Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

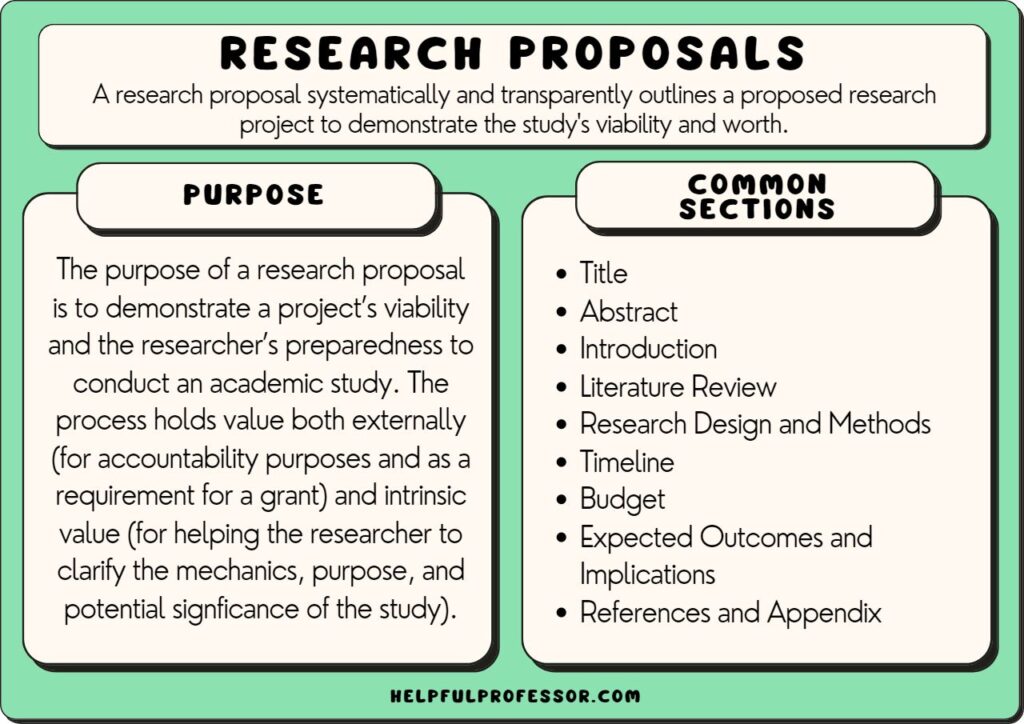

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

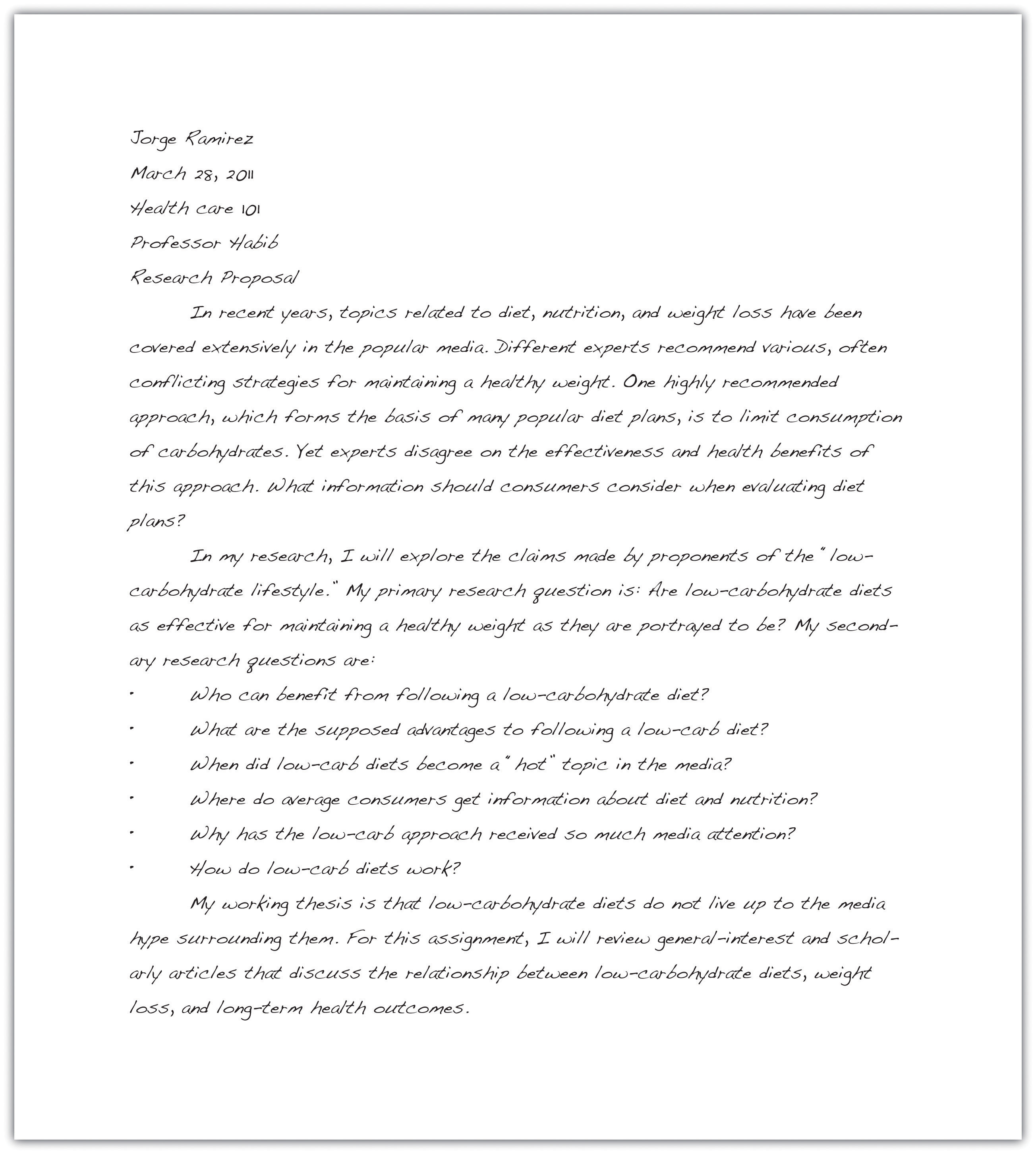

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Writing a Research Proposal

- Purpose of Guide

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- The Research Problem/Question

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Evaluating Sources

- Reading Research Effectively

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Is it Peer-Reviewed?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism [linked guide]

- Annotated Bibliography

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

The goal of a research proposal is to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting the research are governed by standards within the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, so guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and/or benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to ensure a research problem has not already been answered [or you may determine the problem has been answered ineffectively] and, in so doing, become better at locating scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of doing scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those results. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your writing is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to research.

- Why do you want to do it? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of study. Be sure to answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to do it? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having trouble formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here .

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise; being "all over the map" without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review.

- Failure to delimit the contextual boundaries of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.].

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research.

- Failure to stay focused on the research problem; going off on unrelated tangents.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal . The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal . Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal . International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal . University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing a regular academic paper, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. Proposals vary between ten and twenty-five pages in length. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like--"Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

In general your proposal should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea or a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in one to three paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Why is this important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This section can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. This is where you explain the context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is relevant to help explain the goals for your study.

To that end, while there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing. Answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care].

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what is excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, where stated, their recommendations. Do not be afraid to challenge the conclusions of prior research. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study in relation to that of other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you read more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

To help frame your proposal's literature review, here are the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.] .

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that it is worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research operations you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results of these operations in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that a methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is an argument as to why these tasks add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method is perfect so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your reader.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal . Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal . The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal . International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal . University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Purpose of Guide

- Next: Types of Research Designs >>

- Last Updated: Sep 8, 2023 12:19 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.txstate.edu/socialscienceresearch

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.4: The Body of the Research Proposal

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 180380

Drawing on guidelines developed in the UBC graduate guide to writing proposals (Petrina, 2009), we highlight eight steps for constructing an effective research proposal:

- Presenting the topic

- Literature Review

- Identifying the Gap

- Research Questions that addresses the Gap

- Methods to address the research questions

Data Analysis

- Summary, Limitations and Implications

In addition to those eight sections, research proposals frequently include a research timeline. We discuss each of these eight sections as well as producing a research timeline below.

Presenting The Topic (Statement of Research Problem)

The research proposal should begin with a hook to entice your readers. Like a steaming fresh pie on a windowsill, you want to allure your reader by presenting your topic (the pie on the sill) and then alluding to its importance (the delicious scent and taste of the cooling cherry pie). This can be done in many ways, so long as you are able to entice your reader to the core themes of your research. Some suggestions include:

Highlighting a paradox that your work will attempt to resolve e.g., “Why is it that social research has been shown to bring about higher net-positive outcomes than natural scientific research, but is funded less?” or “Why is it that women earn less than men in meritocratic societies even though they have more qualifications?” Paradoxes are popular because they draw on problematics (see Chapter 1) and indicate an obstacle in the thinking of fellow researchers that you may offer hope in resolving.

- Presenting a narrative introduction (often used in ethnographic papers) to the problem at hand. The following opening statement from Bowen, Elliott & Brenton (2014, p. 20) illustrates:

It’s a hot, sticky Fourth of July in North Carolina, and Leanne, a married working-class black mother of three, is in her cramped kitchen. She’s been cooking for several hours, lovingly preparing potato salad, beef ribs, chicken legs, and collards for her family. Abruptly, her mother decides to leave before eating anything. “But you haven’t eaten,” Leanne says. “You know I prefer my own potato salad,” says her mom. She takes a plateful to go anyway,

- Provide an historical overview of the problem, discussing its significance in history and indicating how that interrelates to the present: “On January 23rd, 2020, tears were shed as cabbies heard the news of Uber’s approval to operate in the city of Vancouver.”

- Introduce your positionality to the problem: How did it come of concern? How are you personally related to the social problem in question? The following introduction by Germon (1999, p.687) illustrates:

Throughout the paper I locate myself as part of the disabled peoples movement, and write from a position of a shared value base and analyses of a collective experience. In doing so, I make no apology for flouting academic pretentions of objectivity and neutrality. Rather, I believe I am giving essential information which clarifies my motivation and political position

- Begin with a quotation : Because this is an overused technique, if you use it, make sure that it addresses your research question and that you can explicitly relate to it in the body of your introduction. Do not start with a quotation for the sake of.

- Begin with a concession : Start with a statement recognizing an opinion or approach different from the one you plan to take in your thesis. You can acknowledge the merits in a previous approach but show how you will improve it or make a different argument, e.g., “Although critical theory and antiracism explain oppression and exploitation in contemporary society, they do not fully address the experiences of Indigenous peoples”.

- Start with an interesting fact or statistics : This is a sure way to draw attention to the topic and its significance e.g. “Canada is the fourth most popular destination country in the world for international students in 2018, with close to half a million international students” (CBIE, 2018)

- A definition : You may start by defining a key term in your research topic. This is useful if it distinguishes how you plan to use a term or concept in your thesis.

The above strategies are not exhaustive nor are they only applicable to the introduction of your research proposal. They can be used to introduce any section of your thesis or any paper. Regardless of the strategy that you use to introduce your topic, remember that the key objective is to convince your reader that the issue is problematic and is worth investigating. A well developed statement of research problem will do the following:

- Contextualize the problem . This means highlighting what is already known and how it is problematic to the specific context in which you wish to study it. By highlighting what is already known, you can build on key facts (such as the prevalence and whether it has received attention in the past). Please note that this is not the literature review; you are simply fleshing out a few pertinent details to introduce the topic in a few sentences or a paragraph.

- Specify the problem by describing precisely what you plan to address. In other words, elaborate on what we need to know. For example, building on your contextualization of the problem, you can specify the problem with a statement such as: “There is an abundance of literature on international migration. In fact, the IOM (2018) estimates that there are close to 258 million international migrants globally, who contribute billions to the global economy. However, not much is known about the extent of intra-regional migration in the global south such as within the African continent. There is, hence, a pressing need to study this phenomenon in greater detail.”

- Highlight the relevance of the problem . This means explaining to the readers why we need to know this information, who will be affected, who will benefit?

- Outline the goal and objectives of the research.

- The goal of your research is what you hope to achieve by answering the research question. To write the goal of your research, go back to your research question and state the results you intend to obtain. For example, if your research question is “What effect does extended social media use have on female body images?”, the goal of your research could be stated as “The goal of this study is to identity the point at which social media use negatively impact female body images so that they can be informed about how to use it responsibly.

- The objectives of your study is a further elaboration on your goals i.e., details about the steps that you will take to achieve the goal. Based on the goal above, you probably will study incidents of depression among female social media users, changes in self-esteem and incidents of eating disorders. These could translate into objectives such as to: (1) compare the incidents of depression among female social media users based on length of use (2) assess changes in female social media users’ self esteem (3) determine if there are differences in the incidents of eating disorder among female social media users based on extent of use. Notice that in achieving those objectives, you will be able to reach the goal of answering your research question.

In summary, you should strive to have one goal for each research question. If your project has only one research question, one goal is sufficient. Your objectives are the pathways (or steps) that will get you to achieve the goal i.e., what will you need to do in order to answer the research question. Summarize the steps in no more than two or three objectives per goal.

Brief Literature Review

After the problem and rationale are introduced, the next step is to frame the problem within the academic discourse. This involves conducting a preliminary literature review covering, inter alia, the history of the phenomena itself and the scholarly theories and investigations that have attempted to understand it (Petrina, 2009). In elaborating on the history of the concepts and theories, you should also attempt to draw attention to the theories which will guide your own research (or which will be contested by your research). By foregrounding the major ways of perceiving the problem, you will then set the stage for your own methodology: the major concepts and tools you will use to investigate/interpret the problem.

While in graduate research proposals the literature review often composes a section of its own (Petrina, 2009), in undergraduate research this step can be incorporated into the introduction. However, you should avoid, as Wong (n.d.) writes, framing your research question “in the context of a general, rambling literature review,” where your research question “may appear trivial and uninteresting.” Try to respond to seminal papers in the literature and to identify clearly for your reader the key concepts in the literature that you will be discussing. Part of outlining the scholarly discussion should also focus on clarifying the boundaries of your topic. While making the significance concrete, try to hone in on select themes that your research will evaluate. This way, when you go to outline the methods you will use, the topic will have clearly defined boundaries and concerns. See chapter 5 for more guidance on how to construct an extended literature review.

Box 2.1 – Tips for the Literature Review

- Summarize : The literature in your literature review is not going to be exhaustive but it should demonstrate that you have a good grasp on key debates and trends in the field

- Quality not quantity : Despite the fact that this is non-exhaustive, there is no magic number of sources that you need. Do not think in terms of how many sources are sufficient. Think about presenting a decent representation of key themes in the literature.

- Highlight theory and methodology of your sources (if they are significant). Doing so could help justify your theoretical and methodological decisions, whether you are departing from previous approaches or whether you are adopting them.

- Synthesize your results. Do not simply state “According to Robinson (2021)….According to Wilson (2021)… etc”. Instead, find common grounds between sources and summarize the point e.g., “Researchers argue that we should not list our literature (Bartolic, 2021; Robinson, 2020; Wilson 2021).

- Justify methodological choice

- Assess and Evaluate: After assessing the literature in your field, you should be able to answer the following questions: Why should we study (further) this research topic/problem?

- Contribution : At the end of the literature, you should be able to determine contributions will my study make to the existing literature?

As you briefly discuss the key literature concerning your topic of interest, it is important that you allude to gaps. Gaps are ambiguities, faults, and missing aspects of previous studies. Think about questions that you have which are not answered by existing literature. Specifically, think about how the literature might insufficiently address the following, and locate your research as filling those gaps (see UNE, 2021):

- Population or sample : size, type, location, demography etc. [Are there specific populations that are understudied e.g., Indigenous people, female youth, BIPOC, the elderly etc.]

- Research methods : qualitative, quantitative, or mixed [Has the research in the area been limited to just a few methods e.g., all surveys? How is yours different?]

- Data analysis [Are you using a different method of analysis than those used in the literature?]

- Variables or conditions [Are you examining a new or different set of variables than those previously studied? Are the conditions under which your study is being conducted unique e.g., under pandemic conditions]

- Theory [Are you employing a theory in a new way?]

Refer to Chapter 6 (Literature Review) for more detail about this process and for a discussion on common types of gaps in social research.

Box 2.2 – Identifying a Gap

To indicate the usefulness and originality of your research, you should be conscious of how your research is both unique from previous studies in the field and how its findings will be useful. When you write your thesis or research report, you will expound on these gaps some more. However, in the body of your proposal, it is important that you explicitly highlight the insufficiency of existing literature (i.e. gaps). Below are some phrases that you can use to indicate gaps:

- …has not been clarified, studied, reported, or elucidated

- further research is required or needed

- …is not well reported

- key question(s) remains unanswered

- it is important to address …

- …poorly understood or known

- Few studies have (UNE, 2021)

Research Questions & Research Questions that Address the Gap

The gaps and literature you outline should set the context for your research questions. In outlining the major issues concerning your topic, you should have raised key concepts and actors (Wong, n.d.). Your research question should attempt to engage or investigate the key concepts previously stated, showing to your reader that you have developed a line of inquiry that directly touches upon gaps in the previous literature that can be concretely investigated (ie. concepts that are operationalized). After indicating what your research intends to study, formulate this gap into a set of research questions which make investigating this gap tangible. Refer to the previous chapter for more advice about devising a solid research question. Remember, as McCombes (2021) notes, a good research question is:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis (i.e., not answerable with a simple yes/no)

- Provide scope for debate Original (not one that is answered already)

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly.

Methods to Address Research Questions

By the time you begin writing your methodology section, you would have already introduced your topic and its significance, and have provided a brief account of its scholarly history (literature review) and the gaps you will be filling. The methods section allows you to discuss how you intend to fulfill said gap. In the methods section, you also indicate what data you intend to investigate (content: including the time, place, and variables) and how you intend to find it (the methods you will use to reveal content e.g., qualitative interviewing, discourse analysis, experimental research, and comparative research). Your ability to outline these steps clearly and plausibly will indicate whether your research is repeatable, possible, and effective. Repeatable research allows other researchers to repeat your methods and find the same results (Bhattacherjee, 2012), thereby proving that your findings were not invented but are discoverable by all. Your descriptions must be specific enough so that other researchers can repeat them and arrive at the same results. It is important in this section that you also justify why you believe this specific methodology is the most effective for answering the research question. This does not need to be extensive, but you should at least briefly note why you think, for instance, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods (and your specific proposed approach) are appropriate for answering your research question. For more details about writing an immaculate methodology, refer to Chapter 7.

This short section requires you to discuss how you intend to interpret your findings. You will need to ask yourself five critical questions before you write this section: (1) will theory guide the interpretation of the results? (2) Will I use a matrix with pre-established codes to categorize results? (3) Will I use an inductive approach such as grounded theory that does not go into an investigation with strict codes? (4) Will I use statistics to explain trends in numerical data? (5) Will I be using a combination of these or another strategy to interpret my findings?This section should also include some discussion of the theories that you intend to use to possibly explain or understand your data. Be sure to outline key notions and explain how they will be operationalized to extrapolate the data you may receive. Again, this section also does not have to be extensive. At this point, you are demonstrating that you have given thought to what you intend to do with the data once you have collected it. This may change later on, but make sure that the proposed analytical strategy is appropriate to the data collected, for example, if you are evaluating newspaper discourse on the coronavirus pandemic, unless you intend to code the data quantitatively, you would not be expected to use statistics. Content, thematic or discourse analysis might be more intuitive. See the Data Analysis (Chapters 9 and 10) for more details.

Summarize, Engage with Limitations, and Implicate

After you have outlined the literature, the gaps in the literature, how you intend to investigate that gap, and how you intend to analyze what you have found, it is important to again reiterate the significance of your study. Allude to what your study could find and what this would mean . This requires returning to the significant territory that began your proposal and linking it to how your study could help to explain/change this understanding or circumstance. Report on the possible beneficial outcomes of your study. For instance, say you study the impact of welfare checks on homelessness. Then you could respond to the following question: How could my findings improve our responses to homelessness? How could it make welfare policies more effective? Remember you must explain the usefulness or benefits of the study to both the outside world and the research community. In addition to noting your strengths, also reflect on the weaknesses. All research has limitations but you need to demonstrate that you have taken steps to mitigate those that can be mitigated and that the research is valuable despite the weaknesses. Be straightforward about the things your study will not be able to find, and the potential obstacles that will be presented to you in conducting your study (in research that is conducted with a population, be sure to note harms/benefits that might come to them). With this in mind, try to address these obstacles to the best of your ability and to prove the value of your study despite inevitable tradeoffs. However, do not finish with a long list of inadequacies. End with a magnanimous crescendo –with the impression that despite the trials and limitations of research, you are prepared for the challenge and the challenge is well worth overcoming. This means reiterating the significance, potential uses and implications of the findings.

Box 2.3 – Seven Tips for Getting Started with Your Proposed Methodology

- Introduce the overall methodological approach (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, mixed)

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design (e.g., setting, participants, data collection process)

- Describe the specific methods of data collection (e.g., interviews, surveys, ethnography, secondary data etc.)

- Explain how you intend to analyze and interpret your results (i.e. statistical analysis, grounded theory; outline any theoretical framework that will guide the analysis; see below ).

- If necessary, provide background and rationale for unfamiliar methodologies.

- Highlight the ethical process including whether institutional ethics review was done

- Address potential limitations ( see below )

Bhattacherjee, Anol. (2012). Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices Textbooks Collection. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1002&context=oa_textbooks

Bowen, S., Elliott, S., & Brenton, J. (2014). The joy of cooking? Contexts , 13(3), 20-25.

CBIE [Canadian Bureau for International Education] (2018, August). International students in Canada . https://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/International-Students-in-CanadaENG.pdf

Germon, P. (1999). Purely academic? Exploring the relationship between theory and political activism. Disability & Society, 14(5), 687-692.

International Organization on Migration. (2018). “Global Migration Indicators.” global_migration_indicators_2018.pdf (iom.int)

McCombes, S. (2021, March 22). Developing Strong Research Questions: Criteria and Examples. Scribbr . https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-questions/

UNE (2021). Gaps in the literature. UNE Library services. https://library.une.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Gaps-in-the-Literature.pdf

Petrina, Stephen. (2009). “Thesis Dissertation and Proposal Guide For Graduate Students.”

https://edcp-educ.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2013/08/researchproposal1.pdf

How to write a Research Proposal: Explained with Examples

At some time in your student phase, you will have to do a Thesis or Dissertation, and for that, you will have to submit a research proposal. A Research Proposal in its most basic definition is a formally structured document that explains what, why, and how of your research. This document explains What you plan to research (your topic or theme of research), Why you are doing this research (justifying your research topic), and How you will do (your approach to complete the research). The purpose of a proposal is to convince other people apart from yourself that the work you’re doing is suitable and feasible for your academic position.

The process of writing a research proposal is lengthy and time-consuming. Your proposal will need constant edits as you keep taking your work forward and continue receiving feedback. Although, there is a structure or a template that needs to be followed. This article will guide you through this strenuous task. So, let’s get to work!

Research Proposal: Example

[ Let us take a running example throughout the article so that we cover all the points. Let us assume that we are working on a dissertation that needs to study the relationship between Gender and Money. ]

The Title is one of the first things the reader comes across. Your title should be crisp yet communicate all that you are trying to convey to the reader. In academia, a title gets even more weightage because in a sea of resources, sometimes your research project can get ignored because the title didn’t speak for itself. Therefore, make sure that you brainstorm multiple title options and see which fits the best. Many times in academic writing we use two forms of titles: the Main Title and the Subtitle. If you think that you cannot justify your research using just a Title, you can add a subtitle which will then convey the rest of your explanation.

[ Explanation through an example: Our theme is “Gender and Money”.

We can thus keep our title as: A study of “Gendered Money” in the Rural households of Delhi. ]

Insider’s Info: If you are not confident about your title in your research proposal, then write “Tentative Title” in brackets and italic below your Title. In this way, your superiors (professor or supervisor) will know that you are still working on fixing the title.

Overview / Abstract

The overview, also known as abstract and/or introduction, is the first section that you write for your proposal. Your overview should be a single paragraph that explains to the reader what your whole research will be about. In a nutshell, you will use your abstract to present all the arguments that you will be taking in detail in your thesis or research. What you can do is introduce your theme a little along with your topic and the aim of your research. But beware and do not reveal all that you have in your pocket. Make sure to spend plenty of time writing your overview because it will be used to determine if your research is worth taking forward or reading.

Existing Literature

This is one of the most important parts of your research and proposal. It should be obvious that in such a huge universe of research, the topic chosen by you cannot be the first of its kind. Therefore, you have to locate your research in the arguments or themes which are already out there. To do so, what you have to do is read the existing literature on the same topic or theme as yours. Without reading the existing literature you cannot possibly form your arguments or start your research. But to write the portion of existing literature you have to be cautious. In the course of your dissertation, at some point either before or after you submit your proposal, you will be asked to submit a “Literature Review”. Though it is very similar to existing literature, it is NOT the same.

Difference between “Literature Review” and “Existing Literature”

A literature review is a detailed essay that discusses all the material which is already out there regarding your topic. For a literature review, you will have to mention all the literature you have read and then explain how they benefit you in your field of research.

Whereas, an existing literature segment in your research proposal is the compact version of a literature review. It is a two to three-paragraph portion that locates your research topic in the larger argument. Here you need not reveal all your literature resources, but only mention the major ones which will be recurring literature throughout your research.

[ Explanation through an example: Now we know that our topic is: Our theme is “A study of “Gendered Money” in the Rural households of Delhi.”

To find the existing literature on this topic you should find academic articles relating to the themes of money, gender, economy, income, etc. ]

Insider’s Info : There is no limit when it comes to how much you read. You can read 2 articles or 20 articles for your research. The number doesn’t matter, what matters is how you use those concepts and arguments in your own thesis.

Research Gap

As you read and gather knowledge on your topic, you will start forming your own views. This might lead you to two conclusions. First, there exists a lot of literature regarding the relationship between gender and money, but they are all lacking something. Second, in the bundle of existing literature, you can bring a fresh perspective. Both of these thoughts help you in formulating your research gap. A research gap is nothing but you justifying why you should continue with your research even when it has been discussed many times already. Quoting your research gap helps you make a place for yourself in the academic world.

Based on 1st Conclusion, you can say that the research gap you found was that most of the studies done on the theme of gendered money looked at the urban situation, and with your analysis of ‘rural’ households, you will fill the gap.

Based on 2nd Conclusion, you can say that all the existing literature is mostly written from the economic point of view, but through your research, you will try to bring a feminist viewpoint to the theme of gendered money. ]

Insider’s Info : If you are unable to find a research gap for your dissertation, the best hack to fall back on is to say that all the research done up to this point have been based on western notions and social facts, but you will conduct research which holds in your localized reality.

Research Question / Hypothesis

Once you are sorted with your existing literature and have located your research gap, this section will be the easiest to tackle. A research question or hypothesis is nothing but a set of questions that you will try and answer throughout the course of your research. It is very crucial to include research questions in your proposal because this tells your superiors exactly what you plan to do. The number of questions you set for yourself can vary according to the time, resources, and finances you have. But we still recommend that you have at least three research questions stated in your proposal.

[ Explanation through an example: Now that we know what our topic is: our theme is “A study of “gendered money” in the rural households of Delhi.”

Some of the research questions you can state can be,

- Study the division for uses of wages, based on who earned it and where it is getting utilized.

- How gender relations also play a role within the household not only in the form of kinship but in the indirect form of economics as well.

- How, even when we have the same currency signifying the meaning of money, it changes according to the source of who earned it.

- How moral values and judgments are added to the money comes from different sources. ]

Insider’s Info: If you are confused about your research question, you can look at the questions taken up by the other authors you studied and modify them according to your point of view. But we seriously recommend that the best way to do your research is by coming up with your research question on your own. Believe in yourself!

Research Methodology / Research Design

This part of the research proposal is about how you will conduct and complete your research. To understand better what research methodology is, we should first clarify the difference between methodology and method. Research Method is the technique used by you to conduct your research. A method includes the sources of collecting your data such as case studies, interviews, surveys, etc. On the other hand, Methodology is how you plan to apply your method . Your methodology determines how you execute various methods during the course of your dissertation.

Therefore, a research methodology, which is also known as research design, is where you tell your reader how you plan to do your research. You tell the step-by-step plan and then justify it. Your research methodology will inform your supervisor how you plan to use your research tools and methods.

Your methodology should explain where you are conducting the research and how. So for this research, your field will be rural Delhi. Explain why you chose to study rural households and not urban ones. Then comes the how, some of the methods you might want to opt for can be Interviews, Questionnaires, and/or Focused Group Discussions. Do not forget to mention your sample size, i.e., the number of people you plan to talk to. ]

Insider’s Info: Make sure that you justify all the methods you plan to use. The more you provide your supervisor with a justification; the more serious and formal you come out to be in front of them. Also, when you write your why down, it is hard to forget the track and get derailed from the goal.

This will not even be a section, but just 2 lines in your proposal where you will state the amount of time you plan to complete your dissertation and how you will utilize that time. This portion can also be included in your “Research Methodology” section. We have stated this as a separate subheading so that you do not miss out on this small but mighty aspect.

For this project, you can mention that you will be allocated 4 months, out of which 1 month will be utilized for fieldwork and the rest would be used for secondary research, compilation, and completion of the thesis. ]

Aim of the Research

The aim of the research is where you try to predict the result of your research. Your aim is what you wish to achieve at the end of this long process. This section also informs your supervisor how your research will be located in the ongoing larger argument corresponding to your selected topic/theme. Remember the research questions you set up for yourself earlier? This is the time when you envision answers to those questions.

You can present that through your research you will aim to find if the money which enters the household belongs equally to everyone, or does it get stratified and gendered in this realm. Through this research, you aim to present a fresh new perspective in the field of studies of gendered money. ]

Insider’s Info: The aim you write right now is just a prediction or the expected outcome. Therefore, even if the result of your research is different in the end it doesn’t matter.

Bibliography

The bibliography is the easiest and most sorted part of your proposal. It is nothing but a list of all the resources that you will study or already have studied for the completion of your research. This list will contain all the articles or essays mentioned by you in the existing literature section, and all the other things such as books, journal articles, reviews, news, etc.

The most basic format to write a bibliography is:

- Author’s Name with Surname mentioned first, then initials (Tiwari, E.)

- Article’s Title in single or double quotes ( ‘ ’ or “ ” )

- Journal Title in Italics ( Like this )

- Volume, issue number

- Year of Publication in brackets

Example: Tichenor, Veronica Jaris (1999). “Status and income as gendered resources: The case of marital power”. Journal of Marriage and Family . Pg 938-65 ]

Insider’s Info: You do not number or bullet your bibliography. They should be arranged alphabetically based on the surname of the author.

Learn: Citation with Examples

Also Check: How to Write Dissertation

https://www.uh.edu/~lsong5/documents/

https://www.yorksj.ac.uk/study/postgraduate/research/

Hello! Eiti is a budding sociologist whose passion lies in reading, researching, and writing. She thrives on coffee, to-do lists, deadlines, and organization. Eiti's primary interest areas encompass food, gender, and academia.

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

School of Social Sciences

How to write a research proposal

You will need to submit a research proposal with your PhD application. This is crucial in the assessment of your application and it warrants plenty of time and energy.

Your proposal should outline your project and be around 1,500 words.

Your research proposal should include a working title for your project.

Overview of the research

In this section, you should provide a short overview of your research. You should also state how your research fits into the research priorities of your particular subject area.

Here you can refer to the research areas and priorities of a particular research grouping or supervisor.

You must also state precisely why you have chosen to apply to the discipline area and how your research links into our overall profile.

Positioning of the research

This should reference the most important texts related to the research, demonstrate your understanding of the research issues, and identify existing gaps (both theoretical and practical) that the research is intended to address.

Research design and methodology

This section should identify the information that is necessary to carry out the analysis and the possible research techniques that could deliver the information.

Ethical considerations

You should identify and address any potential ethical considerations in relation to your proposed research. Please discuss your research with your proposed supervisor to see how best to progress your ideas in line with University of Manchester ethics guidance, and ensure that your proposed supervisor is happy for you to proceed with your application.