Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Exploring the relationships between heritage tourism, sustainable community development and host communities’ health and wellbeing: A systematic review

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Translational Health Research Institute, School of Medicine, Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations School of Social Sciences, Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia, Department of Archaeology, University of York, York, United Kingdom

* E-mail: [email protected]

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Translational Health Research Institute, School of Medicine, Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia, Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Program, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Australia

- Cristy Brooks,

- Emma Waterton,

- Hayley Saul,

- Andre Renzaho

- Published: March 29, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319

- Reader Comments

Previous studies examining the impact of heritage tourism have focused on specific ecological, economic, political, or cultural impacts. Research focused on the extent to which heritage tourism fosters host communities’ participation and enhances their capacity to flourish and support long-term health and wellbeing is lacking. This systematic review assessed the impact of heritage tourism on sustainable community development, as well as the health and wellbeing of local communities. Studies were included if they: (i) were conducted in English; (ii) were published between January 2000 and March 2021; (iii) used qualitative and/or quantitative methods; (iv) analysed the impact of heritage tourism on sustainable community development and/or the health and wellbeing of local host communities; and (v) had a full-text copy available. The search identified 5292 articles, of which 102 articles met the inclusion criteria. The included studies covering six WHO regions (Western Pacific, African, Americas, South-East Asia, European, Eastern Mediterranean, and multiple regions). These studies show that heritage tourism had positive and negative impacts on social determinants of health. Positive impacts included economic gains, rejuvenation of culture, infrastructure development, and improved social services. However, heritage tourism also had deleterious effects on health, such as restrictions placed on local community participation and access to land, loss of livelihood, relocation and/or fragmentation of communities, increased outmigration, increases in crime, and erosion of culture. Thus, while heritage tourism may be a poverty-reducing strategy, its success depends on the inclusion of host communities in heritage tourism governance, decision-making processes, and access to resources and programs. Future policymakers are encouraged to adopt a holistic view of benefits along with detriments to sustainable heritage tourism development. Additional research should consider the health and wellbeing of local community groups engaged in heritage tourism. Protocol PROSPERO registration number: CRD42018114681.

Citation: Brooks C, Waterton E, Saul H, Renzaho A (2023) Exploring the relationships between heritage tourism, sustainable community development and host communities’ health and wellbeing: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 18(3): e0282319. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319

Editor: Tai Ming Wut, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, HONG KONG

Received: April 29, 2022; Accepted: February 14, 2023; Published: March 29, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Brooks et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Tourism, heritage, and sustainable development go hand in hand. Socio-economically, tourism is considered a vital means of sustainable human development worldwide, and remains one of the world’s top creators of employment and a lead income-generator, particularly for Global South countries [ 1 ]. For most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), tourism is a key component of export earnings and export diversification, and a major source of foreign-currency income [ 1 ]. In 2019, prior to the international travel restrictions implemented to contain the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), export revenues from international tourism were estimated at USD 1.7 trillion, the world’s third largest export category after fuels and chemicals with great economic impacts. Tourism remains a major part of gross domestic product, generating millions of direct and indirect jobs, and helping LMICs reduce trade deficits [ 1 ]. It accounts for 28 per cent of the world’s trade in services, 7 per cent of overall exports of goods and services and 1 out of 10 jobs in the world [ 1 ]. Given this, it is anticipated that tourism will play a strong role in achieving all of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but particularly Goals 1 (No poverty), 8 (Decent work and economic growth), 12 (Responsible consumption and production), 13 (Climate action) and 14 (Life below water).

To ensure tourism’s continued contribution to sustainable development efforts, the World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) has established the T4SDG platform in order to “to make tourism matter on the journey to 2030” [ 2 ]. Likewise, in recognition of the relationship between heritage, tourism, and sustainable development, UNESCO launched the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme, which was adopted by the World Heritage Committee in 2012. This Programme encapsulates a framework that builds on dialogue and stakeholder cooperation to promote an integrated approach to planning for tourism and heritage management in host countries, to protect and value natural and cultural assets, and develop appropriate and sustainable tourism pathways [ 3 ].

The addition of ‘heritage’ creates an important sub-category within the tourism industry: heritage tourism. This study adopts a broad definition of ‘heritage’, which encompasses the intersecting forms of tangible heritage, such as buildings, monuments, and works of art, intangible or living heritage, including folklore, cultural memories, celebrations and traditions, and natural heritage, or culturally infused landscapes and places of significant biodiversity [ 4 ]. This encompassing definition captures ‘heritage’ as it is understood at the international level, as evidenced by two key UNESCO conventions: the 1972 Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage , which protects cultural, natural, and mixed heritage; and the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage , which protects intangible heritage. Although the identification, conservation and management of heritage has traditionally been driven by national aspirations to preserve connections with history, ancestry, and national identity, the social and economic benefits of heritage tourism at community levels have also been documented [ 5 ].

Heritage tourism, as one of the oldest practices of travelling for leisure, is a significant sector of the tourism industry. It refers to the practice of visiting places because of their connections to cultural, natural, and intangible heritage and is oriented towards showcasing notable relationships to a shared past at a given tourism destination [ 4 ]. It contributes to global interchange and inter-cultural understanding [ 4 ]. Heritage tourism places economic and political value on recognised heritage resources and assets, providing additional reasons to conserve heritage further to the cultural imperatives for its maintenance [ 5 ]. By drawing on the cultural and historical capital of a community, heritage tourism can contribute to the flourishing of local communities and their positive sustainable development. However, as this systematic review will demonstrate, when applied uncritically and without meaningful engagement with the needs of local stakeholder, heritage tourism can also elicit damaging effects on community health and wellbeing.

First published in 1987, the classic report ‘ Our Common Future’ , more commonly known as the Brundtland Report, conceptualised sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [ 6 ]. Although this definition still works for many purposes, it emphasised the critical issues of environment and development whilst turning on the undefined implications of the word ‘needs’. In the report, the concept of sustainable development thus left unspecified the assumed importance of distinct cultural, political, economic, and ecological needs as well as health needs. Drawing on the work of globalization and cultural diversity scholar, Paul James [ 7 ], in this study we have defined ‘positive sustainable development’ as those “practices and meanings of human engagement that make for lifeworlds that project the ongoing probability of natural and social flourishing”, taking into account questions of vitality, relationality, productivity and sustainability.

Study rationale

For many years, the impact of heritage tourism has predominantly been viewed through ecological [ 8 , 9 ], economic and cultural [ 10 , 11 ] or political [ 12 ] lenses. For example, it has often been assumed that the conservation of historic, cultural, and natural resources, in combination with tourism, will naturally lead to sustainable local economies through increases in employment opportunities, provisioning of a platform for profitable new business opportunities, investment in infrastructure, improving public utilities and transport infrastructures, supporting the protection of natural resources, and, more recently, improving quality of life for local residents [ 13 – 15 ].

Similarly, the impact of heritage tourism on health and wellbeing has tended to focus on visitors’ wellbeing, including their health education and possible health trends, medical aspects of travel preparation, and health problems in returning tourists [ 16 – 18 ]. It has only been more recently that host communities’ health needs and wellbeing have been recognised as an intrinsic part of cultural heritage management and sustainable community development [ 19 ]. In this literature, it has been hypothesised that potential health implications of heritage tourism are either indirect or direct. Indirect effects are predominantly associated with health gains from heritage tourism-related economic, environmental, socio-cultural, and political impacts [ 20 ]. In contrast, health implications associated with direct impacts are closely associated with immediate encounters between tourism and people [ 20 ]. Yet, little is known of the overall generative effects of heritage tourism on sustainable community development, or the long-term health and wellbeing of local communities. For the first time, this systematic review identified and evaluated 102 published and unpublished studies in order to assess the extent to which heritage tourism fosters host communities’ participation and, consequently, their capacity to flourish, with emphasis placed on the long-term health impacts of this. The primary objective of the review was to determine: (1) what the impacts of heritage tourism are on sustainable community development; as well as (2) on the health and wellbeing of local host communities. Understanding the relationship between heritage tourism, sustainable community development and health is essential in influencing policies aimed at improving overall livelihood in local host communities, as well as informing intervention strategies and knowledge advancement.

This systematic review adhered to the guidelines and criteria set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement [ 21 ]. A protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018114681) and has been published [ 22 ].

Search strategy

In order to avoid replicating an already existing study on this topic, Cochrane library, Google Scholar and Scopus were searched to ensure there were no previous systematic reviews or meta-analyses on the impact of heritage tourism on sustainable community development and the health of local host communities. No such reviews or analyses were found. The search then sought to use a list of relevant text words and sub-headings of keywords and/or MeSH vocabulary according to each searched database. Derived from the above research question, the key search words were related to heritage tourism, sustainable community development, and health and wellbeing of local host communities. A trial search of our selected databases (see below) found that there are no MeSH words for heritage and tourism. Therefore, multiple keywords were included to identify relevant articles.

To obtain more focused and productive results, the keywords were linked using “AND” and “OR” and other relevant Boolean operators, where permitted by the databases. Subject heading truncations (*) were applied where appropriate. The search query was developed and tested in ProQuest Central on 22 November 2018. Following this search trial, the following combination of search terms and keywords, slightly modified to suit each database, was subsequently used:

(“Heritage tourism” OR tourism OR “world heritage site” OR ecotourism OR “heritage based tourism” OR “cultural tourism” OR “diaspora tourism” OR “cultural heritage tourism” OR “cultural resource management” OR “cultural heritage management” OR “historic site”)

(“Health status” [MeSH] OR “health equity” OR health OR community health OR welfare OR wellbeing)

(“sustainable development” [MeSH] OR sustainab* or “community development” or “local development” or “local community” or “indigenous community”)

The search covered the following bibliographic databases and electronic collections:

- Academic Search Complete

- Australian Heritage Bibliography (AHB)

- Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)

- CAB Abstracts

- ProQuest Central

- Science And Geography Education (SAGE)

- Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure

In addition, grey literature were also sourced from key organisation websites including the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), the International Council of Museums (ICOM), the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) and the Smithsonian Institution.

Where the full texts of included articles could not be accessed, corresponding authors were contacted via e-mail or other means of communication (e.g., ResearchGate) to obtain a copy. A further search of the bibliographical references of all retrieved articles and articles’ citation tracking using Google Scholar was conducted to capture relevant articles that might have been missed during the initial search but that meet the inclusion criteria. For the purposes of transparency and accountability, a search log was kept and constantly updated to ensure that newly published articles were captured. To maximise the accuracy of the search, two researchers with extensive knowledge of heritage tourism literature (EW and HS) and two research assistants with backgrounds in public health and social sciences implemented independently the search syntax across the databases and organisations’ websites to ensure no article was missed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Criteria used in this systematic review focused on the types of beneficiaries of heritage tourism, outcomes of interest, as well as the intervention designs. The outcomes of interest were sustainable community development and evidence for the overall health and wellbeing of local host communities. In this systematic review, sustainable community development was defined in terms of its two components: ‘community sustainability’ and ‘development’. Community sustainability was conceptualised as the “long-term durability of a community as it negotiates changing practices and meanings across all the domains of culture, politics, economics and ecology” (pp. 21, 24) [ 23 ].

In contrast, development was conceptualised as “social change—with all its intended or unintended outcomes, good and bad—that brings about a significant and patterned shift in the technologies, techniques, infrastructure, and/or associated life-forms of a place or people” (p. 44) [ 7 ]. To this, we added the question of whether the development was positive or negative. Thus, going beyond the Brundtland definition introduced earlier and once again borrowing from the work of Paul James, positive sustainable development was defined as “practices and meanings of human engagement that make for lifeworlds that project the ongoing probability of natural and social flourishing”, including good health [ 23 ].

Health was defined, using the World Health Organisation (WHO) definition, as “overall well-being” and as including both physical, mental and social health [ 24 ]. While there is no consensus on what wellbeing actually means, there is a general agreement that wellbeing encompasses positive emotions and moods (e.g., contentment, happiness), the absence of negative emotions (e.g., depression, anxiety) as well as satisfaction with life and positive functioning [ 25 ]. Therefore, wellbeing in this systematic review was conceptualised according to Ryff’s multidimensional model of psychological wellbeing, which includes six factors: autonomy; self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relationships with others, purpose in life, and personal growth [ 26 ].

In terms of intervention and design, this systematic review included peer-reviewed and grey literature sources of evidence [ 27 , 28 ] from quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies. Intervention designs of interest were observational studies (e.g. longitudinal studies, case control and cross-sectional studies) as well as qualitative and mixed-methods studies. The following additional restrictions were used to ensure texts were included only if they were: (i) written in English; (ii) analysed the impact of heritage tourism on sustainable community development and health and/or wellbeing of local host communities; (iii) research papers, dissertations, books, book chapters, working papers, technical reports including project documents and evaluation reports, discussion papers, and conference papers; and (iv) published between January 2000 and March 2021. Studies were excluded if they were descriptive in nature and did not have community development or health and wellbeing indicators as outcome measures.

The year 2000 was selected as the baseline date due to the signing of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by Member States in September of that year. With the introduction of the MDGs, now superseded by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), there was an increase in commitment from government and non-governmental organizations to promote the development of responsible, sustainable and universally accessible tourism [ 29 , 30 ]. Editorials, reviews, letter to editors, commentaries and opinion pieces were not considered. Where full text articles were not able to be retrieved despite exhausting all available methods (including contacting corresponding author/s), such studies were excluded from the review. Non-human studies were also excluded.

Study selection and screening

Data retrieved from the various database searches were imported into an EndNote X9 library. A three-stage screening process was followed to assess each study’s eligibility for inclusion. In the EndNote library, stage one involved screening studies by titles to remove duplicates. In stage two, titles and abstracts were manually screened for eligibility and relevance. In the third and final screening stage, full texts of selected abstracts were further reviewed for eligibility. The full study selection process according to PRISMA is summarised in Fig 1 . A total of 5292 articles from 10 databases and multiple sources of grey literature were screened. After removal of duplicates, 4293 articles were retained.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319.g001

Titles and abstracts were further screened for indications that articles contain empirical research on the relationship between heritage tourism, sustainable community development and the health and wellbeing of local host communities. This element of the screening process resulted in the exclusion of 2892 articles. The remaining 1401 articles were screened for eligibility: 1299 articles were further excluded, resulting in 102 articles that met our inclusion criteria and were retained for analysis. Study selection was led by two researchers (EW and HS) and one research assistant, who independently double-checked 40% of randomly selected articles (n = 53). Interrater agreement was calculated using a 3-point ordinal scale, with the scoring being ’yes, definitely in’ = 1, ’?’ for unsure = 2, and ’no, definitely out’ = 3. Weighted Kappa coefficients were calculated using quadratic weights. Kappa statistics and percentage of agreement were 0.76 (95%CI: 0.63, 0.90) and 0.90 (95%CI: 0.85, 0.96) respectively, suggesting excellent agreement.

Data extraction

Data extraction was completed using a piloted form and was performed and subsequently reviewed independently by three researchers (AR, EW and HS), all of whom are authors. The extracted data included: study details (author, year of publication, country of research), study aims and objectives, study characteristics and methodological approach (study design, sample size, outcome measures, intervention), major findings, and limitations.

Quality assessment

To account for the diversity in design and dissemination strategies (peer-reviewed vs non-peer-reviewed) of included studies, the (JBI) Joanna Briggs Institute’s Critical Review Tool for qualitative and quantitative studies [ 31 ], mixed methods appraisal Tool (MMAT) for mixed methods [ 32 ], and the AACODS (Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance) checklist for grey literature [ 33 ] were used to assess the quality of included studies. The quality assessment of included studies was led by one researcher (CB), but 40% of the studies were randomly selected and scored by three senior researchers (AR, EM, and HS) to check the accuracy of the scoring. Cohen’s kappa statistic was used to assess the agreement between quality assessment scorers. Kappa statistics and percentage of agreement were 0.80 (95%CI: 0.64, 0.96) and 0.96 (95%CI: 0.93, 0.99) respectively, suggesting excellent interrater agreement. The quality assessment scales used different numbers of questions and different ranges, hence they were all rescaled/normalised to a 100 point scale, from 0 (poor quality) to 100 (high quality) using the min-max scaling approach. Scores were stratified by tertiles, being high quality (>75), moderate quality (50–74), or poor quality (<50).

Data synthesis

Due to the heterogeneity and variation of the studies reviewed (study methods, measurements, and outcomes), a meta-analysis was not possible. Campbell and colleagues (2020) [ 34 ] recognise that not all data extracted for a systematic review are amenable to meta-analysis, but highlight a serious gap in the literature: the authors’ lack of or poor description of alternative synthesis methods. The authors described an array of alternative methods to meta-analysis. In our study we used a meta-ethnography approach to articulate the complex but diverse outcomes reported in included studies [ 35 ]. Increasingly common and influential [ 36 ], meta-ethnography is an explicitly interpretative approach to the synthesis of evidence [ 36 , 37 ] that aims to develop new explanatory theories or conceptualisations of a given body of work on the basis of reviewer interpretation [ 37 ]. It draws out similarities and differences at the conceptual level between the findings of included studies [ 37 ], with the foundational premise being the juxtaposition and relative examination of ideas between study findings [ 37 ]. Resulting novel interpretations are then considered to transcend individual study findings [ 36 ].

Originating with sociologists Noblit and Hare [ 36 , 38 ], and adopted and expanded upon by other researchers [ 36 , 37 ], meta-ethnography involves a 7-stage process of evidence synthesis and concludes with the translation and synthesis of studies [ 38 ]. The approach centres around the emergence of concepts and themes from included studies that are examined in relation to each other and used to synthesise and communicate primary research findings. In meta-ethnography, the diversity of studies such as the heterogeneity and variation of included studies in the present review, is considered an asset opposed to an issue in synthesis or translation of research findings [ 37 ].

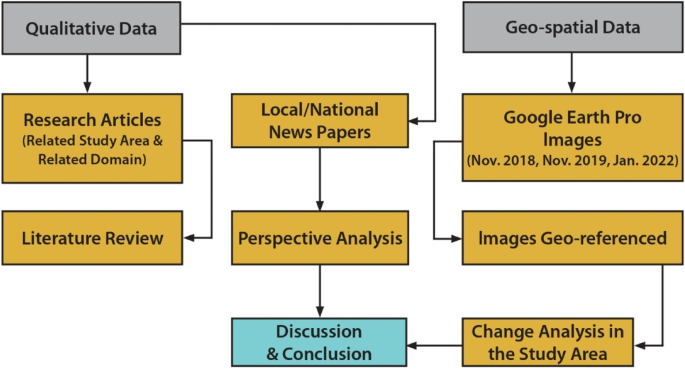

Common threads, themes and trends were identified and extracted from both qualitative and quantitative narratives to generate insight on the impact of heritage tourism on sustainable community development and health. In order to increase reproducibility and transparency of our methods and the conclusions drawn from the studies, the narrative synthesis adhered to the “Improving Conduct and Reporting of Narrative Synthesis of Quantitative Data” protocol for mixed methods studies [ 39 ]. One of the primary researchers (CB) summarised the study findings and narrated the emerging themes and subthemes. The emerging themes were discussed with all authors for appropriateness of the content as well as for consistency. All studies were included in the synthesis of evidence and emergence of themes. The meta-ethnographic approach involved the following processes:

Identifying metaphors and themes.

Included studies were read and reviewed multiple times to gain familiarity and understanding with the data and identify themes and patterns in each study. As noted above, data was extracted from each study using a piloted template to remain consistent across all studies. The aims and/or objectives of each study was revisited regularly to validate any extracted data and remain familiar with the purpose of the study. Themes and, where relevant, sub-themes were identified, usually in the results and discussion section of included studies.

Determining how the studies were related.

Studies were grouped according to WHO regions (see Table 1 ). Thematic analysis was compared across all included studies regardless of region to identify common themes and/or sub-themes to determine how studies were related to one another. Although this review included a widely varied and large number of studies (n = 102), the findings of each study nonetheless had a common underpinning theme of heritage-based tourism. This enabled the identification of communal categories across the studies indicating their relatedness. For example, there were common themes of socio-cultural, socio-economic, community health, wellbeing, and empowerment factors and so on.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319.t001

Translation and synthesis of studies.

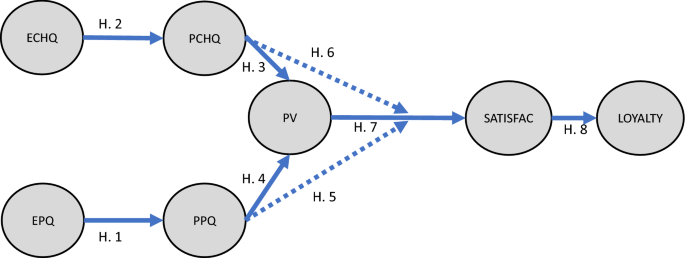

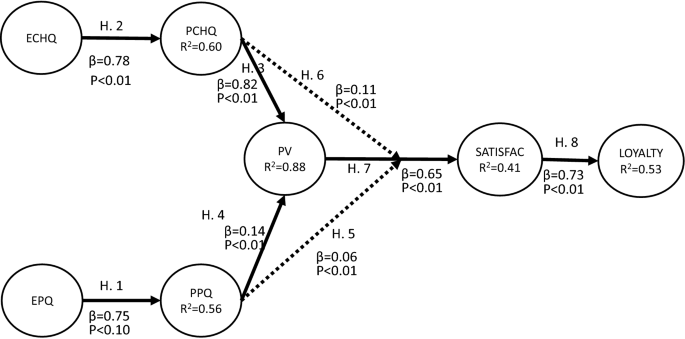

Themes and, where relevant, sub-themes within each study were considered and compared to the next study in a process repeated for all included studies. Such translation of studies compares and matches themes across a corpus of material, and usually involves one or more of three main types of synthesis: reciprocal translation, refutational translation, and line of argument [ 37 ]. Themes were condensed and streamlined into main thematic areas, in addition to outlining common topics within those thematic areas. The primary researcher (CB) undertook this process with discussion, validation and confirmation of themes and topics from three other researchers (EW, HS and AR). Translation between studies and the resulting synthesis of research findings followed the process of the emergence of new interpretations and conceptualisation of research themes. A line of argument was also developed, and a conceptual model produced to describe the research findings, which is shown in Fig 2 . Both the line of argument and conceptual model were agreed upon by all authors.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319.g002

A total of 102 studies were included in the analysis. Of these, 25 studies were conducted in the Western Pacific region, 23 in the African region, 20 in the Region of the Americas, 17 in the South-East Asia region, 12 in the European region, and 1 in the Eastern Mediterranean region. The remaining 4 studies reported on multiple regions. This may at first seem surprising given the prominence of European cultural heritage on registers such as the World Heritage List, which includes 469 cultural sites located Europe (equivalent to 47.19% of all World Heritage Properties that are recognised for their cultural values). However, any studies focusing on Europe that did not also examine sustainable community development and the overall health and wellbeing of local host communities were screened out of this systematic review in accordance with the abovementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Results of the data extraction and quality assessment across all included studies are presented in Table 1 . Of the included studies, 24 used a mixed methods design, 22 studies were qualitative, 36 were quantitative and 20 were grey literature (see Table 1 for more detail regarding the type of methods employed). Of these, 48 studies were assessed as high quality (>75), 32 as moderate quality (50–74) and 22 as poor quality (<50).

The major health and wellbeing determinant themes emerging from the included studies were grouped according to social, cultural, economic, and ecological health determinants. Fig 3 presents the proportion of included studies that investigated each of the four health determinants when assessed by WHO region. A large proportion of economic studies was shown across all regions, although this focus was surpassed by the social health determinant in the South-East Asia region ( Fig 3 ). Studies on the social health determinant also yielded a strong proportion of studies across most other regions, although notably not in the African region. This was closely followed by an ecological focus among the Americas, South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions. The Americas had the highest proportion of cultural studies, with the European region being the lowest proportionally ( Fig 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319.g003

More specifically, for studies focused on Africa, 100% of the publications included in this review explicitly investigated the economic benefits of tourism on wellbeing (74% of them exclusively), with European-focused studies reflecting a similarly high interest in economic wellbeing (91% of publications). Across the Americas, economic determinants of wellbeing were investigated in 86% of publications and in the Western Pacific, methods to investigate this variable were built into 80% of included studies. By comparison, this research demonstrates that only just over two thirds of articles reporting on the South-East Asia region shared this focus on economic determinants (65% of publications). Instead, social determinants of wellbeing form a stronger component of the research agenda in this region, with 76% of publications investigating this theme in studies that also tended to consider multiple drivers of health. For example, in 47% of publications reporting on the South-East Asia context, at least three themes were integrated into each study, with particular synergies emerging between social, economic and ecological drivers of wellbeing and their complex relationships.

Similarly, 47% of publication reporting on the Americas also included at least three health determinants. Research outputs from these two regions demonstrated the most consistently holistic approach to understanding wellbeing compared to other regions. In Africa, only 13% of the papers reviewed incorporated three or more themes; in the Western Pacific, this figure is 32% and in Europe only 8% of research outputs attempted to incorporate three or more themes. It seems unlikely that the multidimensional relationship between socio-economic and ecological sustainability that is always in tension could be adequately explored given the trend towards one-dimensional research in Africa, the Western Pacific and particularly Europe.

The associated positive and negative impacts of heritage tourism on each of the health and wellbeing determinants are then presented in Table 2 , along with the considered policy implications. Some of the identified positive impacts included improved access to education and social services, greater opportunities for skill development and employment prospects, preservation of culture and traditions, increased community livelihood and greater awareness of environmental conservation efforts. Negative impacts of tourism on host communities included forced displacement from homes, environmental degradation and over-usage of natural resources, barriers to tourism employment and reliance on tourism industry for income generation and economic stability, dilution and loss of cultural values and practices, civil unrest and loss of social stability, increased rates of crime and disease and lack of direct benefit to local communities. Both positive and negative impacts across each health and wellbeing determinant had acknowledged implications on policy development, many of which revolved around governance and ownership of tourist activities, participation of the local community in tourism sectors and active management of environmental protection programs. Such themes are shown in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319.t002

Recent thematic trends can be observed in Table 3 , whereby the percentage of research outputs that investigate economic drivers of health and wellbeing produced since 2019 are shown. In Africa, Europe and the Americas, the proportion of outputs investigating economic health determinants since 2019 is the smallest ( Table 3 ), being 17% in Africa and the Americas, and 36% in Europe, respectively. On the contrary, 50% of Western Pacific region studies since 2019 had research focused on the economic drivers of wellbeing in relation to heritage tourism. Moreover, 65% of studies included economy-focused research in South-East Asia, with more than half of those outputs produced in the last two years ( Table 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319.t003

The proportion of research outputs where local community members were asked to give their opinions as participants is presented in Table 4 , where they were invited to co-lead the research but were excluded from data production. In the Western Pacific region, there was a relative lack of participation (either as researchers or stakeholders) by local communities in the studies included in this review. Meaningful modes of community participation in the South-East Asian region can be calculated to 65%, more closely in line with Africa, Europe and the Americas ( Table 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319.t004

This systematic review is the first of its kind to explicitly consider the relationships between heritage tourism and host communities; specifically, the impact of tourism on host communities’ capacity to flourish and support long-term health and wellbeing. Such impacts were found to be both positive and negative, with either direct or indirect consequences on the development of local governance policies. Our synthesis revealed that there are important regional variations in the way that determinants of health–social, cultural, economic or ecological–drive tourism research agendas. They commonly included considerations of social dynamics, access and health of the local community, empowerment and participation of host communities in tourism-based activities and governance, employment opportunities, preservation or erosion of culture, and environmental influences due to tourism promotion or activity.

Economic impacts represented the strongest focus of the studies include in this review, often to the detriment of other cultural or environmental considerations. With the exception of South-East Asia, studies focused on all other WHO regions (Africa, Europe, the Americas and the Western Pacific) were overwhelmingly built around attempts to understand economic variables as determinants of health and wellbeing, and in some instances were likely to focus on economic variables in lieu of any other theme. Given the steady growth of an interest in economic variables in South-East Asia since 2019, it is plausible that this will soon represent the largest concentration of studies in that region, too.

This trend towards emphasis on economic influences is problematic given that some of the emerging impacts from tourism-related practices identified in this review were found to be common across multiple determinants of health and thus not limited to economic health alone. For example, the limitation placed on access to prime grazing land for cattle belonging to local residents was perceived to be a negative impact both ecologically and economically [ 60 , 141 ]. This may be considered detrimental from an environmental standpoint due to the alteration of the local ecosystem and destruction of natural resources and wildlife habitat, such as the building of infrastructure to support the development of tourist accommodation, transport, and experiences.

Economically, the loss of grazing land results in reduced food sources for cattle and consequently a potential reliance on alternative food sources (which may or may not be accessible or affordable), or in the worst-case scenario death of cattle [ 92 ]. In turn, this loss of cattle has an adverse impact on the financial livelihood of host communities, who may rely on their cattle as a sole or combined source of income. Considered in isolation or combination, this single negative impact of tourism–reduced grazing access–has flow-on effects to multiple health determinants. Therefore, it is important to consider the possible multifactorial impacts of tourism, heritage or otherwise, on the host communities involved (or at least affected) given they may have a profound and lasting impact, whether favourable or not.

The potential interrelationships and multifactorial nature of heritage tourism on the health and wellbeing of host communities were also identified among a number of other studies included in this review. For example, a study from the Western Pacific Region explored connections between the analysis of tourism impacts, wellbeing of the host community and the ‘mobilities’ approach, acknowledging the three areas were different in essence but converging areas in relation to tourism sustainability [ 125 ]. That said, the cross-over between social determinants was not always observed or presented as many studies primarily focused on a single health domain [ 43 – 51 , 53 , 55 – 57 , 59 , 61 , 71 , 74 , 86 – 90 , 103 , 104 , 108 – 110 , 118 , 130 , 134 – 136 , 138 – 140 ]. Some studies, for instance, focused on poverty reduction and/or alleviation [ 134 , 135 ], while others focused solely on cultural sustainability or sociocultural factors [ 109 , 110 , 118 ], and others delved only into the ecological or environmental impacts of tourism [ 86 , 89 ]. As noted above, the majority of studies that focused on a single health determinant considered economic factors.

A common theme that spanned multiple health domains was the threat of relocation. Here, local communities represented in the reviewed studies were often at risk of being forced to relocate from their ancestral lands for tourism and/or nature conservation purposes [ 41 , 60 , 80 , 131 ]. This risk not only threatens their way of life and livelihood from an economic perspective, but will also have social implications, jeopardising the sustainability and longevity of their cultural traditions and practices on the land to which they belong [ 41 , 60 , 80 , 131 ]. Moreover, it may have ongoing implications for the displacement of family structures and segregation of local communities.

Importantly, this systematic review revealed that cultural determinants of health and wellbeing were the least explored in every region and were in many instances entirely omitted. This is at odds with the increasingly prevalent advice found in wider heritage and tourism academic debates, where it is argued that cultural institutions such as museums and their objects, for example, may contribute to health and wellbeing in the following ways: promoting relaxation; providing interventions that affect positive changes in physiology and/or emotions; supporting introspection; encouraging public health advocacy; and enhancing healthcare environments [ 142 – 144 ]. Likewise, Riordan and Schofield have considered the cultural significance of traditional medicine, citing its profound importance to the health and wellbeing of the communities who practice it as well as positioning it as a core element of both local and national economies [ 145 ].

Of greater concern is the finding of this review that of the relatively small number of papers investigating cultural health determinants, many recorded profoundly negative and traumatising outcomes of tourism development, such as a rise of ethnoreligious conflict, loss of ancestral land, a dilution of cultural practices to meet tourist demands, and a loss of cultural authenticity [ 41 ]. Consequently, comparative studies that focus on cultural determinants, in addition to economic and environmental determinants, are currently lacking and should therefore be prioritised in future research. In fact, only one fifth of those papers included in this review adopted the qualitative approach needed to probe the socio-cultural dimensions of health. Novel qualitative research methods to investigate community health are therefore a major research lacuna.

Just as solely equating community health and wellbeing with economic flourishing is problematic, so too is assuming that health is reducible only to clinical care and disease [ 146 ], given that "[i]deas about health … are cultural” [ 146 ]. Early indications of an acceptance that culture and heritage might be central to community health and wellbeing can be found in UNESCO’s 1995 report, Our Creative Diversity : Report of the World Commission on Culture and Development [ 147 ]. More recently, this notion is evidenced in the 2019 Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention [ 148 ] and the 2020 Operational Directives for UNESCO’s Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage [ 149 ], both of which indicate the need for a major shift in research foci towards cultural determinants of health and wellbeing if research is to keep pace with assumptions now operating within international policy [ 148 , 149 ].

Although Africa, Europe and the Americas are the three regions with the highest proportion of papers investigating the economic benefits of tourism on health and wellbeing, these regions are also the most responsive to the above recommended changes in policy and debate (see Table 3 ). In these three regions, the proportion of outputs investigating economic health determinants since 2019 is the smallest, demonstrating a recent decline in research that is persuaded by the a priori assumption that economic wellbeing automatically equates to cultural wellbeing. Despite demonstrating the most holistic approach to understanding health and wellbeing across all the themes, an upwards trend in economy-focused research was identified in South-East Asia, since more than half of the economic outputs were produced in the last two years. Such a trend is potentially problematic for this region because it may reinforce the notion that the main benefits of tourism are direct and financial, rather than refocusing on the tension created by indirect effects of tourism on quality of life and community wellbeing.

Conversely, this review demonstrates that the Western Pacific region has persisted with research focused on the economic drivers of wellbeing in relation to heritage tourism (see Table 3 ). This persistence may be explained by the relative lack of participation (either as researchers or stakeholders) by local communities in any of the studies included in this review (see Table 4 ). Indeed, the Western Pacific had the lowest occurrence of community participation and/or consultation in establishing indicators of wellbeing and health and/or opinions about the role of tourism in promoting these.

On the contrary, while seemingly demonstrating the second highest proportion of exclusionary research methods as discussed above, South-East Asia remains the only region where any attempts were made to ensure community members were invited to design and co-lead research (see Table 4 ). Nonetheless, meaningful modes of participation in this region were found to be more closely in line with the deficits found in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. This lack of approaches aimed at including affected communities as researchers in all but one instance in South-East Asia is an important research gap in tourism studies’ engagement with health and wellbeing debates.

Importantly, this failure to adequately engage with affected communities is at odds with the depth of research emanating from a range of health disciplines, such as disability studies, occupational therapy, public health, and midwifery, where the slogan ‘nothing about us without us’, which emerged in the 1980s, remains prominent. Coupled with a lack of focus on cultural determinants of health, this lack of participation and community direction strongly indicates that research studies are being approached with an a priori notion about what ‘wellbeing’ means to local communities, and risks limiting the relevance and accuracy of the research that is being undertaken. Problematically, therefore, there is a tendency to envisage a ‘package’ of wellbeing and health benefits that tourism can potentially bring to a community (regardless of cultural background), with research focusing on identifying the presence or absence of elements of this assumed, overarching ‘package’.

Interestingly, along with the paucity of full and meaningful collaboration with local community hosts in tourism research, there were no instances across the systematic review where a longitudinal approach was adopted. This observation reinforces the point that long-term, collaborative explorations of culturally specific concepts including such things as ‘welfare’, ‘benefit’, ‘healthfulness’ and ‘flourishing’, or combinations of these, are lacking across all regions. To bring tourism research more in line with broader debates and international policy directions about wellbeing, it is important for future research that the qualities of health and wellbeing in a particular cultural setting are investigated as a starting point, and culturally suitable approaches are designed (with local researchers) to best examine the effects of tourism on these contingent notions of wellbeing.

Importantly, a lack of longitudinal research will lead to a gap in our understanding about whether the negative impacts of tourism increase or compound over time. Adopting these ethnographies of health and wellbeing hinges upon long-term community partnerships that will serve to redress a research gap into the longevity of heritage tourism impacts. Furthermore, of those papers that asked local community members about their perceptions of heritage tourism across all regions, a common finding was the desire for greater decision-making and management of the enterprises as stakeholders. It seems ironic, therefore, that research into heritage tourism perceptions itself commonly invites the bare minimum of collaboration to establish the parameters of that research.

In a small number of papers that invited community opinions, local stakeholders considered that the tourism ‘benefits package’ myth should be dispelled, and that responsible tourism development should only happen as part of a wider suite of livelihood options, such as agriculture, so that economic diversity is maintained. Such a multi-livelihood framework would also promote the accessibility of benefits for more of the community, and this poses a significant new direction for tourism research. For example, an outcome of the review was the observation that infrastructure development is often directed towards privileged tourism livelihood options [ 150 ], but a more holistic framework would distribute these sorts of benefits to also co-develop other livelihoods.

Although there is a clear interest in understanding the relationship between heritage, tourism, health and wellbeing, future research that explores the intersections of heritage tourism with multiple health domains, in particular social and cultural domains, is critical. Indeed, the frequency with which the negative impacts of heritage tourism were reported in the small number of studies that engaged local community participants suggests that studies co-designed with community participants are a necessary future direction in order for academics, policymakers and professionals working in the field of heritage tourism to more adequately address the scarce knowledge about its socio-cultural impacts. The accepted importance of community researchers in cognate fields underscores that the knowledge, presence and skills of affected communities are vital and points to the need for similar studies in heritage tourism.

Conclusions

There are five main findings of this systematic review, each of which is a critical gap in research that should be addressed to support the health and wellbeing in local communities at tourism destinations. Firstly, whilst one of the primary findings of this systematic review was the increase in employment opportunities resulting from tourism, this disclosure arose because of a strong–in many cases, exclusive–methodological focus on economic indicators of health and wellbeing. Such research reveals that heritage tourism may significantly reduce poverty and may be used as a poverty-reducing strategy in low-income countries. However, the assumption underlying this focus on the economic benefits of tourism for health and wellbeing is that economic benefits are a proxy for other determinants of health, e.g., cultural, social, environmental, etc., which are otherwise less systematically explored. In particular, the ways in which combinations of environmental, social, cultural, and economic determinants on wellbeing interact is an area requires considerable future research.

Secondly, whilst economic drivers of wellbeing were the most common area of research across all regions, the impacts of tourism on cultural wellbeing were the least explored. Moreover, in many publications culture was entirely omitted. This is perhaps one of the most troubling outcomes of this systematic review, because in the relatively small number of papers that did investigate the cultural impacts of tourism, many reported traumatising consequences for local communities, the documentation of which would not be recorded in the majority of papers where cultural wellbeing was absent. Tourism’s profoundly damaging consequences included reports of a rise in ethnoreligious violence, loss of ancestral land and the threat of forced relocation, not to mentioned extensive reports of cultural atrophy.

Linked to this lack of understanding about the cultural impacts of tourism on wellbeing, the third finding of this review is that there are far fewer studies that incorporate qualitative data, more suited to document intangible cultural changes, whether positive or negative. Furthermore, more longitudinal research is also needed to address the subtle impacts of tourism acting over longer timescales. The systematic review revealed a lack of understanding about how both the negative and positive outcomes of heritage tourism change over time, whether by increasing, ameliorating, or compounding.

The fourth finding of this research is that, to a degree and in certain regions of the world, research is responding to international policy. This review has illustrated that, historically, Africa, Europe and the Americas prioritised research that measured the economic effects of tourism on health and wellbeing. However, after 2019 a shift occurred towards a growing but still under-represented interest in social-cultural wellbeing. We propose that this shift aligns with recommendations from UNESCO’s 2019 Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention [ 148 ] and the 2020 Operational Directives for UNESCO’s Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage [ 149 ]. The exception to this shift is the Western Pacific region, where the economic impacts of tourism are increasingly prioritised as the main indicator of wellbeing. Given the overall efficacy of policy for steering towards ethical and culturally-grounded evaluations of the impacts of tourism, we would urge heritage policymakers to take account of our recommendations ( Table 2 ).

The policy implications emerging from this review are the fifth finding and can be distilled into a few key propositions. There is a need for meaningful decolonising approaches to heritage tourism. More than half of the negative consequences of heritage tourism for health and wellbeing could be mitigated with policy guidance, contingent cultural protocols and anti-colonial methods that foreground the rights of local (including Indigenous) communities to design, govern, lead, and establish the terms of tourism in their local area. Although ‘participation’ has become a popular term that invokes an idea of power symmetries in tourism enterprises, it is clear from this systematic review that the term leaves too much latitude for the creep of poor-practice [ 151 ] that ultimately erodes community autonomy and self-determination. Participation is not enough if it means that there is scope for governments and foreign investors to superficially engage with community wellbeing needs and concerns.

Furthermore, calls for ‘capacity-building’ that effectively re-engineer the knowledges of local communities are fundamentally problematic because they presuppose a missing competency or knowledge. This is at odds with impassioned anti-colonial advocacy [ 152 ] which recognises that communities hold a range of knowledges and cultural assets that they may, and should be legally protected to, deploy (or not) as a culturally-suitable foundation that steers the design of locally-governed tourism enterprises. In short, to maximise and extend the benefits of heritage tourism and address major social determinants of health, host communities’ presence in heritage tourism governance, decision making processes, and control of and access to the resultant community resources and programs must be a priority. Future policymakers are encouraged to make guidance more explicit, enforceable and provision avenues for feedback from local communities that offers the protections of transparency. It is also imperative that researchers involve and empower local community groups as part of studies conducted in relation to their health and wellbeing. If current practices remain unchanged, the primary benefit of tourism could easily be rendered inaccessible through lack of education and/or appropriate training which was frequently identified as a barrier to community participation.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. prisma 2009 checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282319.s001

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Della Maneze (DM) and Nidhi Wali (NW) for their contributions to the literature search and initial data extraction.

Declarations

The authors hereby declare that the work included in this paper is original and is the outcome of research carried out by the authors listed.

- 1. World Tourism Organization. International Tourism Highlights, 2020 Edition. UNWTO, Madrid. 2021. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284422456.2021

- 2. World Tourism Organization. The T4SDG Platform Madrid, Spain. 2022 [cited 2022 October 11]. Available from: https://tourism4sdgs.org/the-platform/ .

- 3. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Sustainable Tourism: UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme. 2021 [cited 2021 June 20]. Available from: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tourism/ .

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 5. Leaver B. Delivering the social and economic benefits of heritage tourism. 2012 [cited 2021 June 28]. Available from: https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/f4d5ba7d-e4eb-4ced-9c0e-104471634fbb/files/essay-benefits-leaver.pdf .

- 7. James P. Creating capacities for human flourishing: an alternative approach to human development. In: Spinozzi P, Mazzanti M, editors. Cultures of Sustainability and Wellbeing: Theories, Histories and Policies; 2018. p. 23–45.

- 9. Paul-Andrews L. Tourism’s impact on the environment: a systematic review of energy and water interventions [Thesis]. Christchurch: University of Canterbury; 2017. Available from: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/13416 .

- PubMed/NCBI

- 31. Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2014 edition. The Joanna Briggs Institute [Internet]. 2014. Available from: https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/Economic.pdf .

- 33. Tyndall J. AACODS checklist. Flinders University [Internet]. 2010. Available from: http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ .

- 38. Noblit GW, Hare RD, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies: Sage; 1988.

- 52. Emptaz-Collomb J-GJ. Linking tourism, human wellbeing and conservation in the Caprivi strip (Namibia) [Ph.D Thesis]: University of Florida; 2009. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/848632295?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true .

- 56. Lepp AP. Tourism in a rural Ugandan village: Impacts, local meaning and implications for development [Ph.D. Thesis]: University of Florida; 2004. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/305181950?accountid=36155 , https://ap01.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/uresolver/61UWSTSYD_INST/openurl?frbrVersion=2&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&ctx_id=10_1&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_ctx_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rfr_id=info:sid/primo.exlibrisgroup.com&req_id=&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:&rft.genre=article&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournalrft.issn=&rft.title=&rft.atitle=&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.date=2004 .

- 58. Mosetlhi BBT. The influence of Chobe National Park on people’s livelihoods and conservation behaviors [Ph.D. Thesis]: University of Florida; 2012. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1370246098?accountid=36155 , https://ap01.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/uresolver/61UWSTSYD_INST/openurl?frbrVersion=2&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&ctx_id=10_1&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_ctx_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rfr_id=info:sid/primo.exlibrisgroup.com&req_id=&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:&rft.genre=article&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournalrft.issn=&rft.title=&rft.atitle=&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.date=2012 .

- 60. Stone MT. Protected Areas, Tourism and Rural Community Livelihoods in Botswana [Ph.D. Thesis]: Arizona State University; 2013. Available from: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/79567367.pdf .

- 61. Lyon A. Tourism and sustainable development: active stakeholder discourses in the waterberg biosphere reserve, South Africa [Ph.D. Thesis]: The University of Liverpool; 2013. Available from: https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/14953/4/LyonAnd_Dec2013_14953.pdf .

- 62. DeLuca LM. Tourism, conservation, and *development among the Maasai of Ngorongoro District, Tanzania: Implications for political ecology and sustainable livelihoods [Ph.D. Thesis]: University of Colorado; 2002. Available from: https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999942945102121 .

- 69. Chazapi K, Sdrali D. Residents perceptions of tourism impacts on Andros Island, Greece. SUSTAINABLE TOURISM 2006: WIT Press; 2006. p. 10.

- 70. Ehinger LT. Kyrgyzstan’s community-based tourism industry: A model method for sustainable development and environmental management? [M.A. Thesis]: University of Wyoming; 2016. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1842421616?accountid=36155 , https://ap01.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/uresolver/61UWSTSYD_INST/openurl?frbrVersion=2&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&ctx_id=10_1&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_ctx_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rfr_id=info:sid/primo.exlibrisgroup.com&req_id=&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:&rft.genre=article&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournalrft.issn=&rft.title=&rft.atitle=&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.date=2016 .

- 74. Labadi S. Evaluating the socio-economic impacts of selected regenerated heritage sites in Europe: European Cultural Foundation; 2011. 129 p.

- 75. McDonough R. Seeing the people through the trees: Conservation, communities and ethno-ecotourism in the Bolivian Amazon Basin [Thesis]: Georgetown University 2009. Available from: https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/558153/McDonough_georgetown_0076M_10335.pdf;sequence=1 .

- 81. Slinger VAV. Ecotourism in a small Caribbean island: Lessons learned for economic development and nature preservation [Ph.D. Thesis]: University of Florida; 2002. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/304798500?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true .

- 86. Barthel DJ. Ecotourism’s Effects on Deforestation in Colombia [M.A. Thesis]: Northeastern Illinois University; 2016. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1793940414?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true .

- 89. Lottig KJ. Modeling resident attitudes on the environmental impacts of tourism: A case study of O’ahu, Hawai’i [M.S. Thesis]: University of Hawai’i; 2007. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/304847568?accountid=36155 , https://ap01.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/uresolver/61UWSTSYD_INST/openurl?frbrVersion=2&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&ctx_id=10_1&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_ctx_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rfr_id=info:sid/primo.exlibrisgroup.com&req_id=&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:&rft.genre=article&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournalrft.issn=&rft.title=&rft.atitle=&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.date=2007 .

- 91. Raschke BJ. Is Whale Watching a Win-Win for People and Nature? An Analysis of the Economic, Environmental, and Social Impacts of Whale Watching in the Caribbean [Ph.D. Thesis]: Arizona State University; 2017. Available from: https://keep.lib.asu.edu/_flysystem/fedora/c7/187430/Raschke_asu_0010E_17442.pdf .

- 94. Bennett N. Conservation, community benefit, capacity building and the social economy: A case study of Łutsël K’e and the proposed national park [M.E.S. Thesis]: Lakehead University (Canada); 2009. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/725870968?accountid=36155 , https://ap01.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/uresolver/61UWSTSYD_INST/openurl?frbrVersion=2&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&ctx_id=10_1&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_ctx_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rfr_id=info:sid/primo.exlibrisgroup.com&req_id=&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:&rft.genre=article&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournalrft.issn=&rft.title=&rft.atitle=&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.date=2009 .

- 104. Rahman M. Exploring the socio-economic impacts of tourism: a study of cox’s bazar, bangladesh [Ph.D. Thesis]: Cardiff Metropolitan University; 2010. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344518546_Exploring_the_Socio-economic_Impacts_of_Tourism_A_Study_of_Cox’s_Bazar_Bangladesh .

- 109. Anggraini LM. Place Attachment, Place Identity and Tourism in Jimbaran and Kuta, Bali [Ph.D. Thesis]: University of Western Sydney; 2015. Available from: https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:32139 .

- 111. Vajirakachorn T. Determinants of success for community-based tourism: The case of floating markets in Thailand [Ph.D. Thesis]: Texas A&M University; 2011. Available from: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/ETD-TAMU-2011-08-9922 .

- 118. Suntikul W. Linkages between heritage policy, tourism and business. ICOMOS 17th General Assembly; Paris, France 2011. p. 1069–76.

- 119. Suntikul W. The Impact of Tourism on the Monks of Luang Prabang. 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the spirit of place–between the tangible and the intangible’; Quebec, Canada 2008. p. 1–14.

- 127. Murray AE. Footprints in Paradise: Ethnography of Ecotourism, Local Knowledge, and Nature Therapies in Okinawa: Berghahn Books; 2012. 186 p.

- 132. Yang JYC, Chen YM. Nature -based tourism impacts in I -Lan, Taiwan: Business managers’ perceptions [Ph.D. Thesis]: University of Florida; 2006. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/305330231?accountid=36155 , https://ap01.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/uresolver/61UWSTSYD_INST/openurl?frbrVersion=2&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&ctx_id=10_1&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_ctx_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rfr_id=info:sid/primo.exlibrisgroup.com&req_id=&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:&rft.genre=article&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournalrft.issn=&rft.title=&rft.atitle=&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.date=2006 .

- 137. Refaat H, Mohamed M. Rural tourism and sustainable development: the case of Tunis village’s handicrafts, Egypt". X International Agriculture Symposium "AGROSYM 2019"; 3–6 October 2019; Bosnia and Herzegovina 2019. p. 1670–8.

- 141. Thinley P. Empowering People, Enhancing Livelihood, and Conserving Nature: Community Based Ecotourism in JSWNP, Bhutan and TMNP, Canada [M.Phil. Thesis]: University of New Brunswick; 2010. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1027149064?accountid=36155 , https://ap01.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/uresolver/61UWSTSYD_INST/openurl?frbrVersion=2&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&ctx_id=10_1&ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_ctx_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rfr_id=info:sid/primo.exlibrisgroup.com&req_id=&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:&rft.genre=article&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournalrft.issn=&rft.title=&rft.atitle=&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.date=2010 .

- 147. World Commission on Culture and Development. Our creative diversity: report of the World Commission on Culture and Development. Paris: UNESCO: 1995.

- 148. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Paris: UNESCO: 2019.

- 149. UNESCO. Operational Directives for the Implementation of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO: 2020.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 15 August 2023

People’s perspectives on heritage conservation and tourism development: a case study of Varanasi

- Ananya Pati 1 &

- Mujahid Husain 2

Built Heritage volume 7 , Article number: 17 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2530 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The conservation of heritage and heritage-based tourism are interrelated activities in which the development in one can lead to the growth of the other and vice versa. In recent years, people have become increasingly aware of the importance of heritage and the necessity of its conservation. People’s knowledge and preservation of their roots and emotional attachments to traditions and places are beneficial for heritage conservation activities. Heritage places are also considered a growth point for the tourism industry that supports small- and medium-scale industries as well as numerous cottage industries. However, with the development of tourism and related industries in heritage areas, the local community may face difficulties in performing their day-to-day activities in the area. In many cases, local communities need to relocate and people must leave their residences due to the demand for tourism development. A case study of Varanasi City was conducted to obtain a detailed understanding of the impact of a recent tourism development programme (the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor Project) and people’s perception of it through a review of newspaper articles. It was found that people had mixed reactions regarding the development programme. The immediate residents of the area who were directly affected by the process in terms of emotional, economic and social loss were opposed to the project, while tourists and other residents of the city were pleased with the development activities. This paper attempts to identify the changes that occurred in the area due to the project and to capture people’s perspectives regarding the corridor project of Varanasi.

1 Introduction

The heritage of a country is a symbol of its national pride and produces cohesiveness and unity among the people. The importance of heritage and culture has increased significantly in recent years, particularly in the tourism sector. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), ‘Cultural heritage is, in its broadest sense, both a product and a process, which provides societies with a wealth of resources that are inherited from the past, created in the present and bestowed for the benefit of future generations’ (UNESCO 2014 ). Most importantly, it includes not only tangible but also natural and intangible heritage. As Our Creative Diversity notes, however, these resources are a ‘fragile wealth’. As such, they require policies and development models that preserve and respect their diversity and uniqueness since they are ‘nonrenewable’ once lost. Modernisation and urbanisation spread rapidly worldwide during the past century, but people are now leaning towards their heritage to maintain the individuality and uniqueness of their communities and to present this uniqueness to the otherwise modern and developed world (Napravishta 2018 ). People have recognised the enormous potential of heritage and culture in the tourism industry and for economic and social development. Numerous industries consider heritage and culture to be a significant growth point for development and economic benefits (Xing et al. 2013 ). Although the growth of tourism may be considered beneficial for selected groups, in many cases, development and changes made with the goal of tourism development create significant negative effects on the host community, its culture and the heritage itself (Erbas 2018 ). The concept of heritage is based on its historical architecture and monuments, but it is also the heritage values and culture of the residents that have become part of their daily life. This combination of tangible and intangible heritage, called ‘fields of heritage’, is considered a capital stock worthy of conservation (Al-hagla 2010 ). In several cases, excessive tourist influx forces the local community to change its way of life and disrupts the day-to-day activities of the community. In other cases, a complete change of landscape due tourism development creates environmental and cultural degradation. One of the problems of tourism development is that it fails to maintain a balance between the goal of achieving an increased number of tourists and its impact on the existing heritage and the community (Erbas 2018 ). In planning for heritage cities, urban development dynamics and tourism development are equally important factors. In areas with historical backgrounds, the conservation of the existing environment must be the primary concern (Erbas 2018 ).

1.1 Aim and objective

This paper conducts a study of the Kashi Vishwanath Temple Corridor project using an analysis of culture-led tourism and heritage conservation. The Kashi Vishwanath temple corridor project is considered a perfect case study to analyse conflicts between the host community (local dwellers) of the city and the development programme aimed towards the betterment of the pilgrims and tourists who come to the heritage city. The main objective of the study is to assess the perspective of the local community on tourism-led development. A second objective is to understand the pros and cons of tourism-led developments in a heritage city.

While the case study in this paper is based on a recent occurrence, there has been little research on the effects of the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor Project. Although this development project affects only a small portion of the city, the area is heavily populated; therefore, the effects on the locals are significant. This situation must be addressed from the perspectives of the diverse groups who benefited or were harmed by the development initiative.

1.2 The project details

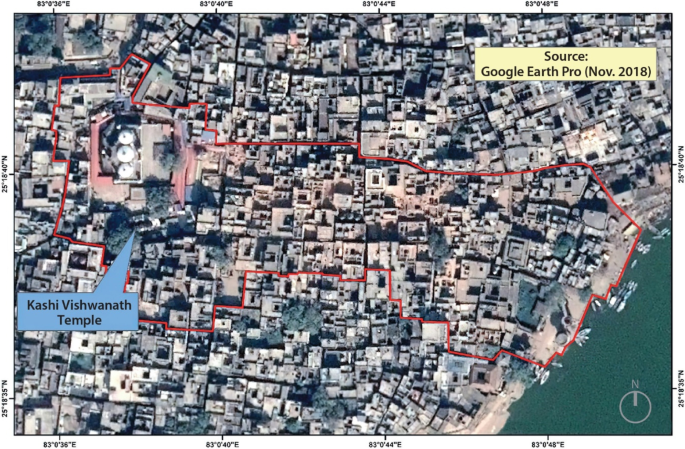

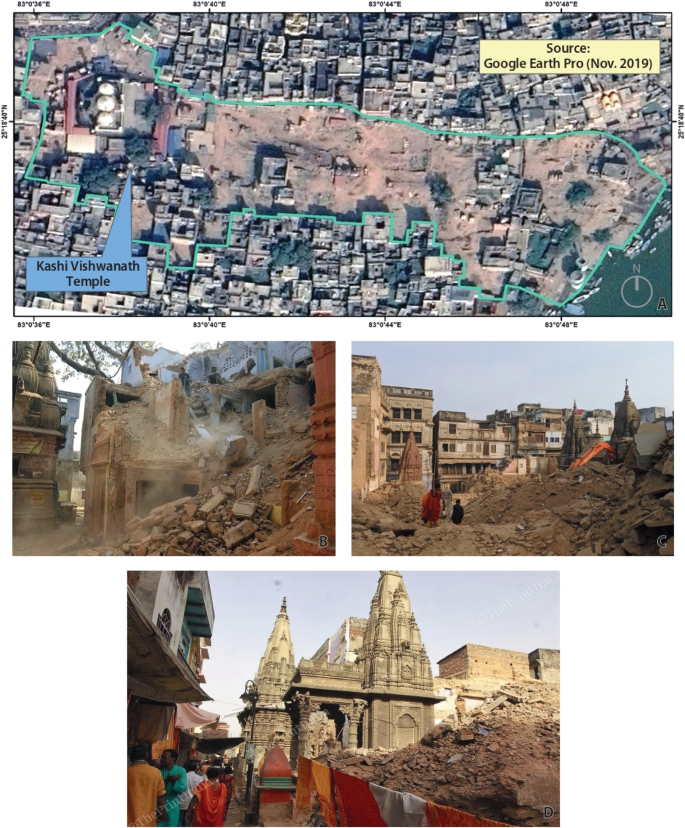

The project of the Kashi Vishwanath temple corridor aimed to connect the Vishwanath Temple with the Ghats of Ganges. The pathway would connect the Manikarnika and Lalita ghat to the temple (Fig. 1 ), and the temple would be visible from the river front (Singh 2018 ). The temple, which is located 400 m from the ghats, was accessible to visitors only by narrow lanes (gali) through a crowded neighbourhood. The project mainly focused on building a wider and cleaner road and stairs with bright lights from the ghats to the temple. Because tourists and pilgrims come to Varanasi mainly to visit the older part of the city (i.e., the ghats of Ganges and the Vishwanath Temple), a connecting corridor would be of great use to them. By making the temple accessible to pilgrims and tourists through waterways, tourists could reach the temple ghat from the Khidkiya ghat and Raj ghat via a boat ride. The project also aimed to build stairways and escalators to reach the temple (Pandey and Jain 2021 ). This major makeover of the Vishwanath temple was the first since 1780. The Maratha queen of Indore, Ahilyabai Holker, renovated the Vishwanath temple and its surroundings, but no major changes have occurred in this area since then.

Kashi Vishwanath Corridor after Completion, 12 December 2021 (Source: NDTV.com)

The project was launched in 2018, and the work was initiated in March 2019. The project known as Kashi Vishwanath Mandir Vistarikaran-Sundarayakaran Yojana (Kashi Vishwanath Temple extension and beautification plan) was estimated at Rs. 400 crore. According to the plan for redevelopment, an area of 43,636 sq. m was cleared by demolishing all the construction between the river and the ancient shrine (Ghosh 2018 ). A development board was created to accomplish the plan. To create this huge space, 314 properties were bought and demolished by the board. A total of Rs. 390 crore was spent to acquire the properties that were selected for the project in the area. Of this Rs. 390 crore, a sum of Rs. 70 crore was allotted for the rehabilitation of the 1,400 people living in this area, who were mainly encroachers, vendors and shopkeepers (Tiwari 2021 ).

The narrow lanes and the surroundings that were demolished for the project were known as Lahoritola, Neelkanth and Brahamanal (Singh 2018 ). The neighbourhood of Lahoritola is one of the oldest parts of Varanasi City. The first settlers migrated to this place from Lahore during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Currently, the sixth generation of the original settlers are living in this area, but as the area was cleared for the project, they had no other option but to settle somewhere else (Ghosh 2018 ). The project has specific planning for people affected by it. According to the authorities, rehabilitation houses are to be built at Ramnagar on eight acres of government land. Shopkeepers affected by the process are to be allotted shops near the temple after the completion of the project (Singh 2018 ).

The project aims not only to create a wide corridor connecting the temple to the ghat but also to develop several buildings for various tourism purposes. The Kashi Vishwanath temple complex will have 23 new structures after the completion of the plan. Along with the construction of a new temple chowk, these structures will include a tourist information centre, salvation house, city gallery, guest house, multipurpose hall, locker room, bhog shala, tourist facilitation centre, Mumukshu Bhaban, vedic kendra, city museum, food court, viewing gallery, and restroom (Tiwari 2021 ). The Ganga View gallery will provide a clear panoramic view for tourists. According to officials, the Mandir Chawk will be a place for pilgrims to relax and meditate (Pandey and Jain 2021 ). After the completion of the corridor and other proposed buildings, the temple complex will have 50,000 sq. ft. of space, which is approximately 200 times larger than the previous area of the temple complex. According to authorities, the space of the entire temple complex will be able to manage 50,000 to 75,000 pilgrims at a time, compared to a few hundred previously. The project has also considered the importance of green cover, and it was decided that 70% of the total 5.50 lakh sq. ft. will be green (Tiwari 2021 ). With the completion of the project, it is believed that there will be a boost in tourism, and the attraction of the heritage of the city will increase substantially.

2 Literature review