Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.307-398

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 3 pp.203-304

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 2 pp.107-201

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 1 pp.1-71

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Behavioral Management for Children and Adolescents: Assessing the Evidence

- Melissa H. Johnson , M.A., M.P.H. ,

- Preethy George , Ph.D. ,

- Mary I. Armstrong , Ph.D. ,

- D. Russell Lyman , Ph.D. ,

- Richard H. Dougherty , Ph.D. ,

- Allen S. Daniels , Ed.D. ,

- Sushmita Shoma Ghose , Ph.D. , and

- Miriam E. Delphin-Rittmon , Ph.D.

Search for more papers by this author

Behavioral management services for children and adolescents are important components of the mental health service system. Behavioral management is a direct service designed to help develop or maintain prosocial behaviors in the home, school, or community. This review examined evidence for the effectiveness of family-centered, school-based, and integrated interventions.

Literature reviews and individual studies published from 1995 through 2012 were identified by searching PubMed, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress, the Educational Resources Information Center, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. Authors chose from three levels of evidence (high, moderate, and low) based on benchmarks for the number of studies and quality of their methodology. They also described the evidence of service effectiveness.

The level of evidence for behavioral management was rated as high because of the number of well-designed randomized controlled trials across settings, particularly for family-centered and integrated family- and school-based interventions. Results for the effectiveness of behavioral management interventions were strong, depending on the type of intervention and mode of implementation. Evidence for school-based interventions as an isolated service was mixed, partly because complexities of evaluating group interventions in schools resulted in somewhat less rigor.

Conclusions

Behavioral management services should be considered for inclusion in covered plans. Further research addressing the mechanisms of effect and specific populations, particularly at the school level, will assist in bolstering the evidence base for this important category of clinical intervention.

Problem behavior early in life can be related to later development of negative outcomes, such as school dropout, academic problems, violence, delinquency, and substance use; in addition, early childhood delinquent behavior may predict criminal activity in adulthood ( 1 – 7 ). Therefore, interventions designed to address problem behavior and increase prosocial behavior are important for children and adolescents and for families, teachers, school officials, community members, and policy makers. This article provides an assessment of behavioral management interventions for children and adolescents who have behavior problems.

This article reports the results of a literature review that was undertaken as part of the Assessing the Evidence Base Series (see box on next page). For purposes of this series, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has described behavioral management as a direct service that is designed to help a child or adolescent develop or maintain prosocial behaviors in the home, school, or community. Examples of these behaviors include demonstrating positive, nonaggressive relationships with parents, teachers, and peers; showing empathy and concern for others; and complying with rules and authority figures. Table 1 presents a description of the service and its components. Behavioral management interventions are individualized to the person’s needs.

About the AEB Series

The Assessing the Evidence Base (AEB) Series presents literature reviews for 13 commonly used, recovery-focused mental health and substance use services. Authors evaluated research articles and reviews specific to each service that were published from 1995 through 2012 or 2013. Each AEB Series article presents ratings of the strength of the evidence for the service, descriptions of service effectiveness, and recommendations for future implementation and research. The target audience includes state mental health and substance use program directors and their senior staff, Medicaid staff, other purchasers of health care services (for example, managed care organizations and commercial insurance), leaders in community health organizations, providers, consumers and family members, and others interested in the empirical evidence base for these services. The research was sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to help inform decisions about which services should be covered in public and commercially funded plans. Details about the research methodology and bases for the conclusions are included in the introduction to the AEB Series ( 26 ).

The treatment literature includes a variety of behavioral management interventions that are designed to address problem behaviors (for example, externalizing or acting-out behaviors) of children and adolescents when implemented in various settings. Given the breadth and variations of these interventions, behavioral health policy makers, providers, and family members may benefit from a brief review of specific behavioral management interventions and their value as covered services in a benefit package.

The purposes of this article are to describe behavioral management services and highlight specific behavioral management interventions that are implemented in community settings, rate the level of evidence (methodological quality) of existing studies, and describe the effectiveness of these services on the basis of the research. We identify three models of behavioral management interventions that can be implemented, depending on the intervention setting and the needs of children or groups of children and their families. To facilitate use by a broad audience of mental health services personnel and policy makers, we provide an overall assessment of research quality and briefly highlight key findings. The results will provide state mental health directors and staff, policy officials, purchasers of health services, and community health care administrators with a simple summary of the evidence for a range of behavioral management services and implications for research and practice.

Description of behavioral management

Behavioral management for children and adolescents is a general category of intervention that is often incorporated as part of a variety of clinical practices that differ by setting and populations of focus. These interventions share common goals, which are listed in Table 1 . Behavioral management interventions for children and adolescents included in this review address various problem behaviors, including noncompliance at home or at school, disruptive behavior, aggressive behavior, rule breaking, and delinquent behaviors. For purposes of this article, clinical components of behavioral management interventions for children were compiled from various practice-relevant sources ( 8 – 11 ).

Behavioral management is grounded in social learning theory and applied behavior analysis. Social learning theory asserts that people learn within a social context, primarily by observing and imitating the actions of others, and that learning is also influenced by being rewarded or punished for particular behaviors ( 12 ). Based on the principles of social learning theory, applied behavior analysis uses general learning principles, direct observation, objective measurement, and analytic assessment to shape behavior and solve problems that are clinically significant for an individual or family ( 11 ). The approach often is used for children with autism spectrum disorders; however, applied behavior analysis principles and techniques can be used more generally with behavioral management interventions for various child behavior problems.

Examples of specific behavioral management treatment activities include observing and documenting child behaviors, identifying antecedents of behaviors, utilizing motivating factors in reinforcement strategies, developing behavioral plans to address identified problem behaviors, coordinating interventions across different settings in which children function, and training other individuals in a child’s life to address specific behavioral objectives or goals. Behavioral management services typically are delivered through an individualized plan that is based on a clinical assessment. An assessment identifies the needs of the child or adolescent and the family and establishes goals, intervention plans, discharge criteria, and a discharge plan. Behavioral management plans are implemented through teaching, training, and coaching activities that are designed to help individuals establish and maintain developmentally appropriate social and behavioral competencies. Services may involve coordination of other care or referral to complementary services.

Behavioral management interventions may be delivered by family members, teachers, professional therapists, or a team of individuals working in concert to address the needs of a child or adolescent. A behavioral management therapist collaborates with the child or adolescent and the family to develop specific, mutually agreed-upon behavioral objectives and interventions to alter or improve specific behaviors. The resulting behavioral management treatment plan may also include a risk management or safety plan to identify risks that are specific to the individual. In some cases, a contingency plan is developed to address specific risks should they arise. Behavioral management professionals work in partnership with family members or teachers to implement a behavioral plan and monitor the child’s behavior and progress.

Three basic models of behavioral management interventions in the research literature are family-centered behavioral interventions, school-based behavioral interventions that can include services implemented across grades or classrooms or as individually targeted services, and integrated home-school programs. We focus on behavioral management interventions for children who are evidencing problem behavior and on interventions that include families and have some level of personalization that addresses the child’s needs.

Family-centered behavioral interventions

Family-centered interventions emphasize the role of parents or other caregivers in helping to manage problem behaviors of children, and they frequently focus on parenting practices. The interventions can be clinic based or offered in community settings or in the home. Behavioral parent training interventions are among the more commonly used family-centered behavioral management models. These interventions specifically target individual children with identified behavior problems and their families and generally teach parents to increase positive interactions with children and reduce harsh and inconsistent discipline practices. Behavioral parent training programs are delivered in a variety of formats. For example, some behavioral parenting interventions may involve parents, children, or teachers, and some may be delivered only to parents. Behavioral parent training interventions also vary in the extent to which they are customized to specific needs of the child. For purposes of this article, we focus on behavioral parent training interventions that involve planning for specific behavior problems that are expressed by a child and working with the parent and child, rather than group-based parent training programs that do not involve the child or are not customized based on specific behavioral needs.

Two family-centered behavioral interventions that meet the criteria for this review are Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) and the Incredible Years programs. PCIT uses live coaching of parents during parent-child interactions to help parents establish nurturing relationships with their children, clear parent-child communication and limit setting, and consistent contingencies for child behavior ( 13 , 14 ). The Incredible Years parent training and child training programs involve addressing problem behavior of children aged two to ten years who have a diagnosis of a disruptive behavior disorder or are exhibiting subclinical levels of problem behavior ( 15 , 16 ). During treatment, a therapist works with parents and children in group settings and uses vignettes, focused discussions, role plays, and problem-solving approaches to illustrate and discuss specific behavioral management techniques. Both of these interventions incorporate behavioral management strategies of rewarding prosocial behavior, limiting reinforcement of inappropriate behavior, and delivering appropriate consequences for misbehavior.

School-based behavioral interventions

School-based behavioral interventions specifically target problem behaviors that occur in the school setting, and they use teachers and school staff as interveners in the management of student behaviors. One model that is commonly used in school settings is Positive Behavior Support (PBS). This model describes strategies that are implemented with the whole school to improve behavior and school climate and to prevent or change patterns of problem behavior ( 17 ). Based on applied behavior analysis, person-centered planning (an approach designed to assist the individual in planning his or her life and supports, often to increase self-determination and independence), and inclusion principles, PBS aims to support behavioral success by implementing nonpunitive behavioral management techniques in a systematic and consistent manner ( 18 , 19 ). PBS models of intervention seek to prevent problem behavior by altering conflict-inducing situations before problems escalate while concurrently teaching appropriate alternative behaviors ( 8 ).

Specific school-based interventions developed based on the PBS model include Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports ( 20 ) and Safe & Civil Schools ( 21 ). These school-based interventions implement behavioral management strategies and tailor the level of intervention for the unique needs of a child or adolescent. PBS interventions utilize three levels of treatment: a primary tier, applied to the entire school setting to prevent challenging behaviors; a secondary tier, targeting individuals who display emerging or moderate behavior problems; and a tertiary tier for students who evidence more significant behavior problems and require complex and individualized team-based support beyond what is delivered at the primary and secondary levels ( 10 ). Interventions at the tertiary level involve tailored behavioral management strategies outlined in a behavioral management plan ( 22 ). To direct this review to treatment approaches for children with identified behavior problems, we focused on school-based behavioral management interventions that fall within the tertiary tier of intensity.

Integrated behavioral interventions

Integrated interventions combine school- and family-centered treatment components to create cohesive programs that address child behaviors in school and home settings. Three integrated programs are assessed in this review: Fast Track, Child Life and Attention Skills (CLAS), and the Adolescent Transitions Program (ATP). The Fast Track program is a long-term intervention that is designed to prevent antisocial behavior and psychiatric disorders among children identified as demonstrating disruptive behavior by parents and teachers. It uses a combination of parent behavioral management training, child social cognitive skills training, tutoring or mentoring, individualized home visits, and a classroom curriculum ( 23 ). The CLAS program is designed to reduce inattention symptoms and improve organizational and social skills among children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), inattentive type, through a combination of teacher consultation, parent training, and child skills training ( 24 ). ATP is a communitywide, family-centered intervention delivered through schools that takes a multilevel approach to addressing adolescent behavior problems ( 25 ). Similar to the three-tiered system of intervention described with school-based PBS, ATP uses tiered universal, selected, and indicated interventions to address different groups of children and families, depending on the child’s level of symptom expression. That is, universal interventions are designed for all parents and children in a school setting, selected interventions are for families and children at elevated risk, and indicated interventions are for families of children with early signs of problem behavior that do not yet meet clinically diagnosable levels of a mental disorder. The indicated level of intervention entails a variety of family treatment services, including brief family intervention, a school monitoring system, parent groups, behavioral family therapy, and case management services. These components vary depending on the individual needs of the child and family.

Search strategy

To provide a summary of the evidence and effectiveness for behavioral management, we conducted a survey of major databases: PubMed (U.S. National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health), PsycINFO (American Psychological Association), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress, the Educational Resources Information Center, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

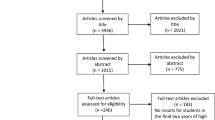

We reviewed meta-analyses, research reviews, and individual studies from 1995 through 2012. We also examined bibliographies of major reviews and meta-analyses. We used combinations of the following search terms: behavioral management, behavior management, behavioral management therapy, behavior specialist, mental health, substance abuse, children, and adolescents. Additional citations were gathered from reference sections of articles. We used an independent consensus process when reviewing abstracts found through the literature search to determine whether a study used a behavioral management approach, on the basis of the conceptual definition of behavioral management provided above.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review included U.S. and international studies in English of the following types: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, and review articles, such as meta-analyses and systematic reviews. The focus of this review was on clinical intervention approaches for children or adolescents who presented with problem behaviors or elevated risk at the beginning of the intervention. Included in the search were studies of family-focused parent training interventions that involved individualization based on the needs of the child and that involved the child and family members. Also included were studies of interventions in which the child or adolescent was selected for inclusion on the basis of the presence of problem behaviors that were targeted for change during the active treatment period.

Some populations and intervention programs were excluded to ensure basic similarities of the participants, interventions, and outcome measures and to be able to draw conclusions about whether the behavioral management intervention itself (as opposed to other intervention components) was associated with the outcomes. Studies that focused on children with autism spectrum disorders or other pervasive developmental disorders, intellectual disabilities, or fetal alcohol spectrum disorder were excluded. There is a large body of literature on behavioral management interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental disabilities, which we believe would be more appropriately reviewed in a separate article. Also excluded were universal preventive interventions that are not part of a multitiered program, because of our focus on individualized clinical intervention approaches. Universal preventive interventions address all individuals in a population, regardless of symptom severity or level of risk; as a result, the strategies and approaches used are distinct from those of more targeted interventions and more appropriately reviewed in a separate article. Finally, we excluded intervention models that may incorporate behavioral management components but are not exclusively behavioral management interventions or do not explicitly focus on child and adolescent behavior problems, such as Homebuilders, Multisystemic Therapy, Functional Family Therapy, individual cognitive-behavioral therapy, and behavioral management interventions in residential treatment centers and psychiatric hospitals.

Strength of the evidence

The methodology used to rate the strength of the evidence is described in detail in the introduction to this series ( 26 ). The research designs of the studies identified by the literature search were examined. Three levels of evidence (high, moderate, and low) were used to indicate the overall research quality of the collection of studies. Ratings were based on predefined benchmarks that considered the number and quality of the studies. If ratings were dissimilar, a consensus opinion was reached.

In general, high ratings indicate confidence in the reported outcomes and are based on three or more RCTs with adequate designs or two RCTs plus two quasi-experimental studies with adequate designs. Moderate ratings indicate that there is some adequate research to judge the service, although it is possible that future research could influence initial conclusions. Moderate ratings are based on the following three options: two or more quasi-experimental studies with adequate design; one quasi-experimental study plus one RCT with adequate design; or at least two RCTs with some methodological weaknesses or at least three quasi-experimental studies with some methodological weaknesses. Low ratings indicate that research for this service is not adequate to draw evidence-based conclusions. Low ratings indicate that studies have nonexperimental designs, there are no RCTs, or there is no more than one adequately designed quasi-experimental study.

We accounted for other design factors that could increase or decrease the evidence rating, such as how the service, populations, and interventions were defined; use of statistical methods to account for baseline differences between experimental and comparison groups; identification of moderating or confounding variables with appropriate statistical controls; examination of attrition and follow-up; use of psychometrically sound measures; and indications of potential research bias.

Effectiveness of the service

We described the effectiveness of the service—that is, how well the outcomes of the studies met the service goals. We compiled the findings for separate outcome measures and study populations, summarized the results, and noted differences across investigations. We considered the quality of the research design in our conclusions about the strength of the evidence and the effectiveness of the service.

Results and discussion

Level of evidence.

Five reviews of family-centered behavioral interventions ( 16 , 27 – 30 ), two reviews of school-based behavioral interventions ( 9 , 19 ), and one review of integrated behavioral interventions ( 25 ) were identified. Twelve RCTs that had been published after the previous reviews had been conducted were also identified. Their topics were family-centered behavioral interventions ( 31 – 34 ), school-based behavioral interventions ( 35 – 37 ), and integrated behavioral interventions ( 23 , 24 , 38 – 40 ). Tables 2 and 3 summarize the reviews and the RCTs, respectively.

a Articles are in chronological order by intervention type. Review articles sometimes included citations for interventions not described in this article. Only studies of interventions included in this article are described in the table. Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CD, conduct disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; PCIT, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial

a Articles are in chronological order by intervention type. Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CD, conduct disorder; CLAS, Child Life and Attention Skills; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; PCIT, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy;

b Multiple publications based on the same randomized controlled trial

Participants who received behavioral management interventions included children in preschool, elementary, middle, and high school grades. Studies included a range of racial-ethnic groups and rural and urban populations. Across studies, children who received behavioral management interventions typically were described as exhibiting problem behaviors or externalizing behaviors.

Overall, given the strength of the research designs in more than three RCTs, the level of evidence for the various types of behavioral management interventions was rated as high. However, the complexities of evaluating school-based interventions have resulted in somewhat less rigor in that area of behavioral management research. Reviews and individual studies of family-based and integrated family- and school-based behavioral management interventions included in this review used strong RCT designs, and several included intent-to-treat analyses.

RCTs of family-centered behavioral interventions (as defined for this article) have been examined in multiple review articles ( 27 – 30 ) and individual studies. Across both types of publications, the evaluations examining the effects of PCIT and Incredible Years behavioral parenting programs had adequate statistical power to detect treatment effects, used well-designed RCTs, utilized interventions with treatment manuals and fidelity data, and measured clinical outcomes with reliable and valid assessment instruments. Findings for both programs have also been replicated in multiple RCTs conducted by independent investigators.

Researchers have noted that most studies evaluating the effectiveness of tertiary-level school-based interventions have included students with significant disabilities in self-contained classrooms, which limits the generalizability of the evidence to general education students in typical classroom settings ( 37 , 41 ). Researchers also noted that studies in this body of literature generally have small samples, lack RCTs, use single-subject or within-group research designs, do not always use standardized behavioral management protocols, and are limited in their ability to report whether school personnel were implementing the interventions with fidelity ( 37 , 41 – 43 ). However, in this review we included three studies of tertiary-level school-based interventions using RCTs ( 35 – 37 ). Researchers indicated various limitations of the design (which varied across studies), including the lack of fidelity measures of team implementation of the intervention, attrition over time, limited measurement of interrater reliability of observational data, lack of validated assessment measurement, and lack of statistical analyses to account for school-level differences.

Integrated behavioral management intervention studies included in this review used strong RCT designs, had adequate statistical power to detect treatment effects, and used intent-to-treat analyses ( 23 – 25 ). One limitation is that these integrated behavioral management interventions have been studied primarily by program developers. The literature would be strengthened if these RCTs were replicated by independent researchers and demonstrated similar results.

Family-centered behavioral interventions.

Family-centered parent training interventions have been reviewed extensively and have demonstrated strong effects in reducing and preventing problem behaviors across a range of ages and populations when compared with wait-list control groups ( 16 , 28 – 30 ). Reviews found PCIT to be effective in reducing disruptive behavior of young children. Eyberg and colleagues ( 16 ) reviewed two well-designed RCTs with wait-list control groups and indicated that PCIT was superior in reducing disruptive behavior of children aged three to six years. The comparison groups in the two studies were not active controls or placebo treatment conditions, which resulted in a “probably efficacious” rating for PCIT ( 16 ). A meta-analysis of PCIT included 13 studies from eight cohorts and three research groups ( 28 ). The researchers compared children who received PCIT with children in nonclinical comparison groups and concluded that mothers of children who received PCIT reported greater declines in problem behaviors. There were large effects for positive behaviors observed in the classroom.

Adaptations and abbreviated versions of PCIT and the Incredible Years program showed preliminary positive effects in various populations, including Mexican-American families ( 44 ), Chinese families ( 33 , 45 ), African-American families ( 46 ), children in Head Start ( 47 , 48 ), and children identified in pediatric medical settings ( 31 , 32 , 49 ). Various forms of the Incredible Years program implemented for children with significant needs reduced problem behaviors among children with a diagnosis of ADHD ( 34 ) and oppositional defiant disorder ( 50 ) six months after the intervention. Overall, compared with control groups, these family-centered parent training programs had strong effects in reducing externalizing behaviors (immediately after the intervention and at follow-up) among children across a range of ages.

School-based interventions.

Research findings were mixed on the effectiveness of tertiary-level school-based interventions. Two meta-analyses of tertiary-level interventions that used functional behavioral assessments found that these interventions were effective in reducing problem behavior across a range of disabilities and grades ( 9 , 19 ). However, these results should be interpreted with caution, because the studies evaluated in these reviews had methodological limitations (for example, single-participant research designs and small samples). Two RCTs with elementary school students found effects in reducing externalizing behavior, compared with control groups, at the end of the intervention ( 36 ) and at the follow-up 14 months after the pretest ( 37 ), as indicated by self-reported scores on standardized instruments and observer ratings of student behavior. Compared with students in control groups, students in the intervention group also evidenced higher ratings of self-reported social skills; improvements were also seen in time engaged in academic activities, as measured by independent observational assessment ( 36 ). These positive effects were not replicated in a rigorous RCT that examined the effects of a three-tiered, schoolwide aggression intervention in early- and late-grade elementary schools in an inner city and in an urban poor community ( 35 ). Researchers found that compared with the control condition, the tertiary-level intervention had significant effects on aggressive behavior when it was delivered to children during the early school years in the urban poor community. Aggressive behavior was measured through a composite of standardized assessment instruments. However, none of the interventions were effective in preventing aggression among older elementary school children.

Integrated behavioral management interventions.

Integrated interventions demonstrated promising findings in preventing and reducing problem behaviors among diagnosed and at-risk children. The Fast Track program had a significant impact on lowering the likelihood of diagnosis of conduct disorder and externalizing behavior among children identified as being at the highest risk of antisocial behavior; however, the intervention did not have an impact on the resulting diagnoses of children who had moderate baseline risk levels ( 23 ). In a recent article that assessed the impact on the onset of various disorders of random assignment to the Fast Track intervention, researchers found that the intervention implemented over a ten-year period prevented externalizing psychiatric disorders among the highest risk group, including during the two years after the intervention ended ( 40 ). In another study, youths who had participated in the Fast Track program had reduced use of professional general medical, pediatric, and emergency department services for health-related problems, compared with youths in a control group, ten years after the first year of the intervention ( 39 ). These findings indicate that this program could be very beneficial and cost-effective if targeted to high-risk children.

The CLAS program also demonstrated significant positive results; children receiving this intervention showed decreased inattention symptoms and increased social and organizational skills compared with peers who were assigned randomly to a control group ( 24 ). For families randomly assigned to ATP, adolescents had lower rates of antisocial behavior and substance use, and families reported stronger parent-child interactions and parenting practices, compared with those in control conditions ( 25 , 38 ). Overall, the effectiveness of integrated behavioral management interventions can be characterized as relatively strong.

Evidence is promising regarding the effectiveness of specific behavioral management interventions. Although these effects vary depending on setting and intervention type and some studies had methodological limitations, a number of reviews and subsequent studies have reported positive results of these interventions for improving child behavior in multiple settings. The level of evidence is in the high range, particularly among family-centered and integrated family-school program models (see box on this page). The benefits of integrated family-school models include service access for families. If implemented early, such interventions may assist in early detection and treatment of problem behaviors before they become more severe. Children and adolescents have been shown to benefit from these interventions, and given the importance of early intervention to reduce the potentially negative consequences of disruptive behavior later in life, these findings are encouraging. In addition, integrated family-school approaches appear to allow strategies that are implemented in the home to be reinforced in school settings, thus providing an additional level of collaboration and support between the school and family.

Evidence for the effectiveness of behavioral management for children and adolescents: high

Overall, positive outcomes found in the literature:

For policy makers and payers (for example, state mental health and substance use directors, managed care companies, and county behavioral health administrators), the findings of this review suggest a number of benefits to the implementation of behavioral management interventions. Detection and intervention at early stages of problem behavior generally are less costly than intensive services for severe problem behavior. Implementation of effective treatment when children exhibit early signs of problem behavior may prevent future engagement in criminal activity, substance use, and juvenile justice system involvement. It may also reduce the need for costly emergency services or residential treatment. There has been limited research examining the long-term outcomes of behavioral management interventions; however, some studies—such as those investigating Fast Track ( 39 , 40 )—have shown positive long-term results into young adulthood. There could be considerable cost savings if these interventions demonstrate long-lasting impacts; thus, future research should continue to examine the long-term outcomes of these types of behavioral management programs.

Studies need to be replicated by independent investigators in ethnically and racially diverse populations to confirm the strength of the evidence base and generalizability of the results. The level of evidence is somewhat dependent on the implementation setting assessed, and research findings are mixed on the effectiveness of school-based interventions that are not integrated with family interventions. There is a need for further research to examine for whom and under what conditions tertiary school-based interventions are effective, and research suggests that starting early in development may be a particularly effective approach.

For decision makers, research has established the value of behavioral management approaches to address problem behavior, and we recommend that behavioral management be considered as part of covered services. However, additional research is needed to examine the effects of behavioral management interventions implemented in school settings, given various methodological limitations in the literature. Current limitations of research conducted in this area are related to generalizability, measurement, study design, and long-term outcomes. Also, as researchers have highlighted, interventions that are designed to address the behavioral needs of children in school settings should examine not only the treatment effects but also the conditions under which an intervention in a school setting is most effective ( 35 ). Factors such as symptom severity, school characteristics, and the child’s race, ethnicity, language (including language fluency of the parents), and sex are important moderating variables to examine when determining the effects of a school-based intervention. In addition, future research on behavioral management interventions should specifically examine the various treatment components included in the intervention to determine whether there are “key ingredients” associated with particular outcomes that are effective without commercial packaging or whether the specific combinations of practices contained in these intervention packages are required to produce the reported results.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Development of the Assessing the Evidence Base Series was supported by contracts HHSS283200700029I/HHSS28342002T, HHSS283200700006I/HHSS28342003T, and HHSS2832007000171/HHSS28300001T from 2010 through 2013 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The authors acknowledge the contributions of Paolo del Vecchio, M.S.W., Kevin Malone, B.A., and Suzanne Fields, M.S.W., from SAMHSA; John O’Brien, M.A., from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Garrett Moran, Ph.D., from Westat; and John Easterday, Ph.D., Linda Lee, Ph.D., Rosanna Coffey, Ph.D., and Tami Mark, Ph.D., from Truven Health Analytics. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of SAMHSA.

The authors report no competing interests.

1 Ensminger ME, Slusarcick AL : Paths to high school graduation or dropout: a longitudinal study of a first-grade cohort . Sociology of Education 65:95–113, 1992 Crossref , Google Scholar

2 Moffitt TE : Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy . Psychological Review 100:674–701, 1993 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

3 Loeber R, Farrington DP : Young children who commit crime: epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications . Development and Psychopathology 12:737–762, 2000 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 Snyder H : Epidemiology of official offending ; in Child Delinquents: Development, Intervention, and Service Needs . Edited by Loeber RFarrington DP . Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2001 Crossref , Google Scholar

5 Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, et al. : Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: a six-site, cross-national study . Developmental Psychology 39:222–245, 2003 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

6 Dodge KA, Pettit GS : A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence . Developmental Psychology 39:349–371, 2003 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

7 Bradshaw CP, Schaeffer CM, Petras H, et al. : Predicting negative life outcomes from early aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectories: gender differences in maladaptation across life domains . Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39:953–966, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

8 Carr EG, Horner RH, Turnbull AP, et al. : Positive Behavior Support for People With Developmental Disabilities: A Research Synthesis . Washington, DC, American Association on Mental Retardation, 1999 Google Scholar

9 Safran SP, Oswald K : Positive behavior supports: can schools reshape disciplinary practices? Exceptional Children 69:361–373, 2003 Crossref , Google Scholar

10 Gresham FM : Current status and future directions of school-based behavioral interventions . School Psychology Review 33:326–343, 2004 Google Scholar

11 Fisher W, Groff R, Roane H : Applied behavior analysis: history, principles, and basic methods ; in Handbook of Behavior Analysis . Edited by Fisher WPiazza CRoane H . New York, Guilford, 2011 Google Scholar

12 Bandura A : Social Learning Theory . Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1977 Google Scholar

13 Herschell A, Calzada E, Eyberg S, et al. : Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: new directions in research . Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 9:9–16, 2002 Crossref , Google Scholar

14 Brinkmeyer M, Eyberg S : Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for oppositional children ; in Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents . Edited by Kazdin AWeisz J . New York, Guilford, 2003 Google Scholar

15 Webster-Stratton CH, Reid M : The Incredible Years parents, teachers, and children training series: a multifaceted treatment approach for young children with conduct problems ; in Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents . Edited by Kazdin AEWeisz JR . New York, Guilford, 2003 Google Scholar

16 Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR : Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior . Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 37:215–237, 2008 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

17 Kutash K, Duchnowski A, Lynn N: School-Based Mental Health: An Empirical Guide for Decision-Makers. Tampa, University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Research and Training Center for Children’s Mental Health, 2006. Available at rtckids.fmhi.usf.edu/rtcpubs/study04/SBMHfull.pdf . Accessed Sept 6, 2013 Google Scholar

18 Educational environments for students with disabilities: applying positive behavioral support in schools; in Twenty-Second Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC, US Department of Education, 2000. Available at www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2000/chapter-3.pdf . Accessed Sept 6, 2013 Google Scholar

19 Goh AE, Bambara LM : Individualized positive behavior support in school settings: a meta-analysis . Remedial and Special Education 33:271–286, 2012 Crossref , Google Scholar

20 Sugai G, Horner R : The evolution of discipline practices: school-wide positive behavior supports . Child and Family Behavior Therapy 24:23–50, 2002 Crossref , Google Scholar

21 Sprick RS, Garrison M : Interventions: Evidence-Based Behavioral Strategies for Individual Students . Eugene, Ore, Pacific Northwest Publishing, 2008 Google Scholar

22 Sugai G, Horner RR : A promising approach for expanding and sustaining school-wide positive behavior support . School Psychology Review 35:245–259, 2006 Google Scholar

23 Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group : Fast track randomized controlled trial to prevent externalizing psychiatric disorders: findings from grades 3 to 9 . Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46:1250–1262, 2007 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

24 Pfiffner LJ, Yee Mikami A, Huang-Pollock C, et al. : A randomized, controlled trial of integrated home-school behavioral treatment for ADHD, predominantly inattentive type . Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46:1041–1050, 2007 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

25 Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K : A multilevel approach to family-centered prevention in schools: process and outcome . Addictive Behaviors 25:899–911, 2000 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

26 Dougherty RH, Lyman DR, George P, et al: Assessing the evidence base for behavioral health services: introduction to the series. Psychiatric Services, 2013; doi 10.1176/appi.ps.201300214 Google Scholar

27 Brestan EV, Eyberg SM : Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids . Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 27:180–189, 1998 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

28 Thomas R, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ : Behavioral outcomes of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: a review and meta-analysis . Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 35:475–495, 2007 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

29 Kaslow NJ, Broth MR, Smith CO, et al. : Family-based interventions for child and adolescent disorders . Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 38:82–100, 2012 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

30 Njoroge WF, Yang D : Evidence-based psychotherapies for preschool children with psychiatric disorders . Current Psychiatry Reports 14:121–128, 2012 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

31 Bagner DM, Sheinkopf SJ, Vohr BR, et al. : Parenting intervention for externalizing behavior problems in children born premature: an initial examination . Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 31:209–216, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

32 Berkovits MD, O’Brien KA, Carter CG, et al. : Early identification and intervention for behavior problems in primary care: a comparison of two abbreviated versions of parent-child interaction therapy . Behavior Therapy 41:375–387, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

33 Lau AS, Fung JJ, Ho LY, et al. : Parent training with high-risk immigrant Chinese families: a pilot group randomized trial yielding practice-based evidence . Behavior Therapy 42:413–426, 2011 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

34 Webster-Stratton CH, Reid MJ, Beauchaine T : Combining parent and child training for young children with ADHD . Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 40:191–203, 2011 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

35 Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group : A cognitive-ecological approach to preventing aggression in urban settings: initial outcomes for high-risk children . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 70:179–194, 2002 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

36 Iovannone R, Greenbaum PE, Wang W, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of the Prevent-Teach-Reinforce (PTR) tertiary intervention for students with problem behaviors: preliminary outcomes . Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 17:213–225, 2009 Crossref , Google Scholar

37 Forster M, Sundell K, Morris RJ, et al. : A randomized controlled trial of a standardized behavior management intervention for students with externalizing behavior . Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 20:169–183, 2012 Crossref , Google Scholar

38 Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K, Schneiger A, et al. : Preventing early adolescent substance use: a family-centered strategy for the public middle school . Prevention Science 3:191–201, 2002 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

39 Jones D, Godwin J, Dodge KA, et al. : Impact of the Fast Track prevention program on health services use by conduct-problem youth . Pediatrics 125:e130–e136, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

40 Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group : The effects of the Fast Track preventive intervention on the development of conduct disorder across childhood . Child Development 82:331–345, 2011 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

41 Scott TM, Bucalos A, Liaupsin C, et al. : Using functional behavior assessment in general education settings: making a case for effectiveness and efficiency . Behavioral Disorders 29:189–201, 2004 Crossref , Google Scholar

42 Simonsen B, Fairbanks S, Briesch A, et al. : Evidence-based practices in classroom management: considerations for research to practice . Education and Treatment of Children 31:351–380, 2008 Crossref , Google Scholar

43 Thompson AM : A systematic review of evidence-based interventions for students with challenging behaviors in school settings . Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work 8:304–322, 2011 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

44 McCabe K, Yeh M, Lau A, et al. : Parent-child interaction therapy for Mexican Americans: results of a pilot randomized clinical trial at follow-up . Behavior Therapy 43:606–618, 2012 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

45 Leung C, Tsang S, Heung K, et al. : Effectiveness of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) among Chinese families . Research on Social Work Practice 19:304–313, 2009 Crossref , Google Scholar

46 Fernandez MA, Butler AM, Eyberg SM : Treatment outcome for low socioeconomic status African American families in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: a pilot study . Child and Family Behavior Therapy 33:32–48, 2011 Crossref , Google Scholar

47 Webster-Stratton C : Parent training in low-income families: promoting parental engagement through a collaborative approach ; in Handbook of Child Abuse Research and Treatment . Edited by Lutzker J . New York, Plenum, 1998 Crossref , Google Scholar

48 Webster-Stratton C : Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: strengthening parenting competencies . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:715–730, 1998 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

49 McMenamy J, Sheldrick RC, Perrin EC : Early intervention in pediatrics offices for emerging disruptive behavior in toddlers . Journal of Pediatric Health Care 25:77–86, 2011 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

50 Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Hammond M : Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training . Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 33:105–124, 2004 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

- Effect of maternal eating disorders on mother‐infant quality of interaction, bonding and child temperament: A longitudinal study 5 December 2022 | European Eating Disorders Review, Vol. 31, No. 2

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Care: Contemporary Practices and Introduction of the 5S Model 11 March 2022 | Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Vol. 7, No. 4

- Relationships between Depression and Executive Functioning in Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Unpredictable Home Environment 2 April 2022 | Journal of Child and Family Studies, Vol. 31, No. 9

- Methods and Strategies for Reducing Seclusion and Restraint in Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Care 25 February 2021 | Psychiatric Quarterly, Vol. 93, No. 1

- A Retrospective Examination of the Impact of Pharmacotherapy on Parent–Child Interaction Therapy Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, Vol. 31, No. 10

- International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 16, No. 7

- International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 16, No. 12

- Childhood aggression: A synthesis of reviews and meta-analyses to reveal patterns and opportunities for prevention and intervention strategies Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Vol. 91

- Youth mental ill health and secondary school completion in Australia: time to act 6 July 2016 | Early Intervention in Psychiatry, Vol. 11, No. 4

- Psychosocial Interventions for Child Disruptive Behaviors: A Meta-analysis 1 November 2015 | Pediatrics, Vol. 136, No. 5

- The Lancet Psychiatry, Vol. 1, No. 5

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Health Risks in Adolescence

Unique biological and psychosocial changes occurring during adolescence, brain development, sexual orientation and gender identification, legal status, mental health and emotional well-being, morbidity from high-risk sexual activity, the adolescent medical home, recommendations, appendix: online resources, lead authors, committee on adolescence, 2017–2018, unique needs of the adolescent.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Elizabeth M. Alderman , Cora C. Breuner , COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE , Laura K. Grubb , Makia E. Powers , Krishna Upadhya , Stephenie B. Wallace; Unique Needs of the Adolescent. Pediatrics December 2019; 144 (6): e20193150. 10.1542/peds.2019-3150

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Adolescence is the transitional bridge between childhood and adulthood; it encompasses developmental milestones that are unique to this age group. Healthy cognitive, physical, sexual, and psychosocial development is both a right and a responsibility that must be guaranteed for all adolescents to successfully enter adulthood. There is consensus among national and international organizations that the unique needs of adolescents must be addressed and promoted to ensure the health of all adolescents. This policy statement outlines the special health challenges that adolescents face on their journey and transition to adulthood and provides recommendations for those who care for adolescents, their families, and the communities in which they live.

Adolescence, defined as 11 through 21 years of age, 1 is a critical period of development in a young person’s life, one filled with distinctive and pivotal biological, cognitive, emotional, and social changes. 2 The World Health Organization 3 ; the Office of Adolescent Health of the US Department of Health and Human Services 4 ; the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) 5 , 6 ; the Lancet , 7 with 4 international academic institutions 8 ; and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine 9 have called for a closer examination of the unique health needs of adolescents. In 2018, Nature devoted an issue to the advances in the science of adolescence and called for ongoing further study of this important population. 10 As a leader in adolescent health care, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is motivated to describe why adolescents are a unique and vulnerable population and why it is crucial that the AAP focus on adolescents’ health concerns to optimize healthy development during the transition to adulthood. Addressing the unique needs of adolescents with disabilities is outside the scope of this statement; several statements specific to this population are available at https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/collection/council-children-disabilities . In addition, specific guidance around the transition to adult health care is not covered in this statement; please refer to the list of transition resources at the end of this document.

The need for comprehensive health services for teenagers has been well documented since the 1990s. 11 – 13 The AAP advocates for the pediatrician to provide the medical home for adolescent primary care. 14 Other professional societies, such as the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and school-based health initiatives ( https://www.sbh4all.org/ ), recognize the unique needs of adolescents. These organizations recommend an increase in adolescent medicine training, along with the Accreditation Committee for Graduate Medical Education. The Accreditation Committee for Graduate Medical Education currently requires only 1 month of adolescent medicine training from a board-certified adolescent medicine specialist for all pediatric residency programs (adolescent medicine; [Core] IV.A.6.[b].[3].[a].[i]); there must be one educational unit). 15 The importance of addressing the physical and mental health of adolescents has become more evident, with investigators in recent studies pointing to the fact that unmet health needs during adolescence and in the transition to adulthood predict not only poor health outcomes as adults but also lower quality of life in adulthood. 16

A hallmark of adolescence is a gradual development toward autonomy and individual adult decision-making. However, adolescents are often faced with situations for which they may not be prepared, and many are likely to be involved in risk-taking behaviors, such as use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs and engaging in unprotected sex. Most recently, there is increased concern about the rise in electronic cigarette use among adolescence. 17 In fact, most health care visits by adolescents to their pediatricians or other health care providers are to seek treatment of conditions or injuries that could have been prevented if screened for and addressed at an earlier comprehensive visit. 18 Although some risk-taking behavior is considered normal in adolescence, engaging in certain types of risky behavior can have adverse and potentially long-term health consequences. The majority of mortality and morbidity during adolescence, which can be prevented, is attributable to unintentional injuries, suicide, and homicide. 19 Approximately 72% of deaths among adolescents are attributable to injuries from motor vehicle crashes, other unintentional and intentional injuries, injuries caused by firearms, injuries influenced by use of alcohol and illicit substances, homicide, or suicide. 20 , 21 These causes of death greatly surpass medical etiologies such as cancer, HIV infection, and heart disease in the United States and other industrialized nations. 21

The AAP Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents recommends a strength-based approach to screening and counseling around these behaviors that lead to mortality and morbidity in adolescents. 1 , 22 However, according to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, only 39% of adolescents received any type of preventive counseling during ambulatory visits. 23 Seventy-one percent of teenagers reported at least 1 potential health risk, yet only 37% of these teenagers reported discussing any of these risks with their pediatrician or primary care physician. Clearly, screening for and counseling around these high-risk behaviors needs to be improved. 24

New screening codes for depression, substance use, and alcohol and tobacco use as well as brief intervention services may provide opportunities to receive payment for the services pediatricians are providing to adolescents. These include 96127, brief emotional and behavioral assessment (eg, depression inventory, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder scale) with scoring and documentation, per standardized instrument, and 96150, health and behavior assessment (eg, health-focused clinical interview, behavioral observations, psychophysiological monitoring, health-oriented questionnaires). 25 However, it is important to recognize that coding for specific diagnoses may be challenging if the patient does not want his or her parent(s) to know the reasons for the clinical visit. Adolescent visits and documentation of visits are confidential to promote better access and to protect the rights of adolescents. 26

Another trend in the health status of adolescents (reflecting technological advances in pediatric medical care) is the increasing number of pediatric patients with chronic medical conditions and developmental challenges who enter adolescence. Adolescents with chronic conditions face developmental challenges similar to their healthy peers but may have special educational, vocational, and transitional concerns because of their medical issues. 27

The prevalence of chronic medical conditions and developmental and physical disabilities in adolescents is difficult to assess because of the variation of study methodologies and categorical versus noncategorical approaches to the epidemiology of chronic illness. 28 According to the National Survey of Children’s Health, funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services, almost 31% of adolescents have 1 moderate to severe chronic illness, such as asthma or a mental health condition. 29 Other common chronic illnesses include obesity, cancer, cardiac disease, HIV infection, spastic quadriplegia, and developmental disabilities. 30 – 32 One in 4 adolescents with chronic illness has at least 1 unmet health need that may affect physical growth and development, including puberty and overall health status as well as future adult health. 33

Within pediatric practice, integrating adolescent-centered, family-involved approaches into the care of adolescents as well as culturally competent and effective approaches (as outlined in Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents ) has the potential not only to identify threats to well-being but also to create a space to work with families to bolster opportunities for optimal development of all children. 1 When considering the health challenges adolescents face, it is imperative to take into account not only the ethnic and racial diversity of the adolescent population in the United States but also the social and ecologic factors (eg, socioeconomic status, family composition, parental education and engagement, neighborhood and school environment, religion, earlier childhood trauma and toxic stress, and access to health care).

The Search Foundation has conducted research that suggests that for minority youth, a positive ethnic identity is a critical spark for emergence of the required developmental assets to enable adolescents to develop into successful and contributing adults. 34 , 35 This theory is supported by a recent study in The Journal of Pediatrics that suggests minority youth are still prone to depression because of isolation and discrimination faced during adolescence while navigating neighborhood and school environments, even when they have educated and supportive parents. 36 African American male adolescents have the highest rates of mortality, followed by American Indian, white, Hispanic, and Asian American or Pacific Islander male adolescents, pointing to racial and ethnic disparities in adolescent health and the potential to achieve a healthy adulthood. 37

The AAP has previously published policy statements addressing the unique strengths and health disparities that exist for specific groups of adolescents, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth and those in the juvenile justice system, foster care, and the military. 38 – 42 Pediatricians must pay attention to how care is delivered to the increasingly diverse adolescent populations to prevent a decline in health status and increase in health care disparities.

Biological and psychosocial changes that occur during adolescence make this age group unique. Research describing the timing and physiology of puberty has been invaluable in revealing not only differences between racial groups but also between adolescents with different chronic conditions. 43 – 46

Puberty is the hallmark of physiologic progression from child to adult body habitus. Chronic conditions, such as obesity and intracranial lesions, or trauma may cause early puberty, which may put the adolescent at risk for engagement in higher-risk behaviors at an earlier age. 44 Delayed puberty is often a variant of normal development but may also be seen in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease, eating disorders, and chronic conditions that create malnutrition as well as adolescents who have undergone treatment of malignancies. Comorbid mental disease (eg, an eating disorder that causes delayed puberty) or medication for psychiatric illness that causes obesity, which may cause early puberty, can complicate optimal adolescent psychosocial development.

The work of Giedd 47 and others shows that brain development during adolescence is ongoing and affects behavior and health. Because of changes in signaling that relate to the reward system in which the brain motivates behavior and the continuing maturation of the parts of the brain that regulate impulse control, adolescents may have a propensity to be involved with high-risk behaviors and have heightened response to emotionally loaded situations. In addition, adverse childhood experiences can have an impact on brain development, affecting behaviors and health during adolescence. 48 During adolescence, there is a “pruning” of gray matter and synapses, which makes the brain more efficient. 47 White matter increases throughout adolescence, which allows the older adolescent and adult brain to conduct more-complex cognitive tasks and adaptive behavior. 49

Increasingly, studies show that the adolescent brain responds to alcohol and illicit substances differently than adults. 50 , 51 This difference may explain the increased risk of binge drinking as well as greater untoward cognitive effects of alcohol and marijuana.

Sexual (and gender) development is a process that starts early in childhood and involves negotiating and experimenting with identity, relationships, and roles. In early adolescence, people begin to recognize or become aware of their sexual orientation. 52 , 53

However, some adolescents are still unsure of their sexual attractions, and others struggle with their known sexual attraction. Adolescence is a time of identity formation and experimentation, so labels that one uses for their sexual orientation (eg, gay, straight, bisexual, etc) often do not correlate to actual sexual behaviors and partners. Sexual orientation and behaviors should be assessed by the pediatrician without making assumptions. Adolescents should be allowed to apply and explain the labels they choose to use for sexuality and gender using open-ended questions. 54 – 56

Sexual minority adolescents may engage in heterosexual practices, and heterosexual adolescents may engage in same-sex sexual activity. Depending on their specific behaviors and the gender of various partners, all sexually active adolescents may be at risk for sexually transmitted infections and unplanned pregnancy. Sexual minority youth are at higher risk of sexually transmitted infections and unplanned pregnancy, often because they do not receive education that applies to their sexual behaviors and are less likely to be screened appropriately ( http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/disparities/smy.htm ). 57 , 58

Sexual minority and transgender youth, because of the stigma they face, are also at higher risk of mental health problems, including depression and suicidality, altered body image, and substance use. 38

There is strong evidence that when sexual minority and transgender youth feel they cannot express their true selves, they go underground by either hiding or denying their attractions and identity. 59 When this is combined with reinforcing parental rejection, bullying, etc, it is believed to lead to internalization, low self-esteem, and ultimately, depression and suicide. 59 Using an explanation like this places the problem on the societal context, not the adolescent or his or her identity. 38 , 39 , 60 , 61

A relatively higher proportion of homeless adolescents are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning youth. 61 They leave their family homes because of abuse or having been thrown out. These adolescents are at high risk for victimization and often need to engage in unsafe sexual practices to provide themselves food and shelter. 61

Mental health problems may become more pronounced when sexual minority teenagers come out during adolescence to unsupportive family members and friends or health care providers. 38 These youth are more likely to experience violence both in their homes and in their schools and communities. Studies have shown that sexual minority youth reveal higher rates of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit substance use. 62

Most adolescents identify by and express a gender that conforms to their anatomic sex. However, some adolescents experience gender dysphoria with their anatomic sex when entering puberty. As they consider transgender options, they are at an increased risk of mental or emotional health problems, including depression and suicidality, victimization and violence, eating disorders, substance use, and unaccepting or intolerant family members and peers. Crucial to the successful navigation of gender dysphoria issues are health care providers who can assist transgender youth and families to achieve safe, healthy transitioning both in the postponement of puberty, when indicated, and in transitioning to preferred gender with psychosocial and behavioral support. 59

Adolescence heralds a change of legal status, in which the age of 18 or 19 years transforms legal status from minors to adults with full legal privileges and obligations related to health care. However, certain states afford minors the right to confidentiality and consent to or for reproductive and mental health and substance use treatment confidential health services. 26 , 63 Generally, minors may receive confidential screening and care for sexually transmitted infections in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. However, accessing contraception to prevent unwanted pregnancy as well as the ability to self-consent to pregnancy options counseling, prenatal care, and termination of pregnancy vary between states. 64 These discrepancies also exist in accessing outpatient mental health and substance use services. Many adolescents in need of these services do not know they may have the right to access them on their own and may avoid interaction with the health care system to assist with reproductive and mental health concerns. 16 Delaying such care leads to adverse health outcomes. 16 A recent survey confirms that adolescents value private time with their health care providers, with confidentiality assurances by health care providers. 65 The need for office policies in negotiating private time was suggested. Moreover, health care providers reported needing more education in the provision of confidential services. 66 Adolescents in foster care may also be limited in their autonomous access to confidential services, which varies state to state. 41 In certain states, pregnant and parenting adolescents may have the right to consent for their care and the care of their child ( https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-rights-parents , https://www.schoolhouseconnection.org/state-laws-on-minor-consent-for-routine-medical-care/ ). Few adolescents are considered emancipated minors and, thereby, entitled to all legal privileges of adults. 67

Mental health and emotional well-being, in combination with issues pertaining to sexual and reproductive health, violence and unintentional injury, substance use, eating disorders, and obesity, create potential challenges to adolescents’ healthy emotional and physical development. 68 Approximately 20% of adolescents have a diagnosable mental health disorder. 69 Many mental health disorders present initially during adolescence. Twenty-five percent of adults with mood disorder had their first major depressive episode during adolescence. 70

Suicide is the second leading cause of death in adolescents, resulting in more than 5700 deaths in 2016. 71 Between 2007 and 2016, the overall suicide rate for children and adolescents ages 10 to 19 years increased by 56%. 71 Older adolescents (15–19 years of age) are at an increased risk of suicide, with a rate of 5 in 100 000 for girls and 20 in 100 000 for boys. 71 According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey of high school students, 7.4% of high school students attempted suicide in the last 12 months, and 13.6% made a suicide plan. 72 Adolescents with parents in the military were at increased risk of suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR]: 1.43; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.37–1.49), making a plan to harm themselves (OR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.06–1.34), attempting suicide (OR: 1.67; 95% CI: 1.43–1.95), and an attempted suicide that required medical treatment. 73

Eating disorders typically present in the adolescent years. Although the incidence of eating disorders is low compared with depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems, these problems are often comorbid with eating disorders. 74 Moreover, the incidence of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other disordered eating is becoming more prevalent in formerly obese teenagers, male teenagers, and teenagers from lower socioeconomic groups. 75 – 77

Teenagers with mental health issues may have subsequent poor school performance, school dropout, difficult family relationships, involvement in the juvenile justice system, substance use, and high-risk sexual behaviors. 78 Almost 70% of youth in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosed mental health disorder. 79 , 80

Rates of serious mental health disorders among homeless youth range from 19% to 50%. 81 , 82 Homeless youth have a high need for treatment but rarely use formal treatment programs for medical, mental, and substance use services. 81 Confidentiality is also an issue for adolescents, as evidenced by the fact that in adolescents to whom confidentiality is not assured, there is a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts. 83 There is a paucity of adequately trained mental health professionals to care for adolescents with these mental health challenges. 84 In addition, coverage for mental health services by insurance plans can be variable. 78

Multiple factors, including the increase in use of long-acting reversible contraception, have resulted in the teenage pregnancy rate decreasing in the United States over the past 20 years. 85 , 86 However, pregnancy still contributes to delays in educational and career success for adolescents. Moreover, pregnant teenagers are more likely to delay seeking medical care, putting them at risk for pregnancy-related health problems and putting their children at risk for prematurity and other negative birth outcomes. 87

Adolescents continue to have the highest rates of sexually transmitted infections (eg, gonorrhea and Chlamydia ). 88 Although screening most sexually active adolescents for Chlamydia infection is covered by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Pub L No. 111–148 [2010]) and recommended by the AAP Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents , adolescent concerns about billing and confidentiality are obstacles to medical screening. 1 , 89 Pediatricians can refer to AAP guidance to find appropriate codes for payment for providing adolescent health services ( https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/coding_factsheet_adolescenthealth.pdf ).

Consideration of the unique health risks as well as the biological and psychosocial elements of adolescence allows the AAP-endorsed patient-centered medical home (PCMH) to serve as an ideal conceptual framework by which a primary care practice can maximize the quality, efficiency, and patient experience of care. In 2007, the AAP joined the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Osteopathic Association to endorse the “Joint Principals of the Patient-Centered Medical Home,” which describes 7 core characteristics: (1) personal physician for every patient; (2) physician-directed medical practice; (3) whole person orientation; (4) care is coordinated and/or integrated; (5) quality and safety are hallmarks of PCMH care; (6) enhanced access to care; and (7) appropriate payment for providing PCMH care. 90 The AAP, American Academy of Family Physicians, and American College of Physicians assert that optimal health care is achieved when each person, at every age, receives developmentally appropriate care. 91 Pediatricians provide quality adolescent care when they maintain relationships with families and with their patients and, thus, help patients develop autonomy, responsibility, and an adult identity. 92 Issues unique to adolescence to consider within the PCMH model include the following: adolescent-oriented developmentally appropriate care, which may require longer appointment times; confidentiality of health care visits, health records, billing, and the location where adolescents receive care; providers who offer such care; and the transition to adult care. 91 , 93 Moreover, using a strengths-based approach in the care of adolescents, as well as capitalizing on resiliency, is instrumental to maintaining the health of the individual adolescent. 94