- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK

by James Baldwin ‧ RELEASE DATE: May 24, 1974

This new Baldwin novel is told by a 19-year-old black girl named Tish in a New York City ghetto about how she fell in love with a young black man, Fonny. He got framed on a rape charge and she got pregnant before they could marry and move into their loft; but Tish and her family Finance a trip to Puerto Rico to track down the rape victim and rescue Fonny, a sculptor with slanted eyes and treasured independence. The book is anomalous for the 1970's with its Raisin in the Sun wholesomeness. It is sometimes saccharine, but it possesses a genuinely sweet and free spirit too. Along with the reflex sprinkles of hate-whitey, there are powerful showdowns between the two black families, and a Frieze of people who — unlike Fonny's father — gave up and "congregated on the garbage heaps of their lives." The style wobbles as Tish mixes street talk with lyricism and polemic and a bogus kind of Young Adult hesitancy. Baldwin slips past the conflict between fighting the garbage heap and settling into a long-gone private chianti-chisel-and-garret idyll, as do Fonny and Tish and the baby. But Baldwin makes the affirmation of the humanity of black people which is all too missing in various kinds of Superfly and sub-fly novels.

Pub Date: May 24, 1974

ISBN: 0307275930

Page Count: -

Publisher: Dial Books

Review Posted Online: Sept. 16, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: May 1, 1974

LITERARY FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by James Baldwin

BOOK REVIEW

by James Baldwin ; edited by Randall Kenan

by James Baldwin

THE MOST FUN WE EVER HAD

by Claire Lombardo ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 25, 2019

Characters flip between bottomless self-regard and pitiless self-loathing while, as late as the second-to-last chapter, yet...

Four Chicago sisters anchor a sharp, sly family story of feminine guile and guilt.

Newcomer Lombardo brews all seven deadly sins into a fun and brimming tale of an unapologetically bougie couple and their unruly daughters. In the opening scene, Liza Sorenson, daughter No. 3, flirts with a groomsman at her sister’s wedding. “There’s four of you?” he asked. “What’s that like?” Her retort: “It’s a vast hormonal hellscape. A marathon of instability and hair products.” Thus begins a story bristling with a particular kind of female intel. When Wendy, the oldest, sets her sights on a mate, she “made sure she left her mark throughout his house—soy milk in the fridge, box of tampons under the sink, surreptitious spritzes of her Bulgari musk on the sheets.” Turbulent Wendy is the novel’s best character, exuding a delectable bratty-ness. The parents—Marilyn, all pluck and busy optimism, and David, a genial family doctor—strike their offspring as impossibly happy. Lombardo levels this vision by interspersing chapters of the Sorenson parents’ early lean times with chapters about their daughters’ wobbly forays into adulthood. The central story unfurls over a single event-choked year, begun by Wendy, who unlatches a closed adoption and springs on her family the boy her stuffy married sister, Violet, gave away 15 years earlier. (The sisters improbably kept David and Marilyn clueless with a phony study-abroad scheme.) Into this churn, Lombardo adds cancer, infidelity, a heart attack, another unplanned pregnancy, a stillbirth, and an office crush for David. Meanwhile, youngest daughter Grace perpetrates a whopper, and “every day the lie was growing like mold, furring her judgment.” The writing here is silky, if occasionally overwrought. Still, the deft touches—a neighborhood fundraiser for a Little Free Library, a Twilight character as erotic touchstone—delight. The class calibrations are divine even as the utter apolitical whiteness of the Sorenson world becomes hard to fathom.

Pub Date: June 25, 2019

ISBN: 978-0-385-54425-2

Page Count: 544

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: March 3, 2019

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 15, 2019

LITERARY FICTION | FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

HOUSE OF LEAVES

by Mark Z. Danielewski ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 6, 2000

The story's very ambiguity steadily feeds its mysteriousness and power, and Danielewski's mastery of postmodernist and...

An amazingly intricate and ambitious first novel - ten years in the making - that puts an engrossing new spin on the traditional haunted-house tale.

Texts within texts, preceded by intriguing introductory material and followed by 150 pages of appendices and related "documents" and photographs, tell the story of a mysterious old house in a Virginia suburb inhabited by esteemed photographer-filmmaker Will Navidson, his companion Karen Green (an ex-fashion model), and their young children Daisy and Chad. The record of their experiences therein is preserved in Will's film The Davidson Record - which is the subject of an unpublished manuscript left behind by a (possibly insane) old man, Frank Zampano - which falls into the possession of Johnny Truant, a drifter who has survived an abusive childhood and the perverse possessiveness of his mad mother (who is institutionalized). As Johnny reads Zampano's manuscript, he adds his own (autobiographical) annotations to the scholarly ones that already adorn and clutter the text (a trick perhaps influenced by David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest ) - and begins experiencing panic attacks and episodes of disorientation that echo with ominous precision the content of Davidson's film (their house's interior proves, "impossibly," to be larger than its exterior; previously unnoticed doors and corridors extend inward inexplicably, and swallow up or traumatize all who dare to "explore" their recesses). Danielewski skillfully manipulates the reader's expectations and fears, employing ingeniously skewed typography, and throwing out hints that the house's apparent malevolence may be related to the history of the Jamestown colony, or to Davidson's Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a dying Vietnamese child stalked by a waiting vulture. Or, as "some critics [have suggested,] the house's mutations reflect the psychology of anyone who enters it."

Pub Date: March 6, 2000

ISBN: 0-375-70376-4

Page Count: 704

Publisher: Pantheon

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 2000

More by Mark Z. Danielewski

by Mark Z. Danielewski

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

May 19, 1974 If Beale Street Could Talk By JOYCE CAROL OATES IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK By James Baldwin. hough our turbulent era has certainly dismayed and overwhelmed many writers, forcing upon some the role of propagandist or, paradoxically, the role of the indifferent esthete, it is really the best possible time for most writers--the sheer variety of stances, the multiplicity of "styles" available to the serious writer, is amazing. Those who are bewildered by so many ostensibly warring points of view and who wish, naively, for a single code by which literature can be judged, must be reminded of the fact that whenever any reigning theory of esthetics subdues the others (as in the Augustan period), literature simply becomes less and less interesting to write. James Baldwin's career has not been an even one, and his life as a writer cannot have been, so far, very placid. He has been both praised and, in recent years, denounced for the wrong reasons. The black writer, if he is not being patronized simply for being black, is in danger of being attacked for not being black enough. Or he is forced to represent a mass of people, his unique vision assumed to be symbolic of a collective vision. In some circles he cannot lose--his work will be praised without being read, which must be the worst possible fate for a serious writer. And, of course, there are circles, perhaps those nearest home, in which he cannot ever win--for there will be people who resent the mere fact of his speaking of them, whether he intends to speak for them or not. "If Beale Street Could Talk" is Baldwin's 13th book and it might have been written, if not revised for publication, in the 1950's. Its suffering, bewildered people, trapped in what is referred to as the "garbage dump" of New York City--blacks constantly at the mercy of whites--have not even the psychological benefit of the Black Power and other radical movements to sustain them. Though their story should seem dated, it does not. And the peculiar fact of their being so politically helpless seems to have strengthened, in Baldwin's imagination at least, the deep, powerful bonds of emotion between them. "If Beale Street Could Talk" is a quite moving and very traditional celebration of love. It affirms not only love between a man and a woman, but love of a type that is dealt with only rarely in contemporary fiction--that between members of a family, which may involve extremes of sacrifice. A sparse, slender narrative, told first-person by a 19-year-old named Tish, "If Beale Street Could Talk" manages to be many things at the same time. It is economically, almost poetically constructed, and may certainly be read as a kind of allegory, which refuses conventional outbursts of violence, preferring to stress the provisional, tentative nature of our lives. A 22- year-old black man, a sculptor, is arrested and booked for a crime--rape of a Puerto Rican woman--which he did not commit. The only black man in a police line-up, he is "identified" by the distraught, confused woman, whose testimony is partly shaped by a white policeman. Fonny, the sculptor, is innocent, yet it is up to the accused and his family to prove "and to pay for proving" this simple fact. His fiancee, Tish, is pregnant; the fact of her pregnancy is, at times, all that keeps them from utter despair. The baby--the prospect of a new life--is connected with blacks' "determination to be free." At the novel's end, Fonny is out on bail, his trial postponed indefinitely, neither free nor imprisoned but at least returned to the world of the living. As a parable stressing the irresolute nature of our destinies, white as well as black, the novel is quietly powerful, never straining or exaggerating for effect. Baldwin certainly risked a great deal by putting his complex narrative, which involves a number of important characters, into the mouth of a young girl. Yet Tish's voice comes to seem absolutely natural and we learn to know her from the inside out. Even her flights of poetic fancy--involving rather subtle speculations upon the nature of male-female relationships, or black-white relationships, as well as her articulation of what it feels like to be pregnant--are convincing. Also convincing is Baldwin's insistence upon the primacy of emotions like love, hate, or terror: it is not sentimentality, but basic psychology, to acknowledge the fact that one person will die, and another survive simply because one has not the guarantee of a fundamental human bond, like love, while the other has. Fonny is saved from the psychic destruction experienced by other imprisoned blacks, because of Tish, his unborn baby and the desperate, heroic struggle of his family and Tish's to get him free. Even so, his father cannot endure the strain. Caught stealing on his job, he commits suicide almost at the very time his son is released on bail. The novel progresses swiftly and suspensefully, but its dynamic movement is interior. Baldwin constantly understates the horror of his characters' situation in order to present them as human beings whom disaster has struck, rather than as blacks who have, typically, been victimized by whites and are therefore likely subjects for a novel. The work contains many sympathetic portraits of white people, especially Fonny's harassed white lawyer, whose position is hardly better that the blacks he defends. And, in a masterly stroke, Tish's mother travels to Puerto Rico in an attempt to reason with the woman who has accused her prospective son-in-law of rape, only to realize, there, a poverty and helplessness more extreme that that endured by the blacks of New York City. While Tish is able to give birth to her baby, despite the misery of her situation, the assaulted woman suffers a miscarriage and is taken away, evidently insane. Nearly everyone has been manipulated. The white policeman, Bell, seems a little crazy, driven by his own racism rather than reason. He is a villain, of course (he has even shot and killed a 12-year-old black boy, some time earlier), but his villainy is made possible only by a system of oppression closely tied up with the mind-boggling stupidities of the law. For Baldwin, the injustice of Fonny's situation is self-evident, and by no means unique: "Whoever discovered America deserved to be dragged home, in chains, to die," Tish's mother declares near the conclusion of the novel. Fonny's friend, Daniel, has also been falsely arrested and falsely convicted of a crime, years before, and his spirit broken by the humiliation of jail and the fact--which Baldwin stresses, and which cannot be stressed too emphatically--that the most devastating weapon of the oppressor is that of psychological terror. Physical punishment, even death, may at times be preferable to an existence in which men are denied their manhood and any genuine prospects of controlling their own lives. Fonny's love for Tish can be undermined by the fact that, as a black man, he cannot always protect her from the random insults of whites. Yet the novel is ultimately optimistic. It stresses the communal bond between members of an oppressed minority, especially between members of a family, which would probably not be experienced in happier times. As society disintegrates in a collective sense, smaller human unity will become more and more important. Those who are without them, like Fonny's friend Daniel, will probably not survive. Certainly they will not reproduce themselves. Fonny's real crime is "having his center inside him," but this is, ultimately, the means by which he survives. Others are less fortunate. "If Beale Street Could Talk" is a moving, painful story. It is so vividly human and so obviously based upon reality, that it strikes us as timeless--an art that has not the slightest need of esthetic tricks, and even less need of fashionable apocalyptic excesses. Return to the Books Home Page

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

The Long Silence of Beale Street

James baldwin’s novel flopped in 1974. but barry jenkins’ film reveals the timely masterpiece it was..

It was Columbus Day, Oct. 12, 1973. From his home-in-exile in France, James Baldwin wrote his brother David to announce that he had just completed his first novel in five years. If Beale Street Could Talk may have been a story about the redemptive power of love, but it was written in the absolute conviction that “blood” was “on the wind” and that the powers that be were not long for this world. Nestled in the manuscript, Baldwin’s fifth novel, were rebukes such as this one, perfectly suited for the holiday: “Who ever discovered America deserved to be dragged home, in chains, to die.” Acknowledging he sounded like the “witness as prophet,” Baldwin called Beale Street “the strangest novel” he had “ever written.”

Barry Jenkins’ film adaptation of Beale Street , for which Jenkins was just nominated for an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay, feels like a revelation. That’s because it manages to convey the strangeness at the heart of the book: a romance that turns on social outrage, a family drama that’s also a searing protest against the carceral state. This strangeness nearly consigned Beale Street to oblivion when it was published by the Dial Press in 1974. Weighed down by reviews deeming it the product of a bygone era, the novel has, until now, attracted interest only among the author’s most devoted readers. Yet by working through this long-term neglect, director and screenwriter Jenkins has uncovered in Beale Street a story that appears fresher than ever.

The novel concerns a young couple in Harlem in the early 1970s: Tish, 19 years old and pregnant, and Fonny, 22 years old and incarcerated. Flashbacks recount how Tish and Fonny met and fell in love, and how they arrived at their predicament. Fonny is awaiting trial for a crime falsely pinned on him by Officer Bell, a white cop bent on exercising his authority over young black men. Once Bell ensnares Fonny in the system, the bureaucracy of incarceration is shown to be invested in suppressing anything that could dis prove an innocent man’s guilt.

Yet it’s precisely when Tish has to face these odds that her love for Fonny grows deep. Steadfast in her devotion, Tish is at the center of a concerted family effort to beat the system and get him free. By novel’s end, the family’s surname, Rivers, indicates the spiritual rebirth everyone stands to gain by weathering present injustices.

Baldwin’s intention was to hold these two storylines—of a couple falling in love and of a family facing adversity—together, to show that they were beautifully, terribly intertwined. Such was the condition of being black in America. But the message fell on deaf ears when Beale Street came out.

Get Slate Culture in Your Inbox

Thanks for signing up! You can manage your newsletter subscriptions at any time.

While reviews of the novel were mixed, Beale Street ’s detractors spoke the loudest. In the New York Times, Anatole Broyard called Baldwin more “dated” than his long-dead adversary Richard Wright, accusing the author of rehashing civil rights–era jeremiads against America. Christopher Bigsby agreed in the Guardian, charging him with “recreating the mood and deploying the images of a former decade.” In the Washington Post, Larry McMurtry linked this sense of datedness to a complaint shared by nearly every other critic: Tish’s first-person narration evinced “artistic bad judgment.” She was “not really credible,” as the Boston Globe’s Carl Senna put it, because she came across as “too sophisticated,” less a well-rounded character than a mouthpiece for Baldwin. The expectant mother’s voice struck reviewers as a gimmick to repackage a well-worn tale.

If Beale Street Could Talk was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection and appeared on the best-seller list for several weeks. But this initial burst of interest couldn’t stave off a deeper problem: Baldwin’s once-reliable liberal readership, according to Darryl Pinckney, editor of a collection of Baldwin’s late fiction , “had had enough of hearing about problems they no longer had the will to solve.” When it came to writing by black authors, white readers’ tastes in the 1970s had swerved away from righteous protest toward, as Pinckney puts it, “fantasies of resolution, of roots found, the past appeased.” The undertone of the novel’s critical reception was, quite simply: Get over it.

In a clear sign of those changes, Dial’s parent company, Dell, passed on the chance to release the paperback edition of Beale Street . Instead, New American Library, a reprint house with whom Baldwin hadn’t published in more than a decade, brought out the mass-market edition in early 1975. Gauzily rebranded as a “masterpiece about the love between a man and a woman,” the book now appeared as a straightforward romance, complete with a cover illustration of a nondescript couple holding each other at sunset. In short, the literary establishment didn’t know what to do with If Beale Street Could Talk because it didn’t know what to do with a white readership steadily turning its back on civil rights. Baldwin had intuited this when he called the novel his strangest. Carrying the banner for social justice into the 1970s, he meant Beale Street to be a forceful reminder that all had not been overcome just yet.

Nearly 45 years later, Jenkins has adapted Beale Street in the spirit of its author’s vision. Most notably, he emphasizes, rather than diminishes, Tish’s point of view. In the film, Tish (KiKi Layne) narrates her romance with Fonny (Stephan James) as if situated in a future point of time. The reflective quality in her voice points to an understanding to come, a bridge between her innocence and her experience. That tone is evident in the novel as well:

We crossed crowded Sixth Avenue, all kinds of people out hunting for Saturday night. But nobody looked at us, because we were together and we were both black. Later, when I had to walk these streets alone, it was different, the people were different, and I was certainly no longer a child.

Baldwin’s Tish is supposed to be more sophisticated than a white critic, for example, might expect: Her fight for Fonny’s freedom is spurred by her memory of where and how they fell in love. Decades later, Jenkins’ film takes the young heroine at her word against a tradition of reading her suspiciously.

Restoring Tish’s voice also shows how the novel’s social consciousness is issued from the future , not the past. Jenkins’ aestheticized style, with its dramatic shifts in tone, echoes Baldwin’s shifts in temporal register. A scene of the lovers wooing conjures the magic of rain-drenched streets in classic Hollywood cinema; a later one of Fonny’s confrontation with Officer Bell (Ed Skrein) evokes the grit of movies like Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets . But in the film’s most powerful scene, Tish watches Fonny take out his anger at Bell by throwing a bag of tomatoes against a wall. The resulting tableau resonates so powerfully because Fonny’s justified rage, and the risk of having it turn on him, feels like it could have happened yesterday.

Has Jenkins succeeded in one medium where Baldwin failed in another? The film’s fidelity to its source material points to an appreciation for what was there all along. “ Time ,” Baldwin’s Tish muses, “the word tolled like the bells of a church. Fonny was doing: time . In six months’ time , our baby would be here. Somewhere, in time, Fonny and I had met; somewhere, in time, we had loved; somewhere, no longer in time, but, now, totally, at time’s mercy, we loved.” Being in time and being at time’s mercy: This duality is how Baldwin conceives love and struggle, progress and setback, together, as two sides of the same coin.

If Beale Street Could Talk

By James Baldwin. Vintage International.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

It’s a message Baldwin’s black readers picked up from the beginning. In a rare rave review, Revish Windham wrote in the New York Amsterdam News that, by reading the novel, “one might find he has lived there too or maybe living there now without having realized the name, Beale Street, is changed.” Black feminist critic Trudier Harris judged it to be Baldwin’s strongest work, a story almost revolutionary in its simplicity: “They are just folks who love each other and who are committed to the welfare of those whom they love.” Beale Street was an idea, a blues spirit that traversed time and space, from Memphis, Tennessee, (where it actually runs) to New York. The novel felt like a direct address to black readers who could see the world through Tish’s eyes and recognize her and Fonny’s fate as their own.

From this angle, the only strange thing about Baldwin’s novel was his disregard for the sensibilities of a readership he once addressed so regularly. If Beale Street Could Talk signaled a break with the white liberals who had turned him into a star. And it’s exactly this studied indifference that makes Jenkins’ adaptation feel fresh today: Though its style is undoubtedly hybrid, the film refuses to appeal to the white gaze. It’s a story of black love, and of black struggle, that doesn’t wait for viewers who need catching up.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

If Beale Street Could Talk review – a heart-stopping love story

Moonlight director Barry Jenkins cements his high reputation with this mesmerising adaptation of James Baldwin’s novel

T he genius of writer-director Barry Jenkins’s film-making lies in his ability to take a story grounded in very specific circumstances and, through close attention to detail, make it universal. In the Oscar-winning Moonlight , he conjured a portrait of a young man from a hardscrabble, drug-riddled Miami neighbourhood finding harsh beauty in the precise minutiae of his protagonist’s life. Like all great coming-of-age movies, Moonlight struck a chord as timeless as that evoked by Truffaut’s Les Quatre Cents Coups , George Lucas’s American Graffiti or Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher . Now, Jenkins’s adaptation of James Baldwin ’s 1970s novel becomes a heart-stopping cinematic love story, told with a tough but tender truthfulness that left me weeping and swooning. It’s a terrific film, as sinewy as it is sensuous, interweaving stark social-realist themes of prejudice, oppression and imprisonment with a poetic evocation of love, loss and, ultimately, transcendence.

“Every black person born in America was born on Beale Street,” states the opening quotation from Baldwin, citing “the impossibility and the possibility, the absolute necessity, to give expression to this legacy”. From such boldly declarative beginnings, Jenkins moves to a gently swirling overhead shot of two seemingly shy young lovers walking together, the sound of sustained elegiac strings accompanying their footsteps. “You ready for this?” asks 19-year-old Tish (KiKi Layne) , to which Fonny (Stephan James) replies: “I’ve never been more ready for anything in my whole life...”

It’s a scene trembling with promise and expectation, full of cinema’s dreamy ability to capture the elusive quintessence of love. But that ethereal sense of promise comes crashing down to earth on the next beat as we hear Tish’s voice telling us she hopes that “nobody has ever had to look at anybody they love through glass…”

Like so many young African American men, Fonny (aka Alonzo) has been arrested and jailed on a trumped-up charge, following a run-in with a grudge-bearing white cop (Ed Skrein, oozing menace). Tish is pregnant and promises Fonny he’ll be out and back in Harlem before their baby is born. But while Tish’s family, led by protective matriarch Sharon (Oscar-favourite Regina King) and down-to-earth Joseph (Colman Domingo), are accepting and proud, Fonny’s God-bothering mother (a fearsome Aunjanue Ellis) responds with hostility and spite, blaming Tish for her son’s supposed fall from grace. Can the warring clans put aside their differences for the sake of the next generation?

Jenkins cites the phrase “Love brought you here” as his favourite line from Baldwin’s novel, and those words resonate throughout this rich and vibrantly melancholic film. While the bond between Tish and Fonny is spine-tingling (a discreetly framed love scene rivals the intimacy of the love scene in Nic Roeg’s Don’t Look Now ), the strength of their connection is echoed in the dynamics of their extended families. Layne and James are perfectly cast as the young couple, but the power of their performances is matched by supporting players such as Teyonah Parris, in firecracker form as Tish’s older sister Ernestine, and Brian Tyree Henry (so brilliant in Widows ) as close friend Daniel Carty, who has similarly suffered injustice.

As for Regina King, her brilliantly modulated performance is a masterclass in physical understatement. One moment stands out – as Tish sits in the kitchen, preparing to tell her mother that she is pregnant, James Laxton’s camera adopts Tish’s point of view, watching Sharon from behind. “Mamma… ,” says Tish, tentatively, and even before she turns to face us, an almost imperceptible movement of King’s neck and shoulders tells us that Sharon knows exactly what her daughter is about to say.

As before, Jenkins invites the audience to look directly into his characters’ eyes, highlighting the sense of connection by stretching and slowing time, taking his lead from the “chopped-and-screwed” beats that have long fascinated this most musical film-maker. Just as the narrative shuffles past and present like cards in a dexterously dealt hand, so Jenkins invites us to focus on the moment, turning seconds into minutes with sensual slow-mo.

Meanwhile, Nicholas Britell’s subtly counterintuitive score brushes up against classic vinyl cuts (the ritual of putting on a record is evoked more than once), creating a musical mosaic that both anchors the drama in the here and now while expanding it beyond the specifics of time and place. The result is another mesmerising and wholly immersive experience from a film-maker whose love of the medium of cinema – and fierce compassion for Baldwin’s finely drawn characters – shines through every frame.

- If Beale Street Could Talk

- The Observer

- Drama films

- Barry Jenkins

- James Baldwin

Barry Jenkins: ‘Maybe America has never been great’

The Lion King 2 to be directed by Moonlight's Barry Jenkins

Barry Jenkins: ‘When you climb the ladder, you send it back down’

Beale Street star KiKi Layne: 'Black love is so powerful in the face of injustice'

How Barry Jenkins shows that more is less in Beale Street

Moonlight's Barry Jenkins on Oscar fiasco: 'It’s messy, but kind of gorgeous'

Why Moonlight should win the best picture Oscar

Iowa State Daily

- Best games of the Iowa State men's basketball season

- Iowa State falls short at home, UCF sweeps

- Residence hall student leaders recognized at IRHA banquet

- Arab Month, Arabic culture celebrated at Arab Night 2024

- PHOTOS: Greek Week Treds Tournament

- CELT striving for cohesion in micro-credential offerings

- Nepalese Students’ Association to hold Nepali Night 2081

- Aquatic center groundbreaking, ‘Stash the Trash’ among upcoming city events

- Iowa State competes close to home at Jim Duncan Invitational

- Cyclones welcome No. 5 Cowgirls to Ames

Book Review: “If Beale Street Could Talk” by James Baldwin

Content Warning: This review contains mentions of sexual violence.

Editor’s Note: This review has potential spoilers but I leave a good chunk of the narrative out for the prospective reader.

“Neither love nor terror makes one blind: indifference makes one blind.”

– James Baldwin, “If Beale Street Could Talk”

One reads a novel, or should, for the simple reason of life application. One ought to pick apart a book for that elusive and ever-generic term, “meaning,” which lingers around the contemporary conversations of literature just as much as it does when a relative discovers you have a tattoo. People always ask the same question: what is the point?

Baldwin’s novels always have a “point” — and unlike much of contemporary fiction, Baldwin is not watered down and cliche. On the contrary, his writing colors the page with a lively, pulsating rhythm and flow, not only pleasing to the aesthete but also for those searching for meaning.

“If Beale Street Could Talk” is the latest novel I read from Baldwin’s vast collection. It is about a 19-year-old Black woman named Tish (her actual name is Clementine) who falls in love with a Black man named Fonny (actual name Alonzo). The narrative centers on these two characters but also brings in both Tish’s and Alonzo’s families.

One day, when Tish and Fonny were at a grocery store, a menacing and predatorial man sexually harassed Tish. Fonny was not with her but was up the street looking for something else, reassuring Tish that he would be right back.

Once Fonny returns, he sees what is occurring and urgently intervenes, defending Tish against the aggressor. This causes quite a commotion, enough for Officer Bell to intervene. At this point, we begin to see the central tension of the book, which acts as a general theme across Baldwin’s books: that of the Black struggle, the tension between desired normalcy and bleak reality. Officer Bell ignores the man who forced himself on Tish and instead targets Fonny because he is Black, telling him that he will take Fonny to the station. It is only after the white grocer runs out and tells Officer Bell the truth that Officer Bell decides to let Fonny go. I describe this scene in particular because it provides context for the entire book.

Officer Bell wanted to get even with Fonny for being humiliated. After a woman, Mrs. Rogers was raped, Officer Bell claimed he saw Fonny running away from the scene. This obvious falsehood was made even more clear when Officer Bell placed Fonny as the only Black man in the criminal lineup after Mrs. Rogers said the perpetrator was Black. Officer Bell saw the opportunity for revenge and achieved it.

What follows is a story of hope and heartbreak. The novel shows the importance of family, of friendship, of love, of tragedy, of despair, of justice, of fairness and of truth. Baldwin never misses an opportunity to deftly describe the human condition, whatever that may be. He disintegrates the opinion that your own will single-handedly determines your fate and illustrates how some people and their hefty aspirations for self-determination are impossible if the odds of society are forever determined against them. However, this should never cause one to ruin themselves, to harm others, to contribute to an imperfect society.

As Baldwin writes: “I know about suffering; if that helps. I know that it ends. I ain’t going to tell you no lies, like it always ends for the better. Sometimes it ends for the worse. You can suffer so bad that you can be driven to a place where you can’t ever suffer again: and that’s worse.”

– James Baldwin, “If Beale Street Could Talk”

Reading Baldwin is always enjoyable and thought-provoking. Read all of him if you can.

Rating: 8.5/10

- book review

- If Beale Street Could Talk

- james baldwin

- novel review

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Iowa State Daily. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, send our student journalists to conferences and off-set their cost of living so they can continue to do best-in-the-nation work at the Iowa State Daily.

The independent student newspaper of Iowa State and Ames since 1890

- Advertise with Us!

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Literature & Fiction

- United States

Buy new: $4.67

Other sellers on amazon.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

If Beale Street Could Talk Paperback – October 10, 2006

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 197 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Vintage

- Publication date October 10, 2006

- Dimensions 7.9 x 5.1 x 0.6 inches

- ISBN-10 0307275930

- ISBN-13 978-0307275936

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

From the Publisher

Editorial reviews, about the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.

- Publisher : Vintage; Reprint edition (October 10, 2006)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 197 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0307275930

- ISBN-13 : 978-0307275936

- Item Weight : 6.8 ounces

- Dimensions : 7.9 x 5.1 x 0.6 inches

- #331 in Black & African American Urban Fiction (Books)

- #651 in Family Life Fiction (Books)

- #1,832 in Literary Fiction (Books)

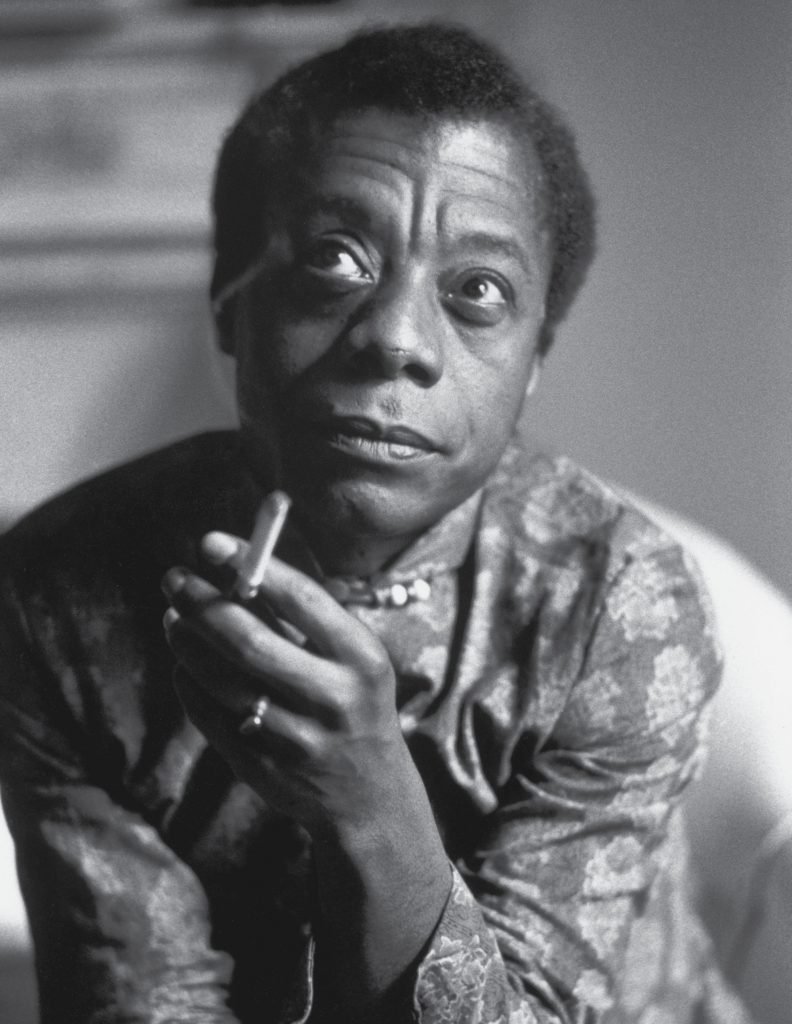

About the author

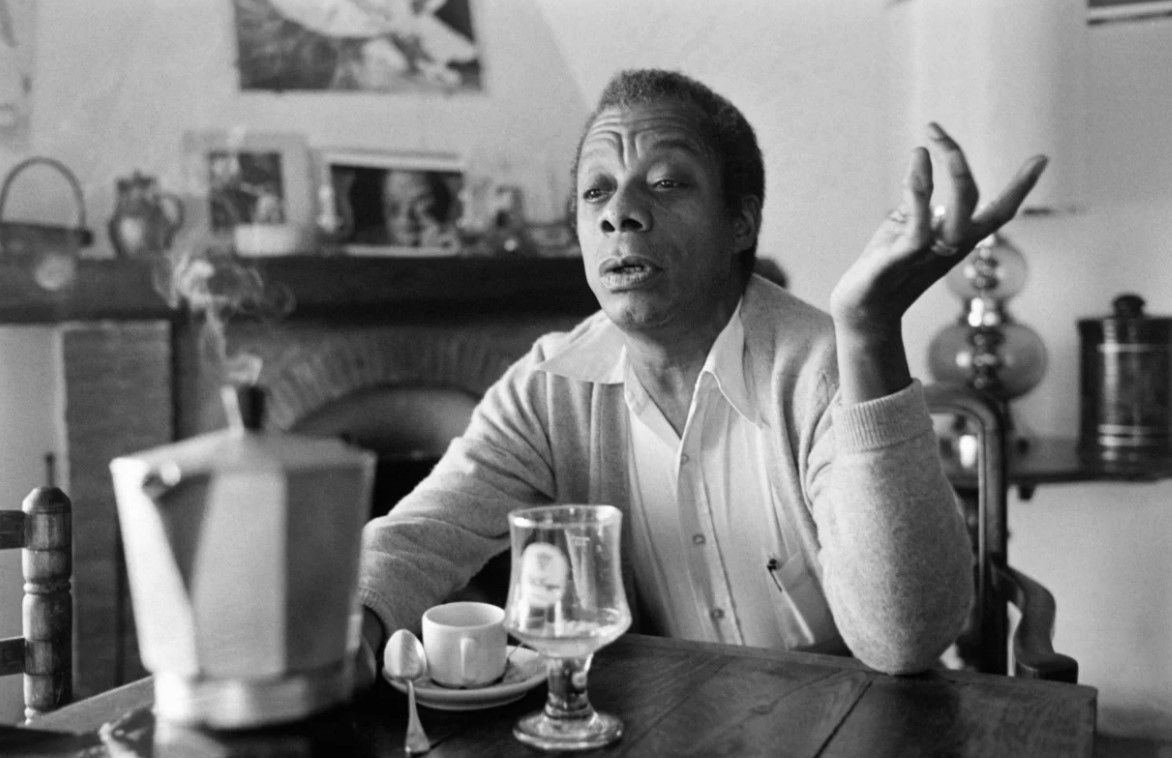

James baldwin.

James Baldwin (1924-1987) was a novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic, and one of America's foremost writers. His essays, such as "Notes of a Native Son" (1955), explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-twentieth-century America. A Harlem, New York, native, he primarily made his home in the south of France.

His novels include Giovanni's Room (1956), about a white American expatriate who must come to terms with his homosexuality, and Another Country (1962), about racial and gay sexual tensions among New York intellectuals. His inclusion of gay themes resulted in much savage criticism from the black community. Going to Meet the Man (1965) and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968) provided powerful descriptions of American racism. As an openly gay man, he became increasingly outspoken in condemning discrimination against lesbian and gay people.

Photo by Allan warren (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, if beale street could talk.

Now streaming on:

We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here . "If Beale Street Could Talk" is now streaming on Hulu. #BlackLivesMatter.

Director Barry Jenkins summons James Baldwin ’s spirit in his adaptation of the author’s 1974 book, “If Beale Street Could Talk” by immediately quoting him onscreen: “Every black person born in America was born on Beale Street, whether in Jackson, Mississippi, or in Harlem, New York. Beale Street is our legacy.” For Baldwin, Beale Street doesn’t just run through Memphis, Tennessee; it runs through the DNA of African-Americans, a symbol of our shared experience in these United States. Although we are not monolithic in thought, we are all beholden to the issues Baldwin interrogated and challenged with the words he spoke and wrote, issues like racism, injustice and so on.

History at large is written by the victors, but Black history is protected and passed on by our storytellers, the folks—famous and not—whose life lessons filled in the blanks for what was so often missing from, or corrupted by, the general narrative. The stories of our ancestors’ trials and tribulations form a generational artery that can never be severed so long as there is someone left to tell the tale.

Jenkins’ decision to let the original storyteller live and breathe throughout “If Beale Street Can Talk” is a wise one. We feel Baldwin’s gaze whenever the director and his cinematographer James Laxton execute the director’s trademark of having his actors look into the camera. The lovers at the heart of this story are technically staring at each other—and by extension, at us—with a devotion that is as tactile as the image itself. Like all love stories, this one occasionally takes fluttery flight, triggered by the gentlest and most subtle of gestures and emotions. But even at his most romantic, Baldwin never let the reader fall too deeply into the starry-eyed ether; the barbed scorpion’s tail of harsh reality remains ever-present, waiting to strike at any moment and break the spell. This realism is rendered in such matter-of-fact fashion that it becomes smoothly woven into the narrative without artifice.

The first words we see are by Baldwin, as are the first words we hear. Tish ( KiKi Layne , making a stunning feature debut) utters a sentence you can find on page four of the book: “I hope that nobody has ever had to look at anybody they love through glass.” The beloved person under glass is Fonny ( Stephan James ), her boyfriend and the father of her unborn child. Fonny is incarcerated for a rape he did not commit. Each time the film visits him in prison, we’re reminded of the cruelly taunting symbolism of Baldwin’s line. Glass is transparent to the eye but impervious to the touch; a lover’s embrace is so close and yet so far away.

But there is no “woe-is-me”-style posturing in these scenes. Instead, Fonny and Tish find a semblance of normalcy tinged with sadness and elevated by hope. Sometimes the duo even laugh at situations that arise, sharing the gallows humor entrenched in the lives of the oppressed or downtrodden. This kind of dark humor snakes its way through “If Beale Street Could Talk,” sometimes finding itself in a release of relief, other times getting caught in one’s throat when situations suddenly become tense. This film knows that suffering and joy are strange bedfellows, opposites that are quite often prone to finding each other, sometimes within the same beat.

Thankfully, Fonny is not kept behind bars for the length of the film, as the retelling of his love story allows Jenkins to fiddle with the timeframe. We see the evolution of Fonny and Tish, first as rebellious, somewhat antagonistic children and later as devoted soulmates. In those latter scenes of burgeoning affection, Jenkins orchestrates a sense of pace and timing that, abetted by Nicholas Britell ’s excellent score, makes the viewer swoon. There’s a woozy affectation to these moments—as Alan Jay Lerner once wrote, it’s almost like being in love. So whenever the narrative shifts back to Fonny trapped behind that glass, the result has a shattering effect on us.

Surrounding the leads are their respective, supportive families. Played by a murderers’ row of superb character actors led by the brilliant Regina King , the parents and siblings of Fonny and Tish are as memorable and well-drawn as the main characters. We meet Tish’s family first. Her parents, Sharon and Joseph (King and Colman Domingo , respectively) and her sister, Ernestine ( Teyonah Parris ) hear about Tish’s pregnancy first. The sequence unfolds in meticulously crafted moments that almost feel sculpted by Jenkins and his actors, none of whom are afraid of the awkward pauses that would realistically inhabit this type of discussion.

King plays this scene as if she already knows what her daughter has to tell her. When Tish calls to her mother before pausing to formulate her thoughts, Sharon’s “yes, baby?” response is so delicate, so impeccably rendered that we’re stunned that King could wring that much maternal love out of two words. Parris adds even more power to the moment. “Unbow your head, sister,” she says with a fierceness meant to instill pride. The bond between these women feels unbreakable, a testament to the actors who build it in such a short period of time.

Ernestine also serves as a bit of comic relief in the extremely tense meeting that takes place once James decides to invite Fonny’s parents over to share the news. Fonny’s parents are played by Michael Beach and the always welcome Aunjanue Ellis . They are joined by Fonny’s sisters ( Ebony Obsidian and Dominique Thorne ). While the men get along like a house on fire, there’s a palpable tension amongst the women, who seem to tolerate one another less robustly than the men do. The Hunt women clearly think they’re better, and Tish’s pregnancy will give them something to gloat about for sure.

Since this parental meeting is the novel’s most memorable scene, Jenkins’ casting reveals itself to be very clever, especially if you are familiar with the actors. Beach is always shorthand for somebody trifling, Domingo is boisterous yet no-nonsense and Ellis is a master at quickly defining her pride-filled characters. The Hunts are a Sanctified bunch who will immediately inspire nods of recognition for anyone with Sanctified relatives, though Mr. Hunt is definitely not a strict follower of this religious doctrine. When things come to a vicious boil, it’s one of those moments where big laughs give way to even bigger shocks. Though Jenkins tones down Baldwin’s verbal vitriol, the scene lands just as effectively as it does in the book.

Fonny and Tish have their own memorable scenes together, from their first night of lovemaking to their attempt to rent an apartment in a neighborhood whose renters do not want them there. This latter scene features Dave Franco in a landlord role that at first felt like stunt casting (the critics at my screening audibly groaned, in fact). But he, Layne and James create this ebullient, magical scene of pantomime that in lesser hands would come off as silly and trite. It’s the film’s most joyful moment. But again, we know what lies ahead for Fonny, so an underlying sadness is also present.

Though “If Beale Street Could Talk” is a series of vignettes, it holds together better than most films of this type. Each separate piece is tethered to the dual running threads of its love story and its tale of injustice. Though there are White cops in the latter story who are clearly villainous, the mistaken rape victim is also a person of color who has escaped back to Puerto Rico to deal with her trauma. This development sends Sharon to Puerto Rico to attempt to bring her back so she can exonerate Fonny. Before trying to find this woman, Sharon contemplates how she should dress. This scene unfolds wordlessly, yet King plays it so physically well that no words are necessary. There’s an unapologetic Blackness to her thought process as she decides whether to wear a wig or her natural hair—it’s the hairstyle equivalent of code-shifting—and what she settles on seems right, at least in that moment.

“If Beale Street Could Talk” leaves the viewer with feelings of anger at the fate society forces Fonny to accept, but it also conjures up some optimism for his and Tish’s future. This isn’t a happy film but it isn’t a hopeless one, either. The most striking thing that you’ll take with you is that Baldwin’s novel was written 44 years ago, but it’s just as timely now. Not much has changed for people of color, which probably wouldn’t surprise the author. And yet, he’d demand we not give up. This film powerfully conveys that message. The struggle is real, but so is the joy. We live, we laugh, we love and we die. But we are not gone. Our story continues, carried onward by our storytellers.

"If Beale Street Could Talk" is now streaming on Hulu.

Odie Henderson

Odie "Odienator" Henderson has spent over 33 years working in Information Technology. He runs the blogs Big Media Vandalism and Tales of Odienary Madness. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here .

Now playing

Simon Abrams

Steve! (Martin): A Documentary in Two Pieces

Brian tallerico.

In the Land of Saints and Sinners

Asleep in My Palm

Tomris laffly.

Love Lies Bleeding

Ricky Stanicky

Monica castillo, film credits.

If Beale Street Could Talk (2018)

117 minutes

KiKi Layne as Clementine "Tish" Rivers

Stephan James as Alonzo "Fonny" Hunt

Regina King as Sharon Rivers

Colman Domingo as Joseph Rivers

Teyonah Parris as Ernestine Rivers

Michael Beach as Frank Hunt

Aunjanue Ellis as Mrs. Hunt

Ebony Obsidian as Adrienne Hunt

Dominique Thorne as Sheila Hunt

Diego Luna as Pedrocito

Finn Wittrock as Hayward

Ed Skrein as Officer Bell

Emily Rios as Victoria Rogers

Pedro Pascal as Pietro Alvarez

Brian Tyree Henry as Daniel Carty

Dave Franco as Levy

- Barry Jenkins

- James Baldwin

Director of Photography

- James Laxton

Original Music Composer

- Nicholas Britell

- Joi McMillon

- Nat Sanders

Latest blog posts

O.J. Simpson Dies: The Rise & Fall of A Superstar

Which Cannes Film Will Win the Palme d’Or? Let’s Rank Their Chances

Second Sight Drops 4K Releases for Excellent Films by Brandon Cronenberg, Jeremy Saulnier, and Alexandre Aja

Wagner Moura Is Still Holding On To Hope

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Movie Reviews

In the luminous 'if beale street could talk,' a perfect love meets an imperfect world.

Monica Castillo

Shining Like Moonlight : Tish (KiKi Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James) share a fleeting moment in Barry Jenkins' If Beale Street Could Talk . Tatum Mangus /Annapurna Picture hide caption

Shining Like Moonlight : Tish (KiKi Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James) share a fleeting moment in Barry Jenkins' If Beale Street Could Talk .

If Beale Street Could Talk opens with a quote from James Baldwin and a slow, sweeping violin score that will be heard many more times. Tish (KiKi Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James) walk along the edge of a New York City park, with greenery on one side and highways and cityscape on the other. Their clothes are coordinated in yellow and navy as if they belong to one another. The details of this outdoor world soon melt away, leaving only close-ups of the actors' faces. They are looking into each other so deeply that nothing else exists. Not the problems that are about to come their way, the tragedy or heartaches that will soon eclipse their young lives.

Those stares will change over the course of Barry Jenkins' adaptation of Baldwin's novel about love, family, New York City and racism. The bliss of their budding romance will be put on hold when Fonny is accused of raping a Puerto Rican woman, Victoria Rogers (Emily Rios), by a racist white police officer (Ed Skrein). Not long after Fonny goes to jail, Tish reveals that she is pregnant with his child. Although Fonny's father and Tish's family toast to the new generation, Fonny's deeply devout Christian mother and sisters receive the news less excitedly. They are the least of Tish's worries, however, as now she must figure out how to make ends meet as an unwed pregnant 19-year-old separated from her partner by prison bars and thick glass.

Movie Interviews

Director barry jenkins talks on behalf of 'beale street'.

Pop Culture Happy Hour

Npr's movie preview: 15 new films to watch — and watch out for — this fall.

Those gorgeous, longing stares at the beginning of the film grow resentful, hurt and frightened as the months wear on. It begins to feel uncomfortable to be so close to this much pain, but Jenkins' camera is steady – and so is Tish's resolve to fight for her love. Her mother Sharon (Regina King) defends her daughter against criticism and steps in to help her future son-in-law's case.

In the movie, Jenkins enhances the subtleties of his actors' performances, growing small personal moments into epics. Layne and James' chemistry is sweet and believable, playing the parts of lifelong friends who committed to one another. Jenkins lavishes close-up after close-up on their young, hopeful faces, capturing each sly smile and direct glance. King gives a powerful performance as Tish's determined mother who's trying to do everything to protect her child's chance at love and justice. Some of her most moving scenes have no words. After a meeting goes poorly, she cries and curses at having potentially botched the conversation that could have lead to a break in the case.Jenkins' camera zooms in on Sharon's hands clenched on a photo of Tish and Fonny, holding it slightly above her bowed head like an appeal to a higher power for help.

Barry Jenkins is an avowed fan of Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai, naming movies like Chunking Express and In the Mood for Love among his favorites . You can see echoes of influences in Jenkins' feature debut Medicine for Melancholy in the shots where the movie's couple trades smiles and flirty glances without any words. It's also evident in Chiron's longing stares at the camera throughout Jenkins' Oscar-winning film, Moonlight . But in If Beale Street Could Talk , those close-ups are a way to show the audience that no matter what bars or glass comes between them,Tish and Fonny are still connected. The world can still melt away, not as clearly or as often as it used to, but they still look at each other in a way that might make you feel weak in the knees.

There's a timeless quality to the film despite its specific setting. Jenkins employs very few pop culture or news references that might get in the way of the romantic drama, only late '60s or early '70s clothes and hairstyles clue us in. The earthy tones and warm color schemes of Fonny's sculptures, the furniture in Tish's home, and the couple's outfits look luxurious in the lens of cinematographer James Laxton, who also worked with Jenkins on Moonlight .

Beale Street may play on similar visual notes of longing but on a warmer register than the cool blues and tones in Moonlight . As if the look of the film and its heartbreaking story weren't soul-stirring enough, composer Nicholas Britell complements the imagery with possibly this year's most moving score, a wave of slow violins that ebb and flow throughout the film's most emotional scenes.

The problems of racial profiling and abuse Fonny and his friend Daniel (Brian Tyree Henry) deal with are not relics of the past. Jenkins inserts striking black-and-white stills of the Bronx and Harlem in that era, of black men working on prison chain gangs and of white police officers enacting various acts of police brutality to underscore his point. Yet in this terrible situation and cruel world, Tish and Fonny find moments of sweetness, of loving caresses and the romantic feeling like they're the only ones on a crowded subway. If Beale Street Could Talk is at once a tribute to love and a call for its defense against racist hatred, all told in an artfully composed tragedy.

Film Review: ‘If Beale Street Could Talk’

'Moonlight' director Barry Jenkins brings a colorful, idealistic eye to James Baldwin's 1974 novel about a young couple tragically separated by a false arrest.

By Peter Debruge

Peter Debruge

Chief Film Critic

- ‘Challengers’ Review: Zendaya and Company Smash the Sports-Movie Mold in Luca Guadagnino’s Tennis Scorcher 13 hours ago

- Digging Into the Cannes Lineup, Sight Unseen: Heavy on English Movies and Light on Women 1 day ago

- Cannes Film Festival Reveals Lineup: Coppola, Cronenberg, Lanthimos, Schrader and Donald Trump Portrait ‘The Apprentice’ in Competition 2 days ago

“I hope that nobody has ever had to look at anybody they love through glass,” 19-year-old Tish shares in the opening scene of James Baldwin’s “ If Beale Street Could Talk ,” moments before breaking the news that she’s pregnant to boyfriend Fonny, imprisoned for an unpardonable crime. A work of social realism elevated to poetic heights by the sheer beauty of its voice and the humanism of its spirit — a feat director Barry Jenkins also managed to achieve with his previous film, “Moonlight” — Baldwin’s Harlem-set novel takes readers on two separate journeys, depending largely on their racial background.

Writing in 1974, he knew that many white people would see a black man behind bars and jump to their own conclusions, drawing fast assumptions that Baldwin uses the rest of the book to challenge and untangle: How can Tish hope to raise this child if she’s poor and her baby daddy’s in jail? Black folks, on the other hand, know that just because Fonny’s been arrested doesn’t make him a criminal. If anything, he’s a victim of an unfair system, which raises an entirely different question in their minds: What are the odds that justice will be served and he’ll be allowed to return to his family?

As an African-American filmmaker fresh off his big Oscar win, Jenkins doesn’t seem especially worried about the “what white people think” side of that equation (and why should he be, when the story is his to tell?). Instead, he adapts Baldwin’s novel for more or less the same personal reasons he wrote “Moonlight” — as a chance to explore the black experience in America — and in both films, prison is the thing that derails what could have been a beautiful life. In “Beale Street,” which proves even more playful with traditional chronology than “Moonlight,” the characters’ belief in love never wavers amid the setbacks, which makes an impactful statement about the way African-Americans must cope with a broken system — one reinforced by the use of vintage black-and-white snapshots of black life throughout.

Jenkins, who lifts most of Tish’s narration and a fair amount of the dialogue directly from the novel, uses that heartbreaking “through glass” line early on, but not before inserting an idyllic opening scene between Tish (Kiki Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James) that looks like it could belong in “La La Land”: Beneath a canopy of yellow leaves, they walk along the Hudson River, he dressed in a bright yellow button-down and an unwashed blue denim jacket, she wearing a blue dress beneath a canary yellow coat.

Reality melts away as the camera cranes to follow these two lovebirds, establishing a tone that’s more “Little Miss Sunshine” than “Moonlight” for much of Jenkins’ third (and third-best) feature, right down to the too-cute period costumes and distracting wallpaper choices. The movie quotes Baldwin as saying, “Every black person born in America was born on Beale Street,” but this one may as well be located inside a snow globe. In deciding how to translate Baldwin’s prose to the screen, Jenkins has done the equivalent of turn Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” into a Douglas Sirk movie (or put Alice Walker’s’ “The Color Purple” through the Steven Spielberg filter).

That may not be the right approach for everyone, but it will work for some, particularly those for whom Jenkins’ “Beale Street” signifies another prominent stride in the crusade for African-American representation on-screen. If the director’s take on Tish and Fonny’s romance seems a bit too idealistic, that’s merely his way of heightening the tragic situation created by Fonny’s unjust arrest for the rape of a Puerto Rican woman, who picked him out of a lineup at the suggestion of a racist cop. No one who knows Fonny would ever believe that he could do such a thing, nor does Jenkins allow so much as the shadow of a doubt to enter into audiences’ minds.

By casting an actor as handsome as James as Fonny, he challenges the notion that only Tish could appreciate his odd looks (in the book, her best friend describes “how ugly he was, with skin just like raw, wet potato rinds and eyes like a Chinaman and all that nappy hair and them thick lips”), inviting audiences to crush on him too. Likewise, he softens Tish’s character, substituting her painfully awkward naïveté with a kind of soft-spoken shyness. When the two first make love, it’s not a sloppy-passionate awakening for her so much as the gentlest deflowering a young woman could hope for — all of which is valid but not quite what Baldwin had in mind. As an author, he actively resisted Jenkins’ relatively superficial black-Barbie-and-Ken aesthetic, instead painting his characters as flawed, funny-looking, and frequently contradictory human beings.

What’s most surprising about Jenkins’ approach is the way it departs from that of his previous two features. In his 2008 debut, the desaturated, “Before Sunrise”-like “Medicine for Melancholy,” two hyper-articulate San Francisco singles spend all night sharing ideas. They never run out of things to say, whereas Tish and Fonny have a more unspoken connection, expressing themselves practically in slow motion when they do choose to talk. In “Moonlight,” black boys look blue (per the title of the Tarell Alvin McCraney play upon which it was based), while this time around, cinematographer James Laxton gives everyone a warm, golden glow, which offers a different perspective on their personalities as well — less melancholy in the face of similar legal challenges.

Of course, there’s nothing that says Jenkins can’t go a completely different way from either Baldwin’s or his own earlier style. If “Moonlight” was specific to his and McCraney’s Florida upbringing, then “Beale Street” is meant to be something more universal, relatable to African-Americans everywhere. Instead of getting caught up in the gaudy costume and production design, we’re meant to look past such superficial details to what the characters are going through, whether it’s the way Tish and her family — outspoken sister Ernestine (Teyonah Parris) and unwaveringly supportive mother Sharon (Regina King) — defend her pregnancy to her judgmental would-be mother-in-law (Aunjanue Ellis) or a tense encounter with a bigoted cop (Ed Skrein) after Fonny starts a fight at the neighborhood bodega. But that can be tough when, in a scene where a Jewish landlord (Dave Franco) is the first person to seriously consider renting to them, his flashy sweater distracts from the scene’s true point: that the world doesn’t give a couple like Tish and Fonny a fair shake.

Still, in other aspects, the film’s style serves to heighten the experience, particularly in the nonlinear way the narrative unfolds, flowing naturally back and forth between their present struggle — including a fantastic sequence when King, all but channeling “Foxy Brown,” flies to Puerto Rico to confront Fonny’s accuser — and defining moments before his arrest. Jenkins doesn’t have the budget to re-create Harlem as it was circa 1974 (see the James Earl Jones-Diahann Carroll romance “Claudine” for a glimpse of the neighborhood at the time), but that doesn’t seem to be his goal in any case. Rather, if “Beale Street” is to be a universal expression of the African-American legacy, as Baldwin intended, then Jenkins wants to show that love and family are the key to his community’s survival.

RELATED VIDEO:

Reviewed at Toronto Film Festival (Special Presentations), Sept. 9, 2018. MPAA Rating: R. Running time: 119 MIN.

- Production: An Annapurna Pictures release of a Pastel, Plan B, Annapurna Pictures production. Producers: Adele Romanski, Sara Murphy, Barry Jenkins, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, Megan Ellison. Executive producers: Brad Pitt, Sarah Esberg, Chelsea Barnard, Jillian Longnecker, Mark Ceryak, Caroline Jaczko.

- Crew: Director, screenplay: Barry Jenkins, based on the novel by James Baldwin. Camera (color, widescreen): James Laxton. Editors: Joi McMillon, Nat Sanders. Music: Nicholas Britell.

- With: KiKi Layne, Stephan James, Regina King , Colman Domingo, Teyonah Parris, Michael Beach, Aunjanue Ellis, Dave Franco, Diego Luna, Pedro Pascal, Emily Rios, Ed Skrein, Finn Wittrock, Brian Tyree Henry.

More From Our Brands

Judge halts texas ag’s probe into media matters, kanye west is now facing an $18 million loss on his tadao ando-designed malibu house, arizona coyotes are no more, will move to salt lake city, be tough on dirt but gentle on your body with the best soaps for sensitive skin, fire country poll: would you watch a sheriff fox spinoff, verify it's you, please log in.

If Beale Street Could Talk Book vs Movie Review

You can read the blog, or you can click on one of the icons below to listen to the podcast version click here for more listening options.

**Warning: Spoilers for both book and movie!**

If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin (1974)

If Beale Street Could Talk directed by Barry Jenkins (2018)

If Beale Street Could Talk is a novel, written by the great African American writer James Baldwin. Even though it is fiction, it is very personal to Baldwin and his experience being a black man in America. He spent a lot of his life living abroad, but is quoted as saying, “Once you find yourself in another civilization,” he notes, “you’re forced to examine your own.” A snippet from his biography on American Masters says, “Although he spent a great deal of his life abroad, James Baldwin always remained a quintessentially American writer. Whether he was working in Paris or Istanbul, he never ceased to reflect on his experience as a black man in white America. In numerous essays, novels, plays and public speeches, the eloquent voice of James Baldwin spoke of the pain and struggle of black Americans and the saving power of brotherhood.”

Beale Street is told from the perspective of Tish, a 19 year old African American living in New York. We learn the story of her and her fiancé, Fonny, who was arrested for a crime he didn’t commit. After he has been in prison for a couple months, she finds out she is pregnant with his child.

This could be considered a romance, but it is largely about being black in America. Tish and her family work tirelessly to get Fonny out of jail, but due to the deep-rooted racism in the justice system, this is not an easy task. Dealing with the stress of an innocent man she loves being behind bars is juxtaposed with her feeling the life growing in her belly.

Thoughts on Book

This is a very poetic book, and there is a beautiful passage where Tish is talking to her sister about Fonny’s trial, which reads,

‘We are certainly in it now, and it may get worse. It will, certainly—and now something almost as hard to catch as a whisper in a crowded place, as light and as definite as a spider’s web, strikes below my ribs, stunning and astonishing my heart—get worse. But that light tap, that kick, that signal, announces to me that what can get worse can get better. Yes. It will get worse. But the baby, turning for the first time in its incredible veil of water, announces its presence and claims me; tells me, in that instant, that what can get worse can get better; and that what can get better can get worse. In the meantime—forever—it is entirely up to me. The baby cannot get here without me. And, while I may have known this, in one way, a little while ago, now the baby knows it, and tells me that while it will certainly be worse, once it leaves the water, what gets worse can also get better. It will be in the water for a while yet: but it is preparing itself for a transformation. And so must I.’

I listened to the audiobook of this, and when I heard an especially beautiful passage, I made a mental note to go to the book and find and highlight it. I was able to go back and find a few, but there are a couple others I couldn’t find. From the above passage, and another I will share later, you can see what an incredible writer Baldwin was.

The audiobook is narrated by Bahni Turpin and I highly recommend listening to her narration. It may be my favorite audiobook narration I have listened to so far! Her voice acting is more powerful and expressive than some of the acting in the actual movie! But we’ll get to that later.

I actually have now read/listened to this book twice. I read it about six months ago, but at the time I wasn’t doing much with this podcast. I knew I wanted to come back around to it, and decided, even though the book was still fairly fresh in my mind, I decided to read it a second time. I could see some readers not liking Baldwins writing style as much, but I think anyone who considers themselves a bookworm of sorts, will appreciate and love this book. The second time around was just as good, maybe even better, then my first go around.

The movie was released in 2018 and was directed by Barry Jenkins. Jenkins had won best picture at the Academy Awards just two years prior for Moonlight. I didn’t look into this movie at all until having read the book, and when I saw it was directed by Jenkins, I felt he was the absolute perfect choice. Moonlight is an incredible movie and is also very poetic. Moonlight being the amazing movie that it is, I couldn’t help but compare it with his version of Beale Street. Unfortunately, it doesn’t quite stack up. But that shouldn’t deter any of you who are thinking of watching Beale Street.

Kiki Layne is in the lead role as Tish. I thought she was well cast, however, in some scenes her acting was more subdued than I would have liked. She is also the narrator, and many of the lines are taken straight from the book. I liked this, because as I said, there are some beautiful passages, and it would have been a shame not to showcase Baldwin’s writing. Some viewers thought the passages were out of place though. What sounds good in writing, doesn’t always translate well to the screen and doesn’t sound natural. I agree to a certain extent, there are some scenes where it might not come across as natural, but it didn’t bother me as much as it did others.

Stephan James plays Fonny and I thought he was excellent. However, I didn’t think he and Layne had the best chemistry throughout the movie. I did really like the scene where they are having dinner with Daniel. In the book, this moment is described as,

“Fonny: chews on the rib, and watches me: and, in complete silence, without moving a muscle, we are laughing with each other. We are laughing for many reasons. We are together somewhere where no one can reach us, touch us, joined. We are happy, even, that we have food enough for Daniel, who eats peacefully, not knowing that we are laughing, but sensing that something wonderful has happened to us, which means that wonderful things happen, and that maybe something wonderful will happen to him.”

The movie really captures this well and you feel the joy as the three of them eat. There are also many scenes where the character is looking and sometimes talking straight to the camera. Not breaking the fourth wall though, because the camera is in place where the person is they are talking to. During the dinner, we see Tish and Fonny straight on, as they look into the camera, into each other, sharing this moment.

Brian Tyree Henry is in the smaller role as Daniel. Though he doesn’t have much screen time, he plays a very important character, who has some powerful and tragic dialogue as we learn what he has been through. He has recently been in prison for two years, arrested for a crime he didn’t commit. Telling how the cops and the system manipulated him to plead guilty to a lesser crime, then the original one they pinned on him which he didn’t do. A foreshadowing to what will soon happen to Fonny.

Regina King is Tish’s mom, Sharon. She won a best supporting actress Oscar for her role in this movie and it’s well deserved! She is an incredible actress, and recently directed her first feature film, One Night in Miami.

Colman Domingo plays Tish’s dad, and Emily Rios gives a powerful performance as Victoria.

Family Differences

The book of course, gives more details on the characters than the movie does, which is to be expected. Ernestine for example, was a bigger role in the book and we really get a feel for her has a person. Joseph is also fleshed out more, and a scene that I liked in the book, but was left out in the movie, is when he sits her down and tells her she needs to quit her job. Not only to ensure the health of the baby, but also so that she can make it to her 6pm visit to Fonny every day. She had started missing days, in order to work more and save up more money. Joseph tells her that looking after the baby and Fonny are more important. The movie does though have a very touching scene where he holds Tish and comforts her.

Sharon has the biggest role of the family members, and we see what a strong, loving woman she is in both the book and movie.

Officer Bell

Officer Bell is the policeman who has a run-in with Fonny at the vegetable stand, and thereon out, has it in for Fonny. The actor who plays Bell is Ed Skrein. He didn’t have the same physical apparency as is given in the book of Bell, and he also seems younger. Other reviewers thought Bell’s appearance distracted from the movie, because he is a very “ugly” and cruel looking man. He was a bit overdone in my opinion as well, but I wouldn’t say his looks and acting took me out of the movie.

There is a scene that was left out from the book, where Tish says she is walking alone, and Bell comes up to her and speaks to her in a threatening way. The book also shows the lawyer, Hayward, telling them that he knows Bell is a racist and that he has already killed a 12 year old black boy recently. This isn’t mentioned in the movie.

Victoria and the arrest

The book also tells us how Victoria says she was raped by a black guy, but then in the lineup, Fonny was the only full black person they had. So of course, Victoria picked him out. Further showing the injustice of the system.

Victoria’s story is very similar in both book and movie. She disappears and is found in Puerto Rico, where she is from. Sharon is the only one who can go speak with her and try to get her to testify in favor of Fonny. I read how powerful this scene is in the movie, and how incredible King is in it. Maybe that raised my expectations, because even though the scene was well done, it wasn’t as powerful as the scene in the book. Though King does do an amazing job, when Victoria is taken away, you can see the sadness, frustration and desperation on her face.

Both book and movie we hear that Victoria isn’t quite right mentally. In the movie, from there Victoria simply disappears. The book we learn that she was a prostitute in Puerto Rico, had been pregnant, and had a miscarriage. She is taken somewhere into the mountains where she is never seen again.

The book and movie do show compassion for Victoria, but the movie I think shows more compassion. In the book, Tish sees a picture of Victoria, and calls her, her mortal enemy. I think Baldwin does this though to make a point. The system pits people against each other, so Tish thinks Victoria (another minority) is the enemy, rather than thinking of Bell and the system as the enemy. The movie doesn’t have this line, and it realistically shows that trauma Victoria has experienced, and the audience is never left feeling like she is the enemy in any way.

Fonny and his family

Once again, there is more backstory on Fonny’s family in the book. His mom is a religious nut, and his sisters are very high and might types. The women in the family don’t think much of Fonny, and don’t like Tish. Frank though, Fonny’s dad, loves Fonny. Frank, it seems, is meant to appear as the ‘good guy’ in this family dynamic, but honestly, he just seems like an angry, abusive man. Granted, of course he’s angry, his son has been wrongfully arrested, and his wife and daughters aren’t doing much to help. There is a scene in the book where Frank and Joseph are talking about the situation. Things get heated, and the daughters come into the living room and ask if everything is okay. They had been acting pretty ambivalent about Fonny, so it’s fair Frank yells at them when they ask. But then he says how if they were any kind of person, they would be out prostituting themselves, to get money together to help Fonny.

The movie also has the scene where Fonny’s mom says a horrible thing to Tish, but then Frank hits her so hard she falls down onto the floor Of course, the mom was messed up to say what she did, but Frank certainly has some major faults of his own.

There is also a sex scene early on between Frank and his wife, which is just plain awkward and also doesn’t show Frank in very good light.