The turning point: Why we must transform education now

Global warming. Accelerated digital revolution. Growing inequalities. Democratic backsliding. Loss of biodiversity. Devastating pandemics. And the list goes on. These are just some of the most pressing challenges that we are facing today in our interconnected world.

The diagnosis is clear: Our current global education system is failing to address these alarming challenges and provide quality learning for everyone throughout life. We know that education today is not fulfilling its promise to help us shape peaceful, just, and sustainable societies. These findings were detailed in UNESCO’s Futures of Education Report in November 2021 which called for a new social contract for education.

That is why it has never been more crucial to reimagine the way we learn, what we learn and how we learn. The turning point is now. It’s time to transform education. How do we make that happen?

Here’s what you need to know.

Why do we need to transform education?

The current state of the world calls for a major transformation in education to repair past injustices and enhance our capacity to act together for a more sustainable and just future. We must ensure the right to lifelong learning by providing all learners - of all ages in all contexts - the knowledge and skills they need to realize their full potential and live with dignity. Education can no longer be limited to a single period of one’s lifetime. Everyone, starting with the most marginalized and disadvantaged in our societies, must be entitled to learning opportunities throughout life both for employment and personal agency. A new social contract for education must unite us around collective endeavours and provide the knowledge and innovation needed to shape a better world anchored in social, economic, and environmental justice.

What are the key areas that need to be transformed?

- Inclusive, equitable, safe and healthy schools

Education is in crisis. High rates of poverty, exclusion and gender inequality continue to hold millions back from learning. Moreover, COVID-19 further exposed the inequities in education access and quality, and violence, armed conflict, disasters and reversal of women’s rights have increased insecurity. Inclusive, transformative education must ensure that all learners have unhindered access to and participation in education, that they are safe and healthy, free from violence and discrimination, and are supported with comprehensive care services within school settings. Transforming education requires a significant increase in investment in quality education, a strong foundation in comprehensive early childhood development and education, and must be underpinned by strong political commitment, sound planning, and a robust evidence base.

- Learning and skills for life, work and sustainable development

There is a crisis in foundational learning, of literacy and numeracy skills among young learners. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, learning poverty has increased by a third in low- and middle-income countries, with an estimated 70% of 10-year-olds unable to understand a simple written text. Children with disabilities are 42% less likely to have foundational reading and numeracy skills compared to their peers. More than 771 million people still lack basic literacy skills, two-thirds of whom are women. Transforming education means empowering learners with knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to be resilient, adaptable and prepared for the uncertain future while contributing to human and planetary well-being and sustainable development. To do so, there must be emphasis on foundational learning for basic literacy and numeracy; education for sustainable development, which encompasses environmental and climate change education; and skills for employment and entrepreneurship.

- Teachers, teaching and the teaching profession

Teachers are essential for achieving learning outcomes, and for achieving SDG 4 and the transformation of education. But teachers and education personnel are confronted by four major challenges: Teacher shortages; lack of professional development opportunities; low status and working conditions; and lack of capacity to develop teacher leadership, autonomy and innovation. Accelerating progress toward SDG 4 and transforming education require that there is an adequate number of teachers to meet learners’ needs, and all education personnel are trained, motivated, and supported. This can only be possible when education is adequately funded, and policies recognize and support the teaching profession, to improve their status and working conditions.

- Digital learning and transformation

The COVID-19 crisis drove unprecedented innovations in remote learning through harnessing digital technologies. At the same time, the digital divide excluded many from learning, with nearly one-third of school-age children (463 million) without access to distance learning. These inequities in access meant some groups, such as young women and girls, were left out of learning opportunities. Digital transformation requires harnessing technology as part of larger systemic efforts to transform education, making it more inclusive, equitable, effective, relevant, and sustainable. Investments and action in digital learning should be guided by the three core principles: Center the most marginalized; Free, high-quality digital education content; and Pedagogical innovation and change.

- Financing of education

While global education spending has grown overall, it has been thwarted by high population growth, the surmounting costs of managing education during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the diversion of aid to other emergencies, leaving a massive global education financial gap amounting to US$ 148 billion annually. In this context, the first step toward transformation is to urge funders to redirect resources back to education to close the funding gap. Following that, countries must have significantly increased and sustainable financing for achieving SDG 4 and that these resources must be equitably and effectively allocated and monitored. Addressing the gaps in education financing requires policy actions in three key areas: Mobilizing more resources, especially domestic; increasing efficiency and equity of allocations and expenditures; and improving education financing data. Finally, determining which areas needs to be financed, and how, will be informed by recommendations from each of the other four action tracks .

What is the Transforming Education Summit?

UNESCO is hosting the Transforming Education Pre-Summit on 28-30 June 2022, a meeting of over 140 Ministers of Education, as well as policy and business leaders and youth activists, who are coming together to build a roadmap to transform education globally. This meeting is a precursor to the Transforming Education Summit to be held on 19 September 2022 at the UN General Assembly in New York. This high-level summit is convened by the UN Secretary General to radically change our approach to education systems. Focusing on 5 key areas of transformation, the meeting seeks to mobilize political ambition, action, solutions and solidarity to transform education: to take stock of efforts to recover pandemic-related learning losses; to reimagine education systems for the world of today and tomorrow; and to revitalize national and global efforts to achieve SDG-4.

- More on the Transforming Education Summit

- More on the Pre-Summit

Related items

- Future of education

- SDG: SDG 4 - Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

This article is related to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals .

Other recent news

Does PowerPoint Improve Student Learning?

The Rationality of Science

PowerPoint is used in countless classrooms. For many teachers and instructors, PowerPoint is a staple in their programs. Electronic presentation software—most notably PowerPoint—has had a big impact on education. I use PowerPoint and other strategies when teaching. There are advocates and critics of PowerPoint. With the use of PowerPoint being so prevalent, it is important to consider what qualities make it a strong educational tool. Informal and formal surveys indicate most students report that they prefer PowerPoint to more traditional classroom lectures that include whiteboard methods, overhead transparencies, handouts, and writing on the chalkboard. Does the preference for PowerPoint mean teachers should rely mostly on PowerPoint for teaching? Does the use of PowerPoint have a positive impact on student learning?

We can ask instructors their opinions on electronic presentation software and come up with a range of answers. The answers can be used to form questions and help in guiding future research. However, the answers shouldn’t be categorized as evidence. The instructors are all subject to conscious and unconscious biases. There are many uncontrolled factors occurring during the learning process, so attributing an outcome to a single factor is problematic. Let’s look at what science says about PowerPoint and learning.

The Science Says

A meta-analysis (which combines the results of similar studies) of forty-eight studies was conducted to determine if students learn more when taught the same information using PowerPoint compared to a more traditional instruction (Baker et al. 2018). Results showed that on average, there was no difference in students’ learning based on the type of instruction they received. However, K-12 students’ learning increased with PowerPoint instruction, but this effect did not occur for college students. The researchers concluded focus shouldn’t be on strictly comparing the absence or presence of PowerPoint but should be focused on how instructors can use features of PowerPoint to improve student learning.

Some researchers suggest that using PowerPoint can affect subjective student perceptions of learning; they may report they learned more even when testing shows they didn’t. Apperson et al. (2006) collected data from college students in ten different classes across four academic areas. Courses were taught using the chalkboard and transparencies one semester and the same course using PowerPoint the following semester. The same textbook, exams, and lecture materials were presented for both semesters. Students taking PowerPoint courses are more likely to report better focus on course content, report the instructor did a good job at keeping their attention and that PowerPoint improves student learning. Overall, they rated the instructor more positively and were likely to say they would take another course from the same instructor. Students felt that the class was better and more beneficial overall, but there was no significant difference in average grades between those taking PowerPoint and non-PowerPoint classes.

In another study, researchers compared learning between psychology students in classes using either overhead transparencies or PowerPoint (Susskind 2008) The instructor taught one class using a traditional lecture format that included overhead transparencies; the other class was taught using computerized PowerPoint. Researchers found no difference in exam scores based on whether the information was presented on overhead transparencies or PowerPoint. However, students preferred the PowerPoint class; they reported the instructor was more effective, that they took better notes, and the material was easier to understand. It is common for students to feel like they have learned more and enjoy the course more when using PowerPoint even if their grades do not reflect this.

In another study, three methods of instruction in addition to lecture were compared: chalkboard and lecture, overhead transparencies and lecture, presentation software and lecture (Beets and Lobinger 2001). The same content was presented in each course and presented by the same instructor. The results indicated no significant difference in quiz or exam scores. However, in a survey conducted at the end of the course, students reported they preferred the presentation software. Most research shows nonsignificant differences in learning between those being exposed to PowerPoint and those using more traditional methods. However, there is some research showing slight differences in scores between students who are taught with PowerPoint versus other methods of teaching.

In one study, researchers examined the effect of using different visual and auditory features of the software presentation on student learning. Students were exposed to overhead transparencies, PowerPoint slides containing only text, and PowerPoint slides that included pictures, sound effects, and variations in text characteristics (Bartsch and Cobern 2003). The results indicated there was no difference between transparency and text-only PowerPoints, but students scored about 10 percent lower on quizzes assessing content presented with the elaborate PowerPoint slides. The findings from this study bring up an important topic not often discussed: PowerPoints vary in their design, and this variation can have effects on learning. Some PowerPoints may be designed in a manner that leads students to focus too much on graphics or other features that may take away from a focus on the main points.

Some studies have found positive effects associated with PowerPoint instruction. Erwin and Rieppi (2000) studied college students distributed over two sections each of abnormal psychology, statistics, and a development course. In one section of each course an instructor used PowerPoint and in the other section the instructor used non-PowerPoint (various modes with no restrictions on which technology was used were also taught). PowerPoint sections scored higher on the exams for all three classes. Critics point out this study consisted of methodology flaws: there was no standardization of content in the courses, course were taught by six different instructors who developed their own content, teachers were aware of the varying conditions (which could influence expectancy effects), and the PowerPoint sections included an interactive component that was not included with the non-PowerPoint sections. Any of these uncontrolled factors could influence the outcome. Other studies have also found small PowerPoint effects (positive impact of PowerPoint versus other modes), but critics are fast to point out the effects are usually small and the research methods are generally flawed.

Science says there is little difference between learning outcomes in those receiving PowerPoint instruction and those receiving other types of instruction. There is research showing positive and negative outcomes as a result of being exposed to PowerPoint. PowerPoints can be used alongside other modes of teaching.

PowerPoint Design

In general, students prefer PowerPoints to other modes of teaching, and they feel as if they are learning more; a positive experience for students is important. Positive experiences can lead to positive expectations, which can benefit students.

It is important to distinguish good from bad PowerPoints. Although standard rules for what makes a good PowerPoint or bad PowerPoint are lacking, there are some general guidelines that are recommended. Slides that contain key information should stand out; they could be bold or consist of a different font or a different graphic. Slides shouldn’t consist of too much information; bullet points work but the information doesn’t necessarily have to be presented as bullet points (information should be easy to read and not excessive). PowerPoints should present information that can relate to what the learner already knows; this allows strong memory connections.

How can learners make the best use of PowerPoint? If you have access to PowerPoint, review the PowerPoint ahead of time. A lot of instructors place the PowerPoints online, so printing the slides and bringing them to class is recommended. A big advantage of having a hard copy of the slides is you can take additional notes; you don’t have to spend all your time writing what is on the slides.

Research on the effectiveness of PowerPoint should continue to compare PowerPoint to different teaching strategies. Researchers should strive to develop standard guidelines for designing effective PowerPoints. Current research doesn’t often distinguish between good and bad design, and these differences are important to developing models that can maximize the benefits of PowerPoint.

Apperson, J.M., et al. 2006. The impact of presentation graphics on students’ experience in the classroom. Computers and Education 47: 116–128.

Baker, J.P. et al. 2018. Does teaching with PowerPoint increase students’ learning? A meta-analysis. Computers & Education 126: 376–387.

Bartsch, R.A., and K.M. Cobern. 2003. Effectiveness of PowerPoint presentations in lectures. Computers & Education 41: 77–86.

Beets, S.D., and P.G. Lobinger. 2001. Pedagogical techniques: Student performance and preferences. Journal of Education for Business 76: 231–235.

Erwin, T.D., and R. Rieppi. 2000. Comparing multimedia and traditional approaches in undergraduate psychology classes. Teaching of Psychology 26: 58–61.

Susskind, J.E. 2008. Limits of PowerPoint’s power: Enhancing students’ self-efficacy and attitudes but not their behavior. Computers & Education 50: 1228–1239.

- Current Students

- Faculty / Staff

- Paying for College

- Alumni Services

- Partnerships

- Program Finder

- Affordable, Flexible, Accessible

- Distance Education

- All Online Courses & Degrees

- Baccalaureate Online

- Graduate Online

- Start Dates

- Admissions, Costs & Aid

- Faculty and Contacts

- Academic and Career Support

- Student Testimonials

- Distance Education Advantage

- About Hybrid Learning

- Hybrid Learning Degrees

- Admissions Requirements

- Top Destination Courses

- Student Life

- Academic Support

- Academic Calendar

- Faculty & Contacts

- Technical Institute for Environmental Professions

- Term Calendar

- Sustainable Ventures

- Careers & Outcomes

- About Unity

- Office of the President

- Announcing Our Evolution

- Sustainable Achievements & Initiatives

- Reinventing College

- Extended Reality (XR)

- Commencement

- Give to Unity Environmental University

- Institutional Communications

- Unity Environmental University News

Home / News / Why Is Education Important? The Power Of An Educated Society

Why Is Education Important? The Power Of An Educated Society

Looking for an answer to the question of why is education important? We address this query with a focus on how education can transform society through the way we interact with our environment.

Whether you are a student, a parent, or someone who values educational attainment, you may be wondering how education can provide quality life to a society beyond the obvious answer of acquiring knowledge and economic growth. Continue reading as we discuss the importance of education not just for individuals but for society as a whole.

Harness the power of education to build a more sustainable modern society with a degree from Unity Environmental University .

How Education Is Power: The Importance Of Education In Society

Why is education so important? Nelson Mandela famously said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” An educated society is better equipped to tackle the challenges that face modern America, including:

- Climate change

- Social justice

- Economic inequality

Education is not just about learning to read and do math operations. Of course, gaining knowledge and practical skills is part of it, but education is also about values and critical thinking. It’s about finding our place in society in a meaningful way.

Environmental Stewardship

A study from 2022 found that people who belong to an environmental stewardship organization, such as the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics, are likely to have a higher education level than those who do not. This suggests that quality education can foster a sense of responsibility towards the environment.

With the effects of climate change becoming increasingly alarming, this particular importance of education is vital to the health, safety, and longevity of our society. Higher learning institutions can further encourage environmental stewardship by adopting a framework of sustainability science .

The Economic Benefits Of Education

Higher education can lead to better job opportunities and higher income. On average, a person with a bachelor’s degree will make $765,000 more in their lifetime than someone with no degree. Even with the rising costs of tuition, investment in higher education pays off in the long run. In 2020, the return on investment (ROI) for a college degree was estimated to be 13.5% to 35.9% .

Green jobs like environmental science technicians and solar panel installers have high demand projections for the next decade. Therefore, degrees that will prepare you for one of these careers will likely yield a high ROI. And, many of these jobs only require an associate’s degree or certificate , which means lower overall education costs.

Unity helps students maximize their ROI with real-world experience in the field as an integral part of every degree program.

10 Reasons Why School Is Important

Education is not just an individual pursuit but also a societal one. In compiling these reasons, we focused on the question, “How does education benefit society?” Overall, higher education has the power to transform:

- Individuals’ sense of self

- Interpersonal relationships

- Social communities

- Professional communities

Cognitive Development

Neuroscience research has proven that the brain is a muscle that can retain its neuroplasticity throughout life. However, like other muscles, it must receive continual exercise to remain strong. Higher education allows people of any age to improve their higher-level cognitive abilities like problem-solving and decision-making. This can make many parts of life feel more manageable and help society run smoothly.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence is key to workplace success. Studies show that people with emotional intelligence exhibit more:

- Self-awareness

- Willingness to try new things

- Innovative thinking

- Active listening

- Collaboration skills

- Problem-solving abilities

By attending higher education institutions that value these soft skills, students can improve their emotional intelligence as part of their career development in college.

Technological Literacy

Many careers in today’s job market use advanced technology. To prepare for these jobs, young people likely won’t have access to these technologies to practice on their own. That’s part of why so many STEM career paths require degrees. It’s essential to gain technical knowledge and skills through a certified program to safely use certain technologies. And, educated scientists are more likely to make new technological discoveries .

Cultural Awareness

Education exposes individuals to different cultures and perspectives. Being around people who are different has the powerful ability to foster acceptance. Acceptance benefits society as a whole. It increases innovation and empathy.

College also gives students an opportunity to practice feeling comfortable in situations where there are people of different races, genders, sexualities, and abilities. Students can gain an understanding of how to act respectfully among different types of people, which is an important skill for the workplace. This will only become more vital as our world continues to become more globalized.

Ethical and Moral Development

Another reason why school is important is that it promotes ethical and moral development. Many schools require students to take an ethics course in their general education curriculum. However, schools can also encourage character development throughout their programs by using effective pedagogical strategies including:

- Class debates and discussions

- Historical case studies

- Group projects

Unity’s distance learning programs include an ethical decision-making class in our core curriculum.

Ready To Learn More About Unity Environmental University?

Communication Skills

Effective written and verbal communication skills are key for personal and professional success. Higher education programs usually include at least one communication course in their general education requirements. Often the focus in these classes is on writing skills, but students can also use college as an opportunity to hone their presentation and public speaking skills. Courses such as Multimedia Communication for Environmental Professionals provide many opportunities for this.

Civic Engagement

According to a Gallup survey , people with higher education degrees are:

- More likely to participate in civic activities such as voting and volunteering

- Less likely to commit crimes

- More likely to get involved in their local communities

All these individual acts add up to make a big difference in society. An educated electorate is less likely to be swayed by unethical politicians and, instead, make choices that benefit themselves and their community. Because they are more involved, they are also more likely to hold elected officials accountable.

Financial Stability

The right degree can significantly expand your career opportunities and improve your long-term earning potential. Not all degrees provide the same level of financial stability, so it’s important to research expected salary offers after graduation and job demand outlook predictions for your desired field. Consider the return on investment for a degree from an affordable private school such as Unity Environmental University .

Environmental Awareness

We have already discussed why education is important for environmental stewardship. Education can also lead to better environmental practices in the business world. By building empathy through character education and ethics courses, institutions can train future business leaders to emphasize human rights and sustainability over profits. All types and sizes of businesses can incorporate sustainable practices, but awareness of the issues and solutions is the first step.

Lifelong Learning

The reasons why education is important discussed so far focus on institutional education. However, education can happen anywhere. Attending a university that values all kinds of learning will set students up with the foundation to become lifelong learners. Research demonstrates that lifelong learners tend to be healthier and more fulfilled throughout their lives. When societies emphasize the importance of education, they can boost their overall prosperity.

The Role Of Unity Environmental University In Society

Environmentally conscious education is extremely valuable and should be accessible to all. Unity Environmental University offers tuition prices that are comparable to public universities, and financial aid is available to those who qualify. Courses last five weeks so that students can focus on only one class at a time. This ensures all learners are set up for academic success.

Unity believes in supporting students holistically to maximize the power of education. This includes mental health services, experiential learning opportunities , and job placement assistance . Students in our hybrid programs can take classes at several field stations throughout Maine and enjoy the beautiful nature surrounding the campus for outdoor recreation.

Sustainable Initiatives

Some highlights from Unity Environmental University’s many sustainable initiatives:

- All programs include at least one sustainability learning outcome

- All research courses are focused on sustainability research

- Reduced building energy use by 25% across campus

- 100% of food waste is recycled into energy

- Campus features a net-zero LEED Platinum-certified classroom/office building

While many schools value sustainability, Unity stands out because everything we do is about sustainability. We also recognize our responsibility to model how a sustainable business can operate in a manner that’s fiscally viable and socially responsible.

Make An Impact At Unity Environmental University

While the phrase ‘education is power’ may sound cliche, it is also resoundingly true. Higher education has the power to transform individuals and societies. Unity Environmental University understands its power to make a positive impact on the world. That’s why we were the first university to divest from fossil fuels.

This year, we celebrated our largest incoming class ever , showing that students want an education system that aligns with their values. In addition to our commitment to sustainability, we offer flexibility to students with start dates all year round for our online degree programs .

Start Your Journey

Looking for Answers

Get More Info

© Unity Environmental University 2024. “America’s Environmental University.™”

Privacy Overview

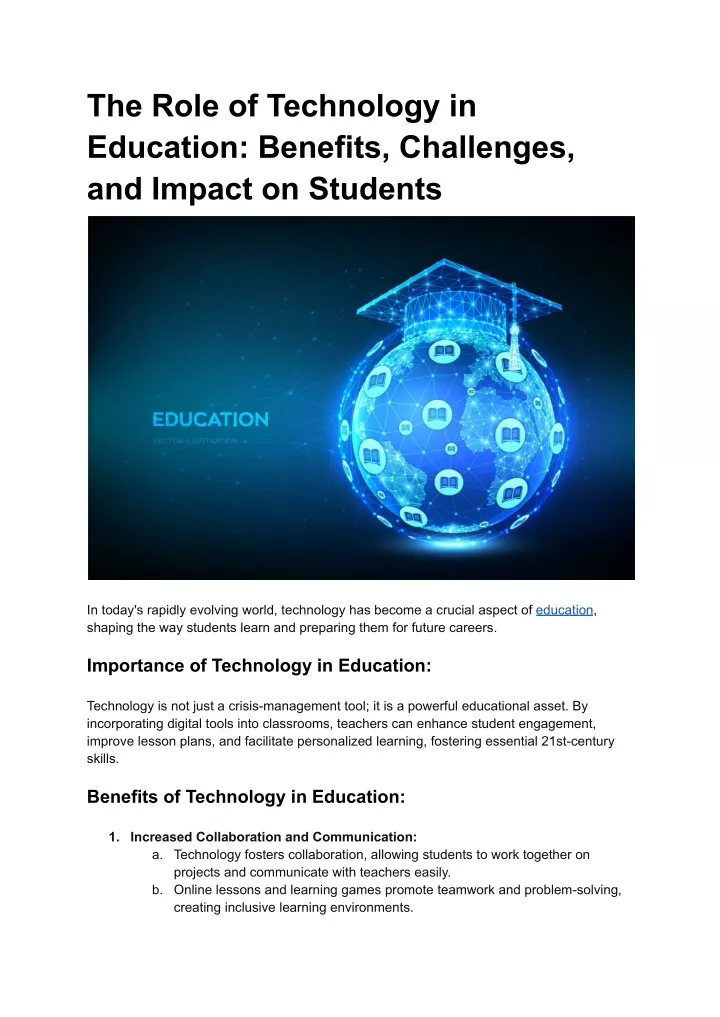

How technology is reinventing education

Stanford Graduate School of Education Dean Dan Schwartz and other education scholars weigh in on what's next for some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom.

Image credit: Claire Scully

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

Advertisement

PowerPoint Presentation Technology and the Dynamics of Teaching

- Open access

- Published: 02 August 2006

- Volume 31 , pages 147–160, ( 2006 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Russell J. Craig 1 &

- Joel H. Amernic 2

73k Accesses

89 Citations

100 Altmetric

15 Mentions

Explore all metrics

This article presents a wide-ranging analysis of the use of PowerPoint technology in higher education. It addresses four overlapping issues. Has PowerPoint led to more effective learning? What impact has PowerPoint had on the dynamics of classrooms? What are some important aspects of the culture that accompanies PowerPoint? How has PowerPoint affected orality, visuality and literacy? The purpose of our article is to stimulate beneficial conversations about a prevalent educational software technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Patterns of PowerPoint Use in Higher Education: a Comparison between the Natural, Medical, and Social Sciences

David Chávez Herting, Ramón Cladellas Pros & Antoni Castelló Tarrida

Next Steps: Toward a Relational Mode of Thinking for Educational Technology

A Synoptic View

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This article focuses on PowerPoint, a powerful and ubiquitous communications technology and aid to teaching and business presentations. In 2002, it was estimated that more than 400 million copies of PowerPoint were in circulation and that “somewhere between 20 and 30 million PowerPoint-based presentations are given around the globe each day” (Simons, 2005 ). Those numbers seem likely to have grown exponentially since then. Indeed, Parker ( 2001 ) alleged that to “appear at a meeting without PowerPoint would be unwelcome and vaguely pretentious, like wearing no shoes” (pdf version, p. 2). Further, the use of PowerPoint is so widespread in higher education institutions that for a faculty member to refrain from using PowerPoint is “sometimes seen as a mark of seniority and privilege, like egg on one’s tie” (Parker, 2001 , p. 6, citing a conversation with Stanford University Professor Clifford Nass).

PowerPoint has a dubious reputation. It has been described as “the Viagra of the spoken word ... [and] a wonder pill for flabby lectures” (van Jole, 2000 ); and as something that “... turns clear thinking adults into addled-headed boobs” (Shwom & Keller, 2003 , p. 3). But, if PowerPoint is a drug, Tufte ( 2003a ) argued it ought to be subject to a worldwide product recall, for it had “frequent, serious side effects: it induced stupidity, turned everyone into bores, wasted time, and downgraded the quality and credibility of communication” (para. 1).

PowerPoint technology has become a punching bag that Parker ( 2001 ) alleged has turned its users “into bullet-point dandies” (p. 1). It has been criticized for elevating form over content (Tufte, 2003a , b ); assigned part of the cause for “a general decline in public speaking” (Nunberg, 1999 , p. 330); denounced by academics and by CEOs ... for causing detrimental effects on “dialogue, interaction, and thoughtful consideration of ideas” (Cyphert, 2004 , p. 80); bemoaned as a facilitator of presentations that are “often tediously long and more annoying than Microsoft’s animated paperclip” (Goldkorn, 2004 , para. 4); and accused of “replacing clear thought with unnecessary animations, serious ideas with ten-word bullet points, substance with tacky, confusing style” (Coursey, 2003 , para. 2). Although PowerPoint promises much in terms of delivering content efficiently and offering attractive and dynamic presentations, some critics, such as Stewart ( 2001 ), allege that a frequent outcome is a vacuous monotony.

The preceding critical characterizations of PowerPoint might give the misleading impression that we are about to engage in a harangue of the type: “PowerPoint bad ... non-PowerPoint good.” However, such is not the case. We simply want to go beyond the content of the usual clichéd fare of literature on PowerPoint. This is preponderantly of three major types. First, is the literature which provides technical advice on how to prepare PowerPoint presentations (e.g., Coursey, 2003 ; Jones, 2003 ; Shwom & Keller, 2003 ). Second, is literature which outlines the advantages and disadvantages of PowerPoint. Much of this is in the form of PowerPoint presentations that are accessible through keyword search using Google , such as Bostock ( 2005 )—although some appears in scholarly journals such as Jones ( 2003 ). Third, is literature which takes a titillating swipe at the ostensible evils of PowerPoint or provides an unapologetically jaundiced account of its unsurpassable virtues (e.g., Nunberg, 1999 ; Stewart, 2001 ).

It is our intent to delve more deeply into four matters that deserve reflecting upon by educators and business seminar presenters. We seek to highlight some subtle but important issues that accompany the PowerPoint phenomenon. In doing so, we invoke a wide range of scholarly literature drawn from a variety of disciplines and an array of business periodicals and website newsletters. We address four overlapping issues. First, we review scholarly literature that examines the effectiveness of PowerPoint. Second, we explore how PowerPoint presentations affect the dynamics of pedagogical settings and the general relationship between presenter and presentees. Third, we analyse important aspects of the culture that attaches to PowerPoint technology. Finally, we explore PowerPoint-related issues of visuality, orality and literacy.

This article does not offer a broadly conceived exploration of McLuhan's thesis that “the medium is the message” (McLuhan & Fiore, 1967 ). We do not dwell upon Innis's ( 1991 ) ideas regarding the social nature of new technologies or upon semiotics in order to conceive PowerPoint as another dominating, socially forceful technological mediator of teaching. Although we do not focus on cataloguing how to design more effective PowerPoint slides, we draw attention to the failure of many PowerPoint presenters to ignore fundamental rhetorical principles; and we offer some advice on that matter. We do not engage in what Shwom and Keller ( 2003 ) referred to as “victimology”; that is, to make “PowerPoint the villain that oppresses its users, and almost by default absolve the presenter from taking any personal responsibility for providing significant content and communicating that content clearly” (p.15).

In the past three decades there has been a decisive shift in the media that have been used to communicate messages in educational settings. We have gone from the era of “chalk-and-talk” and occasional flip-charts to overhead transparencies and to PowerPoint slides. And, consistent with Warnick ( 2002 ), we feel it is important to recognize that any “new forms of communicating call for new ways of thinking about communication processes” (p. 264). However, it is important, as well, that we do not become “zealous ... one-eyed prophets who see only what new technologies can do and are incapable of imagining what they will undo ” [italics in original] and that we offer “a dissenting voice ... to moderate the din made by the enthusiastic [technophile] multitudes” (Postman, 1993 , p. 5).

In a sense, we are somewhat akin to Postman's “technological resistance fighter [who] maintains an epistemological and psychic distance from any technology, so that it always appears somewhat strange, never inevitable, never natural” (Postman, 1993 , pp.183–185). We are mindful of the implicit, perhaps largely unnoticed, alteration in “human attention-structures” (Lanham, 1993 ) that pervasive new technologies such as PowerPoint (and its allied information technology and Internet paraphernalia) bring with them. And, of course, as academics we are alert to our obligation to be “disturbers of the peace” (Passmore, 1967 , p. 203) and to “be somewhat reflexive about [our] use of tools, and thus not sound like Microsoft advertising executives” (Rose, 2004 , p. 797).

Our discussion is directed to providing a much-needed tempering of the widespread enthusiasm and excitement for PowerPoint while avoiding a seemingly reflexive anti-technology reaction. We seek to engender a clearer appreciation of whether PowerPoint is a beneficial and efficient educational medium by heightening awareness that the technology of PowerPoint is not an “unparalleled conduit of pedagogically related excellence” and that we need an alternative “‘attention structure’ that does not reify” PowerPoint (Amernic & Craig, 1999 , p. 437).

Is PowerPoint Effective?

In this section we review the limited empirical evidence on whether or not PowerPoint presentations are effective in enriching student learning. However, we refrain from consideration of such core ideas as critical thinking (Nelson, 1994 ), the university's role in the communication of imagination (Whitehead, 1957/[1929] , p. 97), and learning paradigms for undergraduate education (Barr & Tagg, 1995 ). It seems important to review the effectiveness of PowerPoint given its widespread and largely uncritical acceptance, particularly in higher education institutions. This is because, conceivably, PowerPoint might simply lead to a professor's “improvement and/or modernization of their performance in the classroom” (Szabo & Hastings, 2000 , p. 176) without any significant effects on student learning.

Given the widespread adoption of PowerPoint, the small number of authoritative studies of its effectiveness ( n < 20) is surprising. Generally, the available studies lack substance and internal and external validity and adopt rather constrained characterizations of the concept effectiveness . Most have been conducted in the United Kingdom and the U.S. and involve one-site, cross-sectional analyses of small classes that have been taught by the principal researcher (see, for example, Bartsch & Cobern, 2003 ; and the studies reviewed by Szabo & Hastings, 2000 , pp. 176–177). Typically, studies are conducted of classes that have been partitioned into two groups—one taught using lectures and PowerPoint and the other taught using lectures and overhead transparencies. Student attitude responses are gathered usually by means of in-class questionnaire survey methods and need to be scrutinized carefully for unintended bias.

Other studies are based simply on selective reporting of student anecdotes. Some have a self-indulgent quality of “ Hey, look at me, I’m an innovator, and my students like what I am doing .” Others are superficial recollections of instructor experience in using PowerPoint (e.g., Parks, 1999 ). Many studies of student attitudes were conducted before PowerPoint became an ingrained, almost compulsory feature of university lectures. It would not be surprising if many reported results were influenced by a now defunct “novelty factor.” With the passage of time and with heightened exposure to PowerPoint, our recent conversations with students suggest they are now more likely to respond to PowerPoint with an air of resigned, nonchalant ennui.

In the main, the results reported in scholarly journal articles indicate that students like to be taught using PowerPoint (perhaps because of its novelty and the availability of printed handouts of PowerPoint slides) and think that PowerPoint presentations are entertaining, enhance clarity, and aid recall of subject matter. There is little consistent evidence, however, to show that teaching with PowerPoint leads to significantly better learning and significantly better grades than teaching by more conventional methods. A majority of studies shows that use of PowerPoint is not associated with a significant improvement in student grades. For example, Rankin and Hoaas ( 2001 ) examined the effect of PowerPoint presentations on student grades in four classes of students in an introductory economics course taught by one instructor, at one institution, in two semesters. “Each semester one group of students was taught using PowerPoint slides and the other taught without slides to serve as a control group ...[but there was] ...no significant effect in terms of student performance” (p. 113). Results such as this seem curious in view of the speed and conviction with which PowerPoint has been embraced by educators.

Some other empirical studies are more generous, but are unpublished and unreviewed (e.g., Evans, 1998 ), or have significant methodological problems (e.g., Harknett & Cobane, 1997 ), or have untested assumptions (e.g., Lowry, 1999 ). Generally, the results of these studies point to the benefits of PowerPoint on student performance. For example, Lowry ( 1999 ) concluded that classes taught using PowerPoint “achieved better grades than the traditional-lecture cohort (51.8 and 51.9 versus 43.5%) ... and students exposed to PowerPoint lecturing had a positive attitude towards the method” (pp. 20–21).

Bartsch and Cobern ( 2003 , p. 78) provided the following good review of empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness of PowerPoint and computer presentations:

Overall research indicates that students prefer PowerPoint type presentations from transparencies (Cassady, 1998 ; Perry & Perry, 1998 ; Susskind & Gurien, 1999 ; West, 1997 ). Unfortunately, information on whether computer presentations improve student performance is much less clear. Several studies point to the idea that graphics improve student recall (ChanLin, 1998 , 2000 ; Lowry, 1999 ; Szabo & Hastings, 2000 , Exp. 2). However, many courses that adopted multimedia presentations have not shown a corresponding increase in student performance (Stoloff, 1995 ; Susskind & Gurien, 1999 ; Szabo & Hastings, 2000 . Exp. 1 and 3; West, 1997 ). In fact, one study demonstrated a decrease in student performance when the instructor switched from transparencies to PowerPoint (Bartlett, Cheng, & Strough, 2000 ).

In the study by Szabo and Hastings ( 2000 ), over 90% of students said that PowerPoint “is more attention capturing than the traditional method of lecturing,” and 85% found “PowerPoint lectures are more interesting than traditional lectures” (p. 179). They concluded that:

PowerPoint lectures, at least in some circumstances, mainly add to the entertainment rather than to the education of the students ... Apart from possible benefits on recall, no significant advantages to PowerPoint lecturing were found ... students like PowerPoint as a lecturing method. Their preference for PowerPoint lectures, in contrast to their beliefs, is not accompanied by better academic performance (p. 186).

Although students found PowerPoint entertaining, Szabo and Hastings ( 2000 ) noted aptly that “the challenge in the new millennium is not to entertain students ... but to improve or to facilitate learning” (p. 187). Such an improvement will not come easily if Parker ( 2001 ) is to be believed. He contended that presenters are concentrating more on “formatting slides—because it’s more fun to do than concentrate on what [they're] going to say” (Parker, 2001 , p. 5). A major challenge facing educators will be to convert the generally positive disposition of students to PowerPoint into significantly better learning and performance.

The Dynamics of the Pedagogical Setting

It is important to reflect upon the epistemology of our pedagogy. We live in a pedagogic realm in which the lecture has been regarded as “an accomplishment—bringing together a very particular constellation of speaker, space, technology, audience and attention” (Crang, 2003 , p. 242). In the lecture setting, the social roles, expectations, and power relations at play merit our reflection. The encompassing “performative aspects” of PowerPoint and how they “lend authority to the speaker” (Driver, 2003 , p. 229) are deserving of reflection too.

Accordingly, we now explore three aspects of the interaction between PowerPoint technology and its “spaces and audiences” (Driver, 2003 , p. 229)—first, whether or not PowerPoint serves as a crutch for many presenters, and second, whether or not it has a bad effect on the message by becoming “a tool to separate the presenter from the audience and the message” (Coursey, 2003 , para. 5). Third, we also explore the thesis that the visuality of PowerPoint presentations (which should enrich the message) is becoming THE message and that less of an audience's attention is being applied to a speaker's discussion of relevant content (DuFrene & Lehman, 2004 , p. 84).

There are divergent views about whether the teacher or presenter using PowerPoint is still the main actor and a Socratic-type figure in a learning play. One view is that “PowerPoint is teacher-centred. It puts the instructor at the center of the action” (Creed, 1997 ). As such, (s)he is a narrator tasked with framing the message or performance, both literally and perceptually. Opposed to this, is the view that the use of PowerPoint has reduced the role of the presenter to that of a stagehand (Blokzijl & Naeff, 2004 ) in which (s)he has been “effaced” by the visuality of the PowerPoint slide show (Crang, 2003 , p. 243). Consistent with this view, the role of the lecturer or presenter has changed: (s)he is a necessary, but annoying distraction, providing Muzak accompaniment to the lecture by means of an often “disembodied voice” (Crang, 2003 , p. 243). Indeed, Nunberg ( 1999 , p. 330) drew attention to the argument that the presenter is no longer needed because PowerPoint slides “have begun to take on a life of their own, as if they no longer needed talking heads to speak for them.” In this vein, Tufte ( 2003a ) argued that “rather than supplementing a presentation, [PowerPoint] has become a substitute for it” (p. 3).

Our view is that whether a PowerPoint presenter is the centre of attention or more of a stagehand will be a function of the communication ability of the presenter. Good presenters will most likely still be the centre of attention, using PowerPoint appropriately as a valuable communication aid to buttress their rhetoric. Poor presenters, such as nervous freshman students making their first assessable class presentation, will most likely be stagehands, with PowerPoint used as a dominating prop and their visual presence barely discernible.

What are the implications of interposing a PowerPoint presentation between an instructor and students? When we taught without PowerPoint or led a case discussion without PowerPoint or acted Socratic-like without PowerPoint, our relationship with students was unmediated and more human, more direct, less pre-meditated and less structured. The pedagogy involved depended on the particular situation, the process of interchange, the verbal and nonverbal communication, the repartee, the facial expressions, and the multitude of things that unfold during unmediated human relationships and dialogue. These are all “immediacy behaviours” which include such non-verbal actions as “eye contact, smiling, movement, adopting relaxed body positions, vocal expressiveness” and have been found to have a positive effect on student learning (see Hartnett, Römcke, & Yap, 2003 , p. 315). But when we subcontract our teaching to PowerPoint presentations, often we cannot see the faces of students. The ambient light is often low, and the focus of students is on the PowerPoint screen. It is not as easy to engage in effective “immediacy behaviours” with students, person-to-person, and to interest them vitally in the pursuit of knowledge.

Are educators at risk of falling into Freire's ( 1993 ) “banking education” trap by implicitly regarding education as an activity in which students simply withdraw dollops of something called “knowledge” in much the same way that money is withdrawn from a bank account? As a community of educators and students, are we acquiescing to an unthinking acceptance of PowerPoint's imposition of a conduit metaphor to frame (educational) communication in a way in which “language transfers thought to others” using words as a conduit (Reddy, 1993 , p. 167)? However, note that Reddy ( 1993 ) also cautioned that considering communication as a conduit metaphor “is leading us down a technological and social blind alley. That blind alley is mass communications systems coupled with mass neglect of the internal, human systems responsible for nine-tenths of the work in communicating” (p. 188). In this article we do not pursue the possible connection between the widespread deployment of PowerPoint in education and the implicit framing of educational communication by the conduit metaphor, but, at least according to Reddy, this merits further study.

What do we do if an unplanned, yet fruitful, discussion demands that a PowerPoint presentation be stopped dead in its tracks? Can we allow conversation and discussion to meander down a road with no known ultimate destination? Is it possible to ever discontinue a PowerPoint presentation or, in the best tradition of the theatre, must the “show go on?” Must a pre-planned schedule be followed rigidly because of an unwritten convention of PowerPoint that “no matter what, get through all the slides.” Or perhaps, even more chillingly, has the PowerPoint slideshow become the curriculum?

Rhetorical Elements

Teachers, public speakers, and business seminar presenters are rhetoricians, engaged in acts of persuasion: they seek to persuade or to educate, and to use PowerPoint as a visual aid to make “the logical structure of an argument more transparent” (Parker, 2001 , citing Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor of psychology, Steven Pinker, p. 6). Yet the knowledge most have of how to use PowerPoint effectively extends little beyond the general guidelines for using visual aids that have been outlined by Berko, Wolvin and Ray ( 1997 ) and Andrews and Baird ( 2000 ). Few lecturers or business seminar presenters seem adept at melding their verbal oratory with “visuality as an element of rhetorical invention” (Cyphert, 2004 , p. 81). And, as pointed out by Parker ( 2001 ), “instead of human contact” PowerPoint gives us a “human display ... we present to each other, instead of discussing” (p. 5, italics added). We exacerbate this problem by committing the “sin of triple delivery, where precisely the same text is seen on the screen, spoken aloud, and printed on the handout in front of you” (Parker, 2001 , p. 5).

There is a strong argument that the problems of PowerPoint arise from the contempt of many presenters for fundamental rhetorical principles and from their failure to ask such questions: “What does my audience need to know? What point am I trying to make? How do I make that point clearly, thoroughly, transparently? And is the organization of information effective for making my point clear and understandable?” (Shwom & Keller, 2003 , p. 4). Those who overlook these principles deserve “banishing into the wilderness of incoherence [because they] often lose their way in a thicket of points and sub-points [and compel a reader to] work too hard to decipher meaning” (Shwom & Keller, 2003 , pp. 4–5). One key rhetorical principle was proposed by Shwom and Keller ( 2003 ) for following by PowerPoint authors:

On each bullet point slide ... address only one main idea: a single discrete category with sub-items consistently related to that category. Do not use bullet points to present a sequence of ideas. In other words, use bullets to present inductive reasoning, not deductive reasoning (p. 8).

Additionally, many PowerPoint presenters fail to appreciate how rhetorical culture has been changed by PowerPoint communication. According to Cyphert ( 2005 ):

The whole notion of having a linear outline is actually a holdover from some pretty traditional—some would say archaic or even xenophobic—rhetorical presumptions. The sad thing is that PowerPoint offers tremendous tools for a speaker, but very, very few get past those dad-gummed bullet points. (response to question 10).

The linearity of PowerPoint and its pesky bullet points hold the prospect of seeming “too slow and boring to students used to MTV, instant messaging and MP3s” (Delaney, 2005 , p. R4, citing Tom Wilson, a technology-integration specialist at Hopkins High School, Minnetonka, Minnesota). Indeed, it suggests that Reddy's ( 1993 ) conduit metaphor has been given new breath by PowerPoint and is alive and well.

The metaphors that are associated with the use of PowerPoint merit reflection because the stance educators adopt with regard to the advantages and disadvantages of PowerPoint probably reflect the metaphors that imperceptibly fashion their attitudes. In assessing the way to use PowerPoint, it is important for educators to contemplate the fundamental metaphors that define their approach to teaching. We can identify four major metaphors that influence the way faculty members conceive teaching, by drawing on Fox ( 1983 ) and Lucas ( 2002 ). These are described in Amernic and Craig ( 2004 , p. 357) as:

the transfer conception: knowledge is a commodity to be transferred from one vessel to another, a concept consistent with Reddy's conduit metaphor ( 1993 );

the shaping conception: teaching is usually directed to developing the minds of students;

the travelling conception: the teacher leads students into new territory and, in doing so, gains new perspectives, too; and

the growing conception: the teacher is a nurturer.

Most users of PowerPoint appear to conceive their goals as educators to involve merely a one-way transmission of knowledge, rather than to promote the construction of knowledge and the analysis and synthesis of knowledge (Ramsden, 1992 ). This transfer, transportation, or conduit model of communication seems to fashion thinking by educators about PowerPoint: they conceive PowerPoint presentations as moving meaning across space in a way in which “the delivery, as opposed to the formulation of meaning” (Angus, 1998 , p. 21) is regarded as most important.

A major pedagogical issue with PowerPoint presentations is that receivers are “passively engaged” rather than “actively engaged.” Jones ( 2003 ) discussed the danger of making PowerPoint presentations available to students. Such practice is said to encourage “students to sit passively through the session since they may perceive they have ‘got the notes’” (p. 5). Tufte ( 2003b ) outlined the problems involved very strongly. They are summarized by Simons ( 2005 ) as follows:

It [PowerPoint] locks presenters into a linear, slide-by-slide format that discourages free association and creative thinking. It imposes artificial and potentially misleading hierarchies on information ... breaks information and data into fragments, making it more difficult to see the logical relationships between different sets of data. It encourages over-simplification by asking presenters to summarize key concepts in as few words as possible—e.g., bullet points—which can lead to gross generalizations, imprecise logic, superficial reasoning and, quite often, misleading conclusions. It imposes an authoritarian presenter/audience relationship rather than facilitating a give-and-take exchange of ideas and information. (p.5)

Some might argue that Tufte's case is exaggerated, that PowerPoint presentations can be paused for “contemplative effect, and they can serve as a springboard for conversation” (Cyphert, 2005 , question 13). Nonetheless, many PowerPoint presenters seem to embrace the transfer conception of education, in preference to the shaping, travelling, and growing conceptions. “If everyone has set their remarks in stone ahead of time (all using the same templates) then there is little room for comments of one to build upon another, or for a new idea to arise collaboratively ... Homogeneity is great for milk, but not for ideas” (Norvig, 2003 , p. 344). Educators using PowerPoint should give greater emphasis to working as partners with students, in designing learning activities with them, so that they encourage students to identify new ways of thinking for themselves. Most importantly, therefore, educators should reflect upon the explicit and implicit metaphors that help form the foundation of the cognitive world that is drawn upon in their use of PowerPoint.

PowerPoint Culture

In this section we examine three aspects of the “PowerPoint culture” in contemporary higher education institutions: power and ideology, cognition and psychology, and production influences.

Power and Ideology

What is the power of PowerPoint? This is an important question. The extent to which a PowerPoint presenter is in a position of power is often underestimated. Rose ( 2003 , p. 218, 2004 ) outlined five reasons why, in displaying slides, an academic has the potential to be a “powerful producer of knowledge.”

First, classes are given in spaces, such as lecture halls, that “encourage the practice of attention ... and in which attention is demanded” (Rose, 2003 , p. 218). We see this in the strong social convention governing audiences at PowerPoint presentations—to focus attention forward at the video screen and be quiet. Second, the display of slides is a powerful activity. Slides are often shown embedded in a luminescent square of light, surrounded by darkness. This seems to disallow any discussion of their truth status—and it privileges them by imposing a well-demarcated frame. Third, there is also a redirecting of the traditional flow of discourse in the lecture: the speaker “often seems compelled to turn towards the screen and to talk to the projection rather than to the audience” (Rose 2003 , p. 215). Fourth, slides “usually work to bestow authority on their expositor ... [who] mediates between the audience and the image by explaining it to them, and the apparent truth of the [slide] produces a truth-effect in the [expositor's] words as well” (Rose, 2003 , p. 216). Fifth, PowerPoint presentations “are not shown or seen the same way regardless of where they are screened; the way the [presenter] presents—and their audience views—images differently depend[s] on the location of their display ... [and] the speech and gestures” of the presenter (Rose, 2003 , p. 217).

An important aspect is the “visual uniformity” of PowerPoint. This may have ideological associations with the culture of its corporate creator, Microsoft—for example, in the subtle cognitive impacts of the aesthetic layout judgments made in default settings (Matless, 2003 ).

Cognition and Psychology

Ideally, lecturers should employ the most effective means to convey their message to students. But research into the effects and effectiveness of PowerPoint technology is rather poor. We are hampered, for example, by an underdeveloped understanding of the level of persuasiveness and psychological impact of PowerPoint as a new visual technology.

A lecture, like a court trial, ought to be regarded as a “search for truth and as a rhetorical contest” (Feigenson & Dunn, 2003 , p. 111). Consequently, there is a strong need for empirical research to address how various PowerPoint presentations have facilitative or prejudicial effects on audiences and how those audiences explain the perceptual, cognitive and emotional reasons for such effects (Feigenson & Dunn, 2003 , pp. 111–112). Currently, PowerPoint presenters have only a rudimentary appreciation of the conditions under which the visual technology they are using helps them to achieve their rhetorical aims.

However, research should focus not just on the visual technology involved. We need to understand also our audience's “perceptual, cognitive, and emotional capabilities, expectations, and habits” and to explore the relationships between audience and “visual technology” and “manipulations of that technology” in a better fashion (Feigenson & Dunn, 2003 , p. 112). In this vein a visual social semiotics approach, involving a study of signs, would help us to understand “how text and images work together to make meaning together for readers/users ... [and to] better understand the rhetorical, meaning-making potential” of PowerPoint presentations and imagery and make them more effective (Harrison, 2003 , p. 47). All this underscores the potential cognitive risks for both PowerPoint presenters and PowerPoint presentees. The cognitive world of both educators and students changes, perhaps radically, when PowerPoint becomes the default mode of discourse. We should at least attempt to become aware of the possibilities, both good and not-so-good, that this raises.

Production Influences

PowerPoint can be very subverting. Lecturers seem to spend disproportionate amounts of time mesmerized in tinkering with how to present their lecture—agonizing over the choice of design template, color scheme, page layout, and mode of slide transition. That is, they become engrossed in performing the production activities associated with the Microsoft PowerPoint software application rather than concentrate on how they will participate in “uniting the young and the old in the imaginative consideration of learning” (Whitehead, 1957/[1929] , p. 93). We need to be alert to the possibility that this production labour effort will interplay with the increasingly hyperactive and mediated demands on university faculty time (e.g., via email and the Internet) to preclude any semblance of a reflective academic life.

Orality, Visuality and Literacy

PowerPoint should be recognized as a new communication medium that is fundamentally changing the nature and dynamic of how we teach. For over four hundred years, as Postman ( 1993 ) noted, teaching settings have been characterized by a fine balance between two forms of learning: orality and the printed word . According to Postman ( 1993 ) orality fostered “gregariousness” and stressed “group learning, cooperation, and a sense of social responsibility”; and the printed word fostered “introspection and isolation” and stressed “individualized learning, competition, and personal autonomy” (p.17). Nonetheless, while teachers have tended to emphasize the visuality of print, they “have allowed orality its place in the classroom, and have therefore achieved a kind of pedagogical peace between these two forms of learning, so that what is valuable in each can be maximized” (Postman, 1993 , p. 17). What PowerPoint seems to have done is to disturb this pedagogical peace.

Orality, or at least, student-generated orality, seems to have been downgraded by the uni-directional nature of the discourse which accompanies most PowerPoint presentations. That discourse often has the hallmarks of a voice-over accompaniment to a visual display, usually of graphically enhanced printed words. The instructor risks being relegated from a centre stage role, to that of an incidental stagehand.

The use of projection to enhance the visuality of teaching has a long tradition in some disciplines: instructors in geography and art history have used 35 mm slides for about 100 years (Rose, 2003 , 2004 ). But the visual learning widely believed to be enhanced by PowerPoint seems to assume a false homogeneity: that PowerPoint is an appropriate, effective and amenable aid to learning, irrespective of discipline, learning objectives, and type of learner. For example, the visuality of PowerPoint seems much less likely to be amenable in teaching people to converse in foreign languages.

The form of learning we are gravitating to with PowerPoint is one of televisuality. This may be quite appropriate in the early 21st century. Young students of the “tech-savvy Play Station 2 generation” (Delaney, 2005 , p. R4) will be acculturated to such a mode. Many, if not most, will have been raised in homes bristling with the technology of television, interactive video games, DVD players, computers, and cell phones. The brevity and prevalence of PowerPoint's bullet points, abbreviations, and acronyms will resonate sympathetically with them, as they are likely to be voracious users of cell phone text messaging. Indeed, they would probably even find such use GR8 THK U. (This is commonly used Special Messaging Service [SMS] text for “Great, thank you.”) But this all comes at a price—the downgrading of orality and print.

There is also a profound impact on literacy. PowerPoint slides are often devoid of paragraphs, pronouns, punctuation, conjunctions, auxiliary verbs and articles. The obligation to form full sentences has become optional and the spelling of polysyllabic words has become a lost art in a sea of PowerPoint-induced abbreviations. (A similar criticism could be made of the use of overhead transparency slides. But we contend that the effect is much more pronounced with PowerPoint.) “The world is condensed into a few upbeat slides, with seven or so words on a line, seven lines on a slide” (Parker, 2001 , p. 2); and it is “a world where any complex thought must be broken into seven-word chunks, with colorful blobs between them” (Norvig, 2003 , p. 343). The use of language is imprecise and deserving of banishment into a “wilderness of incoherence,” for it causes audiences to “often lose their way in a thicket of points and sub-points” in “lists gone amuck” (Shwom & Keller, 2003 , pp. 4–5).

Parker ( 2001 , p. 6, citing Nass) argued that PowerPoint “empowers the provider of simple content ... but risks squeezing out the provider of process—that is to say, the rhetorician, the storyteller, the poet, the person whose thoughts cannot be arranged in the shape of a [PowerPoint] slide.” Parker ( 2001 ) recounted a telling anecdotal confession by Professor Nass about the capacity of PowerPoint to influence curriculum choices:

I hate to admit this but I actually removed a book from my syllabus last year because I couldn't figure out how to PowerPoint it. It's a lovely book called ‘Interface Culture,’ by Steven Johnson, but it's very discursive; the charm of it is the throwaways. When I read this book, I thought, my head's filled with ideas, and now I've got to write out exactly what those ideas are, and they're not neat. [Parker then observes that Nass] couldn't get the book into bullet points; every time he put something down, he realized that it wasn't quite right. Eventually, he abandoned the attempt, and instead of a lecture, he gave his students a recommendation. He told them it was a good book, urged them to read it, and moved on to the next bullet point (p. 6).

PowerPoint also effects how we expose students to a curriculum. Norvig ( 2003 ) argued that PowerPoint “makes it harder to have an open exchange between presenter and audience, to convey ideas that do not neatly fit into outline format” (p. 344). And Creed ( 1997 , Classroom assessment) makes several apposite points: first, “You may get less feedback from the class because your eyes and theirs are on the screen rather than looking at each other;” second, students don't have a chance to synthesize what they've heard; and third, the emphasis is on the quality of your presentation rather than your students' learning. Indeed, because of the facility for PowerPoint to be distributed in handout form at the commencement of classes and for PowerPoint presentations to be placed on the Web, students no longer need to listen carefully in class. Indeed, if lecturers simply read their PowerPoint presentations, there seems little point in them attending lectures at all.

All users of PowerPoint should respond to Postman's ( 1993 ) call and pause to reflect about any new technology, such as PowerPoint, and how it affects, however imperceptibly, their engagement with what and how they teach. They should engage in conversations and critique of new technologies, rather than to accept them blithely and unquestioningly.

As a society we should be mindful that PowerPoint, in concert with allied computer and Internet-based technology, is having a profound effect on higher education. PowerPoint is not merely a benign means of facilitating what educators have always done. Rather, it is changing much (perhaps most) of how we engage with our students and the disciplines which we profess. We should be curious as to why this is so. We should be eager to understand the assumptions and metaphors that subtly infuse PowerPoint. We should also be more aware of the culture, customs, and behaviour that are dragged along with PowerPoint and how they affect the way we think about our students, our audiences, ourselves, and our disciplines.

Amernic, J. H., & Craig, R. J. (1999). The internet in undergraduate management education: A concern for neophytes among metaphors. Prometheus, 17, 437–450.

Article Google Scholar

Amernic, J., & Craig, R. (2004). An agenda for the reform of accounting education in the post-Enron era: Moving accounting ‘out of the shadows.’ Abacus, 40, 342–378.

Andrews, P. H., & Baird, J. E. J. (2000). Communication for business and the professions. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Google Scholar

Angus, I. (1998). The materiality of expression: Harold Innis' communication theory and the discursive turn in the human sciences. Canadian Journal of Communication, 23, 9–29.

Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change , 13–25 Nov/Dec.

Bartlett, R. M., Cheng, S., & Strough, J. (2000). Multimedia versus traditional course instruction in undergraduate introductory psychology. Poster presentation, Annual Conference of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Bartsch, R. A., & Cobern, K. M. (2003). Effectiveness of PowerPoint presentations in lectures. Computers and Education, 41, 77–86.

Berko, R., Wolvin, A., & Ray, R. (1997). Business communication in a changing world. New York, NY: St. Martins.