More results...

Proud recipient of the following awards:

Is the Death Penalty Justified or Should It Be Abolished?

- is the death penalty justified or should it be abolished?

*Updated 2022

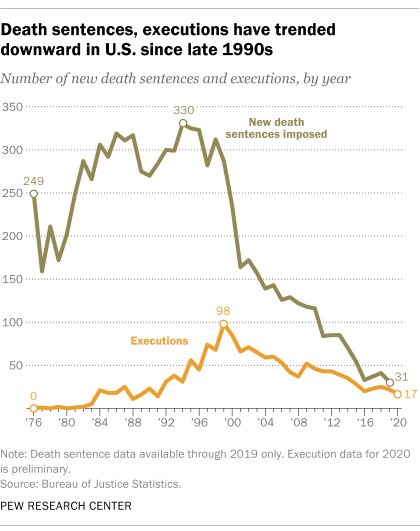

Throughout history, societies around the world have used the death penalty as a way to punish the most heinous crimes. while capital punishment is still practiced today, many countries have since abolished it. in fact, in 2019, california’s governor put a moratorium on the death penalty , stopping it indefinitely. in early 2022, he took further steps and ordered the dismantling of the state’s death row. given the moral complexities and depth of emotions involved, the death penalty remains a controversial debate the world over., the following are three arguments in support of the death penalty and three against it., arguments supporting the death penalty.

Prevents convicted killers from killing again

The death penalty guarantees that convicted murderers will never kill again. There have been countless cases where convicts sentenced to life in prison have murdered other inmates and/or prison guards. Convicts have also been known to successfully arrange murders from within prison, the most famous case being mobster Whitey Bulger , who apparently was killed by fellow inmates while incarcerated. There are also cases where convicts who have been released for parole after serving only part of their sentences – even life sentences – have murdered again after returning to society. A death sentence is the only irrevocable penalty that protects innocent lives.

Maintains justice

For most people, life is sacred, and innocent lives should be valued over the lives of killers. Innocent victims who have been murdered – and in some cases, tortured beforehand – had no choice in their untimely and cruel death or any opportunity to say goodbye to friends and family, prepare wills, or enjoy their last moments of life. Meanwhile, convicted murderers sentenced to life in prison – and even those on death row – are still able to learn, read, write , paint, find religion, watch TV, listen to music, maintain relationships, and even appeal their sentences.

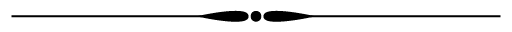

To many, capital punishment symbolizes justice and is the only way to adequately express society’s revulsion of the murder of innocent lives. According to a 2021 Pew Research Center Poll, the majority of US adults ( 60% ) think that legal executions fit the crime of what convicted killers deserve. The death penalty is a way to restore society’s balance of justice – by showing that the most severe crimes are intolerable and will be punished in kind

Historically recognized

Historians and constitutional lawyers seem to agree that by the time the Founding Fathers wrote and signed the U.S. Constitution in 1787, and when the Bill of Rights were ratified and added in 1791, the death penalty was an acceptable and permissible form of punishment for premeditated murder. The Constitution’s 8 th and 14 th Amendments recognize the death penalty BUT under due process of the law. This means that certain legal requirements must first be fulfilled before any state executions can be legally carried out – even when pertaining to the cruelest, most cold-blooded murderer . While interpretations of the amendments pertaining to the death penalty have changed over the years, the Founding Fathers intended to allow for the death penalty from the very beginning and put in place a legal system to ensure due process.

Arguments against the Death Penalty

Not proven to deter crime

There’s no concrete evidence showing that the death penalty actually deters crime. Various studies comparing crime and murder rates in U.S. states that have the death penalty versus those that don’t found that the murder rate in non-death-penalty states has actually remained consistently lower over the years than in those states that have the death penalty. These findings suggest that capital punishment may not actually be a deterrent for crime.

The winds may be shifting regarding the public’s opinion about the death penalty. This is evident by the recent decision of a non-unanimous Florida jury to sentence the Parkland High School shooter to life in prison without parole instead of the death penalty . While the verdict shocked many, it also revealed mixed feelings about the death penalty, including among the families of the 17 Parkland victims and families of victims from other mass shootings.

More expensive than imprisonment

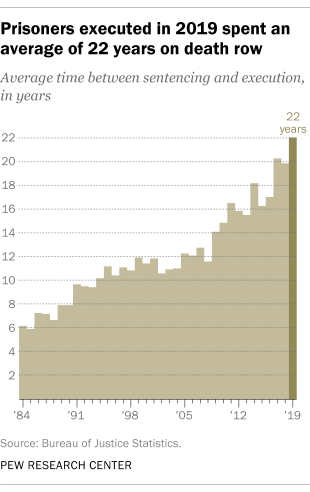

Contrary to popular belief, the death penalty is actually more expensive than keeping an inmate in prison, even for life. While the cost of the actual execution may be minimal, the overall costs surrounding a capital case (where the death penalty is a potential punishment) are enormously high. Sources say that defending a death penalty case can cost around four times higher than defending a case not seeking death. Even in cases where a guilty plea cancels out the need for a trial, seeking the death penalty costs almost twice as much as cases that don’t. And this is before factoring in appeals, which are more time-consuming and therefore cost more than life-sentence appeals, as well as higher prison costs for death-row inmates.

Does not bring closure

It seems logical that punishing a murderer, especially a mass murderer, or terrorist with the most severe punishment would bring closure and relief to victims’ families. However, the opposite may be true. Studies show that capital punishment does not bring comfort to those affected by violent and fatal crimes. In fact, punishing the perpetrator has been shown to make victims feel worse , as it forces them to think about the offender and the incident even more. Also, as capital cases can drag on for years due to endless court appeals, it can be difficult for victims’ families to heal, thus delaying closure.

The Bottom Line: The death penalty has been used to maintain the balance of justice throughout history, punishing violent criminals in the severest way to ensure they won’t kill again. On the other hand, with inconclusive evidence as to its deterrence of crime, the higher costs involved in pursuing capital cases, and the lack of relief and closure it brings to victims’ families, the death penalty is not justified. Where do you stand on this controversial issue?

OWN PERSPECTIVE

Should the US intervene militarily in foreign conflicts?

US intervention overseas is never ideal and usually complicated, but the alternatives may be worse.

Should Puerto Rico become the 51st state?

Welcoming the impoverished island into the U.S. has upsides and downsides.

The Perspective on Putin

As someone both popular and feared, does he deserve respect or suspicion?

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: plain evil or a necessary evil?

In August 1945, two Japanese cities became synonymous with nuclear destruction and the human aptitude for it.

The Perspective on George W. Bush

How will his legacy be remembered. Here are three arguments for and three against W.

Is Monogamy Natural?

Are humans able to live their whole life with a single partner?

The Perspective on Animal Testing

When, if ever, is it justified?

Does Conventional or Alternative Schooling Have More Impact?

The world is made up of so many different types of people, yet most get educated the same way.

Breast vs. Bottle: which is better for babies?

Should parents swear by the breast, or be fully content with bottle feedings?

The Perspective on the United Nations (UN)

The organization is vital international relationships, but it has also experienced many failures over the years.

The Perspective on Having Kids

To parent or not to parent?

the death penalty debate

Arguments for and Against the Death Penalty

Click the buttons below to view arguments and testimony on each topic.

The death penalty deters future murders.

Society has always used punishment to discourage would-be criminals from unlawful action. Since society has the highest interest in preventing murder, it should use the strongest punishment available to deter murder, and that is the death penalty. If murderers are sentenced to death and executed, potential murderers will think twice before killing for fear of losing their own life.

For years, criminologists analyzed murder rates to see if they fluctuated with the likelihood of convicted murderers being executed, but the results were inconclusive. Then in 1973 Isaac Ehrlich employed a new kind of analysis which produced results showing that for every inmate who was executed, 7 lives were spared because others were deterred from committing murder. Similar results have been produced by disciples of Ehrlich in follow-up studies.

Moreover, even if some studies regarding deterrence are inconclusive, that is only because the death penalty is rarely used and takes years before an execution is actually carried out. Punishments which are swift and sure are the best deterrent. The fact that some states or countries which do not use the death penalty have lower murder rates than jurisdictions which do is not evidence of the failure of deterrence. States with high murder rates would have even higher rates if they did not use the death penalty.

Ernest van den Haag, a Professor of Jurisprudence at Fordham University who has studied the question of deterrence closely, wrote: “Even though statistical demonstrations are not conclusive, and perhaps cannot be, capital punishment is likely to deter more than other punishments because people fear death more than anything else. They fear most death deliberately inflicted by law and scheduled by the courts. Whatever people fear most is likely to deter most. Hence, the threat of the death penalty may deter some murderers who otherwise might not have been deterred. And surely the death penalty is the only penalty that could deter prisoners already serving a life sentence and tempted to kill a guard, or offenders about to be arrested and facing a life sentence. Perhaps they will not be deterred. But they would certainly not be deterred by anything else. We owe all the protection we can give to law enforcers exposed to special risks.”

Finally, the death penalty certainly “deters” the murderer who is executed. Strictly speaking, this is a form of incapacitation, similar to the way a robber put in prison is prevented from robbing on the streets. Vicious murderers must be killed to prevent them from murdering again, either in prison, or in society if they should get out. Both as a deterrent and as a form of permanent incapacitation, the death penalty helps to prevent future crime.

Those who believe that deterrence justifies the execution of certain offenders bear the burden of proving that the death penalty is a deterrent. The overwhelming conclusion from years of deterrence studies is that the death penalty is, at best, no more of a deterrent than a sentence of life in prison. The Ehrlich studies have been widely discredited. In fact, some criminologists, such as William Bowers of Northeastern University, maintain that the death penalty has the opposite effect: that is, society is brutalized by the use of the death penalty, and this increases the likelihood of more murder. Even most supporters of the death penalty now place little or no weight on deterrence as a serious justification for its continued use.

States in the United States that do not employ the death penalty generally have lower murder rates than states that do. The same is true when the U.S. is compared to countries similar to it. The U.S., with the death penalty, has a higher murder rate than the countries of Europe or Canada, which do not use the death penalty.

The death penalty is not a deterrent because most people who commit murders either do not expect to be caught or do not carefully weigh the differences between a possible execution and life in prison before they act. Frequently, murders are committed in moments of passion or anger, or by criminals who are substance abusers and acted impulsively. As someone who presided over many of Texas’s executions, former Texas Attorney General Jim Mattox has remarked, “It is my own experience that those executed in Texas were not deterred by the existence of the death penalty law. I think in most cases you’ll find that the murder was committed under severe drug and alcohol abuse.”

There is no conclusive proof that the death penalty acts as a better deterrent than the threat of life imprisonment. A 2012 report released by the prestigious National Research Council of the National Academies and based on a review of more than three decades of research, concluded that studies claiming a deterrent effect on murder rates from the death penalty are fundamentally flawed. A survey of the former and present presidents of the country’s top academic criminological societies found that 84% of these experts rejected the notion that research had demonstrated any deterrent effect from the death penalty .

Once in prison, those serving life sentences often settle into a routine and are less of a threat to commit violence than other prisoners. Moreover, most states now have a sentence of life without parole. Prisoners who are given this sentence will never be released. Thus, the safety of society can be assured without using the death penalty.

Ernest van den Haag Professor of Jurisprudence and Public Policy, Fordham University. Excerpts from ” The Ultimate Punishment: A Defense,” (Harvard Law Review Association, 1986)

“Execution of those who have committed heinous murders may deter only one murder per year. If it does, it seems quite warranted. It is also the only fitting retribution for murder I can think of.”

“Most abolitionists acknowledge that they would continue to favor abolition even if the death penalty were shown to deter more murders than alternatives could deter. Abolitionists appear to value the life of a convicted murderer or, at least, his non-execution, more highly than they value the lives of the innocent victims who might be spared by deterring prospective murderers.

Deterrence is not altogether decisive for me either. I would favor retention of the death penalty as retribution even if it were shown that the threat of execution could not deter prospective murderers not already deterred by the threat of imprisonment. Still, I believe the death penalty, because of its finality, is more feared than imprisonment, and deters some prospective murderers not deterred by the thought of imprisonment. Sparing the lives of even a few prospective victims by deterring their murderers is more important than preserving the lives of convicted murderers because of the possibility, or even the probability, that executing them would not deter others. Whereas the life of the victims who might be saved are valuable, that of the murderer has only negative value, because of his crime. Surely the criminal law is meant to protect the lives of potential victims in preference to those of actual murderers.”

“We threaten punishments in order to deter crime. We impose them not only to make the threats credible but also as retribution (justice) for the crimes that were not deterred. Threats and punishments are necessary to deter and deterrence is a sufficient practical justification for them. Retribution is an independent moral justification. Although penalties can be unwise, repulsive, or inappropriate, and those punished can be pitiable, in a sense the infliction of legal punishment on a guilty person cannot be unjust. By committing the crime, the criminal volunteered to assume the risk of receiving a legal punishment that he could have avoided by not committing the crime. The punishment he suffers is the punishment he voluntarily risked suffering and, therefore, it is no more unjust to him than any other event for which one knowingly volunteers to assume the risk. Thus, the death penalty cannot be unjust to the guilty criminal.”

Full text can be found at PBS.org .

Hugo Adam Bedau (deceased) Austin Fletcher Professor of Philosophy, Tufts University Excerpts from “The Case Against The Death Penalty” (Copyright 1997, American Civil Liberties Union)

“Persons who commit murder and other crimes of personal violence either may or may not premeditate their crimes.

When crime is planned, the criminal ordinarily concentrates on escaping detection, arrest, and conviction. The threat of even the severest punishment will not discourage those who expect to escape detection and arrest. It is impossible to imagine how the threat of any punishment could prevent a crime that is not premeditated….

Most capital crimes are committed in the heat of the moment. Most capital crimes are committed during moments of great emotional stress or under the influence of drugs or alcohol, when logical thinking has been suspended. In such cases, violence is inflicted by persons heedless of the consequences to themselves as well as to others….

If, however, severe punishment can deter crime, then long-term imprisonment is severe enough to deter any rational person from committing a violent crime.

The vast preponderance of the evidence shows that the death penalty is no more effective than imprisonment in deterring murder and that it may even be an incitement to criminal violence. Death-penalty states as a group do not have lower rates of criminal homicide than non-death-penalty states….

On-duty police officers do not suffer a higher rate of criminal assault and homicide in abolitionist states than they do in death-penalty states. Between l973 and l984, for example, lethal assaults against police were not significantly more, or less, frequent in abolitionist states than in death-penalty states. There is ‘no support for the view that the death penalty provides a more effective deterrent to police homicides than alternative sanctions. Not for a single year was evidence found that police are safer in jurisdictions that provide for capital punishment.’ (Bailey and Peterson, Criminology (1987))

Prisoners and prison personnel do not suffer a higher rate of criminal assault and homicide from life-term prisoners in abolition states than they do in death-penalty states. Between 1992 and 1995, 176 inmates were murdered by other prisoners; the vast majority (84%) were killed in death penalty jurisdictions. During the same period about 2% of all assaults on prison staff were committed by inmates in abolition jurisdictions. Evidently, the threat of the death penalty ‘does not even exert an incremental deterrent effect over the threat of a lesser punishment in the abolitionist states.’ (Wolfson, in Bedau, ed., The Death Penalty in America, 3rd ed. (1982))

Actual experience thus establishes beyond a reasonable doubt that the death penalty does not deter murder. No comparable body of evidence contradicts that conclusion.”

Click here for the full text from the ACLU website.

Retribution

A just society requires the taking of a life for a life.

When someone takes a life, the balance of justice is disturbed. Unless that balance is restored, society succumbs to a rule of violence. Only the taking of the murderer’s life restores the balance and allows society to show convincingly that murder is an intolerable crime which will be punished in kind.

Retribution has its basis in religious values, which have historically maintained that it is proper to take an “eye for an eye” and a life for a life.

Although the victim and the victim’s family cannot be restored to the status which preceded the murder, at least an execution brings closure to the murderer’s crime (and closure to the ordeal for the victim’s family) and ensures that the murderer will create no more victims.

For the most cruel and heinous crimes, the ones for which the death penalty is applied, offenders deserve the worst punishment under our system of law, and that is the death penalty. Any lesser punishment would undermine the value society places on protecting lives.

Robert Macy, District Attorney of Oklahoma City, described his concept of the need for retribution in one case: “In 1991, a young mother was rendered helpless and made to watch as her baby was executed. The mother was then mutilated and killed. The killer should not lie in some prison with three meals a day, clean sheets, cable TV, family visits and endless appeals. For justice to prevail, some killers just need to die.”

Retribution is another word for revenge. Although our first instinct may be to inflict immediate pain on someone who wrongs us, the standards of a mature society demand a more measured response.

The emotional impulse for revenge is not a sufficient justification for invoking a system of capital punishment, with all its accompanying problems and risks. Our laws and criminal justice system should lead us to higher principles that demonstrate a complete respect for life, even the life of a murderer. Encouraging our basest motives of revenge, which ends in another killing, extends the chain of violence. Allowing executions sanctions killing as a form of ‘pay-back.’

Many victims’ families denounce the use of the death penalty. Using an execution to try to right the wrong of their loss is an affront to them and only causes more pain. For example, Bud Welch’s daughter, Julie, was killed in the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. Although his first reaction was to wish that those who committed this terrible crime be killed, he ultimately realized that such killing “is simply vengeance; and it was vengeance that killed Julie…. Vengeance is a strong and natural emotion. But it has no place in our justice system.”

The notion of an eye for an eye, or a life for a life, is a simplistic one which our society has never endorsed. We do not allow torturing the torturer, or raping the rapist. Taking the life of a murderer is a similarly disproportionate punishment, especially in light of the fact that the U.S. executes only a small percentage of those convicted of murder, and these defendants are typically not the worst offenders but merely the ones with the fewest resources to defend themselves.

Louis P. Pojman Author and Professor of Philosophy, U.S. Military Academy. Excerpt from “The Death Penalty: For and Against,” (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1998)

“[Opponents of the capital punishment often put forth the following argument:] Perhaps the murderer deserves to die, but what authority does the state have to execute him or her? Both the Old and New Testament says, “’Vengeance is mine, I will repay,’ says the Lord” (Prov. 25:21 and Romans 12:19). You need special authority to justify taking the life of a human being.

The objector fails to note that the New Testament passage continues with a support of the right of the state to execute criminals in the name of God: “Let every person be subjected to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore he who resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment…. If you do wrong, be afraid, for [the authority] does not bear the sword in vain; he is the servant of God to execute his wrath on the wrongdoer” (Romans 13: 1-4). So, according to the Bible, the authority to punish, which presumably includes the death penalty, comes from God.

But we need not appeal to a religious justification for capital punishment. We can site the state’s role in dispensing justice. Just as the state has the authority (and duty) to act justly in allocating scarce resources, in meeting minimal needs of its (deserving) citizens, in defending its citizens from violence and crime, and in not waging unjust wars; so too does it have the authority, flowing from its mission to promote justice and the good of its people, to punish the criminal. If the criminal, as one who has forfeited a right to life, deserves to be executed, especially if it will likely deter would-be murderers, the state has a duty to execute those convicted of first-degree murder.”

National Council of Synagogues and the Bishops’ Committee for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops Excerpts from “To End the Death Penalty: A Report of the National Jewish/Catholic Consultation” (December, 1999)

“Some would argue that the death penalty is needed as a means of retributive justice, to balance out the crime with the punishment. This reflects a natural concern of society, and especially of victims and their families. Yet we believe that we are called to seek a higher road even while punishing the guilty, for example through long and in some cases life-long incarceration, so that the healing of all can ultimately take place.

Some would argue that the death penalty will teach society at large the seriousness of crime. Yet we say that teaching people to respond to violence with violence will, again, only breed more violence.

The strongest argument of all [in favor of the death penalty] is the deep pain and grief of the families of victims, and their quite natural desire to see punishment meted out to those who have plunged them into such agony. Yet it is the clear teaching of our traditions that this pain and suffering cannot be healed simply through the retribution of capital punishment or by vengeance. It is a difficult and long process of healing which comes about through personal growth and God’s grace. We agree that much more must be done by the religious community and by society at large to solace and care for the grieving families of the victims of violent crime.

Recent statements of the Reform and Conservative movements in Judaism, and of the U.S. Catholic Conference sum up well the increasingly strong convictions shared by Jews and Catholics…:

‘Respect for all human life and opposition to the violence in our society are at the root of our long-standing opposition (as bishops) to the death penalty. We see the death penalty as perpetuating a cycle of violence and promoting a sense of vengeance in our culture. As we said in Confronting the Culture of Violence: ‘We cannot teach that killing is wrong by killing.’ We oppose capital punishment not just for what it does to those guilty of horrible crimes, but for what it does to all of us as a society. Increasing reliance on the death penalty diminishes all of us and is a sign of growing disrespect for human life. We cannot overcome crime by simply executing criminals, nor can we restore the lives of the innocent by ending the lives of those convicted of their murders. The death penalty offers the tragic illusion that we can defend life by taking life.’1

We affirm that we came to these conclusions because of our shared understanding of the sanctity of human life. We have committed ourselves to work together, and each within our own communities, toward ending the death penalty.” Endnote 1. Statement of the Administrative Committee of the United States Catholic Conference, March 24, 1999.

The risk of executing the innocent precludes the use of the death penalty.

The death penalty alone imposes an irrevocable sentence. Once an inmate is executed, nothing can be done to make amends if a mistake has been made. There is considerable evidence that many mistakes have been made in sentencing people to death. Since 1973, over 180 people have been released from death row after evidence of their innocence emerged. During the same period of time, over 1,500 people have been executed. Thus, for every 8.3 people executed, we have found one person on death row who never should have been convicted. These statistics represent an intolerable risk of executing the innocent. If an automobile manufacturer operated with similar failure rates, it would be run out of business.

Our capital punishment system is unreliable. A study by Columbia University Law School found that two thirds of all capital trials contained serious errors. When the cases were retried, over 80% of the defendants were not sentenced to death and 7% were completely acquitted.

Many of the releases of innocent defendants from death row came about as a result of factors outside of the justice system. Recently, journalism students in Illinois were assigned to investigate the case of a man who was scheduled to be executed, after the system of appeals had rejected his legal claims. The students discovered that one witness had lied at the original trial, and they were able to find another man, who confessed to the crime on videotape and was later convicted of the murder. The innocent man who was released was very fortunate, but he was spared because of the informal efforts of concerned citizens, not because of the justice system.

In other cases, DNA testing has exonerated death row inmates. Here, too, the justice system had concluded that these defendants were guilty and deserving of the death penalty. DNA testing became available only in the early 1990s, due to advancements in science. If this testing had not been discovered until ten years later, many of these inmates would have been executed. And if DNA testing had been applied to earlier cases where inmates were executed in the 1970s and 80s, the odds are high that it would have proven that some of them were innocent as well.

Society takes many risks in which innocent lives can be lost. We build bridges, knowing that statistically some workers will be killed during construction; we take great precautions to reduce the number of unintended fatalities. But wrongful executions are a preventable risk. By substituting a sentence of life without parole, we meet society’s needs of punishment and protection without running the risk of an erroneous and irrevocable punishment.

There is no proof that any innocent person has actually been executed since increased safeguards and appeals were added to our death penalty system in the 1970s. Even if such executions have occurred, they are very rare. Imprisoning innocent people is also wrong, but we cannot empty the prisons because of that minimal risk. If improvements are needed in the system of representation, or in the use of scientific evidence such as DNA testing, then those reforms should be instituted. However, the need for reform is not a reason to abolish the death penalty.

Besides, many of the claims of innocence by those who have been released from death row are actually based on legal technicalities. Just because someone’s conviction is overturned years later and the prosecutor decides not to retry him, does not mean he is actually innocent.

If it can be shown that someone is innocent, surely a governor would grant clemency and spare the person. Hypothetical claims of innocence are usually just delaying tactics to put off the execution as long as possible. Given our thorough system of appeals through numerous state and federal courts, the execution of an innocent individual today is almost impossible. Even the theoretical execution of an innocent person can be justified because the death penalty saves lives by deterring other killings.

Gerald Kogan, Former Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice Excerpts from a speech given in Orlando, Florida, October 23, 1999 “[T]here is no question in my mind, and I can tell you this having seen the dynamics of our criminal justice system over the many years that I have been associated with it, [as] prosecutor, defense attorney, trial judge and Supreme Court Justice, that convinces me that we certainly have, in the past, executed those people who either didn’t fit the criteria for execution in the State of Florida or who, in fact, were, factually, not guilty of the crime for which they have been executed.

“And you can make these statements when you understand the dynamics of the criminal justice system, when you understand how the State makes deals with more culpable defendants in a capital case, offers them light sentences in exchange for their testimony against another participant or, in some cases, in fact, gives them immunity from prosecution so that they can secure their testimony; the use of jailhouse confessions, like people who say, ‘I was in the cell with so-and-so and they confessed to me,’ or using those particular confessions, the validity of which there has been great doubt. And yet, you see the uneven application of the death penalty where, in many instances, those that are the most culpable escape death and those that are the least culpable are victims of the death penalty. These things begin to weigh very heavily upon you. And under our system, this is the system we have. And that is, we are human beings administering an imperfect system.”

“And how about those people who are still sitting on death row today, who may be factually innocent but cannot prove their particular case very simply because there is no DNA evidence in their case that can be used to exonerate them? Of course, in most cases, you’re not going to have that kind of DNA evidence, so there is no way and there is no hope for them to be saved from what may be one of the biggest mistakes that our society can make.”

The entire speech by Justice Kogan is available here.

Paul G. Cassell Associate Professor of Law, University of Utah, College of Law, and former law clerk to Chief Justice Warren E. Burger. Statement before the Committee on the Judiciary, United States House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights Concerning Claims of Innocence in Capital Cases (July 23, 1993)

“Given the fallibility of human judgments, the possibility exists that the use of capital punishment may result in the execution of an innocent person. The Senate Judiciary Committee has previously found this risk to be ‘minimal,’ a view shared by numerous scholars. As Justice Powell has noted commenting on the numerous state capital cases that have come before the Supreme Court, the ‘unprecedented safeguards’ already inherent in capital sentencing statutes ‘ensure a degree of care in the imposition of the sentence of death that can only be described as unique.’”

“Our present system of capital punishment limits the ultimate penalty to certain specifically-defined crimes and even then, permit the penalty of death only when the jury finds that the aggravating circumstances in the case outweigh all mitigating circumstances. The system further provides judicial review of capital cases. Finally, before capital sentences are carried out, the governor or other executive official will review the sentence to insure that it is a just one, a determination that undoubtedly considers the evidence of the condemned defendant’s guilt. Once all of those decisionmakers have agreed that a death sentence is appropriate, innocent lives would be lost from failure to impose the sentence.”

“Capital sentences, when carried out, save innocent lives by permanently incapacitating murderers. Some persons who commit capital homicide will slay other innocent persons if given the opportunity to do so. The death penalty is the most effective means of preventing such killers from repeating their crimes. The next most serious penalty, life imprisonment without possibility of parole, prevents murderers from committing some crimes but does not prevent them from murdering in prison.”

“The mistaken release of guilty murderers should be of far greater concern than the speculative and heretofore nonexistent risk of the mistaken execution of an innocent person.”

Full text can be found here.

Arbitrariness & Discrimination

The death penalty is applied unfairly and should not be used.

In practice, the death penalty does not single out the worst offenders. Rather, it selects an arbitrary group based on such irrational factors as the quality of the defense counsel, the county in which the crime was committed, or the race of the defendant or victim.

Almost all defendants facing the death penalty cannot afford their own attorney. Hence, they are dependent on the quality of the lawyers assigned by the state, many of whom lack experience in capital cases or are so underpaid that they fail to investigate the case properly. A poorly represented defendant is much more likely to be convicted and given a death sentence.

With respect to race, studies have repeatedly shown that a death sentence is far more likely where a white person is murdered than where a Black person is murdered. The death penalty is racially divisive because it appears to count white lives as more valuable than Black lives. Since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, 296 Black defendants have been executed for the murder of a white victim, while only 31 white defendants have been executed for the murder of a Black victim. Such racial disparities have existed over the history of the death penalty and appear to be largely intractable.

It is arbitrary when someone in one county or state receives the death penalty, but someone who commits a comparable crime in another county or state is given a life sentence. Prosecutors have enormous discretion about when to seek the death penalty and when to settle for a plea bargain. Often those who can only afford a minimal defense are selected for the death penalty. Until race and other arbitrary factors, like economics and geography, can be eliminated as a determinant of who lives and who dies, the death penalty must not be used.

Discretion has always been an essential part of our system of justice. No one expects the prosecutor to pursue every possible offense or punishment, nor do we expect the same sentence to be imposed just because two crimes appear similar. Each crime is unique, both because the circumstances of each victim are different and because each defendant is different. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that a mandatory death penalty which applied to everyone convicted of first degree murder would be unconstitutional. Hence, we must give prosecutors and juries some discretion.

In fact, more white people are executed in this country than black people. And even if blacks are disproportionately represented on death row, proportionately blacks commit more murders than whites. Moreover, the Supreme Court has rejected the use of statistical studies which claim racial bias as the sole reason for overturning a death sentence.

Even if the death penalty punishes some while sparing others, it does not follow that everyone should be spared. The guilty should still be punished appropriately, even if some do escape proper punishment unfairly. The death penalty should apply to killers of black people as well as to killers of whites. High paid, skillful lawyers should not be able to get some defendants off on technicalities. The existence of some systemic problems is no reason to abandon the whole death penalty system.

Reverend Jesse L. Jackson, Sr. President and Chief Executive Officer, Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, Inc. Excerpt from “Legal Lynching: Racism, Injustice & the Death Penalty,” (Marlowe & Company, 1996)

“Who receives the death penalty has less to do with the violence of the crime than with the color of the criminal’s skin, or more often, the color of the victim’s skin. Murder — always tragic — seems to be a more heinous and despicable crime in some states than in others. Women who kill and who are killed are judged by different standards than are men who are murderers and victims.

The death penalty is essentially an arbitrary punishment. There are no objective rules or guidelines for when a prosecutor should seek the death penalty, when a jury should recommend it, and when a judge should give it. This lack of objective, measurable standards ensures that the application of the death penalty will be discriminatory against racial, gender, and ethnic groups.

The majority of Americans who support the death penalty believe, or wish to believe, that legitimate factors such as the violence and cruelty with which the crime was committed, a defendant’s culpability or history of violence, and the number of victims involved determine who is sentenced to life in prison and who receives the ultimate punishment. The numbers, however, tell a different story. They confirm the terrible truth that bias and discrimination warp our nation’s judicial system at the very time it matters most — in matters of life and death. The factors that determine who will live and who will die — race, sex, and geography — are the very same ones that blind justice was meant to ignore. This prejudicial distribution should be a moral outrage to every American.”

Justice Lewis Powell United States Supreme Court Justice excerpts from McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987) (footnotes and citations omitted)

(Mr. McCleskey, a black man, was convicted and sentenced to death in 1978 for killing a white police officer while robbing a store. Mr. McCleskey appealed his conviction and death sentence, claiming racial discrimination in the application of Georgia’s death penalty. He presented statistical analysis showing a pattern of sentencing disparities based primarily on the race of the victim. The analysis indicated that black defendants who killed white victims had the greatest likelihood of receiving the death penalty. Writing the majority opinion for the Supreme Court, Justice Powell held that statistical studies on race by themselves were an insufficient basis for overturning the death penalty.)

“[T]he claim that [t]his sentence rests on the irrelevant factor of race easily could be extended to apply to claims based on unexplained discrepancies that correlate to membership in other minority groups, and even to gender. Similarly, since [this] claim relates to the race of his victim, other claims could apply with equally logical force to statistical disparities that correlate with the race or sex of other actors in the criminal justice system, such as defense attorneys or judges. Also, there is no logical reason that such a claim need be limited to racial or sexual bias. If arbitrary and capricious punishment is the touchstone under the Eighth Amendment, such a claim could — at least in theory — be based upon any arbitrary variable, such as the defendant’s facial characteristics, or the physical attractiveness of the defendant or the victim, that some statistical study indicates may be influential in jury decision making. As these examples illustrate, there is no limiting principle to the type of challenge brought by McCleskey. The Constitution does not require that a State eliminate any demonstrable disparity that correlates with a potentially irrelevant factor in order to operate a criminal justice system that includes capital punishment. As we have stated specifically in the context of capital punishment, the Constitution does not ‘plac[e] totally unrealistic conditions on its use.’ (Gregg v. Georgia)”

The entire decision can be found here.

5 Death Penalty Essays Everyone Should Know

Capital punishment is an ancient practice. It’s one that human rights defenders strongly oppose and consider as inhumane and cruel. In 2019, Amnesty International reported the lowest number of executions in about a decade. Most executions occurred in China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Egypt . The United States is the only developed western country still using capital punishment. What does this say about the US? Here are five essays about the death penalty everyone should read:

“When We Kill”

By: Nicholas Kristof | From: The New York Times 2019

In this excellent essay, Pulitizer-winner Nicholas Kristof explains how he first became interested in the death penalty. He failed to write about a man on death row in Texas. The man, Cameron Todd Willingham, was executed in 2004. Later evidence showed that the crime he supposedly committed – lighting his house on fire and killing his three kids – was more likely an accident. In “When We Kill,” Kristof puts preconceived notions about the death penalty under the microscope. These include opinions such as only guilty people are executed, that those guilty people “deserve” to die, and the death penalty deters crime and saves money. Based on his investigations, Kristof concludes that they are all wrong.

Nicholas Kristof has been a Times columnist since 2001. He’s the winner of two Pulitizer Prices for his coverage of China and the Darfur genocide.

“An Inhumane Way of Death”

By: Willie Jasper Darden, Jr.

Willie Jasper Darden, Jr. was on death row for 14 years. In his essay, he opens with the line, “Ironically, there is probably more hope on death row than would be found in most other places.” He states that everyone is capable of murder, questioning if people who support capital punishment are just as guilty as the people they execute. Darden goes on to say that if every murderer was executed, there would be 20,000 killed per day. Instead, a person is put on death row for something like flawed wording in an appeal. Darden feels like he was picked at random, like someone who gets a terminal illness. This essay is important to read as it gives readers a deeper, more personal insight into death row.

Willie Jasper Darden, Jr. was sentenced to death in 1974 for murder. During his time on death row, he advocated for his innocence and pointed out problems with his trial, such as the jury pool that excluded black people. Despite worldwide support for Darden from public figures like the Pope, Darden was executed in 1988.

“We Need To Talk About An Injustice”

By: Bryan Stevenson | From: TED 2012

This piece is a transcript of Bryan Stevenson’s 2012 TED talk, but we feel it’s important to include because of Stevenson’s contributions to criminal justice. In the talk, Stevenson discusses the death penalty at several points. He points out that for years, we’ve been taught to ask the question, “Do people deserve to die for their crimes?” Stevenson brings up another question we should ask: “Do we deserve to kill?” He also describes the American death penalty system as defined by “error.” Somehow, society has been able to disconnect itself from this problem even as minorities are disproportionately executed in a country with a history of slavery.

Bryan Stevenson is a lawyer, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, and author. He’s argued in courts, including the Supreme Court, on behalf of the poor, minorities, and children. A film based on his book Just Mercy was released in 2019 starring Michael B. Jordan and Jamie Foxx.

“I Know What It’s Like To Carry Out Executions”

By: S. Frank Thompson | From: The Atlantic 2019

In the death penalty debate, we often hear from the family of the victims and sometimes from those on death row. What about those responsible for facilitating an execution? In this opinion piece, a former superintendent from the Oregon State Penitentiary outlines his background. He carried out the only two executions in Oregon in the past 55 years, describing it as having a “profound and traumatic effect” on him. In his decades working as a correctional officer, he concluded that the death penalty is not working . The United States should not enact federal capital punishment.

Frank Thompson served as the superintendent of OSP from 1994-1998. Before that, he served in the military and law enforcement. When he first started at OSP, he supported the death penalty. He changed his mind when he observed the protocols firsthand and then had to conduct an execution.

“There Is No Such Thing As Closure on Death Row”

By: Paul Brown | From: The Marshall Project 2019

This essay is from Paul Brown, a death row inmate in Raleigh, North Carolina. He recalls the moment of his sentencing in a cold courtroom in August. The prosecutor used the term “closure” when justifying a death sentence. Who is this closure for? Brown theorizes that the prosecutors are getting closure as they end another case, but even then, the cases are just a way to further their careers. Is it for victims’ families? Brown is doubtful, as the death sentence is pursued even when the families don’t support it. There is no closure for Brown or his family as they wait for his execution. Vivid and deeply-personal, this essay is a must-read for anyone who wonders what it’s like inside the mind of a death row inmate.

Paul Brown has been on death row since 2000 for a double murder. He is a contributing writer to Prison Writers and shares essays on topics such as his childhood, his life as a prisoner, and more.

You may also like

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

Top 20 Issues Women Are Facing Today

Top 20 Issues Children Are Facing Today

15 Root Causes of Climate Change

15 Facts about Rosa Parks

Abolitionist Movement: History, Main Ideas, and Activism Today

The Biggest 15 NGOs in the UK

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

- Archive Issues

Journal of Practical Ethics

A journal of philosophy, applied to the real world.

The Death Penalty Debate: Four Problems and New Philosophical Perspectives

Masaki Ichinose

The University of Tokyo

This paper aims at bringing a new philosophical perspective to the current debate on the death penalty through a discussion of peculiar kinds of uncertainties that surround the death penalty. I focus on laying out the philosophical argument, with the aim of stimulating and restructuring the death penalty debate.

I will begin by describing views about punishment that argue in favour of either retaining the death penalty (‘retentionism’) or abolishing it (‘abolitionism’). I will then argue that we should not ignore the so-called “whom-question”, i.e. “To whom should we justify the system of punishment?” I identify three distinct chronological stages to address this problem, namely, “the Harm Stage”, “the Blame Stage”, and “the Danger Stage”.

I will also identify four problems arising from specific kinds of uncertainties present in current death penalty debates: (1) uncertainty in harm, (2) uncertainty in blame, (3) uncertainty in rights, and (4) uncertainty in causal consequences. In the course of examining these four problems, I will propose an ‘impossibilist’ position towards the death penalty, according to which the notion of the death penalty is inherently contradictory.

Finally, I will suggest that it may be possible to apply this philosophical perspective to the justice system more broadly, in particular to the maximalist approach to restorative justice.

1. To whom should punishment be justified?

What, exactly, are we doing when we justify a system of punishment? The process of justifying something is intrinsically connected with the process of persuading someone to accept it. When we justify a certain belief, our aim is to demonstrate reasonable grounds for people to believe it. Likewise, when we justify a system of taxation, we intend to demonstrate the necessity and fairness of the system to taxpayers.

What, then, are we justifying when we justify a system of punishment? To whom should we provide legitimate reasons for the system? It is easy to understand to whom we justify punishment when that punishment is administered by, for example, charging a fine. In this case, we persuade violators to pay the fine by bringing to their attention the harm that they have caused, harm which needs to be compensated. (Please note that I am only mentioning the primitive basis of the process of justification.) While we often generalise this process to include people in general or society as a whole, the process of justification would not work without convincing the people who are directly concerned (in this case, violators), at least theoretically, that this is a justified punishment, despite their subjective objections or psychological opposition. We could paraphrase this point per Scanlon’s ‘idea of a justification which it would be unreasonable to reject’ (1982, p.117). That is to say, in justifying the application of the system of punishment, we should satisfy the condition that each person concerned (especially the violator) is aware of having no grounds to reasonably reject the application of the system, even if they do in fact reject it from their personal, self-interested point of view.

In fact, if the violator is not theoretically persuaded at all in any sense—that is, if they cannot understand the justification as a justification—we must consider the possibility that they suffer some disorder or disability that affects their criminal responsibility.

We should also take into account the case of some extreme and fanatical terrorists. They might not understand the physical treatment inflicted on them in the name of punishment as a punishment at all. Rather, they might interpret their being physically harmed as an admirable result of their heroic behaviour. The notion of punishment is not easily applied to these cases, where the use of physical restraint is more like that applied to wild animals. Punishment can be successful only if those who are punished understand the event as punishment.

This line of argument entirely conforms to the traditional context in philosophy concerning the concept of a “person”, who is regarded as the moral and legal agent responsible for his or her actions, including crimes. John Locke, a 17th-century English philosopher, introduced and established this concept, basing it on ‘consciousness’. According to Locke, a person ‘is a thinking intelligent Being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider it self as it self, the same thinking thing in different times and places; which it does only by that consciousness’ (1975, Book 2, Chapter 27, Section 9). This suggests that moral or legal punishments for the person should be accompanied by consciousnesses (in a Lockean sense) of the agent. In other words, when punishment is legally imposed on someone, the person to be punished must be conscious of the punishment as a punishment; that is, the person should understand the event as a justified imposition of some harm. 1

However, there is a problem here, which arises in particular for the death penalty but not for other kinds of punishment. The question that I raise here is ‘to whom do we justify the death penalty?’ People might say it should be justified to society, as the death penalty is one of the social institutions to which we consent, whether explicitly or tacitly. This is true. However, if my claims above about justification are correct, the justification of the death penalty must involve the condemned convict coming to understand the justification at least at a theoretical level. Otherwise, to be executed would not be considered a punishment but rather something akin to the extermination of a dangerous animal. The question I want to focus on in particular is this: should this justification be provided before administering capital punishment or whilst administering capital punishment?

2. ‘Impossibilism’

Generally, in order for the justification of punishment to work, it is necessary for convicts to understand that this is a punishment before it is carried out and that they cannot reasonably reject the justification, regardless of any personal objection they may have. However, that is not sufficient, because if they do not understand at the moment of execution that something harmful being inflicted is a punishment, then its being inflicted would simply result in mere physical harm rather than an institutional response based on theoretical justification. The justification for punishment must be, at least theoretically, accepted both before and during its application. 2 This requirement can be achieved with regard to many types of punishment, such as fines or imprisonment. However, the situation is radically different in the case of the death penalty, for in this case, when it is carried out, the convict, by definition, disappears. During and (in the absence of an afterlife) after the punishment, the convict cannot understand the nature and justification of the punishment. Can we say then that this is a punishment? This is a question which deserves further thought.

On the one hand, the death penalty, once executed, logically implies the nonexistence of the person punished; therefore, by definition, that person will not be conscious of being punished at the moment of execution. However, punishment must be accompanied by the convict’s consciousness or understanding of the significance of the punishment, as far as we accept the traditional concept of the person as a moral and legal agent upon whom punishment could be imposed. It may be suggested that everything leading up to the execution—being on death row, entering the execution chamber, being strapped down—is a kind of punishment that the convict is conscious of and is qualitatively different from mere incarceration. However, those phases are factors merely concomitant with the death penalty. The core essence of being executed lies in being killed or dying. Therefore, if the phases of anticipation were to occur but finally the convict were not killed, the death penalty would not have been carried out. The death penalty logically results in the convict’s not being conscious of being executed, and yet, for it to be a punishment, the death penalty requires the convict to be conscious of being executed. We could notate this in the form of conjunction in the following way in order to make my point as clear as possible:

~ PCE & PCE

(PCE: ‘the person is conscious of being executed under the name of punishment’)

If this is correct, then we must conclude that the concept of the death penalty is a manifest contradiction in terms. In other words, the death penalty should be regarded as conceptually impossible, even before we take part in longstanding debates between retentionism and abolitionism. This purely philosophical view of the death penalty could be called ‘impossibilism’ (i.e. the death penalty is conceptually impossible), and could be classified as a third possible view on the death penalty, distinct from retentionism and abolitionism. A naïve objection against this impossibilist view might counter that the death penalty is actually carried out in some countries so that it is not impossible but obviously possible. The impossibilist answer to this objection is that, based on a coherent sense of what it means for a punishment to be justified, that execution in such countries is not the death penalty but rather unjustified lethal physical violence .

I am not entirely certain whether the ‘impossibilist’ view would truly make sense in the light of the contemporary debates on the death penalty. These debates take place between two camps as I referred to above:

Retentionism (the death penalty should be retained): generally argued with reference to victims’ feelings and the deterrence effects expected by execution.

Abolitionism (the death penalty should be abolished): generally argued through appeals to the cruelty of execution, the possibility of misjudgements in the trial etc.

The grounds mentioned by both camps are, theoretically speaking, applicable to punishment in general in addition to the death penalty specifically. I will mention those two camps later again in a more detailed way in order to make a contrast between standard debates and my own view. However, my argument above for ‘impossibilism’, does suggest that there is an uncertainty specific to the death penalty as opposed to other types of punishment. I believe that this uncertainty must be considered when we discuss the death penalty, at least from a philosophical perspective. Otherwise we may lose sight of what we are attempting to achieve.

A related idea to the ‘impossibilism’ of the death penalty may emerge, if we accept the fact that the death penalty is mainly imposed on those convicted of homicide. This idea is related to the understanding of death proposed by Epicurus, who provides the following argument (Diogenes Laertius 1925, p. 650-1):

Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not. It is nothing, then, either to the living or to the dead, for with the living it is not and the dead exist no longer.

We can call this Epicurean view ‘the harmlessness theory of death’ (HTD). If we accept HTD, it follows, quite surprisingly, that there is no direct victim in the case of homicide insofar as we define ‘victim’ to be a person who suffers harm as a result of a crime. For according to HTD, people who have been killed and are now dead suffer nothing—neither benefits nor harms—because, as they do not exist, they cannot be victims. If this is true, there is no victim in the case of homicide, and it must be unreasonable to impose what is supposed to be the ultimate punishment 3 —that is, the death penalty—on those offenders who have killed others.

This argument might sound utterly absurd, particularly if it is extended beyond offenders and victims to people in general, as one merit of the death penalty seems to lie in reducing people’s fear of death by homicide. However, although this argument from HTD might sound bizarre and counterintuitive, we should accept it at the theoretical level, to the extent that we find HTD valid. 4 Clearly, this argument, which is based on the nonexistence of victims, could logically lead to another impossibilist argument concerning the death penalty.

There are many points to be more carefully examined regarding both types of ‘impossibilism’, which I will skip here. However, I must stop to ponder a natural reaction. My question above, ‘To whom do we justify?’, which introduced ‘impossibilism’, might sound eccentric, because, roughly speaking, theoretical arguments of justification are usually deployed in a generalised way and do not need to acknowledge who those arguments are directed at. Yet, I believe that this normal attitude towards justification is not always correct. Instead, our behaviour, when justifying something, focuses primarily on theoretically persuading those who are unwilling to accept the item being justified. If nobody refuses to accept it, then it is completely unnecessary to provide its justification. For instance, to use a common sense example, nobody doubts the existence of the earth. Therefore, nobody takes it to be necessary to justify the existence of the earth. Alternatively, a justification for keeping coal-fired power generation, the continued use of which is not universally accepted due to global warming, is deemed necessary. In other words, justification is not a procedure lacking a particular addressee, but an activity that addresses the particular person in a definite way, at least at first. In fact, it seems to me that the reason that current debates on the death penalty become deadlocked is that crucial distinctions are not appropriately made. I think that such a situation originates from not clearly asking to whom we are addressing our arguments, or whom we are discussing. As far as I know, there have been very few arguments within the death penalty debate that take into account the homicide victim, despite the victim’s unique status in the issue. This is one example where the debate can be accused of ignoring the ‘whom-question’, so I will clarify this issue by adopting a strategy in which this ‘whom-question’ is addressed.

3. Three chronological stages

Following my strategy, I will first introduce a distinction between three chronological stages in the death penalty. In order to make my argument as simple as possible, I will assume that the death penalty is imposed on those who have been convicted of homicide, although I acknowledge there are other crimes which could result in the death penalty. In that sense, the three stages of the death penalty correspond to the three distinct phases arising from homicide.

The first stage takes place at the time of killing; the fact that someone was killed must be highlighted. However, precisely what happened? If we accept the HTD, we should suppose that nothing harmful happened in the case of homicide. Although counterintuitive, let’s see where this argument leads. However, first, I will acknowledge that we cannot cover all contexts concerning the justification of the death penalty by discussing whether or not killing harms the killed victim. Even if we accept for argument’s sake that homicide does not harm the victim, that is only part of the issue. Other people, particularly the bereaved families of those killed, are seriously harmed by homicide. More generally, society as a whole is harmed, as the fear of homicide becomes more widespread in society.

Moreover, our basic premise, HTD, is controversial. Whether HTD is convincing remains an unanswered question. There is still a very real possibility that those who were killed do suffer harm in a straightforward sense, which conforms to most people’s strong intuition. In any event, we can call this first stage, the ‘Harm Stage’, because harm is what is most salient in this phase, either harm to the victims or others in society at large. If a justification for the death penalty is to take this Harm Stage seriously, the overwhelming focus must be on the direct victims themselves, who actually suffer the harm. This is the central core of the issue, as well as the starting point of all further problems.

The second stage appears after the killing. After a homicide, it is common to blame and to feel anger towards the perpetrator or perpetrators, and this can be described as a natural, moral, or emotional reaction. However, it is not proven that blaming or feeling angry is indeed natural, as it has not been proven that such feelings would arise irrespective of our cultural understanding of the social significance of killing. The phenomenon of blaming and the prevalence of anger when a homicide is committed could be a culture-laden phenomenon rather than a natural emotion. Nevertheless, many people actually do blame perpetrators or feel anger towards them for killing someone, and this is one of the basic ideas used to justify a system of ‘retributive justice’. The core of retributive justice is that punishment should be imposed on the offenders themselves (rather than other people, such as the offenders’ family). This retributive impulse seems to be the most fundamental basis of the system of punishment, even though we often also rely on some consequentialist justification favor punishment (e.g. preventing someone from repeating an offence). In addition, offenders are the recipients of blame or anger from society, which suggests that blaming or expressing anger has a crucial function in retributive justice. I will call this second phase the ‘Blame Stage’, which extends to the period of the execution. Actually, the act of blaming seems to delineate what needs to be resolved in this phase. Attempting to justify the death penalty by acknowledging this Blame Stage (or retributive justification) in terms of proportionality is the most common strategy. That is to say, lex talionis applies here—‘an eye for an eye’. This is the justification that not only considers people in general, including victims who blame perpetrators, but also attempts to persuade perpetrators that this is retribution resulting from their own harmful behaviours.

The final stage in the process concerning the death penalty appears after the execution; in this stage, what matters most is how beneficial the execution is to society. Any system in our society must be considered in the light of its cost-effectiveness. This extends even to cultural or artistic institutions, although at first glance they seem to be far from producing any practical effects. In this context, benefits are interpreted quite broadly; creating intellectual satisfaction, for example, is counted as a benefit. Clearly, this is a utilitarian standpoint. We can apply this view to the system of punishment, or the death penalty, if it is accepted. That is, the death penalty may be justified if its benefits to society are higher than its costs. What, then, are the costs, and what are the benefits? Obviously, we must consider basic expenses, such as the maintenance and labour costs of the institution keeping the prisoner on death row. However, in the case of the death penalty, there is a special cost to be considered, namely, the emotional reaction of people in society in response to killing humans, even when officially sanctioned as a punishment. Some feel that it is cruel to kill a person, regardless of the reason.

On the other hand, what is the expected benefit of the death penalty? The ‘deterrent effect’ is usually mentioned as a benefit that the death penalty can bring about in the future. In that case, what needs to be shown if we are to draw analogies with the previous two stages? When people try to justify the death penalty by mentioning its deterrent effect, they seem to be comparing a society without the death penalty to one with the death penalty. Then they argue that citizens in a society with the death penalty are at less risk of being killed or seriously victimised than those in a society without the death penalty. In other words, the death penalty could reduce the danger of being killed or seriously victimised in the future. Therefore, we could call this third phase the ‘Danger Stage’. In this stage, we focus on the danger that might affect people in the future, including future generations. This is a radically different circumstance from those of the previous two stages in that the Danger Stage targets people who have nothing to do with a particular homicide.

4. Analogy from natural disasters

The three chronological stages that I have presented in relation to the death penalty are found in other types of punishment as well. Initially, any punishment must stem from some level of harm (including harm to the law), and this is a sine qua non for the issue of punishment to arise. Blaming and its retributive reaction must follow that harm, and subsequently some social deterrent is expected to result. However, we should carefully distinguish between the death penalty and other forms of punishment. With other forms of punishment, direct victims undoubtedly exist, and those convicted of harming such victims are aware they are being punished. In addition, rehabilitating perpetrators in order for them to return to society—one aspect of the deterrent effect—can work in principle. However, this aspect of deterrence cannot apply to the death penalty because executed criminals cannot be aware of being punished by definition, and the notion of rehabilitation does not make sense by definition. Only this quite obvious observation can clarify that there is a crucial, intrinsic difference or distinction between the death penalty and other forms of punishment. Theories about the death penalty must seriously consider this difference; we cannot rely on theories that treat the death penalty on a par with other forms of punishment.

Moreover, the three chronological stages that have been introduced above are fundamentally different from each other. In reality, the subjects or people that we discuss and on whom we focus are different from stage to stage. In this respect, one of my points in this article is to underline the crucial need to discuss the issues of the death penalty by drawing a clear distinction between those stages. I am not claiming that only one of those stages is important. I am aware that each stage has its own significance; therefore, we should consider all three. However, we should be conscious of the distinctions when discussing the death penalty.

To make my point more understandable, I will suggest an analogy with natural disasters. Specifically, I will use as an analogy the biggest earthquake in Japan in the past millennium—the quake of 11 March 2011 (hereafter the 2011 quake). Of course, at first glance, earthquakes are substantially different from homicides. However, there is a close similarity between the 2011 quake and homicides, because although most of the harm that occurred was due to the earthquake and tsunami, in fact people were also harmed and killed during the 2011 quake at least partially due to human errors, such as the failure of the government’s policy on tsunamis and nuclear power plants. Thus, it is quite easy in the case of the 2011 quake to distinguish between three aspects, all of which are different from each other.

(1) We must recognise victims who were killed in the tsunami or suffered hardship at shelters. 5 This is the core as well as the starting point of all problems. What matters here is rescuing victims, and expressing our condolences.

(2) Then we will consider victims and people in general who hold the government and the nuclear power company responsible for political and technical mistakes. What usually matters here is the issue of responsibility and compensation.

(3) Finally, we can consider people’s interests in improving preventive measures taken to reduce damages by tsunami and nuclear-plant-related accidents in the future. What matters in this context is the reduction of danger in the future by learning from the 2011 quake.

Nobody will fail to notice that these three aspects are three completely different issues, which can be seen in exactly the same manner in the case of the death penalty. Aspects (1), (2), and (3) correspond respectively to the Harm Stage, the Blame Stage, and the Danger Stage. Undoubtedly, none of these three aspects should be ignored and they actually appear in a mutually intertwined manner: the more successful the preventive measures are, the fewer victims will be produced by tsunami and nuclear-plant accidents in the future. Those aspects affect each other. Likewise, we must consider each of the three stages regarding the death penalty.

5. Initial harm

The arguments thus far provide the basic standpoint that I want to propose concerning the debates on the death penalty. I want to investigate the issue of the death penalty by sharply distinguishing between these three stages and by simultaneously considering them all equally. By following this strategy, I will demonstrate that there are intrinsic uncertainties, and four problems resulting from those uncertainties, in the system of the death penalty. In so doing I will raise a novel objection to the contemporary debate over the death penalty.

Roughly speaking, as I have previously mentioned, the death penalty debate continues to involve the two opposing views of abolitionism and retentionism (or perhaps, in the case of abolitionist countries, revivalism). It seems that the main arguments to support or justify each of the two traditional views (which I have briefly described in section 2 above) have already been exhausted. What matters in this context is whether the death penalty can be justified, and then whether—if it is justifiable—it should be justified in terms of retributivism or utilitarianism. That is the standard way of the debate on the death penalty. For example, when the retributive standpoint is used to justify the death penalty, the notion of proportionality as an element of fairness or social justice might be relevant, apart from the issue of whether proportionality should be measured cardinally or ordinally (see von Hirsch 1993, pp. 6-19). In other words, if one person has killed another, then that person too ought to be killed—that is, executed—in order to achieve fairness. However, as other scholars such as Tonry (1994) have argued, it is rather problematic to apply the notion of proportionality to the practice of punishment because it seems that there is no objective measure of offence, culpability, or responsibility. Rather, the notion of parsimony 6 is often mentioned in these contexts as a more practical and fairer principle than the notion of proportionality.

However, according to my argument above, such debates are inadequate if they are simply applied to the case of the death penalty. Proportionality between which two things is being discussed? Most likely, what is considered here is the proportionality between harm by homicide (where the measured value of offence might be the maximum) and harm by execution. However, I want to reconfirm the essential point. What specifically is the harm of homicide? Whom are we talking about when we discuss the harm of homicide? As I previously argued, citing Epicurus and his HTD, there is a metaphysical doubt about whether we should regard death as harmful. If a person simply disappears when he or she dies and death is completely harmless as HTD claims, then it seems that the retributive justification for the death penalty in terms of proportionality must be nonsense, for nothing at all happens that should trigger the process of crime and punishment. Of course, following HTD, the execution should be similarly regarded as nonsensical. However, if that is the case, the entire institutional procedure, from the perpetrator’s arrest to his or her execution, must be considered a tremendous waste of time, labour, and money.

Some may think that these kinds of arguments are merely empty philosophical abstractions. That may be. However, it is not the case that there is nothing plausible to be considered in these arguments. Consider the issue of euthanasia. Why do people sometimes wish to be euthanised? It is because people can be relieved of a painful situation by dying. That is to say, people wishing to be euthanised take death to be painless, i.e. harmless, in the same manner as HTD. This idea embedded in the case of euthanasia is so understandable that the issue of euthanasia is one of the most popular topics in ethics; however, if so, Epicurus’s HTD should not be taken as nonsensical, for HTD holds in the same way as the idea embedded in the case of euthanasia that when we die, we have neither pain nor any other feeling. What I intend to highlight here is that we must be acutely aware that there is a fundamental problem concerning the notion of harm by homicide, if we want to be philosophically sincere and consistent 7 .