- Our Mission

Why Students Cheat—and What to Do About It

A teacher seeks answers from researchers and psychologists.

“Why did you cheat in high school?” I posed the question to a dozen former students.

“I wanted good grades and I didn’t want to work,” said Sonya, who graduates from college in June. [The students’ names in this article have been changed to protect their privacy.]

My current students were less candid than Sonya. To excuse her plagiarized Cannery Row essay, Erin, a ninth-grader with straight As, complained vaguely and unconvincingly of overwhelming stress. When he was caught copying a review of the documentary Hypernormalism , Jeremy, a senior, stood by his “hard work” and said my accusation hurt his feelings.

Cases like the much-publicized ( and enduring ) 2012 cheating scandal at high-achieving Stuyvesant High School in New York City confirm that academic dishonesty is rampant and touches even the most prestigious of schools. The data confirms this as well. A 2012 Josephson Institute’s Center for Youth Ethics report revealed that more than half of high school students admitted to cheating on a test, while 74 percent reported copying their friends’ homework. And a survey of 70,000 high school students across the United States between 2002 and 2015 found that 58 percent had plagiarized papers, while 95 percent admitted to cheating in some capacity.

So why do students cheat—and how do we stop them?

According to researchers and psychologists, the real reasons vary just as much as my students’ explanations. But educators can still learn to identify motivations for student cheating and think critically about solutions to keep even the most audacious cheaters in their classrooms from doing it again.

Rationalizing It

First, know that students realize cheating is wrong—they simply see themselves as moral in spite of it.

“They cheat just enough to maintain a self-concept as honest people. They make their behavior an exception to a general rule,” said Dr. David Rettinger , professor at the University of Mary Washington and executive director of the Center for Honor, Leadership, and Service, a campus organization dedicated to integrity.

According to Rettinger and other researchers, students who cheat can still see themselves as principled people by rationalizing cheating for reasons they see as legitimate.

Some do it when they don’t see the value of work they’re assigned, such as drill-and-kill homework assignments, or when they perceive an overemphasis on teaching content linked to high-stakes tests.

“There was no critical thinking, and teachers seemed pressured to squish it into their curriculum,” said Javier, a former student and recent liberal arts college graduate. “They questioned you on material that was never covered in class, and if you failed the test, it was progressively harder to pass the next time around.”

But students also rationalize cheating on assignments they see as having value.

High-achieving students who feel pressured to attain perfection (and Ivy League acceptances) may turn to cheating as a way to find an edge on the competition or to keep a single bad test score from sabotaging months of hard work. At Stuyvesant, for example, students and teachers identified the cutthroat environment as a factor in the rampant dishonesty that plagued the school.

And research has found that students who receive praise for being smart—as opposed to praise for effort and progress—are more inclined to exaggerate their performance and to cheat on assignments , likely because they are carrying the burden of lofty expectations.

A Developmental Stage

When it comes to risk management, adolescent students are bullish. Research has found that teenagers are biologically predisposed to be more tolerant of unknown outcomes and less bothered by stated risks than their older peers.

“In high school, they’re risk takers developmentally, and can’t see the consequences of immediate actions,” Rettinger says. “Even delayed consequences are remote to them.”

While cheating may not be a thrill ride, students already inclined to rebel against curfews and dabble in illicit substances have a certain comfort level with being reckless. They’re willing to gamble when they think they can keep up the ruse—and more inclined to believe they can get away with it.

Cheating also appears to be almost contagious among young people—and may even serve as a kind of social adhesive, at least in environments where it is widely accepted. A study of military academy students from 1959 to 2002 revealed that students in communities where cheating is tolerated easily cave in to peer pressure, finding it harder not to cheat out of fear of losing social status if they don’t.

Michael, a former student, explained that while he didn’t need to help classmates cheat, he felt “unable to say no.” Once he started, he couldn’t stop.

Technology Facilitates and Normalizes It

With smartphones and Alexa at their fingertips, today’s students have easy access to quick answers and content they can reproduce for exams and papers. Studies show that technology has made cheating in school easier, more convenient, and harder to catch than ever before.

To Liz Ruff, an English teacher at Garfield High School in Los Angeles, students’ use of social media can erode their understanding of authenticity and intellectual property. Because students are used to reposting images, repurposing memes, and watching parody videos, they “see ownership as nebulous,” she said.

As a result, while they may want to avoid penalties for plagiarism, they may not see it as wrong or even know that they’re doing it.

This confirms what Donald McCabe, a Rutgers University Business School professor, reported in his 2012 book ; he found that more than 60 percent of surveyed students who had cheated considered digital plagiarism to be “trivial”—effectively, students believed it was not actually cheating at all.

Strategies for Reducing Cheating

Even moral students need help acting morally, said Dr. Jason M. Stephens , who researches academic motivation and moral development in adolescents at the University of Auckland’s School of Learning, Development, and Professional Practice. According to Stephens, teachers are uniquely positioned to infuse students with a sense of responsibility and help them overcome the rationalizations that enable them to think cheating is OK.

1. Turn down the pressure cooker. Students are less likely to cheat on work in which they feel invested. A multiple-choice assessment tempts would-be cheaters, while a unique, multiphase writing project measuring competencies can make cheating much harder and less enticing. Repetitive homework assignments are also a culprit, according to research , so teachers should look at creating take-home assignments that encourage students to think critically and expand on class discussions. Teachers could also give students one free pass on a homework assignment each quarter, for example, or let them drop their lowest score on an assignment.

2. Be thoughtful about your language. Research indicates that using the language of fixed mindsets , like praising children for being smart as opposed to praising them for effort and progress , is both demotivating and increases cheating. When delivering feedback, researchers suggest using phrases focused on effort like, “You made really great progress on this paper” or “This is excellent work, but there are still a few areas where you can grow.”

3. Create student honor councils. Give students the opportunity to enforce honor codes or write their own classroom/school bylaws through honor councils so they can develop a full understanding of how cheating affects themselves and others. At Fredericksburg Academy, high school students elect two Honor Council members per grade. These students teach the Honor Code to fifth graders, who, in turn, explain it to younger elementary school students to help establish a student-driven culture of integrity. Students also write a pledge of authenticity on every assignment. And if there is an honor code transgression, the council gathers to discuss possible consequences.

4. Use metacognition. Research shows that metacognition, a process sometimes described as “ thinking about thinking ,” can help students process their motivations, goals, and actions. With my ninth graders, I use a centuries-old resource to discuss moral quandaries: the play Macbeth . Before they meet the infamous Thane of Glamis, they role-play as medical school applicants, soccer players, and politicians, deciding if they’d cheat, injure, or lie to achieve goals. I push students to consider the steps they take to get the outcomes they desire. Why do we tend to act in the ways we do? What will we do to get what we want? And how will doing those things change who we are? Every tragedy is about us, I say, not just, as in Macbeth’s case, about a man who succumbs to “vaulting ambition.”

5. Bring honesty right into the curriculum. Teachers can weave a discussion of ethical behavior into curriculum. Ruff and many other teachers have been inspired to teach media literacy to help students understand digital plagiarism and navigate the widespread availability of secondary sources online, using guidance from organizations like Common Sense Media .

There are complicated psychological dynamics at play when students cheat, according to experts and researchers. While enforcing rules and consequences is important, knowing what’s really motivating students to cheat can help you foster integrity in the classroom instead of just penalizing the cheating.

Why Do Students Cheat?

- Posted July 19, 2016

- By Zachary Goldman

In March, Usable Knowledge published an article on ethical collaboration , which explored researchers’ ideas about how to develop classrooms and schools where collaboration is nurtured but cheating is avoided. The piece offers several explanations for why students cheat and provides powerful ideas about how to create ethical communities. The article left me wondering how students themselves might respond to these ideas, and whether their experiences with cheating reflected the researchers’ understanding. In other words, how are young people “reading the world,” to quote Paulo Freire , when it comes to questions of cheating, and what might we learn from their perspectives?

I worked with Gretchen Brion-Meisels to investigate these questions by talking to two classrooms of students from Massachusetts and Texas about their experiences with cheating. We asked these youth informants to connect their own insights and ideas about cheating with the ideas described in " Ethical Collaboration ." They wrote from a range of perspectives, grappling with what constitutes cheating, why people cheat, how people cheat, and when cheating might be ethically acceptable. In doing so, they provide us with additional insights into why students cheat and how schools might better foster ethical collaboration.

Why Students Cheat

Students critiqued both the individual decision-making of peers and the school-based structures that encourage cheating. For example, Julio (Massachusetts) wrote, “Teachers care about cheating because its not fair [that] students get good grades [but] didn't follow the teacher's rules.” His perspective represents one set of ideas that we heard, which suggests that cheating is an unethical decision caused by personal misjudgment. Umna (Massachusetts) echoed this idea, noting that “cheating is … not using the evidence in your head and only using the evidence that’s from someone else’s head.”

Other students focused on external factors that might make their peers feel pressured to cheat. For example, Michima (Massachusetts) wrote, “Peer pressure makes students cheat. Sometimes they have a reason to cheat like feeling [like] they need to be the smartest kid in class.” Kayla (Massachusetts) agreed, noting, “Some people cheat because they want to seem cooler than their friends or try to impress their friends. Students cheat because they think if they cheat all the time they’re going to get smarter.” In addition to pressure from peers, students spoke about pressure from adults, pressure related to standardized testing, and the demands of competing responsibilities.

When Cheating is Acceptable

Students noted a few types of extenuating circumstances, including high stakes moments. For example, Alejandra (Texas) wrote, “The times I had cheated [were] when I was failing a class, and if I failed the final I would repeat the class. And I hated that class and I didn’t want to retake it again.” Here, she identifies allegiance to a parallel ethical value: Graduating from high school. In this case, while cheating might be wrong, it is an acceptable means to a higher-level goal.

Encouraging an Ethical School Community

Several of the older students with whom we spoke were able to offer us ideas about how schools might create more ethical communities. Sam (Texas) wrote, “A school where cheating isn't necessary would be centered around individualization and learning. Students would learn information and be tested on the information. From there the teachers would assess students' progress with this information, new material would be created to help individual students with what they don't understand. This way of teaching wouldn't be based on time crunching every lesson, but more about helping a student understand a concept.”

Sam provides a vision for the type of school climate in which collaboration, not cheating, would be most encouraged. Kaith (Texas), added to this vision, writing, “In my own opinion students wouldn’t find the need to cheat if they knew that they had the right undivided attention towards them from their teachers and actually showed them that they care about their learning. So a school where cheating wasn’t necessary would be amazing for both teachers and students because teachers would be actually getting new things into our brains and us as students would be not only attentive of our teachers but also in fact learning.”

Both of these visions echo a big idea from “ Ethical Collaboration ”: The importance of reducing the pressure to achieve. Across students’ comments, we heard about how self-imposed pressure, peer pressure, and pressure from adults can encourage cheating.

Where Student Opinions Diverge from Research

The ways in which students spoke about support differed from the descriptions in “ Ethical Collaboration .” The researchers explain that, to reduce cheating, students need “vertical support,” or standards, guidelines, and models of ethical behavior. This implies that students need support understanding what is ethical. However, our youth informants describe a type of vertical support that centers on listening and responding to students’ needs. They want teachers to enable ethical behavior through holistic support of individual learning styles and goals. Similarly, researchers describe “horizontal support” as creating “a school environment where students know, and can persuade their peers, that no one benefits from cheating,” again implying that students need help understanding the ethics of cheating. Our youth informants led us to believe instead that the type of horizontal support needed may be one where collective success is seen as more important than individual competition.

Why Youth Voices Matter, and How to Help Them Be Heard

Our purpose in reaching out to youth respondents was to better understand whether the research perspectives on cheating offered in “ Ethical Collaboration ” mirrored the lived experiences of young people. This blog post is only a small step in that direction; young peoples’ perspectives vary widely across geographic, demographic, developmental, and contextual dimensions, and we do not mean to imply that these youth informants speak for all youth. However, our brief conversations suggest that asking youth about their lived experiences can benefit the way that educators understand school structures.

Too often, though, students are cut out of conversations about school policies and culture. They rarely even have access to information on current educational research, partially because they are not the intended audience of such work. To expand opportunities for student voice, we need to create spaces — either online or in schools — where students can research a current topic that interests them. Then they can collect information, craft arguments they want to make, and deliver their messages. Educators can create the spaces for this youth-driven work in schools, communities, and even policy settings — helping to support young people as both knowledge creators and knowledge consumers.

Additional Resources

- Read “ Student Voice in Educational Research and Reform ” [PDF] by Alison Cook-Sather.

- Read “ The Significance of Students ” [PDF] by Dana L. Mitra.

- Read “ Beyond School Spirit ” by Emily J. Ozer and Dana Wright.

Related Articles

Fighting for Change: Estefania Rodriguez, L&T'16

Notes from ferguson, part of the conversation: rachel hanebutt, mbe'16.

The Real Roots of Student Cheating

Let's address the mixed messages we are sending to young people..

Updated September 28, 2023 | Reviewed by Ray Parker

- Why Education Is Important

- Find a Child Therapist

- Cheating is rampant, yet young people consistently affirm honesty and the belief that cheating is wrong.

- This discrepancy arises, in part, from the tension students perceive between honesty and the terms of success.

- In an integrated environment, achievement and the real world are not seen as at odds with honesty.

The release of ChatGPT has high school and college teachers wringing their hands. A Columbia University undergraduate rubbed it in our face last May with an opinion piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education titled I’m a Student. You Have No Idea How Much We’re Using ChatGPT.

He goes on to detail how students use the program to “do the lion’s share of the thinking,” while passing off the work as their own. Catching the deception , he insists, is impossible.

As if students needed more ways to cheat. Every survey of students, whether high school or college, has found that cheating is “rampant,” “epidemic,” “commonplace, and practically expected,” to use a few of the terms with which researchers have described the scope of academic dishonesty.

In a 2010 study by the Josephson Institute, for example, 59 percent of the 43,000 high school students admitted to cheating on a test in the past year. According to a 2012 white paper, Cheat or Be Cheated? prepared by Challenge Success, 80 percent admitted to copying another student’s homework. The other studies summarized in the paper found self-reports of past-year cheating by high school students in the 70 percent to 80 percent range and higher.

At colleges, the situation is only marginally better. Studies consistently put the level of self-reported cheating among undergraduates between 50 percent and 70 percent depending in part on what behaviors are included. 1

The sad fact is that cheating is widespread.

Commitment to Honesty

Yet, when asked, most young people affirm the moral value of honesty and the belief that cheating is wrong. For example, in a survey of more than 3,000 teens conducted by my colleagues at the University of Virginia, the great majority (83 percent) indicated that to become “honest—someone who doesn’t lie or cheat,” was very important, if not essential to them.

On a long list of traits and qualities, they ranked honesty just below “hard-working” and “reliable and dependent,” and far ahead of traits like being “ambitious,” “a leader ,” and “popular.” When asked directly about cheating, only 6 percent thought it was rarely or never wrong.

Other studies find similar commitments, as do experimental studies by psychologists. In experiments, researchers manipulate the salience of moral beliefs concerning cheating by, for example, inserting moral reminders into the test situation to gauge their effect. Although students often regard some forms of cheating, such as doing homework together when they are expected to do it alone, as trivial, the studies find that young people view cheating in general, along with specific forms of dishonesty, such as copying off another person’s test, as wrong.

They find that young people strongly care to think of themselves as honest and temper their cheating behavior accordingly. 2

The Discrepancy Between Belief and Behavior

Bottom line: Kids whose ideal is to be honest and who know cheating is wrong also routinely cheat in school.

What accounts for this discrepancy? In the psychological and educational literature, researchers typically focus on personal and situational factors that work to override students’ commitment to do the right thing.

These factors include the force of different motives to cheat, such as the desire to avoid failure, and the self-serving rationalizations that students use to excuse their behavior, like minimizing responsibility—“everyone is doing it”—or dismissing their actions because “no one is hurt.”

While these explanations have obvious merit—we all know the gap between our ideals and our actions—I want to suggest another possibility: Perhaps the inconsistency also reflects the mixed messages to which young people (all of us, in fact) are constantly subjected.

Mixed Messages

Consider the story that young people hear about success. What student hasn’t been told doing well includes such things as getting good grades, going to a good college, living up to their potential, aiming high, and letting go of “limiting beliefs” that stand in their way? Schools, not to mention parents, media, and employers, all, in various ways, communicate these expectations and portray them as integral to the good in life.

They tell young people that these are the standards they should meet, the yardsticks by which they should measure themselves.

In my interviews and discussions with young people, it is clear they have absorbed these powerful messages and feel held to answer, to themselves and others, for how they are measuring up. Falling short, as they understand and feel it, is highly distressful.

At the same time, they are regularly exposed to the idea that success involves a trade-off with honesty and that cheating behavior, though regrettable, is “real life.” These words are from a student on a survey administered at an elite high school. “People,” he continued, “who are rich and successful lie and cheat every day.”

In this thinking, he is far from alone. In a 2012 Josephson Institute survey of 23,000 high school students, 57 percent agreed that “in the real world, successful people do what they have to do to win, even if others consider it cheating.” 3

Putting these together, another high school student told a researcher: “Grades are everything. You have to realize it’s the only possible way to get into a good college and you resort to any means necessary.”

In a 2021 survey of college students by College Pulse, the single biggest reason given for cheating, endorsed by 72 percent of the respondents, was “pressure to do well.”

What we see here are two goods—educational success and honesty—pitted against each other. When the two collide, the call to be successful is likely to be the far more immediate and tangible imperative.

A young person’s very future appears to hang in the balance. And, when asked in surveys , youths often perceive both their parents’ and teachers’ priorities to be more focused on getting “good grades in my classes,” than on character qualities, such as being a “caring community member.”

In noting the mixed messages, my point is not to offer another excuse for bad behavior. But some of the messages just don’t mix, placing young people in a difficult bind. Answering the expectations placed on them can be at odds with being an honest person. In the trade-off, cheating takes on a certain logic.

The proposed remedies to academic dishonesty typically focus on parents and schools. One commonly recommended strategy is to do more to promote student integrity. That seems obvious. Yet, as we saw, students already believe in honesty and the wrongness of (most) cheating. It’s not clear how more teaching on that point would make much of a difference.

Integrity, though, has another meaning, in addition to the personal qualities of being honest and of strong moral principles. Integrity is also the “quality or state of being whole or undivided.” In this second sense, we can speak of social life itself as having integrity.

It is “whole or undivided” when the different contexts of everyday life are integrated in such a way that norms, values, and expectations are fairly consistent and tend to reinforce each other—and when messages about what it means to be a good, accomplished person are not mixed but harmonious.

While social integrity rooted in ethical principles does not guarantee personal integrity, it is not hard to see how that foundation would make a major difference. Rather than confronting students with trade-offs that incentivize “any means necessary,” they would receive positive, consistent reinforcement to speak and act truthfully.

Talk of personal integrity is all for the good. But as pervasive cheating suggests, more is needed. We must also work to shape an integrated environment in which achievement and the “real world” are not set in opposition to honesty.

1. Liora Pedhazur Schmelkin, et al. “A Multidimensional Scaling of College Students’ Perceptions of Academic Dishonesty.” The Journal of Higher Education 79 (2008): 587–607.

2. See, for example, the studies in Christian B. Miller, Character and Moral Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014, Ch. 3.

3. Josephson Institute. The 2012 Report Card on the Ethics of American Youth (Installment 1: Honesty and Integrity). Josephson Institute of Ethics, 2012.

Joseph E. Davis is Research Professor of Sociology and Director of the Picturing the Human Colloquy of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Trending Post : 12 Powerful Discussion Strategies to Engage Students

Why Students Cheat on Homework and How to Prevent It

One of the most frustrating aspects of teaching in today’s world is the cheating epidemic. There’s nothing more irritating than getting halfway through grading a large stack of papers only to realize some students cheated on the assignment. There’s really not much point in teachers grading work that has a high likelihood of having been copied or otherwise unethically completed. So. What is a teacher to do? We need to be able to assess students. Why do students cheat on homework, and how can we address it?

Like most new teachers, I learned the hard way over the course of many years of teaching that it is possible to reduce cheating on homework, if not completely prevent it. Here are six suggestions to keep your students honest and to keep yourself sane.

ASSIGN LESS HOMEWORK

One of the reasons students cheat on homework is because they are overwhelmed. I remember vividly what it felt like to be a high school student in honors classes with multiple extracurricular activities on my plate. Other teens have after school jobs to help support their families, and some don’t have a home environment that is conducive to studying.

While cheating is never excusable under any circumstances, it does help to walk a mile in our students’ shoes. If they are consistently making the decision to cheat, it might be time to reduce the amount of homework we are assigning.

I used to give homework every night – especially to my advanced students. I wanted to push them. Instead, I stressed them out. They wanted so badly to be in the Top 10 at graduation that they would do whatever they needed to do in order to complete their assignments on time – even if that meant cheating.

When assigning homework, consider the at-home support, maturity, and outside-of-school commitments involved. Think about the kind of school and home balance you would want for your own children. Go with that.

PROVIDE CLASS TIME

Allowing students time in class to get started on their assignments seems to curb cheating to some extent. When students have class time, they are able to knock out part of the assignment, which leaves less to fret over later. Additionally, it gives them an opportunity to ask questions.

When students are confused while completing assignments at home, they often seek “help” from a friend instead of going in early the next morning to request guidance from the teacher. Often, completing a portion of a homework assignment in class gives students the confidence that they can do it successfully on their own. Plus, it provides the social aspect of learning that many students crave. Instead of fighting cheating outside of class , we can allow students to work in pairs or small groups in class to learn from each other.

Plus, to prevent students from wanting to cheat on homework, we can extend the time we allow them to complete it. Maybe students would work better if they have multiple nights to choose among options on a choice board. Home schedules can be busy, so building in some flexibility to the timeline can help reduce pressure to finish work in a hurry.

GIVE MEANINGFUL WORK

If you find students cheat on homework, they probably lack the vision for how the work is beneficial. It’s important to consider the meaningfulness and valuable of the assignment from students’ perspectives. They need to see how it is relevant to them.

In my class, I’ve learned to assign work that cannot be copied. I’ve never had luck assigning worksheets as homework because even though worksheets have value, it’s generally not obvious to teenagers. It’s nearly impossible to catch cheating on worksheets that have “right or wrong” answers. That’s not to say I don’t use worksheets. I do! But. I use them as in-class station, competition, and practice activities, not homework.

So what are examples of more effective and meaningful types of homework to assign?

- Ask students to complete a reading assignment and respond in writing .

- Have students watch a video clip and answer an oral entrance question.

- Require that students contribute to an online discussion post.

- Assign them a reflection on the day’s lesson in the form of a short project, like a one-pager or a mind map.

As you can see, these options require unique, valuable responses, thereby reducing the opportunity for students to cheat on them. The more open-ended an assignment is, the more invested students need to be to complete it well.

DIFFERENTIATE

Part of giving meaningful work involves accounting for readiness levels. Whenever we can tier assignments or build in choice, the better. A huge cause of cheating is when work is either too easy (and students are bored) or too hard (and they are frustrated). Getting to know our students as learners can help us to provide meaningful differentiation options. Plus, we can ask them!

This is what you need to be able to demonstrate the ability to do. How would you like to show me you can do it?

REDUCE THE POINT VALUE

If you’re sincerely concerned about students cheating on assignments, consider reducing the point value. Reflect on your grading system.

Are homework grades carrying so much weight that students feel the need to cheat in order to maintain an A? In a standards-based system, will the assignment be a key determining factor in whether or not students are proficient with a skill?

Each teacher has to do what works for him or her. In my classroom, homework is worth the least amount out of any category. If I assign something for which I plan on giving completion credit, the point value is even less than it typically would be. Projects, essays, and formal assessments count for much more.

CREATE AN ETHICAL CULTURE

To some extent, this part is out of educators’ hands. Much of the ethical and moral training a student receives comes from home. Still, we can do our best to create a classroom culture in which we continually talk about integrity, responsibility, honor, and the benefits of working hard. What are some specific ways can we do this?

Building Community and Honestly

- Talk to students about what it means to cheat on homework. Explain to them that there are different kinds. Many students are unaware, for instance, that the “divide and conquer (you do the first half, I’ll do the second half, and then we will trade answers)” is cheating.

- As a class, develop expectations and consequences for students who decide to take short cuts.

- Decorate your room with motivational quotes that relate to honesty and doing the right thing.

- Discuss how making a poor decision doesn’t make you a bad person. It is an opportunity to grow.

- Share with students that you care about them and their futures. The assignments you give them are intended to prepare them for success.

- Offer them many different ways to seek help from you if and when they are confused.

- Provide revision opportunities for homework assignments.

- Explain that you partner with their parents and that guardians will be notified if cheating occurs.

- Explore hypothetical situations. What if you have a late night? Let’s pretend you don’t get home until after orchestra and Lego practices. You have three hours of homework to do. You know you can call your friend, Bob, who always has his homework done. How do you handle this situation?

EDUCATE ABOUT PLAGIARISM

Many students don’t realize that plagiarism applies to more than just essays. At the beginning of the school year, teachers have an energized group of students, fresh off of summer break. I’ve always found it’s easiest to motivate my students at this time. I capitalize on this opportunity by beginning with a plagiarism mini unit .

While much of the information we discuss is about writing, I always make sure my students know that homework can be plagiarized. Speeches can be plagiarized. Videos can be plagiarized. Anything can be plagiarized, and the repercussions for stealing someone else’s ideas (even in the form of a simple worksheet) are never worth the time saved by doing so.

In an ideal world, no one would cheat. However, teaching and learning in the 21st century is much different than it was fifty years ago. Cheating? It’s increased. Maybe because of the digital age… the differences in morals and values of our culture… people are busier. Maybe because students don’t see how the school work they are completing relates to their lives.

No matter what the root cause, teachers need to be proactive. We need to know why students feel compelled to cheat on homework and what we can do to help them make learning for beneficial. Personally, I don’t advocate for completely eliminating homework with older students. To me, it has the potential to teach students many lessons both related to school and life. Still, the “right” answer to this issue will be different for each teacher, depending on her community, students, and culture.

STRATEGIES FOR ADDRESSING CHALLENGING BEHAVIORS IN SECONDARY

You may also enjoy....

You are so right about communicating the purpose of the assignment and giving students time in class to do homework. I also use an article of the week on plagiarism. I give students points for the learning – not the doing. It makes all the difference. I tell my students why they need to learn how to do “—” for high school or college or even in life experiences. Since, they get an A or F for the effort, my students are more motivated to give it a try. No effort and they sit in my class to work with me on the assignment. Showing me the effort to learn it — asking me questions about the assignment, getting help from a peer or me, helping a peer are all ways to get full credit for the homework- even if it’s not complete. I also choose one thing from each assignment for the test which is a motivator for learning the material – not just “doing it.” Also, no one is permitted to earn a D or F on a test. Any student earning an F or D on a test is then required to do a project over the weekend or at lunch or after school with me. All of this reinforces the idea – learning is what is the goal. Giving students options to show their learning is also important. Cheating is greatly reduced when the goal is to learn and not simply earn the grade.

Thanks for sharing your unique approaches, Sandra! Learning is definitely the goal, and getting students to own their learning is key.

Comments are closed.

Get the latest in your inbox!

- UB Directory

Common Reasons Students Cheat

Poor Time Management

The most common reason students cite for committing academic dishonesty is that they ran out of time. The good news is that this is almost always avoidable. Good time management skills are a must for success in college (as well as in life). Visit the Undergraduate Academic Advisement website for tips on how to manage your time in college.

Stress/Overload

Another common reason students engage in dishonest behavior has to do with overload: too many homework assignments, work issues, relationship problems, COVID-19. Before you resort to behaving in an academically dishonest way, we encourage you to reach out to your professor, your TA, your academic advisor or even UB’s counseling services .

Wanting to Help Friends

While this sounds like a good reason to do something, it in no way helps a person to be assisted in academic dishonesty. Your friends are responsible for learning what is expected of them and providing evidence of that learning to their instructor. Your unauthorized assistance falls under the “ aiding in academic dishonesty ” violation and makes both you and your friend guilty.

Fear of Failure

Students report that they resort to academic dishonesty when they feel that they won’t be able to successfully perform the task (e.g., write the computer code, compose the paper, do well on the test). Fear of failure prompts students to get unauthorized help, but the repercussions of cheating far outweigh the repercussions of failing. First, when you are caught cheating, you may fail anyway. Second, you tarnish your reputation as a trustworthy student. And third, you are establishing habits that will hurt you in the long run. When your employer or graduate program expects you to have certain knowledge based on your coursework and you don’t have that knowledge, you diminish the value of a UB education for you and your fellow alumni.

"Everyone Does it" Phenomenon

Sometimes it can feel like everyone around us is dishonest or taking shortcuts. We hear about integrity scandals on the news and in our social media feeds. Plus, sometimes we witness students cheating and seeming to get away with it. This feeling that “everyone does it” is often reported by students as a reason that they decided to be academically dishonest. The important thing to remember is that you have one reputation and you need to protect it. Once identified as someone who lacks integrity, you are no longer given the benefit of the doubt in any situation. Additionally, research shows that once you cheat, it’s easier to do it the next time and the next, paving the path for you to become genuinely dishonest in your academic pursuits.

Temptation Due to Unmonitored Environments or Weak Assignment Design

When students take assessments without anyone monitoring them, they may be tempted to access unauthorized resources because they feel like no one will know. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, students have been tempted to peek at online answer sites, Google a test question, or even converse with friends during a test. Because our environments may have changed does not mean that our expectations have. If you wouldn’t cheat in a classroom, don’t be tempted to cheat at home. Your personal integrity is also at stake.

Different Understanding of Academic Integrity Policies

Standards and norms for academically acceptable behavior can vary. No matter where you’re from, whether the West Coast or the far East, the standards for academic integrity at UB must be followed to further the goals of a premier research institution. Become familiar with our policies that govern academically honest behavior.

Insights into How & Why Students Cheat at High Performing Schools

“ A LOT of people cheat and I feel like it would ruin my character and personal standards if I also took part in cheating, but everyone tells me there’s no way I can finish the school year with straight As without cheating. It really makes me upset but I’m honestly contemplating it because colleges can’t see who does and doesn’t cheat. ” – High school student

“Academic dishonesty is any deceitful or unfair act intended to produce a more desirable outcome on an exam, paper, homework assignment, or other assessment of learning.” (Miller, Murdock & Grotwiel, 2017).

Cheating has been a hot topic in the news lately with the unfolding of the college admissions scandal involving affluent parents allegedly using bribery and forgery to help their kids get into selective colleges. Unfortunately, we also see that cheating is common among students in middle schools through graduate schools (Miller, Murdock & Grotwiel, 2017), including the high-performing middle and high schools that Challenge Success has surveyed. To better understand who is cheating in these high schools, how they are cheating, and what is driving this behavior, we looked at recent data from the Challenge Success Student Survey completed in Fall 2018—including 16,054 students from 15 high-performing U.S. high schools (73% public, 27% private). We asked students to self-report their engagement in 12 cheating behaviors during the past month. On each of the items, adapted from a scale developed by McCabe (1999), students could select one of four options: never; once; two to three times; four or more times. We found that 79% of students cheated in some way in the past month.

How Students Cheat & Who Does It

There are two types of cheating that the students we surveyed engage in: (1) cheating collectively and (2) cheating independently. Overall rates of cheating collectively were higher than rates of cheating individually. Examples of cheating collectively include, working on an assignment with others when the instructor asked for individual work, helping someone else cheat on an assessment, and copying from another student during an assessment with that person’s knowledge. Examples of independent cheating include using unpermitted cheat sheets during an assessment, copying from another student during an assessment without their knowledge, or copying material word for word without citing it and turning it in as your own work.

When we looked more closely at who is cheating according to our survey data, we found that 9 th graders were less likely than 10 th , 11 th , and 12 th graders to cheat individually and collectively. This is consistent with other research in the field that shows that cheating tends to increase with grade level (Murdock, Stephens, & Grotewiel, 2016). We also found that male students were more likely to cheat individually than female students. Broader research from the field about cheating by gender has yielded mixed results. Some find that rates for boys are higher than for girls, while others find no difference (McCabe, Treviño & Butterfield, 2001; Murdock, Hale & Weber, 2001; Anderman & Midgley, 2004).

Why Students Cheat

“I think what causes us stress during the school year is the amount of cheating going on around school…Some of my friends and classmates who have siblings or friends that took the classes before in a way have a copy of what the tests will look like. It makes them have a competitive advantage over other people who have no siblings or known friends that took the class before. To have people who have access to these past tests, it creates more stress on students because we have to study more and push ourselves harder.” – High School Student

Why are students cheating at such high rates? Previous research on cheating suggests students may be inclined to cheat and rationalize their behaviors because of various factors including:

- Performance over Mastery: Students may cheat because of the risk of low grades due to worry, pressure on academic performance, or a fixed mindset ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017). School environments perceived by students to be focused on performance goals like grades and test scores over mastery have been associated with behaviors such as cheating (Anderman & Midgley, 2004).

- Peer Relationships/Social Comparison: The increase of social comparisons and competition that many children and adolescents experience in high performing schools or classrooms or the desire to help a friend ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017) may be another factor of choosing to cheat. Students in high-achieving cultures, furthermore, tend to cheat more when they see or perceive their peers cheating (Galloway, 2012).

- Overloaded : Another factor in students cheating is the pressure in high-performing schools to “do it all” which can be influenced by heavy workloads and/or multiple tests on the same day ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017)

- “Cheat or be cheated” rationale: Students may rationalize cheating by blaming the teachers or situation. This often occurs when students see the teacher as uncaring or focused on performance over mastery ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017). Students may rationalize and normalize cheating as the way to succeed in a challenging environment where achievement is paramount (Galloway, 2012).

- Pressure: Students may also cheat because they feel pressure to maintain their status in a success focused community where they see the situation as “cheat or be cheated” ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017).

We see many of these factors reflected in our survey data. Students listed their major sources of stress as grades, tests, finals, or assessments (80% of students) and overall workload and homework (71% of students). We also found that 59% of students feel they have “too much homework,” 75% of students feel “often” or “always” stressed by their schoolwork , 31% of students feel that “many” or “all” of their classes assign homework that helps them learn the material, and 74% worry “quite a bit” or “a lot” about taking assessments while 70% worry the same amount about school assignments.

Reflecting high pressure from within their community, only 51% of students feel they can meet their parents expectations “often” or “always,” 52% of students worry at least a little that if they do not do well in school their friends will not accept them, and 80% of students feel “quite a bit” or “a lot” of pressure to do well in school. Meanwhile, only 33% of students feel “quite” or “very” confident in their ability to cope with stress . Open-ended responses reported by students on our survey reinforce the quantitative data:

“It is hard to do well in classes and become well rounded for applying to college without something giving way… in some cases students cheat. ”

“ I don’t think anyone is having a great time here, when all they’re focusing on is cheating and getting the grade that they want in order to ‘succeed’ in life after high school by going to a great college or university.”

“ Teachers often give very challenging tests that require very large curves to present even reasonable grades and this creates a very stressful atmosphere. Students are often caught cheating because that is often times the only route to getting a decent grade. ”

Quotes like these suggest that there may be a relationship between heavy amounts of homework on top of busy extracurriculars and students feeling that cheating is the only way to get everything done.

What Can Schools Do About It

Schools may find the prevalence of the cheating culture overwhelming—potentially daunted by counteracting the normalization and prevalence of achievement at-all-costs and cheating behaviors. Students themselves, in our survey and in previous research, call for a learning environment where cheating is not an expectation or everyday behavior for getting ahead, and students are held responsible for their behavior (McCabe, 2001).

“ The administration needs to punish students who cheat. The school does not crack down on these kids, and it makes it harder for others to succeed. ”

“ Since I was in 9th grade it feels like our counselors only really care about our class rank and GPA. I am a hard worker but I don’t have the best GPA. Our school focuses too much on grades. This creates pressure on students to cheat just to get a good grade to boost their GPA. Learning has been compromised by a desire for a number that we have been told defines us as people. ”

Schools can work with students to change the prevailing culture of cheating through listening to students about their experiences and perceptions, acknowledging the issue and predominant culture, and collaborating with students to clarify and redefine how and why students learn. Some areas we (and other researchers) recommend that schools can address underlying causes of cheating include:

- Strive for school-wide buy-in for honest academic practices including defining what constitutes cheating and academic dishonesty for students and providing clear consequences for cheating (Galloway, 2012). Further providing open dialogue and discussions with students, parents, and teachers may help students feel that teachers are treating then with respect and fairness (Murdock et al., 2004).

- Educate students on what cheating means in their school community so that cheating is viewed as unacceptable ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017)

- Establish a climate of care and a classroom where it is evident that the teacher cares about student progress, learning, and understanding.

- Emphasize mastery and learning over performance . One strategy is through using formative assessments such as practice exams that can be reviewed in class and homework that can be corrected until students achieve mastery on the concepts ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017).

- Revise assessments and grading policies to allow for redemption and revision.

- Ensure that students are met with “reasonable demands” such as spacing assignments and assessments across days and reduce workload without reducing rigor ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017)

- Teach students time management strategies (e.g. using a planner, breaking tasks into manageable pieces, and how to use resources or ask for help). Schools may even teach parents how to help students organize and manage their work rather than providing them with answers. ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017)

Overall, schools should aim to change student attitudes around integrity through “clear, fair, and consistent” assessments, valuing learning over mastery, reducing comparisons and competition between students, teaching students management and organization skills, and demonstrating care and empathy for students and the pressures that face ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017) .

Anderman, E.M. & Midgley, C. (2004). Changes in self-reported academic cheating across the transition from middle school to high school. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 29(4), 499-517.

Galloway, M. K. (2012). Cheating in advantaged high schools: Prevalence, justifications, and possibilities for change. Ethics & Behavior, 22(5), 378-399.

McCabe, D. (1999). Academic dishonesty among high school students. Adolescence, 34 (136), 681- 687.

McCabe, D. (2001) Cheating: Why students do it and how we can help them stop. American Educator , Winter, 38-43.

McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in academic institutions: A decade of research. Ethics & Behavior , 11, 219-232.

Miller, A. D., Murdock, T. B., & Grotewiel, M. M. (2017). Addressing Academic Dishonesty Among the Highest Achievers. Theory Into Practice , 56 (2), 121-128.

Murdock, T., Hale, N., & Weber, M. (2001). Predictors of cheating among early adolescents: Academic and social motivations. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 26, 96-115.

Murdock, T. B., Miller, A., & Kohlhardt, J. (2004). Effects of Classroom Context Variables on High School Students’ Judgments of the Acceptability and Likelihood of Cheating. Journal of Educational Psychology , 96 (4), 765-777.

Murdock, T., Stephens, J., & Grotewiel, M. (2016). Student dishonesty in the face of assessment. In G. Brown and L. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment (pp. 186-203). London, England: Routledge.

Wangaard, D. B. & J. M. Stephens (2011). Academic integrity: A critical challenge for schools. Excellence & Ethics , Winter 2011.

Interested in learning more about your students’ perceptions of their school experiences? Learn more about the Challenge Success Student Survey here .

- Instructors

- Institutions

- Teaching Strategies

- Higher Ed Trends

- Academic Leadership

- Affordability

- Product Updates

Why Do Students Cheat? One Student’s Perspective

Sarah Gido is a Marketing and Communications major at Anglo-American University in Prague, Czech Republic

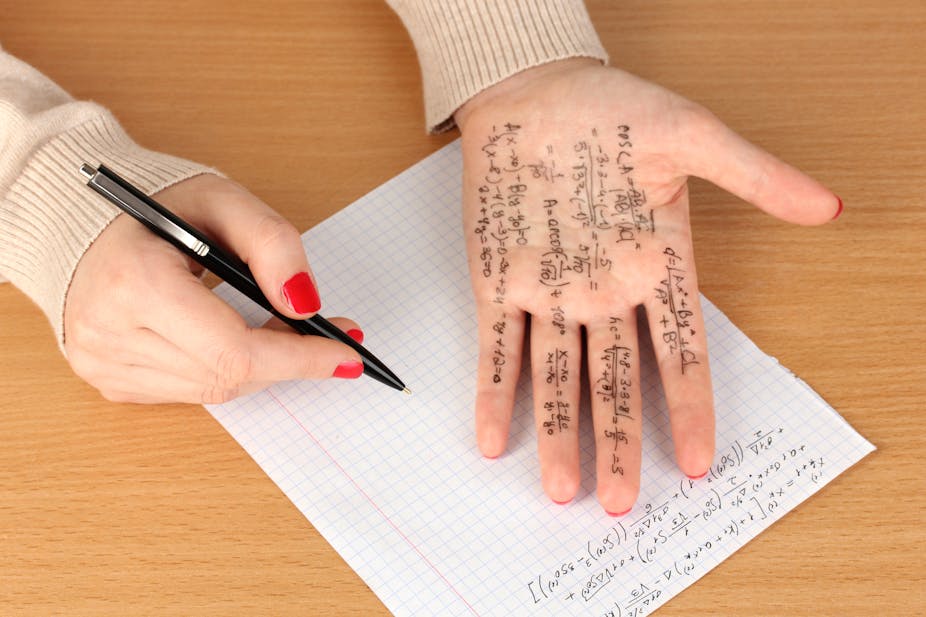

Cheating has always been an issue in school. When I asked my friends if they had ever cheated in school, the response was almost always yes. Some said that in high school they wrote answers on water bottle wrappers or even on their legs to be seen through the holes of their jeans. Another said they took an online public speaking course and had their script written above their computer. But if we all know it’s morally wrong, why do students cheat? And why are more students cheating now in 2023 than ever before?

Online learning makes cheating easier

The shift to online learning in 2020 drastically changed the relationship between students and learning. From a student perspective, it is much easier to cheat on virtual tests and homework assignments. With any answer at their fingertips on the internet, students turn to search engines for help on exams. Digital learning puts a barrier between students and professors, but also between students and learning content.

It’s difficult to feel connected and interested in information through independent learning that arises from digital assignments. When students don’t have an emotional stake in the learning process, they retain less of what they learn and cheating is an easy solution. From splitting screens between tabs and studying websites, technology has made student cheating easier—and harder for instructors to detect—than ever before. When it’s that easy, students often find that it doesn’t feel as wrong. Furthermore, it’s easier on the conscience to cheat without a professor or your peers looking at you.

Students are losing motivation

Students’ plates are fuller than ever before. The switch back to fully in-person learning was jarring but a welcome change for many! However, many students fell into a cycle of choosing convenience over studying during virtual and hybrid learning courses. Being back in the classroom meant the return of intense schedules, public speaking, and rising stress levels. Staying motivated in class is much more difficult when balancing the stress of a job, relationships, sickness, or hunting for an internship. According to a survey completed by the American Addiction Centers, 88 percent of students reported their school life to be stressful. Dwindling levels of motivation can lead to procrastination and resistance to do assignments that weigh on students’ minds. Homework, essays, and exams turn into dreaded obligations completed with haste by cheating rather than opportunities for enhancement.

Students are focused on passing courses

In the minds of many students, there’s more emphasis on passing classes than there is on learning. In the stress of coursework, focus on exam scores can be overwhelming. Finishing a degree is difficult and there has been a distinct shift in the perception of college courses and the end goal. The COVID-19 pandemic put an abrupt halt to the “normal” progression of school life, and many students now are just looking to finish.

Curb your students’ desire to cheat

The students of today are unique and are looking to regain motivation. Making content relatable is the best way to tap into the minds of students and have them invest time and energy into the course. This is as simple as using relevant real-world resources and references. I look forward to courses that challenge me in a fun way as a learner and individual. As a Marketing student, my favorite college course I have taken utilized nontraditional assignments, including oral exams and examining current advertisements. Fostering a classroom that welcomes opportunities for career and personal development may energize your students and make them less likely to cheat.

Want to learn more about how and why students cheat, plus strategies for preventing and detecting cheating? Download our free eBook, “Cheating and Academic Dishonesty: How to Spot it — and What to Do About It.”

Related articles.

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

What is the real reason students turn to cheating?

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

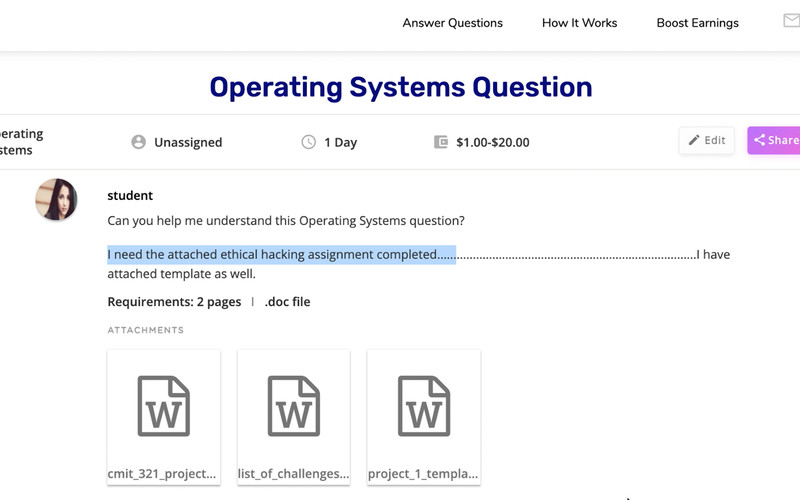

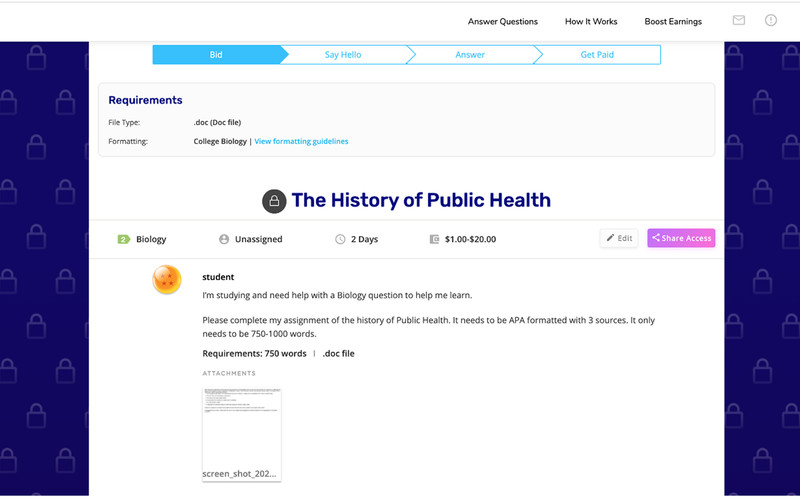

Issues of student cheating have been increasing over the years as more and more ‘help with homework’ sites have been accessible to students across the UK. A 2018 study by Swansea University found that as many as one in seven graduates had used contract cheating services to complete assignments . The switch to remote learning brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated these issues, and in 2020 the number of students outsourcing their coursework rose rapidly with usage figures for one of the most popular ‘help with homework’ websites increasing by 196%. In early 2021 there were contract cheating websites operating in the UK.

In October 2021 The Department for Education announced that it would introduce an amendment to the Skills and Post-16 Education Bill, that would make it a criminal offence to provide, arrange or advertise contract cheating services or ‘essay mills’. Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and some US states have taken similar steps. However, a recent study from the journal Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education revealed that students will still engage with third party homework services even when they believe they are breaking the law. These findings bring into question how effective legislation will be against contract cheating, and what can be done to prevent students seeking out alternative opportunities to outsource their work.

Why do students turn to contract cheating services? Students’ skills in academic writing, such as reports, essays and other written formal documents are becoming an increasing source of anxiety for them. In a Pearson HE learner survey from June 2020, 77% said they had struggled with their first assignments , partly owing to a lack of confidence in their academic skills as they step up to a university standard of working.

Therefore, instead of viewing students who outsource their coursework as cheats who are undermining the value of academic performance, should we instead question why they are lacking confidence and turn to cheating in the first place – and what role do institutions play in this?

Download Pearson’s latest report to take an in-depth look at the issue of academic writing, understand why students turn to ‘contract cheating’, and see how universities can take action to nurture their writing abilities with legitimate support and feedback, so they learn, gain confidence, and improve their own work.

How can you re-engage students with reading?

Providing teaching support for large cohorts, how can you solve the maths problem in non-specialist subjects.

Why do students cheat? Listen to this dean’s words

Associate Dean, Director Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution, University of Florida

Disclosure statement

Chris Loschiavo is affiliated with the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management and the Association for Student Conduct Administration.

University of Florida provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Editor’s note: Since the publication of this article, the University of Florida terminated Chris Loschiavo’s employment when it learned he used his UF work computer account to purchase pornography.

Cheating in college has been with us since the inception of higher education. In recent months, cases of cheating, including large-scale cheating at elite colleges , have led to considerable turmoil.

Many of these behaviors could well start to take shape right at the level of high school. A survey conducted by renowned academic integrity researcher Don McCabe shows how widespread the problem is in high schools.

Large-scale cheating

In a survey of 24,000 students at 70 high schools, McCabe found “64% of students admitted to cheating on a test, 58% admitted to plagiarism and 95% said they participated in some form of cheating, whether it was on a test, plagiarism or copying homework.”

Statistics for cheating for college students are much the same. Surveys indicate as high as 70% of students report some kind of cheating in college. These survey results, which have remained consistent over time, represent a variety of behaviors.

So, what could possibly lead to such behaviors?

As Director of Student Conduct, I have been responsible for addressing these behaviors for the last 16 years. I have also served as president of the Association for Student Conduct Administration (ASCA) , an organization of over 3,300 professionals doing student conduct work at over 1,800 institutions across the US and Canada. All these positions have given me unique insights into the issue of cheating beyond my institution. And I can say these results are not at all surprising to me.

Students cheat for a variety of reasons:

It can be an intentional, calculated decision in order to get ahead. Often, it is motivated by the path to success that they see around them – people cheating without incurring any real consequences.

From politicians cheating, to corporate scandals such as Enron , to the steroid scandal in Major League Baseball , to the NFL’s “deflategate,” our students are surrounded by examples of dishonest acts.

What’s worse, society seemingly rewards these individuals for their dishonest behaviors. Students then come to believe that dishonest behavior is rewarded and often do not hesitate to engage in it.

My experience shows students engage in a cost/benefit analysis that goes like this: “If I cheat and don’t get caught, the reward is an ‘A’ in the class, admission to a graduate/professional school of my choice or a great job. If I get caught, it isn’t as bad as what Enron did, so the consequence won’t be so bad.”

The example we set as a society is what I have found to be the most significant reason for students cheating.

This also gets combined with a pressure to succeed. These students have grown up in a culture where even the team that scores the least gets a trophy. So they are not prepared for failure.

When they believe they are going to fail (which nowadays is often anything less than an “A”), students will do whatever it takes to avoid it, because they don’t want to let others (often family) down.

High schools are not teaching research

Another reason for student cheating is being unprepared for college level work. Over my many years addressing the issue of plagiarism, I have seen student after student who has written a research paper and not given proper attribution. This is not because they were taking credit for someone else’s words, but simply because they were never taught how to write a research paper.

I have had many conversations over the years with students who truly don’t understand how to write a research paper. So much of high school these days is teaching to the large number of standardized tests. As a result, learning how to research is being lost.

Also, students aren’t being taught how to paraphrase. So, they just cut and paste from the articles they read on the internet – it is easy, quick and takes very little effort to do this.

Some others don’t have any confidence in their own thoughts. So when given the chance to write a paper in which they must share their own ideas, they simply go to the internet and cut and paste someone else’s words or ideas, thinking they are worth more than their own.

I once had a student who cut and pasted large parts of her paper from the internet. When she was asked why she did it, she stated that the author had said what she wanted to say much more eloquently. She said she was afraid of changing it using her own words, as it could be an incorrect interpretation.

This student lacked confidence in her ability to interpret what she read and then translate it in her own words. Another student once shared that he didn’t know as much as the author he took his information from. He concluded, “Why would the professor want to hear the student’s own thoughts?”

This has been a potential downfall of teaching to the test, as many of our secondary educators are being forced to do – students aren’t able to think and problem-solve for themselves.

And when they are forced to do so, they simply take someone else’s ideas.

Cheating could be a cry for help

Some others cheat because they have poor time management skills. College work is challenging, and some students underestimate how long it will take them. When they run out of time, they panic and take a shortcut.

Sometimes these students also have inappropriately prioritized social or extracurricular events over their academic work.

Finally, some students cheat because it is a cry for help. I will never forget a student I met with many years ago for a cheating case.

He admitted responsibility and accepted the consequence of a failing grade in his class. I felt convinced that he truly learned from this incident. However, within the week, he was accused of engaging in the very same behavior in the same class again.

This was very early in my career, and I was ready to remove him from our institution. However, as I found out more, I learned that his girlfriend had just broken up with him, his grandmother (to whom he was very close) had recently passed away and his mother had been recently diagnosed with terminal cancer (I did actually have proof of every one of these events).

The combination made it impossible for this student to focus on his academics. While these incidents certainly didn’t excuse his behavior, they helped explain why he made such bad choices.

He was afraid to ask for help. It was only when there appeared to be no other option, did he open up about what he was dealing with. I was able to hold him accountable appropriately while also making sure he had access to the resources that would help him address his current emotional state.

He went on to graduate from the institution once he was able to get his life back together. Had his faculty not bothered to address the behavior, he would have likely dropped out.

I have never forgotten the lesson this student taught me.

What can administrators, faculty do to help?

I learned to ask more questions. Now, I try to dig a little deeper when trying to find out why a student made a certain choice. Additionally, it has shaped how I present to faculty on the importance of reporting cheating.

So often I hear from faculty either that they don’t want to be the reason a student gets into trouble, or that they shouldn’t have to deal with these issues.

When I tell the story of this student, it reframes for faculty the importance of reporting. It really isn’t about getting the student in trouble; rather, it is about making sure someone with training can interact with the student to help and set the student up for success when dealing with life’s challenges.

When faculty see it as potentially helping the student, they become much more willing to report.

Cheating is a challenge for our society, both at the high school and college levels. We need to remember, however, that it is rarely a thought-out, premeditated act. More often, it is an impulsive act.

To have a real impact, we need to address the underlying issues.

Tomorrow: Students cheat for good grades. Why not make the classroom about learning and not testing?

- Deflategate

- Extracurricular activities

- College students

- Corporate scandals

Events Officer

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

- Faculty Experts

Motivation is a key factor in whether students cheat

The Conversation

Carlton J. Fong, Assistant Professor of Education at Texas State University & Megan Krou, Research Analyst, Teachers College, Columbia University | March 4, 2021

Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic caused many U.S. colleges to shift to remote learning in the spring of 2020, student cheating has been a concern for instructors and students alike.

To detect student cheating, considerable resources have been devoted to using technology to monitor students online . This online surveillance has increased students’ anxiety and distress . For instance, some students have indicated the monitoring technology required them to stay at their desks or risk being labeled as cheaters.

Although relying on electronic eyes may partially curb cheating, there’s another factor in the reasons students cheat that often gets overlooked – student motivation.

As a team of researchers in educational psychology and higher education , we became interested in how students’ motivation to learn, or what drives them to want to succeed in class, affects how much they cheated in their schoolwork.

To shine light on why students cheat, we conducted an analysis of 79 research studies and published our findings in the journal Educational Psychology Review. We determined that a variety of motivational factors, ranging from a desire for good grades to a student’s academic confidence, come into play when explaining why students cheat. With these factors in mind, we see a number of things that both students and instructors can do to harness the power of motivation as a way to combat cheating, whether in virtual or in-person classrooms. Here are five takeaways:

1. Avoid emphasizing grades

Although obtaining straight A’s is quite appealing, the more students are focused solely on earning high grades, the more likely they are to cheat. When the grade itself becomes the goal, cheating can serve as a way to achieve this goal.

Students’ desire to learn can diminish when instructors overly emphasize high test scores, beating the curve, and student rankings. Graded assessments have a role to play, but so does acquisition of skills and actually learning the content, not only doing what it takes to get good grades.

2. Focus on expertise and mastery

Striving to increase one’s knowledge and improve skills in a course was associated with less cheating. This suggests that the more students are motivated to gain expertise, the less likely they are to cheat. Instructors can teach with a focus on mastery, such as providing additional opportunities for students to redo assignments or exams. This reinforces the goal of personal growth and improvement.

3. Combat boredom with relevance

Compared with students motivated by either gaining rewards or expertise, there might be a group of students who are simply not motivated at all, or experiencing what researchers call amotivation. Nothing in their environment or within themselves motivates them to learn. For these students, cheating is quite common and seen as a viable pathway to complete coursework successfully rather than putting forth their own effort. However, when students find relevance in what they’re learning, they are less likely to cheat.

When students see connections between their coursework and other courses, fields of study or their future careers, it can stimulate them to see how valuable the subject might be. Instructors can be intentional in providing rationales for why learning a particular topic might be useful and connecting students’ interest to the course content.

4. Encourage ownership of learning

When students struggle, they sometimes blame circumstances beyond their control, such as believing their instructor to have unrealistic standards. Our findings show that when students believe they are responsible for their own learning, they are less likely to cheat.

Encouraging students to take ownership over their learning and put in the required effort can decrease academic dishonesty. Also, providing meaningful choices can help students feel they are in charge of their own learning journey, rather than being told what to do.

5. Build confidence

Our study found that when students believed they could succeed in their coursework, cheating decreased. When students do not believe they will be successful, a teaching approach called scaffolding is key. Essentially, the scaffolding approach involves assigning tasks that match the students’ ability level and gradually increase in difficulty. This progression slowly builds students’ confidence to take on new challenges. And when students feel confident to learn, they are willing to put in more effort in school.

An inexpensive solution

With these tips in mind, we expect cheating might pose less of a threat during the pandemic and beyond. Focusing on student motivation is a much less controversial and inexpensive solution to curtail any tendencies students may have to cheat their way through school.

Are these motivational strategies the cure-all to cheating? Not necessarily. But they are worth considering – along with other strategies – to fight against academic dishonesty.

About The Conversation

The Conversation ( https://theconversation.com/us ) is an independent, nonprofit publisher of commentary and analysis, authored by academics and edited by journalists for the general public. The Conversation publishes short articles (800-1000 words) by academics on timely topics related to their research.

Share this article

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Submit to Reddit

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share using Email

February 1, 2022 10:03 am

Why do students cheat?

Academic integrity matters — but it isn’t easy to guarantee. Here are 3 reasons why students plagiarize and how you can address it.

I’ll admit, in a moment of desperation, I typed into the search bar, “why do students cheat?” After extensive discussions about academic integrity, I couldn’t comprehend why my students would do such a thing. The internet would have an answer, I was sure of it (it seems my students also shared in this sentiment).

While it didn’t give me the solace I was looking for, it did take me on a tour of the history of academic dishonesty.

My first search result from 2018 offers us a solution: “Why Students Cheat – and What to Do About It.”

As I scrolled further, I noticed that in 1981, a teacher bemoaned, “Research papers advertised for sale. Cadets dismissed in cheating scandals. Students hiding formulas in calculator cases” in an article called “Why Do Some Students Cheat?”

And all the way back to 1941, an article titled “Why Students Cheat” appeared in the Journal of Higher Education.

This timeline tells us a few things:

- Students have been cheating for at least 80 years, but probably longer.

- And teachers have been bothered by it since then.

- While we are quick to blame technology these days, it’s probably not the answer to the question.

So, what are the time-tested reasons why students cheat?

Many students are under pressure from parents or guardians to earn certain grades. Maybe the expectation is acceptance to a certain university, following a certain career path, or just a general expectation of “success.” As much as teenagers like to pretend they don’t care what their parents think, this can be a heavy burden to bear.

Whether or not familial pressure exists, some students also place expectations on themselves to perform at a high level. While we hope all our students are intrinsically motivated, perfectionism and fixation on an idealized outcome can be unhealthy, especially because students may feel they need to achieve their desired GPA by any means necessary.

While this may not be our first thought, students do feel pressure from peers as well. When a Harvard Graduate School of Education student asked why cheating happens, a student wrote, “‘Peer pressure makes students cheat. Sometimes they have a reason to cheat like feeling [like] they need to be the smartest kid in class.’”

While educators cannot remove familial pressure, we can focus on intrinsic motivation by increasing student agency and creating a collaborative environment. That way, we’re relieving pressure instead of adding to it.