There’s No Such Thing as Free Will

But we’re better off believing in it anyway.

F or centuries , philosophers and theologians have almost unanimously held that civilization as we know it depends on a widespread belief in free will—and that losing this belief could be calamitous. Our codes of ethics, for example, assume that we can freely choose between right and wrong. In the Christian tradition, this is known as “moral liberty”—the capacity to discern and pursue the good, instead of merely being compelled by appetites and desires. The great Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant reaffirmed this link between freedom and goodness. If we are not free to choose, he argued, then it would make no sense to say we ought to choose the path of righteousness.

Today, the assumption of free will runs through every aspect of American politics, from welfare provision to criminal law. It permeates the popular culture and underpins the American dream—the belief that anyone can make something of themselves no matter what their start in life. As Barack Obama wrote in The Audacity of Hope , American “values are rooted in a basic optimism about life and a faith in free will.”

So what happens if this faith erodes?

The sciences have grown steadily bolder in their claim that all human behavior can be explained through the clockwork laws of cause and effect. This shift in perception is the continuation of an intellectual revolution that began about 150 years ago, when Charles Darwin first published On the Origin of Species . Shortly after Darwin put forth his theory of evolution, his cousin Sir Francis Galton began to draw out the implications: If we have evolved, then mental faculties like intelligence must be hereditary. But we use those faculties—which some people have to a greater degree than others—to make decisions. So our ability to choose our fate is not free, but depends on our biological inheritance.

Explore the June 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Galton launched a debate that raged throughout the 20th century over nature versus nurture. Are our actions the unfolding effect of our genetics? Or the outcome of what has been imprinted on us by the environment? Impressive evidence accumulated for the importance of each factor. Whether scientists supported one, the other, or a mix of both, they increasingly assumed that our deeds must be determined by something .

In recent decades, research on the inner workings of the brain has helped to resolve the nature-nurture debate—and has dealt a further blow to the idea of free will. Brain scanners have enabled us to peer inside a living person’s skull, revealing intricate networks of neurons and allowing scientists to reach broad agreement that these networks are shaped by both genes and environment. But there is also agreement in the scientific community that the firing of neurons determines not just some or most but all of our thoughts, hopes, memories, and dreams.

We know that changes to brain chemistry can alter behavior—otherwise neither alcohol nor antipsychotics would have their desired effects. The same holds true for brain structure: Cases of ordinary adults becoming murderers or pedophiles after developing a brain tumor demonstrate how dependent we are on the physical properties of our gray stuff.

Many scientists say that the American physiologist Benjamin Libet demonstrated in the 1980s that we have no free will. It was already known that electrical activity builds up in a person’s brain before she, for example, moves her hand; Libet showed that this buildup occurs before the person consciously makes a decision to move. The conscious experience of deciding to act, which we usually associate with free will, appears to be an add-on, a post hoc reconstruction of events that occurs after the brain has already set the act in motion.

The 20th-century nature-nurture debate prepared us to think of ourselves as shaped by influences beyond our control. But it left some room, at least in the popular imagination, for the possibility that we could overcome our circumstances or our genes to become the author of our own destiny. The challenge posed by neuroscience is more radical: It describes the brain as a physical system like any other, and suggests that we no more will it to operate in a particular way than we will our heart to beat. The contemporary scientific image of human behavior is one of neurons firing, causing other neurons to fire, causing our thoughts and deeds, in an unbroken chain that stretches back to our birth and beyond. In principle, we are therefore completely predictable. If we could understand any individual’s brain architecture and chemistry well enough, we could, in theory, predict that individual’s response to any given stimulus with 100 percent accuracy.

This research and its implications are not new. What is new, though, is the spread of free-will skepticism beyond the laboratories and into the mainstream. The number of court cases, for example, that use evidence from neuroscience has more than doubled in the past decade—mostly in the context of defendants arguing that their brain made them do it. And many people are absorbing this message in other contexts, too, at least judging by the number of books and articles purporting to explain “your brain on” everything from music to magic. Determinism, to one degree or another, is gaining popular currency. The skeptics are in ascendance.

This development raises uncomfortable—and increasingly nontheoretical—questions: If moral responsibility depends on faith in our own agency, then as belief in determinism spreads, will we become morally irresponsible? And if we increasingly see belief in free will as a delusion, what will happen to all those institutions that are based on it?

In 2002, two psychologists had a simple but brilliant idea: Instead of speculating about what might happen if people lost belief in their capacity to choose, they could run an experiment to find out. Kathleen Vohs, then at the University of Utah, and Jonathan Schooler, of the University of Pittsburgh, asked one group of participants to read a passage arguing that free will was an illusion, and another group to read a passage that was neutral on the topic. Then they subjected the members of each group to a variety of temptations and observed their behavior. Would differences in abstract philosophical beliefs influence people’s decisions?

Yes, indeed. When asked to take a math test, with cheating made easy, the group primed to see free will as illusory proved more likely to take an illicit peek at the answers. When given an opportunity to steal—to take more money than they were due from an envelope of $1 coins—those whose belief in free will had been undermined pilfered more. On a range of measures, Vohs told me, she and Schooler found that “people who are induced to believe less in free will are more likely to behave immorally.”

It seems that when people stop believing they are free agents, they stop seeing themselves as blameworthy for their actions. Consequently, they act less responsibly and give in to their baser instincts. Vohs emphasized that this result is not limited to the contrived conditions of a lab experiment. “You see the same effects with people who naturally believe more or less in free will,” she said.

In another study, for instance, Vohs and colleagues measured the extent to which a group of day laborers believed in free will, then examined their performance on the job by looking at their supervisor’s ratings. Those who believed more strongly that they were in control of their own actions showed up on time for work more frequently and were rated by supervisors as more capable. In fact, belief in free will turned out to be a better predictor of job performance than established measures such as self-professed work ethic.

Another pioneer of research into the psychology of free will, Roy Baumeister of Florida State University, has extended these findings. For example, he and colleagues found that students with a weaker belief in free will were less likely to volunteer their time to help a classmate than were those whose belief in free will was stronger. Likewise, those primed to hold a deterministic view by reading statements like “Science has demonstrated that free will is an illusion” were less likely to give money to a homeless person or lend someone a cellphone.

Further studies by Baumeister and colleagues have linked a diminished belief in free will to stress, unhappiness, and a lesser commitment to relationships. They found that when subjects were induced to believe that “all human actions follow from prior events and ultimately can be understood in terms of the movement of molecules,” those subjects came away with a lower sense of life’s meaningfulness. Early this year, other researchers published a study showing that a weaker belief in free will correlates with poor academic performance.

The list goes on: Believing that free will is an illusion has been shown to make people less creative, more likely to conform, less willing to learn from their mistakes, and less grateful toward one another. In every regard, it seems, when we embrace determinism, we indulge our dark side.

Few scholars are comfortable suggesting that people ought to believe an outright lie. Advocating the perpetuation of untruths would breach their integrity and violate a principle that philosophers have long held dear: the Platonic hope that the true and the good go hand in hand. Saul Smilansky, a philosophy professor at the University of Haifa, in Israel, has wrestled with this dilemma throughout his career and come to a painful conclusion: “We cannot afford for people to internalize the truth” about free will.

Smilansky is convinced that free will does not exist in the traditional sense—and that it would be very bad if most people realized this. “Imagine,” he told me, “that I’m deliberating whether to do my duty, such as to parachute into enemy territory, or something more mundane like to risk my job by reporting on some wrongdoing. If everyone accepts that there is no free will, then I’ll know that people will say, ‘Whatever he did, he had no choice—we can’t blame him.’ So I know I’m not going to be condemned for taking the selfish option.” This, he believes, is very dangerous for society, and “the more people accept the determinist picture, the worse things will get.”

Determinism not only undermines blame, Smilansky argues; it also undermines praise. Imagine I do risk my life by jumping into enemy territory to perform a daring mission. Afterward, people will say that I had no choice, that my feats were merely, in Smilansky’s phrase, “an unfolding of the given,” and therefore hardly praiseworthy. And just as undermining blame would remove an obstacle to acting wickedly, so undermining praise would remove an incentive to do good. Our heroes would seem less inspiring, he argues, our achievements less noteworthy, and soon we would sink into decadence and despondency.

Smilansky advocates a view he calls illusionism—the belief that free will is indeed an illusion, but one that society must defend. The idea of determinism, and the facts supporting it, must be kept confined within the ivory tower. Only the initiated, behind those walls, should dare to, as he put it to me, “look the dark truth in the face.” Smilansky says he realizes that there is something drastic, even terrible, about this idea—but if the choice is between the true and the good, then for the sake of society, the true must go.

Smilansky’s arguments may sound odd at first, given his contention that the world is devoid of free will: If we are not really deciding anything, who cares what information is let loose? But new information, of course, is a sensory input like any other; it can change our behavior, even if we are not the conscious agents of that change. In the language of cause and effect, a belief in free will may not inspire us to make the best of ourselves, but it does stimulate us to do so.

Illusionism is a minority position among academic philosophers, most of whom still hope that the good and the true can be reconciled. But it represents an ancient strand of thought among intellectual elites. Nietzsche called free will “a theologians’ artifice” that permits us to “judge and punish.” And many thinkers have believed, as Smilansky does, that institutions of judgment and punishment are necessary if we are to avoid a fall into barbarism.

Smilansky is not advocating policies of Orwellian thought control . Luckily, he argues, we don’t need them. Belief in free will comes naturally to us. Scientists and commentators merely need to exercise some self-restraint, instead of gleefully disabusing people of the illusions that undergird all they hold dear. Most scientists “don’t realize what effect these ideas can have,” Smilansky told me. “Promoting determinism is complacent and dangerous.”

Yet not all scholars who argue publicly against free will are blind to the social and psychological consequences. Some simply don’t agree that these consequences might include the collapse of civilization. One of the most prominent is the neuroscientist and writer Sam Harris, who, in his 2012 book, Free Will , set out to bring down the fantasy of conscious choice. Like Smilansky, he believes that there is no such thing as free will. But Harris thinks we are better off without the whole notion of it.

“We need our beliefs to track what is true,” Harris told me. Illusions, no matter how well intentioned, will always hold us back. For example, we currently use the threat of imprisonment as a crude tool to persuade people not to do bad things. But if we instead accept that “human behavior arises from neurophysiology,” he argued, then we can better understand what is really causing people to do bad things despite this threat of punishment—and how to stop them. “We need,” Harris told me, “to know what are the levers we can pull as a society to encourage people to be the best version of themselves they can be.”

According to Harris, we should acknowledge that even the worst criminals—murderous psychopaths, for example—are in a sense unlucky. “They didn’t pick their genes. They didn’t pick their parents. They didn’t make their brains, yet their brains are the source of their intentions and actions.” In a deep sense, their crimes are not their fault. Recognizing this, we can dispassionately consider how to manage offenders in order to rehabilitate them, protect society, and reduce future offending. Harris thinks that, in time, “it might be possible to cure something like psychopathy,” but only if we accept that the brain, and not some airy-fairy free will, is the source of the deviancy.

Accepting this would also free us from hatred. Holding people responsible for their actions might sound like a keystone of civilized life, but we pay a high price for it: Blaming people makes us angry and vengeful, and that clouds our judgment.

“Compare the response to Hurricane Katrina,” Harris suggested, with “the response to the 9/11 act of terrorism.” For many Americans, the men who hijacked those planes are the embodiment of criminals who freely choose to do evil. But if we give up our notion of free will, then their behavior must be viewed like any other natural phenomenon—and this, Harris believes, would make us much more rational in our response.

Although the scale of the two catastrophes was similar, the reactions were wildly different. Nobody was striving to exact revenge on tropical storms or declare a War on Weather, so responses to Katrina could simply focus on rebuilding and preventing future disasters. The response to 9/11 , Harris argues, was clouded by outrage and the desire for vengeance, and has led to the unnecessary loss of countless more lives. Harris is not saying that we shouldn’t have reacted at all to 9/11, only that a coolheaded response would have looked very different and likely been much less wasteful. “Hatred is toxic,” he told me, “and can destabilize individual lives and whole societies. Losing belief in free will undercuts the rationale for ever hating anyone.”

Whereas the evidence from Kathleen Vohs and her colleagues suggests that social problems may arise from seeing our own actions as determined by forces beyond our control—weakening our morals, our motivation, and our sense of the meaningfulness of life—Harris thinks that social benefits will result from seeing other people’s behavior in the very same light. From that vantage point, the moral implications of determinism look very different, and quite a lot better.

What’s more, Harris argues, as ordinary people come to better understand how their brains work, many of the problems documented by Vohs and others will dissipate. Determinism, he writes in his book, does not mean “that conscious awareness and deliberative thinking serve no purpose.” Certain kinds of action require us to become conscious of a choice—to weigh arguments and appraise evidence. True, if we were put in exactly the same situation again, then 100 times out of 100 we would make the same decision, “just like rewinding a movie and playing it again.” But the act of deliberation—the wrestling with facts and emotions that we feel is essential to our nature—is nonetheless real.

The big problem, in Harris’s view, is that people often confuse determinism with fatalism. Determinism is the belief that our decisions are part of an unbreakable chain of cause and effect. Fatalism, on the other hand, is the belief that our decisions don’t really matter, because whatever is destined to happen will happen—like Oedipus’s marriage to his mother, despite his efforts to avoid that fate.

When people hear there is no free will, they wrongly become fatalistic; they think their efforts will make no difference. But this is a mistake. People are not moving toward an inevitable destiny; given a different stimulus (like a different idea about free will), they will behave differently and so have different lives. If people better understood these fine distinctions, Harris believes, the consequences of losing faith in free will would be much less negative than Vohs’s and Baumeister’s experiments suggest.

Can one go further still? Is there a way forward that preserves both the inspiring power of belief in free will and the compassionate understanding that comes with determinism?

Philosophers and theologians are used to talking about free will as if it is either on or off; as if our consciousness floats, like a ghost, entirely above the causal chain, or as if we roll through life like a rock down a hill. But there might be another way of looking at human agency.

Some scholars argue that we should think about freedom of choice in terms of our very real and sophisticated abilities to map out multiple potential responses to a particular situation. One of these is Bruce Waller, a philosophy professor at Youngstown State University. In his new book, Restorative Free Will , he writes that we should focus on our ability, in any given setting, to generate a wide range of options for ourselves, and to decide among them without external constraint.

For Waller, it simply doesn’t matter that these processes are underpinned by a causal chain of firing neurons. In his view, free will and determinism are not the opposites they are often taken to be; they simply describe our behavior at different levels.

Waller believes his account fits with a scientific understanding of how we evolved: Foraging animals—humans, but also mice, or bears, or crows—need to be able to generate options for themselves and make decisions in a complex and changing environment. Humans, with our massive brains, are much better at thinking up and weighing options than other animals are. Our range of options is much wider, and we are, in a meaningful way, freer as a result.

Waller’s definition of free will is in keeping with how a lot of ordinary people see it. One 2010 study found that people mostly thought of free will in terms of following their desires, free of coercion (such as someone holding a gun to your head). As long as we continue to believe in this kind of practical free will, that should be enough to preserve the sorts of ideals and ethical standards examined by Vohs and Baumeister.

Yet Waller’s account of free will still leads to a very different view of justice and responsibility than most people hold today. No one has caused himself: No one chose his genes or the environment into which he was born. Therefore no one bears ultimate responsibility for who he is and what he does. Waller told me he supported the sentiment of Barack Obama’s 2012 “You didn’t build that” speech, in which the president called attention to the external factors that help bring about success. He was also not surprised that it drew such a sharp reaction from those who want to believe that they were the sole architects of their achievements. But he argues that we must accept that life outcomes are determined by disparities in nature and nurture, “so we can take practical measures to remedy misfortune and help everyone to fulfill their potential.”

Understanding how will be the work of decades, as we slowly unravel the nature of our own minds. In many areas, that work will likely yield more compassion: offering more (and more precise) help to those who find themselves in a bad place. And when the threat of punishment is necessary as a deterrent, it will in many cases be balanced with efforts to strengthen, rather than undermine, the capacities for autonomy that are essential for anyone to lead a decent life. The kind of will that leads to success—seeing positive options for oneself, making good decisions and sticking to them—can be cultivated, and those at the bottom of society are most in need of that cultivation.

To some people, this may sound like a gratuitous attempt to have one’s cake and eat it too. And in a way it is. It is an attempt to retain the best parts of the free-will belief system while ditching the worst. President Obama—who has both defended “a faith in free will” and argued that we are not the sole architects of our fortune—has had to learn what a fine line this is to tread. Yet it might be what we need to rescue the American dream—and indeed, many of our ideas about civilization, the world over—in the scientific age.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

30 Existence of Free Will

Determinism and freedom.

Determinism and free will are often thought to be in deep conflict. Whether or not this is true has a lot to do with what is meant by determinism and an account of what free will requires.

First of all, determinism is not the view that free actions are impossible. Rather, determinism is the view that at any one time, only one future is physically possible. To be a little more specific, determinism is the view that a complete description of the past along with a complete account of the relevant laws of nature logically entails all future events. 1

Indeterminism is simply the denial of determinism. If determinism is incompatible with free will, it will be because free actions are only possible in worlds in which more than one future is physically possible at any one moment in time. While it might be true that free will requires indeterminism, it’s not true merely by definition. A further argument is needed and this suggests that it is at least possible that people could sometimes exercise the control necessary for morally responsible action, even if we live in a deterministic world.

It is worth saying something about fatalism before we move on. It is really easy to mistake determinism for fatalism, and fatalism does seem to be in straightforward conflict with free will. Fatalism is the view that we are powerless to do anything other than what we actually do. If fatalism is true, then nothing that we try or think or intend or believe or decide has any causal effect or relevance as to what we actually end up doing.

But note that determinism need not entail fatalism. Determinism is a claim about what is logically entailed by the rules/laws governing a world and the past of said world. It is not the claim that we lack the power to do other than what we actually were already going to do. Nor is it the view that we fail to be an important part of the causal story for why we do what we do. And this distinction may allow some room for freedom, even in deterministic worlds.

An example will be helpful here. We know that the boiling point for water is 100°C. Suppose we know in both a deterministic world and a fatalistic world that my pot of water will be boiling at 11:22am today. Determinism makes the claim that if I take a pot of water and I put it on my stove, and heat it to 100°C, it will boil. This is because the laws of nature (in this case, water that is heated to 100°C will boil) and the events of the past (I put a pot of water on a hot stove) bring about the boiling water. But fatalism makes a different claim. If my pot of water is fated to boil at 11:22am today, then no matter what I or anyone does, my pot of water will boil at exactly 11:22am today. I could try to empty the pot of water out at 11:21. I could try to take the pot as far away from a heating source as possible. Nonetheless, my pot of water will be boiling at 11:22 precisely because it was fated that this would happen. Under fatalism, the future is fixed or preordained, but this need not be the case in a deterministic world. Under determinism, the future is a certain way because of the past and the rules governing said world. If we know that a pot of water will boil at 11:22am in a deterministic world, it’s because we know that the various causal conditions will hold in our world such that at 11:22 my pot of water will have been put on a heat source and brought to 100°C. Our deliberations, our choices, and our free actions may very well be part of the process that brings a pot of water to the boiling point in a deterministic world, whereas these are clearly irrelevant in fatalistic ones.

Three Views of Freedom

Most accounts of freedom fall into one of three camps. Some people take freedom to require merely the ability to “do what you want to do.” For example, if you wanted to walk across the room, right now, and you also had the ability, right now, to walk across the room, you would be free as you could do exactly what you want to do. We will call this easy freedom.

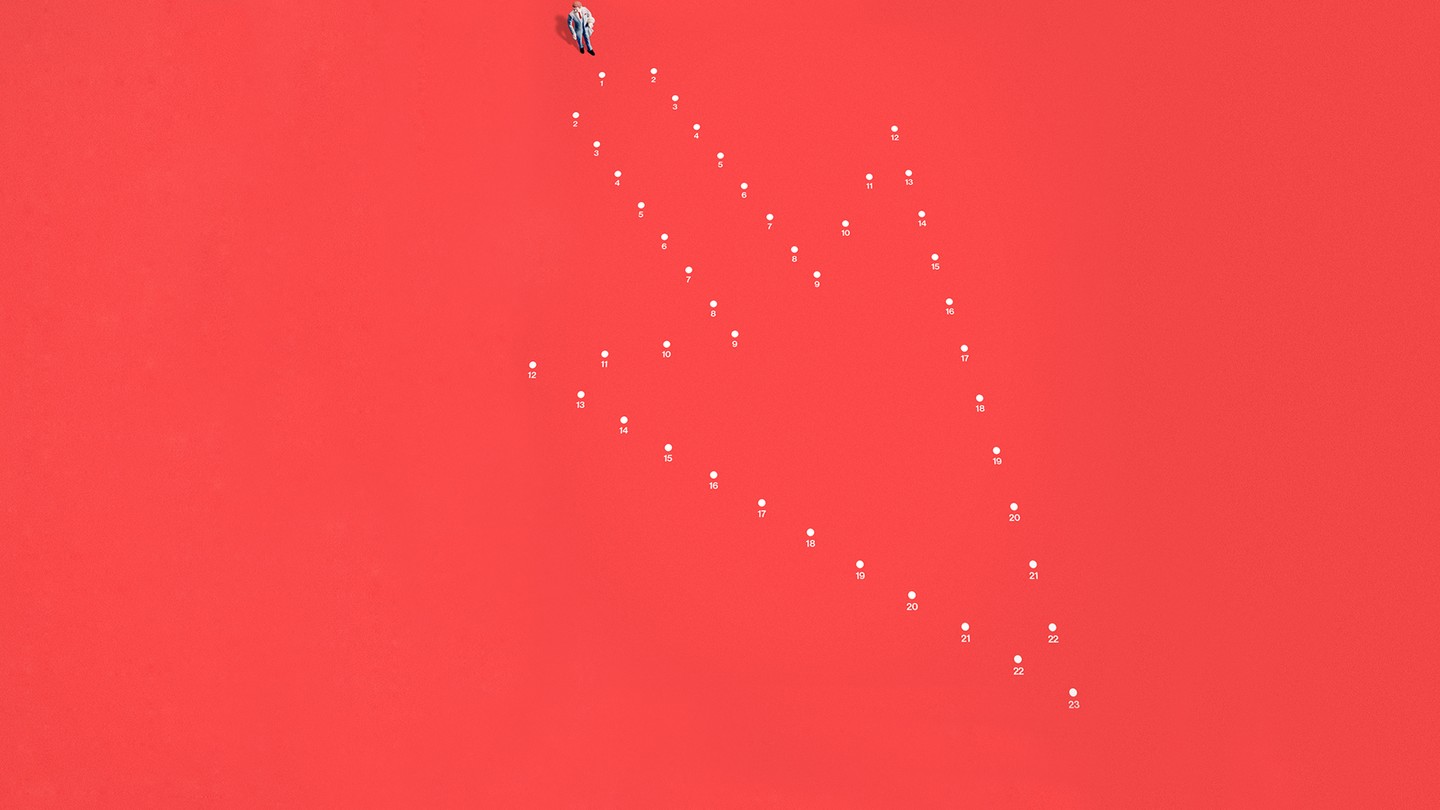

Others view freedom on the infamous “Garden of Forking Paths” model. For these people, free action requires more than merely the ability to do what you want to do. It also requires that you have the ability to do otherwise than what you actually did. So, If Anya is free when she decides to take a sip from her coffee, on this view, it must be the case that Anya could have refrained from sipping her coffee. The key to freedom, then, is alternative possibilities and we will call this the alternative possibilities view of free action.

Finally, some people envision freedom as requiring, not alternative possibilities but the right kind of relationship between the antecedent sources of our actions and the actions that we actually perform. Sometimes this view is explained by saying that the free agent is the source, perhaps even the ultimate source of her action. We will call this kind of view a source view of freedom.

Now, the key question we want to focus on is whether or not any of these three models of freedom are compatible with determinism. It could turn out that all three kinds of freedom are ruled out by determinism, so that the only way freedom is possible is if determinism is false. If you believe that determinism rules out free action, you endorse a view called incompatibilism. But it could turn out that one or all three of these models of freedom are compatible with determinism. If you believe that free action is compatible with determinism, you are a compatibilist.

Let us consider compatibilist views of freedom and two of the most formidable challenges that compatibilists face: the consequence argument and the ultimacy argument.

Begin with easy freedom. Is easy freedom compatible with determinism? A group of philosophers called classic compatibilists certainly thought so. 2 They argued that free will requires merely the ability for an agent to act without external hindrance. Suppose, right now, you want to put your textbook down and grab a cup of coffee. Even if determinism is true, you probably, right now, can do exactly that. You can put your textbook down, walk to the nearest Starbucks, and buy an overpriced cup of coffee. Nothing is stopping you from doing what you want to do. Determinism does not seem to be posing any threat to your ability to do what you want to do right now. If you want to stop reading and grab a coffee, you can. But, by contrast, if someone had chained you to the chair you are sitting in, things would be a bit different. Even if you wanted to grab a cup of coffee, you would not be able to. You would lack the ability to do so. You would not be free to do what you want to do. This has nothing to do with determinism, of course. It is not the fact that you might be living in a deterministic world that is threatening your free will. It is that an external hindrance (the chains holding you to your chair) is stopping from you doing what you want to do. So, if what we mean by freedom is easy freedom, it looks like freedom really is compatible with determinism.

Easy freedom has run into some rather compelling opposition, and most philosophers today agree that a plausible account of easy freedom is not likely. But, by far, the most compelling challenge the view faces can be seen in the consequence argument. 3 The consequence argument is as follows:

- If determinism is true, then all human actions are consequences of past events and the laws of nature.

- No human can do other than they actually do except by changing the laws of nature or changing the past.

- No human can change the laws of nature or the past.

- If determinism is true, no human has free will.

This is a powerful argument. It is very difficult to see where this argument goes wrong, if it goes wrong. The first premise is merely a restatement of determinism. The second premise ties the ability to do otherwise to the ability to change the past or the laws of nature, and the third premise points out the very reasonable assumption that humans are unable to modify the laws of nature or the past.

This argument effectively devastates easy freedom by proposing that we never act without external hindrances precisely because our actions are caused by past events and the laws of nature in such a way that we not able to contribute anything to the causal production of our actions. This argument also seems to pose a deeper problem for freedom in deterministic worlds. If this argument works, it establishes that, given determinism, we are powerless to do otherwise, and to the extent that freedom requires the ability to do otherwise, this argument seems to rule out free action. Note that if this argument works, it poses a challenge for both the easy and alternative possibilities view of free will.

How might someone respond to this argument? First, suppose you adopt an alternative possibilities view of freedom and believe that the ability to do otherwise is what is needed for genuine free will. What you would need to show is that alternative possibilities, properly understood, are not incompatible with determinism. Perhaps you might argue that if we understand the ability to do otherwise properly we will see that we actually do have the ability to change the laws of nature or the past.

That might sound counterintuitive. How could it possibly be the case that a mere mortal could change the laws of nature or the past? Think back to Quinn’s decision to spend the night before her exam out with friends instead of studying. When she shows up to her exam exhausted, and she starts blaming herself, she might say, “Why did I go out? That was dumb! I could have stayed home and studied.” And she is sort of right that she could have stayed home. She had the general ability to stay home and study. It is just that if she had stayed home and studied the past would be slightly different or the laws of nature would be slightly different. What this points to is that there might be a way of cashing out the ability to do otherwise that is compatible with determinism and does allow for an agent to kind of change the past or even the laws of nature. 4

But suppose we grant that the consequence argument demonstrates that determinism really does rule out alternative possibilities. Does that mean we must abandon the alternative possibilities view of freedom? Well, not necessarily. You could instead argue that free will is possible, provided determinism is false. 5 That is a big if, of course, but maybe determinism will turn out to be false.

What if determinism turns out to be true? Should we give up, then, and concede that there is no free will? Well, that might be too quick. A second response to the consequence argument is available. All you need to do is deny that freedom requires the ability to do otherwise.

In 1969, Harry Frankfurt proposed an influential thought experiment that demonstrated that free will might not require alternative possibilities at all (Frankfurt [1969] 1988). If he’s right about this, then the consequence argument, while compelling, does not demonstrate that no one lacks free will in deterministic worlds, because free will does not require the ability to do otherwise. It merely requires that agents be the source of their actions in the right kind of way. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Here is a simplified paraphrase of Frankfurt’s case:

Black wants Jones to perform a certain action. Black is prepared to go to considerable lengths to get his way, but he prefers to avoid unnecessary work. So he waits until Jones is about to make up his mind what to do, and he does nothing unless it is clear to him (Black is an excellent judge of such things) that Jones is going to decide not to do what Black wants him to do. If it does become clear that Jones is going to decide to do something other than what Black wanted him to do, Black will intervene, and ensure that Jones decides to do, and does do, exactly what Black wanted him to do. Whatever Jones’ initial preferences and inclinations, then, Black will have his way. As it turns out, Jones decides, on his own, to do the action that Black wanted him to perform. So, even though Black was entirely prepared to intervene, and could have intervened, to guarantee that Jones would perform the action, Black never actually has to intervene because Jones decided, for reasons of his own, to perform the exact action that Black wanted him to perform. (Frankfurt [1969] 1988, 6-7)

Now, what is going on here? Jones is overdetermined to perform a specific act. No matter what happens, no matter what Jones initially decides or wants to do, he is going to perform the action Black wants him to perform. He absolutely cannot do otherwise. But note that there seems to be a crucial difference between the case in which Jones decides on his own and for his own reasons to perform the action Black wanted him to perform and the case in which Jones would have refrained from performing the action were it not for Black intervening to force him to perform the action. In the first case, Jones is the source of his action. It the thing he decided to do and he does it for his own reasons. But in the second case, Jones is not the source of his actions. Black is. This distinction, thought Frankfurt, should be at the heart of discussions of free will and moral responsibility. The control required for moral responsibility is not the ability to do otherwise (Frankfurt [1969] 1988, 9-10).

If alternative possibilities are not what free will requires, what kind of control is needed for free action? Here we have the third view of freedom we started with: free will as the ability to be the source of your actions in the right kind of way. Source compatibilists argue that this ability is not threatened by determinism, and building off of Frankfurt’s insight, have gone on to develop nuanced, often radically divergent source accounts of freedom. 6 Should we conclude, then, that provided freedom does not require alternative possibilities that it is compatible with determinism? 7 Again, that would be too quick. Source compatibilists have reason to be particularly worried about an argument developed by Galen Strawson called the ultimacy argument (Strawson [1994] 2003, 212-228).

Rather than trying to establish that determinism rules out alternative possibilities, Strawson tried to show that determinism rules out the possibility of being the ultimate source of your actions. While this is a problem for anyone who tries to establish that free will is compatible with determinism, it is particularly worrying for source compatibilists as they’ve tied freedom to an agent’s ability to be source of its actions. Here is the argument:

- A person acts of her own free will only if she is the act’s ultimate source.

- If determinism is true, no one is the ultimate source of her actions.

- Therefore, if determinism is true, no one acts of her own free will. (McKenna and Pereboom 2016, 148) 8

This argument requires some unpacking. First of all, Strawson argues that for any given situation, we do what we do because of the way we are ([1994] 2003, 219). When Quinn decides to go out with her friends rather than study, she does so because of the way she is. She prioritizes a night with her friends over studying, at least on that fateful night before her exam. If Quinn had stayed in and studied, it would be because she was slightly different, at least that night. She would be such that she prioritized studying for her exam over a night out. But this applies to any decision we make in our lives. We decide to do what we do because of how we already are.

But if what we do is because of the way we are, then in order to be responsible for our actions, we need to be the source of how we are, at least in the relevant mental respects (Strawson [1994] 2003, 219). There is the first premise. But here comes the rub: the way we are is a product of factors beyond our control such as the past and the laws of nature ([1994] 2003, 219; 222-223). The fact that Quinn is such that she prioritizes a night with friends over studying is due to her past and the relevant laws of nature. It is not up to her that she is the way she is. It is ultimately factors extending well beyond her, possibly all the way back to the initial conditions of the universe that account for why she is the way she is that night. And to the extent that this is compelling, the ultimate source of Quinn’s decision to go out is not her. Rather, it is some condition of the universe external to her. And therefore, Quinn is not free.

Once again, this is a difficult argument to respond to. You might note that “ultimate source” is ambiguous and needing further clarification. Some compatibilists have pointed this out and argued that once we start developing careful accounts of what it means to be the source of our actions, we will see that the relevant notion of source-hood is compatible with determinism.

For example, while it may be true that no one is the ultimate cause of their actions in deterministic worlds precisely because the ultimate source of all actions will extend back to the initial conditions of the universe, we can still be a mediated source of our actions in the sense required for moral responsibility. Provided the actual source of our action involves a sophisticated enough set of capacities for it to make sense to view us as the source of our actions, we could still be the source of our actions, in the relevant sense (McKenna and Pereboom 2016, 154). After all, even if determinism is true, we still act for reasons. We still contemplate what to do and weigh reasons for and against various actions, and we still are concerned with whether or not the actions we are considering reflect our desires, our goals, our projects, and our plans. And you might think that if our actions stem from a history that includes us bringing all the features of our agency to bear upon the decision that is the proximal cause of our action, that this causal history is one in which we are the source of our actions in the way that is really relevant to identifying whether or not we are acting freely.

Others have noted that even if it is true that Quinn is not directly free in regard to the beliefs and desires that suggest she should go out with her friends rather than study (they are the product of factors beyond her control such as her upbringing, her environment, her genetics, or maybe even random luck), this need not imply that she lacks control as to whether or not she chooses to act upon them. 9 Perhaps it is the case that even though how we are may be due to factors beyond our control, nonetheless, we are still the source of what we do because it is still, even under determinism, up to us as to whether we choose to exercise control over our conduct.

Free Will and the Sciences

Many challenges to free will come, not from philosophy, but from the sciences. There are two main scientific arguments against free will, one coming from neuroscience and one coming from the social sciences. The concern coming from research in the neurosciences is that some empirical results suggest that all our choices are the result of unconscious brain processes, and to the extent choices must be consciously made to be free choices, it seems that we never make a conscious free choice.

The classic studies motivating a picture of human action in which unconscious brain processes are doing the bulk of the causal work for action were conducted by Benjamin Libet. Libet’s experiments involved subjects being asked to flex their wrists whenever they felt the urge to do so. Subjects were asked to note the location of a clock hand on a modified clock when they became aware of the urge to act. While doing this their brain activity was being scanned using EEG technology. What Libet noted is that around 550 milliseconds before a subject acted, a readiness potential (increased brain activity) would be measured by the EEG technology. But subjects were reporting awareness of an urge to flex their wrist around 200 milliseconds before they acted (Libet 1985).

This painted a strange picture of human action. If conscious intentions were the cause of our actions, you may expect to see a causal story in which the conscious awareness of an urge to flex your wrist shows up first, then a ramping up of brain activity, and finally an action. But Libet’s studies showed a causal story in which an action starts with unconscious brain activity, the subject later becomes consciously aware that they are about to act, and then the action happens. The conscious awareness of action seemed to be a byproduct of the actual unconscious process that was causing the action. It was not the cause of the action itself. And this result suggests that unconscious brain processes, not conscious ones, are the real causes of our actions. To the extent that free action requires our conscious decisions to be the initiating causes of our actions, it looks like we may never act freely.

While this research is intriguing, it probably does not establish that we are not free. Alfred Mele is a philosopher who has been heavily critical of these studies. He raises three main objections to the conclusions drawn from these arguments.

First, Mele points out that self-reports are notoriously unreliable (2009, 60-64). Conscious perception takes time, and we are talking about milliseconds. The actual location of the clock hand is probably much closer to 550 milliseconds when the agent “intends” or has the “urge” to act than it is to 200 milliseconds. So, there’s some concerns about experimental design here.

Second, an assumption behind these experiments is that what is going on at 550 milliseconds is that a decision is being made to flex the wrist (Mele 2014, 11). We might challenge this assumption. Libet ran some variants of his experiment in which he asked subjects to prepare to flex their wrist but to stop themselves from doing so. So, basically, subjects simply sat there in the chair and did nothing. Libet interpreted the results of these experiments as showing that we might not have a free will, but we certainly have a “free won’t” because we seem capable of consciously vetoing or stopping an action, even if that action might be initiated by unconscious processes (2014, 12-13). Mele points out that what might be going on in these scenarios is that the real intention to act or not act is what happens consciously at 200 milliseconds, and if so, there is little reason to think these experiments are demonstrating that we lack free will (2014, 13).

Finally, Mele notes that while it may be the case that some of our decisions and actions look like the wrist-flicking actions Libet was studying, it is doubtful that all or even most of our decisions are like this (2014, 15). When we think about free will, we rarely think of actions like wrist-flicking. Free actions are typically much more complex and they are often the kind of thing where the decision to do something extends across time. For example, your decision about what to major in at college or even where to study was probably made over a period of months, even years. And that decision probably involved periods of both conscious and unconscious cognition. Why think that a free choice cannot involve some components that are unconscious?

A separate line of attack on free will comes from the situationist literature in the social sciences (particularly social psychology). There is a growing body of research suggesting that situational and environmental factors profoundly influence human behavior, perhaps in ways that undermine free will (Mele 2014, 72).

Many of the experiments in the situationist literature are among the most vivid and disturbing in all of social psychology. Stanley Milgram, for example, conducted a series of experiments on obedience in which ordinary people were asked to administer potentially lethal voltages of electricity to an innocent subject in order to advance scientific research, and the vast majority of people did so! 10 And in Milgram’s experiments, what affected whether or not subjects were willing to administer the shocks were minor, seemingly insignificant environmental factors such as whether the person running the experiment looked professional or not (Milgram 1963).

What experiments like Milgram’s obedience experiments might show is that it is our situations, our environments that are the real causes of our actions, not our conscious, reflective choices. And this may pose a threat to free will. Should we take this kind of research as threatening freedom?

Many philosophers would resist concluding that free will does not exist on the basis of these kinds of experiments. Typically, not everyone who takes part in situationist studies is unable to resist the situational influences they are subject to. And it appears to be the case that when we are aware of situational influences, we are more likely to resist them. Perhaps the right way to think about this research is that there all sorts of situations that can influence us in ways that we may not consciously endorse, but that nonetheless, we are still capable of avoiding these effects when we are actively trying to do so. For example, the brain sciences have made many of us vividly aware of a whole host of cognitive biases and situational influences that humans are typically subject to and yet, when we are aware of these influences, we are less susceptible to them. The more modest conclusion to draw here is not that we lack free will, but that exercising control over our actions is much more difficult than many of us believe it to be. We are certainly influenced by the world we are a part of, but to be influenced by the world is different from being determined by it, and this may allow us to, at least sometimes, exercise some control over the actions we perform.

No one knows yet whether or not humans sometimes exercise the control over their actions required for moral responsibility. And so I leave it to you, dear reader: Are you free?

Chapter Notes

- I have hidden some complexity here. I have defined determinism in terms of logical entailment. Sometimes people talk about determinism as a causal relationship. For our purposes, this distinction is not relevant, and if it is easier for you to make sense of determinism by thinking of the past and the laws of nature causing all future events, that is perfectly acceptable to do.

- Two of the more well-known classic compatibilists include Thomas Hobbes and David Hume. See: Hobbes, Thomas, (1651) 1994, Leviathan , ed. Edwin Curley, Canada: Hackett Publishing Company; and Hume, David, (1739) 1978, A Treatise of Human Nature , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- For an earlier version of this argument see: Ginet, Carl, 1966, “Might We Have No Choice?” in Freedom and Determinism, ed. Keith Lehrer, 87-104, Random House.

- For two notable attempts to respond to the consequence argument by claiming that humans can change the past or the laws of nature see: Fischer, John Martin, 1994, The Metaphysics of Free Will , Oxford: Blackwell Publishers; and Lewis, David, 1981, “Are We Free to Break the Laws?” Theoria 47: 113-21.

- Many philosophers try to develop views of freedom on the assumption that determinism is incompatible with free action. The view that freedom is possible, provided determinism is false is called Libertarianism. For more on Libertarian views of freedom, see: Clarke, Randolph and Justin Capes, 2017, “Incompatibilist (Nondeterministic) Theories of Free Will,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/incompatibilism-theories/ .

- For elaboration on recent compatibilist views of freedom, see McKenna, Michael and D. Justin Coates, 2015, “Compatibilism,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/compatibilism/ .

- You might be unimpressed by the way source compatibilists understand the ability to be the source of your actions. For example, you might that what it means to be the source of your actions is to be the ultimate cause of your actions. Or maybe you think that to genuinely be the source of your actions you need to be the agent-cause of your actions. Those are both reasonable positions to adopt. Typically, people who understand free will as requiring either of these abilities believe that free will is incompatible with determinism. That said, there are many Libertarian views of free will that try to develop a plausible account of agent causation. These views are called Agent-Causal Libertarianism. See: Clarke, Randolph and Justin Capes, 2017, “Incompatibilist (Nondeterministic) Theories of Free Will,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/incompatibilism-theories/ .

- As with most philosophical arguments, the ultimacy argument has been formulated in a number of different ways. In Galen Strawson’s original paper he gives three different versions of the argument, one of which has eight premises and one that has ten premises. A full treatment of either of those versions of this argument would require more time and space than we have available here. I have chosen to use the McKenna/Pereboom formulation of the argument due its simplicity and their clear presentation of the central issues raised by the argument.

- For two attempts to respond to the ultimacy argument in this way, see: Mele, Alfred, 1995, Autonomous Agents , New York: Oxford University Press; and McKenna, Michael, 2008, “Ultimacy & Sweet Jane” in Nick Trakakis and Daniel Cohen, eds, Essays on Free Will and Moral Responsibility , Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 186-208.

- Fortunately, no real shocks were administered. The subjects merely believed they were doing so.

Frankfurt, Harry. (1969) 1988. “Alternative Possibilities and moral responsibility.” In The Importance of What We Care About: Philosophical Essays , 10th ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Libet, Benjamin. 1985. “Unconscious Cerebral Initiative and the Role of Conscious Will in Voluntary Action.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 8: 529-566.

McKenna, Michael and Derk Pereboom. 2016. Free Will: A Contemporary Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Mele, Alfred. 2014. Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mele, Alfred. 2009. Effective Intentions: The Power of Conscious Will. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Milgram, Stanley. 1963. “Behavioral Study of Obedience.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67: 371-378.

Strawson, Galen. (1994) 2003. “The Impossibility of Moral Responsibility.” In Free Will, 2nd ed. Edited by Gary Watson, 212-228. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Inwagen, Peter. 1983. An Essay on Free Will. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Further Reading

Deery, Oisin and Paul Russell, eds. 2013. The Philosophy of Free Will: Essential Readings from the Contemporary Debates . New York: Oxford University Press.

Mele, Alfred. 2006. Free Will and Luck. New York: Oxford University Press.

Attribution

This section is composed of text taken from Chapter 8 Freedom of the Will created by Daniel Haas in Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind , edited by Heather Salazar and Christina Hendricks, and produced with support from the Rebus Community. The original is freely available under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 license at https://press.rebus.community/intro-to-phil-of-mind/ . The material is presented in its original form, with the exception of the removal of introductory material Introduction: Are We Free?

A Brief Introduction to Philosophy Copyright © 2021 by Southern Alberta Institution of Technology (SAIT) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Foreknowledge and Free Will

Fatalism is the thesis that human acts occur by necessity and hence are unfree. Theological fatalism is the thesis that infallible foreknowledge of a human act makes the act necessary and hence unfree. If there is a being who knows the entire future infallibly, then no human act is free.

Fatalism seems to be entailed by infallible foreknowledge by the following informal line of reasoning:

For any future act you will perform, if some being infallibly believed in the past that the act would occur, there is nothing you can do now about the fact that he believed what he believed since nobody has any control over past events; nor can you make him mistaken in his belief, given that he is infallible. Therefore, there is nothing you can do now about the fact that he believed in a way that cannot be mistaken that you would do what you will do. But if so, you cannot do otherwise than what he believed you would do. And if you cannot do otherwise, you will not perform the act freely.

The same argument can be applied to any infallibly foreknown act of any human being. If there is a being who infallibly knows everything that will happen in the future, no human being has any control over the future.

This theological fatalist argument creates a dilemma for anyone who thinks it important to maintain both (1) there is a deity who infallibly knows the entire future, and (2) human beings have free will in the strong sense usually called libertarian. But it has also fascinated many who have not shared either of these commitments, because taking the argument’s full measure requires rethinking some of the most fundamental questions in philosophy, especially ones concerning time, truth, and modality. Those philosophers who think there is a way to consistently maintain both (1) and (2) are called compatibilists about infallible foreknowledge and human free will. Compatibilists must either identify a false premise in the argument for theological fatalism or show that the conclusion does not follow from the premises. Incompatibilists accept the incompatibility of infallible foreknowledge and human free will and deny either infallible foreknowledge or free will in the sense targeted by the argument.

1. The argument for theological fatalism

2.1 the denial of future contingent truth, 2.2 god’s knowledge of future contingent truths, 2.3 the eternity solution, 2.4 god’s forebeliefs as “soft facts” about the past, 2.5 the dependence solution, 2.6 the transfer of necessity, 2.7 the necessity and the causal closure of the past.

- 2.8 The rejection of Principle of Alternate Possibilities (PAP)

3. Incompatibilist responses to the argument for theological fatalism

4. logical fatalism.

- 5. Beyond fatalism

Other Internet Resources

Related entries.

There is a long history of debate over the soundness of the argument for theological fatalism, so its soundness must not be obvious. Nelson Pike (1965) gets the credit for clearly and forcefully presenting the dilemma in a way that produced an enormous body of work by both compatibilists and incompatibilists, leading to more careful formulations of the argument.

A precise version of the argument can be formulated as follows: Choose some proposition about a future act that you think you will do freely, if any act is free. Suppose, for example, that the telephone will ring at 9 am tomorrow and you will either answer it or you will not. So it is either true that you will answer the phone at 9 am tomorrow or it is true that you will not answer the phone at 9 am tomorrow. The Law of Excluded Middle rules out any other alternative. Let T abbreviate the proposition that you will answer the phone tomorrow morning at 9, and let us suppose that T is true. (If not- T is true instead, simply substitute not- T in the argument below).

Let “now-necessary” designate temporal necessity, the type of necessity that the past is supposed to have just because it is past. This type of necessity plays a central role in the argument and we’ll have more to say about it in sections 2.4, 2.5, 2.7 , and 5 , but we can begin with the intuitive idea that there is a kind of necessity that a proposition has now when the content of the proposition is about something that occurred in the past. To say that it is now-necessary that milk has been spilled is to say nobody can do anything now about the fact that the milk has been spilled.

Let “God” designate a being who has infallible beliefs about the future, where to say that God believes p infallibly is to say that God believes p and it is not possible that God believes p and p is false. It is not important for the logic of the argument that God is the being worshiped by any particular religion, but the motive to maintain that there is a being with infallible beliefs is usually a religious one.

One more preliminary point is in order. The dilemma of infallible foreknowledge and human free will does not rest on the particular assumption of fore knowledge and does not require an analysis of knowledge. Most contemporary accounts of knowledge are fallibilist, which means they do not require that a person believe in a way that cannot be mistaken in order to have knowledge. She has knowledge just in case what she believes is true and she satisfies the other conditions for knowledge, such as having sufficiently strong evidence. Ordinary knowledge does not require that the belief cannot be false. For example, if I believe on strong evidence that classes begin at my university on a certain date, and when the day arrives, classes do begin, we would normally say I knew in advance that classes would begin on that date. I had foreknowledge about the date classes begin. But there is nothing problematic about that kind of foreknowledge because events could have proven me wrong even though as events actually turned out, they didn’t prove me wrong. Ordinary foreknowledge does not threaten to necessitate the future because it does not require that when I know p it is not possible that my belief is false. The key problem, then, is the infallibility of the belief about the future, and this is a problem whether or not the epistemic agent with an infallible belief satisfies the other conditions required by some account of knowledge, such as sufficient evidence. As long as an agent has an infallible belief about the future, the problem arises.

Using the example of the proposition T , the argument that infallible foreknowledge of T entails that you do not answer the telephone freely can be formulated as follows:

Basic Argument for Theological Fatalism

This argument is formulated in a way that makes its logical form as perspicuous as possible, and there is a consensus that this argument or something close to it is valid. That is, if the premises are all true, the conclusion follows. The compatibilist about infallible foreknowledge and free will must therefore find a false premise. There are four premises that are not straightforward substitutions in definitions: (1), (2), (5), and (9). All four of these premises have come under attack in the history of discussion of theological fatalism. Aristotle’s concern about future contingent truth has motivated an increasing number of compatibilists to challenge premise (1). Boethius and Aquinas also denied premise (1), but on the grounds that God and his beliefs are not in time, a solution that has always had some adherents. William of Ockham rejected premise (2), arguing that the necessity of the past does not apply to the entire past, and God’s past beliefs are in the part of the past to which the necessity of the past does not apply. This approach to the problem was revived early in the debate stirred up by Pike’s article, and has probably attracted more attention, in its various incarnations, than any other solution. There are more radical responses to (2) as well. Premise (5) has rarely been disputed and is an analogue of an axiom of modal logic, but it may have been denied by Duns Scotus and Luis de Molina. Although doubts about premise (9) arose relatively late in the debate, inspired by contemporary discussions of the relation between free will and the ability to do otherwise, the denial of (9) is arguably the key to the solution proposed by Augustine. In addition to the foregoing compatibilist solutions, there are two incompatibilist responses to the problem of theological fatalism. One is to deny that God (or any being) has infallible foreknowledge. The other is to deny that human beings have free will in the libertarian sense of free will. These responses will be discussed in section 3 . The relationship between theological fatalism and logical fatalism will be discussed in section 4 . In section 5 we will consider whether the problem of theological fatalism is just a theological version of a more general problem in metaphysics that isn’t ultimately about God, or even about free will.

2. Compatibilist responses to theological fatalism

One response to the dilemma of infallible foreknowledge and free will is to deny that the proposition T can be true, on the grounds that no proposition about the contingent future is true: such propositions are either false (given Bivalence), or neither true nor false. This response rejects the terms in which the problem is set up. Since God wouldn’t believe a proposition unless it were true, premise (1) is, on this account, a non-starter. The idea behind this response is usually that propositions about the contingent future become true when and only when the event occurs that the proposition is about. If the event does not occur at that time, then the proposition becomes false. This seems to have been the position of Aristotle in the famous Sea Battle argument of De Interpretatione IX, where Aristotle is concerned with the implications of the truth of a proposition about the future, not the problem of infallible knowledge of the future. But some philosophers have used Aristotle’s move to solve the dilemma we are addressing here.

This approach to the problem had already been endorsed, three years before Pike’s seminal article, by A.N. Prior (1962), but it received little initial attention. John Martin Fischer’s first anthology of essays on the problem (1989) does not contain a single paper advocating this solution. It wasn’t until the 1980s, when it was defended by Joseph Runzo (1981), Richard Purtill (1988), and J.R. Lucas (1989), that it began to gain traction in the debate. More recently, Alan Rhoda, Gregory Boyd, and Thomas Belt (2006) have argued for the “Peircean” semantics favored by Prior (1967, 113–36), on which the predictive use of the word ‘will’ carries maximal causal force and all future contingents turn out false, while Dale Tuggy (2007) has defended the position that future contingents are neither true nor false. A critique of both Rhoda et al . and Tuggy may be found in Craig and Hunt (2013). Another supporter of the all-future-contingents-are-false solution to the problem of theological fatalism is Patrick Todd (2016a), whose recent book (2021) offers a vigorous defense of this approach against various objections. Many (but not all) of those who reject future contingent truth base their position, at least in part, on presentism, according to which only the present exists. Statements about the future, especially the contingent future, would then arguably lack the grounding necessary for truth. D.K. Johnson (2009) has taken up this solution to both logical and theological fatalism, as has Dean Zimmerman (2008). A measure of how much the debate has shifted in this direction is that Fischer’s second anthology (Fischer and Todd 2015) contains an entire section on “The Logic of Future Contingents.” The connection between this solution and “open theism” will be discussed in section 3 .

While there is considerable prima facie appeal to the idea that statements about the contingent future aren’t yet true, and that they become true only when the future arrives, both the semantic and the metaphysical justifications for this idea can be challenged. A semantics that collapses truth into necessity and falsehood into impossibility, at least for propositions about the future, may appear insufficiently attentive to people’s actual use of the predictive ‘will’, not to mention logically problematic. The true futurist theory (“the thin red line”), allowing for future contingent truth, is defended by Øhrstrøm (2009) and by Malpass and Wawer (2012). Presentist opponents of future contingent truth, for their part, need to explain how there can be contingent truths about the past but not about the future, given that, on presentism, the past is no more real than the future. (This is not a problem on the growing block theory.) Rhoda (2009) and Zimmerman (2010), for example, have independently suggested that truths about the past could be grounded in God’s present beliefs about the past; but if this move is allowed, it would seem just as legitimate to assume God has present beliefs about the future and use this to ground truths about the contingent future. The semantic and metaphysical issues surrounding future contingent truth are complex and highly contested, so it isn’t possible to do more than note them here.

It is not clear, however, that the denial of future contingent truth is sufficient to avoid the problem of theological fatalism. Hunt (2020) suggests that future contingents that fail to be true for presentist reasons alone might nevertheless qualify as “quasi-true” (Sider 1999, Markosian 2004), and argues that the quasi-truth of God’s beliefs about the future is enough to generate the problem. The following consideration tends in the same direction. According to the definition of infallibility used in the basic argument, if God is infallible in all his beliefs, then it is not possible that God believes T and T is false. But there is a natural extension of the definition of infallibility to allow for the case in which T lacks a truth value but will acquire one in the future: If God is infallible in all his beliefs, then it is not possible that God believes T and T is either false or becomes false. If so, and if God believes T , we get an argument for theological fatalism that parallels our basic argument. Premise (4) would need to be modified as follows:

(6) becomes:

The modifications in the rest of the argument are straightforward.

It is open to the defender of this solution to maintain that God has no beliefs about the contingent future because he does not infallibly know how it will turn out, and this is compatible with God’s being infallible in everything he does believe. It is also compatible with God’s omniscience if omniscience is the property of knowing the truth value of every proposition that has a truth value. But clearly, this move restricts the range of God’s knowledge, so it has religious disadvantages in addition to its disadvantages in logic.

If T is true, there is still the question how God could come to believe T rather than not- T , and believe it without any possibility of error, given that T concerns the contingent future. T is contingent only insofar as it is still possible for you to refrain from answering the phone at 9 tomorrow morning, though we’re supposing for the sake of argument that you will answer the phone at 9. But then it’s still possible for T to turn out false (though it won’t), and still possible for the belief that T to be incorrect (though it isn’t). This is hard to square with the claim in premise (1) that God’s belief that T was infallible.

This problem for infallible belief about a contingent future parallels a problem for God’s knowledge of a contingent future. Though the argument for theological fatalism rests only on divine belief rather than knowledge (since the additional conditions for knowledge, beyond true belief, don’t play any role in the argument), God nevertheless wouldn’t believe without knowing. But it’s unclear what could have been cognitively available to God yesterday, when your answering the phone at 9 am tomorrow was still future and contingent, to raise his belief that T from a correct guess to genuine knowledge. Prior (1962) held this to be a further problem for premise (1), beyond the nonexistence of future contingent truths. For William Hasker (1989, 186–88), Richard Swinburne (2006, 22–26), and Peter van Inwagen (2008), who maintain (contrary to Prior) that there are future contingent truths, the impossibility of foreknowing them is the problem with premise (1). This “limited foreknowledge” view has been critiqued by Arbour (2013) and Todd (2014a), among others.

Defenders of divine foreknowledge need something to say in response to skeptical questions about how such knowledge could be available to God. One possible response is that it’s a conceptual truth that God is omniscient, and his knowledge, including his knowledge of future contingent truths, is simply innate (Craig 1987). Skeptics might regard this response as closer to a non-response. But others have offered detailed if speculative proposals. These include Ryan Byerly (2014), whose book-length treatment of the issue grounds God’s infallible foreknowledge in a divine “ordering of times” that is supposed to leave human free will intact.

It is relatively easy to see how God can know what is (contingently) “going to” happen if this refers to the present tendency of things. All it takes is exhaustive knowledge of the present. But what is “going to” happen can change, as the present tendency of things changes, and what God foreknows on this basis (his knowledge of what is going to happen ) will change along with this change in present tendencies. This “mutable future” position, defended by Peter Geach, has been revived by Patrick Todd (2011, 2016b). On the “Geachian” view, God’s beliefs about the contingent future constitute genuine knowledge, because they track the changing truth about where the future is headed. What this view doesn’t provide is the infallibility required by premise (1).

Fischer (2016, 31–45) tries to fill the gap with his “boot-strapping” account of divine foreknowledge. Even human beings are sometimes in a “knowledge-conferring situation,” or KCS, with respect to the contingent future. Since God would be aware of all the evidence and other knowledge-conferring factors that human beings are aware of in such situations, God is in a position to know (some) future contingents in the same way that human beings can know them: by being in the appropriate KCS. But this presupposes a fallibilist theory of knowledge. What accounts for the infallibility of God’s beliefs? Fischer argues that God can “bootstrap” his way to certainty by combining his beliefs about the contingent future with self-knowledge of his own infallibility. Hunt (2017b) objects that the account is circular, and that it couldn’t support anything close to exhaustive foreknowledge, since most future contingent truths will lack KCS’s at any given time. Fischer (2017, and forthcoming) elaborates and defends the view.

The most straightforward account of the matter, accommodating the infallibility of God’s beliefs, is that he simply “sees” the future. If God is in time, this requires that he be equipped with something like a “time telescope” that allows him to view what is temporally distant. A hurdle faced by time telescopes is that they probably involve retrocausation. If God is not in time, however, he wouldn’t need a time telescope to view the future along with the present and past. This brings us to the next solution.

A third challenge to premise (1), independent of the first two, is that it misrepresents God’s relation to time. What is denied according to this solution is not that God believes infallibly, and not that God believes the content of proposition T , but that God believed T yesterday . This solution probably originated with the 6 th century philosopher Boethius, who maintained that God is not in time and has no temporal properties, so God does not have beliefs at a time. It is therefore a mistake to say God had beliefs yesterday, or has beliefs today, or will have beliefs tomorrow. It is also a mistake to say God had a belief on a certain date, such as June 1, 2004. The way Boethius describes God’s cognitive grasp of temporal reality, all temporal events are before the mind of God at once. To say “at once” or “simultaneously” is to use a temporal metaphor, but Boethius is clear that it does not make sense to think of the whole of temporal reality as being before God’s mind in a single temporal present. It is an atemporal present in which God has a single complete grasp of all events in the entire span of time.

Aquinas adopted the Boethian solution as one of his ways out of theological fatalism, using some of the same metaphors as Boethius. One is the circle analogy, in which the way a timeless God is present to each and every moment of time is compared to the way in which the center of a circle is present to each and every point on its circumference ( SCG I, 66). In contemporary philosophy an important defense of the Boethian idea that God is timeless was given by Eleonore Stump and Norman Kretzmann (1981), who applied it explicitly to the foreknowledge dilemma (1991). Recently it has been defended by Katherin Rogers (2007a, 2007b), Kevin Timpe (2007), Michael Rota (2010), Joseph Diekemper (2013), and Ciro De Florio (2015).

Most objections to the timelessness solution to the dilemma of foreknowledge and freedom focus on the idea of timelessness itself, arguing either that it does not make sense or that it is incompatible with other properties of God that are religiously more compelling, such as personhood (e.g., Pike 1970, 121–129; Wolterstorff 1975; Swinburne 1977, 221). Zagzebski has argued (1991, chap. 2 and 2011) that the timelessness move does not avoid the problem of theological fatalism since an argument structurally parallel to the basic argument can be formulated for timeless knowledge. If God is not in time, the key issue would not be the necessity of the past, but the necessity of the timeless realm. So the first three steps of the argument would be reformulated as follows:

Perhaps it is inappropriate to say that timeless events such as God’s timeless knowing are now -necessary, yet we have no more reason to think we can do anything about God’s timeless knowing than about God’s past knowing. The timeless realm is as much out of our reach as the past. So the point of (3t) is that we cannot now do anything about the fact that God timelessly knows T . The rest of the steps in the timeless dilemma argument are parallel to the basic argument. Step (5t) says that if there is nothing we can do about a timeless state, there is nothing we can do about what such a state entails. It follows that we cannot do anything about the future.

The Boethian solution does not solve the problem of theological fatalism by itself, but since the nature of the timeless realm is elusive, the intuition of the necessity of the timeless realm is probably weaker than the intuition of the necessity of the past. The necessity of the past is deeply embedded in our ordinary intuitions about time; there are no ordinary intuitions about the realm of timelessness. One possible way out of this problem is given by K.A. Rogers, who argues (2007a, 2007b) that the eternal realm is like the present rather than the past, and so it does not have the necessity we attribute to the past.