Definition of Jargon

Jargon is a literary term that is defined as the use of specific phrases and words in a particular situation, profession, or trade. These specialized terms are used to convey hidden meanings accepted and understood in that field. Jargon examples are found in literary and non-literary pieces of writing.

The use of jargon becomes essential in prose or verse or some technical pieces of writing, when the writer intends to convey something only to the readers who are aware of these terms. Therefore, jargon was taken in early times as a trade language, or as a language of a specific profession, as it is somewhat unintelligible for other people who do not belong to that particular profession. In fact, specific terms were developed to meet the needs of the group of people working within the same field or occupation.

Jargon and Slang

Jargon is sometimes wrongly confused with slang , and people often take it in the same sense but a difference is always there.

Slang is a type of informal category of language developed within a certain community , and consists of words or phrases whose literal meanings are different than the actual meanings. Hence, it is not understood by people outside of that community or circle. Slang is more common in spoken language than written.

Jargon , on the other hand, is broadly associated with a subject , occupation, or business that makes use of standard words or phrases, and frequently comprised of abbreviations, such as LOC (loss of consciousness), or TRO (temporary restraining order). However, unlike slang, its terms are developed and composed deliberately for the convenience of a specific profession, or section of society. We can see the difference in the two sentences given below.

- Did you hook up with him? ( Slang )

- Getting on a soapbox ( Jargon )

Examples of Jargon in Literature

Example #1: hamlet (by william shakespeare).

Historical Legal Jargon

Hamlet to HORATIO: “Why, may not that be the skull of a lawyer ? Where be his quiddities now , his quillities, his cases, his tenures , and his tricks? Why does he suffer this mad knave now to knock him about the sconce with a dirty shovel, and will not tell him of his action of battery ? Hum! This fellow might be in’s time a great buyer of land, with his statutes , his recognizances , his fines, his double vouchers, his recoveries : is this the fine of his fines, and the recovery of his recoveries, to have his fine pate full of fine dirt? Will his vouchers vouch him no more of his purchases and double ones too, than the length and breadth of a pair of indentures? The very conveyances of his lands will scarcely lie in this box; and must the inheritor himself have no more, ha?”

Here, you can see the use of words specifically related to the field of law, marked in bold. These are legal words used at the time of Shakespeare.

Example #2: Patient Education: Nonallergic Rhinitis (By Robert H Fletcher and Phillip L Lieberman)

Medical Jargon

“Certain medications can cause or worsen nasal symptoms (especially congestion ). These include the following: birth control pills, some drugs for high blood pressure (e.g., alpha blockers and beta blockers), antidepressants , medications for erectile dysfunction , and some medications for prostatic enlargement. If rhinitis symptoms are bothersome and one of these medications is used, ask the prescriber if the medication could be aggravating the condition.”

This passage is full of medical jargon, such as those shown in bold. Perhaps only those in the medical community would fully understand all of these terms.

Example #3: Marek v Lane (By U.S. Supreme Court Ruling)

Modern Legal Jargon

“In August 2008, 19 individuals brought a putative class action lawsuit in the U. S. District Court for the Northern District of California against Facebook and the companies that had participated in Beacon, alleging violations of various federal and state privacy laws . The putative class comprised only those individuals whose personal information had been obtained and disclosed by Beacon during the approximately one-month period in which the program’s default setting was opt out rather than opt in. The complaint sought damages and various forms of equitable relief , including an injunction barring the defendants from continuing the program.”

This ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court is full of modern legal jargon. The terms shown in bold are a good example of jargon that is not likely to be understood by the typical person.

Function of Jargon

The use of jargon is significant in prose and verse. It seems unintelligible to the people who do not know the meanings of the specialized terms. Jargon in literature is used to emphasize a situation, or to refer to something exotic. In fact, the use of jargon in literature shows the dexterity of the writer, of having knowledge of other spheres. Writers use jargon to make a certain character seem real in fiction , as well as in plays and poetry.

Post navigation

Definition and Examples of Jargon

Pablo Blasberg/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Jargon refers to the specialized language of a professional or occupational group. While this language is often useful or necessary for those within the group, it is usually meaningless to outsiders. Some professions have so much jargon of their own that it has its own name; for example, lawyers use legalese , while academics use academese . Jargon is also sometimes known as lingo or argot . A passage of text that is full of jargon is said to be jargony .

Key Takeaways: Jargon

• Jargon is the complex language used by experts in a certain discipline or field. This language often helps experts communicate with clarity and precision.

• Jargon is different from slang, which is the casual language used by a particular group of people.

• Critics of jargon believe such language does more to obscure than clarify; they argue that most jargon can be replaced with simple, direct language without sacrificing meaning.

Supporters of jargon believe such language is necessary for navigating the intricacies of certain professions. In scientific fields, for instance, researchers explore difficult subjects that most laypeople would not be able to understand. The language the researchers use must be precise because they are dealing with complex concepts (molecular biology, for example, or nuclear physics) and simplifying the language might cause confusion or create room for error. In "Taboo Language," Keith Allan and Kate Burridge argue that this is the case:

"Should jargon be censored? Many people think it should. However, close examination of jargon shows that, although some of it is vacuous pretentiousness...its proper use is both necessary and unobjectionable."

Critics of jargon, however, say such language is needlessly complicated and in some cases even deliberately designed to exclude outsiders. American poet David Lehman has described jargon as "the verbal sleight of hand that makes the old hat seem newly fashionable." He says the language "gives an air of novelty and specious profundity to ideas that, if stated directly, would seem superficial, stale, frivolous, or false." In his famous essay "Politics and the English Language," George Orwell argues that obscure and complex language is often used to "make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind."

Jargon vs. Slang

Jargon should not be confused with slang , which is informal, colloquial language sometimes used by a group (or groups) of people. The main difference is one of register; jargon is formal language unique to a specific discipline or field, while slang is common, informal language that is more likely to be spoken than written. A lawyer discussing an " amicus curiae brief" is an example of jargon. A teen talking about "making dough" is an example of slang.

List of Jargon Words

Jargon can be found in a variety of fields, from law to education to engineering. Some examples of jargon include:

- Due diligence: A business term, "due diligence" refers to the research that should be done before making an important business decision.

- AWOL: Short for "absent without leave," AWOL is military jargon used to describe a person whose whereabouts are unknown.

- Hard copy: A common term in business, academia, and other fields, a "hard copy" is a physical printout of a document (as opposed to an electronic copy).

- Cache: In computing, "cache" refers to a place for short-term memory storage.

- Dek: A journalism term for a subheading, usually one or two sentences long, that provides a brief summary of the article that follows.

- Stat: This is a term, usually used in a medical context, that means "immediately." (As in, "Call the doctor, stat!")

- Phospholipid bilayer: This is a complex term for a layer of fat molecules surrounding a cell. A simpler term is "cell membrane."

- Detritivore: A detritivore is an organism that feeds on detritus or dead matter. Examples of detritivores include earthworms, sea cucumbers, and millipedes.

- Holistic: Another word for "comprehensive" or "complete," "holistic" is often used by educational professionals in reference to curriculum that focuses on social and emotional learning in addition to traditional lessons.

- Magic bullet: This is a term for a simple solution that solves a complex problem. (It is usually used derisively, as in "I don't think this plan you've come up with is a magic bullet.")

- Best practice: In business, a "best practice" is one that should be adopted because it has proven effectiveness.

- Definition and Examples of Language Varieties

- Slang, Jargon, Idiom, and Proverb Explained for English Learners

- Business Jargon

- Definition and Examples of Plain English

- What Is Academese?

- What Is Semantic Field Analysis?

- Metalanguage in Linguistics

- The Difference Between a Speech and Discourse Community

- Argot Definition and Examples

- What is Legalese?

- Slang in the English Language

- What Is Register in Linguistics?

- George Carlin's "Soft Language"

- Definition and Examples of Anti-Language

- What's a Buzzword?

- Definition of Usage Labels and Notes in English Dictionaries

You are using an outdated browser. It's time... Upgrade your browser to improve your experience. And your life.

Log In | View Cart

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Log in | View Cart

This advice-column-style blog for SLPs was authored by Pam Marshalla from 2006 to 2015, the archives of which can be explored here. Use the extensive keywords list found in the right-hand column (on mobile: at the bottom of the page) to browse specific topics, or use the search feature to locate specific words or phrases throughout the entire blog.

Jargon and Intelligibility

By Pam Marshalla

Q: I am working with a 7-year-old in first grade. He has received services since 3-years of age privately and at school. He is making very slow progress in speech, and is having great difficulty comprehending and completing first grade work. His speech is characterized mostly by jargon with a few intelligible words, so some meaning may be derived. He is able to produce two-syllable words but falls apart with more complexity. He occasionally produces three-word intelligible utterances such as “What is it?” or “Where ya goin’?” EVERYONE is asking, “Is he ever going to be intelligible?” Help!

When you add cognitive delay into the mix, you cannot know for certain how far you can take this child in terms of speech and language. But consider this: A seven-year-old who is still using 2-3 word combinations SHOULD be jargoning . That is his expressive speech level. Children jargon a lot between 18-months and 2.5-years of age.

Therefore, I would consider his jargon a GOOD sign. It means that he is trying to push his expressive speech beyond the 2-to-3-word level. He is trying to speak longer utterances. But he does not have the cognitive/linguistic/phonological/oral motor abilities to do so. So it comes out as jargon. In fact, your client is using “jargon embedded with real words” which I consider to be advanced jargon.

Don’t worry about the jargon. Just let it happen.

Instead focus on KEEPING him rehearsing intelligible 2-3 word combinations that are over-articulated and exaggerated. Hold him back. Have him speak a little louder and with exaggerated intonation and stress patterns. Have him punch out the individual syllables. You want him to speak clean, clear, crisp pre-sentences. It is these little pre-sentences that get strung together to make longer utterances.

For example, right now he might say, “Mommy is a girl,” and he might also say, “Daddy is a boy.” In a few months, he will combine these with a conjunction and say, “Mommy is a girl and daddy is a boy.” His utterance will be longer. Its intelligibility will depend upon how well he says each part.

Another example, right now he will say, “That one red”, and he will say, “I like it”. In a few months, he will embed them and say, “I like that red one.” Again he needs to be rehearsing the shorter utterances with the best clarity he can muster so that when they become embedded they will be as intelligible as possible.

Interact with him in ways that reinforce his best productions of the short 2-3 word pre-sentences. Model them for him. Have dialogues in which you both speak back-and-forth in 2-3 word combinations. You want him to speak these shorted utterances the best way he can so that as he learns to stack them together, he will retain the clarity.

1 thought on “Jargon and Intelligibility”

I have the same situation with my 4 yr old, he is turning 5 yrs in two months. He talks very fasts and jargons a lot. He is with a speech therapist twice a week. I am very worried Do these kids get to speak clear as the rest of the kids? Is this consider a language disorder? And worried that it could be something else

Leave a comment! Cancel reply

Keep the conversation going! Your email address will not be published.

Speech Therapy Jargon: Speech & Language Terms

Image source: speechdudes.wordpress.com

When you’re new to the world of speech therapy, learning the new terminology can be overwhelming. Always ask your child’s speech-language pathologist (SLP) to rephrase something if you have trouble with it. You can also stop by your local library and pick up some books on speech therapy. Many speech therapy books offer a simple breakdown of the basics. Here’s a quick reference guide to help you get started sorting out the terms. You can also review our previous post on speech therapy acronyms.

Articulation

This is often used as a general term to describe the pronunciation of sounds. A child with an articulation disorder might skip certain sounds, substitute them, or distort them. Articulation also refers to sounds that are produced with the lips, tongue, and teeth, or “articulators.”

A speech or language delay means that a child is progressing at a slower rate than other children in his age group.

A speech or language disorder means that a child is developing speech and language abnormally. It refers to atypical language usage.

Speech with an irregular flow. Certain sounds may be improperly elongated, airflow may be interrupted, and sounds, words, or phrases may be improperly repeated.

A repetition of words that occurs without meaning and in imitation. For example, a child might repeat a slogan from a commercial in a situation in which the slogan makes no sense. The imitation may occur immediately after the stimulus or later.

Fluency refers to speech that flows smoothly and is clearly understood. Fluent speech is without irregularities like abnormal repetitions.

The causes of functional speech disorders are usually unknown. That is, they occur without a physical disability. A child or adult with a functional speech disorder has trouble making one or more specific sounds.

Language refers to a set of rules for the expression of meaningful communication. Includes speech, writing, signing, and gestures.

Language Sample

A language sample is a collection of a child’s communication that a speech therapist will use to assess a speech disorder or delay.

Image source: anongallery.org

A morpheme is a meaningful part of language that cannot be broken down further. For example, “tree.” A bound morpheme is part of a larger word. For example, the “ing” on “hiking.”

A speech disorder with a known, physical cause. For example, a stroke or brain injury may cause a speech disorder.

The smallest possible sound. For example, the phonemes “m” and “n.”

The relationship between spoken sounds and written letters. For example, “phone” sounds like “fone.”

Phonological Awareness

The awareness of sounds (both written and verbal), how they go together, and how they may be changed to create new meanings and words.

Image source: cartoonstock.com

The meaning of words and language. For example, “I’m so hungry, I could eat an elephant,” is not meant to be interpreted literally. A child with a problem with semantics might not understand abstract language or idioms.

The verbal method of communication.

The rules that govern how words and phrases fit together to create coherent sentences. In other words, grammar.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.2: Standards for Language in Public Speaking

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 17790

- Kris Barton & Barbara G. Tucker

- Florida State University & University of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

Clear language is powerful language. Clarity is the first concern of a public speaker when it comes to choosing how to phrase the ideas of his or her speech. If you are not clear, specific, precise, detailed, and sensory with your language, you won’t have to worry about being emotional or persuasive, because you won’t be understood. There are many aspects of clarity in language, listed below.

Achieving Clarity

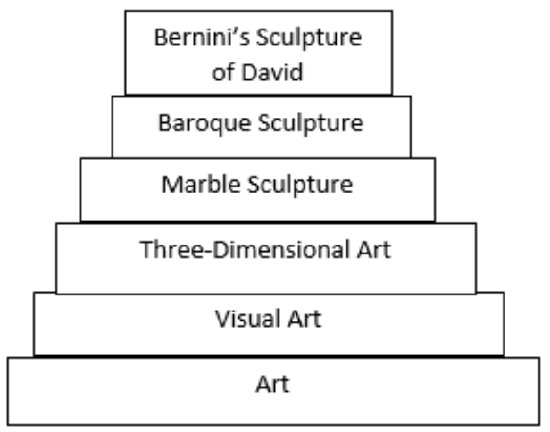

The first aspect of clarity is concreteness. We usually think of concreteness as the opposite of abstraction. Language that evokes many different visual images in the minds of your audience is abstract language. Unfortunately, when abstract language is used, the images evoked might not be the ones you really want to evoke. A word such as “art” is very abstract; it brings up a range of mental pictures or associations: dance, theatre, painting, drama, a child’s drawing on a refrigerator, sculpture, music, etc. When asked to identify what an abstract term like “art” means, twenty people will have twenty different ideas.

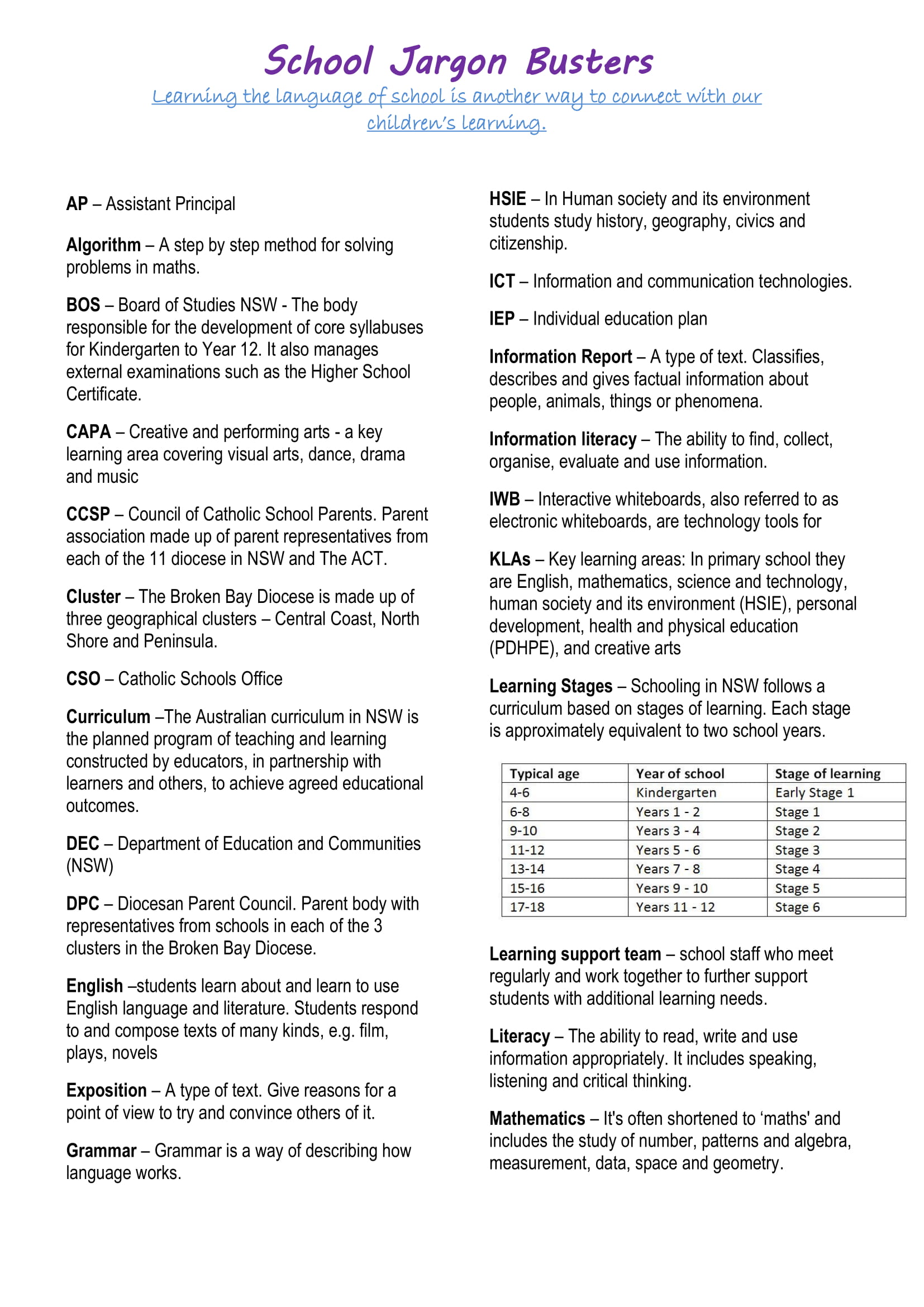

In order to show how language should be more specific, the “ladder of abstraction” (Hayakawa, 1939) was developed. The ladder of abstraction in Figure 10.1 helps us see how our language can range from abstract (general and sometimes vague) to very precise and specific (such as an actual person that everyone in your audience will know). You probably understood the ladder in Figure 10.2 until it came to the word “Baroque.” At Bernini’s, you might get confused if you do not know much about art history. If the top level said “Bernini’s David,” a specific sculpture, that would be confusing to some because while almost everyone is familiar with Michelangelo’s David, Bernini’s version is very different. It’s life-sized, moving, and clothed. Bernini’s is as much a symbol of the Baroque Age as Michelangelo’s is of the Renaissance. But unless you’ve taken an art history course, the reference, though very specific, is meaningless to you, and even worse, it might strike you as showing off. In fact, to make my point, here they are in Figure 10.2. A picture is worth a thousand words, right?

Related to the issue of specific vs. abstract is the use of the right word. Mark Twain said, “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.” For example, the words “prosecute” and “persecute” are commonly confused, but not interchangeable. Two others are peremptory/pre-emptive and prerequisites/perquisites. Can you think of other such word pair confusion?

In the attempt to be clear, which is your first concern, you will also want to be simple and familiar in your language. Familiarity is a factor of attention (Chapter 7); familiar language draws in the audience. Simple does not mean simplistic, but the avoidance of multi-syllable words. If a speaker said, “A collection of pre-adolescents fabricated an obese personification comprised of compressed mounds of minute aquatic crystals,” you might recognize it as “Some children made a snowman,” but maybe not. The language is not simple or familiar and therefore does not communicate well, although the words are correct and do mean the same thing, technically.

Along with language needing to be specific and correct, language can use appropriate similes and metaphors to become clearer. Literal language does not use comparisons like similes and metaphors; figurative language uses comparisons with objects, animals, activities, roles, or historical or literary figures. Literal says, “The truck is fast.” Figurative says “The truck is as fast as…“ or “The truck runs like…” or “He drives that truck like Kyle Busch at Daytona.” Similes use some form of “like” or “as” in the comparisons. Metaphors are direct comparisons, such as “He is Kyle Busch at Daytona when he gets behind the wheel of that truck.” Here are some more examples of metaphors:

Love is a battlefield.

Upon hearing the charges, the accused clammed up and refused to speak without a lawyer.

Every year a new crop of activists is born.

For rhetorical purposes, metaphors are considered stronger, but both can help you achieve clearer language, if chosen wisely. To think about how metaphor is stronger than simile, think of the difference “Love is a battlefield” and “Love is like a battlefield.” Speakers are encouraged to pick their metaphors and not overuse them. Also, avoid mixed metaphors, as in this example: “That’s awfully thin gruel for the right wing to hang their hats on.” Or “He found himself up a river and had to change horses.” The mixed metaphor here is the use of “up a river” and “change horses” together; you would either need to use an all river-based metaphor (dealing with boats, water, tides, etc.) or a metaphor dealing specifically with horses. The example above about a “new crop” “being born,” is actually a mixed metaphor, since crops aren’t born, but planted and harvested. Additionally, in choosing metaphors and similes, speakers want to avoid clichés, discussed next.

Clichés are expressions, usually similes, that are predictable. You know what comes next because they are overused and sometimes out of date. Clichés do not have to be linguistic—we often see clichés in movies, such as teen horror films where you know exactly what will happen next! It is not hard to think of clichés: “Scared out of my . . .” or “When life gives you lemons. . .” or “All is fair in. . .” or, when describing a reckless driver, “She drives like a . . . “ If you filled in the blanks with “wits,” “make lemonade,” “love and war,” “or “maniac,” those are clichés.

Clichés are not just a problem because they are overused and boring; they also sometimes do not communicate what you need, especially to audiences whose second language is English. “I will give you a ballpark figure” is not as clear as “I will give you an estimate,” and assumes the person is familiar with American sports. Therefore, they also will make you appear less credible in the eyes of the audience because you are not analyzing them and taking their knowledge, background, and needs into account. As the United States becomes more diverse, being aware of your audience members whose first language is not English is a valuable tool for a speaker.

Additionally, some clichés are so outdated that no one knows what they mean. “The puppy was as cute as a button” is an example. You might hear your great-grandmother say this, but who really thinks buttons are cute nowadays? Clichés are also imprecise. Although clichés do have a comfort level to them, comfort puts people to sleep. Find fresh ways, or just use basic, literal language. “The bear was big” is imprecise in terms of giving your audience an idea of how frightful an experience faced by a bear would be. “The bear was as big as a house” is a cliché and an exaggeration, therefore imprecise. A better alternative might be, “The bear was two feet taller than I am when he stood on his back legs.” The opposite of clichés is clear, vivid, and fresh language.

In trying to avoid clichés, use language with imagery , or sensory language. This is language that makes the recipient smell, taste, see, hear, and feel a sensation. Think of the word “ripe.” What is “ripe?” Do ripe fruits feel a certain way? Smell a certain way? Taste a certain way? Ripe is a sensory word. Most words just appeal to one sense, like vision. Think of color. How can you make the word “blue” more sensory? How can you make the word “loud” more sensory? How would you describe the current state of your bedroom or dorm room to leave a sensory impression? How would you describe your favorite meal to leave a sensory impression? or a thunderstorm?

Poetry uses much imagery, so to end this section on fresh, clear language, here is a verse from “Daffodils” by William Wordsworth. Notice the metaphors (“daffodils dancing,” “host,” which brings to mind great heavenly numbers), simile (“as the stars”) and the imagery (“golden” rather than “yellow,” and other appeals to feeling and sight):

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the Milky Way.

Effectiveness

Language achieves effectiveness by communicating the right message to the audience. Clarity contributes to effectiveness, but there are some other aspects of effectiveness. To that end, language should be a means of inclusion and identification, rather than exclusion. Let’s establish this truth: Language is for communication; communication is symbolic, and language is the main (but not only) symbol system we use for communication. If language is for communication, then its goal should be to bring people together and to create understanding.

Unfortunately, we habitually use language for exclusion rather than inclusion. We can push people away with our word choices rather than bringing them together. We discussed the concepts of stereotyping and totalizing in Chapter 2, and they serve as examples of what we’re talking about here. What follows are some examples of language that can exclude members of your audience from understanding what you are saying.

Jargon (which we discussed in Chapter 2) used in your profession or hobby should only be used with audiences who share your profession or hobby. Not only will the audience members who don’t share your profession or hobby miss your meaning, but they will feel that you are not making an honest effort to communicate or are setting yourself above them in intelligence or rank. Lawyers are often accused of using “legalese,” but other professions and groups do the same. If audience members do not understand your references, jargon, or vocabulary, it is unlikely that they will sit there and say, “This person is so smart! I wish I could be smart like this speaker.” The audience member is more likely to be thinking, “Why can’t this speaker use words we understand and get off the high horse?” (which I admit, is a cliché!)

What this means for you is that you need to be careful about assumptions of your audience’s knowledge and their ability to interpret jargon. For example, if you are trying to register for a class at the authors’ college and your adviser asks for the CRN, most other people would have no idea what you are talking about (course reference number). Acronyms, such NPO, are common in jargon. Those trained in the medical field know it is based on the Latin for “nothing by mouth.” The military has many acronyms, such as MOS (military occupational specialty, or career field in civilian talk). If you are speaking to an audience who does not know the jargon of your field, using it will only make them annoyed by the lack of clarity.

Sometimes we are not even aware of our jargon and its inadvertent effects. A student once complained to one of the authors about her reaction when she heard that she had been “purged.” The word sounds much worse than the meaning it had in that context: that her name was taken off the official roll due nonpayment before the beginning of the semester.

The whole point of slang is for a subculture or group to have its own code, almost like secret words. Once slang is understood by the larger culture, it is no longer slang and may be classified as “informal” or “colloquial” language. “Bling” was slang; now it’s in the dictionary. Sports have a great deal of slang used by the players and fans that then gets used in everyday language. For example, “That was a slam dunk” is used to describe something easy, not just in basketball.

Complicated vocabulary

coIf a speaker used the word “recalcitrant,” some audience members would know the meaning or figure it out (“Calci-”is like calcium, calcium is hard, etc.), but many would not. It would make much more sense for them to use a word readily understandable–“stubborn.” Especially in oral communication, we should use language that is immediately accessible. However, do not take this to mean “dumb down for your audience.” It means being clear and not showing off. For a speaker to say “I am cognizant of the fact that…” instead of “I know” or “I am aware of…” adds nothing to communication.

Profanity and cursing

It is difficult to think of many examples, other than artistic or comedy venues, where profanity or cursing would be effective or useful with most audiences, so this kind of language is generally discouraged.

Credibility

Another aspect of effectiveness is that your language should enhance your credibility. First, audiences trust speakers who use clear, vivid, respectful, engaging, and honest language. On the other hand, audiences tend not to trust speakers who use language that excludes others or who exhibit uneducated language patterns. All of us make an occasional grammatical or usage error. However, constant verb and pronoun errors and just plain getting words confused will hurt the audience’s belief that you are competent and knowledgeable. In addition, a speaker who uses language and references that are not immediately accessible or that are unfamiliar will have diminished credibility. Finally, you should avoid the phrase “I guess” in a speech. Credible speakers should know what they are talking about.

Rhetorical Techniques

There are several traditional techniques that have been used to engage audiences and make ideas more attention-getting and memorable. These are called rhetorical techniques. Although “rhetorical” is associated with persuasive speech, these techniques are also effective with other types of speeches. We will not mention all of them here, but some important ones are listed below. Several of them are based on a form of repetition. You can refer to an Internet source for a full list of the dozens of rhetorical devices.

Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds in a sentence or passage. As such, it is a kind of rhyme. Minister Tony Campolo said, “When Jesus told his disciples to pray for the kingdom, this was no pie in the sky by and by when you die kind of prayer.”

Alliteration is the repetition of initial consonant sounds in a sentence or passage. In his “I Have a Dream Speech,” Dr. Martin Luther King said, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Not only does this sentence use alliteration, it also uses the next rhetorical technique on our list, antithesis.

Antithesis is the juxtaposition of contrasting ideas in balanced or parallel words, phrases, or grammatical structures. Usually antithesis goes: Not this, but this. John F. Kennedy’s statement from his 1961 inaugural address is one of the most quoted examples of antithesis: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” In that speech he gave another example, “If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.”

Parallelism is the repetition of sentence structures. It can be useful for stating your main ideas. Which one of these sounds better?

“Give me liberty or I’d rather die.”

“Give me liberty or give me death.”

The second one uses parallelism. Quoting again from JFK’s inaugural address: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” The repetition of the three-word phrases in this sentence (including the word “any” in each) is an example of parallelism.

Anaphora is a succession of sentences beginning with the same word or group of words. In his inaugural address, JFK began several succeeding paragraphs with “To those”: “To those old allies,” “To those new states,” “To those people,” etc.

Hyperbole is intentional exaggeration for effect. Sometimes it is for serious purposes, other times for humor. Commonly we use hyperbolic language in our everyday speech to emphasize our emotions, such as when we say “I’m having the worst day ever” or “I would kill for a cup of coffee right now.” Neither of those statements is (hopefully) true, but it stresses to others the way you are feeling. Ronald Reagan, who was often disparaged for being the oldest president, would joke about his age. In one case he said, “The chamber is celebrating an important milestone this week: your 70th anniversary. I remember the day you started.”

Irony is the expression of one’s meaning by using language that normally signifies the opposite, typically for humorous or emphatic effect. Although most people think they understand irony as sarcasm (such as saying to a friend who trips, “That’s graceful”), it is a much more complicated topic. A speaker may use it when they profess to say one thing but clearly means something else or say something that is obviously untrue and everyone would recognize that and understand the purpose. Irony in oral communication can be difficult to use in a way that affects everyone in the audience the same way.

Using these techniques alone will not make you an effective speaker. Dr. King and President Kennedy combined them with strong metaphors and images as well; for example, Dr. King described the promises of the founding fathers as a “blank check” returned with the note “insufficient funds” as far as the black Americans of his time were concerned. That was a very concrete, human, and familiar metaphor to his listeners and still speaks to us today.

Appropriateness

Appropriateness relates to several categories involving how persons and groups should be referred to and addressed based on inclusiveness and context. The term “politically correct” has been overused to describe the growing sensitivity to how the power of language can marginalize or exclude individuals and groups. While there are silly extremes such as the term “vertically challenged” for “short,” these humorous examples overlook the need to be inclusive about language. Overall, people and groups should be respected and referred to in the way they choose to be. Using inclusive language in your speech will help ensure you aren’t alienating or diminishing any members of your audience.

Gender-Inclusive Language

The first common form of non-inclusive language is language that privileges one of the sexes over the other. There are three common problem areas that speakers run into while speaking: using “he” as generic, using “man” to mean all humans, and gender-typing jobs. Consider the statement, “Every morning when an officer of the law puts on his badge, he risks his life to serve and protect his fellow citizens.” Obviously, both male and female police officers risk their lives when they put on their badges.

A better way to word the sentence would be, “Every morning when officers of the law put on their badges, they risk their lives to serve and protect their fellow citizens.” Notice that in the better sentence, we made the subject plural (“officers”) and used neutral pronouns (“they” and “their”) to avoid the generic “he.” Likewise, speakers of English have traditionally used terms like “man,” and “mankind” when referring to both females and males. Instead of using the word “man,” refer to the “human race.”

The last common area where speakers get into trouble with gender and language has to do with job titles. It is not unusual for people to assume, for example, that doctors are male and nurses are female. As a result, they may say “she is a woman doctor” or “he is a male nurse” when mentioningsomeone’s occupation, perhaps not realizing that the statements “she is a doctor” and “he is a nurse” already inform the listener as to the sex of the person holding that job.

Ethnic Identity

Ethnic identity refers to a group an individual identifies with based on a common culture. For example, within the United States we have numerous ethnic groups, including Italian Americans, Irish Americans, Japanese Americans, Vietnamese Americans, Cuban Americans, and Mexican Americans. As with the earlier example of “male nurse,” avoid statements such as “The committee is made up of four women and a Vietnamese man.” All that should be said is, “The committee is made up of five people.”

If for some reason gender and ethnicity have to be mentioned—and usually it does not—the gender and ethnicity of each member should be mentioned equally. “The committee is made up of three European-American women, one Latina, and one Vietnamese male.” In recent years, there has been a trend toward steering inclusive language away from broad terms like “Asians” and “Hispanics” because these terms are not considered precise labels for the groups they actually represent. If you want to be safe, the best thing you can do is ask a couple of people who belong to an ethnic group how they prefer to be referred to in that context.

The last category of exclusive versus inclusive language that causes problems for some speakers relates to individuals with physical or intellectual disabilities or forms of mental illness. Sometimes it happens that we take a characteristic of someone and make that the totality or all of what that person is. For example, some people are still uncomfortable around persons who use wheelchairs and don’t know how to react. They may totalize and think that the wheelchair defines and therefore limits the user. The person in the wheelchair might be a great guitarist, sculptor, parent, public speaker, or scientist, but those qualities are not seen, only the wheelchair.

Although the terms “visually impaired” and “hearing impaired” are sometimes used for “blind” and “deaf,” this is another situation where the person should be referred to as he or she prefers. “Hearing impaired” denotes a wide range of hearing deficit, as does “visually impaired. “Deaf” and “blind” are not generally considered offensive by these groups.

Another example is how to refer to what used to be called “autism.” Saying someone is “autistic” is similar to the word “retarded” in that neither is appropriate. Preferable terms are “a person with an autism diagnosis” or “a person on the autism spectrum.” In place of “retarded,” “a person with intellectual disabilities” should be used. Likewise, slang words for mental illness should always be avoided, such as “crazy” or “mental.”

Other Types of Appropriateness

Language in a speech should be appropriate to the speaker and the speaker’s background and personality, to the context, to the audience, and to the topic. Let’s say that you’re an engineering student. If you’re giving a presentation in an engineering class, you can use language that other engineering students will know. On the other hand, if you use that engineering vocabulary in a public speaking class, many audience members will not understand you. As another example, if you are speaking about the Great Depression to an audience of young adults or recent immigrants, you can’t assume they will know the meaning of terms like “New Deal” and “WPA,” which would be familiar to an audience of senior citizens. Audience analysis is a key factor in choosing the language to use in a speech.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use Jargon

I. What is Jargon?

Jargon is the specific type of language used by a particular group or profession. Jargon (pronounced jär-gən) can be used to describe correctly used technical language in a positive way. Or, it can describe language which is overly technical, obscure, and pretentious in a negative way.

II. Examples of Jargon

There is a wide variety of jargon, as each specific career or area of study has its own set of vocabulary that is shared between those who work within the profession or field. Here are a few common examples of jargon:

A common dictum in allergy practice is that the patient’s medical history is the primary diagnostic test. Laboratory studies, including skin and in vitro tests for specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies, have relevance only when correlated with the patient’s medical history. Furthermore, treatment should always be directed toward current symptomatology and not merely toward the results of specific allergy tests.

This excerpt from a PubMed research paper is a prime example of medical jargon. In plain English, a dictum is a generally accepted truth, the laboratory is the lab, and symptomatology is simply a patient’s set of symptoms.

I acknowledge receipt of your letter dated the 2nd of April. The purpose of my suggestion that my client purchases an area of land from yourself is that this can be done right up to your clearly defined boundary in which case notwithstanding that the plan is primarily for identification purposes on the ground the position of the boundary would be clearly ascertainable this in our opinion would overcome the existing problem.

This is an example of legal jargon, taken from a clause within a commercial lease schedule. In plain English, it states that a letter was received on April 2, concerning exactly which plot of land a client hopes to purchase.

This man was an involuntarily un-domiciled.

Whereas the previous two examples concerned technical and acceptable jargon, this third phrase is an example of unwanted, unnecessary jargon: jargon in the negative sense. Here, “involuntarily undomiciled” is a jargon-addled term which allows someone to avoid saying the less attractive phrase “homeless.”

III. The Importance of Using Jargon

Jargon has both positive and negative connotations . On one hand, jargon is necessary and very important: various specialized fields such as medicine, technology, and law require the use of jargon to explain complicated ideas and concepts. On the other hand, sometimes jargon is used for doublespeak , or purposely obscure language used to avoid harsh truths or to manipulate those ignorant of its true meaning. An example of doublespeak is “collateral damage,” a phrase used by the military to describe people have who been unintentionally or accidentally wounded or killed, often civilian casualties. The phrase “collateral damage” sounds a lot nicer than the reality of “innocent person killed.”

IV. Examples of Jargon in Literature

Often, literary writers make use of jargon in order to create realistic situations. A well-written fictional doctor will use medical lingo, just as a medical writer will use medical jargon in a creative nonfiction piece about the profession. Below are a few examples of jargon in literature.

The poisonous molecules of benzene arrived in the bone marrow in a crescendo. The foreign chemical surged with the blood and was carried between the narrow spicules of supporting bone into the farthest reaches of the delicate tissue. It was like a frenzied horde of barbarians descending into Rome. And the result was equally as disastrous. The complicated nature of the marrow, designed to make most of the cellular content of the blood, succumbed to the invaders.

This excerpt from Robin Cook’s medical thriller called Fever makes use of medical jargon like “molecules of benzene,” “spicules of bone,” and “cellular content of blood” but writes of such topics in a literary fashion, comparing the spread of benzene to a horde of barbarians invading Rome.

The worst scenario would be for Bruiser to get indicted and arrested and put on trial. That process would take at least a year. He’d still be able to work and operate his office. I think. They can’t disbar him until he’s convicted.

In John Grisham’s legal thriller, legal jargon is used by those working in law. In plain English, “being indicted” is being formally accused of a crime and “being disbarred” is being prevented from practicing law as a failed lawyer.

As these examples show, the use of jargon creates a richer narrative landscape which realistically represents how certain professionals communicate amongst one another within their selected field of work and study.

V. Examples of Jargon in Pop Culture

Just like literature, pop culture uses jargon to accurately represent real life. Here are a few examples of jargon in pop culture:

In “Mission Statement,” Weird Al Yankovic mocks business jargon with jargon-addled lyrics which make fun of business English:

We must all efficiently Operationalize our strategies Invest in world-class technology And leverage our core competencies In order to holistically administrate Exceptional synergy

In Legally Blonde, Elle Woods’ admissions essay to Harvard Law presents the blonde beauty queen attempting to use legal jargon with “I object!” expressing disdain for cat-callers.

I feel comfortable using legal jargon in everyday life: I object!

VI. Related Terms

Just like jargon, slang is a specialized vocabulary used by a certain group. The similarities end there. Unlike jargon, slang is not used by professionals and is, in fact, avoided by them. Slang is particularly informal language typically used in everyday speech rather than writing. Because slang is based on popularity and the present, it is constantly changing and evolving with social trends and groups. Here is an example of slang versus jargon:

Whoa, that’s sick!

The slang phrase “sick” has a much different meaning than an illness when used by skaters. Rather, it means that something is cool or appealing.

The patient is ill.

In this example of medical jargon, a patient is described as ill rather than more common colloquial phrases like “sick” or “feeling under the weather.”

Lingo is often used in place of both slang and jargon. The reason is this: lingo refers to a specific type of language used by a specific group. In other words, lingo encompasses both slang and jargon. “What’s the lingo?” could be used to casually ask what the jargon is or to ask what the slang phrase is in a certain situation.

VII. Conclusion

Jargon is professional language used by a specific group of people. When used to confuse or mislead, jargon is considered a negative thing, but it is acceptable when used within a specific profession or area of study. From the toilet salesman to the gardener to the mathematician, jargon is used in a wide variety of professions.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

The Tangled Language of Jargon

What our emotional reaction to jargon reveals about the evolution of the English language, and how the use of specialized terms can manipulate meaning.

What could the many synonyms in the English language possibly have to do with social disconnection? And what does jargon, a kind of language that nobody likes but can’t stop, won’t stop using, have to do with manipulating meaning?

Perhaps nothing at all… or perhaps they can be stark reminders that words aren’t all created equal. The language choices we make can have profound repercussions for how we engage with the world, and the world with us.

How Language Reflects Life

Recent research tells us that the very technologies designed to connect people , such as social media, often end up disconnecting us from experiencing the simple pleasures of being human in the natural world. Modern life online can be lonely. Language sometimes reflect this.

As life grows increasingly more complex, it requires an ever-evolving, specialized language, another kind of social technology, to explain all the shadowy online things on which we spend our precious time, social interactions that are virtually real, yet somehow not quite real. Language naturally changes, and yet many of the trends of words, catchphrases, sound bytes that are produced and promoted over others can also give us a niggling sense of disconnection, or even of being played, where the emotional impact of meaning itself can also seem virtually real, yet not quite real. Through language, trivial things can be made to seem more important than they are, while more significant things can be overlooked—or deliberately obscured.

Consider the wild debate over how the Oxford Junior Dictionary for children removed infrequently used nature terms like “chestnut,” “lark,” “buttercup,” and “clover,” and replaced them with seemingly more relevant contemporary technical jargon, such as “block-graph,” “analogue,” “chatroom,” and “mp3 player,” thereby prizing an “interior, solitary childhood” over one spent playing outside in the woods and fields.

Does it matter? Why be up in arms about this news at all, as many prominent writers and readers were? In general there’s nothing wrong with new words entering the language. This decision was made based on usage studies from largely children’s texts and corpora , so shouldn’t we all move with the times and trust in an objective science? Or could data be biased?

As the uproar shows, in some vague, indescribable way, we feel something when we see the first group of words that we may not with regards to the second. Is it just cultural, poetic, or linguistic prejudice that makes us like a some words, and not others? Or is there some other story behind why some words seem to alienate us?

The English Language’s Split Personality

It may have something to do with the strange bipolar nature of English, lexically torn between two languages. The English language is at its heart a Germanic language. And yet, after the Norman Conquest, Norman French became the language of the elite ruling class. This caused a huge influx of Latinate words to enter the language at high levels of society, such as government, law, education and business. French was the language of power.

This had a profound effect on the emerging Modern English language. As a result, English has this split personality of two opposing lexicons—one from the Germanic/Anglo-Saxon side of the family tree and the other from the French/Greco-Latinate interloper—existing side by side (and uncomfortably glaring at each other at family reunions).

Because of this, English probably has more synonyms than any other language , with many redundant pairs that mean essentially the same thing, like flood/inundation, snake/serpent, inside/interior, friendly/amiable, bloom/flower, answer/respond, cow/bovine, gift/present to name just a few . But words are not all about meaning. Though they may mean the same things, the ways and the contexts in which they’re used are very different, as well as the assumptions we implicitly make when one is used and not the other.

Germanic origin words tend to be the short words, usually describing simple human needs, nature, life and relationships ( births, deaths, love, sun, moon, earth, water ), while Latinate words are all the big long ones— more polysyllabic, abstract, formal, and fancy . It’s thanks to both linguistic strands, as well as other borrowings, that English has such a richness of vocabulary, with clear jobs for both classes of words.

Together with conventional Latin and Greek scientific usage , Latinate forms by now make up a majority of English vocabulary… and that number might be increasing, thanks to jargon.

Where Jargon Fits In

Originally used in more formal, intellectual and abstract contexts, Latinate words have held onto their prestige and their power. So when we coin new words to describe new things (and old things), especially if we want to sound smart, precise, and scientific, we overwhelmingly reach for a Latinate form, not a Germanic one. Instead of just talking , we now also have dialoguing (even if we wish we didn’t). Some studies have shown that though users of this more formal language might be seen as competent , listeners often view them as distant and unapproachable, while speakers that use more Germanic forms are often seen as flexible and might be more likely to “help you out of a jam.”

This is perhaps because most of the words we absorb as babies and first learn as children are still the little Germanic words, and they also happen to be the ones that are still most commonly used. So we develop this long-lived, deep-rooted familiarity with their meanings and their senses in a way that we don’t with Latinate words, which can often seem detached and disconnected from any emotional reaction to a word’s meaning. While we worry about disastrous “ flood ” warnings, our French friends might have the same kind of emotional panic about imminent “ inundations.” English has borrowed the same word but it certainly doesn’t feel the same. Likewise, snakes might give you the shivers, while serpents don’t threaten you in quite the same way . Short, Germanic origin words can have a significant impact on how we react to information.

For that reason, style guides, plain language advocates, and teachers often follow George Orwell’s dictum to “never use a long word where a short one will do.” Despite advising students to avoid using Latinate forms, a study showed that many instructors often unwittingly violate their own rules , and are swayed by writing that contains more Latinate forms, possibly because of the assumption of this type of language being more educated, precise (e.g. spotty vs occasional mean the same thing but one seems more definitive), and prestigious (a chamber is a lot grander than a room ). So while the familiar, shorter words are viewed positively, we may assume the longer words are more important, intellectual, and possibly convey a lot more meaning than we can really grasp. A nature term like the flower forget-me-not directly borrowed from German Vergissmeinnicht is more easily remembered and absorbed than its mysterious scientific name myosotis (from the Greek for the just as picturesque mouse ear ).

This matters, because Latinate words can seem more distant and a little unreal. Ultimately, their meanings can be more easily manipulated and abused without us understanding instinctively what’s happened—such as when jargon is used in euphemisms or doublespeak (when it’s designed to deliberately mislead) or other circumlocutions. This happens all too frequently in politics, government, bureaucracy, the military, and corporate life—all areas of concentrated social power.

Take these poor, unloved, deliberately evasive and confusing examples of jargon from the U.S. government’s own site on plain language :

It’s easy to see how the shorter, plainer version may pack more of an emotional punch, something a government bureaucrat or military spokesperson might want to avoid.

How Jargon Can Exclude and Obscure

It turns out that, far from being objective, jargon—outwardly a sober, professional kind of talk for experts from different occupational fields—has always carried with it some very human impulses, placing power and prestige over knowledge. A doctor, for example, might inappropriately use jargon in explaining a diagnosis to a patient, which prevents the patient from participating in their own care. This quality of jargon attracts those that might want to obscure biases, beef up simplistic ideas, or even hide social or political embarrassments behind a slick veneer of seemingly objective, “scientific” language without being challenged.

Latinate forms happen to lend themselves well to new terminology like this, especially technical jargon, for those very perceptions of precision and prestige, as well as detachment. But this detachment comes with a price. The alienness and incomprehensibility of new jargon words we’re unfamiliar with might sometimes make us a mite uncomfortable. It can sound inauthentic, compared to other innovative language change, from slang to secret languages. There are all kinds of innovative speech used by certain groups not just to share information easily, or to talk about new ideas, but also to show belonging and identity—and to keep outsiders out.

It’s one of the reasons people hate jargon with a passion and have been railing against it for years, centuries even . H. W. Fowler called it “talk that is considered both ugly-sounding and hard to understand.” L.E. Sissman is a little more subtle. Sissman defines jargon as “all of these debased and isolable forms of the mother tongue that attempt to paper over an unpalatable truth and/or to advance the career of the speaker (or the issue, cause or product he is agent for) by a kind of verbal sleight of hand, a one-upmanship of which the reader or listener is victim.”

Jargon, as useful as it is in the right contexts, can end up being socially problematic and divisive when it hides and manipulates meanings from those who need to receive the information. This negative reception hasn’t stopped jargon that apes scientific language from being widely produced, by economists, academics, entrepreneurs, journalists… and probably even poets. Jargon has now become the devil’s corporate middle management’s language, making information harder to share and receive. It has seeped into almost every facet of a complex modern life, giving us new buzzwords not even a mother could love, with terms like self-actualization, monetize, incentivize, imagineering, onboarding, synergize, and the like. And there’s so much more where that came from.

When Jargon Becomes Dangerous

William D. Lutz talks about how jargon and doublespeak can often be carefully designed to cover up embarrassing or secret information. For example, a commercial airline that had a 727 crash, killing three passengers, was able to pass off the resulting three million dollar insurance profit on its books as “the involuntary conversion of a 727,” which was unlikely to be questioned by confused shareholders whose eyes would probably have glazed over from the cumbersome legal jargon.

Words aren’t equal just because they mean the same thing, especially when the stakes are high. It’s not simply a matter of knowing or not knowing the meaning of these words, or if they accurately describe facts, but what Sally McConnell-Ginet calls the conceptual or cultural baggage , the hidden background assumptions the language carries with them, the ‘ologies and ‘isms that pretend to be something they’re not. Most recently in politics, the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings showed how deftly legal terminology can be wielded to avoid or plausibly deny or confuse clear facts. For example, denying knowledge of stolen documents is literally not a lie if you steadfastly assume they aren’t stolen, despite textual evidence to the contrary. The statement “I am not sure that all legal scholars refer to Roe as the settled law of the land” literally defers to a fact, the meaning of which is true. The conceptual baggage the statement carries with it, however, strongly suggests the writer does not disagree with the opinion.

Linguist Dwight Bolinger suggests that this is exactly the kind of heinous abuse of meaning that makes linguistic activism critical, shining a spotlight on these egregious cases where lies are hidden by omission or avoidance of the truth in jargon, euphemism, doublespeak, and other linguistic trickery.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- Sheet Music: the Original Problematic Pop?

Performing Memory in Refugee Rap

I Hear America Singing

Vulture Cultures

Recent posts.

- Ostrich Bubbles

- Smells, Sounds, and the WNBA

- A Bodhisattva for Japanese Women

- Asking Scholarly Questions with JSTOR Daily

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Jargon Examples: This Will Teach You How to Use Them Correctly

We all come across jargon examples in everyday life. However we rarely pay attention to how much of our speech is peppered with phrases that wouldn't have made sense a few decades back. The very funny English language will never cease to amaze one with how much it evolves, and how phrases that were limited to a particular profession or even a demographic can become examples of jargon over time.

We all come across jargon examples in everyday life. However we rarely pay attention to how much of our speech is peppered with phrases that wouldn’t have made sense a few decades back. The very funny English language will never cease to amaze one with how much it evolves, and how phrases that were limited to a particular profession or even a demographic can become examples of jargon over time.

“Jargon is the verbal sleight of hand that makes the old hat seem newly fashionable; it gives an air of novelty and specious profundity to ideas that, if stated directly, would seem superficial, stale, frivolous, or false.” – David Lehman

Jargon is a term used to describe words that are specific to a particular subject; which are incomprehensible to persons unacquainted with the topic or subject. Jargon is generally related to a specific profession, which is why it sounds like gobbledygook to people outside that occupation. In many cases, jargon comprises word abbreviations.

Most times, it’s often confused with the use of slang, or colloquialisms in everyday language. The following are some examples of jargon and the different ways it’s used.

Jargon and Slang

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines slang , as “an informal nonstandard vocabulary composed typically of coinages, arbitrarily changed words, and extravagant, forced, or facetious figures of speech.” Essentially, slang is synonymous with phrases that are used in such a way that their significance is different from what they literally mean. Slang may also be peculiar to a region or a community, and therefore unintelligible outside it.

For example, the slang ‘Down Under’, as the country of Australia is commonly known, is practically unintelligible to people from other parts of the world.

Jargon, however, can be categorized broadly as per profession or subject, since in its technical avatar, it would fall into a specific classification.

Slang and jargon are often used loosely in the same sense, though there is a thin line of difference. The following are some examples to differentiate between jargon and slang:

- Did you hook up with him? (Slang)

- Get me his vitals . (Medical jargon)

- She’s an ace guitarist. (Slang)

- I really HTH . (Computer jargon)

Examples of Jargon

Medical jargon.

These are some examples of commonly used medical abbreviations and terminology. ➠ STAT – Immediately ➠ ABG – Arterial Blood Gas ➠ Vitals – Vital signs ➠ C-Section – Cesarean Section ➠ Claudication – Limping caused by a reduction in blood supply to the legs ➠ CAT/CT Scan – Computerized Axial Tomography ➠ MRI – Magnetic Resonance Imaging ➠ BP – Blood Pressure ➠ FX – Bone Fracture

Computer Jargon

Most of these examples are abbreviations, which can be likened to a shorthand code for the computer literate and the Internet savvy. ➠ FAQs – Frequently Asked Questions ➠ CYA – See you around ➠ RAM – Random Access Memory ➠ GB – Gigabyte ➠ ROM – Read-only Memory ➠ Backup – Duplicate a file ➠ BFF – Best Friends Forever ➠ HTH – Hope This Helps

Military Jargon

The following are some military jargon examples. ➠ AWOL – Away without official leave ➠ BOHICA – Bend over, here it comes again ➠ SOP – Standard Operating Procedure ➠ AAA – Anti-aircraft Artillery ➠ UAV – Unmanned Aerial Vehicle ➠ 11 Bravo – Infantry ➠ WHOA – War Heroes of America ➠ Fatigues – Camouflage uniforms ➠ TD – Temporary Duty ➠ SAM – Surface-to-Air missile

Law Enforcement Jargon

The following are some examples. ➠ APB – All Points Bulletin ➠ B&E – Breaking and Entering ➠ DUI – Driving Under the Influence ➠ CSI – Crime Scene Investigation ➠ Clean Skin – A person without a police record ➠ Miranda – Warning given during an arrest, advising about constitutional rights to remain silent and the right to legal aid. ➠ Perp – Perpetrator ➠ Social – Social Security Number

Business Jargon

The corporate world isn’t far behind when it comes to developing words and phrases that mean little to others. Business jargon includes a lot of words and abbreviations, which change even from department to department. Here are a few.

➠ Ear to Ear – Let’s discuss in detail over the phone ➠ In Loop – Keep me updated continuously ➠ Helicopter view – Overview ➠ Boil the ocean – Try for the impossible

Other Common Examples of Jargon

➠ UFO – Unidentified Flying Object ➠ Poker face – A blank expression ➠ Back burner – Something low in priority, putting something off till a later date ➠ On Cloud nine – Very happy ➠ Sweet tooth – A great love of all things sweet ➠ Ballpark figure – A numerical estimated value ➠ Gumshoe/Private Eye – Detective ➠ Shrink – Psychiatrist ➠ Slammer – Jail

Jargon examples in literature are spotted especially in the works of authors (Shakespeare, Dickens) that echo speech, characteristic of that period. Speech patterns in past times are markedly different from patterns that are prevalent, as will be the case in a few decades from now. Language evolves, just like everything else. Business jargon examples similarly, also demonstrate the evolution of language. This is the category that gave rise to words like ‘actionable’ (anything on which action can be taken) and ‘deintegrate’ (to disassemble) which until a few years ago, didn’t even exist.

Using slang and jargon has become such an everyday part of life that we rarely pay attention to how much of our speech is peppered with phrases that wouldn’t have made sense a few decades back. The very funny English language will never cease to amaze one with how much it evolves, and how phrases that were limited to a particular profession or even a demographic can become examples of jargon over time. Change is the only constant as the saying goes!

Like it? Share it!

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Further insights.

Privacy Overview

Does Your Child Use Jargon?

First time mothers.

You’re a first time mom, which is like going on an exciting journey with no roadmap whatsoever. You’re in a constant state of both buoyant joy and crushing exhaustion.

That’s why you appreciate the advice from your mom, your sister, all the moms in your life who love you and want you to succeed. Even though you’ve read all the books, done all the online research and then some, it’s reassuring to see what people you know have actually gone through.

The changes are coming so fast. Constant crying turns to gurgling and sometimes laughter. Erratic sleep, to snatches of sleep, to sleep training…eventually. Breastfeeding becomes bottle feeding and then eating solids.

I don’t understand

And when it comes to communication, random sounds become gurgling, then babbling, then…nonsense? The books didn’t mention this! And come to think of it, your circle of moms didn’t either. What’s going on?

What is jargon?

Your toddler is using jargon. Jargon is when kids say a string of nonsensical syllables or pretend words that make no sense, or maybe with only one word that makes sense. In other words it’s gibberish.

From birth your child is attempting to communicate. Crying is your child’s way of trying to get you to understand their wants and needs. Gurgling and cooing is their attempt at making different sounds. Babbling, or repeating syllables (mama, dada), comes next. And then comes jargon. It’s part of a natural process.

Jargon is your child’s way of imitating the speech patterns they hear all around them. That’s why when you listen in, or better yet, listen from a little far away, it sounds like they are speaking in actual sentences. Don’t get discouraged, because the more your child uses jargon, the closer they get to using real words.

Jargon is normal

The use of jargon is absolutely normal . Here’s a little snapshot of when and for how long your child may use jargon:

- 12 to 18 months: beginnings of jargon

- 18 to 22 months: uses jargon well

- 22 to 24 months: masters jargon

In the following year or two, your child goes from using and learning single words to talking nonstop. Also, by four years of age, much of what they say should be understood, even by strangers.

It’s amazing, isn’t it? To think that your tiny baby will one day be a bouncing ball of energy that won’t stop talking or moving. One day, sooner than you think, you might miss the days when your child was just a precious baby, silent except for the crying and the wailing. And the use of jargon is a crucial part in that process.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

1 thought on “Does Your Child Use Jargon?”

- Pingback: My Child Has a Hard Time Telling Me What He Wants - Fluens Childrens Therapy

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of jargon

(Entry 1 of 2)

Definition of jargon (Entry 2 of 2)

intransitive verb

- terminology

Examples of jargon in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'jargon.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Noun and Verb

Middle English, from Anglo-French jargun, gargon

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 3a

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 2

Phrases Containing jargon

- Chinook jargon

Articles Related to jargon

8 Ways to Avoid Business Jargon

Jargon isn't meaningless—but it's avoidable

Dictionary Entries Near jargon

jargon aphasia

Cite this Entry

“Jargon.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/jargon. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of jargon, medical definition, medical definition of jargon, more from merriam-webster on jargon.

Nglish: Translation of jargon for Spanish Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day, tendentious.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 19, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, your favorite band is in the dictionary, games & quizzes.

Jargon speech

Published Date : November 5, 2020

Reading Time :

Jargon speech refers to using specialized language, technical terms, or acronyms only understood by a specific group of people within a particular field or profession. While it can be efficient communication within that group, it can be confusing and alienating to those outside it. This can pose a significant challenge in public speaking , where communication needs to be clear and accessible to a broad audience.

Challenges of Jargon Speech:

- Loss of clarity : Jargon creates a barrier to understanding, potentially excluding a portion of your audience and hindering your message’s impact.

- Reduced credibility: Overusing jargon can be pretentious or condescending, undermining your trustworthiness and the message’s validity.

- Missed connection: Jargon can create distance between you and your audience, hindering engagement and emotional connection.

Avoiding Jargon Speech in Public Speaking:

- Know your audience: Tailor your language to your listeners’ level of understanding. What might be common terminology within your field might be completely new to them.

- Explain and translate: If you must use technical terms, define them clearly and simply the first time you use them. Consider offering alternatives or simpler synonyms.

- Focus on the meaning: Instead of relying solely on jargon, prioritize explaining the main ideas and goals you want your audience to understand.

- Use relatable examples: Illustrate your points with stories, analogies, or metaphors that connect with your audience’s experiences and knowledge.

- Seek feedback: Practice your speech in front of individuals outside your field and use their feedback to identify areas where jargon needs to be replaced with simpler language.

Alternatives to Jargon Speech:

- Use plain language: Opt for clear, concise, everyday language your audience can easily understand.

- Simplify complex concepts: Break down them into smaller, manageable chunks and explain them step-by-step.

- Focus on benefits: Instead of technical jargon, explain the benefits and real-world implications of your message for the audience.

- Tell stories: Use engaging stories and anecdotes to illustrate your points and make them more memorable.

Additional Tips:

- Consider taking a public speech class : Learning effective communication techniques and audience engagement strategies can help you develop the ability to adapt your language for different audiences.

- Actively listen to your audience: Listen to their reactions and body language to gauge their understanding and adjust your language accordingly.

- Embrace clear and concise communication: By prioritizing clarity and understanding, you can ensure your message resonates with your audience and achieves its intended impact.

Remember, effective public speaking is about connecting with your audience and delivering your message in a way that is clear, engaging, and accessible. By avoiding jargon and embracing clear communication, you can ensure your message reaches its full potential and resonates with everyone in the room.

You might also like

How Many Words is a 5-Minute Speech

Good Attention Getters for Speeches with 10+ Examples!

Quick Links

- Presentation Topics

Useful Links

- Start free trial

- The art of public speaking

- improve public speaking

- mastering public speaking

- public speaking coach

- professional speaking

- public speaking classes - Courses

- public speaking anxiety

- © Orai 2023

Have you ever watched an episode of House or Grey’s Anatomy with a huge question mark hovering above your head? Despite how interesting these television shows can be, you have to admit, you’re probably clueless about half the things they talk about in the show. You may also see gerund phrase examples .

- Nursing Jargon Examples – PDF

- Secrets of Good Business Writing