An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.11(2); Spring 2007

Critical Appraisal of Clinical Studies: An Example from Computed Tomography Screening for Lung Cancer

Introduction.

Every physician is familiar with the impact that findings from studies published in scientific journals can have on medical practice, especially when the findings are amplified by popular press coverage and direct-to-consumer advertising. New studies are continually published in prominent journals, often proposing significant and costly changes in clinical practice. This situation has the potential to adversely affect the quality, delivery, and cost of care, especially if the proposed changes are not supported by the study's data. Reports about the results of a single study do not portray the many considerations inherent in a decision to recommend or not recommend an intervention in the context of a large health care organization like Kaiser Permanente (KP).

… in many cases, published articles do not discuss or acknowledge the weaknesses of the research …

Moreover, in many cases, published articles do not discuss or acknowledge the weaknesses of the research, and the reader must devote a considerable amount of time to identifying them. This creates a problem for the busy physician, who often lacks the time for systematic evaluation of the methodologic rigor and reliability of a study's findings. The Southern California Permanente Medical Group's Technology Assessment and Guidelines (TAG) Unit critically appraises studies published in peer-reviewed medical journals and provides evidence summaries to assist senior leaders and physicians in applying study findings to clinical practice. In the following sections, we provide a recent example of the TAG Unit's critical appraisal of a highly publicized study, highlighting key steps involved in the critical appraisal process.

Critical Appraisal: The I-ELCAP Study

In its October 26, 2006, issue, the New England Journal of Medicine published the results of the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP) study, a large clinical research study examining annual computed tomography (CT) screening for lung cancer in asymptomatic persons. Though the authors concluded that the screening program could save lives, and suggested that this justified screening asymptomatic populations, they offered no discussion of the shortcomings of the study. This report was accompanied by a favorable commentary containing no critique of the study's limitations, 1 and it garnered positive popular media coverage in outlets including the New York Times , CNN, and the CBS Evening News . Nevertheless, closer examination shows that the I-ELCAP study had significant limitations. Important harms of the study intervention were ignored. A careful review did not support the contention that screening for lung cancer with helical CT is clinically beneficial or that the benefits outweigh its potential harms and costs.

Critical appraisals of published studies address three questions:

- Are the study's results valid?

- What are the results?

- Will the results help in caring for my patient?

We discuss here the steps of critical appraisal in more detail and use the I-ELCAP study as an example of the way in which this process can identify important flaws in a given report.

Are the Study's Results Valid?

Assessing the validity of a study's results involves addressing three issues. First, does the study ask a clearly focused clinical question ? That is, does the paper clearly define the population of interest, the nature of the intervention, the standard of care to which the intervention is being compared, and the clinical outcomes of interest? If these are not obvious, it can be difficult to determine which patients the results apply to, the nature of the change in practice that the article proposes, and whether the intervention produces effects that both physician and patient consider important.

The clinical question researched in the I-ELCAP study 2 of CT screening for lung cancer is only partly defined. Although the outcomes of interest—early detection of lung carcinomas and lung cancer mortality—are obvious and the intervention is clearly described, the article is less clear with regard to the population of interest and the standard of care. The study population was not recruited through a standardized protocol. Rather, it included anyone deemed by physicians at the participating sites to be at above-average risk for lung cancer. Nearly 12% of the sample were individuals who had never smoked nor been exposed to lung carcinogens in the workplace; these persons were included on the basis of an unspecified level of secondhand smoke exposure. It is impossible to know whether they were subjected to enough secondhand smoke to give them a lung cancer risk profile similar to that of a smoker. It is also not obvious what was considered the standard of care in the I-ELCAP study. Although it is common for screening studies to compare intervention programs with “no screening,” the lack of a comparison group in this study leaves the standard entirely implicit.

Second, is the study's design appropriate to the clinical question ? Depending on the nature of the treatment or test, some study designs may be more appropriate to the question than others. The randomized controlled trial, in which a study subject sample is randomly divided into treatment and control groups and the clinical outcomes for each group are evaluated prospectively, is the gold standard for studies of screening programs and medical therapies. 3, 4 Cohort studies, in which a single group of study subjects is studied either prospectively or at a single point in time, are better suited to assessments of diagnostic or prognostic tools 3 and are less valid when applied to screening or treatment interventions. 5 Screening evaluations conducted without a control group may overestimate the effectiveness of the program relative to standard care by ignoring the benefits of standard care. Other designs, such as nonrandomized comparative studies, retrospective studies, case series, or case reports, are rarely appropriate for studying any clinical question. 5 However, a detailed discussion of threats to validity arising within particular study designs is beyond the scope of this article.

The I-ELCAP study illustrates the importance of this point. The nature of the intervention (a population screening program) called for a randomized controlled trial design, but the study was in fact a case series. Study subjects were recruited over time; however, because the intervention was an ongoing annual screening program, the number of CT examinations they received clearly varied, and it is impossible to tell from the data presented how the number of examinations per study subject is distributed within the sample. With different study subjects receiving different “doses” of the intervention, it thus becomes impossible to interpret the average effect of screening in the study. In particular, it is unclear how to interpret the ten-year survival curves the report presents; if the proportion of study subjects with ten years of data was relatively small, the survival rates would be very sensitive to the statistical model chosen to estimate them.

The lack of a control group also poses problems. Without a comparison group drawn from the same population, it is impossible to determine whether early detection through CT screening is superior to any other practice, including no screening. Survival data in a control group of unscreened persons would allow us to determine the lead time, or the interval of time between early detection of the disease and its clinical presentation. If individuals in whom stage I lung cancer was diagnosed would have survived for any length of time in the absence of screening, the mortality benefit of CT screening would have been overstated. Interpreting this interval as life saved because of screening is known as lead-time bias. The lack of a comparable control group also raises the question of overdiagnosis; without survival data from control subjects, it cannot be known how many of the lung cancers detected in I-ELCAP would have progressed to an advanced stage.

… does the paper clearly define the population of interest, the nature of the intervention, the standard of care to which the intervention is being compared, and the clinical outcomes of interest?

The types of cancers detected in the baseline and annual screening components of the I-ELCAP study only underscore this concern. Of the cancers diagnosed at baseline, only 9 cancers (3%) were small cell cancer, 263 (70%) were adenocarcinoma, and 45 (22%) were squamous cell cancer. Small cell and squamous cell cancers are almost always due to smoking. Data from nationally representative samples of lung cancer cases generally show that 20% of lung cancers are small cell, 40% are adenocarcinoma, and 30% are squamous cell. The prognosis for adenocarcinoma is better even at stage I than the prognoses for other cell types, especially small cell. 6 The I-ELCAP study data suggest that baseline screening might have detected the slow-growing tumors that would have presented much later.

A third question is whether the study was conducted in a methodologically sound way . This point concerns the conduct of the study and whether additional biases apart from those introduced by the design might have emerged. A discussion of the numerous sources of bias, including sample selection and measurement biases, is beyond the scope of this article. In randomized controlled trials of screening programs or therapies, it is important to know whether the randomization was done properly, whether the study groups were comparable at baseline, whether investigators were blinded to group assignments, whether contamination occurred (ie, intervention or control subjects not complying with study assignment), and whether intent-to-treat analyses were performed. In any prospective study, it is important to check whether significant attrition occurred, as a high dropout rate can greatly skew results.

In the case of the I-ELCAP study, 2 these concerns are somewhat overshadowed by those raised by the lack of a randomized design. It does not appear that the study suffered from substantial attrition over time. Diagnostic workups in the study were not defined by a strict protocol (protocols were recommended to participating physicians, but the decisions were left to the physician and the patient). This might have led to variation in how a true-positive case was determined.

What Are the Results?

Apart from simply describing the study's findings, the results component of critical appraisal requires the reader to address the size of the treatment effect and the precision of the treatment-effect estimate in the case of screening or therapy evaluations. The treatment effect is often expressed as the average difference between groups on some objective outcome measure (eg, SF-36 Health Survey score) or as a relative risk or odds ratio when the outcome is dichotomous (eg, mortality). In cohort studies without a comparison group, the treatment effect is frequently estimated by the difference between baseline and follow-up measures of the outcome, though such estimates are vulnerable to bias. The standard errors or confidence intervals around these estimates are the most common measures of precision.

The results of the I-ELCAP study 2 were as follows. At the baseline screening, 4186 of 31,567 study subjects (13%) were found by CT to have nodules qualifying as positive test results; of these, 405 (10%) were found to have lung cancer. An additional five study subjects (0.015%) with negative results at the baseline CT were given a diagnosis of lung cancer at the first annual CT screening, diagnoses that were thus classified as “interim.” At the subsequent annual CT screenings (delivered 27,456 times), 1460 study subjects showed new noncalcified nodules that qualified as significant results; of these, 74 study subjects (5%) were given a diagnosis of lung cancer. Of the 484 diagnoses of lung cancer, 412 involved clinical stage I disease. Among all patients with lung cancer, the estimated ten-year survival rate was 88%; among those who underwent resection within one month of diagnosis, estimated ten-year survival was 92%. Implied by these figures (but not stated by the study authors) is that the false-positive rate at the baseline screening was 90%—and 95% during the annual screens. Most importantly, without a control group, it is impossible to estimate the size or precision of the effect of screening for lung cancer. The design of the I-ELCAP study makes it impossible to estimate lead time in the sample, which was likely substantial, and again, the different “doses” of CT screening received by different study subjects make it impossible to determine how much screening actually produces the estimated benefit.

… would my patient have met the study's inclusion criteria, and if not, is the treatment likely to be similarly effective in my patient?

Will the Results Help in Caring for My Patient?

Answering the question of whether study results help in caring for one's patients requires careful consideration of three points. First, were the study's patients similar to my patient ? That is, would my patient have met the study's inclusion criteria, and if not, is the treatment likely to be similarly effective in my patient? This question is especially salient when we are contemplating new indications for a medical therapy. In the I-ELCAP study, 2 it is unclear whether the sample was representative of high-risk patients generally; insofar as nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke were recruited into the trial, it is likely that the risk profiles of the study's subjects were heterogeneous. The I-ELCAP study found a lower proportion of noncalcified nodules (13%) than did four other chest CT studies evaluated by our group (range, 23% to 51%), suggesting that it recruited a lower-risk population than these similar studies did. Thus, the progression of disease in the presence of CT screening in the I-ELCAP study might not be comparable to disease progression in any other at-risk population, including a population of smokers.

The second point for consideration is whether all clinically important outcomes were considered . That is, did the study evaluate all outcomes that both the physician and the patient are likely to view as important? Although the I-ELCAP study did provide data on rates of early lung cancers detected and lung cancer mortality, it did not address the question of morbidity or mortality related to diagnostic workup or cancer treatment, which are of interest in this population.

Finally, physicians should consider whether the likely treatment benefits are worth the potential harms and costs . Frequently, these considerations are blunted by the enthusiasm that new technologies engender. Investigators in studies such as I-ELCAP are often reluctant to acknowledge or discuss these concerns in the context of interventions that they strongly believe to be beneficial. The I-ELCAP investigators did not report any data on or discuss morbidity related to diagnostic procedures or treatment, and they explicitly considered treatment-related deaths to have been caused by lung cancer. Insofar as prior research has demonstrated that few pulmonary nodules prove to be cancerous, and because few positive test results in the trial led to diagnoses of lung cancer, it is reasonable to wonder whether the expected benefit to patients is offset by the difficulties and risks of procedures such as thoracotomy. The study report also did not discuss the carcinogenic risk associated with diagnostic imaging procedures. Data from the National Academy of Sciences' Seventh report on health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation 7 suggest that radiation would cause 11 to 22 cases of cancer in 10,000 persons undergoing one spiral CT. This risk would be greatly increased by a strategy of annual screening via CT, which would include many additional CT and positron-emission tomography examinations performed in diagnostic follow-ups of positive screening results. Were patients given annual CT screening for all 13 years of the I-ELCAP study, they would have absorbed an estimated total effective dose of 130 to 260 mSv, which would be associated with approximately 150 to 300 cases of cancer for every 10,000 persons screened. This is particularly critical for the nonsmoking study subjects in the I-ELCAP sample, who might have been at minimal risk for lung cancer; for them, radiation from screening CTs might have posed a significant and unnecessary health hazard.

In addition to direct harms, Eddy 5 and other advocates of evidence-based critical appraisal have argued that there are indirect harms to patients when resources are spent on unnecessary or ineffective forms of care at the expense of other services. In light of such indirect harms, the balance of benefits to costs is an important consideration. The authors of I-ELCAP 2 argued that the utility and cost-effectiveness of population mammography supported lung cancer screening in asymptomatic persons. A more appropriate comparison would involve other health care interventions aimed at reducing lung cancer mortality, including patient counseling and behavioral or pharmacologic interventions aimed at smoking cessation. Moreover, the authors cite an upper-bound cost of $200 for low-dose CT as suggestive of the intervention's cost-effectiveness. Although the I-ELCAP study data do not provide enough information for a valid cost-effectiveness analysis, the data imply that the study spent nearly $13 million on screening and diagnostic CTs. The costs of biopsies, positron-emission tomography scans, surgeries, and early-stage treatments were also not considered.

… did the study evaluate all outcomes that both the physician and the patient are likely to view as important?

Using the example of a recent, high-profile study of population CT screening for lung cancer, we discussed the various considerations that constitute a critical appraisal of a clinical trial. These steps include assessments of the study's validity, the magnitude and implications of its results, and its relevance for patient care. The appraisal process may appear long or tedious, but it is important to remember that the interpretation of emerging research can have enormous clinical and operational implications. In other words, in light of the stakes, we need to be sure that we understand what a given piece of research is telling us. As our critique of the I-ELCAP study report makes clear, even high-profile studies reported in prominent journals can have important weaknesses that may not be obvious on a cursory read of an article. Clearly, few physicians have time to critically evaluate all the research coming out in their field. The Technology Assessment and Guidelines Unit located in Southern California is available to assist KP physicians in reviewing the evidence for existing and emerging medical technologies.

Acknowledgments

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

- Unger M. A pause, progress, and reassessment in lung cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2006 Oct 26; 355 (17):1822–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The International Early Lung Cancer Action Program Investigators. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. N Engl J Med. 2006 Oct 26; 355 (17):1763–71. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1963. [ Google Scholar ]

- Holland P. Statistics and causal inference. J Am Stat Assoc. 1986; 81 :945–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eddy DM. A manual for assessing health practices and designing practice policies: the explicit approach. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, et al., editors. Cancer Medicine. 6th ed. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: BC Decker; 2003. (editors) [ Google Scholar ]

- National Academy of Sciences. Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation: BEIR VII. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 31 January 2022

The fundamentals of critically appraising an article

- Sneha Chotaliya 1

BDJ Student volume 29 , pages 12–13 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

1945 Accesses

Metrics details

Sneha Chotaliya

We are often surrounded by an abundance of research and articles, but the quality and validity can vary massively. Not everything will be of a good quality - or even valid. An important part of reading a paper is first assessing the paper. This is a key skill for all healthcare professionals as anything we read can impact or influence our practice. It is also important to stay up to date with the latest research and findings.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

We are sorry, but there is no personal subscription option available for your country.

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Chambers R, 'Clinical Effectiveness Made Easy', Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press , 1998

Loney P L, Chambers L W, Bennett K J, Roberts J G and Stratford P W. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can 1998; 19 : 170-176.

Brice R. CASP CHECKLISTS - CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . 2021. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (Accessed 22 July 2021).

White S, Halter M, Hassenkamp A and Mein G. 2021. Critical Appraisal Techniques for Healthcare Literature . St George's, University of London.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Academic Foundation Dentist, London, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sneha Chotaliya .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Chotaliya, S. The fundamentals of critically appraising an article. BDJ Student 29 , 12–13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-021-0275-6

Download citation

Published : 31 January 2022

Issue Date : 31 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-021-0275-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Systematic Reviews

- Critical Appraisal by Study Design

Systematic Reviews: Critical Appraisal by Study Design

- Knowledge Synthesis Comparison

- Knowledge Synthesis Decision Tree

- Standards & Reporting Results

- Mayo Clinic Library Manuals & Materials

- Training Resources

- Review Teams

- Develop & Refine Your Research Question

- Develop a Timeline

- Project Management

- Communication

- PRISMA-P Checklist

- Eligibility Criteria

- Register your Protocol

- Other Resources

- Other Screening Tools

- Grey Literature Searching

- Citation Searching

- Data Extraction Tools

- Minimize Bias

- Covidence for Quality Assessment

- Synthesis & Meta-Analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Tools for Critical Appraisal of Studies

“The purpose of critical appraisal is to determine the scientific merit of a research report and its applicability to clinical decision making.” 1 Conducting a critical appraisal of a study is imperative to any well executed evidence review, but the process can be time consuming and difficult. 2 The critical appraisal process requires “a methodological approach coupled with the right tools and skills to match these methods is essential for finding meaningful results.” 3 In short, it is a method of differentiating good research from bad research.

Critical Appraisal by Study Design (featured tools)

- Non-RCTs or Observational Studies

- Diagnostic Accuracy

- Animal Studies

- Qualitative Research

- Tool Repository

- AMSTAR 2 The original AMSTAR was developed to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews that included only randomized controlled trials. AMSTAR 2 was published in 2017 and allows researchers to “identify high quality systematic reviews, including those based on non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions.” 4 more... less... AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews)

- ROBIS ROBIS is a tool designed specifically to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews. “The tool is completed in three phases: (1) assess relevance(optional), (2) identify concerns with the review process, and (3) judge risk of bias in the review. Signaling questions are included to help assess specific concerns about potential biases with the review.” 5 more... less... ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews)

- BMJ Framework for Assessing Systematic Reviews This framework provides a checklist that is used to evaluate the quality of a systematic review.

- CASP Checklist for Systematic Reviews This CASP checklist is not a scoring system, but rather a method of appraising systematic reviews by considering: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What are the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools, Checklist for Systematic Reviews JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- RoB 2 RoB 2 “provides a framework for assessing the risk of bias in a single estimate of an intervention effect reported from a randomized trial,” rather than the entire trial. 6 more... less... RoB 2 (revised tool to assess Risk of Bias in randomized trials)

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of an RCT that require critical appraisal: 1. Is the basic study design valid for a randomized controlled trial? 2. Was the study methodologically sound? 3. What are the results? 4. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CONSORT Statement The CONSORT checklist includes 25 items to determine the quality of randomized controlled trials. “Critical appraisal of the quality of clinical trials is possible only if the design, conduct, and analysis of RCTs are thoroughly and accurately described in the report.” 7 more... less... CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- ROBINS-I ROBINS-I is a “tool for evaluating risk of bias in estimates of the comparative effectiveness… of interventions from studies that did not use randomization to allocate units… to comparison groups.” 8 more... less... ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions)

- NOS This tool is used primarily to evaluate and appraise case-control or cohort studies. more... less... NOS (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)

- AXIS Cross-sectional studies are frequently used as an evidence base for diagnostic testing, risk factors for disease, and prevalence studies. “The AXIS tool focuses mainly on the presented [study] methods and results.” 9 more... less... AXIS (Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools for Non-Randomized Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. • Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies • Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies • Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group • Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- Case Series Studies Quality Appraisal Checklist Developed by the Institute of Health Economics (Canada), the checklist is comprised of 20 questions to assess “the robustness of the evidence of uncontrolled, [case series] studies.” 10

- Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports In this paper, Dr. Murad and colleagues “present a framework for appraisal, synthesis and application of evidence derived from case reports and case series.” 11

- MINORS The MINORS instrument contains 12 items and was developed for evaluating the quality of observational or non-randomized studies. 12 This tool may be of particular interest to researchers who would like to critically appraise surgical studies. more... less... MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools for Non-Randomized Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. • Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies • Checklist for Case Control Studies • Checklist for Case Reports • Checklist for Case Series • Checklist for Cohort Studies

- QUADAS-2 The QUADAS-2 tool “is designed to assess the quality of primary diagnostic accuracy studies… [it] consists of 4 key domains that discuss patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow of patients through the study and timing of the index tests and reference standard.” 13 more... less... QUADAS-2 (a revised tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- STARD 2015 The authors of the standards note that “[e]ssential elements of [diagnostic accuracy] study methods are often poorly described and sometimes completely omitted, making both critical appraisal and replication difficult, if not impossible.”10 The Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies was developed “to help… improve completeness and transparency in reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies.” 14 more... less... STARD 2015 (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of diagnostic test studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Diagnostic Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SYRCLE’s RoB “[I]mplementation of [SYRCLE’s RoB tool] will facilitate and improve critical appraisal of evidence from animal studies. This may… enhance the efficiency of translating animal research into clinical practice and increase awareness of the necessity of improving the methodological quality of animal studies.” 15 more... less... SYRCLE’s RoB (SYstematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation’s Risk of Bias)

- ARRIVE 2.0 “The [ARRIVE 2.0] guidelines are a checklist of information to include in a manuscript to ensure that publications [on in vivo animal studies] contain enough information to add to the knowledge base.” 16 more... less... ARRIVE 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments)

- Critical Appraisal of Studies Using Laboratory Animal Models This article provides “an approach to critically appraising papers based on the results of laboratory animal experiments,” and discusses various “bias domains” in the literature that critical appraisal can identify. 17

- CEBM Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of qualitative research studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Tool Repository Created by librarians at Duke University, this extensive listing contains over 100 commonly used risk of bias tools that may be sorted by study type.

- Latitudes Network A library of risk of bias tools for use in evidence syntheses that provides selection help and training videos.

References & Recommended Reading

1. Kolaski, K., Logan, L. R., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2024). Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews . British Journal of Pharmacology , 181 (1), 180-210

2. Portney LG. Foundations of clinical research : applications to evidence-based practice. Fourth edition. ed. Philadelphia: F A Davis; 2020.

3. Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1991;302(6785):1136-1140.

4. Singh S. Critical appraisal skills programme. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 2013;4(1):76-77.

5. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;358:j4008.

6. Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JPT, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:225-234.

7. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2019;366:l4898.

8. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(8):e1-37.

9. Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;355:i4919.

10. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ open. 2016;6(12):e011458.

11. Guo B, Moga C, Harstall C, Schopflocher D. A principal component analysis is conducted for a case series quality appraisal checklist. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:199-207.e192.

12. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ evidence-based medicine. 2018;23(2):60-63.

13. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ journal of surgery. 2003;73(9):712-716.

14. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(8):529-536.

15. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;351:h5527.

16. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC medical research methodology. 2014;14:43.

17. Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS biology. 2020;18(7):e3000411.

18. O'Connor AM, Sargeant JM. Critical appraisal of studies using laboratory animal models. ILAR journal. 2014;55(3):405-417.

- << Previous: Minimize Bias

- Next: Covidence for Quality Assessment >>

- Last Updated: Mar 7, 2024 9:42 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mayo.edu/systematicreviewprocess

Understanding research and critical appraisal

- Introduction

- Secondary research

- Primary research

The need for critical appraisal

Critical appraisal checklists, critical appraisal for anti-racism.

- Useful terminology

- Further reading and helpful resources

Why critical appraisal?

As noted earlier, research studies can vary in methodological quality, and critical appraisal provides a means to consistently evaluate the validity, reliability and relevance of research results.

The purpose of critical appraisal is not to criticise a paper, but to appraise the methodology for any factors which could impact upon the findings. Below are some initial questions to ask of a paper when you set about reading it.

- What is the research question?

- Why was the research needed?

- What type of study design was used?

- Was the study design appropriate for answering the research question?

The answers to these questions will typically be found in the abstract, the introduction or the methods section of a paper, and should offer an initial sense of the study.

Critical appraisal will help to determine the validity of a study in two important ways. Internal validity relates to the reliability and accuracy of research results, effected by the appropriateness of the research methods used to address the research question, and the extent to which a study measures what it sets out to measure. E xternal validity relates to the extent to which research results are generalisable to populations beyond the study participants.

Participants

Depending on the study design used, there are various details relating to research participants that should be included in a paper. These might be, for example: how the participants were recruited, demographic and other relevant characteristics of the study participants, how participants were assigned to study groups, how many participants took part, and how many participants (if any) dropped out before the end of the study.

Confounding

Many research studies aim to establish an association between a treatment or exposure, and an outcome. A confounding factor is any factor which might influence the association of the two, either suggesting an association where none exists (or distorting the nature of the association), or masking a true association, and leading to incorrect conclusions. Confounding factors might include demographic characteristics of participants, such as age or gender, or lifestyle factors such as diet or exercise.

Researchers should take steps to identify potential confounding factors which might influence a study, and control these, either through the design of the study, or through statistical analysis of the research data.

There are various forms of bias which may be introduced into research at various points during a study, and effect the accuracy of the study findings. Researchers should be aware of any potential biases in relation to their study, and take steps to avoid these, and as readers, we should be also be aware of the relevant biases and the measures which might be taken to avoid or minimise their impact.

Below are some potential biases which can effect research findings, or the application of research evidence to practice. For a comprehensive list of biases, see the Catalogue of Bias website .

Selection bias is introduced when the participants in a study have some systematically different characteristic to those not under study. This bias can also be introduced if there is some systematic difference between participants in the treatment group, and those in the control group. When reading a paper, look for details on the number of participants screened and included, the randomisation procedure used (if applicable), baseline comparisons of study groups, and procedures for handling any missing data.

Observer bias is introduced when there are differences between the observations or assessments made by researchers and the true values of such observations. When a study is collecting subjective data, observer bias might occur owing to the beliefs, values or perspective of the researcher(s). When a study is collecting objective data, observer bias might occur owing to different practices in the interpretation or recording of data. Blinding of those researchers who are to assess outcomes can help, where applicable, as can researcher acknowledgement of the potential impact of their bias(es).

Attrition bias is introduced when those participants who drop out of a study differ in some systematic way from the participants who complete the study. Attrition bias can distort the findings of a study, leading to incorrect assumptions about the effect of a treatment, for example. When reading a paper, look for information on how participant data was analysed, and for information on the number of participants lost and their reasons for leaving the study.

Reporting bias is introduced when researchers selectively report - or suppress - relevant data or information from a study. Reporting bias might arise from researchers withholding relevant conflicts of interest, changing study outcomes to fit data, over-reporting potential benefits or under-reporting potential harms.

Publication bias is a form of reporting bias, which results from non-publication of research studies which produce either negative or insubstantial findings. The absence of this research data can lead to the distortion of the full body of evidence on a subject, where only positive findings are published. The registration and reporting of clinical trials in trial registries allows access to some of this data, but this is reliant on researchers complying with requirements. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses can also play a part in reducing the impact of publication bias, by going beyond published journal articles when collecting their data sources, and by employing appropriate statistical methods to assess for publication bias.

Two very commonly reported statistical calculations of the results of a trial are the p-value and the confidence interval (CI) .

The p-value indicates the probability of any given outcome arising through chance. A smaller p-value equates to a smaller likelihood of the outcome occurring by chance, and the conventional cut off point for a statistically significant p-value is 0.05 or less (equivalent to a probability of 1 in 20 or less).

The confidence interval is a statistical range within which the true effect or result of a study lies, and is a means for researchers to convey their confidence in their findings. The convention is to state the 95% confidence interval, which is the range within which true results would lie on 95% of occasions.

As research studies involve only sample populations, reporting the p-value and/or CI can help to statistically generalise the applicability of research findings from the study participants to the overall population. In both cases, however, it is important to note that a smaller study sample population offers less certainty in the ability to generalise findings.

Significance

A research study might produce findings which have statistical significance or clinical significant , or both. The p-value and/or CI reported in a study can help determine the statistical significance of results, while the clinical significance of a study relates to whether the findings translate to worthwhile or noticeable improvements for a real population.

It is important to bear in mind that findings which are not statistically significant may have clinical significance.

Further statistical measures of clinical effectiveness

For further information on common statistical terms and concepts you will encounter when appraising papers such as odds, odd ratios, risk, risk ratios and numbers needed to treat, you will find a number of helpful articles here:

AKT Statistics Topics – Dr Chris Cates' EBM Website (nntonline.net)

The below sites host checklists which can be used to help appraise the reliability and applicability of publications, ranging from peer-reviewed articles to grey literature

- Amstar systematic review checklist AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) can be used to assess the methodological quality of a systematic review and as a guide to performing a systematic review. Two agreements are required during quality assessment ensuring lower risk of bias. AMSTAR has guidelines explaining each outlined item

- CASP Appraisal Checklists This set of eight critical appraisal tools are designed to be used when reading research, these include tools for Systematic Reviews, Randomised Controlled Trials, Cohort Studies, Case Control Studies, Economic Evaluations, Diagnostic Studies, Qualitative studies and Clinical Prediction Rule.

- Critical Appraisal tools A series of critical appraisal worksheets for different types of research studies, from the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (CEBM) - including versions in multiple languages

- Critical Appraisal Tools Critical appraisal checklists for a broad range of research study types, from the Joanna Briggs Institute

- SIGN checklists These checklists were subjected to evaluation and adaptation to meet the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network's (SIGN’s) requirements for a balance between methodological rigour and practicality of use.

- Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) The MMAT is intended to be used as a checklist for concomitantly appraising and/or describing studies included in systematic mixed studies reviews (reviews including original qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies).

- AACODS grey literature checklist The AACODS checklist is a tool for evaluating the Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objective, Date and Significance of grey literature.

Traditional appraisal tools do not prompt appraisers to look into questions around racial under-representation in research and racial bias in interpretation of findings with regards to minoritised ethnic groups in medical research. In order to combat this, librarian and information specialist, Ramona Naicker , has developed a supplementary tool that can be used to address these issues.

Watch the video below for an outline of the issues and how the checklist can be used.

- << Previous: Primary research

- Next: Useful terminology >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 4:07 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sgul.ac.uk/researchdesign

- CASP Checklists

- How to use our CASP Checklists

- Referencing and Creative Commons

- Online Training Courses

- CASP Workshops

- What is Critical Appraisal

- Study Designs

- Useful Links

- Bibliography

- View all Tools and Resources

- Testimonials

- How to Critically Appraise a Research Paper

Research papers are a powerful means through which millions of researchers around the globe pass on knowledge about our world.

However, the quality of research can be highly variable. To avoid being misled, it is vital to perform critical appraisals of research studies to assess the validity, results and relevance of the published research. Critical appraisal skills are essential to be able to identify whether published research provides results that can be used as evidence to help improve your practice.

What is a critical appraisal?

Most of us know not to believe everything we read in the newspaper or on various media channels. But when it comes to research literature and journals, they must be critically appraised due to the nature of the context. In order for us to trust research papers, we want to be safe in the knowledge that they have been efficiently and professionally checked to confirm what they are saying. This is where a critical appraisal comes in.

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, value and relevance in a particular context. We have put together a more detailed page to explain what critical appraisal is to give you more information.

Why is a critical appraisal of research required?

Critical appraisal skills are important as they enable you to systematically and objectively assess the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers. When a research article is published, who wrote it should not be an indication of its trustworthiness and relevance.

What are the benefits of performing critical appraisals for research papers?

Performing a critical appraisal helps to:

- Reduce information overload by eliminating irrelevant or weak studies

- Identify the most relevant papers

- Distinguish evidence from opinion, assumptions, misreporting, and belief

- Assess the validity of the study

- Check the usefulness and clinical applicability of the study

How to critically appraise a research paper

There are some key questions to consider when critically appraising a paper. These include:

- Is the study relevant to my field of practice?

- What research question is being asked?

- Was the study design appropriate for the research question?

CASP has several checklists to help with performing a critical appraisal which we believe are crucial because:

- They help the user to undertake a complex task involving many steps

- They support the user in being systematic by ensuring that all important factors or considerations are taken into account

- They increase consistency in decision-making by providing a framework

In addition to our free checklists, CASP has developed a number of valuable online e-learning modules designed to increase your knowledge and confidence in conducting a critical appraisal.

Introduction To Critical Appraisal & CASP

This Module covers the following:

- Challenges using evidence to change practice

- 5 steps of evidence-based practice

- Developing critical appraisal skills

- Integrating and acting on the evidence

- The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)

- Online Learning

- Different Types of Bias in Research

- What is Qualitative Research?

- What is a Case-Control Study in Research?

- What Are Systematic Reviews? Why Are They Important?

- How to Critically Appraise a Medical Research Paper

- Critical Appraisal for the ISFE Dental Examinations

- What Is a Cohort Study & Why Are They Important?

- How to use the PICO Framework to Aid Critical Appraisal

- How to Critically Appraise a Randomised Controlled Trial

- Privacy Policy

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) will use the information you provide on this form to be in touch with you and to provide updates and marketing. Please let us know all the ways you would like to hear from us:

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here.

Copyright 2024 CASP UK - OAP Ltd. All rights reserved Website by Beyond Your Brand

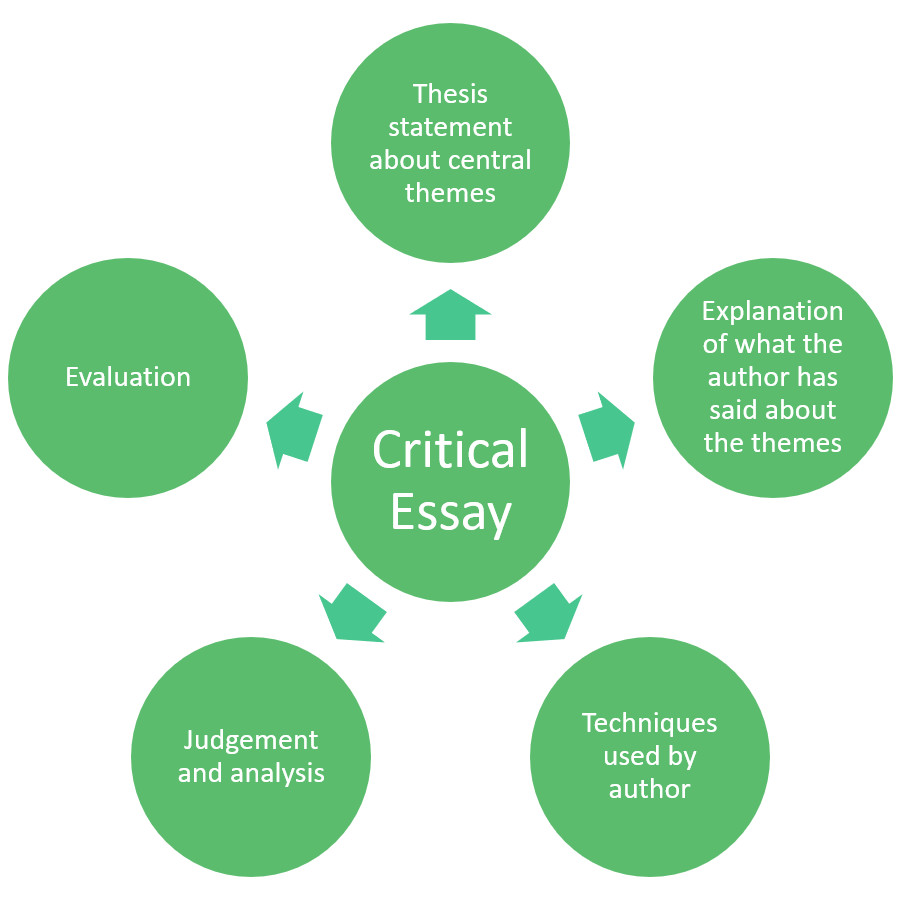

How To Write a Critical Appraisal

A critical appraisal is an academic approach that refers to the systematic identification of strengths and weakness of a research article with the intent of evaluating the usefulness and validity of the work’s research findings. As with all essays, you need to be clear, concise, and logical in your presentation of arguments, analysis, and evaluation. However, in a critical appraisal there are some specific sections which need to be considered which will form the main basis of your work.

Structure of a Critical Appraisal

Introduction.

Your introduction should introduce the work to be appraised, and how you intend to proceed. In other words, you set out how you will be assessing the article and the criteria you will use. Focusing your introduction on these areas will ensure that your readers understand your purpose and are interested to read on. It needs to be clear that you are undertaking a scientific and literary dissection and examination of the indicated work to assess its validity and credibility, expressed in an interesting and motivational way.

Body of the Work

The body of the work should be separated into clear paragraphs that cover each section of the work and sub-sections for each point that is being covered. In all paragraphs your perspectives should be backed up with hard evidence from credible sources (fully cited and referenced at the end), and not be expressed as an opinion or your own personal point of view. Remember this is a critical appraisal and not a presentation of negative parts of the work.

When appraising the introduction of the article, you should ask yourself whether the article answers the main question it poses. Alongside this look at the date of publication, generally you want works to be within the past 5 years, unless they are seminal works which have strongly influenced subsequent developments in the field. Identify whether the journal in which the article was published is peer reviewed and importantly whether a hypothesis has been presented. Be objective, concise, and coherent in your presentation of this information.

Once you have appraised the introduction you can move onto the methods (or the body of the text if the work is not of a scientific or experimental nature). To effectively appraise the methods, you need to examine whether the approaches used to draw conclusions (i.e., the methodology) is appropriate for the research question, or overall topic. If not, indicate why not, in your appraisal, with evidence to back up your reasoning. Examine the sample population (if there is one), or the data gathered and evaluate whether it is appropriate, sufficient, and viable, before considering the data collection methods and survey instruments used. Are they fit for purpose? Do they meet the needs of the paper? Again, your arguments should be backed up by strong, viable sources that have credible foundations and origins.

One of the most significant areas of appraisal is the results and conclusions presented by the authors of the work. In the case of the results, you need to identify whether there are facts and figures presented to confirm findings, assess whether any statistical tests used are viable, reliable, and appropriate to the work conducted. In addition, whether they have been clearly explained and introduced during the work. In regard to the results presented by the authors you need to present evidence that they have been unbiased and objective, and if not, present evidence of how they have been biased. In this section you should also dissect the results and identify whether any statistical significance reported is accurate and whether the results presented and discussed align with any tables or figures presented.

The final element of the body text is the appraisal of the discussion and conclusion sections. In this case there is a need to identify whether the authors have drawn realistic conclusions from their available data, whether they have identified any clear limitations to their work and whether the conclusions they have drawn are the same as those you would have done had you been presented with the findings.

The conclusion of the appraisal should not introduce any new information but should be a concise summing up of the key points identified in the body text. The conclusion should be a condensation (or precis) of all that you have already written. The aim is bringing together the whole paper and state an opinion (based on evaluated evidence) of how valid and reliable the paper being appraised can be considered to be in the subject area. In all cases, you should reference and cite all sources used. To help you achieve a first class critical appraisal we have put together some key phrases that can help lift you work above that of others.

Key Phrases for a Critical Appraisal

- Whilst the title might suggest

- The focus of the work appears to be…

- The author challenges the notion that…

- The author makes the claim that…

- The article makes a strong contribution through…

- The approach provides the opportunity to…

- The authors consider…

- The argument is not entirely convincing because…

- However, whilst it can be agreed that… it should also be noted that…

- Several crucial questions are left unanswered…

- It would have been more appropriate to have stated that…

- This framework extends and increases…

- The authors correctly conclude that…

- The authors efforts can be considered as…

- Less convincing is the generalisation that…

- This appears to mislead readers indicating that…

- This research proves to be timely and particularly significant in the light of…

You may also like

- Teesside University Student & Library Services

- Learning Hub Group

Critical Appraisal for Health Students

- Critical Appraisal of a qualitative paper

- Critical Appraisal: Help

- Critical Appraisal of a quantitative paper

- Useful resources

Appraisal of a Qualitative paper : Top tips

- Introduction

Critical appraisal of a qualitative paper

This guide aimed at health students, provides basic level support for appraising qualitative research papers. It's designed for students who have already attended lectures on critical appraisal. One framework for appraising qualitative research (based on 4 aspects of trustworthiness) is provided and there is an opportunity to practise the technique on a sample article.

Support Materials

- Framework for reading qualitative papers

- Critical appraisal of a qualitative paper PowerPoint

To practise following this framework for critically appraising a qualitative article, please look at the following article:

Schellekens, M.P.J. et al (2016) 'A qualitative study on mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer patients: how women experience participating with fellow patients', Support Care Cancer , 24(4), pp. 1813-1820.

Critical appraisal of a qualitative paper: practical example.

- Credibility

- Transferability

- Dependability

- Confirmability

How to use this practical example

Using the framework, you can have a go at appraising a qualitative paper - we are going to look at the following article:

Step 1. take a quick look at the article, step 2. click on the credibility tab above - there are questions to help you appraise the trustworthiness of the article, read the questions and look for the answers in the article. , step 3. click on each question and our answers will appear., step 4. repeat with the other aspects of trustworthiness: transferability, dependability and confirmability ., questioning the credibility:, who is the researcher what has been their experience how well do they know this research area, was the best method chosen what method did they use was there any justification was the method scrutinised by peers is it a recognisable method was there triangulation ( more than one method used), how was the data collected was data collected from the participants at more than one time point how long were the interviews were questions asked to the participants in different ways, is the research reporting what the participants actually said were the participants shown transcripts / notes of the interviews / observations to ‘check’ for accuracy are direct quotes used from a variety of participants, how would you rate the overall credibility, questioning the transferability, was a meaningful sample obtained how many people were included is the sample diverse how were they selected, are the demographics given, does the research cover diverse viewpoints do the results include negative cases was data saturation reached, what is the overall transferability can the research be transferred to other settings , questioning the dependability :, how transparent is the audit trail can you follow the research steps are the decisions made transparent is the whole process explained in enough detail did the researcher keep a field diary is there a clear limitations section, was there peer scrutiny of the researchwas the research plan shown to peers / colleagues for approval and/or feedback did two or more researchers independently judge data, how would you rate the overall dependability would the results be similar if the study was repeated how consistent are the data and findings, questioning the confirmability :, is the process of analysis described in detail is a method of analysis named or described is there sufficient detail, have any checks taken place was there cross-checking of themes was there a team of researchers, has the researcher reflected on possible bias is there a reflexive diary, giving a detailed log of thoughts, ideas and assumptions, how do you rate the overall confirmability has the researcher attempted to limit bias, questioning the overall trustworthiness :, overall how trustworthy is the research, further information.

See Useful resources for links, books and LibGuides to help with Critical appraisal.

- << Previous: Critical Appraisal: Help

- Next: Critical Appraisal of a quantitative paper >>

- Last Updated: Aug 25, 2023 2:48 PM

- URL: https://libguides.tees.ac.uk/critical_appraisal

Medicine: A Brief Guide to Critical Appraisal

- Quick Start

- First Year Library Essentials

- Literature Reviews and Data Management

- Advanced Search Health This link opens in a new window

- Guide to Using EndNote This link opens in a new window

- A Brief Guide to Critical Appraisal

- Manage Research Data This link opens in a new window

- Articles & Databases

- Anatomy & Radiology

- Medicines Information

- Diagnostic Tests & Calculators

- Health Statistics

- Multimedia Sources

- News & Public Opinion

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Guide This link opens in a new window

- Medical Ethics Guide This link opens in a new window

Have you ever seen a news piece about a scientific breakthrough and wondered how accurate the reporting is? Or wondered about the research behind the headlines? This is the beginning of critical appraisal: thinking critically about what you see and hear, and asking questions to determine how much of a 'breakthrough' something really is.

The article " Is this study legit? 5 questions to ask when reading news stories of medical research " is a succinct introduction to the sorts of questions you should ask in these situations, but there's more than that when it comes to critical appraisal. Read on to learn more about this practical and crucial aspect of evidence-based practice.

What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical appraisal forms part of the process of evidence-based practice. “ Evidence-based practice across the health professions ” outlines the fives steps of this process. Critical appraisal is step three:

- Ask a question

- Access the information

- Appraise the articles found

- Apply the information

Critical appraisal is the examination of evidence to determine applicability to clinical practice. It considers (1) :

- Are the results of the study believable?

- Was the study methodologically sound?

- What is the clinical importance of the study’s results?

- Are the findings sufficiently important? That is, are they practice-changing?

- Are the results of the study applicable to your patient?

- Is your patient comparable to the population in the study?

Why Critically Appraise?

If practitioners hope to ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’, practicing in a manner that is responsive to the discoveries of the research community, then it makes sense for the responsible, critically thinking practitioner to consider the reliability, influence, and relevance of the evidence presented to them.

While critical thinking is valuable, it is also important to avoid treading too much into cynicism; in the words of Hoffman et al. (1):

… keep in mind that no research is perfect and that it is important not to be overly critical of research articles. An article just needs to be good enough to assist you to make a clinical decision.

How do I Critically Appraise?

Evidence-based practice is intended to be practical . To enable this, critical appraisal checklists have been developed to guide practitioners through the process in an efficient yet comprehensive manner.

Critical appraisal checklists guide the reader through the appraisal process by prompting the reader to ask certain questions of the paper they are appraising. There are many different critical appraisal checklists but the best apply certain questions based on what type of study the paper is describing. This allows for a more nuanced and appropriate appraisal. Wherever possible, choose the appraisal tool that best fits the study you are appraising.

Like many things in life, repetition builds confidence and the more you apply critical appraisal tools (like checklists) to the literature the more the process will become second nature for you and the more effective you will be.

How do I Identify Study Types?

Identifying the study type described in the paper is sometimes a harder job than it should be. Helpful papers spell out the study type in the title or abstract, but not all papers are helpful in this way. As such, the critical appraiser may need to do a little work to identify what type of study they are about to critique. Again, experience builds confidence but having an understanding of the typical features of common study types certainly helps.

To assist with this, the Library has produced a guide to study designs in health research .

The following selected references will help also with understanding study types but there are also other resources in the Library’s collection and freely available online:

- The “ How to read a paper ” article series from The BMJ is a well-known source for establishing an understanding of the features of different study types; this series was subsequently adapted into a book (“ How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine ”) which offers more depth and currency than that found in the articles. (2)

- Chapter two of “ Evidence-based practice across the health professions ” briefly outlines some study types and their application; subsequent chapters go into more detail about different study types depending on what type of question they are exploring (intervention, diagnosis, prognosis, qualitative) along with systematic reviews.

- “ Clinical evidence made easy ” contains several chapters on different study designs and also includes critical appraisal tools. (3)

- “ Translational research and clinical practice: basic tools for medical decision making and self-learning ” unpacks the components of a paper, explaining their purpose along with key features of different study designs. (4)

- The BMJ website contains the contents of the fourth edition of the book “ Epidemiology for the uninitiated ”. This eBook contains chapters exploring ecological studies, longitudinal studies, case-control and cross-sectional studies, and experimental studies.

Reporting Guidelines

In order to encourage consistency and quality, authors of reports on research should follow reporting guidelines when writing their papers. The EQUATOR Network is a good source of reporting guidelines for the main study types.

While these guidelines aren't critical appraisal tools as such, they can assist by prompting you to consider whether the reporting of the research is missing important elements.

Once you've identified the study type at hand, visit EQUATOR to find the associated reporting guidelines and ask yourself: does this paper meet the guideline for its study type?

Which Checklist Should I Use?

Determining which checklist to use ultimately comes down to finding an appraisal tool that:

- Fits best with the study you are appraising

- Is reliable, well-known or otherwise validated

- You understand and are comfortable using

Below are some sources of critical appraisal tools. These have been selected as they are known to be widely accepted, easily applicable, and relevant to appraisal of a typical journal article. You may find another tool that you prefer, which is acceptable as long as it is defensible:

- CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute)

- CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network)

- STROBE (Strengthing the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)

- BMJ Best Practice

The information on this page has been compiled by the Medical Librarian. Please contact the Library's Health Team ( [email protected] ) for further assistance.

Reference list

1. Hoffmann T, Bennett S, Del Mar C. Evidence-based practice across the health professions. 2nd ed. Chatswood, N.S.W., Australia: Elsevier Churchill Livingston; 2013.

2. Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper : the basics of evidence-based medicine. 5th ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley; 2014.

3. Harris M, Jackson D, Taylor G. Clinical evidence made easy. Oxfordshire, England: Scion Publishing; 2014.

4. Aronoff SC. Translational research and clinical practice: basic tools for medical decision making and self-learning. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- << Previous: Guide to Using EndNote

- Next: Manage Research Data >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 4:53 PM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/medicine

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Critical Appraisal: The I-ELCAP Study. In its October 26, 2006, issue, the New England Journal of Medicine published the results of the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP) study, a large clinical research study examining annual computed tomography (CT) screening for lung cancer in asymptomatic persons. Though the authors concluded that the screening program could save ...

Critical appraisal of a journal article 1. Introduction to critical appraisal Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in a particular context. (Burls 2009) Critical appraisal is an important element of evidence-based medicine.

Critical appraisal is the assessment of research studies' worth to clinical practice. Critical appraisal—the heart of evidence-based practice—involves four phases: rapid critical appraisal, evaluation, synthesis, and recommendation. This article reviews each phase and provides examples, tips, and caveats to help evidence appraisers ...

What is critical appraisal? Critical appraisal involves a careful and systematic assessment of a study's trustworthiness or rigour (Booth et al., Citation 2016).A well-conducted critical appraisal: (a) is an explicit systematic, rather than an implicit haphazard, process; (b) involves judging a study on its methodological, ethical, and theoretical quality, and (c) is enhanced by a reviewer ...

Abstract. Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The ...

Here are some of the tools and basic considerations you might find useful when critically appraising an article. In a nutshell when appraising an article, you are assessing: 1. Its relevance ...

Several tools have been developed for the critical appraisal of scientific literature, including grading of evidence to help clinicians in the pursuit of EBM in a systematic manner. In this review, we discuss the broad framework for the critical appraisal of a clinical research paper, along with some of the relevant guidelines and recommendations.

"The purpose of critical appraisal is to determine the scientific merit of a research report and its applicability to clinical decision making." 1 Conducting a critical appraisal of a study is imperative to any well executed evidence review, but the process can be time consuming and difficult. 2 The critical appraisal process requires "a methodological approach coupled with the right ...

This guide, aimed at health students, provides basic level support for appraising quantitative research papers. It's designed for students who have already attended lectures on critical appraisal. One framework for appraising quantitative research (based on reliability, internal and external validity) is provided and there is an opportunity to ...

As noted earlier, research studies can vary in methodological quality, and critical appraisal provides a means to consistently evaluate the validity, reliability and relevance of research results. The purpose of critical appraisal is not to criticise a paper, but to appraise the methodology for any factors which could impact upon the findings.

The steps involved in a sound critical appraisal include: (a) identifying the study type (s) of the individual paper (s), (b) identifying appropriate criteria and checklist (s), (c) selecting an ...

Abstract. Background: Critical appraisal of research paper is a fundamental skill in modern medical practice, which is skills-set and developed throughout the professional career. The professional ...

This is where a critical appraisal comes in. Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, value and relevance in a particular context. We have put together a more detailed page to explain what critical appraisal is to give you more information.

Written by Emma Taylor. A critical appraisal is an academic approach that refers to the systematic identification of strengths and weakness of a research article with the intent of evaluating the usefulness and validity of the work's research findings. As with all essays, you need to be clear, concise, and logical in your presentation of ...

Critical appraisal of a qualitative paper. This guide aimed at health students, provides basic level support for appraising qualitative research papers. It's designed for students who have already attended lectures on critical appraisal. ... is provided and there is an opportunity to practise the technique on a sample article. Support Materials.

1. Introduction to critical appraisal. Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in a particular context. (Burls 2009) Critical appraisal is an important element of evidence-based medicine. The five steps of evidence-based medicine are:

The validity of research papers is based on the research methodology and the risk of bias that comes from the methodology. It does not come from the results. They should appraise the article that is most likely to guide clinical care. 6. Critical Appraisal a. First and foremost, an appraisal is not an attack on the authors of the appraised ...

Critical appraisal forms part of the process of evidence-based practice. " Evidence-based practice across the health professions " outlines the fives steps of this process. Critical appraisal is step three: Critical appraisal is the examination of evidence to determine applicability to clinical practice. It considers (1):

Critical appraisal is the process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance to inform clinical decision-making. All components of a clinical ...