If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 7

- The presidency of Herbert Hoover

- The Great Depression

- FDR and the Great Depression

The New Deal

- The New Deal was a set of domestic policies enacted under President Franklin D. Roosevelt that dramatically expanded the federal government’s role in the economy in response to the Great Depression.

- Historians commonly speak of a First New Deal (1933-1934), with the “alphabet soup” of relief, recovery, and reform agencies it created, and a Second New Deal (1935-1938) that offered further legislative reforms and created the groundwork for today’s modern social welfare system.

- It was the massive military expenditures of World War II , not the New Deal, that eventually pulled the United States out of the Great Depression.

Origins of the New Deal

- relief (for the unemployed)

- recovery (of the economy through federal spending and job creation), and

- reform (of capitalism, by means of regulatory legislation and the creation of new social welfare programs). 2

The First New Deal (1933-1934)

The second new deal (1935-1938), the legacy of the new deal, what do you think.

- Franklin Roosevelt, " Address Accepting the Presidential Nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago ," July 2, 1932. Full text courtesy The American Presidency Project, University of California, Santa Barbara.

- See David M. Kennedy and Lizabeth Cohen, The American Pageant: A History of the American People , 15th ed. (Boston: Wadsworth, 2013), 754-277.

- Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty: An American History (New York: Norton, 2005), 829. Emphasis added.

- On industrial output, see Akira Iriye, American Foreign Policy Relations (1913), 119.

- On Keynes, see Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes: 1883–1946: Economist, Philosopher, Statesman (New York: MacMillan, 2003.)

- On Roosevelt's court-packing plan, see Burt Solomon, FDR v. The Constitution: The Court-Packing Fight and the Triumph of Democracy (New York: Walker & Co., 2003).

- See David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 131-287.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- AHR Interview

- History Unclassified

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Join the AHR Community

- About The American Historical Review

- About the American Historical Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

I ra K atznelson . Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Robert F. Himmelberg, I ra K atznelson . Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time , The American Historical Review , Volume 119, Issue 2, April 2014, Pages 471–473, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/119.2.471

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In Fear Itself , Ira Katznelson—drawing exhaustively upon the literature of the Roosevelt-Truman era, including his own extensive contributions, and upon fresh research—offers to illuminate “the origins of our own time.” Unlike the numerous available surveys of the New Deal, including the durably important works of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., William Leuchtenburg, Frank Freidel, Alonzo Hamby, and most recently David Kennedy, whose company this book should join, Fear Itself extends the search for the meaning and results of the New Deal beyond the 1930s and the war years into the immediate postwar era. It differs from them in its conclusions, too.

New Deal histories have generally concluded on a positive note, finding that, whatever its shortcomings, by taming business excesses, giving workers organizational opportunity, creating a safety net, and adopting compensatory fiscal policies, the New Deal laid an enduring basis for a fairer, relatively prosperous, and more stable form of liberal capitalist society. At one level, Katznelson affirms this view, as he acknowledges how, in a world increasingly dominated politically by brutal and ruthless autocracies, the New Deal's successes vindicated liberal democracy and made possible the eradication of fascist and Nazi power.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1937-5239

- Print ISSN 0002-8762

- Copyright © 2024 The American Historical Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Consequences of the Proposed “New Deal”

- Domestic Policy

- Federal Government

- Political Culture

- Political Economy

- Rights and Liberties

- October 31, 1932

Introduction

As the 1932 presidential campaign drew to a close, Hoover fired back against his Democratic challenger in a speech at Madison Square Garden in New York City. He seized on proposals made by Democratic leaders in Congress, and Roosevelt’s own words from the Commonwealth Club address, to portray the opposition as dangerously irresponsible and committed to a philosophy at odds with that of the American Founding. The president reminded his listeners of the progress made in the past thirty years, and while he admitted that the past three years had brought considerable distress, he asserted that the system established by the Founders in the Constitution had proven capable of weathering the worst of the crisis.

Source: “Address at Madison Square Garden in New York City,” October 31, 1932. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=23317.

This campaign is more than a contest between two men. It is more than a contest between two parties. It is a contest between two philosophies of government.

We are told by the opposition that we must have a change, that we must have a new deal. It is not the change that comes from normal development of national life to which I object or you object, but the proposal to alter the whole foundations of our national life which have been builded through generations of testing and struggle, and of the principles upon which we have made this Nation. The expressions of our opponents must refer to important changes in our economic and social system and our system of government; otherwise they would be nothing but vacuous words. And I realize that in this time of distress many of our people are asking whether our social and economic system is incapable of that great primary function of providing security and comfort of life to all of the firesides of 25 million homes in America, whether our social system provides for the fundamental development and progress of our people, and whether our form of government is capable of originating and sustaining that security and progress.

This question is the basis upon which our opponents are appealing to the people in their fear and their distress. They are proposing changes and so-called new deals which would destroy the very foundations of the American system of life.

Our people should consider the primary facts before they come to the judgment – not merely through political agitation, the glitter of promise, and the discouragement of temporary hardships – whether they will support changes which radically affect the whole system which has been builded during these six generations of the toil of our fathers. They should not approach the question in the despair with which our opponents would clothe it.

Our economic system has received abnormal shocks during the last three years which have temporarily dislocated its normal functioning. These shocks have in a large sense come from without our borders, and I say to you that our system of government has enabled us to take such strong action as to prevent the disaster which would otherwise have come to this Nation. It has enabled us further to develop measures and programs which are now demonstrating their ability to bring about restoration and progress.

We must go deeper than platitudes and emotional appeals of the public platform in the campaign if we will penetrate to the full significance of the changes which our opponents are attempting to float upon the wave of distress and discontent from the difficulties through which we have passed. We can find what our opponents would do after searching the record of their appeals to discontent, to group and sectional interest. To find that, we must search for them in the legislative acts which they sponsored and passed in the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives in the last session of Congress. We must look into both the measures for which they voted and in which they were defeated. We must inquire whether or not the Presidential and Vice-Presidential candidates have disavowed those acts. If they have not, we must conclude that they form a portion and are a substantial indication of the profound changes in the new deal which is proposed.

And we must look still further than this as to what revolutionary changes have been proposed by the candidates themselves.

We must look into the type of leaders who are campaigning for the Democratic ticket, whose philosophies have been well known all their lives and whose demands for a change in the American system are frank and forceful. I can respect the sincerity of these men in their desire to change our form of government and our social and our economic system, though I shall do my best tonight to prove they are wrong. I refer particularly to Senator Norris, 1 Senator La Follette, 2 Senator Cutting, 3 Senator Huey Long, 4 Senator Wheeler, 5 William Randolph Hearst, 6 and other exponents of a social philosophy different from the traditional philosophies of the American people. Unless these men have felt assurance of support to their ideas they certainly would not be supporting these candidates and the Democratic Party. The zeal of these men indicates that they must have some sure confidence that they will have a voice in the administration of this Government.

I may say at once that the changes proposed from all these Democratic principals and their allies are of the most profound and penetrating character. If they are brought about, this will not be the America which we have known in the past. . . .

Now, our American system is founded on a peculiar conception of self-government designed to maintain an equality of opportunity to the individual, and through decentralization it brings about and maintains these responsibilities. The centralization of government will undermine these responsibilities and will destroy the system itself.

Our Government differs from all previous conceptions, not only in the decentralization but also in the independence of the judicial arm of the Government.

Our Government is founded on a conception that in times of great emergency, when forces are running beyond the control of individuals or cooperative action, beyond the control of local communities or the States, then the great reserve powers of the Federal Government should be brought into action to protect the people. But when these forces have ceased there must be a return to State, local, and individual responsibility.

The implacable march of scientific discovery with its train of new inventions presents every year new problems to government and new problems to the social order. Questions often arise whether, in the face of the growth of these new and gigantic tools, democracy can remain master in its own house and can preserve the fundamentals of our American system. I contend that it can, and I contend that this American system of ours has demonstrated its validity and superiority over any system yet invented by human mind. It has demonstrated it in the face of the greatest test of peacetime history – that is the emergency which we have passed in the last three years.

When the political and economic weakness of many nations of Europe, the result of the World War and its aftermath, finally culminated in the collapse of their institutions, the delicate adjustments of our economic and social and governmental life received a shock unparalleled in our history. No one knows that better than you of New York. No one knows its causes better than you. That the crisis was so great that many of the leading banks sought directly or indirectly to convert their assets into gold or its equivalent with the result that they practically ceased to function as credit institutions is known to you; that many of our citizens sought flight for their capital to other countries; that many of them attempted to hoard gold in large amounts you know. These were but superficial indications of the flight of confidence and the belief that our Government could not overcome these forces.

Yet these forces were overcome – perhaps by narrow margins – and this demonstrates that our form of government has the capacity. It demonstrates what the courage of a nation can accomplish under the resolute leadership of the Republican Party. And I say the Republican Party because our opponents, before and during the crisis, proposed no constructive program, though some of their members patriotically supported ours for which they deserve on every occasion the applause of patriotism. Later on in the critical period, the Democratic House of Representatives did develop the real thought and ideas of the Democratic Party. They were so destructive that they had to be defeated. They did delay the healing of our wounds for months.

Now, in spite of all these obstructions we did succeed. Our form of government did prove itself equal to the task. We saved this Nation from a generation of chaos and degeneration; we preserved the savings, the insurance policies, gave a fighting chance to men to hold their homes. We saved the integrity of our Government and the honesty of the American dollar. And we installed measures which today are bringing back recovery. Employment, agriculture, and business – all of these show the steady, if slow, healing of an enormous wound.

As I left Washington, our Government departments communicated to me the fact that the October statistics on employment show that since the first day of July, the men returned to work in the United States exceed one million.

I therefore contend that the problem of today is to continue these measures and policies to restore the American system to its normal functioning, to repair the wounds it has received, to correct the weaknesses and evils which would defeat that system. To enter upon a series of deep changes now, to embark upon this inchoate new deal which has been propounded in this campaign would not only undermine and destroy our American system but it will delay for months and years the possibility of recovery. . . .

Now, to go back to my major thesis – the thesis of the longer view. Before we enter into courses of deep-seated change and of the new deal, I would like you to consider what the results of this American system have been during the last 30 years – that is, a single generation. For if it can be demonstrated that by this means, our unequaled political, social, and economic system, we have secured a lift in the standards of living and the diffusion of comfort and hope to men and women, the growth of equality of opportunity, the widening of all opportunity such as had never been seen in the history of the world, then we should not tamper with it and destroy it, but on the contrary we should restore it and, by its gradual improvement and perfection, foster it into new performance for our country and for our children.

Now, if we look back over the last generation we find that the number of our families and, therefore, our homes, has increased from about 16 to about 25 million, or 62 percent. In that time we have builded for them 15 million new and better homes. We have equipped 20 million out of these 25 million homes with electricity; thereby we have lifted infinite drudgery from women and men. The barriers of time and space have been swept away in this single generation. Life has been made freer, the intellectual vision of every individual has been expanded by the installation of 20 million telephones, 12 million radios, and the service of 20 million automobiles. Our cities have been made magnificent with beautiful buildings, parks, and playgrounds. Our countryside has been knit together with splendid roads. We have increased by 12 times the use of electrical power and thereby taken sweat from the backs of men. In the broad sweep real wages and purchasing power of men and women have steadily increased. New comforts have steadily come to them. The hours of labor have decreased, the 12-hour day has disappeared, even the 9-hour day has almost gone. We are now advocating the 5-day week. During this generation the portals of opportunity to our children have ever widened. While our population grew by but 62 percent, yet we have increased the number of children in high schools by 700 percent, and those in institutions of higher learning by 300 percent. With all our spending, we multiplied by six times the savings in our banks and in our building and loan associations. We multiplied by 1,200 percent the amount of our life insurance. With the enlargement of our leisure we have come to a fuller life; we have gained new visions of hope; we are more nearly realizing our national aspirations and giving increased scope to the creative power of every individual and expansion of every man’s mind.

Now, our people in these 30 years have grown in the sense of social responsibility. There is profound progress in the relation of the employer to the employed. We have more nearly met with a full hand the most sacred obligation of man, that is, the responsibility of a man to his neighbor. Support to our schools, hospitals, and institutions for the care of the afflicted surpassed in totals by billions the proportionate service in any period in any nation in the history of the world.

Now, three years ago there came a break in this progress. A break of the same type we have met 15 times in a century and yet have recovered from. But 18 months later came a further blow by the shocks transmitted to us from earthquakes of the collapse of nations throughout the world as the aftermath of the World War. The workings of this system of ours were dislocated. Businessmen and farmers suffered, and millions of men and women are out of jobs. Their distress is bitter. I do not seek to minimize it, but we may thank God that in view of the storm that we have met that 30 million still have jobs, and yet this does not distract our thoughts from the suffering of the 10 million.

But I ask you what has happened. This 30 years of incomparable improvement in the scale of living, of advance of comfort and intellectual life, of security, of inspiration, and ideals did not arise without right principles animating the American system which produced them. Shall that system be discarded because vote-seeking men appeal to distress and say that the machinery is all wrong and that it must be abandoned or tampered with? Is it not more sensible to realize the simple fact that some extraordinary force has been thrown into the mechanism which has temporarily deranged its operation? Is it not wiser to believe that the difficulty is not with the principles upon which our American system is founded and designed through all these generations of inheritance? Should not our purpose be to restore the normal working of that system which has brought to us such immeasurable gifts, and not to destroy it?

Now, in order to indicate to you that the proposals of our opponents will endanger or destroy our system, I propose to analyze a few of them in their relation to these fundamentals which I have stated.

First: A proposal of our opponents that would break down the American system is the expansion of governmental expenditure by yielding to sectional and group raids on the Public Treasury. The extension of governmental expenditures beyond the minimum limit necessary to conduct the proper functions of the Government enslaves men to work for the Government. If we combine the whole governmental expenditures – national, State, and municipal – we will find that before the World War each citizen worked, theoretically, 25 days out of each year for the Government. In 1924, he worked 46 days out of the year for the Government. Today he works, theoretically, for the support of all forms of Government 61 days out of the year.

No nation can conscript its citizens for this proportion of men’s and women’s time without national impoverishment and without the destruction of their liberties. Our Nation cannot do it without destruction to our whole conception of the American system. The Federal Government has been forced in this emergency to unusual expenditure, but in partial alleviation of these extraordinary and unusual expenditures the Republican administration has made a successful effort to reduce the ordinary running expenses of the Government. . . .

Second: Another proposal of our opponents which would destroy the American system is that of inflation of the currency. The bill which passed the last session of the Democratic House called upon the Treasury of the United States to issue $2,300 million in paper currency that would be unconvertible into solid values. Call it what you will, greenbacks or fiat money. It was the same nightmare which overhung our own country for years after the Civil War. . . .

The use of this expedient by nations in difficulty since the war in Europe has been one of the most tragic disasters to equality of opportunity and the independence of man. . . .

Third: In the last session of the Congress, under the personal leadership of the Democratic Vice-Presidential candidate, and their allies in the Senate, they enacted a law to extend the Government into personal banking business. I know it is always difficult to discuss banks. There seems to be much prejudice against some of them, but I was compelled to veto that bill out of fidelity to the whole American system of life and government. . . .

They failed to pass this bill over my veto. But you must not be deceived. This is still in their purposes as a part of the new deal, and no responsible candidate has yet disavowed it.

Fourth: Another proposal of our opponents which would wholly alter our American system of life is to reduce the protective tariff to a competitive tariff for revenue. . . .

Fifth: Another proposal is that the Government go into the power business. . . .

I have stated unceasingly that I am opposed to the Federal Government going into the power business. I have insisted upon rigid regulation. The Democratic candidate has declared that under the same conditions which may make local action of this character desirable, he is prepared to put the Federal Government into the power business. He is being actively supported by a score of Senators in this campaign, many of whose expenses are being paid by the Democratic National Committee, who are pledged to Federal Government development and operation of electrical power. . . .

Sixth: I may cite another instance of absolutely destructive proposals to our American system by our opponents, and I am talking about fundamentals and not superficialities.

Recently there was circulated through the unemployed in this city and other cities, a letter from the Democratic candidate in which he stated that he would support measures for the inauguration of self-liquidating public works such as the utilization of water resources, flood control, land reclamation, to provide employment for all surplus labor at all times.

I especially emphasize that promise to promote “employment for all surplus labor at all times” – by the Government. I at first could not believe that anyone would be so cruel as to hold out a hope so absolutely impossible of realization to those 10 million who are unemployed and suffering. But the authenticity of that promise has been verified. And I protest against such frivolous promises being held out to a suffering people. It is easy to demonstrate that no such employment can be found. But the point that I wish to make here and now is the mental attitude and spirit of the Democratic Party that would lead them to attempt this or to make a promise to attempt it. That is another mark of the character of the new deal and the destructive changes which mean the total abandonment of every principle upon which this Government and this American system are founded. If it were possible to give this employment to 10 million people by the Government – at the expense of the rest of the people – it would cost upwards of $9 billion a year.

The stages of this destruction would be first the destruction of Government credit, then the destruction of the value of Government securities, the destruction of every fiduciary trust in our country, insurance policies and all. It would pull down the employment of those who are still at work by the high taxes and the demoralization of credit upon which their employment is dependent. It would mean the pulling and hauling of politics for projects and measures, the favoring of localities and sections and groups. It would mean the growth of a fearful bureaucracy which, once established, could never be dislodged. If it were possible, it would mean one-third of the electorate would have Government jobs, earnest to maintain this bureaucracy and to control the political destinies of the country. . . .

I have said before, and I want to repeat on this occasion, that the only method by which we can stop the suffering and unemployment is by returning our people to their normal jobs in their normal homes, carrying on their normal functions of living. This can be done only by sound processes of protecting and stimulating recovery of the existing system upon which we have builded our progress thus far – preventing distress and giving such sound employment as we can find in the meantime. . . .

In order that we may get at the philosophical background of the mind which pronounces the necessity for profound change in our economic system and a new deal, I would call your attention to an address delivered by the Democratic candidate in San Francisco early in October. 7

Our industrial plant is built. The problem just now is whether under existing conditions it is not overbuilt. Our last frontier has long since been reached. There is practically no more free land. There is no safety valve in the Western prairies where we can go for a new start. . . . The mere building of more industrial plants, the organization of more corporations is as likely to be as much a danger as a help. . . . Our task now is not the discovery of natural resources or necessarily the production of more goods, it is the sober, less dramatic business of administering the resources and plants already in hand. . . . establishing markets for surplus production, of meeting the problem of under-consumption, distributing the wealth and products more equitably and adopting the economic organization to the service of the people. . . .

Now, there are many of these expressions with which no one would quarrel. But I do challenge the whole idea that we have ended the advance of America, that this country has reached the zenith of its power and the height of its development. That is the counsel of despair for the future of America. That is not the spirit by which we shall emerge from this depression. That is not the spirit which has made this country. If it is true, every American must abandon the road of countless progress and countless hopes and unlimited opportunity. I deny that the promise of American life has been fulfilled, for that means we have begun the decline and the fall. No nation can cease to move forward without degeneration of spirit.

I could quote from gentlemen who have emitted this same note of profound pessimism in each economic depression going back for 100 years. What the Governor 8 has overlooked is the fact that we are yet but on the frontiers of development of science and of invention. I have only to remind you that discoveries in electricity, the internal-combustion engine, the radio – all of which have sprung into being since our land was settled – have in themselves represented the greatest advances made in America. This philosophy upon which the Governor of New York proposes to conduct the Presidency of the United States is the philosophy of stagnation and of despair. It is the end of hope. The destinies of this country cannot be dominated by that spirit in action. It would be the end of the American system.

I have recited to you some of the items in the progress of this last generation. Progress in that generation was not due to the opening up of new agricultural land; it was due to the scientific research, the opening of new invention, new flashes of light from the intelligence of our people. These brought the improvements in agriculture and in industry. There are a thousand inventions for comfort and the expansion of life yet in the lockers of science that have not yet come to light. We are only upon their frontiers. As for myself, I am confident that if we do not destroy our American system, if we continue to stimulate scientific research, if we continue to give it the impulse of initiative and enterprise, if we continue to build voluntary cooperation instead of financial concentration, if we continue to build into a system of free men, my children will enjoy the same opportunity that has come to me and to the whole 120 million of my countrymen. I wish to see American Government conducted in that faith and hope. . . .

My countrymen, the proposals of our opponents represent a profound change in American life – less in concrete proposal, bad as that may be, than by implication and by evasion. Dominantly in their spirit they represent a radical departure from the foundations of 150 years which have made this the greatest Nation in the world. This election is not a mere shift from the ins to the outs. It means the determining of the course of our Nation over a century to come.

Now, my conception of America is a land where men and women may walk in ordered liberty, where they may enjoy the advantages of wealth not concentrated in the hands of a few but diffused through the opportunity of all, where they build and safeguard their homes, give to their children the full opportunities of American life, where every man shall be respected in the faith that his conscience and his heart direct him to follow, and where people secure in their liberty shall have leisure and impulse to seek a fuller life. That leads to the release of the energies of men and women, to the wider vision and higher hope. It leads to opportunity for greater and greater service not alone of man to man in our country but from our country to the world. It leads to health in body and a spirit unfettered, youthful, eager with a vision stretching beyond the farthest horizons with a mind open and sympathetic and generous. But that must be builded upon our experience with the past, upon the foundations which have made this country great. It must be the product of the development of our truly American system.

- 1. George W. Norris (R-NE)

- 2. Robert M. La Follette, Jr. (R-WI)

- 3. Bronson M. Cutting (R -NM)

- 4. Huey Long (D -LA)

- 5. Burton K. Wheeler (D -MT)

- 6. William Randolph Hearst was a highly influential newspaper publisher of progressive views. Although ambitious for a leading role in New York Democratic politics, he was far more successful as a media magnate, and by the 1920s owned twenty daily and eleven Sunday newspapers in thirteen American cities.

- 7. Franklin Roosevelt’s “Commonwealth Address” (Document 14)

- 8. Franklin D. Roosevelt

Campaign Speech

The consequences of the proposed new deal, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: October 29, 2009

The New Deal was a series of programs and projects instituted during the Great Depression by President Franklin D. Roosevelt that aimed to restore prosperity to Americans. When Roosevelt took office in 1933, he acted swiftly to stabilize the economy and provide jobs and relief to those who were suffering. Over the next eight years, the government instituted a series of experimental New Deal projects and programs, such as the CCC , the WPA , the TVA, the SEC and others. Roosevelt’s New Deal fundamentally and permanently changed the U.S. federal government by expanding its size and scope—especially its role in the economy.

New Deal for the American People

On March 4, 1933, during the bleakest days of the Great Depression , newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his first inaugural address before 100,000 people on Washington’s Capitol Plaza.

“First of all,” he said, “let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

He promised that he would act swiftly to face the “dark realities of the moment” and assured Americans that he would “wage a war against the emergency” just as though “we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.” His speech gave many people confidence that they’d elected a man who was not afraid to take bold steps to solve the nation’s problems.

Did you know? Unemployment levels in some cities reached staggering levels during the Great Depression: By 1933, Toledo, Ohio's had reached 80 percent, and nearly 90 percent of Lowell, Massachusetts, was unemployed.

The next day, Roosevelt declared a four-day bank holiday to stop people from withdrawing their money from shaky banks. On March 9, Congress passed Roosevelt’s Emergency Banking Act, which reorganized the banks and closed the ones that were insolvent.

In his first “ fireside chat ” three days later, the president urged Americans to put their savings back in the banks, and by the end of the month almost three quarters of them had reopened.

The First Hundred Days

Roosevelt’s quest to end the Great Depression was just beginning, and would ramp up in what came to be known as “ The First 100 Days .” Roosevelt kicked things off by asking Congress to take the first step toward ending Prohibition —one of the more divisive issues of the 1920s—by making it legal once again for Americans to buy beer. (At the end of the year, Congress ratified the 21st Amendment and ended Prohibition for good.)

In May, he signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act into law, creating the TVA and enabling the federal government to build dams along the Tennessee River that controlled flooding and generated inexpensive hydroelectric power for the people in the region.

That same month, Congress passed a bill that paid commodity farmers (farmers who produced things like wheat, dairy products, tobacco and corn) to leave their fields fallow in order to end agricultural surpluses and boost prices.

June’s National Industrial Recovery Act guaranteed that workers would have the right to unionize and bargain collectively for higher wages and better working conditions; it also suspended some antitrust laws and established a federally funded Public Works Administration.

In addition to the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Tennessee Valley Authority Act and the National Industrial Recovery Act, Roosevelt had won passage of 12 other major laws, including the Glass-Steagall Act (an important banking bill) and the Home Owners’ Loan Act, in his first 100 days in office.

Almost every American found something to be pleased about and something to complain about in this motley collection of bills, but it was clear to all that FDR was taking the “direct, vigorous” action that he’d promised in his inaugural address.

Second New Deal

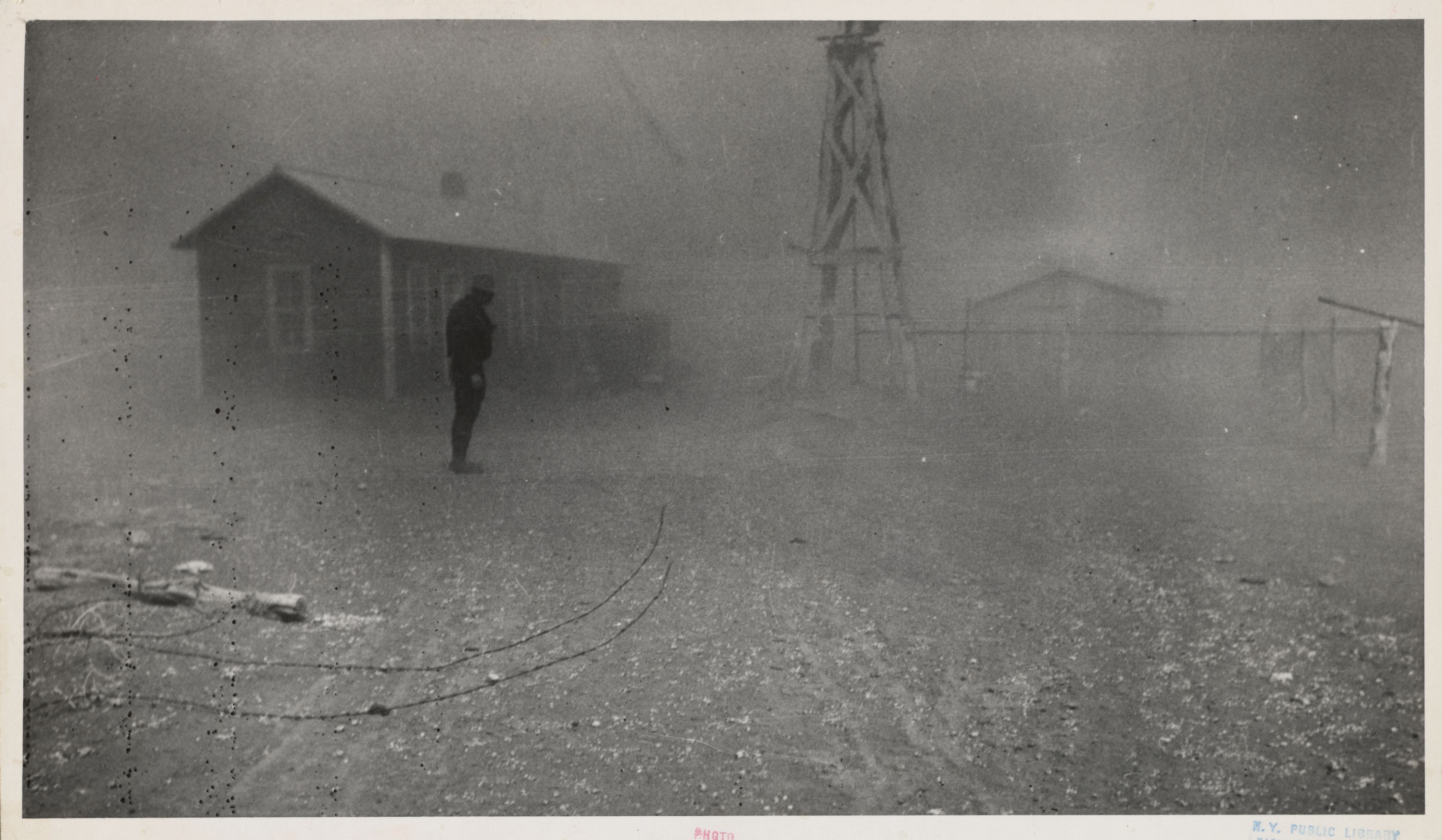

Despite the best efforts of President Roosevelt and his cabinet, however, the Great Depression continued. Unemployment persisted, the economy remained unstable, farmers continued to struggle in the Dust Bowl and people grew angrier and more desperate.

So, in the spring of 1935, Roosevelt launched a second, more aggressive series of federal programs, sometimes called the Second New Deal.

In April, he created the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to provide jobs for unemployed people. WPA projects weren’t allowed to compete with private industry, so they focused on building things like post offices, bridges, schools, highways and parks. The WPA also gave work to artists, writers, theater directors and musicians.

In July 1935, the National Labor Relations Act , also known as the Wagner Act, created the National Labor Relations Board to supervise union elections and prevent businesses from treating their workers unfairly. In August, FDR signed the Social Security Act of 1935, which guaranteed pensions to millions of Americans, set up a system of unemployment insurance and stipulated that the federal government would help care for dependent children and the disabled.

In 1936, while campaigning for a second term, FDR told a roaring crowd at Madison Square Garden that “The forces of ‘organized money’ are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.”

He went on: “I should like to have it said of my first Administration that in it the forces of selfishness and of lust for power met their match, [and] I should like to have it said of my second Administration that in it these forces have met their master.”

This FDR had come a long way from his earlier repudiation of class-based politics and was promising a much more aggressive fight against the people who were profiting from the Depression-era troubles of ordinary Americans. He won the election by a landslide.

Still, the Great Depression dragged on. Workers grew more militant: In December 1936, for example, the United Auto Workers strike at a GM plant in Flint, Michigan lasted for 44 days and spread to some 150,000 autoworkers in 35 cities.

By 1937, to the dismay of most corporate leaders, some 8 million workers had joined unions and were loudly demanding their rights.

The End of the New Deal?

Meanwhile, the New Deal itself confronted one political setback after another. Arguing that they represented an unconstitutional extension of federal authority, the conservative majority on the Supreme Court had already invalidated reform initiatives like the National Recovery Administration and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration.

In order to protect his programs from further meddling, in 1937 President Roosevelt announced a plan to add enough liberal justices to the Court to neutralize the “obstructionist” conservatives.

This “ Court-packing ” turned out to be unnecessary—soon after they caught wind of the plan, the conservative justices started voting to uphold New Deal projects—but the episode did a good deal of public-relations damage to the administration and gave ammunition to many of the president’s Congressional opponents.

That same year, the economy slipped back into a recession when the government reduced its stimulus spending. Despite this seeming vindication of New Deal policies, increasing anti-Roosevelt sentiment made it difficult for him to enact any new programs.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II . The war effort stimulated American industry and, as a result, effectively ended the Great Depression .

The New Deal and American Politics

From 1933 until 1941, President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs and policies did more than just adjust interest rates, tinker with farm subsidies and create short-term make-work programs.

They created a brand-new, if tenuous, political coalition that included white working people, African Americans and left-wing intellectuals. More women entered the workforce as Roosevelt expanded the number of secretarial roles in government. These groups rarely shared the same interests—at least, they rarely thought they did— but they did share a powerful belief that an interventionist government was good for their families, the economy and the nation.

Their coalition has splintered over time, but many of the New Deal programs that bound them together—Social Security, unemployment insurance and federal agricultural subsidies, for instance—are still with us today.

Photo Galleries

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

FDR and the New Deal Essay

Aims/objectives, thesis statement, introduction, literature review, research methods.

Aim of the paper is to explore the events of Great Depression and its impact on U.S economy. The paper strives to focus on the ‘New Deal’ offered by the President to address the issues related to Great Depression. The impact of New Deal on economy is also presented in the paper.

On the basis of explorative research made for this paper it is hypothesized that the FDR’s actions were effective to shorten the Depression and has perpetual impacts on U.S economy.

Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) was nominated as the President of United States in the summer of 1932. Roosevelt, in his acceptance speech, addressed different problems faced by the American people due to the Great Depression. He pledged to offer a new deal to resolve the grave scenario. Roosevelt won by a huge margin. (Powell, 2004) FDR’s New Deal in fact, served as a catalyst for the economy and different programs set the economy to recover from the disastrous effects of the Great Depression.

Literature review will encompass theoretical books, articles in magazines and internet as well as the research studies on the topic under analysis. It will focus on the condition of Economy during Great Depression. The economy, in fact, was facing a total collapse when FDR assumed power as the President. Unemployment hit thirty percent; inflation was at its peak, while GDP was critically down by fifty percent. This phenomenon is called ‘Great Depression’ which hit the highest level in the early part of 1933. (Powell, 2004) The period of FDR in the office, in the decade of 1930, can be classified as; the First New Deal during 1933 to 1935, characterized by different relief programs related to the problems of unemployment. The Second New Deal, during the years 1935 to 1037 was featured by different reforms related to economic and social problems.

According to some scholars, the New Deal ineffectively played with the theme of establishing close relations between government and business. However, some of these endeavors did not survive after World War II. The other group of scholars highlights the phenomenon that the initiatives taken by the New Deal pointed to almost new power-sharing among three primary economic players- the bankers, brokers and the businessmen. (Barnanke, 2004).

Different programs were initiated which included; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation- focusing on providing guarantee on deposits in banks; Securities and Exchange Commission- with the primary task of regulating and controlling the stock market; and the Social Security System- responsible for providing pensions on the basis of contributions made by elderly during their jobs. (Smilely, 2003).

The research will primarily focus on analyzing the secondary data available in theoretical books, magazines and internet. On the basis of the exploration made, a deep analysis and an in-depth opinion will be presented supported by authentic resources.

The New Deal promised by Roosevelt to the Americans was aimed at pulling the country out of depression. In the early days of his presidency, administration of Roosevelt initiated a passage of different laws related to banking reforms, relief programs for lifting emergency along with different other agricultural and work relief programs. (Mcelvaine, 1993)By the year 1939, FDR’s New Deal had practically supported in improving the general standards of lives suffered from the disastrous effects of Great Depression. Moreover, in the long-run, the programs of New Deal served as a precedent particularly for the federal government to assume a primary role in the social and economic affairs of the nation. (Sowell, 2007) It could be concluded, on the basis of arguments presented in the paper, that the FDR’s New Deal was successful in pulling the economy from Great Depression and has perpetual impact on the economy of United States.

Barnanke, B (2004) Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton University Press.

Powell, J (2004) FDR’s Folly: How Roosevelt and His New Deal Prolonged the Great Depression . Three Rivers Press.

Mcelvaine, R (1993) The Great Depression: American 1929-1941. Three Rivers Press.

Sowell, Thomas.(2007) Economic Facts and Fallacies. Basic Books.

Smilely, G (2003) Rethinking the Great Depression. Ivan R. Dee, Publisher.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, October 2). FDR and the New Deal. https://ivypanda.com/essays/fdr-and-the-new-deal/

"FDR and the New Deal." IvyPanda , 2 Oct. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/fdr-and-the-new-deal/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'FDR and the New Deal'. 2 October.

IvyPanda . 2021. "FDR and the New Deal." October 2, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/fdr-and-the-new-deal/.

1. IvyPanda . "FDR and the New Deal." October 2, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/fdr-and-the-new-deal/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "FDR and the New Deal." October 2, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/fdr-and-the-new-deal/.

- FDR Impacts on American Economy of New Deal

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Plans to Combat the Great Depression

- FDR’s New Deal: Democratic Platform

- Roosevelt’s First New Deal and the Second New Deal

- New Deal in Franklin Delano Rosevelt's Politics

- Leadership and Total Quality Management

- Franklin Roosevelt and The New Deal

- “The Presidency of Franklin D Roosevelt” by Oscar Bernal

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Great Depression

- Franklin D. Roosevelt's Presidential Era

- Cultures of Iroquois and English

- The Intentions and the Causes of the Monroe Doctrine

- Lyndon Johnson, the Tonkin Gulf Resolution

- America in 1920s: Great Depression

- The United States' History of 1865-1900

- The Magazine

- City Journal

- Contributors

- Manhattan Institute

- Email Alerts

Whose New Deal?

Two books offer dueling accounts of Franklin Roosevelt’s transformative governance.

The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights: The Untold Story of FDR’s Concentration Camps, Censorship, and Mass Surveillance , by David T. Beito (Independent Institute, 404 pp., $20.48)

Taming the Street: The Old Guard, the New Deal, and FDR’s Fight to Regulate American Capitalism , by Diana B. Henriques (Random House, 464 pp., $20.02)

The New Deal reshaped American life. President Franklin Roosevelt’s signature programs turned our federal republic into a national one, made welfare a central duty of the national government, and regulated businesses and citizens in ways and to an extent previously unimaginable. Two recent books offer clashing visions of the New Deal era and of its enduring impact on American life.

Historian David Beito’s The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights is an almost unalloyed tale of oppression. While most New Deal critics have focused on its economic policies or threats to property rights, Beito details how the Roosevelt administration used government power to subvert free speech, personal privacy, and other basic liberties. The book chronicles the extent of the administration’s overreach, which involved everything from shutting down newspapers to prosecuting New Deal opponents.

Beito illustrates how threats to property rights and civil rights in the New Deal could go together, especially for companies that wanted to broadcast over the air. Roosevelt told the newly created Federal Communications Commission to spike applications from radio stations hostile to the administration. They also discouraged anti-FDR broadcasts. In 1940, for example, the FCC blocked the purchase of a 15-minute segment by the antiwar America First Committee. Such efforts prompted companies to self-censor their content to avoid offending the administration. When an NBC commentator lightly attacked FDR on radio, an NBC vice president phoned the White House to say that the network would take him off the air.

Beito highlights the American Civil Liberties Union’s lamentable role in those and other abuses. The ACLU often acted less like champions of civil liberties than partisans for the Democratic Party. The group defended FDR’s radio crackdown, and its publicity director said that free speech shouldn’t apply over the airwaves. The group’s Massachusetts affiliate celebrated the prosecution of the magazine Social Justice for its anti-administration stance. Morris Ernst, a prominent ACLU attorney, even wrote to the president with a plan to examine FDR opponents’ tax returns. These examples are eye-opening for readers who might assume that the ACLU’s willingness to condone restrictions on free expression is a more recent development.

Civil rights often suffer during wartime, and World War II was no exception. Beito chronicles the Roosevelt administration’s extreme efforts to hound the opposition during the war years. He details FDR’s personal demands for the removal and internment of Japanese Americans (which the ACLU’s board endorsed), and his administration’s efforts to block newspapers that opposed him from the mails. Attorney General Francis Biddle, for example, called the nation’s leading black publisher into his office and complained about its criticism of the administration. Biddle laid several supposedly offending newspapers down and said he would “shut them all up.”

Beito’s dour portrait of the FDR administration contrasts with that painted by Diana Henriques, a celebrated financial journalist. In Taming the Street , Henriques chronicles FDR and his team’s efforts to regulate securities markets and bring the New York Stock Exchange to heel. Taming is an unvarnished morality tale, pitting heroic New Dealers against benighted plutocrats eager to commit fraud and cheat the poor.

As is the case with many histories, one can enjoy Henriques’s book without sharing its premises; whether FDR was lovable or NYSE president Dick Whitney was a crook has little bearing on the merits of New Deal securities regulations. And though Henriques has a clear political perspective, Taming is an enjoyable read. She grippingly portrays the raw, billion-dollar drama of politicians fighting big banks and brokers. The scene of Whitney walking out of the stock exchange and asking his brother at the J.P. Morgan office for funds to cover up his embezzlement vividly encapsulates the cozy world of early twentieth-century finance. Similarly, she recalls how Joseph Kennedy, the first chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission, regaled FDR at his Potomac estate with fresh New England seafood and penny-ante poker, illustrating the backroom nature of D.C. politics.

Henriques’s celebratory tone obscures some problems with the New Deal campaign. While she details the battle between utility companies and government regulators, she neglects to discuss the associated civil-liberties violations, which Beito’s book covers in depth. Senator Hugo Black, whom FDR later appointed to the Supreme Court, and his congressional committee reviewed private tax returns, including those from opposing congressmen, and blanket-searched telegram records to smear utility companies’ public-influence campaign. This ranks among the most invasive actions in congressional history; it’s almost wholly absent from Henriques’s account.

Taming ’s black-and-white tale has something of the flavor of prevailing liberal opinion in the mid-twentieth century: the New Deal was good, and its opponents were bad. But its somewhat old-fashioned assessment avoids the pitfalls of many academic histories today. It refuses to focus on race or gender and is unabashedly interested in the doings of the prominent and powerful, not in telling “history from the bottom up.”

The Roosevelt administration left an indelible imprint on the United States. While Americans support many New Deal-descended programs to this day, they bristle at the invasive government that FDR brought into being. As Beito and Henriques’s dueling accounts suggest, the New Deal’s legacy remains up for debate.

Judge Glock is the director of research and a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal .

Photo by Roy Rochlin/Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Further Reading

Copyright © 2024 Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Eye on the News

- From the Magazine

- Books and Culture

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

EIN #13-2912529

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Kate Middleton Photo That Was Too Good to Be True

By Jessica Winter

It’s such a lovely photograph—if only it were real. The occasion is Mothering Sunday, the U.K. equivalent of Mother’s Day, which fell this year in March. Mom sits at the center, big toothpaste smile, and she’s having a great hair day. She’s pulling her two little ones close to her on either side, and her oldest boy is just behind, beaming affection, his arms slung around her. They all seem to be laughing at whatever the photographer—Dad—is saying or doing. It’s sweater weather, and they look so cozy in their knits (that fluttery scalloped collar under the girl’s cardigan! A dream!). This picture is why people have kids; it’s why people scroll Instagram wondering why everybody else’s family is nicer than theirs. If there was something faintly uncanny about the photo—did Mom’s head seem to float on a different plane? Was her neck somehow foreshortened, or was that just the cowl-neck on her sweater?—maybe it was just the sense of otherworldly perfection.

Because the mom in the picture is Catherine, Princess of Wales, who has been recuperating from abdominal surgery and been out of the public eye since Christmas, and because the credited photographer is William, the future King of England, the image was released to news agencies and posted to the British Royal Family’s social-media accounts, pointedly dated “2024.” Sweet as the picture was, something possibly ghoulish haunted the motivations behind its publication. The moment it hit the Internet, it scanned as a proof of life for a princess who had become indefinitely invisible without much explanation, leaving a void that people filled with rampant speculation and conspiracy theories . The audience for the photograph was large, and they peered at it closely. Perhaps inevitably, they thought they saw strange things: not just touch-ups of hair or skin but serious tampering.

Amateur analysts should always tread lightly when it comes to digital photos, which are typically full of noise and junk. Once, many years ago, a snapshot of my cat wandered onto the Internet and became a lower-tier meme—“ Invisible Motocross ”—inspiring passionate discussion across an anonymous Venn diagram of cat-culture scholars and forensic-photography sleuths about how the distribution of light and shadow behind my cat and the way her furry outline cut against the background proved, without a doubt, that the photo was a fake. (My rebuttal: If I knew how to use Photoshop, I would have edited in a nicer living-room backdrop. That apartment was such a shithole!) Stare at any meaningful image for too long and you will eventually end up in the back yard with Lee Harvey Oswald , taking measuring tape to shadows, trying to strike that strange backward-leaning pose, looking like somebody’s patsy.

The Middleton-Windsor photograph , alas, was not an Invisible Motocross situation. What tears it is a spot not far below Kate’s collar—a seeming delineation between what appear to be two discrete images. This digital boundary cuts the zipper on Kate’s jacket in two and blurs the bottom half. It’s like a pattern mismatching at the seam of a poorly stitched garment, and, once you see it, you start seeing all the other torn and puckering seams in the image: the way Princess Charlotte’s wrist looks too big for her sleeve, which seems to be melting into her skirt; the way that strange snippets of hair fall on and blend into various shoulders. Soon, in an extraordinary and humiliating wave of repudiation, news agencies including the Associated Press, Agence France-Presse, Reuters, and Getty all issued kill notices for the picture, forbidding its distribution on their channels. “ AT CLOSER INSPECTION IT APPEARS THAT THE SOURCE HAS MANIPULATED THE IMAGE ,” the A.P.’s notice explained, going on to say that an unedited version of the photo would not be forthcoming. On TikTok, an impressively resourceful sleuth dug up video from a 2023 charity event, in which Kate and her children seemed to be in the same outfits that they wore in the supposedly new, post-surgery picture.

Damage control begat more reason for damage control. Despite the Royal Family’s famous dictum “Never complain, never explain,” an apology was issued: “Like many amateur photographers, I do occasionally experiment with editing. I wanted to express my apologies for any confusion the family photograph we shared yesterday caused.” The statement was signed “C,” for Catherine, even though William was the credited photographer, and thus ever so slightly more plausible as the Kensington Palace employee who is responsible for doing touch-ups on official photographs.

A furious Daily Mail editor declared that Kate had been “thrown under a bus” by Kensington Palace—forced to take the fall for a major institutional lapse: “I think it’s disgraceful, I think it’s very ungentlemanly of Prince William to put the onus on her. For goodness sake, he’s the one who took the photograph.” On social media, video circulated of an interview with Prince Harry, professional royal defector, talking about the family’s propensity for naming scapegoats in times of P.R. crisis. (As many have pointed out, it may be impossible to exaggerate the media tsunami that would have erupted if Meghan Markle, whom the U.K. press always cast as the Wicked Witch of the West against Kate’s diaphanous, do-no-wrong Glinda, had distributed a doctored photo of herself with Archie and Lilibet.)

At a certain point, the attempted crisis management began to look almost intentionally self-sabotaging. A grainy image emerged of William and Kate in the back seat of a car leaving Windsor Castle; Kate is turned away from the camera, in one-quarter profile. Almost immediately, a savvy royal watcher found a 2016 image of Kate, which appears to map onto the paparazzi snap with suggestive precision. The photographer who claimed credit for the car picture, which was syndicated through an agency called GoffPhotos, denied to the New York Post that any editing shenanigans had taken place. But the discovery of the older picture intensified the ghostliness of the new one, casting Kate, in her demure chignon and pillbox hat, as a gothic apparition that you can’t be sure you really see, like the lady in the lake in “ The Turn of the Screw ” or the woman in the doorway of the grand house of Tony Soprano’s afterlife. Suddenly there was a chill in the air, a shiver down the spine.

The most plausible explanation for Kate’s absence remains the simplest, and it is also the one that was announced in the first place, back in January: she is recovering from major surgery. What Kensington Palace did not disclose at that time was how hopelessly naïve it appears to be about technology, social media, and its global public’s sophisticated understanding of them both. As David Yelland, a former editor of the U.K. tabloid the Sun , said on a podcast he co-hosts, “I think this is a twentieth-century organization, maybe even a sixteenth-century organization, trying to play twenty-first-century games.” Some of their failings, however, are timeless. “The royal body exists to be looked at,” the novelist Hilary Mantel wrote in a controversial and brilliant 2013 essay for the London Review of Books . If Kate is not seen, she ceases to exist; she seems to die, and throws her public into a confused quasi-mourning that demands deft and elegant intercession. (There was a whole movie about this!) Nobody at any time, neither a subject of Elizabeth I nor a TikTok influencer in 2024, would ever be satisfied by a smudged glimpse of maybe-Kate’s ear and cheekbone—which is all that the GoffPhotos picture had to offer—as evidence of the royal body’s good health.

The rap on Kate was always that, despite her abundant beauty, charm, and high-heeled indefatigability—maybe in part because of it—she was boring, especially in contrast to Diana, her husband’s mother and eternal Princess of Wales, who possessed all of Kate’s gifts and more: vulnerability, unpredictability, a certain irresistible too-muchness. Mantel, in her London Review of Books essay, called Kate, not without empathy, “a shop-window mannequin, with no personality of her own.” Mantel went on, “She appears precision-made, machine-made, so different from Diana whose human awkwardness and emotional incontinence showed in her every gesture. Diana was capable of transforming herself from galumphing schoolgirl to ice queen, from wraith to Amazon. Kate seems capable of going from perfect bride to perfect mother, with no messy deviation.”

The time line of Diana’s fascinating transformations can be tracked in indelible, often appealingly imperfect images: the teen-age day-care worker unaware of the sun shining through her translucent skirt; the demure bride floating on plumes of taffeta; the doting young mother nuzzling her boys in casual photos taken en plein air; the supermodel in the revenge dress; the jet-setting divorcée getting papped on a playboy’s yacht. Kate could never achieve the iconic stature that Diana built from these images, and likely she never wanted to. (It is not terribly reductive to say that Diana died in the midst of doing what Kate is struggling to do now: deal with the press.) But, aside from her wedding to William, in 2011, the ongoing uproar over these recent photographs is the most captivating episode of Kate’s entire public career, and all because of a spectacularly failed attempt to present the perfect image. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

The repressive, authoritarian soul of “ Thomas the Tank Engine .”

Why the last snow on Earth may be red .

Harper Lee’s abandoned true-crime novel .

How the super-rich are preparing for doomsday .

What if a pill could give you all the benefits of a workout ?

A photographer’s college classmates, back then and now .

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Anthony Lane

By Anna Russell

By Justin Chang

By Rachel Syme

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

On The New Deal. (covering the CCC, CWA, NYA, PWA & WPA) Prepared by Janaki Srinivasan. Version of January 2012. Abramowitz, Mildred. 1970. Eleanor Roosevelt and Federal Responsibility and Responsiveness To Youth, The Negro and Others In Time Of Depression. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University. Abrams, James. 1988.

The First New Deal (1933-1934) At the time of Roosevelt's inauguration on March 4, 1933 the nation had been spiraling downward into the worst economic crisis in its history. Industrial output was only half of what it had been three years earlier, the stock market had recovered only slightly from its catastrophic losses, and unemployment stood ...

with New Deal scholarship. Specifically, this thesis addresses and contributes to the body of works relating to the Civilian Conservation Corps. Much of these works highlight the nature of the program from the ground up—that is, from the perspective of the CCC enrollee—or from the top down in examining issues of executive leadership

Defining the "New Deal". On July 2, 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) accepted the Democratic Party's nomination for president and pledged himself to a "new deal for the American people." 1 In so doing, he gave a name not only to a set of domestic policies implemented by his administration in response to the crisis of the Great ...

Full Circle: the New Deal and the Great Recession. An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History. Donald Lewis Roberts. Under the mentorship of Dr. Craig Roell. Abstract: In this paper I will show how the mindset of liberalism has evolved since the Great Depression.

The New Deal, Katznelson argues, could have created a state system in which business, labor, and government might have cooperatively shared in planning for the common good. ... The thesis has some merit: many of Roosevelt's advisers, and the president himself in some moods, entertained such prospects; and as Katznelson says, in the later 1930s ...

the New Deal failed to overcome the Depression and World War II did was the. simple fact that the war made intellectually conceivable and politically possible deficit spending on a level that was neither dreamed nor attempted before the. war came. The biggest New Deal deficit was some $4.2 billion in 1936, largely.

Certain New Deal laws were declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court on the grounds that neither commerce nor taxing provisions of the Constitution granted the federal government authority to regulate industry or to undertake social and economic reform. Roosevelt differed with the Court and in 1937 sought to pack the court (or expand ...

African, and World History through thesis-driven, concise volumes designed for survey and upper-division undergraduate history courses. The books contain an introduction that acquaints readers ... My fascination with the New Deal and its response to the Great Depression began in earnest twenty-one years ago when I started graduate study at the ...

The New Deal programs that built on existing national government programs included providing funds for highways and roads; reclamation and irrigation; flood control and improved navigation; benefits to veterans; building of post offices and federal buildings; mortgage loans

New Deal Work Programs In Jefferson County, Texas: The Civilian Conservation Corps At Tyrell Park. M.A. thesis, Beaumont, Texas: Lamar University. Vinson, Denny, 1939. The Effectiveness Of The Conservation Of Human Beings and Of Soil By The CCC Camp In Denton, Texas. M.S. thesis, North Texas State College. Walters, Marion. 1996.

New Deal, domestic program of the administration of U.S. Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) between 1933 and 1939, which took action to bring about immediate economic relief as well as reforms in industry, agriculture, finance, waterpower, labour, and housing, vastly increasing the scope of the federal government's activities. The term was taken from Roosevelt's speech accepting the ...

Chicago, South Deering and Pullman" (M.A. thesis, University of Chicago, 1926), p. 114. (Courtesy of the Southeast Chicago Collection, Urban Culture and Documentary Program, Columbia College, Chicago.) 27 ... Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939: Second Edition Lizabeth Cohen Frontmatter More informatio n.

rights policies of the New Deal but almost entirely in the jobs Roosevelt created for Afro-Americans. Explicitly rejecting Harvard Sitkoff's civil rights thesis in his A New Deal for Blacks (1978), Weiss states crisply, "That argu-ment is at odds with the one developed in this book" (p. xv). To this reader,

Capron, Elisabeth. 1939. The Effects Of The Works Progress Administration Labor Wage On The Attitudes and Adjustments Of Forty-five Families: A Dissertation Based Upon An Investigation At The Department Of Public Relief In collaboration with the local Works Progress Administration office, Cincinnati, Ohio. M.S.S. thesis, Smith College School ...

Now, to go back to my major thesis - the thesis of the longer view. Before we enter into courses of deep-seated change and of the new deal, I would like you to consider what the results of this American system have been during the last 30 years - that is, a single generation. ... That is another mark of the character of the new deal and the ...

New Deal for the American People . On March 4, 1933, during the bleakest days of the Great Depression, newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his first inaugural address before ...

The New Deal and Racial Discrimination. African Americans supported President Hoover by a two-to-one margin in the 1932 election. While most African Americans still associated the Grand Old Party with Abraham Lincoln and civil rights, Hoover had an uneven record on racial justice. 16 He made black equality a plank in his campaign platform and appointed black men to serve in patronage positions ...

The New Deal Roosevelt had promised the American people began to take shape immediately after his inauguration in March 1933. Based on the assumption that the power of the federal government was needed to get the country out of the depression, the first days of Roosevelt's administration saw the passage of banking reform laws, emergency relief ...

Introduction. After the inauguration in 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt urgently took the course for the new deal, that was aimed to overcome the consequences of the Great Depression. It was the series of economic and social programs that were planned for the period 1933 to 1936. The First New Deal, which took place in 1933, included the banking ...

Introduction. Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) was nominated as the President of United States in the summer of 1932. Roosevelt, in his acceptance speech, addressed different problems faced by the American people due to the Great Depression. He pledged to offer a new deal to resolve the grave scenario. Roosevelt won by a huge margin.

New Deal Thesis. 1100 Words5 Pages. Brief Background and Aims of the Thesis The term "Green New Deal" has been used by a number of policy documents created in response the global financial crisis and economic recession since 2007/2008. This title openly draws upon Franklin Roosevelt's "New Deal," put in place to fight against the economic ...

It was a series of social liberal programs applied in the United States in 1933-1938 in response to the Great Depression. The New Deal was focused on three main principles: relief, recovery, and reform. [footnoteRef:1] They promised to bring the country to prosperity and economically stable future.

The New Deal's War on the Bill of Rights: The Untold Story of FDR's Concentration Camps, Censorship, and Mass Surveillance, by David T. Beito (Independent Institute, 404 pp., $20.48). Taming the Street: The Old Guard, the New Deal, and FDR's Fight to Regulate American Capitalism, by Diana B. Henriques (Random House, 464 pp., $20.02). The New Deal reshaped American life.

A grainy image emerged of William and Kate in the back seat of a car leaving Windsor Castle; Kate is turned away from the camera, in one-quarter profile. Almost immediately, a savvy royal watcher ...

BuzzBallz was founded in 2009 as a result of Merrilee Kick's master's degree thesis project. It has since grown to employ more than 650 people with a 2021 revenue of nearly $113 million, according ...