33 Critical Analysis Examples

Critical analysis refers to the ability to examine something in detail in preparation to make an evaluation or judgment.

It will involve exploring underlying assumptions, theories, arguments, evidence, logic, biases, contextual factors, and so forth, that could help shed more light on the topic.

In essay writing, a critical analysis essay will involve using a range of analytical skills to explore a topic, such as:

- Evaluating sources

- Exploring strengths and weaknesses

- Exploring pros and cons

- Questioning and challenging ideas

- Comparing and contrasting ideas

If you’re writing an essay, you could also watch my guide on how to write a critical analysis essay below, and don’t forget to grab your worksheets and critical analysis essay plan to save yourself a ton of time:

Grab your Critical Analysis Worksheets and Essay Plan Here

Critical Analysis Examples

1. exploring strengths and weaknesses.

Perhaps the first and most straightforward method of critical analysis is to create a simple strengths-vs-weaknesses comparison.

Most things have both strengths and weaknesses – you could even do this for yourself! What are your strengths? Maybe you’re kind or good at sports or good with children. What are your weaknesses? Maybe you struggle with essay writing or concentration.

If you can analyze your own strengths and weaknesses, then you understand the concept. What might be the strengths and weaknesses of the idea you’re hoping to critically analyze?

Strengths and weaknesses could include:

- Does it seem highly ethical (strength) or could it be more ethical (weakness)?

- Is it clearly explained (strength) or complex and lacking logical structure (weakness)?

- Does it seem balanced (strength) or biased (weakness)?

You may consider using a SWOT analysis for this step. I’ve provided a SWOT analysis guide here .

2. Evaluating Sources

Evaluation of sources refers to looking at whether a source is reliable or unreliable.

This is a fundamental media literacy skill .

Steps involved in evaluating sources include asking questions like:

- Who is the author and are they trustworthy?

- Is this written by an expert?

- Is this sufficiently reviewed by an expert?

- Is this published in a trustworthy publication?

- Are the arguments sound or common sense?

For more on this topic, I’d recommend my detailed guide on digital literacy .

3. Identifying Similarities

Identifying similarities encompasses the act of drawing parallels between elements, concepts, or issues.

In critical analysis, it’s common to compare a given article, idea, or theory to another one. In this way, you can identify areas in which they are alike.

Determining similarities can be a challenge, but it’s an intellectual exercise that fosters a greater understanding of the aspects you’re studying. This step often calls for a careful reading and note-taking to highlight matching information, points of view, arguments or even suggested solutions.

Similarities might be found in:

- The key themes or topics discussed

- The theories or principles used

- The demographic the work is written for or about

- The solutions or recommendations proposed

Remember, the intention of identifying similarities is not to prove one right or wrong. Rather, it sets the foundation for understanding the larger context of your analysis, anchoring your arguments in a broader spectrum of ideas.

Your critical analysis strengthens when you can see the patterns and connections across different works or topics. It fosters a more comprehensive, insightful perspective. And importantly, it is a stepping stone in your analysis journey towards evaluating differences, which is equally imperative and insightful in any analysis.

4. Identifying Differences

Identifying differences involves pinpointing the unique aspects, viewpoints or solutions introduced by the text you’re analyzing. How does it stand out as different from other texts?

To do this, you’ll need to compare this text to another text.

Differences can be revealed in:

- The potential applications of each idea

- The time, context, or place in which the elements were conceived or implemented

- The available evidence each element uses to support its ideas

- The perspectives of authors

- The conclusions reached

Identifying differences helps to reveal the multiplicity of perspectives and approaches on a given topic. Doing so provides a more in-depth, nuanced understanding of the field or issue you’re exploring.

This deeper understanding can greatly enhance your overall critique of the text you’re looking at. As such, learning to identify both similarities and differences is an essential skill for effective critical analysis.

My favorite tool for identifying similarities and differences is a Venn Diagram:

To use a venn diagram, title each circle for two different texts. Then, place similarities in the overlapping area of the circles, while unique characteristics (differences) of each text in the non-overlapping parts.

6. Identifying Oversights

Identifying oversights entails pointing out what the author missed, overlooked, or neglected in their work.

Almost every written work, no matter the expertise or meticulousness of the author, contains oversights. These omissions can be absent-minded mistakes or gaps in the argument, stemming from a lack of knowledge, foresight, or attentiveness.

Such gaps can be found in:

- Missed opportunities to counter or address opposing views

- Failure to consider certain relevant aspects or perspectives

- Incomplete or insufficient data that leaves the argument weak

- Failing to address potential criticism or counter-arguments

By shining a light on these weaknesses, you increase the depth and breadth of your critical analysis. It helps you to estimate the full worth of the text, understand its limitations, and contextualize it within the broader landscape of related work. Ultimately, noticing these oversights helps to make your analysis more balanced and considerate of the full complexity of the topic at hand.

You may notice here that identifying oversights requires you to already have a broad understanding and knowledge of the topic in the first place – so, study up!

7. Fact Checking

Fact-checking refers to the process of meticulously verifying the truth and accuracy of the data, statements, or claims put forward in a text.

Fact-checking serves as the bulwark against misinformation, bias, and unsubstantiated claims. It demands thorough research, resourcefulness, and a keen eye for detail.

Fact-checking goes beyond surface-level assertions:

- Examining the validity of the data given

- Cross-referencing information with other reliable sources

- Scrutinizing references, citations, and sources utilized in the article

- Distinguishing between opinion and objectively verifiable truths

- Checking for outdated, biased, or unbalanced information

If you identify factual errors, it’s vital to highlight them when critically analyzing the text. But remember, you could also (after careful scrutiny) also highlight that the text appears to be factually correct – that, too, is critical analysis.

8. Exploring Counterexamples

Exploring counterexamples involves searching and presenting instances or cases which contradict the arguments or conclusions presented in a text.

Counterexamples are an effective way to challenge the generalizations, assumptions or conclusions made in an article or theory. They can reveal weaknesses or oversights in the logic or validity of the author’s perspective.

Considerations in counterexample analysis are:

- Identifying generalizations made in the text

- Seeking examples in academic literature or real-world instances that contradict these generalizations

- Assessing the impact of these counterexamples on the validity of the text’s argument or conclusion

Exploring counterexamples enriches your critical analysis by injecting an extra layer of scrutiny, and even doubt, in the text.

By presenting counterexamples, you not only test the resilience and validity of the text but also open up new avenues of discussion and investigation that can further your understanding of the topic.

See Also: Counterargument Examples

9. Assessing Methodologies

Assessing methodologies entails examining the techniques, tools, or procedures employed by the author to collect, analyze and present their information.

The accuracy and validity of a text’s conclusions often depend on the credibility and appropriateness of the methodologies used.

Aspects to inspect include:

- The appropriateness of the research method for the research question

- The adequacy of the sample size

- The validity and reliability of data collection instruments

- The application of statistical tests and evaluations

- The implementation of controls to prevent bias or mitigate its impact

One strategy you could implement here is to consider a range of other methodologies the author could have used. If the author conducted interviews, consider questioning why they didn’t use broad surveys that could have presented more quantitative findings. If they only interviewed people with one perspective, consider questioning why they didn’t interview a wider variety of people, etc.

See Also: A List of Research Methodologies

10. Exploring Alternative Explanations

Exploring alternative explanations refers to the practice of proposing differing or opposing ideas to those put forward in the text.

An underlying assumption in any analysis is that there may be multiple valid perspectives on a single topic. The text you’re analyzing might provide one perspective, but your job is to bring into the light other reasonable explanations or interpretations.

Cultivating alternative explanations often involves:

- Formulating hypotheses or theories that differ from those presented in the text

- Referring to other established ideas or models that offer a differing viewpoint

- Suggesting a new or unique angle to interpret the data or phenomenon discussed in the text

Searching for alternative explanations challenges the authority of a singular narrative or perspective, fostering an environment ripe for intellectual discourse and critical thinking . It nudges you to examine the topic from multiple angles, enhancing your understanding and appreciation of the complexity inherent in the field.

A Full List of Critical Analysis Skills

- Exploring Strengths and Weaknesses

- Evaluating Sources

- Identifying Similarities

- Identifying Differences

- Identifying Biases

- Hypothesis Testing

- Fact-Checking

- Exploring Counterexamples

- Assessing Methodologies

- Exploring Alternative Explanations

- Pointing Out Contradictions

- Challenging the Significance

- Cause-And-Effect Analysis

- Assessing Generalizability

- Highlighting Inconsistencies

- Reductio ad Absurdum

- Comparing to Expert Testimony

- Comparing to Precedent

- Reframing the Argument

- Pointing Out Fallacies

- Questioning the Ethics

- Clarifying Definitions

- Challenging Assumptions

- Exposing Oversimplifications

- Highlighting Missing Information

- Demonstrating Irrelevance

- Assessing Effectiveness

- Assessing Trustworthiness

- Recognizing Patterns

- Differentiating Facts from Opinions

- Analyzing Perspectives

- Prioritization

- Making Predictions

- Conducting a SWOT Analysis

- PESTLE Analysis

- Asking the Five Whys

- Correlating Data Points

- Finding Anomalies Or Outliers

- Comparing to Expert Literature

- Drawing Inferences

- Assessing Validity & Reliability

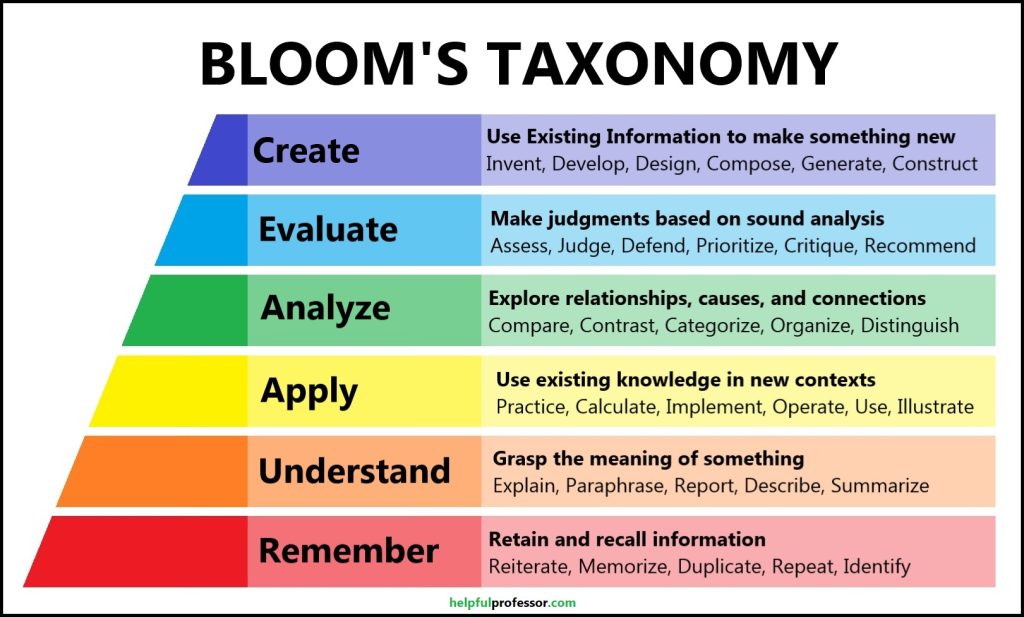

Analysis and Bloom’s Taxonomy

Benjamin Bloom placed analysis as the third-highest form of thinking on his ladder of cognitive skills called Bloom’s Taxonomy .

This taxonomy starts with the lowest levels of thinking – remembering and understanding. The further we go up the ladder, the more we reach higher-order thinking skills that demonstrate depth of understanding and knowledge, as outlined below:

Here’s a full outline of the taxonomy in a table format:

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

2 thoughts on “33 Critical Analysis Examples”

THANK YOU, THANK YOU, THANK YOU! – I cannot even being to explain how hard it has been to find a simple but in-depth understanding of what ‘Critical Analysis’ is. I have looked at over 10 different pages and went down so many rabbit holes but this is brilliant! I only skimmed through the article but it was already promising, I then went back and read it more in-depth, it just all clicked into place. So thank you again!

You’re welcome – so glad it was helpful.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

In Between the Lines: A Guide to Reading Critically

I often find that Princeton professors assume that we all know how to “read critically.” It’s a phrase often included in essay prompts, and a skill necessary to academic writing. Maybe we’re familiar with its definition: close examination of a text’s logic, arguments, style, and other content in order to better understand the author’s intent. Reading non-critically would be identifying a metaphor in a passage, whereas the critical reader would question why the author used that specific metaphor in the first place. Now that the terminology is clarified, what does critical reading look like in practice? I’ve put together a short guide on how I approach my readings to help demystify the process.

- Put on your scholar hat. Critical reading starts before the first page. You should assume that the reading in front of you was the product of several choices made by the author, and that each of these choices is subject to analysis. This is a critical mindset, but importantly, not a negative one. Not taking a reading at face value doesn’t mean approaching the reading hoping to find everything that’s wrong, but rather what could be improved .

- Revisit Writing Sem : Motive and thesis are incredibly helpful guides to understanding tough academic texts. Examining why the author is writing this text (motive), provides a context for the work that follows. The thesis should be in the back of your mind at all times to understand how the evidence presented proves it, but simultaneously thinking about the motive allows you to think about what opponents to the author might say, and then question how the evidence would stand up to these potential rebuttals.

- Get physical . Take notes! Critical reading involves making observations and insights—track them! My process involves underlining, especially as I see recurring terms, images, or themes. As I read, I also like to turn back and forth constantly between pages to link up arguments. I was reading a longer legal text for a class and found that flipping back and forth helped me clarify the ideas presented in the beginning of the text so I could track their development in later pages.

- Play Professor. While I’m reading, I like to imagine potential discussion or essay topics I would come up with if I were a professor. These usually involves examining the themes of the text, placing this text in comparison or contrast with another one we have read in the class, and paying close attention to how the evidence attempts to prove the thesis.

- Form an (informed) opinion. After much work, underlining, and debating, it’s safe to make your own judgments about the author’s work. In forming this opinion, I like to mentally prepare to have this opinion debated, which helps me complicate my own conclusions—a great start to a potential essay!

Critical reading is an important prerequisite for the academic writing that Princeton professors expect. The best papers don’t start with the first word you type, but rather how you approach the texts composing your essay subject. Hopefully, this guide to reading critically will help you write critically as well!

–Elise Freeman, Social Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Home — Essay Samples — Education — Reading — Critical Reading Analysis

Critical Reading Analysis

- Categories: High School Reading

About this sample

Words: 468 |

Published: Mar 20, 2024

Words: 468 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Importance of critical reading analysis, benefits of critical reading analysis, effective application of critical reading analysis.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 351 words

1 pages / 649 words

1 pages / 392 words

3 pages / 1304 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Reading

Percy Jackson, the protagonist of the popular series by Rick Riordan, is a complex character with various traits that make him a compelling and relatable hero. Throughout the series, Percy demonstrates a range of attributes that [...]

Teaching is often considered one of the noblest professions, and for good reason. The impact a teacher can have on a student's life is immeasurable, shaping their future and influencing their personal and professional [...]

In his essay "The Joy Of Reading And Writing: Superman And Me," Sherman Alexie reflects on his personal journey with reading and writing, and how it has shaped his life as a Native American writer. Through this essay, Alexie [...]

Liu, Ziming. 'Digital Reading.' Communications in Information Literacy, vol. 6, no. 2, 2012, pp. 204-217. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2012.6.2.4

Reading is not just an activity; it is a cornerstone of human development that fuels literacy and paves the way for multilingualism. The power of reading lies in its ability to shape language skills, ignite cognitive growth, [...]

"Our knowledge in all these enquiries reaches very little farther than our experience" . Locke asserts the principle that true knowledge is learned. As humans, our knowledge about the world around us and the subjects within it [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

What Is a Critical Analysis Essay: Definition

Have you ever had to read a book or watch a movie for school and then write an essay about it? Well, a critical analysis essay is a type of essay where you do just that! So, when wondering what is a critical analysis essay, know that it's a fancy way of saying that you're going to take a closer look at something and analyze it.

So, let's say you're assigned to read a novel for your literature class. A critical analysis essay would require you to examine the characters, plot, themes, and writing style of the book. You would need to evaluate its strengths and weaknesses and provide your own thoughts and opinions on the text.

Similarly, if you're tasked with writing a critical analysis essay on a scientific article, you would need to analyze the methodology, results, and conclusions presented in the article and evaluate its significance and potential impact on the field.

The key to a successful critical analysis essay is to approach the subject matter with an open mind and a willingness to engage with it on a deeper level. By doing so, you can gain a greater appreciation and understanding of the subject matter and develop your own informed opinions and perspectives. Considering this, we bet you want to learn how to write critical analysis essay easily and efficiently, so keep on reading to find out more!

Meanwhile, if you'd rather have your own sample critical analysis essay crafted by professionals from our custom writings , contact us to buy essays online .

Need a CRITICAL ANALYSIS Essay Written?

Simply pick a topic, send us your requirements and choose a writer. That’s all we need to write you an original paper.

Critical Analysis Essay Topics by Category

If you're looking for an interesting and thought-provoking topic for your critical analysis essay, you've come to the right place! Critical analysis essays can cover many subjects and topics, with endless possibilities. To help you get started, we've compiled a list of critical analysis essay topics by category. We've got you covered whether you're interested in literature, science, social issues, or something else. So, grab a notebook and pen, and get ready to dive deep into your chosen topic. In the following sections, we will provide you with various good critical analysis paper topics to choose from, each with its unique angle and approach.

Critical Analysis Essay Topics on Mass Media

From television and radio to social media and advertising, mass media is everywhere, shaping our perceptions of the world around us. As a result, it's no surprise that critical analysis essays on mass media are a popular choice for students and scholars alike. To help you get started, here are ten critical essay example topics on mass media:

- The Influence of Viral Memes on Pop Culture: An In-Depth Analysis.

- The Portrayal of Mental Health in Television: Examining Stigmatization and Advocacy.

- The Power of Satirical News Shows: Analyzing the Impact of Political Commentary.

- Mass Media and Consumer Behavior: Investigating Advertising and Persuasion Techniques.

- The Ethics of Deepfake Technology: Implications for Trust and Authenticity in Media.

- Media Framing and Public Perception: A Critical Analysis of News Coverage.

- The Role of Social Media in Shaping Political Discourse and Activism.

- Fake News in the Digital Age: Identifying Disinformation and Its Effects.

- The Representation of Gender and Diversity in Hollywood Films: A Critical Examination.

- Media Ownership and Its Impact on Journalism and News Reporting: A Comprehensive Study.

Critical Analysis Essay Topics on Sports

Sports are a ubiquitous aspect of our culture, and they have the power to unite and inspire people from all walks of life. Whether you're an athlete, a fan, or just someone who appreciates the beauty of competition, there's no denying the significance of sports in our society. If you're looking for an engaging and thought-provoking topic for your critical analysis essay, sports offer a wealth of possibilities:

- The Role of Sports in Diplomacy: Examining International Relations Through Athletic Events.

- Sports and Identity: How Athletic Success Shapes National and Cultural Pride.

- The Business of Sports: Analyzing the Economics and Commercialization of Athletics.

- Athlete Activism: Exploring the Impact of Athletes' Social and Political Engagement.

- Sports Fandom and Online Communities: The Impact of Social Media on Fan Engagement.

- The Representation of Athletes in the Media: Gender, Race, and Stereotypes.

- The Psychology of Sports: Exploring Mental Toughness, Motivation, and Peak Performance.

- The Evolution of Sports Equipment and Technology: From Innovation to Regulation.

- The Legacy of Sports Legends: Analyzing Their Impact Beyond Athletic Achievement.

- Sports and Social Change: How Athletic Movements Shape Societal Attitudes and Policies.

Critical Analysis Essay Topics on Literature and Arts

Literature and arts can inspire, challenge, and transform our perceptions of the world around us. From classic novels to contemporary art, the realm of literature and arts offers many possibilities for critical analysis essays. Here are ten original critic essay example topics on literature and arts:

- The Use of Symbolism in Contemporary Poetry: Analyzing Hidden Meanings and Significance.

- The Intersection of Art and Identity: How Self-Expression Shapes Artists' Works.

- The Role of Nonlinear Narrative in Postmodern Novels: Techniques and Interpretation.

- The Influence of Jazz on African American Literature: A Comparative Study.

- The Complexity of Visual Storytelling: Graphic Novels and Their Narrative Power.

- The Art of Literary Translation: Challenges, Impact, and Interpretation.

- The Evolution of Music Videos: From Promotional Tools to a Unique Art Form.

- The Literary Techniques of Magical Realism: Exploring Reality and Fantasy.

- The Impact of Visual Arts in Advertising: Analyzing the Connection Between Art and Commerce.

- Art in Times of Crisis: How Artists Respond to Societal and Political Challenges.

Critical Analysis Essay Topics on Culture

Culture is a dynamic and multifaceted aspect of our society, encompassing everything from language and religion to art and music. As a result, there are countless possibilities for critical analysis essays on culture. Whether you're interested in exploring the complexities of globalization or delving into the nuances of cultural identity, there's a wealth of topics to choose from:

- The Influence of K-Pop on Global Youth Culture: A Comparative Study.

- Cultural Significance of Street Art in Urban Spaces: Beyond Vandalism.

- The Role of Mythology in Shaping Indigenous Cultures and Belief Systems.

- Nollywood: Analyzing the Cultural Impact of Nigerian Cinema on the African Diaspora.

- The Language of Hip-Hop Lyrics: A Semiotic Analysis of Cultural Expression.

- Digital Nomads and Cultural Adaptation: Examining the Subculture of Remote Work.

- The Cultural Significance of Tattooing Among Indigenous Tribes in Oceania.

- The Art of Culinary Fusion: Analyzing Cross-Cultural Food Trends and Innovation.

- The Impact of Cultural Festivals on Local Identity and Economy.

- The Influence of Internet Memes on Language and Cultural Evolution.

How to Write a Critical Analysis: Easy Steps

When wondering how to write a critical analysis essay, remember that it can be a challenging but rewarding process. Crafting a critical analysis example requires a careful and thoughtful examination of a text or artwork to assess its strengths and weaknesses and broader implications. The key to success is to approach the task in a systematic and organized manner, breaking it down into two distinct steps: critical reading and critical writing. Here are some tips for each step of the process to help you write a critical essay.

Step 1: Critical Reading

Here are some tips for critical reading that can help you with your critical analysis paper:

- Read actively : Don't just read the text passively, but actively engage with it by highlighting or underlining important points, taking notes, and asking questions.

- Identify the author's main argument: Figure out what the author is trying to say and what evidence they use to support their argument.

- Evaluate the evidence: Determine whether the evidence is reliable, relevant, and sufficient to support the author's argument.

- Analyze the author's tone and style: Consider the author's tone and style and how it affects the reader's interpretation of the text.

- Identify assumptions: Identify any underlying assumptions the author makes and consider whether they are valid or questionable.

- Consider alternative perspectives: Consider alternative perspectives or interpretations of the text and consider how they might affect the author's argument.

- Assess the author's credibility : Evaluate the author's credibility by considering their expertise, biases, and motivations.

- Consider the context: Consider the historical, social, cultural, and political context in which the text was written and how it affects its meaning.

- Pay attention to language: Pay attention to the author's language, including metaphors, symbolism, and other literary devices.

- Synthesize your analysis: Use your analysis of the text to develop a well-supported argument in your critical analysis essay.

Step 2: Critical Analysis Writing

Here are some tips for critical analysis writing, with examples:

- Start with a strong thesis statement: A strong critical analysis thesis is the foundation of any critical analysis essay. It should clearly state your argument or interpretation of the text. You can also consult us on how to write a thesis statement . Meanwhile, here is a clear example:

- Weak thesis statement: 'The author of this article is wrong.'

- Strong thesis statement: 'In this article, the author's argument fails to consider the socio-economic factors that contributed to the issue, rendering their analysis incomplete.'

- Use evidence to support your argument: Use evidence from the text to support your thesis statement, and make sure to explain how the evidence supports your argument. For example:

- Weak argument: 'The author of this article is biased.'

- Strong argument: 'The author's use of emotional language and selective evidence suggests a bias towards one particular viewpoint, as they fail to consider counterarguments and present a balanced analysis.'

- Analyze the evidence : Analyze the evidence you use by considering its relevance, reliability, and sufficiency. For example:

- Weak analysis: 'The author mentions statistics in their argument.'

- Strong analysis: 'The author uses statistics to support their argument, but it is important to note that these statistics are outdated and do not take into account recent developments in the field.'

- Use quotes and paraphrases effectively: Use quotes and paraphrases to support your argument and properly cite your sources. For example:

- Weak use of quotes: 'The author said, 'This is important.'

- Strong use of quotes: 'As the author points out, 'This issue is of utmost importance in shaping our understanding of the problem' (p. 25).'

- Use clear and concise language: Use clear and concise language to make your argument easy to understand, and avoid jargon or overly complicated language. For example:

- Weak language: 'The author's rhetorical devices obfuscate the issue.'

- Strong language: 'The author's use of rhetorical devices such as metaphor and hyperbole obscures the key issues at play.'

- Address counterarguments: Address potential counterarguments to your argument and explain why your interpretation is more convincing. For example:

- Weak argument: 'The author is wrong because they did not consider X.'

- Strong argument: 'While the author's analysis is thorough, it overlooks the role of X in shaping the issue. However, by considering this factor, a more nuanced understanding of the problem emerges.'

- Consider the audience: Consider your audience during your writing process. Your language and tone should be appropriate for your audience and should reflect the level of knowledge they have about the topic. For example:

- Weak language: 'As any knowledgeable reader can see, the author's argument is flawed.'

- Strong language: 'Through a critical analysis of the author's argument, it becomes clear that there are gaps in their analysis that require further consideration.'

Master the art of critical analysis with EssayPro . Our team is ready to guide you in dissecting texts, theories, or artworks with depth and sophistication. Let us help you deliver a critical analysis essay that showcases your analytical prowess.

Creating a Detailed Critical Analysis Essay Outline

Creating a detailed outline is essential when writing a critical analysis essay. It helps you organize your thoughts and arguments, ensuring your essay flows logically and coherently. Here is a detailed critical analysis outline from our dissertation writers :

I. Introduction

A. Background information about the text and its author

B. Brief summary of the text

C. Thesis statement that clearly states your argument

II. Analysis of the Text

A. Overview of the text's main themes and ideas

B. Examination of the author's writing style and techniques

C. Analysis of the text's structure and organization

III. Evaluation of the Text

A. Evaluation of the author's argument and evidence

B. Analysis of the author's use of language and rhetorical strategies

C. Assessment of the text's effectiveness and relevance to the topic

IV. Discussion of the Context

A. Exploration of the historical, cultural, and social context of the text

B. Examination of the text's influence on its audience and society

C. Analysis of the text's significance and relevance to the present day

V. Counter Arguments and Responses

A. Identification of potential counterarguments to your argument

B. Refutation of counterarguments and defense of your position

C. Acknowledgement of the limitations and weaknesses of your argument

VI. Conclusion

A. Recap of your argument and main points

B. Evaluation of the text's significance and relevance

C. Final thoughts and recommendations for further research or analysis.

This outline can be adjusted to fit the specific requirements of your essay. Still, it should give you a solid foundation for creating a detailed and well-organized critical analysis essay.

Useful Techniques Used in Literary Criticism

There are several techniques used in literary criticism to analyze and evaluate a work of literature. Here are some of the most common techniques:

- Close reading: This technique involves carefully analyzing a text to identify its literary devices, themes, and meanings.

- Historical and cultural context: This technique involves examining the historical and cultural context of a work of literature to understand the social, political, and cultural influences that shaped it.

- Structural analysis: This technique involves analyzing the structure of a text, including its plot, characters, and narrative techniques, to identify patterns and themes.

- Formalism: This technique focuses on the literary elements of a text, such as its language, imagery, and symbolism, to analyze its meaning and significance.

- Psychological analysis: This technique examines the psychological and emotional aspects of a text, including the motivations and desires of its characters, to understand the deeper meanings and themes.

- Feminist and gender analysis: This technique focuses on the representation of gender and sexuality in a text, including how gender roles and stereotypes are reinforced or challenged.

- Marxist and social analysis: This technique examines the social and economic structures portrayed in a text, including issues of class, power, and inequality.

By using these and other techniques, literary critics can offer insightful and nuanced analyses of works of literature, helping readers to understand and appreciate the complexity and richness of the texts.

Sample Critical Analysis Essay

Now that you know how to write a critical analysis, take a look at the critical analysis essay sample provided by our research paper writers and better understand this kind of paper!

Final Words

At our professional writing services, we understand the challenges and pressures that students face regarding academic writing. That's why we offer high-quality, custom-written essays designed to meet each student's specific needs and requirements.

By using our essay writing service , you can save time and energy while also learning from our expert writers and improving your own writing skills. We take pride in our work and are dedicated to providing friendly and responsive customer support to ensure your satisfaction with every order. So why struggle with difficult assignments when you can trust our professional writing services to deliver the quality and originality you need? Place your order today and experience the benefits of working with our team of skilled and dedicated writers.

If you need help with any of the STEPS ABOVE

Feel free to use EssayPro Outline Help

What Type Of Language Should Be Used In A Critical Analysis Essay?

How to write a critical analysis essay, what is a critical analysis essay, related articles.

.webp)

How to Write a Critical Essay

Hill Street Studios / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Olivia Valdes was the Associate Editorial Director for ThoughtCo. She worked with Dotdash Meredith from 2017 to 2021.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Olivia-Valdes_WEB1-1e405fc799d9474e9212215c4f21b141.jpg)

- B.A., American Studies, Yale University

A critical essay is a form of academic writing that analyzes, interprets, and/or evaluates a text. In a critical essay, an author makes a claim about how particular ideas or themes are conveyed in a text, then supports that claim with evidence from primary and/or secondary sources.

In casual conversation, we often associate the word "critical" with a negative perspective. However, in the context of a critical essay, the word "critical" simply means discerning and analytical. Critical essays analyze and evaluate the meaning and significance of a text, rather than making a judgment about its content or quality.

What Makes an Essay "Critical"?

Imagine you've just watched the movie "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory." If you were chatting with friends in the movie theater lobby, you might say something like, "Charlie was so lucky to find a Golden Ticket. That ticket changed his life." A friend might reply, "Yeah, but Willy Wonka shouldn't have let those raucous kids into his chocolate factory in the first place. They caused a big mess."

These comments make for an enjoyable conversation, but they do not belong in a critical essay. Why? Because they respond to (and pass judgment on) the raw content of the movie, rather than analyzing its themes or how the director conveyed those themes.

On the other hand, a critical essay about "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory" might take the following topic as its thesis: "In 'Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,' director Mel Stuart intertwines money and morality through his depiction of children: the angelic appearance of Charlie Bucket, a good-hearted boy of modest means, is sharply contrasted against the physically grotesque portrayal of the wealthy, and thus immoral, children."

This thesis includes a claim about the themes of the film, what the director seems to be saying about those themes, and what techniques the director employs in order to communicate his message. In addition, this thesis is both supportable and disputable using evidence from the film itself, which means it's a strong central argument for a critical essay .

Characteristics of a Critical Essay

Critical essays are written across many academic disciplines and can have wide-ranging textual subjects: films, novels, poetry, video games, visual art, and more. However, despite their diverse subject matter, all critical essays share the following characteristics.

- Central claim . All critical essays contain a central claim about the text. This argument is typically expressed at the beginning of the essay in a thesis statement , then supported with evidence in each body paragraph. Some critical essays bolster their argument even further by including potential counterarguments, then using evidence to dispute them.

- Evidence . The central claim of a critical essay must be supported by evidence. In many critical essays, most of the evidence comes in the form of textual support: particular details from the text (dialogue, descriptions, word choice, structure, imagery, et cetera) that bolster the argument. Critical essays may also include evidence from secondary sources, often scholarly works that support or strengthen the main argument.

- Conclusion . After making a claim and supporting it with evidence, critical essays offer a succinct conclusion. The conclusion summarizes the trajectory of the essay's argument and emphasizes the essays' most important insights.

Tips for Writing a Critical Essay

Writing a critical essay requires rigorous analysis and a meticulous argument-building process. If you're struggling with a critical essay assignment, these tips will help you get started.

- Practice active reading strategies . These strategies for staying focused and retaining information will help you identify specific details in the text that will serve as evidence for your main argument. Active reading is an essential skill, especially if you're writing a critical essay for a literature class.

- Read example essays . If you're unfamiliar with critical essays as a form, writing one is going to be extremely challenging. Before you dive into the writing process, read a variety of published critical essays, paying careful attention to their structure and writing style. (As always, remember that paraphrasing an author's ideas without proper attribution is a form of plagiarism .)

- Resist the urge to summarize . Critical essays should consist of your own analysis and interpretation of a text, not a summary of the text in general. If you find yourself writing lengthy plot or character descriptions, pause and consider whether these summaries are in the service of your main argument or whether they are simply taking up space.

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- How To Write an Essay

- Critical Analysis in Composition

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- How to Write and Format an MBA Essay

- Higher Level Thinking: Synthesis in Bloom's Taxonomy

- How To Write a Top-Scoring ACT Essay for the Enhanced Writing Test

- What Is a Critique in Composition?

- How to Structure an Essay

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- How to Write a Response Paper

- Writing a History Book Review

Critical Reading: Critical Reading

- Critical Reading

- Tools to Aid Reading Comprehension

- Tools for Film Analysis

Resources for Critical Reading

Source: Knott, Deborah. Critical Reading Towards Critical Writing. New College Writing Centre. University of Toronto. http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/reading-and-researching/critical-reading

For a nicely formatted pdf of this page, visit http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/images/stories/Documents/critical-reading.pdf

CRITICAL READING TOWARD CRITICAL WRITING Critical writing depends on critical reading. Most of the essays you write will involve reflection on written texts -- the thinking and research that have already been done on your subject. In order to write your own analysis of this subject, you will need to do careful critical reading of sources and to use them critically to make your own argument. The judgments and interpretations you make of the texts you read are the first steps towards formulating your own approach. CRITICAL READING: WHAT IS IT? To read critically is to make judgments about how a text is argued. This is a highly reflective skill requiring you to “stand back” and gain some distance from the text you are reading. (You might have to read a text through once to get a basic grasp of content before you launch into an intensive critical reading.) THE KEY IS THIS: -- don’t read looking only or primarily for information -- do read looking for ways of thinking about the subject matter When you are reading, highlighting, or taking notes, avoid extracting and compiling lists of evidence, lists of facts and examples. Avoid approaching a text by asking “What information can I get out of it?” Rather ask “How does this text work? How is it argued? How is the evidence (the facts, examples, etc.) used and interpreted? How does the text reach its conclusions? HOW DO I READ LOOKING FOR WAYS OF THINKING? 1. First determine the central claims or purpose of the text (its thesis). A critical reading attempts to identify and assess how these central claims are developed or argued. 2. Begin to make some judgments about context. What audience is the text written for? Who is it in dialogue with? (This will probably be other scholars or authors with differing viewpoints.) In what historical context is it written? All these matters of context can contribute to your assessment of what is going on in a text. 3. Distinguish the kinds of reasoning the text employs. What concepts are defined and used? Does the text appeal to a theory or theories? Is any specific methodology laid out? If there is an appeal to a particular concept, theory, or method, how is that concept, theory, or method then used to organize and interpret the data? You might also examine how the text is organized: how has the author analyzed (broken down) the material? Be aware that different disciplines (i.e. history, sociology, philosophy, biology) will have different ways of arguing.

4. Examine the evidence (the supporting facts, examples, etc) the text employs. Supporting evidence is indispensable to an argument. Having worked through Steps 1-3, you are now in a position to grasp how the evidence is used to develop the argument and its controlling claims and concepts. Steps 1-3 allow you to see evidence in its context. Consider the kinds of evidence that are used. What counts as evidence in this argument? Is the evidence statistical? literary? historical? etc. From what sources is the evidence taken? Are these sources primary or secondary? 5. Critical reading may involve evaluation. Your reading of a text is already critical if it accounts for and makes a series of judgments about how a text is argued. However, some essays may also require you to assess the strengths and weaknesses of an argument. If the argument is strong, why? Could it be better or differently supported? Are there gaps, leaps, or inconsistencies in the argument? Is the method of analysis problematic? Could the evidence be interpreted differently? Are the conclusions warranted by the evidence presented? What are the unargued assumptions? Are they problematic? What might an opposing argument be? SOME PRACTICAL TIPS: 1. Critical reading occurs after some preliminary processes of reading. Begin by skimming research materials, especially introductions and conclusions, in order to strategically choose where to focus your critical efforts. 2. When highlighting a text or taking notes from it, teach yourself to highlight argument: those places in a text where an author explains her analytical moves, the concepts she uses, how she uses them, how she arrives at conclusions. Don’t let yourself foreground and isolate facts and examples, no matter how interesting they may be. First, look for the large patterns that give purpose, order, and meaning to those examples. The opening sentences of paragraphs can be important to this task. 3. When you begin to think about how you might use a portion of a text in the argument you are forging in your own paper, try to remain aware of how this portion fits into the whole argument from which it is taken. Paying attention to context is a fundamental critical move. 4. When you quote directly from a source, use the quotation critically. This means that you should not substitute the quotation for your own articulation of a point. Rather, introduce the quotation by laying out the judgments you are making about it, and the reasons why you are using it. Often a quotation is followed by some further analysis. 5. Critical reading skills are also critical listening skills. In your lectures, listen not only for information but also for ways of thinking. Your instructor will often explicate and model ways of thinking appropriate to a discipline.

Prepared by Deborah Knott, Director of the New College Writing Centre Over 50 other files giving advice on university writing are available at www.writing.utoronto.ca

Reprinted with permission from D. Knott, 2014

Skimming and Scanning

Source: Freedman, Leora. English Language Learning, Arts and Sciences. University of Toronto. http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/reading-and-researching/skim-and-scan

For a nicely printable pdf version of this, visit: http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/images/stories/Documents/skim-and-scan.pdf

Reading to Write: About Skimming and Scanning Your perceptions of any written text are deepened through familiarity. One of the most effective methods for beginning the kind of thoughtful reading necessary for academic work is to get a general overview of the text before beginning to read it in detail. By first skimming a text, you can get a sense of its overall logical progression. Skimming can also help you make decisions about where to place your greatest focus when you have limited time for your reading. Here is one technique for skimming a text. You may need to modify it to suit your own reading style.

a. First, prior to skimming, use some of the previewing techniques. b. Then, read carefully the introductory paragraph, or perhaps the first two paragraphs. As yourself what the focus of the text appears to be, and try to predict the direction of the coming explanations or arguments. c. Read carefully the first one or two sentences of each paragraph, as well as the concluding sentence or sentences. d. In between these opening and closing sentences, keep your eyes moving and try to avoid looking up unfamiliar words or terminology. Your goal is to pick up the larger concepts and something of the overall pattern and significance of the text. e. Read carefully the concluding paragraph or paragraphs. What does the author’s overall purpose seem to be? Remember that you may be mistaken, so be prepared to modify your answer. f. Finally, return to the beginning and read through the text carefully, noting the complexities you missed in your skimming and filling in the gaps in your understanding. Think about your purpose in reading this text and what you need to retain from it, and adjust your focus accordingly. Look up the terms you need to know, or unfamiliar words that appear several times.

Scanning is basically skimming with a more tightly focused purpose: skimming to locate a particular fact or figure, or to see whether this text mentions a subject you’re researching. Scanning is essential in the writing of research papers, when you may need to look through many articles and books in order to find the material you need. Keep a specific set of goals in mind as you scan the text, and avoid becoming distracted by other material. You can note what you’d like to return to later when you do have time to read further, and use scanning to move ahead in your research project.

Copyright © L. Freedman 2012, University of Toronto

Reprinted with permission of L. Freedman, MFA

Help for Reading Philosophy

The philosophical papers assigned for some of your reading may be more abstract and perhaps do not lend themselves to skimming for understanding or the structured abstract.

Here is an excellent guide for writing a philosophy paper from Harvard College Writing Program. Reading the guide will also help with reading a philosophy paper, since it explains how to organize it :

http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~phildept/files/ShortGuidetoPhilosophicalWriting.pdf

In summary, look for the Big Questions, then the explanation of the thesis, or the argument supporting the thesis, or the objection to the thesis, or the consequences of the thesis, or whether acceptance of another argument supports the thesis, or the acceptanceof other viewpoint(s) if I accept the thesis.

The Harvard guide suggests reading your philosophy papers slowly and carefully, several times.

Look for "signposts ," that reveal the author's intent. Examples, "this, I think, is clearly false," "I will argue that...," "I shall consider...," my strategy will be to...".

It might help to draw out the paper in "thought bubbles", giving you a visual representation, or map.

Guidelines on Reading Philosophy by author Jim Pryor suggests:

- Skim the Article to Find its Conclusion and Get a Sense of its Structure

- Go Back and Read the Article Carefully

- Evaluate the Author's Arguments

- << Previous: Tips and Tools to Aid Reading Comprehension

- Next: Tools to Aid Reading Comprehension >>

- Last Updated: Jan 18, 2023 5:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.library.cofc.edu/critical_reading_LIBR105

College Quick Links

2a. Critical Reading

An introduction to reading in college.

While the best way to develop your skills as a writer is to actually practice by writing, practicing critical reading skills is crucial to becoming a better college writer. Careful and skilled readers develop a stronger understanding of topics, learn to better anticipate the needs of the audience, and pick up sophisticated writing “maneuvers” and strategies from professional writing. A good reading practice requires reading text and context, which you’ll learn more about in the next section. Writing a successful academic essay also begins with critical reading as you explore ideas and consider how to make use of sources to provide support for your writing.

Questions to ask as you read

If you consider yourself a particularly strong reader or want to improve your reading comprehension skills, writing out notes about a text—even if it’s in shorthand—helps you to commit the answers to memory more easily. Even if you don’t write out all these notes, answering these basic questions about any text or reading you encounter in college will help you get the most out of the time you put into your reading. It will also give you more confidence to understand and question the text while you read.

- Is there context provided about the author and/or essay? If so, what stands out as important?

Context in this instance means things like dates of publication, where the piece was originally published, and any biographical information about the author. All of that information will be important for developing a critical reading of the piece, so track what’s available as you read.

- If you had to guess, who is the author’s intended audience ? Describe them in as much detail as possible.

Sometimes the author will state who the audience is, but sometimes you have to figure it out by context clues, such as those you tracked above. For instance, the audience for a writer on Buzzfeed is very different from the audience for a writer for the Wall Street Journal —and both writers know that, which means they’re more effective at reaching their readers. Learning how to identify your audience is a crucial writing skill for all genres of writing.

- In your own words, what is the question the author is trying to answer in this piece? What seems to have caused them to write in the first place?

In nonfiction writing of the kind we read in Writing 121, writers set out to answer a question. Their thesis/main argument is usually the answer to the question, so sometimes you can “reverse engineer” the question from that. Often, the question is asked in the title of the piece.

- In your own words, what’s the author’s main idea or argument ? If you had to distill it down to one or two sentences, what does the author want you, the reader, to agree with?

If you’ve ever had to write a paper for a class, you’re probably familiar with a thesis or main argument. Published writers also have a thesis (or else they don’t get published!), but sometimes it can be tricky to find in a more sophisticated piece of writing. Trying to put the main argument into your own words can help.

- How many examples and types of evidence did the author provide to support the main argument? Which examples/evidence stood out to you as persuasive?

It’s never enough to just make a claim and expect people to believe it—we have to support that claim with evidence. The types of evidence and examples that will be persuasive to readers depends on the audience, though, which is why it’s important to have some idea of your readers and their expectations.

- Did the author raise any points of skepticism (also known as counterarguments)? Can you identify exactly what page or paragraph where the author does this?

As we’ll see later when the writing process, respectfully engaging with points of skepticism and counterarguments builds trust with the reader because it shows that the writer has thought about the issue from multiple perspectives before arriving at the main argument. Raising a counterargument is not enough, though. Pay careful attention to how the writer responds to that counterargument—is it an effective and persuasive response? If not, perhaps the counterargument has more merit for you than the author’s main argument.

- In your own words, how does the essay conclude ? What does the author “want” from us, the readers?

A conclusion usually offers a brief summary of the main argument and some kind of “what’s next?” appeal from the writer to the audience. The “what’s next?” appeal can take many forms, but it’s usually a question for readers to ponder, actions the author thinks people should take, or areas related to the main topic that need more investigation or research. When you read the conclusion, ask yourself, “What does the author want from me now that I’ve read their essay?”

Reading Like Writers: Critical Reading

Reading as a creative act.

“The theory of books is noble. The scholar of the first age received into him the world around; brooded thereon; gave it the new arrangement of his own mind, and uttered it again. It came into him life; it went out from him truth. It came to him short-lived actions; it went out from him immortal thoughts. It came to him business; it went from him poetry. It was dead fact; now, it is quick thought. It can stand, and it can go. It now endures, it now flies, it now inspires. Precisely in proportion to the depth of mind from which it issued, so high does it soar, so long does it sing.” ~Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar”

- Consider the discourse community when you read and write in your college classes

- Analyze any reading for text and context

- Read like a writer so you can write for your readers

By the end of this lesson, you’ll be able to apply the concept of discourse community to honing your college-level critical reading skills.

Good writers are good readers, so let’s start there. When you can confidently identify the audience, context, and purpose of a text —position it within its discourse community—you’ll be a stronger, savvier reader.

Strong, savvy readers are more effective writers because they consider their own audience, context, and purpose when they write and communicate, which makes their writing clearer and to the point.

So the goal of this lesson is to help you read like a writer!

The Savvy Reader

Good writers are good readers! And good readers. . .

- get to know the author

- get to know the author’s community + audience

- accurately summarize the author’s argument

- look up terms you don’t know

- “listen” respectfully to the author’s point of view

- have a sense of the larger conversation

- think about other issues related to the conversation

- put it in current context

- analyze and assess the author’s reasoning, evidence, and assumptions

Why read critically? While the best way to develop your skills as a writer is to actually practice by writing, practicing critical reading skills is crucial to becoming a better writer. Careful and skilled readers develop a stronger understanding of topics, learn to better anticipate the needs of the audience, and pick up writing “maneuvers” and strategies from professional writing.

Reading Like Writers

How do you read like a writer? When you read like a writer, you are practicing deeper reading comprehension. In order to understand a text, you are reading not just what’s in it but what’s around it, too: text and context.

Practice: Reading Like Writers

In-class discussion : Advertisements are helpful for practicing reading like writers because advertisers make deliberate choices with text and images based on audience (target consumer), context (where they are reaching them), and purpose (buy this product).

- But I’m not trying to sell a product! How can I use my newfound understanding of audience, context, and purpose to improve my writing?

It’s true! You aren’t selling a product. You aren’t (I hope) trying to manipulate your audience. You aren’t relying on discriminatory assumptions or stereotypes to appeal to your audience. But when you write, let’s say, an essay, you are asking readers to “buy into” your point of view. The goal doesn’t have to be for them to agree with you; it can be for your readers to respectfully consider, understand, or sympathize with your point of view or analysis of an issue. The point is you’re thinking of your reader when you write, and that will make your writing process smoother and your writing clearer.

Writing for Your Readers

When you write for your readers, you. . .

- Learn from your reading and communication experience: What makes texts work? How are ideas conveyed clearly?

- Analyze the writing situation: What are the goals and purpose for a writing project? Who is your audience?

- Explore and play as you draft: What are different ways to respond? Can you use a better word or phrase?

- Consider your audience: What might a reader expect to see? What does your reader need to understand your point of view? What questions might a reader have?

Writing as a process of inquiry

Just as you want your readers to take you seriously, you want to approach texts with an open and curious mind. Whatever the topic, it was important enough for this person to want to write on it. While we don’t have to agree with the point someone is making, we can respect their opinion and appreciate reading a different perspective.

Approach reading and writing in college in a learning zone. Be open, be curious, ask questions, seek answers. Share, stretch, experiment.

Guides and Worksheets

- Use this guide for any of your college reading!

- Learn a basic study skill–annotating or taking notes on your readings

Critical Reading Guide: Text + Context

Title of the text: Author:

Reading the text: Comprehension

Main idea . In one sentence, summarize the main point or argument of the text.

Claim . Identify one claim in the text.

Key points . Paraphrase a key point, example, or passage that interested you.

Evidence . In your own words, describe 1-2 compelling examples or pieces of evidence that support the point/argument of the text.

Conclusion . What is the ultimate takeaway the text gives us on the topic/issue?

Personal experience . What is your experience of the topic? Have you had problems related to it?

Vocabulary . What is a word or phrase in the text you didn’t know? Look it up. What does it mean?

Inquiry . What is one thing you need more information about? Or, what is one question you have about the content of the text?

Reading for context: Rhetorical analysis

The author . Do an internet search on the author. What did you find out?

Ethos . Do you trust the author on the topic/issue? Why or why not?

Container . When and where was the text first published? Who will read/see it?

Audience . How does the author address or appeal to their readers? What tone does the author use in the text?

Bias . What knowledge, values, or beliefs does the author assume the reader shares?

Types of evidence . What types of evidence does the author use? Types of evidence include facts, examples, statistics, statements by authorities (references to or quotes from other sources), interviews, observations, logical reasoning, and personal experience

Structure . How does the author organize the text?

Purpose . What question does the author seek to answer in the text? In other words, why do you think they wrote this piece?

Mark-up Assignment: The Savvy Reader Practice

The object is to fill the empty space of the margins with your thoughts and questions to the text. By reading sympathetically (reading to understand what the writer is saying) and critically (reading to analyze and critique what the writer is saying), you are reading mindfully and creatively. You are finding those passages that you are drawn to, asking questions that you have, and beginning to develop your reaction, response, and ideas about a topic or issue. It’s a useful tool in the “getting started” phase of the writing process. Learning how to read effectively will be an invaluable skill in your college career and beyond because it means engaging in a task actively rather than passively.

Choose 1-2 paragraphs from READING X to fully annotate. This passage should be one that interests you, i.e. seems important, confusing, and/or prompted agreement, disagreement, or questions for you.

- Circle any word you think is crucial for the passage, including ones you cannot easily define.

- Underline phrases or images you think crucial for the meaning of the passage/essay.

- Put a bracket around ideas or assertions you find puzzling or questionable.

- Then write notes around the margins of the passage defining these terms, identifying the important ideas, or raising questions with the bracketed phrases. For each item you have circled, underlined, or bracketed, there should be a margin note. For this assignment, your margin notes should be substantive: they should meaty statements and full questions.

Photocopy or clear, legible photograph of paragraphs with your annotations or type up the paragraphs and annotate.

Writing as Inquiry Copyright © 2021 by Kara Clevinger and Stephen Rust is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Write a Critical Response Essay With Examples and Tips

16 January 2024

last updated

A critical response essay is an important type of academic essay, which instructors employ to gauge the students’ ability to read critically and express their opinions. Firstly, this guide begins with a detailed definition of a critical essay and an extensive walkthrough of source analysis. Next, the manual on how to write a critical response essay breaks down the writing process into the pre-writing, writing, and post-writing stages and discusses each stage in extensive detail. Finally, the manual provides practical examples of an outline and a critical response essay, which implement the writing strategies and guidelines of critical response writing. After the examples, there is a brief overview of documentation styles. Hence, students need to learn how to write a perfect critical response essay to follow its criteria.

Definition of a Critical Response Essay

A critical response essay presents a reader’s reaction to the content of an article or any other piece of writing and the author’s strategy for achieving his or her intended purpose. Basically, a critical response to a piece of text demands an analysis, interpretation, and synthesis of a reading. Moreover, these operations allow readers to develop a position concerning the extent to which an author of a text creates a desired effect on the audience that an author establishes implicitly or explicitly at the beginning of a text. Mostly, students assume that a critical response revolves around the identification of flaws, but this aspect only represents one dimension of a critical response. In turn, a critical response essay should identify both the strengths and weaknesses of a text and present them without exaggeration of their significance in a text.

Source Analysis

1. Questions That Guide Source Analysis

Writers engage in textual analysis through critical reading. Hence, students undertake critical reading to answer three primary questions:

- What does the author say or show unequivocally?

- What does the author not say or show outright but implies intentionally or unintentionally in the text?

- What do I think about responses to the previous two questions?

Readers should strive to comprehensively answer these questions with the context and scope of a critical response essay. Basically, the need for objectivity is necessary to ensure that the student’s analysis does not contain any biases through unwarranted or incorrect comparisons. Nonetheless, the author’s pre-existing knowledge concerning the topic of a critical response essay is crucial in facilitating the process of critical reading. In turn, the generation of answers to three guiding questions occurs concurrently throughout the close reading of an assigned text or other essay topics .

2. Techniques of Critical Reading

Previewing, reading, and summarizing are the main methods of critical reading. Basically, previewing a text allows readers to develop some familiarity with the content of a critical response essay, which they gain through exposure to content cues, publication facts, important statements, and authors’ backgrounds. In this case, readers may take notes of questions that emerge in their minds and possible biases related to prior knowledge. Then, reading has two distinct stages: first reading and rereading and annotating. Also, students read an assigned text at an appropriate speed for the first time with minimal notetaking. After that, learners reread a text to identify core and supporting ideas, key terms, and connections or implied links between ideas while making detailed notes. Lastly, writers summarize their readings into the main points by using their own words to extract the meaning and deconstruct critical response essays into meaningful parts.

3. Creating a Critical Response

Up to this point, source analysis is a blanket term that represents the entire process of developing a critical response. Mainly, the creation of a critical response essay involves analysis, interpretation, and synthesis, which occur as distinct activities. In this case, students analyze their readings by breaking down texts into elements with distilled meanings and obvious links to a thesis statement . During analysis, writers may develop minor guiding questions under first and second guiding questions, which are discipline-specific. Then, learners focus on interpretations of elements to determine their significance to an assigned text as a whole, possible meanings, and assumptions under which they may exist. Finally, authors of critical response essays create connections through the lens of relevant pre-existing knowledge, which represents a version of the element’s interconnection that they perceive to be an accurate depiction of a text.

Writing Steps of a Critical Response Essay

Step 1: pre-writing, a. analysis of writing situation.

Purpose. Before a student begins writing a critical response essay, he or she must identify the main reason for communication to the audience by using a formal essay format. Basically, the primary purposes of writing a critical response essay are explanation and persuasion. In this case, it is not uncommon for two purposes to overlap while writing a critical response essay. However, one of the purposes is usually dominant, which implies that it plays a dominant role in the wording, evidence selection, and perspective on a topic. In turn, students should establish their purposes in the early stages of the writing process because the purpose has a significant effect on the essay writing approach.

Audience. Students should establish a good understanding of the audience’s expectations, characteristics, attitudes, and knowledge in anticipation of the writing process. Basically, learning the audience’s expectations enables authors to meet the organizational demands, ‘burden of proof,’ and styling requirements. In college writing, it is the norm for all essays to attain academic writing standards. Then, the interaction between characteristics and attitudes forces authors to identify a suitable voice, which is appreciative of the beliefs and values of the audience. Lastly, writers must consider the level of knowledge of the audience while writing a critical response essay because it has a direct impact on the context, clarity, and readability of a paper. Consequently, a critical response essay for classmates is quite different from a paper that an author presents to a multi-disciplinary audience.

Define a topic. Topic selection is a critical aspect of the prewriting stage. Ideally, assignment instructions play a crucial role in topic selection, especially in higher education institutions. For example, when writing a critical response essay, instructors may choose to provide students with a specific article or general instructions to guide learners in the selection of relevant reading sources. Also, students may not have opportunities for independent topic selection in former circumstances. However, by considering the latter assignment conditions, learners may need to identify a narrow topic to use in article selection. Moreover, students should take adequate time to do preliminary research, which gives them a ‘feel’ of the topic, for example, 19th-century literature. Next, writers narrow down the scope of the topic based on their knowledge and interests, for example, short stories by black female writers from the 19 th century.

B. Research and Documentation

Find sources. Once a student has a topic, he or she can start the process of identifying an appropriate article. Basically, choosing a good source for writing a critical response essay occurs is much easier when aided with search tools on the web or university repository. In this case, learners select keywords or other unique qualities of an article and develop a search filter. Moreover, authors review abstracts or forewords of credible sources to determine their suitability based on their content. Besides content, other factors constrain the article selection process: the word count for a critical response essay and a turnaround time. In turn, if an assignment has a fixed length of 500 words and a turnaround time of one week, it is not practical to select a 200-page source despite content suitability.

Content selection. The process of selecting appropriate content from academic sources relies heavily on the purpose of a critical response essay. Basically, students must select evidence that they will include in a paper to support their claims in each paragraph. However, writers tend to let a source speak through the use of extensive quotations or summaries, which dilutes a synthesis aspect of a critical response essay. Instead, learners should take a significant portion of time to identify evidence from reliable sources , which are relevant to the purpose of an essay. Also, a student who is writing a critical analysis essay to disagree with one or more arguments will select different pieces of evidence as compared to a person who is writing to analyze the overall effectiveness of the work.

Annotated bibliography. An annotated bibliography is vital to the development of a critical response essay because it enables authors to document useful information that they encounter during research. During research and documentation stages for a critical response essay, annotated bibliographies contain the main sources for a critical analysis essay and other sources that contribute to the knowledge base of an author, even though these sources will not appear in reference lists. Mostly, a critical response essay has only one source. However, an annotated bibliography contains summaries of other sources, which may inform the author’s critical response through the development of a deep understanding of a topic. In turn, an annotated bibliography is quite useful when an individual is writing a critical response to an article on an unfamiliar topic.

Step 2: Writing a Critical Response Essay

A. organization..