- Subject guides

- Legal problem solving

Legal problem solving: IRAC

- Application

- Example 1 (Contract)

- Example 2 (Negligence)

- Find out more

- Back to Law research and writing guide

Advice on writing and study skills is provided by the Student Academic Success division; if you need further advice you can book a consultation with a Language and Learning Adviser .

What is IRAC?

Legal problem solving is an essential skill for the study and practice of law. There are a number of legal problem solving models, with the most popular being IRAC (Issue, Rule, Application, Conclusion) and MIRAT (Material facts, Issue, Rule/Resources, Arguments, Tentative conclusion).

Read more about MIRAT in this article Meet MIRAT: Legal Reasoning Fragmented into Learnable chunks

We will focus on the IRAC model in this guide, but note that there can be flexibility in the use of the models.

The IRAC methodology is useful to help you organise your legal analysis so that the reader can follow your argument. It is particularly helpful in writing exam answers and legal memos .

The MIRAT model starts with Material facts. This is an essential first step in the process and is a precursor to following the IRAC model.

- Before you state the legal issues, it is important to identify the facts you have been provided with, determining which ones are relevant, which are clearly not relevant, and which ones may become relevant once the rules are identified.

- It is from the facts that the issues can be identified.

- The facts and issues lead to the identification of the most appropriate rules, and the rules then determine the most useful way of construing the facts.

Let's take the example of Matthew, a 50-year old independent contractor from Victoria who has been engaged for some work by X Pty Ltd (a company). Matthew attends a number of staff meetings as well as a training course provided by the company. Do the terms of the contract referring to an 'employee' apply to him even as a contractor?

Relevant facts here are:

- Matthew is an independent contractor.

- He has an employment contract with company X Pty Ltd.

- He has attended some company staff meetings and a training course.

- The jurisdiction of Victoria may also be relevant.

- It is unlikely that Matthew's age would be a relevant fact.

- Think about questions that involve: Who, What, How, Where, and When.

- Is there any missing information?

- Next: Issue >>

Problem Solving Initiative (PSI)

Launched in 2017, PSI is a collection of courses that brings together students and faculty from law and other disciplines to actively apply creative problem solving, collaboration, and design thinking skills to complex, pressing challenges in a classroom setting.

PSI classes allow students to learn about topics such as sustainable food systems, connected and automated vehicles, human trafficking, “fake news,” firearm violence, and new music business models. At the same time, these classes allow students to learn about and apply tools, such as problem reframing, practicing empathy, prototyping, and more, that they will continue to apply in other classes, collaborative efforts, and the workplace.

Students and faculty have joined PSI from a range of U-M units, including Nursing, the Campus Farm, Engineering, History of Art, Information, Sociology, SEAS, Medicine, and Business.

Students in PSI Classes

- Develop creative problem-solving tools

- Lend their expertise and skills to a multidisciplinary team

- Learn human-centered design thinking skills

- Conduct research on, and engage in, advancing solutions to real-world challenges

- Collaborate with a range of U-M graduate and professional students and faculty experts

PSI Classes at a Glance

- Are open to all U-M graduate and professional students, fostering cross-campus collaboration

- Combine substantive learning and hands-on skill development

- Change every term, offering new challenges and teaching teams

- Register for PSI Classes

Current Course Offerings

Problem solving course untangles a web of tribal sovereignty and policing.

Students in Michigan Law’s Problem Solving Initiative (PSI) course Policing by Indian Tribes had the opportunity to take a deep dive into the legal challenges that complicate law enforcement in Native American communities.

Slavery’s Legacy in Architecture and Law

“How do we confront these ongoing legacies of slavery?” asks C.deBaca, who teaches the PSI course in collaboration with Phillip Bernstein, associate dean and professor adjunct at the Yale School of Architecture.

Register Now for PSI Classes

Challenge yourself with a Problem Solving Initiative class. Take a multi-disciplinary approach to real world problems.

PSI courses are 3-credit classes held at the Law School every Fall and Winter semester. Student teams use design thinking to research and build replicable, scalable, and disruptive solutions to real world challenges.

Michigan Law students use the Class Bidding process to select and register for PSI courses.

PSI courses are “professor pick," which involve an application, selection, and waitlist process. To request a PSI course or for information on registering please email [email protected] or select REGISTER and submit the form. Simply fill out the form, submit it, and wait for your registration to be approved!

Please note: We use the “professor pick” process only as a measure to ensure we have enough diversity of disciplines to make the course a true PSI experience.

UM graduate and professional students outside the Law School

Begin by consulting with your home unit’s graduate or academic advisor to learn about taking courses for credit outside of your home unit. PSI courses are cross-listed as EAS 731, ECON 741, EDUC 717, HS 741, LAW 741, PUBHLTH 741, PUBPOL 710, SI 605, SW 741. The PSI Human Trafficking Lab is also approved as an IPE course.

- Register Now

- About Class Bidding

- Questions? Email us!

Defending Against Deepfakes and Disinformation

Instructors: Barbara McQuade (Law) and Florian Schaub (UMSI)

While Artificial Intelligence is an incredible tool for human advancement, it can also be used as a weapon to exploit others and cause harm. As part of the Law School’s Problem Solving Initiative (PSI), this class will explore some of the ways that AI can be used to manipulate and deceive users online. We will discuss how deepfakes can be used to create disinformation about political candidates, to perpetrate fraud scams, and to embarrass celebrities with manufactured photos depicting them in a false light, often evading the reach of law enforcement. We will explore the ways in which these abuses cause harms at the individual level through financial loss, reputational harm or emotional distress. We will also consider harms that occur at the societal level by eroding confidence in truth and diminishing accountability. Students will work toward developing methods for detecting deep fakes and fostering resilience by devising countermeasures through technical solutions, platform policies, legal regulations, and public education.

Protecting the Exploited: Confronting Child Labor

Instructors: Luis C.deBaca (Law) and Hardy Vieux (Ford School of Public Policy)

Recently in the US children have been found in industrial agriculture, service on late-night custodial crews, roof construction, and food preparation; industries that reduce children to another labor input. Students from varied disciplines will apply design thinking principles to confront this wicked problem facing migrant children, US citizens, and children abroad whose exploitation fuels American consumers and business supply chains.

Students will confront child labor through a combination of the different professional and practice approaches that they bring to the table. The hallmark of the Michigan Law School’s PSI is assembling graduate and professional students from across the university to combine and enhance their own disciplinary approaches by applying design thinking principles to seemingly intractable problems.

- View Class Schedule

PSI Perspectives

Hear how PSI works and what you'll gain from professors and students who have been part of the program. 1.) Professor Bridgette Carr speaks to the cross-disciplinary opportunities available through PSI. 2.) PSI student Scott Henry discusses the benefits of working through complex problems and the skills you can develop. 3.) PSI student Marissa Keep explains how PSI changes your understanding of problem-solving and pushes you outside your comfort zone.

Also of Interest

- Experiential Learning

- Areas of Interest

- The VLS Course

- The Process

- The Resources

- The Podcast

Legal Problem Solving acts on this recommendation. Starting from a historical context for the current state of legal services delivery, this course introduces human-centered design thinking and other proven creative problem-solving constructs to provide a client-centered focus for creating innovative and effective methods of delivering legal services to a wide range of consumers in the 21st century.

To borrow from Professor JB Ruhl's syllabus for Law 2050 , this is an unusual law school course — by design. The forces shaping legal services delivery — the very forces that will shape professional opportunities for today's law students — are not adequately addressed by the traditional law school curriculum. This course seeks to fill in the gaps, to give soon-to-be lawyers the tools, methods, and processes required to meet client needs while designing sustainable, healthy ways of practicing law.

Human-Centered Design

The primary lens for work in this course is Human-Centered Design ("HCD"), a fluid framework for discovering problems, ideating solutions, and iterating to continuously improve solutions. HCD provides a methodology for considering both legal service delivery challenges, as well as clients' legal problems. The HCD method also serves as a tool individual law students can use to craft a rewarding, successful legal career.

Ultimately, this course is about doing, creating, and making — from the client's perspective. The reading is front-end loaded, as the required texts help explain tools, methods, and concepts we will use to "do" collaborative legal problem solving as the semester progresses.

In addition to the course texts (see LPS : : THE RESOURCES for a reading list), course content includes class-wide and small group discussions, guest speakers, presentations, creative problem-solving exercises, and a capstone design challenge. The collaborative capstone design challenge requires students to use HCD and other methods to create relevant solutions to real challenges faced across the legal services spectrum.

The course uses technologies leveraged by creative teams across disciplines, including Slack for all class communication, Trello to manage collaborative projects, and Google Drive (Docs and Sheets) for all written assignments.

This course also has this website/blog, where we will share student blog posts and other writing projects over the course of the semester. We also will introduce additional technology tools relevant to work in this course AND the practice of law, including mind-mapping apps, presentation apps, and workflow management tools.

Learning Outcomes

Students learn to creatively solve legal problems as well as complex legal services delivery problems . They develop and exercise their empathy and curiosity muscles — critical skills for a successful career in the 21st century. They learn and hone collaboration and communication skills , including the skills of delivering and receiving feedback . Students become comfortable in experimenting with and using a wide range of technology serving the 21st-century law practice.

Ultimately, students will understand and be able to apply human-centered design (mindsets and processes) and related tools to THINK LIKE A CLIENT and BE CURIOUS , and to creatively solve clients' legal and service delivery challenges while simultaneously crafting a personally rewarding and sustainable legal career.

LPS :: The Process

Design doing..

A Virtual Crash Course in Design Thinking / Stanford's d.school

Bootleg Bootcamp / Stanford's d.school

Collective Action Toolkit / Frog

Design Sprint Kit / Google

Design Thinking for Educators Toolkit / IDEO

Human Centered Design Field Guide / IDEO

Teachers Design for Education / The Business Innovation Factory

This Is Service Design Doing: Methods Library

LEGAL DESIGN:

Open Law Lab / Stanford

Legal Design Lab / Stanford Law School + d.school

Law by Design, The Book / Margaret Hagan (Stanford Open Law Lab)

Listen > Learn > Lead: A Guide to Improving Court Services Through User-Centered Design / published by IAALS

MAP x GAP Strategies for User-Informed Legal Design / Michigan Advocacy Program

The state of the legal profession.

A primary point of this course? To design solutions to some of the most wicked challenges facing the legal profession today. Want a taste of what those challenges might be? Dig into this list of curated readings.

The state of the legal profession/market (reports):

Report on the Future of Legal Services in the United States (2016) / American Bar Association

Profile of the Legal Profession (2020) / American Bar Association

Profile of the Legal Profession (2021) / American Bar Association

2021 Wolters Kluwer Future Ready Lawyer: Moving Beyond the Pandemic / Wolters Kluwer

Law Department Benchmarking Report (2021) (Executive Summary) / Association of Corporate Counsel (ACC)

Law Firms in Transition (2020) / Altman Weil

Business of Law and Legal Technology Survey (2020) / Aderant

Report on the State of the Legal Market (2021) / Georgetown Law's Center for the Study of the Legal Profession

Report on the State of the Legal Market (2022) / Georgetown Law's Center for the Study of the Legal Profession

State of Corporate Law Departments (2021) / ACC

State of the Industry Report (2021) / Corporate Legal Operations Consortium (CLOC)

EY Law Survey (2021) / EY

2021 Legal Department Operations (LDO) Index / Thompson Reuters

Amplifying the Voice of the Client in Law FIrms (2017) / Lexis Nexis

The state of access to justice and the law (reports and journals): Justice Needs and Satisfaction in the US 2021 / IAALS & HiiL

Daedalus: Access to Justice (2019) / American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Prognostications on what the future holds (or should hold) for lawyers and the legal profession (articles and videos):

Robot doctors and lawyers? It’s a change we should embrace. (2015) / Daniel Susskind

Upgrading Justice (video) (2016) / Richard Susskind at Harvard Law School

Legal Demand 3.0 (2017) / Jordan Furlong

The Future of the Practice of Law: Can Alternative Business Structures for the Legal Profession Improve Access to L egal Services? (2016) / James M. McCauley

The Future Is Now: Legal Services 2017 (videos of conference talks) (2017) / IL Supreme Court Commission on Professionalism - 2Civility

Should Tech Training For Lawyers Be Mandatory? (2017) / Bob Ambrogi

Are Lawyers Really Luddites? (2017) / John Alber

Well-being of law students and lawyers (research):

Suffering in Silence: The Survey of Law Student Well-Being and the Reluctance of Law Students to Seek Help for Substance Use and Mental Health Concerns (2016) / Organ, Jaffe, Bender

The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American Attorneys (2016) / Krill, Johnson, Albert

The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change (2017) / National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being

The Lawyer Personality: Why Lawyers Are Skeptical (2013) / Dr. Larry Richard

And some more food for thought on innovation in the legal profession:

Innovation in Organizations, Part I (015) (2017) / Bill Henderson

Innovation in Organizations, Part II (016) (2017) / Bill Henderson

Innovation in Organizations, Part III (017) (2017) / Bill Henderson

Design Thinking: User-Driven Legal Process Design Could Radically Change Delivery of Services (2016) / 3 Geeks and a Law Blog

A Successful Legal Change Management Story (027) (2017) / Bill Henderson

And more general food for thought:

In the AI Age, "Being Smart" Will Mean Something Completely Different (2017) / Harvard Business Review

LPS Course Tools

Embedded in LPS is a requirement that students experiment with technology as part of the problem-solving and collaboration process. To this end, we'll be using the following tech tools in our course workflow:

Slack - for all course communication

T rello - for all team projects

Google Drive (Docs / Sheets) - for all assigned writings and team projects

Coggle.It - for mindmapping exercises

Students also will be introduced to numerous other technologies that support collaborative and creative work, including video, presentation, and workflow applications.

Design Tools

Online platforms to create custom design tools, including journey maps, personas, service blueprints, practice model canvases, and more:

Canvanizer - create specific types of canvases / blueprints (e.g. service design, project management), or start tabula rasa

Smaply - create personas, journey maps, stakeholder maps

Practice Model Canvas - create a new legal service (or improve upon an existing one) with this canvas

LPS :: The Blog

Thoughts, musings, and ruminations from #legaldesign students and a #legaldesign prof., the podcast: a curious lawyer, join us for conversations with and about curious lawyers..

Director of Innovation Design

Director, PoLI Institute

Lecturer in Law

Vanderbilt Law School

@inspiredcat

Legal Problem Solving © Caitlin "Cat" Moon

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Problem-Solving Courts

Introduction, general overviews.

- Anthologies

- Reference Resources

- Transforming Behavior

- Public Defenders

- Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Restorative Justice

- Drug Courts

- Mental Health Courts

- Reentry Courts

- Domestic Violence Courts

- Family Courts

- Community Courts

- Practical Efficacy

- Race and Class Issues

- Social and Legal Critiques

- Challenging the Court-Centered Model

- The Problem of Net Widening

- Proposals for Reform

- Extension to Foreign Jurisdictions

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Communicating Scientific Findings in the Courtroom

- Community-Based Justice Systems

- Community-Based Substance Use Prevention

- Crime Control Policy

- Plea Bargaining

- Prosecution and Courts

- Sentencing Policy

- The Juvenile Justice System

- Therapeutic Jurisprudence

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Education Programs in Prison

- Mixed Methods Research in Criminal Justice and Criminology

- Victim Impact Statements

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Problem-Solving Courts by Eric J. Miller LAST REVIEWED: 06 November 2017 LAST MODIFIED: 14 April 2011 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396607-0073

Problem-solving courts are a recent and increasingly widespread alternative to traditional models of case management in criminal and civil courts. Defying simple definition, such courts encompass a loosely related group of practice areas and styles. Courts range from those addressing criminal justice issues, such as drug courts, mental health courts, reentry courts, domestic violence courts, and juvenile courts, to those less directly connected with traditional criminal justice issues, including family courts, homelessness courts, and community courts, to name just a few. Most courts, however, share some distinctive common features: channeling offenders away from traditional forms of legal regulation or punishment, relying on a more or less lengthy program of supervision and intervention that utilizes the informal or institutional authority of the judge, and a robust toleration of relapse backed by a graduated series of sanctions directed at altering the participants’ problematic conduct. These courts work to stream participants out of the traditional legal system either at the front end, prior to judgment being entered, or at the back end, as a consequence of entry of judgment, but prior to sentencing or other case disposition. Many, but not all, of these courts subscribe to the practice of either therapeutic or restorative justice (or both).

The major texts listed here are mostly book-length treatments and articles that covering issues common to the problem-solving courts in general by focusing on discrete court styles. Nolan 2001 ; Hora, et al. 1999 ; and Mackinem and Higgins 2008 discuss drug courts, whereas Berman, et al. 2005 ; Casey and Rottman 2005 ; Thompson 2002 ; and Winick 2003 are principally interested in the neighborhood or quality-of-life courts. Furthermore, the authors provide variable depth of treatment, often determined by the type of analysis. Berman, et al. 2005 ; Hora, et al. 1999 ; and Winick 2003 have all played an active role in developing various aspects of problem-solving court practice: they tend to focus on descriptions of court operation and practical impact. Articles written by law professors, social scientists, or anthropologists, such as Thompson 2002 , Mackinem and Higgins 2008 , and Fagan and Malkin 2003 , tend to place problem-solving courts in a more theoretically oriented style of analysis, bringing to bear core legal values, or sociological or cultural critique.

Berman, Greg, and John Feinblatt, with Sarah Glazer. 2005. Good courts: The case for problem-solving justice . New York: New Press.

Broad and accessible overview of problem-solving courts, and in particular those addressing quality-of-life issues, against the background of therapeutic jurisprudence and restorative justice. Suitable for undergraduate and graduate students.

Casey, Pamela M., and David B. Rottman. 2005. Problem-solving courts: Models and trends . Justice System Journal 26.1: 35–56.

Simple and effective overview of the key elements of different styles of problem-solving courts. Suitable for all levels of study

Fagan, Jeffrey, and Victoria Malkin. 2003. Theorizing community justice through community courts . Fordham Urban Law Review 30.3: 897–954.

Seminal examination of the manner in which community courts use the problem-solving method to generate public legitimacy for low-level criminal courts. Suitable for undergraduate and graduate students.

Hora, Peggy Fulton, William G. Schma, John T. A. Rosenthal. 1999. Therapeutic jurisprudence and the drug-treatment court movement: Revolutionizing the criminal justice system’s response to drug abuse and crime in America . Notre Dame Law Review 74.2: 439–538.

One of the essential works on the drug court movement and the use of therapeutic justice in the courtroom. Suitable for undergraduates and graduate students.

Mackinem, Mitchell B., and Paul Higgins. 2008. Drug court: Constructing the moral identity of drug offenders . Springfield, IL: C. C. Thomas.

A thorough and informative study of all aspects of drug-court operation, paying particular attention to the perspective of drug court participants. Suitable for undergraduates and graduate students.

Nolan, James L., Jr. 2001. Reinventing justice: The American drug court movement . Princeton Studies in Cultural Sociology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

The most important single work on drug courts, and a seminal study of the problem-solving movement from a sociological perspective. Suitable for undergraduate and graduate students.

Thompson, Anthony C. 2002. Courting disorder: Some thoughts on community courts. Washington University Journal of Law and Policy 10:63–100.

Discussing the emergence of the community court movement and the features it shares with other forms of problem-solving courts. Suitable for undergraduate and graduate students.

Winick, Bruce J. 2003. Therapeutic jurisprudence and problem solving courts . Fordham Urban Law Journal 30.3: 1055–1103.

Seminal overview of problem-solving courts from the perspective of therapeutic jurisprudence, written by one of the founders of the therapeutic justice movement. Suitable for undergraduate and graduate students.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Criminology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Active Offender Research

- Adler, Freda

- Adversarial System of Justice

- Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Aging Prison Population, The

- Airport and Airline Security

- Alcohol and Drug Prohibition

- Alcohol Use, Policy and Crime

- Alt-Right Gangs and White Power Youth Groups

- Animals, Crimes Against

- Back-End Sentencing and Parole Revocation

- Bail and Pretrial Detention

- Batterer Intervention Programs

- Bentham, Jeremy

- Big Data and Communities and Crime

- Biosocial Criminology

- Black's Theory of Law and Social Control

- Blumstein, Alfred

- Boot Camps and Shock Incarceration Programs

- Burglary, Residential

- Bystander Intervention

- Capital Punishment

- Chambliss, William

- Chicago School of Criminology, The

- Child Maltreatment

- Chinese Triad Society

- Civil Protection Orders

- Collateral Consequences of Felony Conviction and Imprisonm...

- Collective Efficacy

- Commercial and Bank Robbery

- Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children

- Community Change and Crime

- Community Corrections

- Community Disadvantage and Crime

- Comparative Criminal Justice Systems

- CompStat Models of Police Performance Management

- Confessions, False and Coerced

- Conservation Criminology

- Consumer Fraud

- Contextual Analysis of Crime

- Control Balance Theory

- Convict Criminology

- Co-Offending and the Role of Accomplices

- Corporate Crime

- Costs of Crime and Justice

- Courts, Drug

- Courts, Juvenile

- Courts, Mental Health

- Courts, Problem-Solving

- Crime and Justice in Latin America

- Crime, Campus

- Crime Control, Politics of

- Crime, (In)Security, and Islam

- Crime Prevention, Delinquency and

- Crime Prevention, Situational

- Crime Prevention, Voluntary Organizations and

- Crime Trends

- Crime Victims' Rights Movement

- Criminal Career Research

- Criminal Decision Making, Emotions in

- Criminal Justice Data Sources

- Criminal Justice Ethics

- Criminal Justice Fines and Fees

- Criminal Justice Reform, Politics of

- Criminal Justice System, Discretion in the

- Criminal Records

- Criminal Retaliation

- Criminal Talk

- Criminology and Political Science

- Criminology of Genocide, The

- Critical Criminology

- Cross-National Crime

- Cross-Sectional Research Designs in Criminology and Crimin...

- Cultural Criminology

- Cultural Theories

- Cybercrime Investigations and Prosecutions

- Cycle of Violence

- Deadly Force

- Defense Counsel

- Defining "Success" in Corrections and Reentry

- Developmental and Life-Course Criminology

- Digital Piracy

- Driving and Traffic Offenses

- Drug Control

- Drug Trafficking, International

- Drugs and Crime

- Elder Abuse

- Electronically Monitored Home Confinement

- Employee Theft

- Environmental Crime and Justice

- Experimental Criminology

- Family Violence

- Fear of Crime and Perceived Risk

- Felon Disenfranchisement

- Feminist Theories

- Feminist Victimization Theories

- Fencing and Stolen Goods Markets

- Firearms and Violence

- Forensic Science

- For-Profit Private Prisons and the Criminal Justice–Indust...

- Gangs, Peers, and Co-offending

- Gender and Crime

- Gendered Crime Pathways

- General Opportunity Victimization Theories

- Genetics, Environment, and Crime

- Green Criminology

- Halfway Houses

- Harm Reduction and Risky Behaviors

- Hate Crime Legislation

- Healthcare Fraud

- Hirschi, Travis

- History of Crime in the United Kingdom

- History of Criminology

- Homelessness and Crime

- Homicide Victimization

- Honor Cultures and Violence

- Hot Spots Policing

- Human Rights

- Human Trafficking

- Identity Theft

- Immigration, Crime, and Justice

- Incarceration, Mass

- Incarceration, Public Health Effects of

- Income Tax Evasion

- Indigenous Criminology

- Institutional Anomie Theory

- Integrated Theory

- Intermediate Sanctions

- Interpersonal Violence, Historical Patterns of

- Interrogation

- Intimate Partner Violence, Criminological Perspectives on

- Intimate Partner Violence, Police Responses to

- Investigation, Criminal

- Juvenile Delinquency

- Juvenile Justice System, The

- Kornhauser, Ruth Rosner

- Labeling Theory

- Labor Markets and Crime

- Land Use and Crime

- Lead and Crime

- LGBTQ Intimate Partner Violence

- LGBTQ People in Prison

- Life Without Parole Sentencing

- Local Institutions and Neighborhood Crime

- Lombroso, Cesare

- Longitudinal Research in Criminology

- Mandatory Minimum Sentencing

- Mapping and Spatial Analysis of Crime, The

- Mass Media, Crime, and Justice

- Measuring Crime

- Mediation and Dispute Resolution Programs

- Mental Health and Crime

- Merton, Robert K.

- Meta-analysis in Criminology

- Middle-Class Crime and Criminality

- Migrant Detention and Incarceration

- Mixed Methods Research in Criminology

- Money Laundering

- Motor Vehicle Theft

- Multi-Level Marketing Scams

- Murder, Serial

- Narrative Criminology

- National Deviancy Symposia, The

- Nature Versus Nurture

- Neighborhood Disorder

- Neutralization Theory

- New Penology, The

- Offender Decision-Making and Motivation

- Offense Specialization/Expertise

- Organized Crime

- Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs

- Panel Methods in Criminology

- Peacemaking Criminology

- Peer Networks and Delinquency

- Performance Measurement and Accountability Systems

- Personality and Trait Theories of Crime

- Persons with a Mental Illness, Police Encounters with

- Phenomenological Theories of Crime

- Police Administration

- Police Cooperation, International

- Police Discretion

- Police Effectiveness

- Police History

- Police Militarization

- Police Misconduct

- Police, Race and the

- Police Use of Force

- Police, Violence against the

- Policing and Law Enforcement

- Policing, Body-Worn Cameras and

- Policing, Broken Windows

- Policing, Community and Problem-Oriented

- Policing Cybercrime

- Policing, Evidence-Based

- Policing, Intelligence-Led

- Policing, Privatization of

- Policing, Proactive

- Policing, School

- Policing, Stop-and-Frisk

- Policing, Third Party

- Polyvictimization

- Positivist Criminology

- Pretrial Detention, Alternatives to

- Pretrial Diversion

- Prison Administration

- Prison Classification

- Prison, Disciplinary Segregation in

- Prison Education Exchange Programs

- Prison Gangs and Subculture

- Prison History

- Prison Labor

- Prison Visitation

- Prisoner Reentry

- Prisons and Jails

- Prisons, HIV in

- Private Security

- Probation Revocation

- Procedural Justice

- Property Crime

- Prostitution

- Psychiatry, Psychology, and Crime: Historical and Current ...

- Psychology and Crime

- Public Criminology

- Public Opinion, Crime and Justice

- Public Order Crimes

- Public Social Control and Neighborhood Crime

- Punishment Justification and Goals

- Qualitative Methods in Criminology

- Queer Criminology

- Race and Sentencing Research Advancements

- Race, Ethnicity, Crime, and Justice

- Racial Threat Hypothesis

- Racial Profiling

- Rape and Sexual Assault

- Rape, Fear of

- Rational Choice Theories

- Rehabilitation

- Religion and Crime

- Restorative Justice

- Risk Assessment

- Routine Activity Theories

- School Bullying

- School Crime and Violence

- School Safety, Security, and Discipline

- Search Warrants

- Seasonality and Crime

- Self-Control, The General Theory:

- Self-Report Crime Surveys

- Sentencing Enhancements

- Sentencing, Evidence-Based

- Sentencing Guidelines

- Sex Offender Policies and Legislation

- Sex Trafficking

- Sexual Revictimization

- Situational Action Theory

- Snitching and Use of Criminal Informants

- Social and Intellectual Context of Criminology, The

- Social Construction of Crime, The

- Social Control of Tobacco Use

- Social Control Theory

- Social Disorganization

- Social Ecology of Crime

- Social Learning Theory

- Social Networks

- Social Threat and Social Control

- Solitary Confinement

- South Africa, Crime and Justice in

- Sport Mega-Events Security

- Stalking and Harassment

- State Crime

- State Dependence and Population Heterogeneity in Theories ...

- Strain Theories

- Street Code

- Street Robbery

- Substance Use and Abuse

- Surveillance, Public and Private

- Sutherland, Edwin H.

- Technology and the Criminal Justice System

- Technology, Criminal Use of

- Terrorism and Hate Crime

- Terrorism, Criminological Explanations for

- Testimony, Eyewitness

- Trajectory Methods in Criminology

- Transnational Crime

- Truth-In-Sentencing

- Urban Politics and Crime

- US War on Terrorism, Legal Perspectives on the

- Victimization, Adolescent

- Victimization, Biosocial Theories of

- Victimization Patterns and Trends

- Victimization, Repeat

- Victimization, Vicarious and Related Forms of Secondary Tr...

- Victimless Crime

- Victim-Offender Overlap, The

- Violence Against Women

- Violence, Youth

- Violent Crime

- White-Collar Crime

- White-Collar Crime, The Global Financial Crisis and

- White-Collar Crime, Women and

- Wilson, James Q.

- Wolfgang, Marvin

- Women, Girls, and Reentry

- Wrongful Conviction

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

- --> Login or Sign Up

- Problem Solving Workshop

How to Approach a Case Study in a Problem Solving Workshop

John Palfrey and Lisa Brem

Share This Article

- Custom Field #1

- Custom Field #2

- Similar Products

Product Description

This note, designed for students in the Problem Solving Workshop, gives helpful tips for approaching problem solving case studies. Learning Objectives

- Help students effectively read problem solving case studies and prepare for problem solving class discussions and exercises.

Subjects Covered Problem Solving, Case Studies

Accessibility

To obtain accessible versions of our products for use by those with disabilities, please contact the HLS Case Studies Program at [email protected] or +1-617-496-1316.

Educator Materials

Registered members of this website can download this product at no cost. Please create an account or sign in to gain access to these materials.

Note: It can take up to three business days after you create an account to verify educator access. Verification will be confirmed via email.

For more information about the Problem Solving Workshop, or to request a teaching note for this case study, contact the Case Studies Program at [email protected] or +1-617-496-1316.

Additional Infor mation

The Problem Solving Workshop: A Video Introduction

Copyright Information

Please note that each purchase of this product entitles the purchaser to one download and use. If you need multiple copies, please purchase the number of copies you need. For more information, see Copying Your Case Study .

Product Videos

Custom field, product reviews, write a review.

Find Similar Products by Category

Recommended.

Creating Collaborative Documents

David Abrams

How to Be a Good Team Member

Joseph William Singer

Problem Solving for Lawyers

Writing and Presenting Short Memoranda to Supervisors

David B. Wilkins

- Related Products

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

2.1 Problem-solving

Being able to solve problems is an important skill. Problem-style questions require learners to identify and explain the correct legal principles and to use their reasoning skills to apply the law to facts of the problem-style question. That is a skill that needs to be practised and Activities 2 and 3 provide an opportunity to do this.

Problem-style questions invariably present a hypothetical set of facts and involve one or more legal issues and are often based on existing case law. When approaching a problem-style question you should:

- read the question carefully

- read the law carefully

- analyse the facts you have been given

- apply the law to the facts you have been given

- organise your answer carefully.

Problem-solving is important in law as one of the ways in which law is used is to resolve problems. Activity 2 asks you to read the law: Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Activity 3 then asks you to apply that knowledge to reach a conclusion.

Box 1 Article 6 ECHR

Right to a fair trial

- In the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law. Judgment shall be pronounced publicly but the press and public may be excluded from all or part of the trial in the interests of morals, public order or national security in a democratic society, where the interests of juveniles or the protection of the private life of the parties so require, or to the extent strictly necessary in the opinion of the court in special circumstances where publicity would prejudice the interests of justice.

- Everyone charged with a criminal offence shall be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law.

- a. to be informed promptly, in a language which he understands and in detail, of the nature and cause of the accusation against him;

- b. to have adequate time and facilities for the preparation of his defence;

- c. to defend himself in person or through legal assistance of his own choosing or, if he has not sufficient means to pay for legal assistance, to be given it free when the interests of justice so require;

- d. to examine or have examined witnesses against him and to obtain the attendance and examination of witnesses on his behalf under the same conditions as witnesses against him;

- e. to have the free assistance of an interpreter if he cannot understand or speak the language used in court.

Activity 2 The right to a fair trial: Article 6 ECHR

To complete this activity you will need to carefully read Article 6 of the ECHR in Box 1 above. Once you have read Article 6 and familiarised yourself with the rights it contains, answer the questions that follow.

- a. What rights are outlined by Article 6(1)?

- b. What does Article 6(1) say about judgment?

- c. What is the presumption of innocence?

- d. What minimum rights are contained in Article 6(3)?

The answers we gave to the questions were as follows.

Question a.

In any civil or criminal matter everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing. The hearing must take place within a reasonable timescale. The hearing must be before a court or tribunal which has been properly created and is independent and impartial. (I also noted that ‘reasonable time’ is not defined, nor are the words ‘independent’ and ‘impartial’.)

Question b.

The starting point is that the judgment of the court or tribunal should be given publicly. In certain circumstances, however, the press and public may be excluded. The list of circumstances ranged from public order, in the interest of morals, national security, in the interests of young offenders, and for the protection of private life, where it would be prejudicial to the interests of justice.

Question c.

The presumption of innocence means that until someone is found guilty according to the law they are presumed innocent. There was no definition of ‘according to the law’.

Question d.

The minimum rights are to:

- be informed promptly of the charge they face in a language they understand

- be informed of the nature of the charge and the circumstances leading to the charge

- have adequate time to prepare a defence

- provide a defence, either in person, through legal assistance of their choosing, or with the help of free legal assistance (which is provided when the interest of justice requires legal representation)

- examine witnesses (both for and against them)

- ensure all witnesses are to be treated in the same way

- have an interpreter if they cannot speak or understand the language of the court.

You should now attempt Activity 3.

Activity 3 What amounts to a fair trial?

Using the knowledge gained from Activity 2, read each of the scenarios that follow. Based on your knowledge of Article 6, decide in each scenario whether there has been a breach of that article.

- a. Ben is found guilty of theft. He complains that the judge frequently interrupted, both when he was giving evidence and when his defence advocate was questioning witnesses. The court record shows that there were numerous interruptions. The case goes to appeal. Is Ben’s conviction unsafe?

- b. A government minister drafts some legislation. A few years later the minister becomes a judge and hears a case which involves discussion of the legislation they drafted. Should they hear the case?

- c. Melanie brings a case against her employer to an employment appeal tribunal (EAT). She finds out that the advocate representing her employer also sits as a part-time chair of an EAT. She discovers that in their role as chair of the EAT the advocate had previously worked with the lay members of the tribunal which was hearing her case. She is concerned that the lay members may be biased when hearing her case.

Each of the scenarios was based on facts considered by the courts. Their decisions were as follows:

- a. The facts are based on CG v UK [2002] 34 EHRR 34. The case was heard by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). The ECtHR took account of the appeal and made a careful examination of the case. It found that there were interruptions; some of these were due to misunderstandings but they had not interrupted the flow or development of the defence case. The ECtHR held by a majority that Article 6 had not been breached. In our scenario Ben’s conviction would not be unsafe.

- b. The facts here are based on Davidson v Scottish Ministers [2004] UKHRR 1079. The case came before the House of Lords. Here Lord Hardie had been a government minister. As part of his role he helped draft and promote a piece of legislation. When he subsequently became a judge he was required to rule on the effect of the legislation he had drafted. It was held that he should not hear the case because of the risk of bias. There were concerns that he may subconsciously try to give a result which would not undermine the assurances he had given when promoting the legislation. The court made it clear that this cast no aspersions on Lord Hardie’s judicial integrity. In our scenario the judge should not hear the case.

- c. The facts are based on similar facts in Lawal v Northern Spirit [2003] UKHL 35, whereby an advocate who had returned to his own practice having been chair of an EAT found himself appearing as an advocate before lay members of an EAT, with whom he had worked previously as chair of an EAT. An objection was made. The matter was considered by the House of Lords. They held that lay members would look to the chair for guidance on the law and could be expected to develop a close relationship of trust and confidence with the chair. There was no finding of the rule against bias. In our scenario it is unlikely there would be a finding of bias. You may be interested to know that in the case the House of Lords also ruled that having barristers and advocates sitting as part-time chairs of EAT (which meant they were, in effect, part-time judges) should be discontinued, to ensure that there was no possibility of unconscious bias on the part of lay members in such situations and to ensure that public confidence was not undermined. The practice has now been discontinued.

For details on class times, days of the week, instructors, and grading and exam details, please view the Michigan Law Class Schedule .

Interdisciplinary Problem Solving

Interdisciplinary Problem Solving is a course offered at the Law School through the Problem Solving Initiative (PSI). (https://michigan.law.umich.edu/problem-solving-initiative) Through a team-based, experiential, and interdisciplinary learning model, small groups of U-M graduate and professional students work with faculty to explore and offer solutions to emerging, complex problems.

- Exam Center

- Ticket Center

- Flash Cards

Snell's law practice problems with answers

Are you seeking practice problems to help with your homework, or perhaps a deeper understanding of Snell’s law? This comprehensive guide provides everything you need to know about Snell’s law, from problem-solving techniques to fundamental concepts. It’s a one-stop resource for all your needs.

By the way, if you’re taking the AP Physics 1 exam this year, be sure to use this ultimate AP Physics 1 formula sheet. It’s a valuable resource.

Snell's Law Practice Problems

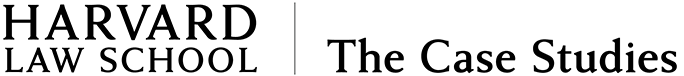

Problem (1): A beam of flashlight traveling in air incident on the surface of a thin glass at an angle of $38^\circ$ with the normal. The index of refraction of the glass is $1.56$. What is the angle of refraction?

Solution : When a beam of light strikes the boundary between two different media, such as air and glass, part of it is reflected, and another part is refracted.

The portion that enters the other side of the boundary is called the refracted ray . The angle that this ray makes with the normal to the boundary is known as the angle of refraction .

In this example problem, the light is initially in the air with an index of refraction $n_i=1.00$ and strikes the boundary surface separating air and glass at an angle of incidence $\theta_i=38^\circ$. The subscript $i$ denotes the incident.

The other medium is glass with $n_r=1.56$. The refracted ray lies within it at an unknown angle $\theta_r=?$, which should be found using Snell's law of refraction.

Before going further and solving the problem, we expect that since the light beam enters from a medium with a low index of refraction (air) into one with a high index of refraction (glass), the refracted ray should be bent toward the normal.

By applying Snell's law, we can verify this claim. \begin{align*} n_i \sin\theta_i&=n_r\sin\theta_r\\\\ (1.00)\sin 38^\circ&=(1.56)\sin\theta_r\\\\\Rightarrow \sin\theta_r&=\frac{1.00}{1.56}\sin 38^\circ\\\\&=0.3947\end{align*} Now, we find the angle whose sine is $0.3947$: \begin{align*} \sin\theta_r&=0.3947\\ \Rightarrow \theta_r&=\sin^{-1}(0.3947)\\&=23.25^\circ\end{align*} As expected, the refracted ray is bent towards the normal.

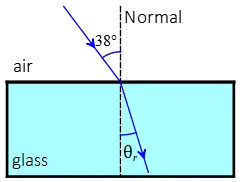

Problem (2): A boy is in a pool and shines a flashlight toward the level of it at a $35^\circ$ angle to the vertical. At what angle does the flashlight beam leave the pool? (the index of refraction of glass is $1.33$).

Solution : As before, a beam of light strikes the surface boundary of two different media, so we must use Snell's law to find the refracted angle in the air.

Contrary to the previous problems, here the light beam initially travels in the glass and enters the air, which has a lower index of refraction. Therefore, we expect that the angle of refraction in the air will bend away from the normal.

In other words, we expect that the angle of refraction will be greater than the angle of incidence, i.e., $\theta_r>\theta_i$. Now, we calculate it by applying Snell's law formula as below: \begin{align*} n_i \sin\theta_i&=n_r\sin\theta_r\\\\ (1.33)\sin 35^\circ&=(1.00)\sin\theta_r\\\\\Rightarrow \sin\theta_r&=\frac{1.33}{1.00}\sin 35^\circ\\\\&=0.7629\end{align*} The angle whose sine is $0.7629$ is found as below \begin{align*} \sin\theta_r&=0.7629 \\ \Rightarrow \theta_r&=\sin^{-1}(0.7629)\\&=49.72^\circ\end{align*} As expected, the refracted ray bends away from the normal.

One of the applications of Snell's law is in solving a phenomenon in physics called total internal reflection. For more practice, refer to the following page:

Total internal reflection on problems and solutions

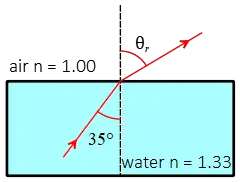

Problem (3): A slab of glass has an index of refraction of 1.5 and is submerged in water with $n=1.33$. A beam of monochrome light is incident on the slab and is refracted. (a) Find the angle of refraction if the angle of incidence is $30^\circ$. (b) Now, assume that the light is initially in the glass and incident on the glass-water surface. What is the refraction of light?

Solution : (a) A beam of light strikes the boundary between water ($n_i=1.33$) and glass ($n_r=1.5$) at point A at an angle of incidence $\theta_i=30^\circ$. Applying Snell's law of refraction, $n_i \sin \theta_i=n_r \sin \theta_r$, at the surface where the light enters the glass, we can solve for the unknown refracted angle as follows: \begin{align*} \sin\theta_r&=\frac {n_i}{n_r}\sin \theta_i \\\\ &=\frac{1.33}{1.5}\sin 30^\circ \\\\ &=0.443\end{align*} Therefore, the angle of refraction is $\theta_r=26.3^\circ$.

(b) In the second case, the light originates from the glass ($n_i=1.5$) and strikes the boundary with water ($n_r=1.33$) at an angle of incidence of $30^\circ$. Using Snell's law equation, we can calculate the angle of refraction in the water: \begin{align*}n_i\sin\theta_i&=n_r\sin\theta_r\\\\ (1.5)\sin 30^\circ&=(1.33)\sin\theta_r\\\\\Rightarrow \sin\theta_r&=\frac{1.5}{1.33}\sin 30^\circ\\\\&=0.563\end{align*} Thus, the angle of refraction in the water is $34.3^\circ$.

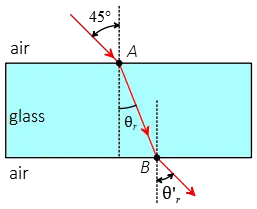

Problem (4): A beam of light traveling in the air, strikes a flat slab of glass at an incident angle of $30^\circ$. The index of refraction of the glass is $1.5$. At the moment of leaving the glass, what is the angle of refraction?

Solution : In this problem, we must apply Snell's law twice —once for the entering stage at the air-glass interface and the second for the exiting stage at the glass-air interface.

In the first stage, the incident beam is in the air ($n_i=1.00$) and strikes at point $A$ with an angle of incidence of $45^\circ$. The refracted beam lies inside the glass ($n_r=1.5$) with an unknown refracted angle $\theta_r$. This can be determined as follows: \begin{align*} n_i \sin\theta_i&=n_r\sin\theta_r\\\\ (1.00)\sin 45^\circ&=(1.5)\sin\theta_r\\\\\Rightarrow \sin\theta_r&=\frac{1.00}{1.5}\sin 45^\circ\\\\&=0.4715\end{align*} Therefore, the first refracted angle, which occurs in the slab of glass, is $\theta_r=28.13^\circ$.

For the second stage, the beam of light inside the glass strikes the glass-air interface at point $B$ with an angle of incidence of $28.13^\circ$. The refracted beam enters the air ($n_r=1.00$) with an unknown angle $\theta'_r$, which can be found as follows: \begin{align*} n_i \sin\theta_i&=n_r\sin\theta'_r\\\\ (1.5)\sin 28.13^\circ&=(1.00)\sin\theta'_r\\\\\Rightarrow \sin\theta'_r&=\frac{1.5}{1.00}\sin 28.13^\circ\\\\&=0.7072\end{align*} Finally, the beam leaves the glass with an angle of refraction of $45^\circ$, which is the same as the angle of entering.

When a beam of light passes through a slab of any material with uniform thickness the angle of entering (incident angle) and the leaving angle (refracted angle) are the same.

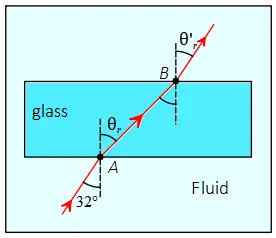

Problem (5): A uniform rectangular block of glass ($n=1.56$) surrounded by some fluid with an index of refraction $n=1.63$. A beam of light strikes at point $A$ at an angle of $32^\circ$ to the normal. At what angle does the light beam leave the slab?

Solution : In this problem, we must apply Snell's law twice - at points $A$ and again at point $B$ - to determine the path of the refracted ray as it exits the slab. Snell's law is given by the equation $n_i \sin\theta_i=n_r\sin\theta_r$ where $n_i$ and $\theta_i$ are the index of refraction and angle of incidence of the medium where the ray originates, respectively.

Similarly, $n_r$ and $\theta_r$ are the index of refraction and angle of refraction of the medium where the ray exits, respectively.

To find the angle of refraction at point $A$, We solve Snell's law for $\sin \theta_r$ as follows: \begin{align*} n_i \sin\theta_i&=n_r\sin\theta_r\\\\ (1.63)\sin 32^\circ&=(1.56)\sin\theta_r\\\\\Rightarrow \sin\theta_r&=\frac{1.63}{1.56}\sin 32^\circ\\\\&=0.5537\end{align*} Taking the inverse sine of both sides, we find the refracted angle at point $A$: \begin{align*}\theta_r&=\sin^{-1}(0.5537)\\&=33.62^\circ\end{align*} Now, the refracted ray acts as the incident ray and strikes point $B$ at an angle of incidence of $33.62^\circ$ to the normal. This ray is inside the glass with $n_i=1.56$. Again, applying Snell's law of refraction at point $B$, we have \begin{align*} n_i \sin\theta_i&=n_r\sin\theta'_r\\\\ (1.56)\sin 33.62^\circ&=(1.63)\sin\theta'_r\\\\\Rightarrow \sin\theta'_r&=\frac{1.56}{1.63}\sin 33.62^\circ\\\\&=0.5200\end{align*} Taking the inverse sine of both sides, we find \begin{align*}\theta'_r&=\sin^{-1}(0.5200)\\&=32.00^\circ\end{align*} Thus, as expected, the light beam leaves the slab at the same angle to the normal as the angle of incidence.

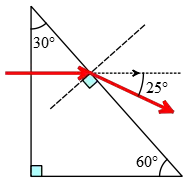

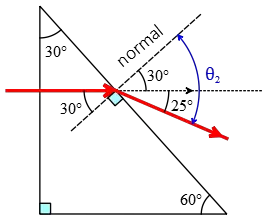

Problem (6): A beam of light incident on and deflected by a $30^\circ-60^\circ-90^\circ$ prism as shown in the figure. The deflected light makes an angle of $25^\circ$ with the direction of the incident ray. Using laws of refraction, find the prism's index of refraction.

Solution : In this example problem, there are two boundary surfaces to consider. The first is the front face of the prism, where the original ray strikes at a normal angle, allowing it to enter the prism without deflection.

The second surface is the hypotenuse of the prism, where the previously reflected ray strikes and undergoes final deflection by the prism.

Since the final refraction occurs on the hypotenuse, we first draw the normal to it. From the resulting geometry, we can determine all the necessary components for applying Snell's law, i.e., the angles of incidence and refraction.

From geometry, we can see the ray's angle of incidence on the hypotenuse is the same as the apex angle of the prism, i.e., $\theta_1=30^\circ$.

The ray exits the prism at an angle of $\theta_2$, which, according to the geometry, is the sum of the deflection angle ($25^\circ$) and the angle of incidence ($30^\circ$), i.e., $\theta_2=25^\circ+30^\circ=55^\circ$. By substituting these values, along with the index of refraction for air ($n_2=1.00$), into Snell's law, we can find $n_1$ for the prism. \begin{align*} n_1\sin\theta_1&=n_2\sin\theta_2\\\\n_1(\sin 30^\circ)&=(1.00)(\sin 55^\circ)\\\\\Rightarrow n_1&=\frac{(1.00)(\sin 55^\circ)}{\sin 30^\circ}\\\\&=1.63 \end{align*} Note that to apply Snell's law, we must determine all angles with respect to the normal to the boundary between two different media.

Author: Dr. Ali Nemati Date Published: 5/8/2021

© 2015 All rights reserved. by Physexams.com

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

Do You Understand the Problem You’re Trying to Solve?

To solve tough problems at work, first ask these questions.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

Problem solving skills are invaluable in any job. But all too often, we jump to find solutions to a problem without taking time to really understand the dilemma we face, according to Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg , an expert in innovation and the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

In this episode, you’ll learn how to reframe tough problems by asking questions that reveal all the factors and assumptions that contribute to the situation. You’ll also learn why searching for just one root cause can be misleading.

Key episode topics include: leadership, decision making and problem solving, power and influence, business management.

HBR On Leadership curates the best case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, to help you unlock the best in those around you. New episodes every week.

- Listen to the original HBR IdeaCast episode: The Secret to Better Problem Solving (2016)

- Find more episodes of HBR IdeaCast

- Discover 100 years of Harvard Business Review articles, case studies, podcasts, and more at HBR.org .

HANNAH BATES: Welcome to HBR on Leadership , case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, hand-selected to help you unlock the best in those around you.

Problem solving skills are invaluable in any job. But even the most experienced among us can fall into the trap of solving the wrong problem.

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg says that all too often, we jump to find solutions to a problem – without taking time to really understand what we’re facing.

He’s an expert in innovation, and he’s the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

In this episode, you’ll learn how to reframe tough problems, by asking questions that reveal all the factors and assumptions that contribute to the situation. You’ll also learn why searching for one root cause can be misleading. And you’ll learn how to use experimentation and rapid prototyping as problem-solving tools.

This episode originally aired on HBR IdeaCast in December 2016. Here it is.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Welcome to the HBR IdeaCast from Harvard Business Review. I’m Sarah Green Carmichael.

Problem solving is popular. People put it on their resumes. Managers believe they excel at it. Companies count it as a key proficiency. We solve customers’ problems.

The problem is we often solve the wrong problems. Albert Einstein and Peter Drucker alike have discussed the difficulty of effective diagnosis. There are great frameworks for getting teams to attack true problems, but they’re often hard to do daily and on the fly. That’s where our guest comes in.

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg is a consultant who helps companies and managers reframe their problems so they can come up with an effective solution faster. He asks the question “Are You Solving The Right Problems?” in the January-February 2017 issue of Harvard Business Review. Thomas, thank you so much for coming on the HBR IdeaCast .

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Thanks for inviting me.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, I thought maybe we could start by talking about the problem of talking about problem reframing. What is that exactly?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Basically, when people face a problem, they tend to jump into solution mode to rapidly, and very often that means that they don’t really understand, necessarily, the problem they’re trying to solve. And so, reframing is really a– at heart, it’s a method that helps you avoid that by taking a second to go in and ask two questions, basically saying, first of all, wait. What is the problem we’re trying to solve? And then crucially asking, is there a different way to think about what the problem actually is?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, I feel like so often when this comes up in meetings, you know, someone says that, and maybe they throw out the Einstein quote about you spend an hour of problem solving, you spend 55 minutes to find the problem. And then everyone else in the room kind of gets irritated. So, maybe just give us an example of maybe how this would work in practice in a way that would not, sort of, set people’s teeth on edge, like oh, here Sarah goes again, reframing the whole problem instead of just solving it.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I mean, you’re bringing up something that’s, I think is crucial, which is to create legitimacy for the method. So, one of the reasons why I put out the article is to give people a tool to say actually, this thing is still important, and we need to do it. But I think the really critical thing in order to make this work in a meeting is actually to learn how to do it fast, because if you have the idea that you need to spend 30 minutes in a meeting delving deeply into the problem, I mean, that’s going to be uphill for most problems. So, the critical thing here is really to try to make it a practice you can implement very, very rapidly.

There’s an example that I would suggest memorizing. This is the example that I use to explain very rapidly what it is. And it’s basically, I call it the slow elevator problem. You imagine that you are the owner of an office building, and that your tenants are complaining that the elevator’s slow.

Now, if you take that problem framing for granted, you’re going to start thinking creatively around how do we make the elevator faster. Do we install a new motor? Do we have to buy a new lift somewhere?

The thing is, though, if you ask people who actually work with facilities management, well, they’re going to have a different solution for you, which is put up a mirror next to the elevator. That’s what happens is, of course, that people go oh, I’m busy. I’m busy. I’m– oh, a mirror. Oh, that’s beautiful.

And then they forget time. What’s interesting about that example is that the idea with a mirror is actually a solution to a different problem than the one you first proposed. And so, the whole idea here is once you get good at using reframing, you can quickly identify other aspects of the problem that might be much better to try to solve than the original one you found. It’s not necessarily that the first one is wrong. It’s just that there might be better problems out there to attack that we can, means we can do things much faster, cheaper, or better.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, in that example, I can understand how A, it’s probably expensive to make the elevator faster, so it’s much cheaper just to put up a mirror. And B, maybe the real problem people are actually feeling, even though they’re not articulating it right, is like, I hate waiting for the elevator. But if you let them sort of fix their hair or check their teeth, they’re suddenly distracted and don’t notice.

But if you have, this is sort of a pedestrian example, but say you have a roommate or a spouse who doesn’t clean up the kitchen. Facing that problem and not having your elegant solution already there to highlight the contrast between the perceived problem and the real problem, how would you take a problem like that and attack it using this method so that you can see what some of the other options might be?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Right. So, I mean, let’s say it’s you who have that problem. I would go in and say, first of all, what would you say the problem is? Like, if you were to describe your view of the problem, what would that be?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: I hate cleaning the kitchen, and I want someone else to clean it up.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: OK. So, my first observation, you know, that somebody else might not necessarily be your spouse. So, already there, there’s an inbuilt assumption in your question around oh, it has to be my husband who does the cleaning. So, it might actually be worth, already there to say, is that really the only problem you have? That you hate cleaning the kitchen, and you want to avoid it? Or might there be something around, as well, getting a better relationship in terms of how you solve problems in general or establishing a better way to handle small problems when dealing with your spouse?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Or maybe, now that I’m thinking that, maybe the problem is that you just can’t find the stuff in the kitchen when you need to find it.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Right, and so that’s an example of a reframing, that actually why is it a problem that the kitchen is not clean? Is it only because you hate the act of cleaning, or does it actually mean that it just takes you a lot longer and gets a lot messier to actually use the kitchen, which is a different problem. The way you describe this problem now, is there anything that’s missing from that description?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: That is a really good question.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Other, basically asking other factors that we are not talking about right now, and I say those because people tend to, when given a problem, they tend to delve deeper into the detail. What often is missing is actually an element outside of the initial description of the problem that might be really relevant to what’s going on. Like, why does the kitchen get messy in the first place? Is it something about the way you use it or your cooking habits? Is it because the neighbor’s kids, kind of, use it all the time?

There might, very often, there might be issues that you’re not really thinking about when you first describe the problem that actually has a big effect on it.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: I think at this point it would be helpful to maybe get another business example, and I’m wondering if you could tell us the story of the dog adoption problem.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Yeah. This is a big problem in the US. If you work in the shelter industry, basically because dogs are so popular, more than 3 million dogs every year enter a shelter, and currently only about half of those actually find a new home and get adopted. And so, this is a problem that has persisted. It’s been, like, a structural problem for decades in this space. In the last three years, where people found new ways to address it.

So a woman called Lori Weise who runs a rescue organization in South LA, and she actually went in and challenged the very idea of what we were trying to do. She said, no, no. The problem we’re trying to solve is not about how to get more people to adopt dogs. It is about keeping the dogs with their first family so they never enter the shelter system in the first place.

In 2013, she started what’s called a Shelter Intervention Program that basically works like this. If a family comes and wants to hand over their dog, these are called owner surrenders. It’s about 30% of all dogs that come into a shelter. All they would do is go up and ask, if you could, would you like to keep your animal? And if they said yes, they would try to fix whatever helped them fix the problem, but that made them turn over this.

And sometimes that might be that they moved into a new building. The landlord required a deposit, and they simply didn’t have the money to put down a deposit. Or the dog might need a $10 rabies shot, but they didn’t know how to get access to a vet.

And so, by instigating that program, just in the first year, she took her, basically the amount of dollars they spent per animal they helped went from something like $85 down to around $60. Just an immediate impact, and her program now is being rolled out, is being supported by the ASPCA, which is one of the big animal welfare stations, and it’s being rolled out to various other places.

And I think what really struck me with that example was this was not dependent on having the internet. This was not, oh, we needed to have everybody mobile before we could come up with this. This, conceivably, we could have done 20 years ago. Only, it only happened when somebody, like in this case Lori, went in and actually rethought what the problem they were trying to solve was in the first place.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, what I also think is so interesting about that example is that when you talk about it, it doesn’t sound like the kind of thing that would have been thought of through other kinds of problem solving methods. There wasn’t necessarily an After Action Review or a 5 Whys exercise or a Six Sigma type intervention. I don’t want to throw those other methods under the bus, but how can you get such powerful results with such a very simple way of thinking about something?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: That was something that struck me as well. This, in a way, reframing and the idea of the problem diagnosis is important is something we’ve known for a long, long time. And we’ve actually have built some tools to help out. If you worked with us professionally, you are familiar with, like, Six Sigma, TRIZ, and so on. You mentioned 5 Whys. A root cause analysis is another one that a lot of people are familiar with.

Those are our good tools, and they’re definitely better than nothing. But what I notice when I work with the companies applying those was those tools tend to make you dig deeper into the first understanding of the problem we have. If it’s the elevator example, people start asking, well, is that the cable strength, or is the capacity of the elevator? That they kind of get caught by the details.

That, in a way, is a bad way to work on problems because it really assumes that there’s like a, you can almost hear it, a root cause. That you have to dig down and find the one true problem, and everything else was just symptoms. That’s a bad way to think about problems because problems tend to be multicausal.

There tend to be lots of causes or levers you can potentially press to address a problem. And if you think there’s only one, if that’s the right problem, that’s actually a dangerous way. And so I think that’s why, that this is a method I’ve worked with over the last five years, trying to basically refine how to make people better at this, and the key tends to be this thing about shifting out and saying, is there a totally different way of thinking about the problem versus getting too caught up in the mechanistic details of what happens.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: What about experimentation? Because that’s another method that’s become really popular with the rise of Lean Startup and lots of other innovation methodologies. Why wouldn’t it have worked to, say, experiment with many different types of fixing the dog adoption problem, and then just pick the one that works the best?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: You could say in the dog space, that’s what’s been going on. I mean, there is, in this industry and a lot of, it’s largely volunteer driven. People have experimented, and they found different ways of trying to cope. And that has definitely made the problem better. So, I wouldn’t say that experimentation is bad, quite the contrary. Rapid prototyping, quickly putting something out into the world and learning from it, that’s a fantastic way to learn more and to move forward.

My point is, though, that I feel we’ve come to rely too much on that. There’s like, if you look at the start up space, the wisdom is now just to put something quickly into the market, and then if it doesn’t work, pivot and just do more stuff. What reframing really is, I think of it as the cognitive counterpoint to prototyping. So, this is really a way of seeing very quickly, like not just working on the solution, but also working on our understanding of the problem and trying to see is there a different way to think about that.

If you only stick with experimentation, again, you tend to sometimes stay too much in the same space trying minute variations of something instead of taking a step back and saying, wait a minute. What is this telling us about what the real issue is?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, to go back to something that we touched on earlier, when we were talking about the completely hypothetical example of a spouse who does not clean the kitchen–

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Completely, completely hypothetical.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Yes. For the record, my husband is a great kitchen cleaner.

You started asking me some questions that I could see immediately were helping me rethink that problem. Is that kind of the key, just having a checklist of questions to ask yourself? How do you really start to put this into practice?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I think there are two steps in that. The first one is just to make yourself better at the method. Yes, you should kind of work with a checklist. In the article, I kind of outlined seven practices that you can use to do this.

But importantly, I would say you have to consider that as, basically, a set of training wheels. I think there’s a big, big danger in getting caught in a checklist. This is something I work with.

My co-author Paddy Miller, it’s one of his insights. That if you start giving people a checklist for things like this, they start following it. And that’s actually a problem, because what you really want them to do is start challenging their thinking.

So the way to handle this is to get some practice using it. Do use the checklist initially, but then try to step away from it and try to see if you can organically make– it’s almost a habit of mind. When you run into a colleague in the hallway and she has a problem and you have five minutes, like, delving in and just starting asking some of those questions and using your intuition to say, wait, how is she talking about this problem? And is there a question or two I can ask her about the problem that can help her rethink it?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Well, that is also just a very different approach, because I think in that situation, most of us can’t go 30 seconds without jumping in and offering solutions.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Very true. The drive toward solutions is very strong. And to be clear, I mean, there’s nothing wrong with that if the solutions work. So, many problems are just solved by oh, you know, oh, here’s the way to do that. Great.

But this is really a powerful method for those problems where either it’s something we’ve been banging our heads against tons of times without making progress, or when you need to come up with a really creative solution. When you’re facing a competitor with a much bigger budget, and you know, if you solve the same problem later, you’re not going to win. So, that basic idea of taking that approach to problems can often help you move forward in a different way than just like, oh, I have a solution.

I would say there’s also, there’s some interesting psychological stuff going on, right? Where you may have tried this, but if somebody tries to serve up a solution to a problem I have, I’m often resistant towards them. Kind if like, no, no, no, no, no, no. That solution is not going to work in my world. Whereas if you get them to discuss and analyze what the problem really is, you might actually dig something up.