40 Best Essays of All Time (Including Links & Writing Tips)

I wanted to improve my writing skills. I thought that reading the forty best essays of all time would bring me closer to my goal.

I had little money (buying forty collections of essays was out of the question) so I’ve found them online instead. I’ve hacked through piles of them, and finally, I’ve found the great ones. Now I want to share the whole list with you (with the addition of my notes about writing). Each item on the list has a direct link to the essay, so please click away and indulge yourself. Also, next to each essay, there’s an image of the book that contains the original work.

About this essay list:

Reading essays is like indulging in candy; once you start, it’s hard to stop. I sought out essays that were not only well-crafted but also impactful. These pieces genuinely shifted my perspective. Whether you’re diving in for enjoyment or to hone your writing, these essays promise to leave an imprint. It’s fascinating how an essay can resonate with you, and even if details fade, its essence remains. I haven’t ranked them in any way; they’re all stellar. Skim through, explore the summaries, and pick up some writing tips along the way. For more essay gems, consider “Best American Essays” by Joyce Carol Oates or “101 Essays That Will Change The Way You Think” curated by Brianna Wiest.

40 Best Essays of All Time (With Links And Writing Tips)

1. david sedaris – laugh, kookaburra.

A great family drama takes place against the backdrop of the Australian wilderness. And the Kookaburra laughs… This is one of the top essays of the lot. It’s a great mixture of family reminiscences, travel writing, and advice on what’s most important in life. You’ll also learn an awful lot about the curious culture of the Aussies.

Writing tips from the essay:

- Use analogies (you can make it funny or dramatic to achieve a better effect): “Don’t be afraid,” the waiter said, and he talked to the kookaburra in a soothing, respectful voice, the way you might to a child with a switchblade in his hand”.

- You can touch a few cognate stories in one piece of writing . Reveal the layers gradually. Intertwine them and arrange for a grand finale where everything is finally clear.

- Be on the side of the reader. Become their friend and tell the story naturally, like around the dinner table.

- Use short, punchy sentences. Tell only as much as is required to make your point vivid.

- Conjure sentences that create actual feelings: “I had on a sweater and a jacket, but they weren’t quite enough, and I shivered as we walked toward the body, and saw that it was a . . . what, exactly?”

- You may ask a few tough questions in a row to provoke interest and let the reader think.

2. Charles D’Ambrosio – Documents

Do you think your life punches you in the face all too often? After reading this essay, you will change your mind. Reading about loss and hardships often makes us sad at first, but then enables us to feel grateful for our lives . D’Ambrosio shares his documents (poems, letters) that had a major impact on his life, and brilliantly shows how not to let go of the past.

- The most powerful stories are about your family and the childhood moments that shaped your life.

- You don’t need to build up tension and pussyfoot around the crux of the matter. Instead, surprise the reader by telling it like it is: “The poem was an allegory about his desire to leave our family.” Or: “My father had three sons. I’m the eldest; Danny, the youngest, killed himself sixteen years ago”.

- You can use real documents and quotes from your family and friends. It makes it so much more personal and relatable.

- Don’t cringe before the long sentence if you know it’s a strong one.

- At the end of the essay, you may come back to the first theme to close the circuit.

- Using slightly poetic language is acceptable, as long as it improves the story.

3. E. B. White – Once more to the lake

What does it mean to be a father? Can you see your younger self, reflected in your child? This beautiful essay tells the story of the author, his son, and their traditional stay at a placid lake hidden within the forests of Maine. This place of nature is filled with sunshine and childhood memories. It also provides for one of the greatest meditations on nature and the passing of time.

- Use sophisticated language, but not at the expense of readability.

- Use vivid language to trigger the mirror neurons in the reader’s brain: “I took along my son, who had never had any fresh water up his nose and who had seen lily pads only from train windows”.

- It’s important to mention universal feelings that are rarely talked about (it helps to create a bond between two minds): “You remember one thing, and that suddenly reminds you of another thing. I guess I remembered clearest of all the early mornings when the lake was cool and motionless”.

- Animate the inanimate: “this constant and trustworthy body of water”.

- Mentioning tales of yore is a good way to add some mystery and timelessness to your piece.

- Using double, or even triple “and” in one sentence is fine. It can make the sentence sing.

4. Zadie Smith – Fail Better

Aspiring writers feel tremendous pressure to perform. The daily quota of words often turns out to be nothing more than gibberish. What then? Also, should the writer please the reader or should she be fully independent? What does it mean to be a writer, anyway? This essay is an attempt to answer these questions, but its contents are not only meant for scribblers. Within it, you’ll find some great notes about literary criticism, how we treat art , and the responsibility of the reader.

- A perfect novel ? There’s no such thing.

- The novel always reflects the inner world of the writer. That’s why we’re fascinated with writers.

- Writing is not simply about craftsmanship, but about taking your reader to the unknown lands. In the words of Christopher Hitchens: “Your ideal authors ought to pull you from the foundering of your previous existence, not smilingly guide you into a friendly and peaceable harbor.”

- Style comes from your unique personality and the perception of the world. It takes time to develop it.

- Never try to tell it all. “All” can never be put into language. Take a part of it and tell it the best you can.

- Avoid being cliché. Try to infuse new life into your writing .

- Writing is about your way of being. It’s your game. Paradoxically, if you try to please everyone, your writing will become less appealing. You’ll lose the interest of the readers. This rule doesn’t apply in the business world where you have to write for a specific person (a target audience).

- As a reader, you have responsibilities too. According to the critics, every thirty years, there’s just a handful of great novels. Maybe it’s true. But there’s also an element of personal connection between the reader and the writer. That’s why for one person a novel is a marvel, while for the other, nothing special at all. That’s why you have to search and find the author who will touch you.

5. Virginia Woolf – Death of the Moth

Amid an ordinary day, sitting in a room of her own, Virginia Woolf tells about the epic struggle for survival and the evanescence of life. This short essay is truly powerful. In the beginning, the atmosphere is happy. Life is in full force. And then, suddenly, it fades away. This sense of melancholy would mark the last years of Woolf’s life.

- The melody of language… A good sentence is like music: “Moths that fly by day are not properly to be called moths; they do not excite that pleasant sense of dark autumn nights and ivy-blossom which the commonest yellow- underwing asleep in the shadow of the curtain never fails to rouse in us”.

- You can show the grandest in the mundane (for example, the moth at your window and the drama of life and death).

- Using simple comparisons makes the style more lucid: “Being intent on other matters I watched these futile attempts for a time without thinking, unconsciously waiting for him to resume his flight, as one waits for a machine, that has stopped momentarily, to start again without considering the reason of its failure”.

6. Meghan Daum – My Misspent Youth

Many of us, at some point or another, dream about living in New York. Meghan Daum’s take on the subject differs slightly from what you might expect. There’s no glamour, no Broadway shows, and no fancy restaurants. Instead, there’s the sullen reality of living in one of the most expensive cities in the world. You’ll get all the juicy details about credit cards, overdue payments, and scrambling for survival. It’s a word of warning. But it’s also a great story about shattered fantasies of living in a big city. Word on the street is: “You ain’t promised mañana in the rotten manzana.”

- You can paint a picture of your former self. What did that person believe in? What kind of world did he or she live in?

- “The day that turned your life around” is a good theme you may use in a story. Memories of a special day are filled with emotions. Strong emotions often breed strong writing.

- Use cultural references and relevant slang to create a context for your story.

- You can tell all the details of the story, even if in some people’s eyes you’ll look like the dumbest motherfucker that ever lived. It adds to the originality.

- Say it in a new way: “In this mindset, the dollars spent, like the mechanics of a machine no one bothers to understand, become an abstraction, an intangible avenue toward self-expression, a mere vehicle of style”.

- You can mix your personal story with the zeitgeist or the ethos of the time.

7. Roger Ebert – Go Gentle Into That Good Night

Probably the greatest film critic of all time, Roger Ebert, tells us not to rage against the dying of the light. This essay is full of courage, erudition, and humanism. From it, we learn about what it means to be dying (Hitchens’ “Mortality” is another great work on that theme). But there’s so much more. It’s a great celebration of life too. It’s about not giving up, and sticking to your principles until the very end. It brings to mind the famous scene from Dead Poets Society where John Keating (Robin Williams) tells his students: “Carpe, carpe diem, seize the day boys, make your lives extraordinary”.

- Start with a powerful sentence: “I know it is coming, and I do not fear it, because I believe there is nothing on the other side of death to fear.”

- Use quotes to prove your point -”‘Ask someone how they feel about death’, he said, ‘and they’ll tell you everyone’s gonna die’. Ask them, ‘In the next 30 seconds?’ No, no, no, that’s not gonna happen”.

- Admit the basic truths about reality in a childlike way (especially after pondering quantum physics) – “I believe my wristwatch exists, and even when I am unconscious, it is ticking all the same. You have to start somewhere”.

- Let other thinkers prove your point. Use quotes and ideas from your favorite authors and friends.

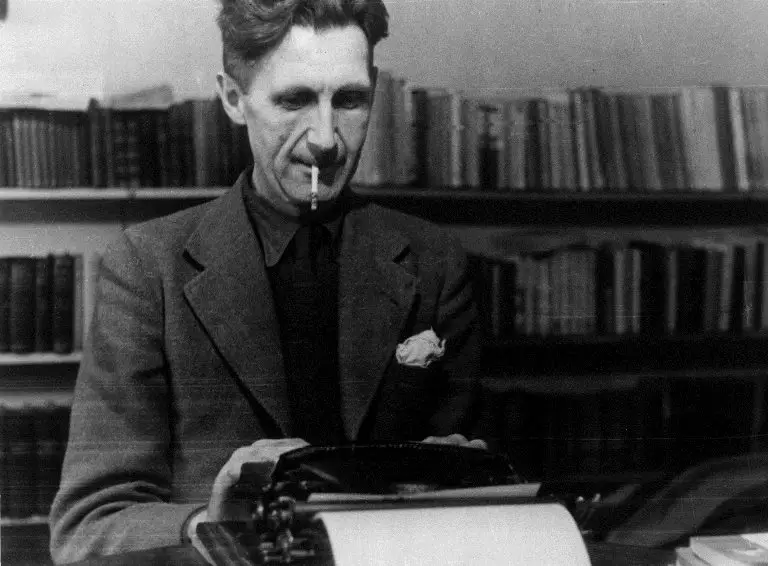

8. George Orwell – Shooting an Elephant

Even after one reading, you’ll remember this one for years. The story, set in British Burma, is about shooting an elephant (it’s not for the squeamish). It’s also the most powerful denunciation of colonialism ever put into writing. Orwell, apparently a free representative of British rule, feels to be nothing more than a puppet succumbing to the whim of the mob.

- The first sentence is the most important one: “In Moulmein, in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people — the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me”.

- You can use just the first paragraph to set the stage for the whole piece of prose.

- Use beautiful language that stirs the imagination: “I remember that it was a cloudy, stuffy morning at the beginning of the rains.” Or: “I watched him beating his bunch of grass against his knees, with that preoccupied grandmotherly air that elephants have.”

- If you’ve ever been to war, you will have a story to tell: “(Never tell me, by the way, that the dead look peaceful. Most of the corpses I have seen looked devilish.)”

- Use simple words, and admit the sad truth only you can perceive: “They did not like me, but with the magical rifle in my hands I was momentarily worth watching”.

- Share words of wisdom to add texture to the writing: “I perceived at this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his freedom that he destroys.”

- I highly recommend reading everything written by Orwell, especially if you’re looking for the best essay collections on Amazon or Goodreads.

9. George Orwell – A Hanging

It’s just another day in Burma – time to hang a man. Without much ado, Orwell recounts the grim reality of taking another person’s life. A man is taken from his cage and in a few minutes, he’s going to be hanged. The most horrible thing is the normality of it. It’s a powerful story about human nature. Also, there’s an extraordinary incident with the dog, but I won’t get ahead of myself.

- Create brilliant, yet short descriptions of characters: “He was a Hindu, a puny wisp of a man, with a shaven head and vague liquid eyes. He had a thick, sprouting mustache, absurdly too big for his body, rather like the mustache of a comic man on the films”.

- Understand and share the felt presence of a unique experience: “It is curious, but till that moment I had never realized what it means to destroy a healthy, conscious man”.

- Make your readers hear the sound that will stay with them forever: “And then when the noose was fixed, the prisoner began crying out on his god. It was a high, reiterated cry of “Ram! Ram! Ram! Ram!”

- Make the ending original by refusing the tendency to seek closure or summing it up.

10. Christopher Hitchens – Assassins of The Mind

In one of the greatest essays written in defense of free speech, Christopher Hitchens shares many examples of how modern media kneel to the explicit threats of violence posed by Islamic extremists. He recounts the story of his friend, Salman Rushdie, author of Satanic Verses who, for many years, had to watch over his shoulder because of the fatwa of Ayatollah Khomeini. With his usual wit, Hitchens shares various examples of people who died because of their opinions and of editors who refuse to publish anything related to Islam because of fear (and it was written long before the Charlie Hebdo massacre). After reading the essay, you realize that freedom of expression is one of the most precious things we have and that we have to fight for it. I highly recommend all essay collections penned by Hitchens, especially the ones written for Vanity Fair.

- Assume that the readers will know the cultural references. When they do, their self-esteem goes up – they are a part of an insider group.

- When proving your point, give a variety of real-life examples from eclectic sources. Leave no room for ambiguity or vagueness. Research and overall knowledge are essential here.

- Use italics to emphasize a specific word or phrase (here I use the underlining): “We live now in a climate where every publisher and editor and politician has to weigh in advance the possibility of violent Muslim reprisal. In consequence, several things have not happened.”

- Think about how to make it sound more original: “So there is now a hidden partner in our cultural and academic and publishing and the broadcasting world: a shadowy figure that has, uninvited, drawn up a chair to the table.”

11. Christopher Hitchens – The New Commandments

It’s high time to shatter the tablets and amend the biblical rules of conduct. Watch, as Christopher Hitchens slays one commandment after the other on moral, as well as historical grounds. For example, did you know that there are many versions of the divine law dictated by God to Moses which you can find in the Bible? Aren’t we thus empowered to write our version of a proper moral code? If you approach it with an open mind, this essay may change the way you think about the Bible and religion.

- Take the iconoclastic approach. Have a party on the hallowed soil.

- Use humor to undermine orthodox ideas (it seems to be the best way to deal with an established authority).

- Use sarcasm and irony when appropriate (or not): “Nobody is opposed to a day of rest. The international Communist movement got its start by proclaiming a strike for an eight-hour day on May 1, 1886, against Christian employers who used child labor seven days a week”.

- Defeat God on legal grounds: “Wise lawmakers know that it is a mistake to promulgate legislation that is impossible to obey”.

- Be ruthless in the logic of your argument. Provide evidence.

12. Phillip Lopate – Against Joie de Vivre

While reading this fantastic essay, this quote from Slavoj Žižek kept coming back to me: “I think that the only life of deep satisfaction is a life of eternal struggle, especially struggle with oneself. If you want to remain happy, just remain stupid. Authentic masters are never happy; happiness is a category of slaves”. I can bear the onus of happiness or joie de vivre for some time. But this force enables me to get free and wallow in the sweet feelings of melancholy and nostalgia. By reading this work of Lopate, you’ll enter into the world of an intelligent man who finds most social rituals a drag. It’s worth exploring.

- Go against the grain. Be flamboyant and controversial (if you can handle it).

- Treat the paragraph like a group of thoughts on one theme. Next paragraph, next theme.

- Use references to other artists to set the context and enrich the prose: “These sunny little canvases with their talented innocence, the third-generation spirit of Montmartre, bore testimony to a love of life so unbending as to leave an impression of rigid narrow-mindedness as extreme as any Savonarola. Their rejection of sorrow was total”.

- Capture the emotions in life that are universal, yet remain unspoken.

- Don’t be afraid to share your intimate experiences.

13. Philip Larkin – The Pleasure Principle

This piece comes from the Required Writing collection of personal essays. Larkin argues that reading in verse should be a source of intimate pleasure – not a medley of unintelligible thoughts that only the author can (or can’t?) decipher. It’s a sobering take on modern poetry and a great call to action for all those involved in it. Well worth a read.

- Write about complicated ideas (such as poetry) simply. You can change how people look at things if you express yourself enough.

- Go boldly. The reader wants a bold writer: “We seem to be producing a new kind of bad poetry, not the old kind that tries to move the reader and fails, but one that does not even try”.

- Play with words and sentence length. Create music: “It is time some of you playboys realized, says the judge, that reading a poem is hard work. Fourteen days in stir. Next case”.

- Persuade the reader to take action. Here, direct language is the most effective.

14. Sigmund Freud – Thoughts for the Times on War and Death

This essay reveals Freud’s disillusionment with the whole project of Western civilization. How the peaceful European countries could engage in a war that would eventually cost over 17 million lives? What stirs people to kill each other? Is it their nature, or are they puppets of imperial forces with agendas of their own? From the perspective of time, this work by Freud doesn’t seem to be fully accurate. Even so, it’s well worth your time.

- Commence with long words derived from Latin. Get grandiloquent, make your argument incontrovertible, and leave your audience discombobulated.

- Use unending sentences, so that the reader feels confused, yet impressed.

- Say it well: “In this way, he enjoyed the blue sea and the grey; the beauty of snow-covered mountains and green meadowlands; the magic of northern forests and the splendor of southern vegetation; the mood evoked by landscapes that recall great historical events, and the silence of untouched nature”.

- Human nature is a subject that never gets dry.

15. Zadie Smith – Some Notes on Attunement

“You are privy to a great becoming, but you recognize nothing” – Francis Dolarhyde. This one is about the elusiveness of change occurring within you. For Zadie, it was hard to attune to the vibes of Joni Mitchell – especially her Blue album. But eventually, she grew up to appreciate her genius, and all the other things changed as well. This top essay is all about the relationship between humans, and art. We shouldn’t like art because we’re supposed to. We should like it because it has an instantaneous, emotional effect on us. Although, according to Stansfield (Gary Oldman) in Léon, liking Beethoven is rather mandatory.

- Build an expectation of what’s coming: “The first time I heard her I didn’t hear her at all”.

- Don’t be afraid of repetition if it feels good.

- Psychedelic drugs let you appreciate things you never appreciated.

- Intertwine a personal journey with philosophical musings.

- Show rather than tell: “My friends pitied their eyes. The same look the faithful give you as you hand them back their “literature” and close the door in their faces”.

- Let the poets speak for you: “That time is past, / And all its aching joys are now no

- more, / And all its dizzy raptures”.

- By voicing your anxieties, you can heal the anxieties of the reader. In that way, you say: “I’m just like you. I’m your friend in this struggle”.

- Admit your flaws to make your persona more relatable.

16. Annie Dillard – Total Eclipse

My imagination was always stirred by the scene of the solar eclipse in Pharaoh, by Boleslaw Prus. I wondered about the shock of the disoriented crowd when they saw how their ruler could switch off the light. Getting immersed in this essay by Annie Dillard has a similar effect. It produces amazement and some kind of primeval fear. It’s not only the environment that changes; it’s your mind and the perception of the world. After the eclipse, nothing is going to be the same again.

- Yet again, the power of the first sentence draws you in: “It had been like dying, that sliding down the mountain pass”.

- Don’t miss the extraordinary scene. Then describe it: “Up in the sky, like a crater from some distant cataclysm, was a hollow ring”.

- Use colloquial language. Write as you talk. Short sentences often win.

- Contrast the numinous with the mundane to enthrall the reader.

17. Édouard Levé – When I Look at a Strawberry, I Think of a Tongue

This suicidally beautiful essay will teach you a lot about the appreciation of life and the struggle with mental illness. It’s a collection of personal, apparently unrelated thoughts that show us the rich interior of the author. You look at the real-time thoughts of another person, and then recognize the same patterns within yourself… It sounds like a confession of a person who’s about to take their life, and it’s striking in its originality.

- Use the stream-of-consciousness technique and put random thoughts on paper. Then, polish them: “I have attempted suicide once, I’ve been tempted four times to attempt it”.

- Place the treasure deep within the story: “When I look at a strawberry, I think of a tongue, when I lick one, of a kiss”.

- Don’t worry about what people might think. The more you expose, the more powerful the writing. Readers also take part in the great drama. They experience universal emotions that mostly stay inside. You can translate them into writing.

18. Gloria E. Anzaldúa – How to Tame a Wild Tongue

Anzaldúa, who was born in south Texas, had to struggle to find her true identity. She was American, but her culture was grounded in Mexico. In this way, she and her people were not fully respected in either of the countries. This essay is an account of her journey of becoming the ambassador of the Chicano (Mexican-American) culture. It’s full of anecdotes, interesting references, and different shades of Spanish. It’s a window into a new cultural dimension that you’ve never experienced before.

- If your mother tongue is not English, but you write in English, use some of your unique homeland vocabulary.

- You come from a rich cultural heritage. You can share it with people who never heard about it, and are not even looking for it, but it is of immense value to them when they discover it.

- Never forget about your identity. It is precious. It is a part of who you are. Even if you migrate, try to preserve it. Use it to your best advantage and become the voice of other people in the same situation.

- Tell them what’s really on your mind: “So if you want to hurt me, talk badly about my language. Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity – I am my language”.

19. Kurt Vonnegut – Dispatch From A Man Without a Country

In terms of style, this essay is flawless. It’s simple, conversational, humorous, and yet, full of wisdom. And when Vonnegut becomes a teacher and draws an axis of “beginning – end”, and, “good fortune – bad fortune” to explain literature, it becomes outright hilarious. It’s hard to find an author with such a down-to-earth approach. He doesn’t need to get intellectual to prove a point. And the point could be summed up by the quote from Great Expectations – “On the Rampage, Pip, and off the Rampage, Pip – such is Life!”

- Start with a curious question: “Do you know what a twerp is?”

- Surprise your readers with uncanny analogies: “I am from a family of artists. Here I am, making a living in the arts. It has not been a rebellion. It’s as though I had taken over the family Esso station.”

- Use your natural language without too many special effects. In time, the style will crystalize.

- An amusing lesson in writing from Mr. Vonnegut: “Here is a lesson in creative writing. First rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you’ve been to college”.

- You can put actual images or vignettes between the paragraphs to illustrate something.

20. Mary Ruefle – On Fear

Most psychologists and gurus agree that fear is the greatest enemy of success or any creative activity. It’s programmed into our minds to keep us away from imaginary harm. Mary Ruefle takes on this basic human emotion with flair. She explores fear from so many angles (especially in the world of poetry-writing) that at the end of this personal essay, you will look at it, dissect it, untangle it, and hopefully be able to say “f**k you” the next time your brain is trying to stop you.

- Research your subject thoroughly. Ask people, have interviews, get expert opinions, and gather as much information as possible. Then scavenge through the fields of data, and pull out the golden bits that will let your prose shine.

- Use powerful quotes to add color to your story: “The poet who embarks on the creation of the poem (as I know by experience), begins with the aimless sensation of a hunter about to embark on a night hunt through the remotest of forests. Unaccountable dread stirs in his heart”. – Lorca.

- Writing advice from the essay: “One of the fears a young writer has is not being able to write as well as he or she wants to, the fear of not being able to sound like X or Y, a favorite author. But out of fear, hopefully, is born a young writer’s voice”.

21. Susan Sontag – Against Interpretation

In this highly intellectual essay, Sontag fights for art and its interpretation. It’s a great lesson, especially for critics and interpreters who endlessly chew on works that simply defy interpretation. Why don’t we just leave the art alone? I always hated it when at school they asked me: “What did the author have in mind when he did X or Y?” Iēsous Pantocrator! Hell if I know! I will judge it through my subjective experience!

- Leave the art alone: “Today is such a time, when the project of interpretation is reactionary, stifling. Like the fumes of the automobile and heavy industry which befoul the urban atmosphere, the effusion of interpretations of art today poisons our sensibilities”.

- When you have something really important to say, style matters less.

- There’s no use in creating a second meaning or inviting interpretation of our art. Just leave it be and let it speak for itself.

22. Nora Ephron – A Few Words About Breasts

This is a heartwarming, coming-of-age story about a young girl who waits in vain for her breasts to grow. It’s simply a humorous and pleasurable read. The size of breasts is a big deal for women. If you’re a man, you may peek into the mind of a woman and learn many interesting things. If you’re a woman, maybe you’ll be able to relate and at last, be at peace with your bosom.

- Touch an interesting subject and establish a strong connection with the readers (in that case, women with small breasts). Let your personality shine through the written piece. If you are lighthearted, show it.

- Use hyphens to create an impression of real talk: “My house was full of apples and peaches and milk and homemade chocolate chip cookies – which were nice, and good for you, but-not-right-before-dinner-or-you’ll-spoil-your-appetite.”

- Use present tense when you tell a story to add more life to it.

- Share the pronounced, memorable traits of characters: “A previous girlfriend named Solange, who was famous throughout Beverly Hills High School for having no pigment in her right eyebrow, had knitted them for him (angora dice)”.

23. Carl Sagan – Does Truth Matter – Science, Pseudoscience, and Civilization

Carl Sagan was one of the greatest proponents of skepticism, and an author of numerous books, including one of my all-time favorites – The Demon-Haunted World . He was also a renowned physicist and the host of the fantastic Cosmos: A Personal Voyage series, which inspired a whole generation to uncover the mysteries of the cosmos. He was also a dedicated weed smoker – clearly ahead of his time. The essay that you’re about to read is a crystallization of his views about true science, and why you should check the evidence before believing in UFOs or similar sorts of crap.

- Tell people the brutal truth they need to hear. Be the one who spells it out for them.

- Give a multitude of examples to prove your point. Giving hard facts helps to establish trust with the readers and show the veracity of your arguments.

- Recommend a good book that will change your reader’s minds – How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life

24. Paul Graham – How To Do What You Love

How To Do What You Love should be read by every college student and young adult. The Internet is flooded with a large number of articles and videos that are supposed to tell you what to do with your life. Most of them are worthless, but this one is different. It’s sincere, and there’s no hidden agenda behind it. There’s so much we take for granted – what we study, where we work, what we do in our free time… Surely we have another two hundred years to figure it out, right? Life’s too short to be so naïve. Please, read the essay and let it help you gain fulfillment from your work.

- Ask simple, yet thought-provoking questions (especially at the beginning of the paragraph) to engage the reader: “How much are you supposed to like what you do?”

- Let the readers question their basic assumptions: “Prestige is like a powerful magnet that warps even your beliefs about what you enjoy. It causes you to work not on what you like, but what you’d like to like”.

- If you’re writing for a younger audience, you can act as a mentor. It’s beneficial for younger people to read a few words of advice from a person with experience.

25. John Jeremiah Sullivan – Mister Lytle

A young, aspiring writer is about to become a nurse of a fading writer – Mister Lytle (Andrew Nelson Lytle), and there will be trouble. This essay by Sullivan is probably my favorite one from the whole list. The amount of beautiful sentences it contains is just overwhelming. But that’s just a part of its charm. It also takes you to the Old South which has an incredible atmosphere. It’s grim and tawny but you want to stay there for a while.

- Short, distinct sentences are often the most powerful ones: “He had a deathbed, in other words. He didn’t go suddenly”.

- Stay consistent with the mood of the story. When reading Mister Lytle you are immersed in that southern, forsaken, gloomy world, and it’s a pleasure.

- The spectacular language that captures it all: “His French was superb, but his accent in English was best—that extinct mid-Southern, land-grant pioneer speech, with its tinges of the abandoned Celtic urban Northeast (“boned” for burned) and its raw gentility”.

- This essay is just too good. You have to read it.

26. Joan Didion – On Self Respect

Normally, with that title, you would expect some straightforward advice about how to improve your character and get on with your goddamn life – but not from Joan Didion. From the very beginning, you can feel the depth of her thinking, and the unmistakable style of a true woman who’s been hurt. You can learn more from this essay than from whole books about self-improvement . It reminds me of the scene from True Detective, where Frank Semyon tells Ray Velcoro to “own it” after he realizes he killed the wrong man all these years ago. I guess we all have to “own it”, recognize our mistakes, and move forward sometimes.

- Share your moral advice: “Character — the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life — is the source from which self-respect springs”.

- It’s worth exploring the subject further from a different angle. It doesn’t matter how many people have already written on self-respect or self-reliance – you can still write passionately about it.

- Whatever happens, you must take responsibility for it. Brave the storms of discontent.

27. Susan Sontag – Notes on Camp

I’ve never read anything so thorough and lucid about an artistic current. After reading this essay, you will know what camp is. But not only that – you will learn about so many artists you’ve never heard of. You will follow their traces and go to places where you’ve never been before. You will vastly increase your appreciation of art. It’s interesting how something written as a list could be so amazing. All the listicles we usually see on the web simply cannot compare with it.

- Talking about artistic sensibilities is a tough job. When you read the essay, you will see how much research, thought and raw intellect came into it. But that’s one of the reasons why people still read it today, even though it was written in 1964.

- You can choose an unorthodox way of expression in the medium for which you produce. For example, Notes on Camp is a listicle – one of the most popular content formats on the web. But in the olden days, it was uncommon to see it in print form.

- Just think about what is camp: “And third among the great creative sensibilities is Camp: the sensibility of failed seriousness, of the theatricalization of experience. Camp refuses both the harmonies of traditional seriousness and the risks of fully identifying with extreme states of feeling”.

28. Ralph Waldo Emerson – Self-Reliance

That’s the oldest one from the lot. Written in 1841, it still inspires generations of people. It will let you understand what it means to be self-made. It contains some of the most memorable quotes of all time. I don’t know why, but this one especially touched me: “Every true man is a cause, a country, and an age; requires infinite spaces and numbers and time fully to accomplish his design, and posterity seems to follow his steps as a train of clients”. Now isn’t it purely individualistic, American thought? Emerson told me (and he will tell you) to do something amazing with my life. The language it contains is a bit archaic, but that just adds to the weight of the argument. You can consider it to be a meeting with a great philosopher who shaped the ethos of the modern United States.

- You can start with a powerful poem that will set the stage for your work.

- Be free in your creative flow. Do not wait for the approval of others: “What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think. This rule, equally arduous in actual and in intellectual life, may serve for the whole distinction between greatness and meanness”.

- Use rhetorical questions to strengthen your argument: “I hear a preacher announce for his text and topic the expediency of one of the institutions of his church. Do I not know beforehand that not possibly say a new and spontaneous word?”

29. David Foster Wallace – Consider The Lobster

When you want simple field notes about a food festival, you needn’t send there the formidable David Foster Wallace. He sees right through the hypocrisy and cruelty behind killing hundreds of thousands of innocent lobsters – by boiling them alive. This essay uncovers some of the worst traits of modern American people. There are no apologies or hedging one’s bets. There’s just plain truth that stabs you in the eye like a lobster claw. After reading this essay, you may reconsider the whole animal-eating business.

- When it’s important, say it plainly and stagger the reader: “[Lobsters] survive right up until they’re boiled. Most of us have been in supermarkets or restaurants that feature tanks of live lobster, from which you can pick out your supper while it watches you point”.

- In your writing, put exact quotes of the people you’ve been interviewing (including slang and grammatical errors). It makes it more vivid, and interesting.

- You can use humor in serious situations to make your story grotesque.

- Use captions to expound on interesting points of your essay.

30. David Foster Wallace – The Nature of the Fun

The famous novelist and author of the most powerful commencement speech ever done is going to tell you about the joys and sorrows of writing a work of fiction. It’s like taking care of a mutant child that constantly oozes smelly liquids. But you love that child and you want others to love it too. It’s a very humorous account of what it means to be an author. If you ever plan to write a novel, you should read that one. And the story about the Chinese farmer is just priceless.

- Base your point on a chimerical analogy. Here, the writer’s unfinished work is a “hideously damaged infant”.

- Even in expository writing, you may share an interesting story to keep things lively.

- Share your true emotions (even when you think they won’t interest anyone). Often, that’s exactly what will interest the reader.

- Read the whole essay for marvelous advice on writing fiction.

31. Margaret Atwood – Attitude

This is not an essay per se, but I included it on the list for the sake of variety. It was delivered as a commencement speech at The University of Toronto, and it’s about keeping the right attitude. Soon after leaving university, most graduates have to forget about safety, parties, and travel and start a new life – one filled with a painful routine that will last until they drop. Atwood says that you don’t have to accept that. You can choose how you react to everything that happens to you (and you don’t have to stay in that dead-end job for the rest of your days).

- At times, we are all too eager to persuade, but the strongest persuasion is not forceful. It’s subtle. It speaks to the heart. It affects you gradually.

- You may be tempted to talk about a subject by first stating what it is not, rather than what it is. Try to avoid that.

- Simple advice for writers (and life in general): “When faced with the inevitable, you always have a choice. You may not be able to alter reality, but you can alter your attitude towards it”.

32. Jo Ann Beard – The Fourth State of Matter

Read that one as soon as possible. It’s one of the most masterful and impactful essays you’ll ever read. It’s like a good horror – a slow build-up, and then your jaw drops to the ground. To summarize the story would be to spoil it, so I recommend that you just dig in and devour this essay in one sitting. It’s a perfect example of “show, don’t tell” writing, where the actions of characters are enough to create the right effect. No need for flowery adjectives here.

- The best story you will tell is going to come from your personal experience.

- Use mysteries that will nag the reader. For example, at the beginning of the essay, we learn about the “vanished husband” but there’s no explanation. We have to keep reading to get the answer.

- Explain it in simple terms: “You’ve got your solid, your liquid, your gas, and then your plasma”. Why complicate?

33. Terence McKenna – Tryptamine Hallucinogens and Consciousness

To me, Terence McKenna was one of the most interesting thinkers of the twentieth century. His many lectures (now available on YouTube) attracted millions of people who suspect that consciousness holds secrets yet to be unveiled. McKenna consumed psychedelic drugs for most of his life and it shows (in a positive way). Many people consider him a looney, and a hippie, but he was so much more than that. He dared to go into the abyss of his psyche and come back to tell the tale. He also wrote many books (the most famous being Food Of The Gods ), built a huge botanical garden in Hawaii , lived with shamans, and was a connoisseur of all things enigmatic and obscure. Take a look at this essay, and learn more about the explorations of the subconscious mind.

- Become the original thinker, but remember that it may require extraordinary measures: “I call myself an explorer rather than a scientist because the area that I’m looking at contains insufficient data to support even the dream of being a science”.

- Learn new words every day to make your thoughts lucid.

- Come up with the most outlandish ideas to push the envelope of what’s possible. Don’t take things for granted or become intellectually lazy. Question everything.

34. Eudora Welty – The Little Store

By reading this little-known essay, you will be transported into the world of the old American South. It’s a remembrance of trips to the little store in a little town. It’s warm and straightforward, and when you read it, you feel like a child once more. All these beautiful memories live inside of us. They lay somewhere deep in our minds, hidden from sight. The work by Eudora Welty is an attempt to uncover some of them and let you get reacquainted with some smells and tastes of the past.

- When you’re from the South, flaunt it. It’s still good old English but sometimes it sounds so foreign. I can hear the Southern accent too: “There were almost tangible smells – licorice recently sucked in a child’s cheek, dill-pickle brine that had leaked through a paper sack in a fresh trail across the wooden floor, ammonia-loaded ice that had been hoisted from wet Croker sacks and slammed into the icebox with its sweet butter at the door, and perhaps the smell of still-untrapped mice”.

- Yet again, never forget your roots.

- Childhood stories can be the most powerful ones. You can write about how they shaped you.

35. John McPhee – The Search for Marvin Gardens

The Search for Marvin Gardens contains many layers of meaning. It’s a story about a Monopoly championship, but also, it’s the author’s search for the lost streets visible on the board of the famous board game. It also presents a historical perspective on the rise and fall of civilizations, and on Atlantic City, which once was a lively place, and then, slowly declined, the streets filled with dirt and broken windows.

- There’s nothing like irony: “A sign- ‘Slow, Children at Play’- has been bent backward by an automobile”.

- Telling the story in apparently unrelated fragments is sometimes better than telling the whole thing in a logical order.

- Creativity is everything. The best writing may come just from connecting two ideas and mixing them to achieve a great effect. Shush! The muse is whispering.

36. Maxine Hong Kingston – No Name Woman

A dead body at the bottom of the well makes for a beautiful literary device. The first line of Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name Is Red delivers it perfectly: “I am nothing but a corpse now, a body at the bottom of a well”. There’s something creepy about the idea of the well. Just think about the “It puts the lotion in the basket” scene from The Silence of the Lambs. In the first paragraph of Kingston’s essay, we learn about a suicide committed by uncommon means of jumping into the well. But this time it’s a real story. Who was this woman? Why did she do it? Read the essay.

- Mysterious death always gets attention. The macabre details are like daiquiris on a hot day – you savor them – you don’t let them spill.

- One sentence can speak volumes: “But the rare urge west had fixed upon our family, and so my aunt crossed boundaries not delineated in space”.

- It’s interesting to write about cultural differences – especially if you have the relevant experience. Something normal for us is unthinkable for others. Show this different world.

- The subject of sex is never boring.

37. Joan Didion – On Keeping A Notebook

Slouching Towards Bethlehem is one of the most famous collections of essays of all time. In it, you will find a curious piece called On Keeping A Notebook. It’s not only a meditation about keeping a journal. It’s also Didion’s reconciliation with her past self. After reading it, you will seriously reconsider your life’s choices and look at your life from a wider perspective.

- When you write things down in your journal, be more specific – unless you want to write a deep essay about it years later.

- Use the beauty of the language to relate to the past: “I have already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be; one of them, a seventeen-year-old, presents little threat, although it would be of some interest to me to know again what it feels like to sit on a river levee drinking vodka-and-orange-juice and listening to Les Paul and Mary Ford and their echoes sing ‘How High the Moon’ on the car radio”.

- Drop some brand names if you want to feel posh.

38. Joan Didion – Goodbye To All That

This one touched me because I also lived in New York City for a while. I don’t know why, but stories about life in NYC are so often full of charm and this eerie-melancholy-jazz feeling. They are powerful. They go like this: “There was a hard blizzard in NYC. As the sound of sirens faded, Tony descended into the dark world of hustlers and pimps.” That’s pulp literature but in the context of NYC, it always sounds cool. Anyway, this essay is amazing in too many ways. You just have to read it.

- Talk about New York City. They will read it.

- Talk about the human experience: “It did occur to me to call the desk and ask that the air conditioner be turned off, I never called, because I did not know how much to tip whoever might come—was anyone ever so young?”

- Look back at your life and reexamine it. Draw lessons from it.

39. George Orwell – Reflections on Gandhi

George Orwell could see things as they were. No exaggeration, no romanticism – just facts. He recognized totalitarianism and communism for what they were and shared his worries through books like 1984 and Animal Farm . He took the same sober approach when dealing with saints and sages. Today, we regard Gandhi as one of the greatest political leaders of the twentieth century – and rightfully so. But did you know that when asked about the Jews during World War II, Gandhi said that they should commit collective suicide and that it: “would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler’s violence.” He also recommended utter pacifism in 1942, during the Japanese invasion, even though he knew it would cost millions of lives. But overall he was a good guy. Read the essay and broaden your perspective on the Bapu of the Indian Nation.

- Share a philosophical thought that stops the reader for a moment: “No doubt alcohol, tobacco, and so forth are things that a saint must avoid, but sainthood is also a thing that human beings must avoid”.

- Be straightforward in your writing – no mannerisms, no attempts to create ‘style’, and no invocations of the numinous – unless you feel the mystical vibe.

40. George Orwell – Politics and the English Language

Let Mr. Orwell give you some writing tips. Written in 1946, this essay is still one of the most helpful documents on writing in English. Orwell was probably the first person who exposed the deliberate vagueness of political language. He was very serious about it and I admire his efforts to slay all unclear sentences (including ones written by distinguished professors). But it’s good to make it humorous too from time to time. My favorite examples of that would be the immortal Soft Language sketch by George Carlin or the “Romans Go Home” scene from Monty Python’s Life of Brian. Overall, it’s a great essay filled with examples from many written materials. It’s a must-read for any writer.

- Listen to the master: “This mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence is the most marked characteristic of modern English prose.” Do something about it.

- This essay is all about writing better, so go to the source if you want the goodies.

Other Essays You May Find Interesting

The list that I’ve prepared is by no means complete. The literary world is full of exciting essays and you’ll never know which one is going to change your life. I’ve found reading essays very rewarding because sometimes, a single one means more than reading a whole book. It’s almost like wandering around and peeking into the minds of the greatest writers and thinkers that ever lived. To make this list more comprehensive, below I included more essays you may find interesting.

Oliver Sacks – On Libraries

One of the greatest contributors to the knowledge about the human mind, Oliver Sacks meditates on the value of libraries and his love of books.

Noam Chomsky – The Responsibility of Intellectuals

Chomsky did probably more than anyone else to define the role of the intelligentsia in the modern world . There is a war of ideas over there – good and bad – intellectuals are going to be those who ought to be fighting for the former.

Sam Harris – The Riddle of The Gun

Sam Harris, now a famous philosopher and neuroscientist, takes on the problem of gun control in the United States. His thoughts are clear of prejudice. After reading this, you’ll appreciate the value of logical discourse overheated, irrational debate that more often than not has real implications on policy.

Tim Ferriss – Some Practical Thoughts on Suicide

This piece was written as a blog post , but it’s worth your time. The author of the NYT bestseller The 4-Hour Workweek shares an emotional story about how he almost killed himself, and what can you do to save yourself or your friends from suicide.

Edward Said – Reflections on Exile

The life of Edward Said was a truly fascinating one. Born in Jerusalem, he lived between Palestine and Egypt and finally settled down in the United States, where he completed his most famous work – Orientalism. In this essay, he shares his thoughts about what it means to be in exile.

Richard Feynman – It’s as Simple as One, Two, Three…

Richard Feynman is one of the most interesting minds of the twentieth century. He was a brilliant physicist, but also an undeniably great communicator of science, an artist, and a traveler. By reading this essay, you can observe his thought process when he tries to figure out what affects our perception of time. It’s a truly fascinating read.

Rabindranath Tagore – The Religion of The Forest

I like to think about Tagore as my spiritual Friend. His poems are just marvelous. They are like some of the Persian verses that praise love, nature, and the unity of all things. By reading this short essay, you will learn a lot about Indian philosophy and its relation to its Western counterpart.

Richard Dawkins – Letter To His 10-Year-Old Daughter

Every father should be able to articulate his philosophy of life to his children. With this letter that’s similar to what you find in the Paris Review essays , the famed atheist and defender of reason, Richard Dawkins, does exactly that. It’s beautifully written and stresses the importance of looking at evidence when we’re trying to make sense of the world.

Albert Camus – The Minotaur (or, The Stop In Oran)

Each person requires a period of solitude – a period when one’s able to gather thoughts and make sense of life. There are many places where you may attempt to find quietude. Albert Camus tells about his favorite one.

Koty Neelis – 21 Incredible Life Lessons From Anthony Bourdain

I included it as the last one because it’s not really an essay, but I just had to put it somewhere. In this listicle, you’ll find the 21 most original thoughts of the high-profile cook, writer, and TV host, Anthony Bourdain. Some of them are shocking, others are funny, but they’re all worth checking out.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca – On the Shortness of Life

It’s similar to the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam because it praises life. Seneca shares some of his stoic philosophy and tells you not to waste your time on stupidities. Drink! – for once dead you shall never return.

Bertrand Russell – In Praise of Idleness

This old essay is a must-read for modern humans. We are so preoccupied with our work, our phones, and all the media input we drown in our business. Bertrand Russell tells you to chill out a bit – maybe it will do you some good.

James Baldwin – Stranger in the Village

It’s an essay on the author’s experiences as an African-American in a Swiss village, exploring race, identity, and alienation while highlighting the complexities of racial dynamics and the quest for belonging.

Bonus – More writing tips from two great books

The mission to improve my writing skills took me further than just going through the essays. I’ve come across some great books on writing too. I highly recommend you read them in their entirety. They’re written beautifully and contain lots of useful knowledge. Below you’ll find random (but useful) notes that I took from The Sense of Style and On Writing.

The Sense of Style – By Steven Pinker

- Style manuals are full of inconsistencies. Following their advice might not be the best idea. They might make your prose boring.

- Grammarians from all eras condemn students for not knowing grammar. But it just evolves. It cannot be rigid.

- “Nothing worth learning can be taught” – Oscar Wilde. It’s hard to learn to write from a manual – you have to read, write, and analyze.

- Good writing makes you imagine things and feel them for yourself – use word pictures.

- Don’t fear using voluptuous words.

- Phonesthetics – or how the words sound.

- Use parallel language (consistency of tense).

- Good writing finishes strong.

- Write to someone. Never write for no one in mind. Try to show people your view of the world.

- Don’t tell everything you are going to say in summary (signposting) – be logical, but be conversational.

- Don’t be pompous.

- Don’t use quotation marks where they don’t “belong”. Be confident about your style.

- Don’t hedge your claims (research first, and then tell it like it is).

- Avoid clichés and meta-concepts (concepts about concepts). Be more straightforward!

- Not prevention – but prevents or prevented – don’t use dead nouns.

- Be more vivid while using your mother tongue – don’t use passive where it’s not needed. Direct the reader’s gaze to something in the world.

- The curse of knowledge – the reader doesn’t know what you know – beware of that.

- Explain technical terms.

- Use examples when you explain a difficult term.

- If you ever say “I think I understand this” it probably means you don’t.

- It’s better to underestimate the lingo of your readers than to overestimate it.

- Functional fixedness – if we know some object (or idea) well, we tend to see it in terms of usage, not just as an object.

- Use concrete language instead of an abstraction.

- Show your work to people before you publish (get feedback!).

- Wait for a few days and then revise, revise, revise. Think about clarity and the sound of sentences. Then show it to someone. Then revise one more time. Then publish (if it’s to be serious work).

- Look at it from the perspective of other people.

- Omit needless words.

- Put the heaviest words at the end of the sentence.

- It’s good to use the passive, but only when appropriate.

- Check all text for cohesion. Make sure that the sentences flow gently.

- In expository work, go from general to more specific. But in journalism start from the big news and then give more details.

- Use the paragraph break to give the reader a moment to take a breath.

- Use the verb instead of a noun (make it more active) – not “cancellation”, but “canceled”. But after you introduce the action, you can refer to it with a noun.

- Avoid too many negations.

- If you write about why something is so, don’t spend too much time writing about why it is not.

On Writing Well – By William Zinsser

- Writing is a craft. You need to sit down every day and practice your craft.

- You should re-write and polish your prose a lot.

- Throw out all the clutter. Don’t keep it because you like it. Aim for readability.

- Look at the best examples of English literature . There’s hardly any needless garbage there.

- Use shorter expressions. Don’t add extra words that don’t bring any value to your work.

- Don’t use pompous language. Use simple language and say plainly what’s going on (“because” equals “because”).

- The media and politics are full of cluttered prose (because it helps them to cover up for their mistakes).

- You can’t add style to your work (and especially, don’t add fancy words to create an illusion of style). That will look fake. You need to develop a style.

- Write in the “I” mode. Write to a friend or just for yourself. Show your personality. There is a person behind the writing.

- Choose your words carefully. Use the dictionary to learn different shades of meaning.

- Remember about phonology. Make music with words .

- The lead is essential. Pull the reader in. Otherwise, your article is dead.

- You don’t have to make the final judgment on any topic. Just pick the right angle.

- Do your research. Not just obvious research, but a deep one.

- When it’s time to stop, stop. And finish strong. Think about the last sentence. Surprise them.

- Use quotations. Ask people. Get them talking.

- If you write about travel, it must be significant to the reader. Don’t bother with the obvious. Choose your words with special care. Avoid travel clichés at all costs. Don’t tell that the sand was white and there were rocks on the beach. Look for the right detail.

- If you want to learn how to write about art, travel, science, etc. – read the best examples available. Learn from the masters.

- Concentrate on one big idea (“Let’s not go peeing down both legs”).

- “The reader has to feel that the writer is feeling good.”

- One very helpful question: “What is the piece really about?” (Not just “What the piece is about?”)

Now immerse yourself in the world of essays

By reading the essays from the list above, you’ll become a better writer , a better reader, but also a better person. An essay is a special form of writing. It is the only literary form that I know of that is an absolute requirement for career or educational advancement. Nowadays, you can use an AI essay writer or an AI essay generator that will get the writing done for you, but if you have personal integrity and strong moral principles, avoid doing this at all costs. For me as a writer, the effect of these authors’ masterpieces is often deeply personal. You won’t be able to find the beautiful thoughts they contain in any other literary form. I hope you enjoy the read and that it will inspire you to do your writing. This list is only an attempt to share some of the best essays available online. Next up, you may want to check the list of magazines and websites that accept personal essays .

Get your free PDF report: Download your guide to 100+ AI marketing tools and learn how to thrive as a marketer in the digital era.

Rafal Reyzer

Hey there, welcome to my blog! I'm a full-time entrepreneur building two companies, a digital marketer, and a content creator with 10+ years of experience. I started RafalReyzer.com to provide you with great tools and strategies you can use to become a proficient digital marketer and achieve freedom through online creativity. My site is a one-stop shop for digital marketers, and content enthusiasts who want to be independent, earn more money, and create beautiful things. Explore my journey here , and don't miss out on my AI Marketing Mastery online course.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The 10 Best Essay Collections of the Decade

Ever tried. ever failed. no matter..

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels , the best short story collections , the best poetry collections , and the best memoirs of the decade , and we have now reached the fifth list in our series: the best essay collections published in English between 2010 and 2019.

The following books were chosen after much debate (and several rounds of voting) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

The Top Ten

Oliver sacks, the mind’s eye (2010).

Toward the end of his life, maybe suspecting or sensing that it was coming to a close, Dr. Oliver Sacks tended to focus his efforts on sweeping intellectual projects like On the Move (a memoir), The River of Consciousness (a hybrid intellectual history), and Hallucinations (a book-length meditation on, what else, hallucinations). But in 2010, he gave us one more classic in the style that first made him famous, a form he revolutionized and brought into the contemporary literary canon: the medical case study as essay. In The Mind’s Eye , Sacks focuses on vision, expanding the notion to embrace not only how we see the world, but also how we map that world onto our brains when our eyes are closed and we’re communing with the deeper recesses of consciousness. Relaying histories of patients and public figures, as well as his own history of ocular cancer (the condition that would eventually spread and contribute to his death), Sacks uses vision as a lens through which to see all of what makes us human, what binds us together, and what keeps us painfully apart. The essays that make up this collection are quintessential Sacks: sensitive, searching, with an expertise that conveys scientific information and experimentation in terms we can not only comprehend, but which also expand how we see life carrying on around us. The case studies of “Stereo Sue,” of the concert pianist Lillian Kalir, and of Howard, the mystery novelist who can no longer read, are highlights of the collection, but each essay is a kind of gem, mined and polished by one of the great storytellers of our era. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

John Jeremiah Sullivan, Pulphead (2011)

The American essay was having a moment at the beginning of the decade, and Pulphead was smack in the middle. Without any hard data, I can tell you that this collection of John Jeremiah Sullivan’s magazine features—published primarily in GQ , but also in The Paris Review , and Harper’s —was the only full book of essays most of my literary friends had read since Slouching Towards Bethlehem , and probably one of the only full books of essays they had even heard of.

Well, we all picked a good one. Every essay in Pulphead is brilliant and entertaining, and illuminates some small corner of the American experience—even if it’s just one house, with Sullivan and an aging writer inside (“Mr. Lytle” is in fact a standout in a collection with no filler; fittingly, it won a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize). But what are they about? Oh, Axl Rose, Christian Rock festivals, living around the filming of One Tree Hill , the Tea Party movement, Michael Jackson, Bunny Wailer, the influence of animals, and by god, the Miz (of Real World/Road Rules Challenge fame).

But as Dan Kois has pointed out , what connects these essays, apart from their general tone and excellence, is “their author’s essential curiosity about the world, his eye for the perfect detail, and his great good humor in revealing both his subjects’ and his own foibles.” They are also extremely well written, drawing much from fictional techniques and sentence craft, their literary pleasures so acute and remarkable that James Wood began his review of the collection in The New Yorker with a quiz: “Are the following sentences the beginnings of essays or of short stories?” (It was not a hard quiz, considering the context.)

It’s hard not to feel, reading this collection, like someone reached into your brain, took out the half-baked stuff you talk about with your friends, researched it, lived it, and represented it to you smarter and better and more thoroughly than you ever could. So read it in awe if you must, but read it. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Aleksandar Hemon, The Book of My Lives (2013)

Such is the sentence-level virtuosity of Aleksandar Hemon—the Bosnian-American writer, essayist, and critic—that throughout his career he has frequently been compared to the granddaddy of borrowed language prose stylists: Vladimir Nabokov. While it is, of course, objectively remarkable that anyone could write so beautifully in a language they learned in their twenties, what I admire most about Hemon’s work is the way in which he infuses every essay and story and novel with both a deep humanity and a controlled (but never subdued) fury. He can also be damn funny. Hemon grew up in Sarajevo and left in 1992 to study in Chicago, where he almost immediately found himself stranded, forced to watch from afar as his beloved home city was subjected to a relentless four-year bombardment, the longest siege of a capital in the history of modern warfare. This extraordinary memoir-in-essays is many things: it’s a love letter to both the family that raised him and the family he built in exile; it’s a rich, joyous, and complex portrait of a place the 90s made synonymous with war and devastation; and it’s an elegy for the wrenching loss of precious things. There’s an essay about coming of age in Sarajevo and another about why he can’t bring himself to leave Chicago. There are stories about relationships forged and maintained on the soccer pitch or over the chessboard, and stories about neighbors and mentors turned monstrous by ethnic prejudice. As a chorus they sing with insight, wry humor, and unimaginable sorrow. I am not exaggerating when I say that the collection’s devastating final piece, “The Aquarium”—which details his infant daughter’s brain tumor and the agonizing months which led up to her death—remains the most painful essay I have ever read. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (2013)

Of every essay in my relentlessly earmarked copy of Braiding Sweetgrass , Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s gorgeously rendered argument for why and how we should keep going, there’s one that especially hits home: her account of professor-turned-forester Franz Dolp. When Dolp, several decades ago, revisited the farm that he had once shared with his ex-wife, he found a scene of destruction: The farm’s new owners had razed the land where he had tried to build a life. “I sat among the stumps and the swirling red dust and I cried,” he wrote in his journal.

So many in my generation (and younger) feel this kind of helplessness–and considerable rage–at finding ourselves newly adult in a world where those in power seem determined to abandon or destroy everything that human bodies have always needed to survive: air, water, land. Asking any single book to speak to this helplessness feels unfair, somehow; yet, Braiding Sweetgrass does, by weaving descriptions of indigenous tradition with the environmental sciences in order to show what survival has looked like over the course of many millennia. Kimmerer’s essays describe her personal experience as a Potawotami woman, plant ecologist, and teacher alongside stories of the many ways that humans have lived in relationship to other species. Whether describing Dolp’s work–he left the stumps for a life of forest restoration on the Oregon coast–or the work of others in maple sugar harvesting, creating black ash baskets, or planting a Three Sisters garden of corn, beans, and squash, she brings hope. “In ripe ears and swelling fruit, they counsel us that all gifts are multiplied in relationship,” she writes of the Three Sisters, which all sustain one another as they grow. “This is how the world keeps going.” –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Hilton Als, White Girls (2013)

In a world where we are so often reduced to one essential self, Hilton Als’ breathtaking book of critical essays, White Girls , which meditates on the ways he and other subjects read, project and absorb parts of white femininity, is a radically liberating book. It’s one of the only works of critical thinking that doesn’t ask the reader, its author or anyone he writes about to stoop before the doorframe of complete legibility before entering. Something he also permitted the subjects and readers of his first book, the glorious book-length essay, The Women , a series of riffs and psychological portraits of Dorothy Dean, Owen Dodson, and the author’s own mother, among others. One of the shifts of that book, uncommon at the time, was how it acknowledges the way we inhabit bodies made up of variously gendered influences. To read White Girls now is to experience the utter freedom of this gift and to marvel at Als’ tremendous versatility and intelligence.

He is easily the most diversely talented American critic alive. He can write into genres like pop music and film where being part of an audience is a fantasy happening in the dark. He’s also wired enough to know how the art world builds reputations on the nod of rich white patrons, a significant collision in a time when Jean-Michel Basquiat is America’s most expensive modern artist. Als’ swerving and always moving grip on performance means he’s especially good on describing the effect of art which is volatile and unstable and built on the mingling of made-up concepts and the hard fact of their effect on behavior, such as race. Writing on Flannery O’Connor for instance he alone puts a finger on her “uneasy and unavoidable union between black and white, the sacred and the profane, the shit and the stars.” From Eminem to Richard Pryor, André Leon Talley to Michael Jackson, Als enters the life and work of numerous artists here who turn the fascinations of race and with whiteness into fury and song and describes the complexity of their beauty like his life depended upon it. There are also brief memoirs here that will stop your heart. This is an essential work to understanding American culture. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Eula Biss, On Immunity (2014)

We move through the world as if we can protect ourselves from its myriad dangers, exercising what little agency we have in an effort to keep at bay those fears that gather at the edges of any given life: of loss, illness, disaster, death. It is these fears—amplified by the birth of her first child—that Eula Biss confronts in her essential 2014 essay collection, On Immunity . As any great essayist does, Biss moves outward in concentric circles from her own very private view of the world to reveal wider truths, discovering as she does a culture consumed by anxiety at the pervasive toxicity of contemporary life. As Biss interrogates this culture—of privilege, of whiteness—she interrogates herself, questioning the flimsy ways in which we arm ourselves with science or superstition against the impurities of daily existence.

Five years on from its publication, it is dismaying that On Immunity feels as urgent (and necessary) a defense of basic science as ever. Vaccination, we learn, is derived from vacca —for cow—after the 17th-century discovery that a small application of cowpox was often enough to inoculate against the scourge of smallpox, an etymological digression that belies modern conspiratorial fears of Big Pharma and its vaccination agenda. But Biss never scolds or belittles the fears of others, and in her generosity and openness pulls off a neat (and important) trick: insofar as we are of the very world we fear, she seems to be suggesting, we ourselves are impure, have always been so, permeable, vulnerable, yet so much stronger than we think. –Jonny Diamond, Editor-in-Chief

Rebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions (2016)

When Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “Men Explain Things to Me,” was published in 2008, it quickly became a cultural phenomenon unlike almost any other in recent memory, assigning language to a behavior that almost every woman has witnessed—mansplaining—and, in the course of identifying that behavior, spurring a movement, online and offline, to share the ways in which patriarchal arrogance has intersected all our lives. (It would also come to be the titular essay in her collection published in 2014.) The Mother of All Questions follows up on that work and takes it further in order to examine the nature of self-expression—who is afforded it and denied it, what institutions have been put in place to limit it, and what happens when it is employed by women. Solnit has a singular gift for describing and decoding the misogynistic dynamics that govern the world so universally that they can seem invisible and the gendered violence that is so common as to seem unremarkable; this naming is powerful, and it opens space for sharing the stories that shape our lives.

The Mother of All Questions, comprised of essays written between 2014 and 2016, in many ways armed us with some of the tools necessary to survive the gaslighting of the Trump years, in which many of us—and especially women—have continued to hear from those in power that the things we see and hear do not exist and never existed. Solnit also acknowledges that labels like “woman,” and other gendered labels, are identities that are fluid in reality; in reviewing the book for The New Yorker , Moira Donegan suggested that, “One useful working definition of a woman might be ‘someone who experiences misogyny.'” Whichever words we use, Solnit writes in the introduction to the book that “when words break through unspeakability, what was tolerated by a society sometimes becomes intolerable.” This storytelling work has always been vital; it continues to be vital, and in this book, it is brilliantly done. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Valeria Luiselli, Tell Me How It Ends (2017)