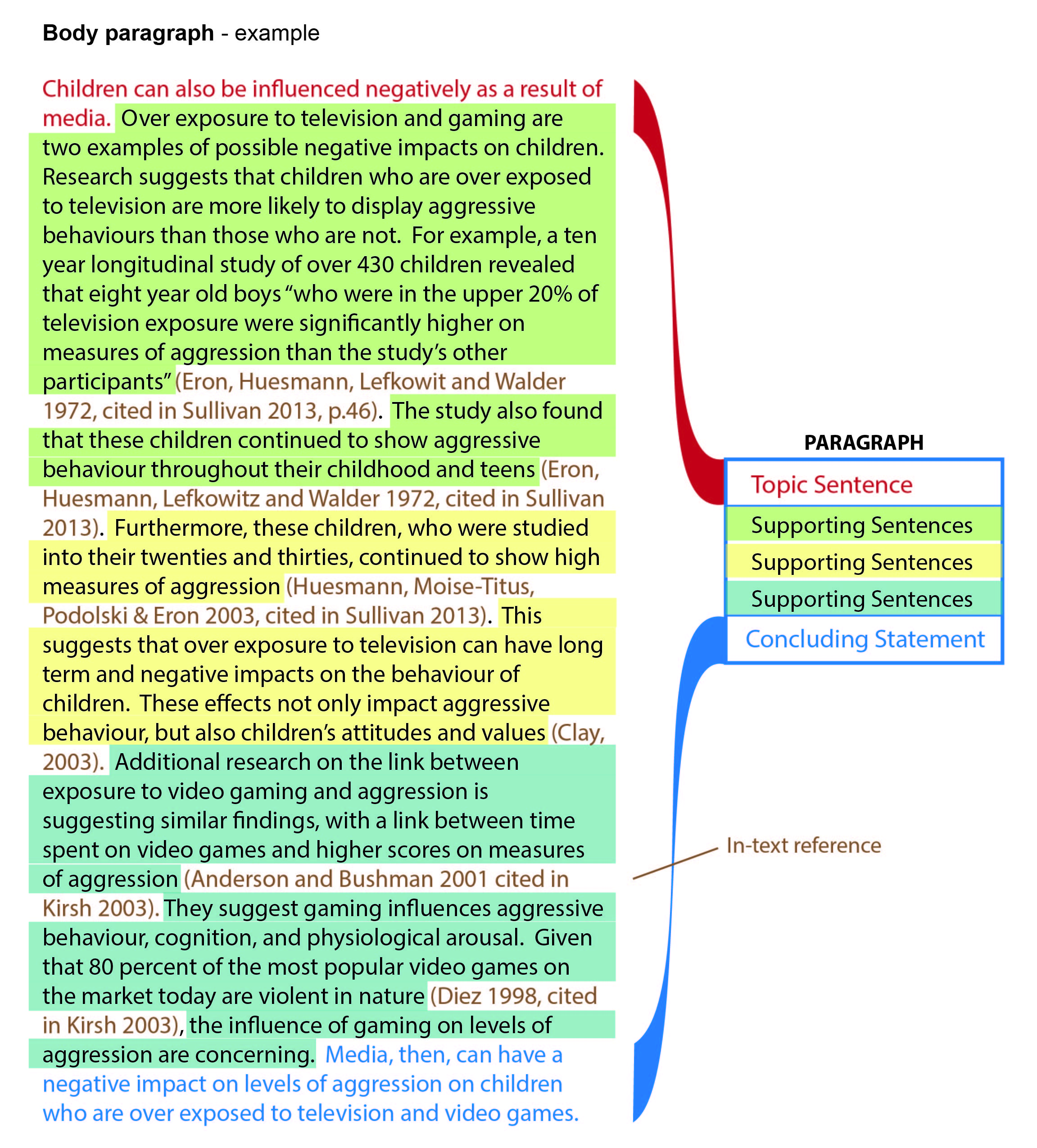

Body Paragraph

Definition of body paragraph.

A body paragraph in an essay is a paragraph that comes between the introduction and the conclusion . In a five-paragraph essay, there are three body paragraphs, while in longer essays there could be five or even ten. In major research papers, there are hundreds of body paragraphs.

Components of a Body Paragraph

A body paragraph has three major components: (1) topic sentence , (2) explanation, (3) supporting details. Without any of them, the body paragraph seems to be missing something, and will not add anything to the theme and central idea of the essay.

- Topic Sentence The topic sentence is the first sentence of a paragraph, and states the main idea to be discussed in the paragraph. In a body paragraph, the topic sentence is always about the evidence given in the thesis statement of the essay. It could be a claim , an assertion , or a fact needing explanation. It is generally a statement or a declarative sentence.

- Explanation / Example The topic sentence is followed by an explanation and/or an example. Whatever it is, it generally starts with “in other words” or “it means;” or “for example,” “for instance,” etc. This is called “metacommentary,” or telling of the same thing in different words to explain it further, so that readers can understand.

- Supporting Details Supporting details include concrete examples, rather than explanation or metacommentary. In common essays, or five-paragraph essays, this is just a one-sentence example from everyday life. However, in the case of research essays, these are usually quotes and statistics from research studies.

Different Between an Introduction and a Body Paragraph

Although both are called paragraphs, both are very different from each other not only in terms of functions but also in terms of components. An introduction occurs in the beginning and has three major components; a hook , background information , and a thesis statement . However, a body paragraph is comprised of a topic sentence making a claim, an explanation or example of the claim, and supporting details.

Examples of Body Paragraph in Literature

Example #1: autobiography of bertrand russell (by bertrand russell).

“Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind. These passions, like great winds, have blown me hither and thither, in a wayward course, over a great ocean of anguish, reaching to the very verge of despair. I have sought love, first, because it brings ecstasy – ecstasy so great that I would often have sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of this joy. I have sought it, next, because it relieves loneliness – that terrible loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss. I have sought it finally, because in the union of love I have seen, in a mystic miniature, the prefiguring vision of the heaven that saints and poets have imagined. This is what I sought, and though it might seem too good for human life, this is what – at last – I have found.”

This is a paragraph from the prologue of the autobiography of Bertrand Russell. Check its first topic sentence, which explains something that is further elaborated in the following sentences.

Example #2: Politics and the English Language (by George Orwell)

“The inflated style itself is a kind of euphemism . A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow , blurring the outline and covering up all the details. The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms , like a cuttlefish spurting out ink. In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics.’ All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred, and schizophrenia. When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer. I should expect to find — this is a guess which I have not sufficient knowledge to verify — that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.”

This paragraph has a very short topic sentence. However, its explanation and further supporting details are very long.

Function of Body Paragraph

The elements of a body paragraph help to elaborate a concept, organize ideas into a single whole, and help bridge a gap in thoughts. The major task of a body paragraph is the organization of thoughts in a unified way. It also helps an author to give examples to support his claim, given in the topic sentence of that body paragraph. A good paragraph helps readers understand the main idea with examples.

Related posts:

- Simple Paragraph

Post navigation

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Body Paragraphs

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource outlines the generally accepted structure for introductions, body paragraphs, and conclusions in an academic argument paper. Keep in mind that this resource contains guidelines and not strict rules about organization. Your structure needs to be flexible enough to meet the requirements of your purpose and audience.

Body paragraphs: Moving from general to specific information

Your paper should be organized in a manner that moves from general to specific information. Every time you begin a new subject, think of an inverted pyramid - The broadest range of information sits at the top, and as the paragraph or paper progresses, the author becomes more and more focused on the argument ending with specific, detailed evidence supporting a claim. Lastly, the author explains how and why the information she has just provided connects to and supports her thesis (a brief wrap-up or warrant).

Moving from General to Specific Information

The four elements of a good paragraph (TTEB)

A good paragraph should contain at least the following four elements: T ransition, T opic sentence, specific E vidence and analysis, and a B rief wrap-up sentence (also known as a warrant ) –TTEB!

- A T ransition sentence leading in from a previous paragraph to assure smooth reading. This acts as a hand-off from one idea to the next.

- A T opic sentence that tells the reader what you will be discussing in the paragraph.

- Specific E vidence and analysis that supports one of your claims and that provides a deeper level of detail than your topic sentence.

- A B rief wrap-up sentence that tells the reader how and why this information supports the paper’s thesis. The brief wrap-up is also known as the warrant. The warrant is important to your argument because it connects your reasoning and support to your thesis, and it shows that the information in the paragraph is related to your thesis and helps defend it.

Supporting evidence (induction and deduction)

Induction is the type of reasoning that moves from specific facts to a general conclusion. When you use induction in your paper, you will state your thesis (which is actually the conclusion you have come to after looking at all the facts) and then support your thesis with the facts. The following is an example of induction taken from Dorothy U. Seyler’s Understanding Argument :

There is the dead body of Smith. Smith was shot in his bedroom between the hours of 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m., according to the coroner. Smith was shot with a .32 caliber pistol. The pistol left in the bedroom contains Jones’s fingerprints. Jones was seen, by a neighbor, entering the Smith home at around 11:00 p.m. the night of Smith’s death. A coworker heard Smith and Jones arguing in Smith’s office the morning of the day Smith died.

Conclusion: Jones killed Smith.

Here, then, is the example in bullet form:

- Conclusion: Jones killed Smith

- Support: Smith was shot by Jones’ gun, Jones was seen entering the scene of the crime, Jones and Smith argued earlier in the day Smith died.

- Assumption: The facts are representative, not isolated incidents, and thus reveal a trend, justifying the conclusion drawn.

When you use deduction in an argument, you begin with general premises and move to a specific conclusion. There is a precise pattern you must use when you reason deductively. This pattern is called syllogistic reasoning (the syllogism). Syllogistic reasoning (deduction) is organized in three steps:

- Major premise

- Minor premise

In order for the syllogism (deduction) to work, you must accept that the relationship of the two premises lead, logically, to the conclusion. Here are two examples of deduction or syllogistic reasoning:

- Major premise: All men are mortal.

- Minor premise: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

- Major premise: People who perform with courage and clear purpose in a crisis are great leaders.

- Minor premise: Lincoln was a person who performed with courage and a clear purpose in a crisis.

- Conclusion: Lincoln was a great leader.

So in order for deduction to work in the example involving Socrates, you must agree that (1) all men are mortal (they all die); and (2) Socrates is a man. If you disagree with either of these premises, the conclusion is invalid. The example using Socrates isn’t so difficult to validate. But when you move into more murky water (when you use terms such as courage , clear purpose , and great ), the connections get tenuous.

For example, some historians might argue that Lincoln didn’t really shine until a few years into the Civil War, after many Union losses to Southern leaders such as Robert E. Lee.

The following is a clear example of deduction gone awry:

- Major premise: All dogs make good pets.

- Minor premise: Doogle is a dog.

- Conclusion: Doogle will make a good pet.

If you don’t agree that all dogs make good pets, then the conclusion that Doogle will make a good pet is invalid.

When a premise in a syllogism is missing, the syllogism becomes an enthymeme. Enthymemes can be very effective in argument, but they can also be unethical and lead to invalid conclusions. Authors often use enthymemes to persuade audiences. The following is an example of an enthymeme:

If you have a plasma TV, you are not poor.

The first part of the enthymeme (If you have a plasma TV) is the stated premise. The second part of the statement (you are not poor) is the conclusion. Therefore, the unstated premise is “Only rich people have plasma TVs.” The enthymeme above leads us to an invalid conclusion (people who own plasma TVs are not poor) because there are plenty of people who own plasma TVs who are poor. Let’s look at this enthymeme in a syllogistic structure:

- Major premise: People who own plasma TVs are rich (unstated above).

- Minor premise: You own a plasma TV.

- Conclusion: You are not poor.

To help you understand how induction and deduction can work together to form a solid argument, you may want to look at the United States Declaration of Independence. The first section of the Declaration contains a series of syllogisms, while the middle section is an inductive list of examples. The final section brings the first and second sections together in a compelling conclusion.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How To Write Essay Body Paragraphs

3-minute read

- 4th October 2022

Writing essays is an unavoidable part of student life . And even if you’re not pursuing a career that involves much writing, if you can boost the quality of your essays , you’ll improve your grades and have a better chance of reaching your goals.

One effective way to improve your writing is to strengthen your essay body paragraphs. Those are the paragraphs between the introduction and the conclusion. In our guide below, we’ll consider four components of body paragraphs:

● Purpose

● Evidence

● Analysis

● Connection

For each paragraph you write , ask yourself: Why are you writing this paragraph? What point are you trying to make? This can be turned into a topic sentence, which is a brief sentence at the beginning of the paragraph clearly stating its focus.

Let’s say our essay is arguing that Fall is the best season, and, in this paragraph, we’re promoting the enjoyableness of Fall activities. Our topic sentence could be something like:

Fall activities, like apple picking, visiting a pumpkin patch, and playing in the leaves, are more enjoyable than activities in other seasons.

Now that you have a clear idea of the point you’d like to make, you must support it with facts. You can do this by citing scientific and/or academic sources; sharing data from case studies; and providing information that you’ve discovered yourself, such as by conducting your own study or describing a real-life experience.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

We sent a survey to 100 participants. One question asked: “Which activity do you prefer: apple picking, building a snowman, planting flowers, or kayaking?” Sixty percent of respondents chose apple picking.

Now that you’ve provided evidence, critically analyzing it is key to strengthening your essay. This involves explaining how the presented facts support your argument, what counterarguments exist, and if there are any alternative points of view.

Although the response to one question indicated that 55% of respondents prefer swimming to jumping in piles of leaves, the responses to the rest of the questions in the survey showed that most participants chose Fall activities as their favorites. These findings indicate that Fall activities are more enjoyable than other types of activities.

Each paragraph must be connected to the paragraphs around it and the main point. You can achieve this by using transitional words and sentences at the end of the paragraph to summarize the current paragraph’s findings and introduce the next one. Transition words include likewise , however , furthermore , accordingly , and in summary .

Therefore, Fall is the best season when it comes to activities. Furthermore, the clothing worn during this season is also superior.

Proofreading and Editing

This step should not be overlooked. Even the best writers will miss errors in their own writing, so it’s crucial to have an outside pair of eyes check your work for spelling, grammar, punctuation, sentence structure, and readability.

Our expert editors can also ensure your referencing style is followed correctly, offer suggestions for areas where your meaning isn’t clear, and even format your document for you! Try our service for free today by uploading a 500-word sample .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

What is a content editor.

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

10 min read

How to write strong essay body paragraphs (with examples)

In this blog post, we'll discuss how to write clear, convincing essay body paragraphs using many examples. We'll also be writing paragraphs together. By the end, you'll have a good understanding of how to write a strong essay body for any topic.

Table of Contents

Introduction, how to structure a body paragraph, creating an outline for our essay body, 1. a strong thesis statment takes a stand, 2. a strong thesis statement allows for debate, 3. a strong thesis statement is specific, writing the first essay body paragraph, how not to write a body paragraph, writing the second essay body paragraph.

After writing a great introduction to our essay, let's make our case in the body paragraphs. These are where we will present our arguments, back them up with evidence, and, in most cases, refute counterarguments. Introductions are very similar across the various types of essays. For example, an argumentative essay's introduction will be near identical to an introduction written for an expository essay. In contrast, the body paragraphs are structured differently depending on the type of essay.

In an expository essay, we are investigating an idea or analyzing the circumstances of a case. In contrast, we want to make compelling points with an argumentative essay to convince readers to agree with us.

The most straightforward technique to make an argument is to provide context first, then make a general point, and lastly back that point up in the following sentences. Not starting with your idea directly but giving context first is crucial in constructing a clear and easy-to-follow paragraph.

How to ideally structure a body paragraph:

- Provide context

- Make your thesis statement

- Support that argument

Now that we have the ideal structure for an argumentative essay, the best step to proceed is to outline the subsequent paragraphs. For the outline, we'll be writing one sentence that is simple in wording and describes the argument that we'll make in that paragraph concisely. Why are we doing that? An outline does more than give you a structure to work off of in the following essay body, thereby saving you time. It also helps you not to repeat yourself or, even worse, to accidentally contradict yourself later on.

While working on the outline, remember that revising your initial topic sentences is completely normal. They do not need to be flawless. Starting the outline with those thoughts can help accelerate writing the entire essay and can be very beneficial in avoiding writer's block.

For the essay body, we'll be proceeding with the topic we've written an introduction for in the previous article - the dangers of social media on society.

These are the main points I would like to make in the essay body regarding the dangers of social media:

Amplification of one's existing beliefs

Skewed comparisons

What makes a polished thesis statement?

Now that we've got our main points, let's create our outline for the body by writing one clear and straightforward topic sentence (which is the same as a thesis statement) for each idea. How do we write a great topic sentence? First, take a look at the three characteristics of a strong thesis statement.

Consider this thesis statement:

'While social media can have some negative effects, it can also be used positively.'

What stand does it take? Which negative and positive aspects does the author mean? While this one:

'Because social media is linked to a rise in mental health problems, it poses a danger to users.'

takes a clear stand and is very precise about the object of discussion.

If your thesis statement is not arguable, then your paper will not likely be enjoyable to read. Consider this thesis statement:

'Lots of people around the globe use social media.'

It does not allow for much discussion at all. Even if you were to argue that more or fewer people are using it on this planet, that wouldn't make for a very compelling argument.

'Although social media has numerous benefits, its various risks, including cyberbullying and possible addiction, mostly outweigh its benefits.'

Whether or not you consider this statement true, it allows for much more discussion than the previous one. It provides a basis for an engaging, thought-provoking paper by taking a position that you can discuss.

A thesis statement is one sentence that clearly states what you will discuss in that paragraph. It should give an overview of the main points you will discuss and show how these relate to your topic. For example, if you were to examine the rapid growth of social media, consider this thesis statement:

'There are many reasons for the rise in social media usage.'

That thesis statement is weak for two reasons. First, depending on the length of your essay, you might need to narrow your focus because the "rise in social media usage" can be a large and broad topic you cannot address adequately in a few pages. Secondly, the term "many reasons" is vague and does not give the reader an idea of what you will discuss in your paper.

In contrast, consider this thesis statement:

'The rise in social media usage is due to the increasing popularity of platforms like Facebook and Twitter, allowing users to connect with friends and share information effortlessly.'

Why is this better? Not only does it abide by the first two rules by allowing for debate and taking a stand, but this statement also narrows the subject down and identifies significant reasons for the increasing popularity of social media.

In conclusion : A strong thesis statement takes a clear stand, allows for discussion, and is specific.

Let's make use of how to write a good thopic sentence and put it into practise for our two main points from before. This is what good topic sentences could look like:

Echo chambers facilitated by social media promote political segregation in society.

Applied to the second argument:

Viewing other people's lives online through a distorted lens can lead to feelings of envy and inadequacy, as well as unrealistic expectations about one's life.

These topic sentences will be a very convenient structure for the whole body of our essay. Let's build out the first body paragraph, then closely examine how we did it so you can apply it to your essay.

Example: First body paragraph

If social media users mostly see content that reaffirms their existing beliefs, it can create an "echo chamber" effect. The echo chamber effect describes the user's limited exposure to diverse perspectives, making it challenging to examine those beliefs critically, thereby contributing to society's political polarization. This polarization emerges from social media becoming increasingly based on algorithms, which cater content to users based on their past interactions on the site. Further contributing to this shared narrative is the very nature of social media, allowing politically like-minded individuals to connect (Sunstein, 2018). Consequently, exposure to only one side of the argument can make it very difficult to see the other side's perspective, marginalizing opposing viewpoints. The entrenchment of one's beliefs by constant reaffirmation and amplification of political ideas results in segregation along partisan lines.

Sunstein, C. R (2018). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

In the first sentence, we provide context for the argument that we are about to make. Then, in the second sentence, we clearly state the topic we are addressing (social media contributing to political polarization).

Our topic sentence tells readers that a detailed discussion of the echo chamber effect and its consequences is coming next. All the following sentences, which make up most of the paragraph, either a) explain or b) support this point.

Finally, we answer the questions about how social media facilitates the echo chamber effect and the consequences. Try implementing the same structure in your essay body paragraph to allow for a logical and cohesive argument.

These paragraphs should be focused, so don't incorporate multiple arguments into one. Squeezing ideas into a single paragraph makes it challenging for readers to follow your reasoning. Instead, reserve each body paragraph for a single statement to be discussed and only switch to the next section once you feel that you thoroughly explained and supported your topic sentence.

Let's look at an example that might seem appropriate initially but should be modified.

Negative example: Try identifying the main argument

Over the past decade, social media platforms have become increasingly popular methods of communication and networking. However, these platforms' algorithmic nature fosters echo chambers or online spaces where users only encounter information that reinforces their existing beliefs. This echo chamber effect can lead to a lack of understanding or empathy for those with different perspectives and can even amplify the effects of confirmation bias. The same principle of one-sided exposure to opinions can be abstracted and applied to the biased subjection to lifestyles we see on social media. The constant exposure to these highly-curated and often unrealistic portrayals of other people's lives can lead us to believe that our own lives are inadequate in comparison. These feelings of inadequacy can be especially harmful to young people, who are still developing their sense of self.

Let's analyze this essay paragraph. Introducing the topic sentence by stating the social functions of social media is very useful because it provides context for the following argument. Naming those functions in the first sentence also allows for a smooth transition by contrasting the initial sentence ("However, ...") with the topic sentence. Also, the topic sentence abides by our three rules for creating a strong thesis statement:

- Taking a clear stand: algorithms are substantial contributors to the echo chamber effect

- Allowing for debate: there is literature rejecting this claim

- Being specific: analyzing a specific cause of the effect (algorithms).

So, where's the problem with this body paragraph?

It begins with what seems like a single argument (social media algorithms contributing to the echo chamber effect). Yet after addressing the consequences of the echo-chamber effect right after the thesis sentence, the author applies the same principle to a whole different topic. At the end of the paragraph, the reader is probably feeling confused. What was the paragraph trying to achieve in the first place?

We should place the second idea of being exposed to curated lifestyles in a separate section instead of shoehorning it into the end of the first one. All sentences following the thesis statement should either explain it or provide evidence (refuting counterarguments falls into this category, too).

With our first body paragraph done and having seen an example of what to avoid, let's take the topic of being exposed to curated lifestyles through social media and construct a separate body paragraph for it. We have already provided sufficient context for the reader to follow our argument, so it is unnecessary for this particular paragraph.

Body paragraph 2

Another cause for social media's destructiveness is the users' inclination to only share the highlights of their lives on social media, consequently distorting our perceptions of reality. A highly filtered view of their life leads to feelings of envy and inadequacy, as well as a distorted understanding of what is considered ordinary (Liu et al., 2018). In addition, frequent social media use is linked to decreased self-esteem and body satisfaction (Perloff, 2014). One way social media can provide a curated view of people's lives is through filters, making photos look more radiant, shadier, more or less saturated, and similar. Further, editing tools allow people to fundamentally change how their photos and videos look before sharing them, allowing for inserting or removing certain parts of the image. Editing tools give people considerable control over how their photos and videos look before sharing them, thereby facilitating the curation of one's online persona.

Perloff, R.M. Social Media Effects on Young Women's Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles 71, 363–377 (2014).

Liu, Hongbo & Wu, Laurie & Li, Xiang. (2018). Social Media Envy: How Experience Sharing on Social Networking Sites Drives Millennials' Aspirational Tourism Consumption. Journal of Travel Research. 58. 10.1177/0047287518761615.

Dr. Jacob Neumann put it this way in his book A professors guide to writing essays: 'If you've written strong and clear topic sentences, you're well on your way to creating focused paragraphs.'

They provide the basis for each paragraph's development and content, allowing you not to get caught up in the details and lose sight of the overall objective. It's crucial not to neglect that step. Apply these principles to your essay body, whatever the topic, and you'll set yourself up for the best possible results.

Sources used for creating this article

- Writing a solid thesis statement : https://www.vwu.edu/academics/academic-support/learning-center/pdfs/Thesis-Statement.pdf

- Neumann, Jacob. A professor's guide to writing essays. 2016.

Follow the Journey

Hello! I'm Josh, the founder of Wordful. We aim to make a product that makes writing amazing content easy and fun. Sign up to gain access first when Wordful goes public!

How to Write a Body Paragraph for a College Essay

January 29, 2024

No matter the discipline, college success requires mastering several academic basics, including the body paragraph. This article will provide tips on drafting and editing a strong body paragraph before examining several body paragraph examples. Before we look at how to start a body paragraph and how to write a body paragraph for a college essay (or other writing assignment), let’s define what exactly a body paragraph is.

What is a Body Paragraph?

Simply put, a body paragraph consists of everything in an academic essay that does not constitute the introduction and conclusion. It makes up everything in between. In a five-paragraph, thesis-style essay (which most high schoolers encounter before heading off to college), there are three body paragraphs. Longer essays with more complex arguments will include many more body paragraphs.

We might correlate body paragraphs with bodily appendages—say, a leg. Both operate in a somewhat isolated way to perform specific operations, yet are integral to creating a cohesive, functioning whole. A leg helps the body sit, walk, and run. Like legs, body paragraphs work to move an essay along, by leading the reader through several convincing ideas. Together, these ideas, sometimes called topics, or points, work to prove an overall argument, called the essay’s thesis.

If you compared an essay on Kant’s theory of beauty to an essay on migratory birds, you’d notice that the body paragraphs differ drastically. However, on closer inspection, you’d probably find that they included many of the same key components. Most body paragraphs will include specific, detailed evidence, an analysis of the evidence, a conclusion drawn by the author, and several tie-ins to the larger ideas at play. They’ll also include transitions and citations leading the reader to source material. We’ll go into more detail on these components soon. First, let’s see if you’ve organized your essay so that you’ll know how to start a body paragraph.

How to Start a Body Paragraph

It can be tempting to start writing your college essay as soon as you sit down at your desk. The sooner begun, the sooner done, right? I’d recommend resisting that itch. Instead, pull up a blank document on your screen and make an outline. There are numerous reasons to make an outline, and most involve helping you stay on track. This is especially true of longer college papers, like the 60+ page dissertation some seniors are required to write. Even with regular writing assignments with a page count between 4-10, an outline will help you visualize your argumentation strategy. Moreover, it will help you order your key points and their relevant evidence from most to least convincing. This in turn will determine the order of your body paragraphs.

The most convincing sequence of body paragraphs will depend entirely on your paper’s subject. Let’s say you’re writing about Penelope’s success in outwitting male counterparts in The Odyssey . You may want to begin with Penelope’s weaving, the most obvious way in which Penelope dupes her suitors. You can end with Penelope’s ingenious way of outsmarting her own husband. Because this evidence is more ambiguous it will require a more nuanced analysis. Thus, it’ll work best as your final body paragraph, after readers have already been convinced of more digestible evidence. If in doubt, keep your body paragraph order chronological.

It can be worthwhile to consider your topic from multiple perspectives. You may decide to include a body paragraph that sets out to consider and refute an opposing point to your thesis. This type of body paragraph will often appear near the end of the essay. It works to erase any lingering doubts readers may have had, and requires strong rhetorical techniques.

How to Start a Body Paragraph, Continued

Once you’ve determined which key points will best support your argument and in what order, draft an introduction. This is a crucial step towards writing a body paragraph. First, it will set the tone for the rest of your paper. Second, it will require you to articulate your thesis statement in specific, concise wording. Highlight or bold your thesis statement, so you can refer back to it quickly. You should be looking at your thesis throughout the drafting of your body paragraphs.

Finally, make sure that your introduction indicates which key points you’ll be covering in your body paragraphs, and in what order. While this level of organization might seem like overkill, it will indicate to the reader that your entire paper is minutely thought-out. It will boost your reader’s confidence going in. They’ll feel reassured and open to your thought process if they can see that it follows a clear path.

Now that you have an essay outline and introduction, you’re ready to draft your body paragraphs.

How to Draft a Body Paragraph

At this point, you know your body paragraph topic, the key point you’re trying to make, and you’ve gathered your evidence. The next thing to do is write! The words highlighted in bold below comprise the main components that will make up your body paragraph. (You’ll notice in the body paragraph examples below that the order of these components is flexible.)

Start with a topic sentence . This will indicate the main point you plan to make that will work to support your overall thesis. Your topic sentence also alerts the reader to the change in topic from the last paragraph to the current one. In making this new topic known, you’ll want to create a transition from the last topic to this one.

Transitions appear in nearly every paragraph of a college essay, apart from the introduction. They create a link between disparate ideas. (For example, if your transition comes at the end of paragraph 4, you won’t need a second transition at the beginning of paragraph 5.) The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Writing Center has a page devoted to Developing Strategic Transitions . Likewise, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Writing Center offers help on paragraph transitions .

How to Draft a Body Paragraph for a College Essay ( Continued)

With the topic sentence written, you’ll need to prove your point through tangible evidence. This requires several sentences with various components. You’ll want to provide more context , going into greater detail to situate the reader within the topic. Next, you’ll provide evidence , often in the form of a quote, facts, or data, and supply a source citation . Citing your source is paramount. Sources indicate that your evidence is empirical and objective. It implies that your evidence is knowledge shared by others in the academic community. Sometimes you’ll want to provide multiple pieces of evidence, if the evidence is similar and can be grouped together.

After providing evidence, you must provide an interpretation and analysis of this evidence. In other words, use rhetorical techniques to paraphrase what your evidence seems to suggest. Break down the evidence further and explain and summarize it in new words. Don’t simply skip to your conclusion. Your evidence should never stand for itself. Why? Because your interpretation and analysis allow you to exhibit original, analytical, and critical thinking skills.

Depending on what evidence you’re using, you may repeat some of these components in the same body paragraph. This might look like: more context + further evidence + increased interpretation and analysis . All this will add up to proving and reaffirming your body paragraph’s main point . To do so, conclude your body paragraph by reformulating your thesis statement in light of the information you’ve given. I recommend comparing your original thesis statement to your paragraph’s concluding statement. Do they align? Does your body paragraph create a sound connection to the overall academic argument? If not, you’ll need to fix this issue when you edit your body paragraph.

How to Edit a Body Paragraph

As you go over each body paragraph of your college essay, keep this short checklist in mind.

- Consistency in your argument: If your key points don’t add up to a cogent argument, you’ll need to identify where the inconsistency lies. Often it lies in interpretation and analysis. You may need to improve the way you articulate this component. Try to think like a lawyer: how can you use this evidence to your advantage? If that doesn’t work, you may need to find new evidence. As a last resort, amend your thesis statement.

- Language-level persuasion. Use a broad vocabulary. Vary your sentence structure. Don’t repeat the same words too often, which can induce mental fatigue in the reader. I suggest keeping an online dictionary open on your browser. I find Merriam-Webster user-friendly, since it allows you to toggle between definitions and synonyms. It also includes up-to-date example sentences. Also, don’t forget the power of rhetorical devices .

- Does your writing flow naturally from one idea to the next, or are there jarring breaks? The editing stage is a great place to polish transitions and reinforce the structure as a whole.

Our first body paragraph example comes from the College Transitions article “ How to Write the AP Lang Argument Essay .” Here’s the prompt: Write an essay that argues your position on the value of striving for perfection.

Here’s the example thesis statement, taken from the introduction paragraph: “Striving for perfection can only lead us to shortchange ourselves. Instead, we should value learning, growth, and creativity and not worry whether we are first or fifth best.” Now let’s see how this writer builds an argument against perfection through one main point across two body paragraphs. (While this writer has split this idea into two paragraphs, one to address a problem and one to provide an alternative resolution, it could easily be combined into one paragraph.)

“Students often feel the need to be perfect in their classes, and this can cause students to struggle or stop making an effort in class. In elementary and middle school, for example, I was very nervous about public speaking. When I had to give a speech, my voice would shake, and I would turn very red. My teachers always told me “relax!” and I got Bs on Cs on my speeches. As a result, I put more pressure on myself to do well, spending extra time making my speeches perfect and rehearsing late at night at home. But this pressure only made me more nervous, and I started getting stomach aches before speaking in public.

“Once I got to high school, however, I started doing YouTube make-up tutorials with a friend. We made videos just for fun, and laughed when we made mistakes or said something silly. Only then, when I wasn’t striving to be perfect, did I get more comfortable with public speaking.”

Body Paragraph Example 1 Dissected

In this body paragraph example, the writer uses their personal experience as evidence against the value of striving for perfection. The writer sets up this example with a topic sentence that acts as a transition from the introduction. They also situate the reader in the classroom. The evidence takes the form of emotion and physical reactions to the pressure of public speaking (nervousness, shaking voice, blushing). Evidence also takes the form of poor results (mediocre grades). Rather than interpret the evidence from an analytical perspective, the writer produces more evidence to underline their point. (This method works fine for a narrative-style essay.) It’s clear that working harder to be perfect further increased the student’s nausea.

The writer proves their point in the second paragraph, through a counter-example. The main point is that improvement comes more naturally when the pressure is lifted; when amusement is possible and mistakes aren’t something to fear. This point ties back in with the thesis, that “we should value learning, growth, and creativity” over perfection.

This second body paragraph example comes from the College Transitions article “ How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay .” Here’s an abridged version of the prompt: Rosa Parks was an African American civil rights activist who was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Read the passage carefully. Write an essay that analyzes the rhetorical choices Obama makes to convey his message.

Here’s the example thesis statement, taken from the introduction paragraph: “Through the use of diction that portrays Parks as quiet and demure, long lists that emphasize the extent of her impacts, and Biblical references, Obama suggests that all of us are capable of achieving greater good, just as Parks did.” Now read the body paragraph example, below.

“To further illustrate Parks’ impact, Obama incorporates Biblical references that emphasize the importance of “that single moment on the bus” (lines 57-58). In lines 33-35, Obama explains that Parks and the other protestors are “driven by a solemn determination to affirm their God-given dignity” and he also compares their victory to the fall the “ancient walls of Jericho” (line 43). By including these Biblical references, Obama suggests that Parks’ action on the bus did more than correct personal or political wrongs; it also corrected moral and spiritual wrongs. Although Parks had no political power or fortune, she was able to restore a moral balance in our world.”

Body Paragraph Example 2 Dissected

The first sentence in this body paragraph example indicates that the topic is transitioning into biblical references as a means of motivating ordinary citizens. The evidence comes as quotes taken from Obama’s speech. One is a reference to God, and the other an allusion to a story from the bible. The subsequent interpretation and analysis demonstrate that Obama’s biblical references imply a deeper, moral and spiritual significance. The concluding sentence draws together the morality inherent in equal rights with Rosa Parks’ power to spark change. Through the words “no political power or fortune,” and “moral balance,” the writer ties the point proven in this body paragraph back to the thesis statement. Obama promises that “All of us” (no matter how small our influence) “are capable of achieving greater good”—a greater moral good.

What’s Next?

Before you body paragraphs come the start and, after your body paragraphs, the conclusion, of course! If you’ve found this article helpful, be sure to read up on how to start a college essay and how to end a college essay .

You may also find the following blogs to be of interest:

- 6 Best Common App Essay Examples

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay

- UC Essay Examples

- How to Write the Community Essay

- How to Write the Why this Major? Essay

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Parent Counselor Educator Other Zip Code Sign Up Now

What is a Body Paragraph? (Definition, Examples, How to Start)

What is a body paragraph? How do I start a body paragraph? A body paragraph is the most important part of the sentence subject . It delivers the most impactful information and helps to transition in and out of paragraphs more effectively.

What is a body paragraph?

Any essay, article, or academic writing starts with an introduction and ends with a conclusion. The text between the introduction and conclusion is the body paragraph.

A body paragraph supports the idea that was mentioned in the introduction by shedding light on new details using facts, statistics, arguments, or other information.

What role does a body paragraph play in an article or an essay?

A body paragraph acts as a connection between the introduction and the conclusion. The body paragraph’s role is to justify the thesis stated in the introduction of an essay or article. As mentioned previously it comes between the introduction and the conclusion which is where most of the writing is done. This signifies its importance.

There can be multiple body paragraphs in an article or an essay. That said, each of the body paragraphs should logically connect with one another. In addition to this, all the body paragraphs should focus on the main idea stated in the introduction. Also, the sentences should not be long, so that readers can easily consume the information.

Here is a brief breakdown of the structure of a body paragraph:

How to structure a body paragraph

Every body paragraph has four main parts. They are:

- Topic Sentence

- Evidence Or Supporting Sentences

- Ending Or Conclusion

Here is a detailed breakdown of each one of them.

Topic sentence

The topic sentence is the first sentence in a body paragraph. This sentence discusses the main idea of the topic and indicates what information to expect in the rest of the paragraph. It sets the stage for the rest of the paragraph.

Evidence or supporting sentences

After the topic sentence comes the supporting sentences. These sentences are used to justify the claim that was stated in the topic sentence. Text citations, evidence, statistics, and examples are used to justify the claim. For example, if the topic sentence discusses “Switzerland is a must visit place”, then the supporting sentences should discuss the beautiful parts of Switzerland with examples to justify the claim.

One sentence to another sentence should flow seamlessly and this is possible by using transition words . Transition words like “however”, “although”, “in addition to”, “next”, and “in contrast” helps in doing exactly the same.

Ending or concluding sentence

Every body paragraph should end with a conclusion which comes after the supporting sentences. It summarizes the main idea of the body paragraph and emphasizes the supporting details. The conclusion gives way to the next line of the next paragraph.

Transitions are a few words that help in the smooth flow of the previous paragraph to the next paragraph. These words can be at the beginning of topic sentences or at the end of the body paragraph. They connect one idea of a paragraph to the next idea of another paragraph.

How to write an effective body paragraph

Keep the body paragraph’s focus on the topic.

All the body paragraphs should support the claim made in the introduction of an essay or an article. It should be consistent with the main idea of the topic. It is recommended to avoid adding unnecessary information in the body paragraph that doesn’t relate to the main idea of the topic.

Break complicated topic sentences into smaller parts

If the topic sentence has many parts to it, the topic sentence should be divided into smaller ideas and each idea should be expressed in a different body paragraph. Having too many parts in a topic sentence will lead to many support sentences in the body paragraph which will be too lengthy for readers to grasp.

Add counterarguments

If it is an academic essay or an opinion article, counterarguments should be included in the piece. Adding counterarguments in such pieces will give a broader perspective of the piece. Such inclusions will strengthen the essay or article.

Use signals when more than one paragraph deals with the same evidence

If multiple body paragraphs deal with the same evidence, there are a few signal phrases that will help the reader connect with evidence used earlier in other paragraphs. The signal phrases like “As mentioned previously” and “As already mentioned” can be used.

Include paragraph breaks

It is a single-line space that divides one paragraph from another. This is necessary because too long paragraphs make it difficult for readers to grasp the information. A space between paragraphs will help the readers to easily wade through the text. A paragraph break also signals the transition of one idea of one body paragraph to an idea of another body paragraph.

The body paragraph should be short

The body paragraph should be short and concise . The paragraphs should not exceed one page. Paragraphs exceeding a page will make the article or essay complicated to comprehend the information.

Body paragraphs should be proofread

After writing the body paragraph, proofreading is done. This will help in finding and fixing mistakes. It will also help in removing unnecessary sentences in the body paragraph. The ideal way to proofread is by reading the body paragraph loudly. Doing so will help in identifying awkward word placements in the sentence.

In addition to this, asking questions like “is the body paragraph sticking to the main idea of the topic?” should be exercised. It will give a sense that if the paragraph is heading in the right direction or not.

How to start a body paragraph

The first sentence in a body paragraph is the topic sentence and it is the hardest sentence to write. The topic sentence sets the stage for the rest of the sentences in the paragraph.

Once the reader reads the topic sentence, the reader should get a sense that what the rest of the paragraph will be.

So, it should be concise and to the point, revealing enough information that will help the reader to know what the paragraph will be all about.

How to conclude a body paragraph

At the end of the body paragraph, the sentence should summarize the claim stated in the topic sentence and should also include a brief explanation of the supporting sentences. It should be written in such a way that the sentence is concise and at the same time reveals the main points.

This sentence will help the reader to get a gist of what the paragraph is all about.

Difference between body paragraph and introduction

Though both of them are paragraphs, they are very different. Firstly, the structure of an introduction is constructed differently than the body paragraph. An introduction consists of a thesis statement and a brief explanation. On the other hand, the body paragraph consists of a topic sentence, supporting sentences, and a conclusion.

Secondly, the introduction comes first in an essay or an article. In comparison, the body paragraph comes after the introduction. It comes after the introduction and before the conclusion of an essay or article.

A typical body paragraph should contain at least six sentences.

To develop a well-structured paragraph:

- Construct a topic sentence.

- Include evidence to support the claim expressed in the topic sentence.

- Add analysis to the paragraph.

- End it with a conclusion summarizing the key points of the paragraph.

- Finally, proofread the paragraph to identify and fix mistakes.

An introduction is the first paragraph of an essay or article. It gets the reader’s attention regarding the topic and provides the thesis statement of the topic. To write a good introduction:

- Keep the introduction paragraph short.

- In one to two sentences explain the thesis statement of the article or essay.

There is no fixed number of words that a body paragraph should have. That said, typically a paragraph contains about a hundred to two hundred words which are six to seven sentences.

Yes, an essay or article can have more than one body paragraph. Some essays have three to four body paragraphs. That said, having two of these is enough to cover important points of the essay.

A conclusion comes after the body paragraph at the end of the essay. A long essay can have two or three paragraphs to conclude. It summarizes the main idea of the topic.

- Body Paragraphs: How to Write Perfect Ones | Grammarly blog

- Body Paragraph Example & Structure

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph

- How to Write a Body Paragraph | BestColleges

Inside this article

Fact checked: Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

About the author

Dalia Y.: Dalia is an English Major and linguistics expert with an additional degree in Psychology. Dalia has featured articles on Forbes, Inc, Fast Company, Grammarly, and many more. She covers English, ESL, and all things grammar on GrammarBrain.

Core lessons

- Abstract Noun

- Accusative Case

- Active Sentence

- Alliteration

- Adjective Clause

- Adjective Phrase

- Adverbial Clause

- Appositive Phrase

- Body Paragraph

- Compound Adjective

- Complex Sentence

- Compound Words

- Compound Predicate

- Common Noun

- Comparative Adjective

- Comparative and Superlative

- Compound Noun

- Compound Subject

- Compound Sentence

- Copular Verb

- Collective Noun

- Colloquialism

- Conciseness

- Conditional

- Concrete Noun

- Conjunction

- Conjugation

- Conditional Sentence

- Comma Splice

- Correlative Conjunction

- Coordinating Conjunction

- Coordinate Adjective

- Cumulative Adjective

- Dative Case

- Declarative Statement

- Direct Object Pronoun

- Direct Object

- Dangling Modifier

- Demonstrative Pronoun

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Direct Characterization

- Definite Article

- Doublespeak

- Equivocation Fallacy

- Future Perfect Progressive

- Future Simple

- Future Perfect Continuous

- Future Perfect

- First Conditional

- Gerund Phrase

- Genitive Case

- Helping Verb

- Irregular Adjective

- Irregular Verb

- Imperative Sentence

- Indefinite Article

- Intransitive Verb

- Introductory Phrase

- Indefinite Pronoun

- Indirect Characterization

- Interrogative Sentence

- Intensive Pronoun

- Inanimate Object

- Indefinite Tense

- Infinitive Phrase

- Interjection

- Intensifier

- Indicative Mood

- Juxtaposition

- Linking Verb

- Misplaced Modifier

- Nominative Case

- Noun Adjective

- Object Pronoun

- Object Complement

- Order of Adjectives

- Parallelism

- Prepositional Phrase

- Past Simple Tense

- Past Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense

- Present Simple Tense

- Present Perfect Tense

- Personal Pronoun

- Personification

- Persuasive Writing

- Parallel Structure

- Phrasal Verb

- Predicate Adjective

- Predicate Nominative

- Phonetic Language

- Plural Noun

- Punctuation

- Punctuation Marks

- Preposition

- Preposition of Place

- Parts of Speech

- Possessive Adjective

- Possessive Determiner

- Possessive Case

- Possessive Noun

- Proper Adjective

- Proper Noun

- Present Participle

- Quotation Marks

- Relative Pronoun

- Reflexive Pronoun

- Reciprocal Pronoun

- Subordinating Conjunction

- Simple Future Tense

- Stative Verb

- Subjunctive

- Subject Complement

- Subject of a Sentence

- Sentence Variety

- Second Conditional

- Superlative Adjective

- Slash Symbol

- Types of Nouns

- Types of Sentences

- Uncountable Noun

- Vowels and Consonants

Popular lessons

Stay awhile. Your weekly dose of grammar and English fun.

The world's best online resource for learning English. Understand words, phrases, slang terms, and all other variations of the English language.

- Abbreviations

- Editorial Policy

How to write an essay: Body

- What's in this guide

- Introduction

- Essay structure

- Additional resources

Body paragraphs

The essay body itself is organised into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly.

Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence . This lets the reader know what the paragraph is going to be about and the main point it will make. It gives the paragraph’s point straight away. Next – and largest – is the supporting sentences . These expand on the central idea, explaining it in more detail, exploring what it means, and of course giving the evidence and argument that back it up. This is where you use your research to support your argument. Then there is a concluding sentence . This restates the idea in the topic sentence, to remind the reader of your main point. It also shows how that point helps answer the question.

Pathways and Academic Learning Support

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 1:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-an-essay

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.2 Writing Body Paragraphs

Learning objectives.

- Select primary support related to your thesis.

- Support your topic sentences.

If your thesis gives the reader a roadmap to your essay, then body paragraphs should closely follow that map. The reader should be able to predict what follows your introductory paragraph by simply reading the thesis statement.

The body paragraphs present the evidence you have gathered to confirm your thesis. Before you begin to support your thesis in the body, you must find information from a variety of sources that support and give credit to what you are trying to prove.

Select Primary Support for Your Thesis

Without primary support, your argument is not likely to be convincing. Primary support can be described as the major points you choose to expand on your thesis. It is the most important information you select to argue for your point of view. Each point you choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph you write. Your primary supporting points are further supported by supporting details within the paragraphs.

Remember that a worthy argument is backed by examples. In order to construct a valid argument, good writers conduct lots of background research and take careful notes. They also talk to people knowledgeable about a topic in order to understand its implications before writing about it.

Identify the Characteristics of Good Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of good primary support, the information you choose must meet the following standards:

- Be specific. The main points you make about your thesis and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be specific. Use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon your general ideas. These types of examples give your reader something narrow to focus on, and if used properly, they leave little doubt about your claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical.

- Be relevant to the thesis. Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove your main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all in your body paragraphs. But effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Choose your examples wisely by making sure they directly connect to your thesis.

- Be detailed. Remember that your thesis, while specific, should not be very detailed. The body paragraphs are where you develop the discussion that a thorough essay requires. Using detailed support shows readers that you have considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance your point of view.

Prewrite to Identify Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

Recall that when you prewrite you essentially make a list of examples or reasons why you support your stance. Stemming from each point, you further provide details to support those reasons. After prewriting, you are then able to look back at the information and choose the most compelling pieces you will use in your body paragraphs.

Choose one of the following working thesis statements. On a separate sheet of paper, write for at least five minutes using one of the prewriting techniques you learned in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

- Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

- Students cheat for many different reasons.

- Drug use among teens and young adults is a problem.

- The most important change that should occur at my college or university is ____________________________________________.

Select the Most Effective Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

After you have prewritten about your working thesis statement, you may have generated a lot of information, which may be edited out later. Remember that your primary support must be relevant to your thesis. Remind yourself of your main argument, and delete any ideas that do not directly relate to it. Omitting unrelated ideas ensures that you will use only the most convincing information in your body paragraphs. Choose at least three of only the most compelling points. These will serve as the topic sentences for your body paragraphs.

Refer to the previous exercise and select three of your most compelling reasons to support the thesis statement. Remember that the points you choose must be specific and relevant to the thesis. The statements you choose will be your primary support points, and you will later incorporate them into the topic sentences for the body paragraphs.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

When you support your thesis, you are revealing evidence. Evidence includes anything that can help support your stance. The following are the kinds of evidence you will encounter as you conduct your research:

- Facts. Facts are the best kind of evidence to use because they often cannot be disputed. They can support your stance by providing background information on or a solid foundation for your point of view. However, some facts may still need explanation. For example, the sentence “The most populated state in the United States is California” is a pure fact, but it may require some explanation to make it relevant to your specific argument.

- Judgments. Judgments are conclusions drawn from the given facts. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and examination of a topic.

- Testimony. Testimony consists of direct quotations from either an eyewitness or an expert witness. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; he adds authenticity to an argument based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive experience with a topic. This person studies the facts and provides commentary based on either facts or judgments, or both. An expert witness adds authority and credibility to an argument.

- Personal observation. Personal observation is similar to testimony, but personal observation consists of your testimony. It reflects what you know to be true because you have experiences and have formed either opinions or judgments about them. For instance, if you are one of five children and your thesis states that being part of a large family is beneficial to a child’s social development, you could use your own experience to support your thesis.

Writing at Work

In any job where you devise a plan, you will need to support the steps that you lay out. This is an area in which you would incorporate primary support into your writing. Choosing only the most specific and relevant information to expand upon the steps will ensure that your plan appears well-thought-out and precise.

You can consult a vast pool of resources to gather support for your stance. Citing relevant information from reliable sources ensures that your reader will take you seriously and consider your assertions. Use any of the following sources for your essay: newspapers or news organization websites, magazines, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, which are periodicals that address topics in a specialized field.

Choose Supporting Topic Sentences

Each body paragraph contains a topic sentence that states one aspect of your thesis and then expands upon it. Like the thesis statement, each topic sentence should be specific and supported by concrete details, facts, or explanations.

Each body paragraph should comprise the following elements.

topic sentence + supporting details (examples, reasons, or arguments)

As you read in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , topic sentences indicate the location and main points of the basic arguments of your essay. These sentences are vital to writing your body paragraphs because they always refer back to and support your thesis statement. Topic sentences are linked to the ideas you have introduced in your thesis, thus reminding readers what your essay is about. A paragraph without a clearly identified topic sentence may be unclear and scattered, just like an essay without a thesis statement.

Unless your teacher instructs otherwise, you should include at least three body paragraphs in your essay. A five-paragraph essay, including the introduction and conclusion, is commonly the standard for exams and essay assignments.

Consider the following the thesis statement:

Author J.D. Salinger relied primarily on his personal life and belief system as the foundation for the themes in the majority of his works.

The following topic sentence is a primary support point for the thesis. The topic sentence states exactly what the controlling idea of the paragraph is. Later, you will see the writer immediately provide support for the sentence.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced themes in many of his works.

In Note 9.19 “Exercise 2” , you chose three of your most convincing points to support the thesis statement you selected from the list. Take each point and incorporate it into a topic sentence for each body paragraph.

Supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Topic sentence: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

Draft Supporting Detail Sentences for Each Primary Support Sentence

After deciding which primary support points you will use as your topic sentences, you must add details to clarify and demonstrate each of those points. These supporting details provide examples, facts, or evidence that support the topic sentence.

The writer drafts possible supporting detail sentences for each primary support sentence based on the thesis statement:

Thesis statement: Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

Supporting point 1: Dogs can scare cyclists and pedestrians.

Supporting details:

- Cyclists are forced to zigzag on the road.

- School children panic and turn wildly on their bikes.

- People who are walking at night freeze in fear.

Supporting point 2:

Loose dogs are traffic hazards.

- Dogs in the street make people swerve their cars.

- To avoid dogs, drivers run into other cars or pedestrians.

- Children coaxing dogs across busy streets create danger.

Supporting point 3: Unleashed dogs damage gardens.

- They step on flowers and vegetables.

- They destroy hedges by urinating on them.

- They mess up lawns by digging holes.

The following paragraph contains supporting detail sentences for the primary support sentence (the topic sentence), which is underlined.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced the themes in many of his works. He did not hide his mental anguish over the horrors of war and once told his daughter, “You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose, no matter how long you live.” His short story “A Perfect Day for a Bananafish” details a day in the life of a WWII veteran who was recently released from an army hospital for psychiatric problems. The man acts questionably with a little girl he meets on the beach before he returns to his hotel room and commits suicide. Another short story, “For Esmé – with Love and Squalor,” is narrated by a traumatized soldier who sparks an unusual relationship with a young girl he meets before he departs to partake in D-Day. Finally, in Salinger’s only novel, The Catcher in the Rye , he continues with the theme of posttraumatic stress, though not directly related to war. From a rest home for the mentally ill, sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield narrates the story of his nervous breakdown following the death of his younger brother.

Using the three topic sentences you composed for the thesis statement in Note 9.18 “Exercise 1” , draft at least three supporting details for each point.

Thesis statement: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Supporting details: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

You have the option of writing your topic sentences in one of three ways. You can state it at the beginning of the body paragraph, or at the end of the paragraph, or you do not have to write it at all. This is called an implied topic sentence. An implied topic sentence lets readers form the main idea for themselves. For beginning writers, it is best to not use implied topic sentences because it makes it harder to focus your writing. Your instructor may also want to clearly identify the sentences that support your thesis. For more information on the placement of thesis statements and implied topic statements, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Print out the first draft of your essay and use a highlighter to mark your topic sentences in the body paragraphs. Make sure they are clearly stated and accurately present your paragraphs, as well as accurately reflect your thesis. If your topic sentence contains information that does not exist in the rest of the paragraph, rewrite it to more accurately match the rest of the paragraph.

Key Takeaways

- Your body paragraphs should closely follow the path set forth by your thesis statement.

- Strong body paragraphs contain evidence that supports your thesis.

- Primary support comprises the most important points you use to support your thesis.

- Strong primary support is specific, detailed, and relevant to the thesis.

- Prewriting helps you determine your most compelling primary support.

- Evidence includes facts, judgments, testimony, and personal observation.

- Reliable sources may include newspapers, magazines, academic journals, books, encyclopedias, and firsthand testimony.

- A topic sentence presents one point of your thesis statement while the information in the rest of the paragraph supports that point.

- A body paragraph comprises a topic sentence plus supporting details.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates

Published on September 18, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The basic structure of an essay always consists of an introduction , a body , and a conclusion . But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

The basics of essay structure, chronological structure, compare-and-contrast structure, problems-methods-solutions structure, signposting to clarify your structure, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay structure.

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you’ll organize the information within the body.

Parts of an essay

The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below.

Order of information

You’ll also have to consider how to present information within the body. There are a few general principles that can guide you here.

The first is that your argument should move from the simplest claim to the most complex . The body of a good argumentative essay often begins with simple and widely accepted claims, and then moves towards more complex and contentious ones.

For example, you might begin by describing a generally accepted philosophical concept, and then apply it to a new topic. The grounding in the general concept will allow the reader to understand your unique application of it.

The second principle is that background information should appear towards the beginning of your essay . General background is presented in the introduction. If you have additional background to present, this information will usually come at the start of the body.

The third principle is that everything in your essay should be relevant to the thesis . Ask yourself whether each piece of information advances your argument or provides necessary background. And make sure that the text clearly expresses each piece of information’s relevance.

The sections below present several organizational templates for essays: the chronological approach, the compare-and-contrast approach, and the problems-methods-solutions approach.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The chronological approach (sometimes called the cause-and-effect approach) is probably the simplest way to structure an essay. It just means discussing events in the order in which they occurred, discussing how they are related (i.e. the cause and effect involved) as you go.