- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Quantitative Research in Communication

- Mike Allen - University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee, USA

- Scott Titsworth - Ohio University, USA

- Stephen K. Hunt - Illinois State University, USA

- Description

Written for communication students, Quantitative Research in Communication provides practical, user-friendly coverage of how to use statistics, how to interpret SPSS printouts, how to write results, and how to assess whether the assumptions of various procedures have been met. Providing a strong conceptual orientation to techniques and procedures that range from the "moderately basic" to "highly advanced," the book provides practical tips and suggestions for quantitative communication scholars of all experience levels. In addition to important foundational information, each chapter that covers a specific statistical procedure includes suggestions for interpreting, explaining, and presenting results; realistic examples of how the procedure can be used to answer substantive questions in communication; sample SPSS printouts; and a detailed summary of a published communication journal article using that procedure.

· Engaged Research application boxes stimulate thought and discussion, illustrating how particular research methods can be used to answer very practical, civic-minded questions.

· Realistic examples at the beginning of each chapter show how the chapter's procedure could be used to answer a substantive research question.

· Examples and application activities geared toward the emerging trend of service learning encourage students to do projects oriented toward their community or campus.

· Summaries of journal articles demonstrate how to write statistical results in APA style and illustrate how real researchers use statistical procedures in a wide variety of contexts, such as tsunami warnings, date requests, and anti-drug public service announcements.

· How to Decipher Figures show students how to "read" the statistical shorthand presented in the quantitative results of an article and also, by implication, show them how to write up results .

Quantitative Research in Communication is ideal for courses in Quantitative Methods in Communication, Statistical Methods in Communication, Advanced Research Methods (undergraduate), and Introduction to Research Methods (Graduate) in departments of communication, educational psychology, psychology, and mass communication.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

This is an excellent book. My students love it.

I particularly like the chapter on meta-analysis as this is one topic that most of the books on survey that I have been using do not discuss.

Guide to Communication Research Methodologies: Quantitative, Qualitative and Rhetorical Research

Overview of Communication

Communication research methods, quantitative research, qualitative research, rhetorical research, mixed methodology.

Students interested in earning a graduate degree in communication should have at least some interest in understanding communication theories and/or conducting communication research. As students advance from undergraduate to graduate programs, an interesting change takes place — the student is no longer just a repository for knowledge. Rather, the student is expected to learn while also creating knowledge. This new knowledge is largely generated through the development and completion of research in communication studies. Before exploring the different methodologies used to conduct communication research, it is important to have a foundational understanding of the field of communication.

Defining communication is much harder than it sounds. Indeed, scholars have argued about the topic for years, typically differing on the following topics:

- Breadth : How many behaviors and actions should or should not be considered communication.

- Intentionality : Whether the definition includes an intention to communicate.

- Success : Whether someone was able to effectively communicate a message, or merely attempted to without it being received or understood.

However, most definitions discuss five main components, which include: sender, receiver, context/environment, medium, and message. Broadly speaking, communication research examines these components, asking questions about each of them and seeking to answer those questions.

As students seek to answer their own questions, they follow an approach similar to most other researchers. This approach proceeds in five steps: conceptualize, plan and design, implement a methodology, analyze and interpret, reconceptualize.

- Conceptualize : In the conceptualization process, students develop their area of interest and determine if their specific questions and hypotheses are worth investigating. If the research has already been completed, or there is no practical reason to research the topic, students may need to find a different research topic.

- Plan and Design : During planning and design students will select their methods of evaluation and decide how they plan to define their variables in a measurable way.

- Implement a Methodology : When implementing a methodology, students collect the data and information they require. They may, for example, have decided to conduct a survey study. This is the step when they would use their survey to collect data. If students chose to conduct a rhetorical criticism, this is when they would analyze their text.

- Analyze and Interpret : As students analyze and interpret their data or evidence, they transform the raw findings into meaningful insights. If they chose to conduct interviews, this would be the point in the process where they would evaluate the results of the interviews to find meaning as it relates to the communication phenomena of interest.

- Reconceptualize : During reconceptualization, students ask how their findings speak to a larger body of research — studies related to theirs that have already been completed and research they should execute in the future to continue answering new questions.

This final step is crucial, and speaks to an important tenet of communication research: All research contributes to a better overall understanding of communication and moves the field forward by enabling the development of new theories.

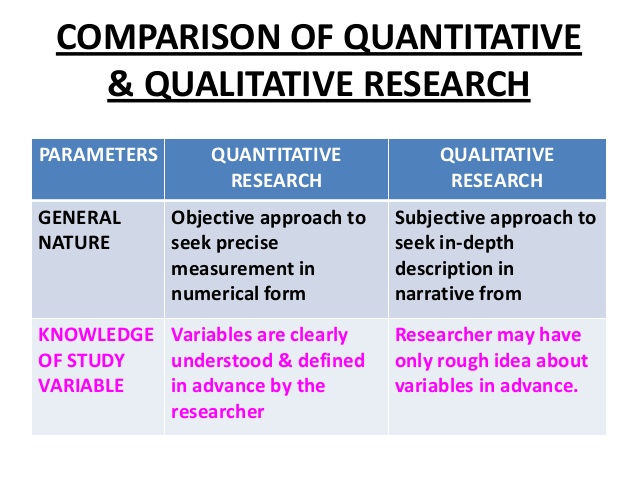

In the field of communication, there are three main research methodologies: quantitative, qualitative, and rhetorical. As communication students progress in their careers, they will likely find themselves using one of these far more often than the others.

Quantitative research seeks to establish knowledge through the use of numbers and measurement. Within the overarching area of quantitative research, there are a variety of different methodologies. The most commonly used methodologies are experiments, surveys, content analysis, and meta-analysis. To better understand these research methods, you can explore the following examples:

Experiments : Experiments are an empirical form of research that enable the researcher to study communication in a controlled environment. For example, a researcher might know that there are typical responses people use when they are interrupted during a conversation. However, it might be unknown as to how frequency of interruption provokes those different responses (e.g., do communicators use different responses when interrupted once every 10 minutes versus once per minute?). An experiment would allow a researcher to create these two environments to test a hypothesis or answer a specific research question. As you can imagine, it would be very time consuming — and probably impossible — to view this and measure it in the real world. For that reason, an experiment would be perfect for this research inquiry.

Surveys : Surveys are often used to collect information from large groups of people using scales that have been tested for validity and reliability. A researcher might be curious about how a supervisor sharing personal information with his or her subordinate affects way the subordinate perceives his or her supervisor. The researcher could create a survey where respondents answer questions about a) the information their supervisors self-disclose and b) their perceptions of their supervisors. The data collected about these two variables could offer interesting insights about this communication. As you would guess, an experiment would not work in this case because the researcher needs to assess a real relationship and they need insight into the mind of the respondent.

Content Analysis : Content analysis is used to count the number of occurrences of a phenomenon within a source of media (e.g., books, magazines, commercials, movies, etc.). For example, a researcher might be interested in finding out if people of certain races are underrepresented on television. They might explore this area of research by counting the number of times people of different races appear in prime time television and comparing that to the actual proportions in society.

Meta-Analysis : In this technique, a researcher takes a collection of quantitative studies and analyzes the data as a whole to get a better understanding of a communication phenomenon. For example, a researcher might be curious about how video games affect aggression. This researcher might find that many studies have been done on the topic, sometimes with conflicting results. In their meta-analysis, they could analyze the existing statistics as a whole to get a better understanding of the relationship between the two variables.

Qualitative research is interested in exploring subjects’ perceptions and understandings as they relate to communication. Imagine two researchers who want to understand student perceptions of the basic communication course at a university. The first researcher, a quantitative researcher, might measure absences to understand student perception. The second researcher, a qualitative researcher, might interview students to find out what they like and dislike about a course. The former is based on hard numbers, while the latter is based on human experience and perception.

Qualitative researchers employ a variety of different methodologies. Some of the most popular are interviews, focus groups, and participant observation. To better understand these research methods, you can explore the following examples:

Interviews : This typically consists of a researcher having a discussion with a participant based on questions developed by the researcher. For example, a researcher might be interested in how parents exert power over the lives of their children while the children are away at college. The researcher could spend time having conversations with college students about this topic, transcribe the conversations and then seek to find themes across the different discussions.

Focus Groups : A researcher using this method gathers a group of people with intimate knowledge of a communication phenomenon. For example, if a researcher wanted to understand the experience of couples who are childless by choice, he or she might choose to run a series of focus groups. This format is helpful because it allows participants to build on one another’s experiences, remembering information they may otherwise have forgotten. Focus groups also tend to produce useful information at a higher rate than interviews. That said, some issues are too sensitive for focus groups and lend themselves better to interviews.

Participant Observation : As the name indicates, this method involves the researcher watching participants in their natural environment. In some cases, the participants may not know they are being studied, as the researcher fully immerses his or herself as a member of the environment. To illustrate participant observation, imagine a researcher curious about how humor is used in healthcare. This researcher might immerse his or herself in a long-term care facility to observe how humor is used by healthcare workers interacting with patients.

Rhetorical research (or rhetorical criticism) is a form of textual analysis wherein the researcher systematically analyzes, interprets, and critiques the persuasive power of messages within a text. This takes on many forms, but all of them involve similar steps: selecting a text, choosing a rhetorical method, analyzing the text, and writing the criticism.

To illustrate, a researcher could be interested in how mass media portrays “good degrees” to prospective college students. To understand this communication, a rhetorical researcher could take 30 articles on the topic from the last year and write a rhetorical essay about the criteria used and the core message argued by the media.

Likewise, a researcher could be interested in how women in management roles are portrayed in television. They could select a group of popular shows and analyze that as the text. This might result in a rhetorical essay about the behaviors displayed by these women and what the text says about women in management roles.

As a final example, one might be interested in how persuasion is used by the president during the White House Correspondent’s Dinner. A researcher could select several recent presidents and write a rhetorical essay about their speeches and how they employed persuasion during their delivery.

Taking a mixed methods approach results in a research study that uses two or more techniques discussed above. Often, researchers will pair two methods together in the same study examining the same phenomenon. Other times, researchers will use qualitative methods to develop quantitative research, such as a researcher who uses a focus group to discuss the validity of a survey before it is finalized.

The benefit of mixed methods is that it offers a richer picture of a communication phenomenon by gathering data and information in multiple ways. If we explore some of the earlier examples, we can see how mixed methods might result in a better understanding of the communication being studied.

Example 1 : In surveys, we discussed a researcher interested in understanding how a supervisor sharing personal information with his or her subordinate affects the way the subordinate perceives his or her supervisor. While a survey could give us some insight into this communication, we could also add interviews with subordinates. Exploring their experiences intimately could give us a better understanding of how they navigate self-disclosure in a relationship based on power differences.

Example 2 : In content analysis, we discussed measuring representation of different races during prime time television. While we can count the appearances of members of different races and compare that to the composition of the general population, that doesn’t tell us anything about their portrayal. Adding rhetorical criticism, we could talk about how underrepresented groups are portrayed in either a positive or negative light, supporting or defying commonly held stereotypes.

Example 3 : In interviews, we saw a researcher who explored how power could be exerted by parents over their college-age children who are away at school. After determining the tactics used by parents, this interview study could have a phase two. In this phase, the researcher could develop scales to measure each tactic and then use those scales to understand how the tactics affect other communication constructs. One could argue, for example, that student anxiety would increase as a parent exerts greater power over that student. A researcher could conduct a hierarchical regression to see how each power tactic effects the levels of stress experienced by a student.

As you can see, each methodology has its own merits, and they often work well together. As students advance in their study of communication, it is worthwhile to learn various research methods. This allows them to study their interests in greater depth and breadth. Ultimately, they will be able to assemble stronger research studies and answer their questions about communication more effectively.

Note : For more information about research in the field of communication, check out our Guide to Communication Research and Scholarship .

Approaches to Research on L2 Oral Communication

- First Online: 10 November 2020

Cite this chapter

- Alireza Jamshidnejad 2 ,

- Reza Falahati 3 &

- Etske Ooijevaar 4

930 Accesses

This chapter first presents the three main approaches in studying L2 oral communication and speaking: qualitative, quantitative and mixed. It shows how the main trends in the field have shifted from a quantitative into a qualitative approach and more recently to mixed approaches. Next, the techniques used for collecting data in these different types of research are presented. The subsequent section of this chapter discusses the production and perception aspects of research on pronunciation, followed by a presentation of innovative approaches to research on pronunciation. This includes developing models which are representative of an authentic and ‘international’ accent as well as using ultrasound, as a new channel for signals, for teaching pronunciation. The concluding section of this chapter presents tasks and techniques for eliciting oral data.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

See Creswell, Clark, Gutmann, and Hanson ( 2003 ) for other terms used to refer to this type of research.

Anderson, A. H., Bader, M., Bard, E. G., Boyle, E. H., Doherty, G. M., Garrod, S. C., … Weinert, R. (1991). The HCRC map task corpus. Language and Speech, 34 (4), 351–366.

Google Scholar

Anderson, G., Herr, K., & Nihlen, A. (1994). Studying your own school: An educator’s guide to qualitative practitioner research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Baker, R. E., & Hazan, V. (2011). DiapixUK: Task materials for the elicitation of multiple spontaneous speech dialogs. Behavioral Research, 43, 761–770.

Article Google Scholar

Barton, K. C. (2015). Elicitation techniques: Getting people to talk about ideas they don’t usually talk about. Theory and Research in Social Education, 43 (2), 179–205.

Bejarano, Y., Levine, T., Olshtain, E., & Steiner, J. (1997). The skilled use of interaction strategies: Creating a framework for improved small-group communicative interaction in the language classroom. System, 25 (2), 203–214.

Bel, N. (2015). A continuum of speech: The difference between speech in conversation, interview, and lecture (MA thesis). Tilburg University.

Best, C. T. (1995). A direct realist view of cross-language speech perception. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 171–204). Timonium, MD: York Press.

Bialystok, E. (1990). Communication strategies: A psychological analysis of second language use . Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Billmyer, K., & Varghese, M. (2000). Investigating instrument-based pragmatic variability: Effects of enhancing discourse completion tests. Applied Linguistics, 21 (4), 517–552.

Block, D. (2003). The social turn in second language acquisition . Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (1989). Investigating cross-cultural pragmatics: An introductory overview. In S. Blum-Kulka, J. House, & G. Kasper (Eds.), Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies (pp. 1–34). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Boxer, D. (2004). Studying speaking to inform second language learning: A conceptual overview. In D. Boxer & A. D. Cohen (Eds.), Studying speaking to inform second language learning (pp. 3–24). Clevedon, Buffalo, and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Bradlow, A. R. (2008). Training non-native language sound patterns: Lessons from training Japanese adults on the English /r/ - /l/ contrast. In Studies in bilingualism phonology and second language acquisition (pp. 287–308). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Brown, G., Anderson, A. H., Yule, G., & Shillcock, R. (1983). Teaching talk . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, J. D. (2004). Research methods for applied linguistics: Scope, characteristics, and standards. In A. Davies & C. Elder (Eds.), The handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 476–499). Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell.

Chapter Google Scholar

Burdine, S. R. (2002). Means to an end: Communication strategies in french immersion (Unpublished PhD). Rice University, NDLTD Union Catalog, United States. Retrieved (10 October 2019) from http://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/18068 .

Carlet, A., & Cebrian, J. (2019). Assessing the effect of perceptual training on L2 vowel identification, generalisation and long-term effects. In A sound approach to language matters: In Honor of Ocke-Schwen Bohn (pp. 91–119). Aarhus: Department of English, School of Communication & Culture, Aarhus University.

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D. M., Goodwin, J. M., & Griner, B. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A reference for teachers of English to speakers of other languages (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, A., & Kager, R. (2011). The perception of lexical tones and tone sandhi in l2: Success or failure? ICPHS (pp. 444–447).

Collentine, J., & Freed, B. F. (2004). Learning context and its effects on second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26, 153–171.

Corder, S. P. (1983). Strategies of communication. In C. Færch & G. Kasper (Eds.), Strategies in interlanguage communication (pp. 15–19). London: Longman.

Cotton, S., & Grosjean, F. (1984). The gating paradigm: A comparison of successive and individual presentation formats. Perception and Psychophysics, 35 (1), 41–48.

Coulthard, M., & Brazil, D. (2002). Exchange structure. In M. Coulthard (Ed.), Advances in spoken discourse analysis (pp. 50–78). London and New York: Routledge.

Creswell, J., Clark, V., Gutmann, M., & Hanson, W. (2003). Advance mixed methods research designs. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 209–240). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cunningham, D. (2006). Capturing candor: Accessing teachers’ thinking about the cultivation of historical empathy. In K. C. Barton (Ed.), Research methods in social studies education: Contemporary issues and perspectives (pp. 183–206). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Dellwo, V., Leemann, A., & Kolly, M.-J. (2015). The recognition of read and spontaneous speech in local vernacular: The case of Zurich German. Journal of Phonetics, 48, 13–28.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). London and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Derwing, T. M. (2003). What do ESL students say about their accents? Canadian Modern Language Review, 59, 547–567.

Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M. J. (1997). Accent, intelligibility, and comprehensibility: Evidence from Four L1s. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19 (1), 1–16.

Díaz, B., Mitterer, H., Broersma, M., & Sebastián-Gallés, N. (2012). Individual differences in Late bilinguals’ L2 phonological processes: From acoustic-phonetic analysis to lexical access. Learning and Individual Differences, 22 (6), 680–689.

Dobao, A. M. F. (2001). Communication strategies in the interlanguage of Galician students of English: The influence of learner-and task-related factors. Atlantis‚ 23 (1)‚ 41–62.

Dobao, A. M. F., & Martínez, I. M. P. (2007). Negotiating meaning in interaction between English and Spanish speakers via communicative strategies. Atlantis, 29 (1), 87–105.

Dörnyei, Z. (1995). On the teachability of communication strategies. TESOL Quarterly, 29 (1), 55–86.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Duff, P. A. (2002). Research approaches in applied linguistics. In R. B. Kaplan (Ed.), The oxford handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 13–23). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Færch, C., & Kasper, G. (1983). Plans and strategies in foreign language communication. In C. Færch & G. Kasper (Eds.), Strategies in interlanguage communication (pp. 20–60). London: Longman.

Falahati, R. (2020). The acquisition of segmental and suprasegmental features in second language Persian: A focus on prosodic parameters of politeness. In P. Shabani-Jadidi (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and pedagogy of Persian . Abingdon: Tailor and Francis Group.

Félix-Brasdefer, J. C. (2010). Data collection methods in speech act performance: DCTs, role plays, and verbal reports. In A. Martínez-Flor & E. Usó-Juan (Eds.), Speech act performance: Theoretical, empirical, and methodological issues (pp. 41–56). Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Freeman, D., & Holden, S. (1986). Authentic listening materials. In S. Holden (Ed.), Techniques of teaching (pp. 67–69). London: Modern English Publications.

Fujisaki, H. (1997). Prosody, models, and spontaneous speech. In Y. Sagisaka, N. Campbell, & N. Higuchi (Eds.), Computing prosody. Computational models for processing spontaneous speech (pp. 27–42). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Genhard, J. G. (1996). Teaching English as a foreign language: A teacher self- development and methodology . Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Gick, G., Bernhardt, B., Bacsfalvi, P., & Wilson, I. (2008). Ultrasound imaging applications in second language acquisition. In J. G. Hansen Edwards & M. L. Zampini (Eds.), Phonology and second language acquisition (pp. 309–322). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Gold, R. L. (1958). Roles in sociological field observations. Social Forces, 36 (3), 217–223.

Grosjean, F. (1980). Spoken word recognition processes and the gating paradigm. Perception and Psychophysics, 28 (4), 267–283.

Hardison, D. M. (2004). Generalization of computer-assisted prosody training. Lanuage Learnig & Technology, 8 (1), 34–52.

Hicks, D.‚ & Littlejohn‚ A. (2003). Primary colours activity book 3 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holliday, A. R. (2007). Doing and writing qualitative research (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Hughes, R. (2002). Teaching and researching speaking . London: Longman.

Hughes, R. (2011). Teaching and researching speaking . Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Pearson Education Limited.

Jamshidnejad, A. (2010). Exploring oral communication strategies in an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) context (Unpublished PhD thesis). University of Kent, UK.

Johnson, J. C., & Weller, S. C. (2002). Elicitation techniques for interviewing. In J. F. Gubrium & J. A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context and method (pp. 491–514). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kellerman, E. (1991). Compensatory strategies in second language research: A critique, a revision, and some (non-)implications for the classroom. In R. Phillipson, E. Kellerman, L. Selinker, M. Sharwood Smith, & M. Swain (Eds.), Foreign/second language pedagogy research: A commemorative volume for Claus Færch (pp. 142–161). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Kushch, O., Igualada, A., & Prieto, P. (2018). Prominence in speech and gesture favour second language novel word learning. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 33 (8), 992–1004.

Kwok, B. (1987). A study of the communicative strategies used by sixth-form students in small group discussion (Unpublished manuscript). Retrieved (23 January 2010) from http://sunzi1.lib.hku.hk/hkjo/view/45/4500100.pdf .

Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns . Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.

Lafford, B. A. (2004). The effect of the context of learning on the use of communication strategies by learners of Spanish as a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26 (2), 201–225.

Lam, W. Y. K. (2006). Gauging the effects of ESL oral communication strategy teaching: A multi-method approach. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 3 (2), 142–157.

Little, D., Devitt, S., & Singleton, D. (1989). Learning foreign languages from authentic texts: Theory and practice . Dublin: Authentik.

Little, D., & Singleton, D. (1991). Authentic texts, pedagogical grammar and language awareness in foreign language learning. In C. James & P. Garrett (Eds.), Language awareness in the classroom (pp. 123–132). London: Longman.

Littlemore, J. (2001). An empirical study of the relationship between cognitive style and the use of communication strategy. Applied Linguistics, 22 (2), 241–265.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design . Mahwah, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Martinez, A. G. (2002). Authentic materials: An overview on Karen’s linguistic issues . Retrieved from http://www3.telus.net/linguisticsissues/authenticmaterials.html .

Meadows, B. (2012). Do you see what I’m saying?: Ultrasound technology as a tool for pronunciation instruction. In J. E. Aitken, J. P. Fairley, & J. K. Carlson (Eds.), Communication technology for students in special education and gifted programs (pp. 293–302). USA: Information Science Reference.

Miller, L. (2003). Developing listening skills with authentic materials. ESL Magazine, 6 (1), 16–19.

Morita, N. (2000). Discourse socialization through oral classroom activities in a TESL graduate program. TESOL Quarterly, 34, 279–310.

Morrison, B. (1989). Using news broadcasts for authentic listening comprehension. ELT Journal, 43 (1), 14–18.

Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (1995). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning, 45, 73–97.

Nakahama, Y., Tyler, A., & Van Lier, L. (2001). Negotiation of meaning in conversational and information gap activities: A comparative discourse analysis. TESOL Quarterly, 35 (3), 377–405.

Nakatani, Y. (2005). The effects of awareness-raising training on oral communication strategy use. The Modern Language Journal, 89, 76–91.

Nakatani, Y. (2006). Developing an oral communication strategy inventory. The Modern Language Journal, 90 (2), 151–168.

Nuttall, C. (1996). Teaching reading skills in a foreign language . Oxford: Heinemann.

Paribakht, T. (1985). Strategic competence and language proficiency. Applied Linguistics, 6, 132–146.

Parks, S., & Raymond, P. M. (2004). Strategy use by non-native English speaking students in an MBA program: Not business as usual. The Modern Language Journal, 88 (3), 374–389.

Peacock, M. (1997). The effect of authentic materials on the motivation of EFL learners. ELT Journal, 51 (2), 144–156.

Pennington, M. C., & Rogerson-Revell, P. (2019). English pronunciation teaching and research: Contemporary perspectives . London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Peperkamp, S., & Bouchon, C. (2011). The relation between perception and production in L2 phonological processing. INTERSPEECH , 161–164.

Pica, T., Kanagy, R., & Falodun, J. (1993). Choosing and using communication tasks for second language instruction and research. In G. Crookes & S. Gass (Eds.), Tasks and language learning: Integrating theory and practice (pp. 9–34). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Poulisse, N., Bongaerts, T., & Kellerman, E. (1987). The use of retrospective verbal reports in the analysis of compensatory strategies. In C. Færch & G. Kasper (Eds.), Introspection in second language research (pp. 213–229). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Poulisse, N., Bongaerts, T., & Kellerman, E. (1990). The use of compensatory strategies by Dutch learners of English . Berlin: Mouton de Gruijter.

Rababah, G., & Seedhouse, P. (2004). Communication strategies and message transmission with Arab learners of English in Jordan. ARECLS E-Journal, 1 (A6).

Rampton, B. (1997). A sociolinguistic perspective on L2 communication strategies. In G. Kasper & E. Kellerman (Eds.), Communication strategies: Psycholinguistic and sociolinguistic perspectives (pp. 279–303). London: Longman.

Richards, K. (2003). Qualitative inquiry in TESOL . New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Richards, K. (2009). Trends in qualitative research in language teaching since 2000. Language Teaching, 42 (2), 147–180.

Rose, M. (2010). Intervocalic tap and trill production in the acquisition of Spanish as a second language. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics, 3 (2), 379–419.

Rossiter, M. J. (2009). Perceptions of L2 fluency by native and non-native speakers of English. Canadian Modern Language Review, 65 (3), 395–412.

Saito, K. (2013). Reexamining effects of form-focused instruction on L2 pronunciation development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 35, 1–29.

Schiffrin, D. (1994). Approaches to discourse . Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1994). Second language learning: Theoretical foundations . London: Longman.

Smakman, D. (2019). Second-language sociolinguistics: Globalising pronunciation norms for learners . Talk presented at Sociolinguistic Series, Leiden University.

Strange, W. (1995). Phonetics of second-language acquisition: Past, present, future. In K. Elenius & P. Branderud (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1995 international congress of phonetic sciences. Stockholm: Arne Stomberg.

Tarone, E., & Yule, G. (1987). Communication strategies in east-west interactions. In L. E. Smith (Ed.), Discourse across cultures: Strategies in world Englishes (pp. 49–65). New York: Prentice-Hall.

Tremblay, Annie. (2009). Phonetic variability and the variable perception of L2 word stress by French Canadian listeners. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13, 35–62.

Trimble, J. C. (2013). Perceiving intonational cues in a foreign language: Perception of sentence type in two dialects of Spanish. In Selected proceedings of the 15th hispanic linguistics symposium (pp. 78-92).

Tsui, H. M. (2012). Ultrasound speech training for Japanese adults learning English as a second language (Unpublished MSc thesis). University of British Columbia.

Tyler, M. D., Best, C. T., Faber, A., & Levitt, A. (2014). Perceptual assimilation and discrimination of non-native vowel contrasts. Phonetica, 71 (1), 4–21.

Van Engen, K. J., Baese-Berk, M., Baker, R. E., Choi, A., Kim, M., & Bradlow, A. R. (2010). The wildcat corpus of native-and foreign-accented English: Communicative efficiency across conversational dyads with varying language alignment profiles. Language and Speech, 53, 510–540.

Wilson, I. (2014). Using ultrasound for teaching and researching articulation. Acoustical Science and Technology, 35 (6), 285–288.

Wongsawang, P. (2001). Culture-specific notions in L2 communication strategies. Second Language Studies, 19 (2), 111–135.

Yule, G. (1991). Developing communicative effectiveness through the negotiated resolution of referential conflicts. Linguistics and Education, 3, 31–45.

Yule, G., & Macdonald, D. (1990). Resolving referential conflicts in L2 interaction: The effect of proficiency and interactive role. Language Learning, 40 (4), 539–556.

Yule, G., Powers, M., & Macdonald, D. (1992). The variable effects of some task-based learning procedures on L2 communicative effectiveness. Language Learning, 42 (2), 249–277.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English Language, College of Education, University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Rustaq, Oman

Alireza Jamshidnejad

Centre for Linguistics, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands

Reza Falahati

Meertens Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Etske Ooijevaar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Reza Falahati .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Jamshidnejad, A., Falahati, R., Ooijevaar, E. (2020). Approaches to Research on L2 Oral Communication. In: Jamshidnejad, A. (eds) Speaking English as a Second Language. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55057-8_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55057-8_6

Published : 10 November 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-55056-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-55057-8

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 08 February 2005

A quantitative survey of intern's knowledge of communication skills: an Iranian exploration

- Mohsen Tavakol 1 ,

- Sima Torabi 2 ,

- Owen D Lyne 3 &

- Ali A Zeinaloo 4

BMC Medical Education volume 5 , Article number: 6 ( 2005 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

11 Citations

Metrics details

It is a high priority that health care providers have effective communication skills. It has been well documented that the doctor-patient relationship is central to the delivery of high quality medical care, and it has been shown to affect patient satisfaction, to decrease the use of pain killers, to shorten hospital stays, to improve recovery from surgery and a variety of other biological, psychological and social outcomes. This study sought to quantify the current knowledge of interns in Iran about communication skills.

A cross-sectional study using a self-report questionnaire was conducted among interns. Data analysis was based on 223 questionnaires. The internal consistency of the items was 0.8979.

Overall, knowledge levels were unsatisfactory. Results indicated that interns had a limited knowledge of communication skills, including identification of communication skills. In addition, there was a significant difference between the mean scores of interns on breaking bad news and sex education. The confidence of males about their communication skills was significantly higher than for females. Analysis of the total scores by age and sex showed that there was a statistically significant main effect for sex and the interaction with age was statistically significant. Free response comments of the interns are also discussed.

Conclusions

It is argued that there is a real need for integrating a communication skills course, which is linked to the various different ethnic and religious backgrounds of interns, into Iranian medical curricula. Some recommendations are made and the limitations of the study are discussed.

Peer Review reports

The expectations of the public have been dramatically increased and the majority of them are familiar with their rights in the health care system. As a consequence, it is a high priority that health care providers have effective communication skills. It has been well documented that the doctor-patient relationship is central to the delivery of high quality medical care. It has been shown to affect patient satisfaction, to decrease the use of pain killers, to shorten hospital stays, to improve recovery from surgery and a variety of other biological, psychological and social outcomes [ 1 – 4 ]. Lack of knowledge of communication skills, or an inability to use them effectively, can be distressing and is potentially hazardous for patients. It may also be a cause of stress for medical students arriving on the ward for the first time [ 5 ]. There is a large body of evidence indicating the importance of students' knowledge of communication skills and [ 6 , 7 ] how behaviours learned from communication skills training transfer into the clinical setting and such training is known to have long term effects on students behaviour [ 8 – 11 ].

However, little is known about the importance of communication skills in the practice and training of doctors in Iran, where the culture differs greatly from that of the West. Sensitivity to religious matters is particularly important in Iranian doctor-patient relationships where Islam is more than a religion; it is a way of life. It controls politics, local laws, behaviour and many other aspects of daily life. It gives guidance in all spheres of human activity from birth to death. Therefore doctors coming into contact with religious patients need to be aware that there are numerous potential barriers to good communication [ 12 ].

A major criticism of current medical training in Iran is that communication skills have not been embedded in the curriculum of Iranian medical students, despite the richness and variety of evidence from elsewhere concerning the importance of communication skills. Concerns over poor doctor-patient communication amongst Iranian doctors led to an exploration of the current situation [ 13 ]. In this paper we investigate the knowledge level of interns about communication skills to gain a clearer picture of some challenges relating to health care promotion, especially patient satisfaction and adherence to treatment. Two questions guided the study: (a) How do interns assess their knowledge about communication skills? (b) Is there a significant difference between the level of knowledge among male and female interns?

A quantitative survey was performed at Tehran University of Medical Science (TUMS). A cross-sectional study was conducted using a questionnaire administered to 235 interns. Anonymity was maintained throughout. The subjects received the self-administered questionnaire with a covering letter explaining the project and the subject's rights. 12 subjects did not return the questionnaire and an additional 7 subjects did not give their age and one person did not give his/her sex. Therefore data analysis was based on 223 questionnaires, but covariate-based analysis on fewer. The subjects were asked to complete the questionnaire without referring to source books.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section asked students to give personal details including the demographic items age and gender (summarised in Table 1 ). The second section is related to the educational items: subjects studied or attended in a specific course about communication skills (Table 2 ). The third section asked students to rate their knowledge of communication skills and, if they rated themselves higher than 5, discuss the item briefly in the space provided in order to assess their real knowledge with regard to that communication skill. In addition, they were encouraged to provide additional written comments on the questionnaire. The communication skills knowledge scale (CSKS) developed here consists of 10 items about communication skills. Each item is measured on a 10-point scale, ranging from 1 (low) to 10 (high).

The choice of items was based on the communication skills an intern will need. All items were verified and subjected to content validation by three major experts in communication skills. These experts were given copies of the CSKS and the purpose and objectives of the study. They then evaluated the CSKS on an individual basis. Comparisons were made between these evaluations and the authors then made some minor changes within the CSKS. The CSKS had a high internal consistency ( Cronbach alpha = 0.8979).

The validity of the CSKS can only be examined through logical rather than empirical means. Since the CSKS was not compared to a standardised test, it was impossible to obtain a numerical estimate of the validity of the test. However, based on logical means, i.e., a respectable Cronbach alpha and high inter-rater agreements on each item, the authors believe that the test is valid. The questions and responses have been translated from Persian into English for this paper.

The potential score range from the 10-item CSKS (by summing all 10 item scores) is 10 to 100, with 10 indicating low knowledge. Analysis of the total scores produced a mean score of 51.30 [95 per cent confidence interval (CI) 49.05–53.55]. The subjects' performance on the CSKS suggests a knowledge deficit in communication skills. The mean scores for males and females were respectively 53.6 and 48.2 (P = 0.02). The vast majority of interns (78.1%) had not studied a paper on communication skills. When asked whether they had formally attended communication skills courses, 91.4% of interns reported "no". Of the few interns who reported "yes", these interns specified courses such as CPR, injections and semiology (Table 3 ), which are not formal communication skills courses.

The analysis of the scores by topic is shown in table 4 . The possible range of scores for each item was 1 to 10. Mean scores for topics ranged from 2.8 to 6.1. Interns were most confident on "giving and receiving information", and the least confident on "sex education".

A two-way between-groups analysis was conducted to explore the impact of sex and age on levels of knowledge, as measured by the CSKS. Subjects were divided into two groups according to their age (less than 25 years, or 25 years and above). There was a statistically significant main effect for sex [F (1, 212) = 4.90, p = 0.02] and the interaction effect [F (1, 212) = 4.06, p = 0.04) did reach statistical significance. However the effect size was small (eta squared = 0.02). The young male interns were more confident than average, while the young female interns were less confident.

Free responses included the following comments:

' Nobody has trained us about communication skills. Our knowledge in respect of communication skills is very poor. Your items show that we are very far behind other countries. Our universities are not as advanced as other universities' .

'I feel we are not familiar with the ABC of communication skills' .

'A good guide to communication skills needed' .

'I feel communication skills would be an excellent course since it gives us an idea of how we can handle bad news' .

'Attending doctors are not totally familiar with the aims and use of communication skills in the clinical setting' .

'All our courses only focus on biological issues rather than psychosocial issues'

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to this study.

The CSKS has not been normed for a population of interns.

Criterion-related validity of the CSKS was not determined, although content validity was established on the instrument.

Since it is a self-assessed questionnaire, these may be problems with bias, such as prestige bias.

The very high response rate (95%) of this questionnaire may have reflected general interest, or may have resulted from the advantages of self-assessment which itself may improve performance. The results on the CSKS show that basic knowledge of interns in Iran about communication skills is limited. Researchers have reported similar findings in other countries which reveal a deficit in the knowledge of doctors about communication skills [ 14 ]. The importance of communication skills has long been acknowledged in general practice training [ 15 ] and the need to teach communication skills formally, as part of British undergraduate medical education, has also been recognised [ 16 ]. In Iran, interns' knowledge deficiency may be attributed to the fact that interns have never been trained to consult in the general practice setting, and their skills are limited to making value judgements, often using the only available criterion, comparison with their own style [ 13 ]. This approach to a patient is not cost effective and may lead to negative health outcomes such as patient dissatisfaction, poor adherence to treatment and medical errors [ 17 ]. A few students reported their attendance at courses such as EBM, semiology, skills lab or CPR, which have no relation with communication skills training. This indicates that students are not familiar with the tasks of communication skills [ 18 ].

The vast majority of research studies have been conducted on the outcome of communication skills in the practice and training of doctors in western countries. Even here, despite doctors trained in communication skills and the advocacy of the use of a patient-oriented approach, some evidence suggests that there are difficulties in practice [ 19 , 20 ]. However, research has demonstrated that communication skills training intervention using behavioural, cognitive and affective domains can increase not only potentially beneficial and effective interviewing styles, but also alter attitudes and confer other benefits [ 9 , 21 ].

The results of the study show that there were significant differences between males and females with regard to their reported knowledge of the main communication skills. Women were less confident of their skills. The deficit may partly be an artefact of an inadvertent prestige bias of the male students. The deficit is particularly notable in sex education. There are three possible explanations for this. Firstly, in general, Iranian female interns are very shy to ask patients about sexual issues. Therefore they may feel that sex education skills have no implications for their practice and hence pay less attention to sex education training. Secondly, it may be a systematic error in female respondents, i.e. they may be shy to discuss their knowledge about sex education skills rather than lack knowledge. Thirdly, in the past, sex education was regarded as a taboo in Iran and was not available in schools, especially for girls [ 22 ]. This perhaps acts as an inhibitory factor on the basic knowledge of sex education. Within this context, there is no evidence that shows similar results for gender difference on the knowledge of sex education in the practice and training of doctors.

The results on the CSKS suggest that there are areas of weakness in the communication skills confidence of interns, particularly in breaking bad news. While it is well recognised that delivering bad news is a difficult task that requires skills and sensitivity [ 23 ], both female interns and male interns reported that their confidence in breaking bad news is low, especially the female interns. While the interns commented on the need to improve medical students' communication skills, it seems that guidelines on delivering bad news to patients and patients' family members have not been seriously taken into consideration in the practice and training of doctors in Iran. This could be due to interns possessing deep fears regarding delivering bad news to patients' family members, or because they are unaware of the general guidelines about delivering bad news [ 24 ]. Three studies which have attempted to address residents' perception of delivering bad news indicate that residents had experienced discomfort with psychosocial issues related to the conveyance of bad news, such as personal fears and different perceptions of bad news [ 25 – 27 ].

There is a significant difference between the mean score of the interns on breaking bad news. The female interns have reported lower confidence than the male interns. The deficit could be an inadvertent prestige bias of the male students. However, to our knowledge, there is no evidence that underpin such finding. Although Orlander et al's work [ 28 ] demonstrated there were no significant differences between males and females with regard to the type of bad news, residents' knowledge with regard to breaking bad news was not reported by the authors. Therefore, some empirical research is essential.

Given the poor levels of confidence about communication skills, particularly sex education skills, revealed in this study, it is concluded that educational programmes are necessary. In sex education skills training, given the complex interplay of cultural and religious beliefs in Iran, particular attention must be paid to multicultural and religious issues. Therefore, further work is needed on gender education and stereotypes in sex education; learning styles; the 'hidden curriculum'; and how far medical schools make organisational and administrative arrangements on the basis of gender and the implication for female and male interns.

The enthusiastic response to the questionnaires may suggest that medicine is accepting the need for developing communication skills within the medical curriculum. Medical education in Iran must respond to this challenge.

Finally, our findings may be somewhat limited in generalisability because they are derived from only one medical school in Iran. Self-assessment data may suffer from biases such as prestige bias. Despite these caveats, the authors believe the data to be an accurate reflection of current practice in Iran, based on the Iranian authors training experiences, and consistency with previous accounts.

Whilst the approach to this research has been shaped by a government-recognised health need, the authors recognise the need for, and welcome, further examination of these findings from multiple perspectives, especially with regards to ethnicity and social issues. Since not enough attention has been focused on individuals as makers of health as a service rather than customers of health care services, it is strongly recommended, therefore, that medical students be trained in the context of psychosocial issues that may influence health behaviour, as has been indicated by one of the participants. It is particularly important that this type of approach be incorporated into the curricula of medical training. This may assist in transferring from the disease-oriented to the patient-oriented approach and ultimately lead to patients understanding more and taking greater responsibility for their own health.

Haidet P, Dains JE, Paterniti DA, Hechtel L, Chang T, Tseng E, Rogers JC: Medical student attitudes toward the doctor-patient relationship. Med Educ. 2002, 36 (6): 568-574. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01233.x.

Article Google Scholar

Cegala DJ, Lenzmeier Broz S: Physician communication skills training: a review of theoretical backgrounds, objectives and skills. Med Educ. 2002, 36 (11): 1004-1016. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01331.x.

Brown JB, Boles M, Mullooly JP, Levinson W: Effect of clinician communication skills training on patient satisfaction. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999, 131 (11): 822-829.

Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB: Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995, 40 (7): 903-918. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-M.

Board P, Mercer M: A survey of the basic practical skills of final-year medical students in one UK medical school. Med Teach. 1998, 20: 104-108. 10.1080/01421599881183.

Cushing AM, Jones A: Evaluation of a breaking bad news course for medical students. Med Educ. 1995, 29 (6): 430-435.

Klein S, Tracy D, Kitchener HC, Walker LG: The effects of the participation of patients with cancer in teaching communication skills to medical undergraduates: a randomised study with follow-up after 2 years. Eur J Cancer. 2000, 36 (2): 273-281. 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00011-3.

Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Solis-Trapala I: Enduring impact of communication skills training: results of a 12-month follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2003, 89 (8): 1445-1449. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601309.

Jenkins V, Fallowfield L: Can communication skills training alter physicians' beliefs and behaviour in clinics?. J Clin Oncol. 2002, 20 (3): 765-769. 10.1200/JCO.20.3.765.

Wilkinson S, Bailey K, Aldridge J, Roberts A: A longitudinal evaluation of a communication skills programme. Palliat Med. 1999, 13 (4): 341-348. 10.1191/026921699672159169.

Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Saul J, Duffy A, Eves R: Efficacy of a Cancer Research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002, 359 (9307): 650-656. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8.

Macdonald E: Communication in a multicultural society. Difficult conversations in medicine. Edited by: Macdonald E. 2004, Oxford , Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Tavakol M, Murphy R, Torabi S: A needs assessment for a communication skills curriculum in Iran. Teach Learn Med. 2005, 17: 36-41. 10.1207/s15328015tlm1701_7.

Singh V, Khandelwal R, Bohra S, Gupta R, Gupta BS: Evaluation of communication skills of physicians about asthma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002, 50: 1266-1269.

Royal College of General Practiitioners: The future of General Practitionare: learning and teaching. 1972, London , British Medical Journal

General Medical Council: Tomorrow's doctors: Recommendations on undergraduate medical education. 1993, London , General Medical Council

Lepper H, Martin LR, Dimatteo MR: A model of nonverbal exchange in physician-patient expectations for patient involvement. Journal of Nonverbal Behaviour. 1995, 19: 207-222.

Kurtz SM: Doctor-patient communication: principles and practices. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002, 29 Suppl 2: S23-9.

Stevenson FA, Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley CP: Doctor-patient communication about drugs: the evidence for shared decision making. Soc Sci Med. 2000, 50 (6): 829-840. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00376-7.

Hargie O, Dickson D, Boohan M, Hughes K: A survey of communication skills training in UK schools of medicine: present practices and prospective proposals. Med Educ. 1998, 32 (1): 25-34. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00154.x.

Greco M, Spike N, Powell R, Brownlea A: Assessing communication skills of GP registrars: a comparison of patient and GP examiner ratings. Med Educ. 2002, 36 (4): 366-376. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01175.x.

Tavakol M, Torabi S, Gibbons C: A quantitative survey of knowledge of reproductive health issues of 12-14-year old girls of different ethnic and religious background in Iran: Implication for education. Sex education. 2003, 3: 231-239.

Ptacek JT, Eberhardt TL: Breaking bad news. A review of the literature. Jama. 1996, 276 (6): 496-502. 10.1001/jama.276.6.496.

Buckman R: How to break bad news: A guide for health care professionals. 1992, Baltimore , Johan Hopkins Press

Dosanjh S, Barnes J, Bhandari M: Barriers to breaking bad news among medical and surgical residents. Med Educ. 2001, 35 (3): 197-205. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00766.x.

Eden OB, Black J, Mackinlay GA, Emery AE: Communication with parents of children with cancer. Palliat Med. 1994, 8: 105-114.

Fallowfield LJ, Clark AW: Delivering bad news in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994, 89 (4): 473-479.

Orlander JD, Fincke BG, Hermanns D, Johnson GA: Medical residents' first clearly remembered experiences of giving bad news. J Gen Intern Med. 2002, 17 (11): 825-831. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10915.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/5/6/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Tehran University of Medical science, Centre for Medical Education for their support of this study. Thanks also to the two reviewers whose comments allowed us to improve on our previous draft.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Nottingham University, Wollaton Road, Nottingham, UK

Mohsen Tavakol

Ministry of Science, Research and Technology, Institute for research and planning in higher education, Iran

Sima Torabi

Institute of Mathematics, Statistics and Actuarial Science, University of Kent, UK

Owen D Lyne

Educational Development Centre, Tehran University of Medical Science, Iran

Ali A Zeinaloo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohsen Tavakol .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MT and ST carried out the conception, design, initial analysis and interpretation of the data. MT drafted the paper. ODL was involved in revising the draft critically, revising the statistical analysis and gave final approval of the version to be published. AAZ contributed to the collection of data and the reviewing of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tavakol, M., Torabi, S., Lyne, O.D. et al. A quantitative survey of intern's knowledge of communication skills: an Iranian exploration. BMC Med Educ 5 , 6 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-5-6

Download citation

Received : 18 November 2004

Accepted : 08 February 2005

Published : 08 February 2005

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-5-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Communication Skill

- Communication Skill Training

- Effective Communication Skill

- Affect Patient Satisfaction

- General Practice Training

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.1; 2022 Dec

- PMC10194302

Novel approaches to communication skills development: The untapped potential of qualitative research immersion

Amy s. porter.

a St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA

Cameka Woods

Erica c. kaye, associated data.

Participation in qualitative research, particularly analysis of recorded medical dialogue, offers real-time, longitudinal immersion that can strengthen clinical trainee communication skills. The study objective was to explore how qualitative research participation impacts clinical trainees’ self-perceived communication skills development and practice.

In this study, a 17-member multidisciplinary working group of child life specialists, advanced practice providers, undergraduate/medical students, residents, fellows, attending physicians, social scientists, and career researchers with recent qualitative and communication research experience assembled to discuss this topic using a structured discussion guide. Content analysis was used to identify concepts and themes.

Three key themes characterizing the impact of qualitative research participation on aspiring clinicians’ communication skills development and practice arose – the 3Cs: (1) C onnection, therapeutic alliance, and accompaniment; (2) C larity and prognostic communication; (3) C ompassion, empathy, and understanding. Participants emphasized that qualitative research learning improved their understanding of patient/family lived experiences, preparing them for future clinical encounters, strengthening their emotional intelligence, and promoting self-care, resilience, and professional affirmation.

Conclusions

Immersion in clinical communication through participation in qualitative research is an under-utilized resource for supporting clinical trainees in communication skills development.

The process of collaborative knowledge production through the collective exploration of an a priori question related to group members’ collective experiences is methodologically innovative. Further, re-thinking qualitative research participation as an underutilized educational opportunity is pedagogically novel, and leaders in medical education and qualitative research should collaborate to realize the potential of this teaching tool.

- • Qualitative research participation offers immersion in clinical communication.

- • Participation impact characterized by the 3 C’s: 1) Connection, 2) Clarity, 3) Compassion.

- • This is an under-utilized medical education resource for communication skills development.

- • Medical education and qualitative research leaders should collaborate.

1. Introduction

Communication training for clinical trainees often involves single timepoint simulation as a “gold standard” for practicing navigation of challenging conversations [ [1] , [2] , [3] , [4] , [5] , [6] , [7] , [8] , [9] , [10] , [11] , [12] ]. Due to time, staffing, and resource constraints, medical educators face challenges realizing high volume of real-time communication learning opportunities [ 1 ]. Clinicians-in-training are exposed infrequently and inconsistently to in-depth, communication-heavy encounters between clinicians and patients and their families during difficult moments in the illness course [ 5 , 13 , 14 ]. As a result, trainees lack robust opportunities to witness communication and consider which modeled approaches they want to integrate into their own communication toolboxes. Further, depending on supervisory ratios, trainees may not have sufficient opportunities to observe clinicians with a range of emotional dexterity skills to learn and reflect on how (or how not) to communicate during challenging medical encounters.

Healthcare communication science researchers have amassed large repositories of recorded medical dialogue to answer questions about best practices for communication between patients, families, and healthcare professionals; however, little precedent exists for collaboration between communication researchers and medical education leaders to optimize use of this under-utilized resource to offer learners opportunities for developing communication skills through participation in communication research. Existing literature explores how guided reflection activities such as “The Healer’s Art” and other self-contemplative didactics positively impact trainees’ communication skills, empathy, self-awareness, and overall clinical practice [ [15] , [16] , [17] ], yet the potential educational value and impact of qualitative research experiences on trainees’ learning and communication skills remains understudied and poorly understood.

To address this knowledge gap, we convened a multidisciplinary working group of students, clinicians, and researchers to consider the question: “How does engaging in qualitative communication research (i.e., listening to audio recordings and/or reading transcripts of recorded clinical encounters) impact trainees as professionals (both clinicians and researchers) and as individuals holistically?” The Qu alitative research as E ducation for S tudents and clinicians-in- Tr aining (QUEST) working group comprised individuals affiliated with a communication research lab within an academic institution who each had recent experiences participating in qualitative research on topics related to communication. The working group examined whether engaging in qualitative research involving patients and families could influence the way students and clinicians-in-training learn and practice communication. In this article, we summarize findings from the QUEST working group and propose immersion in qualitative research datasets as an innovative alternative or complement to standardized simulated communication skills training.

In this study, we used an adaptation of autoethnography to bring together a team of authors with common experiences related to qualitative research participation, collectively share our perceptions and generate reflective data about our experiences with qualitative research, and collaborate with one another to analyze the data and present our insights. In traditional autoethnographic methods, an individual uses a reliable process to generate data from their own experience, observations, and reflections and then reflects on and synthesizes these data to inform a larger context [ 18 ]. Koopman et al describes autoethnography as the ultimate form of reflexivity, a mechanism by which to explore personal perceptions, values, and beliefs through the lens of lived experience, culture, and self-other interactions [ 19 ]. In this project, our authorship team wished to gain deeper insights into the potential influence of qualitative research participation on communication education for students and clinicians. In deciding to study ourselves, we developed a modified form of autoethnography, which we describe below. This paper reports the findings from the QUEST working group with all group members represented as authors; there were not separate groups representing “researchers” and “study participants,” but rather one collaborative group working together to explore an a priori question related to our collective experiences. As such, the project did not require IRB approval.

The authorship team convened as the QUEST working group, comprising a 17-member group of students, staff, and faculty with recent qualitative communication research experience, including undergraduate/medical students, residents, fellows, child life specialists, advanced practice providers, and clinical research staff. Within the Quality of Life and Palliative Care Research Division, all learners who had participated in communication research by listening to recorded medical dialogue or reading transcripts of interviews with patients, families, and clinicians at a particular academic institution over the past 3 years were invited via email to participate (n = 21). No exclusionary requirements were applied. Though all invited individuals expressed interest in joining the QUEST working group, a total of 17 people ultimately participated. Individuals agreed to participate in working group conversations by responding in writing to the email invitation. All working group members had participated in analysis of at least one qualitative data set related to communication, with most participating in qualitative research for at least one year (although outliers included 1 member with a 2-month qualitative research elective and 1 member with 5+ years of qualitative research participation). Most of the group was comprised of nursing/medical trainees (e.g., undergraduate, graduate, nursing, and medical students; fellows; n=13); the group also included 2 clinical research staff who engage in communication with patients and families, 1 child life specialist who participated in qualitative research, and 1 clinician-researcher who oversees qualitative research studies. Members’ training, roles, and experiences interfacing with different types of qualitative data are presented in Table 1 .

QUEST working group member characteristics.

The three lead authors crafted a semi-structured working group discussion guide, with iterative revisions to refine questions for content and language. Supplemental Figure presents the guide, encompassing a semi-structured outline of questions prompts and probes to organize and support cooperative conversation. Working group members were encouraged via email to join a virtual 120-minute discussion; those who could not attend were given an opportunity to respond to the questions in writing. A physician-medical anthropologist with training and expertise in group engagement facilitated the virtual discussion. Twelve QUEST working group members, including the three lead authors, attended the recorded virtual session using WebEx (an online platform for virtual group meetings). The conversation introduction included reminders about the importance of reflexivity and how participants’ positionality influences (and may bias) perspectives. Throughout the virtual discussion session, each participant remained engaged and interacted with most question probes, yielding multiple responses for each question. A working group format was used intentionally to explore the targeted question, given the positive potential for group dynamics to help with idea generativity and allow reflections to build upon others’ thoughts and observations [ 20 , 21 ]. Most working group members were students and trainees or clinical research staff, interacting within similar hierarchical tiers. Recognizing the potential for hierarchy to constrain conversation, the one faculty member in a supervisory position observed quietly, engaging only when asked a direct question by another working group member.

Five working group members were unable to attend the virtual discussion due to their training schedules, and they wished to participate in the exploratory question. To ensure inclusion of their voices and perspectives, they were given an opportunity to provide written reflection responses to each item in the structured discussion guide; these lengthy responses were shared via email to contribute their perspectives to the conversation.

Following data generation, the three lead authors initially conducted memo-writing of the recorded discussion and written responses to begin reflecting on and discussing emerging patterns in working group conversation content [ 22 ]. Memo-writers purposefully represented different perspectives from a current clinical trainee, a research staff member, and a faculty member, with iterative discussions held in person and via email to explore how different viewpoints influenced reflections in memos and examine internal biases shaping thoughts and assessments. Content analysis was used to synthesize working group transcripts as this method provides a rigorous process for identification of concepts and themes within text. As concepts were inductively generated via memo-writing, findings were shared with all QUEST members for iterative reflection and input. The QUEST working group collaborated to synthesize and review key themes, with cycles of review and refinement among authors [ 23 , 24 ]. The final report was presented to the working group for member-checking [ 25 ], with confirmation from all authors that thematic findings reflected the comprehensive content of working group discussions.

Working group members consistently emphasized the value of immersion in qualitative research, highlighting the utility of engagement with audio recorded and/or transcribed clinical encounters that included challenging communication scenarios ( Fig. 1 ). Nearly all members described the impact of qualitative research experiences on their personal communication skills and practice, and two driving themes emerged to characterize the “value added” by qualitative research: 1) the tangible benefits of exposure to difficult medical communication prior to real-life encounters; and 2) the potential for long-lasting impact and sustained influence of qualitative research experiences on future clinical practice, including three specific impacts on communication skills (“the 3Cs”).

Influences of qualitative research immersion on learner communication skills.

3.1. Immersive learning prior to real-life training and practice

For many working group members, communication challenges in healthcare were largely hypothetical prior to their participation in qualitative research. Coding real clinical encounters as part of qualitative research revealed the complexity of interpersonal communication and offered lessons for how to navigate difficult conversations with actual patients and families: “I really saw models of what this actually looks like and how do patients and their families respond to different styles.” Authors with limited previous exposure to clinical encounters also shared how immersion in raw qualitative data helped them recognize the emotional intensity experienced by patients, families, and clinicians:

“Listening [to audio-recorded medical dialogue] really helped me to understand how much tension there can be in a room… Just listening to long pauses of silence helped me understand that [prognostic communication] can be really challenging emotionally, both on the clinician side and the family and patient side, how challenging it can be to navigate that both as a parent and as a clinician.”

Another member described how her participation in qualitative research as a medical student informed her future practice as a resident:

“I began intern year in the intensive care unit and had several patients die within my first two to three weeks of residency. Communicating with these families about the goals or priorities of their loved one and then having to tell them when that person had died required attention to detail, meticulous word choice, and rapport building. All of these skills were taught or honed by the coding experience.”

Universally, working group members highlighted how exposure to “real” clinical encounters offered them unique experiences to observe communication skills and reflect on interpersonal dynamics that they could carry forward into their future clinical practice.

3.2. Sustained influence on future clinical practice

Overall, working group members agreed that participating in qualitative research had a greater impact than they anticipated on the way that they provide clinical care. One child life specialist explained specifically how real clinical encounters still shape her everyday clinical practice: