The History of Homework: Why Was it Invented and Who Was Behind It?

- By Emily Summers

- February 14, 2020

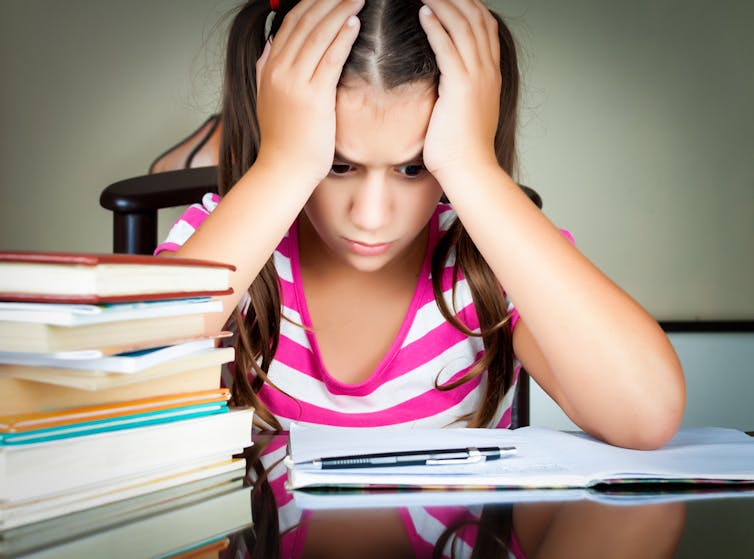

Homework is long-standing education staple, one that many students hate with a fiery passion. We can’t really blame them, especially if it’s a primary source of stress that can result in headaches, exhaustion, and lack of sleep.

It’s not uncommon for students, parents, and even some teachers to complain about bringing assignments home. Yet, for millions of children around the world, homework is still a huge part of their daily lives as students — even if it continues to be one of their biggest causes of stress and unrest.

It makes one wonder, who in their right mind would invent such a thing as homework?

Who Invented Homework?

Pliny the younger: when in ancient rome, horace mann: the father of modern homework, the history of homework in america, 1900s: anti-homework sentiment & homework bans, 1930: homework as child labor, early-to-mid 20th century: homework and the progressive era, the cold war: homework starts heating up, 1980s: homework in a nation at risk, early 21 st century, state of homework today: why is it being questioned, should students get homework pros of cons of bringing school work home.

Online, there are many articles that point to Roberto Nevilis as the first educator to give his students homework. He created it as a way to punish his lazy students and ensure that they fully learned their lessons. However, these pieces of information mostly come from obscure educational blogs or forum websites with questionable claims. No credible news source or website has ever mentioned the name Roberto Nevilis as the person who invented homework . In fact, it’s possible that Nevilis never even existed.

As we’re not entirely sure who to credit for creating the bane of students’ existence and the reasons why homework was invented, we can use a few historical trivia to help narrow down our search.

Mentions of the term “homework” date back to as early as ancient Rome. In I century AD, Pliny the Younger , an oratory teacher, supposedly invented homework by asking his followers to practice public speaking at home. It was to help them become more confident and fluent in their speeches. But some would argue that the assignment wasn’t exactly the type of written work that students have to do at home nowadays. Only introverted individuals with a fear of public speaking would find it difficult and stressful.

It’s also safe to argue that since homework is an integral part of education, it’s probable that it has existed since the dawn of learning, like a beacon of light to all those helpless and lost (or to cast darkness on those who despise it). This means that Romans, Enlightenment philosophers, and Middle Age monks all read, memorized, and sang pieces well before homework was given any definition. It’s harder to play the blame game this way unless you want to point your finger at Horace Mann.

In the 19 th century, Horace Mann , a politician and educational reformer had a strong interest in the compulsory public education system of Germany as a newly unified nation-state. Pupils attending the Volksschulen or “People’s Schools” were given mandatory assignments that they needed to complete at home during their own time. This requirement emphasized the state’s power over individuals at a time when nationalists such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte were rallying support for a unified German state. Basically, the state used homework as an element of power play.

Despite its political origins, the system of bringing school assignments home spread across Europe and eventually found their way to Horace Mann, who was in Prussia at that time. He brought the system home with him to America where homework became a daily activity in the lives of students.

Despite homework being a near-universal part of the American educational experience today, it hasn’t always been universally accepted. Take a look at its turbulent history in America.

In 1901, just a few decades after Horace Mann introduced the concept to Americans, homework was banned in the Pacific state of California . The ban affected students younger than 15 years old and stayed in effect until 1917.

Around the same time, prominent publications such as The New York Times and Ladies’ Home Journal published statements from medical professionals and parents who stated that homework was detrimental to children’s health.

In 1930, the American Child Health Association declared homework as a type of child labor . Since laws against child labor had been passed recently during that time, the proclamation painted homework as unacceptable educational practice, making everyone wonder why homework was invented in the first place.

However, it’s keen to note that one of the reasons why homework was so frowned upon was because children were needed to help out with household chores (a.k.a. a less intensive and more socially acceptable form of child labor).

During the progressive education reforms of the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries, educators started looking for ways to make homework assignments more personal and relevant to the interests of individual students. Maybe this was how immortal essay topics such as “What I Want to Be When I Grow Up” and “What I Did During My Summer Vacation” were born.

After World War II, the Cold War heated up rivalries between the U.S. and Russia. Sputnik 1’s launch in 1957 intensified the competition between Americans and Russians – including their youth.

Education authorities in the U.S. decided that implementing rigorous homework to American students of all ages was the best way to ensure that they were always one step ahead of their Russian counterparts, especially in the competitive fields of Math and Science.

In 1986, the U.S. Department of Education’s pamphlet, “What Works,” included homework as one of the effective strategies to boost the quality of education. This came three years after the National Commission on Excellence in Education published “ Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform .” The landmark report lambasted the state of America’s schools, calling for reforms to right the alarming direction that public education was headed.

Today, many educators, students, parents, and other concerned citizens have once again started questioning why homework was invented and if it’s still valuable.

Homework now is facing major backlash around the world. With more than 60% of high school and college students seeking counselling for conditions such as clinical depression and anxiety, all of which are brought about by school, it’s safe to say that American students are more stressed out than they should be.

After sitting through hours at school, they leave only to start on a mountain pile of homework. Not only does it take up a large chunk of time that they can otherwise spend on their hobbies and interests, it also stops them from getting enough sleep. This can lead to students experiencing physical health problems, a lack of balance in their lives, and alienation from their peers and society in general.

Is homework important and necessary ? Or is it doing more harm than good? Here some key advantages and disadvantages to consider.

- It encourages the discipline of practice

Using the same formula or memorizing the same information over and over can be difficult and boring, but it reinforces the practice of discipline. To master a skill, repetition is often needed. By completing homework every night, specifically with difficult subjects, the concepts become easier to understand, helping students polish their skills and achieve their life goals.

- It teaches students to manage their time

Homework goes beyond just completing tasks. It encourages children to develop their skills in time management as schedules need to be organized to ensure that all tasks can be completed within the day.

- It provides more time for students to complete their learning process

The time allotted for each subject in school is often limited to 1 hour or less per day. That’s not enough time for students to grasp the material and core concepts of each subject. By creating specific homework assignments, it becomes possible for students to make up for the deficiencies in time.

- It discourages creative endeavors

If a student spends 3-5 hours a day on homework, those are 3-5 hours that they can’t use to pursue creative passions. Students might like to read leisurely or take up new hobbies but homework takes away their time from painting, learning an instrument, or developing new skills.

- Homework is typically geared toward benchmarks

Teachers often assign homework to improve students’ test scores. Although this can result in positive outcomes such as better study habits, the fact is that when students feel tired, they won’t likely absorb as much information. Their stress levels will go up and they’ll feel the curriculum burnout.

- No evidence that homework creates improvements

Research shows that homework doesn’t improve academic performance ; it can even make it worse. Homework creates a negative attitude towards schooling and education, making students dread going to their classes. If they don’t like attending their lessons, they will be unmotivated to listen to the discussions.

With all of the struggles that students face each day due to homework, it’s puzzling to understand why it was even invented. However, whether you think it’s helpful or not, just because the concept has survived for centuries doesn’t mean that it has to stay within the educational system.

Not all students care about the history of homework, but they all do care about the future of their educational pursuits. Maybe one day, homework will be fully removed from the curriculum of schools all over the world but until that day comes, students will have to burn the midnight oil to pass their requirements on time and hopefully achieve their own versions of success.

About the Author

Emily summers.

Your Guide to Surviving College by Avoiding These Bad Habits

Balancing Acts: Managing Career Demands While Caring for an Elderly Parent

What Do the Crane Operation Signals Mean?

Why You Should Learn a New Language

Debunking the Myth of Roberto Nevilis: Who Really Invented Homework?

Is the D Important in Pharmacy? Why Pharm.D or RPh Degrees Shouldn’t Matter

How to Email a Professor: Guide on How to Start and End an Email Conversation

Everything You Need to Know About Getting a Post-Secondary Education

Grammar Corner: What’s The Difference Between Analysis vs Analyses?

The Surprising History of Homework Reform

Really, kids, there was a time when lots of grownups thought homework was bad for you.

Homework causes a lot of fights. Between parents and kids, sure. But also, as education scholar Brian Gill and historian Steven Schlossman write, among U.S. educators. For more than a century, they’ve been debating how, and whether, kids should do schoolwork at home .

At the dawn of the twentieth century, homework meant memorizing lists of facts which could then be recited to the teacher the next day. The rising progressive education movement despised that approach. These educators advocated classrooms free from recitation. Instead, they wanted students to learn by doing. To most, homework had no place in this sort of system.

Through the middle of the century, Gill and Schlossman write, this seemed like common sense to most progressives. And they got their way in many schools—at least at the elementary level. Many districts abolished homework for K–6 classes, and almost all of them eliminated it for students below fourth grade.

By the 1950s, many educators roundly condemned drills, like practicing spelling words and arithmetic problems. In 1963, Helen Heffernan, chief of California’s Bureau of Elementary Education, definitively stated that “No teacher aware of recent theories could advocate such meaningless homework assignments as pages of repetitive computation in arithmetic. Such an assignment not only kills time but kills the child’s creative urge to intellectual activity.”

But, the authors note, not all reformers wanted to eliminate homework entirely. Some educators reconfigured the concept, suggesting supplemental reading or having students do projects based in their own interests. One teacher proposed “homework” consisting of after-school “field trips to the woods, factories, museums, libraries, art galleries.” In 1937, Carleton Washburne, an influential educator who was the superintendent of the Winnetka, Illinois, schools, proposed a homework regimen of “cooking and sewing…meal planning…budgeting, home repairs, interior decorating, and family relationships.”

Another reformer explained that “at first homework had as its purpose one thing—to prepare the next day’s lessons. Its purpose now is to prepare the children for fuller living through a new type of creative and recreational homework.”

That idea didn’t necessarily appeal to all educators. But moderation in the use of traditional homework became the norm.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

“Virtually all commentators on homework in the postwar years would have agreed with the sentiment expressed in the NEA Journal in 1952 that ‘it would be absurd to demand homework in the first grade or to denounce it as useless in the eighth grade and in high school,’” Gill and Schlossman write.

That remained more or less true until 1983, when publication of the landmark government report A Nation at Risk helped jump-start a conservative “back to basics” agenda, including an emphasis on drill-style homework. In the decades since, continuing “reforms” like high-stakes testing, the No Child Left Behind Act, and the Common Core standards have kept pressure on schools. Which is why twenty-first-century first graders get spelling words and pages of arithmetic.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

A Bodhisattva for Japanese Women

Asking Scholarly Questions with JSTOR Daily

Confucius in the European Enlightenment

Watching an Eclipse from Prison

Recent posts.

- Alfalfa: A Crop that Feeds Our Food

- But Why a Penguin?

- When All the English Had Tails

- Shakespeare and Fanfiction

- Sheet Music: the Original Problematic Pop?

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Who Invented Homework? A Big Question Answered with Facts

Crystal Bourque

Delving into the intriguing history of education, one of the most pondered questions arises: Who invented homework?

Love it or hate it, homework is part of student life.

But what’s the purpose of completing these tasks and assignments? And who would create an education system that makes students complete work outside the classroom?

This post contains everything you’ve ever wanted to know about homework. So keep reading! You’ll discover the answer to the big question: who invented homework?

Who Invented Homework?

The myth of roberto nevilis: who is he, the origins of homework, a history of homework in the united states, 5 facts about homework, types of homework.

- What’s the Purpose of Homework?

- Homework Pros

- Homework Cons

When, How, and Why was Homework Invented?

Daniel Jedzura/Shutterstock.com

To ensure we cover the basics (and more), let’s explore when, how, and why was homework invented.

As a bonus, we’ll also cover who invented homework. So get ready because the answer might surprise you!

It’s challenging to pinpoint the exact person responsible for the invention of homework.

For example, Medieval Monks would work on memorization and practice singing. Ancient philosophers would read and develop their teachings outside the classroom. While this might not sound like homework in the traditional form we know today, one could argue that these methods helped to form the basic structure and format.

So let’s turn to recorded history to try and identify who invented homework and when homework was invented.

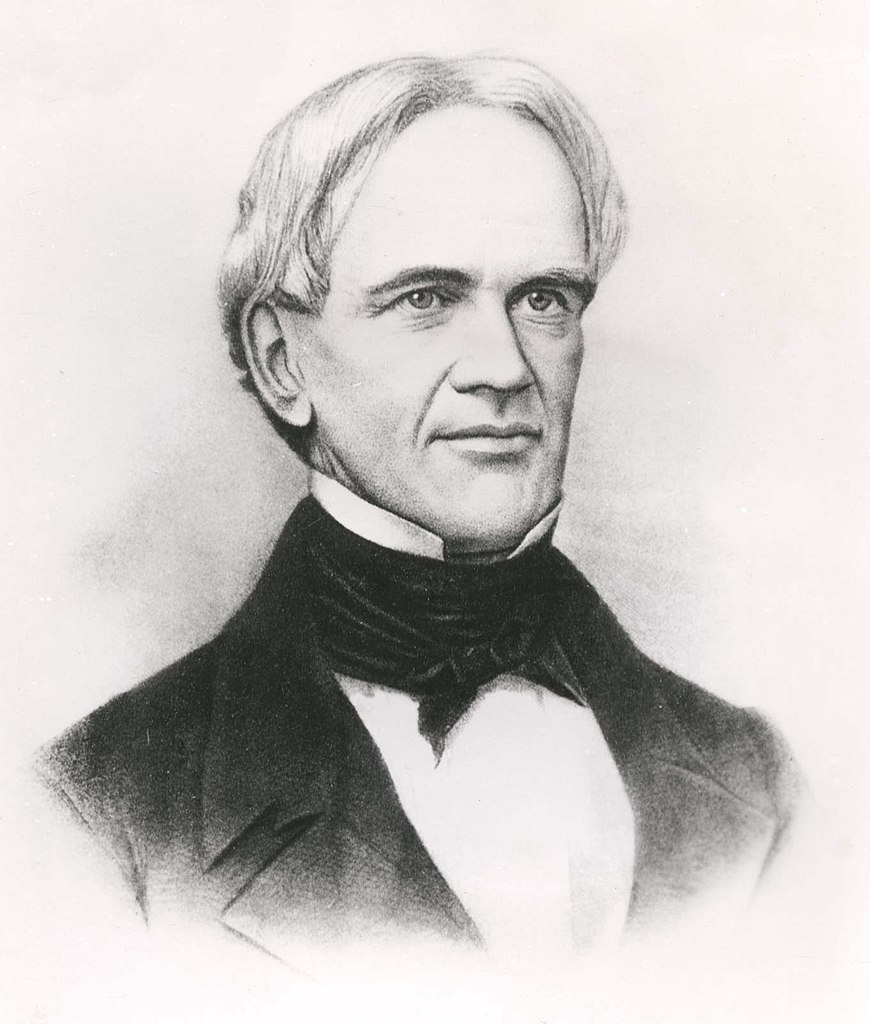

Pliny the Younger

Credit: laphamsquarterly.org

Mention of homework appears in the writings of Pliny the Younger, meaning we can trace the term ‘homework’ back to ancient Rome. Pliny the Younger (61—112 CE) was an oratory teacher, and often told his students to practice their public speaking outside class.

Pliny believed that the repetition and practice of speech would help students gain confidence in their speaking abilities.

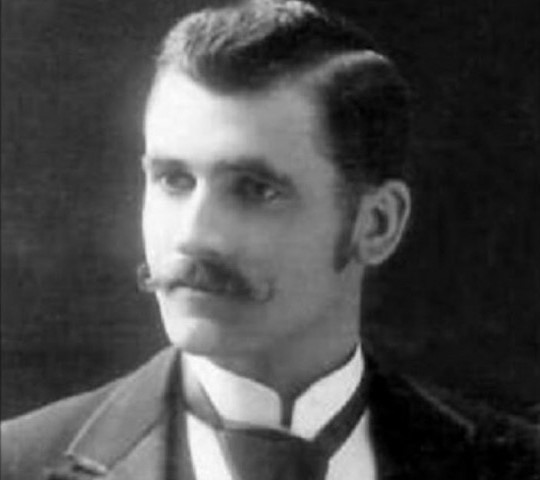

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Credit: inlibris.com

Before the idea of homework came to the United States, Germany’s newly formed nation-state had been giving students homework for years.

The roots of homework extend to ancient times, but it wasn’t until German Philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762—1814) helped to develop the Volksschulen (People’s Schools) that homework became mandatory.

Fichte believed that the state needed to hold power over individuals to create a unified Germany. A way to assert control over people meant that students attending the Volksshulen were required to complete assignments at home on their own time.

As a result, some people credit Fichte for being the inventor of homework.

Horace Mann

Credit: commons.wikimedia.org

The idea of homework spread across Europe throughout the 19th century.

So who created homework in the United States?

The history of education and homework now moves to Horace Mann (1796—1859), an American educational reformer, spent some time in Prussia. There, he learned more about Germany’s Volksshulen, forms of education , and homework practices.

Mann liked what he saw and brought this system back to America. As a result, homework rapidly became a common factor in students’ lives across the country.

Credit: medium.com

If you’ve ever felt curious about who invented homework, a quick online search might direct you to a man named Roberto Nevilis, a teacher in Venice, Italy.

As the story goes, Nevilis invented homework in 1905 (or 1095) to punish students who didn’t demonstrate a good understanding of the lessons taught during class.

This teaching technique supposedly spread to the rest of Europe before reaching North America.

Unfortunately, there’s little truth to this story. If you dig a little deeper, you’ll find that these online sources lack credible sources to back up this myth as fact.

In 1905, the Roman Empire turned its attention to the First Crusade. No one had time to spare on formalizing education, and classrooms didn’t even exist. So how could Nevilis spread the idea of homework when education remained so informal?

And when you jump to 1901, you’ll discover that the government of California passed a law banning homework for children under fifteen. Nevilis couldn’t have invented homework in 1905 if this law had already reached the United States in 1901.

Inside Creative House/Shutterstock.com

When it comes to the origins of homework, looking at the past shows us that there isn’t one person who created homework. Instead, examining the facts shows us that several people helped to bring the idea of homework into Europe and then the United States.

In addition, the idea of homework extends beyond what historians have discovered. After all, the concept of learning the necessary skills human beings need to survive has existed since the dawn of man.

More than 100 years have come and gone since Horace Mann introduced homework to the school system in the United States.

Therefore, it’s not strange to think that the concept of homework has changed, along with our people and culture.

In short, homework hasn’t always been considered acceptable. Let’s dive into the history or background of homework to learn why.

Homework is Banned! (The 1900s)

Important publications of the time, including the Ladies’ Home Journal and The New York Times, published articles on the negative impacts homework had on American children’s health and well-being.

As a result, California banned homework for children under fifteen in 1901. This law, however, changed again about a decade later (1917).

Children Needed at Home (The 1930s)

Formed in 1923, The American Child Health Association (ACHA) aimed to decrease the infant mortality rate and better support the health and development of the American child.

By the 1930s, ACHA deemed homework a form of child labor. Since the government recently passed laws against child labor , it became difficult to justify homework assignments. College students, however, could still receive homework tasks as part of their formal schooling.

Studio Romantic/Shutterstock.com

A Shift in Ideas (The 1940s—1950s)

During the early to mid-1900s, the United States entered the Progressive Era. As a result, the country reformed its public education system to help improve students’ learning.

Homework became a part of everyday life again. However, this time, the reformed curriculum required teachers to make the assignments more personal.

As a result, American students would write essays on summer vacations and winter breaks, participate in ‘show and tell,’ and more.

These types of assignments still exist today!

Homework Today (The 2000s)

The focus of American education shifted again when the US Department of Education was founded in 1979, aiming to uplevel education in the country by, among other things, prohibiting discrimination ensuring equal access, and highlighting important educational issues.

In 2022, the controversial nature of homework in public schools and formal education is once again a hot topic of discussion in many classrooms.

According to one study , more than 60% of college and high school students deal with mental health issues like depression and anxiety due to homework. In addition, the large number of assignments given to students takes away the time students spend on other interests and hobbies. Homework also negatively impacts sleep.

As a result, some schools have implemented a ban or limit on the amount of homework assigned to students.

Test your knowledge and check out these other facts about homework:

- Horace Mann is also known as the ‘father’ of the modern school system and the educational process that we know today (read more about Who Invented School ).

- With a bit of practice, homework can improve oratory and writing skills. Both are important in a student’s life at all stages.

- Homework can replace studying. Completing regular assignments reduces the time needed to prepare for tests.

- Homework is here to stay. It doesn’t look like teachers will stop assigning homework any time soon. However, the type and quantity of homework given seem to be shifting to accommodate the modern student’s needs.

- The optimal length of time students should spend on homework is one to two hours. Students who spent one to two hours on homework per day scored higher test results.

- So, while completing assignments outside of school hours may be beneficial, spending, for example, a day on homework is not ideal.

Explore how the Findmykids app can complement your child’s school routine. With features designed to ensure their safety and provide peace of mind, it’s a valuable tool for parents looking to stay connected with their children throughout the day. Download now and stay informed about your child’s whereabouts during their academic journey.

Ground Picture/Shutterstock.com

The U.S. Department of Education provides teachers with plenty of information and resources to help students with homework.

In general, teachers give students homework that requires them to employ four strategies. The four types of homework types include:

- Practice: To help students master a specific skill, teachers will assign homework that requires them to repeat the particular skill. For example, students must solve a series of math problems.

- Preparation: This type of homework introduces students to the material they will learn in the future. An example of preparatory homework is assigning students a chapter to read before discussing the contents in class the next day.

- Extension: When a teacher wants to get students to apply what they’ve learned but create a challenge, this type of homework is assigned. It helps to boost problem-solving skills. For example, using a textbook to find the answer to a question gets students to problem-solve differently.

- Integration: To solidify the student learning experience , teachers will create a task that requires the use of many different skills. An example of integration is a book report. Completing integration homework assignments helps students learn how to be organized, plan, strategize, and solve problems on their own. Encouraging effective study habits is a key idea behind homework, too.

Ultimately, the type of homework students receive should have a purpose, be focused and clear, and challenge students to problem solve while integrating lessons learned.

What’s the Purpose of Homework?

LightField Studios/Shutterstock.com

Homework aims to ensure individual students understand the information they learn in class. It also helps teachers to assess a student’s progress and identify strengths and weaknesses.

For example, school teachers use different types of homework like book reports, essays, math problems, and more to help students demonstrate their understanding of the lessons learned.

Does Homework Improve the Quality of Education?

Homework is a controversial topic today. Educators, parents, and even students often question whether homework is beneficial in improving the quality of education.

Let’s explore the pros and cons of homework to try and determine whether homework improves the quality of education in schools.

Homework Pros:

- Time Management Skills : Assigning homework with a due date helps students to develop a schedule to ensure they complete tasks on time. Personal responsibility amongst students is thereby promoted.

- More Time to Learn : Students encounter plenty of distractions at school. It’s also challenging for students to grasp the material in an hour or less. Assigning homework provides the student with the opportunity to understand the material.

- Improves Research Skills : Some homework assignments require students to seek out information. Through homework, students learn where to seek out good, reliable sources.

Homework Cons:

- Reduced Physical Activity : Homework requires students to sit at a desk for long periods. Lack of movement decreases the amount of physical activity, often because teachers assign students so much homework that they don’t have time for anything else. Time for students can get almost totally taken up with out-of-school assignments.

- Stuck on an Assignment: A student often gets stuck on an assignment. Whether they can’t find information or the correct solution, students often don’t have help from parents and require further support from a teacher. For underperforming students, especially, this can have a negative impact on their confidence and overall educational experience.

- Increases Stress : One of the results of getting stuck on an assignment is that it increases stress and anxiety. Too much homework hurts a child’s mental health, preventing them from learning and understanding the material.

Some research shows that homework doesn’t provide educational benefits or improve performance, and can lead to a decline in physical activities. These studies counter that the potential effectiveness of homework is undermined by its negative impact on students.

However, research also shows that homework benefits students—provided teachers don’t give them too much. Here’s a video from Duke Today that highlights a study on the very topic.

Homework Today

The question of “Who Invented Homework?” delves into the historical evolution of academic practices, shedding light on its significance in fostering responsibility among students and contributing to academic progress. While supported by education experts, homework’s role as a pivotal aspect of academic life remains a subject of debate, often criticized as a significant source of stress. Nonetheless, when balanced with extracurricular activities and integrated seamlessly into the learning process, homework continues to shape and refine students’ educational journeys.

Maybe one day, students won’t need to submit assignments or complete tasks at home. But until then, many students understand the benefits of completing homework as it helps them further their education and achieve future career goals.

Before you go, here’s one more question: how do you feel about homework? Do you think teachers assign too little or too much? Get involved and start a discussion in the comments!

Elena Kharichkina/Shutterstock.com

Who invented homework and why?

The creation of homework can be traced back to the Ancient Roman Pliny the Younger, a teacher of oratory—he is generally credited as being the father of homework! Pliny the Younger asked his students to practice outside of class to help them build confidence in their speaking skills.

Who invented homework as a punishment?

There’s a myth that the Italian educator Roberto Nevilis first used homework as a means of punishing his students in the early 20th century—although this has now been widely discredited, and the story of the Italian teacher is regarded as a myth.

Why did homework stop being a punishment?

There are several reasons that homework ceased being a form of punishment. For example, the introduction of child labor laws in the early twentieth century meant that the California education department banned giving homework to children under the age of fifteen for a time. Further, throughout the 1940s and 1950s, there was a growing emphasis on enhancing students’ learning, making homework assignments more personal, and nurturing growth, rather than being used as a form of punishment.

The picture on the front page: Evgeny Atamanenko/Shutterstock.com

Imagine that you have gotten yourself into a difficult situation or unfamiliar or dangerous circumstances….

Lockdown left our children with no other option other than remote education. Now that schools…

An aggressive child is not uncommon in the modern world. Unfortunately, for many parents this…

Subscribe now!

Glad you've joined us🎉🎉.

Origin and Death of Homework Inventor: Roberto Nevilis

Roberto Nevilis is known for creating homework to help students learn on their own. He was a teacher who introduced the idea of giving assignments to be done outside of class. Even though there’s some debate about his exact role, Nevilis has left a lasting impact on education, shaping the way students around the world approach their studies.

Homework is a staple of the modern education system, but few people know the story of its origin.

The inventor of homework is widely considered to be Roberto Nevilis, an Italian educator who lived in the early 20th century.

We will briefly explore Nevilis’ life, how he came up with the concept of homework, and the circumstances surrounding his death.

Roberto Nevilis: The Man Behind Homework Roberto Nevilis was born in Venice, Italy, in 1879. He was the son of a wealthy merchant and received a private education.

He later studied at the University of Venice, where he received a degree in education. After graduation, Nevilis worked as a teacher in various schools in Venice.

Table of Contents

How Homework Was Born

The Birth of Homework According to historical records, Nevilis was frustrated with the lack of discipline in his classroom. He found that students were often too focused on playing and not enough on learning.

To solve this problem , he came up with the concept of homework. Nevilis assigned his students homework to reinforce the lessons they learned in class and encourage them to take their education more seriously.

How did homework become popular?

The Spread of Homework , The idea of homework quickly caught on, and soon other teachers in Italy followed Nevilis’ lead. From Italy, the practice of assigning homework spread to other European countries and, eventually, the rest of the world.

Today, homework is a standard part of the education system in almost every country, and millions of students worldwide spend countless hours each week working on homework assignments.

How did Roberto Nevilis Die?

Death of Roberto Nevilis The exact circumstances surrounding Nevilis’ death are unknown. Some reports suggest that he died in an accident, while others claim he was murdered.

However, the lack of concrete evidence has led to numerous theories and speculation about what happened to the inventor of homework.

Despite the mystery surrounding his death, Nevilis’ legacy lives on through his impact on education.

Facts about Roberto Nevilis

- He is credited with inventing homework to punish his students who misbehaved in class.

- Some accounts suggest he was a strict teacher who believed in disciplining his students with homework.

- There is little concrete evidence to support the claim that Nevilis was the true inventor of homework.

- Some historians believe that the concept of homework has been around for much longer than in the 1900s.

- Despite the lack of evidence, Roberto Nevilis remains a popular figure in the history of education and is often cited as the inventor of homework.

The Legacy of Homework

The legacy of homework is deeply embedded in the educational landscape, reflecting a historical evolution that spans centuries. From its ambiguous origins to the diverse purposes it serves today, homework has played a pivotal role in shaping learning experiences.

While its effectiveness and necessity have been subjects of ongoing debate, homework endures as a tool for reinforcing concepts, fostering independent study habits, and preparing students for future academic and professional challenges.

In the contemporary educational context, the legacy of homework is a complex interplay of tradition, pedagogy, and evolving perspectives on the balance between academic demands and student well-being.

The Complex History of Homework

Throughout history, the evolution of homework can be traced through a series of significant developments. In ancient civilizations, such as Greece and Rome, scholars and philosophers encouraged independent study outside formal learning settings.

The Renaissance era witnessed a surge in written assignments, marking an early precursor to modern homework. The Industrial Revolution further transformed educational practices, as the need for a skilled workforce emphasized the importance of individual learning and practice.

The purposes and perceptions of homework have undergone substantial transformations over time. In the 19th century, homework was often viewed as a means of reinforcing discipline and moral values, with assignments focused on character development.

As educational philosophies evolved, particularly in the 20th century, homework assumed various roles—from a tool for drill and practice to a method for fostering critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Perceptions of homework have fluctuated, with debates arising around issues of workload, equity, and its impact on student well-being. The complex history of homework reveals a dynamic interplay between societal expectations, educational philosophies, and changing perspectives on the purposes of academic assignments.

Conclusion – Who invented homework, and how did he die

Roberto Nevilis was a visionary educator who profoundly impacted the education system. His invention of homework has changed how students learn and has helped countless students worldwide improve their education.

Although the circumstances surrounding his death are unclear, Nevilis’ legacy as the inventor of homework will never be forgotten.

What is Roberto Nevilis’ legacy?

Roberto Nevilis’ legacy is his invention of homework, which has changed how students learn and has helped countless students worldwide improve their education.

Despite the mystery surrounding his death, Nevilis’ legacy as the inventor of homework will never be forgotten.

What was Roberto Nevilis’ background?

Roberto Nevilis was the son of a wealthy merchant and received a private education. He later studied at the University of Venice, where he received a degree in education.

After graduation, Nevilis worked as a teacher in various schools in Venice.

What was Roberto Nevilis’ impact on education?

Roberto Nevilis’ invention of homework has had a profound impact on education. By assigning homework, he helped students reinforce the lessons they learned in class and encouraged them to take their education more seriously.

This concept has spread worldwide and is now a staple of the modern education system.

Is there any evidence to support the theories about Roberto Nevilis’ death?

There is no concrete evidence to support the theories about Roberto Nevilis’ death, and the exact circumstances surrounding his death remain a mystery.

What was Roberto nevilis age?

It is believed that he died of old age. Not much information is available on his exact age at the time of death. Born: 1879 Died: 1954 (aged 75 years)

Where is Roberto Nevilis’s grave

While many have tried to find out about his Grave, little is known about where he is buried. Many people are querying the internet about his Grave. But frankly, I find it weird why people want to know this.

Share this:

The Edvocate

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- Write For Us

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Assistive Technology

- Best PreK-12 Schools in America

- Child Development

- Classroom Management

- Early Childhood

- EdTech & Innovation

- Education Leadership

- First Year Teachers

- Gifted and Talented Education

- Special Education

- Parental Involvement

- Policy & Reform

- Best Colleges and Universities

- Best College and University Programs

- HBCU’s

- Higher Education EdTech

- Higher Education

- International Education

- The Awards Process

- Finalists and Winners of The 2022 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2021 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2020 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2019 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2018 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Finalists and Winners of The 2017 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Award Seals

- GPA Calculator for College

- GPA Calculator for High School

- Cumulative GPA Calculator

- Grade Calculator

- Weighted Grade Calculator

- Final Grade Calculator

- The Tech Edvocate

- AI Powered Personal Tutor

College Minor: Everything You Need to Know

14 fascinating teacher interview questions for principals, tips for success if you have a master’s degree and can’t find a job, 14 ways young teachers can get that professional look, which teacher supplies are worth the splurge, 8 business books every teacher should read, conditional admission: everything you need to know, college majors: everything you need to know, 7 things principals can do to make a teacher observation valuable, 3 easy teacher outfits to tackle parent-teacher conferences, who invented homework.

Homework is a part of life for children, parents, and educators. But who came up with the concept of homework? What happened to make it a standard in education? Here’s a quick rundown of homework’s history in the United States .

Homework’s Origins: Myth vs. History

Who was the first person to invent homework? We may never know for sure. Its history has been shaped by a variety of persons and events. Let’s start with two of its key influencers.

The Dubious Roberto Nevelis of Venice

Homework is typically credited to Roberto Nevelis of Venice, Italy, who invented it in 1095—or 1905, depending on your sources. However, upon closer examination, he appears to be more of an internet legend than a genuine figure.

Horace Mann

Horace Mann, a 19th-century politician and educational reformer, was a pivotal figure in the development of homework. Mann, like his contemporaries Henry Barnard and Calvin Ellis Stowe, was passionate about the newly unified nation-state of Germany’s obligatory public education system.

Mandatory tasks were assigned to Volksschulen (“People’s Schools”) students to complete at home on their own time. When liberals like Johann Gottlieb Fichte were striving to organize support for a unified German state, this demand highlighted the state’s authority over the individual. While homework had been established before Fichte’s participation with the Volksschulen, his political goals can be considered a catalyst for its adoption as an educational requirement.

Horace Mann was a driving force behind creating government-run, tax-funded public education in America. During a journey to Germany in 1843, he witnessed the Volkschule system at work and brought back several of its ideals, including homework.

The American Public School System’s Homework

Homework has not always been generally embraced, despite being a near-universal element of the American educational experience. Parents and educators continue to dispute its benefits and drawbacks, as they have for more than a century.

The 1900s: Anti-homework sentiment and homework bans

A homework prohibition was enacted in the Pacific state of California in 1901, barely a few decades after the idea of homework crossed the Atlantic. The restriction, which applied to all students under the age of 15, lasted until 1917.

Around the same period, renowned magazines such as the Ladies’ Home Journal and The New York Times published remarks from parents and medical professionals portraying homework as harmful to children’s health.1930: Homework as Child Labor

A group called the American Child Health Association deemed homework a form of child labor in 1930. This statement represented a less-than-favorable view of homework as an appropriate educational method, given that laws barring child labor had recently been implemented.

Early-to-Mid 20th Century: Homework and the Progressive Era

Teachers began looking for ways to make homework more personal and meaningful to individual students throughout the second half of the 19th and 20th-century modern educational changes. Could this be the origin of the enduring essay topic, “What I Did on My Summer Vacation?”

The Cold War: Homework Heats Up

Following WWII, the Cold War heightened tensions between the United States and Russia in the 1950s. The flight of Sputnik 1 in 1957 increased Russian-American enmity, particularly among their youngsters.

The best way to ensure that American students did not fall behind their Russian counterparts, especially in the extremely competitive fields of science and mathematics, was for education officials in the United States to assign demanding homework.

The 1980s: A Nation at Risk’s Homework

What Works, a 1986 publication from the US Department of Education, listed homework as one of the most effective instructional tactics. This followed three years after the groundbreaking study

Early 21st Century: Homework Bans Return

Many educators and other concerned individuals are questioning the value of homework once again. On the subject, several publications have been published.

These include:

- The Case Against Homework: How Homework Is Hurting Our Children and What We Can Do About It by Sarah Bennett and Nancy Kalish (2006)

- The Battle Over Homework: Common Ground for Administrators, Teachers, and Parents (Third Edition) by Duke University psychologist Dr. Harris Cooper (2007)

- The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning by education professor Dr. Etta Kralovec and journalist John Buell (2000)

Homework is still a contentious topic nowadays. Some schools are enacting homework bans similar to those enacted at the start of the century. Teachers have varying opinions on the bans, while parents attempt to cope with the disruption to their daily routine that such bans cause.

Flipped Classroom: Everything You Need to Know

25 black history month activities.

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

16 Ways to Encourage Students to Behave Appropriately While Moving with Groups

Helping Teachers Use Technology and Technology Experts Teach

What Are the Drawbacks of Using Virtual Reality in K-12 Schools?

23 Strategies to Help Students Who Do Not Possess Word Comprehension Skills

17 Ways to Support Students With Expressive Language

The Ultimate List of Third Grade Sight Words

Who Invented Homework and Why

Who Invented Homework

Italian pedagog, Roberto Nevilis, was believed to have invented homework back in 1905 to help his students foster productive studying habits outside of school. However, we'll sound find out that the concept of homework has been around for much longer.

Homework, which most likely didn't have a specific term back then, already existed even in ancient civilizations. Think Greece, Rome, and even ancient Egypt. Over time, homework became standardized in our educational systems. This happened naturally over time, as the development of the formal education system continued.

In this article, we're going to attempt to find out who invented homework, and when was homework invented, and we're going to uncover if the creator of homework is a single person or a group of them. Read this article through to the end to find out.

Who Created Homework and When?

The concept of homework predates modern educational systems, with roots in ancient Rome. However, Roberto Nevilis is often, yet inaccurately, credited with inventing homework in 1905.Depending on various sources, this invention is dated either in the year 1095 or 1905.

The invention of homework is commonly attributed to Roberto Nevilis, an Italian pedagog who is said to have introduced it as a form of punishment for his students in 1905. However, the concept of homework predates Nevilis and has roots that go back much further in history.

The practice of assigning students work to be done outside of class time can be traced back to ancient civilizations, such as Rome, where Pliny the Younger (AD 61–113) encouraged his students to practice public speaking at home to improve their oratory skills.

It's important to note that the idea of formalized homework has evolved significantly over centuries, influenced by educational theories and pedagogical developments. The purpose and nature of homework have been subjects of debate among educators, with opinions varying on its effectiveness and impact on student learning and well-being.

It might be impossible to answer when was homework invented. A simpler question to ask is ‘what exactly is homework?’.

If you define it as work assigned to do outside of a formal educational setup, then homework might be as old as humanity itself. When most of what people studied were crafts and skills, practicing them outside of dedicated learning times may as well have been considered homework.

Let’s look at a few people who have been credited with formalizing homework over the past few thousand years.

Roberto Nevilis

Stories and speculations on the internet claim Roberto Nevilis is the one who invented school homework, or at least was the first person to assign homework back in 1905.

Who was he? He was an Italian educator who lived in Venice. He wanted to discipline and motivate his class of lackluster students. Unfortunately, claims online lack factual basis and strong proof that Roberto did invent homework.

Homework, as a concept, predates Roberto, and can't truly be assigned to a sole inventor. Moreover, it's hard to quantify where an idea truly emerges, because many ideas emerge from different parts of the world simultaneously or at similar times, therefore it's hard to truly pinpoint who invented this idea.

Pliny the Younger

Another culprit according to the internet lived a thousand years before Roberto Nevilis. Pliny the Younger was an oratory teacher in the first century AD in the Roman Empire.

He apparently asked his students to practice their oratory skills at home, which some people consider one of the first official versions of homework.

It is difficult to say with any certainty if this is the first time homework was assigned though because the idea of asking students to practice something outside classes probably existed in every human civilization for millennia.

Horace Mann

To answer the question of who invented homework and why, at least in the modern sense, we have to talk about Horace Mann. Horace Mann was an American educator and politician in the 19th century who was heavily influenced by movements in the newly-formed German state.

He is credited for bringing massive educational reform to America, and can definitely be considered the father of modern homework in the United States. However, his ideas were heavily influenced by the founding father of German nationalism Johann Gottlieb Fichte.

After the defeat of Napoleon and the liberation of Prussia in 1814, citizens went back to their own lives, there was no sense of national pride or German identity. Johann Gottlieb Fichte came up with the idea of Volkschule, a mandatory 9-year educational system provided by the government to combat this.

Homework already existed in Germany at this point in time but it became a requirement in Volkschule. Fichte wasn't motivated purely by educational reform, he wanted to demonstrate the positive impact and power of a centralized government, and assigning homework was a way of showing the state's power to influence personal and public life.

This effort to make citizens more patriotic worked and the system of education and homework slowly spread through Europe.

Horace Mann saw the system at work during a trip to Prussia in the 1840s and brought many of the concepts to America, including homework.

Who Invented Homework and Why?

Homework's history and objectives have evolved significantly over time, reflecting changing educational goals. Now, that we've gone through its history a bit, let's try to understand the "why". The people or people who made homework understood the advantages of it. Let's consider the following:

- Repetition, a key factor in long-term memory retention, is a primary goal of homework. It helps students solidify class-learned information. This is especially true in complex subjects like physics, where physics homework help can prove invaluable to learning effectively.

- Homework bridges classroom learning with real-world applications, enhancing memory and understanding.

- It identifies individual student weaknesses, allowing focused efforts to address them.

- Working independently at their own pace, students can overcome the distractions and constraints of a classroom setting through homework.

- By creating a continuous learning flow, homework shifts the perspective from viewing each school day as isolated to seeing education as an ongoing process.

- Homework is crucial for subjects like mathematics and sciences, where repetition is necessary to internalize complex processes.

- It's a tool for teachers to maximize classroom time, focusing on expanding understanding rather than just drilling fundamentals.

- Responsibility is a key lesson from homework. Students learn to manage time and prioritize tasks to meet deadlines.

- Research skills get honed through homework as students gather information from various sources.

- Students' creative potential is unleashed in homework, free from classroom constraints.

Struggling with your Homework?

Get your assignments done by real pros. Save your precious time and boost your marks with ease.

Who Invented Homework: Development in the 1900s

Thanks to Horace Mann, homework had become widespread in the American schooling system by 1900, but it wasn't universally popular amongst either students or parents.

The early 1900s homework bans

In 1901, California became the first state to ban homework. Since homework had made its way into the American educational system there had always been people who were against it for some surprising reasons.

Back then, children were expected to help on farms and family businesses, so homework was unpopular amongst parents who expected their children to help out at home. Many students also dropped out of school early because they found homework tedious and difficult.

Publications like Ladies' Home Journal and The New York Times printed statements and articles about the detrimental effects of homework on children's health.

The 1930 child labor laws

Homework became more common in the U.S. around the early 1900s. As to who made homework mandatory, the question remains open, but its emergence in the mainstream sure proved beneficial. Why is this?

Well, in 1930, child labor laws were created. It aimed to protect children from being exploited for labor and it made sure to enable children to have access to education and schooling. The timing was just right.

Speaking of homework, if you’re reading this article and have homework you need to attend to, send a “ do my homework ” request on Studyfy and instantly get the help of a professional right now.

Progressive reforms of the 1940s and 50s

With more research into education, psychology and memory, the importance of education became clear. Homework was understood as an important part of education and it evolved to become more useful and interesting to students.

Homework during the Cold War

Competition with the Soviet Union fueled many aspects of American life and politics. In a post-nuclear world, the importance of Science and Technology was evident.

The government believed that students had to be well-educated to compete with Soviet education systems. This is the time when homework became formalized, accepted, and a fundamental part of the American educational system.

1980s Nation at Risk

In 1983 the National Commission on Excellence in Education published Nation at Risk:

The Imperative for Educational Reform, a report about the poor condition of education in America. Still in the Cold War, this motivated the government in 1986 to talk about the benefits of homework in a pamphlet called “What Works” which highlighted the importance of homework.

Did you like our Homework Post?

For more help, tap into our pool of professional writers and get expert essay editing services!

Who Invented Homework: The Modern Homework Debate

Like it or not, homework has stuck through the times, remaining a central aspect in education since the end of the Cold War in 1991. So, who invented homework 😡 and when was homework invented?

We’ve tried to pinpoint different sources, and we’ve understood that many historical figures have contributed to its conception.

Horace Mann, in particular, was the man who apparently introduced homework in the U.S. But let’s reframe our perspective a bit. Instead of focusing on who invented homework, let’s ask ourselves why homework is beneficial in the first place. Let’s consider the pros and cons:

- Homework potentially enhances memory.

- Homework helps cultivate time management, self-learning, discipline, and cognitive skills.

- An excessive amount of work can cause mental health issues and burnout.

- Rigid homework tasks can take away time for productive and leisurely activities like arts and sports.

Meaningful homework tasks can challenge us and enrich our knowledge on certain topics, but too much homework can actually be detrimental. This is where Studyfy can be invaluable. Studyfy offers homework help.

All you need to do is click the “ do my assignment ” button and send us a request. Need instant professional help? You know where to go now.

Frequently asked questions

Who made homework.

As stated throughout the article, there was no sole "inventor of homework." We've established that homework has already existed in ancient civilizations, where people were assigned educational tasks to be done at home.

Let's look at ancient Greece; for example, students at the Academy of Athens were expected to recite and remember epic poems outside of their institutions. Similar practices were going on in ancient Egypt, China and Rome.

This is why we can't ascertain the sole inventor of homework. While history can give us hints that homework was practiced in different civilizations, it's not far-fetched to believe that there have been many undocumented events all across the globe that happened simultaneously where homework emerged.

Why was homework invented?

We've answered the question of "who invented homework 😡" and we've recognized that we cannot pinpoint it to one sole inventor. So, let's get back to the question of why homework was invented.

Homework arose from educational institutions, remained, and probably was invented because teachers and educators wanted to help students reinforce what they learned during class. They also believed that homework could improve memory and cognitive skills over time, as well as instill a sense of discipline.

In other words, homework's origins can be linked to academic performance and regular students practice. Academic life has replaced the anti-homework sentiment as homework bans proved to cause partial learning and a struggle to achieve conceptual clarity.

Speaking of, don't forget that Studyfy can help you with your homework, whether it's Python homework help or another topic. Don't wait too long to take advantage of expert help when you can do it now.

Is homework important for my learning journey?

Now that we've answered questions on who created homework and why it was invented, we can ask ourselves if homework is crucial in our learning journey.

At the end of the day, homework can be a crucial step to becoming more knowledgeable and disciplined over time.

Exercising our memory skills, learning independently without a teacher obliging us, and processing new information are all beneficial to our growth and evolution. However, whether a homework task is enriching or simply a filler depends on the quality of education you're getting.

The Cult of Homework

America’s devotion to the practice stems in part from the fact that it’s what today’s parents and teachers grew up with themselves.

America has long had a fickle relationship with homework. A century or so ago, progressive reformers argued that it made kids unduly stressed , which later led in some cases to district-level bans on it for all grades under seventh. This anti-homework sentiment faded, though, amid mid-century fears that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union (which led to more homework), only to resurface in the 1960s and ’70s, when a more open culture came to see homework as stifling play and creativity (which led to less). But this didn’t last either: In the ’80s, government researchers blamed America’s schools for its economic troubles and recommended ramping homework up once more.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s . Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study , for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

But not without pushback. As many children, not to mention their parents and teachers, are drained by their daily workload, some schools and districts are rethinking how homework should work—and some teachers are doing away with it entirely. They’re reviewing the research on homework (which, it should be noted, is contested) and concluding that it’s time to revisit the subject.

Read: My daughter’s homework is killing me

Hillsborough, California, an affluent suburb of San Francisco, is one district that has changed its ways. The district, which includes three elementary schools and a middle school, worked with teachers and convened panels of parents in order to come up with a homework policy that would allow students more unscheduled time to spend with their families or to play. In August 2017, it rolled out an updated policy, which emphasized that homework should be “meaningful” and banned due dates that fell on the day after a weekend or a break.

“The first year was a bit bumpy,” says Louann Carlomagno, the district’s superintendent. She says the adjustment was at times hard for the teachers, some of whom had been doing their job in a similar fashion for a quarter of a century. Parents’ expectations were also an issue. Carlomagno says they took some time to “realize that it was okay not to have an hour of homework for a second grader—that was new.”

Most of the way through year two, though, the policy appears to be working more smoothly. “The students do seem to be less stressed based on conversations I’ve had with parents,” Carlomagno says. It also helps that the students performed just as well on the state standardized test last year as they have in the past.

Earlier this year, the district of Somerville, Massachusetts, also rewrote its homework policy, reducing the amount of homework its elementary and middle schoolers may receive. In grades six through eight, for example, homework is capped at an hour a night and can only be assigned two to three nights a week.

Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell whose daughter attends school in Somerville, is generally pleased with the new policy. But, he says, it’s part of a bigger, worrisome pattern. “The origin for this was general parental dissatisfaction, which not surprisingly was coming from a particular demographic,” Schneider says. “Middle-class white parents tend to be more vocal about concerns about homework … They feel entitled enough to voice their opinions.”

Schneider is all for revisiting taken-for-granted practices like homework, but thinks districts need to take care to be inclusive in that process. “I hear approximately zero middle-class white parents talking about how homework done best in grades K through two actually strengthens the connection between home and school for young people and their families,” he says. Because many of these parents already feel connected to their school community, this benefit of homework can seem redundant. “They don’t need it,” Schneider says, “so they’re not advocating for it.”

That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that homework is more vital in low-income districts. In fact, there are different, but just as compelling, reasons it can be burdensome in these communities as well. Allison Wienhold, who teaches high-school Spanish in the small town of Dunkerton, Iowa, has phased out homework assignments over the past three years. Her thinking: Some of her students, she says, have little time for homework because they’re working 30 hours a week or responsible for looking after younger siblings.

As educators reduce or eliminate the homework they assign, it’s worth asking what amount and what kind of homework is best for students. It turns out that there’s some disagreement about this among researchers, who tend to fall in one of two camps.

In the first camp is Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Cooper conducted a review of the existing research on homework in the mid-2000s , and found that, up to a point, the amount of homework students reported doing correlates with their performance on in-class tests. This correlation, the review found, was stronger for older students than for younger ones.

This conclusion is generally accepted among educators, in part because it’s compatible with “the 10-minute rule,” a rule of thumb popular among teachers suggesting that the proper amount of homework is approximately 10 minutes per night, per grade level—that is, 10 minutes a night for first graders, 20 minutes a night for second graders, and so on, up to two hours a night for high schoolers.

In Cooper’s eyes, homework isn’t overly burdensome for the typical American kid. He points to a 2014 Brookings Institution report that found “little evidence that the homework load has increased for the average student”; onerous amounts of homework, it determined, are indeed out there, but relatively rare. Moreover, the report noted that most parents think their children get the right amount of homework, and that parents who are worried about under-assigning outnumber those who are worried about over-assigning. Cooper says that those latter worries tend to come from a small number of communities with “concerns about being competitive for the most selective colleges and universities.”

According to Alfie Kohn, squarely in camp two, most of the conclusions listed in the previous three paragraphs are questionable. Kohn, the author of The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing , considers homework to be a “reliable extinguisher of curiosity,” and has several complaints with the evidence that Cooper and others cite in favor of it. Kohn notes, among other things, that Cooper’s 2006 meta-analysis doesn’t establish causation, and that its central correlation is based on children’s (potentially unreliable) self-reporting of how much time they spend doing homework. (Kohn’s prolific writing on the subject alleges numerous other methodological faults.)

In fact, other correlations make a compelling case that homework doesn’t help. Some countries whose students regularly outperform American kids on standardized tests, such as Japan and Denmark, send their kids home with less schoolwork , while students from some countries with higher homework loads than the U.S., such as Thailand and Greece, fare worse on tests. (Of course, international comparisons can be fraught because so many factors, in education systems and in societies at large, might shape students’ success.)

Kohn also takes issue with the way achievement is commonly assessed. “If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores,” he says. “But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive.”

His concern is, in a way, a philosophical one. “The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough,” Kohn says. What about homework’s effect on quality time spent with family? On long-term information retention? On critical-thinking skills? On social development? On success later in life? On happiness? The research is quiet on these questions.

Another problem is that research tends to focus on homework’s quantity rather than its quality, because the former is much easier to measure than the latter. While experts generally agree that the substance of an assignment matters greatly (and that a lot of homework is uninspiring busywork), there isn’t a catchall rule for what’s best—the answer is often specific to a certain curriculum or even an individual student.

Given that homework’s benefits are so narrowly defined (and even then, contested), it’s a bit surprising that assigning so much of it is often a classroom default, and that more isn’t done to make the homework that is assigned more enriching. A number of things are preserving this state of affairs—things that have little to do with whether homework helps students learn.

Jack Schneider, the Massachusetts parent and professor, thinks it’s important to consider the generational inertia of the practice. “The vast majority of parents of public-school students themselves are graduates of the public education system,” he says. “Therefore, their views of what is legitimate have been shaped already by the system that they would ostensibly be critiquing.” In other words, many parents’ own history with homework might lead them to expect the same for their children, and anything less is often taken as an indicator that a school or a teacher isn’t rigorous enough. (This dovetails with—and complicates—the finding that most parents think their children have the right amount of homework.)

Barbara Stengel, an education professor at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, brought up two developments in the educational system that might be keeping homework rote and unexciting. The first is the importance placed in the past few decades on standardized testing, which looms over many public-school classroom decisions and frequently discourages teachers from trying out more creative homework assignments. “They could do it, but they’re afraid to do it, because they’re getting pressure every day about test scores,” Stengel says.

Second, she notes that the profession of teaching, with its relatively low wages and lack of autonomy, struggles to attract and support some of the people who might reimagine homework, as well as other aspects of education. “Part of why we get less interesting homework is because some of the people who would really have pushed the limits of that are no longer in teaching,” she says.

“In general, we have no imagination when it comes to homework,” Stengel says. She wishes teachers had the time and resources to remake homework into something that actually engages students. “If we had kids reading—anything, the sports page, anything that they’re able to read—that’s the best single thing. If we had kids going to the zoo, if we had kids going to parks after school, if we had them doing all of those things, their test scores would improve. But they’re not. They’re going home and doing homework that is not expanding what they think about.”

“Exploratory” is one word Mike Simpson used when describing the types of homework he’d like his students to undertake. Simpson is the head of the Stone Independent School, a tiny private high school in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that opened in 2017. “We were lucky to start a school a year and a half ago,” Simpson says, “so it’s been easy to say we aren’t going to assign worksheets, we aren’t going assign regurgitative problem sets.” For instance, a half-dozen students recently built a 25-foot trebuchet on campus.

Simpson says he thinks it’s a shame that the things students have to do at home are often the least fulfilling parts of schooling: “When our students can’t make the connection between the work they’re doing at 11 o’clock at night on a Tuesday to the way they want their lives to be, I think we begin to lose the plot.”

When I talked with other teachers who did homework makeovers in their classrooms, I heard few regrets. Brandy Young, a second-grade teacher in Joshua, Texas, stopped assigning take-home packets of worksheets three years ago, and instead started asking her students to do 20 minutes of pleasure reading a night. She says she’s pleased with the results, but she’s noticed something funny. “Some kids,” she says, “really do like homework.” She’s started putting out a bucket of it for students to draw from voluntarily—whether because they want an additional challenge or something to pass the time at home.

Chris Bronke, a high-school English teacher in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove, told me something similar. This school year, he eliminated homework for his class of freshmen, and now mostly lets students study on their own or in small groups during class time. It’s usually up to them what they work on each day, and Bronke has been impressed by how they’ve managed their time.

In fact, some of them willingly spend time on assignments at home, whether because they’re particularly engaged, because they prefer to do some deeper thinking outside school, or because they needed to spend time in class that day preparing for, say, a biology test the following period. “They’re making meaningful decisions about their time that I don’t think education really ever gives students the experience, nor the practice, of doing,” Bronke said.

The typical prescription offered by those overwhelmed with homework is to assign less of it—to subtract. But perhaps a more useful approach, for many classrooms, would be to create homework only when teachers and students believe it’s actually needed to further the learning that takes place in class—to start with nothing, and add as necessary.

History of Homework

The institution of homework is deeply embedded in the American culture. How many times as a child have you heard your parents say that you can’t go outside, play games, or get dessert until you have finished your homework? Or how many times have you uttered that phrase to your own children? Although the concept of a homework assignment has been questioned throughout history, and probably will be, time and time again, it is still viewed as something normal, and as a part of every student’s life. Even outside the school, phrases like “you haven’t done your homework on that pitch/project” are used to suggest that a person hasn’t done all they could have done to prepare for a certain challenge.

Now, over time, the public’s attitude toward homework has changed numerous times, keeping in line with then active social trends and philosophies, and that battle is still raging on today. But before we take a look at what the future holds for the concept of homework, let’s take a trip down memory lane first. You will find that the arguments in favor or against homework were almost exactly the same as they are today.

Homework through History

Seeing as primary education at the end of 19th century was not mandatory, student attendance couldn’t be described as regular. The classrooms were a lot different, as well, with students of different ages sitting together in the same class. Moreover, a very small percentage of children would choose to pursue education past the 4th grade. Once they have learned to read, write, and do some basic arithmetic, they would leave school in order to find work or to help around the house. Homework was rare occurrence, because setting aside a few hours for learning each night interfered with their chores and daily obligations.

As education became more available and more progressive at the turn of the 20th century, there was a strong rebellion against homework taking place in academic circles. Even pediatricians got in on the debate, stating that children should not be made to do homework, as it robs them of all the benefits provided by physical activities and time spent outside the house. Seeing as conditions such as the attention deficit disorder were not diagnosed back then, homework was to blame.

This anti-homework movement reached its peak in the 1930s, with a Society for the Abolition of Homework being formed in order to prevent schools from giving students homework, with numerous school districts following their lead. Even in those schools where homework was not abolished, very few homework assignments were given. This continued all the way until the end of the 1950s, which marked a sharp turn in country’s attitude towards homework.

The reason for this was the launch of the Sputnik I satellite by the Soviet Union in 1957. Seeing as the entire Cold War era was marked by the constant competition between USA and the Soviet Union, U.S. educators, teachers, and even parents were afraid that their children, and the entire nation, would be left behind by their Soviet counterparts, who would lead the way into the future, which meant that homework was once again back on the map, and more important than ever.

Things changed again in the late 60s and early 70s. Vietnam War was still raging on, giving birth to civil rights movement and counterculture, which were looking to shake up all of the previously established norms. Homework was yet again under the microscope. It was argued that homework got in the way of kids socializing, and even their sleep, which meant that homework had yet again fallen from grace, just like it had at the beginning of the century.

In the 1980s, the climate changed again, spurred on by the study called A Nation at Risk which blamed the shaky U.S. economy on schools which weren’t challenging their students enough. As a result, the entire school system was labeled as mediocre in an age where the entire country was striving toward excellence, as saw the bright young minds of tomorrow as its way out. There was more of everything: classes, grades, tests, and more homework. This trend spilled over into the 90s, as well.

At the end of the 90s, homework was yet again under the attack. It was cited that children are overworked and stressed out. The increasing demand for tutors was the key argument. If students needed homework assignment help, there was too much of it. But, besides homework help, homework was also viewed as an obstacle for families with two working parents. The only time parents would get to spend time with their children was being usurped, as kids were forced to work on their homework for hours.

Present Day