Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

14.1 Four Methods of Delivery

Learning objectives.

- Differentiate among the four methods of speech delivery.

- Understand when to use each of the four methods of speech delivery.

Maryland GovPics – House of Ruth Luncheon – CC BY 2.0.

The easiest approach to speech delivery is not always the best. Substantial work goes into the careful preparation of an interesting and ethical message, so it is understandable that students may have the impulse to avoid “messing it up” by simply reading it word for word. But students who do this miss out on one of the major reasons for studying public speaking: to learn ways to “connect” with one’s audience and to increase one’s confidence in doing so. You already know how to read, and you already know how to talk. But public speaking is neither reading nor talking.

Speaking in public has more formality than talking. During a speech, you should present yourself professionally. This doesn’t mean you must wear a suit or “dress up” (unless your instructor asks you to), but it does mean making yourself presentable by being well groomed and wearing clean, appropriate clothes. It also means being prepared to use language correctly and appropriately for the audience and the topic, to make eye contact with your audience, and to look like you know your topic very well.

While speaking has more formality than talking, it has less formality than reading. Speaking allows for meaningful pauses, eye contact, small changes in word order, and vocal emphasis. Reading is a more or less exact replication of words on paper without the use of any nonverbal interpretation. Speaking, as you will realize if you think about excellent speakers you have seen and heard, provides a more animated message.

The next sections introduce four methods of delivery that can help you balance between too much and too little formality when giving a public speech.

Impromptu Speaking

Impromptu speaking is the presentation of a short message without advance preparation. Impromptu speeches often occur when someone is asked to “say a few words” or give a toast on a special occasion. You have probably done impromptu speaking many times in informal, conversational settings. Self-introductions in group settings are examples of impromptu speaking: “Hi, my name is Steve, and I’m a volunteer with the Homes for the Brave program.” Another example of impromptu speaking occurs when you answer a question such as, “What did you think of the documentary?”

The advantage of this kind of speaking is that it’s spontaneous and responsive in an animated group context. The disadvantage is that the speaker is given little or no time to contemplate the central theme of his or her message. As a result, the message may be disorganized and difficult for listeners to follow.

Here is a step-by-step guide that may be useful if you are called upon to give an impromptu speech in public.

- Take a moment to collect your thoughts and plan the main point you want to make.

- Thank the person for inviting you to speak.

- Deliver your message, making your main point as briefly as you can while still covering it adequately and at a pace your listeners can follow.

- Thank the person again for the opportunity to speak.

- Stop talking.

As you can see, impromptu speeches are generally most successful when they are brief and focus on a single point.

Extemporaneous Speaking

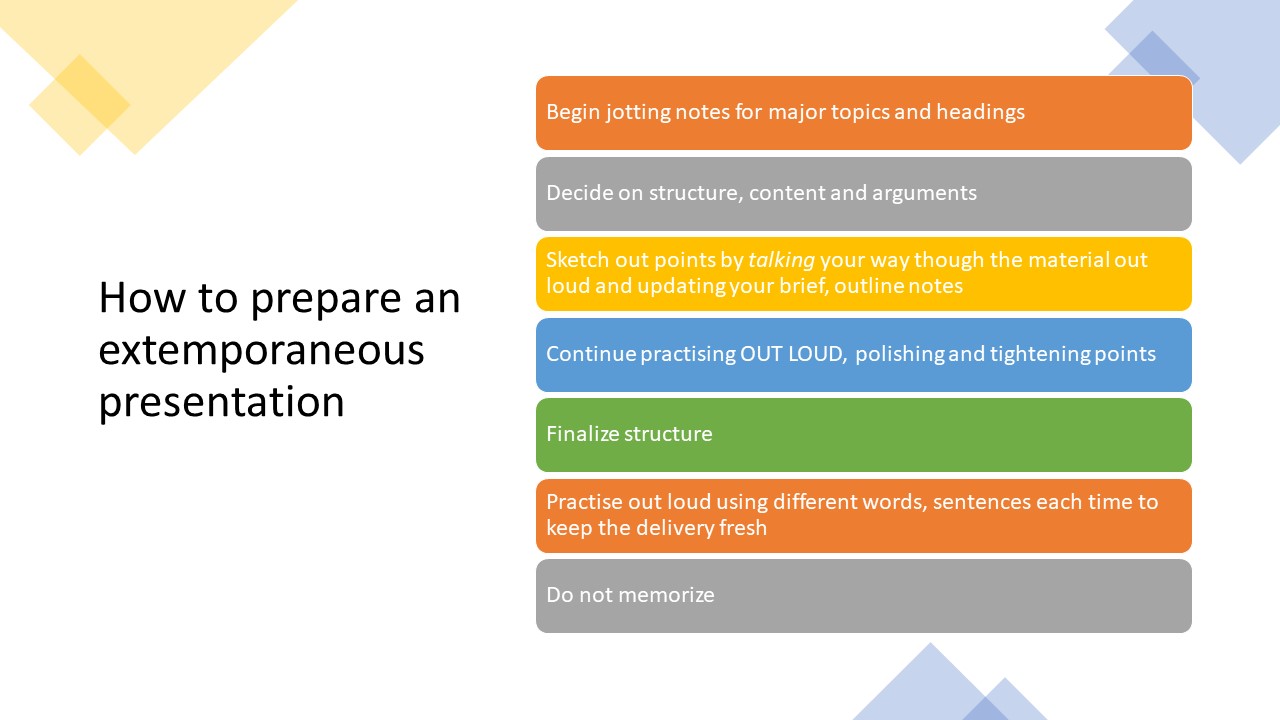

Extemporaneous speaking is the presentation of a carefully planned and rehearsed speech, spoken in a conversational manner using brief notes. By using notes rather than a full manuscript, the extemporaneous speaker can establish and maintain eye contact with the audience and assess how well they are understanding the speech as it progresses. The opportunity to assess is also an opportunity to restate more clearly any idea or concept that the audience seems to have trouble grasping.

For instance, suppose you are speaking about workplace safety and you use the term “sleep deprivation.” If you notice your audience’s eyes glazing over, this might not be a result of their own sleep deprivation, but rather an indication of their uncertainty about what you mean. If this happens, you can add a short explanation; for example, “sleep deprivation is sleep loss serious enough to threaten one’s cognition, hand-to-eye coordination, judgment, and emotional health.” You might also (or instead) provide a concrete example to illustrate the idea. Then you can resume your message, having clarified an important concept.

Speaking extemporaneously has some advantages. It promotes the likelihood that you, the speaker, will be perceived as knowledgeable and credible. In addition, your audience is likely to pay better attention to the message because it is engaging both verbally and nonverbally. The disadvantage of extemporaneous speaking is that it requires a great deal of preparation for both the verbal and the nonverbal components of the speech. Adequate preparation cannot be achieved the day before you’re scheduled to speak.

Because extemporaneous speaking is the style used in the great majority of public speaking situations, most of the information in this chapter is targeted to this kind of speaking.

Speaking from a Manuscript

Manuscript speaking is the word-for-word iteration of a written message. In a manuscript speech, the speaker maintains his or her attention on the printed page except when using visual aids.

The advantage to reading from a manuscript is the exact repetition of original words. As we mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, in some circumstances this can be extremely important. For example, reading a statement about your organization’s legal responsibilities to customers may require that the original words be exact. In reading one word at a time, in order, the only errors would typically be mispronunciation of a word or stumbling over complex sentence structure.

However, there are costs involved in manuscript speaking. First, it’s typically an uninteresting way to present. Unless the speaker has rehearsed the reading as a complete performance animated with vocal expression and gestures (as poets do in a poetry slam and actors do in a reader’s theater), the presentation tends to be dull. Keeping one’s eyes glued to the script precludes eye contact with the audience. For this kind of “straight” manuscript speech to hold audience attention, the audience must be already interested in the message before the delivery begins.

It is worth noting that professional speakers, actors, news reporters, and politicians often read from an autocue device, such as a TelePrompTer, especially when appearing on television, where eye contact with the camera is crucial. With practice, a speaker can achieve a conversational tone and give the impression of speaking extemporaneously while using an autocue device. However, success in this medium depends on two factors: (1) the speaker is already an accomplished public speaker who has learned to use a conversational tone while delivering a prepared script, and (2) the speech is written in a style that sounds conversational.

Speaking from Memory

Memorized speaking is the rote recitation of a written message that the speaker has committed to memory. Actors, of course, recite from memory whenever they perform from a script in a stage play, television program, or movie scene. When it comes to speeches, memorization can be useful when the message needs to be exact and the speaker doesn’t want to be confined by notes.

The advantage to memorization is that it enables the speaker to maintain eye contact with the audience throughout the speech. Being free of notes means that you can move freely around the stage and use your hands to make gestures. If your speech uses visual aids, this freedom is even more of an advantage. However, there are some real and potential costs. First, unless you also plan and memorize every vocal cue (the subtle but meaningful variations in speech delivery, which can include the use of pitch, tone, volume, and pace), gesture, and facial expression, your presentation will be flat and uninteresting, and even the most fascinating topic will suffer. You might end up speaking in a monotone or a sing-song repetitive delivery pattern. You might also present your speech in a rapid “machine-gun” style that fails to emphasize the most important points. Second, if you lose your place and start trying to ad lib, the contrast in your style of delivery will alert your audience that something is wrong. More frighteningly, if you go completely blank during the presentation, it will be extremely difficult to find your place and keep going.

Key Takeaways

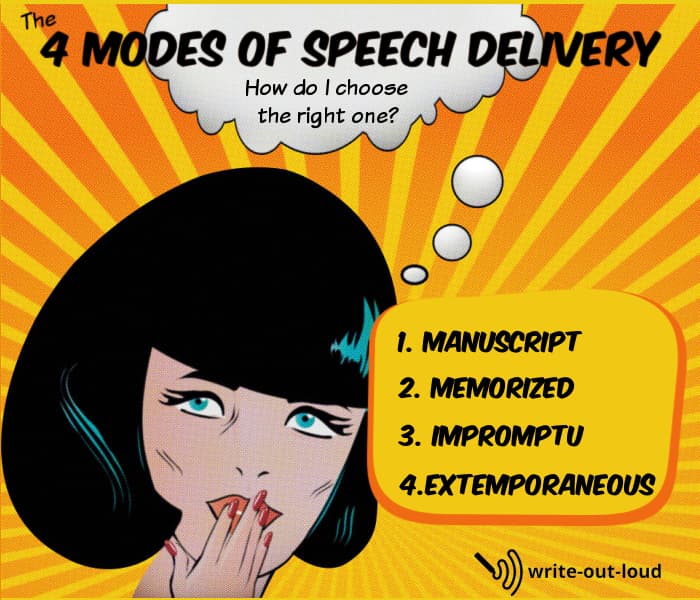

- There are four main kinds of speech delivery: impromptu, extemporaneous, manuscript, and memorized.

- Impromptu speaking involves delivering a message on the spur of the moment, as when someone is asked to “say a few words.”

- Extemporaneous speaking consists of delivering a speech in a conversational fashion using notes. This is the style most speeches call for.

- Manuscript speaking consists of reading a fully scripted speech. It is useful when a message needs to be delivered in precise words.

- Memorized speaking consists of reciting a scripted speech from memory. Memorization allows the speaker to be free of notes.

- Find a short newspaper story. Read it out loud to a classroom partner. Then, using only one notecard, tell the classroom partner in your own words what the story said. Listen to your partner’s observations about the differences in your delivery.

- In a group of four or five students, ask each student to give a one-minute impromptu speech answering the question, “What is the most important personal quality for academic success?”

- Watch the evening news. Observe the differences between news anchors using a TelePrompTer and interviewees who are using no notes of any kind. What differences do you observe?

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Delivering a Speech

Introduction

9.1 Managing Public Speaking Anxiety

Sources of speaking anxiety.

Aside from the self-reported data in national surveys that rank the fear of public speaking high for Americans, decades of research conducted by communication scholars shows that communication apprehension is common among college students (Priem & Solomon, 2009). Communication apprehension (CA) is fear or anxiety experienced by a person due to real or perceived communication with another person or persons. CA is a more general term that includes multiple forms of communication, not just public speaking. Seventy percent of college students experience some CA, which means that addressing communication anxiety in a class like the one you are taking now stands to benefit the majority of students (Priem & Solomon, 2009). Think about the jitters you get before a first date, a job interview, or the first day of school. The novelty or uncertainty of some situations is a common trigger for communication anxiety, and public speaking is a situation that is novel and uncertain for many.

Public speaking anxiety is a type of CA that produces physiological, cognitive, and behavioral reactions in people when faced with a real or imagined presentation (Bodie, 2010). Physiological responses to public speaking anxiety include increased heart rate, flushing of the skin or face, and sweaty palms, among other things. These reactions are the result of natural chemical processes in the human body. The fight or flight instinct helped early humans survive threatening situations. When faced with a ferocious saber-toothed tiger, for example, the body released adrenaline, cortisol, and other hormones that increased heart rate and blood pressure to get more energy to the brain, organs, and muscles in order to respond to the threat. We can be thankful for this evolutionary advantage, but our physiology has not caught up with our new ways of life. Our body does not distinguish between the causes of stressful situations, so facing down an audience releases the same hormones as facing down a wild beast.

Cognitive reactions to public speaking anxiety often include intrusive thoughts that can increase anxiety: “People are judging me,” “I’m not going to do well,” and “I’m going to forget what to say.” These thoughts are reactions to the physiological changes in the body but also bring in the social/public aspect of public speaking in which speakers fear being negatively judged or evaluated because of their anxiety. The physiological and cognitive responses to anxiety lead to behavioral changes. All these thoughts may lead someone to stop their speech and return to their seat or leave the classroom. Anticipating these reactions can also lead to avoidance behavior where people intentionally avoid situations where they will have to speak in public.

Addressing Public Speaking Anxiety

While we cannot stop the innate physiological reactions related to anxiety from occurring, we do have some control over how we cognitively process them and the behaviors that result. Research on public speaking anxiety has focused on three key ways to address this common issue: systematic desensitization, cognitive restructuring, and skills training (Bodie,2010).

Although systematic desensitization may sound like something done to you while strapped down in the basement of a scary hospital, it actually refers to the fact that we become less anxious about something when we are exposed to it more often (Bodie, 2010). As was mentioned earlier, the novelty and uncertainty of public speaking is a source for many people’s anxiety. So becoming more familiar with public speaking by speaking more often can logically reduce the novelty and uncertainty of it.

Systematic desensitization can result from imagined or real exposure to anxiety-inducing scenarios. In some cases, an instructor leads a person through a series of relaxation techniques. Once relaxed, the person is asked to imagine a series of scenarios including speech preparation and speech delivery. This is something you could also try to do on your own before giving a speech. Imagine yourself going through the process of preparing and practicing a speech, then delivering the speech, then returning to your seat, which concludes the scenario. Aside from this imagined exposure to speaking situations, taking a communication course like this one is a great way to engage directly in systematic desensitization. Almost all students report that they have less speaking anxiety at the end of a semester than when they started, which is at least partially due to the fact they engaged with speaking more than they would have done if they were not taking the class.

Cognitive Restructuring

Cognitive restructuring entails changing the way we think about something. A first step in restructuring how we deal with public speaking anxiety is to cognitively process through our fears to realize that many of the thoughts associated with public speaking anxiety are irrational (Allen, Hunter & Donohue, 2009). For example, people report a fear of public speaking over a fear of snakes, heights, financial ruin, or even death. It’s irrational to think that the consequences of giving a speech in public are more dire than getting bit by a rattlesnake, falling off a building, or dying. People also fear being embarrassed because they mess up. Well, you cannot literally die from embarrassment, and in reality, audiences are very forgiving and overlook or do not even notice many errors that we, as speakers, may dwell on. Once we realize that the potential negative consequences of giving a speech are not as dire as we think they are, we can move on to other cognitive restructuring strategies.

Communication-orientation modification therapy (COM therapy) is a type of cognitive restructuring that encourages people to think of public speaking as a conversation rather than a performance (Motley, 2009). Many people have a performance-based view of public speaking. This can easily be seen in the language that some students use to discuss public speaking. They say that they “rehearse” their speech, deal with “stage fright,” then “perform” their speech on a “stage.” There is no stage at the front of the classroom; it is a normal floor. To get away from a performance orientation, we can reword the previous statements to say that they “practice” their speech, deal with “public speaking anxiety,” then “deliver” their speech from the front of the room. Viewing public speaking as a conversation also helps with confidence. After all, you obviously have some conversation skills, or you would not have made it to college. We engage in conversations every day. We do not have to write everything we are going to say out on a note card, we do not usually get nervous or anxious in regular conversations, and we are usually successful when we try. Even though we do not engage in public speaking as much, we speak to others in public all the time. Thinking of public speaking as a type of conversation helps you realize that you already have accumulated experiences and skills that you can draw from, so you are not starting from scratch.

Last, positive visualization is another way to engage in cognitive restructuring. Speaking anxiety often leads people to view public speaking negatively. They are more likely to judge a speech they gave negatively, even if it was good. They are also likely to set up negative self-fulfilling prophecies that will hinder their performance in future speeches. To use positive visualization, it is best to engage first in some relaxation exercises such as deep breathing or stretching, and then play through vivid images in your mind of giving a successful speech. Do this a few times before giving the actual speech. Students sometimes question the power of positive visualization, thinking that it sounds corny. Ask an Olympic diver what his or her coach says to do before jumping off the diving board and the answer will probably be “Coach says to image completing a perfect 10 dive.” Likewise a Marine sharpshooter would likely say his commanding officer says to imagine hitting the target before pulling the trigger. In both instances, positive visualization is being used in high-stakes situations. If it is good enough for Olympic athletes and snipers, it is good enough for public speakers.

Skills training is a strategy for managing public speaking anxiety that focuses on learning skills that will improve specific speaking behaviors. These skills may relate to any part of the speech-making process, including topic selection, research and organization, delivery, and self-evaluation. Skills training, like systematic desensitization, makes the public speaking process more familiar for a speaker, which lessens uncertainty. In addition, targeting specific areas and then improving on them builds more confidence, which can in turn lead to more improvement. Feedback is important to initiate and maintain this positive cycle of improvement. You can use the constructive criticism that you get from your instructor and peers in this class to target specific areas of improvement.

Self-evaluation is also an important part of skills training. Make sure to evaluate yourself within the context of your assignment or job and the expectations for the speech. Do not get sidetracked by a small delivery error if the expectations for content far outweigh the expectations for delivery. Combine your self-evaluation with the feedback from your instructor, boss, and/or peers to set specific and measurable goals and then assess whether or not you meet them in subsequent speeches. Once you achieve a goal, mark it off your list and use it as a confidence booster. If you do not achieve a goal, figure out why and adjust your strategies to try to meet it in the future.

Physical Relaxation Exercises

Suggestions for managing speaking anxiety typically address its cognitive and behavioral components, while the physical components are left unattended. While we cannot block these natural and instinctual responses, we can engage in physical relaxation exercises to counteract the general physical signs of anxiety caused by cortisol and adrenaline release, which include increased heart rate, trembling, flushing, high blood pressure, and speech disfluency.

Some breathing and stretching exercises release endorphins, which are your body’s natural antidote to stress hormones. Deep breathing is a proven way to release endorphins. It also provides a general sense of relaxation and can be done discretely, even while waiting to speak. In order to get the benefits of deep breathing, you must breathe into your diaphragm. The diaphragm is the muscle below your lungs that helps you breathe and stand up straight, which makes it a good muscle for a speaker to exercise. To start, breathe in slowly through your nose, filling the bottom parts of your lungs up with air. While doing this, your belly should pooch out. Hold the breath for three to five full seconds and then let it out slowly through your mouth. After doing this only a few times, many students report that they can actually feel a flooding of endorphins, which creates a brief “light-headed” feeling. Once you practice and are comfortable with the technique, you can do this before you start your speech, and no one sitting around you will even notice. You might also want to try this technique during other stressful situations. Deep breathing before dealing with an angry customer or loved one, or before taking a test, can help you relax and focus.

Stretching is another way to release endorphins. Very old exercise traditions like yoga, tai chi, and Pilates teach the idea that stretching is a key component of having a healthy mind and spirit. Exercise in general is a good stress reliever, but many of us do not have the time or willpower to do it. However, we can take time to do some stretching. Obviously, it would be distracting for the surrounding audience if a speaker broke into some planking or Pilates just before his or her speech. Simple and discrete stretches can help get the body’s energy moving around, which can make a speaker feel more balanced and relaxed. Our blood and our energy/ stress have a tendency to pool in our legs, especially when we are sitting.

Vocal Warm-Up Exercises

Vocal warm-up exercises are a good way to warm up your face and mouth muscles, which can help prevent some of the fluency issues that occur when speaking. Newscasters, singers, and other professional speakers use vocal warm-ups. I lead my students in vocal exercises before speeches, which also helps lighten the mood. We all stand in a circle and look at each other while we go through our warm-up list. For the first warm-up, we all make a motorboat sound, which makes everybody laugh. The full list of warm-ups follows and contains specific words and exercises designed to warm up different muscles and different aspects of your voice. After going through just a few, you should be able to feel the blood circulating in your face muscles more. It is a surprisingly good workout!

Top Ten Ways to Reduce Speaking Anxiety

Many factors contribute to speaking anxiety. There are also many ways to address it. The following is a list of the top ten ways to reduce speaking anxiety that I developed with my colleagues, which helps review what we have learned.

- Remember, you are not alone. Public speaking anxiety is common, so do not ignore it—confront it.

- Remember, you cannot literally “die of embarrassment.” Audiences are forgiving and understanding.

- Remember, it always feels worse than it looks.

- Take deep breaths. It releases endorphins, which naturally fight the adrenaline that causes anxiety.

- Look the part. Dress professionally to enhance confidence.

- Channel your nervousness into positive energy and motivation.

- Start your outline and research early. Better information = higher confidence.

- Practice and get feedback from a trusted source. (Do not just practice for your cat.)

- Visualize success through positive thinking.

- Prepare, prepare, prepare! Practice is a speaker’s best friend.

9.2 Delivery Methods and Practice Sessions

There are many decisions to make during the speech-making process. Making informed decisions about delivery can help boost your confidence and manage speaking anxiety. In this section, we will learn about the strengths and weaknesses of various delivery methods. We will also learn how to make the most of your practice sessions.

Delivery Methods

Different speaking occasions call for different delivery methods. While it may be acceptable to speak from memory in some situations, lengthy notes may be required in others. The four most common delivery methods are impromptu, manuscript, memorized, and extemporaneous.

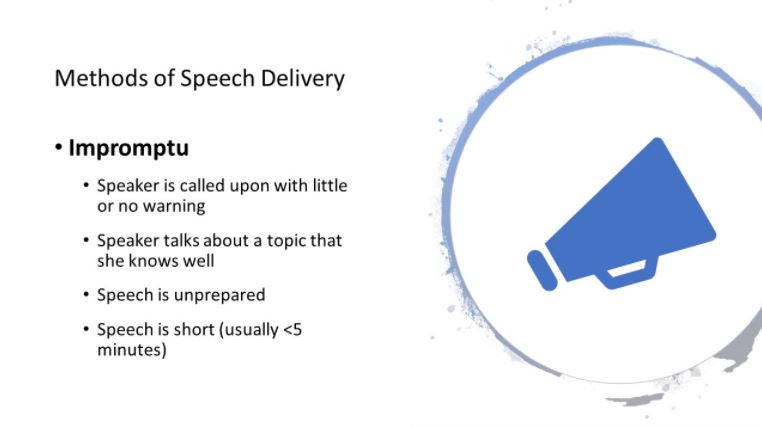

Impromptu Delivery

When using impromptu delivery , a speaker has little to no time to prepare for a speech (LibreTexts, 2021). This means there is little time for research, audience analysis, organizing, and practice. For this reason, impromptu speaking often evokes higher degrees of speaking anxiety than other delivery types. Although impromptu speaking arouses anxiety, it is also a good way to build public speaking skills. Using some of the exercises for managing speaking anxiety discussed earlier in this chapter can help a speaker manage the challenges of impromptu speaking (LibreTexts, 2021). Only skilled public speakers with much experience are usually able to “pull off” an impromptu delivery without looking unprepared. Otherwise, a speaker who is very familiar with the subject matter can sometimes be a competent impromptu speaker, because their expertise can compensate for the lack of research and organizing time.

When Mark Twain famously said, “It usually takes me more than three weeks to prepare a good impromptu speech,” he was jokingly pointing out the difficulties of giving a good impromptu speech, essentially saying that there is no such thing as a good impromptu speech, as good speeches take time to prepare. We do not always have the luxury of preparation, though. So when speaking impromptu, be brief, stick to what you know, and avoid rambling. Quickly organize your thoughts into an introduction, body, and conclusion. Try to determine three key ideas that will serve as the basis of your main points.

When would impromptu speaking be used? Since we have already started thinking of the similarities between public speaking and conversations, we can clearly see that most of our day-to-day interactions involve impromptu speaking. When your roommate asks you what your plans for the weekend are, you do not pull a few note cards out of your back pocket to prompt your response. This type of conversational impromptu speaking is not anxiety inducing because we are talking about our lives, experiences, or something with which we are familiar. This is also usually the case when we are asked to speak publicly with little to no advance warning.

For example, if you are at a meeting for work and you are representing the public relations department, a colleague may ask you to say a few words about a recent news story involving a public relations misstep of a competing company. In this case, you are being asked to speak on the spot because of your expertise. A competent communicator should anticipate instances like this when they might be asked to speak. Of course, being caught completely off guard or being asked to comment on something unfamiliar to you creates more anxiety. In such cases, do not pretend to know something you do not, as that may come back to hurt you later. You can usually mention that you do not have the necessary background information at that time but will follow up later with your comments.

Manuscript Delivery

Speaking from a written or printed document that contains the entirety of a speech is known as manuscript delivery . Manuscript delivery can be the best choice when a speech has complicated information and/or the contents of the speech are going to be quoted or published (LibreTexts, 2021). Despite the fact that most novice speakers are not going to find themselves in that situation, many are drawn to this delivery method because of the security they feel with having everything they are going to say in front of them. Unfortunately, the security of having every word you want to say at your disposal translates to a poorly delivered and unengaging speech (LibreTexts, 2021). Even with every word written out, speakers can still have fluency hiccups and verbal fillers as they lose their place in the manuscript or trip over their words. The alternative, of course, is that a speaker reads the manuscript the whole time, effectively cutting himself or herself off from the audience. One way to make a manuscript delivery more engaging is to use a teleprompter. Almost all politicians who give televised addresses use them.

To make the delivery seem more natural, print the speech out in a larger-than-typical font, triple-space between lines so you can easily find your place, use heavier-than-normal paper so it is easy to pick up and turn the pages as needed, and use a portfolio so you can carry the manuscript securely.

Memorized Delivery

Completely memorizing a speech and delivering it without notes is known as memorized delivery (LibreTexts, 2021). Some students attempt to memorize their speech because they think it will make them feel more confident if they do not have to look at their notes; however, when their anxiety level spikes at the beginning of their speech and their mind goes blank for a minute, many admit they should have chosen a different delivery method. When using any of the other delivery methods, speakers still need to rely on their memory. An impromptu speaker must recall facts or experiences related to their topic, and speakers using a manuscript want to have some of their content memorized so they do not read their entire speech to their audience. The problem with memorized delivery overall is that it puts too much responsibility on our memory, which we all know from experience is fallible (LibreTexts, 2021).

Even with much practice, our memories can fail. If you do opt to use memorized delivery, make sure you have several “entry points” determined, so you can pick up at spots other than the very beginning of a speech if you lose your place and have to start again. Memorized delivery is very useful for speakers who are going to be moving around during a speech when carrying notes would be burdensome. I only recommend memorized delivery in cases where the speech is short (only one to two minutes), the speech is personal (like a brief toast), or the speech will be repeated numerous times (like a tour guide’s story), and even in these cases, it may be perfectly fine to have notes. Many students think that their anxiety and/or delivery challenges will vanish if they just memorize their speech only to find that they are more anxious and have more problems.

Extemporaneous Delivery

Extemporaneous delivery entails memorizing the overall structure and main points of a speech and then speaking from keyword/key-phrase notes (LibreTexts, 2021). This delivery mode brings together many of the strengths of the previous three methods. Since you only internalize and memorize the main structure of a speech, you do not have to worry as much about the content and delivery seeming stale. Extemporaneous delivery brings in some of the spontaneity of impromptu delivery but still allows a speaker to carefully plan the overall structure of a speech and incorporate supporting materials that include key facts, quotations, and paraphrased information (LibreTexts, 2021). You can also more freely adapt your speech to fit various audiences and occasions, since not every word and sentence is predetermined. This can be especially beneficial when you deliver a speech multiple times.

When preparing a speech that you will deliver extemporaneously, you will want to start practicing your speech early and then continue to practice as you revise your content. Investing quality time and effort into the speech-outlining process helps with extemporaneous delivery. As you put together your outline, you are already doing the work of internalizing the key structure of your speech. Read parts of your outline aloud as you draft them to help ensure they are written in a way that makes sense and is easy for you to deliver.

By the time you complete the formal, full-sentence outline, you should have already internalized much of the key information in your speech. Now, you can begin practicing with the full outline. As you become more comfortable with the content of your full outline, start to convert it into your speaking outline. Take out information that you know well and replace it with a keyword or key phrase that prompts your memory. You will probably want to leave key quotes, facts, and other paraphrased information, including your verbal source citation information, on your delivery outline so you make sure to include it in your speech. Once you’ve converted your full outline into your speaking outline, practice it a few more times, making sure to take some time between each practice session so you don’t inadvertently start to memorize the speech word for word. The final product should be a confident delivery of a well-organized and structured speech that is conversational and adaptable to various audiences and occasions.

Practicing Your Speech

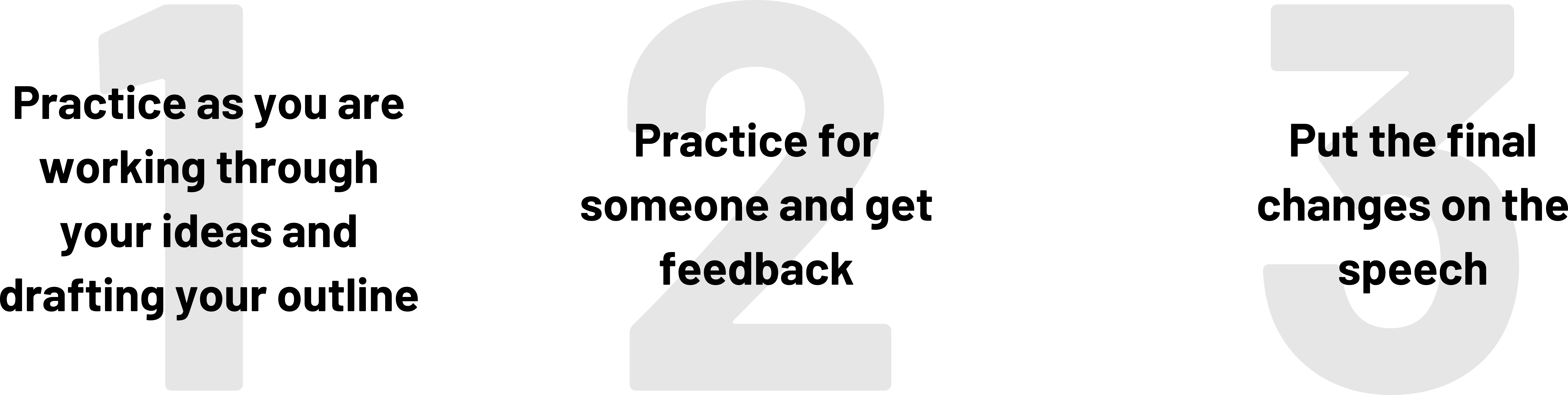

Practicing a speech is essential, and practice sessions can be more or less useful depending on how you approach them (Dlugan, 2008). There are three primary phases to the practice process. In the first phase, you practice as you are working through your ideas and drafting your outline. In the second, you practice for someone and get feedback (Dlugan, 2008). In the third, you put the final changes on the speech.

Start practicing your speech early, as you are working through your ideas, by reading sections aloud as you draft them into your working outline. This will help ensure your speech is fluent and sounds good for the audience. Start to envision the audience while you practice and continue to think about them throughout the practicing process. This will help minimize anxiety when you actually have them sitting in front of you. Once you have completed your research and finished a draft of your outline, you will have already practiced your speech several times, as you were putting it together. Now, you can get feedback on the speech as a whole.

You begin to solicit feedback from a trusted source in the second phase of practicing your speech (Dlugan, 2008). This is the most important phase of practicing, and the one that most speakers do not complete. Beginning speakers may be nervous to practice in front of someone. That is normal. However, review the strategies for managing anxiety discussed earlier in this chapter and try to face that anxiety. After all, you will have to face a full audience when you deliver the speech, so getting used to speaking in front of someone can only help you at this point. Choose someone who will give you constructive feedback on your speech. Before you practice for them, explain the assignment or purpose of the speech. When practicing for a classroom speech, you may even want to give the person the assignment guidelines or a feedback sheet that has some key things for them to look for. Ask them for feedback on content and delivery. Almost anyone is good at evaluating delivery, but it is more difficult to evaluate content. In addition, in most cases, the content of your speech will be account for more of your grade. Also, begin to time your speech at this point, so you can determine if it meets any time limits that you have.

In addition to practicing for a trusted source for feedback, you may want to audio or video record your speech (Dlugan, 2008). This can be useful because it provides an objective record that you can then compare with the feedback you got from your friend and to your own evaluation of your speech. The most important part of this phase is incorporating the feedback you receive into your speech. If you practice for someone, get feedback, and then do not do anything with the feedback, then you have wasted your time and theirs. Use the feedback to assess whether or not you met your speaking goals. Was your thesis supported? Was your specific purpose met? Did your speech conform to any time limits that were set? Based on your answers to these questions, you may need to make some changes to your content or delivery, so do not put this part of practicing off to the last minute. Once the content has been revised as needed, draft your speaking outline and move on to the next phase of practice.

During the third and final phase of practice, you are putting the final changes on your speech. You should be familiar with the content based on your early practice sessions. You have also gotten feedback and incorporated that feedback into the speech. Your practice sessions at this point should pre-create, as much as possible, the conditions in which you will be giving your speech. You should have your speaking outline completed so you can practice with it. It is important to be familiar with the content on your note cards or speaking outline so you will not need to rely on it so much during the actual delivery. You may also want to practice in the type of clothing you will be wearing on speech day. This can be useful if you are wearing something you do not typically wear—a suit for example—so you can see how it might affect your posture, gestures, and overall comfort level.

If possible, at least one practice session in the place you will be giving the speech can be very helpful; especially if it is a room you are not familiar with. Make sure you are practicing with any visual aids or technology you will use so you can be familiar with it and it does not affect your speech fluency. (Dlugan, 2008).Continue to time each practice round. If you are too short or too long, you will need to go back and adjust your content some more. Always adjust your content to fit the time limit; do not try to adjust your delivery. Trying to speed talk or stretch things out to make a speech faster or longer is a mistake that will ultimately hurt your delivery, which will hurt your credibility. The overall purpose of this phase of practicing is to minimize surprises that might throw you off on speech day.

Vocal Delivery

Vocal delivery includes components of speech delivery that relate to your voice. These include rate, volume, pitch, articulation, pronunciation, and fluency. Our voice is important to consider when delivering our speech for two main reasons. First, vocal delivery can help us engage and interest the audience. Second, vocal delivery helps ensure we communicate our ideas clearly.

Speaking for Engagement

We have all had the displeasure of listening to an unengaging speaker. Even though the person may care about his or her topic, an unengaging delivery that does not communicate enthusiasm will translate into a lack of interest for most audience members (Davis, 2021). Although a speaker can be visually engaging by incorporating movement and gestures, a flat or monotone vocal delivery can be sedating or even annoying. Incorporating vocal variety in terms of rate, volume, and pitch is key to being a successful speaker.

Rate of speaking refers to how fast or slow you speak (Barnard, 2018). If you speak too fast, your audience will not be able to absorb the information you present. If you speak too slowly, the audience may lose interest. The key is to vary your rate of speaking in a middle range, staying away from either extreme, in order to keep your audience engaged. In general, a higher rate of speaking signals that a speaker is enthusiastic about his or her topic. Speaking slowly may lead the audience to infer that the speaker is uninterested, uninformed, or unprepared to present his or her own topic. These negative assumptions, whether they are true or not, are likely to hurt the credibility of the speaker (Barnard, 2018). The goal is to speak at a rate that will interest the audience and will effectively convey your information. Speaking at a slow rate throughout a speech would likely bore an audience, but that is not a common occurrence.

Volume refers to how loud or soft your voice is. As with speaking rate, you want to avoid the extremes of being too loud or too soft, but still vary your volume within an acceptable middle range (Packard, 2020). When speaking in a typically sized classroom or office setting that seats about twenty-five people, using a volume a few steps above a typical conversational volume is usually sufficient. When speaking in larger rooms, you will need to project your voice. You may want to look for nonverbal cues from people in the back rows or corners, like leaning forward or straining to hear, to see if you need to adjust your volume more. Obviously, in some settings, a microphone will be necessary so the entire audience can hear you. Like rate, audiences use volume to make a variety of judgments about a speaker. Sometimes, softer speakers are judged as meek (Packard, 2020). This may lead to lowered expectations for the speech or less perceived credibility. Loud speakers may be seen as overbearing or annoying, which can lead audience members to disengage from the speaker and message. Be aware of the volume of your voice and, when in doubt, increase your volume a notch, since beginning speakers are more likely to have an issue of speaking too softly rather than too loudly.

Pitch refers to how high or low a speaker’s voice is. As with other vocal qualities, there are natural variations among people’s vocal pitch. Unlike rate and volume, we have less control over pitch. For example, males generally have lower pitched voices than females. Despite these limitations, each person still has the capability to change their pitch across a range large enough to engage an audience. Changing pitch is a good way to communicate enthusiasm and indicate emphasis or closure (Scotti, 2015). In general, our pitch goes up when we are discussing something exciting. Our pitch goes down slightly when we emphasize a serious or important point. Lowering pitch is also an effective way to signal transitions between sections of your speech or the end of your speech, which cues your audience to applaud and avoids an awkward ending.

Of the vocal components of delivery discussed so far, pitch seems to give beginning speakers the most difficulty. It is as if giving a speech temporarily numbs their ability to vary their pitch. Record yourself practicing your speech to help determine if the amount of pitch variety and enthusiasm you think you convey while speaking actually comes through. Speakers often assume that their pitch is more varied and their delivery more enthusiastic than the audience actually perceives it to be (Scotti, 2015). Many students note this on the self-evaluations they write after viewing their recorded speech.

Vocal Variety

Overall, the lesson to take away from this section on vocal delivery is that variety is key. Vocal variety includes changes in your rate, volume, and pitch that can make you look more prepared, seem more credible, and be able to engage your audience better (Moore, 2015). Employing vocal variety is not something that takes natural ability or advanced skills training. It is something that beginning speakers can start working on immediately and everyone can accomplish. The key is to become aware of how you use your voice when you speak, and the best way to do this is to record yourself (Moore, 2015). We all use vocal variety naturally without thinking about it during our regular conversations, and many of us think that this tendency will translate over to our speaking voices. This is definitely not the case for most beginning speakers. Unlike in your regular conversations, it will take some awareness and practice to use vocal variety in speeches. I encourage students to make this a delivery priority early on. Since it is something anyone can do, improving in this area will add to your speaking confidence, which usually translates into better speeches and better grades further on.

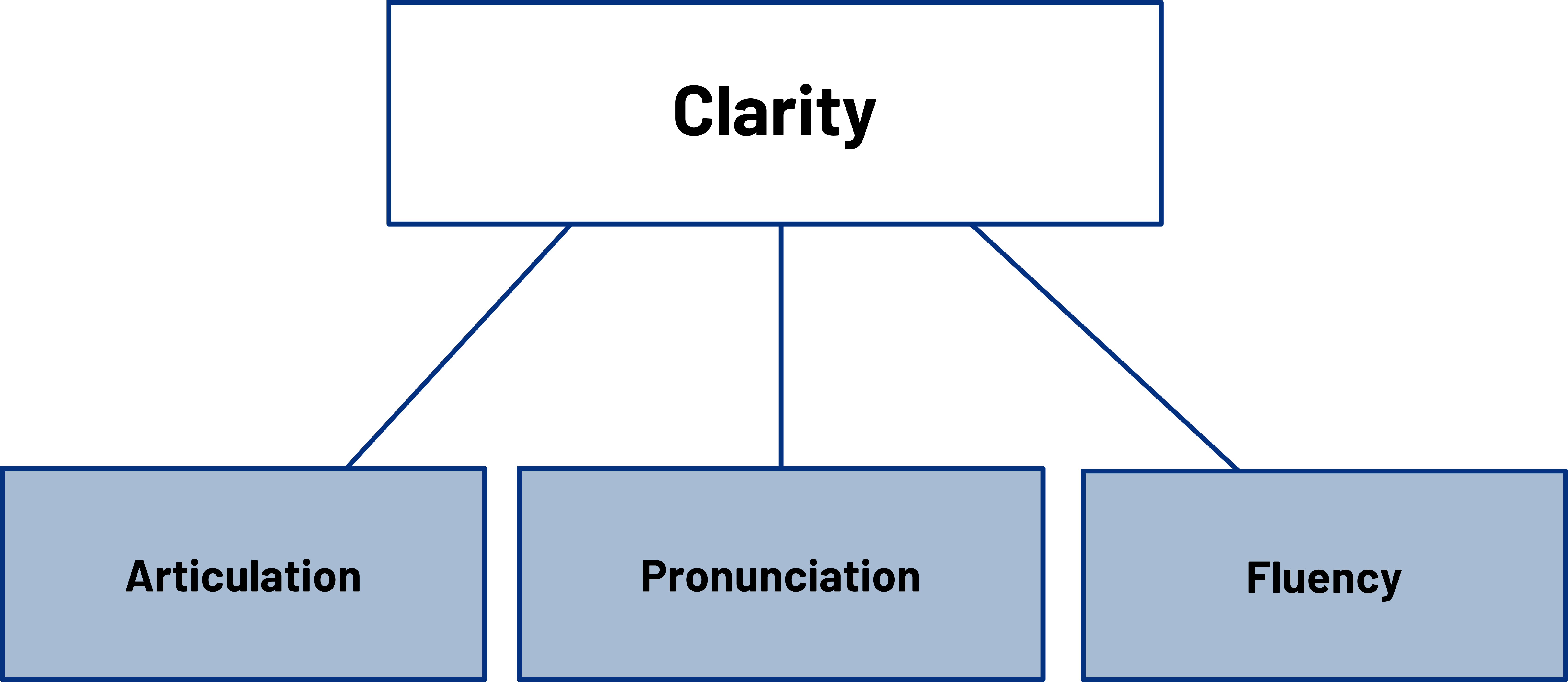

Speaking for Clarity

In order to be an effective speaker, your audience should be able to understand your message and digest the information you present (Rampton, 2021). Audience members will make assumptions about our competence and credibility based on how we speak. As with other aspects of speech delivery, many people are not aware that they have habits of speech that interfere with their message clarity. Since most of our conversations are informal and take place with people we know, many people do not make a concerted effort to articulate every word clearly and pronounce every word correctly (Rampton, 2021). Most of the people we talk to either do not notice our errors or do not correct us if they do notice. Since public speaking is generally more formal than our conversations, we should be more concerned with the clarity of our speech.

Articulation

Articulation refers to the clarity of sounds and words we produce. If someone is articulate, they speak words clearly, and speakers should strive to speak clearly. Poor articulation results when speakers do not speak clearly (Ward, 2020). For example, a person may say dinnt instead of didn’t , gonna instead of going to , wanna instead of want to , or hunnerd instead of hundred . Unawareness and laziness are two common challenges to articulation. As with other aspects of our voice, many people are unaware that they regularly have errors in articulation. Recording yourself speak and then becoming a higher self-monitor are effective ways to improve your articulation. Laziness, on the other hand, requires a little more motivation to address. Some people just get in the habit of not articulating their words well. Both mumbling and slurring are examples of poor articulation. In informal settings, this type of speaking may be acceptable, but in formal settings, it will be evaluated negatively. It will hurt a speaker’s credibility. Perhaps the promise of being judged more favorably is enough to motivate a mumbler to speak more clearly.

When combined with a low volume, poor articulation becomes an even greater problem. Doing vocal warm-ups like the ones listed in Section 10.1 “Managing Public Speaking Anxiety” or tongue twisters can help prime your mouth, lips, and tongue to articulate words more clearly. When you notice that you have trouble articulating a particular word, you can either choose a different word to include in your speech or you can repeat it a few times in a row in the days leading up to your speech to get used to saying it.

Pronunciation

Unlike articulation, which focuses on the clarity of words, pronunciation refers to speaking words correctly, including the proper sounds of the letters and the proper emphasis (Shtern, 2017). Mispronouncing words can damage a speaker’s credibility, especially when the correct pronunciation of a word is commonly known. We all commonly run into words that we are unfamiliar with and therefore may not know how to pronounce. Here are three suggestions when faced with this problem. First, look the word up in an online dictionary. Many dictionaries have a speaker icon with their definitions, and when you click on it, you can hear the correct pronunciation of a word. Some words have more than one pronunciation—for example, Caribbean —so choosing either of the accepted pronunciations is fine. Just remember to use consistently that pronunciation to avoid confusing your audience. If a word does not include an audio pronunciation, you can usually find the phonetic spelling of a word, which is the word spelled out the way it sounds.

Second, there will occasionally be words that you cannot locate in a dictionary. These are typically proper nouns or foreign words. In this case, use the “phone-a-friend” strategy. Call up the people you know who have large vocabularies or are generally smart when it comes to words, and ask them if they know how to pronounce it. If they do, and you find them credible, you are probably safe to take their suggestion.

Third, “fake it ‘til you make it” should only be used as a last resort. If you cannot find the word in a dictionary and your smart friends do not know how to pronounce it, it is likely that your audience will also be unfamiliar with the word. In that case, using your knowledge of how things are typically pronounced, decide on a pronunciation that makes sense and confidently use it during your speech. Most people will not question it. In the event that someone does correct you on your pronunciation, thank him or her for correcting you and adjust your pronunciation.

Fluency refers to the flow of your speaking. To speak with fluency means that your speech flows well and that there are not many interruptions to that flow. Two main disfluencies or problems affect the flow of a speech. Fluency hiccups are unintended pauses in a speech that usually result from forgetting what you were saying, being distracted, or losing your place in your speaking notes. Fluency hiccups are not the same as intended pauses, which are useful for adding emphasis or transitioning between parts of a speech. While speakers should try to minimize fluency hiccups, even experienced speakers need to take an unintended pause sometimes to get their bearings or to recover from an unexpected distraction. Fluency hiccups become a problem when they happen regularly enough to detract from the speaker’s message.

Verbal fillers are words that speakers use to fill in a gap between what they were saying and what they are saying next (Hennessy, 2019). Common verbal fillers include um , uh , ah , er , you know , and like . The best way to minimize verbal fillers is to become a higher self-monitor and realize that you use them. Many students are surprised when they watch the video of their first speech and realize they said “um” thirty times in three minutes. Gaining that awareness is the first step in eliminating verbal fillers, and students make noticeable progress with this between their first and second speeches (Hennessy, 2019). If you do lose your train of thought, having a brief fluency hiccup is better than injecting a verbal filler, because the audience may not even notice the pause or may think it was intentional.

9.3 Physical Delivery

Physical delivery.

Many speakers are more nervous about physical delivery than vocal delivery. Putting our bodies on the line in front of an audience often makes us feel more vulnerable than putting our voice out there. Yet most audiences are not as fixated on our physical delivery as we think they are. Knowing this can help relieve some anxiety, but it does not give us a free pass when it comes to physical delivery. We should still practice for physical delivery that enhances our verbal message. Physical delivery of a speech involves nonverbal communication through the face and eyes, gestures, and body movements.

Physical Delivery and the Face

We tend to look at a person’s face when we are listening to them (Hoffler, 2016). Again, this often makes people feel uncomfortable and contributes to their overall speaking anxiety. Many speakers do not like the feeling of having “all eyes” on them, even though having a room full of people avoiding making eye contact with you would be much more awkward. Remember, it is a good thing for audience members to look at you, because it means they are paying attention and interested. Audiences look toward the face of the speaker for cues about the tone and content of the speech.

Facial Expressions

Facial expressions can help bring a speech to life when used by a speaker to communicate emotions and demonstrate enthusiasm for the speech (Hoffler, 2016). As with vocal variety, we tend to use facial expressions naturally and without conscious effort when engaging in day-to-day conversations. Yet many speakers’ expressive faces turn “deadpan” when they stand in front of an audience. Some people naturally have more expressive faces than others do have—think about the actor Jim Carey’s ability to contort his face as an example. However, we can also consciously control and improve on our facial expressions to be speakers that are more effective. As with other components of speech delivery, becoming a higher self-monitor and increasing your awareness of your typical delivery habits can help you understand, control, and improve your delivery. Although you should not only practice your speech in front of a mirror, doing so can help you get an idea of how expressive or unexpressive your face is while delivering your speech.

Facial expressions help set the emotional tone for a speech, and it is important that your facial expressions stay consistent with your message (Hoffler, 2016). In order to set a positive tone before you start speaking, briefly look at the audience and smile. A smile is a simple but powerful facial expression that can communicate friendliness, openness, and confidence. Facial expressions communicate a range of emotions and are associated with various moods or personality traits.

For example, combinations of facial expressions can communicate that a speaker is tired, excited, angry, confused, frustrated, sad, confident, smug, shy, or bored, among other things. Even if you are not bored, for example, a slack face with little animation may lead an audience to think that you are bored with your own speech, which is not likely to motivate them to be interested. So make sure your facial expressions are communicating an emotion, mood, or personality trait that you think your audience will view favorably. Also, make sure your facial expressions match with the content of your speech. When delivering something lighthearted or humorous, a smile, bright eyes, and slightly raised eyebrows will nonverbally enhance your verbal message. When delivering something serious or somber, a furrowed brow, a tighter mouth, and even a slight head nod can enhance that message. If your facial expressions and speech content are not consistent, your audience could become confused by the conflicting messages, which could lead them to question your honesty and credibility.

Eye Contact

Eye contact is an important element of nonverbal communication in all communication settings. Eye contact can also be used to establish credibility and hold your audience’s attention (Barnard, 2017). We often interpret a lack of eye contact to mean that someone is not credible or not competent, and as a public speaker, you do not want your audience thinking either of those things. Eye contact holds attention because an audience member who knows the speaker is making regular eye contact will want to reciprocate that eye contact to show that they are paying attention. This will also help your audience remember the content of your speech better, because acting as if we are paying attention actually leads us to pay attention and better retain information.

Norms for eye contact vary among cultures (Barnard, 2017). Therefore, it may be difficult for speakers from countries that have higher power distances or are more collectivistic to get used to the idea of making direct and sustained eye contact during a speech. In these cases, it is important for the speaker to challenge himself or herself to integrate some of the host culture’s expectations and for the audience to be accommodating and understanding of the cultural differences.

Physical Delivery and the Body

Have you ever gotten dizzy as an audience member because the speaker paced back and forth? Anxiety can lead us to do some strange things with our bodies, like pacing, that we do not normally do, so it is important to consider the important role that your body plays during your speech. We call extra movements caused by anxiety nonverbal adaptors . Most of them manifest as distracting movements or gestures. These nonverbal adaptors, like tapping a foot, wringing hands, playing with a paper clip, twirling hair, jingling change in a pocket, scratching, and many more, can definitely detract from a speaker’s message and credibility. Conversely, a confident posture and purposeful gestures and movement can enhance both.

Posture is the position we assume with our bodies, either intentionally or out of habit. Although people, especially young women, used to be trained in posture, often by having them walk around with books stacked on their heads, you should use a posture that is appropriate for the occasion while still positioning yourself in a way that feels natural. In a formal speaking situation, it is important to have an erect posture that communicates professionalism and credibility (Clayton, 2018). However, a military posture of standing at attention may feel and look unnatural in a typical school or business speech. In informal settings, it may be appropriate to lean on a table or lectern, or even sit among your audience members (Clayton, 2018). Head position is also part of posture. In most speaking situations, it is best to keep your head up, facing your audience. A droopy head does not communicate confidence. Consider the occasion important, as an inappropriate posture can hurt your credibility.

Gestures include arm and hand movements. We all go through a process of internalizing our native culture from childhood. An obvious part of this process is becoming fluent in a language. Perhaps less obvious is the fact that we also become fluent in nonverbal communication, gestures in particular. We all use hand gestures while we speak, but we didn’t ever take a class in matching verbal communication with the appropriate gestures; we just internalized these norms over time based on observation and put them into practice. By this point in your life, you have a whole vocabulary of hand movements and gestures that spontaneously come out while you are speaking. Some of these gestures are emphatic and some are descriptive (Koch, 2007).

Emphatic gestures are the most common hand gestures we use, and they function to emphasize our verbal communication and often relate to the emotions we verbally communicate (Toastmasters International, 2011). Pointing with one finger or all the fingers straight out is an emphatic gesture. We can even bounce that gesture up and down to provide more emphasis. Moving the hand in a circular motion in front of our chest with the fingers spread apart is a common emphatic gesture that shows excitement and often accompanies an increased rate of verbal speaking. We make this gesture more emphatic by using both hands. Descriptive gestures function to illustrate or refer to objects rather than emotions (Toastmasters International, 2011). We use descriptive gestures to indicate the number of something by counting with our fingers or the size, shape, or speed of something. Our hands and arms are often the most reliable and easy-to-use visual aids a speaker can have.

While the best beginning strategy is to gesture naturally, you also want to remain a high self-monitor and take note of your typical patterns of gesturing. If you notice that you naturally gravitate toward one particular gesture, make an effort to vary your gestures more. You also want your gestures to be purposeful, not limp or lifeless.

Sometimes movement of the whole body, instead of just gesturing with hands, is appropriate in a speech. When students are given the freedom to move around, it often ends up becoming floating or pacing, which are both movements that comfort a speaker by expending nervous energy but only serve to distract the audience (Toastmasters International, 2011). Floating refers to speakers who wander aimlessly around, and pacing refers to speakers who walk back and forth in the same path. To prevent floating or pacing, make sure that your movements are purposeful. Many speakers employ the triangle method of body movement where they start in the middle, take a couple steps forward and to the right, then take a couple steps to the left, then return to the center. Obviously, you do not need to do this multiple times in a five- to ten-minute speech, as doing so, just like floating or pacing, tends to make an audience dizzy.

To make your movements appear more natural, time them to coincide with a key point you want to emphasize or a transition between key points. Minimize other movements from the waist down when you are not purposefully moving for emphasis. Speakers sometimes tap or shuffle their feet, rock, or shift their weight back and forth from one leg to the other. Keeping both feet flat on the floor, and still, will help avoid these distracting movements (Toastmasters International, 2011).

Credibility and Physical Delivery

Audience members primarily take in information through visual and auditory channels. Just as the information you present verbally in your speech can add to or subtract from your credibility, nonverbal communication that accompanies your verbal messages affects your credibility.

Professional Dress and Appearance

No matter what professional field you go into, you will need to consider the importance of personal appearance (Caffrey, 2020). Although it may seem petty or shallow to put so much emphasis on dress and appearance, impressions matter, and people make judgments about our personality, competence, and credibility based on how we look. In some cases, you may work somewhere with a clearly laid out policy for personal dress and appearance. In many cases, the suggestion is to follow guidelines for “business casual.”

Despite the increasing popularity of this notion over the past twenty years, people’s understanding of what business casual means is not consistent (Caffrey, 2020). The formal dress codes of the mid-1900s, which required employees to wear suits and dresses, gave way to the trend of business casual dress, which seeks to allow employees to work comfortably while still appearing professional. While most people still dress more formally for job interviews or high-stakes presentations, the day-to-day dress of working professionals varies.

Visual Aids and Delivery

Visual aids play an important role in conveying supporting material to your audience. They also tie to delivery, since using visual aids during a speech usually requires some physical movements. It is important not to let your use of visual aids detract from your credibility (Beqiri, 2018). Many good speeches are derailed by posters that fall over, videos with no sound, and uncooperative PowerPoint presentations.

Figure 9.1: Systematic desensitization can include giving more public speeches, taking communication courses, or imagining public speaking scenarios. William Moreland. 2019. Unsplash license . https://unsplash.com/photos/GkWP64truqg

Figure 9.2: Vocal warm-up exercises. Andrea Piacquadio. 2020. Pexels license . https://www.pexels.com/photo/man-in-red-polo-shirt-3779453/

Figure 9.3: Primary phases to the practice process. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 9.4: Three facets of speaking for clarity. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 9.5: Facial expressions set the tone for a speech, and should be consistent with your message. Afif Kusuma. 2021. Unsplash license . https://unsplash.com/photos/F3dFVKj6q8I

Figure 9.6: To make your movements appear natural, time them to coincide with a key point. Product School. 2019. Unsplash license . https://unsplash.com/photos/S3hhrqLrgYM

Section 9.1

Allen, M., Hunter, J. E., & Donohue, W. A. (1989). Meta-analysis of self-report data on the effectiveness of public speaking anxiety treatment techniques. Communication Education, 38 (1), 54–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634528909378740

Bodie, G. D. (2010). A racing heart, rattling knees, and ruminative thoughts: Defining, explaining, and treating public speaking anxiety. Communication Education, 59 (1), 70–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520903443849

Motley, M. T. (2009). COM therapy. In J. A. Daly, J. C. McCroskey, J. Ayres, T. Hopf, and D. M. Ayers Sonandré (Eds.), Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension (pp. 379-400) (3rd ed.). Hampton Press.

Priem, J. S., & Haunani Solomon, D. (2009). Comforting apprehensive communicators: The effects of reappraisal and distraction on cortisol levels among students in a public speaking class. Communication Quarterly, 57 (3), 259-281.

Section 9.2

Barnard, D. (2018, January 20). Average speaking rate and words per minute . https://virtualspeech.com/blog/average-speaking-rate-words-per-minute

Davis, B. (2021, June 1). Why is audience engagement important? https://www.mvorganizing.org/why-is-audience-engagement-important/

Hennessy, C. (2019, March 27). Verbal filler: How to slow the flow . https://www.throughlinegroup.com/2019/03/27/verbal-filler-how-to-slow-the-flow/

LibreTexts. (2021, February 20). Methods of speech delivery . https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Communication/Public_Speaking/Exploring_Public_Speaking_(Barton_and_Tucker)/11%3A_Delivery/11.02%3A_Methods_of_Speech_Delivery

Moore, K. (2015, January 13). Public speaking tips: Use vocal variety like a pro! https://coachkiomi.com/best-public-speaking-tips-use-vocal-variety/

Packard, D. (2020, July 13). Speaking up: How to increase the volume of your voice . https://packardcommunications.com/speaking-up-how-to-increase-the-volume-of-your-voice/

Rampton, J. (2021, July 27). Learning to speak with clarity . https://www.calendar.com/blog/learning-to-speak-with-clarity/

Scotti, S. (2015, December 1). Vocal delivery: Take command of your voice . https://professionallyspeaking.net/vocal-delivery-take-command-of-your-voice-part-one/

Shtern, A. (2017, April 17). The importance of good pronunciation . https://shaneschools.com/en/the-importance-of-good-pronunciation/

Section 9.3

Barnard, D. (2017, October 24). The importance of eye contact during a presentation . https://virtualspeech.com/blog/importance-of-eye-contact-during-a-presentation

Beqiri, G. (2018, June 21). Using visual aids during a presentation or training session . https://virtualspeech.com/blog/visual-aids-presentation

Caffrey, A. (2020, February 25). The importance of personal appearance . http://www.publicspeakingexpert.co.uk/importanceofpersonalappearance.html

Clayton, D. (2018, October 31). The importance of good posture in public speaking . https://simplyamazingtraining.co.uk/blog/good-posture-public-speaking

Hoffler, A. (2016, June 7). Why facial expressions are important in public speaking . https://www.millswyck.com/2016/06/07/the-importance-of-facial-expression/

Koch, A. (2007). Speaking with a purpose (7th ed.). Pearson, 2007.

Toastmasters International. (2011). Gestures: Your body speaks . https://web.mst.edu/~toast/docs/Gestures.pdf

Fear or anxiety experience by a person due to real or perceived communication with another person or persons. This is a fear or anxiety that involves several types of communication not limited to public speaking.

Type of communication apprehension that produces physiological, cognitive, and behavioral reactions in people when faced with a real or imagined presentation

A type of cognitive restructuring that encourages people to think of public speaking as conversation rather than a performance

When a speaker has little or no time to prepare a speech

Speaking from a well written or printed document that contains the entirety of a speech

Completely memorizing a speech and delivering it without notes

Memorizing the overall structure and main points of a speech and then speaking from keyword/key-phrase notes

Refers to how fast or slow you speak

Refers to how loud or soft you speak

Refers to how high or low a speaker’s voice is

Changes in your rate, volume, and pitch that make you sound more prepared and credible

Refers to the clarity of sounds and words you pronounce

Whether you say the words correctly

Refers to the flow of your speaking

Unintended pauses in a speech that usually result from forgetting what you were saying, being distracted, or losing your place in speaking

The umms, uhhs, and other linguistic pauses of conversation

The feelings expressed on a person’s face

The act of looking directly into one another’s eyes

Extra movements caused by anxiety (i.e., tapping your foot, wringing your hands, playing with a paperclip, twirling hair, or scratching)

The position in which someone holds their body when standing or sitting

A movement of part of the body, especially a hand or the head, to express an idea or meaning

Communication in the Real World Copyright © by Faculty members in the School of Communication Studies, James Madison University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 32: Methods of Speech Delivery

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Distinguish between four methods of speech delivery: the impromptu speech, the manuscript speech, the memorized speech, and the extemporaneous speech

- List the advantages and disadvantages of the four types of speeches

- Explain why an extemporaneous is the preferred delivery style when using rhetorical theory

Key Terms and Concepts

- extemporaneous

We have established that presentations involve much more than the transfer of information. Sure, you could treat a presentation as an opportunity to simply read a report you’ve written out loud to a group, but you would fail to both engage your audience and make a connection with them. In other words, you would leave them wondering exactly why they had to listen to your presentation instead of reading it at their leisure.

The Four Methods of Speech Delivery

One of the ways to ensure that you engage your audience effectively is by carefully considering how best to deliver your speech. Each of you has sat in a class, presentation, or meeting where you didn’t feel interested in the information the presenter was sharing. Part of the reason for your disengagement likely originated in the presenter’s method of speech delivery .

For our purposes, there are four different methods—or types—of speech delivery used in technical communication:

- Extemporaneous

Exercise #1: The Four Methods of Speech Delivery

What comes to mind when you think about the four methods of speech delivery? How do you think they are different from one another? Have you given a speech using any of these methods before?

Watch the video below for a brief overview of each one. After you are finished, answer the questions below:

- Which method are you most comfortable with? Why?

- Which method are you the least comfortable with? Why?

- Which method do you think is the best for connecting with your audience? Why?

The public speaking section of this course will require you to deliver a speech using an extemporaneous style, but let’s take a look at how all four differ in approach:

Impromptu Speeches

Impromptu speaking is the presentation of a short message without advanced preparation. You have probably done impromptu speaking many times in informal, conversational settings. Self-introductions in group settings are examples of impromptu speaking: “ Hi, my name is Shawnda, and I’m a student at the University of Saskatchewan .”

Another example of impromptu speaking occurs when you answer a question such as, “What did you think of the movie?” Your response has not been pre-planned, and you are constructing your arguments and points as you speak. Even worse, you might find yourself going into a meeting when your boss announces to you, “I want you to talk about the last stage of the project” with no warning.

The advantage of this kind of speaking is that it’s spontaneous and responsive in an animated group context. The disadvantage is that the speaker is giv en little or no time to contemplate the central theme of their message. As a result, the message may be disorganized and difficult for listeners to follow.

Here is a step-by-step guide that may be useful if you are called upon to give an impromptu speech in public:

- Take a moment to collect your thoughts and plan the main point that you want to make (like a mini thesis statement).

- Thank the person for inviting you to speak. Do not make comments about being unprepared, called upon at the last moment, on the spot, or uneasy. In other words, try to avoid being self-deprecating!

- Deliver your message, making your main point as briefly as you can while still covering it adequately and at a pace your listeners can follow.

- If you can use a structure, use numbers if possible: “Two main reasons. . .” or “Three parts of our plan. . .” or “Two side effects of this drug. . .” Past, present, and future or East Coast, Midwest, and West Coast are pre-fab structures.

- Thank the person again for the opportunity to speak.

- Stop talking. It is easy to “ramble on” when you don’t have something prepared. If in front of an audience, don’t keep talking as you move back to your seat.

Impromptu speeches are generally most successful when they are brief and focus on a single point.

We recommend practicing your impromptu speaking regularly. Do you want to work on reducing your vocalized pauses in a formal setting? Great! You can begin that process by being conscious of your vocalized fillers during informal conversations and settings.

Exercise #2: Impromptu Speech Example

Below are two examples of an impromptu speech. In the first video, a teacher is demonstrating an impromptu speech to his students on the topic of strawberries. He quickly jots down some notes before presenting.

What works in his speech? What could be improved?

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/impromptuteacher

In the above example, the teacher did an okay job, considering how little time he had to prepare.

In this next example, you will see just how badly an impromptu speech can go. It is a video of a best man speech at a wedding. Keep in mind that the speaker is the groom’s brother.

Is there anything that he does well? What are some problems with his speech?

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/badimpromptubestman

Manuscript Speeches

Manuscript speaking is the word-for-word iteration of a written message. In a manuscript speech, the speaker maintains their attention on the printed page except when using presentation aids.

The advantage to reading from a manuscript is the exact repetition of original words. This can be extremely important in some circumstances. For example, reading a statement about your organization’s legal responsibilities to customers may require that the original words be exact. In reading one word at a time, in order, the only errors would typically be the mispronunciation of a word or stumbling over complex sentence structure. A manuscript speech may also be appropriate at a more formal affair (like a funeral), when your speech must be said exactly as written in order to convey the proper emotion the situation deserves.

However, there are costs involved in manuscript speaking. First, it’s typically an uninteresting way to present. Unless the speaker has rehearsed the reading as a complete performance animated with vocal expression and gestures (well-known authors often do this for book readings), the presentation tends to be dull. Keeping one’s eyes glued to the script prevents eye contact with the audience.

For this kind of “straight” manuscript speech to hold audience attention, the audience must be already interested in the message and speaker before the delivery begins. Finally, because the full notes are required, speakers often require a lectern to place their notes, restricting movement and the ability to engage with the audience. Without something to place the notes on, speakers have to manage full-page speaking notes, and that can be distracting.

It is worth noting that professional speakers, actors, news reporters, and politicians often read from an autocue device such as a teleprompter. This device is especially common when these people appear on television where eye contact with the camera is crucial. With practice, a speaker can achieve a conversational tone and give the impression of speaking extemporaneously and maintaining eye contact while using an autocue device.

However, success in this medium depends on two factors:

- the speaker is already an accomplished public speaker who has learned to use a conversational tone while delivering a prepared script, and

- the speech is written in a style that sounds conversational.

Exercise #3: Manuscript Speech Example

Below is a video that shows an example of a manuscript speech. In the video, US Presidential Historian, Doris Kearns Goodwin, gives a speech about different US presidents.

What works in her speech? What could be improved?

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/goodwindepauw

Here’s a video that shows the dangers of relying on a manuscript for your speech:

Michael Bay heavily relied on his manuscript , so when he suddenly lost access to it, he was left feeling embarrassed and had to hastily leave the stage. As a result, he experienced face loss .

Link to original video: https://tinyurl.com/MBayManuscript

Memorized Speeches

Memorized speaking is reciting a written message that the speaker has committed to memory. Actors, of course, recite from memory whenever they perform from a script in a stage play, television program, or movie. When it comes to speeches, memorization can be useful when the message needs to be exact and the speaker doesn’t want to be confined by notes.

The advantage to memorization is that it enables the speaker to maintain eye contact with the audience throughout the speech. Being free of notes means that you can move freely around the stage and use your hands to make gestures. If your speech uses presentation aids, this freedom is even more of an advantage.