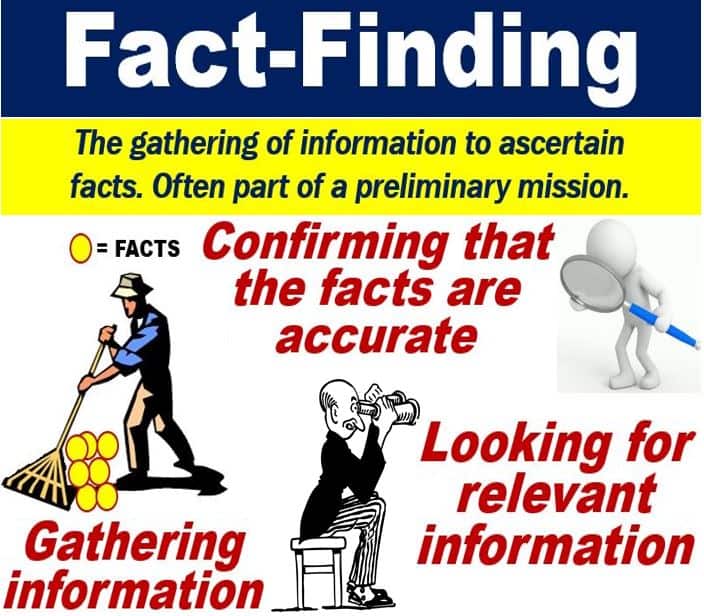

What is fact-finding? Definition and examples

Fact-Finding refers to the gathering of information . It is often part of an initial mission, i.e., preliminary research, to gather facts for a subsequent full investigation or hearing. A fact-finding tour, for example, has the purpose of ascertaining facts . You may want to check the facts about, for instance, France, before deciding to break into the French market.

In this context, ‘market’ refers to the business environment where people buy and sell things .

The process of fact-finding is essential not only for building a case or understanding a situation but also for making informed decisions in business and governance.

In an inquiry or investigation, fact-finding is the discovery stage. During this stage, people gather information by using questionnaires and other survey tools. They then assemble all the data in a report and give it, perhaps with recommendations, to the investigator.

A government or parliamentary committee may go on a fact-finding mission to discover and establish the facts of an issue.

An advancing army will send out scouts to check out the terrain ahead. They will look out for enemy soldiers, hostile terrain, opportunities, strategic advantages, etc. The scouts go out on a fact-finding mission before the troops move forward.

A fact-finding mission, according to Collins Dictionary : “is one whose purpose is to get information about a particular situation, especially for an official group.”

Fact-Finding Rules

According to Queens University IRC in Canada, there are six golden rules in fact-finding.

Go to the source

The source may be a record or an individual. Even if the source is not readily accessible, you must strive to get the best evidence you can.

Remain objective

Do not let people sway you. It is important to focus just on the facts, rather than people’s personalities or opinions.

Persistence

Do not be put off if you are not getting the information you require. Try to find out the root of the cause.

Do not become paralyzed

It is important to separate necessary from unnecessary facts. Make sure you go where the facts take you. However, do not go beyond your mandate.

Do not make assumptions

Confirm all the facts you gather again and again. If the information you have gathered is not accurate, the whole mission is pointless.

Devise a plan and follow it

When you develop a plan, think strategically. Before you begin, determine whom you need to talk to and what you need to establish. Regularly review your plan to confirm that it is effective.

According to Queens University IRC:

“When planned and executed properly, fact-finding provides a solid foundation for conducting analyses, forming conclusions, generating options and formulating sound recommendations.”

“Fact-finding may involve researching documents or existing records and data, holding focus groups, interviewing witnesses, or using written surveys and questionnaires.”

Fact-finding techniques are crucial in post-investigation phases, often used to validate the outcomes and ensure comprehensive understanding of the findings.

Compound Nouns Containing “ Fact-Finding”

In various professional fields, “fact-finding” is a compound term often used to describe the thorough search for truths and information. A compound noun is a term consisting of two or more words that function as a single noun. Here are six compound nouns that integrate “fact-finding” to describe different aspects of investigative processes, each with a definition and an example in context:

Fact-Finding Mission

A specific task or expedition aimed at uncovering facts about a particular event, situation, or allegation. Example: “The United Nations sent a fact-finding mission to the region to assess the humanitarian situation on the ground.”

Fact-Finding Committee

A group of people appointed to investigate an issue or a set of circumstances and to establish the facts. Example: “The government established a fact-finding committee to delve into the causes of the financial crisis.”

Fact-Finding Report

A document that outlines the findings and evidence gathered during an investigation. Example: “The fact-finding report was conclusive in showing the sequence of events that led to the system’s failure.”

Fact-Finding Inquiry

An investigation or research effort dedicated to gathering information about a specific topic or event. Example: “A fact-finding inquiry into the accident will commence next week to determine the root cause.”

Fact-Finding Panel

A selection of experts or authority figures tasked with investigating facts on a particular issue. Example: “The fact-finding panel included legal, environmental, and safety experts to ensure a well-rounded investigation.”

Fact-Finding Process

The systematic approach to uncovering information and verifying facts related to an investigation or study. Example: “The auditor relied on a detailed fact-finding process to understand the discrepancies in the financial statements.”

Video – What is Fact-Finding?

This video, from our YouTube partner channel – Marketing Business Network , explains what ‘Fact-Finding’ means using simple and easy-to-understand language and examples.

Share this:

- Renewable Energy

- Artificial Intelligence

- 3D Printing

- Financial Glossary

10 Fact Finding Skills and How to Develop Them

- Updated December 25, 2023

- Published August 12, 2023

Are you looking to learn more about Fact Finding skills? In this article, we discuss Fact Finding skills in more detail and give you tips about how you can develop and improve them.

What are Fact Finding Skills?

Fact-finding skills refer to the ability to gather accurate and relevant information from various sources in order to make informed decisions, solve problems, or develop a comprehensive understanding of a particular subject or situation. These skills are crucial in many aspects of life, including academic, professional, and personal contexts. Fact-finding skills involve several key components:

Research Skills

- Critical Thinking

Interviewing Skills

Information evaluation, documentation, synthesis and analysis, communication skills.

- Adaptability

Verification Techniques

Ethical considerations.

Fact-finding skills are particularly important in fields such as journalism, law, scientific research, business analysis, policy-making, and academic studies. In today’s digital age, where vast amounts of information are readily available, honing these skills is essential to discerning accurate and reliable information from misinformation or fake news.

Top 10 Fact Finding Skills

Below we discuss the top 10 Fact Finding skills. Each skill is discussed in more detail, and we will also give you tips on how you can improve them.

Research skills are like your compass in the vast landscape of information, guiding you to credible sources and helping you unearth the hidden gems of knowledge. They encompass a range of abilities that enable you to uncover relevant and accurate information while navigating through the sea of data.

These skills include knowing how to formulate effective research questions, utilizing various search engines and databases, and mastering the art of refining your search queries. Moreover, being able to evaluate sources for credibility and relevance critically is essential. You’ll need to discern between scholarly articles, reputable websites, and potentially biased sources. It’s not just about finding information; it’s about finding the right information.

How to Improve Research Skills

Improving research skills is a journey that involves both technique and practice. One concrete way to enhance these skills is by learning advanced search operators. For example, on search engines, using quotation marks (” “) around a phrase will help you find exact matches. Additionally, learning to use Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) can help you refine your searches.

Another effective method is to practice source evaluation. Compare information from different sources on the same topic and analyze their credibility and bias. Lastly, consider exploring your library’s databases and resources. Libraries often provide workshops on research skills and access to academic databases that can significantly enrich your research endeavors. Remember, the more you practice, the more confident and skilled you’ll become in navigating the sea of information effectively.

Related : 10 Research Skills and How To Develop Them

Critical thinking is the art of looking beyond the surface, of questioning and dissecting information to understand its essence truly. It’s about being a detective of ideas, uncovering biases, assumptions, and implications that might not be immediately apparent. With critical thinking, you don’t just accept information at face value – you actively engage with it, scrutinize it, and form well-informed judgments.

These skills encompass various techniques, such as analyzing arguments, identifying logical fallacies, and recognizing patterns and inconsistencies. It’s about understanding the context in which information is presented and assessing the credibility of sources. By sharpening your critical thinking skills, you become adept at distinguishing between facts and opinions, recognizing biases, and making sound decisions based on well-founded reasoning.

How to Improve Critical Thinking

Improving your critical thinking skills is an empowering journey. One concrete step you can take is practicing argument analysis. When encountering an argument, break it down into its premises and conclusions. Ask yourself if the premises adequately support the conclusion and if any logical fallacies are present.

For instance, if someone presents an argument claiming a certain product is the best without providing any evidence, you can identify this as an “appeal to emotion” fallacy. Another way to enhance critical thinking is by engaging in debates or discussions with others who hold different viewpoints. This challenges you to think on your feet, defend your position, and consider alternative perspectives.

Additionally, reading diverse materials and exposing yourself to different ideologies and cultures broadens your perspective and hones your critical thinking skills by forcing you to analyze information from various angles. Remember, critical thinking is a muscle that gets stronger with exercise, so keep engaging with complex ideas and questioning assumptions to refine your analytical prowess.

Interviewing skills are like a bridge that connects you with people’s experiences, expertise, and perspectives. It’s the art of asking the right questions, actively listening, and empathetically engaging in unraveling valuable knowledge that might not be found elsewhere.

These skills encompass various aspects, including formulating open-ended questions that encourage detailed responses, active listening to capture nuances, and adapting your approach based on the interviewee’s demeanor. Beyond the technicalities, effective interviewing requires building rapport and creating a comfortable environment where individuals are willing to share their thoughts openly. By mastering these skills, you become a skilled conversationalist who can extract meaningful narratives and insights from a wide array of individuals.

How to Improve Interviewing Skills

Improving your interviewing skills involves a blend of technique and practice. One concrete method is to prepare well-crafted questions in advance, ensuring they are open-ended and tailored to the interviewee’s expertise. For instance, if you’re interviewing a scientist, you might ask, “Can you describe the process behind your recent discovery?” Another way to enhance your skills is by honing your active listening abilities.

Practice fully engaging in conversations without interrupting, and make a conscious effort to focus on the speaker’s words and nonverbal cues. Additionally, consider recording your practice interviews and critically reviewing them to identify areas for improvement, such as refining your follow-up questions or reducing filler words. Remember, the more you immerse yourself in real-world interviews and learn from each experience, the more adept you’ll become at extracting valuable insights and crafting compelling narratives.

Information evaluation is like being a detective for truth, sifting through sources to determine credibility, relevance, and potential biases. It’s about separating the wheat from the chaff and ensuring that the information you gather is reliable and accurate.

These skills encompass a range of techniques, including assessing the credibility of sources based on authorship, publication date, and publisher reputation. It involves recognizing potential biases and critically analyzing the methodology used to gather information. Effective information evaluation also involves cross-referencing data from multiple sources to validate facts and ensure consistency. By honing these skills, you become a skilled information detective, equipped to navigate the digital landscape and make well-informed judgments confidently.

How to Improve Information Evaluation

Improving your information evaluation skills requires a combination of vigilance and practice. One concrete approach is always to check the source of the information you encounter. For example, when assessing an online article, look for the author’s qualifications and affiliations to gauge their expertise and potential biases. Another strategy is to engage in fact-checking exercises. When you come across a claim, take a moment to verify it using reputable fact-checking websites or trusted sources.

Additionally, try comparing information from different sources on the same topic to identify inconsistencies or discrepancies. For instance, if you’re researching a medical topic, comparing findings from reputable medical journals can help you discern accurate information from the questionable. Remember, the more you cultivate a critical and discerning mindset, the more adept you’ll become at separating accurate information from misinformation in our information-rich world.

Documentation is the art of capturing and organizing the information you gather in a systematic and accessible manner. It’s about creating a trail that leads back to your explored sources, ensuring that you can easily reference and cite your findings.

These skills encompass a range of techniques, including properly citing sources using recognized formats like APA or MLA, maintaining clear and detailed notes during your research process, and categorizing information based on themes or topics. Effective documentation also involves keeping track of important details such as publication dates, page numbers, and URLs. By honing these skills, you create a reliable roadmap that helps you retrace your steps and allows others to follow the path you’ve taken in your fact-finding journey.

How to Improve Documentation

Improving your documentation skills requires a blend of discipline and strategy. One concrete way to enhance these skills is by using note-taking tools or software that allow you to organize and search your notes easily. For instance, if you’re researching a history topic, consider using digital tools that allow you to tag notes with relevant keywords, making it effortless to retrieve them later. Another strategy is to establish a consistent citation routine. When you extract information from a source, immediately note down the necessary citation details.

This not only saves time but ensures accuracy when it comes to acknowledging the sources you’ve used. Additionally, practice summarizing and paraphrasing information in your own words, which not only aids understanding but also prevents unintentional plagiarism. Remember, your documentation skills are like a compass that ensures you always know where you’ve been and where you’re headed in your exploration of information.

Synthesis and analysis are about taking the puzzle pieces of data you’ve gathered and assembling them into a coherent and meaningful whole. It’s the art of identifying patterns, connections, and insights that might not be immediately apparent.

These skills encompass various techniques, including identifying key themes or concepts across different sources, comparing and contrasting different viewpoints, and drawing informed conclusions based on your collected evidence. Effective synthesis and analysis also involve critically evaluating the strengths and limitations of various arguments and sources. By honing these skills, you become a master storyteller, able to distill complex information into clear narratives that provide valuable insights.

How to Improve Synthesis and Analysis

Improving your synthesis and analysis skills involves a combination of practice and perspective. One concrete approach is to create visual aids, such as concept maps or diagrams, to represent the relationships between different pieces of information visually. For example, if you’re researching the effects of climate change, you could create a diagram showing how various factors interact and contribute to the overall phenomenon.

Another strategy is to engage in collaborative discussions or study groups where you can share your findings and interpretations with others. This not only exposes you to different perspectives but also sharpens your ability to articulate and defend your analysis. Additionally, challenge yourself to write concise summaries of your research that capture the main points and implications.

By distilling complex information into succinct summaries, you not only reinforce your own understanding but also enhance your communication skills. Remember, synthesis and analysis are the tools that transform raw information into insightful knowledge, so keep weaving those threads of understanding together to create a tapestry of wisdom.

Communication skills are about more than just conveying information – they involve crafting your message in a clear, engaging, and persuasive way that resonates with your audience. It’s the art of packaging your fact-finding journey into a compelling narrative that can inform, inspire, and influence others.

These skills encompass a range of techniques, including writing effectively to convey complex ideas in a simple manner, tailoring your message to suit the needs and interests of your audience, and using visuals and multimedia to enhance understanding. Effective communication also involves active listening, allowing you to comprehend others’ viewpoints and adapt your message accordingly. By honing these skills, you become a master of not only gathering information but also presenting it in a way that captivates and enlightens your audience.

How to Improve Communication Skills

Improving your communication skills involves a blend of practice and refinement. One concrete approach is to engage in regular writing exercises. Challenge yourself to explain a complex concept in a few simple sentences, or practice summarizing your research findings in a concise and engaging manner. Another strategy is to seek feedback from peers or mentors. Present your findings to someone who is not familiar with your topic and ask for their input on clarity, organization, and overall impact.

Additionally, consider utilizing different communication mediums. If you’re comfortable with public speaking, give presentations or workshops to share your research. Alternatively, create informative and visually appealing infographics or videos to present your findings in a more interactive way. Remember, communication skills are the gateway to sharing your knowledge with the world, so keep refining your craft to ensure your discoveries reach and resonate with your intended audience.

Adaptability is your ability to flex and adjust your fact-finding approach based on the unique demands of each situation. It’s about being resourceful and open-minded, ready to pivot and explore new avenues when the unexpected arises.

These skills encompass various techniques, such as being able to switch between different research methods depending on the availability of sources, adjusting your research questions to accommodate new insights, and learning to navigate different types of information platforms, from traditional libraries to online databases and social media.

Effective adaptability also involves managing your time efficiently to tackle unexpected challenges without losing focus on your ultimate goal. By honing these skills, you become a versatile information explorer, equipped to navigate the twists and turns of your fact-finding journey.

How to Improve Adaptability

Improving your adaptability skills requires a combination of flexibility and strategy. One concrete approach is to set aside time for exploration. Allocate specific time slots in your research process to explore alternative sources or approaches that might not have been part of your original plan. For example, if you’re researching a historical event, consider dedicating a day to visit local archives or speak with historians who might provide new perspectives. Another strategy is to embrace technology and new research tools.

Experiment with using digital tools for data analysis or visualization or explore emerging platforms that might offer unique insights into your topic. Additionally, practice mindfulness and stress management. Staying composed when faced with unexpected challenges allows you to maintain focus and continue your fact-finding journey with clarity and determination. Remember, adaptability is your compass to navigate the ever-evolving landscape of information, so remain open to change and ready to embrace new opportunities as you journey through your quest for knowledge.

Related : Interview Questions About Adaptability +Answers

This skill is all about honing your ability to validate the accuracy and authenticity of the information you come across, ensuring that the data you use or share is reliable and trustworthy. In an era of abundant information and misinformation, mastering verification techniques is crucial for making informed decisions and maintaining your credibility as a discerning consumer and communicator of information.

Verification techniques encompass a range of skills that enable you to cross-reference and validate information from multiple sources. These techniques include source triangulation, where you verify facts by comparing information from different reputable sources and fact-checking through trusted fact-checking websites.

You’ll also learn to critically assess the credibility of sources, evaluating factors such as expertise, bias, and transparency. Developing these skills equips you to spot deepfakes, manipulated images, and fabricated content, empowering you to sift through the digital clutter and arrive at well-informed conclusions.

How to Improve Verification Techniques

Improving your verification techniques requires a blend of skepticism and diligence. One concrete approach is to perform a lateral reading. Instead of staying on a single website or source, open multiple tabs and cross-reference the information you encounter to validate its consistency and accuracy. For example, if you’re researching a scientific discovery, read articles from various reputable scientific journals to ensure the information is corroborated. Another strategy is to explore specialized databases and authoritative sources.

When seeking information on a specific topic, look for databases maintained by universities, government agencies, or established organizations in that field. Additionally, practice critical evaluation of sources by considering the author’s qualifications, the publication’s reputation, and the presence of citations or references to other credible works. Remember, verification techniques are your shield against misinformation, so always be curious, meticulous, and thorough in your quest for reliable information.

Ethical considerations involve being conscious of the ethical implications and potential consequences of your information-gathering process. It’s about treading carefully and thoughtfully as you navigate the sea of data, ensuring that your actions align with honesty, integrity, and respect for individuals and communities.

These skills encompass various aspects, including acknowledging and respecting copyright and intellectual property rights when using others’ work, seeking permission before sharing sensitive or private information, and avoiding plagiarism or misrepresentation of sources.

Ethical considerations also involve being aware of potential biases or conflicts of interest in the information you’re gathering and ensuring that your fact-finding process is transparent and accountable. By honing these skills, you become a conscientious information seeker dedicated to upholding ethical standards and contributing positively to collective knowledge.

How to Improve Ethical Considerations

Improving your ethical considerations involves a blend of awareness and conscious decision-making. One concrete approach is to familiarize yourself with copyright laws and fair use guidelines in your jurisdiction. When using or referencing others’ work, ensure you provide proper attribution and adhere to any licensing requirements. For instance, if you’re using images from online sources, choose those labeled for reuse or modification with proper attribution. Another strategy is to examine potential biases in your sources critically.

Be vigilant in identifying any political, commercial, or ideological biases that could impact the objectivity of the information. Additionally, practice seeking diverse perspectives and voices. When researching a topic, make an effort to include and amplify underrepresented or marginalized voices to ensure a well-rounded and inclusive understanding. Remember, ethical considerations are the foundation of responsible fact-finding, so let your actions be guided by integrity, respect, and fairness principles as you navigate the information landscape.

Fact Finding Skills Conclusion

In conclusion, honing your fact-finding skills is a pursuit of knowledge and a transformative journey toward becoming more informed, critical, and responsible. Gathering accurate and reliable information is essential in a world inundated with data, where misinformation can spread quickly. By actively working on these skills, you empower yourself to make well-informed decisions, contribute meaningfully to discussions, and navigate the complexities of today’s information-rich landscape.

Remember that improvement comes with practice and dedication. Embrace the art of research, learning to navigate vast resources and tailor your searches to uncover hidden gems. Develop a critical eye that can distinguish between trustworthy and biased sources, ensuring that the information you rely on is credible. Cultivate your interviewing skills to tap into firsthand insights and diverse perspectives, enriching your understanding.

Documenting your findings will not only aid your own understanding but also allow you to share your discoveries transparently and ethically. As you synthesize and analyze information, patterns and connections will emerge, guiding you toward deeper insights. Effective communication is your tool to share your knowledge effectively, reaching a broader audience and making a lasting impact. Lastly, your adaptability will ensure you remain versatile and resilient in the face of new challenges.

Related : 10 Implementation Skills and How to Develop Them

Related posts:

- 10 Life Skills Coach Skills and How to Develop Them

- 10 Oratory Skills and How To Develop Them

- 10 Research Skills and How To Develop Them

- 10 Walgreens Customer Service Associate Skills and How to Develop Them

- 10 Navigation Skills and How to Develop Them

Rate this article

Your page rank:

MegaInterview Company Career Coach

Step into the world of Megainterview.com, where our dedicated team of career experts, job interview trainers, and seasoned career coaches collaborates to empower individuals on their professional journeys. With decades of combined experience across diverse HR fields, our team is committed to fostering positive and impactful career development.

You may also be interested in:

10 nail technician skills and how to develop them, 10 creative writing skills and how to develop them, 10 financial management skills and how to develop them, 10 cash handling skills and how to develop them, interview categories.

- Interview Questions

- Cover Letter

- Interview Tips

Megainterview/Contact

- Career Interview Questions

- Write For Megainterview!

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy / GDPR

- Terms & Conditions

- Contact: [email protected]

Sign-up for our newsletter

🤝 We’ll never spam you or sell your data

Popular Topics

- Accomplishments

- Career Change

- Career Goals

- Communication

- Conflict Resolution

- Creative Thinking

- Cultural Fit

- Customer Service

- Entry-Level & No Experience

- Growth Potential

- Honesty & Integrity

- Job Satisfaction

- Negotiation Skills

- Performance Based

- Phone Interview

- Problem-Solving

- Questions to Ask the Interviewer

- Salary & Benefits

- Situational & Scenario-Based

- Stress Management

- Time Management & Prioritization

- Uncomfortable

- Work Experience

Popular Articles

- What Is The Most Challenging Project You Have Worked On?

- Tell Me About a Time You Had to Deal With a Difficult Customer

- What Have You Done To Improve Yourself In The Past Year?

- Interview Question: How Do You Deal With Tight Deadlines?

- Describe a Time You Demonstrated Leadership

- Tell Me About a Time When You Took Action to Resolve a Problem

- Job Interview Questions About Working in Fast-Paced Environments

- Job Interview: What Areas Need Improvement? (+ Answers)

- Tell Me About a Time You Were On a Team Project That Failed

- Tell Me About a Time You Managed an Important Project

Our mission is to

Help you get hired.

Hofplein 20

3032 AC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Turn interviews into offers

Every other Tuesday, get our Chief Coach’s best job-seeking and interviewing tips to land your dream job. 5-minute read.

Fact-checking 101

By Laura McClure on March 30, 2017 in Interviews

What are facts? Facts are the truthful answers to a reporter’s 5 key questions: who, what, when, where, and how. Facts may include names, numbers, dates, definitions, quotes, locations, research findings, historical events, statistics, survey and poll data, titles and authors, pronouns, financial data, institution names and spellings, and historical or biographical details attributed to anyone or anything. Facts are checkable.

What is fact-checking? Fact-checking is the process of confirming the factual accuracy of certain statements or claims, in order to create and share accurate, evidence-based media that relies on high-quality, reliable primary and secondary sources.

What kinds of facts do people often get wrong? The most frequent mistakes occur in the spellings of names and institutions, and the attribution or wording of quotes. These errors can be relatively harmless — for example, a throwaway remark about Ben Franklin. Or, they can be devastating — for example, listing the wrong person in a breaking news article about a bombing. If you’re a student, get in the habit of getting it right.

While the majority of factual errors are probably not nefarious, there are instances in which people may deliberately hide important facts or introduce inaccuracy. For journalists in these situations, three maxims are useful in finding the facts: ‘follow the money’, ‘consider the source’, and ‘who benefits?’ Remember, a reporter’s job is to find and share the facts that matter, even if people don’t like it.

Facts are only as good as their sources. There are two main types of sources: primary sources and secondary sources. Primary sources may include people, transcripts, videos, visitor logs, raw data, peer-reviewed scientific studies, recorded interviews, your own original research, and in-person observation. Secondary sources may include newspaper articles, magazine articles, and books. (Important note: unlike magazines, many books are not factchecked! If you’re using a book as a source, look for a bibliography or notes to track down an author’s sources, and then re-report if needed.)

As with all sources, watch out for inaccuracy, outdated information, and unconscious bias (for example, avoid disproven studies, or articles that talk about people ‘looting’ vs ‘finding’ and ‘rioting’ vs ‘protesting’). Avoid spreading inaccuracy, outdated information, or unconscious bias. Instead, try to increase the world’s supply of truth by shining a light on facts that matter.

To learn more about the media, read “ How to tell fake news from real news .”

Art credit: iStock

Laura McClure is an award-winning journalist and the TED-Ed Editor. To learn something new every week, sign up here for the TED-Ed Newsletter.

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Facts & fact checking, how the political typology groups compare.

Pew Research Center’s political typology sorts Americans into cohesive, like-minded groups based on their values, beliefs, and views about politics and the political system. Use this tool to compare the groups on some key topics and their demographics.

Many Americans are unsure whether sources of news do their own reporting

Roughly half of Americans or more were able to correctly identify whether three of the six sources asked about do their own reporting.

Around three-in-ten Americans are very confident they could fact-check news about COVID-19

Americans’ confidence in checking COVID-19 information aligns closely with their confidence in checking the accuracy of news stories broadly.

Republicans far more likely than Democrats to say fact-checkers tend to favor one side

Republicans largely say fact-checking by news outlets and other organizations favors one side. Democrats mostly think it is fair to all sides.

Younger Americans are better than older Americans at telling factual news statements from opinions

Younger U.S. adults were better than their elders at differentiating between factual and opinion statements in a survey conducted in early 2018.

Republicans and Democrats agree: They can’t agree on basic facts

Nearly eight-in-ten Americans say that when it comes to important issues facing the country, most Republican and Democratic voters not only disagree over plans and policies, but also cannot agree on basic facts. Ironically, Republicans and Democrats do agree that partisan disagreements extend to the basic facts of issues, according to a new Pew Research Center survey

Q&A: Telling the difference between factual and opinion statements in the news

Read a Q&A with Amy Mitchell, director of journalism research at Pew Research Center, on a new report that explores Americans' ability to distinguish factual news statements from opinions.

Facts on Foreign Students in the U.S.

The U.S. has more foreign students enrolled in its colleges and universities than any other country in the world. Explore data about foreign students in the U.S. higher education system.

How People Approach Facts and Information

People deal in varying ways with tensions about what information to trust and how much they want to learn. Some are interested and engaged with information; others are wary and stressed.

Education in the age of fake news and disputed facts

Lee Rainie, director of Internet, Science and Technology research at the Pew Research Center, described the Center’s research about public views related to facts and trust after the 2016 election at UPCEA's “Summit on Online Leadership.”

Refine Your Results

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7: Fact-Finding Techniques and Data

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 57129

.png?revision=1)

Introduction

Information is everywhere, but where exactly do you look when you do not know enough information to accomplish your project? Do you accept the first thing that makes sense to you? Does it really matter where we collect our info from as long as it was found on the Internet? When completing a project of any nature it is very important to gather accurate information from all parties involve to meet the project requirement and satisfy the need of the clients and stakeholders.

In this chapter, we are going to discuss the various fact-finding techniques including interview, survey, document review, direct observation and research and data validation that will help collect accurate information and how we can use those statistics to meet to project requirement.

Table of contents

- 7.1: Interview

- 7.2.1: Interpreting Survey Data

- 7.2.2: Question Order in Surveys

- 7.3: Survey Sampling

- 7.4: Other Fact-Finding Techniques and Misleading Data

- 7.5: Data Validation

- Participant Portal

Accessibility

The golden rules of fact-finding: six steps to developing a fact-finding plan.

- Queen's IRC Coach Lori Aselstine

- October 21, 2013

As labour relations professionals, we are required to engage in fact-finding on a regular basis. Good fact-finding ensures that the information upon which we form our conclusions and recommendations is credible, and that our advice is evidence-based.

When planned and executed properly, fact-finding provides a solid foundation for conducting analyses, forming conclusions, generating options and formulating sound recommendations. Fact-finding may involve researching documents or existing records and data, holding focus groups, interviewing witnesses, or using written surveys and questionnaires. The techniques employed will depend on the project or issue under consideration. What is constant across all fact-finding missions is the need for a plan to guide and document your efforts.

Developing a good fact-finding plan starts with figuring out what you need to know – what information do you have to have in order to form an evidence-based opinion. The precursors to good fact-finding include scoping the issue to determine what it is you need to answer, understanding the context within which the issue has arisen, and appreciating the “political” landscape (organizational and personal relationships often play a significant role in shaping a witness’ view of a matter) – all of these things can influence the approach you take to any given fact-finding endeavour.

I like to follow what I call my Golden Rules of Fact-Finding:

- Go to the source. The source may be a person or a record, and while not always readily accessible, you should strive to obtain the best evidence available. Search existing policies and procedures and begin to understand how they affect the issue. Identify unwritten rules or practices that form the context of the issue. Establish a recording protocol to document everything that you have gathered and always obtain original copies of documents and records.

- Stay objective. Do not become unduly swayed by the people involved — focus on facts, not on opinions or personalities.

- Be persistent. If you are not getting the information that you need, do not get derailed. Determine the root cause of why you are not getting the information. For example, have your sources signed a confidentiality agreement which precludes them from answering discussing the matter? When speaking with sources, if you are not getting the information you need, or they are deflecting your questions, probe them and get to the facts.

- Do not get paralyzed. The art of fact-finding is separating the information that is required from that which is not. Go where the facts take you, however, stay within the mandate of what it is you are investigating. Compartmentalize the facts as you gather them and delve deeper only where necessary. This will help you stay on track and avoid becoming overwhelmed.

- Do not assume. Confirm, confirm, confirm. All of the facts and information that you have gathered must be accurate. This will help you build credibility and support evidence–based decision-making.

- Have a plan and follow it. Think strategically and develop a plan. When you determine what you need to establish and whom you need to talk to before you start, the task of uncovering the facts will progress more smoothly. As you begin to obtain facts, you may branch into new areas of enquiry, be required to clarify previous statements, connect with new sources and review additional documents. Just remember that your plan is a living document and you will need to revisit and review it regularly.

In order to succeed as a trusted, strategic advisor to business executives, today’s labour relations professional requires the ability to separate fact from fiction, and formulate options and recommendations based on evidence. Developing fact-finding skills is critical to ensure success.

About the Author

As a career civil servant, Lori Aselstine has over 33 years of experience in the fields of program management, human resources and labour relations. Lori has worked in all regions of Ontario, in small, medium and large operational ministries, as well as in central agency ministries. Lori has extensive experience conducting complex investigations, developing corporate grievance management/resolution strategies and processes, developing negotiation and bargaining mandates, and managing in a complex union-management environment. As a seasoned LR professional who has conducted hundreds of enquiries, investigations, mediations, arbitrations and negotiations, Lori has established a reputation as a skilled relationship-builder and problem-solver.

Receive email updates

You may also like.

The Ever-Increasing Digital World of Work

- By Ian Cullwick

- Date: April 5, 2024

7 Steps for a Sustainable Labour Relations Strategy

- By Elizabeth Vosburgh

- Date: March 18, 2024

Talent Mobility: Reducing Self-imposed Barriers to Increase Mobility in Your Organization

- By Mark Coulter

- Date: February 21, 2024

Performance Coaching

Workplace Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

Industrial Relations Centre Queen’s University Faculty of Arts and Science

+1 888 858-7838 +1 613 533-6628

Stay connected with updates from Queen's IRC

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply. Learn more about the collection, use and disclosure of personal information at Queen’s University.

Copyright © 2023 Queen’s University IRC. All Rights Reserved.

Terms & Privacy Policy

Share this article

Download the brochure.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.4: Fact or Opinion

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 81170

- Cheryl Lowry

- The Ohio State University via Ohio State University Libraries

Fact or Opinion

An author’s purpose can influence the kind of information he or she choses to include.

Thinking about the reason an author produced a source can be helpful to you because that reason was what dictated the kind of information he/she chose to include. Depending on that purpose, the author may have chosen to include factual, analytical, and objective information. Or, instead, it may have suited his/her purpose to include information that was subjective and therefore less factual and analytical. The author’s reason for producing the source also determined whether he or she included more than one perspective or just his/her own.

Authors typically want to do at least one of the following:

- Inform and educate

- Sell services or products or

Combined Purposes

Sometimes authors have a combination of purposes, as when a marketer decides he can sell more smart phones with an informative sales video that also entertains us. The same is true when a singer writes and performs a song that entertains us but that she intends to make available for sale. Other examples of authors having multiple purposes occur in most scholarly writing.

In those cases, authors certainly want to inform and educate their audiences. But they also want to persuade their audiences that what they are reporting and/or postulating is a true description of a situation, event, or phenomenon or a valid argument that their audience must take a particular action. In this blend of scholarly author’s purposes, the intent to educate and inform is considered to trump the intent to persuade.

Why Intent Matters

Authors’ intent usually matters in how useful their information can be to your research project, depending on which information need you are trying to meet. For instance, when you’re looking for sources that will help you actually decide your answer to your research question or evidence for your answer that you will share with your audience, you will want the author’s main purpose to have been to inform or educate his/her audience. That’s because, with that intent, he/she is likely to have used:

- Facts where possible.

- Multiple perspectives instead of just his/her own.

- Little subjective information.

- Seemingly unbiased, objective language that cites where he/she got the information.

The reason you want that kind of resource when trying to answer your research question or explaining that answer is that all of those characteristics will lend credibility to the argument you are making with your project. Both you and your audience will simply find it easier to believe—will have more confidence in the argument being made—when you include those types of sources.

Sources whose authors intend only to persuade others won’t meet your information need for an answer to your research question or evidence with which to convince your audience. That’s because they don’t always confine themselves to facts. Instead, they tell us their opinions without backing them up with evidence. If you used those sources, your readers will notice and not believe your argument.

Fact vs. Opinion vs. Objective vs. Subjective

Need to brush up on the differences between fact, objective information, subjective information, and opinion?

Fact – Facts are useful to inform or make an argument.

- The United States was established in 1776.

- The pH levels in acids are lower than pH levels in alkalines.

- Beethoven had a reputation as a virtuoso pianist.

Opinion – Opinions are useful to persuade, but careful readers and listeners will notice and demand evidence to back them up.

- That was a good movie.

- Strawberries taste better blueberries.

- George Clooney is the sexiest actor alive.

- The death penalty is wrong.

- Beethoven’s reputation as a virtuoso pianist is overrated.

Objective – Objective information reflects a research finding or multiple perspectives that are not biased.

- “Several studies show that an active lifestyle reduces the risk of heart disease and diabetes.”

- “Studies from the Brown University Medical School show that twenty-somethings eat 25 percent more fast-food meals at this age than they did as teenagers.”

Subjective – Subjective information presents one person or organization’s perspective or interpretation. Subjective information can be meant to distort, or it can reflect educated and informed thinking. All opinions are subjective, but some are backed up with facts more than others.

- “The simple truth is this: As human beings, we were meant to move.”

- “In their thirties, women should stock up on calcium to ensure strong, dense bones and to ward off osteoporosis later in life.”*

*In this quote, it’s mostly the “should” that makes it subjective. The objective version of the last quote would read: “Studies have shown that women who begin taking calcium in their 30s show stronger bone density and fewer repercussions of osteoporosis than women who did not take calcium at all.” But perhaps there are other data showing complications from taking calcium. That’s why drawing the conclusion that requires a “should” makes the statement subjective.

Activity: Fact, Opinion, Objective, or Subjective?

Open activity in a web browser.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of fact-finding in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- adjudication

- interpretable

- interpretive

- interpretively

- investigate

- investigation

- reinvestigation

- risk assessment

- run over/through something

- run through something

Examples of fact-finding

Translations of fact-finding.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

spin your wheels

to waste time doing things that achieve nothing

Alike and analogous (Talking about similarities, Part 1)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Adjective

- Translations

- All translations

Add fact-finding to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of fact-finding adjective from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

fact-finding

- a fact-finding mission/visit

Definitions on the go

Look up any word in the dictionary offline, anytime, anywhere with the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app.

The Hyper-Polarization Challenge to the Conflict Resolution Field: A Joint BI/CRQ Discussion BI and the Conflict Resolution Quarterly invite you to participate in an online exploration of what those with conflict and peacebuilding expertise can do to help defend liberal democracies and encourage them live up to their ideals.

Follow BI and the Hyper-Polarization Discussion on BI's New Substack Newsletter .

Hyper-Polarization, COVID, Racism, and the Constructive Conflict Initiative Read about (and contribute to) the Constructive Conflict Initiative and its associated Blog —our effort to assemble what we collectively know about how to move beyond our hyperpolarized politics and start solving society's problems.

By Norman Schultz

September 2003

Current Implications

This essay, as so many of the other BI essays, was written in 2003. Although everything in it is still true, now, in 2018, it seems extremely naive--missing the key problem that is facing us in the U.S. today. That is the apparent total disagreement over what facts are "real," which are "fake," which "experts" are "real," which are "fake," and which sources of information (such as media outlets) are honest purveyors of "the truth," and which are purveyors of "fake news" and outright lies. More...

The Role of Information in Disputes

Disputes can occur over a seemingly endless variety of issues, and each kind of dispute carries unique challenges and management strategies. Emotional intensity, cultural contexts, value assumptions, laws, and interests differ drastically from one conflict to the next. Yet with all the differences, the vast majority of disputes have at least one common element: relevant facts.

Facts relate to conflicts in many different ways. Most often, the available information is itself disputed. Occasionally, both parties may actually agree on the available facts but disagree as to how the facts should be interpreted or applied. Many conflicts are made worse because of incomplete information, or information that is misinterpreted or misunderstood. Experts may present contradictory positions, leaving parties puzzled as to what to believe. Information can be presented in subtly biased, strategically deceptive ways. Or needed facts, for one reason or another, may be ultimately unknown, even unknowable. These kinds of factual hurdles are not just a problem for large-scale conflicts. Even the most basic interpersonal dispute often involves factual components.[1]

Sometimes facts play a core role in a conflict; they are what the fuss is all about. For example, consider the high-profile conflicts that result when a "rogue" state is thought to hide weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). While many issues are debated simultaneously ( nation-building , economic interests, human rights , justification for the use of force , and international consensus, to name a few), it would seem that these conflicts, at their core, are factual disputes over whether or not illegal weapons are actually being concealed. In the case of Iraq (2003), establishing the facts one way or the other has proven to be difficult.

In other conflicts, facts are not the central issue. Instead, they play a secondary role; while factual information may seem important and may be hotly debated, the dispute is essentially over non-factual issues. For example, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict involves a dispute over historical facts, regarding who occupied what territory first or which side engaged in the first aggressive move. Yet it is hard to imagine that the conflict would end if these factual issues were resolved. Other issues, such as feelings of entitlement, loss, and cultural and religious values, are perhaps more important, and cannot be reduced to a factual debate. Instead, the information (or lack thereof) plays a complicating role in this already tangled conflict.

Getting Good Information

There are many ways to address factual issues in conflicts, but it is most important that factual issues in a conflict setting are addressed, rather than ignored. Even if some kind of consensus can be reached, there is little hope that negotiated agreements will be effective if key facts are left uninvestigated.

The way facts are handled in conflicts depends on the situation. An important initial question is, w hat kinds of facts relate to this conflict? The kinds of facts involved, to a large extent, determine the character of the subsequent inquiries. Determining the validity of one kind of fact requires a different body of experts and fact-finding method from another fact type. For example, technical facts differ from historical and legal facts in that they require experimental evidence and endorsement from scientists or technical experts, as opposed to lawyers, historians, or eyewitnesses.

It is also important to ask, w hat is the status of the information at hand? It should be noted whether or not a factual dispute actually exists. What initially looks like a factual dispute might be simply a misunderstanding or poor communication. It can even be the case that parties agree on the facts, but do not know they agree because of skepticism or polarization . If this is so, common ground might be reached by clarifying what is agreed on. Yet the process of exposing the facts can also work in the other direction; in some instances a factual dispute may be reopened when one probes the information available. This need not be considered a setback; it might be necessary to bring a latent, suppressed factual dispute out in the open.[2]

To what extent the necessary information is subject to uncertainty or knowledge gaps is also important. Where uncertainty exists, debates and distrust commonly follow. Unknowns provide the most basic fuel for debates because they allow parties to fill in knowledge gaps with whatever is to their own advantage. The ability to show both parties the difference between what is really known and what unknown, can go a long way toward settling conflicting views. It can also help as a reality check for the parties, giving them advance warning of the potential limits of fact-finding, even under the best of conditions.

In many conflicts, factual issues are blended with value concerns. Sometimes this is not an accident; it might be in a party's favor to make its values look like facts, since facts carry a lot of argumentative weight. On rare occasions, it can be strategic for parties to dress up factual information such that it sounds like a moral appeal, in the hope of gaining sympathy. Yet facts and values are inherently different and, therefore, must be addressed by different means. Exposing values that are being passed off as facts, and vice-versa, allows parties to more accurately decide what they can and cannot accept.

Once the scope of the relevant information is defined and whatever is under dispute is clarified, fact-finding can start. Fact-finding refers to the process of finding the best information available for use in making decisions and agreements, instead of relying on opinion, strategic propaganda, or biased beliefs. The ultimate goal of fact-finding is to obtain trustworthy information .[3]

There are several ways to achieve this goal. The best method depends on the kinds of facts sought, and on the character of the conflict:

- Where it is possible to get parties on opposing sides to work together, joint fact-finding is an advantageous option.

- If parties are not amenable to working together, it may be necessary to employ a neutral fact-finder or fact-finding body. In the U.S., for example, an "environmental impact assessment" is required for any major federal action that is likely to affect the environment. This impact study is usually completed by a neutral body that examines the positive and negative impacts of the proposal as well as a number of alternatives. Impact studies can also be completed as a fact-finding measure in other kinds of disputes as well.

- In extreme cases, especially where violations of international law or human rights are suspected, a truth commission or international tribunal can be used.

Joint fact-finding, neutral fact-finding, and impact studies can either start from the ground up -- meaning they can do independent research into the questions in dispute, or they can review and utilize existing research. Sometimes oversight committees are used to review the available research can provide parties with some assurance as to the accuracy and applicability of the information, without requiring that research be replicated.

Realistic Expectations

It is important to have realistic expectations of a fact-finding endeavor. A successful fact-finding effort results in a determination of how much agreement has been achieved, where facts remain in dispute, and where there are irreducible unknowns and uncertainties, in addition to establishing some hard facts. It is unreasonable to expect that all the relevant facts can be absolutely determined. It may also be unreasonable to expect that all involved people will understand either the established facts or their implications. Facts can be complex, especially in today's world -- sometimes too complex for non-experts, such as decision-makers, stakeholders , and the public. In order for decisions to be made, these parties must be given a clear picture of the information by utilizing the best methods of factual communication. Yet in addition to enabling understanding and comprehension, diplomacy must also be used.

Ultimately, even if a conflict is at its core a factual dispute, establishing agreement on the factual issues probably will not end the conflict, as facts alone are seldom sufficient for resolving conflicts. They must be assimilated into each party's decision-making processes. This means addressing what the facts mean, how they relate to the positions of each side, how realistic the options are, what each option's repercussions might be, and what the potential costs and benefits are to each side. The party's interests, community values, conventions and cultural norms, laws, and practical concerns must all be factored in. The consideration of all these factors is what the policy-making process is all about, and the process is often messy since a perfectly logical, comprehensive, and effective analysis is bound to be impractical.[4]

Even considering such limitations, obtaining factual consensus can greatly improve a conflict's character. Agreeing on the status of the facts allows for a constructively refocused dispute of the real issues, as well as the ability to forge knowledgeable, farsighted, effective, and ultimately more stable agreements.

This essay, as so many of the other BI essays -- was written in 2003. Although everything in it is still true, now, in 2018, it seems extremely naive--missing the key problem that is facing us in the U.S. today. That is the apparent total disagreement over what facts are "real," which are "fake," which "experts" are "real," which are "fake," and which sources of information (such as media outlets) are honest purveyors of "the truth," and which are purveyors of "fake news" and outright lies.

Although different social and political groups have always had different worldviews, until recently there were some commonalities, and people on the different sides were willing to talk to each other to sort things out. The solutions offered in this original essay work when that is the case.

When I was growing up (a long time ago, I confess!) there were three television channels and CBS's evening news anchor, Walter Cronkite, was the "most trusted man in America." If it was on the Cronkite show, it was TRUE.

Then came cable news, and the proliferation of different versions of "truth" took hold. This was amplified immensely by the development of the Internet, and careened completely out of control in the 2016 election when we learned about "bots" and "trolls," and we elected a President of the United States who knowingly lies about facts on a regular basis. (Although his supporters will assert that is a partisan statement, even Trump himself admitted today that he "made stuff up" in a meeting with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.) Most observers note that he makes stuff up all the time.

In this climate, how does one do effective "fact-finding" that will have credibility on all sides and hence facilitate conflict de-escalation?

One possible way to do this is to engage in what is called, in the essay, "joint fact-finding." Republicans and Democrats together will have to work cooperatively and in good faith to determine relevant facts to the question(s) at hand, and present their findings jointly. However, neither side seems to have any interest in doing that now--it might take a major social, political, economic, or environmental catastrophe to wake us up to the need for good facts.

As long as the two sides rely on different sources for their facts (MSNBC or Fox News, for example), there is going to be no progress. And even when inquiries are ostensibly bi-partisan, the participants must actually act that way to be effective.

Thus, for example, just recently, the U.S. House Intelligence Committee issued its report on alleged Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. The Republicans on the Committe found that while Russia did, indeed, meddle in the election, (who-hoo! a fact everyone--except perhaps Mr. Trump himself--agrees on) they did not find any evidence, they said, that the meddling favored Donald Trump. The Democrats on the Committee, however, strongly objected to that assertion, asserting that the meddling most certainly did favor Donald Trump, and that concluding the investigation before all the facts were in was a clearly partisan act.

This illustrates that to be effective in adjudicating facts, joint fact-finding must, indeed, by done in a cooperative manner, with all sides agreeing to the process and, as much as possible, with the conclusions.

How else might we adjudicate partisan facts in our current extremely polarized and distrustful climate? We'll be looking at this question more extensively in the Conflict Frontiers Seminar.

--Heidi Burgess, March 15, 2018

Back to Essay Top

[1] For example, your 13-year-old son comes home smelling like cigarette smoke. An argument begins because you think he has been smoking. Whether he was smoking, or he was merely standing near someone who was, is the likely subject of a factual dispute.

[2] For example, if one side is using an enormous power advantage to manipulate information, exposing the real factual dispute might be a method of empowerment , ultimately avoiding the backlash of a one-sided win. In this respect, fact-finding can be used to reach agreements that are more stable over time.

[3] Even when information is sketchy, uncertain, and inconclusive, fact-finding commonly has other good "side effects." The most important of such effects is that a fact-finding endeavor gives conflicting parties an opportunity to work together on a "neutral" topic (the facts), and in doing so can ease tensions via the pursuit of a common goal (the answers). If done properly, working together will humanize the parties and make them more amenable to forming an agreement, even if the facts themselves cannot ultimately be agreed upon.

[4] For a discussion of this problem, see Charles Lindblom, The Policy-Making Process (Prentice-Hall, 1992).

Use the following to cite this article: Schultz, Norman. "Fact-Finding." Beyond Intractability . Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: September 2004 < http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/fact-finding >.

Additional Resources

The intractable conflict challenge.

Our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious, and the most neglected, problem facing humanity. Solving today's tough problems depends upon finding better ways of dealing with these conflicts. More...

Selected Recent BI Posts Including Hyper-Polarization Posts

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Roles - Part 2 -- The first of two posts explaining the actor roles needed for a massively parallel peacebuilding/democracy building effort to work, which combined with an earlier post on strategy roles, makes up the current MPP role list.

- Lorelei Kelly on Strengthening Democracy at the Top and the Bottom -- Lorelei Kelly describes the work of the bipartisan Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress which passed 202 recommendations, many unanimously. Over 1/2 have been implemented and most others are in progress.

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links for the Week of March 24, 2024 -- A rename of our regular "colleague and context links" to highlight how these readings and the activities they describe all fit within our "massively parallel" peace and democracy building framework--or show why it is needed.

Get the Newsletter Check Out Our Quick Start Guide

Educators Consider a low-cost BI-based custom text .

Constructive Conflict Initiative

Join Us in calling for a dramatic expansion of efforts to limit the destructiveness of intractable conflict.

Things You Can Do to Help Ideas

Practical things we can all do to limit the destructive conflicts threatening our future.

Conflict Frontiers

A free, open, online seminar exploring new approaches for addressing difficult and intractable conflicts. Major topic areas include:

Scale, Complexity, & Intractability

Massively Parallel Peacebuilding

Authoritarian Populism

Constructive Confrontation

Conflict Fundamentals

An look at to the fundamental building blocks of the peace and conflict field covering both “tractable” and intractable conflict.

Beyond Intractability / CRInfo Knowledge Base

Home / Browse | Essays | Search | About

BI in Context

Links to thought-provoking articles exploring the larger, societal dimension of intractability.

Colleague Activities

Information about interesting conflict and peacebuilding efforts.

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Beyond Intractability or the Conflict Information Consortium.

Beyond Intractability

Unless otherwise noted on individual pages, all content is... Copyright © 2003-2022 The Beyond Intractability Project c/o the Conflict Information Consortium All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without prior written permission.

Guidelines for Using Beyond Intractability resources.

Citing Beyond Intractability resources.

Photo Credits for Homepage, Sidebars, and Landing Pages

Contact Beyond Intractability Privacy Policy The Beyond Intractability Knowledge Base Project Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess , Co-Directors and Editors c/o Conflict Information Consortium Mailing Address: Beyond Intractability, #1188, 1601 29th St. Suite 1292, Boulder CO 80301, USA Contact Form

Powered by Drupal

production_1

Definition of 'fact-finding'

- fact-finding

fact-finding in American English

Fact-finding in british english, examples of 'fact-finding' in a sentence fact-finding, related word partners fact-finding, trends of fact-finding.

View usage over: Since Exist Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

In other languages fact-finding

- American English : fact-finding / ˈfæktfaɪndɪŋ /

- Brazilian Portuguese : de investigação

- Chinese : 调查真相的

- European Spanish : de investigación

- French : d'enquête

- German : Erkundungs-

- Italian : di indagine

- Japanese : 視察の

- Korean : 진상 조사의

- European Portuguese : de investigação

- Spanish : de investigación

Browse alphabetically fact-finding

- fact reflected in

- fact-based drama

- fact-finding mission

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'F'

Related terms of fact-finding

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Findings

Definition:

Research findings refer to the results obtained from a study or investigation conducted through a systematic and scientific approach. These findings are the outcomes of the data analysis, interpretation, and evaluation carried out during the research process.

Types of Research Findings

There are two main types of research findings:

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative research is an exploratory research method used to understand the complexities of human behavior and experiences. Qualitative findings are non-numerical and descriptive data that describe the meaning and interpretation of the data collected. Examples of qualitative findings include quotes from participants, themes that emerge from the data, and descriptions of experiences and phenomena.

Quantitative Findings

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numerical data and statistical analysis to measure and quantify a phenomenon or behavior. Quantitative findings include numerical data such as mean, median, and mode, as well as statistical analyses such as t-tests, ANOVA, and regression analysis. These findings are often presented in tables, graphs, or charts.

Both qualitative and quantitative findings are important in research and can provide different insights into a research question or problem. Combining both types of findings can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon and improve the validity and reliability of research results.

Parts of Research Findings

Research findings typically consist of several parts, including:

- Introduction: This section provides an overview of the research topic and the purpose of the study.

- Literature Review: This section summarizes previous research studies and findings that are relevant to the current study.

- Methodology : This section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used in the study, including details on the sample, data collection, and data analysis.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including statistical analyses and data visualizations.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains what they mean in relation to the research question(s) and hypotheses. It may also compare and contrast the current findings with previous research studies and explore any implications or limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : This section provides a summary of the key findings and the main conclusions of the study.

- Recommendations: This section suggests areas for further research and potential applications or implications of the study’s findings.

How to Write Research Findings

Writing research findings requires careful planning and attention to detail. Here are some general steps to follow when writing research findings:

- Organize your findings: Before you begin writing, it’s essential to organize your findings logically. Consider creating an outline or a flowchart that outlines the main points you want to make and how they relate to one another.

- Use clear and concise language : When presenting your findings, be sure to use clear and concise language that is easy to understand. Avoid using jargon or technical terms unless they are necessary to convey your meaning.

- Use visual aids : Visual aids such as tables, charts, and graphs can be helpful in presenting your findings. Be sure to label and title your visual aids clearly, and make sure they are easy to read.

- Use headings and subheadings: Using headings and subheadings can help organize your findings and make them easier to read. Make sure your headings and subheadings are clear and descriptive.

- Interpret your findings : When presenting your findings, it’s important to provide some interpretation of what the results mean. This can include discussing how your findings relate to the existing literature, identifying any limitations of your study, and suggesting areas for future research.

- Be precise and accurate : When presenting your findings, be sure to use precise and accurate language. Avoid making generalizations or overstatements and be careful not to misrepresent your data.

- Edit and revise: Once you have written your research findings, be sure to edit and revise them carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, make sure your formatting is consistent, and ensure that your writing is clear and concise.

Research Findings Example

Following is a Research Findings Example sample for students:

Title: The Effects of Exercise on Mental Health

Sample : 500 participants, both men and women, between the ages of 18-45.

Methodology : Participants were divided into two groups. The first group engaged in 30 minutes of moderate intensity exercise five times a week for eight weeks. The second group did not exercise during the study period. Participants in both groups completed a questionnaire that assessed their mental health before and after the study period.

Findings : The group that engaged in regular exercise reported a significant improvement in mental health compared to the control group. Specifically, they reported lower levels of anxiety and depression, improved mood, and increased self-esteem.

Conclusion : Regular exercise can have a positive impact on mental health and may be an effective intervention for individuals experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Applications of Research Findings

Research findings can be applied in various fields to improve processes, products, services, and outcomes. Here are some examples: