The People, Ideas, and Things Journal

How Capitalism is a Driving Force of Climate Change

Global economic growth leads to the increased consumption of natural resources, pollution, and loss of biodiversity and simultaneously widens the income gap between the wealthy and the poor. Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 provides a fictional glimpse of the world 120 years in the future, examining the severe environmental changes that have taken place and how people of upper and lower economic classes are unevenly impacted by these changes. The experiences of the fictional characters reflect real issues that future generations will experience as irreversible changes to our climate are made.

“We’ve been paying a fraction of what things really cost to make, but meanwhile the planet, and the workers who make the stuff, take the unpaid costs right in the teeth” (Robinson 4). Modern economic growth and demand for goods require rapid production at low costs, leading to the inevitable exploitation of nature and workers. Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 explores the world one hundred and twenty years into the future, where the drastic continuation of climate change has resulted in a 50-foot rise in the global sea level, destroying coastal cities worldwide. Each section of the novel is broken into 8 parts, seen through the eyes of 10 different characters living in New York City in the year 2140. The characters hold various roles in society, ranging from political leaders to investors to orphaned children. Each of the characters’ lives intertwine, showing their daily interactions amid a changed and chaotic world. Robinson depicts what everyday life would look like for New Yorkers, and the rest of the world, if no significant measures are taken to prevent climate change and environmental destruction. The novel highlights the income inequalities that both drive climate change and influence how people survive those changes. This paper examines two important narratives in New York 2140 to argue that climate change is driven by capitalism, which in turn changes how people experience climate change.

Global capitalism and economic expansion are driving forces for both income inequality and climate change. The global economy within New York 2140 reflects the same systems in place today, with the existence of global capitalism driving production and consumption. Most climate scientists have come to agree that the cause of climate change is the increased emission of greenhouse gases, specifically carbon dioxide, which have increased rapidly since the Industrial Revolution (Baer 2). Progressive scholars recognize the serious damage that results from a global capitalist drive. Endless efforts of private owners to expand and increase their profits force a “perpetual treadmill of production and consumption” relying mainly on fossil fuels or alternative sources of greenhouse gas emissions (Baer 4). In 2010, the International Energy Agency projected that by 2030, global energy use would rise over 50%, with fossil fuels still the primary source of energy (Baer 64). Our continued dependence on the fossil fuel industry will continue to raise global temperatures as a direct result of global capitalism. The most profitable decisions will never be the most environmentally friendly, thus private owners of corporations will refrain from making environmentally conscious decisions without regulations.

In the United States, although the median household income reached a high in 2018, the gap between the poorest and wealthiest households is the biggest it has been in 50 years, potentially due to tax policies and declining labor unions (Chappell). This disparity continues to widen even among 10 years of Gross Domestic Product growth and low unemployment rates, reflecting a “significantly higher” income gap in 2018 than 2017 (Chappell). These statistics present a serious concern that economic expansion will be unable to decrease inequality between American households, an idea which is also reflected in New York 2140 through the characters Franklin, Stephan, and Roberto. In order to mitigate the impacts of climate change, it is important to understand that “the commitment to free-market policies only generates a combination of positive economic growth, increasing emissions and increasing inequality.” In other words, to decrease inequality in combination with continued economic growth would require policymaking that reforms carbon tax as well as prices carbon efficiently (Liobikienė and Rimkuvienė). The difference in ways that wealthy and impoverished people experience climate change is an important topic that will become increasingly relevant as we continue to see global temperatures rise.

In the novel, the author evaluates several perspectives from which individuals experience climate change. One of the many perspectives analyzed by Robinson is shown through the eyes of Franklin Garr. Franklin’s chapters are narratives from the first-person point of view describing his career success and personal life. He works for a large and profitable hedge fund called WaterPrice, which tracks global sea-level rise in relation to the stock market. A large accomplishment for Franklin was his creation of the IPPI index, (the Intertidal Property Pricing Index) a combination of a housing index with sea-level changes, tracking inflation rates and pricing for intertidal properties, despite being unable to predict if the sea level will remain stable in the future. Franklin lives in the MetLife building, a skyscraper connecting his life to several other characters from the novel. His entire career and industry benefit from making bets based on the rise and fall of sea level, showing that large companies and investors still live profitable and successful lifestyles even after drastic changes to global environments occur, continuing to worry only about their individual assets.

In our modern reality, the individuals in the top 10% of incomes are credited with over 36% of greenhouse gas emissions, while people that fall in the bottom 50% are only responsible for 15% of emissions (Liobikienė and Rimkuvienė). This displays a pattern that while wealthier people, like Franklin, are more at fault for the rise in global temperatures, they tend to be unaffected or even experience benefits from environmental damage. A changing climate is only seen by Franklin as something that is affecting the economy, not the source of mass extinction, food scarcity, and displacement of millions of people worldwide. He explains that destruction of coastlines and homes have opened the door for new investment opportunities, stating “Am I saying that the floods, the worst catastrophe in human history, equivalent or greater to the twentieth century’s wars in their devastation, were actually good for capitalism? Yes, I am” (Robinson 118). Climate destruction is brought about by economic expansion but then adds to the profitability of wealthy people by making their investments more lucrative and their property scarce, and thus more valuable.

On the other hand, people in poverty experience negative impacts at the hands of climate change. An alternate point of view reflected by the novel are the chapters written in the third-person point-of-view of two twelve-year-old orphans, Stephan and Roberto. These boys occupy most of their time by searching for sunken treasures in the canals and scavenging for diving tools. Neither of them knew how to read at the beginning of the story, since they were not enrolled in school, and later begin to learn from their elderly friend, Mr. Hexter. Stephan and Roberto also do not have legal status in the United States or birth certificates, so they become wards of the MetLife building to gain protection. While the fictional aspect of the novel entails the boys finding a large amount of gold after searching for treasure in the canal, their story can be looked at more realistically to analyze what would happen to two children without parents or homes in the event of a natural disaster, in this case, a devastating flood. Studies show that individuals in poverty are more likely to be harmed by climate stressors. As reflected in the novel, this harm is expected because individuals in poverty lack the financial resources to help them recover from natural disasters, such as floods and hurricanes, which become more common as global temperatures rise (Leichenko and Silva). At the time of the third flood, the boys were downtown in the Bronx and got stuck since the waters were rising too fast for them to get back uptown to safety. The two were forced to wait out the storm downtown and were not heard from for several days, with no access to phones to call for help or food to eat. This demonstrates what happened to thousands of individuals living in the poorer downtown districts, which are at a lower elevation and thus more susceptible to flooding, who became trapped. In addition to their lack of resources, poorer individuals also tend to work in job fields that depend on a consistent climate. For example, they may rely on jobs in agriculture, forestry, or fishing, which are all industries that are harmed by environmental damage, multiplying the discrepancies between how individuals on opposing ends of the income spectrum experience climate change (Leichenko and Silva).

New York 2140 presents these two differing perspectives between a hedge fund manager and two orphans and how they are impacted by climate change, making a larger commentary on how income disparity presents itself in our changing world. In the novel, wealthy New Yorkers are seen living uptown in large skyscrapers with extravagant lifestyles little impacted by mass flooding“ and—in some circumstances—even experiencing benefits. A sharp juxtaposition is seen downtown, which is half-submerged due to the rise in sea levels, where individuals in poverty suffer from displacement due to global changes. Working for WaterPrice has brought Franklin financial success and he lives a prosperous and classy lifestyle. He owns his own boat and eats out at rooftop restaurants and waterfront bars. On the other hand, Stephan and Roberto lack access to resources to help them escape the flooding and end up stranded downtown for days. In the novel, human life perseveres but the gap between the haves and have-nots continues to grow, as the wealthy have enough resources to be unaffected by the destruction of the environment or play the system to their advantage, while the poor struggle to stay afloat—literally—in a flooded world.

Towards the end of the novel, New York is hit by a third wave of flooding destroying the homes of thousands of people. After the flood, a character named Charlotte, who works as a social worker for the Householder’s Union, begs the mayor to allow the thousands of people who were living downtown to be offered refuge in the uptown towers, which are owned by wealthy individuals. She claims that “more than half the apartments uptown are empty because they’re owned by rich people from somewhere else” (Robinson 500). This exchange furthers the point that the poorer citizens are unable to afford the proper housing that would keep them safe from the floods, while the wealthier citizens can afford to own multiple homes in areas that remain safe from rising sea levels. This is comparative to modern society from a global perspective, where the level of pollution in high-income countries is 33.9 times higher than in low-income countries, leading researchers to believe that as more countries become developed, the negative impacts on the environment will continue to increase (Liobikienė and Rimkuvienė). Continued rising global temperatures and sea levels will expand the gap between the haves and have-nots as the homes of people who only can afford dangerous low-elevation areas are destroyed, making them homeless.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 uses multiple perspectives to evaluate the different ways that climate change will affect individuals on opposite ends of the income gap. Global capitalist economies are a root cause for increased greenhouse gas emissions, leading to rising global temperatures and sea levels, as seen within the fictional novel 120 years into the future. The characters Franklin, Stephan, and Roberto show how wealthier individuals are less likely to experience a serious impact from climate change while poorer individuals, responsible for less fossil fuel usage, are likely to experience serious changes. The ideas presented within the novel draw attention to real world issues and provide a sense of urgency for regulatory measures to be taken to limit fossil fuel usage. It is crucial to focus political and social efforts toward slowing climate change before human activity causes irreversible damage. Economic decisions should be made while taking future generations into consideration and supporting a level of economic growth that will be sustainable.

Baer, Hans A. Global Capitalism and Climate Change: The Need for an Alternative World System. AltaMira Press, 2012.

Chappell, Bill. “U.S. Income Inequality Worsens, Widening To A New Gap.” NPR.Org, https://www.npr.org/2019/09/26/764654623/u-s-income-inequality-worsens-w…. Accessed 4 Nov. 2020

Leichenko, Robin, and Julie A. Silva. “Climate Change and Poverty: Vulnerability, Impacts, and Alleviation Strategies: Climate Change and Poverty.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, vol. 5, no. 4, July 2014, pp. 539–56. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1002/wcc.287.

Liobikienė, Genovaitė, and Daiva Rimkuvienė. “The Role of Income Inequality on Consumption-Based Greenhouse Gas Emissions under Different Stages of Economic Development.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 27, no. 34, Dec. 2020, pp. 43067–76. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/s11356-020-10244-x.

Robinson, Kim Stanley. New York 2140. Orbit, 2017.

Lauren Pollock

My name is Lauren Pollock, and I am a freshman from Greensboro, North Carolina. I am currently undecided on my major, but I am interested in sustainability and health science.

Tags: capitalism climate change

Recent Posts

- Next story Public Opinion on the Phrase and Organization “Black Lives Matter” Nationally and in North Carolina

- Previous story Why We’re Not Happy: Analysis of “Beautiful Now”

The Mental Health Gap: Addressing Racial Disparities in Mental Health Care at Predominantly White Universities

A color-tural experience: the role of color in the emperor’s new groove, malaria: difficulties contributing to eradication efforts within central africa, navigating navigation: assessing the relationship between airline elasticities and price setting, milk to mylk: the growing popularity of plant-based milk alternatives.

art athletics biology climate college community culture disease economics education elections food football gaming gender genetics health history HIV law literature media medicine music North Carolina nutrition philosophy poetry policy politics psychology public health regulation religion rhetoric sex sexuality social society sports statistics students technology urban violence

Morning Edition

Listen live.

BBC Newshour

In-depth analysis and commentary on today's biggest news stories as only the BBC can deliver. BBC "Newshour" covers everything from the growth of democracy to the threat of terrorism with a fresh, clear perspective from across the globe.

- Environment

- International

Can capitalism save the planet from a climate crisis?

Many would say capitalism is what drove the climate crisis, and that a solution would depend on a different economic model that prioritizes sustainability and equity..

- Susan Phillips

Wind turbines work in Livermore, Calif., Wednesday, Aug. 10, 2022. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

Related Content

Philadelphians envision a ‘fossil fuel-free’ refinery redo at community summit

The company redeveloping the former PES refinery site has promised a “green, sustainable” project, but residents want more specific commitments.

12 months ago

A changing climate is contributing to longer wildfire seasons in New Jersey, experts say

Officials say that 99% of wildfires are caused by humans.

The majority of these start-ups will fail. But Stein says, that’s OK by him as long as the research can be used by someone else.

After so much cheerleading on the climate tech front, I met someone who had a slightly different view.

Yosef Abramowitz calls himself Israel’s “climate pioneer.” He helped bring solar power to the country by creating Arava Power in 2006. He is now the CEO of Energiya Global , which develops solar projects in Africa.

“It would be great to have new technologies that can especially help us store energy and deliver it to the neediest people as cheaply as possible,” Abramowitz said. “But baby, we just have to execute and implement and build, build, build. That’s the solution.”

Abramowitz says the majority of climate investment should go toward things we have already developed — solar, wind, and geothermal.

He worries that the focus on tech solutions could leave behind the people who contribute least to climate change yet have the most to lose.

“The poorer the community the less likely the titans of investing and tech are likely to go,” Abramowitz said.

Abramowitz says unfettered capitalism got us here. The problem, he says, is that fossil fuels are and continue to be subsidized. The International Monetary Fund reports those subsidies amounted to $5.9 trillion in 2020. Capitalism is fine, he says, but it needs guardrails and government incentives to push greener solutions forward.

“We have to save the planet today. That also takes some greed. And we bless that greed.”

But Abramowitz says you can get more climate bang for your buck while also doing anti-poverty work.

“We just plugged in a field in Burundi, the poorest country on the planet, to provide 10% of the country’s power. If we can do it there, we can do it anywhere. South Sudan is next. You know, what’s the excuse?”

Using funds distributed through the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, Abramowitz secured $10 million to finance the first solar project in Burundi. It’s set to go online May 9.

But when it comes to the climate tech start-ups, Africa will likely not be the next stop — the Israeli entrepreneurs are looking to the U.S. to sell their high-tech climate solutions.

Reporting for this story was made possible in part by the Jerusalem Press Club.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

The free WHYY News Daily newsletter delivers the most important local stories to your inbox.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Part of the series

Whyy news climate desk, you may also like.

New Jersey to fund research on offshore wind impacts on whales

The new funding will help researchers evaluate the impact of offshore wind activities on whales, birds and the marine ecosystem.

2 weeks ago

Atlantic City is one of the most flood-vulnerable coastal cities, report finds

A new study published in Nature measures whether land across 32 U.S. coastline cities is sinking or rising, and combines it with sea-level projections.

4 weeks ago

An artist who grew up on the streets of Philadelphia returns with an ‘optimistic’ climate exhibit

Artist Stephen Talasnik’s bamboo sculpture tells the story of melting glaciers.

2 months ago

About Susan Phillips

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

Insight and inspiration in turbulent times.

- All Latest Articles

- Environment

- Food & Water

- Featured Topics

- Get Started

- Online Course

- Holding the Fire

- What Could Possibly Go Right?

- About Resilience

- Fundamentals

- Submission Guidelines

- Commenting Guidelines

Solving the Climate Crisis Requires the End of Capitalism

By Jeremy Lent , originally published by Patterns of Meaning

October 13, 2021

It’s time to face the fact that resolving the climate crisis will require a fundamental shift away from our growth-based, corporate-dominated global system.

Originally published October 9, 2021 in Salon

The global conversation regarding climate change has, for the most part, ignored the elephant in the room. That’s strange, because this particular elephant is so large, obvious, and all-encompassing that politicians and executives must contort themselves to avoid naming it publicly. That elephant is called capitalism, and it is high time to face the fact that, as long as capitalism remains the dominant economic system of our globalized world, the climate crisis won’t be resolved.

As the crucial UN climate talks known as COP26 approach in early November, the public is becoming increasingly aware that the stakes have never been higher. What were once ominous warnings of future climate shocks wrought by wildfires, floods, and droughts have now become a staple of the daily news. Yet governments are failing to meet their own emissions pledges from the Paris agreement six years ago, which were themselves acknowledged to be inadequate. Increasingly, respected Earth scientists are warning, not just about the devastating effects of climate breakdown on our daily lives, but about the potential collapse of civilization itself unless we drastically change direction.

The elephant in the room

And yet, even as humanity faces perhaps the greatest existential crisis in its species’ history, the public debate on climate barely mentions the underlying economic system that brought us to this point and which continues to drive us toward the precipice. Ever since its emergence in the seventeenth century, with the creation of the first limited liability shareholder-owned corporations, capitalism has been premised on viewing the planet as a resource to exploit — its overriding objective to maximize profits from that exploitation as rapidly and extensively as possible. Current mainstream strategies to resolve our twin crises of climate breakdown and ecological overshoot without changing the underlying system of growth-based global capitalism are structurally inadequate.

The idea of “green growth” is promulgated by many development consultants, and is even incorporated in the UN’s official plan for “sustainable development,” but has been shown to be an illusion . Ecomodernists, and others who stand to profit from growth in the short-term, frequently make the argument that, through technological innovation, aggregate global economic output can become “absolutely decoupled” from resource use and carbon emissions — permitting limitless growth on a finite planet. Careful rigorous analysis , though, shows that this hasn’t happened so far, and even the most wildly aggressive assumptions for greater efficiency would still lead to unsustainable consumption of global resources.

The primary reason for this derives ultimately from the nature of capitalism itself. Under capitalism — which has now become the default global economic context for virtually all human enterprise — efficiency improvements intended to reduce resource usage inevitably become launchpads for further exploitation, leading paradoxically to an increase, rather than decrease, in consumption.

This dynamic, known as the Jevons paradox, was first recognized back in the nineteenth century by economist William Stanley Jevons, who demonstrated how James Watts’ steam engine, which greatly improved the efficiency of coal-powered engines, paradoxically caused a dramatic increase in coal consumption even while it decreased the amount of coal required for any particular application. The Jevons paradox has since been shown to be true in an endless variety of domains, from the invention in the nineteenth century of the cotton gin which led to an increase rather than decrease in the practice of slavery in the American South, to improved automobile fuel efficiency which encourages people to drive longer distances .

When the Jevons paradox is generalized to the global marketplace, we begin to see that it’s not really a paradox at all, but rather an inbuilt defining characteristic of capitalism. Shareholder-owned corporations, as the primary agents of global capitalism, are legally structured by the overarching imperative to maximize shareholder returns above all else. Although they are given the legal rights of “personhood” in many jurisdictions, if they were actually humans they would be diagnosed as psychopaths , ruthlessly pursuing their goal without regard to any collateral damage they might cause. Of the hundred largest economies today, sixty-nine are transnational corporations , which collectively represent a relentless force with one overriding objective : to turn humanity and the rest of life into fodder for endlessly increasing profit at the fastest possible rate.

Under global capitalism, this dynamic holds true even without the involvement of transnational corporations. Take bitcoin as an example. Originally designed after the global financial meltdown of 2008 to wrest monetary power from the domination of central banks, it relies on building trust through “mining,” a process that allows anyone to verify a transaction by solving increasingly complex mathematical equations and earn new bitcoins as compensation. A great idea — in theory. In practice, the unfettered marketplace for bitcoin mining has led to frenzied competition to solve ever more complex equations, with vast warehouses holding “rigs” of advanced computers consuming massive amounts of electricity, with the result that the carbon emissions from bitcoin processing are now equivalent to that of a mid-size country such as Sweden or Argentina.

An economy based on perpetual growth

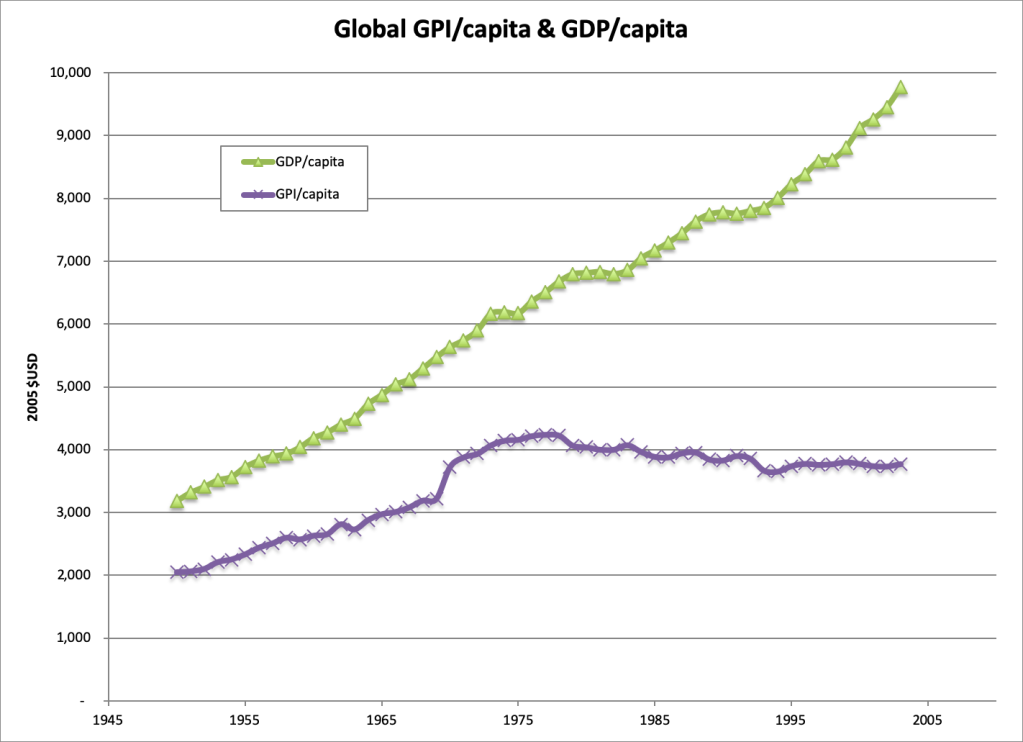

The relentless pursuit of profit growth above all other considerations is reflected in the world’s stock markets, where corporations are valued not by their benefit to society, but by investors’ expectations of their growth in future earnings. Similarly, when aggregated to national accounts, the main proxy used to measure the performance of politicians is growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Although it is commonly assumed that GDP correlates with social welfare, this is not the case once basic material requirements have been met. GDP merely measures the rate at which society transforms nature and human activity into the monetary economy, regardless of the ensuing quality of life. Anything that causes economic activity of any kind, whether good or bad, adds to GDP. When researchers developed a benchmark called the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), which incorporates qualitative components of well-being, they discovered a dramatic divergence between the two measures. GPI peaked in 1978 and has been steadily falling ever since, even while GDP continues to accelerate.

Since 1978, Genuine Progress has been falling even while GDP continues to increase. Credit: Kubiszewski et al., Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress

In spite of this, the possibility of shifting our economy away from perpetual growth is barely even considered in mainstream discourse. In preparation for COP26, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) modeled five scenarios exploring potential pathways that would lead to different global heating outcomes this century, ranging from an optimistic 1.5°C pathway to a likely catastrophic 4.5°C track. One of their most critical variables is the amount of carbon reduction accomplished through negative emissions, relying on massive implementation of unproven technologies. According to the IPCC, staying under 2°C of global heating — consistent with the minimum target set by the 2015 Paris agreement — involves a heroic assumption that we will suck 730 billion metric tonnes of carbon out of the atmosphere this century. This stupendous amount is equivalent to roughly twenty times the total current annual emissions from all fossil fuel usage. Such an assumption is closer to science fiction than any rigorous analysis worthy of a model on which our civilization is basing its entire future. Yet, even as the IPCC appears willing to model humanity’s fate on a pipe dream, not one of their scenarios explores what is possible from a graduated annual reduction in global GDP. Such a scenario was considered by the IPCC community to be too implausible to consider .

This represents a serious lapse on the part of the IPCC. Climate scientists who have modeled planned reductions in GDP show that keeping global heating below 1.5°C this century is potentially within reach under this scenario, with greatly reduced reliance on speculative carbon reduction technologies. Prominent economists have shown that a carefully managed “post-growth” plan could lead to enhanced quality of life, reduced inequality, and a healthier environment. It would, however, undermine the foundational activity of capitalism — the pursuit of endless growth that has led to our current state of obscene inequality, impending ecological collapse, and climate breakdown.

The profit-based path to catastrophe

As long as this elephant in the room remains unspoken, our world will continue to careen toward catastrophe, even as politicians and technocrats shift from one savior narrative to another. Along with the myth of “green growth,” we are told that a solution lies in putting monetary valuations on “ecosystem services” and incorporating them into business decisions — even though this approach has been shown to be deeply flawed, frequently counterproductive, and ultimately self-defeating. A wetlands, for example, might have value in protecting a city from flooding. However, if it were drained and a swanky new resort built on the reclaimed land, this could be more lucrative. Case closed.

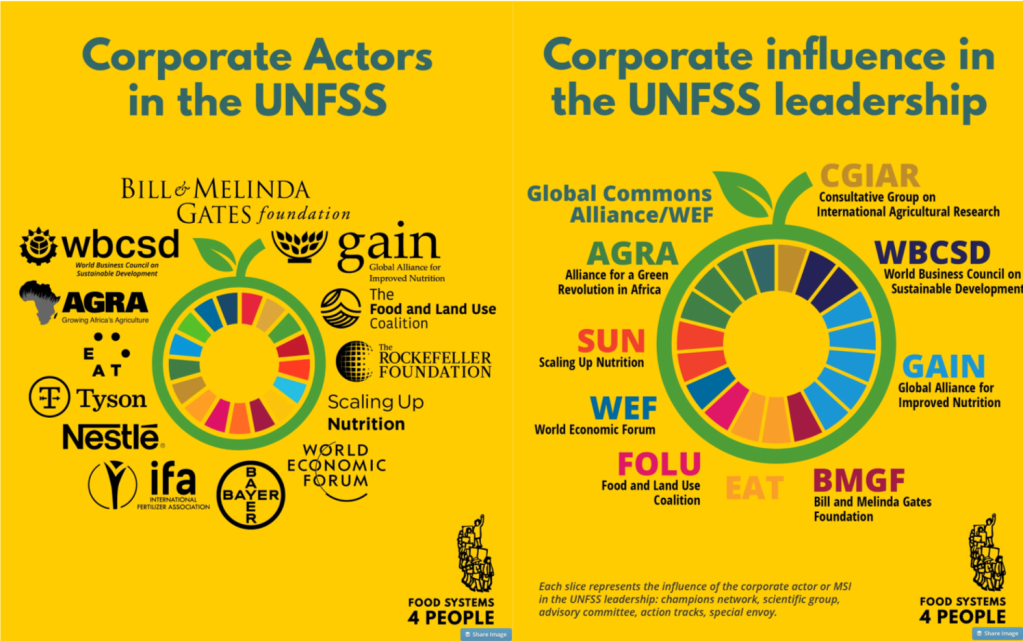

The new moniker arising from the corporate titans at the World Economic Forum is “stakeholder capitalism”: an inviting term that seems to imply that stakeholders other than investors will play a role in setting corporate priorities, but actually refers to a profoundly anti-democratic process whereby corporations assume increasingly large roles in global governance. This month, the UN Food Systems Summit was essentially taken over by the same giant corporations, including Nestlé and Bayer, that are largely responsible for the very problems the summit was intended to grapple with — which led to a widespread boycott by hundreds of civil society and Indigenous groups.

The UN Food Systems Summit was essentially controlled by corporate interests. Source: Food Systems 4 People

As net-zero targets decades away are formally announced at COP26, built implicitly on a combination of corporate procrastination and speculative technologies, we can only expect the climate crisis to continue to worsen. Ultimately, as negative emissions technologies fail to meet their grandiose expectations, the same voices that currently promote reliance on them will lend support to the techno-dystopian idea of geoengineering — vast, planet-altering engineering projects designed to temporarily manipulate the climate to defer a climate apocalypse. A leading geoengineering candidate , financed by Bill Gates, involves spraying particles into the stratosphere to cool the Earth by reflecting the Sun’s rays back into space. The risks are enormous , including the likelihood of causing extreme shifts in precipitation around the world. Additionally, once begun, it could never be stopped without immediate catastrophic rebound heating; it would not prevent the oceans from further acidifying; and may turn the blue sky into a perpetual dull haze. In spite of these concerns, geoengineering is beginning to get discussed at UN meetings, with publications such as The Economist predicting that , since it wouldn’t disrupt continued economic growth, it’s more likely to be implemented than the drastic, binding cuts in emissions that would head off climate disaster.

There is an alternative

Why is the elephant in the room so rarely mentioned in mainstream discourse? One reason is that, since the collapse of communism and the parallel rise of neoliberalism beginning in the 1980s, it is assumed that “there is no alternative,” as Margaret Thatcher famously declared. Even committed green advocates, such as the Business Green group, are quick to dismiss criticism of our growth-based economic system as “knee-jerk anti-capitalist agitprop.” But the conventional dichotomy between capitalism and socialism, to which such conversations inevitably devolve, is no longer helpful. Old-fashioned socialism was just as poised to consume the Earth as capitalism, differing primarily in how the pie should be carved up.

There is, however, an alternative. A wide range of progressive thinkers are exploring the possibilities of replacing our destructive global economic system with one that offers potential for sustainability, greater fairness, and human flourishing. Proponents of degrowth show that it is possible to implement a planned reduction of energy and resource use while reducing inequality and improving human well-being. Economic models, such as Kate Raworth’s “ doughnut economics ” offer coherent substitutes for the classical outdated framework that ignores fundamental principles of human nature and humanity’s role within the Earth system. Meanwhile, large-scale cooperatives, such as Mondragon in Spain, demonstrate that it’s possible for companies to provide effectively for human needs without utilizing a shareholder-based profit model.

Another reason people give for ignoring the elephant in the room, even when they know it’s there, is that we don’t have time for structural change. The climate emergency is already upon us, and we need to focus on actions that can occur right now. This is true, and nothing in this article should be taken as a reason to avoid the drastic and immediate changes required in business and consumer practices. Indeed, they are necessary — but insufficient. Ultimately, our global civilization must begin a transformation to one that is based not on building wealth through extraction, but on foundational principles that could create the conditions for long-term flourishing on a regenerated Earth — an ecological civilization .

Even in the short term, there are innumerable steps that can be taken to steer our civilization toward a life-affirming trajectory. Around the world Indigenous people on the frontline of the climate emergency desperately need support in defending the biodiverse ecosystems in which they are embedded against assaults from extractive corporations. A growing campaign is under way to make the wholesale destruction of natural living systems a criminal act by establishing a law of ecocide —prosecutable like genocide under the International Criminal Court. The powers of transnational corporations themselves need to be addressed, ultimately by requiring their charters to be converted to a triple bottom line of people, planet, and profits, and subject to rigorous enforcement powers.

The transformation we need may take decades, but the process must begin now with the clear and explicit recognition that capitalism itself needs to be supplanted by a system based on life-affirming values. Don’t expect to see any discussion of these issues in the formal proceedings of COP26. But, turn your attention outside the hallowed halls and you’ll hear the voices of those who are standing up for life’s continued flourishing on Earth. It’s only when their ideas are discussed seriously in the main chambers of a future COP that we can begin to hold authentic hope that our civilization may finally be turning away from the precipice toward which it is currently accelerating.

Teaser photo credit: By Hanabusa Itchō – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs divisionunder the digital ID cph.3g08725.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2265247

Jeremy Lent

Related articles.

Geoffrey West: “Metabolism and the Hidden Laws of Biology”

By Nate Hagens , The Great Simplification

On this episode, physicist Geoffrey West joins Nate to discuss his decades of work on metabolic scaling laws found in nature and how they apply to humans and our economies.

April 8, 2024

The art of craft in a digital world

By Annie Landenberger , Vermont Arts & Living

As we continue to wrestle with what it is to be human as manifest in what we produce, one can hope a middle path will emerge, not only in fine art and craft but also in the everyday of a digitized world.

Republican Politics of the Absurd and the Climate Debate

By Joel Stronberg , Civil Notion

I know I’m hardly alone in thinking that the wheels of American democracy feel like they’re coming off the cart. How will we ever solve pressing problems when the debates are so disingenuous?

April 5, 2024

Capitalism in the Last Chance Saloon

Believers in a market economy are dismayed by radical voices arguing that capitalism is incompatible with effective climate action. But unless capitalism's defenders start supporting more ambitious targets and policies to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by mid-century, they should not be surprised if an increasing number of people agree.

LONDON – This year, the evidence that global warming is occurring, and that the consequences for humanity could be severe and potentially catastrophic, has become more compelling than ever. Record global temperatures in June and July. Unprecedented heatwaves in Australia and India, with temperatures above 50°C. Huge forest fires across northern Russia. All of these things tell us that we are running out of time to cut greenhouse-gas emissions and contain global warming to at least manageable levels.

The response has been growing demand for radical action. In the United States, proponents of the Green New Deal argue that America should be a zero-carbon economy by 2030. In the United Kingdom, activists of the “Extinction Rebellion” movement demand the same by 2025, and have severely disrupted London transport through very effective forms of civil disobedience. And the argument that avoiding catastrophic climate change requires rejecting capitalism is gaining ground.

Against this growing tide of radicalism, companies, business groups, and other establishment institutions urge caution and more measured action. Achieving zero emissions as early as 2030, they argue, would be immensely costly and require changes in living standards which most people will not accept. Illegal actions that disrupt others’ lives, it is said, will undermine popular support for necessary measures. A more affordable and gradual path of emissions reduction would be better and still prevent catastrophe, and market instruments operating within the capitalist system could be powerful levers of change.

These counterarguments are robust. The costs of achieving a zero-carbon economy will increase dramatically if we try to get there in ten years, not 30. Most forms of capital equipment naturally need replacement within 30 years, so switching to new technologies over that timeframe would cost relatively little, whereas switching over ten years would require companies to write off large quantities of existing assets.

Technological progress – whether in solar photovoltaic panels, batteries, biofuels, or aircraft design – will make it much cheaper to cut emissions in 15 years than today. And the profit motive is spurring venture capitalists to make huge investments in the new technologies required to deliver a zero-carbon economy.

Meanwhile, decentralized market mechanisms such as carbon pricing are essential to drive change in key industrial sectors, given the multiplicity of possible routes to decarbonization. Socialist planning will not be as effective: Venezuela is an environmental as well as a social disaster. And there is a real danger that excessively rapid action could alienate popular support. After all, the gilets jaunes (yellow vest) movement in France was provoked by tax increases designed to make diesel cars uneconomic, but were imposed at a time when electric vehicles are not yet cheap enough and lack the range to be a viable alternative for less well-off people living outside major cities.

Subscribe to PS Digital

Access every new PS commentary, our entire On Point suite of subscriber-exclusive content – including Longer Reads, Insider Interviews, Big Picture/Big Question, and Say More – and the full PS archive.

Subscribe Now

But it is also true that the capitalist system has failed to respond to the challenge of climate change fast enough; and in some ways, capitalism has impeded effective action. Venture capitalists financing brilliant technological breakthroughs have been matched by industry lobby groups successfully arguing against required regulations or carbon taxes. If adequate policies had been adopted 30 years ago, we would be well on the way to achieving a zero-carbon economy at a very low cost. The fact that we did not is, in part, capitalism’s fault.

Massively accelerated action is now required. All developed economies should commit to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. And zero must mean zero, with no pretense that we can continue burning large quantities of fossil fuels in the late twenty-first century, balanced by equally large quantities of carbon capture and storage.

Developing economies should get there by 2060 at the very latest. That would still leave us vulnerable to significant and unavoidable climate change, but climate science suggests that it would be sufficient to avoid catastrophe. And as the Energy Transitions Commission described in its recent Mission Possible report, it is still possible to achieve that objective at relatively low economic cost, provided we adopt without delay the policies required to drive rapid change.

Carbon taxes should be introduced at a sufficiently high level, and with future increases declared well in advance, to drive the multi-decade investment plans required to decarbonize heavy industry. Carbon tariffs should be used to protect industry from being undercut by imports from countries that fail to apply adequate carbon prices. Airlines should face either steadily rising carbon prices, or regulations requiring them to use a rising proportion of zero-carbon fuels from clearly sustainable sources, with the percentage reaching 100% before 2050.

Blunt but effective instruments – such as banning new sales of internal combustion engine autos from a specific future date, such as 2030, should also be part of the policy armory. And regulations should ban putting plastics in landfills and plastic incineration, forcing the development of a complete plastics recycling system.

None of these policies is anti-capitalist. Instead they are the policies we need to unleash capitalism’s power to solve the problem. Once clear prices and regulations are in place, market competition and the profit motive will drive innovation, and economies of scale and learning-curve effects will force down the costs of zero-carbon technologies. And if we do not unleash that power, we will almost certainly fail to contain climate change.

Believers in a market economy are dismayed by radical voices arguing that capitalism is incompatible with effective climate action. But unless capitalism’s defenders support the immediate establishment of far more ambitious targets and policies to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century, they should not be surprised if an increasing number of people believe that capitalism is the problem and not part of the solution. They will be right to do so.

The Hitler Trial’s Lessons in the Trump Era

Apr 1, 2024 Mark Jones

A European War Union?

Apr 3, 2024 Yanis Varoufakis

Can AI Learn to Obey the Law?

Apr 3, 2024 Antara Haldar

Europe Must Prepare for a Trump Presidency

Apr 3, 2024 Mark Leonard

China Needs a Better Innovation Ecosystem

Apr 2, 2024 Andrew Sheng & Xiao Geng

New Comment

It appears that you have not yet updated your first and last name. If you would like to update your name, please do so here .

After posting your comment, you’ll have a ten-minute window to make any edits. Please note that we moderate comments to ensure the conversation remains topically relevant. We appreciate well-informed comments and welcome your criticism and insight. Please be civil and avoid name-calling and ad hominem remarks.

Email this piece to a friend

Friend's name

Friend's email

- Feedback/general inquiries

- Advertise with us

- Corporate Subscriptions

- Education Subscriptions

- Secure publication rights

- Submit a commentary for publication

- Website help

Please provide more details about your request

We hope you're enjoying our PS content

To have unlimited access to our content including in-depth commentaries, book reviews, exclusive interviews, PS OnPoint and PS The Big Picture, please subscribe

The Right Response to China’s Electric-Vehicle Subsidies

NATO Without America

Can Europeans shore up their collective defense and security by creating an independent, strongly coordinated defense industrial policy in time to adapt to a possible Donald Trump victory this November? There are three reasons to be skeptical, at least for the near term.

No Barbarism Without Poetry

Humanizing the US-China Relationship

Can Europe’s Economy Exceed Expectations in 2024?

Is Techno-Monopoly Inevitable?

An ambitious new theory from an accomplished economist seeks to explain how America came to be dominated by Big Tech. From this analysis comes a range of proposed reforms that many currently would consider impossibly radical.

Can China Reach Its 2024 Growth Target?

Never Underestimate the Nation-State

China Confronts the Middle-Income Trap

✕ log in/register.

Please log in or register to continue. Registration is free and requires only your email address.

Email required

Password required Remember me?

Please enter your email address and click on the reset-password button. If your email exists in our system, we'll send you an email with a link to reset your password. Please note that the link will expire twenty-four hours after the email is sent. If you can't find this email, please check your spam folder.

Reset Password Cancel

- She Writes newsletter

- PS Economics Newsletter

- Promotional emails

By proceeding, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions .

Sign in with

Your Institution

Edit Newsletter Preferences

Set up notification.

To receive email updates regarding this {entity_type}, please enter your email below.

If you are not already registered, this will create a PS account for you. You should receive an activation email shortly.

The Hopeful Environmentalist

The economic, social and cultural dimensions of environmental change

Capitalism must evolve to solve the climate crisis

Holcim (US) Professor of Sustainable Enterprise, University of Michigan

University of Michigan provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

There are two extremes in the debate over capitalism’s role in our present climate change problem. On the one hand, some people see climate change as the outcome of a consumerist market system run rampant. In the end, the result will be a call to replace capitalism with a new system that will correct our present ills with regulations to curb market excesses.

On the other hand, some people have faith in a free market to yield the needed solutions to our social problems. In the more extreme case, some see climate policy as a covert way for bigger government to interfere in the market and diminish citizens’ personal freedom.

Between these two extremes, the public debate takes on its usual binary, black-and-white, conflict-oriented, unproductive and basically incorrect form. Such a debate feeds into a growing distrust many have for capitalism.

A 2013 survey found that only 54% of Americans had a positive view of the term, and in many ways both the Occupy and Tea Party movements share similar distrust in the macro-institutions of our society to serve everyone fairly; one focuses its ire at government, the other at big business, and both distrust what they see as a cozy relationship between the two.

This polar framing also feeds into culture wars that are taking place in our country. Studies have shown that conservative-leaning people are more likely to be skeptical of climate change, due in part to a belief that this would necessitate controls on industry and commerce, a future they do not want. Indeed, research has shown a strong correlation between support for free-market ideology and rejection of climate science. Conversely, liberal-leaning people are more likely to believe in climate change because, in part, solutions are consistent with resentment toward commerce and industry and the damage they cause to society.

This binary framing masks the real questions we face, both what we need to do and how we are going to get there. Yet there are serious conversations within management education, research and practice about the next steps in the evolution of capitalism. The goal is to develop a more sophisticated notion of the role of the corporation within society. These discussions are being driven not only by climate change, but concerns raised by the financial crisis, growing income inequality and other serious social issues.

The market’s rough edges

Capitalism is a set of institutions for structuring our commerce and interaction. It is not, as some think, some sort of natural state that exists free from government intrusion. It is designed by human beings in the service of human beings and it can evolve to the needs of human beings. As Yuval Levin points out in National Affairs, even Adam Smith argued that “the rules of the market are not self-legislating or naturally obvious. On the contrary, Smith argued, the market is a public institution that requires rules imposed upon it by legislators who understand its workings and its benefits.”

And, it is worth noting, capitalism has been quite successful. Over the past century, the world’s population increased by a factor of four, the world economy increased by a factor of 14 and global per capita income tripled . In that time, average life expectancy increased by almost two-thirds due in large part to advances in medicine, shelter, food production and other amenities provided by the market economy.

Capitalism is, in fact, quite malleable to meet the needs of society as they emerge. Over time, regulation has evolved to address emergent issues such as monopoly power, collusion, price-fixing and a host of other impediments to the needs of society. Today, one of those needs is responding to climate change.

The question is not whether capitalism works or doesn’t work. The question is how it can and will evolve to address the new challenges we face as a society. Or, as Anand Giridharadas pointed out at the Aspen Action Forum, “Capitalism’s rough edges must be sanded and its surplus fruit shared, but the underlying system must never be questioned.”

These rough edges need be considered with the theories we use to understand and teach the market. In addition, we need to reconsider the metrics we use to measure its outcomes, and the ways in which the market has deviated from its intended form.

Homo economicus?

To begin, there are growing questions around the underlying theories and models used to understand, explain and set policies for the market. Two that have received significant attention are neoclassical economics and principal-agent theory. Both theories form the foundation of management education and practice and are built on extreme and rather dismal simplifications of human beings as largely untrustworthy and driven by avarice, greed and selfishness.

As regards neoclassical economics, Eric Beinhocker and Nick Hanauer explain:

“Behavioral economists have accumulated a mountain of evidence showing that real humans don’t behave as a rational homo economicus would. Experimental economists have raised awkward questions about the very existence of utility ; and that is problematic because it has long been the device economists use to show that markets maximize social welfare. Empirical economists have identified anomalies suggesting that financial markets aren’t always efficient.”

As regards principal-agent theory, Lynn Stout goes so far to say that the model is quite simply “wrong.” The Cornell professor of business and law argues that its central premise – that those running the company (agents) will shirk or even steal from the owner (principal) since they do the work and the owner gets the profits – does not capture “the reality of modern public corporations with thousands of shareholders, scores of executives and a dozen or more directors.”

The most pernicious outcome of these models is the idea that the purpose of the corporation is to “make money for its shareholders.” This is a rather recent idea that began to take hold within business only in the 1970s and 1980s and has now become a taken-for-granted assumption.

If I asked any business school student (and perhaps any American) to complete the sentence, “the purpose of the corporation is to…” they would parrot “make money for the shareholder.” But that is not what a company does, and most executives would tell you so. Companies transform ideas and innovation into products and services that serve the needs of some segment of the market. In the words of Paul Pollman, CEO of Unilever, “ business is here to serve society .” Profit is the metric for how well they do that.

The problem with the pernicious notion that a corporation’s sole purpose is to serve shareholders is that it leads to many other undesirable outcomes. For example, it leads to an increased focus on quarterly earnings and short-term share price swings; it limits the latitude of strategic thinking by decreasing focus on long-term investment and strategic planning; and it rewards only the type of shareholder who, in the words of Lynn Stout , is “shortsighted, opportunistic, willing to impose external costs, and indifferent to ethics and others’ welfare.”

A better way to gauge the economy

Going beyond our understanding of what motivates people and organizations within the market, there is growing attention to the metrics that guide the outcomes of that action. One of those metrics is the discount rate. Economist Nicholas Stern stirred a healthy controversy when he used an unusually low discount rate when calculating the future costs and benefits of climate change mitigation and adaptation, arguing that there is a ethical component to this metric’s use. For example, a common discount rate of 5% leads to a conclusion that everything 20 years out and beyond is worthless. When gauging the response to climate change, is that an outcome that anyone – particularly anyone with children or grandchildren – would consider ethical?

Another metric is gross domestic product (GDP), the foremost economic indicator of national economic progress. It is a measure of all financial transactions for products and services. But one problem is that it does not acknowledge (nor value) a distinction between those transactions that add to the well-being of a country and those that diminish it. Any activity in which money changes hands will register as GDP growth. GDP treats the recovery from natural disasters as economic gain; GDP increases with polluting activities and then again with pollution cleanup; and it treats all depletion of natural capital as income, even when the depreciation of that capital asset can limit future growth.

A second problem with GDP is that it is not a metric dealing with true human well-being at all. Instead, it is based on the tacit assumption that the more money and wealth we have, the better off we are. But that’s been challenged by numerous studies .

As a result, French ex-president Nicolas Sarkozy created a commission, headed by Joseph Stieglitz and Amartya Sen (both Nobel laureates), to examine alternatives to GDP. Their report recommended a shift in economic emphasis from simply the production of goods to a broader measure of overall well-being that would include measures for categories like health, education and security. It also called for greater focus on the societal effects of income inequality, new ways to measure the economic impact of sustainability and ways to include the value of wealth to be passed on to the next generation. Similarly, the king of Bhutan has developed a GDP alternative called gross national happiness , which is a composite of indicators that are much more directly related to human well-being than monetary measures.

The form of capitalism we have today has evolved over centuries to reflect growing needs, but also has been warped by private interests. Yuval Levin points out that some key moral features of Adam Smith’s political economy have been corrupted in more recent times, most notably by “a growing collusion between government and large corporations.” This issue has become most vivid after the financial crisis and the failed policies that both preceded and succeeded that watershed event. The answers, as Auden Schendler and Mark Trexler point out, are both “policy solutions” and “corporations to advocate for those solutions.”

We can never have a clean slate

How will we get to the solutions for climate change? Let’s face it. Installing efficient LED light bulbs, driving the latest Tesla electric car and recycling our waste are admirable and desirable activities. But they are not going to solve the climate problem by reducing our collective emissions to a necessary level. To achieve that goal requires systemic change. To that end, some argue for creating a new system to replace capitalism. For example, Naomi Klein calls for “ shredding the free-market ideology that has dominated the global economy for more than three decades .”

Klein is performing a valuable service with her call for extreme action. She, like Bill McKibben and his 350.org movement, is helping to make it possible for a conversation to take place over the magnitude of the challenge before us through what is called the “ radical flank effect .”

All members and ideas of a social movement are viewed in contrast to others, and extreme positions can make other ideas and organizations seem more reasonable to movement opponents. For example, when Martin Luther King Jr first began speaking his message, it was perceived as too radical for the majority of white America. But when Malcolm X entered the debate, he pulled the radical flank further out and made King’s message look more moderate by comparison. Capturing this sentiment, Russell Train, second administrator of the EPA, once quipped , “Thank God for [environmentalist] Dave Brower; he makes it so easy for the rest of us to be reasonable.”

But the nature of social change never allows us the clean slate that makes sweeping statements for radical change attractive. Every set of institutions by which society is structured evolved from some set of structures that preceded it. Stephen Jay Gould made this point quite powerfully in his essay “ The Creation Myths of Cooperstown ,” where he pointed out that baseball was not invented by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown New York in 1839. In fact, he points out, “no one invented baseball at any moment or in any spot.” It evolved from games that came before it. In a similar way, Adam Smith did not invent capitalism in 1776 with his book The Wealth of Nations. He was writing about changes that he was observing and had been taking place for centuries in European economies; most notably the division of labor and the improvements in efficiency and quality of production that were the result.

In the same way, we cannot simply invent a new system to replace capitalism. Whatever form of commerce and interchange we adopt must evolve out of the form we have at the present. There is simply no other way.

But one particularly difficult challenge of climate change is that, unlike Adam Smith’s proverbial butcher, brewer or baker who provide our dinner out of the clear alignment of their self-interest and our needs, climate change breaks the link between action and outcome in profound ways. A person or corporation cannot learn about climate change through direct experience. We cannot feel an increase in global mean temperature; we cannot see, smell or taste greenhouse gases; and we cannot link an individual weather anomaly with global climate shifts.

A real appreciation of the issue requires an understanding of large-scale systems through “big data” models. Moreover, both the knowledge of these models and an appreciation for how they work require deep scientific knowledge about complex dynamic systems and the ways in which feedback loops in the climate system, time delays, accumulations and nonlinearities operate within them. Therefore, the evolution of capitalism to address climate change must, in many ways, be based on trust, belief and faith in stakeholders outside the normal exchange of commerce. To get to the next iteration of this centuries-old institution, we must envision the market through all components that help to establish the rules; corporations, government, civil society, scientists and others.

The evolving role of the corporation in society

At the end of the day, the solutions to climate change must come from the market and more specifically, from business. The market is the most powerful institution on earth, and business is the most powerful entity within it. Business makes the goods and services we rely upon: the clothes we wear, the food we eat, the forms of mobility we use and the buildings we live and work in.

Businesses can transcend national boundaries and possess resources that exceed that of many countries. You can lament that fact, but it is a fact. If business does not lead the way toward solutions for a carbon-neutral world, there will be no solutions.

Capitalism can, indeed it must, evolve to address our current climate crisis. This cannot happen through either wiping clean the institutions that presently exist or relying on the benevolence of a laissez faire market. It will require thoughtful leaders creating a thoughtfully structured market.

For all of Andrew Hoffman’s previous articles and columns, click here .

- Climate change

- Green business

Project Officer, Student Volunteer Program

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

The climate crisis is also a crisis of capitalism

We’re way beyond denial now, as the new Assessment Report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes clear.

“Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, human influence on the climate system is clear, and limiting climate change will require substantial and sustained reductions of greenhouse gas emissions.”

Actually, that quote was from the previous IPCC assessment, in 2013 when the consensus among climate scientists was 90%. Now it’s 100% of the 234 scientists from 60 countries involved in writing this latest, landmark report. It makes for chilling reading.

This past decade’s temperatures were probably the hottest it’s been on our planet in 125,000 years. Meanwhile, carbon emissions were higher in 2019 than at any time in at least 2 million years.

The world will reach the catastrophic 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels within 20 years. And this is the best-case scenario, with temperatures rising at least to 2050 and beyond. This outcome only happens with “immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions” in greenhouse gas emissions. Otherwise, sustained 1.5 degrees or 2 degrees Celsius are baked in the cake for centuries, with the accompanying extreme weather events, geopolitical destabilization and vast economic costs.

No wonder U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said the report’s conclusions are “a code red for humanity.”

Or as Oxford scientist Tim Palmer bluntly stated , “if we do not halt our emissions soon, our future climate could well become some kind of hell on Earth.”

And the long process of vetting and writing the latest report didn’t take account of this year’s drought, fires and floods worldwide.

Extreme heat struck the Pacific Northwest this summer. Ocean acidification is threatening wildlife and fishing stocks. Sea-level rise will swamp some communities, including the lower village on the Quinault Indian Nation in Grays Harbor County. Drought is endangering agriculture — in 2020 this was Washington’s most valuable merchandise export.

As Anjana Ahuja wrote in Financial Times , “Climate reality is here and is outrunning the simulations.” This isn’t alarmism but facts.

One of the most important questions is whether capitalism can be part of the solution or will it inevitably be the heart of the problem.

For people of a certain age, this is crackpot heresy. They remember the environmental damage done in communist countries, by many measures far worse than in the West. They recall then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s famous proclamation, “There is no alternative.” Meaning no alternative to a market economy.

Even increasingly authoritarian China, under the rule of the Communist Party, operates as a capitalist economy, albeit with state control.

China is the world’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions — and this is used by some as an excuse for the United States to do nothing. But Beijing signed the Paris climate accords and is implementing several initiatives to become carbon neutral by 2060. It’s only a start, undermined by the coal dependency of its Belt and Road program.

Reducing emissions is part of the business plans of major corporations. For example, in 2019 Amazon co-founded the Climate Pledge , “a commitment to be net-zero carbon across our business by 2040, 10 years ahead of the Paris Agreement.” More than 100 companies have signed on.

Boeing, aware of the huge carbon footprint of aviation, is testing hydrogen-powered small turboprop airplanes at Moses Lake. The goal: to show that low-emission hydrogen has a future in larger aircraft.

Meanwhile, electric vehicles are driving (forgive me) the future of major automakers. Ford is investing $22 billion through 2025 in creating electric vehicles, including an all-electric Mustang. GM is doing the same. President Joe Biden is calling for half of all auto sales to be electric by 2030.

And yet, can capitalism move fast enough and far enough? The evidence isn’t heartening considering how much of the economy remains dependent on fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, younger Americans have less faith in capitalism and are more open to socialism.

Whatever you call the economic system, it must speed the rapid decarbonization necessary to avoid the worst outcomes of the climate crisis.

That means strong government action to tax carbon with the goal of keeping most of it in the ground; investing in extensive networks of electric-powered high-speed trains and transit; extensive tree planting; incentivizing low-carbon technologies; preventing wasted food (everything from production to methane emissions produce enormous climate problems); and requiring “carbon smart” farming that stores carbon in the soil instead of releasing it in the atmosphere.

Most Read Business Stories

- How Boeing put Wall Street first, safety second ahead of Alaska Air blowout

- What’s behind the ‘outrageous’ rise in WA car insurance rates

- One big reason Gen Z is still on Facebook: To save money VIEW

- Target’s latest ads feature Kristen Wiig’s SNL ‘Target Lady’ and Prince’s music

- Switching from iPhone to Android is easy. It’s the aftermath that stings

Market forces alone won’t achieve these and other steps necessary to drastically cut emissions.

Meanwhile, is America’s experiment in self-government up to the task? A 2020 Pew Research Center poll found two-thirds of respondents think the government should do more to address climate change.

But Republicans especially are opposed to most policies needed. Another Pew poll found that climate change is low among the priorities of GOP voters; only 17% said humans contribute a great deal to the crisis — something the latest IPCC report soundly refutes.

In our closely divided country, Republicans can slow and halt climate progress. State-level vote-suppression laws make it even more possible they will take control of one or both houses of Congress in next year’s election.

Decarbonizing the economy can be a net gain in jobs and prosperity, especially in the long run. More people work in the solar and wind industries than in coal or other fossil fuel extraction.

But we can’t sugarcoat the pain of the near-term transition. People will need to drive less, pay the actual cost in carbon emissions for suburban or exurban lifestyles, and require assistance moving out of fossil fuel jobs.

Here another noncapitalist response needs examination: the universal basic income. This could be guaranteed to all citizens or tailored to those most affected by decarbonization.

Ultimately, political will and popular support are required for all this. But the alternative is hell.

The opinions expressed in reader comments are those of the author only and do not reflect the opinions of The Seattle Times.

Advertisement

- Previous Article

Carbon Markets in a Climate-Changing Capitalism

- Cite Icon Cite

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

Jongeun You; Carbon Markets in a Climate-Changing Capitalism. Global Environmental Politics 2021; 21 (2): 168–170. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_r_00603

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The world is likely not on track to achieve the considerable carbon emissions reductions required to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Carbon markets, imposing a price on the carbon content of fossil fuels, are feasible and durable tools to control carbon emissions, despite political challenges (Rabe 2018 ). Through carbon markets, such as carbon taxation or cap-and-trade programs, policy makers aim to internalize the negative externalities of fossil fuel usage and to redistribute revenues to low-carbon innovation and communities that have been impacted by climate change.

Carbon Markets in a Climate-Changing Capitalism argues that the fossil fuel industry has exercised excessive influence over the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS); this influence inhibits the beneficial role of the world’s largest carbon market in addressing the climate crisis. Carbon emissions in the EU during the last decade showed a decline, but the environmental benefit of the EU ETS should have been higher and more dispersed than now, according to Bryant. He argues that adequate regulatory intervention by governments over carbon emissions and fossil fuel industries is needed to maximize the effectiveness of carbon market policy. This complementary measure is expected to mitigate the limitation of the EU ETS, obsessively relying on dominant economic discourses.

The book contextualizes the relationship between capitalism and climate change. Capitalism—a political-economic system characterized by capitalization, property rights, and voluntary exchange—has resulted in a drastic change in climate and environment beyond nature’s resilience capacity. Simultaneously, a changing climate has enabled capitalism to respond to global warming and social pressures on the industry. This response can be made by altering its value chain to be climate-friendly or by bolstering capitalism’s dependence on fossil fuels and creating additional damages to nature.

Bryant’s concept of “climate-changing capitalism” may help researchers better understand and evaluate competing climate policies. Using this lens, the book suggests three contradictions and tensions embedded in the EU ETS. First, capitalism produces climate change unevenly. Though a small number of companies and governments contributed to a large proportion of emissions (the twenty biggest emitters contributed half of emissions in the EU ETS during 2005–2012), the responsibility for reducing emissions was distributed across many other actors of the EU ETS (including more than 3,500 companies). Carbon commodification that separates emissions from installations led heavy emitters to internalize emission inequalities.

Second, carbon markets depend on fossil fuel use. From a financial sector standpoint, market viability and interest hinge on stringent emission caps and high carbon prices. However, governance issues (e.g., the inflow of international carbon credits, an oversupply of carbon allowances) and once-low European carbon prices (less than €10 per metric ton of CO 2 emissions between November 2011 and February 2018) promoted the exit of financial investors from the market.

Third, capitalism constrains climate change responses. Owing to the inertia of policy implementation and limited resources, EU governments and related stakeholders tend to privilege a carbon market–based approach over climate policy alternatives because there is an existing, legitimate institution. Instead of transformative climate policies, the EU ETS members have preferred to reform the system itself (via, e.g., market stability reserve and revised free allocation rules) while undermining the diverse debate on climate policy.

A weakness of Bryant's book lies in its focus on the fossil fuel industry, demonstrating a slight anti-industry bias. Bryant firmly criticizes some heavy emitters for lobbying the EU, seeking favorable treatment, and trading carbon allowances and offset credits. Furthermore, he claims that those emitters were reluctant to expand renewable energy supplies by exploiting the EU ETS, delaying the transition to a low-carbon economy. These arguments warrant further investigation and updated evidence. For instance, while Bryant used 2015 data in judging practices of RWE, the company reduced its emissions by one-third from 2012 to 2018, and even declared in 2019 its intention to achieve carbon neutrality by 2040 (RWE AG 2019 ). Another company, E.ON, also provided 100 percent renewable electricity supply to its residential customers in the United Kingdom in 2019 (E.ON SE 2019 ). Corroborating evidence demonstrates the fossil fuel industry undergoing a structural change with reduced emissions, while the industry optimizes its management strategy for given conditions and closely collaborates with the public and civil sectors. The book also lacks a detailed discussion of the impact of the EU ETS on low-carbon technology advancement. Whether and how the EU ETS encourages research and development of low-carbon technologies are essential for appreciating capitalism’s role in carbon markets.

The EU ETS is a fundamental component of the EU’s roadmap to a low-carbon economy by 2050. Recognizing the importance of the system designed to incentivize emission reductions while making the emitters pay for their social costs, this book raises awareness of the system’s socioecological, economic, and political problems in its current form. Bryant’s arguments reflect the theoretical and empirical developments on carbon markets. As the fourth trading period of the EU ETS started in 2021, the book may help strengthen the main instrument of European climate policy by revealing implementation issues in the context of a climate-changing capitalism. Additionally, considering the relatively long history of the EU ETS, the book may provide insights to other carbon markets worldwide by delineating the contradictions of carbon markets.

Email alerts

Related articles, related book chapters, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1536-0091

- Print ISSN 1526-3800

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Open Access

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Global Social Challenges

Is capitalism causing climate change.

by Chris Waugh | Jul 7, 2022 | Climate change and sustainable development | 0 comments

Photo by Ma Ti on Unsplash

By Aileen Murphy

‘Save electricity, recycle, buy sustainable brands, use public transport, eat less meat.’ These are some of the few things we constantly hear to prevent climate change and are used as ways to pin this on the greater population. But when we look closer at it, who’s really to blame? Capitalism.

Throughout our time on earth, humans have gradually changed our natural environment through the rise of capitalism and new modes of production, which as Marx describes, “comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.” Capitalism can be claimed as the main cause of global warming and effectively the climate crisis, reducing the life span of many species on earth. Therefore, it is only right to try and reform capitalism or further try and remove it to save the state of the earth for future generations.