CASP Checklists

How to use our CASP Checklists

Referencing and Creative Commons

- Online Training Courses

- CASP Workshops

- What is Critical Appraisal

- Study Designs

- Useful Links

- Bibliography

- View all Tools and Resources

- Testimonials

Critical Appraisal Checklists

We offer a number of free downloadable checklists to help you more easily and accurately perform critical appraisal across a number of different study types.

The CASP checklists are easy to understand but in case you need any further guidance on how they are structured, take a look at our guide on how to use our CASP checklists .

CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist

- Print & Fill

CASP Systematic Review Checklist

CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist

CASP Cohort Study Checklist

CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist

CASP Case Control Study Checklist

CASP Economic Evaluation Checklist

CASP Clinical Prediction Rule Checklist

Checklist Archive

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist 2018 fillable form

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist 2018

CASP Checklist

Need more information?

- Online Learning

- Privacy Policy

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) will use the information you provide on this form to be in touch with you and to provide updates and marketing. Please let us know all the ways you would like to hear from us:

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here.

Copyright 2024 CASP UK - OAP Ltd. All rights reserved Website by Beyond Your Brand

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 27, Issue Suppl 2

- 12 Critical appraisal tools for qualitative research – towards ‘fit for purpose’

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Veronika Williams 1 ,

- Anne-Marie Boylan 2 ,

- Newhouse Nikki 2 ,

- David Nunan 2

- 1 Nipissing University, North Bay, Canada

- 2 University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Qualitative research has an important place within evidence-based health care (EBHC), contributing to policy on patient safety and quality of care, supporting understanding of the impact of chronic illness, and explaining contextual factors surrounding the implementation of interventions. However, the question of whether, when and how to critically appraise qualitative research persists. Whilst there is consensus that we cannot - and should not – simplistically adopt existing approaches for appraising quantitative methods, it is nonetheless crucial that we develop a better understanding of how to subject qualitative evidence to robust and systematic scrutiny in order to assess its trustworthiness and credibility. Currently, most appraisal methods and tools for qualitative health research use one of two approaches: checklists or frameworks. We have previously outlined the specific issues with these approaches (Williams et al 2019). A fundamental challenge still to be addressed, however, is the lack of differentiation between different methodological approaches when appraising qualitative health research. We do this routinely when appraising quantitative research: we have specific checklists and tools to appraise randomised controlled trials, diagnostic studies, observational studies and so on. Current checklists for qualitative research typically treat the entire paradigm as a single design (illustrated by titles of tools such as ‘CASP Qualitative Checklist’, ‘JBI checklist for qualitative research’) and frameworks tend to require substantial understanding of a given methodological approach without providing guidance on how they should be applied. Given the fundamental differences in the aims and outcomes of different methodologies, such as ethnography, grounded theory, and phenomenological approaches, as well as specific aspects of the research process, such as sampling, data collection and analysis, we cannot treat qualitative research as a single approach. Rather, we must strive to recognise core commonalities relating to rigour, but considering key methodological differences. We have argued for a reconsideration of current approaches to the systematic appraisal of qualitative health research (Williams et al 2021), and propose the development of a tool or tools that allow differentiated evaluations of multiple methodological approaches rather than continuing to treat qualitative health research as a single, unified method. Here we propose a workshop for researchers interested in the appraisal of qualitative health research and invite them to develop an initial consensus regarding core aspects of a new appraisal tool that differentiates between the different qualitative research methodologies and thus provides a ‘fit for purpose’ tool, for both, educators and clinicians.

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm-2022-EBMLive.36

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

74k Accesses

27 Citations

71 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Patrik Aspers & Ugo Corte

Qualitative Research: Ethical Considerations

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

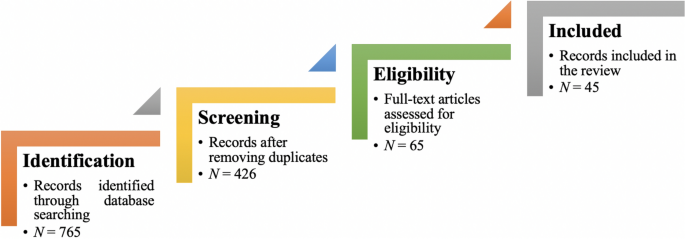

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

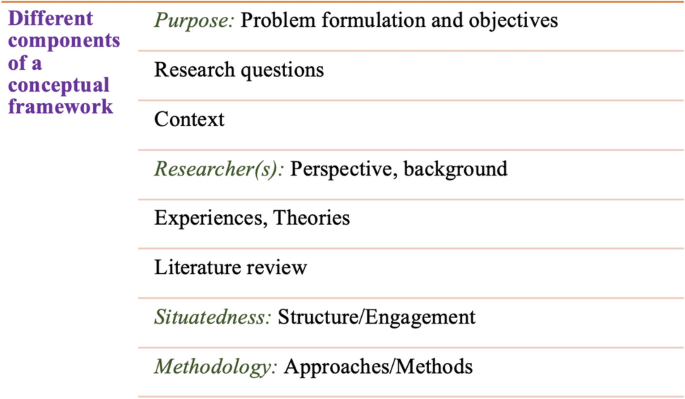

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Qualitative Research

- What is Qualitative Research

- PEO for Qualitative Questions

- SPIDER for Mixed Methods Qualitative Research Questions

- Finding Qualitative Research Articles

- Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Research Articles

- Mixed Methods Research

- Qualitative Synthesis

Tools for Critical Appraisal

- CASP: Qualitative Research Studies

- Joanna Briggs Institute: Checklist for Qualitative Research

- McMaster Critical Review Form: Qualitative Research

- SURE for Qualitative Studies

- << Previous: Finding Qualitative Research Articles

- Next: Mixed Methods Research >>

- Last Updated: Aug 28, 2023 2:47 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.gonzaga.edu/qualitative

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 22, Issue 1

- How to appraise qualitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Calvin Moorley 1 ,

- Xabi Cathala 2

- 1 Nursing Research and Diversity in Care, School of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- 2 Institute of Vocational Learning , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Calvin Moorley, Nursing Research and Diversity in Care, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London SE1 0AA, UK; Moorleyc{at}lsbu.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2018-103044

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

In order to make a decision about implementing evidence into practice, nurses need to be able to critically appraise research. Nurses also have a professional responsibility to maintain up-to-date practice. 1 This paper provides a guide on how to critically appraise a qualitative research paper.

What is qualitative research?

- View inline

Useful terms

Some of the qualitative approaches used in nursing research include grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, case study (can lend itself to mixed methods) and narrative analysis. The data collection methods used in qualitative research include in depth interviews, focus groups, observations and stories in the form of diaries or other documents. 3

Authenticity

Title, keywords, authors and abstract.

In a previous paper, we discussed how the title, keywords, authors’ positions and affiliations and abstract can influence the authenticity and readability of quantitative research papers, 4 the same applies to qualitative research. However, other areas such as the purpose of the study and the research question, theoretical and conceptual frameworks, sampling and methodology also need consideration when appraising a qualitative paper.

Purpose and question

The topic under investigation in the study should be guided by a clear research question or a statement of the problem or purpose. An example of a statement can be seen in table 2 . Unlike most quantitative studies, qualitative research does not seek to test a hypothesis. The research statement should be specific to the problem and should be reflected in the design. This will inform the reader of what will be studied and justify the purpose of the study. 5

Example of research question and problem statement

An appropriate literature review should have been conducted and summarised in the paper. It should be linked to the subject, using peer-reviewed primary research which is up to date. We suggest papers with a age limit of 5–8 years excluding original work. The literature review should give the reader a balanced view on what has been written on the subject. It is worth noting that for some qualitative approaches some literature reviews are conducted after the data collection to minimise bias, for example, in grounded theory studies. In phenomenological studies, the review sometimes occurs after the data analysis. If this is the case, the author(s) should make this clear.

Theoretical and conceptual frameworks

Most authors use the terms theoretical and conceptual frameworks interchangeably. Usually, a theoretical framework is used when research is underpinned by one theory that aims to help predict, explain and understand the topic investigated. A theoretical framework is the blueprint that can hold or scaffold a study’s theory. Conceptual frameworks are based on concepts from various theories and findings which help to guide the research. 6 It is the researcher’s understanding of how different variables are connected in the study, for example, the literature review and research question. Theoretical and conceptual frameworks connect the researcher to existing knowledge and these are used in a study to help to explain and understand what is being investigated. A framework is the design or map for a study. When you are appraising a qualitative paper, you should be able to see how the framework helped with (1) providing a rationale and (2) the development of research questions or statements. 7 You should be able to identify how the framework, research question, purpose and literature review all complement each other.

There remains an ongoing debate in relation to what an appropriate sample size should be for a qualitative study. We hold the view that qualitative research does not seek to power and a sample size can be as small as one (eg, a single case study) or any number above one (a grounded theory study) providing that it is appropriate and answers the research problem. Shorten and Moorley 8 explain that three main types of sampling exist in qualitative research: (1) convenience (2) judgement or (3) theoretical. In the paper , the sample size should be stated and a rationale for how it was decided should be clear.

Methodology

Qualitative research encompasses a variety of methods and designs. Based on the chosen method or design, the findings may be reported in a variety of different formats. Table 3 provides the main qualitative approaches used in nursing with a short description.

Different qualitative approaches

The authors should make it clear why they are using a qualitative methodology and the chosen theoretical approach or framework. The paper should provide details of participant inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as recruitment sites where the sample was drawn from, for example, urban, rural, hospital inpatient or community. Methods of data collection should be identified and be appropriate for the research statement/question.

Data collection

Overall there should be a clear trail of data collection. The paper should explain when and how the study was advertised, participants were recruited and consented. it should also state when and where the data collection took place. Data collection methods include interviews, this can be structured or unstructured and in depth one to one or group. 9 Group interviews are often referred to as focus group interviews these are often voice recorded and transcribed verbatim. It should be clear if these were conducted face to face, telephone or any other type of media used. Table 3 includes some data collection methods. Other collection methods not included in table 3 examples are observation, diaries, video recording, photographs, documents or objects (artefacts). The schedule of questions for interview or the protocol for non-interview data collection should be provided, available or discussed in the paper. Some authors may use the term ‘recruitment ended once data saturation was reached’. This simply mean that the researchers were not gaining any new information at subsequent interviews, so they stopped data collection.

The data collection section should include details of the ethical approval gained to carry out the study. For example, the strategies used to gain participants’ consent to take part in the study. The authors should make clear if any ethical issues arose and how these were resolved or managed.

The approach to data analysis (see ref 10 ) needs to be clearly articulated, for example, was there more than one person responsible for analysing the data? How were any discrepancies in findings resolved? An audit trail of how the data were analysed including its management should be documented. If member checking was used this should also be reported. This level of transparency contributes to the trustworthiness and credibility of qualitative research. Some researchers provide a diagram of how they approached data analysis to demonstrate the rigour applied ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Example of data analysis diagram.

Validity and rigour

The study’s validity is reliant on the statement of the question/problem, theoretical/conceptual framework, design, method, sample and data analysis. When critiquing qualitative research, these elements will help you to determine the study’s reliability. Noble and Smith 11 explain that validity is the integrity of data methods applied and that findings should accurately reflect the data. Rigour should acknowledge the researcher’s role and involvement as well as any biases. Essentially it should focus on truth value, consistency and neutrality and applicability. 11 The authors should discuss if they used triangulation (see table 2 ) to develop the best possible understanding of the phenomena.

Themes and interpretations and implications for practice

In qualitative research no hypothesis is tested, therefore, there is no specific result. Instead, qualitative findings are often reported in themes based on the data analysed. The findings should be clearly linked to, and reflect, the data. This contributes to the soundness of the research. 11 The researchers should make it clear how they arrived at the interpretations of the findings. The theoretical or conceptual framework used should be discussed aiding the rigour of the study. The implications of the findings need to be made clear and where appropriate their applicability or transferability should be identified. 12

Discussions, recommendations and conclusions

The discussion should relate to the research findings as the authors seek to make connections with the literature reviewed earlier in the paper to contextualise their work. A strong discussion will connect the research aims and objectives to the findings and will be supported with literature if possible. A paper that seeks to influence nursing practice will have a recommendations section for clinical practice and research. A good conclusion will focus on the findings and discussion of the phenomena investigated.

Qualitative research has much to offer nursing and healthcare, in terms of understanding patients’ experience of illness, treatment and recovery, it can also help to understand better areas of healthcare practice. However, it must be done with rigour and this paper provides some guidance for appraising such research. To help you critique a qualitative research paper some guidance is provided in table 4 .

Some guidance for critiquing qualitative research

- ↵ Nursing and Midwifery Council . The code: Standard of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives . 2015 https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf ( accessed 21 Aug 18 ).

- Barrett D ,

- Cathala X ,

- Shorten A ,

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Critical Appraisal Tools

Jbi’s critical appraisal tools assist in assessing the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers..

These tools have been revised. Recently published articles detail the revision.

"Assessing the risk of bias of quantitative analytical studies: introducing the vision for critical appraisal within JBI systematic reviews"

"revising the jbi quantitative critical appraisal tools to improve their applicability: an overview of methods and the development process".

End to end support for developing systematic reviews

Analytical Cross Sectional Studies

Checklist for analytical cross sectional studies, how to cite, associated publication(s), case control studies , checklist for case control studies, case reports , checklist for case reports, case series , checklist for case series.

Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, Stephenson M, Aromataris E. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2020;18(10):2127-2133

Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool

Cohort studies , checklist for cohort studies, diagnostic test accuracy studies , checklist for diagnostic test accuracy studies.

Campbell JM, Klugar M, Ding S, Carmody DP, Hakonsen SJ, Jadotte YT, White S, Munn Z. Chapter 9: Diagnostic test accuracy systematic reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020

JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis

Chapter 9: Diagnostic test accuracy systematic reviews

Economic Evaluations

Checklist for economic evaluations, prevalence studies , checklist for prevalence studies.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020

Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence

Qualitative Research

Checklist for qualitative research.

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179–187

Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence

Qualitative research synthesis

Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation

Quasi-Experimental Studies

Checklist for quasi-experimental studies.

Barker TH, Habibi N, Aromataris E, Stone JC, Leonardi-Bee J, Sears K, et al. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias quasi-experimental studies. JBI Evid Synth. 2024;22(3):378-88.

The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for quasi-experimental studies

Randomized controlled trials , randomized controlled trials.

Barker TH, Stone JC, Sears K, Klugar M, Tufanaru C, Leonardi-Bee J, Aromataris E, Munn Z. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomized controlled trials. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2023;21(3):494-506

The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomized controlled trials

Randomized controlled trials checklist (archive), systematic reviews , checklist for systematic reviews.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Kahlil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an Umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132-40.

Chapter 10: Umbrella Reviews

Textual Evidence: Expert Opinion

Checklist for textual evidence: expert opinion.

McArthur A, Klugarova J, Yan H, Florescu S. Chapter 4: Systematic reviews of text and opinion. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020

Chapter 4: Systematic reviews of text and opinion

Textual Evidence: Narrative

Checklist for textual evidence: narrative, textual evidence: policy , checklist for textual evidence: policy.

FEEDING YOUR QUALITATIVE NEEDS

Have you ever searched "free qualitative research software" only to be disappointed that nothing lets you tag your materials? Search no more! Taguette is a free and open-source tool for qualitative research. You can import your research materials, highlight and tag quotes, and export the results!

Learn more » Try out Taguette on our server

Work Locally

Taguette works both on your local computer (macOS, Windows, Linux) and on a server. When running Taguette locally, your data is as secure as your computer . That means that if you can have your data on your computer, you can run Taguette with no worries.

Install now »

Highlight & Tag

Taguette allows you to upload your research materials and tag them, just as you would use different color highlighters with printed paper. You can add new tags, then just select some text, click 'new highlight', and add whatever tag you find to be most relevant!

Get started »

Export Results

After you've done your work highlighting materials in Taguette, you can export in a variety of ways -- your whole project, codebook, all your highlighted quotes (or ones for a specific tag!), and highlighted documents. It's a good practice to keep an archival copy of your work!

View details »

Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

Critical Appraisal tools

Critical appraisal worksheets to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence.

Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of clinical research papers in order to establish:

- Does this study address a clearly focused question ?

- Did the study use valid methods to address this question?

- Are the valid results of this study important?

- Are these valid, important results applicable to my patient or population?

If the answer to any of these questions is “no”, you can save yourself the trouble of reading the rest of it.

This section contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples.

Critical Appraisal Worksheets

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostics Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet

- IPD Review Sheet

Chinese - translated by Chung-Han Yang and Shih-Chieh Shao

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostic Study Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognostic Critical Appraisal Sheet

- RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

- IPD reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Qualitative Studies Critical Appraisal Sheet

German - translated by Johannes Pohl and Martin Sadilek

- Systematic Review Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Therapy / RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

Lithuanian - translated by Tumas Beinortas

- Systematic review appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Diagnostic accuracy appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Prognostic study appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- RCT appraisal sheets Lithuanian (PDF)

Portugese - translated by Enderson Miranda, Rachel Riera and Luis Eduardo Fontes

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Diagnostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Prognostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – RCT Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Evaluation of Individual Participant Data Worksheet

- Portuguese – Qualitative Studies Evaluation Worksheet

Spanish - translated by Ana Cristina Castro

- Systematic Review (PDF)

- Diagnosis (PDF)

- Prognosis Spanish Translation (PDF)

- Therapy / RCT Spanish Translation (PDF)

Persian - translated by Ahmad Sofi Mahmudi

- Prognosis (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (MS-Word)

- Educational Prescription Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

Explanations & Examples

- Pre-test probability

- SpPin and SnNout

- Likelihood Ratios

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Critical Appraisal Checklists. We offer a number of free downloadable checklists to help you more easily and accurately perform critical appraisal across a number of different study types. The CASP checklists are easy to understand but in case you need any further guidance on how they are structured, take a look at our guide on how to use our ...

Qualitative evidence allows researchers to analyse human experience and provides useful exploratory insights into experiential matters and meaning, often explaining the 'how' and 'why'. As we have argued previously1, qualitative research has an important place within evidence-based healthcare, contributing to among other things policy on patient safety,2 prescribing,3 4 and ...

More. Critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines are the two most important instruments available to researchers and practitioners involved in research, evidence-based practice, and policymaking. Each of these instruments has unique characteristics, and both instruments play an essential role in evidence-based practice and decision-making.

Qualitative research has an important place within evidence-based health care (EBHC), contributing to policy on patient safety and quality of care, supporting understanding of the impact of chronic illness, and explaining contextual factors surrounding the implementation of interventions. However, the question of whether, when and how to critically appraise qualitative research persists ...

A key stage common to all systematic reviews is quality appraisal of the evidence to be synthesized. 1,8 There is broad debate and little consensus among the academic community over what constitutes 'quality' in qualitative research. 'Qualitative' is an umbrella term that encompasses a diverse range of methods, which makes it difficult to have a 'one size fits all' definition of ...

for Qualitative Research 4 Discussion of Critical Appraisal Criteria How to cite: Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179-187. 1.

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then ...

More than 100 critical appraisal tools currently exist for qualitative research. Tools fall into two categories: checklists and holistic ... Gavin, A., Bruchez, C., Roux, P., & Stephen, S. (2016). Quality of qualitative research in the health sciences: Analysis of the common criteria present in 58 assessment guidelines by expert users. ...

SPIDER for Mixed Methods Qualitative Research Questions; ... Tools for Critical Appraisal. CASP: Qualitative Research Studies. Joanna Briggs Institute: Checklist for Qualitative Research. McMaster Critical Review Form: Qualitative Research. SURE for Qualitative Studies << Previous: Finding Qualitative Research Articles;

The CASP qualitative research checklist poses 10 questions in total with space provided to record comments by the appraiser. 22 This tool is commonly used when appraising studies for inclusion in qualitative evidence syntheses, has been endorsed by Cochrane and the World Health Organization, and is relatively easy for clinicians new to ...

In critically appraising qualitative research, steps need to be taken to ensure its rigour, credibility and trustworthiness ( table 1 ). Some of the qualitative approaches used in nursing research include grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, case study (can lend itself to mixed methods) and narrative analysis.

Qualitative research is defined as "the study of the nature of phenomena", including "their quality, ... It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) . Open in a separate window. Fig. 3. From data collection to data analysis. Attributions for icons: see Fig. ...

Procedures and tools ibr data gathering are subject to ongoing revision in the field situation Analysis is presented for the most part in a narrative rather than numericai Form, but the inclusion of some quantitative measures and numerical expressions Is not precluded in qualitative research Credibility, transferabiiity (fittingness ...

For many researchers unfamiliar with qualitative research, determining how to conduct qualitative analyses is often quite challenging. Part of this challenge is due to the seemingly limitless approaches that a qualitative researcher might leverage, as well as simply learning to think like a qualitative researcher when analyzing data. From framework analysis (Ritchie & Spencer, 1994) to content ...

The systematic review is essentially an analysis of the available literature (that is, evidence) and a. judgment of the effectiveness or otherwise of a practice, involving a series of complex steps. JBI takes a. particular view on what counts as evidence and the methods utilised to synthesise those different types of. evidence.

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179-187 ... Sears K, Klugar M, Tufanaru C, Leonardi-Bee J, Aromataris E, Munn Z. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for ...

APPRAISING THE RESEARCH EVIDENCE. Some aspects of appraising a research article are the same whether the study is quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods (Dale, 2005, Gray and Grove, 2017).Caldwell, Henshaw, and Taylor (2011) described the development of a framework for critiquing health research, addressing both quantitative and qualitative research with one list of questions.

Critical analysis of a qualitative study involves an in-depth review of how each step of the research was undertaken, and nurses need to be able to determine the strengths and limitations of qualitative as well as quantitative research studies when reviewing the available literature on a topic. As with a quantitative study, critical analysis of a qualitative study involves an in-depth review ...

Taguette is a free an open-source text tagging tool for qualitative data analysis and qualitative research. Taguette. Home (current) About ... Taguette is a free and open-source tool for qualitative research. You can import your research materials, highlight and tag quotes, and export the results!

The empirical research reflected descriptive and/or qualitative approaches, these being critical review of existing tools [40,72], Delphi techniques to identify then refine data items [32,51,71], questionnaires and other forms of written surveys to identify and refine data items [70,79,103], facilitated structured consensus meetings [20,29,30 ...

This section contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples. Critical appraisal worksheets to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence.

This commentary is based on a presentation given at the annual meeting of the Coalition for Critical Qualitative Research at the 19th International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry. ... The tool in question was developed in a Western context, and the researchers had attempted to use it in a non-Western community but were met with some resistance ...

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research. Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research, which involves collecting and ...

The narrative findings in this qualitative study offer context-sensitive information for developing out-of-hospital overdose scenarios applicable to simulation training. These insights can serve as a valuable resource, aiding instructors and researchers in systematically creating evidence-based scenarios for both training and research purposes.