, that Russia intended to engage Ukraine in war.

He went on to claim that although he was granted permission from Russia's upper house of Parliament to use force in Ukraine, he found it unnecessary. Putin also wrote off any speculation that there would be a further incursion into Ukrainian territory, saying, “Such a measure would certainly be the very last resort.”

The following day, it was announced that Putin had been nominated for the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize.

In September 2015, Russia surprised the world by announcing it would begin strategic airstrikes in Syria. Despite government officials’ assertions that the military actions were intended to target the extremist Islamic State, which made significant advances in the region due to the power vacuum created by Syria's ongoing civil war, Russia's true motives were called into question, with many international analysts and government officials claiming that the airstrikes were in fact aimed at the rebel forces attempting to overthrow President Bashar al-Assad's historically repressive regime.

In late October 2017, Putin was personally involved in another alarming form of aerial warfare when he oversaw a late-night military drill that resulted in the launch of four ballistic missiles across the country. The drill came during a period of escalating tensions in the region, with Russian neighbor North Korea also drawing attention for its missile tests and threats to engage the U.S. in destructive conflict.

In December 2017, Putin announced he was ordering Russian forces to begin withdrawing from Syria, saying the country’s two-year campaign to destroy ISIS was complete, though he left open the possibility of returning if terrorist violence resumed in the area. Despite the declaration, Pentagon spokesman Robert Manning was hesitant to endorse that view of events, saying, “Russian comments about removal of their forces do not often correspond with actual troop reductions.”

Months prior to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, multiple U.S. intelligence agencies unilaterally agreed that Russian intelligence was behind the email hacks of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and John Podesta, who had, at the time, been chairman of Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s campaign.

In December 2016 unnamed senior CIA officials further concluded “with a high level of confidence” that Putin was personally involved in intervening in the U.S. presidential election, according to a report by USA Today . The officials further went on to assert that the hacked DNC and Podesta emails that were given to WikiLeaks just before U.S. Election Day were designed to undermine Clinton’s campaign in favor of her Republican opponent, Donald Trump . Soon after, the FBI and National Intelligence Agency publicly supported the CIA’s assessments.

Putin denied any such attempts to disrupt the U.S. election, and despite the assessments of his intelligence agencies, President Trump generally seemed to favor the word of his Russian counterpart. Underscoring their attempts to thaw public relations, the Kremlin in late 2017 revealed that a terror attack had been thwarted in St. Petersburg, thanks to intelligence provided by the CIA.

Around that time, Putin reported at his annual end-of-year press conference that he would seek a new six-year term as president in early 2018 as an independent candidate, signaling he was ending his longtime association with the United Russia party.

Shortly before the first formal summit between Presidents Putin and Trump in July 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice announced the indictments of 12 Russian operatives on charges relating to interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Regardless, Trump suggested he was satisfied with his counterpart’s “strong and powerful" denial in a joint news conference and praised Putin’s offer to submit the 12 indicted agents to questioning with American witnesses present.

In a subsequent interview with Fox News anchor Chris Wallace, Putin seemingly defended the hacking of the DNC server by suggesting that no false information was planted in the process. He also rejected the idea that he had compromising information about Trump, saying that the businessman “was of no interest for us” before announcing his presidential campaign, and notably refused to touch a copy of the indictments offered to him by Wallace.

In March 2018, toward the end of his third term, Putin boasted of new weaponry that would render NATO defenses “completely worthless,” including a low-flying nuclear-capable cruise missile with “unlimited” range and another one capable of traveling at hypersonic speed. His demonstration included video animation of attacks on the United States.

Not long afterward, a two-hour documentary, titled Putin , was posted to several social media pages and a pro-Kremlin YouTube account. Designed to showcase the president in a strong yet humane light, the doc featured Putin sharing the story of how he ordered a hijacked plane shot down to head off a bomb scare at the 2014 Sochi Olympics, as well as recollections of his grandfather's days as a cook for Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin .

On March 18, 2018, the fourth anniversary of the country’s seizure of Crimea, Russian citizens overwhelmingly elected Putin to a fourth presidential term, with 67 percent of the electorate turning out to award him more than 76 percent of the vote. The divided opposition stood little chance against the popular leader, his closest competitor notching around 13 percent of the vote.

Little was expected to change regarding Putin’s strategies for rebuilding the country as a global power, though the start of his final term set off questions about his successor, and whether he would affect constitutional change in an attempt to remain in office indefinitely.

On July 16, 2018, Putin met with President Trump in Helsinki, Finland, for the first formal talks between the two leaders. According to Russia, topics of the meeting included the ongoing war in Syria and “the removal of the concerns” about accusations of Russian attempts to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

The following April, Putin met with North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un for the first time. The two leaders discussed the issue of the North Korean laborers in Russia, while Putin also offered support of his counterpart’s denuclearization negotiations with the U.S., saying Kim would need “security guarantees” in exchange for abandoning his nuclear program.

The topic of whether Putin aimed to extend his hold on power resurfaced following his state-of-the-nation speech in January 2020, which included proposals for constitutional amendments that included transferring the power to select the prime minister and cabinet from the president to the Parliament. The entire cabinet, including Medvedev, promptly resigned, leading to the selection of Mikhail V. Mishustin as the new prime minister.

Despite Putin’s earlier remarks of further incursion into Ukraine being a last resort, in the spring of 2021, Russian military forces began forming near the borders of the neighboring country for what the Kremlin claimed were training exercises. According to Reuters , more than 100,000 troops had deployed by November.

On December 17, Russia released a list of security demands that included NATO pulling back forces and weaponry from its eastern flank and ceasing further expansion, including the possible addition of Ukraine into the alliance. If the demands were not met, a “military response” was promised.

Then on February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine with missile and rocket strikes on Ukrainian cities and military installations. In a televised address, Putin—claiming that Russian speakers in Ukraine faced genocide—referred to the invasion as a “special military operation,” designed to “achieve the demilitarization and denazification" of the country. In the early hours, Russian forces took Chernobyl, site of the infamous 1986 nuclear disaster, but were held back from the capital city of Kyiv.

As the conflict dragged on with Western allies supporting Ukraine, Putin announced the “special mobilization” of more than 100,000 reserve troops in September 2022.

Ukrainian troops launched a counteroffensive in June 2023 and, as of December, the conflict is still ongoing. The U.S. estimated that August that around 500,000 Russian and Ukrainian soldiers had been wounded or killed.

In December 2023, Putin announced that he would seek a fifth term as president of Russia in the country's upcoming elections in March 2024. With a victory, he would be able to remain in power until at least 2030 and potentially run for another subsequent six-year term.

Putin is not expected to face any serious challengers and remains popular domestically. According to CNBC , a survey by Russian news agency Tass found that more than 78 percent of Russians trust Putin, and more than 75 percent approve of his activities.

In 1980, Putin met his future wife, Lyudmila, who was working as a flight attendant at the time. The couple married in 1983 and had two daughters: Maria, born in 1985, and Yekaterina, born in 1986. In early June 2013, after nearly 30 years of marriage, Russia’s first couple announced that they were getting a divorce, providing little explanation for the decision, but assuring that they came to it mutually and amicably.

“There are people who just cannot put up with it,” Putin stated. “Lyudmila Alexandrovna has stood watch for eight, almost nine years.” Providing more context to the decision, Lyudmila added, “Our marriage is over because we hardly ever see each other. Vladimir Vladimirovich is immersed in his work, our children have grown and are living their own lives.”

An Orthodox Christian, Putin is said to attend church services on important dates and holidays on a regular basis and has had a long history of encouraging the construction and restoration of thousands of churches in the region. He generally aims to unify all faiths under the government’s authority and legally requires religious organizations to register with local officials for approval.

- The path towards a free society has not been simple. There are tragic and glorious pages in our history.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti joined the Biography.com staff in 2023, and before that had worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University, an avid sports fan, a frequent moviegoer, and trivia buff.

Famous Political Figures

Deb Haaland

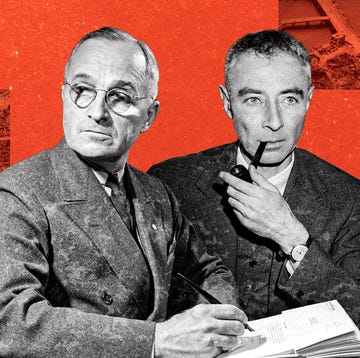

Why Lewis Strauss Didn’t Like Oppenheimer

Madeleine Albright

These Are the Major 2024 Presidential Candidates

Hillary Clinton

Indira Gandhi

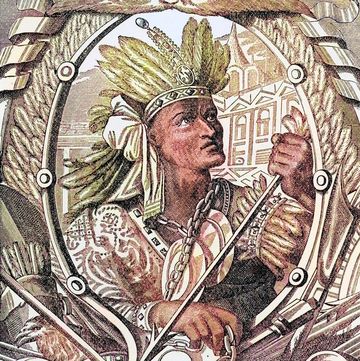

Toussaint L'Ouverture

Kevin McCarthy

Henry Kissinger

Oppenheimer and Truman Met Once. It Went Badly.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Putin: His Life and Times review – the collapse that shaped the man who would be tsar

Philip Short’s meticulous new biography forces us to look at Vladimir Putin’s most appalling acts from a Russian perspective

I n his speech on the night of the invasion of Ukraine on 24 February, which Philip Short describes as “pulsating with anger and resentment” at 30 years of Russian humiliation, Putin seethed: “They deceived us… they duped us like a con artist… the whole so-called western bloc, formed by the United States in its own image is… an empire of lies.” For those who dismiss the speech and the invasion that followed as the words and actions of a man gone mad, dying or out of contact with reality due to Covid isolation, this new biography should be compulsory reading.

As Short observes, however authoritarian and corrupt modern Russia may be, “national leaders invariably reflect the society from which they come, no matter how unpalatable that thought may be to the citizens”. While his people may have been as surprised as the rest of the world at the timing, the invasion hardly came out of the blue and many Russians, not all blinded by propaganda, support it. For as the foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, commented a couple of weeks later: “This is not actually, or at least primarily… about Ukraine. It reflects the battle over what the world order will look like. Will it be a world in which the west will lead everyone with impunity and without question?”

Refreshingly, Short, in this meticulous biography of a man portrayed elsewhere as a 21st-century monster, refuses to moralise, opting instead to lay out how Putin’s recent actions can be seen as the consequence of the 30 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The former BBC correspondent is at his best when pushing us to see the world from a Russian perspective. The importance of this is neatly illustrated in the publisher’s own claims for the book: “What forces and experiences shaped him [Putin]? What led him to challenge the American-led world order that has kept the peace since the end of the cold war?” Short relentlessly traces the journey Putin has taken in rejecting that “peace”, the Pax Americana, the unipolar world in which, according to Russia expert Strobe Talbott, then US deputy secretary of state, “the US was acting as though it had the right to impose its view on the world”. From Moscow, Putin watched the US openly intervene in elections whenever it chose, encourage the break-up of the sovereign state of Serbia using bombs, invade Iraq on a tissue of falsehoods and then overthrow Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi without any UN resolution. As Putin commented in one of his acid asides that pepper Short’s account, when it came to concocting fables “those of us in the KGB were children compared to American politicians”. No wonder Xi Jinping of China and much of the world demur at the west’s claim to have done nothing to provoke the nightmare that has descended on Ukraine.

For all his recent whitewashing of Stalinism and Soviet history, in the early 1990s Putin understood the 1917 revolution had taken the country to an economic and political dead end. In his words, “the only thing they had to keep the country within common borders was barbed wire. And as soon as this barbed wire was removed, the country fell apart.” Yet running through all Putin’s thinking was a clear belief that the break-up of the Union in 1991 was a catastrophe for Russia; what was lost was not the Soviet dream but a country that physically stretched from Poland to the Pacific and historically back to Peter the Great and before. Putin mourned: “It was precisely those people in December 1917 who laid a time bomb under this edifice… which was called Russia… they endowed these territories with governments and parliaments. And now we have what we have.” Except we do not. For Putin and many of his fellow Russians have never understood how a country they believe saved the world from fascism at staggering personal cost just 50 years before dissolved in a matter of weeks.

Strikingly, the occasions Short records when outsiders have witnessed Putin’s inscrutable mask fracture nearly all relate to these “lost” lands, countries whose independent existence was to him an impossible outrage. There is the rant about Estonia to the British ambassador or former French president Nicolas Sarkozy’s magnificent record of Putin’s “violent diatribe” over Georgia and its leader, who should be “hung by his balls”. That only ended when Sarkozy retorted: “So your dream is to end up like Bush, detested by two-thirds of the planet?” Putin burst out laughing. “You scored a point there.” Finally, most importantly, over Ukraine, which, whisper it quietly, in its present shape truly was a creation of Stalin and Khrushchev. The tragedy may be that it has taken Putin’s actions, the atrocities committed by the Russian army and tens of thousands of deaths, to finally prove Ukraine’s existence to the man himself.

Critics point to Putin’s work for the KGB as revealing the core of the man, as so often investing its members with inhuman powers of control, deception, amorality and evil. Short, instead, places the real shaping of the man both before and after his KGB years. Born in the harsh courtyards of postwar Leningrad, he emerged a cautious operator, shy and unreadable, but with a startling streak of brutality. Working for the city’s famously liberal mayor through the whirlwind of chaos and violence that swept his city and Russia in the early 1990s, he forged lasting bonds with everyone from the new business elite to leading mafia bosses and senior players in the Kremlin. He labelled himself a bureaucrat, not a politician. Avoiding conspicuous consumption and not known for swimming in the oceans of corruption around him, he was at the same time not above buying himself a dissertation towards a Candidate of Sciences degree, whose subject was “Strategic Planning for the Rehabilitation of the Mineral Resources Base in the Leningrad Oblast”. Its true author, according to Short, would later receive “several hundred million dollars’ worth of shares”. Loyalty is a trademark and his friends have done very, very well over the years, as the puritan has spectacularly lost his inhibitions. His subsequent rise was public yet shadowy, a sequence of well-chosen battles engaged when he knew he could win.

Ironies haunt the book: “Those who believe that [military force] is the most efficient instrument of foreign policy in the modern world will fail again and again… One cannot behave in the world like a Roman emperor,” he said after one US military adventure. Equally haunting are the lost opportunities to avoid rubbing a proud nation’s nose in their defeat at every turn: expanding Nato to Russia’s very borders, breaking at the very least the spirit of clear promises; or not taking seriously Putin’s coherent attempt to create a joint front against radical Islam after 9/11, when he defied his own military’s cold war warriors to help Bush. Torture in Chechnya, it seems, can never be the same as torture in Guantánamo or Abu Ghraib to the victors. “We won, they didn’t,” trumped Bush senior in 1991; Clinton said “Yeltsin could eat his spinach”, while Obama more recently dismissed Russia as simply a “regional” power.

Short is too astute to indulge in easy post-event speculation about different outcomes. Instead, he charts the inexorable march away from the genuine more liberal aspirations of Putin’s early days to the harsh autocratic isolated tsar of recent years, from a Russia culturally and mentally in Putin’s words “an inalienable part of Europe” to the present rupture, which will surely separate it for at least a generation. Who remembers that Putin asked the BBC’s Bridget Kendall to moderate the first of his annual phone-ins to speak to the nation and the world? Now, he talks of the end of the “so-called liberal idea” while promoting traditional Russian spiritual values, the collective over the individual, rejecting the west in tones redolent of Soviet propaganda. But will a younger generation who have grown up feeding on internet social media, able to travel freely and getting information how and when they like, really admire an authoritarian regime that is rotten to its core? That was the challenge laid down by the anti-corruption campaigner, Alexei Navalny, and he had to be locked away . Can the ageing tsar, whose acolytes still seem keen to educate their offspring in Britain and the US when not out sailing on ever-larger yachts, really believe himself a persuasive model for those ancient values?

There is a blank evenness to Short’s prose, a steady accumulation of information built through intelligence and concentration on detail with emotions coiled tight, which makes this book a perfect mirror to its subject. He calls Putin a liar, regularly, but again and again he pulls back from laying direct responsibility on him for some of the more egregious acts. “Hard to judge” or “Nothing concrete suggests” and other such qualifiers litter his accounts of critical moments. Sometimes, they usefully temper the more extreme personal charges against Putin. Overall, however, they let him escape true responsibility, not for individual crimes, but for failing to transform Russia, instead reaching back to an arthritic mythical past, not forward to a different future.

The result is a step-by-step journey, whose penultimate chapter is a little surprisingly called “The Endgame”, hobbled by being published as the climax approaches, not after the event. Short, let alone history, has not had time to judge the success or failure of the latest horrifying act in Putin’s astonishing drive to make Russia great again.

Film-maker Angus Macqueen has helped create a platform of award-winning documentaries, Russia On Film

Putin: His Life and Times by Philip Short is published by Bodley Head (£30). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply

- Biography books

- Observer book of the week

- Vladimir Putin

- Politics books

- History books

Most viewed

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The New Tsar : The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

12 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station09.cebu on October 11, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Barnes & Noble

Ordering and Customer Service

- Apple iTunes

- Amazon Kindle

- Google eBookstore

- Blio Bookstore

- Table of Contents

- Chapter One

Subscribe to the Brookings Brief

Operative in the kremlin.

From the KGB to the Kremlin: a multidimensional portrait of the man at war with the West. Where do Vladimir Putin’s ideas come from? How does he look at the...

Fiona Hill and other U.S. public servants have been recognized as Guardians of the Year in TIME’s 2019 Person of the Year issue.

Mr. Putin was named one of the Financial Times Best Books for Summer 2015.

From the KGB to the Kremlin: a multidimensional portrait of the man at war with the West.

Where do Vladimir Putin’s ideas come from? How does he look at the outside world? What does he want, and how far is he willing to go?

The great lesson of the outbreak of World War I in 1914 was the danger of misreading the statements, actions, and intentions of the adversary. Today, Vladimir Putin has become the greatest challenge to European security and the global world order in decades. Russia’s 8,000 nuclear weapons underscore the huge risks of not understanding who Putin is.

Featuring five new chapters, this new edition dispels potentially dangerous misconceptions about Putin and offers a clear-eyed look at his objectives. It presents Putin as a reflection of deeply ingrained Russian ways of thinking as well as his unique personal background and experience.

Praise for the first edition

If you want to begin to understand Russia today, read this book. — Sir John Scarlett , former chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6)

For anyone wishing to understand Russia’s evolution since the breakup of the Soviet Union and its trajectory since then, the book you hold in your hand is an essential guide. — John McLaughlin , former deputy director of U.S. Central Intelligence

Of the many biographies of Vladimir Putin that have appeared in recent years, this one is the most useful. — Foreign Affairs

This is not just another Putin biography. It is a psychological portrait. — The Financial Times

Considering how busy you are, do you have time to read books? If so, which ones would you recommend? “. . . My goodness, let’s see. There’s Mr. Putin, by Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy. Insightful.” — Vice President Joseph Biden in Joe Biden: The Rolling Stone Interview

Related Books

Marvin Kalb

September 21, 2015

August 17, 2015

Henry Hardy, Isaiah Berlin Strobe Talbott

October 11, 2016

Fiona Hill is director of the Center on the United States and Europe and a senior fellow in Foreign Policy at Brookings.

Clifford G. Gaddy is a senior fellow in Foreign Policy at Brookings. Hill and Gaddy are coauthors of The Siberian Curse: How Communist Planners Left Russia Out in the Cold (Brookings, 2003).

Media Coverage

Fiona Hill warns about Russian political meddling in 60 Minutes interview

The Biggest Risk to This Election Is Not Russia. It’s Us.

What if Putin Disappeared for Real?

This Is What Putin Really Wants

The American Education of Vladimir Putin

We keep trying to understand Putin. Why do we keep getting him wrong?

Trump’s new Russia expert wrote a psychological profile of Vladimir Putin — and it should scare Trump

Mr Putin, Operative in the Kremlin by Fiona Hill and Clifford G Gaddy – review

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Vladimir Putin

By: History.com Editors

Published: September 25, 2023

Vladimir Putin (1952-) is a former KGB agent who has ruled Russia for more than two decades. Intent on restoring Russian might following the collapse of the Soviet Union , he has launched several military campaigns, including an invasion of Ukraine, and helped usher in what’s often described as a new Cold War . Meanwhile, he has steadily tightened his grip on power, persecuting political opponents, shuttering independent media outlets, and otherwise dismantling the country’s nascent democracy.

Putin's Early Years and Personal Life

Much about Vladimir Putin’s personal life remains murky. Born in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in 1952, he has recalled growing up modestly in a rat-infested communal apartment building. His parents, who lost two children prior to his birth—one of whom died during the prolonged Nazi siege of Leningrad in World War II —apparently doted on him despite working long hours. As a youth, he practiced martial arts and is reputed to have gotten into many fist fights.

In 1983, Putin married a flight attendant, Lyudmila Shkrebneva, with whom he has two daughters. (The couple divorced around 2013.) He is rumored to have fathered other children as well. Throughout his time in office, Putin has kept his family out of the public eye.

Putin as a KGB Agent

After studying law at Leningrad State University, Putin joined the KGB , the Soviet counterpart of the CIA. In the mid-1980s, he was sent to the city of Dresden in East Germany, where, in his words, he gathered “political intelligence,” in part by recruiting sources. Putin remained in Dresden during the fall of the Berlin Wall , and, with a risky bluff , purportedly prevented a crowd of protestors from storming the local KGB headquarters.

Putin's Political Rise

Putin returned to Leningrad in 1990 and claimed to have resigned from the KGB the following year. The subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union affected him deeply; he later called it the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century. Around that time, he got his political start as an aide to Anatoly Sobchak , his former teacher who became his mentor and St. Petersburg’s mayor.

In 1996, Sobchak lost his bid for re-election and later fled abroad amid corruption allegations. Yet Putin continued his meteoric rise, moving to Moscow, Russia’s capital, and securing one Kremlin post after another (while also defending an economics dissertation he allegedly plagiarized ). By 1998, Putin led the KGB’s main successor organization, and the following year President Boris Yeltsin named him prime minister, the country’s second-highest office, thereby elevating him from obscurity to heir apparent.

When an ailing and increasingly unpopular Yeltsin resigned on December 31, 1999, Putin took over as acting president. (Months later, he would win election to a full term.) Helped by rising oil and gas prices, the economy improved in the early 2000s and living standards rose. Many Russians saw him as bringing order and stability after the hyperinflation, tumultuousness, and perceived lawlessness of the Yeltsin years.

Putin's Consolidation of Power

In his first address as Russia’s president, Putin promised to protect freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and property rights, and he likewise announced his commitment to democracy. Yet democratic backsliding began almost immediately under his leadership. The Kremlin brought independent television networks under state control and shut down other news outlets; abolished gubernatorial and senatorial elections; curtailed the judiciary; and restricted opposition political parties. When elections took place, outside observers noted widespread voter irregularities. Putin’s system was sometimes referred to as a “managed democracy.”

Because Russia’s constitution barred a third consecutive term, Putin stepped down in 2008, with his longtime confidante Dmitry Medvedev taking over as president. But Putin retained the role of prime minister and left little doubt about who was really in charge. When Medvedev’s term ended in 2012, the two swapped positions, and Putin once again became president. He has occupied the top job ever since, at one point signing a law that allows him to stay in power until 2036.

Putin has habitually placed his friends and old intelligence colleagues in key posts, several of whom became extravagantly wealthy, and he’s propagated a cult of personality. Perceived opponents have been called “scum” and “traitors” and dealt with harshly. Some, like oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky, have been jailed, whereas others have wound up dead. In 2006, for example, investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya was gunned down on Putin’s birthday, and that same year Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko was assassinated in England with radioactive polonium.

More recently, opposition leader Aleksei Navalny was banned from running for president, survived an assassination attempt , and was then imprisoned on what’s widely considered to be politically motivated charges. Yet another high-profile death occurred in 2023, when Yevgeny Prigozhin was killed in a plane crash after launching a short-lived mutiny against Russia’s military leadership.

Putin's Relationship with the West

Many Western leaders originally approved of Putin, with U.S. President George W. Bush saying he had “looked the man in the eye,” found him “very straightforward and trustworthy,” and gotten a “sense of his soul.” Putin was the first foreign leader to call Bush following the terrorist attacks of September 11 , 2001. And though he opposed the Iraq War , Putin assisted in aspects of the so-called War on Terror . He moreover described Russia as a “friendly European nation” that desired “stable peace on the continent.”

Putin’s relationship with the West deteriorated, however, in part over NATO ’s 2004 expansion into seven Eastern European countries and over pro-Western revolutions that broke out in Georgia and Ukraine. Putin was furthermore irked by U.S. lobbying to bring Georgia and Ukraine into NATO and by its support for an independent Kosovo. In 2007, he accused the United States of overstepping “its national borders in every way.” Over time, Putin came to think of himself as a protector of traditional Russian values, standing up to a hypocritical and morally decadent West.

In 2014, as tensions escalated over Ukraine, Russia was expelled from the Group of Eight industrialized nations. Around that time, he granted asylum to U.S. whistleblower Edward Snowden . And, according to U.S. intelligence agencies , he interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election , greenlighting a computer hacking operation that infiltrated the campaign of Hillary Clinton .

Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump maintained generally friendly ties. But the U.S.-Russian relationship reached arguably its lowest point in decades following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Since then, Russia has been hit with a slew of economic sanctions, Ukraine has received much Western military assistance, and U.S. President Joe Biden has called Putin a “thug,” a “murderous dictator,” and a “war criminal.”

Putin's Wars

During his more than two decades in office, Putin has used the military in increasingly aggressive ways. Early in his tenure, he violently suppressed a separatist movement in the Russian republic of Chechnya. In 2008, he orchestrated a brief but large-scale invasion of Georgia , thus cementing Russian control of the breakaway regions Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Starting in 2015, he intervened in the Syrian civil war , among other things authorizing a prolonged bombardment of the city of Aleppo. Additionally, he has deployed Russian mercenaries in various African countries .

Putin’s most prolonged conflict has taken place in Ukraine . In 2014, when Ukrainian protestors ousted their Russian-backed president, Putin responded by annexing Crimea—which had been gifted from Russia to Ukraine during the Soviet era—and by backing a separatist insurgency in eastern Ukraine. Then, in 2022, he launched an all-out invasion of Ukraine, but failed to take Kiev, the capital. Heavy fighting has since claimed hundreds of thousands of lives . The Russian armed forces have been accused of purposely targeting civilians and committing torture and other atrocities, prompting the International Criminal Court to issue a warrant for Putin’s arrest (though he is unlikely to stand trial).

The Man Without a Face : The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin , by Masha Gessen, published by Riverhead Books, 2012. The Strongman : Vladimir Putin and the Struggle for Russia , by Angus Roxburgh, published by I.B. Tauris, 2012. First Person : An Astonishingly Frank Self-Portrait by Russia’s President Vladimir Putin , 2000. ‘The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin,’ by Steven Lee Myers. The New York Times , November 8, 2015. The Making of Vladimir Putin. The New York Times , March 26, 2022. Putin, Vladimir. Encyclopedia Britannica

HISTORY Vault: Vladimir Putin

A gripping look at Putin's rise from humble beginnings to brutal dictatorship, and his emergence as one of the gravest threats to America's security.

Who Is Vladimir Putin?

Philip Short’s “Putin” is an impressive biography but one that necessarily lacks the final chapters of the story.

- Share full article

By Peter Baker

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

PUTIN , by Philip Short

In the days after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Moscow suddenly felt different. My wife and I, serving there as correspondents, were overwhelmed by expressions of sympathy and solidarity. Russians we had never met faxed condolence letters. A teary-eyed stranger stopped me on the street brandishing a picture of herself at the World Trade Center from a trip years earlier. The outside of the American Embassy was carpeted with flowers, icons, crosses, candles and a note that said, “We were together at the Elbe, we will be together again.”

A young master of the Kremlin named Vladimir Putin seemed to take that to heart, pledging steadfast support for the United States. For a heady moment, it seemed as if the planet’s two dominant nuclear powers would rekindle the World War II alliance that led Russian and American troops to meet at Germany’s Elbe River in 1945. But now as then, it would not last. The sense of good will soon evaporated, and the illusion that Putin was a Western-oriented modernizer was shattered. Two decades later, Russia and America are facing off in a twilight struggle in Ukraine arguably as dangerous as the Cold War that followed the defeat of the Nazis.

Was that Putin’s fault or ours? Did we misjudge him or did we mislead him? Was it inevitable that Putin would come to see himself as a latter-day Peter the Great seeking to re-establish the czarist empire or could we have done more to anchor a post-Soviet Russia in the community of nations? Never have those questions been more profoundly relevant. Now weighing into the debate is the British journalist Philip Short, with his expansive new biography, “Putin,” which sees the rift between East and West largely through the eyes of its protagonist.

Short’s account is both perfectly and unfortunately timed, arriving just when we most need to understand Putin, yet missing the chapter that may yet define his place in history. The invasion of Ukraine does not take place until Page 656 of a 672-page text, having erupted just as Short was completing eight years of research and composition. Such is the peril of writing biographies of figures who are still alive and not finished writing their own stories.

But if the story is unavoidably incomplete, Short’s version nonetheless offers a compelling, impressive and methodically researched account of Putin’s life so far. He plumbs an array of sources, including his own interviews, to reconstruct the tale of a street brawler from a bleak communal apartment in postwar Leningrad who embarks on a mediocre career as a midlevel K.G.B. officer in East Germany only to make a stunning leap to power in Moscow following the chaos of 1990s post-Soviet Russia.

Short, a former journalist with the BBC, The Economist and The Times of London, adds to the library of insightful books about the Russian autocrat, including “The New Tsar,” by Steven Lee Myers; “Mr. Putin,” by Fiona Hill and Clifford G. Gaddy; “The Man Without a Face,” by Masha Gessen; and “Putin’s World,” by Angela Stent. But unlike those Russia specialists, he comes to his subject as a chronicler of some of history’s biggest villains, having written biographies of Pol Pot and Mao Zedong.

As critics observed about those volumes, Short’s determination to present a fully realized portrait of Putin may strike some as excessively sympathetic. “The purpose of this book is neither to demonize Putin — he is more than capable of doing that himself — nor to absolve him of his crimes,” Short writes, “but to explore his personality, to understand what motivates him and how he has become the leader that he is.”

In fact, he does absolve Putin of several crimes. Short opens with an extended examination of the never-solved apartment bombings of 1999 that were blamed on Chechen terrorists but suspected of being a government conspiracy to cement Putin’s path to power. Short exonerates Putin. He may be right; no one has ever definitively proved the case. But it is a curious way to start a book about an autocrat who is currently bombing plenty of other apartments in Ukraine. He likewise absolves Putin of notorious political attacks against the likes of Sergei Skripal, Anna Politkovskaya and Boris Nemtsov, while allowing that he probably was responsible for the gruesome poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko in London.

Yet Short’s book is no hagiography. He extensively covers the dark moments of Putin’s career — the leveling of Grozny during the second Chechen war, the reckless handling of the Moscow theater siege, the cynical exploitation of the terrorist attack on a school in Beslan to consolidate power, the crackdown on dissent at home, including the poisoning and imprisonment of Alexei A. Navalny. The Putin of Short’s book is not someone you would invite to dinner; he is crude and cold, arrogant and heartless. He is unmoved when his wife is in a serious car accident or when his dog is run over. His wife, a believer in astrology, once said he must have been born under the sign of the vampire. She is now, not surprisingly, his ex-wife.

There are small errors — Short writes, for example, that Start II was “still unratified by the U.S. Congress” in 2010 when in fact the treaty was ratified in 1996 — but these invariably slip into any work of this size and scope. More debatable may be some of his conclusions in which he adopts the Russian view. He equates Putin’s forcible annexation of Crimea to Western support for Kosovo’s independence, dismissing differences between the two as “nuances.” Indeed, Kosovo is one of “the West’s three cardinal sins” in Putin’s eyes “that had destroyed both sides’ hopes of building a better, more peaceful world after the collapse of the Soviet Union” (along with withdrawing from the Antiballistic Missile treaty and expanding NATO). Every Russian outrage is likened to some Western perfidy. Yes, the Russians interfered in the 2016 election but “the United States had done the same.” The deterioration in relations had a certain “inevitability” that was “largely the result of a series of Western, essentially American, decisions.”

Short advances the Russian argument that America betrayed a “promise” by Secretary of State James A. Baker III in 1990 that NATO jurisdiction would not move “one inch to the east.” In fact, there was no promise. Baker floated the idea during negotiations over reunification of Germany but later walked it back, and no such commitment was included in the resulting treaty that did extend NATO to East Germany with Moscow’s assent. By contrast, Short makes no mention of an actual promise Russia made in a 1994 agreement guaranteeing Ukraine’s sovereignty and forswearing the use of force against it, an accord Putin has obviously broken.

Indeed, Short accepts Putin’s explanation for his unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. “The State Department,” he writes, “insisted that the war had nothing to do with NATO enlargement and everything to do with Putin’s refusal to accept Ukraine’s existence as an independent state, which may have been good spin but was poor history.” Unless you read Putin’s own 5,000-word poor history published last year refusing to accept Ukraine’s existence as an independent state or remember that the invasion took place many, many years after the main NATO expansion and at a time when NATO membership for Ukraine was not seriously on the table.

It may be that all this was inevitable. It may be that the moments of Russian-American friendship were all exceptions to a generational struggle destined to be waged for decades to come. Putin seems to think so. Short recounts Putin’s memory of his meeting with Vice President Joe Biden in 2011.

“Don’t be under any illusion,” he told the future president. “We only look like you. … Russians and Americans resemble each other physically. But inside we have very different values.” Certainly, Biden would agree with that today.

PUTIN , by Philip Short | Illustrated | 864 pp. | Henry Holt & Company | $40

Peter Baker is the chief White House correspondent and has covered the last five presidents for The Times and The Washington Post. He is the author of seven books, most recently “The Divider: Trump in the White House, 2017-2021,” with Susan Glasser, to be published in September. More about Peter Baker

Our Coverage of the War in Ukraine

News and Analysis

Russian missiles streaked into Kyiv in the biggest assault on the Ukrainian capital in weeks, injuring several people and damaging several buildings.

Jake Sullivan, President Biden’s top national security official, made a secret trip to Kyiv to meet with President Volodymyr Zelensky and reaffirm the United States’ unwavering commitment to Ukraine.

Under pressure to come up with billions of dollars to support Ukraine’s military, the E.U. said that it had devised a legal way to use frozen Russian assets to help arm Ukraine.