The Imperfect Power of I Am Not Your Negro

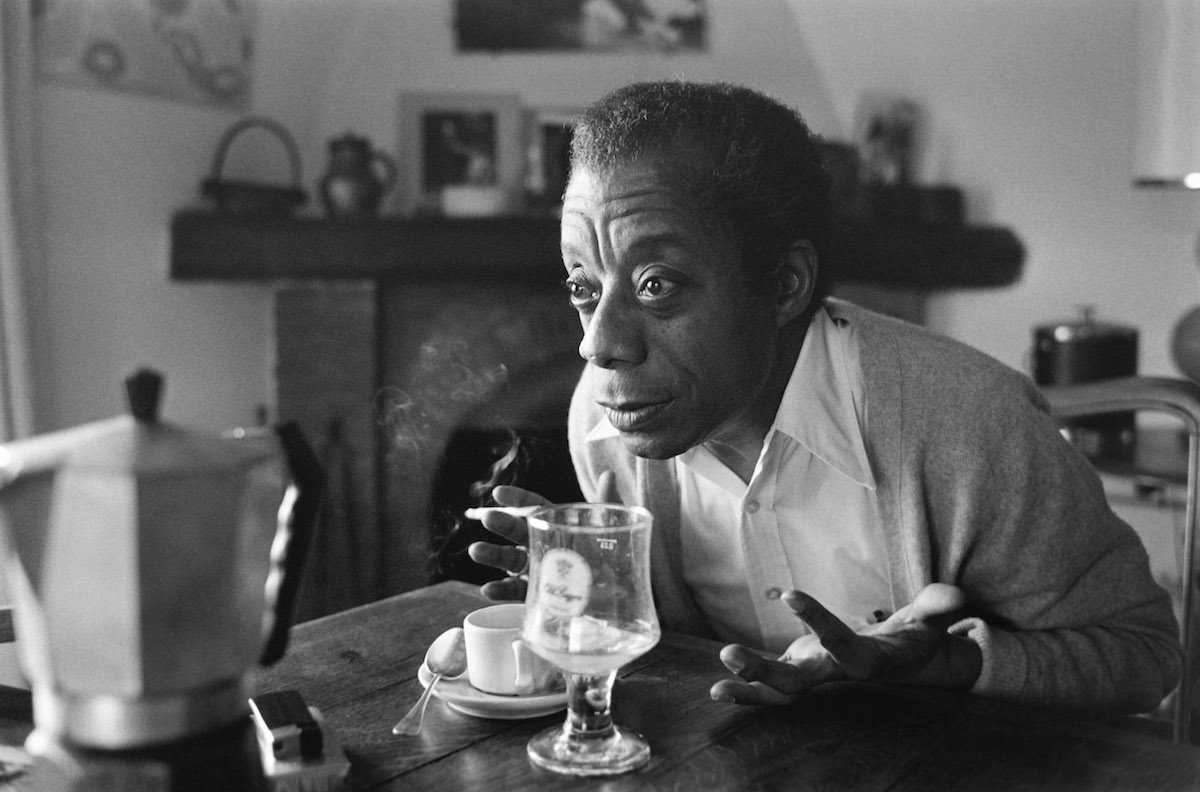

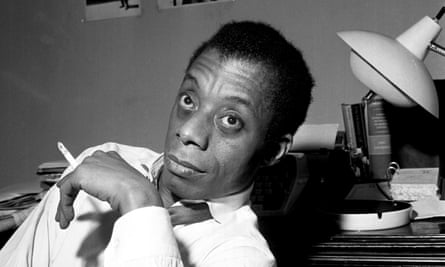

Raoul Peck’s documentary brings to life James Baldwin’s urgent ideas about race in America, even if it leaves out a key aspect of the writer’s life and work: his sexuality.

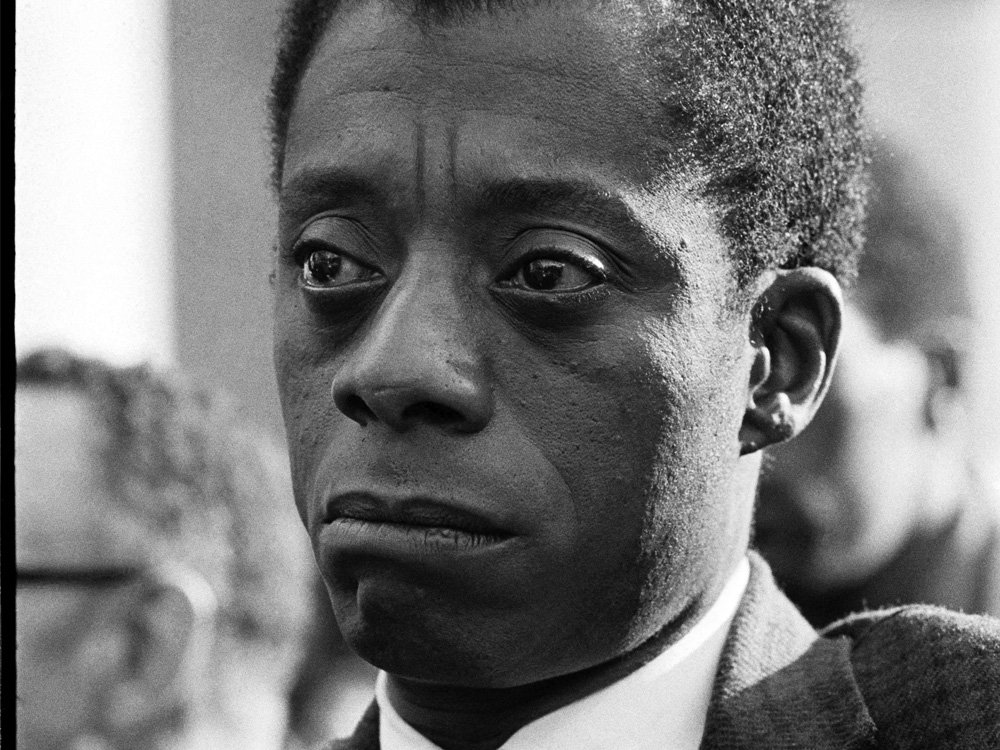

A novelist, essayist, playwright, and poet, James Baldwin was a writer with an arsenal of artistic talent and moral imagination. His signature style was his prose—startling in its intricate design and depth of perception, and fierce in its determination to dismantle the racial assumptions of the American republic and the English language. Baldwin lent his words and energies also to the civil-rights movement and would write one of the defining books of that era, The Fire Next Time , his 1963 classic .

While Baldwin fell out of critical favor in the last decade of his life, and in the years that followed his death in 1987, his work always remained a source of deep and demanding insight and beauty—which is why it’s so heartening to witness the national revival he is currently enjoying. This past September, at the dedication ceremony of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, President Barack Obama began his remarks by quoting from Baldwin’s short story, “Sonny’s Blues.” A group of arts and educational institutions in New York City declared 2014 “The Year of James Baldwin.” And, over the past decade, he has received an unprecedented level of scholarly attention, including the founding of an annual journal committed to reappraising and preserving his legacy.

Recommended Reading

Between the World and Me : Baldwin's Heir?

How Restaurants Got So Loud

Why No One Answers Their Phone Anymore

Now add to this list the director Raoul Peck’s powerful but imperfect documentary I Am Not Your Negro, which received critical acclaim and a Best Documentary Oscar nomination before it opened nationwide on February 3. The film draws its inspiration from Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript, Remember This House , intended to be a personal recollection of his friends, the civil-rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.—all of whom were assassinated within five years of each other. About a decade after King’s death, in a letter dated June 30, 1979, Baldwin told his literary agent that he had started sketching out a new book in which he wanted the lives of these extraordinary men “to bang against and reveal one another as they did in life.” Baldwin made little progress on the project, however, and left behind only 30 pages by the time he died in 1987.

I Am Not Your Negro ’s narrative voice comes from this unfinished manuscript, in addition to Baldwin’s published works and various television appearances. Unlike conventional documentaries that cede narrative control to family members, friends, and experts to shed light on the film’s subject, Peck’s film relies almost exclusively on Baldwin’s writings, read by Samuel L. Jackson. This ingenious move allows viewers to fully appreciate Baldwin’s unmatched eloquence and form a portrait of the artist through his own words, even if the film largely (and somewhat inexplicably) omits a crucial aspect of his work and life: his sexuality.

I Am Not Your Negro begins with the author’s return to the U.S. in 1957 after living in France for almost a decade—a return prompted by seeing a photograph of 15-year-old Dorothy Counts and the violent white mob that surrounded her as she entered and desegregated Harding High School in Charlotte, North Carolina. After seeing that picture, Baldwin explained, “I could simply no longer sit around Paris discussing the Algerian and the black American problem. Everybody was paying their dues, and it was time I went home and paid mine.” I Am Not Your Negro chronicles Baldwin’s life through the civil-rights movement, focusing on his personal relationships to Medgar, Malcolm, and Martin.

Repeatedly, the documentary demonstrates Baldwin’s unique ability to expose the ways anti-black sentiment constituted not only American social and political life but also its cultural imagination. Baldwin was an avid moviegoer and wrote about a number of films in his 1976 book, The Devil Finds Work , writings that are brought to life in the documentary. I Am Not Your Negro uses choice scenes from various films— Dance, Fools, Dance (1931), Imitation of Life (1934), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), among others—to show how Hollywood traffics in stereotypes of black menace and subservience as foils for white purity and innocence. In a reflexive move, then, Peck’s film also becomes a commentary on a U.S. movie industry that was bent on reifying racial stereotypes and on perpetuating a fiction of America as the greatest purveyor of freedom, democracy, and happiness.

However much a documentary about American life in the 1960s, I Am Not Your Negro also uses Baldwin’s insights to illuminate our own contemporary reality. The movie’s most gripping scenes intercut footage of police violence directed against black people in the ’60s and shots of similar violence enacted today, using Baldwin’s words to collapse the distance between the two eras. The juxtaposition bracingly highlights the uncanny similarity between the series of black deaths that punctuated Baldwin’s life during the civil-rights era, and the series of deaths—of Aiyana Jones, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and so many others—that mark our own calendar.

Yet for all its recognition that the circumstances of Baldwin’s time echo in the events of today, I Am Not Your Negro remains oddly silent on the role of sexuality in Baldwin’s work and life. Baldwin was one of the first American writers to write openly about queer sexuality. As early as 1949, Baldwin had broached the subject in his essay “The Preservation of Innocence,” and had made it a central theme in his fiction, beginning with his second novel, the 1956 masterpiece Giovanni’s Room . In fact, in 1979, when he began to sketch Remember This House , he had just published his last and arguably finest novel, Just Above My Head , the story of an internationally acclaimed black gay gospel singer.

I Am Not Your Negro presents no sense of this essential thread in Baldwin’s work. Only a passing instance gestures to his sexuality in the film, which reproduces a short sentence from an FBI memo that identifies Baldwin as a suspected homosexual. That the film uses the FBI to account for a major element of Baldwin’s life and corpus, instead of the author’s own voice, further compounds the silence. The apparent desire to represent Baldwin as the quintessential Race Man—a public spokesman and leader of African Americans with ostensibly straight bona fides—goes against not only the principles of Baldwin’s work, but also the reality of his fraught position in the civil-rights movement as a queer black man.

During the ’60s, liberals and radicals alike mocked and attacked Baldwin because of his sexuality. President John F. Kennedy, and many others, referred to him disparagingly as “ Martin Luther Queen ”; and Eldridge Cleaver, one of the leaders of the Black Panther Party, wrote in his memoir Soul on Ice : “The case of James Baldwin aside for a moment, it seems that many Negro homosexuals, acquiescing in this racial death-wish, are outraged and frustrated because in their sickness they are unable to have a baby by a white man.” In Baldwin’s No Name in the Street (1971), a source from which I Am Not Your Negro draws heavily, the author responded to Cleaver’s attacks against him, but viewers wouldn’t know from the film’s narrative slant how the experience of race and sexuality were closely intertwined for Baldwin.

That Peck chose not to complicate its audience’s view of Baldwin, especially the time in Baldwin’s life when his sexuality became a liability to his public role, is a missed opportunity. And it forgoes the chance to have Baldwin’s complex life reflect the complexity of our contemporary identities—including how race and sexuality inform our lives not as discrete experiences but as mutually reinforcing ones. To be sure, as he was of America’s racial categories, Baldwin was suspicious of categories like “homosexual” or “gay” to sum up the range of human desire. Still, as he points out in one of his last essays, “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood,” from 1985: “The idea of one’s sexuality can only with great violence be divorced or distanced from the idea of the self.”

In spite of this startling omission, I Am Not Your Negro delivers a remarkable portrait of Baldwin’s life and more broadly of America’s ongoing racial dilemma. It’s a fitting effect for a film about a writer who displayed a rare vulnerability in his work, laying bare his own personal experience as text for national self-reflection. At a minimum, I Am Not Your Negro introduces viewers who may not have read Baldwin to the genius of one of America’s greatest writers. How deeply his words resonate today is a mark of his prophetic vision, which, as the film argues, this nation fails to heed at its continued peril.

Text size: A A A

About the BFI

Strategy and policy

Press releases and media enquiries

Jobs and opportunities

Join and support

Become a Member

Become a Patron

Using your BFI Membership

Corporate support

Trusts and foundations

Make a donation

Watch films on BFI Player

BFI Southbank tickets

- Follow @bfi

Watch and discover

In this section

Watch at home on BFI Player

What’s on at BFI Southbank

What’s on at BFI IMAX

BFI National Archive

Explore our festivals

BFI film releases

Read features and reviews

Read film comment from Sight & Sound

I want to…

Watch films online

Browse BFI Southbank seasons

Book a film for my cinema

Find out about international touring programmes

Learning and training

BFI Film Academy: opportunities for young creatives

Get funding to progress my creative career

Find resources and events for teachers

Join events and activities for families

BFI Reuben Library

Search the BFI National Archive collections

Browse our education events

Use film and TV in my classroom

Read research data and market intelligence

Funding and industry

Get funding and support

Search for projects funded by National Lottery

Apply for British certification and tax relief

Industry data and insights

Inclusion in the film industry

Find projects backed by the BFI

Get help as a new filmmaker and find out about NETWORK

Read industry research and statistics

Find out about booking film programmes internationally

You are here

I Am Not Your Negro review: race, rage and the American Dream

Raoul Peck’s fluid documentary uses the timeless anger of James Baldwin to animate his history of the black experience in America, from Hollywood stereotypes to police brutality.

☞ ☞ Go tell it in the fog: James Baldwin in San Francisco, 1963

Violet Lucca Updated: 12 June 2020

I Am Not Your Negro (2016)

As part of a 1961 radio panel that included fellow black literary luminaries Lorraine Hansberry and Langston Hughes, James Baldwin remarked: “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time. So that the first problem is how to control that rage so that it won’t destroy you.”

Switzerland / France / Belgium / USA 2016 Certificate 12A 93 mins

Director Raoul Peck

Colour and black & white [1.78 : 1]

UK release date 7 April 2017 Distributor Altitude movies.powster.com/i-am-not-your-negro ► Trailer

The agonising succinctness of this statement – so tight and perceptive, extemporaneous and journalistic – makes its truth sting that much more. It’s no doubt because of that furious, acidic crispness of his words that it’s Baldwin, not Hansberry, Hughes, Ralph Ellison or any other highly influential African-American writer of the 20th century, who has enjoyed a resurgence in the era of limited characters and outrage. (Baldwin secured his spot as a mid-century public intellectual through his media appearances, in part prepared by his years as a preacher in Harlem.) As Raoul Peck repeatedly demonstrates in I Am Not Your Negro , this anger is timeless, unwavering and (do I really need to say it?) completely justified; it is inseparable from the American experience.

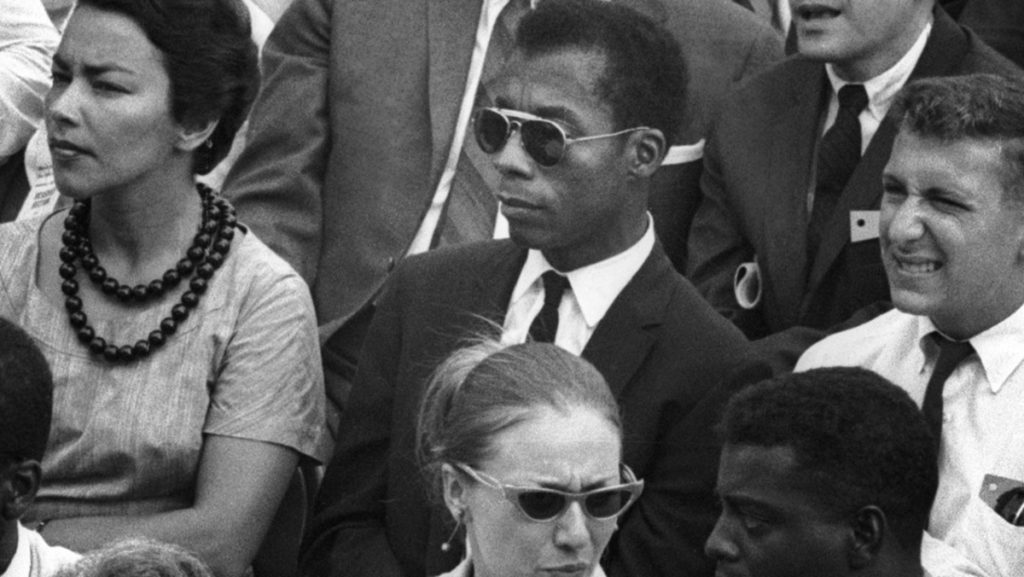

Peck’s documentary begins with Baldwin’s unfinished book Remember This House, which intended to grapple with the lives and deaths of three civil rights leaders (Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X and Medgar Evers) who were also his friends. Baldwin’s words are brought to life by the raspy, hushed voiceover of Samuel L. Jackson , who gives his best performance in more than a decade. With access to the author’s entire archive, Peck uses photographs and television clips of Baldwin with these three figures to ‘illustrate’ their relationships, but also uses pictures of the men in similar but separate places to create the illusion that they were together at times they weren’t. It may seem like a small, typical doc trick, but the rhythms established through Alexandra Strauss ’s editing stitch these images together in a way that makes them coherent and lively, filling in the gaps in historical records: although the men weren’t always photographed together, they were very often together.

I Am Not Your Negro (2016) Credit: Getty Images

After outlining the concept of the book and exploring the climate of the era (including a news clip of a pro-segregation woman claiming that God will forgive murder but not miscegenation), Peck begins using passages and ideas from The Devil Finds Work, Baldwin’s 1976 book about cinema. Because of the cohesiveness of Baldwin’s words and approach, this switch isn’t so jarring: his inability to find a man akin to his father at the dream factory, save for a blubbering prisoner who just looks like him, is crucial in the understanding of race in America. This disconnect between what Americans are told the country stands for (a place where everyone is free, a land of opportunity and scenic beauty) and what it actually is for millions (a place where the police, whose salaries are paid with all citizens’ taxes, are disproportionately more likely to kill you if you’re black) eventually becomes the main argument of Peck’s documentary.

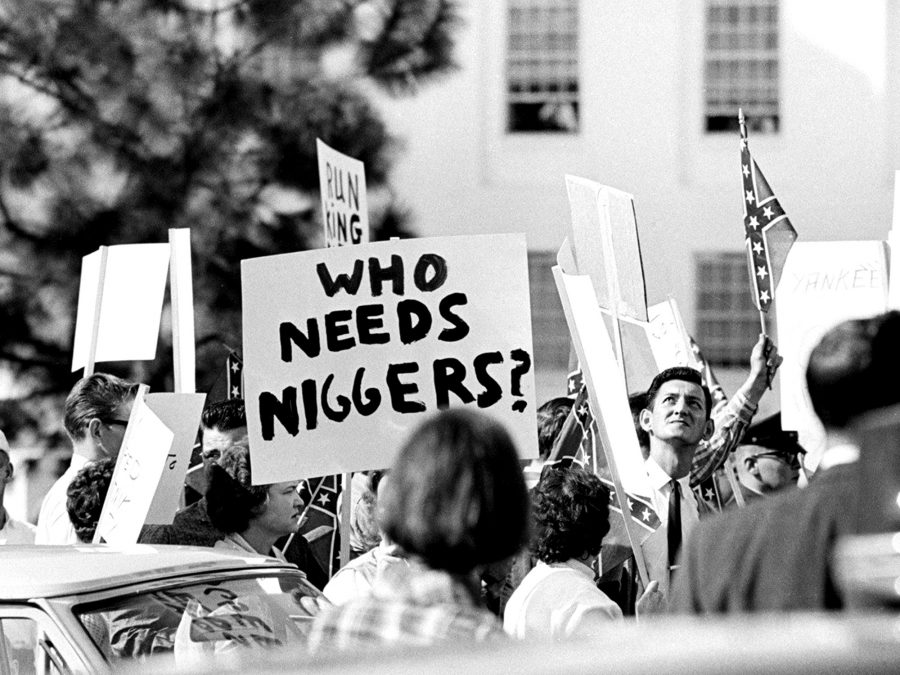

Through montage and Baldwin’s words, the film deconstructs images of white heroism (such as John Wayne ), racial forgiveness (such as Sidney Poitier falling off the train with Tony Curtis in 1958’s The Defiant Ones ) and the function of the N-word itself (as Baldwin says on The Dick Cavett Show in 1968, “If you think I’m a nigger, it means you need it…”). A particularly jarring instance is the pairing of a blasé industrial film titled The Land We Love (1966) with footage of the Watts riots in 1965, and seeing, in addition to the absence of black faces in the former, how the American Dream is a wonderful dream but is also used as a nightstick to beat those who have been systemically prevented from enjoying it. (See also: the ‘pull up your pants’/All Lives Matter crowd.) Lovely images can hurt just as much as ugly ones.

More than simply weaving together Baldwin’s thoughts in an incisive, poetic way, what makes Peck’s film truly remarkable is how it repeatedly connects the writer’s thoughts not just to the present but to all of American history and its visual culture. The pandemonium of white bodies at a picnic in a Technicolor musical turns into the pandemonium of black bodies being subjected to police brutality; early photographs of black men and women, likely counting among W.E.B. Du Bois’s ‘talented tenth’, transition to filmed portraits of African Americans in the present day confronting the gaze of the camera; we see plantation stereotypes and blackface evolve from burnt cork to coded, subservient subjects in advertising. This stream-of-consciousness approach to history is always critical and never forced: as Baldwin describes the idea that crime is only perpetrated by “a handful of aberrants”, vintage footage of a group of black teenage boys being led to a maximum-security prison is juxtaposed with the harrowing images of (white) mass shooters and a clip from Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003). Without putting too fine a point on it, Peck shows how these uniquely American myths can swing both ways.

Despite covering all this ground, Peck rather oddly avoids a crucial aspect of Baldwin: his sexuality. Save for an excerpt from his FBI file (which states that he’s possibly a homosexual), there is no mention of his queerness. Although an argument can be made for time constraints, it’s a rather glaring omission in a film that deals in nuance and multilayered critiques. Baldwin’s sexuality was as much a part of his canniness and oppositional stance as his blackness; so while I Am Not Your Negro remains an astounding statement about race, a sequel that makes his queerness visible is sorely needed.

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.

Access the digital edition

Further reading

Go tell it in the fog: James Baldwin in San Francisco, 1963

James Baldwin and beyond: radical nights at the inaugural Smithsonian African American Film Festival

Matthew Barrington

The 13th review: Ava DuVernay shines a light on America’s slavery loophole

Fanta Sylla

I turn my back on you: black movie poster art

Selma review: Martin Luther King leads his marchers onward

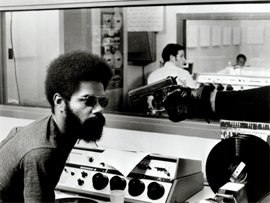

Fight for rights, will to power: The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975

The battle of Chicago: The Spook Who Sat by the Door

Back to black: the 101-year making of the oldest black American-starring feature

Back to the top

Commercial and licensing

BFI distribution

Archive content sales and licensing

BFI book releases and trade sales

Selling to the BFI

Terms of use

BFI Southbank purchases

Online community guidelines

Cookies and privacy

©2024 British Film Institute. All rights reserved. Registered charity 287780.

See something different

Subscribe now for exclusive offers and the best of cinema. Hand-picked.

This story is over 5 years old.

How an unfinished james baldwin manuscript became a documentary film.

Crowd gathering at the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington in I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Raoul Peck, director of I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures. Photo Credit: © LYDIE / SIPA, all rights reserved

James Baldwin in I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures. Photo Credit: © Bob Adelman, all rights reserved

Theatrical one-sheet for I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

ORIGINAL REPORTING ON EVERYTHING THAT MATTERS IN YOUR INBOX.

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from Vice Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

'I Am Not Your Negro' Gives James Baldwin's Words New Relevance

James Baldwin, in the new documentary I Am Not Your Negro. Dan Budnik/Magnolia Pictures hide caption

James Baldwin, in the new documentary I Am Not Your Negro.

Editor's note: This piece includes quotes from James Baldwin in which he uses a racial slur.

Fimmaker Raoul Peck's Oscar-nominated documentary I Am Not Your Negro features the work of the late writer, poet, and social critic James Baldwin. Baldwin's writing explored race, class and sexuality in Western society, and at the time of his death in 1987, he was working on a book, Remember This House . It was never completed, but his notes for that project became the foundation for Peck's I Am Not Your Negro .

Among those notes was a letter J Baldwin wrote to his literary agent, Jay Acton, in 1979. In that letter, he wrote that he wanted to explore the lives of three of his civil rights movement contemporaries and close personal friends: Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. "I want these three lives to bang against and reveal each other as in truth they did," he wrote, "and use their dreadful journey as a means of instructing the people whom they loved so much who betrayed them and for whom they gave their lives."

Movie Reviews

James baldwin, in his own searing, revelatory words: 'i am not your negro'.

Code Switch

Did i get james baldwin wrong.

Peck had been wanting to make a film about Baldwin for years, but he says it felt like an impossible one to make. When he first read Baldwin's letter, he knew he had the basis for that film. "I had access to those notes, which for me was the real opening I needed to address the film I wanted to make — which was how do I make sure that people today come back to Baldwin and the important writer that he was, and the important words that he have written, and [have] this well-needed confrontation with reality today with words that he wrote 40, 50 years ago?"

The Haitian-born filmmaker has been a fan of Baldwin's writing since he was a teenager. "He helped me understand the world I was in," Peck says. "He helped me understand America. He helped me understand the place I was given in this country."

And Peck wanted to do the same with I Am Not Your Negro. In the documentary, he weaves together archival images and footage to illustrate the impact Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X had — the ways in which they were different, and perhaps more importantly, the ways in which they were alike. Peck says MLK Jr and Malcolm X are often portrayed as being polar opposites in the civil rights movement, but at the times of their deaths, they had in fact become increasingly interested in economic injustice and the class disparity.

"One of the important parts of this story is that both of them were leaving the race issue, because they understood that it was just one side of the battle," Peck says. "It's about class — how in this country, the classes reproduce themselves. If you're born rich, you have a 99% chance to stay rich. If you are born poor, you have a 99% chance to stay poor. That's the big great story of the American dream. It was always the dream of a minority."

But I Am Not Your Negro isn't just a history of the civil rights movement, or its key players. The film also examines, as James Baldwin did in his writing, institutions of racism and the ways they have been upheld throughout the years in American society by people in power, even by Hollywood, through stereotypes and erasure.

"Leaving aside the bloody catalogue of oppression which we are, in one way, too familiar with already. What this does to the subjugated is to destroy his sense of reality," Baldwin said. "This means, in the case of an American negro, born in that glittering republic. And the moment you were born, since you don't know any better, every stick and stone, every face is white, and since you have not seen a mirror, you suppose that you are too. It comes as a great shock around the age of 5 or 6 or 7 to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians — when you were rooting for Gary Cooper — that the Indians were you! It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace, and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not in its whole system of reality evolved any place for you."

Peck says Baldwin deconstructed Hollywood, "and all the soft power that Hollywood means, and the lies that is also transported in those films. This is something that we need to confront ourselves with." Indeed, confronting ourselves is at the core of I Am Not Your Negro . When Peck began working on the film ten years ago, he meant to rely mostly on Baldwin's words. As he worked, however, the narrative shifted.

"It became scarier and scarier because I realized I was making a film where the reality was galloping even quicker than I was making it. At the time, my concern was, how do I put these important words of James Baldwin on the front row? You know, how do I make them accessible to the new generation? And as I was editing this film, we started to have those images of young black men being killed — of the resistance, of Black Lives Matter, of young people again going on the streets to protest. And it was incredible to see. It's happening again, almost the same words and the same anger. And then you see that, my God, nothing have changed fundamentally."

So Peck turns Baldwin's words into a mirror on modern audiences by juxtaposing the archival tape of the civil rights movement, or Baldwin's speeches and television appearances, with carefully chosen contemporary footage. As Baldwin speaks about the possibility or impossibility of a black president, Peck plays tape from the first Obama inauguration. As Baldwin talks about how black people have seen the "corpses of your brothers and sisters pile up around you, not from anything they have done — they were too young to have done anything," the film shows photographs of Tamir Rice and Trayvon Martin.

And, in a 1963 television segment titled "The Negro and the American Promise," as Baldwin speaks about the way Malcolm X validates protesters' existence, a young black protester shouts "I am" on the streets of Ferguson in 2013 — and Baldwin muses, "There are days — this is one of them — when I wonder, how precisely are you going to reconcile yourself to your situation here, and how are you going to communicate to the vast heedless, unthinking, cruel white majority that you are here?"

Raoul Peck says that Baldwin always spoke directly to his audiences — then and even now — and his words were frank and direct without being cruel. Baldwin put the onus of change squarely on people in positions of power and privilege. "What white people have to do," Baldwin said once, "is try to find out in their hearts why it was necessary for them to have a nigger in the first place. Because I am not a nigger. I'm a man. If I'm not the nigger here, and if you invented him, you the white people invented him, then you have to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that. Whether or not it is able to ask that question."

Because, as Baldwin wrote, "not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed if it is not faced."

- James Baldwin Documentary <i>I Am Not Your Negro</i> Is the Product of a Specific Moment in History

James Baldwin Documentary I Am Not Your Negro Is the Product of a Specific Moment in History

T hough the Oscar-nominated documentary I Am Not Your Negro is a brand new movie, by filmmaker Raoul Peck, it is also a historical document: the narration, delivered in the film by Samuel L. Jackson, was written by James Baldwin, one of America’s foremost public intellectuals of the 20th century, who died in 1987. The main source material was a 30-page packet of letters obtained by Peck from Baldwin’s youngest sister, Gloria, that were notes for a book project called Remember This House , which Baldwin began to propose in the late 1970s but never got to write.

Remember This Hous e was to be Baldwin’s magnum opus, a critique of American society from the viewpoint of the assassination of his friends Medgar Evers , Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr . As Peck aptly notes in the introduction to the film’s companion book , what these activists had in common had less to do with race and each man’s approach to the Black Liberation Movement, but rather that all three were “deemed dangerous” and “disposable.”

So, though the film provides a provocative analysis of American race relations up to the present day, as a testament to Baldwin’s continued relevance, an understanding of the moment when Baldwin began the project can add another layer to the movie’s meaning.

Baldwin’s straight-no-chaser style of criticism, as captured in his essay collection The Fire Next Time, had made him a household name more than a decade earlier. As a 1963 TIM E cover story about the author and activist noted, “in the U.S. today there is not another writer — white or black — who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South.”

At the heart of Baldwin’s argument was the question of who is responsible for the problem of racism, a point the film makes with Baldwin’s use of language. Never one to mince words, he wrote and spoke what Toni Morrison called in a 1987 remembrance of her friend the “undecorated truth” about the American illusion, which juxtaposed whiteness as American innocence with blackness as sullying American purity hence, “the Negro Problem.”

Such an illusion was based on what Jabari Asim in his book The N Word dubbed one of America’s “founding fictions,” the invention of a specific term to define blacks as subhuman and to lend credence to notions of white supremacy. As Asim notes, “From the outset, the British and their colonial counterparts relied on language to maximize the idea of difference between themselves and their African captives.” Yet it was far more than just a word. Asim demonstrated how over the centuries the N word became the ideological justification that codified American society and its institutions.

One of the most striking moments in I Am Not Your Negro comes from a 1963 PBS interview between Baldwin and the esteemed psychologist Kenneth Clark, whose research — produced with his research partner and wife Mamie Phipps Clark — had influenced the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. The Board of Education . Baldwin, rejecting America’s founding fiction quipped, “I am not a ‘nigger,’ I am a man!” He asserted that “the future of the country” depended on white peoples’ ability to ask themselves “why it was necessary to have a ‘nigger’ in the first place” and why they would have invented that idea.

Despite his harsh criticism, Baldwin remained hopefully optimistic that American equality was achievable. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 had brought a renewed sense of hope.

But, though Baldwin’s message would essentially remain the same for the rest of his life, the world changed around him. The assassination of King in 1968 was the death knell of that period’s Civil Rights Movement, and, in the decade that followed, the assassination did not spur any great movement among white Americans to reconsider. Instead, as Carol Anderson has demonstrated in her book White Rage , a political backlash against civil rights had ensued, and politicians like Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan would capitalize on opposition to civil rights victories in order to win elections. Meanwhile, Baldwin was being tracked by the FBI; as his FBI file, which spanned the years 1958-1974, attests, he was under continued surveillance.

The film captures Baldwin’s sentiments during this time with Jackson narrating, “What can I do? Well I’m tired.”

When Baldwin began work on Remember This House , he had resolved, as he stated in a 1979 speech at Berkeley, to communicate that, despite the legislative achievements of the Civil Rights Movement, blacks remained ruled by slave codes and that his fallen companions were carrying out a “modern day insurrection.” In other words, though the three assassinated men at the center of I Am Not Your Negro had given their lives to their own visions of black liberation, the film comes not from a place of simple celebration of the legacy of Evers, X and King, but from a moment when Baldwin saw, as much as ever, the need to point out to white audiences that the work those men had done had not achieved its aim, and that it was their job — white Americans — to make things better.

As he once put it , “You always told me ‘It takes time.’ It’s taken my father’s time, my mother’s time, my uncle’s time, my brothers’ and my sisters’ time. How much time do you want for your progress?”

Despite his disillusionment and his view that it was not the responsibility of blacks to fix things, Baldwin continued to use his writing and his voice throughout the 1970s and much of the 1980s as a vehicle for social change — though the world to which he spoke was a new one. On Dec. 10, 1986, almost a year before his death, Baldwin, during a Q&A session after a National Press Club lecture, insisted that the country institute “a white history week; and I’m not joking,” focused on dispelling the illusions that kept the nation in a constant state of peril.

“History is not the past,” stated Baldwin, “It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.”

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Arica L. Coleman is the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia and chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

- Consequence

Film Review: I Am Not Your Negro

Raoul Peck superbly reconstructs the nuance and passion of James Baldwin's work

Directed by

- Samuel L. Jackson

Release Year

Raoul Peck ’s I Am Not Your Negro is a superb invocation, a necessary new reading of a grand voice. It’s a subtly drawn and impactful summation of James Baldwin ’s literary essence and social conscience, confidently packaged as a 90-minute essay with crisply precise editing that explores and experiences Baldwin’s prose through new and old lenses alike. In a modern world where race relations have been recently defined by names like Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, and a President with questionable awareness of the contributions of Frederick Douglass, Baldwin’s thoughts are as essential as ever. I Am Not Your Negro is the kind of documentary that could open ears, eyes, and hearts with its moving agony and historical empathy.

Not only is I Am Not Your Negro a remembrance of the insights of Baldwin, the famed writer/scholar/orator/advocate/bon vivant, but it’s a rejuvenation of his timeless ideas. For his part, Peck isn’t here to posit solutions. He merely asks his audience to listen in on Baldwin, and think about what he meant and still means. The politics of representation, understanding the privileges and demands that come with learning about unknown ethnic experiences, and the necessity of hope for the future are all among the many ideas explored..

The film begins with the framework of Baldwin’s Remember This House . He was unable to finish the book, a triple reminiscence on the lives, impact, and assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X. Baldwin never made it past page 30, but Peck was entrusted with the manuscript, along with various notes and letters, and it acts as a jumping-off point from which I Am Not Your Negro explores the seemingly irrational dreams of a racially well-adjusted nation. These men represented a battle. They were the dialogue of Civil Rights personified. And Baldwin was in their periphery, experiencing the same plight. But he wasn’t quite the same kind of reactionary or organizer as his peers. Perhaps he marched, and was willing to put himself out there, but he fought many of his best battles through his words. As such, Peck takes an interesting narrative route by framing Baldwin’s views on those men as a functional history of the black experience in America.

Peck returns to Baldwin’s youth, characterizing multiple moments of clarity through Samuel L. Jackson ’s demure and confident narration. Jackson scales back his usual delivery, putting bass and serious inflection into every read. In “Paying My Dues,” Peck sets up Baldwin’s worldview with the curt juxtaposition of trivialized MLK bobbleheads alongside comic book characters like Thor and Iron Man in Times Square, while Baldwin waxes nostalgic over a certain era of beauty for black people in places like New York City. “I missed that style, possessed by no other people in the world,” Baldwin writes. And it reads with a longing irony in Peck’s hands.

For “Heros,” we hear Baldwin recall his white schoolteacher, a woman named Orilla “Bill” Miller, who introduced Baldwin to the economics of race, the concepts of Nazi Germany, and the power of presence in plays and movies like King Kong. Peck suggests that this awakening helped develop Baldwin’s rational loathing for stereotypes like Man Tan, or the scared, clumsy janitor in Mervyn Leroy’s film They Won’t Forget. Baldwin loathed these depictions wholesale, and was hardly shy about acknowledging his embarrassment with them. Peck matches Baldwin’s anger with stock footage of bug-eyed, racist film stereotypes throughout the years.

Baldwin witnesses systemic indignities, and the film foregrounds his ability to acutely capture his target, whatever it may have been. “Selling the Negro” is both a chronicle of the slave trade, and a meditation on the slow acceptance of black culture in the mainstream. This chapter, with Baldwin recounting MLK’s “free at last” claim while Peck layers him over footage of the Obamas marching at their inauguration, hits simultaneous notes of melancholy and optimism. Peck doesn’t let up, and is almost operatic in his multi-layered reads of Baldwin, but there’s a truthful and authentic fire to his interpretation as well.

Peck’s approach does well in capturing Baldwin’s often frustrated contemplation. Baldwin addresses the 15-year-old Dorothy Counts, harassed in 1950s North Carolina when she was integrated into predominantly white schools. I Am Not Your Negro uses this incident to measure a nation’s ugliness, and its will to change, however incremental that change may be. Peck underscores Baldwin’s recollections with a harsh series of portraits of Southern boys screeching at an innocent young woman. Baldwin is quoted as having said that he does not hate white people, but he has contemplated killing them from time to time, and the film invokes these valuable, volatile observations in rapid succession.

Baldwin resents Sidney Poitier’s star status because of the actor’s inability to be deemed sexual by the mainstream. He bemoans TV’s ability to popularize grotesque behavior (which Peck aligns with horrid talk show fights, and clips of “special episodes” of daytime shows on mixed-race marriages). Baldwin’s words are cynical, fatigued, and impassioned, but almost always nuanced. The only outburst comes late in the film, from Baldwin lashing out on Dick Cavett’s show, pained in his admission that optimism is hard to maintain. But that’s Peck’s parting thesis: no matter how awful life gets, no matter how much injustice and hatred Baldwin endured, and regardless of how hard it is to march on at the end of the day, it’s still possible. Baldwin endures as an intellectual monument to black determination. The author saw horrible things in his time, and yet his prose (and this film) simply asks his audience to reflect, and to work harder for a better future.

“The negro has not been as docile as white Americans want it to be.” Baldwin proclaims at one point. Please, listen to those words. Don’t react immediately. Let them sink in. That’s Baldwin, from decades ago, reflecting in his journals about the tension of interracial relations in America. These are unfinished thoughts from Remember This House , and yet they continue to ring as true as they ever have. His words are placed over raw footage of Selma and Ferguson, among many other images that offer a reminder of how much black America has had to overcome, and still struggles against. Peck innately understands Baldwin’s lamentations and strength, and what he was likely looking to put to paper. I Am Not Your Negro is a documentary which makes a statement not just for now, but for all time.

Personalized Stories

Around the web, latest stories.

The Pretty Good and Hilariously Bad of Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire

March 28, 2024

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Leans Harder Than Ever Before on Nostalgia: Review

March 20, 2024

Road House Review: A Ripped Jake Gyllenhaal Doesn't Rip Any Throats In Solid B-Movie Remake

March 18, 2024

The American Society of Magical Negroes Speaks Savagely With Its Satire: Review

March 15, 2024

Ethan Coen's Drive-Away Dolls Hits a Few Too Many Speedbumps: Review

February 22, 2024

Dune: Part Two Is Weirder, Wilder, and Crying Out for a Sequel: Review

February 21, 2024

This Is Me... Now: A Love Story Review: Jennifer Lopez Fictionalizes Reality for a Bonkers Cinematic Experience

February 14, 2024

The Taste of Things Is a Cinematic Meal to Savor: Review

February 9, 2024

- Album Streams

- Upcoming Releases

- Film Trailers

- TV Trailers

- Pop Culture

- Album Reviews

- Concert Reviews

- Festival Coverage

- Film Reviews

- Cover Stories

- Hometowns of Consequence

- Song of the Week

- Album of the Month

- Behind the Boards

- Dustin ‘Em Off

- Track by Track

- Top 100 Songs Ever

- Crate Digging

- Best Albums of 2023

- Best Songs of 2023

- Best Films of 2023

- Best TV Shows of 2023

- Top Albums of All Time

- Festival News

- Festival Outlook

- How to Get Tickets

- Photo Galleries

- Consequence Daily

- The Story Behind the Song

- Kyle Meredith

- Stanning BTS

- In Defense of Ska

- Good for a Weekend

- Consequence UNCUT

- The Spark Parade

- Beyond the Boys Club

- Going There with Dr. Mike

- The What Podcast

- Consequence Uncut

- Behind the Boys Club

- Two for the Road

- 90 Seconds or Less

- Battle of the Badmate

- Video Essays

- News Roundup

- First Time I Heard

- Mining Metal

Theme Weeks

- Industrial Week

- Marvel Week

- Disney Week

- Foo Fighters Week

- TV Theme Song Week

- Sex in Cinema Week

Follow Consequence

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy . We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

‘I Am Not Your Negro’ Review: Samuel L. Jackson Brings James Baldwin to Life in the Year’s Most Important Oscar Nominee

- Share on Facebook

- Share to Flipboard

- Share on LinkedIn

- Show more sharing options

- Submit to Reddit

- Post to Tumblr

- Print This Page

- Share on WhatsApp

There’s a remarkable cut in the opening minutes of Raoul Peck ’s “ I Am Not Your Negro ” that instantly transforms this insightful cinematic essay into the most important movie of the year so far.

It’s the late 60’s, and James Baldwin appears on “The Dick Cavett Show” to explain his views on black life in America. “The real question,” he says, “is what’s going to happen to this country?” Peck abruptly shifts to the present, assembling a collage of images from black protests against police violence, set to the boisterous rhythms of Buddy Guy’s “Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues.” That complex fusion of times, places and feelings yields an angry rallying cry that also functions as a lamentation of historical struggle, and it continues for the next 90 minutes. Peck doesn’t just resurrect Baldwin’s words from a contemporary perspective; he reignites their sense of purpose.

READ MORE: Ava DuVernay Meets Raoul Peck: How Black Narratives Collide In Two New Documentaries — NYFF

“I Am Not Your Negro” operates on many levels at once: It’s not only a fresh vessel for Baldwin’s own analysis of black life in America, but a platform for his assessment of other great thinkers who informed his views.

Peck, an undervalued Hatian filmmaker who has shifted between narrative and documentary projects for nearly 30 years, uses a remarkable foundation for this sweeping exploratory piece: a 30-page manuscript Baldwin wrote in 1979, as part of an uncompleted book project that delved into the lives of Medger Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. All three activists died before they turned 40; Baldwin worked alongside, then outlived, all of them.

“I Am Not Your Negro” is currently an Oscar nominee for best documentary (it received an awards qualifying run in late 2016, but opens in wider release this week), alongside “O.J.: Made in America” and “13TH,” with which it shares some concerns. This trio of moves present a complex statement on the evolution of racial barriers that have plagued the country over the past century, and the impulses that keep them in place, but “I Am Not Your Negro” casts the widest net. It breezes through Evers’ galvanizing activism, King’s calls for peace and Malcolm X’s calls for violence without favoring any of their approaches, instead finding a fluid connection between the sources of all three perspectives. From Baldwin’s perspective, such outspoken strategies elucidated the collective alienation of black America in a white society reared on groupthink.

There are moments when Peck attempts to express too many ideas at once, risking the possibility of muddling the clarity of Baldwin’s prose. More often than not, however, he delivers a grandiose statement on African American identity and the feelings of marginalization that have coexisted with it.

When Baldwin himself doesn’t appear in occasional clips, Samuel L. Jackson voices the writer in a recurring narration, pulling back on the hyperbolic Samuel L. Jackson cadences that have become a national punchline to give Baldwin a quiet, meditative presence throughout. Peck’s ample use of archival imagery alongside contemporary voices recalls “The Black Power Mixtape,” which provided a similar overview of imagery from the civil rights era in a modern context.

But “I Am Not Your Negro” goes beyond the limitations of a historical rumination, fusing past and present into a fascinating statement on national identity. “The story of the negro in America is the story of America,” Baldwin states, and Peck proves it, with a nonlinear approach that pairs pivotal moments with fictional representations to show how even the absence of black identity in popular culture invokes its struggles. Despite their different approaches, Evers, King and Malcolm X all tap into the disconnect between the notion of progress and the ignorance of a white-dominated society incapable of comprehending the frustrations of other races.

READ MORE: ‘I Am Not Your Negro’ Teaser Trailer Draws Direct Line From Civil Rights Movement to #BlackLivesMatter

Within the confines of a five-minute stretch, he veers from clips of Rodney King riots to Ferguson, Billy Wilder’s “Love in the Afternoon” and Gus Van Sant’s “Elephant” — with Jackson’s whispered narration as the key linking device — addressing both the frustration driving black activism and the broader systematic dysfunction that has marginalized issues of race in society. Peck’s dazzling approach never slows down, but maintains a clarity of vision that’s enthralling and provocative without turning into didacticism.

By the end of “I Am Not Your Negro,” Baldwin’s words have transcended the boundaries of their era and become timeless, functioning as both a celebration of cultural survival and a warning that the battle for its survival won’t stop anytime soon. “Not everything that is faced can be changed,” Baldwin writes. “But nothing can be changed until it is faced.” Peck’s great accomplishment with this mesmerizing achievement is that he pays homage to his subject with a work in tune with that call to action.

“I Am Not Your Negro” opens in limited release on February 3.

Stay on top of the latest breaking film and TV news! Sign up for our Email Newsletters here .

Most Popular

You may also like.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

I Am Not Your Negro review – astonishing portrait of James Baldwin's civil rights fight

Raoul Peck dramatises the author’s memoir of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr and Medgar Evers, in this vivid and vital documentary

R aoul Peck’s outstanding, Oscar-nominated documentary is about the African American activist and author James Baldwin, author of Go Tell It on the Mountain and The Fire Next Time . Peck dramatises Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript Remember This House, his personal memoir of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr and civil rights activist Medgar Evers, murdered by a segregationist in 1963 . Baldwin re-emerges as a devastatingly eloquent speaker and public intellectual; a figure who deserves his place alongside Edward Said, Frantz Fanon or Gore Vidal.

Peck puts Samuel L Jackson’s steely narration of Baldwin’s words up against a punchy montage of footage from the Jim Crow to the Ferguson eras, and a fierce soundtrack. (It’s incidentally a great use of Buddy Guy’s Damn Right I’ve Got the Blues , which never sounded so angry or political.) There is a marvellous clip of Baldwin speaking at the Cambridge Union Society, and another on the Dick Cavett Show – the host looking sick with nerves, perhaps because he was about to bring on a conservative intellectual for balance, whom Baldwin would politely trounce.

Baldwin has a compelling analysis of a traumatised “mirror stage” of culture that black people went through in 20th-century America. As kids, they would cheer and identify with the white heroes and heroines of Hollywood culture; then they would see themselves in the mirror and realise they were different from the white stars, and in fact more resembled the baddies and “Indians” they’d been booing.

The film shows Baldwin refusing to be drawn into the violence/non-violence difference of opinion between King and Malcolm X that mainstream commentators leaped on, and steadily maintaining his own critique – although I feel that Peck’s juxtaposition of Doris Day’s mooning and crooning with a lynch victim is a flourish that approximates Baldwin’s anger but not his elegance. There is a compelling section on Baldwin’s discussion of dramatist Lorraine Hansberry, author of A Raisin in the Sun. It is vivid, nutritious film-making.

- Documentary films

- James Baldwin

- Samuel L Jackson

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

I Am Not Your Negro

By Marina Cepeda

James Baldwin tells his story of America through the lives of his murdered friends– Medgar Evans, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. The film is based on an unfinished manuscript that interrogates why white Americans created the role of the “negro” and how it is a reflection of a larger moral apathy. Through archival footage of Baldwin’s interviews and speeches and archival footage of past and current protests, the documentary explores the history of racism in America, through the eyes of a witness. The film challenges the concept of the “Negro Problem,” instead raising it to be an “American Problem.”

- Nominated for Best Documentary Feature at the 89th Academy Awards

- Won the BAFTA Award for Best Documentary . [4] [5]

- Won the Toronto International Film Festival People’s Choice Award: Documentaries

- Won Best Documentary Film at Australian Film Critics Associatio n

- Won Best Documentary at British Academy Film Awards

- Won Audience Choice Award – Best Documentary Feature at 52nd Chicago International Film Festival

- Won Best Documentary Film at Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Log in Create an Account

I Am Not Your Negro: exploring racial inequality in America and beyond

10 Apr 2017 BY Elinor Walpole in Film Features

I Am Not Your Negro is a documentary essay that brings to vivid life the words of celebrated and influential writer James Baldwin (pictured above). Baldwin published articles and gave talks about race relations in the US throughout the civil rights movement, and was close to the central figures in the struggle for equality. In his unfinished book, Remember This House , Baldwin expands on the historical, political and personal impact of the murders of three prominent figures in the movement: Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers. In I Am Not Your Negro , director Raoul Peck uses this concept as a starting point to explore Baldwin's ideas and apply them to the present day.

Compiling a visual archive of America throughout the 20th century and up until today, Peck has selected his footage and images carefully to give maximum impact to Baldwin's words. Broken down into sections which tackle Baldwin's theories, the historical context, and Baldwin's own personal memories and observations of that time, the film asks broad questions about how - and why - America perpetuates racial inequality. While letting Baldwin speak for himself - both in narrative voiceover and with footage of talks and interviews - Raoul Peck picks up on Baldwin's concerns, and reasserts the case that change is not going to come until there is a fundamental shift in attitude; when America embraces all of its Americans. Actor Samuel L. Jackson narrates Baldwin's words in a way that feels intimate, but that doesn't imitate the writer's unique delivery; a deliberate choice that Peck explains to our young reporter Beattie in the interview below.

An extremely accomplished and persuasive speaker with an opinion firmly grounded in the human cost of America's growth as a nation, Baldwin's significance was felt worldwide - including in the UK. Footage of his talks is used in Big City Stories , an archive compilation curated by Black London's Film Heritage , and British race relations are again referenced in using Horace Ove's Pressure , an early film in the Black Cinema movement. Peck uses Pressure to illustrate the parallels between the British and American Black experience of discrimination, and the interpretation of interracial relationships, both on screen and in real life.

Sidney Poitier (who also features in Big City Stories as an inspiration to young Black Londoners for his role in To Sir With Love ) is discussed in I Am Not Your Negro as a Black romantic lead. Despite Poitier's obvious appeal, movie studios at the time were only concerned with white audiences, and were afraid to fully utilise Poitier's talents for fear of backlash, even in romantic dramas such as Guess Who's Coming to Dinner . Films featuring Black leads were considered a box office risk by Hollywood producers, and while the rise of Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte represented some progress, it was hobbled by the limited scope they were given as actors. Recent film Loving also expands on the issue of a dominant society's interference in the personal sphere, revealing a landmark case in which an interracial couple were legally persecuted for the 'crime' of being married.

I Am Not Your Negro is keen to explore where this fear comes from, with cinema itself coming under close scrutiny for perpetuating an idealised vision of the American Dream. Hollywood is implicated in forging an on-screen legend to gloss over the reality. In a recording from one of his talks, Baldwin describes his excitement at watching Westerns as a child, and the horrifying turning point when he realised that in these films, the person of colour was always the enemy, and the hero he'd been rooting for was a white man using violence to oppress them.

Peck builds on Baldwin's personal epiphany to reveal how the majority of American cinema shows an exclusively white experience, using clips of bright technicolour musicals - which embody naïve optimism and a world where everything is for the taking - juxtaposed against the horrifying realities of the Black experience. Peck uses imagery of police brutality and the resulting uprisings, such as the Watts Riots, or the witness footage of Oscar Grant (which was featured so poignantly in Fruitvale Station , a film which dramatises the events leading up to that incident) to make a stark point about the normalisation of violence against Black Americans.

In confronting an attitude of racial entitlement vs disenfranchisement, the film shares parallels with 3 1/2 Minutes, Ten Bullets , a heartrending documentary about the 2012 shooting of unarmed Black teenager Jordan Russell Davies by a middle-aged white man, in a row over the volume of his music. The Hard Stop , meanwhile, gives a British perspective on the use of extreme violence against Black people. An uncompromising documentary that explores the circumstances of the police shooting of Mark Duggan in 2011, the film presents Duggan as only the latest victim in a long history of violence borne out of prejudice.

As well as the arresting use of juxtaposition, Peck has also made more subtle edits to well-known images and footage to alter the impact of the visuals - for example, in the use of colour and black and white. In doing so, Peck appeals to the audience to interrogate what they see, and to consider whether the films they watch are fully representative of the human experience, or a perpetuation of fantasy. Contemporary films such as Dear White People and Get Out also encourage audiences to reflect on their own complicity in the status quo of race relations.

Despite the documentary's evidence highlighting the continuing race relations issues, James Baldwin's words and attitude do provide some hope. His matter-of-fact analysis of how the history of America has created this inequality also contains an appeal to acknowledge that Americans of all colours were involved in building the country up, and all have equal right to enjoy its successes. As Baldwin says, " the story of the negro in America is the story of America ". While " it is not a pretty story ", his words convey the kind of sense needed to challenge apathetic attitudes and irresponsible representations that perpetuate inequality.

Director Raoul Peck discusses I Am Not Your Negro

Elinor Walpole , Film Programmer

Elinor has a BA in English Literature from the University of Warwick. She has worked as Education and Community Officer for Picturehouse Cinemas, and as Outreach Coordinator for Human Rights Watch Film Festival.

This Article is part of: Film Features

You may also be interested in....

How 'Loving' depicts a quietly powerful battle for basic human rights

Jeff Nichols' new film tells the true story of an interracial couple's fight to maintain their marriage in the face of legal discrimination in 1950s America.

Reading time 6 mins

Black History Month

Black history month, 1 oct - 1 nov.

A selection of films looking at international representations of Black History across cinema.

Suitable for 7+

No. of films 24

Diversity on Film: Black Star Assembly

An assembly to shine a light on Black filmmakers and to inspire young people to tell stories of their own using film.

Suitable for 11+

Diversity is something to be celebrated and reflected in film - be it diversity of ethnicity, gender, disability, sexual orientation, or economic status.

Resources 76

Viewing 4 of 4 related items.

Into Film Clubs

Find out everything you need to know about starting an Into Film Club.

Want to write for us?

Get in touch with your article ideas for the News and Views section.

Contact Into Film

Advertisement

Supported by

Finally, a Screenplay by James Baldwin

- Share full article

By Salamishah Tillet

- Feb. 9, 2017

“I have never seen myself as a spokesman,” James Baldwin once said in an interview . “I am a witness. In the church in which I was raised, you were supposed to bear witness to the truth. Now, later on, you wonder what in the world the truth is, but you do know what a lie is.”

This notion of a witness — as a person who can distinguish between falsehoods and facts, myths and truths, and whose testimony about the past can transform the fate of another — is one of the most profound themes in James Baldwin’s work. But being both a writer of and witness to America’s complex and tumultuous history was Baldwin’s calling and curse: For it often meant trying to save a nation from racial ruin at the very same time that his friends and civil rights activists Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were being killed.

Baldwin’s confrontation with this dilemma is at the heart of the filmmaker Raoul Peck’s new Oscar-nominated documentary, “ I Am Not Your Negro ,” partly based on the unfinished Baldwin manuscript “Remember This House” given to Mr. Peck by Baldwin’s sister, Gloria Karefa-Smart. In a 1979 letter to his agent, Baldwin said the book would entail “exposing myself as one of the witnesses to the lives and deaths of their famous fathers,” a reference to the children of Evers, X and King, “and it means much, much more than that.”

There have been several documentaries featuring Baldwin as subject or narrator, including the 1982 film “ I Heard It Through the Grapevine ,” but “I Am Not Your Negro” is the first one shaped entirely by Baldwin’s words. You could say he was Mr. Peck’s collaborator, and indeed Baldwin is credited as the film’s sole writer, which is fitting for an author who had been fascinated by the movies all of his life.

In this way, Mr. Peck’s film is “the capstone, the crown of these documentaries,” said Richard Blint, a scholar at the Pratt Institute who is working on a project about James Baldwin and American cinema.

The film covers the five years in which those leaders were assassinated, but it also retells the history of the long 20th century and now 21st century through the lens of American race relations. Mr. Peck achieves this by using rare footage of Baldwin giving interviews and speeches in the 1960s, and even more impressive, by revealing how intimately tied the technologies of American film have always been to our country’s practices and policies of racial inequality.

Like Baldwin’s seamless shifts between personal anecdote and political analysis in his essays, Mr. Peck sets images of 1960s civil rights protests next to recent ones from the uprisings in Ferguson and Baltimore; uses footage of the 1965 Watts riots to interrupt hyper-patriotic clips from the 1960 United States Savings Bond promotional film, “ The Land We Love ”; and undercuts scenes from westerns valorizing Gary Cooper with excerpts from Baldwin’s Oxford debate, in which he confesses shock to discover “although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.”

“Baldwin has been with me all my life, all my conscious life,” Mr. Peck said in an interview. “He is someone I learned from very early on, someone who framed me, taught me how to think, to deconstruct stories, images, narratives, and I have used him all my life. He was never just an author — he was a witness for me.”

The filmmaker recalled how Baldwin’s writing directly affected his own way of seeing when his family moved to the Democratic Republic of Congo from Haiti when he was 8. “My whole imaginary world was filled with American movies, which for many people around the world is the dominant narrative,” he explained. “When I went to Congo, my image of Africa was of savages running in the jungle and a few white men who are civilized and trying to teach the natives how to be a human being.”

He paused: “But it hit me the second I put my feet on the tarmac in Congo, that I was told a totally false story that didn’t match what I’m now feeling and seeing. This capacity and privilege to be able to not only live through whatever you are in at the moment but also to have some distance and analyze whatever is happening to you is something that I read in Baldwin’s work.”

Mr. Peck relied heavily on “The Devil Finds Work,” a 1976 book-length essay in which Baldwin explored his intimate and vexed relationship as a consumer, critic and sometimes creator of American film. “I am fascinated by the movement on, and off, the screen,” Baldwin declares and shares his fascination at the age of 7 with “the straight, narrow, lonely back” of Joan Crawford in “ Dance, Fools, Dance .” Yet as much as the young Baldwin might have been seduced by the power of Hollywood, his older, writerly self sought to expose the racial fantasies and racist stereotypes that the industry was built on and that were endlessly reproduced around the world.

Recalling films that celebrated minstrel-like performances from Mantan Moreland , Willie Best , Lincoln Perry (a.k.a. Stepin Fetchit) and other African-American actors, Baldwin wrote: “It seemed to me that they lied about the world I knew, and debased it, and certainly I did not know anybody like them — as far as I could tell.”

Baldwin contrasted them with actors like Ethel Waters , Paul Robeson and especially Sidney Poitier , whose performances often moved “miraculously beyond the confines of the script” and offered more realistic representations of black life that they “smuggled like contraband in a maudlin tale.”

Crediting Baldwin as the writer of “I Am Not Your Negro” might be something he would have appreciated. Despite his critique of Hollywood, Baldwin moved to Los Angeles in 1968 to write a screenplay about Malcolm X. The experience was frustrating. Baldwin’s relationship with Columbia Pictures became so strained after the studio hired Arnold Perl to rewrite major sections of the script that Baldwin abandoned the project.

Baldwin later reflected, “The adventure remained very painfully in my mind, and indeed, was to shed a certain light for me on the adventure occurring through the American looking-glass.” Baldwin would publish his script as “One Day When I Was Lost” in 1972, but Perl’s version was sold to Warner Bros. and eventually became the basis for Spike Lee’s 1992 biopic, “Malcolm X.” Keeping in the spirit of Baldwin’s rejection of that script, his estate refused to put his name on the film’s credits.

“Baldwin’s script experimented with the genre of the biopic,” said Brian Norman, a professor of English at Loyola University Maryland who has written about the screenplay. “He gave a strangely disconnected, nonchronological vision of Malcolm X as endlessly reinventing himself, as being ever-present and ever relevant.“

And this is one of the greatest gifts Mr. Peck’s film gives back to Baldwin and to a contemporary audience — “I Am Not Your Negro” aims to approximate Baldwin’s aesthetic style and critical sensibility in cinematic form. The result is both a profound meditation on Baldwin’s vision and a metahistory of American movies that demands that we all become witnesses who choose to either end American racism or be swallowed up whole.

Our Coverage of the 2024 Oscars

The 96th academy awards were presented on march 10 in los angeles..

Our Critics’ Take: The Oscars were torn between the golden past and the thorny present. But to our critics Manohla Dargis and Alissa Wilkinson, the show mostly worked .

A ‘Just Ken’ Spectacle: In one of the most anticipated and exuberant moments of Oscar night , Ryan Gosling took the stage to perform “ I’m Just Ken ” from “Barbie.”

Cillian Murphy’s Career: If you’re looking to expand your knowledge of the Irish actor’s work after his now Oscar-winning performance as the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, here are some excellent options .

Bro-Brooches: This year, several male stars wore baubles more often associated with granny’s jewel box than Hollywood heartthrobs.

Inside the After Parties: Here’s what we saw at the Governors Ball and Vanity Fair’s party , where the famous (and the fame-adjacent) celebrated into the night.

“I Am Not Your Negro”: A Reflection

By Rebecca Murdock

I walked into the empty auditorium, my footsteps echoing off the walls around me. I was 45 minutes early and hoping to do some reading before the event began. Looking up at the movie-theater style seats, I realized I could sit anywhere, but suddenly felt the need to pick my seat very intentionally. Too far up, and I might seem like I didn’t care enough. Too close, and I could look pretentious, as if I thought this was for me. I needed to be somewhere where I could observe and learn, but still be out of the way. I was already out of place, being white at a Black Student Association event, and I didn’t need to make any careless mistakes.

Since you’re reading this essay, would you become an Adventist Today supporter?

The BSA officers arrived and set out dinner for everyone, as the rest of the audience trickled in. I was starkly aware of the fact that I was still the only white person in the room. Soon, the documentary started and I braced myself for the flood of white guilt that I expected to ensue. But instead, my overwhelming feeling throughout the film was awe, as I was taken on a fascinating and terrible journey through a version of American history I’d never experienced. Not one I’d resisted, but one that simply hadn’t made its way into my purview.

The idea that we all experience reality differently wasn’t new to me, as I’d poured over articles on confirmation bias, social constructionism, and communication theory.

But this was different.

I’d sympathized with the black struggle, but I’d never felt it in my own soul before. To see the same history that had bolstered my sense of heritage, tear down someone else’s, felt as if I’d believed part of a lie my whole life. To hear James Baldwin talk about cheering for John Wayne shooting down the Indians on TV as a child, only to grow older and realize that he, himself, represented the Indians, a threat to white America, was sobering. To see “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner,” not as a progressive film, but as an orchestrated manuscript, dictating how black people must act, dress, and express themselves if they were to be tolerated by white America, was grievous. But to watch working black men walk by the caskets of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, or Martin Luther King, Jr. and see the look of hopelessness on their faces as they walked away was unbearable. Because here was where the fate of these black men was most clear – that they could either continue to endure being treated as less than human, or that they could speak up in protest, only to be permanently silenced.

Baldwin speaks about blacks and whites and the hatred they are perceived to have between each other. “The root of the black man’s hatred is rage, and he does not so much hate white men as simply wants them out of his way, and more than that, out of his children’s way.” As Baldwin later says, he simply wanted to go about his interests, passions, and work projects without the social terror of constantly looking over his shoulder, expecting harassment or danger. And it was not until his move from America to Paris that he finally experienced a reality in which that way of peaceful living was somewhat possible.

At the end of the film, Baldwin takes an interesting shift toward contemplating the psychological effects of oppression on the oppressors, themselves.

“I know very well,” he says. “That my ancestors had no desire to come to this place. But neither did the ancestors of the people who became white, and who require of my captivity a song. They require a song of me, less to celebrate my captivity than to justify their own.”

He laments the impoverished moral character that results from the subjugation of “other.”

“I have always been struck, in America, by an emotional poverty so bottomless, and a terror of human life, of human touch, so deep, that virtually no American appears able to achieve any viable, organic connection between his public stance and his private life. This failure of the private life has always had the most devastating effect on American public conduct, and on black-white relations. If Americans were not so terrified of their private selves, they would never have become so dependent on what they call ‘The Negro Problem’.”

He asserts that white America would do well to do some soul searching as to why the use of a Negro in society was needed in the first place. What function this type of social order was created to fulfill. “And,” he concludes. “The future of our country depends on that… whether or not it’s able to ask that question.”

As the movie credits rolled over the screen, I puzzled over how any marginalized group should properly speak up about unfair treatment, without being cast in the role of oppressor, themselves. Since three different black men with three different philosophies were all assassinated for trying to alert white America of their plight, what approach then would finally have “merited” and received such long-awaited validation? If any at all?

I recalled a moment of hope in the film, a part toward the end, where Baldwin references an old, 1958 movie called “The Defiant Ones,” where a black man and a white man are chained together on a chain gang and spend the first parts of the movie fighting each other vehemently. It is not until they resign themselves to the fact that they are in it together that they begin to understand that their future as a unit depends on their joint partnership.

Similarly, Baldwin proposes that our future in America, for both black and white people, is dependent upon our working together. And it is not until we spend time listening and understanding each other’s experiences of history that we can avoid repeating the tragedies that our ignorance has been accomplice to.

While even liberal, Millennial, America has been focused on their own perspective and tiptoeing around black people on eggshells, hoping not to upset anyone or get called a “racist,” the majority of black America has simply been trying to create enough structure and safety in this country to go about their daily business in peace.

A luxury I’ve known for most of my life in America, and taken for granted.

Instead of avoiding the uncomfortable truths and assuming that we should stay out of it as a polite courtesy; I would encourage my white brothers and sisters to pay the higher courtesy of attending more BSA events, watching more documentaries, and taking ownership to educate yourselves further on the united, and sometimes divided, historical realities that form the foundation of the country we call home.

Related Posts

Dear lord, forgive….

Why Jesus Wept for Jerusalem

Commentary , News

He is not here—he has risen, just as he said.

Subscribe for free to the adventist today magazine..

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

I Am Not Your Negro

34 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Front Matter

Part 1: “Paying My Dues”

Part 2: “Heroes”

Part 3: “Witness”

Part 4: “Purity”

Part 5: “Selling the Negro”

Part 6: “I Am Not A N*****”

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

I Am Not Your Negro by James Baldwin and Raoul Peck is an accompanying text to the 2016 documentary of the same name, directed by Peck. The documentary was released to critical acclaim. It won Best Documentary award at the BAFTA Film Awards and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. The text is essentially a transcript of the film, incorporating excerpts of interviews, television features, and films.

I Am Not Your Negro is based on an unfinished book by Baldwin titled Remember This House in which he intended to explore American racism by focusing on the murders of Martin Luther King, Jr. , Medgar Evers , and Malcolm X—three leaders in the American civil rights movement who Baldwin knew and loved. Baldwin never finished his manuscript, only leaving behind thirty pages of notes. Peck approached the project by attempting to construct a finished draft of Remember This House based on Baldwin’s notes and letters. The resulting text makes up I Am Not Your Negro.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,350+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,950+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

This guide quotes and obscures Baldwin’s use of the n-word, the construction of which is one topic within his critique of racism in America.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By James Baldwin

Another Country

James Baldwin

A Talk to Teachers

Blues for Mister Charlie

Giovanni's Room

Going To Meet The Man

Go Tell It on the Mountain

If Beale Street Could Talk

If Black English Isn't a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?

Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son

No Name in the Street

Notes of a Native Son

Sonny's Blues

The Amen Corner

The Fire Next Time

The Rockpile

Featured Collections

Black Arts Movement

View Collection

Books on Justice & Injustice

Existentialism

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines