How to apply for a PhD in Australia

Knowing where to start when applying for a phd can be tricky, especially when applying for one in a different country. this guide from monash university explains all the key information you need when applying for a phd in australia, amarpreet abraham, .css-76pyzs{margin-right:0.25rem;} ,, fiona lilley.

/student/advice/what-phd-advice-phd-students Applying for a PhD is a big step in anyone’s academic career. While it may sometimes seem like a daunting and often quite lengthy process, applying for a PhD shouldn’t have to be a chore and the way you do so varies by country and university. To make this process as clear as possible, Fiona Lilley from the graduate research office at Monash University in Australia answers the most pressing questions when it comes to applying, especially as an international student. With help from Monash PhD student and teaching associate, Amarpreet Abraham, this will be your go-to for all things PhD in Australia.

How can I apply for a PhD in Australia as an international student?

When applying to study a PhD in Australia, applicants are encouraged to identify possible academic supervisors and contact the faculty they would be enrolling in. Each university will have its own process, so it is important to familiarise yourself with the enquiry and application process. Not following the process or having the incorrect documentation can result in delays. For example, at Monash there is a two-step process. First, applicants submit an “Expression of Interest” (EOI) to the faculty where they intend to study; each faculty has different requirements, so it is important to check what is required. If the faculty determines that they have resources and facilities to support the student project, they will issue an Invitation to Apply (ITA), permitting the applicant to make a formal application for admission (and scholarships).

Get free support to study in Australia and New Zealand

Is there a correct/recommended way to look for a supervisor.

The right supervisory match for the student and their project is crucial. Universities have different processes – some require a supervisor to confirm they will supervise before an application; others may appoint a suitable supervisor for the student’s project. In Australia there is a requirement for all research students to have a minimum of two supervisors. Most universities will have several options to support applicants in identifying and connecting with supervisors, such as a Find a Researcher database. This is an extensive resource of all academic research in the university.

Top tip : Look for the “Available to supervise PhD” indicator on a researcher’s profile. “When looking for a supervisor it is important that they are involved in your field in some way. A prospective supervisor could be someone you have a pre-established positive academic relationship with, where you work well together or are aware of the expectations and boundaries from this academic,” says Amarpreet Abraham.

Do you have any tips for finding the right supervisor?

First step would be to decide which university you would like to do your PhD at and approach researchers depending on your interests – this could include emailing them with a brief research proposal and why they are best suited to your project. From there, the prospective supervisor can let you know if they are interested in your proposal/have availability to take on a new PhD student. “Picking someone with the knowledge of your field is important, but I would stress that choosing a supervisor who you have a positive working relationship with is even more vital,” says Abraham.

When should I start applying for my PhD?

Start initial conversations as early as you can. In some instances, potential supervisors may want to review a research proposal, interview the applicant and identify if the project scope is something that they have the capacity and resources or facilities to supervise.

There is no hard and fast rule on when you should start your application, but it is always advisable to start researching supervisors and topics as soon as you can.

How long will the application process take?

Each university will have different processes, deadlines and outcome notification dates. At Monash, it is generally six weeks after closing for the notification of either scholarship offer or admission offer to be sent.

This also depends on the time of year, volume of applications and, most importantly, whether the applicant has submitted all the required documentation, such as academic transcripts and evidence of English language proficiency.

How should I approach writing my research proposal?

Universities and supervisors will have different approaches to research proposals, so it is important to check and understand the requirements before you start. According to Abraham, “a research proposal should include a tentative title, an abstract, an introduction, proposed theoretical/conceptual framework, research questions, significance of the study, limitations, literature review, methodology/research approach, data collection and analysis methods, and a reference list. For all the criteria of the research proposal to be fulfilled, a lot of thought and discussion with your potential supervisor(s) is required. This allows you to voice your interests and approaches for your PhD, while your supervisors can make suggestions on what they think is best suited for your research. It is also important to note that all the elements of the thesis outlined above change/develop as the PhD candidature progresses.”

What are the associated costs of applying for a PhD in Australia?

This will differ depending on the university, and in some instances whether an applicant chooses to engage a registered agent to assist them with their application. At present, there is no application fee at Monash for international PhD or masters by research applicants. Other fees, including tuition fee costs, are published on university websites. Depending on the course, there may be associated costs for laboratory materials or travel for study (such as fieldwork). Applicants should check with the university and the faculty to understand what these may be. The Australian Government requires service providers to provide full details of course tuition and non-tuition costs in any formal offer or International Student Contract.

What would be your top pieces of advice for someone looking to apply for a PhD?

“Find a supervisor you work well with, be prepared, attend workshops around how to do research and practice self-care and self-kindness right from the beginning. It is easy to lose sight of boundaries when doing a PhD, but it is essential to look after yourself because life continues to happen at full speed while you are pursuing a PhD. I would also recommend getting involved in social research groups, as a PhD can be an isolating endeavour and having others who are in a similar position as you can be reassuring,” Abraham concludes.

You may also like

.css-185owts{overflow:hidden;max-height:54px;text-indent:0px;} How to apply for a PhD in the UK

Ben Osborne

How to apply for a PhD in the US

Giulia Evolvi

Best universities in Australia 2024

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

A Guide to Doing Your PhD in Australia

Sign up to our newsletter!

The newsletter signup widget on posts

- Name * First Last

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

If you’re an international student who has completed higher education studies, you might now be considering studying a doctorate degree, also known as a PhD. In Australia, this is the highest level of study and, once completed, can unlock doors to better employment, higher wages, and industry recognition.

Here’s a handy guide on how to apply, what to expect, and where to find further information for your exciting next step.

What is the difference between honours, a master ’s and a PhD?

An honours is an extra year of study in Australia. To qualify you need to have completed your undergraduate degree, otherwise known as a bachelor’s degree, to a high standard. This is often considered a stepping stone to further postgraduate study.

Graduates with a bachelor’s degree might consider a graduate certificate, which usually takes one semester of full-time study and can help you specialise in your chosen career path. One step up from a certificate is a graduate diploma. This type of study takes one year of full-time study and can often be continued on from the graduate certificate.

A master’s by coursework is similar to a graduate diploma but takes a little longer and is regarded as a higher qualification. In most cases, you need a relevant bachelor’s degree; however, in certain circumstances, extensive relevant work experience might be accepted instead. This type of course typically takes 18 months to complete. A master’s by research takes two years of full-time study and is based on a research project supervised by a university academic.

A doctorate by research or a PhD is the highest level of study offered in Australia. A PhD requires submission of a thesis that is assessed by examiners who determine whether the research is worthy of the qualification. A PhD student must show through their thesis that they have made a significant contribution to their field. Once graduated, the candidate may use the title of Doctor.

How does a PhD work in Australia?

A PhD in Australia is usually studied over the course of three years. While some students take a little longer, extensions are subject to funding, as well as other important factors. Domestic students may have the option to study part-time but as an international student, you must study full-time in order to be eligible for a student visa .

According to the Australian Government , fees to study a PhD range from A$19,000 to A$78,000 per year, depending on the education provider. There is a chance you may not have to pay the full amount if there is funding available, which is common in Australia. Most universities have funding for promising PhD students set aside. Get in touch with your chosen university directly to find out what scholarships are available to international students. The Australian Government also runs Destination Australia , which funds eligible education providers in regional areas to offer scholarships to both domestic and international students. The government also offers the Research Training Program for participating universities.

International students also need to consider the cost of living while abroad to qualify for their visa. You’ll need at least roughly A$21,041 for each year of your study in your bank account in order to be granted a visa.

Do I need honours to apply for a PhD?

In most cases you will need an undergraduate degree with a minimum of Second Class Honours (Division A) – also known as ‘upper second-class’ honours – to apply for your PhD to demonstrate you have significant research experience. However, many education providers offer research-based qualifications to give you this experience if you didn’t complete an honours degree originally.

What is the basic structure of a PhD?

PhDs in Australia are usually research-based and, while they may contain other aspects, the focus of your studies will be on working towards your doctoral thesis.

In general, a PhD begins with a literature review that collects, analyses and summarises the current research published on your chosen subject. This then provides the basis for designing, implementing and analysing your own research that you’ll write about for your thesis.

In Australia, you are not required to undergo a viva voca , which is an assessed oral exam in defence of your research topic, method and predicted results. Instead, you are assessed solely on your thesis.

How do I apply for a PhD?

To apply for an Australian PhD, the first step is to contact a university academic working as a supervisor for PhD projects. You contact them, usually about four months before you wish to commence your studies, with the research topic you would like to propose. The person you choose should be the lead researcher for the institution you wish to apply to, in the relevant field you wish to study.

Once you have what is known as an ‘expression of interest’ from a provisional supervisor, you can begin your formal application to the university. Most universities won’t consider an application without an expression of interest from a supervisor, so make sure you have this first.

What else do I need to know?

To study as an international student in Australia, you must have a student visa (subclass 500) from the Australian government. Unless you are exempt, the application fee for this visa is AUD$710. You can read more about student visas and their requirements here .

Australian PhDs are delivered in English and have language skill requirements. There are various tests you can take to verify your English language skills including the IELTS, CAE and PTE. The score you need is usually specified on the universities website and will depend on the test you take.

International students must have Overseas Student Health Cover (OSHC) in order to be granted their student visa. There are a variety of providers to choose from, including many universities, but the policy you choose must adhere to the Overseas Student Health Cover guides. Explore your options in greater detail here .

The new international student working limit of 48 hours every fortnight does not apply to international students who are pursuing a doctorate or a master’s degree through research. These students are not restricted in terms of the number of hours they can work. However, your actual work hours should align with your study requirements and also require approval from your academic supervisor. This is to ensure that your employment does not interfere with your primary objective of completing your academic research.

PhD study is an excellent way to enter the Australian workforce and graduate visas are available that can entitle you to stay in Australia for up to four years after you have finished your PhD. In other words, if you have dreams of both furthering your education and settling long-term in Australia, a PhD could be the perfect way to make those dreams a reality.

Sarah Price

Originally from the UK, Sarah has worked as a freelance writer for nearly 10 years, both at home and now in Perth where she lives. Once an international student in South West WA herself, she loves to help new students feel welcome, confident, and ready to make the most of their study abroad. Having lived in Perth and explored a lot of WA, Sarah knows just how wonderful it is to discover this beautiful state.

Related Articles

A Guide to Universities in Victoria

What is Vocational Education and Training (VET)?

areas of canberra

10 Student-Friendly Canberra Suburbs You May Not Know

Quick links

- Climate change

- COVID-19 research

- Staff profiles

CSIRO Industry PhD scholarship program

Preparing PhD researchers to create impact with industry.

About the Industry PhD Program

CSIRO's Industry PhD (iPhD) program brings together an industry partner, a university and Australia’s leading science agency, CSIRO, to co-develop a four-year industry-focused PhD project. PhD students will gain unique skills to focus on impact-driven research. The iPhD program part of an Australian Government initiative to better translate university research into commercial outcomes. View our current student scholarships and Program Rules. PDF (498 KB)

- View transcript

- Copy embed code

Share & embed this video

https://www.youtube.com/embed/B5hUQn5YdHE?autoplay=1&start=0

<iframe src="https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/B5hUQn5YdHE?autoplay=1&start=0" width="640" height="360" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Information for students and industry

Join us to study a PhD with industry and university support. Our students receive a generous scholarship and get real-world experience.

Current scholarships

See our list of current projects. Gain experience working with industry to solve real-world problems while earning your PhD.

Tackle your business challenge. Gain access to top research and development expertise while developing the next generation of researchers.

Read our case studies

Collaborative research projects with industry and university..

Discover how iPhD students are helping to solve real world challenges.

Information for universities and CSIRO reseachers

Universities.

Drive research translation and commercialisation. Guide your PhD candidates to develop solutions to real-world problems in partnership with industry and CSIRO.

CSIRO researchers

Partner with industry and university to solve challenges. We are always looking for new projects. If you are a CSIRO researcher who has a project idea, find out more here.

Subscribe to our Industry PhD scholarship newsletter

News and updates from our industry phd scholarship program. .

News and updates from our Industry PhD scholarship program.

Find out how we can help you and your business. Get in touch using the form below and our experts will get in contact soon!

CSIRO will handle your personal information in accordance with the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) and our Privacy Policy .

Enter a valid email address, for example [email protected]

A Country value must be provided

First name must be filled in

Surname must be filled in

Please choose an option

Organisation must be filled in

Please provide a subject for the enquriy

We'll need to know what you want to contact us about so we can give you an answer

We have received your enquiry and will reply soon.

We're Sorry

The contact form is currently unavailable. Please try again later. If this problem persists, please call us with your enquiry on 1300 363 400 or +61 3 9545 2176. We are available from 9.00 am to 4.00 pm AEST Monday - Friday.

You're viewing this site as a domestic an international student

You're a domestic student if you are:

- a citizen of Australia or New Zealand,

- an Australian permanent resident, or

- a holder of an Australian permanent humanitarian visa.

You're an international student if you are:

- intending to study on a student visa,

- not a citizen of Australia or New Zealand,

- not an Australian permanent resident, or

- a temporary resident (visa status) of Australia.

How to get a PhD

Study tips Published 5 Apr, 2022 · 4-minute read

Trying to wrap your head around how PhD programs work? We don’t blame you. Sometimes it feels like you need a PhD just to figure out how to get a PhD.

So, with a little help from our academics and some UQ PhD candidates, we’ve broken down the application and preparation process into 10 manageable steps:

- Complete prior research

- Choose your topic

- Find a PhD supervisor

- Write your PhD proposal

- Identify potential scholarships

- Gather required documents and apply

- Determine if you'll continue working during your PhD

- Calculate how long you’ll be researching your PhD

- Develop the traits and behaviours of a good PhD student

- Apply and get accepted

Let’s discuss how to get a PhD in Australia – from choosing your topic to getting stuck into the actual research.

1. Complete prior research (if necessary)

You don’t necessarily need a master’s degree to start a PhD. However, you do need to have completed extensive research. This might involve an academic research program (such as a bachelor's degree with an honours year or a Master of Philosophy ), research conducted in your professional career, or a combination of both. The important thing is that you can demonstrate experience in conducting effective research, as this is a key part of the PhD selection criteria.

Learn more about doing a PhD without a master's degree

2. Choose your topic

Whether you’re developing a thesis on a topic you’ve already worked on or branching out into a new area of interest, you’ll want to know early what kind of topic you want to research for your PhD. Finding a niche that sparks your curiosity is important for ensuring you’ll stay inspired during the 3+ years ahead.

Keep in mind that you generally have two options here. You can complete a PhD by:

- joining an existing research project in an area that interests you

- start a fresh research project that aligns with your specific goals.

Get tips for choosing your PhD topic or explore available research projects at UQ

3. Find a PhD supervisor

One of the essential steps to consider when thinking about how to get a PhD is finding someone to guide you through the process.

Approaching academics about your PhD can be intimidating, but shortlisting and selecting the most appropriate person / team to supervise your research project is important. By choosing your mentor carefully, you can ensure you’ve got someone in your corner who understands your research, has relevant expertise, and will be there to support you throughout your journey.

Learn how to find the right PhD supervisor

4. Write your PhD proposal

Check with your supervisor to see if they require a formal PhD proposal (most will, but not all). If so, with their guidance, it’s time to put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard).

Even if your supervisor doesn't explicitly ask for one, a PhD proposal is a valuable document for outlining the scope of your research and giving your project its initial momentum – so it might be worth writing one either way.

Learn how to write a good PhD proposal

5. Identify potential scholarships

Dedicating yourself to research sometimes means sacrificing your income in the short term, though it can lead to more financial security in the long term . To help support yourself during your studies, you can apply for PhD scholarships and funding.

Learn how to get a PhD scholarship

6. Gather required documents and apply

It’s time to jump online and do the official application process. Aside from your research proposal, you should also prepare to provide your:

- academic CV

- academic transcript

- degree certificate(s)

- English language documents (if needed)

- ID (such as a passport)

- two references / letters of recommendation from people who can comment on your research experience.

Learn how to apply online for a UQ PhD

7. Determine if you'll continue working during your PhD

Some PhD candidates continue doing part-time or casual work while completing their research. However, this isn't easy and may not be feasible in most cases; it takes serious time-management skills to juggle any kind of job alongside a full-time PhD. So, think carefully about whether you’d like to keep working in some capacity or commit your attention fully to your research.

Learn more about working while doing a PhD

8. Calculate how long you’ll be researching your PhD

To complete your PhD within the standard 3.5-year* timeframe, you'll need to be organised with a clear project plan. Of course, the very nature of research is that you'll discover unexpected things and take unplanned detours along the way. So, your plan should include contingencies for any obstacles you might hit to ensure you still complete your research on time.

*In special cases, you may be able to request an extension of your tuition for up to 4 years, but that is the maximum time allowed for a PhD.

Explore how long a PhD takes

9. Develop the traits and behaviours of a good PhD student

We know you’ve already got what it takes, but there are some skills and attributes you could cultivate or practise to make your upcoming journey a little smoother. Between writing your proposal and meeting with potential supervisors, be sure to set some time aside to work on yourself as well.

Discover what makes a good PhD student

10. Apply and get accepted

All the preparation is done. You’ve equipped all the gear, chosen your guide and mapped out your route. It's time to apply and set the wheels in motion.

Submit your PhD application

Share this Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Related stories

How to decide on a PhD topic

4-minute read

How to find a PhD supervisor

5-minute read

How to write a good PhD proposal

How to get a PhD scholarship or funding

3-minute read

Australian PhD graduates’ agency in navigating their career pathways: stories from social sciences

- Open access

- Published: 26 January 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Binh Ta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5252-045X 1 ,

- Cuong Hoang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3131-3803 2 , 3 ,

- Hang Khong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3262-6978 4 &

- Trang Dang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0029-944X 4 , 5

902 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Despite limited opportunities for tenured academic positions, the number of PhD graduates in Social Sciences has steadily risen in countries with developed research systems. The current literature predominantly portrays PhD graduates as victims, either of the higher education system or of their own optimism in pursuing an academic career. This paper takes an alternative stance by spotlighting the agency exhibited by PhD graduates in Social Sciences as they deftly navigate their career pathways amid the constrained academic job market. Specifically, we adopt an ecological perspective of agency to explore how PhD graduates in Social Sciences exercise their agency in navigating their career from the beginning of their PhD candidature until up to 5 years after graduation. We employ a narrative approach to delve into the employment journeys of twenty-three PhD graduates. Within this cohort, we select to report four participants from four Australian universities, each possessing distinct career trajectories. Our analysis highlights agency as the link between various personal and institutional factors that shape our participants’ career trajectories. Based on this finding, we offer recommendations for practice and policy changes that appreciate PhD graduates’ agency.

Similar content being viewed by others

The prospective shift away from academic career aspirations

Brittany Etmanski

Changing Career Pathways: Making Visible the Employment Destinations and Non-academic Contributions of Doctoral Scholars

Ph.D. Pathways to the Professoriate: Affordances and Constraints of Institutional Structures, Individual Agency, and Social Systems

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There has been a significant surge in the number of new PhD graduates over the past few decades in countries with developed research systems (Buenstorf et al., 2023 ; Hancock, 2023 ; OECD, 2021 ). However, academic job markets have shrunk considerably (Guerin, 2020 ), with decreased percentages of tenure academics in Australia (Crimmins, 2017 ; Lama & Joullié, 2015 ), the USA (Feder, 2018 ; Hayter & Parker, 2019 ), the UK as well as many other European countries (Feder, 2018 ; Germain-Alamartine et al., 2021 ; OECD 2021 ). Research on labour markets for PhD holders has identified several prominent labour market trends (despite specific variations across nations). These include a growing availability of non-academic opportunities for PhD holders in the USA (Hayter & Parker, 2019 ) and other OECD countries (OECD 2021 ), a shift towards temporary and contract positions especially in the higher education sector in the UK and Australia (Hancock, 2023 ; Croucher, 2023 ), stronger ties with industry and entrepreneurship in European countries such as the UK, Norway, Sweden, and Italy (Hancock, 2023 ; Germain-Alamartine et al., 2021 ; Marini, 2022 ), and increased global mobility across OECD countries (Auriol et al., 2013 ). These trends emphasise the importance of a broader perspective on career possibilities for PhD holders in a dynamic job market.

Academic job markets exhibit variations depending on the national system. For instance, recent cohorts of doctoral graduates in Germany are more engaged in university-based professional jobs (e.g. administration and management positions) (Buenstorf et al., 2023 , p. 1218). By contrast, recent census data in Australia suggests a growing trend of PhD graduates seeking employment opportunities beyond the academic sector (McCarthy & Wienk, 2019 ). Likewise, more PhD graduates in the UK pursue non-academic career paths (Hancock, 2023 ; McAlpine et al., 2013 ). Regardless of the national differences, a decline in tenured academic positions and increased use of academics on a contingent contract basis is a common trend in countries with developed research systems that need further investigation.

In terms of aspiration, a survey in Australia shows that nearly two-thirds of PhD students in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) want to find a job in an industry or the public sector; in contrast, only one-third of PhD students in Social Sciences indicate their intention to look for work outside academia (McCarthy & Wienk, 2019 ). Top employers of PhD graduates are Banking and Finance, Information Technology, Engineering, Energy and Mining, Medical and Pharmaceutical sectors (McCarthy & Wienk, 2019 ), which look for STEM experts rather than social scientists. Within academia in a broader context, PhD graduates in Social Sciences in OECD countries are less likely to have full-time research fellowship opportunities, meaning fewer opportunities leading to secure employment (Auriol, 2010 ). UK PhD graduates in Social Sciences find more opportunities in non-research positions than their counterparts in STEM (Hancock, 2023 ). These findings suggest that career opportunities for PhD graduates in Social Sciences are limited both inside and outside academia.

Despite the large body of literature underscoring job security issues, little is known about how PhD graduates in Social Sciences navigate their career pathways in such a gloomy employment landscape. Addressing this gap, this study explores the stories of PhD graduates in Social Sciences to examine how they consider career options and make decisions from the beginning of their candidature until up to 5 years after graduation. The next section will present the literature that casts light on various career pathways available for PhD graduates in Australia. It is then followed by discussions about the agency of PhD graduates in navigating their career progression.

Common career pathways for PhD graduates

Inside academia.

In Australia, a PhD graduate can follow two main academic career routes: the lecturer pathway (teaching and research positions) and the postdoctoral pathway (research-only positions) (Rogers & Swain, 2022 ). Both routes have equivalent academic titles, which are ranked from levels A to E. Table 1 shows the titles used in most Australian universities.

The postdoctoral pathway, more common amongst those in STEM, especially in the biomedical sciences, is research-focused and often starts with a research assistant position (level A). PhD graduates in Social Sciences and Humanities tend to take the teaching and research pathway, which normally starts with teaching associate positions (level A). For both pathways, academic positions that offer continuing employment often start at level B.

The above two pathways are not distinctive routes. In fact, it is common to find PhD graduates switching between precarious teaching and research positions with no permanent employment opportunities entailed (Menard & Shinton, 2022 ; Spina et al., 2022 ). Alarmingly, there is an increase in the number of teaching-only staff, considered “second class”, accounting for around 80% of the casual academic workforce because they are loaded with heavy teaching and do not often have opportunities, time, and support to conduct research (Bennett et al., 2018 , p. 282). Without strong track records in research, they are unlikely to be offered a long-term employment contract (Rogers & Swain, 2022 ). The time taken to obtain one can extend to 10 years or more after the completion of doctoral study (Nadolny & Ryan, 2015 ).

Outside academia

The employment landscape for PhD graduates outside academia has become more and more promising. The rise of knowledge-based economies has promoted collaboration between academia and industry and made available career options outside of academia to PhD graduates (Hancock, 2023 ; Priestley et al., 2015 ). Although people may be optimistic about career prospects outside of academia (Waaijer, 2017 ), there are certain challenges involving adapting to the requirements of industries. Research indicates that PhD graduates often find it difficult to transition from Higher Education to other sectors because of their lack of industrial experience, the mismatch between the job market’s demand and their skill sets (Jackson & Michelson, 2016 ) or their lack of skills to sell themselves in the market (Boulos, 2016 ). Further, industry leaders tend to show reluctance to hire PhD holders due to their lack of understanding about the potential and values of these graduates for their organisations (Couston & Pignatel, 2018 ). To succeed outside of academia, PhD graduates, especially those in Social Sciences and Humanities, are recommended to equip themselves with generic and transferable skills at the doctoral level (Guerin, 2020 ; Jackson & Michelson, 2016 ; Pham, 2023 ) or enterprise skills (Lean, 2012 ). There are also recommendations for providing coursework to expand their skill sets (Denicolo, 2003 ) and substantial resources for them to develop their profiles (Waaijer, 2017 ).

The above recommendations come from a deficit frame, which views PhD graduates as lacking the required skills to be successful outside academia. It also places a strong emphasis on the responsibilities of individual PhD graduates while overlooking the systemic problem: the neoliberalisation of higher education (Warren, 2017 ). On the one hand, neoliberalism with its technocratic rationalities drives the process of responsibilising graduates for their employment outcomes (Hooley et al., 2023 ; Reid & Kelestyn, 2022 ; Sultana, 2022 ). On the other hand, it creates competitive and exploitative working conditions in higher education (Guerin, 2020 ; Khosa et al., 2023 , March 23) As a result of neoliberal governance, universities have to adopt corporate management models requiring increased numbers of flexible workers, which accounts for casualisation of the academic workforce and associated job security issues (Warren, 2017 ). Moreover, the neoliberal funding mechanism has turned universities into exploitative employers by gaining profit from academics’ under-paid work (Bates, 2021 ).

Following the above line of logic, it makes sense for PhD graduates to leave academia with its poor working conditions and embark on industry-based careers. Nevertheless, a majority of PhD students and graduates in Social Sciences and Humanities want to pursue an academic career, and indicate hope to obtain a permanent academic position (McCarthy & Wienk, 2019 ; Suomi et al., 2020 ). These people are portrayed as victims of cruel optimism (Burford, 2018 ; Guerin, 2020 ). Specifically, PhD graduates in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences are reported to hold false hope of obtaining a permanent academic appointment, and be pushed out of academia “by disappointment and inability to remain employed in the sector, rather than being pulled out to better work or lifestyle opportunities” (Guerin, 2020 , p. 311). This body of research clearly overlooks PhD graduates’ agentic roles in responding to institutional structures.

- PhD graduate agency

There is research acknowledging the role of both individual agency and institutional structures in shaping PhD graduates’ career pathways (Campbell & O’Meara, 2014 ; O’Meara et al., 2014 ). While institutions provide career frameworks, comparable to a “road map”, outlining entry and advancement milestones, individuals have agency in navigating their involvement with this “road map” (Dany et al., 2011 ; Garbe & Duberley, 2021 ). How individuals navigate their career pathways depends on their interpretation of institutional “career scripts”, which are defined as “collective interpretive schemes” that “represent steps of commonly successful careers in a certain institutional setting” (Laudel et al., 2019 , p. 955).

It is important to note that existing research on academic agency mainly drew on the experiences of faculty members who have more or less stable academic positions. There are only a handful of studies discussing the agency of newly graduated PhD holders in managing their careers. For example, Pham et al. ( 2023 ) found that international PhD graduates in the Australian context display their agency through drawing on their strengths and multiple identities to obtain employment, and navigating visa requirements. Examining PhD graduates in STEM in the USA, O’Meara et al. ( 2014 ) claim that PhD graduates can exercise agency by observing the academic job market and understanding the nature of academic careers. Drawing on the same data set, Campbell and O’Meara ( 2014 ) suggest that PhD graduates’ agency can manifest through taking strategic actions to “overcome systemic challenges in order to pursue professional goals” (p. 53). Nevertheless, the question of how PhD graduates in Social Sciences exercise their agency in navigating their career pathways has not been investigated in-depth. By addressing this question, our research can offer sophisticated insights that have implications for enhancing the employment experience of PhD graduates in Social Sciences across individual, institutional, and socio-political levels.

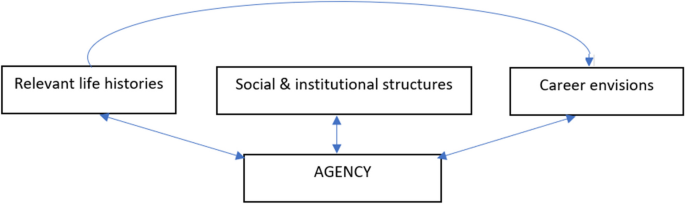

An ecological perspective of agency

In this study, we adopt an ecological perspective of agency, which highlights the interplay between individual capacities and environmental conditions (Priestley et al., 2015 ). On the one hand, this perspective recognises individual ability to make intentional choices, initiate actions, and exert control over oneself and the environment (Goller & Harteis, 2017 ). On the other hand, it emphasises how one’s ability to act with agency is afforded by the ecological system within which one operates (Priestley et al., 2015 ). For example, an academic’s agency is not only facilitated or constrained by socio-political structures and institutional conditions (McAlpine, 2012 ; Thomas, 2014 ), but also by their personal histories, and ability to envision different futures (Tao & Gao, 2021 ). Therefore, to understand PhD graduates’ agency, it is important to take into account their life histories, their career envisions as well as the social structures within which they operate. By exploring not only the social dimension of agency, but also the personal and temporal dimension of agency, this ecological approach can shed light on the multifaceted aspects that shape individuals’ agency in the context of PhD graduate employment. This approach to agency is summarised in the following diagram (Fig. 1 ):

An ecological perspective on agency (adapted from Priestley et al., 2015 )

Research methods

Study design and participants.

Our research adopted a qualitative multiple-case study design using semi-structured interviews to explore the employment experiences of PhD graduates in Social Sciences. We interviewed 23 PhD holders who graduated from five Australian universities within 5 years before the interviews. Twenty-one out of 23 participants were from Group of Eight, which are Australia’s leading research-intensive universities. The participants graduated between 2016 and 2021 and aged between 27 and 70. Their research fields cover sociology, education and linguistics. Ethical approval was obtained from Monash University (project ID: 22980).

The interviews, which were conducted in October 2021, focused on their employment experiences and career decisions made before, during and after completion of the PhD. Adopting a semi-structured interviewing approach, we treated each interview as a conversation, giving freedom to the participants to recount their experiences. For example, at the beginning of the interview, we said “please treat me as a friend whom you haven’t seen for a long time. I would love to hear your employment experiences, including before the start of your PhD, during your candidature, and your current position.” The participants would then start telling their stories. Occasionally, where relevant, we would ask them questions, clarifying particular details and aiming to understand why they make particular career decisions.

Analysis approach

Our data analysis comprises two main stages. The first stage involves documenting employment trajectories of each participant while the second stage involves analysis of selective stories representing each employment trajectory. Based on their employment trajectories, we grouped our participants into the following four categories: (1) those who remained in academia and had long-term contracts (1 year or more); (2) who remained in academia and had precarious positions; (3) who moved out of academia; (4) who moved out, and returned to academia. Demographic features of each group provided participants in each category are provided in Table 2 :

Although it is tempting to draw conclusions about the association between the demographic features of the group and their employment trajectory, we refrain from doing so due to the small sample size. Instead of reducing our data into numbers, we would like to capture the richness of stories shared by our participants. Though each story is unique in its own way, a common feature emerging among all stories is the participants’ agency in navigating their career pathways.

In this paper, we focus on stories told by four participants who represent four different career pathways. Their stories are chosen not because they are typical of demographic features listed in Table 2 . We also do not aim to choose narratives to represent the wide variety of different disciplines within Social Sciences. Instead, we chose these stories because they are the best examples of how PhD graduates can act with agency in navigating each career pathway.

Narrative analysis

Narrative theories have been widely adopted in career development studies, which explore career barriers, adaptability, and decision-making process (Lent, 2016 ; Meijers & Lengelle, 2012 ; Rossier et al., 2021 ). As Rossier et al. ( 2021 ) point out, stories allow career counsellors and researchers to understand the dynamic complexity of how individuals navigate moments of vulnerability in their career journeys. Such understanding allows the promotion of individuals’ self-directedness, enabling them to mitigate barriers, cultivate resilience, and foster change (Rossier et al., 2021 ). Our paper extends this line of research by adopting a narrative approach to examine how PhD graduates navigate the uncertainties of the academic labour market.

We examine each story as a whole as opposed to thematic analysis in which stories are fragmented into thematic categories (Wells, 2011 ). In our view, a story is not a mere representation of what happens, but rather it is constructed in the process of telling and it is told for social purposes (Ta, 2022 ; Ta & Filipi, 2020 ). The construction of stories in narrative research starts at the interview stage: interview questions not only shape the scope of the story to be told, but also influence the development of the story (Stokoe & Edwards, 2006 ). Stories will then continue to be re-constructed through interpretation and analysis. Acknowledging the constructive nature of telling and re-telling stories, we do not aim to provide an objective account of reality. Instead, we selectively analyse details that help us understand how participants’ agency interplays with other personal and social factors to shape their career pathways.

When analysing stories, we also look at participants’ construction of identity because identity, agency and storytelling have a close-knit relationship (Bamberg et al., 2011 ; Holland & Lachicotte, 2007 ). Through telling stories about themselves, “people tell others who they are, but even more important, they tell themselves who they are, and then try to act as though they are who they say they are” (Holland & Lachicotte, 2007 , p. 3). In other words, people’s stories about themselves play a role in shaping how they act in certain circumstances (Sfard & Prusak, 2005 ). Not only participants’ stories about who they are now, but also stories about who they want to become in the future can shape people’s present actions (Sfard & Prusak, 2005 ). This perspective on storytelling aligns with the ecological approach discussed above, highlighting the interplay between agency and personal histories, future career envisions.

Staying in academia with a long-term contract

Introduction to mary.

Mary (pseudonym) who completed her doctoral study in 2019 in her late 50s. Prior to her PhD, she was in and out of academia for about 25 years, serving as a sessional staff at a number of universities in Victoria. She also has solid experience in the corporate sector and ran a consultancy business in learning and development for 10 years. Just before the submission of her doctoral thesis, she was offered to work as a full-time research fellow and a deputy director of a centre providing free career consultancy and training for refugees.

An advocate of a good cause

Mary’s career story originated from her years of volunteer work involving supporting refugees. This experience provided her with insights into refugees’ employment issues. Therefore, she wanted to support refugees in career adaptability and decided to do a PhD study in this area. As she told us, her main motivation for her PhD research was to “fill the literature gap and a gap in the sector”. With this claim, Mary displays an image of a passionate scholar who was responding to the call of the industry and the knowledge gap. To realise her aspiration, she strategically recruited supervisors who worked in the field of migration and were able to support her good cause. By making meaningful choices about her research field, and strategically selecting supervisors, Mary displayed her agency in managing the direction of her career pathway.

An independent thinker establishing a niche field

During her PhD candidature, Mary saw herself as building a niche research area, which placed her in a unique position allowing her to function as a bridge between academia and the refugee sector. Besides working on the doctoral thesis, she accumulated extra assets to make her stand out in the job market. For example, she gained substantial industry experience by engaging in voluntary work to support refugees. Moreover, to build up her research experience, she worked as a lead research assistant in four research projects related to refugees’ employment. In this role, she co-wrote grant applications with her supervisors, which in her opinion was an important skill set, giving her an advantage in applying for research jobs.

A versatile leader with a vision

Unlike many PhD candidates struggling to find an academic position, Mary actively shaped her own career pathway and created her own job. Toward the end of her PhD candidature, Mary, together with her ex-supervisor, submitted to his university a proposal to set up a centre for supporting refugees’ employment. This proposal was built around her PhD and other research projects that she and her supervisor had been doing. To manage the centre, she drew on her previous experience running a consultancy business and working for the corporate sector. She saw herself as a multi-tasker with “varied work experience” and “lots of strings” to her bow, which made her a perfect fit for the job. However, she noted that what she is doing is not about creating a job, but instead “it’s about building a reputation, it’s about building impact.” In summary, she positioned herself as a leader with a vision and motivation for creating something bigger than mere employment for herself.

The interplay between agency, personal histories, career envisions and institutional factors

Mary portrayed herself as a highly capable, multi-tasker leader who had an ethical commitment to pay back to the research participants and a vision to create social impacts. Her unique career pathway was not only shaped by her strong agency, her mature age, her rich industry and research experience, her well-articulated career visions, but also influenced by institutional factors, particularly her ex-supervisor and his university. As a senior academic in a leadership position, he supported her in proposing the establishment of the centre. Additionally, she also received strong support from the university with a tradition of running humanitarian centres: it accepted their proposal, created favourable conditions for them to run the centre, and offered her a research fellow position. However, it is noted that these favourable conditions did not come on their own, but Mary played a significant role in creating them: she made serious investigations when choosing an institution and she interviewed several potential supervisors before making a decision. She also deliberately built both industry and research experiences that aligned with her career goal. As a result, she did not struggle to secure a position, but proactively created her own position as the deputy director of a university-based career clinic for refugees even before the completion of her PhD. In short, her agency was a prominent factor that shaped her career pathway.

Staying in academia with precarious positions

Introduction to kate.

Kate (pseudonym), a female domestic graduate in her 40s, is a typical example of a PhD graduate who remained in academia yet struggled to obtain a secure position. Prior to her PhD, she worked as a schoolteacher and was involved in a government project to implement e-learning in schools. She remained in these jobs while enrolling in the PhD program part-time. In the latter half of her PhD candidature, she started to work as a teaching associate at her university. Upon completion of her PhD, she mainly worked as a sessional staff at the same university for over 4 years. At the point of the interview, she got a 5-month contract as an education-focused lecturer at another university and was still looking for a long-term position.

An educator passionate about both research and teaching

Kate’s enrolment in the PhD program came out of her “fascination and respect for higher learning”. She loved “the intellectual enrichment and cultural enrichment of university life”, which she found stimulating. In terms of career considerations, Kate recalled that she had an “internal calling” of conducting research and teaching at university during her PhD candidature. At some point, she expressed her preference of becoming an academic to a professional job, and the “secret desire” to gain “recognition from academia”. However, Kate maintained both jobs as a schoolteacher and a university tutor even after she graduated. Her diverse interests led to her uncertainty about her career pathway: “I get torn between the two pathways [being a teacher and a researcher].” After the completion of her PhD program, she decided to negotiate with her school to have a 6-month agreement after being offered a 1-year contract “just to have a little bit of security before deciding to take the leap into pursuing academia”.

An active job seeker on a million contracts

Kate described herself as very good at networking, which led to several casual contracts after graduation. Her efforts of working hard in her casual roles helped her gain the trust of employers who could provide her with more opportunities. Desperate for a secure position, she actively applied for more stable jobs. She strategically chose to apply for jobs with a similar title or similar role and jobs with employers she had experience working with. In addition, she also tried to make her presence stronger by being around the campus, finding out about and participating in university events, getting herself invited to meetings, and taking advantage of mentoring opportunities offered by the university. Kate displayed her agency in managing her career pathway by making conscious choices regarding job application, networking, and increasing her presence in the university community.

An academic seeing herself as “not an academic yet”

Although Kate worked as a casual academic for several years, she did not “feel like a real academic yet”. She did not feel that she was part of the academic community in her workplace, seeing a clear boundary between those inside and outside the “full-time staff club”. In her words, sessional staff are “not fully embedded in that environment and easily dispensable.” In this claim, Kate highlighted the low status of sessional teacher and implied her aspiration to become an insider of the full-time staff club. To actualise her aspiration, Kate saw the necessity of building a research narrative to showcase her uniqueness through weaving various research experiences she has accumulated into a coherent story. As she believed a strong research narrative is essential for selling oneself in the academic job market, she worked hard to craft one. This story indicates her strong agency in identifying key success factors and working hard to achieve success.

The interplay between agency, personal histories, career envisions, and institutional factors

Kate’s story represents the majority of our participants who worked hard and played agentic roles in navigating their career roadblocks, but still had not been able to obtain a stable academic position. To prepare for an academic career, she accumulated extensive teaching experiences, and built strong connections to academic communities. The missing element, as Kate identified, was a lack of a strong research narrative. Her limitation in research was partly due to the fact that at the early stage of her PhD candidature, she had to take jobs with stable incomes to pay her mortgage and bring up a child as a single mother. As a child grew up, when she felt she could take risks, leaving a stable position as a secondary teacher to engage in various precarious academic jobs. Although her personal circumstances and the institutional requirement regarding research performance have limited her choices at certain points of time, her key career decisions were driven by her aspirations of becoming an academic.

Moving out of academia

Introduction to noriko.

Noriko (pseudonym), a PhD graduate in her late 20s is a typical example of those who moved out of academia and did not intend to return. She started doing her PhD study at a very young age. After her undergraduate degree, she worked at an Australian primary school for a year, and did a Master’s study, which was immediately followed by a PhD study. While doing her Masters’ and PhD studies, she had multiple part-time jobs including teaching at primary schools and tutoring university students. She was actively looking for opportunities to stay in academia, but settled on a full-time professional job as a policy officer at the Department of Education 1 year after her PhD graduation.

A struggling casual teacher with a passion for studying

Noriko experienced multiple struggles when she worked as a casual relief teacher at a primary school. Therefore, she wanted a career change. As a first step, she decided to do a Master’s study, and then a PhD study focusing on relief teaching. She also attributed her decision to her love for studying, which is a common quality that academics tend to share. To fund her PhD research, she actively searched for scholarships, which shows her agentic role in finding opportunities to support her career change.

A strategist building stepping-stones for an academic career

Noriko had multiple casual teaching opportunities during her PhD candidature. Since the middle of her Master’s study, she had already actively searched for opportunities to work as a casual teaching associate, teaching university students. Her strategy was “mass emailing”: she emailed every unit coordinator whom she did not know personally, expressing her interest in teaching their units, which successfully resulted in job offers. In accounting for multiple job opportunities, she highlighted the significance of networking, getting to know people in the faculty, appearing to be competent, and showing initiative when communicating with them. In her own words, she was “open to any opportunities that might arise”, and “strategically took on jobs” that would make her resume look good. This effort led to an offer of a 6-month contract position as a unit coordinator, who is in charge of coordinating teaching staff who teach a subject. In this story, Noriko displayed her agency in creating stepping-stones on the academic pathway, thereby to some extent realising her goal of becoming an academic.

A pragmatist prioritising job security over becoming an academic

Despite the desire to become an academic at the beginning of her PhD candidature, Noriko later realised that it was not realistic to pursue the career. She was also concerned that the pressure in relation to research outputs would drive her life out of balance. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic experience made her prioritise job security over her ambition to become an academic. When she graduated in 2021, a year after the start of the pandemic, she started looking for a more secure job outside academia. She applied for a position as a policy officer at the Department of Education and performed very well in the interview. She proudly said: “I was really good at showcasing my skills that were translatable to the position […], I remember telling the interviewers, like, I’m really good at synthesising really large volumes of information”. Apparently, Noriko’s decision to leave academia is a rational choice; it was a response to the insecure working conditions; and it was facilitated by her confidence in the transferability of her skills to the non-academic position.

When Noriko received the job offer, she felt like she “finally achieved the goal, which was to get a full-time job”. However, for her, it was also “a bittersweet moment” because it was not an academic job. Despite some “bitterness”, she confessed that she did not want to come back to academia unless “there is, by some miracle, a permanent full-time position”. Job security was the key consideration in her decision of whether or not she would return to academia.

Noriko’s stories represent a proportion of PhD graduates who had a strong passion for chosen research topics, and acted with agency in pursuing an academic career, but decided to leave academia for job security reasons. In comparison to others who left academia after a number of years, Noriko decided to leave within a couple of months after graduation. This early decision might be attributed to her employment experience as a relief teacher and the COVID-19. While the life of a relief teacher taught her to appreciate stability, the strike of COVID-19 on higher education made her realise how insecure an academic career can be (Hadjisolomou et al., 2022 ). Her aspiration of becoming an academic became weak and having a stable job became the ultimate goal. However, her decision to leave academia should not be seen as a failure. Rather it is a story of success in which Noriko demonstrated her agency in prioritising what was important to her and taking actions that lead to the achievement of her goal to get a full-time job in an area where her experiences and skills are valued.

Moving out and returning to academia

Introduction to jack.

Jack (pseudonym), a PhD graduate in late 20s, represents those whose career pathways involve multiple turns and twists. After his first degree, he worked in public service in the Australian government for 2 years, before pursuing his PhD degree in Applied Linguistics. During his PhD candidature, he had multiple precarious teaching, marking and research jobs. After the submission of his PhD thesis, he started to look for a lecturer or postdoc position both inside and outside of Australia. However, after a few unsuccessful attempts, he decided to return to the public sector. Nevertheless, a couple of months later, he again resigned from the government job to work as a research officer at a university. At the time of the interview, 6 months after the conferral of his PhD, he was offered a fixed-term postdoctoral position in New Zealand.

An idealist following a dream

Jack developed an interest in a research degree when he was doing a research component for his Honour degree. He envisaged an ideal image of a PhD student and desired to become a research student. This outlook played a critical role in his later decision to pursue an academic career; however, after his BA Honour degree, he decided to take a job in public service for financial reasons. In this position, Jack always felt “unfulfilled”. After meeting his partner who was doing a PhD degree, his dream of becoming a PhD student became stronger: “When I saw what my partner’s life was like I thought, wow, it looks so nice”. Holding an idealised notion of a PhD student’s life working 9–5 in a supportive environment, Jack decided to apply for PhD scholarships. He admitted that he chose the research topic because of his personal interest without considering whether his topic choice could bring about opportunities for an academic career. His decision-making was clearly driven by his love for research and the idealistic perspective of a PhD student’s life.

A dreamer facing a reality check

Once being a PhD student, Jack’s dream to become an academic grew stronger. To pave the road for his academic career, he sought to obtain teaching and research experiences, and actively participate in multiple research communities at his university. He secured multiple precarious jobs including tutoring and marking a couple of subjects. Around the time of thesis submission, he started to look for but failed to gain a postdoc position. Despite his proactive measures in preparing for an academic career, he did not succeed in obtaining an academic position. He attributed this lack of success to his limited publications. Although he still longed for academic life, he decided to move back to the public sector working as a policy officer, for financial reasons as he acknowledged “I needed something when the scholarship money ran out” .

A persistent pursuer of an academic career

While working in the public service sector, Jack still persistently pursued his academic dream, spending his spare time on publications, thus developing his academic profile. Despite his fear of being unable to get an on-going academic job, he made a hard decision: leaving the stable job to seek career fulfilment. Here is what he told us about why he left: “If I don’t get an academic job within one year or two years, then it's kind of over for me like I won't be able to get into the area. So, I was really freaking out, I quit ”. His words show his strong desire to get back to academia and his awareness of the time pressure, which both account for his decision to return to academia. After leaving the government job, Jack actively searched for better jobs while working on publications. He looked for positions in China, the UK, and Europe and succeeded with a postdoctoral application with the Chinese government. Nevertheless, he did not go to China for various reasons including his unfamiliarity with the Chinese academic environment, and the uncertainty of getting back to Australia.

A semi-happy postdoctoral fellow

After resigning from the government position, Jack got a job as a research officer at a university. Although he found the position more exciting than the government job, he sometimes felt frustrated with the situation that he had to support other researchers when he could not be one himself. Therefore, he sent another application and succeeded in obtaining a postdoctoral fellow position in New Zealand. He was happy with the job offer except for one thing: he had to relocate to New Zealand. However, he thought moving to New Zealand was a stepping-stone for him to get back to an academic career in Australia. This decision was driven by his long-term goal of having an academic career in Australia. Despite the happy moments of having a fixed-term contract, he was still concerned about its temporary nature.

Jack was the only participant who went back and forth several times between academic and non-academic employment. Fuelled by his envision for an ideal life of an academic, he proactively participated in research communities, and searched for opportunities that can lead to an academic career, which showed his strong agency in navigating his career. Like other participants, the key barrier for him to obtain a stable academic position is the institutional requirement regarding research output. Also like others, he had to prioritise financial security at some stages; however, he did return to academia accepting a less stable position in a neighbouring country, viewing it as a ticket for his entry into a stable academic position in Australia in the future. The fact that he was a young male with no childcare responsibilities might have made it easier for him to accept certain instability in the pursuit of an academic career.

Discussions

This study explored how PhD graduates in Social Sciences navigated their careers in a tight labour market for academic positions. It unpacked the role of agency, personal histories, career envisions and institutional factors in shaping four typical career trajectories: (1) remaining in academia with long-term contracts; (2) remaining in academia with casual or short-term contracts; (3) leaving academia; and (4) leaving and returning to academia. Analysis of stories from these four career trajectories highlighted PhD graduates’ agency as the key link among various factors contributing to shaping the trajectories.

There are multiple factors accounting for why individuals remained in academia. For Mary, who remained in academia with a stable position, supportive factors include her mature age, strong agency in creating career opportunities, well-formed career vision, extensive industry experience, solid connections with the industry, and institutional support. Some of these factors are though observed in the case of Kate, who landed in a short-term contract academic position after graduation. They include her strong aspiration for an academic career, industry experiences, and academic connections, which were also present in the story of Jack, who returned to academia after some diversions. A supportive factor that other participants did not share with Jack was his status as a young male, which allowed him to accept certain instability in his pursuit of an academic career.

The main barrier in most participants’ pursuits of an academic career was regarding research output. According to Kate and Jack, the major hindrance for them to obtain an on-going academic position was their lack of strong research narratives and track records. Likewise, due to the pressures related to research output, Noriko gave up pursuing an academic career. Research output pressure is a long-existing institutional problem. In the neoliberal higher education, to compete for research funding and high ranking, universities have widely adopted recruitment and reward systems that favour academics with high research output (Bogt & Scapens, 2012 ; Douglas, 2013 ). These systems apparently disadvantage newly graduated PhD holders, prolonging the time for them to find a stable position (Nadolny & Ryan, 2015 ). Moreover, an overemphasis on research output is reported to create stress, and work-life balance issues (Culpepper et al., 2020 ; Szelényi & Denson, 2019 ), which account for an increasing rate of PhD graduates choosing non-academic careers (Feldon et al., 2023 ).

A common factor that drew our participants away from academia is financial security. For financial reasons, Kate was unable to devote her time to research and publication, and Jack had to leave academia several times to earn a living elsewhere regardless of their strong passion for research. For financial security, Noriko accepted a professional job albeit feeling sad about giving up an academic career. Job security, which is associated with the casualisation in academia in countries with developed research systems, has become a significant concern for PhD graduates, causing various well-being issues such as stress and anxiety (Van Benthem et al., 2020 ). More importantly, high casualisation can potentially de-professionalise academic work, erode academic freedom and hence make academia less attractive to PhD graduates (Kimber & Ehrich, 2015 ; Ryan et al., 2017 ).

Regardless of the above challenges, a considerable portion of our participants strongly held on to their aspiration to an academic career (16 out of 23). For some participants, their motivation was fuelled by an idealised image of academic life. However, they are not naïve victims of “cruel optimism” as portrayed in some literature (Bieber & Worley, 2006 ; Guerin, 2020 ). Instead, they were well aware of the challenges associated, knew what they would need to do to succeed, and deliberately took actions to achieve their goals. To name a few examples, Mary established a niche area where she can translate her research into practice. Kate worked on crafting a research narrative to promote her research visions. Jack explored and succeeded in obtaining opportunities overseas. Noriko knew how to sell herself to non-academic recruiters and was successful in applying her research capabilities to her professional work. In short, they displayed strong agency in responding to the challenges as well as opportunities in their career pathways: they decided what career they wanted to have, and how to achieve their career goals. Their stories all highlight the importance of agency in shaping one’s career trajectories, which is consistent with existing research (Campbell & O’Meara, 2014 ; O’Meara et al., 2014 ).

Implications for PhD students and graduates

The above findings offer practical implications for PhD students and graduates. PhD graduates should be aware that they can enact their agency in making career choices and responding to the institutional pressures proactively (Campbell & O’Meara, 2014 ; O’Meara et al., 2014 ). To make well-informed career decisions, they need to know career options both inside and outside the academic sector. If they prefer to stay in academia, it is important to be aware that passions, industry experiences, and networking are necessary, but not sufficient to obtain a tenured position in academia. Similarly, research output is an essential factor, but focussing on the number of publications only is not sufficient either. The key element seems to be the ability to construct a narrative that helps present oneself as a researcher with a strong potential to make unique contributions and create lasting impacts as narrative has been increasingly used as a tool in performance measurement in higher education (Bandola-Gill & Smith, 2022 ; Chubb & Reed, 2018 ).

Implications for PhD supervisors, universities and industry employers

Our research calls for institutional recognition of PhD students’ agency. Universities can support this by providing resources and opportunities (e.g. in the form of funding) for them to “start up” their research career (O’Meara et al., 2014 ). In addition, as people who know their students’ research fields, supervisors can act as mentors during their career building-up journey. Instead of merely focusing on the particularities of the PhD research, supervisors can invest time and effort in supporting students to form a career vision and identify competitive edges. Mentoring practices, which have been adopted in PhD programs in STEM, (Curtin et al., 2016 ; Hund et al., 2018 ), can also be offered to those in Social Sciences.

For students who do not intend to pursue an academic career, universities can support their agency by legitimising non-academic careers and integrating career development with research training (Universities Australia, 2013 ). More importantly, a shift in perspective is timely required: PhD students should be treated as highly capable individuals instead of a labour force lacking industry-relevant skills (e.g., Jackson & Michelson, 2016 ; Pham, 2023 ). Appreciating PhD students’ agency, universities can support PhD students to reach their full potential while a deficit perspective may result in a waste of resources in running skills development programmes that do not meet student needs (Moreno, 2014 ). In the same vein, with an agency-focused perspective, industry employers can appreciate the broader value of PhD graduates’ skills in enhancing the growth of their organisations (McAlpine & Inouye, 2022 ).

Policy implications

Policymakers also need to consider the agency of PhD students and graduates, treating them as valued brokers in the process of translating advanced knowledge for the benefit of the society at large (Lazurko et al., 2020 ), instead of turning them into fierce competitors for limited research funding and academic appointments (Carson et al., 2013 ; Pelletier et al., 2019 ). Under the current funding systems, and the casualisation of academic workforce, working conditions in academia have become increasingly competitive, which is associated with early career academics’ mental health issues (Culpepper et al., 2020 ; Szelényi & Denson, 2019 ). To address these issues, there are calls for increasing on-going positions (NTEU, 2020 ), strengthening support for early-career researchers (McComb et al., 2021 ), and reforming research funding policies (O’Kane, 2023 ). Taking the Australian system for example, funding increases in line with PhD completion, which accounts for a surplus supply of PhD graduates compared to the availability of academic positions (Hoang et al., 2023 , May 18). To address this issue, reducing PhD enrolments in Social sciences has been recommended as a solution (Croucher, 2016 , November 18). This recommendation may help resolve the supply–demand issue, but would lead to the shrinking of social research, which would have detrimental impacts on the society at large (Shaw, 2023 , July 25). Instead of limiting PhD enrolments, measures should be taken to promote employment of PhD graduates in the translation of social research findings into practice.

Conclusion and limitation

In this paper, we provide narrative evidence to illustrate the agency of Social Sciences PhD graduates in navigating their career pathways. By emphasising their agentic roles, we are able to identify the key institutional and personal factors that bear strong consequences on the twists and turns in their career pathways. Based on our analysis of the stories told by our participants, we offer recommendations for practice and policy. It is important to note that the stories may not be representative of all social research disciplines due to the limitation in sampling: the majority of our participants did their PhD study in linguistics and education.

Auriol, L. (2010). Careers of doctorate holders: Employment and mobility patterns. OECD Science, Technology and Industry . https://doi.org/10.1787/5kmh8phxvvf5-en

Article Google Scholar

Auriol, L., Misu, M., & Freeman, R. A. (2013). Careers of doctoral holders: Analysis of labour market and mobility indicators. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers. No. 2013/04. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k43nxgs289w-en

Chapter Google Scholar

Bamberg, M., De Fina, A., & Schiffrin, D. (2011). Discourse and identity construction. In S. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vigoles (Eds.), Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (pp. 177–199). Springer.

Bandola-Gill, J., & Smith, K. E. (2022). Governing by narratives: REF impact case studies and restrictive storytelling in performance measurement. Studies in Higher Education, 47 (9), 1857–1871. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1978965

Bates, D. (2021). Academic labor and its exploitation. Theory & Event, 24 (4), 1090–1109. https://doi.org/10.1353/tae.2021.0060

Bennett, D., Roberts, L., Ananthram, S., & Broughton, M. (2018). What is required to develop career pathways for teaching academics? Higher Education , 75 (2), 271–286. https://link.springer.com/article/ https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0138-9

Bieber, J. P., & Worley, L. K. (2006). Conceptualizing the academic life: Graduate students’ perspectives. The Journal of Higher Education, 77 (6), 1009–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2006.11778954

Bogt, H. J., & Scapens, R. W. (2012). Performance management in universities: Effects of the transition to more quantitative measurement systems. European Accounting Review, 21 (3), 451–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2012.668323

Boulos, A. (2016). The labour market relevance of PhDs: An issue for academic research and policy-makers. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (5), 901–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1147719

Buenstorf, G., Koenig, J., & Otto, A. (2023). Expansion of doctoral training and doctorate recipients’ labour market outcomes: Evidence from German register data. Studies in Higher Education, 48 (8), 1216–1242. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2188397

Burford, J. (2018). The trouble with doctoral aspiration now. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 31 (6), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1422287

Campbell, C. M., & O’Meara, K. (2014). Faculty agency: Departmental contexts that matter in faculty careers. Research in Higher Education, 55 (1), 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9303-x

Carson, L., Bartneck, C., & Voges, K. (2013). Over-competitiveness in academia: A literature review. Disruptive Science and Technology, 1 (4), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1089/dst.2013.0013