Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Creative Nonfiction: An Overview

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource provides an introduction to creative nonfiction, including an overview of the genre and an explanation of major sub-genres.

The Creative Nonfiction (CNF) genre can be rather elusive. It is focused on story, meaning it has a narrative plot with an inciting moment, rising action, climax and denoument, just like fiction. However, nonfiction only works if the story is based in truth, an accurate retelling of the author’s life experiences. The pieces can vary greatly in length, just as fiction can; anything from a book-length autobiography to a 500-word food blog post can fall within the genre.

Additionally, the genre borrows some aspects, in terms of voice, from poetry; poets generally look for truth and write about the realities they see. While there are many exceptions to this, such as the persona poem, the nonfiction genre depends on the writer’s ability to render their voice in a realistic fashion, just as poetry so often does. Writer Richard Terrill, in comparing the two forms, writes that the voice in creative nonfiction aims “to engage the empathy” of the reader; that, much like a poet, the writer uses “personal candor” to draw the reader in.

Creative Nonfiction encompasses many different forms of prose. As an emerging form, CNF is closely entwined with fiction. Many fiction writers make the cross-over to nonfiction occasionally, if only to write essays on the craft of fiction. This can be done fairly easily, since the ability to write good prose—beautiful description, realistic characters, musical sentences—is required in both genres.

So what, then, makes the literary nonfiction genre unique?

The first key element of nonfiction—perhaps the most crucial thing— is that the genre relies on the author’s ability to retell events that actually happened. The talented CNF writer will certainly use imagination and craft to relay what has happened and tell a story, but the story must be true. You may have heard the idiom that “truth is stranger than fiction;” this is an essential part of the genre. Events—coincidences, love stories, stories of loss—that may be expected or feel clichéd in fiction can be respected when they occur in real life .

A writer of Creative Nonfiction should always be on the lookout for material that can yield an essay; the world at-large is their subject matter. Additionally, because Creative Nonfiction is focused on reality, it relies on research to render events as accurately as possible. While it’s certainly true that fiction writers also research their subjects (especially in the case of historical fiction), CNF writers must be scrupulous in their attention to detail. Their work is somewhat akin to that of a journalist, and in fact, some journalism can fall under the umbrella of CNF as well. Writer Christopher Cokinos claims, “done correctly, lived well, delivered elegantly, such research uncovers not only facts of the world, but reveals and shapes the world of the writer” (93). In addition to traditional research methods, such as interviewing subjects or conducting database searches, he relays Kate Bernheimer’s claim that “A lifetime of reading is research:” any lived experience, even one that is read, can become material for the writer.

The other key element, the thing present in all successful nonfiction, is reflection. A person could have lived the most interesting life and had experiences completely unique to them, but without context—without reflection on how this life of experiences affected the writer—the reader is left with the feeling that the writer hasn’t learned anything, that the writer hasn’t grown. We need to see how the writer has grown because a large part of nonfiction’s appeal is the lessons it offers us, the models for ways of living: that the writer can survive a difficult or strange experience and learn from it. Sean Ironman writes that while “[r]eflection, or the second ‘I,’ is taught in every nonfiction course” (43), writers often find it incredibly hard to actually include reflection in their work. He expresses his frustration that “Students are stuck on the idea—an idea that’s not entirely wrong—that readers need to think” (43), that reflecting in their work would over-explain the ideas to the reader. Not so. Instead, reflection offers “the crucial scene of the writer writing the memoir” (44), of the present-day writer who is looking back on and retelling the past. In a moment of reflection, the author steps out of the story to show a different kind of scene, in which they are sitting at their computer or with their notebook in some quiet place, looking at where they are now, versus where they were then; thinking critically about what they’ve learned. This should ideally happen in small moments, maybe single sentences, interspersed throughout the piece. Without reflection, you have a collection of scenes open for interpretation—though they might add up to nothing.

What is creative nonfiction? Despite its slightly enigmatic name, no literary genre has grown quite as quickly as creative nonfiction in recent decades. Literary nonfiction is now well-established as a powerful means of storytelling, and bookstores now reserve large amounts of space for nonfiction, when it often used to occupy a single bookshelf.

Like any literary genre, creative nonfiction has a long history; also like other genres, defining contemporary CNF for the modern writer can be nuanced. If you’re interested in writing true-to-life stories but you’re not sure where to begin, let’s start by dissecting the creative nonfiction genre and what it means to write a modern literary essay.

What Creative Nonfiction Is

Creative nonfiction employs the creative writing techniques of literature, such as poetry and fiction, to retell a true story.

How do we define creative nonfiction? What makes it “creative,” as opposed to just “factual writing”? These are great questions to ask when entering the genre, and they require answers which could become literary essays themselves.

In short, creative nonfiction (CNF) is a form of storytelling that employs the creative writing techniques of literature, such as poetry and fiction, to retell a true story. Creative nonfiction writers don’t just share pithy anecdotes, they use craft and technique to situate the reader into their own personal lives. Fictional elements, such as character development and narrative arcs, are employed to create a cohesive story, but so are poetic elements like conceit and juxtaposition.

The CNF genre is wildly experimental, and contemporary nonfiction writers are pushing the bounds of literature by finding new ways to tell their stories. While a CNF writer might retell a personal narrative, they might also focus their gaze on history, politics, or they might use creative writing elements to write an expository essay. There are very few limits to what creative nonfiction can be, which is what makes defining the genre so difficult—but writing it so exciting.

Different Forms of Creative Nonfiction

From the autobiographies of Mark Twain and Benvenuto Cellini, to the more experimental styles of modern writers like Karl Ove Knausgård, creative nonfiction has a long history and takes a wide variety of forms. Common iterations of the creative nonfiction genre include the following:

Also known as biography or autobiography, the memoir form is probably the most recognizable form of creative nonfiction. Memoirs are collections of memories, either surrounding a single narrative thread or multiple interrelated ideas. The memoir is usually published as a book or extended piece of fiction, and many memoirs take years to write and perfect. Memoirs often take on a similar writing style as the personal essay does, though it must be personable and interesting enough to encourage the reader through the entire book.

Personal Essay

Personal essays are stories about personal experiences told using literary techniques.

When someone hears the word “essay,” they instinctively think about those five paragraph book essays everyone wrote in high school. In creative nonfiction, the personal essay is much more vibrant and dynamic. Personal essays are stories about personal experiences, and while some personal essays can be standalone stories about a single event, many essays braid true stories with extended metaphors and other narratives.

Personal essays are often intimate, emotionally charged spaces. Consider the opening two paragraphs from Beth Ann Fennelly’s personal essay “ I Survived the Blizzard of ’79. ”

We didn’t question. Or complain. It wouldn’t have occurred to us, and it wouldn’t have helped. I was eight. Julie was ten.

We didn’t know yet that this blizzard would earn itself a moniker that would be silk-screened on T-shirts. We would own such a shirt, which extended its tenure in our house as a rag for polishing silver.

The word “essay” comes from the French “essayer,” which means “to try” or “attempt.” The personal essay is more than just an autobiographical narrative—it’s an attempt to tell your own history with literary techniques.

Lyric Essay

The lyric essay contains similar subject matter as the personal essay, but is much more experimental in form.

The lyric essay contains similar subject matter as the personal essay, with one key distinction: lyric essays are much more experimental in form. Poetry and creative nonfiction merge in the lyric essay, challenging the conventional prose format of paragraphs and linear sentences.

The lyric essay stands out for its unique writing style and sentence structure. Consider these lines from “ Life Code ” by J. A. Knight:

The dream goes like this: blue room of water. God light from above. Child’s fist, foot, curve, face, the arc of an eye, the symmetry of circles… and then an opening of this body—which surprised her—a movement so clean and assured and then the push towards the light like a frog or a fish.

What we get is language driven by emotion, choosing an internal logic rather than a universally accepted one.

Lyric essays are amazing spaces to break barriers in language. For example, the lyricist might write a few paragraphs about their story, then examine a key emotion in the form of a villanelle or a ghazal. They might decide to write their entire essay in a string of couplets or a series of sonnets, then interrupt those stanzas with moments of insight or analysis. In the lyric essay, language dictates form. The successful lyricist lets the words arrange themselves in whatever format best tells the story, allowing for experimental new forms of storytelling.

Literary Journalism

Much more ambiguously defined is the idea of literary journalism. The idea is simple: report on real life events using literary conventions and styles. But how do you do this effectively, in a way that the audience pays attention and takes the story seriously?

You can best find examples of literary journalism in more “prestigious” news journals, such as The New Yorker , The Atlantic , Salon , and occasionally The New York Times . Think pieces about real world events, as well as expository journalism, might use braiding and extended metaphors to make readers feel more connected to the story. Other forms of nonfiction, such as the academic essay or more technical writing, might also fall under literary journalism, provided those pieces still use the elements of creative nonfiction.

Consider this recently published article from The Atlantic : The Uncanny Tale of Shimmel Zohar by Lawrence Weschler. It employs a style that’s breezy yet personable—including its opening line.

So I first heard about Shimmel Zohar from Gravity Goldberg—yeah, I know, but she insists it’s her real name (explaining that her father was a physicist)—who is the director of public programs and visitor experience at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, in San Francisco.

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Common Elements and Techniques

What separates a general news update from a well-written piece of literary journalism? What’s the difference between essay writing in high school and the personal essay? When nonfiction writers put out creative work, they are most successful when they utilize the following elements.

Just like fiction, nonfiction relies on effective narration. Telling the story with an effective plot, writing from a certain point of view, and using the narrative to flesh out the story’s big idea are all key craft elements. How you structure your story can have a huge impact on how the reader perceives the work, as well as the insights you draw from the story itself.

Consider the first lines of the story “ To the Miami University Payroll Lady ” by Frenci Nguyen:

You might not remember me, but I’m the dark-haired, Texas-born, Asian-American graduate student who visited the Payroll Office the other day to complete direct deposit and tax forms.

Because the story is written in second person, with the reader experiencing the story as the payroll lady, the story’s narration feels much more personal and important, forcing the reader to evaluate their own personal biases and beliefs.

Observation

Telling the story involves more than just simple plot elements, it also involves situating the reader in the key details. Setting the scene requires attention to all five senses, and interpersonal dialogue is much more effective when the narrator observes changes in vocal pitch, certain facial expressions, and movements in body language. Essentially, let the reader experience the tiny details – we access each other best through minutiae.

The story “ In Transit ” by Erica Plouffe Lazure is a perfect example of storytelling through observation. Every detail of this flash piece is carefully noted to tell a story without direct action, using observations about group behavior to find hope in a crisis. We get observation when the narrator notes the following:

Here at the St. Thomas airport in mid-March, we feel the urgency of the transition, the awareness of how we position our bodies, where we place our luggage, how we consider for the first time the numbers of people whose belongings are placed on the same steel table, the same conveyor belt, the same glowing radioactive scan, whose IDs are touched by the same gloved hand[.]

What’s especially powerful about this story is that it is written in a single sentence, allowing the reader to be just as overwhelmed by observation and context as the narrator is.

We’ve used this word a lot, but what is braiding? Braiding is a technique most often used in creative nonfiction where the writer intertwines multiple narratives, or “threads.” Not all essays use braiding, but the longer a story is, the more it benefits the writer to intertwine their story with an extended metaphor or another idea to draw insight from.

“ The Crush ” by Zsofia McMullin demonstrates braiding wonderfully. Some paragraphs are written in first person, while others are written in second person.

The following example from “The Crush” demonstrates braiding:

Your hair is still wet when you slip into the booth across from me and throw your wallet and glasses and phone on the table, and I marvel at how everything about you is streamlined, compact, organized. I am always overflowing — flesh and wants and a purse stuffed with snacks and toy soldiers and tissues.

The author threads these narratives together by having both people interact in a diner, yet the reader still perceives a distance between the two threads because of the separation of “I” and “you” pronouns. When these threads meet, briefly, we know they will never meet again.

Speaking of insight, creative nonfiction writers must draw novel conclusions from the stories they write. When the narrator pauses in the story to delve into their emotions, explain complex ideas, or draw strength and meaning from tough situations, they’re finding insight in the essay.

Often, creative writers experience insight as they write it, drawing conclusions they hadn’t yet considered as they tell their story, which makes creative nonfiction much more genuine and raw.

The story “ Me Llamo Theresa ” by Theresa Okokun does a fantastic job of finding insight. The story is about the history of our own names and the generations that stand before them, and as the writer explores her disconnect with her own name, she recognizes a similar disconnect in her mother, as well as the need to connect with her name because of her father.

The narrator offers insight when she remarks:

I began to experience a particular type of identity crisis that so many immigrants and children of immigrants go through — where we are called one name at school or at work, but another name at home, and in our hearts.

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: the 5 R’s

CNF pioneer Lee Gutkind developed a very system called the “5 R’s” of creative nonfiction writing. Together, the 5 R’s form a general framework for any creative writing project. They are:

- Write about r eal life: Creative nonfiction tackles real people, events, and places—things that actually happened or are happening.

- Conduct extensive r esearch: Learn as much as you can about your subject matter, to deepen and enrich your ability to relay the subject matter. (Are you writing about your tenth birthday? What were the newspaper headlines that day?)

- (W) r ite a narrative: Use storytelling elements originally from fiction, such as Freytag’s Pyramid , to structure your CNF piece’s narrative as a story with literary impact rather than just a recounting.

- Include personal r eflection: Share your unique voice and perspective on the narrative you are retelling.

- Learn by r eading: The best way to learn to write creative nonfiction well is to read it being written well. Read as much CNF as you can, and observe closely how the author’s choices impact you as a reader.

You can read more about the 5 R’s in this helpful summary article .

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Give it a Try!

Whatever form you choose, whatever story you tell, and whatever techniques you write with, the more important aspect of creative nonfiction is this: be honest. That may seem redundant, but often, writers mistakenly create narratives that aren’t true, or they use details and symbols that didn’t exist in the story. Trust us – real life is best read when it’s honest, and readers can tell when details in the story feel fabricated or inflated. Write with honesty, and the right words will follow!

Ready to start writing your creative nonfiction piece? If you need extra guidance or want to write alongside our community, take a look at the upcoming nonfiction classes at Writers.com. Now, go and write the next bestselling memoir!

Sean Glatch

Thank you so much for including these samples from Hippocampus Magazine essays/contributors; it was so wonderful to see these pieces reflected on from the craft perspective! – Donna from Hippocampus

Absolutely, Donna! I’m a longtime fan of Hippocampus and am always astounded by the writing you publish. We’re always happy to showcase stunning work 🙂

[…] Source: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/a-complete-guide-to-writing-creative-nonfiction#5-creative-nonfiction-writing-promptshttps://writers.com/what-is-creative-nonfiction […]

So impressive

Thank you. I’ve been researching a number of figures from the 1800’s and have come across a large number of ‘biographies’ of figures. These include quoted conversations which I knew to be figments of the author and yet some works are lauded as ‘histories’.

excellent guidelines inspiring me to write CNF thank you

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

University Writing Center

University writing center blog, on writing creative nonfiction, part 1: what is creative nonfiction.

By: Nathan M.

From our marvelous consultant Nathan, here is the first of three installments on writing creative nonfiction!

When I first started writing creative nonfiction, I had the same anxieties that all my classmates seemed to: I didn’t think that my life was interesting enough that anyone would want to hear about it. I was a sophomore in college the first time I took a creative nonfiction class, and knew just enough about the world to understand how much I didn’t know. How could I possibly write essays about my life? The man who invented the word “essay,” one of the founding minds of the genre, Michel de Montaigne, shared similar misgivings ; in 1580, he said “I am myself the matter of my book…You would be unreasonable to spend your leisure on so frivolous and vain a subject.” So why did I feel so drawn to write in this genre?

One of my creative writing professors told me to “stick the finger into the wound” and write whatever what came out. I wrote like this for a while, but eventually concluded that if picking open old wounds is what made me interesting, then I’d much rather be boring. At the same time though, I was at a loss: if not the things that have happened to me, what was possibly interesting enough to write an essay about?

The more creative nonfiction I read, the more I understood that “creative nonfiction” is not just a fancy term for “memoir.” Memoir is a type of creative nonfiction, certainly, but Montaigne’s assessment of the form was somewhat reductive. Creative nonfiction encompasses everything that fiction isn’t ; anything that’s true about the world, structured in any form. It can lean so heavily into lyricism that it’s rubbing shoulders with poetry, as James Agee Knoxville’s “Summer of 1915” does, or it can tell the intimate details of someone’s life in a largely narrative form—and there’s a seemingly endless expanse between these two extremes to explore.

The thing that really set me free in the creative nonfiction world, however, was understanding that creative nonfiction doesn’t have to be about me; it merely has to be true. For example, Roxanne Gay’s acclaimed essay collection Bad Feminist is framed by her experiences, but it’s more broadly about what it means to be a feminist than it is about her as an individual. David Sedaris’s humorous essays are notable because of the perspective he brings to everyday events rather than because of the events themselves. Even Montaigne, whose reductive definition of creative nonfiction had at first terrified me, wrote essays that reached far outside the self. His famous essay “Of Cannibals” is a grappling with morality and social norms; it’s about society, about humanity, and not at all about Montaigne’s life.

Even works of creative nonfiction that fall into the memoir category don’t have to stick to one linear style of storytelling. Carmen Maria Machado’s 2019 collection In The Dream House is a series of essays in different styles that all point back to her abusive relationship with her ex in different ways. She incorporates aspects of literary criticism and poetry. She writes about Dr. Who and queer villains in movies and a number of other things, and she combines it flawlessly with personal narrative. Francisco Cantú’s The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border tells the story of his time as a border patrol agent and what compelled him to leave, but it also works in surreal lyrical segments about his nightmares.

Creative nonfiction is just as much about how the story is told as it is about what the story is. It can be as much or as little about yourself as you want it to be. I’ve come to understand this genre not as another box to fit into but rather as the open space between poetry, fiction, literary criticism, and every other kind of writing I can think of. Anyone, regardless of what kind of life they’ve lived or what kind of writing they prefer, can make a space for themselves in creative nonfiction. The only restriction to the genre is that it has to have some foundation in truth—if not in lived experience, at least in things that are real, that have happened.

Stay tuned for part two, where I’ll talk more specifically about determining what “truth” means in creative nonfiction!

Catch Nathan’s next installment on creative nonfiction, coming February 25th!

Featured Story

Writing center blog.

- Three Commonalities of any Writing Center Session – Part 2

- Three Commonalities of any Writing Center Session – Part 1

- Delayed Writers: What Students Can Do to Get Back into Writing

- 10 Reasons Why You Should Schedule an Appointment at the UWC

- Scheduling a UWC Appointment with Ease

- Announcements

- Conferences

- Consultant Spotlight

- Creative Writing

- Difficult Conversations

- Graduate Writing

- Intersectionality

- multimodal composing

- Neurodiversity

- Opportunity

- Retrospectives

- Uncategorized

- women's history month

- Writing Center Work

- Writing Strategies

- November 2023

- November 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- September 2021

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 20, 2023

Creative Nonfiction: How to Spin Facts into Narrative Gold

Creative nonfiction is a genre of creative writing that approaches factual information in a literary way. This type of writing applies techniques drawn from literary fiction and poetry to material that might be at home in a magazine or textbook, combining the craftsmanship of a novel with the rigor of journalism.

Here are some popular examples of creative nonfiction:

- The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang

- Intimations by Zadie Smith

- Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

- Translating Myself and Others by Jhumpa Lahiri

- The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

- I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino

Creative nonfiction is not limited to novel-length writing, of course. Popular radio shows and podcasts like WBEZ’s This American Life or Sarah Koenig’s Serial also explore audio essays and documentary with a narrative approach, while personal essays like Nora Ephron’s A Few Words About Breasts and Mariama Lockington’s What A Black Woman Wishes Her Adoptive White Parents Knew also present fact with fiction-esque flair.

Writing short personal essays can be a great entry point to writing creative nonfiction. Think about a topic you would like to explore, perhaps borrowing from your own life, or a universal experience. Journal freely for five to ten minutes about the subject, and see what direction your creativity takes you in. These kinds of exercises will help you begin to approach reality in a more free flowing, literary way — a muscle you can use to build up to longer pieces of creative nonfiction.

If you think you’d like to bring your writerly prowess to nonfiction, here are our top tips for creating compelling creative nonfiction that’s as readable as a novel, but as illuminating as a scholarly article.

Write a memoir focused on a singular experience

Humans love reading about other people’s lives — like first-person memoirs, which allow you to get inside another person’s mind and learn from their wisdom. Unlike autobiographies, memoirs can focus on a single experience or theme instead of chronicling the writers’ life from birth onward.

For that reason, memoirs tend to focus on one core theme and—at least the best ones—present a clear narrative arc, like you would expect from a novel. This can be achieved by selecting a singular story from your life; a formative experience, or period of time, which is self-contained and can be marked by a beginning, a middle, and an end.

When writing a memoir, you may also choose to share your experience in parallel with further research on this theme. By performing secondary research, you’re able to bring added weight to your anecdotal evidence, and demonstrate the ways your own experience is reflective (or perhaps unique from) the wider whole.

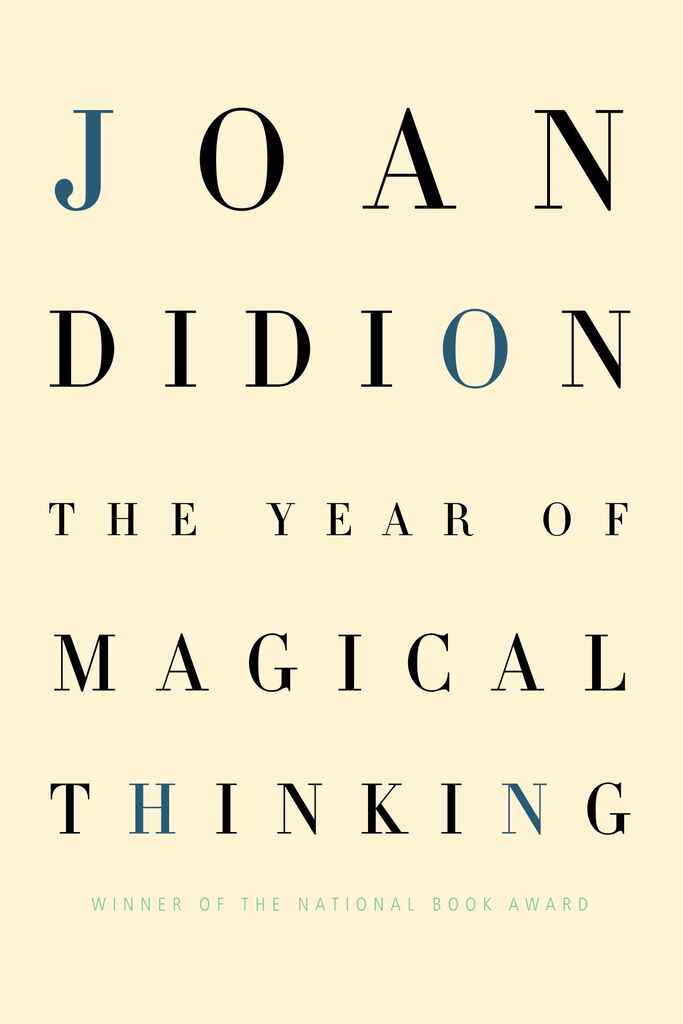

Example: The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking , for example, interweaves the author’s experience of widowhood with sociological research on grief. Chronicling the year after her husband’s unexpected death, and the simultaneous health struggles of their daughter, The Year of Magical Thinking is a poignant personal story, layered with universal insight into what it means to lose someone you love. The result is the definitive exploration of bereavement — and a stellar example of creative nonfiction done well.

📚 Looking for more reading recommendations? Check out our list of the best memoirs of the last century .

Tip: What you cut out is just as important as what you keep

When writing a memoir that is focused around a singular theme, it’s important to be selective in what to include, and what to leave out. While broader details of your life may be helpful to provide context, remember to resist the impulse to include too much non-pertinent backstory. By only including what is most relevant, you are able to provide a more focused reader experience, and won’t leave readers guessing what the significance of certain non-essential anecdotes will be.

💡 For more memoir-planning tips, head over to our post on outlining memoirs .

Of course, writing a memoir isn’t the only form of creative nonfiction that lets you tap into your personal life — especially if there’s something more explicit you want to say about the world at large… which brings us onto our next section.

Pen a personal essay that has something bigger to say

Personal essays condense the first-person focus and intimacy of a memoir into a tighter package — tunneling down into a specific aspect of a theme or narrative strand within the author’s personal experience.

Often involving some element of journalistic research, personal essays can provide examples or relevant information that comes from outside the writer’s own experience. This can take the form of other people’s voices quoted in the essay, or facts and stats. By combining lived experiences with external material, personal essay writers can reach toward a bigger message, telling readers something about human behavior or society instead of just letting them know the writer better.

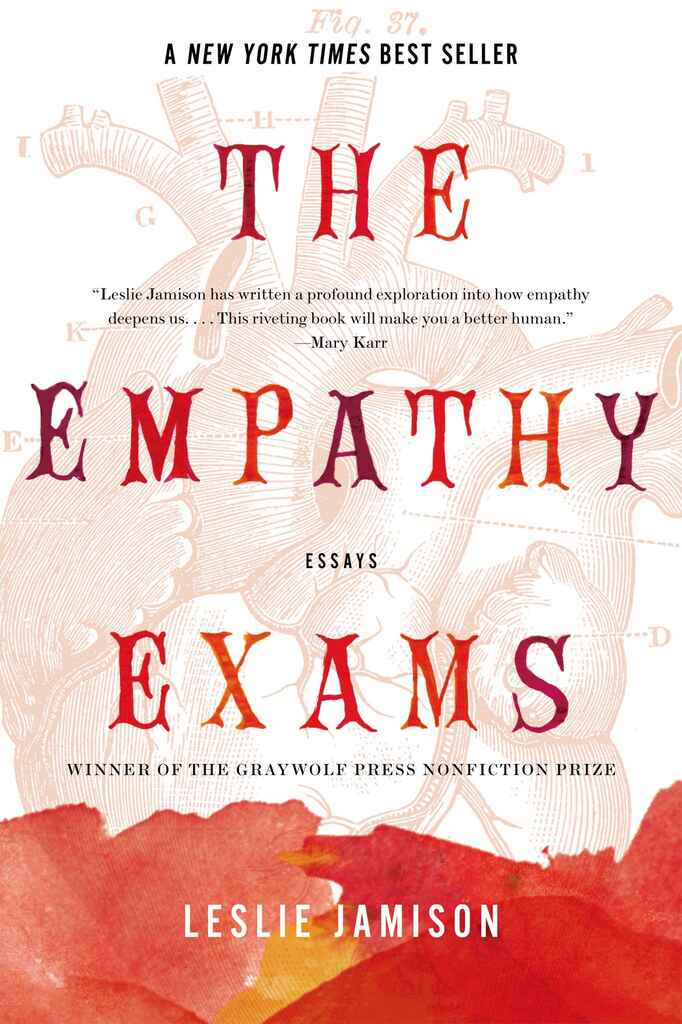

Example: The Empathy Exams by Leslie Jamison

Leslie Jamison's widely acclaimed collection The Empathy Exams tackles big questions (Why is pain so often performed? Can empathy be “bad”?) by grounding them in the personal. While Jamison draws from her own experiences, both as a medical actor who was paid to imitate pain, and as a sufferer of her own ailments, she also reaches broader points about the world we live in within each of her essays.

Whether she’s talking about the justice system or reality TV, Jamison writes with both vulnerability and poise, using her lived experience as a jumping-off point for exploring the nature of empathy itself.

Tip: Try to show change in how you feel about something

Including external perspectives, as we’ve just discussed above, will help shape your essay, making it meaningful to other people and giving your narrative an arc.

Ultimately, you may be writing about yourself, but readers can read what they want into it. In a personal narrative, they’re looking for interesting insights or realizations they can apply to their own understanding of their lives or the world — so don’t lose sight of that. As the subject of the essay, you are not so much the topic as the vehicle for furthering a conversation.

Often, there are three clear stages in an essay:

- Initial state

- Encounter with something external

- New, changed state, and conclusions

By bringing readers through this journey with you, you can guide them to new outlooks and demonstrate how your story is still relevant to them.

Had enough of writing about your own life? Let’s look at a form of creative nonfiction that allows you to get outside of yourself.

Tell a factual story as though it were a novel

The form of creative nonfiction that is perhaps closest to conventional nonfiction is literary journalism. Here, the stories are all fact, but they are presented with a creative flourish. While the stories being told might comfortably inhabit a newspaper or history book, they are presented with a sense of literary significance, and writers can make use of literary techniques and character-driven storytelling.

Unlike news reporters, literary journalists can make room for their own perspectives: immersing themselves in the very action they recount. Think of them as both characters and narrators — but every word they write is true.

If you think literary journalism is up your street, think about the kinds of stories that capture your imagination the most, and what those stories have in common. Are they, at their core, character studies? Parables? An invitation to a new subculture you have never before experienced? Whatever piques your interest, immerse yourself.

Example: The Botany of Desire by Michael Pollan

If you’re looking for an example of literary journalism that tells a great story, look no further than Michael Pollan’s The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World , which sits at the intersection of food writing and popular science. Though it purports to offer a “plant’s-eye view of the world,” it’s as much about human desires as it is about the natural world.

Through the history of four different plants and human’s efforts to cultivate them, Pollan uses first-hand research as well as archival facts to explore how we attempt to domesticate nature for our own pleasure, and how these efforts can even have devastating consequences. Pollan is himself a character in the story, and makes what could be a remarkably dry topic accessible and engaging in the process.

Tip: Don’t pretend that you’re perfectly objective

You may have more room for your own perspective within literary journalism, but with this power comes great responsibility. Your responsibilities toward the reader remain the same as that of a journalist: you must, whenever possible, acknowledge your own biases or conflicts of interest, as well as any limitations on your research.

Thankfully, the fact that literary journalism often involves a certain amount of immersion in the narrative — that is, the writer acknowledges their involvement in the process — you can touch on any potential biases explicitly, and make it clear that the story you’re telling, while true to what you experienced, is grounded in your own personal perspective.

Approach a famous name with a unique approach

Biographies are the chronicle of a human life, from birth to the present or, sometimes, their demise. Often, fact is stranger than fiction, and there is no shortage of fascinating figures from history to discover. As such, a biographical approach to creative nonfiction will leave you spoilt for choice in terms of subject matter.

Because they’re not written by the subjects themselves (as memoirs are), biographical nonfiction requires careful research. If you plan to write one, do everything in your power to verify historical facts, and interview the subject’s family, friends, and acquaintances when possible. Despite the necessity for candor, you’re still welcome to approach biography in a literary way — a great creative biography is both truthful and beautifully written.

Example: American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

Alongside the need for you to present the truth is a duty to interpret that evidence with imagination, and present it in the form of a story. Demonstrating a novelist’s skill for plot and characterization, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s American Prometheus is a great example of creative nonfiction that develops a character right in front of the readers’ eyes.

American Prometheus follows J. Robert Oppenheimer from his bashful childhood to his role as the father of the atomic bomb, all the way to his later attempts to reckon with his violent legacy.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

The biography tells a story that would fit comfortably in the pages of a tragic novel, but is grounded in historical research. Clocking in at a hefty 721 pages, American Prometheus distills an enormous volume of archival material, including letters, FBI files, and interviews into a remarkably readable volume.

📚 For more examples of world-widening, eye-opening biographies, check out our list of the 30 best biographies of all time .

Tip: The good stuff lies in the mundane details

Biographers are expected to undertake academic-grade research before they put pen to paper. You will, of course, read any existing biographies on the person you’re writing about, and visit any archives containing relevant material. If you’re lucky, there’ll be people you can interview who knew your subject personally — but even if there aren’t, what’s going to make your biography stand out is paying attention to details, even if they seem mundane at first.

Of course, no one cares which brand of slippers a former US President wore — gossip is not what we’re talking about. But if you discover that they took a long, silent walk every single morning, that’s a granular detail you could include to give your readers a sense of the weight they carried every day. These smaller details add up to a realistic portrait of a living, breathing human being.

But creative nonfiction isn’t just writing about yourself or other people. Writing about art is also an art, as we’ll see below.

Put your favorite writers through the wringer with literary criticism

Literary criticism is often associated with dull, jargon-laden college dissertations — but it can be a wonderfully rewarding form that blurs the lines between academia and literature itself. When tackled by a deft writer, a literary critique can be just as engrossing as the books it analyzes.

Many of the sharpest literary critics are also poets, poetry editors , novelists, or short story writers, with first-hand awareness of literary techniques and the ability to express their insights with elegance and flair. Though literary criticism sounds highly theoretical, it can be profoundly intimate: you’re invited to share in someone’s experience as a reader or writer — just about the most private experience there is.

Example: The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

Take The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, a seminal work approaching Victorian literature from a feminist perspective. Written as a conversation between two friends and academics, this brilliant book reads like an intellectual brainstorming session in a casual dining venue. Highly original, accessible, and not suffering from the morose gravitas academia is often associated with, this text is a fantastic example of creative nonfiction.

Tip: Remember to make your critiques creative

Literary criticism may be a serious undertaking, but unless you’re trying to pitch an academic journal, you’ll need to be mindful of academic jargon and convoluted sentence structure. Don’t forget that the point of popular literary criticism is to make ideas accessible to readers who aren’t necessarily academics, introducing them to new ways of looking at anything they read.

If you’re not feeling confident, a professional nonfiction editor could help you confirm you’ve hit the right stylistic balance.

Give your book the help it deserves

The best editors, designers, and book marketers are on Reedsy. Sign up for free and meet them.

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

Is creative nonfiction looking a little bit clearer now? You can try your hand at the genre , or head to the next post in this guide and discover online classes where you can hone your skills at creative writing.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your publishing dreams to life

The world's best editors, designers, and marketers are on Reedsy. Come meet them.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Writers' Center

Eastern Washington University

Creative Writing

Creative nonfiction.

- Helpful Links

Within the world of creative writing, the term creative nonfiction encompasses texts about factual events that are not solely for scholarly purposes. Creative nonfiction may include memoir, personal essays, feature-length articles in magazines, and narratives in literary journals. This genre of writing incorporates techniques from fiction and poetry in order to create accounts that read more like story than a piece of journalism or a report. The audience for creative nonfiction is typically broader than the audiences for scholarly writing.

The term creative nonfiction is credited to Lee Gutkind, who defines this genre as “true stories well told.” However, the concept of literary nonfiction has its roots in ancient poetry, historical accounts, and religious texts. Throughout history, people have tried to keep a record of the human experience and have done so through the vehicle of story since the invention of language. For more about the origins of the term creative nonfiction, see the article What is Creative Nonfiction ?

- << Previous: Poetry

- Last Updated: Mar 24, 2022 9:21 PM

- URL: https://research.ewu.edu/writers_c_fiction

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2: Creative Nonfiction

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 33644

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to:

- define Creative Nonfiction and understand the basic features of the genre

- identify basic literary elements (such as setting, plot, character, descriptive imagery, and figurative language)

- perform basic literary analysis

- craft a personal narrative essay using the elements of Creative Nonfiction, using MLA-style formatting

- 2.1: What is Creative Nonfiction?

- 2.2: Elements of Creative Nonfiction

- 2.2: Featured Creative Nonfiction Author- Frederick Douglass

- 2.3: How to Read Creative Nonfiction

- 2.4: Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi "The Danger of a Single Story" (2009)

- 2.4: Elements of Creative Nonfiction

- 2.5.1: Descriptive Imagery Worksheets

- 2.5.2: Creative Nonfiction Reading Discussion Questions

- 2.5.3: The Personal Narrative Essay

- 2.5: Featured Creative Nonfiction Author- Frederick Douglass

- 2.6: Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845)

- 2.7: Cantú, Francisco "Bajadas" (2015)

- 2.8: Anderson, Karen "Six Short Essays" (2017)

- 2.9: Bierce, Ambrose "What I Saw of Shiloh" (1881)

- 2.10: DuBois, W.E.B. "Of Our Spiritual Strivings" from The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

- 2.11: Oomen, Anne-Marie "The Blue" (2018)

- 2.12: Plato "The Allegory of the Cave" excerpt from The Republic (360 BC)

- 2.13: Sun Tzu. The Art of War (5th Century B.C.)

- 2.14: Swift, Jonathan. "A Modest Proposal." (1729)

- 2.15: Wordsworth, Dorothy "Daffodils" entry from Grasmere journal (1802) Excerpt from Dorothy Wordsworth's journals for April 15, 1802, showing her description of daffodils related to her brother William Wordsworth poem "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud."

- 2.16: Descriptive Imagery Worksheets

- 2.17: Creative Nonfiction Assignments, Questions, and Resources

- 2.18: The Personal Narrative Essay

- 2.19: Creative Nonfiction Reading Discussion Questions

- All Online Classes

- 2024 Destination Retreats

- Create account

- — View All Workshops

- — Fiction Classes

- — Nonfiction Classes

- — Poetry Classes

- — Lit Agent Seminar Series

- — 1-On-1 Mentorships

- — Screenwriting & TV Classes

- — Writing for Children

- — Tuscany September 2024: Apply Now!

- — Paris June 2024: Apply Now!

- — Mackinac Island September 2024: Apply Now!

- — ----------------

- — Dublin April 2025: Join List!

- — Iceland June 2025: Join List!

- — Hawaii January 2025: Join List!

- — Vermont August 2024: Join List!

- — Latest Posts

- — Meet the Teaching Artists

- — Student Publication News

- — Our Mission

- — Testimonials

- — FAQ

- — Contact

Shopping Cart

by Writing Workshops Staff

- #Craft of Writing

- #Creative Writing Classes

- #Form a Writing Habit

- #Nonfiction Writing

- #Spiritual Nonfiction

- #Writing Advice

- #Writing Creative Nonfiction

- #Writing Tips

7 Essential Tips on How to Write Creative Nonfiction (A Step-by-Step Guide!)

“The essay becomes an exercise in the meaning and value of watching a writer conquer their own sense of threat to deliver themself of their wisdom.” ― Vivian Gornick, The Situation and the Story: The Art of Personal Narrative

We offer a lot of classes that will help you write Creative Nonfiction . But what makes creative nonfiction different from other types of essays? In creative nonfiction, personal details and anecdotes are used to make the story more relatable and interesting for the reader. Creators often use this style to share their personal thoughts, experiences, or beliefs in a way that can’t be achieved through fiction alone. With a little practice and the right tools, virtually anyone can write creative nonfiction. These tips will help you get started!

Introduction to Creative Nonfiction

Creative nonfiction is a detailed, thoughtful style of writing that allows the author to share their experiences with the reader. It’s similar to a memoir, but it doesn’t have to be a literal account of events. In creative nonfiction, personal details and anecdotes are used to make the story more relatable and interesting for the reader. There are many ways to break down the different types of nonfiction, but broadly speaking, all nonfiction uses the truth, either remembered or researched, to braid together a compelling narrative.

Excellent examples of Creative Nonfiction Include:

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

- The Glass Castle by Jeanette Walls

- Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi

- Committed by Elizabeth Gilbert

- Night Trilogy by Elie Wiesel

- Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

- The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

- Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting by in America by Barbara Ehrenreich

- Dust Tracks on a Road: an autobiography by Nora Zeale Hurston

Select a Topic That You’re Passionate About

Most importantly, choose a topic that you’re passionate about. The topic doesn’t even have to be something that interests you “professionally”—it just has to be something you’re interested in. Begin your research by asking yourself what you’re curious about and what you’ve always wanted to know more about. This can be about yourself, someone else, or the wider world. It could be a current event happening in the world, an everyday activity that many overlook, or a piece of history that has always fascinated you. If you’re struggling to come up with a topic, consider what’s important to you. Your passions, beliefs, and interests can all be great topics to explore in creative nonfiction.

Come Up With Several Ideas for Your Piece

Once you’ve settled on a topic, put together a list of ideas for your creative nonfiction piece. If you’re writing about a current event, you’ll want to make sure that it’s relevant and timely. This way, your readers will be able to connect with your work. You may want to focus on a specific part of the event that interests you. Try to come at your topic from a different angle, or with a new perspective.

Research Your Subject Thoroughly

Once you’ve decided on your topic and idea, it’s time to start researching. In addition to personal experience and anecdote, researching is one of the fundamental parts of writing nonfiction, even if you're writing creatively. If you want to make your research more interesting and engaging for the reader, include anecdotes and personal details.

Now that you’ve put together an outline and researched your topic, it’s time to start writing! It might seem simple, but the hardest part of writing is just getting started. Once you’ve got your thoughts down on paper, the rest is smooth sailing.

Try writing a messy first draft in first person as if you’re speaking directly to your reader. To tap into your voice, don't shy away from using slang, jargon, or other kinds of expression that might be only be understood by a niche audience; you can always layer in more context in a subsequent draft. But whatever you do, don't edit out your style from the beginning. Be you on the page first and polish later.

It is okay to be messy in this draft. Write as naturally as possible so that you aren't sanding away the kind of observations and perspective that amplify your voice and lived experience.

Tips to Help You Write Creatively

Here are a few tips that can help you write creatively:

Read. This may seem obvious, but when you read, you're exposed to a wide range of styles and techniques that can help you understand and use different writing styles. If you're not reading, you're missing out on opportunities to learn from people who've done what you want to do, and that can be invaluable.

Experiment. Experimenting with different writing styles, topics, and approaches will help you to find your voice and discover the types of creative nonfiction that come most naturally to you.

Learn from your peers. Look to your peers and colleagues to learn from them—both their successes and their mistakes.

Find inspiration. Inspiration can come from anywhere, so make sure that you're open to observing new experiences, even in mundane day-to-day activities. Inspiration is everywhere if you're looking for it.

Don't be afraid to fail. This is most import! We learn from our mistakes and experiences, and that's true of writing, too.

Be yourself. The most authentic and interesting writing comes from the heart.

Have fun! Writing should be enjoyable, and trying to write creatively while feeling pressured and stressed out will only make it more difficult.

Discover a Creative Nonfiction Class that is just right for you!

Related Blog Posts

Breaking into Literary Translation: an Interview with Jenna Tang

Meet the Teaching Artist: Mastering Characterization to Elevate Your Writing with Nadia Uddin

Meet the Teaching Artist: How to Write Commercially Viable Historical Fiction with L.M. Elliott

The Essential Guide to Starting Your First Novel

How to get published.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 6: Creative Writing

6.3 Creative Nonfiction

There is lots of creative writing that, unlike a short story, contains factual elements. I may write about “Carellin Brooks,” who has had the same past experiences as me and lives the same kind of life today. However, “Carellin Brooks” is a construct. I am writing about her, so she is a character, even though she shares my name and life.

In creative nonfiction, the lines between reality and what you make up can get quite blurry. That is because, however much we set out to write the exact truth, it still needs shaping into a narrative if anyone is going to be interested in reading it.

You will already know this if you have ever listened to people speaking and written down exactly what they say. Unlike in stories, plays, or other forms of writing, people’s speech is littered with phrases like “um,” “you know,” and “well, ah.” Sentences trail off halfway instead of finishing: “Well, then, I guess we’ll just, um, yeah. That makes sense.” It actually does make sense, in the context of the conversation, but if we accurately recorded such dialogue, either we, or the characters we wrote about, would sound like idiots.

In creative nonfiction, you’re also usually setting out to make a point. Your blog post about the latest great book you read is not going to spend time describing what you had for breakfast (unless it’s a cookbook). Instead, you’ll select and order your details to build toward the point you’re making. You could describe all the books you’ve read lately that haven’t been great, for example, and all the things you did to avoid reading them because you were bored, exaggerating for comic effect, perhaps, to emphasize that you couldn’t put this particular book down for even a minute.

Review Questions

- Write a blog post or journal entry describing a particular day that is significant to you. Try to choose something of personal significance, rather than a national holiday or general celebration, like graduation. (Hint: For ways to make your writing come alive, review Chapter 3.1 Descriptive Paragraphs , which gives you lists of words relating to the five senses and explains how to show, not tell, readers about your subject.)

Points to Consider

- Trade your writing with a classmate. Use the peer review process described in Chapter 7.2 Peer Review to give each other feedback. Revise your writing based on the feedback you received. Do substantial revisions first. As a last step, proofread.

- Find a blog you like, and see if you can figure out how the writer creates comic effect or stokes your interest. After identifying some of the blogger’s strategies, can you use them when you revise your own blog post or journal entry?

Building Blocks of Academic Writing Copyright © 2020 by Carellin Brooks is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Creative writing prize: WOW Creative Nonfiction Essay Contest 2024

Latest posts.

Follow the links in the schedule below or scroll down for the full program of presenters, which includes their bios and abstracts.

- 3:00-3:15: Welcome and Opening Remarks

- 3:15-4:10: Spotlight Panel (fiction, nonfiction, and poetry)

- 4:15-5:00: Session 1 – Panel A (fiction) and Panel B (nonfiction)

- 5:15-6:00: Session 2 – Panel C (poetry)

From 3:00-6:00 pm. all attendees are encouraged to make time to peruse the adjoining Vanderbilt Undergraduate Arts Showcase .

Additional Event Links

- Coming Soon! Read all featured creative writing pieces on the UCWS 2024 Online Creative Writing Gallery

- Coming Soon! Visit the Arts Showcase’s portfolio page to view the incredible works created by undergraduate students.

Full Schedule: Undergraduate Creative Writing Symposium (Wednesday, April 10)

When: Wednesday, April 10, 3:00-6:00 PM | Where: Alumni Hall, 2nd Floor

3:00-3:15 : Opening Remarks by Major Jackson , Professor of English & Director of Creative Writing Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Chair in the Humanities

3:15-4:10 : spotlight panel (alumni hall, room 206).

- Faculty Panel Chair: Justin Quarry (English)

- Panelists: Liam Betts ’24 (poetry), Elyse Sparks ’24 (nonfiction), Avery Fortier ’24 (fiction)

Back to top

Spotlight Panel - Abstracts and Author Bios

Liam betts ’24: the waves of light.

- Presenter Bio : Liam Betts is a senior double majoring in computer science and english. He is originally from Portugal, but now lives in Pleasanton, California. He is the president of VandyWrites and prose editor for The Vanderbilt Review. His story The Waves of Light was selected as First Runner-Up for The Dell Magazines Award for Undergraduate Excellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing in 2024.

- Abstract: The Waves of Light is a neo-Victorian story that reimagines Charles Darwin’s voyage aboard The Beagle to include his two young children, William and Anne. When circumstances thrust both siblings into an odyssey from the Atlantic to London, Anne is forced to reckon with a strange metamorphosis. While William performs street magic to keep them alive, Anne studies and experiments, dreaming of becoming a natural philosopher in nineteenth century England, a world where every door is closed to her. The story is told in the form of a letter from Anne to her father.

Elyse Sparks ’24: The Golden Child

- Presenter Bio : Elyse Sparks in a member of the class of 2024.

- Abstract: The Golden Child is centered around my mental health struggles, sexuality, and my relationship with my pastor parents. I explore how my mom, despite her religious views that seemingly contradict loving a gay child, has stood by my side in a decade-long fight with major depression. Through coming out and hospitalizations and hard conversations, I have watched my mother grow into my biggest advocate.

Avery Fortier ’24: A Clean Mind

- Presenter Bio: Avery is a member of the class of 2024.

- Abstract: This is a piece of fictional prose meant to prompt consideration of mental health experiences across contexts and roles. I wanted to reflect the importance of protecting those responsible for treating others’ health as well as those who more obviously fall into the role of “patient.”

4:15-5:00 : Session 1

- Faculty Panel Chair: Fatima Kola (Medicine, Health, and Society)

- Panelists: Sawyer Sussner ’24 , Shadhvika Nandhakumar ’24 , Claire Marie Tate ’24 , Sanat Malik ’24

- Faculty Panel Chair: Sandy Solomon (English)

- Panelists: Molly Buffenbarger ’24, Franklin Udensi ’27 , Sarah Wermuth ’27 , and TaMyra Johnson ’27

Panel A - Abstracts and Author Bios

Sawyer sussner ’24: power to the players.

- Presenter Bio : Sawyer is a member of the class of 2024.

- Abstract: On her last shift as an employee at the failing gaming giant Game Stop, seventeen year old Twitch streamer Cass must navigate uncomfortable conversations with leering customers along with the impossible expectations of her boss, the washed up manager known to customers only as “The Bobcat,” determined to save his failing store. In a reflection of the gaming world’s treatment of women, Power to the Players explores misogynistic cycles of behavior and how to leave them behind.

Shadhvika Nandakumar ’24: circles

- Presenter Bio: Shadhvika is a member of the class of 2024.

- Abstract: This realistic fiction short story discusses the experiences of a young girl who finds out that her dad has had a heart attack. Told from the perspective of someone looking back over time, it is filled with various musings about the nature of life and relationships.

Claire Marie Tate ’24: Ocular Mistrust

- Presenter Bio: Claire Marie Tate is a member of the class of 2024 from Baton Rouge, LA. She is studying Neuroscience and Medicine, Health, and Society and will begin medical school this fall. In her free time, she enjoys running, dancing, discovering new music, reading, and, more recently, writing as a creative outlet.

- Abstract: “Ocular Mistrust” is a short piece which was inspired by the notion of the eye as the window to the soul and the unreliable nature of the visual pathway. This piece puts artistic themes of eyes in conversation with the physiology of visual processing.

Sanat Malik ’24: Ishak’s

- Presenter Bio: Sanat Malik is a Senior at Vanderbilt University. He was born in Hong Kong, spent some years in his native India, but primarily grew up in Singapore. Sanat is an Economics and English double major who has a passion for short story writing and journalism. He writes mainly about cultural topics with which he has personal experiences and perspectives. After college, Sanat will be working in an Investment Bank as a Raid Defense Consultant. He hopes to continue to grow in his career as a writer beyond college, and ideally would like to pursue investigative journalism in the future.

- Abstract: Ishak’s is a fictional piece about Ishak, an Indian Immigrant who has recently moved to New York to start an Indian fine-dining restaurant with his friend, Jai. Vying to win customers, Ishak creates an open kitchen in hopes that the smells spill onto the streets and draw in customers. In exploring Ishak and Jai’s pursuit of success in the culinary world, the story explores themes of immigration, assimilation, the pursuit of excellence, and the relationship between meticulous Ishak and laid-back Jai.

Panel B - Abstracts and Author Bios

Molly buttenbarger ’24: night watch.

- Presenter Bio: Molly is a member of the class of 2024.

- Abstract: I wrote this memoir about the night I spent alone in the hospital with my mother, when I was in sixth grade. After my mother completed chemotherapy for breast cancer, she underwent a double mastectomy and reconstruction. However, her reconstructed implant got infected, which meant she ended up hospitalized after emergency surgery.

Franklin Udensi ’27: The Igbo Anglican Church

- Presenter Bio: Franklin Udensi, a budding author from Lagos, Nigeria, finds deep inspiration in the works of his favorite author, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and his piece, “The Igbo Anglican Church,” reflects this influence. Beyond literature, Franklin enjoys diving into the immersive worlds of anime and manga, getting swept in the melodies of Jon Bellion, and delighting in the ever-changing landscape of construction sites, where the promise of unfinished structures sparks his imagination. With each stroke of his pen, he blends his varied influences into narratives that speak to the human experience.

- Abstract: This essay explores the author’s encounter with the Igbo Anglican church, unraveling the intricacies of cultural pride, identity, and the pursuit of connection in a diasporic community. Through reflections on language, tradition, and the clash of two worlds, the piece captures a unique narrative that invites readers to contemplate the dynamics of immigrant experiences and the dialogue between belonging and the complexities of assimilating to a new cultural landscape.“The Igbo Anglican Church” is a piece I wrote based on my own experiences navigating the United States upon my arrival during the summer before Vanderbilt. What began as pent-up emotions that I couldn’t quite explain ended up as a short story narrating my observations and cultural clashes with a segment of the Igbo (an ethnic group in Nigeria) diaspora in the US. Writing this piece showed me that my unique perspective as a literary observer could serve as a platform to explore fresh ideas surrounding cultural crossroads, immigrant perspectives, and the complexities of belonging while strengthening confidence in my storytelling abilities. This process enabled me to think critically about my own sentiments and express these thoughts in both personal and universally relatable ways. The piece engages in dialogue by presenting a narrative that resonates with individuals with similar experiences within immigrant communities. It figuratively converses with the present by exploring contemporary themes like cultural integration and identity. Additionally, it contributes to a broader discourse on the immigrant experience, belonging in a foreign land, and the intricate dance between tradition and assimilation, inviting readers to reflect on their encounters with such cultural crossroads.

Sarah Wermuth ’27: I’m Not (Wilmeth) Smart

- Presenter Bio: Sarah is a member of the class of 2027 majoring in Political Science with minors in Gender Studies and Creative Writing.

- Abstract: In 2023, I took a creative nonfiction English class at Vanderbilt, and an essay prompt was: “Write a personal essay exploring one way your identity has developed in opposition to your family of origin.” As a result, I wrote “I’m Not (Wilmeth) Smart.” It tells the story of how growing up in a family of brilliant individuals while simultaneously struggling in school made it hard for me to see myself as smart despite getting into Vanderbilt, one of the top universities in America.

TaMyra Johnson ’27: Racial Imposter Syndrome: Personal Experience + Interviews

- Presenter Bio: TaMyra Johnson is a part of the class of 2027 from Louisville, Kentucky. She plans on double majoring in Communications and Culture Advocacy Leadership with a minor in film.

- Abstract: This piece talks about my personal experience with racial imposter syndrome. Racial imposter syndrome can be described as being unconnected or feeling inauthentic to parts of their racial identity and culture or as when a person feels internally connected to a racial identity that is not perceived by others which causes doubt in their racial self perception.

5:15-6:00: Session 2

- Faculty Panel Chair: Mark Schoenfield (English)

- Panelists: David Lemper ’27 , Nicole Reynaga ’26 , Ilana Drake ’25 , and Eli Apple ’24

Breakout Panel C - Abstracts and Author Bios

David lemper ’27: shakespeare rap.

- Presenter Bio: David is a member of the class of 2027.

- Abstract: This rap was written for an assignment in which students had to cast a scene of a Shakespeare play into rap lyrics. The concept was inspired by Shakespearean rap lyrics from Margaret Atwood’s “Hagseed,” a modern retelling of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.” Rap as a genre—specifcally an African-American born genre—calls back to the theme of freedom, which is a very prominent theme within both Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” and “Romeo and Juliet,” so using this genre to express these narratives evokes the theme of freedom.

Nicole Reynaga ’26: In one breath, we escaped together

- Presenter Bio: Nicole is a member of the class of 2026.

- Abstract: For this workshop’s penultimate poem, we were tasked with writing a prose poem (a poem not split into verse lines). As prose poems typically lack any rules of poetic form and do not visually appear as poetry, they heavily rely on the use of other poetic elements and metaphorical language. The theme of my piece falls into a more personal/self-aware realm.

Ilana Drake ’25: on rapid decline

- Presenter Bio: Ilana Drake is a junior studying Public Policy Studies and English, and she is a student activist and writer. She serves as a United Nations UNA-USA Global Goals Ambassador for SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and she was selected as a Clinton Global Initiative University Fellow in 2023. This year, Ilana was appointed to the Inaugural Student Advisory Board for the Vanderbilt Project on Unity and American Democracy. Ilana was recognized as one of the forty undergraduate changemakers on Vanderbilt’s campus last year, and she is a Delegate for the 68th Session of the Commission on the Status of Women. Ilana’s writing has been published in Insider , Ms. Magazine, and The Tennessean , among others, and she has been quoted in The New York Times , The Washington Post , and Teen Vogue . Her poetry has been published internationally in literary magazines and zines. In her free time, she enjoys swimming, exploring Nashville with friends, and searching for the best iced coffee.

- Abstract: This poem is about the importance of time and health. I wrote this piece following my grandmother’s death in November 2023.

Eli Apple ’24: Autoimmune (Selected Poems)

- Presenter Bio: Eli Apple is a writer of fiction and poetry. He has lived his whole life in Tennessee and is currently a senior at Vanderbilt University, where he is studying English, Spanish, and Portuguese. In addition to writing, he loves reading, traveling, and going on walks with his dog.

- Abstract: My submission includes eight poems that will appear in my English Honors thesis. My thesis, entitled Autoimmune, is a poetry collection that investigates literal and metaphorical illnesses and their effects on the body. These poems belong in Part Two of the collection, which examines homosexuality and internalized homophobia as illnesses together with the continuing effects of the AIDS epidemic on American society.

Access the UCWS 2024 Online Gallery

Coming Soon! Visit the UCWS 2024 Online Gallery of Creative Writing to read each of this year’s featured works along with a reflection from its author.

Special Thanks and Acknowledgements

The Writing Studio offers special thanks to all those who helped make our event possible and have contributed to its success.

Our Event Co-Host and Partner

The Office of Experiential Learning and Immersion Vanderbilt

Our Event Co-Sponsors

The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons

The Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries

Our Invited Creative Writing Reviewers from the MFA Program in Creative Writing

Langston Cotman

Ajla Dizdarević

Sydney Mayes

Our Writing Studio and Tutoring Services team members

Beth Estes (Assistant Director), Lead Symposium Coordinator

Lucy Kim (Academic Support Coordinator), Assistant Symposium Coordinator

Drew Shipley (Academic Support Coordinator), Assistant Symposium Coordinator

Cameron Sheehy (Peabody), Graduate Assistant Symposium Coordinator

Tim Donahoo, Administrative Specialist for the Writing Studio and Tutoring Services

all Writing Consultants Events Committee Members and all consultants present to support the event today

In order to access certain content on this page, you may need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader or an equivalent PDF viewer software.

The 5 Rs of Creative Nonfiction

What's the Story #06

“The Essayist at Work” is our first special issue. The cover is different, and although it is our habit to center each issue around a general theme, the essays and profiles in “The Essayist at Work” are narrower in scope. In the future, we intend to publish special issues on a variety of topics, but this one is especially important, not only because it is our first, but also because it helps to launch the first Mid-Atlantic Creative Nonfiction Summer Writers’ Conference with the Goucher College Center for Graduate and Continuing Studies in Baltimore, Md., a supportive and enthusiastic summer partner. Many writers featured in “The Essayist at Work” will also be participating at the conference – an event we hope to continue to co-sponsor with Goucher for years to come.

The writers in this issue represent the incredible range of the newly emerging genre of creative nonfiction, from the struggle and success stories of Darcy Frey (“The Last Shot”) and William Least Heat-Moon (“Blue Highways”) to the master of the profession, John McPhee. From the roots of traditional journalism to poetry and fiction, Pulitzer Prize-winner Alice Steinbach, poet Diane Ackerman and novelists Phillip Lopate and Paul West, have helped expand the boundaries of form and tradition. Jane Bernstein, Steven Harvey, Mary Paumier Jones, Wendy Lesser and Natalia Rachel Singer ponder the spirit of the essay (and e-mail!), while I continue to reflect on and define the creative nonfiction form.

From the beginning, it has been our mission to probe the depths and intricacies of nonfiction by publishing the best prose by new and established writers. Creative Nonfiction provides a forum for writers, editors and readers interested in pushing the envelope of creativity and discussing and defining the parameters of accuracy, validity and truth. My essay below, “The 5 Rs of Creative Nonfiction,” is dedicated to that mission. It will appear in “More than the Truth: Teaching Nonfiction Writing Through Journalism,” which will be published in the fall of 1996 by Heineman.

It is 3 a.m., and I am standing on a stool in the operating room at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, in scrubs, mask, cap and paper booties, peering over the hunched shoulders of four surgeons and a scrub nurse as a dying woman’s heart and lungs are being removed from her chest. This is a scene I have observed frequently since starting my work on a book about the world of organ transplantation, but it never fails to amaze and startle me: to look down into a gaping hole in a human being’s chest, which has been cracked open and emptied of all of its contents, watching the monitor and listening to the rhythmic sighing sounds of the ventilator, knowing that this woman is on the fragile cusp of life and death and that I am observing what might well be the final moments of her life.

Now the telephone rings; a nurse answers, listens for a moment and then hangs up. “On the roof,” she announces, meaning that the helicopter has set down on the hospital helipad and that a healthy set of organs, a heart and two lungs, en bloc, will soon be available to implant into this woman, whose immediate fate will be decided within the next few hours.

With a brisk nod, the lead surgeon, Bartley Griffith, a young man who pioneered heart-lung transplantation and who at this point has lost more patients with the procedure than he had saved, looks up, glances around and finally rests his eyes on me: “Lee,” he says, “would you do me a great favor?”

I was surprised. Over the past three years I had observed Bart Griffith in the operating room a number of times, and although a great deal of conversation takes place between doctors and nurses during the long and intense surgical ordeal, he had only infrequently addressed me in such a direct and spontaneous manner.

Our personal distance is a by-product of my own technique as an immersion journalist – my “fly-on-the wall” or “living room sofa” concept of “immersion”: Writers should be regular and silent observers, so much so that they are virtually unnoticed. Like walking through your living room dozens of times, but only paying attention to the sofa when suddenly you realize that it is missing. Researching a book about transplantation, “Many Sleepless Nights” (W.W. Norton), I had been accorded great access to the O.R., the transplant wards, ethics debates and the most intimate conversations between patients, family members and medical staff. I had jetted through the night on organ donor runs. I had witnessed great drama – at a personal distance.

But on that important early morning, Bartley Griffith took note of my presence and requested that I perform a service for him. He explained that this was going to be a crucial time in the heart-lung procedure, which had been going on for about five hours, but that he felt obligated to make contact with this woman’s husband who had traveled here from Kansas City, Mo. “I can’t take the time to talk to the man myself, but I am wondering if you would brief him as to what has happened so far. Tell him that the organs have arrived, but that even if all goes well, the procedure will take at least another five hours and maybe longer.” Griffith didn’t need to mention that the most challenging aspect of the surgery – the implantation – was upcoming; the danger to the woman was at a heightened state.

A few minutes later, on my way to the ICU waiting area where I would find Dave Fulk, the woman’s husband, I stopped in the surgeon’s lounge for a quick cup of coffee and a moment to think about how I might approach this man, undoubtedly nervous – perhaps even hysterical – waiting for news of his wife. I also felt kind of relieved, truthfully, to be out of the O.R,, where the atmosphere is so intense.

Although I had been totally caught-up in the drama of organ transplantation during my research, I had recently been losing my passion and curiosity; I was slipping into a life and death overload in which all of the sad stories from people all across the world seemed to be congealing into the same muddled dream. From experience, I recognized this feeling – a clear signal that it was time to abandon the research phase of this book and sit down and start to write. Yet, as a writer, I was confronting a serious and frightening problem: Overwhelmed with facts and statistics, tragic and triumphant stories, I felt confused. I knew, basically, what I wanted to say about what I learned, but I didn’t know how to structure my message or where to begin.

And so, instead of walking away from this research experience and sitting down and starting to write my book, I continued to return to the scene of my transplant adventures waiting for lightning to strike . . . inspiration for when the very special way to start my book would make itself known. In retrospect, I believe that Bart Griffith’s rare request triggered that magic moment of clarity I had long been awaiting.

Defining the Discussion

Before I tell you what happened, however, let me explain what kind of work I do as an immersion journalist/creative nonfiction writer, and explain what I am doing, from a writer’s point-of-view, in this essay.

But first some definitions: “Immersion journalists” immerse or involve themselves in the lives of the people about whom they are writing in ways that will provide readers with a rare and special intimacy.