An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Among Undergraduate Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic and their Use of Mental Health Services

Jungmin lee.

1 Department of Educational Policy Studies and Evaluation, University of Kentucky, 597 S. Upper Street, 131 Taylor Education Building, Lexington, KY 40506-0001 USA

Hyun Ju Jeong

2 Department of Integrated Strategic Communication, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY USA

3 Division of Biomedical Informatics, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY USA

Associated Data

Not applicable.

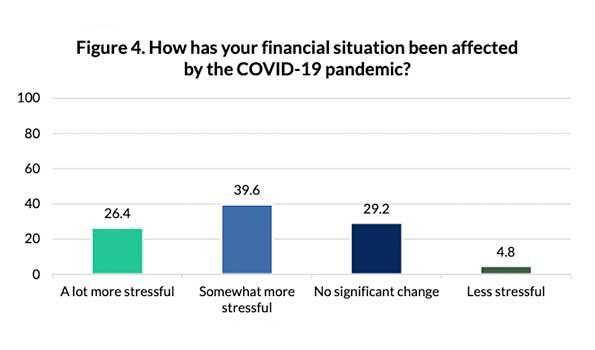

The coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) has brought significant changes to college students, but there is a lack of empirical studies regarding how the pandemic has affected student mental health among college students in the U.S. To fill the gap in the literature, this study describes stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms for students in a public research university in Kentucky during an early phase of COVID-19 and their usage of mental health services. Results show that about 88% of students experienced moderate to severe stress, with 44% of students showing moderate to severe anxiety and 36% of students having moderate to severe depression. In particular, female, rural, low-income, and academically underperforming students were more vulnerable to these mental health issues. However, a majority of students with moderate or severe mental health symptoms never used mental health services. Our results call for proactively reaching out to students, identifying students at risk of mental health issues, and providing accessible care.

The coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) has brought significant and sudden changes to college students. To protect and prevent students, faculty, and staff members from the disease, higher education institutions closed their campus in the spring of 2020 and made a quick transition to online classes. Students were asked to evacuate on a short notice, adjust to new online learning environments, and lose their paid jobs in the middle of the semester. The pandemic has also raised concerns among college students about the health of their family and friends (Brown & Kafka, 2020 ). Because all these changes were unprecedented and intensive, they caused psychological distress among students, especially during the first few months of the pandemic. There is abundant anecdotal evidence describing students’ stress and emotional difficulties as impacted by COVID-19, but there are only a few empirical studies available that directly measure college student mental health since the outbreak (e.g., Huckins et al., 2020 ; Kecojevic et al., 2020 ; Son et al., 2020 ). Most existing studies focus on mental health for general populations (e.g., Gao et al., 2020 ) or health care workers (e.g., Chen et al., 2020 ), whose results may not be applicable to college students. Given that college students are particularly vulnerable to mental health issues (e.g., Kitzrow, 2003 ), it is important to explore their mental health during this unprecedented crisis.

In this study, we describe the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression for undergraduate students in a public research university during the six weeks after the COVID-19 outbreak alongside their usage of mental health services. Using a self-administered online survey, we measured stress, anxiety, and depression levels with well-established clinical tools and asked the extent to which college students used on-campus and off-campus mental health services for the academic year. Our results revealed that more than eight out of ten students surveyed experienced modest or severe stress, and approximately 36–44% of respondents showed moderate or severe anxiety and depression. However, more than 60% of students with moderate or severe stress, anxiety, or depression had never utilized mental health services on- or off-campus. Although focusing on a single institution, this paper is one of the few studies that empirically examine mental health of college students in the U.S. during the early phase of the pandemic. Findings from this paper reassure the seriousness of student mental health during the pandemic and call for a proactive mental health assessment and increased support for college students.

Literature Review

Covid-19 and student mental health.

Empirical studies reported a high prevalence of college mental health issues during the early phase of COVID-19 around the world (Cao et al., 2020 ; Chang et al., 2020 ; Liu et al., 2020 , Rajkumar, 2020 ; Saddik et al., 2020 ). In the U.S. a few, but a growing number of empirical surveys and studies were conducted to assess college students’ mental health during the pandemic. Three nationwide surveys conducted across the U.S. conclude that college student mental health became worse during the pandemic. According to an online survey administered by Active Minds in mid-April of 2020, 80% of college students across the country reported that COVID-19 negatively affected their mental health, with 20% reporting that their mental health had significantly worsened (Horn, 2020 ). It is also concerning that 56% of students did not know where to go if they had immediate needs for professional mental health services (Horn, 2020 ). Another nationwide survey conducted from late-May to early-June also revealed that 85% of college students felt increased anxiety and stress during the pandemic, but only 21% of respondents sought a licensed counselor or a professional (Timely MD, n.d. ) According to the Healthy Minds Network’s survey (2020), which collected data from 14 college campuses across the country between March and May of 2020, the percentage of students with depression increased by 5.2% compared to the year before. However, 58.2% of respondents never tried mental health care and about 60% of students felt that it became more difficult to access to mental health care since the pandemic. These survey results clearly illustrate that an overwhelming majority of college students in the U.S. have experienced mental health problems during the early phase of COVID-19, but far fewer students utilized professional help. Despite the timely and valuable information, only Healthy Minds Network ( 2020 ) used clinical tools to measure student mental health, and none of them explored whether student characteristics were associated with mental health symptoms.

To date, only a few scholarly research studies focus on college student mental health in the U.S. since the COVID-19 outbreak. Huckins et al. ( 2020 ) have longitudinally tracked 178 undergraduate students at Dartmouth University for the 2020 winter term (from early-January to late-March of 2020) and found elevated anxiety and depression scores during mid-March when students were asked to leave the campus due to the pandemic. The evacuation decision coincided with the final week, which could have intensified student anxiety and depression. The anxiety and depression scores gradually decreased once the academic term was over, but they were still significantly higher than those measured during academic breaks in previous years. Conducting semi-structured interviews with 195 students at a large public university in Texas, Son et al. ( 2020 ) found that 71% of students surveyed reported increased stress and anxiety due to the pandemic, but only 5% of them used counseling services. The rest of the students explained that they did not use counseling services because they assumed that others would have similar levels of stress and anxiety, they did not feel comfortable talking with unfamiliar people or over the phone, or they did not trust counseling services in general. Common stressors included concerns about their own health or their loved ones’, sleep disruption, reduced social interactions, and difficulty in concentration. Based on a survey from 162 undergraduate students in New Jersey, Kecojevic et al. ( 2020 ) found that female students had a significantly higher level of stress than male students and that upper-class undergraduate students showed a higher level of anxiety than first-year students. Having difficulties in focusing on academic work led to increased levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Kecojevic et al., 2020 ).

College Student Mental Health and Usage of Mental Health Services Before COVID-19

College student mental health has long been studied in education, psychology, and medicine even before the pandemic. The general consensus of the literature is that college student mental health is in crisis, worsening in number and severity over time. Before the pandemic in the academic year of 2020, more than one-third of college students across the country were diagnosed by mental health professionals for having at least one mental health symptom (American College Health Association, 2020 ). Anxiety (27.7%) and depression (22.5%) were most frequently diagnosed. The proportion of students with mental health problems is on the rise as well. Between 2009 and 2015, the proportion of students with anxiety or depression increased by 5.9% and 3.2%, respectively (Oswalt et al., 2020 ). Similarly, between 2012 and 2020, scores for depression, general anxiety, and social anxiety have constantly increased among those who visited counseling centers on college campuses (Center for College Mental Health [CCMH], 2021 ).

Some groups are more vulnerable to mental health problems than others. For example, female and LGBTQ students tend to report a higher prevalence of mental health issues than male students (Eisenberg et al., 2007b ; Evans et al., 2018 ; Wyatt et al., 2017 ). However, there is less conclusive evidence on the difference across race or ethnicity. It is well-supported that Asian students and international students report fewer mental health problems than White students and domestic students, but there are mixed results regarding the difference between underrepresented racial minority students (i.e., African-American, Hispanic, and other races) and White students (Hyun et al., 2006 ; Hyun et al., 2007 ). Many researchers find either insignificant differences (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2007b ) or fewer mental health issues reported for underrepresented minority students compared to White students (e.g., Wyatt et al., 2017 ). This may not necessarily mean that racial minority students tend to have fewer mental health problems, but it may reflect their cultural tendency against disclosing one’s mental health issues to others (Hyun et al., 2007 ; Wyatt & Oswalt, 2013 ). In terms of age, some studies (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2007b ) reveal that students who are 25 years or older tend to have fewer mental health issues than younger students, while others find it getting worse throughout college (Wyatt et al., 2017 ). Lastly, financial stress significantly increases depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts among college students (Eisenberg et al., 2007b ).

Despite the high prevalence of mental health issues, college students tend to underutilize mental health services (Cage et al., 2018 ; Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010 ; Lipson et al., 2019 ; Oswalt et al., 2020 ). The Healthy Minds Study 2018–2019, which collected data from 62,171 college students across the country, reports that 57% of students with positive anxiety or depression screens have not used counseling or therapy, and 64% of them have not taken any psychotropic medications within the past 12 months (Healthy Minds, 2019 ). Even when students had visited a counseling center, about one-fourth of them did not return for a scheduled appointment, and another 14.1% of students declined further services (CCMH, 2021 ). When asked the barriers that prevented them from seeking mental health services, students reported a lack of perceived needs for help (41%), preference to deal with mental health issues on their own or with families and friends (27%), a lack of time (23%), financial difficulty (15%), and a lack of information about where to go (10%). Students who never used mental health services were not sure if their insurance covered mental health treatment or were more skeptical about the effectiveness of treatment (Eisenberg et al., 2007a ). Stigma, students’ view about getting psychological help for themselves, is another significant barrier in seeking help and utilizing mental health services (Cage et al., 2018 ).

Current Study

While previous studies have advanced our understanding of student mental health and their usage of mental health services, we find a lack of empirical studies on these matters, particularly in the context of COVID-19. The goal of this study is to fill the gap with specific investigations into the prevalence and pattern of U.S. college student mental health with regard to counseling service use during the early phase of COVID-19. First, very few studies focus on college students and their mental health during the pandemic, and most nationwide surveys conducted in the U.S. did not use clinically validated tools to measure student mental health. In this study, we have employed the three clinical measures to assess stress, anxiety, and depression, which are the most prevalent mental health problems among college student populations (Leviness et al., 2017 ). Secondly, it should be noted that while empirical research conducted in U.S. institutions clearly demonstrate that college students were under serious mental distress during the pandemic (Huckins et al., 2020 ; Son et al., 2020 ; Kecojevic et al., 2020 ), such studies have relatively small sample sizes and rarely examined whether particular groups were more vulnerable than others during the pandemic. To overcome such limitations, the present study has recruited a relatively large number of students from all degree-seeking students enrolled at the study institution. Further, given the high prevalence of mental health issues, we have identified vulnerable student groups and provided suggestions regarding necessary support for these students in an effort to reduce mental health disparity. Lastly, previous studies (e.g., Healthy Minds, 2019 ) show that college students, even those with mental health issues, tended to underutilize counseling services before the pandemic. Yet, there is limited evidence regarding whether this continued to be the case during COVID-19. Our study provides empirical evidence regarding the utilization of mental health services during the early phase of the pandemic and identifies its predictors. Based on the preceding discussions, we address the following research questions in this study:

First, how prevalent were stress, anxiety, and depression among college students during the early phase of the pandemic? Second, to what extent have students utilized mental health services on- and off-campus? Third, what are the predictors of mental health symptoms and the usage of mental health services?

We collected data via a self-administered online survey. This survey was designed to measure student mental health, the usage of mental health services, and demographics. The survey was sent to all degree-seeking students enrolled in a public research university in Kentucky for the spring of 2020. An invitation email was first sent on March 23, which was two days after the university announced campus closure, and two more reminder emails were sent in mid-April and late-April. The survey was available until May 8th, which was the last day of the semester.

A total of 2691 students (out of 24,146 qualified undergraduate and graduate degree-seeking students enrolled for the semester) responded to the survey. The response rate was 11.14%, but this is acceptable as it is within the range of Internet survey response rates, which is anywhere from 1 to 30% (Wimmer & Dominick, 2006 ). We deleted responses from 632 students who did not answer any mental health questions, which left 2059 valid students for the analysis. In this study, we focused on undergraduate students because they are significantly different from graduate students in terms of demographics (e.g., racial composition, age, and income) and major stressors (Wyatt & Oswalt, 2013 ). As a result, 1412 undergraduate students are included in our sample. 90% of these students had complete data. The rest of students skipped a couple of questions (usually related to their residency) but answered most of the question. Thus, we conducted multiple imputation, created ten imputed data sets, and ran regression models using these imputed data (Allison, 2002 ). Our regression results using imputed data are qualitatively similar to the estimates using original data; however, for comparison, we also provided the regression estimates using original data in Appendix Tables 6 and and7. 7 . Please note that we still used original data for descriptive research questions (presented in Tables 1 , ,2, 2 , and and4) 4 ) to accurately describe the prevalence of mental health symptoms and use of counseling services.

Descriptive statistics of sample characteristics

Descriptive statistics for stress, anxiety, and depression prevalence

Usage of mental health services among students with moderate or severe symptoms

Ordinal logistic regression models for severity of mental health symptoms (original data)

Odds ratio are reported, and numbers in parentheses are standard error

+ p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Logistic regression models predicting the usage of mental health services (original data)

+ p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

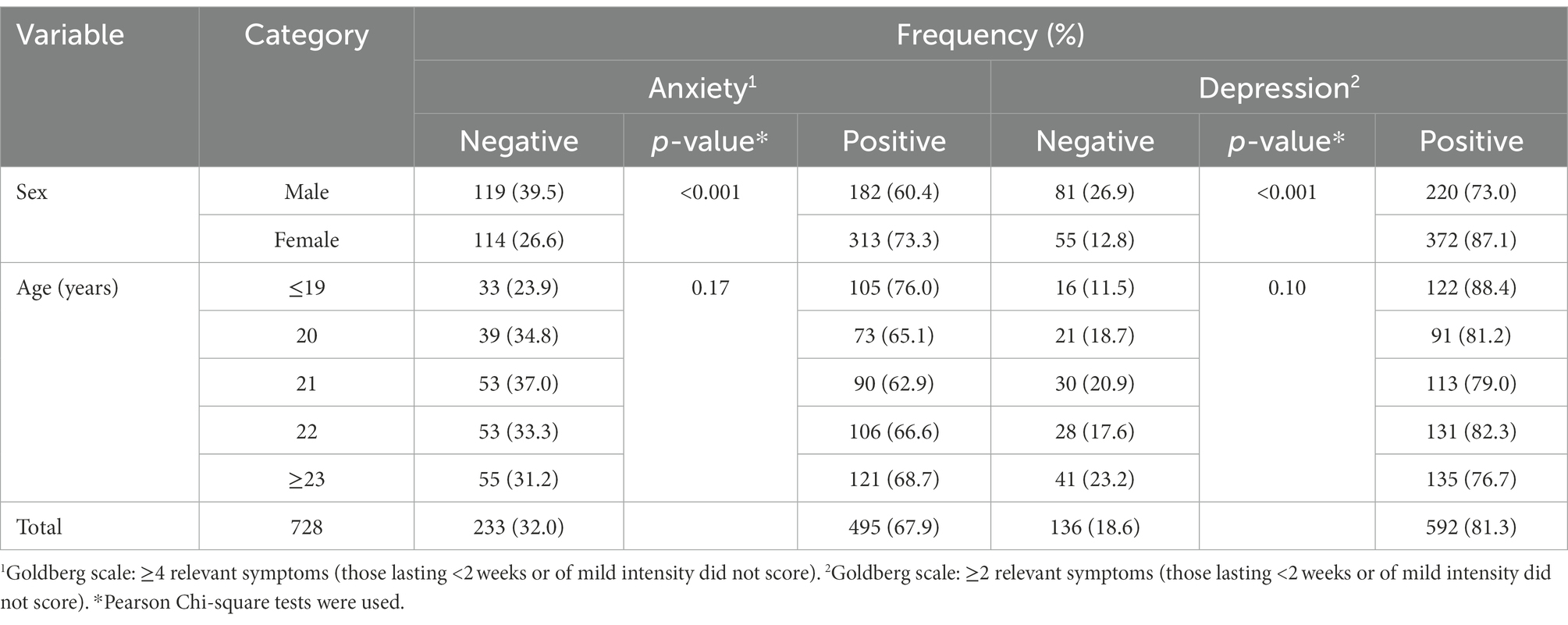

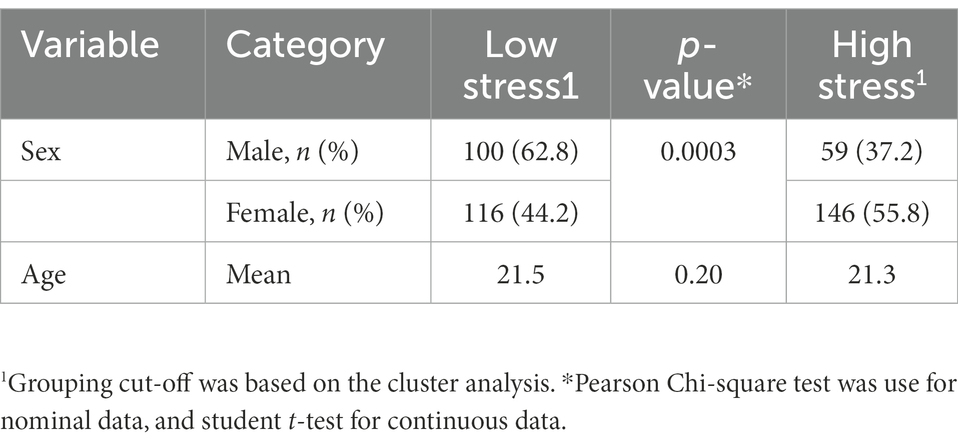

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for students in our data. Female (73%), White (86%), and students who are below 25 years old (95%) are the vast majority of our sample. About one in four students are rural students and/or students from Appalachian areas (27%) and first-generation students (23%). Wealthier students (whose family income was $100,000 or more) make up about 44% of the sample (44%). Compared to the undergraduate student population at the study site, female students (56.3% at the study site) are overrepresented in our study. The proportion of White students is slightly higher in our sample (86%) than the study population (84%), and that of first-generation students is slightly lower in our sample (23%) than that in the study population (26%).

There are five key outcome variables for this study. The first three outcome variables are stress, anxiety, and depression, and the other two variables are the extent to which students used on-campus and off-campus mental health services for the academic year, respectively. Our mental health measures are well-established and widely used in a clinical setting. For stress, we used the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) that includes ten items asking students’ feelings and perceived stress measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) (Cohen et al., 1983 ). Using the sum of scores from the ten items, the cut-off score for low, moderate, and high stress is 13, 26, and 40, respectively. PSS scale was used in hundreds of studies and validated in many languages (Samaha & Hawi, 2016 ). PSS also has a high internal consistency reliability. Of the recent studies that used the instrument to measure mental health of U.S. college students, Cronbach’s alpha was around 0.83 to 0.87, which exceeded the commonly used cut-off of 0.70 (Adams et al., 2016 ; Burke et al., 2016 ; Samaha & Hawi, 2016 ).

We used the General Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale to measure anxiety. This is a brief self-report scale to identify probable cases of anxiety disorders (Spitzer et al., 2006 ). The GAD scores of 5, 10, and 15 are taken as the cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. In a clinical setting, anyone with a score of 10 or above are recommended for further evaluation. GAD is moderately good at screening three other common anxiety disorders - panic disorder (sensitivity 74%, specificity 81%), social anxiety disorder (sensitivity 72%, specificity 80%), and post-traumatic stress disorder (sensitivity 66%, specificity 81%) (Spitzer et al., 2006 ) In their recent study, Johnson, et al. ( 2019 ) validated that “the GAD-7 has excellent internal consistency, and the one-factor structure in a heterogeneous clinical population was supported” (p. 1).

Lastly, depression was assessed with the eight-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression Short Form (Pilkonis et al., 2014 ). A score less than 17 is considered as none to slight depression, a score between 17 and 21 is considered as mild depression, a score between 22 and 32 is considered as moderate depression, and a score of 33 or above is considered as severe depression. PROMIS depression scale is a universal, rather than a disease-specific, measure that was developed using item response theory to promote greater precision and reduce respondent burden (Shensa et al., 2018 ). The scale has been correlated and validated with other commonly used depression instruments, including the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Lin et al., 2016 ).

When it comes to the usage of psychological and counseling services, we asked students to indicate the extent to which they used free on-campus resources (e.g., counseling center) and off-campus paid health professional services (e.g., psychiatrists) anytime during the academic year on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (very often), respectively. These questions do not specifically ask if students utilized these services after the COVID-19 outbreak, but responses for these questions indicate whether and how often students had used any of these services for the academic year until they responded to our survey.

We also collected data about student demographics and characteristics including student gender, race or ethnicity, age, class levels (freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior), first generation student status (1 = neither parent has a bachelor’s degree, 0 = at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree), family income, residency (rural and/or Appalachian students, international students), GPAs, and perceived stigma about seeking counseling or therapy (i.e., “I am afraid of what my family and friends will say or think of me if I seek counseling/therapy”) measured on a 5-point Likert scale. We used these variables to see if they were associated with a high level of stress, anxiety, and depression and the usage of mental health services.

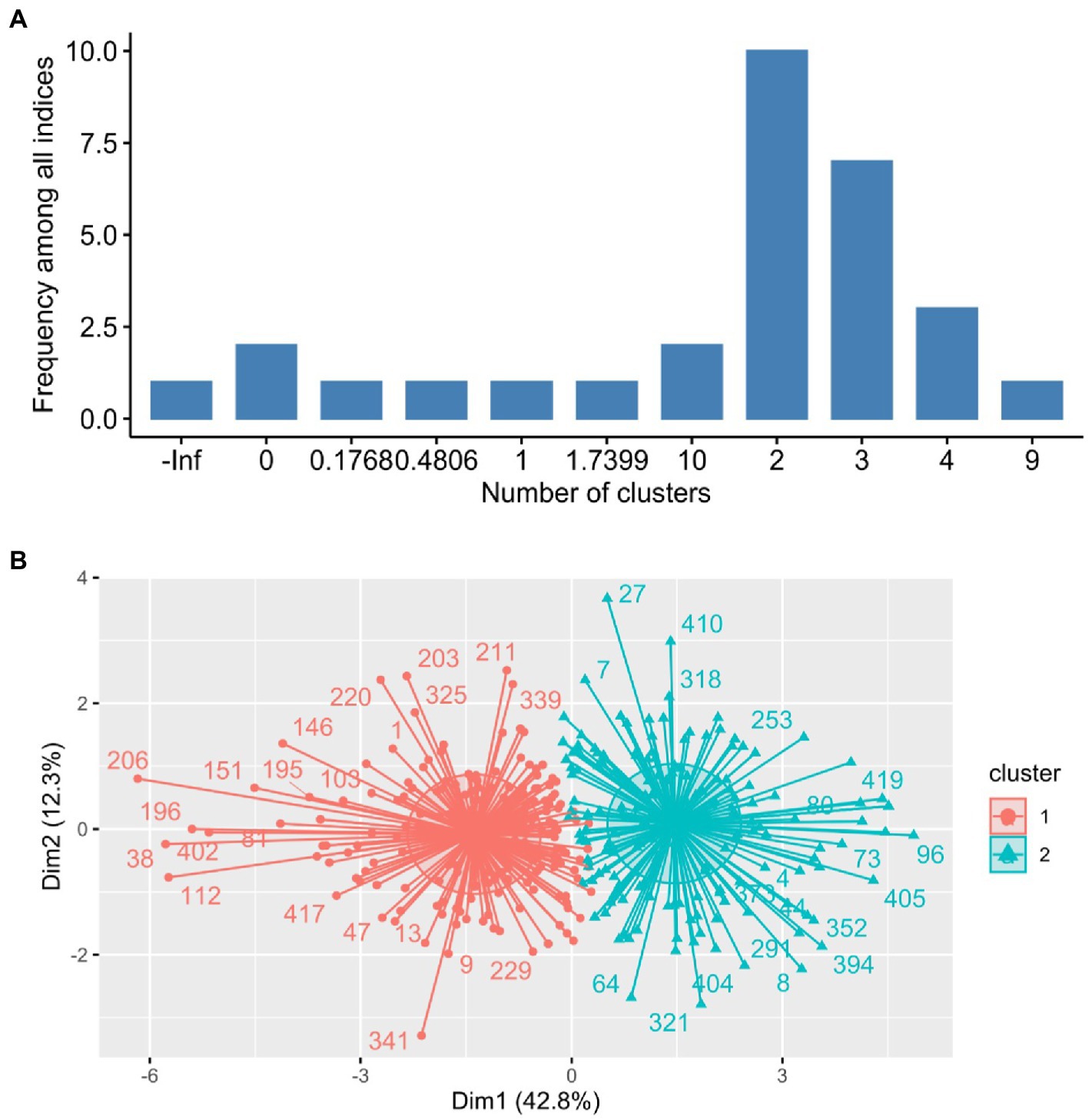

We used descriptive statistics, ordinal logistic regression, and logistic regression models in this study. To address the first and second research questions, we used descriptive statistics and presented the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression as well as the frequency of using mental health services. For the third research question, we adopted ordinal logistic regression and logistic regression models depending on outcome variables. We used ordinal logistic regression models to identify correlates of different levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, which were measured in ordinal variables (e.g., mild, moderate, and severe). For the usage of mental health service outcomes, we employed logistic regression models. Because more than two-thirds of students in the sample never utilized either type of mental health services, we re-coded the usage variables into binary variables (1 = used services, 0 = never used services) and ran logistic regression models.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, we do not claim a causal relationship in this study, but we describe the state of mental health for students soon after the COVID-19 outbreak. We acknowledge that many students may have suffered from mental health problems before the pandemic, with some experiencing escalation after the outbreak (e.g., Horn, 2020 ). Even if our study does not provide a causal relationship, we believe that it is important to measure and document student mental health during the pandemic so that practitioners can be aware of the seriousness of this issue and consider ways to better serve students. Secondly, our study results may not be applicable to students in other institutions or states. We collected data from a public research university in Kentucky where the number of confirmed cases and deaths were relatively lower than other states such as New York. The study site mainly serves traditional college students who attend college right after high school, who live on campus, and who do not have dependents. Therefore, mental health for students at other types of institutions or in other states could be different from what is presented in our study.

Prevalence of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression

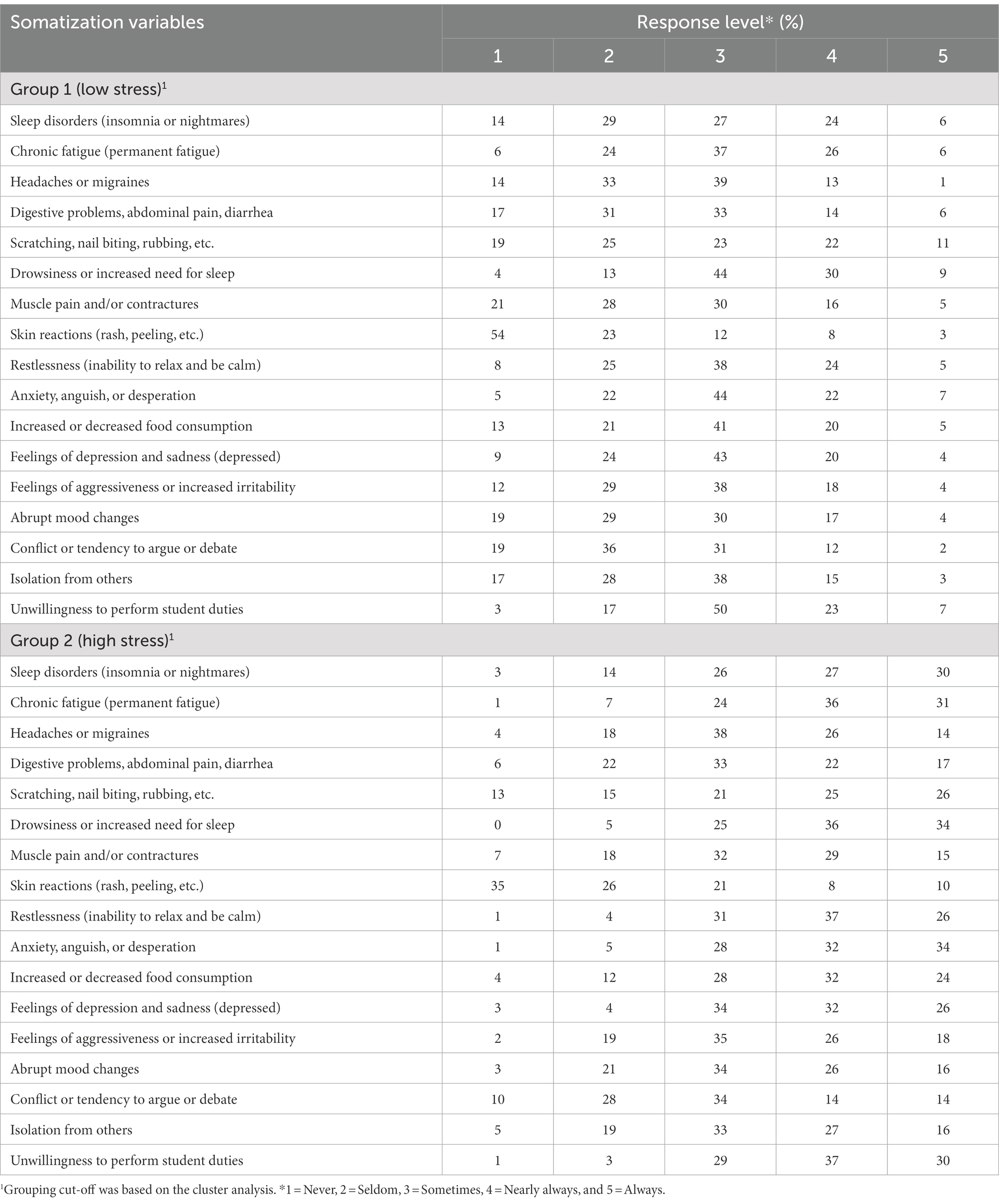

Table 2 shows the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression. Overall, a majority of students experienced psychological distress during the early phase of the pandemic. When it comes to stress, about 63% of students had a moderate level of stress, and another 24.61% of students fell into a severe stress category. Only 12% of students had a low level of stress. In other words, more than eight in ten students in the survey experienced moderate to severe stress during the pandemic. This result is comparable to the Active Minds’ survey results that report 91% of college students reported experiencing feelings of stress and anxiety since the pandemic (Horn, 2020 ).

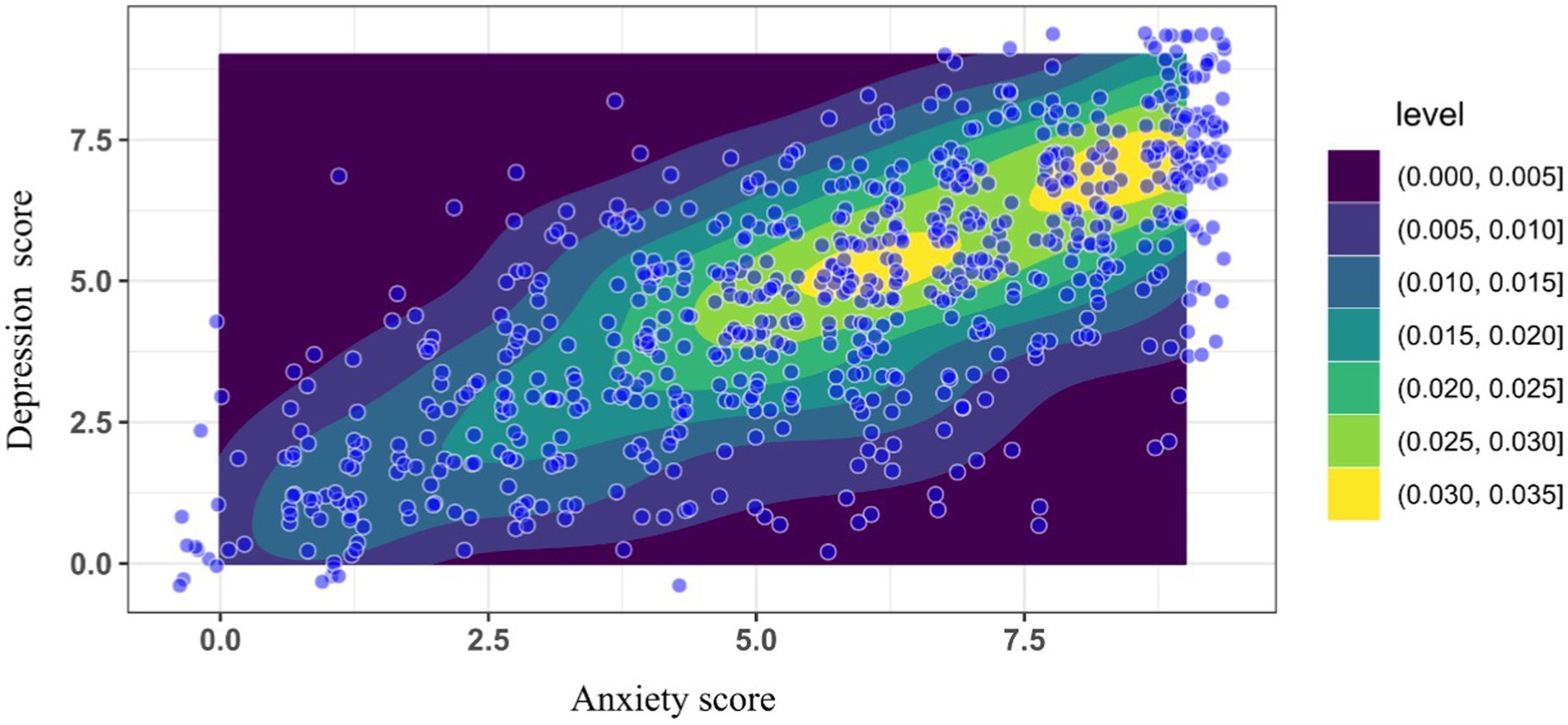

In terms of anxiety, approximately 24% and 21% of students in our study had moderate and severe anxiety disorders, respectively. Given that those who scored 10 or above on the GAD-7 scale (moderate to severe category) are recommended to meet with professionals (Spitzer et al., 2006 ), this finding implies that nearly half of students in this study needed to get professional help. This proportion of students with moderate to severe anxiety is almost double that for university students in China (e.g., Chang et al., 2020 ) or the United Arab Emirates soon after the COVID-19 outbreak (Saddik et al., 2020 ). Lastly, approximately 30% and 6% of students suffered from moderate and severe depression, respectively. These proportions are far higher than college students in China measured during the pandemic (Chang et al., 2020 ) but slightly higher than a nationwide sample of U.S. college students assessed before the pandemic (Healthy Minds, 2019 ). Given that our study measured these mental health symptoms for the first six weeks of the pandemic, we speculate that the proportion of students with moderate or severe depression would increase over time.

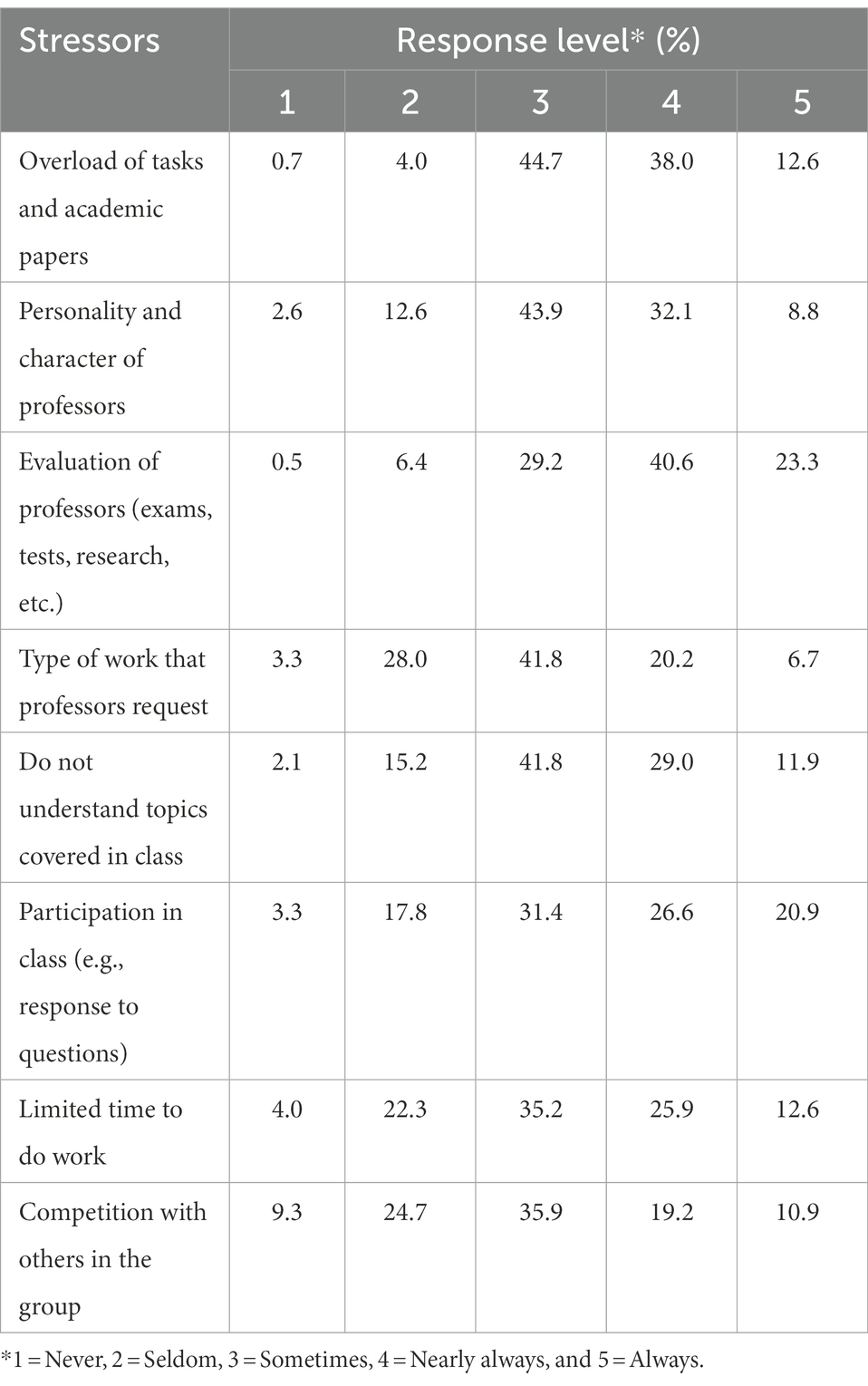

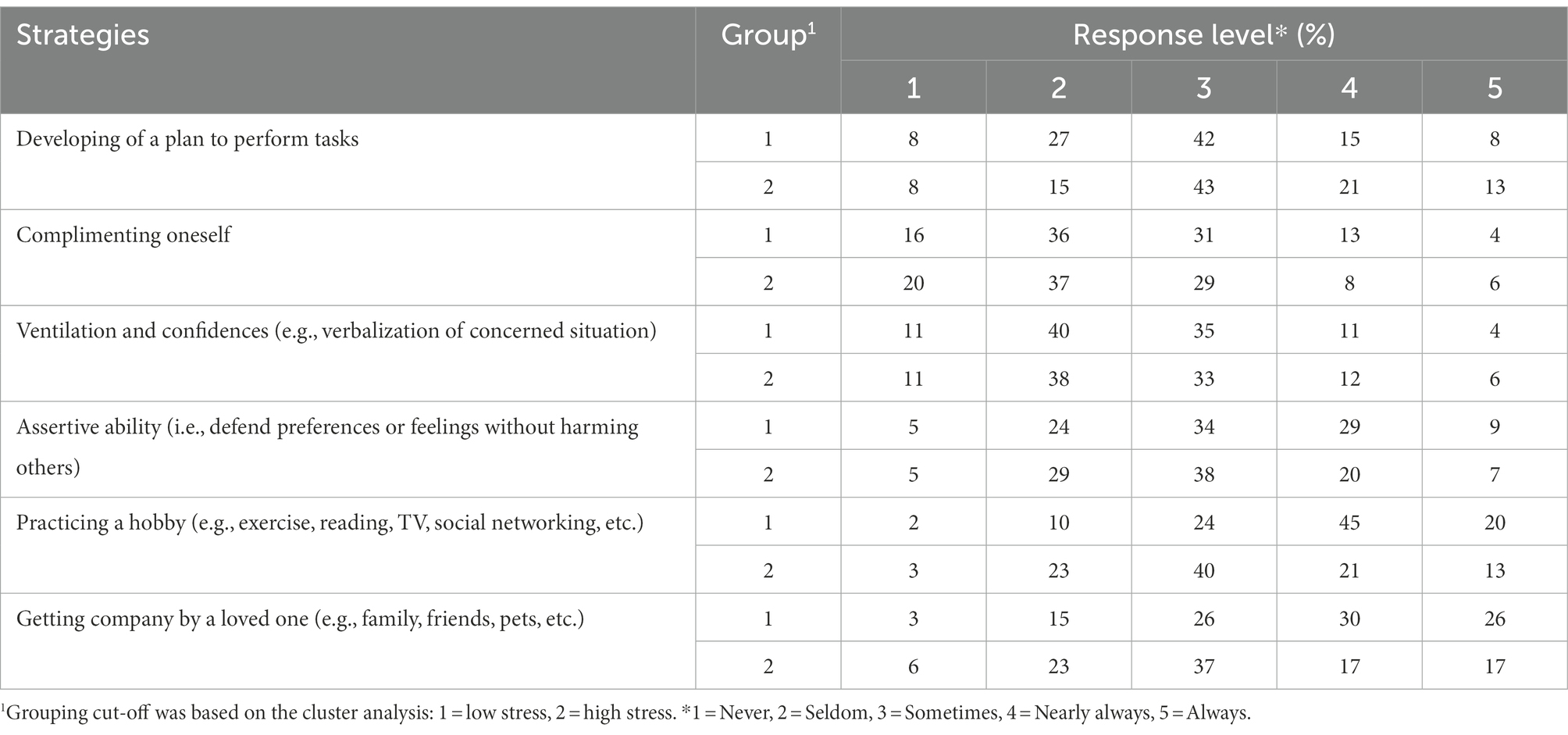

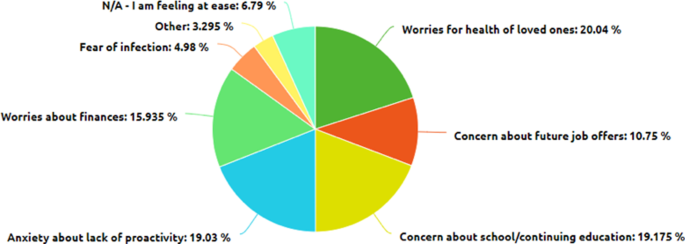

In order to explore predictors of a higher level of stress, anxiety, and depression, we ran ordinal logistic regression models as presented in Table 3 . Overall, it is clear and consistent that the odds of experiencing a higher level of stress, anxiety, and depression (e.g., severe than moderate, moderate than mild, etc.) were significantly greater for female students by a factor of 1.489, 1.723, and 1.246 than the odds for male students when other things were held constant. This gender difference in mental health symptoms is quite consistent with other studies before and during the pandemic (Eisenberg et al., 2007a ; Kecojevic et al., 2020 ). When it comes to race or ethnicity, the odds of experiencing a higher level of stress, anxiety, and depression for African-American students were almost as half as the odds for White students. However, there was no significant difference in the odds for Hispanic and Asian students compared to White students. Student class level was significantly related to stress and anxiety levels: The odds were greater for upper-class students than lower class students. This result is consistent with Kecojevic et al. ( 2020 ), which reported significantly higher levels of anxiety among upper-class students compared to freshman students. It may reflect that one of major stressors for college students during the pandemic is the uncertain future of their education and job prospects, which would be a bigger concern for upper-class students (Timely MD, n.d.).

Ordinal logistic regression models for severity of mental health symptoms (imputed data)

One’s rurality, family income, and GPA were significantly associated with the severity of mental health symptoms. The odds of experiencing a severe level of anxiety and depression were 1.325 and 1.270 times higher among rural students than urban and suburban students. With every one unit increase in family income or students’ GPAs, the odds of experiencing a more severe stress, anxiety, and depression significantly decreased. This result suggests that students from disadvantaged backgrounds were even more vulnerable to psychological distress during the early phase of the pandemic. The negative association between GPAs and mental distress levels was consistent with previous studies that showed that college students were very concerned about their academic performances and had difficulty in concentration during the early phase of the pandemic (Kecojevic et al., 2020 ; Son et al., 2020 ).

Usage of Mental Health Services

In Table 4 , we first describe the extent to which students with moderate to severe symptoms of stress, anxiety, or depression used mental health services on- and off-campus during the academic year. The university in this study has provided free counseling services for students, and the counseling services have continued to be available for students in the state via phone or Internet even after the university was closed after the outbreak. Table Table4 4 presents the frequency of students using on-campus mental health services (Panel A) and off-campus paid mental health services (Panel B) on a five-point scale. For this table, we limited the sample to students with moderate to severe symptoms of stress, anxiety, or depression to focus on students who were in need of these services. Surprisingly, a majority of these students never used mental health services on- and off-campus even when their stress, anxiety, or depression scores indicated that they needed professional help. More than 60% of students with moderate to severe symptoms never used on-campus services, and more than two-thirds of students never used off-campus mental health services. This underutilization of mental health resources is concerning but not surprising given that college students tended not to use counseling services before and during the pandemic as presented in previous studies (e.g., CCMH, 2021 ; Healthy minds, 2019 ; Son et al., 2020 ).

In order to explore predictors of the usage of mental health services, we ran logistic regression models as shown in Table 5 . We included all students in these regression models to see whether a severity of mental health symptoms was related to the usage of mental health services. Table Table5 5 presents the results for the usage of any mental health services, on-campus mental health services, and off-campus mental health services, respectively. Overall, stress, anxiety, and depression levels were positively associated with using mental health services on- and off-campus: With every one unit increase in each of these mental health symptoms, the odds of using on- and off-campus mental health services significantly increased. This result is relieving as it suggests that students who were in great need of these services actually used them. Other than mental health symptoms, there were different predictors for utilizing on-campus and off-campus services. African-American and Hispanic students were significantly more likely to use on-campus services than White students. The odds of using on-campus mental health services were 3.916 times higher for African-American students and 2.032 times higher for Hispanic students than White students. This result is interesting given that the odds of having severe mental distress were significantly lower for African-American students than White students, according to Table Table3. 3 . It may suggest that African-American students reported relatively lower levels of mental health symptoms as they had been using on-campus mental health services at higher rates. The odds of using on-campus mental health services were 2.269 times higher for international students than domestic students, but there was no significant difference in the odds of using off-campus services between the two groups. Students’ age was significantly associated with the usage of on-campus and off-campus mental health services: The odds of using on-campus services were significantly lower for older students, while the odds of utilizing off-campus services were significantly higher for older students compared to younger students. When it comes to using off-campus mental health services, the odds were significantly higher for female students, older students, and upper-class students than male students, younger students, and lower classman students. Students who were concerned with stigma associated with getting counseling and therapy were less likely to utilize off-campus mental health services.

Logistic regression models predicting the usage of mental health services (imputed data)

Discussions

Our paper describes the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression among a sample of undergraduate students in a public research university during an early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak. Using well-established clinical tools, we find that stress, anxiety, and depression were the pervasive problems for college student population during the pandemic. In particular, female, rural, low-income, and academically low-performing students were more vulnerable to psychological distress. Despite its prevalence, about two-thirds of students with moderate to severe symptoms had not utilized mental health services on- and off-campus. These key findings are very concerning considering that mental health is strongly associated with student well-being, academic outcomes, and retention (Bruffaerts et al., 2018 ; Wyatt et al., 2017 ).

Above all, we reiterate that college student mental health is in crisis during the pandemic and call for increased attention and interventions on this issue. More than eight in ten students in our study had moderate to severe stress, and more than one thirds of students experienced moderate to severe anxiety and/or depression. This is much worse than American college students before the COVID-19 (e.g., American College Health Association, 2020 ) and postsecondary students in other countries during the pandemic (e.g., Chang et al., 2020 ; Saddik et al., 2020 ). In particular, rural students, low-income students, and students with low GPAs were more vulnerable to psychological distress. These students have already faced multiple barriers in pursuing higher education (e.g., Adelman, 2006 ; Byun et al., 2012 ), and additional mental health issues would put them at a high risk of dropping out of college. Lastly, although they were dropped from the main analysis due to the small sample size ( n = 17), it is still noteworthy that a significantly higher proportion of LGBTQ students in our sample experienced severe stress, anxiety, and depression, which calls for significant attention and care for these students.

Despite the high prevalence of mental health problems, a majority of students with moderate to severe symptoms never used mental health services during the academic year, even though the university provided free counseling services. This result could be partially explained by the fact that the university’s counseling center switched to virtual counseling since the COVID-19 outbreak, which was available only for students who stayed within the state due to the license restriction across state boarders. This transition could limit access to necessary care for out-of-state students, international students, or students in remote areas where telecommunications or the internet connection is not very stable. Even worse, these students may also have limited access to off-campus health professionals due to the geographic restrictions (rural students), limited insurance coverage (international students), or a lack of financial means. Our results support that international students relied significantly more on on-campus resources than domestic students. We urge practitioners and policy makers to provide additional mental health resources that are accessible, affordable, and available for students regardless of their locations, insurance, and financial means, such as informal peer conversation groups or regular check-ins via phone calls or texts.

It is also important to point out that the overall usage of both on-campus and off-campus mental health services was generally low even before the COVID-19 outbreak. Previous studies consistently report that college students underutilize mental health services not only because of a lack of information, financial means, or available seats but also because of a paucity of perceived needs or stigma related to revealing one’s mental health issues to others (Cage et al., 2018 ; Eisenberg et al., 2007a ; Son et al., 2020 ). Our results support this finding by demonstrating that stigma one associated with getting counseling or therapy negatively influenced their utilization of off-campus mental health services. Considering these barriers, practitioners should deliver a clear message publicly that mental health problems are very common among college students and that it is natural and desirable to seek professional help if students feel stressed out, anxious, or depressed. In order to identify students with mental health needs and raise awareness among students, it can be also considered to administer a short and validated assessment in classes that enroll a large number of students (e.g., in a freshman seminar course), inform the entire class of how to interpret their scores on their own, and provide a list of available resources for those who may be interested. This would give students a chance to self-check their mental health without revealing their identities and seek help, if necessary.

We recommend that future researchers longitudinally track students and see whether the prevalence of mental health problems changes over time. Longitudinal studies are generally scarce in student mental health literature, but the timing of assessment can influence mental health symptoms reported (Huckins et al., 2020 ). The survey for our study was sent out right after the university of this study was closed due to the pandemic. It is possible that students may adjust to the outbreak over time and feel better, or that their stress may add up as the disease progresses. Tracking students over time can illustrate whether and how their mental health changes, especially depending on the way the pandemic unfolds combined with the cycle of an academic year. Secondly, there should be more studies that evaluate the effect of an intervention program on student mental health. Hunt and Eisenberg ( 2010 ) point out that little has been known about the efficacy of intervention programs while almost every higher education institution offers multiple mental health resources and counseling programs. During this pandemic, it can be a unique opportunity to implement virtual mental health interventions and evaluate their efficacy. Future research on virtual counseling and mental health interventions would guide practices to accommodate mental health needs for students who exclusively take online courses or part-time students who spend most of their time off campus. Lastly, we recommend future research investigate the extent of mental health service utilization among students with mental health needs. Existing surveys and studies on this topic usually rely on responses from those who visit a counseling center or students who respond to their surveys. Neither of these groups accurately represents those who are in need of professional help because there may be a number of students who are not aware of their mental health issues or do not want to reveal it. An effective treatment should first start with identifying those in need.

Our study highlights that college students are stressed, anxious, and depressed in the wake of COVID-19. Although college students have constantly reported mental health issues (e.g., American College Health Association, 2020 ), it is remarkable to note that the broad spectrum of COVID-19-related challenges may mitigate the overall quality of their psychological wellbeing. This is particularly the case for at-risk students (rural, international, low-income, and low-achieving students) who have already faced multiple challenges. We also present that a majority of students with mental health needs have never utilized on- and off-campus services possibly due to the limited access or potential stigma associated with mental health care. Systematic efforts with policy makers and practitioners are requested in this research to overcome the potential barriers. All these findings, based on the clinical assessment of student mental health during the early phase of the pandemic, will benefit scholars and practitioners alike. As many colleges and universities across the country have re-opened their campus for the 2020–2021 academic year, students, especially those who take in-person classes, would be concerned about the disease and continuing their study in this unprecedented time. On top of protecting students from the disease by promoting wearing masks and social distancing, it is imperative to pay attention to their mental health and make sure that they feel safe and healthy. To this end, higher education institutions should proactively reach out to all student populations, identify students at risk of mental health issues, and provide accessible and affordable care.

Biographies

is Assistant Professor of Higher Education at the University of Kentucky. She studies higher education policy, program, and practice and their effects on student success.

is an Assistant Professor of Integrated Strategic Communication at the University of Kentucky. She earned her Ph.D. in Media and Information Studies at Michigan State University. Her research interests include prosocial campaigns, consumer wellbeing, and civic engagement.

is an associate professor in the Division of Biomedical Informatics in the College of Medicine at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Kim’s current research includes: consumer health informatics, personal health information management, and health information seeking behaviors. She uses clinical natural language professing techniques and survey methodologies to better understand patients’ health knowledge and their health information uses and behaviors.

Author’s Contribution

The order of the authors in the title page reflects the share of each author’s contribution to the manuscript.

Data Availability

Code availability, declarations.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

All authors agree to publish this paper.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jungmin Lee, Email: [email protected] .

Hyun Ju Jeong, Email: [email protected] .

Sujin Kim, Email: ude.yku@miknijus .

- Adams DR, Meyers SA, Beidas RS. The relationship between financial strain, perceived stress, psychological symptoms, and academic and social integration in undergraduate students. Journal of American College Health. 2016; 64 (5):362–370. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2016.1154559. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Adelman, C. (2006). The toolbox revisited: Paths to degree completion from high school through college. U.S. Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED490195.pdf . Accessed 15 Dec 2020.

- Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data . Sage Publications .

- American College Health Association (2020). American college health association-National college health assessment III: Undergraduate student reference group executive summary spring 2020 . https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-III_Spring_2020_Undergraduate_Reference_Group_Executive_Summary.pdf . Accessed 9 Mar 2021.

- Brown, S., & Kafka, A. C. (2020). Covid-19 has worsened the student mental-health crisis. Can resilience training fix it? The Chronicle of Higher Education . https://www.chronicle.com/article/Covid-19-Has-Worsened-the/248753 . Accessed 3 Aug 2020.

- Bruffaerts R, Mortier P, Kiekens G, Auerbach RP, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Green JG, Nock MK, Kessler RC. Mental health problems in college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018; 225 (1):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.044. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burke TJ, Ruppel EK, Dinsmore DR. Moving away and reaching out: Young adults’ relational maintenance and psychosocial well-being during the transition to college. Journal of Family Communication. 2016; 16 (2):180–187. doi: 10.1080/15267431.2016.1146724. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Byun S, Meece JL, Irvin MJ. Rural-nonrural disparities in postsecondary educational attainment revisited. American Educational Research Journal. 2012; 49 (3):412–437. doi: 10.3102/0002831211416344. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cage E, Stock M, Sharpington A, Pitman E, Batchelor R. Barriers to accessing support for mental health issues at university. Studies in Higher Education. 2018; 45 (8):1–13. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1544237. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 287 :1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Center for Collegiate Mental Health. (2021). 2020 Annual Report. https://ccmh.memberclicks.net/assets/docs/2020%20CCMH%20Annual%20Report.pdf . Accessed 10 Mar 2021.

- Chang J, Yuan Y, Wang D. Mental health status and its influencing factors among college students during the epidemic of COVID-19. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2020; 40 (2):159–163. doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2020.02.06. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, Guo J, Fei D, Wang L, He L, Sheng C, Cai Y, Li X, Wang J, Zhang Z. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7 (4):e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24 (4), 385–396. 10.2307/2136404. [ PubMed ]

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Gollust, S. E. (2007a). Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Medical Care, 45 (7), 594–601. www.jstor.org/stable/40221479 . Accessed 19 June 2020. [ PubMed ]

- Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, Golberstein E, Hefner JL. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007; 77 (4):534–542. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.534. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Evans TM, Bira L, Gastelum JB, Weiss LT, Vanderford NL. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology. 2018; 36 (3):282–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4089. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, Wang I, Fu H, Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020; 15 (4):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Healthy Minds. (2019). The healthy minds study: 2018–2019 data report . https://healthymindsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/HMS_national-2018-19.pdf . Accessed 17 Aug 2020.

- Healthy Minds Network. (2020). The impact of COVID 19 on college students well-being . https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/Healthy_Minds_NCHA_COVID_Survey_Report_FINAL.pdf . Accessed 1 Mar 2021.

- Horn, A. (2020) . Active minds and association of college and university educators release guide on practical approaches for supporting student wellbeing and mental health. Active Minds . https://www.activeminds.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Active-Minds-ACUE-Release_Faculty-Guide_April-2020.pdf . Accessed 1 Mar 2021.

- Huckins JF, daSilva AW, Wang W, Hedlund E, Rogers C, Nepal SK, Wu J, Obuchi M, Murphy EI, Meyer ML, Wagner DD, Holtzheimer PE, Campbell AT. Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020; 22 (6):1–13. doi: 10.2196/20185. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hunt J, Eisenberg D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010; 46 (1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hyun JK, Quinn BC, Madon T, Lustig S. Graduate student mental health: Needs assessment and utilization of counseling services. Journal of College Student Development. 2006; 47 (3):247–266. doi: 10.1353/csd.2006.0030. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hyun JK, Quinn BC, Madon T, Lustig S. Mental health need, awareness, and use of counseling services among international graduate students. Journal of American College Health. 2007; 56 (2):109–118. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.2.109-118. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson SU, Ulvenes PG, Øktedalen T, Hoffart A. Psychometric properties of the GAD-7 in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019; 10 :1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01713. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kecojevic A, Basch CH, Sullivan M, Davi NK. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on mental health of undergraduate students in New Jersey, cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020; 15 (9):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239696. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kitzrow, M. A. (2003). The mental health needs of today's college students: Challenges and recommendations. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice , 41 (1), 167–181. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.408.2605&rep=rep1&type=pdf . Accessed 19 June 2020.

- Leviness, P., Bershad, C., & Gorman, K. (2017). Annual survey 2017. The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors. https://www.aucccd.org/assets/documents/Governance/2017%20aucccd%20survey-public-apr26.pdf . Accessed 19 June 2020.

- Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB, Hoffman BL, Giles LM, Primack BA. Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depression and Anxiety. 2016; 33 (4):323–331. doi: 10.1002/da.22466. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lipson SK, Lattie EG, Eisenberg D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017) Psychiatric Services. 2019; 70 (1):60–63. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800332. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu S, Liu Y, Liu Y. Somatic symptoms and concern regarding COVID-19 among Chinese college and primary school students: A cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 289 :1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113070. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oswalt SB, Lederer AM, Chestnut-Steich K, Day C, Halbritter A, Ortiz D. Trends in college students’ mental health diagnoses and utilization of services, 2009–2015. Journal of American College Health. 2020; 68 (1):41–51. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1515748. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds NE, Johnston KL, Maihoefer CC, Lawrence SM. Validation of the depression item bank from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS®) in a three-month observational study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014; 56 :112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.010. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020; 52 :1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saddik B, Hussein A, Sharif-Askari FS, Kheder W, Temsah MH, Koutaich RA, Haddad ES, Al-Roub NM, Marhoon FA, Hamid Q, Halwani R. Increased levels of anxiety among medical and non-medical university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Arab Emirates. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 2020; 13 :2395–2406. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S273333. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Samaha M, Hawi NS. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016; 57 :321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.045. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shensa A, Sidani JE, Escobar-Viera CG, Chu KH, Bowman ND, Knight JM, Primack BA. Real-life closeness of social media contacts and depressive symptoms among university students. Journal of American College Health. 2018; 66 (8):747–753. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1440575. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020; 22 (9):1–14. doi: 10.2196/21279. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006; 166 (10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Timely MD. (n.d.). What really has college students stressed during COVID-19 . Timely MD. https://www.timely.md/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/TimelyMD-Student-Survey-June-2020.pdf . Accessed 15 Feb 2021.

- Wimmer, R. D., & Dominick, J. R. (2006). Mass communication research: An introduction. Wadsworth.

- Wyatt TJ, Oswalt SB. Comparing mental health issues among undergraduate and graduate students. American Journal of Health Education. 2013; 44 (2):96–107. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2013.764248. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wyatt TJ, Oswalt SB, Ochoa Y. Mental health and academic performance of first-year college students. International Journal of Higher Education. 2017; 6 (2):178–187. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v6n3p178. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Change Password

Your password must have 8 characters or more and contain 3 of the following:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

- Sign in / Register

Request Username

Can't sign in? Forgot your username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Instructor Strategies to Alleviate Stress and Anxiety among College and University STEM Students

- Jeremy L. Hsu

- Gregory R. Goldsmith

*Address correspondence to: Jeremy L. Hsu ( E-mail Address: [email protected] ).

Schmid College of Science and Technology, Chapman University, Orange, CA 92866

Search for more papers by this author

While student stress and anxiety are frequently cited as having negative effects on students’ academic performance, the role that instructors can play in mitigating these challenges is often underappreciated. We provide summaries of different evidence-based strategies, ranging from changes in instructional strategies to specific classroom interventions, that instructors may employ to address and ameliorate student stress and anxiety. While we focus on students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, the strategies we delineate may be more broadly applicable. We begin by highlighting ways in which instructors can learn about and prepare to act to alleviate stress and anxiety. We then discuss how to better connect with students and build an inclusive, equitable, and empowering classroom environment. When coupled with strategies to change student evaluation and assessment, these approaches may collectively reduce student stress and anxiety, as well as improve student performance. We then discuss the roles that instructors may play in empowering students with skills that improve their time management, studying, and approach toward learning, with an eye toward ensuring their success across all their academic endeavors. We conclude by noting areas in which further research is needed to determine best practices for alleviating student stress and anxiety.

INTRODUCTION

Several recent measures have indicated increases in mental health challenges in U.S. college students ( Eisenberg et al. , 2013 ; Beiter et al. , 2015 ; Lipson et al. , 2018 ). In particular, a nationwide survey of undergraduate students in the United States identified stress (40% of all students) and anxiety (29% of all respondents) as the two most common impediments to academic performance ( American College Health Association [ACHA], 2019 ). Stress and anxiety are complex concepts, and their denotation has been the subject of considerable debate ( Lazarus and Folkman, 1984 ). Stress can be described as an individual’s perception that a situation exceeds their ability to cope and endangers their well-being, while anxiety is described as the ambiguous feelings that arise from unresolved stress (sensu Lazarus and Folkman, 1984 ; as described in Bamber and Kraenzle Schneider, 2016 ). It is important to note that studies in educational research do not always provide formal definitions for stress and anxiety, nor do they necessarily even distinguish between the two.

While stress and anxiety may differ, it is clear that both are major challenges facing college students. In fact, more than one-third of all college students report experiencing stress that impacted their academic performance within the past academic year ( ACHA, 2019 ; Morey and Taylor, 2019 ), and students with high stress are more at risk of attrition or leaving college ( Muller et al. , 2017 ). In addition, student anxiety can also negatively influence persistence in the biology major ( England et al. , 2017 , 2019 ). The prevalence of these mental health challenges is a complex issue that requires engaging stakeholders from across an institution, and there are undoubtedly many factors that can contribute to student anxiety and stress beyond academics. Here, we focus specifically on the role that instructors can play in supporting students and mitigating their stress and anxiety, providing a review of evidence-based practices that instructors can use to lower student stress and alleviate anxiety.

Learning and preparing to act

Connecting with students

Building an empowering atmosphere in the classroom

Reducing testing anxiety

Promoting effective academic skills

In addition, we provide a summary of these strategies ( Table 1 ) and a short list of recommended literature for instructors to read to learn more about these strategies ( Box 1 ). In all these strategies, we recognize that instructors may feel unqualified or uncomfortable addressing such challenges and may be wary of exacerbating mental health concerns ( White and LaBelle, 2019 ). We emphasize that our advice here does not suggest that instructors take the role of mental health professionals; clear boundaries must be established when interacting with students regarding issues of mental health more generally. However, we hope that these evidence-based strategies can help instructors become informed and improve their ability to act proactively and respond to such challenges.

Box 1. An Annotated List of Additional Reading

Cooper and Brownell (2020) : In this book chapter, Cooper and Brownell summarize the literature on how active learning impacts anxiety in the college science classroom and provide more information on how to best employ active-learning techniques while minimizing stress.

Tanner (2013) : In this synthesis paper, Tanner provides a summary of strategies instructors can take to improve engagement and equity in the classroom. While this article was not written in the context of reducing stress and anxiety, it provides direct and useful strategies for building an inclusive classroom, and several of the strategies outlined (learn or have access to students’ names, do not judge responses, use praise with caution, etc.) may increase instructor immediacy. Promoting an empowering classroom atmosphere and increasing instructor immediacy may lower stress and anxiety.

Hodges (2018) : In this article, Hodges discusses different types of group work in the classroom, group formation, how students learn in groups, and why some groups fail. This article provides insight into how instructors can most effectively manage group work, thus lowering stress.

Regehr et al. (2013) : In this article, Regehr and coauthors provide a review and meta-analysis of interventions to lower stress in college students. While most of the interventions are broader campus-level interventions that are not realistically implemented in a classroom by an instructor, the article provides great insight into what techniques are most effective at lowering stress in college students.

LEARNING AND PREPARING TO ACT

In this first category, we describe the steps that instructors can take to familiarize themselves with the many ways that stress and anxiety can manifest in students, as well as the campus resources for helping students in crisis. Instructors, in part because of their frequent contact with students, can play a critical role as “first-line responders” in recognizing challenges, rendering support, and redirecting students to other resources ( Di Placito-De Rango, 2018 ).

Recognizing Underlying Mental Health Challenges

Academic performance and the pressure to succeed (or, conversely, the fear of failing) are known drivers of stress and anxiety in college students ( Beiter et al. , 2015 ). Both stress and anxiety have been closely associated with depression and other mental health challenges as well as physical illness in college students ( Kumaraswamy, 2013 ; Mahmoud et al. , 2012 ; Rawson et al. , 1994 ). These mental health challenges can manifest in many different forms, including depression and thoughts of, or attempts at, suicide ( Garlow et al. , 2008 ).

Although instructors cannot (and should not) serve as health professionals, instructors can learn about common mental health challenges relating to stress and anxiety. Instructors who familiarize themselves with and are aware of mental health challenges can better direct students to the proper resources and likewise will have greater insight into how to approach these conversations with students if and when they arise.

Many universities offer seminars or short trainings led by the campus health resources that are explicitly intended for instructors. While there is no replacement for seeking professional help, and some students may need more intensive mental health supports, these workshops provide instructors with basic training on how to provide support and identify students in need. Trainings can enable instructors to be more familiar with the range of potential mental health challenges students may be facing, guide instructors through how to hold conversations supporting students and referring them to mental health resources when needed, and provide a range of possible resources for instructors to be aware of. Trainings often include role-playing practice sessions to allow instructors to be more comfortable in conversations in which students approach an instructor and appear anxious, depressed, or suicidal. Trainings may also discuss the role of faculty as mandated reporters in connecting students in danger with additional resources. For those who wish to educate themselves further or whose campuses lack resources, the American College Health Association ( www.acha.org ) and the Jed Foundation ( jedfoundation.org ) are two organizations that provide accessible starting points. The more instructors become familiar with these underlying mental health challenges, the better prepared they are to appropriately respond and refer students to the proper resources when faced with a student in need.

Know and Promote Campus Resources

Instructors can familiarize themselves with various campus resources, such as where to refer students if they need mental health assistance, as well as the campus public safety office and emergency medical services. However, many universities also have an explicit protocol for contacting the office of student affairs (or equivalent) if an instructor is concerned about a student who is experiencing an emergency and/or needs more immediate mental health assistance. Having a list of phone numbers and addresses easily accessible can be helpful so that instructors can connect a student to the appropriate resources or contact such resources directly when appropriate if there is a student in need (e.g., if a student appears to be struggling, has abruptly changed their behavior, or has communicated major stressors, like a death in the family, with the instructor). Similarly, instructors should encourage students to use the resources available on campus. Common resources (albeit with different titles, depending on the institution) include counseling services, academic tutoring centers, and disability services. College students consistently report a poor understanding of what mental health resources are available to them, and instructors can play a role in increasing awareness ( Zivin et al. , 2009 ; Dobmeier et al. , 2013 ). Even if they are aware of the resources, students may be hesitant to reach out due to a perceived stigma or other barrier ( Eisenberg et al. , 2009 ; Wu et al. , 2017 ). Engaging students in conversation does not guarantee that they will seek additional help ( Mitchell et al. , 2012 ). Nevertheless, discussing these resources and encouraging students to use these support systems can ensure that more students experiencing stress, anxiety, or other mental health challenges are paired with the proper resources.

A range of other campus resources are often available to students to help alleviate stress and anxiety stemming from academic pressures. Many universities offer courses or workshops on academic skills, study strategies, and time management; different variants of these programs have been shown to promote student performance and retention and lower stress, as discussed later in the section on effective academic skills ( Macan et al. , 1990 ; Kimbark et al. , 2017 ). Some universities also offer peer tutors who can assist with either course content or academic skills. Instructors can familiarize themselves with these resources, ensure that students in their classes are aware of these resources, and refer students to these support systems when needed.

CONNECTING WITH STUDENTS

In this category, we discuss several strategies that instructors can use to promote connections with students. Establishing these connections increases instructor immediacy, the perception of relational closeness and connection between the student and the instructor ( LeFebvre and Allen, 2014 ). This can make students more comfortable in class and more willing to engage with the instructor both inside and outside class ( Cooper et al. , 2017 ). Unsurprisingly, it has been demonstrated in both non-STEM and STEM classes that student anxiety decreases as instructor immediacy increases ( Williams, 2010 ; Mazer et al. , 2014 ; Kelly et al. , 2015 ). Thus, while there are only a limited number of studies directly examining the impact of the strategies we describe here on student stress or anxiety, each strategy has been shown to promote instructor immediacy and thus may help mitigate student anxiety.

Use Student Names

One of the simplest steps that instructors can take to connect with students and increase instructor immediacy may be to learn and use their preferred names and pronouns. While learning names may be more challenging for instructors teaching large classes, there are several strategies that instructors can use to learn student names more effectively. For instance, many institutions offer photo rosters to help instructors recognize and learn student names. Similarly, an increasing number of institutions now allow students to record their name out loud, helping instructors pronounce names more easily. Cooper et al. (2017) find that using name tents—pieces of paper on which students write and display their preferred names—helped dramatically increase the perception that the instructor knew student names in a high-enrollment biology class, which led students to report positive impacts on their attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions of the course. For instance, many students felt more valued, more invested in the course, and more comfortable communicating with the instructor and reaching out for help; they also stated that the use of names made them feel like the instructor cared about them and helped establish better student–instructor relationships ( Cooper et al. , 2017 ). These are all attributes that promote increased instructor immediacy and are thus associated with reduced anxiety ( Jaasma and Koper, 1999 ; Baker, 2004 ; Creasey et al. , 2009 ). Notably, the results reported by Cooper et al. (2017) are despite the fact that the instructor did not actually know the names of all students. Instructors can also ask students to write preferred pronouns on their name tents if the students are comfortable doing so; this optional use of pronouns provides an opportunity for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersexual, or asexual (LGBTQIA) students to convey their preferred pronouns for both the instructor and their classmates if they so wish, thus creating a more inclusive environment and potentially lowering their stress ( Cooper et al. , 2020 ). Students have also reported that instructors learned their names through interactions during class, immediately before and after class, during office hours, and in other conversations outside class time ( Cooper et al. , 2017 ). However, instructors should be cognizant that the use of names in some contexts may increase anxiety; students in K–12 classrooms have reported anxiety if instructors mispronounce their names ( Kohli and Solórzano, 2012 ), and the use of names for random cold-calling can also increase anxiety ( Cooper et al. , 2018a ; Waugh and Andrews, 2020 ). Beyond using name tents, we have found that arriving a few minutes before the start of class to allow for time to set up, as well as to check in and greet students, allows us to more effectively connect with students and learn their names.

Empathize with Students and Provide Opportunities for Interpersonal Connection

In addition to learning and using student names, instructors should work to empathize with students and provide opportunities for interpersonal connection; these attributes have been shown to increase the perception of students that instructors care about them ( Teven, 2001 ), which has been shown to be associated with increased instructor immediacy ( Schutt et al. , 2009 ). In addition to the informal conversations that occur in the few minutes before and after each class, sharing personal stories can also enliven the classroom and help counter student perceptions about the course, topic, and/or instructor. The use of “noncontent instructor talk” in class—defined as any instructor language that does not directly convey the course concepts—has been documented as a way to build the relationship between the instructor and student, establish classroom culture, and increase instructor immediacy ( Seidel et al. , 2015 ). Our own experiences suggest that noncontent instructor talk outside class (e.g., during office hours or individual meetings with students) may also provide the same benefits. By sharing certain personal experiences, we enable interpersonal connection and may promote a growth mindset by illustrating our own growth when we were students (as discussed later). For instance, when faced with students who struggle on a quiz or exam, we often bring up an example of an undergraduate exam gone wrong from our own experiences as students. We then discuss how we changed our study habits and how we improved following that experience. Sharing these stories encourages students and likely promotes greater instructor immediacy that may lower anxiety by showing that it is possible to recover from a poor test performance.

The use of appropriate humor in class can also lessen anxiety in the classroom ( Wanzer and Frymier, 1999 ; Cooper et al. , 2018b ). While there are many categories of inappropriate humor (such as ones that marginalize or disparage groups of students) that can damage student–instructor relationships, the use of appropriate humor can be used to strengthen the student–instructor relationship and establish a more positive classroom climate ( Bekelja Wanzer et al. , 2006; Cooper et al. , 2020 ) . In addition, the use of humor can also increase student perceptions of learning as well as their motivation and willingness to engage in class ( Wanzer and Frymier, 1999 ; Neumann et al. , 2009 ; Banas et al. , 2011 ). Embedding humor into exams and other assessments has also been shown to lead to lower stress and increased perception of exam performance by students ( Berk, 1996 , 2010 ).

BUILDING AN EMPOWERING ATMOSPHERE IN THE CLASSROOM

While connecting with students is important, it is equally critical to build a classroom atmosphere that empowers all students to feel comfortable learning, which may correlate with reduced student anxiety in the biology classroom in some contexts ( Cooper and Brownell, 2016 ). There are several strategies that instructors can take to promote such a dynamic.

Shape Active-Learning Strategies to Minimize Anxiety

The benefits of active-learning strategies have been well documented, including increased learning for students, a decrease in the achievement gap for identities historically underrepresented in the sciences, and improved attitudes and perceptions toward science ( Armbruster et al. , 2009 ; Haak et al. , 2011 ; Freeman et al. , 2014 ; Theobald et al. , 2020 ). However, recent research has indicated that many active-learning techniques can also increase student anxiety or the perceptions of student anxiety ( England et al. , 2017 ; Cooper et al. , 2018a ; Cooper and Brownell, 2020 ; Downing et al. , 2020 ) and that students employ both adaptive and maladaptive strategies to cope with this anxiety ( Brigati et al. , 2020 ). Ultimately, students with high anxiety may even learn less in an active-learning classroom ( Cohen et al. , 2019 ). Some techniques, such as cold-calling—asking a student to share a response with the class without the student volunteering—have been identified as producing particularly high anxiety in students ( England et al. , 2017 ; Cooper and Brownell, 2020 ; Waugh and Andrews, 2020 ). Even modifying common techniques, such as cold-calling, to reduce apprehension may still lead to increased student anxiety as compared with not using such techniques ( Broeckelman-Post et al. , 2016 ). In addition, different demographics of students (e.g., underrepresented students and students who speak English as a second language) may feel disproportionate amounts of stress and anxiety in an active-learning classroom ( Mak, 2011 ; Freeman et al. , 2014 ; Cooper and Brownell, 2016 ). Similarly, such active learning has the potential to disproportionately impact underrepresented students; for instance, Cooper and Brownell (2016) find that students in biology classes who are LGBTQIA report that in-class group work, particularly if they are not allowed to choose their own groups, can increase their stress and anxiety, given that they are faced with the challenge of potentially working with students who are not accepting of their identities.