- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

What does it mean to be an American?

Sarah Song, a Visiting Scholar at the Academy in 2005–2006, is an assistant professor of law and political science at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of Justice, Gender, and the Politics of Multiculturalism (2007). She is at work on a book about immigration and citizenship in the United States.

It is often said that being an American means sharing a commitment to a set of values and ideals. 1 Writing about the relationship of ethnicity and American identity, the historian Philip Gleason put it this way:

To be or to become an American, a person did not have to be any particular national, linguistic, religious, or ethnic background. All he had to do was to commit himself to the political ideology centered on the abstract ideals of liberty, equality, and republicanism. Thus the universalist ideological character of American nationality meant that it was open to anyone who willed to become an American. 2

To take the motto of the Great Seal of the United States, E pluribus unum – "From many, one" – in this context suggests not that manyness should be melted down into one, as in Israel Zangwill's image of the melting pot, but that, as the Great Seal's sheaf of arrows suggests, there should be a coexistence of many-in-one under a unified citizenship based on shared ideals.

Of course, the story is not so simple, as Gleason himself went on to note. America's history of racial and ethnic exclusions has undercut the universalist stance; for being an American has also meant sharing a national culture, one largely defined in racial, ethnic, and religious terms. And while solidarity can be understood as "an experience of willed affiliation," some forms of American solidarity have been less inclusive than others, demanding much more than simply the desire to affiliate. 3 In this essay, I explore different ideals of civic solidarity with an eye toward what they imply for newcomers who wish to become American citizens.

Why does civic solidarity matter? First, it is integral to the pursuit of distributive justice. The institutions of the welfare state serve as redistributive mechanisms that can offset the inequalities of life chances that a capitalist economy creates, and they raise the position of the worst-off members of society to a level where they are able to participate as equal citizens. While self-interest alone may motivate people to support social insurance schemes that protect them against unpredictable circumstances, solidarity is understood to be required to support redistribution from the rich to aid the poor, including housing subsidies, income supplements, and long-term unemployment benefits. 4 The underlying idea is that people are more likely to support redistributive schemes when they trust one another, and they are more likely to trust one another when they regard others as like themselves in some meaningful sense.

Second, genuine democracy demands solidarity. If democratic activity involves not just voting, but also deliberation, then people must make an effort to listen to and understand one another. Moreover, they must be willing to moderate their claims in the hope of finding common ground on which to base political decisions. Such democratic activity cannot be realized by individuals pursuing their own interests; it requires some concern for the common good. A sense of solidarity can help foster mutual sympathy and respect, which in turn support citizens' orientation toward the common good.

Third, civic solidarity offers more inclusive alternatives to chauvinist models that often prevail in political life around the world. For example, the alternative to the Nehru-Gandhi secular definition of Indian national identity is the Hindu chauvinism of the Bharatiya Janata Party, not a cosmopolitan model of belonging. "And what in the end can defeat this chauvinism," asks Charles Taylor, "but some reinvention of India as a secular republic with which people can identify?" 5 It is not enough to articulate accounts of solidarity and belonging only at the subnational or transnational levels while ignoring senses of belonging to the political community. One might believe that people have a deep need for belonging in communities, perhaps grounded in even deeper human needs for recognition and freedom, but even those skeptical of such claims might recognize the importance of articulating more inclusive models of political community as an alternative to the racial, ethnic, or religious narratives that have permeated political life. 6 The challenge, then, is to develop a model of civic solidarity that is "thick" enough to motivate support for justice and democracy while also "thin" enough to accommodate racial, ethnic, and religious diversity.

We might look first to Habermas's idea of constitutional patriotism (Verfassungspatriotismus). The idea emerged from a particular national history, to denote attachment to the liberal democratic institutions of the postwar Federal Republic of Germany, but Habermas and others have taken it to be a generalizable vision for liberal democratic societies, as well as for supranational communities such as the European Union. On this view, what binds citizens together is their common allegiance to the ideals embodied in a shared political culture. The only "common denominator for a constitutional patriotism" is that "every citizen be socialized into a common political culture." 7

Habermas points to the United States as a leading example of a multicultural society where constitutional principles have taken root in a political culture without depending on "all citizens' sharing the same language or the same ethnic and cultural origins." 8 The basis of American solidarity is not any particular racial or ethnic identity or religious beliefs, but universal moral ideals embodied in American political culture and set forth in such seminal texts as the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, and Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. Based on a minimal commonality of shared ideals, constitutional patriotism is attractive for the agnosticism toward particular moral and religious outlooks and ethnocultural identities to which it aspires.

What does constitutional patriotism suggest for the sort of reception immigrants should receive? There has been a general shift in Western Europe and North America in the standards governing access to citizenship from cultural markers to values, and this is a development that constitutional patriots would applaud. In the United States those seeking to become citizens must demonstrate basic knowledge of U.S. government and history. A newly revised U.S. citizenship test was instituted in October 2008 with the hope that it will serve, in the words of the chief of the Office of Citizenship, Alfonso Aguilar, as "an instrument to promote civic learning and patriotism." 9 The revised test attempts to move away from civics trivia to emphasize political ideas and concepts. (There is still a fair amount of trivia: "How many amendments does the Constitution have?" "What is the capital of your state?") The new test asks more open-ended questions about government powers and political concepts: "What does the judicial branch do?" "What stops one branch of government from becoming too powerful?" "What is freedom of religion?" "What is the 'rule of law'?" 10

Constitutional patriots would endorse this focus on values and principles. In Habermas's view, legal principles are anchored in the "political culture," which he suggests is separable from "ethical-cultural" forms of life. Acknowledging that in many countries the "ethical-cultural" form of life of the majority is "fused" with the "political culture," he argues that the "level of the shared political culture must be uncoupled from the level of subcultures and their prepolitical identities." 11 All that should be expected of immigrants is that they embrace the constitutional principles as interpreted by the political culture, not that they necessarily embrace the majority's ethical-cultural forms.

Yet language is a key aspect of "ethical-cultural" forms of life, shaping people's worldviews and experiences. It is through language that individuals become who they are. Since a political community must conduct its affairs in at least one language, the ethical-cultural and political cannot be completely "uncoupled." As theorists of multiculturalism have stressed, complete separation of state and particularistic identities is impossible; government decisions about the language of public institutions, public holidays, and state symbols unavoidably involve recognizing and supporting particular ethnic and religious groups over others. 12 In the United States, English language ability has been a statutory qualification for naturalization since 1906, originally as a requirement of oral ability and later as a requirement of English literacy. Indeed, support for the principles of the Constitution has been interpreted as requiring English literacy. 13 The language requirement might be justified as a practical matter (we need some language to be the common language of schools, government, and the workplace, so why not the language of the majority?), but for a great many citizens, the language requirement is also viewed as a key marker of national identity. The continuing centrality of language in naturalization policy prevents us from saying that what it means to be an American is purely a matter of shared values.

Another misconception about constitutional patriotism is that it is necessarily more inclusive of newcomers than cultural nationalist models of solidarity. Its inclusiveness depends on which principles are held up as the polity's shared principles, and its normative substance depends on and must be evaluated in light of a background theory of justice, freedom, or democracy; it does not by itself provide such a theory. Consider ideological requirements for naturalization in U.S. history. The first naturalization law of 1790 required nothing more than an oath to support the U.S. Constitution. The second naturalization act added two ideological elements: the renunciation of titles or orders of nobility and the requirement that one be found to have "behaved as a man . . . attached to the principles of the constitution of the United States." 14 This attachment requirement was revised in 1940 from a behavioral qualification to a personal attribute, but this did not help clarify what attachment to constitutional principles requires. 15 Not surprisingly, the "attachment to constitutional principles" requirement has been interpreted as requiring a belief in representative government, federalism, separation of powers, and constitutionally guaranteed individual rights. It has also been interpreted as disqualifying anarchists, polygamists, and conscientious objectors for citizenship. In 1950, support for communism was added to the list of grounds for disqualification from naturalization – as well as grounds for exclusion and deportation. 16 The 1990 Immigration Act retained the McCarthy-era ideological qualifications for naturalization; current law disqualifies those who advocate or affiliate with an organization that advocates communism or opposition to all organized government. 17 Patriotism, like nationalism, is capable of excess and pathology, as evidenced by loyalty oaths and campaigns against "un-American" activities.

In contrast to constitutional patriots, liberal nationalists acknowledge that states cannot be culturally neutral even if they tried. States cannot avoid coercing citizens into preserving a national culture of some kind because state institutions and laws define a political culture, which in turn shapes the range of customs and practices of daily life that constitute a national culture. David Miller, a leading theorist of liberal nationalism, defines national identity according to the following elements: a shared belief among a group of individuals that they belong together, historical continuity stretching across generations, connection to a particular territory, and a shared set of characteristics constituting a national culture. 18 It is not enough to share a common identity rooted in a shared history or a shared territory; a shared national culture is a necessary feature of national identity. I share a national culture with someone, even if we never meet, if each of us has been initiated into the traditions and customs of a national culture.

What sort of content makes up a national culture? Miller says more about what a national culture does not entail. It need not be based on biological descent. Even if nationalist doctrines have historically been based on notions of biological descent and race, Miller emphasizes that sharing a national culture is, in principle, compatible with people belonging to a diversity of racial and ethnic groups. In addition, every member need not have been born in the homeland. Thus, "immigration need not pose problems, provided only that the immigrants come to share a common national identity, to which they may contribute their own distinctive ingredients." 19

Liberal nationalists focus on the idea of culture, as opposed to ethnicity or descent, in order to reconcile nationalism with liberalism. Thicker than constitutional patriotism, liberal nationalism, Miller maintains, is thinner than ethnic models of belonging. Both nationality and ethnicity have cultural components, but what is said to distinguish "civic" nations from "ethnic" nations is that the latter are exclusionary and closed on grounds of biological descent; the former are, in principle, open to anyone willing to adopt the national culture. 20

Yet the civic-ethnic distinction is not so clear-cut in practice. Every nation has an "ethnic core." As Anthony Smith observes

[M]odern "civic" nations have not in practice really transcended ethnicity or ethnic sentiments. This is a Western mirage, reality-as-wish; closer examination always reveals the ethnic core of civic nations, in practice, even in immigrant societies with their early pioneering and dominant (English and Spanish) culture in America, Australia, or Argentina, a culture that provided the myths and language of the would-be nation. 21

This blurring of the civic-ethnic distinction is reflected throughout U.S. history with the national culture often defined in ethnic, racial, and religious terms. 22

Why, then, if all national cultures have ethnic cores, should those outside this core embrace the national culture? Miller acknowledges that national cultures have typically been formed around the ethnic group that is dominant in a particular territory and therefore bear "the hallmarks of that group: language, religion, cultural identity." Muslim identity in contemporary Britain becomes politicized when British national identity is conceived as containing "an Anglo-Saxon bias which discriminates against Muslims (and other ethnic minorities)." But he maintains that his idea of nationality can be made "democratic in so far as it insists that everyone should take part in this debate [about what constitutes the national identity] on an equal footing, and sees the formal arenas of politics as the main (though not the only) place where the debate occurs." 23

The major difficulty here is that national cultures are not typically the product of collective deliberation in which all have the opportunity to participate. The challenge is to ensure that historically marginalized groups, as well as new groups of immigrants, have genuine opportunities to contribute "on an equal footing" to shaping the national culture. Without such opportunities, liberal nationalism collapses into conservative nationalism of the kind defended by Samuel Huntington. He calls for immigrants to assimilate into America's "Anglo- Protestant culture." Like Miller, Huntington views ideology as "a weak glue to hold together people otherwise lacking in racial, ethnic, or cultural sources of community," and he rejects race and ethnicity as constituent elements of national identity. 24 Instead, he calls on Americans of all races and ethnicities to "reinvigorate their core culture." Yet his "cultural" vision of America is pervaded by ethnic and religious elements: it is not only of a country "committed to the principles of the Creed," but also of "a deeply religious and primarily Christian country, encompassing several religious minorities, adhering to Anglo- Protestant values, speaking English, maintaining its European cultural heritage." 25 That the cultural core of the United States is the culture of its historically dominant groups is a point that Huntington unabashedly accepts.

Cultural nationalist visions of solidarity would lend support to immigration and immigrant policies that give weight to linguistic and ethnic preferences and impose special requirements on individuals from groups deemed to be outside the nation's "core culture." One example is the practice in postwar Germany of giving priority in immigration and naturalization policy to ethnic Germans; they were the only foreign nationals who were accepted as permanent residents set on the path toward citizenship. They were treated not as immigrants but "resettlers" (Aussiedler) who acted on their constitutional right to return to their country of origin. In contrast, non-ethnically German guestworkers (Gastarbeiter) were designated as "aliens" (Auslander) under the 1965 German Alien Law and excluded from German citizenship. 26 Another example is the Japanese naturalization policy that, until the late 1980s, required naturalized citizens to adopt a Japanese family name. The language requirement in contemporary naturalization policies in the West is the leading remaining example of a cultural nationalist integration policy; it reflects not only a concern with the economic and political integration of immigrants but also a nationalist concern with preserving a distinctive national culture.

Constitutional patriotism and liberal nationalism are accounts of civic solidarity that deal with what one might call first-level diversity. Individuals have different group identities and hold divergent moral and religious outlooks, yet they are expected to share the same idea of what it means to be American: either patriots committed to the same set of ideals or co-nationals sharing the relevant cultural attributes. Charles Taylor suggests an alternative approach, the idea of "deep diversity." Rather than trying to fix some minimal content as the basis of solidarity, Taylor acknowledges not only the fact of a diversity of group identities and outlooks (first-level diversity), but also the fact of a diversity of ways of belonging to the political community (second-level or deep diversity). Taylor introduces the idea of deep diversity in the context of discussing what it means to be Canadian:

Someone of, say, Italian extraction in Toronto or Ukrainian extraction in Edmonton might indeed feel Canadian as a bearer of individual rights in a multicultural mosaic. . . . But this person might nevertheless accept that a Québécois or a Cree or a Déné might belong in a very different way, that these persons were Canadian through being members of their national communities. Reciprocally, the Québécois, Cree, or Déné would accept the perfect legitimacy of the "mosaic" identity.

Civic solidarity or political identity is not "defined according to a concrete content," but, rather, "by the fact that everybody is attached to that identity in his or her own fashion, that everybody wants to continue that history and proposes to make that community progress." 27 What leads people to support second-level diversity is both the desire to be a member of the political community and the recognition of disagreement about what it means to be a member. In our world, membership in a political community provides goods we cannot do without; this, above all, may be the source of our desire for political community.

Even though Taylor contrasts Canada with the United States, accepting the myth of America as a nation of immigrants, the United States also has a need for acknowledgment of diverse modes of belonging based on the distinctive histories of different groups. Native Americans, African Americans, Irish Americans, Vietnamese Americans, and Mexican Americans: across these communities of people, we can find not only distinctive group identities, but also distinctive ways of belonging to the political community.

Deep diversity is not a recapitulation of the idea of cultural pluralism first developed in the United States by Horace Kallen, who argued for assimilation "in matters economic and political" and preservation of differences "in cultural consciousness." 28 In Kallen's view, hyphenated Americans lived their spiritual lives in private, on the left side of the hyphen, while being culturally anonymous on the right side of the hyphen. The ethnic-political distinction maps onto a private-public dichotomy; the two spheres are to be kept separate, such that Irish Americans, for example, are culturally Irish and politically American. In contrast, the idea of deep diversity recognizes that Irish Americans are culturally Irish American and politically Irish American. As Michael Walzer put it in his discussion of American identity almost twenty years ago, the culture of hyphenated Americans has been shaped by American culture, and their politics is significantly ethnic in style and substance. 29 The idea of deep or second-level diversity is not just about immigrant ethnics, which is the focus of both Kallen's and Walzer's analyses, but also racial minorities, who, based on their distinctive experiences of exclusion and struggles toward inclusion, have distinctive ways of belonging to America.

While attractive for its inclusiveness, the deep diversity model may be too thin a basis for civic solidarity in a democratic society. Can there be civic solidarity without citizens already sharing a set of values or a culture in the first place? In writing elsewhere about how different groups within democracy might "share identity space," Taylor himself suggests that the "basic principles of republican constitutions – democracy itself and human rights, among them" constitute a "non-negotiable" minimum. Yet, what distinguishes Taylor's deep diversity model of solidarity from Habermas's constitutional patriotism is the recognition that "historic identities cannot be just abstracted from." The minimal commonality of shared principles is "accompanied by a recognition that these principles can be realized in a number of different ways, and can never be applied neutrally without some confronting of the substantive religious ethnic-cultural differences in societies." 30 And in contrast to liberal nationalism, deep diversity does not aim at specifying a common national culture that must be shared by all. What matters is not so much the content of solidarity, but the ethos generated by making the effort at mutual understanding and respect.

Canada's approach to the integration of immigrants may be the closest thing there is to "deep diversity." Canadian naturalization policy is not so different from that of the United States: a short required residency period, relatively low application fees, a test of history and civics knowledge, and a language exam. 31 Where the United States and Canada diverge is in their public commitment to diversity. Through its official multiculturalism policies, Canada expresses a commitment to the value of diversity among immigrant communities through funding for ethnic associations and supporting heritage language schools. 32 Constitutional patriots and liberal nationalists say that immigrant integration should be a two-way process, that immigrants should shape the host society's dominant culture just as they are shaped by it. Multicultural accommodations actually provide the conditions under which immigrant integration might genuinely become a two-way process. Such policies send a strong message that immigrants are a welcome part of the political community and should play an active role in shaping its future evolution.

The question of solidarity may not be the most urgent task Americans face today; war and economic crisis loom larger. But the question of solidarity remains important in the face of ongoing large-scale immigration and its effects on intergroup relations, which in turn affect our ability to deal with issues of economic inequality and democracy. I hope to have shown that patriotism is not easily separated from nationalism, that nationalism needs to be evaluated in light of shared principles, and that respect for deep diversity presupposes a commitment to some shared values, including perhaps diversity itself. Rather than viewing the three models of civic solidarity I have discussed as mutually exclusive – as the proponents of each sometimes seem to suggest – we should think about how they might be made to work together with each model tempering the excesses of the others.

What is now formally required of immigrants seeking to become American citizens most clearly reflects the first two models of solidarity: professed allegiance to the principles of the Constitution (constitutional patriotism) and adoption of a shared culture by demonstrating the ability to read, write, and speak English (liberal nationalism). The revised citizenship test makes gestures toward respect for first-level diversity and inclusion of historically marginalized groups with questions such as, "Who lived in America before the Europeans arrived?" "What group of people was taken to America and sold as slaves?" "What did Susan B. Anthony do?" "What did Martin Luther King, Jr. do?" The election of the first African American president of the United States is a significant step forward. A more inclusive American solidarity requires the recognition not only of the fact that Americans are a diverse people, but also that they have distinctive ways of belonging to America.

- 1 For comments on earlier versions of this essay, I am grateful to participants in the Kadish Center Workshop on Law, Philosophy, and Political Theory at Berkeley Law School; the Penn Program on Democracy, Citizenship, and Constitutionalism; and the UCLA Legal Theory Workshop. I am especially grateful to Christopher Kutz, Sarah Paoletti, Eric Rakowski, Samuel Scheffler, Seana Shiffrin, and Rogers Smith.

- 2 Philip Gleason, "American Identity and Americanization," in Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups , ed. Stephan Thernstrom (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1980), 31–32, 56–57.

- 3 David Hollinger, "From Identity to Solidarity," Dædalus 135 (4) (Fall 2006): 24.

- 4 David Miller, "Multiculturalism and the Welfare State: Theoretical Reflections," in Multiculturalism and the Welfare State: Recognition and Redistribution in Contemporary Democracies , ed. Keith Banting and Will Kymlicka (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 328, 334.

- 5 Charles Taylor, "Why Democracy Needs Patriotism," in For Love of Country? ed. Joshua Cohen (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), 121.

- 6 On the purpose and varieties of narratives of collective identity and membership that have been and should be articulated not only for subnational and transnational, but also for national communities, see Rogers M. Smith, Stories of Peoplehood: The Politics and Morals of Political Membership (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- 7 Jürgen Habermas, "Citizenship and National Identity," in Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy , trans. William Rehg (Cambridge, Mass.: mit Press, 1996), 500.

- 9 Edward Rothstein, "Connections: Refining the Tests That Confer Citizenship," The New York Times , January 23, 2006.

- 10 See http://www.uscis.gov/files/nativedocuments/100q.pdf (accessed November 28, 2008).

- 11 Habermas, "The European Nation-State," in Between Facts and Norms , trans. Rehg, 118.

- 12 Charles Taylor, "The Politics of Recognition," in Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition , ed. Amy Gutmann (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994); Will Kymlicka, Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- 13 8 U.S.C., section 1423 (1988); In re Katz , 21 F.2d 867 (E.D. Mich. 1927) (attachment to principles of Constitution implies English literacy requirement).

- 14 Act of Mar. 26, 1790, ch. 3, 1 Stat., 103 and Act of Jan. 29, 1795, ch. 20, section 1, 1 Stat., 414. See James H. Kettner, The Development of American Citizenship , 1608–1870 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 239–243. James Madison opposed the second requirement: "It was hard to make a man swear that he preferred the Constitution of the United States, or to give any general opinion, because he may, in his own private judgment, think Monarchy or Aristocracy better, and yet be honestly determined to support his Government as he finds it"; Annals of Cong. 1, 1022–1023.

- 15 8 U.S.C., section 1427(a)(3). See also Schneiderman v. United States , 320 U.S. 118, 133 n.12 (1943), which notes the change from behaving as a person attached to constitutional principles to being a person attached to constitutional principles.

- 16 Internal Security Act of 1950, ch. 1024, sections 22, 25, 64 Stat. 987, 1006–1010, 1013–1015. The Internal Security Act provisions were included in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, ch. 477, sections 212(a)(28), 241(a)(6), 313, 66 Stat. 163, 184–186, 205–206, 240–241.

- 17 Gerald L. Neuman, "Justifying U.S. Naturalization Policies," Virginia Journal of International Law 35 (1994): 255.

- 18 David Miller, On Nationality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 25.

- 19 Ibid., 25–26.

- 20 On the civic-ethnic distinction, see W. Rogers Brubaker, Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992); David Hollinger, Post-Ethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism (New York: Basic Books, 1995); Michael Ignatieff, Blood and Belonging: Journeys into the New Nationalism (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1995); Yael Tamir, Liberal Nationalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

- 21 Anthony D. Smith, The Ethnic Origins of Nations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986), 216.

- 22 See Rogers M. Smith, Civic Ideals: Conflicting Visions of Citizenship in U.S. History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997).

- 23 Miller, On Nationality , 122–123, 153–154.

- 24 Samuel P. Huntington, Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 12. In his earlier book, American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1981), Huntington defended a "civic" view of American identity based on the "political ideas of the American creed," which include liberty, equality, democracy, individualism, and private property (46). His change in view seems to have been motivated in part by his belief that principles and ideology are too weak to unite a political community, and also by his fears about immigrants maintaining transnational identities and loyalties – in particular, Mexican immigrants whom he sees as creating bilingual, bicultural, and potentially separatist regions; Who Are We? 205.

- 25 Huntington, Who Are We? 31, 20.

- 26 Christian Joppke, "The Evolution of Alien Rights in the United States, Germany, and the European Union," Citizenship Today: Global Perspectives and Practices , ed. T. Alexander Aleinikoff and Douglas Klusmeyer (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2001), 44. In 2000, the German government moved from a strictly jus sanguinis rule toward one that combines jus sanguinis and jus soli , which opens up access to citizenship to non-ethnically German migrants, including Turkish migrant workers and their descendants. A minimum length of residency of eight (down from ten) years is also required, and dual citizenship is not formally recognized. While more inclusive than before, German citizenship laws remain the least inclusive among Western European and North American countries, with inclusiveness measured by the following criteria: whether citizenship is granted by jus soli (whether children of non-citizens who are born in a country's territory can acquire citizenship), the length of residency required for naturalization, and whether naturalized immigrants are permitted to hold dual citizenship. See Marc Morjé Howard, "Comparative Citizenship: An Agenda for Cross-National Research," Perspectives on Politics 4 (2006): 443–455.

- 27 Charles Taylor, "Shared and Divergent Values," in Reconciling the Solitudes: Essays on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism , ed. Guy Laforest (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993), 183, 130.

- 28 Horace M. Kallen, Culture and Democracy in the United States (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1924), 114–115.

- 29 Michael Walzer, "What Does It Mean to Be an 'American'?" (1974); reprinted in What It Means to Be an American: Essays on the American Experience (New York: Marsilio, 1990), 46.

- 30 Charles Taylor, "Democratic Exclusion (and Its Remedies?)," in Multiculturalism, Liberalism, and Democracy , ed. Rajeev Bhargava et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 163.

- 31 The differences in naturalization policy are a slightly longer residency requirement in the United States (five years in contrast to Canada's three) and Canada's official acceptance of dual citizenship.

- 32 See Irene Bloemraad, Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

What Does it Mean to be an American? Reexamining the Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship

What Does it Mean to Be American?

- Posted November 18, 2019

- By Jill Anderson

It started with a simple and yet difficult question for Lowell High School students in teacher Jessica Lander’s Seminar in American Diversity: What does it mean to be American?

Over the course of a year, the students delved into their identity for the class project that was soon dubbed We Are America . Now, that project has grown into a national phenomenon inspiring thousands of students around the country to share stories about their unique identities.

“This project opens the door to students wanting to share and be vulnerable…,” said Lander, Ed.M.’15, during a recent workshop at Gutman Library at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. “Is that a dangerous space to bring students to? I think as an educator what I try to do in class is open doors and create space; if students want to share a particular story, they can navigate a way to share that story. I’m not going to push anyone to share a happy story, a sad story, a big story or a small story. It’s the story you want to share.”

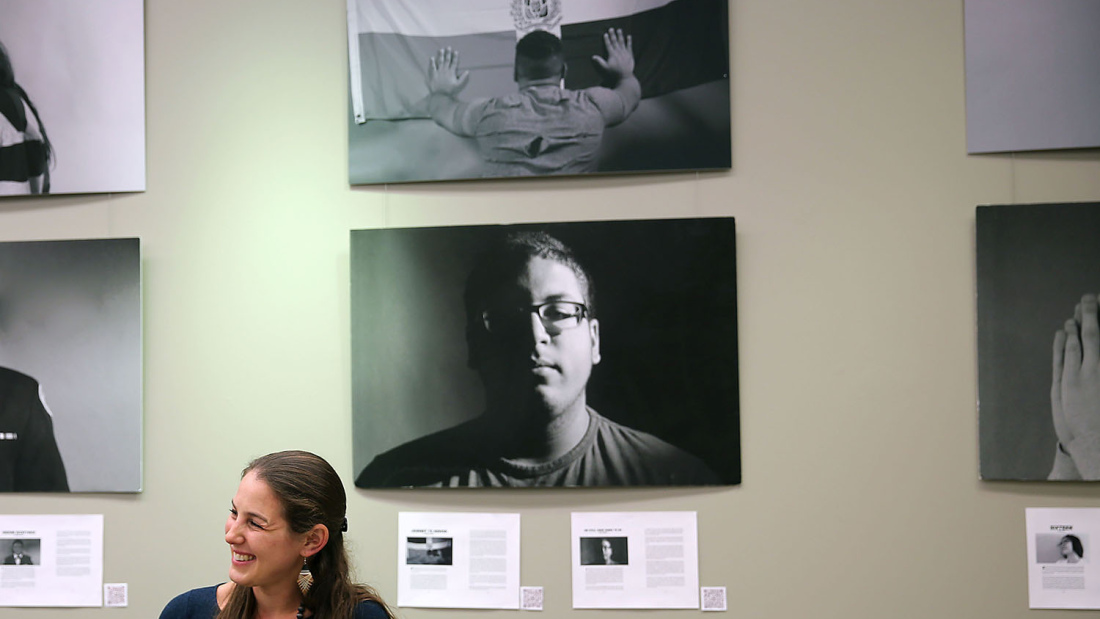

Safiya Al Samarrai's story is one of the many on display at Gutman Library's We Are America exhibit.

From the onset, Lander’s students were aware that their stories would be shared publicly, and potentially beyond their school. During the yearlong project, the students wrote many drafts of their deeply personal essays, often about immigrating to America or about certain aspects of their American experience — from mental health challenges to learning to accept the color of their skin. Those stories culminated in the book We Are America, which features portraits alongside the students’ stories.

A collection of the portraits and stories are now being exhibited at Gutman Library, where Lander and several of the students spoke about how the project came together and how other educators can explore similar topics with their own students.

“Many students were very courageous in sharing stories that are vulnerable,” Lander said. “In that space as an educator it’s [about] being there to support.”

Almost a year after the project began, it was the students – many now graduated and moved on to college – who expressed interest in scaling it beyond their school.

“On the last day of school, we had the idea: Let’s make the project a national project,” said Safiya Al Samarrai, noting that at first they weren’t sure how to make that happen but jumped at the opportunity to take the project to the next level. “It’s very exciting and powerful.”

Now, in collaboration with Facing History and Ourselves , Reimagining Migration , and New York’s Tenement Museum , the project has expanded to 23 states, involving 36 teachers and 1,300 students. At the end of next year, those new stories will be collected into different volumes based on the regions.

Robert Aliganyira, whose story is among those on display at Gutman Library's We Are America exhibit, participates in the panel discussion.

“We are breathing in a really toxic air right now …. As educators, how do we push this out, how do we filter the air, empower young people so they actually have a chance to change the conversation?” said Adam Strom, director of the education initiative at Reimagining Migration. “I think where Reimaging Migration and Jessica Lander … intersect is we believe very much in the power of young people and the power of children to enter these conversations and change these conversations. In the middle of a toxic environment when everyone is talking about you, how powerful for people to reach out and say, ‘This is actually who we are.’”

For Philly Marte, one of the students from Lander’s class who continues to work on the project as a college freshman, the stories are important. “I believe this project and these stories will create a sense of unity within this country for the people writing these stories and reading these stories,” he said. “Your story matters. Your voice matters and there’s someone else that’s gone through what you have and understands. I believe it will create more peace and more understanding across everyone who comes in contact with this project and this book. I’m not just saying that because I’m one of the people leading it but I honestly believe these stories could change a few lives.”

The latest research, perspectives, and highlights from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Educating in an Era of Mass Migration

How to Help Kids Become Skilled Citizens

An exploration of ways in which educators can instill civic identity in students

Essay On What Does It Mean to Be American Examples and Samples

- Essay on World War 2 Examples and Samples

- Essay on Ethics Examples and Samples

- Essay on Concert Review Examples and Samples

- Essay on Fahrenheit 451 Examples and Samples

- Essay on Nursing Scholarship Examples and Samples

- Essay on Pro Choice Examples and Samples

- Essay on Process Analysis Examples and Samples

- Essay on Solar Energy Examples and Samples

- Essay on Personal Narrative Examples and Samples

- Essay on Hamlet Examples and Samples

- Essay on Civil Rights Examples and Samples

- Essay on Rhetoric Examples and Samples

- Essay on Martin Luther King Examples and Samples

Recent Articles

Jun 13 2023

Latin American Women in Politics Essay Sample, Example

May 11 2023

First Generation African American College Student-Athletes and their Lived Experiences Essay Sample, Example

America’s transformation from 1877-2022 essay sample, example.

Dec 03 2018

The Traditional Native American Use of Tobacco Essay Sample, Example

Jun 07 2018

The American Dream Essay Sample, Example

Oct 30 2017

History of the American Flag Essay Sample, Example

Aug 22 2017

American Freedom: Sinclair Lewis and the Open Road Essay Sample, Example

Aug 12 2016

Happy Meal Toys versus Copyright: How America Chose Hollywood and Wal-Mart, and Why it’s Doomed Us, and How We Might Survive Anyway Essay Sample, Example

Jul 29 2016

Donald Trump: Why He Cannot “Make America Great Again” Essay Sample, Example

Jul 15 2016

The American Student Left Essay Sample, Example

20 min read

Jul 08 2016

The Big Chill: Changes in American Politics and Society from the Late 1960s to the Present Essay Sample, Example

16 min read

Jun 24 2016

The Reasons Why America Joined WW1 Essay Sample, Example

Nov 24 2015

First Published American Author of African Descent Essay Sample, Example

Jul 06 2015

African-American Folk Songs Essay Sample, Example

Dec 02 2013

Is America Becoming a Third World Country? Essay Sample, Example

Remember Me

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

Advertisement

- Previous Article

- Next Article

What does it mean to be an American?

- Cite Icon Cite

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

Sarah Song; What does it mean to be an American?. Daedalus 2009; 138 (2): 31–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/daed.2009.138.2.31

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Article PDF first page preview

Email alerts, related articles, related book chapters, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1548-6192

- Print ISSN 0011-5266

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Open Access

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Stanford University

SPICE is a program of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

What Does It Mean to Be an American?: Reflections from Students (Part 8)

- Sabrina Ishimatsu

The following is Part 8 of a multiple-part series. To read previous installments in this series, please visit the following articles: Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 , Part 4 , Part 5 , Part 6 , and Part 7 .

Since December 8, 2020, SPICE has posted seven articles that highlight reflections from 57 students on the question, “What does it mean to be an American?” Part 8 features eight additional reflections.

The free educational website “ What Does It Mean to Be an American? ” offers six lessons on immigration, civic engagement, leadership, civil liberties & equity, justice & reconciliation, and U.S.–Japan relations. The lessons encourage critical thinking through class activities and discussions. On March 24, 2021, SPICE’s Rylan Sekiguchi was honored by the Association for Asian Studies for his authorship of the lessons that are featured on the website, which was developed by the Mineta Legacy Project in partnership with SPICE.

Since the website launched in September 2020, SPICE has invited students to review and share their reflections on the lessons. Below are the reflections of eight students. I am grateful to Dr. Ignacio Ornelas, Teacher, Willow Glen High School, San Jose, California, and Aya Shehata, Hilo High School, Hawai’i, for their support with this edition. The reflections below do not necessarily reflect those of the SPICE staff.

Renn Guard, North Carolina Americans often have the privilege of being a part of many communities that help define themselves as complex, unique individuals. The past few years have demonstrated that our communities define America, a prospect that can be both concerning and hopeful. After the 2021 Atlanta spa shooting, many questioned what “Asian American” has meant and what it could mean. I observed the Asian American community connect over both their pain and frustration with the current state of the country and their hopes for a brighter future. Outside the Asian American community, many other groups, both intersecting and not, also came to sit in solidarity, reminding me that American values are rooted in communities that uphold understanding, inclusivity, and respect.

Emi Hiroshima, California By many, America is known as the “Land of Opportunity.” Certainly, this is what my great grandparents thought when they immigrated to the U.S. from Japan in the early 1900s. Although some may say it’s a less than ideal place to live, I think it provides more opportunities than other countries for those willing to try. In some countries, it is difficult for a woman to pursue certain careers or even to receive an education. They aren’t given the opportunity to even try. I believe America has a long way to go in terms of gender equality or equality for all, but women are surrounded with more chances because of others who pushed for women’s rights throughout history. In America, we are not guaranteed success, but we are provided the opportunity to always try.

Keona Marie Matsui, Hawai’i To me, being American means being free. I am free to embrace my Japanese and Filipino heritage. I am free to learn and celebrate other cultures. I am free to express myself through my physical appearance and my words. I am free to speak another language and learn many more. I am free to take advantage of the opportunities in America. But being an Asian American means that I’m stuck between identities. I was born in America, half Filipino and half Japanese, but I wasn’t born in either country. I don’t speak Tagalog or Japanese fluently; I speak English. I’m not blonde-haired or blue-eyed. I grew up in Hawai’i, surrounded by people with similar situations. Our unique experiences and identities are what make up America—and what makes us American.

Jyoti Souza, Hawai’i That is a complicated question. Some glorify being American because they immigrated from impoverished home countries. Others are ignorant to this country’s history and its current situation, or they simply do not care. For me, this country acted as a home for my grandparents who immigrated from poverty in South America. Though I am grateful for America’s seemingly open arms, it has changed vastly or never changed at all. More people are fighting against laws and bias in our government. The LGBTQ+ community asks for more freedom, African Americans demand justice, and people opposed to an election attack the White House. Some people call themselves American because of their skin color and label any others as outsiders or invaders. On the surface, being American seems like freedom and justice for all, but deep inside, it’s anything but.

Sharika Thaploo, Ohio Growing up as a first-generation immigrant in America, the idea that America was built on the great enlightenment ideals of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” was drilled into me. But to me, America meant assimilation through what I had learned from my experience in this country. I initially believed that to succeed and prosper socially I would have to discard parts of my identity that were essential to my culture. I spent time adjusting to what I believed it meant to be American. But gradually, I saw the way my identity as an Indian American affected all my decisions and my worldview. To me, being an American is bringing ideas and cultural identities into this country to make yourself and the people around you better.

Taelynn Thomas, California I view the term “American” as an identity. American is a label that represents that you are proud of what America is as a whole and that you stand with this country. A part of identifying as American means being aware that America, as a country, is not perfect and there are still challenges people face based on their race, social status, and more. This is not to say that we don’t try to fix issues in our society. There are programs that provide help for people with lower income. So, no, America isn’t perfect. But the American people can help change it in a positive way. So, when someone asks me what it means to be American, I say an American is a person who is proud of this country but still understands that we need change and is not afraid to help change this country for the better.

Hector Vela, California Being American is a title but, to me, it’s an idea. In our history, many ethnicities from across the world came to the “land of the free,” but at times weren’t treated that way. So, we changed our mindset to include many ethnicities and make it an ideal place for anyone. We evolved because people recognized the flaws and we fixed them. It is up to us to expand the acceptance of different cultures and make a safe place for future generations. What will we do to shape America into something we can be proud and happy of? To say, “I am a proud American,” we must embrace our differences and use them to make America an ideal and safe place for everyone now and in the future.

Katherine Xu, Ohio For me, the inherent beauty and ongoing question of being an American is embodied in our country’s motto: E pluribus unum (out of many, one). We are a group of individual “I’s” who have agreed to band together as a “we.” However, the issue has been to constantly question who is (or is not) included in that “we,” and how we redefine and reimagine it. Overall, we’ve succeeded in developing a better comprehensive knowledge of ourselves and acceptance of one another. However, we have historically wavered and are now at a crossroads: will we progress toward a broader meaning of “we” or will we regress to a narrower one? That is essentially the question—with all of its aspirations and fears—at the core of what it means to be an American, both personally and collectively.

What Does It Mean to Be an American?: Reflections from Students (Part 7)

What does it mean to be an american: reflections from students (part 6), what does it mean to be an american: reflections from students (part 5).

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — American Values — Understanding Of What It Means To Be An American

Understanding of What It Means to Be an American

- Categories: American Values

About this sample

Words: 971 |

Published: Jul 30, 2019

Words: 971 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1209 words

3 pages / 1410 words

2 pages / 811 words

1 pages / 1139 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on American Values

'Treason.' Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, www.law.cornell.edu/wex/treason.'Renunciation of U.S. Nationality Abroad.' U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, [...]

America, a land of opportunity, freedom, and diversity, has captured the hearts of many individuals throughout history. From its stunning landscapes to its vibrant cities, America has a unique charm that draws people from all [...]

American exceptionalism, a concept deeply ingrained in the national identity of the United States, has a rich history marked by significant events and narratives. This essay aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of American [...]

Has the American Dream changed for the better is a question that prompts us to examine the shifting ideals and aspirations of a nation. The American Dream, a concept deeply rooted in the country's history, has undergone [...]

Our lives are inherently subjected to economic, political, and sociological trends. Fortunately, the plasticity of human nature allows us to adapt to these perpetually changing environments. Over the past 60 years, the United [...]

America is a country that allows me to vote when I’m 18, I’ll have a say in who I want for as the next president, or governor of my state. America is a country where I have to follow laws for everyone’s safety. America is the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Immigration

What does it mean to be an american today smithsonian institution secretary david j. skorton leads a vibrant conversation about the role immigrants play in our nation's economy, politics, and culture., what does it mean to be an american today, read the full transcript from the latest second opinion roundtable.

Dr. David J. Skorton : Hello and welcome to Smithsonian’s Second Opinion, where we convene conversations of importance to the country. I’m David Skorton, Secretary of the Smithsonian.

One of the defining metaphors of the United States has been that our country is a “melting pot” of immigrants from around the globe. But this powerful ideal also coexists alongside an anti-immigration sentiment that has persisted throughout our nation’s history.

Many new populations have come to America over the centuries: Some came in pursuit of a more prosperous life; some came in search of protection from religious, ethnic, or political persecution. Others were brought across the Atlantic against their will. And some Americans’ ancestors were here long before the first Europeans arrived.

In spite of these differences in origin, we all grapple with the concept of what being a “nation of immigrants” entails, as each incoming community has contributed its respective heritage and culture to American society. And we celebrate that diversity today in our foods, our arts, our sciences, our entrepreneurship, our politics, and our faiths. But we also cherish the notion of a shared American identity that transcends our individual differences.

Sometime people see these two different perspectives as a source of friction -- but others see these as the core of America’s great strength.

In this edition of “Second Opinion” we will discuss the role that immigrants play in 21st century America. How do our country’s immigrants contribute to the nation as a whole today? What may be different in these times versus the past? What is gained and what is lost when immigrants come to America and when they shed their heritage and become “American”?

Ultimately, we are grappling with the question of what it means to be an American in the 21st century.

Today I'm thrilled to be joined by a terrific panel of people who bring a lot of expertise, experience, and insights to the question of what it means to be an American. I'm going to introduce them to you starting from my left to your right, beginning with Jeremy Robbins. Jeremy is the executive director of the New American Economy, a bipartisan coalition of more than 500 CEOs and mayors, making the economic case for immigration reform. Jeremy previously worked as a policy advisor and special counsel in the office of New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, a judicial law clerk to the honorable Robert Sack of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, a Robert L. Bernstein international human rights fellow working on prisoners’ rights issues in Argentina, and a litigation associate at WilmerHale in Boston.

To Jeremy's right is Ana Rosa Quintana. Ana is a policy analyst for Latin America and the Western Hemisphere at the Heritage Foundation. She leads the foundation’s efforts in U.S. policy toward Latin America. The portfolio concentrates largely on Central America, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico, and Venezuela. She has authored numerous policy studies and in addition to writing policy papers Quintana's articles have appeared in Fox News, Real Clear World , The National Interest , and The Federalist . Her work has been cited in the Wall Street Journal , The Washington Post , Bloomberg Business , The Guardian , and Deutsche Welle .

To my immediate right is Ali Noorani. Ali is the executive director of the National Immigration Forum, an advocacy organization promoting the value of immigrants and immigration. Growing up in California as the son of Pakistani immigrants, Ali quickly learned how to forge alliances among diverse people, a skill that has served him well in a career of innovative coalition building. Prior to joining the Forum, Ali was executive director of the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition and he has served in leadership roles within public health and environmental organizations.

And finally, to Ali's right is Beth Werlin. Beth is the executive director of the American Immigration Council, a D.C. based nonprofit that promotes laws, policies and attitudes that honor our history as a nation of immigrants. Beth leads the council’s efforts to ensure that everyone has a fair opportunity to present their immigration claims, that the doors remain open to those seeking safety and protection in the U.S., and that our laws and policies reflect immigrants’ economic contributions through their skills, talents and innovation.

Welcome to my panelists, it's really great to be together today. We all very much appreciate all the work that you've done and all the insights that you're about to share. I'd like to kick us off with a general question, and that is, at its root the question really before us today is what does it mean to be American? I'd love to hear your views on that. Anybody want to jump in on this one to start?

Jeremy Robbins: Well I'm happy to. I'll jump on something that Ali says all the time which is great and incredibly on point which is that whenever he talks about this issue, and I think he does it very smartly, he'll say that immigration isn't so much about politics, it's about culture. That's absolutely right. What it means to be American and what it means to be an immigrant in America is different for a lot of different people. There are two strains running through America right now, one is what it means to be America, it's about an idea. The idea of equality of opportunity or equality general, this is a country that welcomes people. Then there's another, it's a lot about history. It's more backward looking to who America was or where America was. I think some of that is situational, about what they identify in their own life, but also about what they look at towards their future. For a lot of Americans now who look ahead and see a darker future than their parents did, there's a reason a lot of people are gravitating towards that second rather than that first view of what this means.

What it means to be American and what it means to be an immigrant in America is different for a lot of different people. — Jeremy Robbins

Dr. Skorton : Thanks Jeremy. Anyone else want to comment on this one?

Beth Werlin: I'll second a lot of what you've said. I think for my family I know they were coming to the United States seeking safety and protection, and for a lot of immigrants today that's still the case. People are looking to the United States as a place where they can express themselves as individuals, where they can do that freely and openly. That's very consistent with dreams about what it means to be an American.

Dr. Skorton : Thank you, Beth. Ali, thoughts?

Ali Noorani : Go on, Ana.

Ana Quintana: I'll jump to piggy back off of what you said, my family also came here to seek safety. My family's originally from Cuba. My mother's family came in '81 with the Mariel boatlifts, and my dad was in the military and left the military, lived in Venezuela for a few years and then came over here. So many people's stories mirror that even now, right? Rather it's escaping a Communist regime to escaping crime and violence in Central America and this economic instability that exists down there. People view America as that beacon of hope and opportunity. Everybody always says I want to move northward because that's where the opportunity exists.

Dr. Skorton : Thank you.

Ali Noorani: I have to say that the way that the country is changing, when you look at the globe there are 65 million people who have been forced to leave their home, at this point you see the fastest growth in the foreign-born population in the southeast of the United States. The cultural and demographic change that we're feeling as a country is very visceral to people. When they look at that and they see on the news every night, or they're just in their Facebook feed and they see this Syrian refugee fleeing violence, their assumption is that Syrian refugee's going to be their next-door neighbor tomorrow. How, as a country, how as political leadership, civic leadership, do we help people navigate that tension? That I feel like is our biggest challenge.

Dr. Skorton: Thank you. My father was born in what is now Belarus, it was Russia in those days. When I was a kid at home and we would talk about America he would use the term, melting pot. When I went to school they used the term, melting pot. It's one of those thing that I grew up with. Well in 2014, the University of California listed the term “melting pot” as a microaggression. How do you interpret the phrase, melting pot? Is it something we should still aspire to or should we stay away from that term?

Ali Noorani: As I've been talking to organizations and people across the country, what I've realized is that folks, they love the José or the Mohammed that they know, but they're worried about and afraid of the José or Mohammed they don't know. The term, whether you call it melting pot, assimilation, or integration ...[Clinton Administration head of Immigration and Naturalization Service] Doris Meissner, in a interview I did with her, gave me the best quote, where she said, to paraphrase, Americans cherish immigration in hindsight, in present day they have real fears and anxieties.

... what I've realized is that folks, they love the José or the Mohammed that they know, but they're worried about and afraid of the José or Mohammed they don't know. — Ali Noorani

Beth Werlin: You know, probably many of you saw new census data that came out very recently showing that the places in the United States where there were the fewest immigrants are actually the places where people are most showing anti-immigrant sentiment. In some ways that's somewhat surprising, you might think that people feeling the immigrants in their community encroaching on their communities, so to say, may be the ones who actually show some anti-immigrant sentiment, but it's the opposite. It goes to what you're saying, it's about knowing these newcomers to our communities and understanding and appreciating the values that they bring.

Ana Quintana: It makes sense that people fear what they don't know. If you've never experienced something you don't want to walk into a room and the lights be off, because you don't know what's there. I guess that kind of makes sense, and kind of going back to the University of California labeling it a microagression ... I mean that is so absurd. I think that a melting pot is something that we want to aspire to. That's the great thing about America, that we're not a balkanized country where everybody's broken up into these different ethnic enclaves. At the end of the day we all are American citizens, regardless if you eat fried pork on Thanksgiving like my family does, we don't eat turkey, I've never eaten turkey on Thanksgiving. That's the most absurd thing. You eat pork, you eat rice and beans.

You still have your American flag, you never have a Cuban flag, because that's just ... You're an American citizen and we all have ... That's kind of like what we share and what binds this country together, and kind of why people are so ... It's easy to assimilate in America.

I think that a melting pot is something that we want to aspire to. That's the great thing about America, that we're not a balkanized country where everybody's broken up into these different ethnic enclaves. — Ana Quintana

Dr. Skorton : I'm going to invite myself to that next time.

Ana Quintana .: Oh you should, there is an absurd amount of food, yes.

Dr. Skorton : It sounds really good.

Ali Noorani : We do a mix of chicken curry and turkey.

Ana Quintana : Yeah.

Dr. Skorton : That's great. Jeremy, any thoughts about this?

Jeremy Robbins: Yeah, I agree very strongly with all of this. The one place I'd push back a little bit, and where we struggle as an amnesty organization is that it's more than just being exposed to people and facts, right? I look at places like Lewiston, Maine, which is a great opportunity but also challenge when you think about the immigrant story, that this is a place in the whitest state in the country and now the oldest state in the country, where it's happening what's happening a lot in America. Just depopulating, industries leaving these towns that are very economically depressed.

In Lewiston, where the industry had gone and the main street was largely shuttered, you had a large influx of Somali refugees. They started coming and then when their families were there, more people started coming because they knew people there and there was a community. You start having race riots. Like you said about Doris, that in the moment immigration looks really tough, but in hindsight it looks good. It looked like it was going to be on that trajectory, right? Because they had all these race riots, the mayor went up on national TV and said, "Stop coming." But people kept coming.

Five, ten years later when you look at main street, it's littered with Somali businesses, and when you walk into the Lewiston Sun Journal , the paper of record, and they have the honor roll on the wall, half the names are Somali. That's the great story. People come. Then that Lewiston went overwhelmingly for Trump because the anti-immigrant message really resonated there.

There was some amazing journalism done by the Associated Press and others and going, "Well what's happening here?" Because you go and you talk to the people there and by and large they can all say, "Yeah, that's right. People came in and our town is economically better for it. There are now businesses on main street that we were struggling now they've come back. Still, if the government, really they're helping all the refugees, why aren't they helping us? Why am I still struggling?"

There’s a lot that goes into that, that's economic, that's race, there's a lot of things playing into it, but it's not just that people came in, there was a rosy future and then it got better. There's still a huge challenge facing Lewiston and the larger segments of our country, especially in the southeast, that are still new gateways and are experiencing this in a really profound way.

Beth Werlin: Jeremy do you see that as different though than the past? We've gone through the cycles over and over again, we've had that happen where, you know, “no Irish need apply.” I think we've seen that with every wave of new immigrants. To me it's the same story that keeps repeating ourselves in the United States.

Jeremy Robbins: I think that's right, and when you look at the dialogue of in each generation, the words are even the same. We haven't even become inventive in the way that we push back on immigrants. I do think that there is a central tension between a part of society that really values pluralism and diversity and thinks that that is a good, and a part of society that is worried that that is taking away from the central tenet of why a melting pot should be a good thing to a lot of Americans because it seems that it is, you are coming here, you're adding to America, but you've got to become American. The idea that you're going to change what it means to be American is threatening to a lot of people.

Ana Quintana: The immigration component in Maine that you speak specifically of, so I travel to Maine quite often, northern Maine, pretty much on the Canadian border, it's where my boyfriend's family is from. I think that one of the reasons why they went to Trump or why this message of this anti-immigrant message, I don't think it's so much just on the immigration component, but it's there's so many other different things that are happening in that main social ecosystem, right? Whether it's economic depression, whether it's the second generation of Mainers who have to leave the state to be able to find any sort of opportunity, the ones who stay there have such an absurdly high drug usage. It's just there's so many things that are happening, I don't necessarily think it's just the Somalis have arrived and people are anti-Somali.

It's there is a lack of economic opportunity, there doesn't seem to be a change in the future. Maine's economic trajectory, particularly in district, it's district two, right? That's on the northern side, is on a downward trajectory. I think that's kind of why it's ... I don't know, I just don't necessarily see it as just the anti-immigrant component though. Certainly not.

Ali Noorani: There’s a deep feeling of loss. Last summer as the presidential campaign was reaching a peak, there was an analysis of the Gallup Survey, which was 95,000 person survey per week. What they found is that your typical Trump voter was economically better off than most Republicans, was protected from trade, lived in a culturally isolated community. The determining factor for them to take their vote was that they felt their child would not do better than them. There's this feeling of loss and you kind of mix all these factors up, Trump was able to tap into that anxiety about the other. The question is again, what do you do about that? How do you help people understand that yes, there are tensions as the country is changing, as communities are changing, but I feel like if we don't understand that core sense of loss, that core feeling of loss, we're just talking about microaggressions.

Ana Quintana: Yeah.

Dr. Skorton: Let's drill down a little, tiny bit more on that. The purpose of these discussions is try to enlarge all of our understanding about these very complex issues. Based on polling, Americans who feel economically vulnerable, as you've mentioned, are more likely to see immigrants as an economic threat. Are they justified in feeling this way or is there data behind that? Are immigrants an economic threat to those who are economically vulnerable?

Jeremy Robbins: Certainly I think the reality is the answer is no, immigration is writ large a very good thing for America, but those gains aren't spread equally. I think that immigrants benefit the economy hugely, but they benefit certain segments of the economy hugely. And there are costs that come with immigrants. There are costs that come with anyone. The benefits will outweigh those costs, but when you have costs that are borne locally and disproportionately on a certain population, but benefits that are borne on a different kind of population, more naturally, I think you're going to have struggles.

The reality is this, if you look at immigrants, they are more likely to be of working age, they tend to have a very different skillset than the American born, right? They're much more likely to lack a high school degree, but also much more likely to have a Ph.D. You think about how you compete in a global economy, you want to have diverse talents, you want to have diverse skills. What's happening, there are things happening in our economy that are really scary, right? There are huge riches going to some but it's not being spread. That's happening all over the developed world. Immigration is actually the one thing that we have that a lot of the other countries don't. One of the failures in this debate is that we've allowed immigration to be seen as part and parcel of globalization and automation, all of these things that are changing the economy, instead of being seen as a potential solution to it.

We want to have the skillset in our population that's going to make us adapt to this changing economy, and part of that is home growing it, having a pipeline for STEM and getting people to go to the right things. Part of it's the fact that when people vote with their feet, they want to come here, and that's by and large great for America. Are some people benefiting from that more than others? Absolutely, but that's not a failure from immigration, that's a failure from immigration policy for not being able to spread the gains. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, the last time there was a Senate comprehensive bill, found that it added $900 billion to the economy. Now you can have a lot of different views of how you would spend $900 billion to make Americans better off, but that's a lot of money to spend to make Americans better off.

Immigration is writ large a very good thing for America, but those gains aren't spread equally. — Jeremy Robbins

Dr. Skorton: Listen, I'd like to change gears a little bit and take a step away from present day politics and concerns and look in the rear view mirror a little bit about America. Let me ask you what you think history tells us about how immigrants have integrated themselves into American culture. What were the concerns about immigration at the turn of the 20th century, when my dad came over? 19th century? Have the concerns changed? Are things different now or are we really sort of seeing the same things over and over again? What are your points of view on that?

Ali Noorani: We've done a lot of work, for example, with businesses in terms of thinking about immigrant integration or assimilation into the work site. In 1915, Bethlehem Steel was the first company in the United States to provide English classes to their immigrant workforce. You think of 1915, I'm sorry, that's when everybody did it the right way. What we found is that more and more businesses across the country are taking the same steps. We now have a program that works with over 250 businesses to help their staff become citizens. We just finished a second year of a English language program with Publix, Kroger, and Whole Foods in terms of teaching English skills. What we found is that in the second year, almost 40 percent of individuals who completed the program got a promotion because of improved English language skills. They're happy because they have increased opportunities, their managers are happy because they have a more productive workforce. The integration of the immigrant community into the U.S. is happening in incredibly innovative and interesting ways every day.

Dr. Skorton: Very interesting. Others, your thoughts about whether things are different today or whether we're reliving the same things?

Beth Werlin: In many ways, we continue to relive the same things, but I do think there's something different today too. Our world has changed, technology has changed our world, we're much more, I don't know, interdependent upon activities going on in other countries. I look at that, particularly in how we approach the laws and policies around bringing in entrepreneurs and new business to our country, people have other options now. Companies can move from country to country in ways that they couldn't before. To the extent we were a place that people came to brought ideas, there's other places to bring ideas today too, and that's an important thing to remember. We want to continue to be competitive. We value that diversity of opinion, the innovation that newcomers bring to our country. I don't want to see us lose any of that energy. That's something that in this changing technology-driven world is a potential if we're not on top of it.

Our world has changed, technology has changed our world, we're much more, I don't know, interdependent upon activities going on in other countries. — Beth Werlin

Dr. Skorton: Just to jump on that for a moment, this is really one of the biggest issues that I've thought about, a lot of people are thinking about, is how attractive America still is to people around the world, from higher education to the workforce. Today, in 2017, is there something exceptional about the U.S. that continues to make us a beacon for immigrants?

Jeremy Robbins: I think undoubtedly, yes. If you look at one really good, easy way to look at that would just be through where people go to start businesses, right? In a global world, you can go anywhere you want. One of the things that's really interesting about us and the immigration law is that, and most Americans don't believe this when you tell them, but there's no visa to come here, start a business, and hire American workers, which is crazy thing that no matter where you are in the political spectrum, if someone wants to come here, start a business, and have some money invested, they're going to create jobs, probably that should be something that we want.