What is PBL?

Project Based Learning (PBL) is a teaching method in which students learn by actively engaging in real-world and personally meaningful projects.

In Project Based Learning, teachers make learning come alive for students.

Students work on a project over an extended period of time – from a week up to a semester – that engages them in solving a real-world problem or answering a complex question. They demonstrate their knowledge and skills by creating a public product or presentation for a real audience.

As a result, students develop deep content knowledge as well as critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and communication skills. Project Based Learning unleashes a contagious, creative energy among students and teachers.

And in case you were looking for a more formal definition...

Project Based Learning is a teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem, or challenge.

Watch Project Based Learning in Action

These 7-10 minute videos show the Gold Standard PBL model in action, capturing the nuts and bolts of a PBL unit from beginning to end.

VIDEO: The Water Quality Project

VIDEO: March Through Nashville

VIDEO: The Tiny House Project

How does pbl differ from “doing a project”.

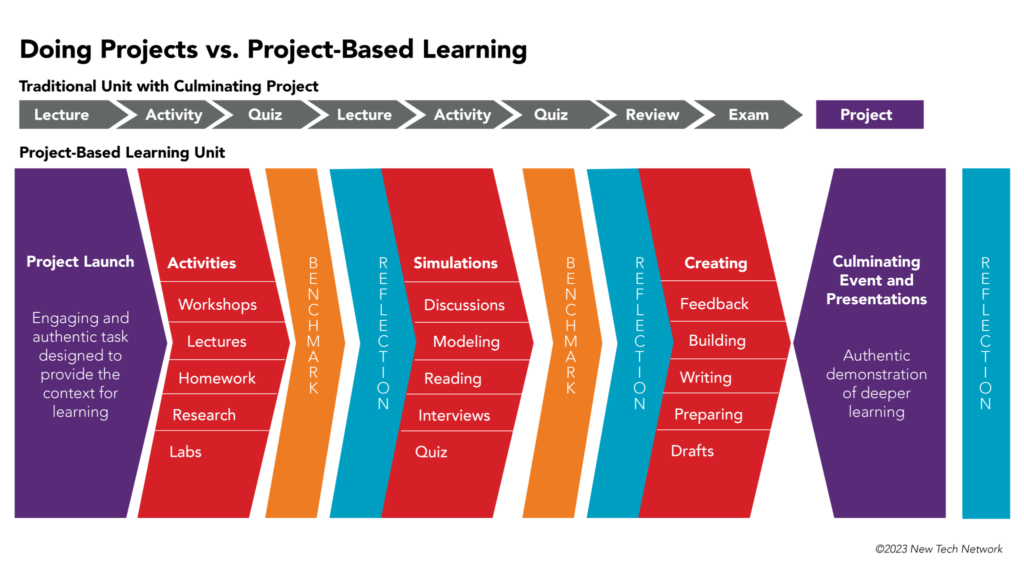

PBL is becoming widely used in schools and other educational settings, with different varieties being practiced. However, there are key characteristics that differentiate "doing a project" from engaging in rigorous Project Based Learning.

We find it helpful to distinguish a "dessert project" - a short, intellectually-light project served up after the teacher covers the content of a unit in the usual way - from a "main course" project, in which the project is the unit. In Project Based Learning, the project is the vehicle for teaching the important knowledge and skills student need to learn. The project contains and frames curriculum and instruction.

In contrast to dessert projects, PBL requires critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, and various forms of communication. To answer a driving question and create high-quality work, students need to do much more than remember information. They need to use higher-order thinking skills and learn to work as a team.

Learn more about "dessert" projects vs PBL

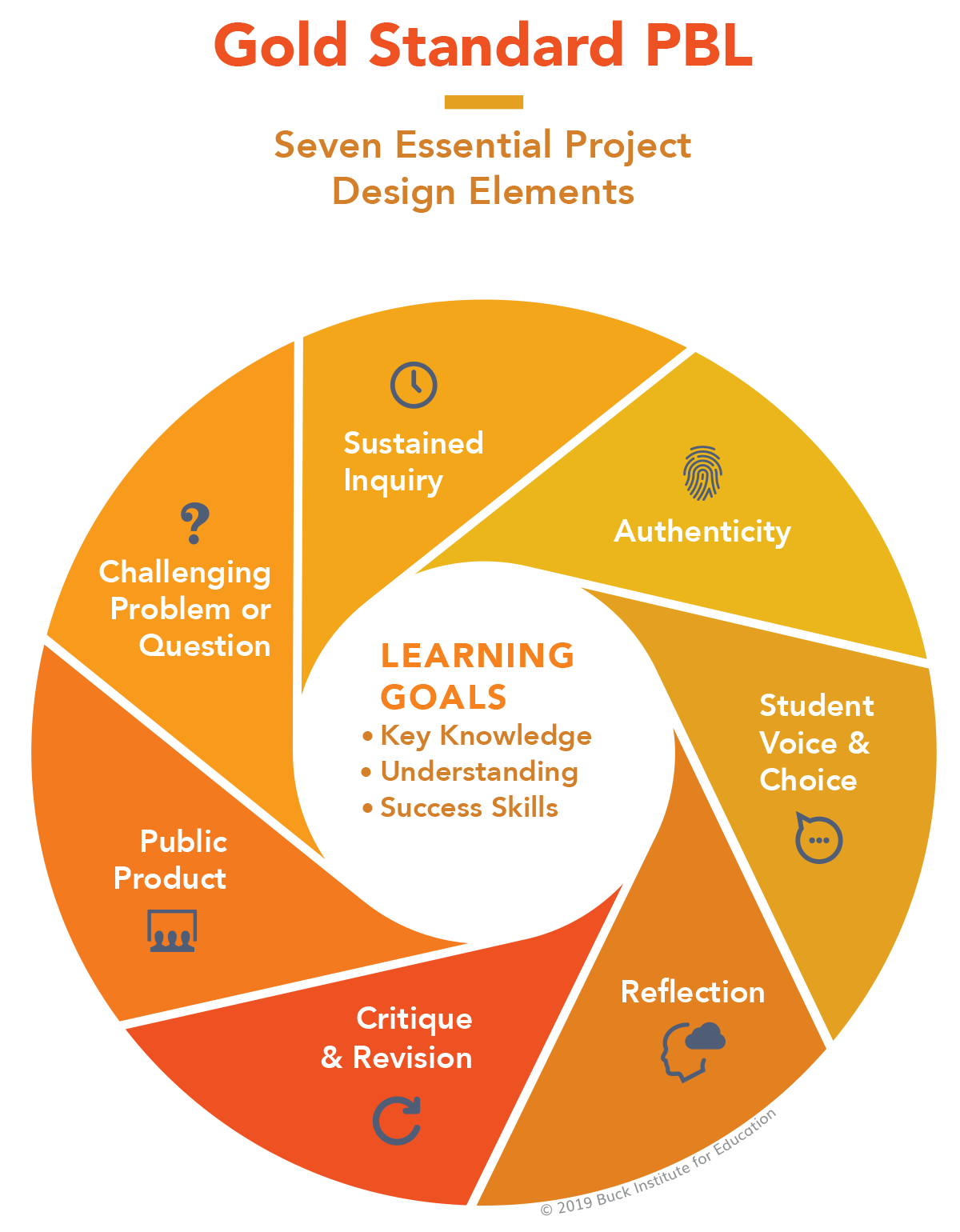

The gold standard for high-quality PBL

To help ensure your students are getting the main course and are engaging in quality Project Based Learning, PBLWorks promotes a research-informed model for “Gold Standard PBL.”

The Gold Standard PBL model encompasses two useful guides for educators:

1) Seven Essential Project Design Elements provide a framework for developing high quality projects for your classroom, and

2) Seven Project Based Teaching Practices help teachers, schools, and organizations improve, calibrate, and assess their practice.

The Gold Standard PBL model aligns with the High Quality PBL Framework . This framework describes what students should be doing, learning, and experiencing in a good project. Learn more at HQPBL.org .

Yes, we provide PBL training for educators! PBLWorks offers a variety of workshops, courses and services for teachers, school and district leaders, and instructional coaches to get started and advance their practice with Project Based Learning. Learn more

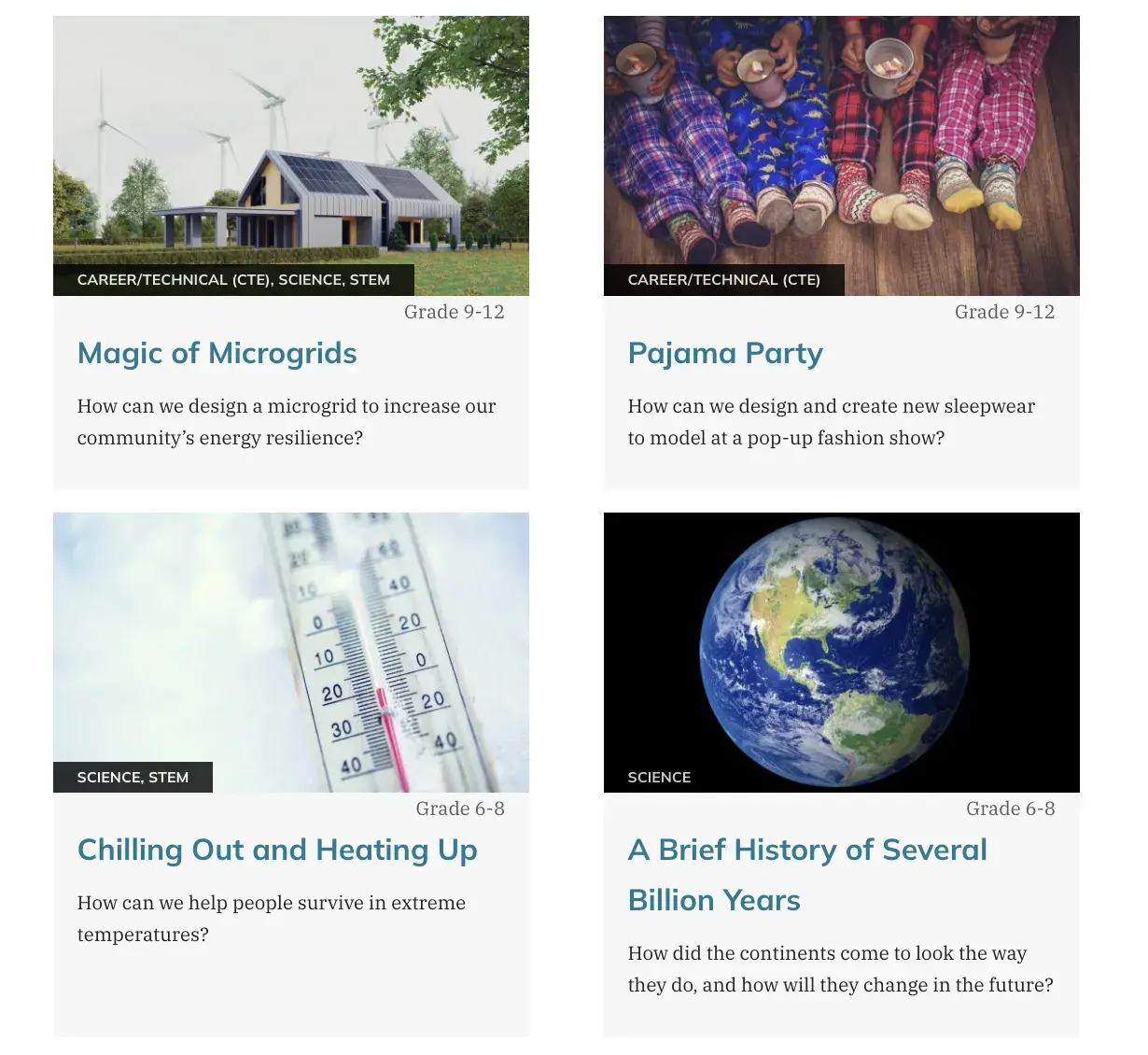

See Sample Projects

Explore our expanding library of project ideas, with over 80 projects that are standards-aligned, and cover a range of grade levels and subject areas.

Don't miss a thing! Get PBL resources, tips and news delivered to your inbox.

Created by the Great Schools Partnership , the GLOSSARY OF EDUCATION REFORM is a comprehensive online resource that describes widely used school-improvement terms, concepts, and strategies for journalists, parents, and community members. | Learn more »

Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning refers to any programmatic or instructional approach that utilizes multifaceted projects as a central organizing strategy for educating students. When engaged in project-based learning, students will typically be assigned a project or series of projects that require them to use diverse skills—such as researching, writing, interviewing, collaborating, or public speaking—to produce various work products, such as research papers, scientific studies, public-policy proposals, multimedia presentations, video documentaries, art installations, or musical and theatrical performances, for example. Unlike many tests, homework assignments, and other more traditional forms of academic coursework, the execution and completion of a project may take several weeks or months, or it may even unfold over the course of a semester or year.

Closely related to the concept of authentic learning , project-based-learning experiences are often designed to address real-world problems and issues, which requires students to investigate and analyze their complexities, interconnections, and ambiguities (i.e., there may be no “right” or “wrong” answers in a project-based-learning assignment). For this reason, project-based learning may be called inquiry-based learning or learning by doing , since the learning process is integral to the knowledge and skills students acquire. Students also typically learn about topics or produce work that integrates multiple academic subjects and skill areas. For example, students may be assigned to complete a project on a local natural ecosystem and produce work that investigates its history, species diversity, and social, economic, and environmental implications for the community. In this case, even if the project is assigned in a science course, students may be required to read and write extensively (English); research local history using texts, news stories, archival photos, and public records (history and social studies); conduct and record first-hand scientific observations, including the analysis and tabulation of data (science and math); and develop a public-policy proposal for the conservation of the ecosystem (civics and government) that will be presented to the city council utilizing multimedia technologies and software applications (technology).

In project-based learning, students are usually given a general question to answer, a concrete problem to solve, or an in-depth issue to explore. Teachers may then encourage students to choose specific topics that interest or inspire them, such as projects related to their personal interests or career aspirations. For example, a typical project may begin with an open-ended question (often called an “essential question” by educators): How is the principle of buoyancy important in the design and construction of a boat? What type of public-service announcement will be most effective in encouraging our community to conserve water? How can our school serve healthier school lunches? In these cases, students may be given the opportunity to address the question by proposing a project that reflects their interests. For example, a student interested in farming may explore the creation of a school garden that produces food and doubles as a learning opportunity for students, while another student may choose to research health concerns related to specific food items served in the cafeteria, and then create posters or a video to raise awareness among students and staff in the school.

In public schools, the projects, including the work products created by students and the assessments they complete, will be based on the same state learning standards that apply to other methods of instruction—i.e., the projects will be specifically designed to ensure that students meet expected learning standards. While students work on a project, teachers typically assess student learning progress—including the achievement of specific learning standards—using a variety of methods, such as portfolios , demonstrations of learning , or rubrics , for example. While the learning process may be more student-directed than some traditional learning experiences, such as lectures or quizzes, teachers still provide ongoing instruction, guidance, and academic support to students. In many cases, adult mentors, advisers, or experts from the local community—such as scientists, elected officials, or business leaders—may be involved in the design of project-based experiences, mentor students throughout the process, or participate on panels that review and evaluate the final projects in collaboration with teachers.

As a reform strategy, project-based learning may become an object of debate both within a school or in the larger community. Schools that decide to adopt project-based learning as their primary method of instruction, as opposed to schools that are founded on the philosophy and use the method from their inception, are more likely to encounter criticism or resistance. The instructional nuances of project-based learning can also become a source of confusion and misunderstanding, given that the approach represents a fairly significant departure from more familiar conceptions of schooling.

In addition, there may be debate among educators about what specifically does and doesn’t constitute “project-based learning.” For example, some teachers may already be doing “projects” in their courses, and they might consider these activities to be a form of project-based learning, but others may dispute such claims because the projects do not conform to their more specific and demanding definition—i.e., they are not “authentic” forms of project-based learning since they don’t meet the requisite instructional criteria (such as the features described above).

The following are a few representative examples of the kinds of arguments typically made by advocates of project-based learning:

- Project-based learning gives students a more “integrated” understanding of the concepts and knowledge they learn, while also equipping them with practical skills they can apply throughout their lives. The interdisciplinary nature of project-based learning helps students make connections across different subjects, rather than perceiving, for example, math and science as discrete subjects with little in common.

- Because project-based learning mirrors the real-world situations students will encounter after they leave school, it can provide stronger and more relevant preparation for college and work. Student not only acquire important knowledge and skills, they also learn how to research complex issues, solve problems, develop plans, manage time, organize their work, collaborate with others, and persevere and overcome challenges, for example.

- Project-based learning reflects the ways in which today’s students learn. It can improve student engagement in school, increase their interest in what is being taught, strengthen their motivation to learn, and make learning experiences more relevant and meaningful.

- Since project-based learning represents a more flexible approach to instruction, it allows teachers to tailor assignments and projects for students with a diverse variety of interests, career aspirations, learning styles, abilities, and personal backgrounds. For related discussions, see differentiation and personalized learning .

- Project-based learning allows teachers and students to address multiple learning standards simultaneously. Rather than only meeting math standards in math classes and science standards in science classes, students can work progressively toward demonstrating proficiency in a variety of standards while working on a single project or series of projects. For a related discussion, see proficiency-based learning .

The following are few representative examples of the kinds of arguments that may be made by critics of project-based learning:

- Project-based learning may not ensure that students learn all the required material and standards they are expected to learn in a course, subject area, or grade level. When a variety of subjects are lumped together, it’s more difficult for teachers to monitor and assess what students have learned in specific academic subjects.

- Many teachers will not have the time or specialized training required to use project-based learning effectively. The approach places greater demands on teachers—from course preparation to instructional methods to the evaluation of learning progress—and schools may not have the funding, resources, and capacity they need to adopt a project-based-learning model.

- The projects that students select and design may vary widely in academic rigor and quality. Project-based learning could open the door to watered-down learning expectations and low-quality coursework.

- Project-based learning is not well suited to students who lack self-motivation or who struggle in less-structured learning environments .

- Project-based learning raises a variety of logistical concerns, since students are more likely to learn outside of school or in unsupervised settings, or to work with adults who are not trained educators.

Alphabetical Search

The Comprehensive Guide to Project-Based Learning: Empowering Student Choice through an Effective Teaching Method

Our network.

Resources and Tools

In K-12 education, project-based learning (PBL) has gained momentum as an effective inquiry-based, teaching strategy that encourages students to take ownership of their learning journey.

By integrating authentic projects into the curriculum, project-based learning fosters active engagement, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. This comprehensive guide explores the principles, benefits, implementation strategies, and evaluation techniques associated with project-based instruction, highlighting its emphasis on student choice and its potential to revolutionize education.

What is Project-Based Learning?

Project-based learning (PBL) is a inquiry-based and learner-centered instructional approach that immerses students in real-world projects that foster deep learning and critical thinking skills. Project-based learning can be implemented in a classroom as single or multiple units or it can be implemented across various subject areas and school-wide.

In contrast to teacher led instruction, project-based learning encourages student engagement, collaboration, and problem-solving, empowering students to become active participants in their own learning. Students collaborate to solve a real world problem that requires content knowledge, critical thinking, creativity, and communication skills.

Students aren’t only assessed on their understanding of academic content but on their ability to successfully apply that content when solving authentic problems. Through this process, project-based learning gives students the opportunity to develop the real-life skills required for success in today’s world.

Positive Impacts of Project-Based Learning

By integrating project-based learning into the classroom, educators can unlock a multitude of benefits for students. The research evidence overwhelmingly supports the positive impact of PBL on students, teachers, and school communities. According to numerous studies (see Deutscher et al, 2021 ; Duke et al, 2020 ; Krajick et al, 2022 ; Harris et al, 2015 ) students in PBL classrooms not only outperform non-PBL classrooms academically, such as on state tests and AP exams, but also the benefits of PBL extend beyond academic achievement, as students develop essential skills, including creativity, collaboration, communication, and critical thinking. Additional studies documenting the impact of PBL on K-12 learning are available in the PBL research annotated bibliography on the New Tech Network website.

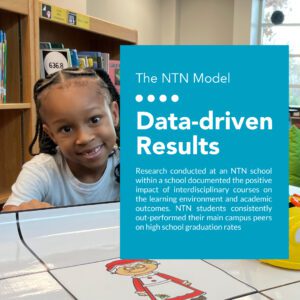

New Tech Network Project-Based Learning Impacts

Established in 1996, New Tech Network NTN is a leading nonprofit organization dedicated to transforming teaching and learning through innovative instructional practices, with project-based learning at its core.

NTN has an extensive network of schools across the United States that have embraced the power of PBL to engage students in meaningful, relevant, and challenging projects, with professional development to support teachers in deepening understanding of “What is project-based learning?” and “How can we deliver high quality project-based learning to all students?”

With over 20 years of experience in project-based learning, NTN schools have achieved impactful results. Several research studies documented that students in New Tech Network schools outperform their peers in non-NTN schools on SAT/ACT tests and state exams in both math and reading (see Hinnant-Crawford & Virtue, 2019 ; Lynch et al, 2018 ; Stocks et al, 2019 ). Additionally, students in NTN schools are more engaged and more likely to develop skills in collaboration, agency, critical thinking, and communication—skills highly valued in today’s workforce (see Ancess & Kafka, 2020 ; Muller & Hiller, 2020 ; Zeiser, Taylor, et al, 2019 ).

NTN provides comprehensive support to educators, including training, resources, and ongoing coaching, to ensure the effective implementation of problem-based learning and project-based learning. Through their collaborative network, NTN continuously shares best practices, fosters innovation, enables replication across districts, and empowers educators to create transformative learning experiences for their students (see Barnett et al, 2020 ; Hernández et al, 2019 ).

Key Concepts of Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning is rooted in several key principles that distinguish it from other teaching methods. The pedagogical theories that underpin project-based learning and problem-based learning draw from constructivism and socio-cultural learning. Constructivism posits that learners construct knowledge through active learning and real world applications. Project-based learning aligns with this theory by providing students with opportunities to actively construct knowledge through inquiry, hands-on projects, real-world contexts, and collaboration.

Students as active participants

Project-based learning is characterized by learner-centered, inquiry-based, real world learning, which encourages students to take an active role in their own learning. Instead of rote memorization of information, students engage in meaningful learning opportunities, exercise voice and choice, and develop student agency skills. This empowers students to explore their interests, make choices, and take ownership of their learning process, with teachers acting as facilitators rather than the center of instruction.

Real-world and authentic contexts

Project-based learning emphasizes real-world problems that encourage students to connect academic content to meaningful contexts, enabling students to see the practical application of what they are learning. By tackling personally meaningful projects and engaging in hands-on tasks, students develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter and its relevance in their lives.

Collaboration and teamwork

Another essential element of project-based learning is collaborative work. Students collaborating with their peers towards the culmination of a project, mirrors real-world scenarios where teamwork and effective communication are crucial. Through collaboration, students develop essential social and emotional skills, learn from diverse perspectives, and engage in constructive dialogue.

Project-based learning embodies student-centered learning, real-world relevance, and collaborative work. These principles, rooted in pedagogical theories like constructivism, socio-cultural learning, and experiential learning, create a powerful learning environment, across multiple academic domains, that foster active engagement, thinking critically, and the development of essential skills for success in college or career or life beyond school.

A Unique Approach to Project-Based Learning: New Tech Network

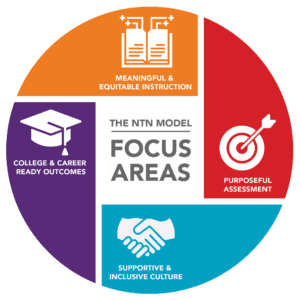

New Tech Network schools are committed to these key focus areas: college and career ready outcomes, supportive and inclusive culture, meaningful and equitable instruction, and purposeful assessment.

In the New Tech Network Model, rigorous project-based learning allows students to engage with material in creative, culturally relevant ways, experience it in context, and share their learning with peers.

Why Undertake this Work?

Teachers, administrators, and district leaders undertake this work because it produces critical thinkers, problem-solvers, and collaborators who are vital to the long-term health and wellbeing of our communities.

Reynoldsburg City Schools (RCS) Superintendent Dr. Melvin J. Brown observed that “Prior to (our partnership with New Tech Network) we were just doing the things we’ve always done, while at the same time, our local industry was evolving and changing— and we were not changing with it. We recognized we had to do better to prepare kids for the reality they were going to walk into after high school and beyond.

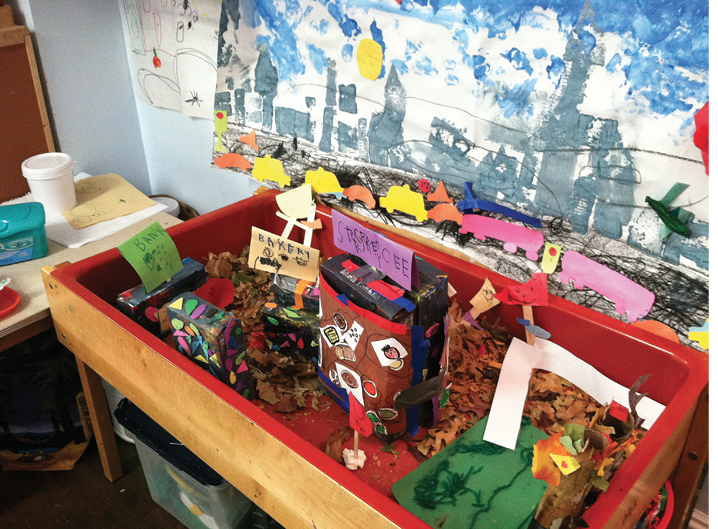

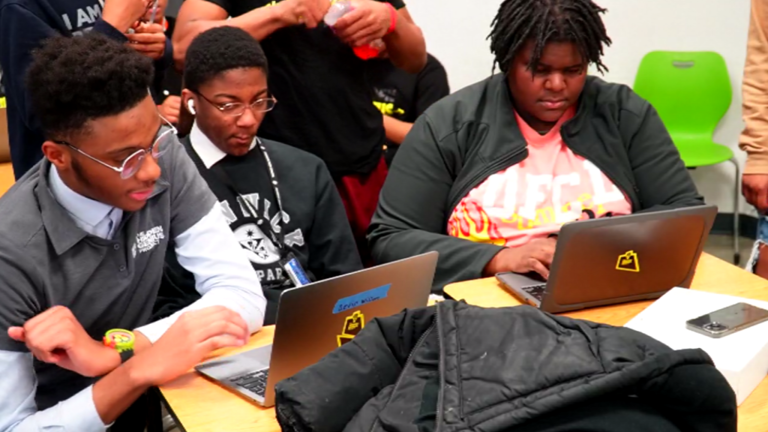

Students embrace the Model because they feel a sense of belonging. They are challenged to learn in relevant, meaningful ways that shape the way they interact with the world, like these students from Owensboro Innovation Academy in Owensboro, Kentucky .

When change is collectively held and supported rather than siloed, and all stakeholders are engaged rather than alienated, schools and districts build their own capacity to sustain innovation and continuously improve. New Tech Network’s approach to change provides teachers, administrators, and district leaders with clear roles in adopting and adapting student-centered learning.

Part of NTN’s process for equipping schools with the data they need to serve their students involves conducting research surveys about their student’s experiences.

“The information we received back from our NTN surveys about our kids’ experiences was so powerful,” said Amanda Ziaer, Managing Director of Strategic Initiatives for Frisco ISD. “It’s so helpful to be reminded about these types of tactics when you’re trying to develop an authentic student-centered learning experience. It’s just simple things you might skip because we live in such a traditional adult-centered world.”

NTN’s experienced staff lead professional development activities that enable educators to adapt to student needs and strengths, and amplify those strengths while adjusting what is needed to address challenges.

Meaningful and Equitable Instruction

The New Tech Network model is centered on a PBL instructional core. PBL as an instructional method overlaps with key features of equitable pedagogical approaches including student voice, student choice, and authentic contexts. The New Tech Network model extends the power of PBL as a tool for creating more equitable learning by building asset-based equity pedagogical practices into the the design using key practices drawn from the literature on culturally sustaining teaching methods so that PBL instruction leverages the assets of diverse students, supports teachers as warm demanders, and develops critically conscious students in PBL classrooms (see Good teaching, warm and demanding classrooms, and critically conscious students: Measuring student perceptions of asset-based equity pedagogy in the classroom ).

Examples of Project-Based Learning

New Tech Network schools across the country create relevant projects and interdisciplinary learning that bring a learner-centered approach to their school. Examples of NTN Model PBL Projects are available in the NTN Help and Learning Center and enable educators to preview projects and gather project ideas from various grade levels and content areas.

The NTN Project Planning Toolkit is used as a guide in the planning and design of PBL. The Project-based learning examples linked above include a third grade Social Studies/ELA project, a seventh grade Science project, and a high school American Studies project (11th grade English Language Arts/American History).

The Role of Technology in Project-Based Learning

A tool for creativity

Technology plays a vital role in enhancing PBL in schools, facilitating student engagement, collaboration, and access to information. At the forefront, technology provides students with tools and resources to research, analyze data, and create multimedia content for their projects.

A tool for collaboration

Technology tools enable students to express their understanding creatively through digital media, such as videos, presentations, vlogs, blogs and interactive websites, enhancing their communication and presentation skills.

A tool for feedback

Technology offers opportunities for authentic audiences and feedback. Students can showcase their projects to a global audience through online platforms, blogs, or social media, receiving feedback and perspectives from beyond the classroom. This authentic audience keeps students engaged and striving for high-quality work and encourages them to take pride in their accomplishments.

By integrating technology into project-based learning, educators can enhance student engagement, deepen learning, and prepare students for a digitally interconnected world.

Interactive PBL Resources

New Tech Network offers a wealth of resources to support educators in gaining a deeper understanding of project-based learning. One valuable tool is the NTN Help Center, which provides comprehensive articles and resources on the principles and practices of implementing project-based learning.

Educators can explore project examples in the NTN Help Center to gain inspiration and practical insights into designing and implementing PBL projects that align with their curriculum and student needs.

Educators can start with the article “ What are the basic principles and practices of Project-Based Learning? Doing Projects vs. PBL . ” The image within the article clarifies the difference between the traditional education approach of “doing projects” and true project-based learning.

Project Launch

Students are introduced to a project by an Entry Event in the Project Launch (designated in purple on the image) this project component typically requires students to take on a role beyond that of ‘student’ or ‘learner’. This occurs either by placing students in a scenario that has real world applications, in which they simulate tasks performed by adults and/or by requiring learners to address a challenge or problem facing a particular community group.

The Entry Event not only introduces students to a project but also serves as the “hook” that purposefully engages students in the launch of a project. The Entry Event is followed by the Need to Know process in which students name what they already know about a topic and the project ask and what they “need to know” in order to solve the problem named in the project. Next steps are created which support students as they complete the Project Launch phase of a project.

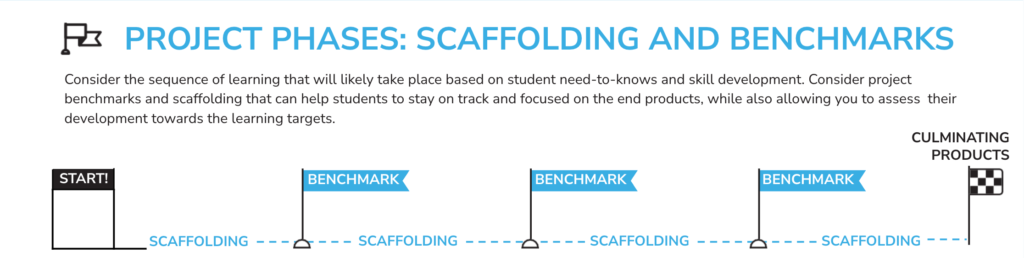

Scaffolding

Shown in the image in red, facilitators ensure students gain content knowledge and skills through ‘scaffolding’. Scaffolding is defined as temporary supports for students to build the skills and knowledge needed to create the final product. Similar to scaffolding in building construction, it is removed when these supports are no longer needed by students.

Scaffolding can take the form of a teacher providing support by hosting small group workshops, students engaging in independent research or groups completing learner-centered activities, lab investigations, formative assessments and more.

Benchmarks (seen in orange in the image) can be checks for understanding that allow educators to give feedback on student work and/or checks to ensure students are progressing in the project as a team. After each benchmark, students should be given time to reflect on their individual goals as well as their team goals. Benchmarks are designed to build on each other to support project teams towards the culminating product at the end of the project.

NTN’s Help Center also provides resources on what effective teaching and learning look like within the context of project-based learning. The article “ What does effective teaching and learning look like? ” outlines the key elements of a successful project-based learning classroom, emphasizing learner-centered learning, collaborative work, and authentic assessments.

Educators can refer to this resource to gain insights into best practices, instructional strategies, and classroom management techniques that foster an engaging and effective project-based learning environment.

From understanding the principles and practices of PBL to accessing examples of a particular project, evaluating project quality, and exploring effective teaching and learning strategies, educators can leverage these resources to enhance their PBL instruction and create meaningful learning experiences for their students.

Preparing Students for the Future with PBL

The power of PBL is the way in which it encourages students to think critically, collaborate, and sharpen communication skills, which are all highly sought-after in today’s rapidly evolving workforce. By engaging in authentic, real-world projects, and collaborating with business and community leaders and community members, students develop the ability to tackle complex problems, think creatively, and adapt to changing circumstances.

These skills are essential in preparing students for the dynamic and unpredictable nature of the future job market, where flexibility, innovation, and adaptability are paramount.

“Joining New Tech Network provides us an opportunity to reframe many things about the school, not just PBL,” said Bay City Public Schools Chief Academic Officer Patrick Malley. “Eliminating the deficit mindset about kids is the first step to establishing a culture that makes sure everyone in that school is focused on next-level readiness for these kids.”

The New Tech Network Learning Outcomes align with the qualities companies are looking for in new hires: Knowledge and Thinking, Oral Communication, Written Communication, Collaboration and Agency.

NTN schools prioritize equipping students with the necessary skills and knowledge to pursue postsecondary education or training successfully. By integrating college readiness and career readiness into the fabric of PBL, NTN ensures that students develop the academic, technical, and professional skills needed for future success.

Through authentic projects, students learn to engage in research, analysis, and presentation of their work, mirroring the expectations and demands of postsecondary education and the workplace. NTN’s commitment to college and career readiness ensures that students are well-prepared to transition seamlessly into higher education or enter the workforce with the skills and confidence to excel in their chosen paths.

The Impact of PBL on College and Career Readiness

PBL has a profound impact on college and career readiness. Numerous studies document the academic benefits for students, including performance in AP courses, SAT/ACT tests, and state exams (see Deutscher et al, 2021 ; Duke et al, 2020 ; Krajick et al, 2022 ; Harris et al, 2015 ). New Tech Network schools demonstrate higher graduation rates and college persistence rates than the national average as outlined in the New Tech Network 2022 Impact Report . Over 95% of NTN graduates reported feeling prepared for the expectations and demands of college.

Practices that Support Equitable College Access and Readiness

According to a literature review conducted by New York University’s Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools ( Perez et al, 2021 ) classroom level, school level, and district level practices can be implemented to create more equitable college access and readiness and these recommendations align with many of the practices built into the the NTN model, including culturally sustaining instructional approaches, foundational literacy, positive student-teacher relationships, and developing shared asset-based mindsets.

About New Tech Network

New Tech Network is committed to meeting schools and districts where they are and helping them achieve their vision of student success. For a full list of our additional paths to impact or to speak with someone about how the NTN Model can make an impact in your district, please send an email to [email protected] .

Sign Up for the NTN Newsletter

What Is Project-Based Learning?

Experts say the real-world approach to learning resonates, and studies show it is effective.

Getty Images

Project-based learning is active, and leads to deeper engagement and understanding.

Gil Leal took AP Environmental Science taught with a project-based learning approach at San Pedro Senior High School Marine Science Magnet in Los Angeles.

One project involved students working in teams to design a farm. They researched issues including water management, pest control and demand for agricultural products. Students then incorporated that knowledge into their design, Leal says in a panel discussion on project-based learning. Now a sophomore at the University of California—Los Angeles , Leal says the class convinced him to major in environmental science.

“The projects made class really cool and engaging and memorable, and we got to visit a real strawberry farm,” Leal told the George Lucas Educational Foundation .

Unlike traditional school projects that often take place at the end of a unit, project-based learning, or PBL, is an educational philosophy that calls upon students to take on a real-world question – such as how to best design a farm – and explore it over a period of weeks. Teachers incorporate grade-level instruction into the project, which is designed to meet academic goals and standards, and students learn content and skills while working collaboratively, thinking critically and often revising their work. At the end, that work is shared publicly.

“Project-based learning is not the activity at the end, it’s the activity at the beginning that drives the learning and builds the engagement,” says Kristin De Vivo, executive director of Lucas Education Research , a division of the George Lucas Educational Foundation.

Studies Show PBL Is Effective

The foundation, created by the famous filmmaker, works to improve K-12 education and recently released research showing that project-based learning can be extremely effective.

Four studies released in February by Lucas Education Research, along with researchers from five major universities, showed that students in project-based learning classrooms across the United States significantly outperformed students in typical classrooms.

In a study involving high schoolers, students taught AP U.S. Government and Politics and AP Environmental Science with a project-based learning approach outperformed peers on AP exams by 8 percentage points in the first year and were more likely to earn a passing score of 3 or above, giving them a chance to receive college credit. In the second year, the gap widened to 10 percentage points. One key finding of the study, which included large urban school districts, was that the higher scores were seen among both students of color and those from lower-income households.

Similar results were found in a study involving third graders studying science. Students from a variety of backgrounds in project-based learning classrooms scored 8 percentage points higher than peers on a state science test. These results held regardless of a student’s reading level.

Project-Based Learning Is ‘Active’

Project-based learning succeeds across income groups because it involves active learning, which leads to deeper engagement and understanding, according to De Vivo.

“Engagement is the gateway to all learning,” De Vivo says. “When students are able to construct knowledge, not given an answer, that active learning wakes up the brain.”

Suppose third grade students are asked why a toy car moves faster on a wood floor than on a carpet, and the students get on the floor with a toy car to explore that question. Later, when they are asked how friction works, their answer will draw upon personal experimentation.

In the case of high schoolers taking AP classes, the project-based approach encourages teamwork, productive debate, problem solving and creativity. Education experts also say it helps develop skills and confidence.

Teachers Facilitate Student Ownership

What is distinct about project-based learning is that teachers take the role of facilitators while the students do the research, modeling and building. This gives students ownership over ideas and projects, according to Billie Freeland and Nicole Andreas, co-teachers of K-5 STEM classes at Kent City Community Schools in Michigan. Freeland, Andreas and a group of third graders participated in the Lucas Education Research study, working with Michigan State University .

The challenge for their fourth graders in the 2020-21 school year was to design something that uses alternative energy sources to help their community. One student designed a truck that used steam as fuel and picked up trash. Another student designed a solar-powered fan to protect apple blossoms in the spring.

“This challenges us as teachers to direct students in unique paths to learning,” Freeland and Andreas wrote in an email. “We also love the deep connectedness to real-world issues and problems that are addressed through the curriculum.”

Training for Teachers

For project-based learning to work, teachers first need professional training in how to deliver course content. PBLWorks, a leader in project-based learning methodology, trained the teachers who taught the AP classes involved in the Lucas studies. It offers workshops and courses for teachers and administrators.

Based on the results of the Lucas research, the College Board, which administers the AP exams, launched workshops this summer in project-based learning for AP U.S. Government and Politics and AP Environmental Science teachers. PBLWorks designed and ran the workshops; teachers from schools where half of the students are either low-income or minorities could attend free of charge. A total of 493 educators participated in the workshops, including 63 from high-need schools, Sally Kingston, chief impact officer at PBLWorks, wrote in an email.

Training is also offered by the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education , the High Tech High Graduate School of Education in San Diego, and the EL Education network of schools.

A few public school districts around the country have implemented project-based learning, including Manchester School District in New Hampshire, Pearl City-Waipahu Complex Area in Hawaii, and San Francisco Unified School District, which embraced it after participating in one of the Lucas studies. Education experts say project-based learning has a lot of room to grow, especially after students have endured a year of virtual schooling thanks to the pandemic.

“Parents have woken up to the fact that school is not preparing our kids for the 21st century,” De Vivo says.

Searching for a school? Explore our K-12 directory .

10 Books to Read Before College

Tags: K-12 education , elementary school , parenting , students , education

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

Popular Stories

Best Colleges

College Admissions Playbook

You May Also Like

Choosing a high school: what to consider.

Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

Metro Areas With Top-Ranked High Schools

A.R. Cabral April 23, 2024

States With Highest Test Scores

Sarah Wood April 23, 2024

Map: Top 100 Public High Schools

Sarah Wood and Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

U.S. News Releases High School Rankings

Explore the 2024 Best STEM High Schools

Nathan Hellman April 22, 2024

See the 2024 Best Public High Schools

Joshua Welling April 22, 2024

Ways Students Can Spend Spring Break

Anayat Durrani March 6, 2024

Attending an Online High School

Cole Claybourn Feb. 20, 2024

How to Perform Well on SAT, ACT Test Day

Cole Claybourn Feb. 13, 2024

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Getting Started with Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning (PBL) actively involves students in their learning and prepares them for the world beyond the classroom. It is a dynamic approach to teaching in which instructors play an important role in structuring the learning experience, guiding students as they work to find solutions to complex interdisciplinary problems in collaboration with diverse peers, and developing skills and acquiring knowledge throughout the process.

This resource offers an introductory overview of PBL, including the key features and questions for reflection as instructors develop their project-based teaching practices.

On this page:

What is pbl.

- Developing Your Project-Based Teaching Approach

- References and Resources

The CTL is here to help!

Want to implement project-based learning in your course or curriculum? Looking for more information about what makes for effective project-based learning? The CTL is here to help! Email [email protected] to schedule a 1-1 consultation!

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2022). Getting Started with Project-Based Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/project-based-learning/

Project-Based Learning (PBL) is “a teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem, or challenge” ( PBLWorks ). PBL is often thought of as a valuable framework for capstone courses, in which students demonstrate the knowledge and skills they developed through their coursework; however, PBL can also be effective in courses throughout students’ academic careers, including as early as the first year (Wobbe and Stoddard, 2019).

PBL is distinct from assigning a project in a course: Assigned projects tend to be short-term, occurring after an instructor has covered the content of a unit of study, are focused on the product that students deliver (often individually), and are a summative assessment . In contrast, for PBL, the project serves as the “vehicle for teaching the important knowledge and skills students need to learn”; the project frames curriculum and instruction ( What is Project-Based Learning ). PBL is driven by student inquiry, and involves collaboration with peers and in-class guidance from the instructor. There is emphasis placed on the project process , not just a final deliverable; this emphasis helps provide students with a formative assessment experience, where the learning and feedback happen throughout the project. For more, see the Framework for High Quality Project Based Learning , which includes six elements of effective PBL as identified by High Quality PBL ( HQPBL ), an organization of international educational experts.

PBL connects theory to practice and engages students in direct action: With PBL, students are asked to think deeply and critically about a complex problem, question, or issue that does not have a single answer. Over the course of the project, students engage with and learn more about important content, concepts, and skills. As students work through these real-world problems that are meaningful and relevant to their lives and futures, and develop possible solutions, PBL helps them take more ownership and responsibility of their own learning. Students develop transferable skills such as critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, project management, communication, and problem-solving. They build their confidence in their abilities and “the personal agency needed to tackle life’s and the world’s challenges” ( HQPBL Framework , 2). Research has also shown that PBL can result in “greater student learning gains,” particularly for students from underrepresented groups ( PBL in Higher Education ).

PBL is learner-centered and guided by instructors: PBL requires rethinking more traditional classroom approaches as students become more active and participatory learners. In PBL, students drive the inquiry and discovery while instructors serve as guides or mentors. By designing, planning, and implementing a PBL curriculum, instructors engage students and coach them through the PBL process. Instructors help students identify their needs and access resources to address potential gaps. Instructors also play an important role in helping students develop collaboration and project management skills, which are critical to students’ success in PBL.

Developing Your Project-Based Teaching Practices

You, the instructor, play a critical role in ensuring effective PBL. This section is structured around the Gold Standard Project Based Teaching Practices from PBLWorks, and includes questions for you to reflect on as you develop your approach.

Design for authenticity and agency: With consideration of your course context, the course learning objectives, and the needs of your students, what project could you have students work on throughout the course? What room will there be for student voice, choice, and input in the project? Who is the audience for the final deliverable? How will you communicate this to your students?

Build the culture for collaboration: For many students, a PBL approach could be new and their past experiences working in groups may be fraught. The expectation of PBL is that each individual student will contribute to all aspects of the project and will respect and learn from each other’s contributions. How might you work with your students to establish expectations and build class community? How will you support student collaborations?

Scaffold student learning: Instructors scaffold project elements and subtasks to help students build upon the work they’re doing. How will you guide students toward the culminating project? How might students take on greater responsibility over the course of the project?

Manage teams and project activities: While students are expected to take ownership of their projects and their work, and learn to use the processes, tools, and strategies of project management, instructors help students as they work collaboratively and define and set project deadlines and subtasks. How will you help your students develop collaboration and project management skills?

Provide feedback : Instructors provide students with feedback on their progress throughout the course of a project. What opportunities will there be for ongoing formative feedback (e.g., written feedback, check-in meetings, facilitating peer- or self-assessment activities)? How might students and external stakeholders be part of this feedback process?

Create opportunities for reflection: Students engage in ongoing reflection on their learning and progress throughout the project. How might students be encouraged to think about what they are doing, assess the quality of their work, and identify ways to improve?

Showcase student work: An important feature of PBL is students having an opportunity to showcase their work. How might you create opportunities for the showcase of student work? Are there campus-wide initiatives you might encourage students to participate in? What kinds of in-class activities or opportunities might you offer for students?

Collect feedback: Just as it’s important for instructors to provide students with feedback throughout the process, it’s equally important to collect feedback from students. How might you invite feedback from students throughout the process? What opportunities will you create for responding to and implementing feedback in the moment? How might you consider this feedback in future course iterations?

Whether you are trying to determine if PBL makes sense for your course, looking for feedback on your PBL practices, or beginning the process of implementation, the CTL is here to help! Email [email protected] to schedule a 1-1 consultation.

References and Resources

PBL in Action Resources

Worcester Polytechnic Institute’s (WPI) Center for Project Based Learning , launched in 2016, published a series of research briefs around PBL in specific contexts. These briefs offer an introduction, overview of related research, and specific case studies of PBL within the particular discipline or context. The case studies offered in each brief can serve as springboards for instructors to think about their own courses, and will require adaptation to be most effective.

- PBL in the Social Sciences

- PBL in the Arts and Humanities

- PBL in Graduate Education

Additional References

Albert, T.C. (2019, May 22). Successful project-based learning . Harvard Business Publishing Education .

Albert, T.C. & Rennella M. (2021, November 11). Readying students for their careers through project-based learning . Harvard Business Publishing Education .

Boss, S. & Larmer, J. (2018). Project based teaching: How to create rigorous and engaging learning experiences . ASCD.

Center for Project-Based Learning. (2016). Center for project-based learning homepage . Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Heick, T. (n.d.). What are the greatest myths about project-based learning? . TeachThought.

High Quality Project Based Learning. (2018). A framework for high quality project based learning . HQPBL.

PBLWorks. (n.d.). Gold standard PBL: Project based teaching practices . PBLWorks.

PBLWorks (n.d.). What is project based learning? . PBLWorks.

TeachThought Staff. (n.d.). What is the difference between projects and PBL? . TeachThought.

Wobbe, K. K., & Stoddard, E. A. (2018). Project-Based Learning in the First Year : Beyond All Expectations . Stylus Publishing.

WPI Institute on Project-Based Learning. (n.d.). PBL in higher education . Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Project-Based Learning

This teaching guide explores the different types of project-based learning (PBL), its benefits, and tips for implementation in your classes.

Introduction

Project-based learning (PBL) involves students designing, developing, and constructing hands-on solutions to a problem. The educational value of PBL is that it aims to build students’ creative capacity to work through difficult or ill-structured problems, commonly in small teams. Typically, PBL takes students through the following phases or steps:

- Identifying a problem

- Agreeing on or devising a solution and potential solution path to the problem (i.e., how to achieve the solution)

- Designing and developing a prototype of the solution

- Refining the solution based on feedback from experts, instructors, and/or peers

Depending on the goals of the instructor, the size and scope of the project can vary greatly. Students may complete the four phases listed above over the course of many weeks, or even several times within a single class period.

Because of its focus on creativity and collaboration, PBL is enhanced when students experience opportunities to work across disciplines, employ technologies to make communication and product realization more efficient, or to design solutions to real-world problems posed by outside organizations or corporations. Projects do not need to be highly complex for students to benefit from PBL techniques. Often times, quick and simple projects are enough to provide students with valuable opportunities to make connections across content and practice.

Implementing project-based learning

As a pedagogical approach, PBL entails several key processes:

- Defining problems in terms of given constraints or challenges

- Generating multiple ideas to solve a given problem

- Prototyping — often in rapid iteration — potential solutions to a problem

- Testing the developed solution products or services in a “live” or authentic setting.

Defining the problem

PBL projects should start with students asking questions about a problem. What is the nature of problem they are trying to solve? What assumptions can they make about why the problem exists? Asking such questions will help students frame the problem in an appropriate context. If students are working on a real-world problem, it is important to consider how an end user will benefit from a solution.

Generating ideas

Next, students should be given the opportunity to brainstorm and discuss their ideas for solving the problem. The emphasis here is not to generate necessarily good ideas, but to generate many ideas. As such, brainstorming should encourage students to think wildly, but to stay focused on the problem. Setting guidelines for brainstorming sessions, such as giving everyone a chance to voice an idea, suspending judgement of others’ ideas, and building on the ideas of others will help make brainstorming a productive and generative exercise.

Prototyping solutions

Designing and prototyping a solution are typically the next phase of the PBL process. A prototype might take many forms: a mock-up, a storyboard, a role-play, or even an object made out of readily available materials such as pipe cleaners, popsicle sticks, and rubber bands. The purpose of prototyping is to expand upon the ideas generated during the brainstorming phase, and to quickly convey a how a solution to the problem might look and feel. Prototypes can often expose learners’ assumptions, as well as uncover unforeseen challenges that an end user of the solution might encounter. The focus on creating simple prototypes also means that students can iterate on their designs quickly and easily, incorporate feedback into their designs, and continually hone their problem solutions.

Students may then go about taking their prototypes to the next level of design: testing. Ideally, testing takes place in a “live” setting. Testing allows students to glean how well their products or services work in a real setting. The results of testing can provide students with important feedback on the their solutions, and generate new questions to consider. Did the solution work as planned? If not, what needs to be tweaked? In this way, testing engages students in critical thinking and reflection processes.

Unstructured versus structured projects

Research suggests that students learn more from working on unstructured or ill-structured projects than they do on highly structured ones. Unstructured projects are sometimes referred to as “open ended,” because they have no predictable or prescribed solution. In this way, open ended projects require students to consider assumptions and constraints, as well as to frame the problem they are trying to solve. Unstructured projects thus require students to do their own “structuring” of the problem at hand – a process that has been shown to enhance students’ abilities to transfer learning to other problem solving contexts.

Using Design Thinking in Higher Education (Educause)

Design Thinking and Innovation (GSM SI 839)

Project Based Learning through a Maker’s Lens (Edutopia)

You may also be interested in:

Case-based learning, game-based learning & gamification, creativity & innovation hub guide, udl learning community 2023, safety, curiosity, and the joy of learning, jump-starting discussion using images (part 2), student engagement part 2: ensuring deep learning, assessing learning.

Part 3: Instructional Methods/Learning Activities

Project-based learning.

- Project-based learning is a pedagogical strategy in which students produce a product related to a topic.

- The teacher sets the goals for the learner, and then allows the learner to explore the topic and create their project.

- The teacher is a facilitator in this student-centered approach and provides scaffolding and guidance when necessary.

- Proponents of project-based learning cite numerous benefits of these strategies including a greater depth of understanding of concepts, broader knowledge base, improved communication and interpersonal/social skills, enhanced leadership skills, increased creativity, and improved writing skills.

- When students use technology as a tool to communicate with others, they take on an active role vs. a passive role of transmitting the information by a teacher, a book, or broadcast. The student is constantly making choices on how to obtain, display, or manipulate information.

Project-based learning : Students independently gather resources and information to create a project and/or product.

Project-based learning, is a pedagogical method in which students are directed to create an artifact (or artifacts) to present their gained knowledge. Artifacts may include a variety of media such as writings, art, drawings, three-dimensional representations, videos, photography, or technology-based presentations. The basis of PBL lies in the authenticity or real-life application of the research and is considered an alternative to paper-based, rote memorization, teacher-led classrooms. Proponents of project-based learning cite numerous benefits to the implementation of these strategies in the classroom including a greater depth of understanding of concepts, broader knowledge base, improved communication and interpersonal/social skills, enhanced leadership skills, increased creativity, and improved writing skills.

John Dewey initially promoted the idea of “learning by doing. ” Educational research has advanced this idea of teaching and learning into a methodology known as “project-based learning. ” Blumenfeld & Krajcik (2006) cite studies by Marx et al., 2004, Rivet & Krajcki, 2004 and William & Linn, 2003 state that “research has demonstrated that students in project-based learning classrooms get higher scores than students in traditional classroom. ”

Project-based learning is not without its opponents, however; in Peer Evaluation in Blended Team Project-Based Learning: What Do Students Find Important? Hye-Jung & Cheolil (2012) describe social loafing as a negative aspect of collaborative learning. Social loafing may include insufficient performances by some team members as well as a lowering of expected standards of performance by the group as a whole to maintain congeniality amongst members. These authors said that because teachers tend to grade the finished product only, the social dynamics of the assignment may escape the teacher’s notice.

The core idea of project-based or inquiry based learning is that real-world problems capture students’ interest and provoke serious thinking as the students acquire and apply new knowledge in a problem-solving context. The teacher plays the role of facilitator, working with students to frame worthwhile questions, structuring meaningful tasks, coaching both knowledge development and social skills, and carefully assessing what students have learned from the experience. Typical projects present a problem to solve (What is the best way to reduce the pollution in the schoolyard pond? ) or a phenomenon to investigate (What causes rain? ).

At the high school level, classroom activities may include making water purification systems, investigating service learning, or creating new bus routes. At the middle school level, activities may include researching trash statistics, documenting local history through interviews, or writing essays about a community scavenger hunt. Classes are designed to help diverse students become college and career ready after high school.

When students use technology as a tool to communicate with others, they take on an active role vs. a passive role of transmitting the information by a teacher, a book, or broadcast. The student is constantly making choices on how to obtain, display, or manipulate information. Technology makes it possible for students to think actively about the choices they make and execute. Every student has the opportunity to get involved either individually or as a group.

Instructor role in Project Based Learning is that of a facilitator. They do not relinquish control of the collaborative classroom or student learning but rather develop an atmosphere of shared responsibility. The Instructor must structure the proposed question/issue so as to direct the student’s learning toward content-based materials. The instructor must regulate student success with intermittent, transitional goals to ensure student projects remain focused and students have a deep understanding of the concepts being investigated. The students are held accountable to these goals through ongoing feedback and assessments . The ongoing assessment and feedback are essential to ensure the student stays within the scope of the driving question and the core standards the project is trying to unpack. According to Andrew Miller of the Buck Institute of Education, formative assessments are used “in order to be transparent to parents and students, you need to be able to track and monitor ongoing formative assessments, that show work toward that standard. ” The instructor uses these assessments to guide the inquiry based learning process and ensure the students have learned the required content. Once the project is finished, the instructor evaluates the finished product and learning that it demonstrates

Students learn to work in a community, thereby taking on social responsibilities. The most significant contributions of PBL have been in schools languishing in poverty stricken areas; when students take responsibility, or ownership, for their learning, their self-esteem soars. It also helps to create better work habits and attitudes toward learning. Although students do work in groups, they also become more independent because they are receiving little instruction from the teacher. With Project-Based Learning students also learn skills that are essential in higher education. The students learn more than just finding answers, PBL allows them to expand their minds and think beyond what they normally would. Students have to find answers to questions and combine them using critically thinking skills to come up with answers.

Opponents of Project Based Learning warn against negative outcomes primarily in projects that become unfocused and tangential arguing that underdeveloped lessons can result in the wasting of precious class time. No one teaching method has been proven more effective than another. Opponents suggest that narratives and presentation of anecdotal evidence included in lecture-style instruction can convey the same knowledge in less class time. Given that disadvantaged students generally have fewer opportunities to learn academic content outside of school, wasted class time due to an unfocused lesson presents a particular problem. Instructors can be deluded into thinking that as long as a student is engaged and doing, they are learning. Ultimately it is cognitive activity that determines the success of a lesson. If the project does not remain on task and content driven the student will not be successful in learning the material. The lesson will be ineffective. A source of difficulty for teachers includes, “Keeping these complex projects on track while attending to students’ individual learning needs requires artful teaching, as well as industrial-strength project management. ” Like any approach, Project Based Learning is only beneficial when applied successfully.

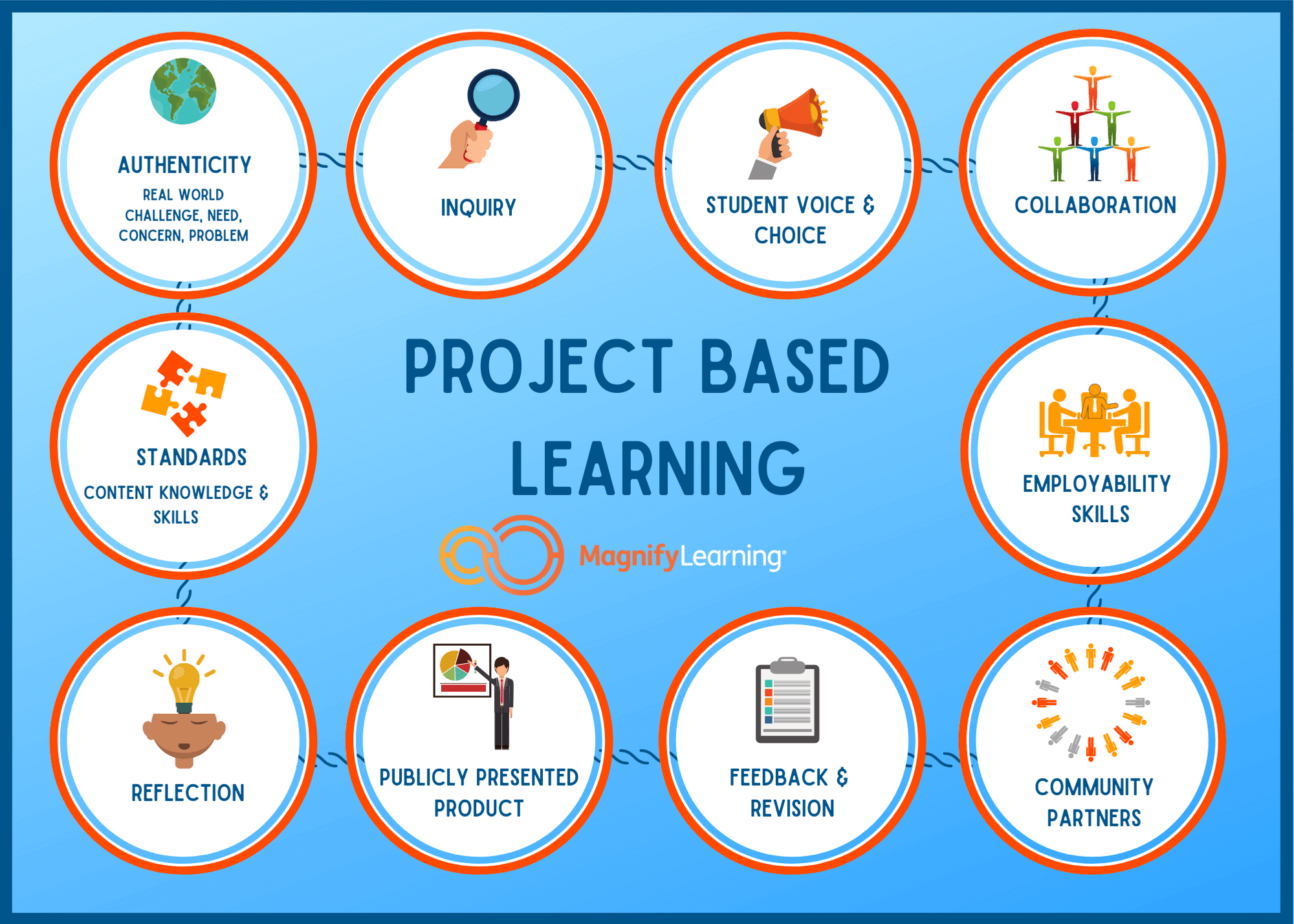

What is Project Based Learning?

Project Based Learning (PBL) is a model and framework of teaching and learning where students acquire content knowledge and skills in order to answer a driving question based on an authentic problem, need, challenge, or concern.

Project Based Learning is done collaboratively and within groups , using a variety of employability skills such as critical thinking, communication, and creativity.

PBL incorporates student voice and choice as well as inquiry .

Authentic PBL involves a community partner and a publicly presented end product .

Project Based Learning involves an ongoing process of feedback and revision as well as reflection .

PBL CORE COMPONENTS

Project based learning units include the following core components:.

Collaboration

Employability (21st Century) Skills

Community Partners

Feedback & Revision

Publicly Presented Product

Standards: Content Knowledge & Skills

Authenticity & Relevance: Addresses a real-world challenge, need, problem, or concern

Student Voice & Choice

The Core Components of PBL are the most essential pieces of every PBL Unit. For PBL fidelity, it is important to embed each of these components into the PBL design process… PBL CORE COMPONENTS CONTINUED .

7 steps to starting PBL

Want to begin your own pbl journey, download the 7 steps to starting pbl for free, 7 steps for starting pbl for teachers, 7 steps to starting pbl for administrators.

For more information about PBL check out:

Pbl design tools and resources.

- Differentiated Instruction: A Comprehensive Overview

- Summative Assessment Techniques: An Overview

- Differentiated Instruction for English Language Learners

- Inquiry-Based Learning: An Introduction to Teaching Strategies

- Classroom Management

- Behavior management techniques

- Classroom rules

- Classroom routines

- Classroom organization

- Assessment Strategies

- Summative assessment techniques

- Formative assessment techniques

- Portfolio assessment

- Performance-based assessment

- Teaching Strategies

- Active learning

- Inquiry-based learning

- Differentiated instruction

- Project-based learning

- o2c-library/governance/arc-organisation-reports/final%20report.pdf

- Learning Theories

- Behaviorism

- Social Learning Theory

- Cognitivism

- Constructivism

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Analysis skills

- Creative thinking skills

- Problem-solving skills

- Evaluation skills

- Metacognition

- Metacognitive strategies

- Self-reflection and metacognition

- Goal setting and metacognition

- Teaching Methods and Techniques

- Direct instruction methods

- Indirect instruction methods

- Lesson Planning Strategies

- Lesson sequencing strategies

- Unit planning strategies

- Differentiated Instruction Strategies

- Differentiated instruction for English language learners

- Differentiated instruction for gifted students

- Standards and Benchmarks

- State science standards and benchmarks

- National science standards and benchmarks

- Curriculum Design

- Course design and alignment

- Backward design principles

- Curriculum mapping

- Instructional Materials

- Textbooks and digital resources

- Instructional software and apps

- Engaging Activities and Games

- Hands-on activities and experiments

- Cooperative learning games

- Learning Environment Design

- Classroom technology integration

- Classroom layout and design

- Instructional Strategies

- Collaborative learning strategies

- Problem-based learning strategies

- 9-12 Science Lesson Plans

- Life science lesson plans for 9-12 learners

- Earth science lesson plans for 9-12 learners

- Physical science lesson plans for 9-12 learners

- K-5 Science Lesson Plans

- Earth science lesson plans for K-5 learners

- Life science lesson plans for K-5 learners

- Physical science lesson plans for K-5 learners

- 6-8 Science Lesson Plans

- Earth science lesson plans for 6-8 learners

- Life science lesson plans for 6-8 learners

- Physical science lesson plans for 6-8 learners

- Science Teaching

- Project-Based Learning: An In-Depth Look

Learn all about project-based learning, from its definition and history to its key benefits and how to use it in the classroom.

In recent years, project-based learning (PBL) has become an increasingly popular teaching approach at Saint Peters University Online and in classrooms around the world. This project-based teaching strategy is based on the belief that students learn best when they are actively engaged in the learning process and when they can apply their knowledge to solve real-world problems, such as project-based A level chemistry help or project-based a level maths solutions. While there have been numerous studies examining the efficacy of project-based learning, there is still much to learn about this teaching method, especially in terms of its implications for sociology at Saint Peter's University Online. University tutors at Saint Peter's University Online can play a key role in this process, providing invaluable guidance and support to students as they engage in project-based learning, helping them to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills, including those related to a level maths solutions. Additionally, private online tutors can be a great resource for those looking to study coding with a private online tutor .For those looking for the best online tutoring site to help with their project-based learning, university tutors can provide the best support and guidance. For those looking for the best online tutoring site to get help with project-based learning, university tutors can be a great resource. For those seeking the best online tutoring site for project-based learning, university tutors can provide invaluable assistance and support. For those looking for the best online tutoring site to help them with their project-based learning, university tutors can be an excellent resource. For those looking for more specialized tutoring, private online GCSE Physics tutoring can be a great resource for students who need extra help in their studies.

Additionally, for those looking to prepare for Oxbridge college tests, a comprehensive Oxbridge college test preparation guide can be a great resource. In this article, we will take an in-depth look at project-based learning and discuss the benefits it has to offer both students and educators from a sociological perspective. Additionally, this approach can be particularly beneficial for those preparing for entrance tests such as the Guide to Oxbridge entrance tests or for those enrolled in Saint Peter's University Online. It also encourages collaboration among students, fostering a sense of community and responsibility. Additionally, PBL can be adapted to fit different learning styles and needs, allowing for a more personalized approach to instruction. We will explore the history of project-based learning, the benefits it offers, and the strategies teachers can use to implement it in their classrooms. We will also examine some of the challenges associated with PBL and how to overcome them.

Project-Based Learning (PBL):

Definition:, key benefits:, challenges:, strategies for overcoming challenges:.

Creating a Successful Project-Based Learning Lesson Plan: To create a successful project-based learning lesson plan, teachers should start by defining the goals and objectives of the project. They should also decide on the type of project that best fits their class and develop a timeline for completing it. Teachers should also select materials and resources needed for the project, such as books, videos, or online resources. Additionally, they should provide clear instructions for each step of the project and assign roles to each student or group of students.

Types of Projects:

Challenges of project-based learning, lack of resources, student motivation, using technology for project-based learning.

This can help to foster collaboration and promote teamwork among students, allowing them to share ideas and get feedback from each other. Tools such as Google Docs, Trello, and Slack are all popular tools for collaborating on projects. Virtual reality can be used to create immersive experiences in the classroom. Students can explore virtual environments, observe and interact with objects, and learn about topics in a more engaging way.

For example, virtual field trips can be used to teach students about history, culture, or geography in an interactive way. Technology can also be used to facilitate research. Students can use the Internet to access a wealth of information, making it easier for them to find reliable sources and conduct research on any given topic. Search engines like Google are great tools for finding information quickly and efficiently.

In addition, technology can be used to provide feedback on student work. For example, teachers can use video or audio recordings of student presentations as a teaching tool, allowing them to see how students are performing and identify areas of improvement. By using technology in the classroom, teachers can create an engaging learning environment that is tailored to their students’ individual needs. Technology can help to improve the effectiveness of project-based learning by providing students with the tools and resources they need to succeed.

Benefits of Project-Based Learning

Improved critical thinking skills, collaboration skills, self-direction, what is project-based learning.

PBL has been used in classrooms for centuries, but its modern form began to emerge in the late 20th century as educators sought to develop more active learning strategies. Some of the earliest examples of PBL involved students being asked to build structures such as bridges or houses, or to design experiments or simulations in the sciences. At the heart of PBL are three key components: the challenge, the process, and the product. The challenge is the problem or question that the students must answer or solve.

The process involves the steps that students take to work through the challenge. This can include research, planning, designing, and creating. Finally, the product is the outcome of their work, which can range from a presentation or paper to a prototype or model. In order to be successful, PBL must include clear learning objectives and criteria for success, as well as meaningful tasks and activities that are relevant to the students’ lives.

Creating a Successful Project-Based Learning Lesson Plan

It is also important to ensure that the topic is age-appropriate and will not present any safety risks. Once a topic is selected, it is important to set clear goals for the lesson. Goals should be specific and measurable, such as “Students will be able to explain the process of photosynthesis by the end of the project.” This will help keep students on track as they work on their projects. After setting goals, teachers should create tasks that will help students reach those goals. Tasks should be broken down into manageable steps and can include activities like research, writing, or creating presentations.

Teachers should also provide resources and materials that students may need to complete the tasks. In addition to tasks, teachers should assign roles to each student. Roles could include things like research coordinator or group leader. Assigning roles helps foster teamwork and allows each student to contribute in different ways. Finally, it is important to provide feedback throughout the project. Feedback should be constructive and goal-oriented, focusing on what students did well and what they could improve on.

Types of Projects for Project-Based Learning

Research projects:, problem-solving projects:, artistic projects:, simulations:.

For example, a student studying the French Revolution could role-play as a member of the court during the Reign of Terror. Simulations help students gain a better understanding of how certain events unfolded and why they happened. Project-based learning is a teaching method that encourages students to explore and understand a subject in depth. It offers a variety of benefits, including enhanced engagement and critical thinking, as well as increased collaboration and problem solving . Additionally, it enables teachers to design creative, engaging projects that can be tailored to the needs and interests of their students.

However, it is important to consider the challenges of project-based learning, such as lack of structure and organization, and plan accordingly. By creating a successful project-based learning lesson plan, incorporating technology when appropriate, and selecting the right type of project for the lesson, teachers can help ensure that their students have a successful experience. For more information on project-based learning, there are many online resources available.

- collaboration

Shahid Lakha

Shahid Lakha is a seasoned educational consultant with a rich history in the independent education sector and EdTech. With a solid background in Physics, Shahid has cultivated a career that spans tutoring, consulting, and entrepreneurship. As an Educational Consultant at Spires Online Tutoring since October 2016, he has been instrumental in fostering educational excellence in the online tutoring space. Shahid is also the founder and director of Specialist Science Tutors, a tutoring agency based in West London, where he has successfully managed various facets of the business, including marketing, web design, and client relationships. His dedication to education is further evidenced by his role as a self-employed tutor, where he has been teaching Maths, Physics, and Engineering to students up to university level since September 2011. Shahid holds a Master of Science in Photon Science from the University of Manchester and a Bachelor of Science in Physics from the University of Bath.

New Articles

- Integrating Technology into the Classroom

This article provides an overview of classroom technology integration and how it can improve learning experiences in the classroom.

- Understanding Curriculum Mapping