- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

How to write a thesis statement, what is a thesis statement.

Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement.

Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement?

- to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two

- to better organize and develop your argument

- to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument

In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores.

How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement?

Here are some helpful hints to get you started. You can either scroll down or select a link to a specific topic.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned

Almost all assignments, no matter how complicated, can be reduced to a single question. Your first step, then, is to distill the assignment into a specific question. For example, if your assignment is, “Write a report to the local school board explaining the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class,” turn the request into a question like, “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” After you’ve chosen the question your essay will answer, compose one or two complete sentences answering that question.

Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” A: “The potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class are . . .”

A: “Using computers in a fourth-grade class promises to improve . . .”

The answer to the question is the thesis statement for the essay.

[ Back to top ]

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned

Even if your assignment doesn’t ask a specific question, your thesis statement still needs to answer a question about the issue you’d like to explore. In this situation, your job is to figure out what question you’d like to write about.

A good thesis statement will usually include the following four attributes:

- take on a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree

- deal with a subject that can be adequately treated given the nature of the assignment

- express one main idea

- assert your conclusions about a subject

Let’s see how to generate a thesis statement for a social policy paper.

Brainstorm the topic . Let’s say that your class focuses upon the problems posed by changes in the dietary habits of Americans. You find that you are interested in the amount of sugar Americans consume.

You start out with a thesis statement like this:

Sugar consumption.

This fragment isn’t a thesis statement. Instead, it simply indicates a general subject. Furthermore, your reader doesn’t know what you want to say about sugar consumption.

Narrow the topic . Your readings about the topic, however, have led you to the conclusion that elementary school children are consuming far more sugar than is healthy.

You change your thesis to look like this:

Reducing sugar consumption by elementary school children.

This fragment not only announces your subject, but it focuses on one segment of the population: elementary school children. Furthermore, it raises a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree, because while most people might agree that children consume more sugar than they used to, not everyone would agree on what should be done or who should do it. You should note that this fragment is not a thesis statement because your reader doesn’t know your conclusions on the topic.

Take a position on the topic. After reflecting on the topic a little while longer, you decide that what you really want to say about this topic is that something should be done to reduce the amount of sugar these children consume.

You revise your thesis statement to look like this:

More attention should be paid to the food and beverage choices available to elementary school children.

This statement asserts your position, but the terms more attention and food and beverage choices are vague.

Use specific language . You decide to explain what you mean about food and beverage choices , so you write:

Experts estimate that half of elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar.

This statement is specific, but it isn’t a thesis. It merely reports a statistic instead of making an assertion.

Make an assertion based on clearly stated support. You finally revise your thesis statement one more time to look like this:

Because half of all American elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar, schools should be required to replace the beverages in soda machines with healthy alternatives.

Notice how the thesis answers the question, “What should be done to reduce sugar consumption by children, and who should do it?” When you started thinking about the paper, you may not have had a specific question in mind, but as you became more involved in the topic, your ideas became more specific. Your thesis changed to reflect your new insights.

How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

1. a strong thesis statement takes some sort of stand..

Remember that your thesis needs to show your conclusions about a subject. For example, if you are writing a paper for a class on fitness, you might be asked to choose a popular weight-loss product to evaluate. Here are two thesis statements:

There are some negative and positive aspects to the Banana Herb Tea Supplement.

This is a weak thesis statement. First, it fails to take a stand. Second, the phrase negative and positive aspects is vague.

Because Banana Herb Tea Supplement promotes rapid weight loss that results in the loss of muscle and lean body mass, it poses a potential danger to customers.

This is a strong thesis because it takes a stand, and because it's specific.

2. A strong thesis statement justifies discussion.

Your thesis should indicate the point of the discussion. If your assignment is to write a paper on kinship systems, using your own family as an example, you might come up with either of these two thesis statements:

My family is an extended family.

This is a weak thesis because it merely states an observation. Your reader won’t be able to tell the point of the statement, and will probably stop reading.

While most American families would view consanguineal marriage as a threat to the nuclear family structure, many Iranian families, like my own, believe that these marriages help reinforce kinship ties in an extended family.

This is a strong thesis because it shows how your experience contradicts a widely-accepted view. A good strategy for creating a strong thesis is to show that the topic is controversial. Readers will be interested in reading the rest of the essay to see how you support your point.

3. A strong thesis statement expresses one main idea.

Readers need to be able to see that your paper has one main point. If your thesis statement expresses more than one idea, then you might confuse your readers about the subject of your paper. For example:

Companies need to exploit the marketing potential of the Internet, and Web pages can provide both advertising and customer support.

This is a weak thesis statement because the reader can’t decide whether the paper is about marketing on the Internet or Web pages. To revise the thesis, the relationship between the two ideas needs to become more clear. One way to revise the thesis would be to write:

Because the Internet is filled with tremendous marketing potential, companies should exploit this potential by using Web pages that offer both advertising and customer support.

This is a strong thesis because it shows that the two ideas are related. Hint: a great many clear and engaging thesis statements contain words like because , since , so , although , unless , and however .

4. A strong thesis statement is specific.

A thesis statement should show exactly what your paper will be about, and will help you keep your paper to a manageable topic. For example, if you're writing a seven-to-ten page paper on hunger, you might say:

World hunger has many causes and effects.

This is a weak thesis statement for two major reasons. First, world hunger can’t be discussed thoroughly in seven to ten pages. Second, many causes and effects is vague. You should be able to identify specific causes and effects. A revised thesis might look like this:

Hunger persists in Glandelinia because jobs are scarce and farming in the infertile soil is rarely profitable.

This is a strong thesis statement because it narrows the subject to a more specific and manageable topic, and it also identifies the specific causes for the existence of hunger.

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

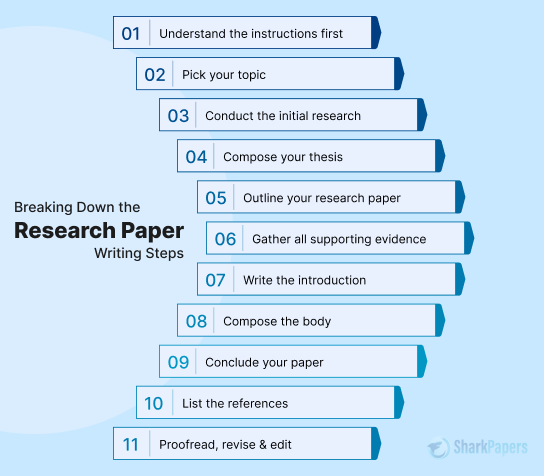

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

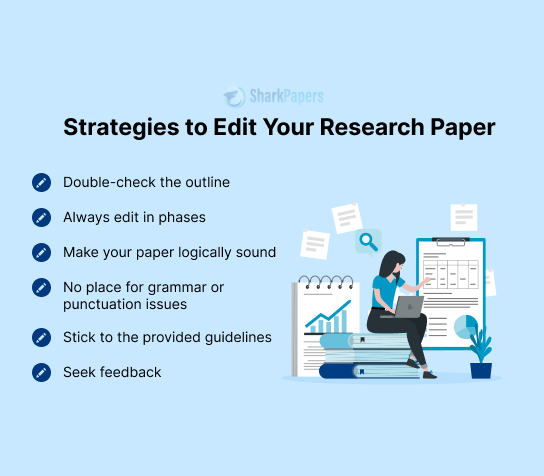

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

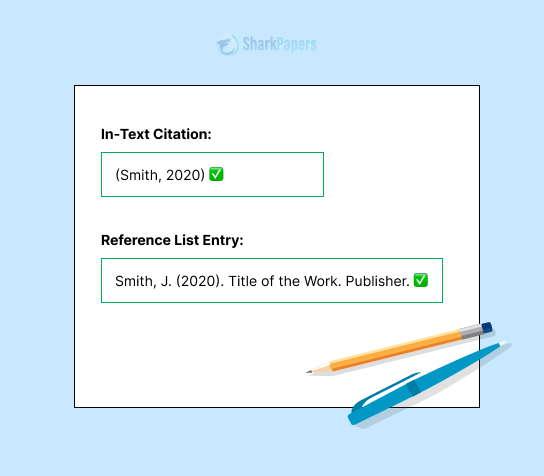

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

The important sentence expresses your central assertion or argument

arabianEye / Getty Images

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A thesis statement provides the foundation for your entire research paper or essay. This statement is the central assertion that you want to express in your essay. A successful thesis statement is one that is made up of one or two sentences clearly laying out your central idea and expressing an informed, reasoned answer to your research question.

Usually, the thesis statement will appear at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. There are a few different types, and the content of your thesis statement will depend upon the type of paper you’re writing.

Key Takeaways: Writing a Thesis Statement

- A thesis statement gives your reader a preview of your paper's content by laying out your central idea and expressing an informed, reasoned answer to your research question.

- Thesis statements will vary depending on the type of paper you are writing, such as an expository essay, argument paper, or analytical essay.

- Before creating a thesis statement, determine whether you are defending a stance, giving an overview of an event, object, or process, or analyzing your subject

Expository Essay Thesis Statement Examples

An expository essay "exposes" the reader to a new topic; it informs the reader with details, descriptions, or explanations of a subject. If you are writing an expository essay , your thesis statement should explain to the reader what she will learn in your essay. For example:

- The United States spends more money on its military budget than all the industrialized nations combined.

- Gun-related homicides and suicides are increasing after years of decline.

- Hate crimes have increased three years in a row, according to the FBI.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increases the risk of stroke and arterial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat).

These statements provide a statement of fact about the topic (not just opinion) but leave the door open for you to elaborate with plenty of details. In an expository essay, you don't need to develop an argument or prove anything; you only need to understand your topic and present it in a logical manner. A good thesis statement in an expository essay always leaves the reader wanting more details.

Types of Thesis Statements

Before creating a thesis statement, it's important to ask a few basic questions, which will help you determine the kind of essay or paper you plan to create:

- Are you defending a stance in a controversial essay ?

- Are you simply giving an overview or describing an event, object, or process?

- Are you conducting an analysis of an event, object, or process?

In every thesis statement , you will give the reader a preview of your paper's content, but the message will differ a little depending on the essay type .

Argument Thesis Statement Examples

If you have been instructed to take a stance on one side of a controversial issue, you will need to write an argument essay . Your thesis statement should express the stance you are taking and may give the reader a preview or a hint of your evidence. The thesis of an argument essay could look something like the following:

- Self-driving cars are too dangerous and should be banned from the roadways.

- The exploration of outer space is a waste of money; instead, funds should go toward solving issues on Earth, such as poverty, hunger, global warming, and traffic congestion.

- The U.S. must crack down on illegal immigration.

- Street cameras and street-view maps have led to a total loss of privacy in the United States and elsewhere.

These thesis statements are effective because they offer opinions that can be supported by evidence. If you are writing an argument essay, you can craft your own thesis around the structure of the statements above.

Analytical Essay Thesis Statement Examples

In an analytical essay assignment, you will be expected to break down a topic, process, or object in order to observe and analyze your subject piece by piece. Examples of a thesis statement for an analytical essay include:

- The criminal justice reform bill passed by the U.S. Senate in late 2018 (" The First Step Act ") aims to reduce prison sentences that disproportionately fall on nonwhite criminal defendants.

- The rise in populism and nationalism in the U.S. and European democracies has coincided with the decline of moderate and centrist parties that have dominated since WWII.

- Later-start school days increase student success for a variety of reasons.

Because the role of the thesis statement is to state the central message of your entire paper, it is important to revisit (and maybe rewrite) your thesis statement after the paper is written. In fact, it is quite normal for your message to change as you construct your paper.

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- What Is Expository Writing?

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- How To Write an Essay

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- How to Write a Response Paper

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- Understanding What an Expository Essay Is

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

- Tips for Writing an Art History Paper

- How to Write a Persuasive Essay

- The Five Steps of Writing an Essay

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Developing Strong Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

These OWL resources will help you develop and refine the arguments in your writing.

The thesis statement or main claim must be debatable

An argumentative or persuasive piece of writing must begin with a debatable thesis or claim. In other words, the thesis must be something that people could reasonably have differing opinions on. If your thesis is something that is generally agreed upon or accepted as fact then there is no reason to try to persuade people.

Example of a non-debatable thesis statement:

This thesis statement is not debatable. First, the word pollution implies that something is bad or negative in some way. Furthermore, all studies agree that pollution is a problem; they simply disagree on the impact it will have or the scope of the problem. No one could reasonably argue that pollution is unambiguously good.

Example of a debatable thesis statement:

This is an example of a debatable thesis because reasonable people could disagree with it. Some people might think that this is how we should spend the nation's money. Others might feel that we should be spending more money on education. Still others could argue that corporations, not the government, should be paying to limit pollution.

Another example of a debatable thesis statement:

In this example there is also room for disagreement between rational individuals. Some citizens might think focusing on recycling programs rather than private automobiles is the most effective strategy.

The thesis needs to be narrow

Although the scope of your paper might seem overwhelming at the start, generally the narrower the thesis the more effective your argument will be. Your thesis or claim must be supported by evidence. The broader your claim is, the more evidence you will need to convince readers that your position is right.

Example of a thesis that is too broad:

There are several reasons this statement is too broad to argue. First, what is included in the category "drugs"? Is the author talking about illegal drug use, recreational drug use (which might include alcohol and cigarettes), or all uses of medication in general? Second, in what ways are drugs detrimental? Is drug use causing deaths (and is the author equating deaths from overdoses and deaths from drug related violence)? Is drug use changing the moral climate or causing the economy to decline? Finally, what does the author mean by "society"? Is the author referring only to America or to the global population? Does the author make any distinction between the effects on children and adults? There are just too many questions that the claim leaves open. The author could not cover all of the topics listed above, yet the generality of the claim leaves all of these possibilities open to debate.

Example of a narrow or focused thesis:

In this example the topic of drugs has been narrowed down to illegal drugs and the detriment has been narrowed down to gang violence. This is a much more manageable topic.

We could narrow each debatable thesis from the previous examples in the following way:

Narrowed debatable thesis 1:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just the amount of money used but also how the money could actually help to control pollution.

Narrowed debatable thesis 2:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just what the focus of a national anti-pollution campaign should be but also why this is the appropriate focus.

Qualifiers such as " typically ," " generally ," " usually ," or " on average " also help to limit the scope of your claim by allowing for the almost inevitable exception to the rule.

Types of claims

Claims typically fall into one of four categories. Thinking about how you want to approach your topic, or, in other words, what type of claim you want to make, is one way to focus your thesis on one particular aspect of your broader topic.

Claims of fact or definition: These claims argue about what the definition of something is or whether something is a settled fact. Example:

Claims of cause and effect: These claims argue that one person, thing, or event caused another thing or event to occur. Example:

Claims about value: These are claims made of what something is worth, whether we value it or not, how we would rate or categorize something. Example:

Claims about solutions or policies: These are claims that argue for or against a certain solution or policy approach to a problem. Example:

Which type of claim is right for your argument? Which type of thesis or claim you use for your argument will depend on your position and knowledge of the topic, your audience, and the context of your paper. You might want to think about where you imagine your audience to be on this topic and pinpoint where you think the biggest difference in viewpoints might be. Even if you start with one type of claim you probably will be using several within the paper. Regardless of the type of claim you choose to utilize it is key to identify the controversy or debate you are addressing and to define your position early on in the paper.

Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

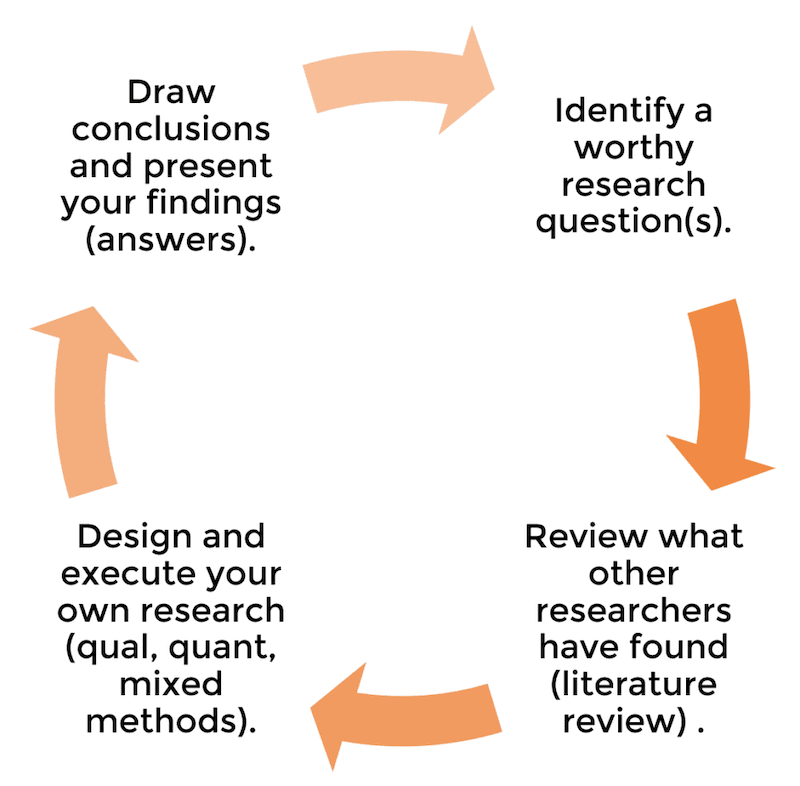

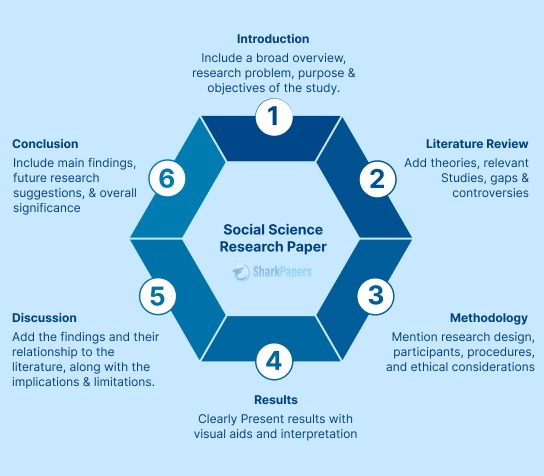

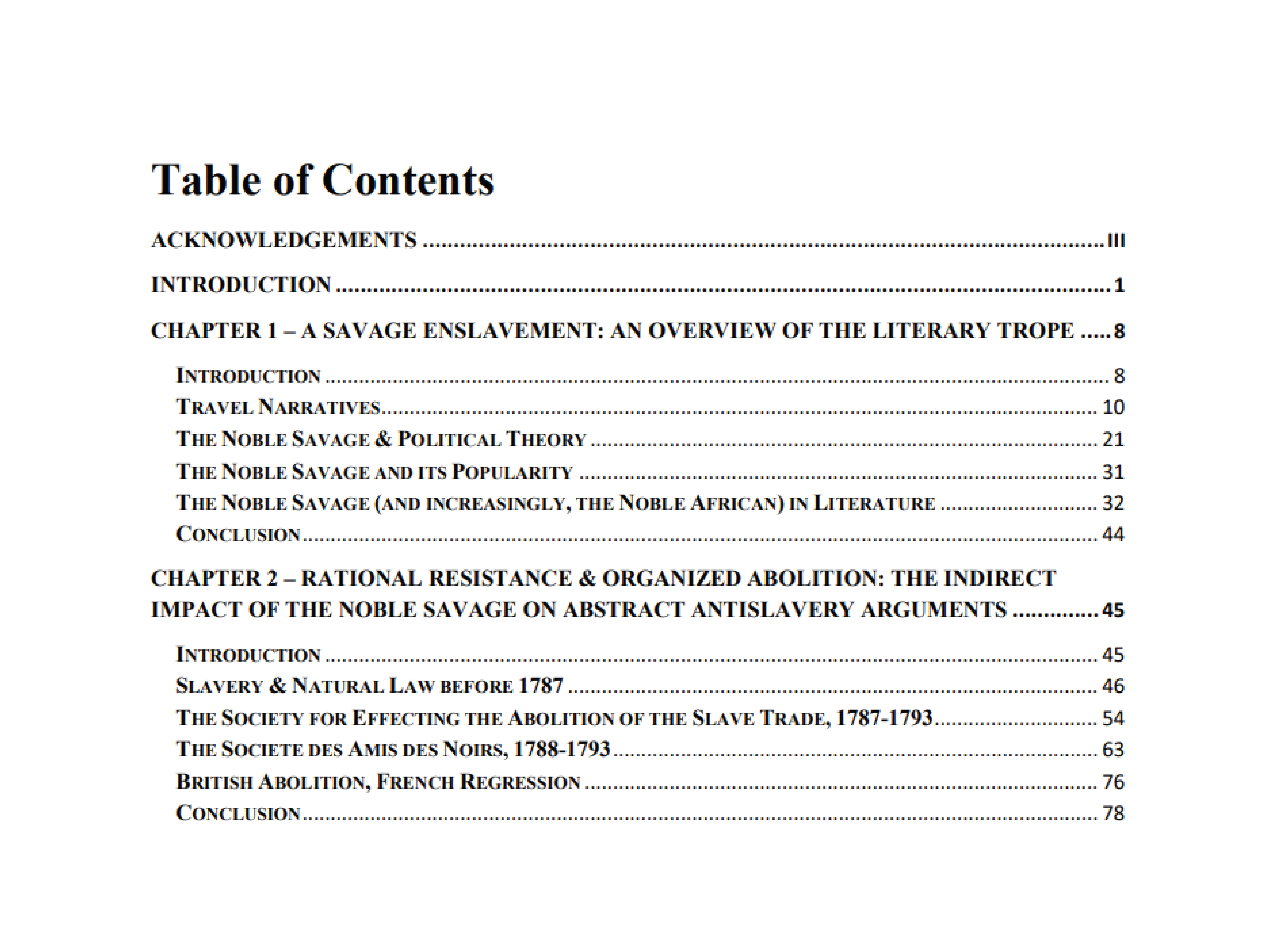

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to write this section up last , once all your core chapters are complete. Otherwise, you’ll end up writing and rewriting this section multiple times (just wasting time). For a step by step guide on how to write a strong executive summary, check out this post .

Need a helping hand?

Table of contents

This section is straightforward. You’ll typically present your table of contents (TOC) first, followed by the two lists – figures and tables. I recommend that you use Microsoft Word’s automatic table of contents generator to generate your TOC. If you’re not familiar with this functionality, the video below explains it simply:

If you find that your table of contents is overly lengthy, consider removing one level of depth. Oftentimes, this can be done without detracting from the usefulness of the TOC.

Right, now that the “admin” sections are out of the way, its time to move on to your core chapters. These chapters are the heart of your dissertation and are where you’ll earn the marks. The first chapter is the introduction chapter – as you would expect, this is the time to introduce your research…

It’s important to understand that even though you’ve provided an overview of your research in your abstract, your introduction needs to be written as if the reader has not read that (remember, the abstract is essentially a standalone document). So, your introduction chapter needs to start from the very beginning, and should address the following questions:

- What will you be investigating (in plain-language, big picture-level)?

- Why is that worth investigating? How is it important to academia or business? How is it sufficiently original?

- What are your research aims and research question(s)? Note that the research questions can sometimes be presented at the end of the literature review (next chapter).

- What is the scope of your study? In other words, what will and won’t you cover ?

- How will you approach your research? In other words, what methodology will you adopt?

- How will you structure your dissertation? What are the core chapters and what will you do in each of them?

These are just the bare basic requirements for your intro chapter. Some universities will want additional bells and whistles in the intro chapter, so be sure to carefully read your brief or consult your research supervisor.

If done right, your introduction chapter will set a clear direction for the rest of your dissertation. Specifically, it will make it clear to the reader (and marker) exactly what you’ll be investigating, why that’s important, and how you’ll be going about the investigation. Conversely, if your introduction chapter leaves a first-time reader wondering what exactly you’ll be researching, you’ve still got some work to do.

Now that you’ve set a clear direction with your introduction chapter, the next step is the literature review . In this section, you will analyse the existing research (typically academic journal articles and high-quality industry publications), with a view to understanding the following questions:

- What does the literature currently say about the topic you’re investigating?

- Is the literature lacking or well established? Is it divided or in disagreement?

- How does your research fit into the bigger picture?

- How does your research contribute something original?

- How does the methodology of previous studies help you develop your own?

Depending on the nature of your study, you may also present a conceptual framework towards the end of your literature review, which you will then test in your actual research.

Again, some universities will want you to focus on some of these areas more than others, some will have additional or fewer requirements, and so on. Therefore, as always, its important to review your brief and/or discuss with your supervisor, so that you know exactly what’s expected of your literature review chapter.

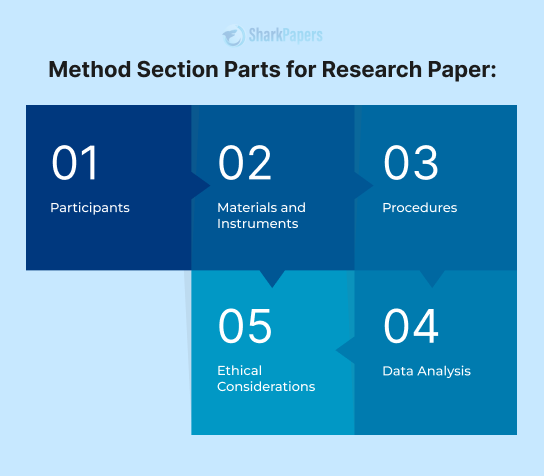

Now that you’ve investigated the current state of knowledge in your literature review chapter and are familiar with the existing key theories, models and frameworks, its time to design your own research. Enter the methodology chapter – the most “science-ey” of the chapters…

In this chapter, you need to address two critical questions:

- Exactly HOW will you carry out your research (i.e. what is your intended research design)?

- Exactly WHY have you chosen to do things this way (i.e. how do you justify your design)?

Remember, the dissertation part of your degree is first and foremost about developing and demonstrating research skills . Therefore, the markers want to see that you know which methods to use, can clearly articulate why you’ve chosen then, and know how to deploy them effectively.

Importantly, this chapter requires detail – don’t hold back on the specifics. State exactly what you’ll be doing, with who, when, for how long, etc. Moreover, for every design choice you make, make sure you justify it.

In practice, you will likely end up coming back to this chapter once you’ve undertaken all your data collection and analysis, and revise it based on changes you made during the analysis phase. This is perfectly fine. Its natural for you to add an additional analysis technique, scrap an old one, etc based on where your data lead you. Of course, I’m talking about small changes here – not a fundamental switch from qualitative to quantitative, which will likely send your supervisor in a spin!

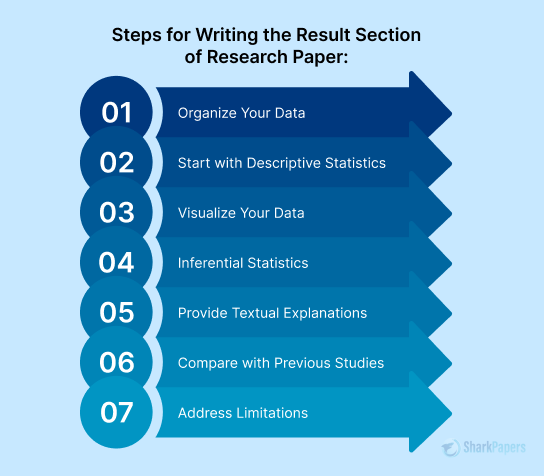

You’ve now collected your data and undertaken your analysis, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. In this chapter, you’ll present the raw results of your analysis . For example, in the case of a quant study, you’ll present the demographic data, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics , etc.

Typically, Chapter 4 is simply a presentation and description of the data, not a discussion of the meaning of the data. In other words, it’s descriptive, rather than analytical – the meaning is discussed in Chapter 5. However, some universities will want you to combine chapters 4 and 5, so that you both present and interpret the meaning of the data at the same time. Check with your institution what their preference is.

Now that you’ve presented the data analysis results, its time to interpret and analyse them. In other words, its time to discuss what they mean, especially in relation to your research question(s).

What you discuss here will depend largely on your chosen methodology. For example, if you’ve gone the quantitative route, you might discuss the relationships between variables . If you’ve gone the qualitative route, you might discuss key themes and the meanings thereof. It all depends on what your research design choices were.

Most importantly, you need to discuss your results in relation to your research questions and aims, as well as the existing literature. What do the results tell you about your research questions? Are they aligned with the existing research or at odds? If so, why might this be? Dig deep into your findings and explain what the findings suggest, in plain English.

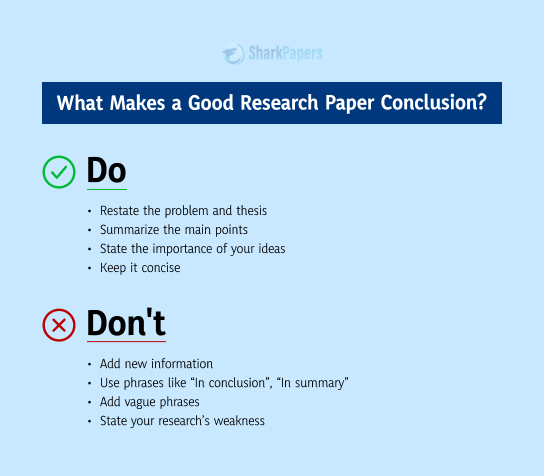

The final chapter – you’ve made it! Now that you’ve discussed your interpretation of the results, its time to bring it back to the beginning with the conclusion chapter . In other words, its time to (attempt to) answer your original research question s (from way back in chapter 1). Clearly state what your conclusions are in terms of your research questions. This might feel a bit repetitive, as you would have touched on this in the previous chapter, but its important to bring the discussion full circle and explicitly state your answer(s) to the research question(s).

Next, you’ll typically discuss the implications of your findings? In other words, you’ve answered your research questions – but what does this mean for the real world (or even for academia)? What should now be done differently, given the new insight you’ve generated?

Lastly, you should discuss the limitations of your research, as well as what this means for future research in the area. No study is perfect, especially not a Masters-level. Discuss the shortcomings of your research. Perhaps your methodology was limited, perhaps your sample size was small or not representative, etc, etc. Don’t be afraid to critique your work – the markers want to see that you can identify the limitations of your work. This is a strength, not a weakness. Be brutal!

This marks the end of your core chapters – woohoo! From here on out, it’s pretty smooth sailing.

The reference list is straightforward. It should contain a list of all resources cited in your dissertation, in the required format, e.g. APA , Harvard, etc.

It’s essential that you use reference management software for your dissertation. Do NOT try handle your referencing manually – its far too error prone. On a reference list of multiple pages, you’re going to make mistake. To this end, I suggest considering either Mendeley or Zotero. Both are free and provide a very straightforward interface to ensure that your referencing is 100% on point. I’ve included a simple how-to video for the Mendeley software (my personal favourite) below:

Some universities may ask you to include a bibliography, as opposed to a reference list. These two things are not the same . A bibliography is similar to a reference list, except that it also includes resources which informed your thinking but were not directly cited in your dissertation. So, double-check your brief and make sure you use the right one.

The very last piece of the puzzle is the appendix or set of appendices. This is where you’ll include any supporting data and evidence. Importantly, supporting is the keyword here.

Your appendices should provide additional “nice to know”, depth-adding information, which is not critical to the core analysis. Appendices should not be used as a way to cut down word count (see this post which covers how to reduce word count ). In other words, don’t place content that is critical to the core analysis here, just to save word count. You will not earn marks on any content in the appendices, so don’t try to play the system!

Time to recap…

And there you have it – the traditional dissertation structure and layout, from A-Z. To recap, the core structure for a dissertation or thesis is (typically) as follows:

- Acknowledgments page

Most importantly, the core chapters should reflect the research process (asking, investigating and answering your research question). Moreover, the research question(s) should form the golden thread throughout your dissertation structure. Everything should revolve around the research questions, and as you’ve seen, they should form both the start point (i.e. introduction chapter) and the endpoint (i.e. conclusion chapter).

I hope this post has provided you with clarity about the traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout. If you have any questions or comments, please leave a comment below, or feel free to get in touch with us. Also, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog .

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

36 Comments

many thanks i found it very useful

Glad to hear that, Arun. Good luck writing your dissertation.

Such clear practical logical advice. I very much needed to read this to keep me focused in stead of fretting.. Perfect now ready to start my research!

what about scientific fields like computer or engineering thesis what is the difference in the structure? thank you very much

Thanks so much this helped me a lot!

Very helpful and accessible. What I like most is how practical the advice is along with helpful tools/ links.

Thanks Ade!

Thank you so much sir.. It was really helpful..

You’re welcome!

Hi! How many words maximum should contain the abstract?

Thank you so much 😊 Find this at the right moment

You’re most welcome. Good luck with your dissertation.

best ever benefit i got on right time thank you

Many times Clarity and vision of destination of dissertation is what makes the difference between good ,average and great researchers the same way a great automobile driver is fast with clarity of address and Clear weather conditions .

I guess Great researcher = great ideas + knowledge + great and fast data collection and modeling + great writing + high clarity on all these

You have given immense clarity from start to end.

Morning. Where will I write the definitions of what I’m referring to in my report?

Thank you so much Derek, I was almost lost! Thanks a tonnnn! Have a great day!

Thanks ! so concise and valuable

This was very helpful. Clear and concise. I know exactly what to do now.

Thank you for allowing me to go through briefly. I hope to find time to continue.

Really useful to me. Thanks a thousand times

Very interesting! It will definitely set me and many more for success. highly recommended.

Thank you soo much sir, for the opportunity to express my skills

Usefull, thanks a lot. Really clear

Very nice and easy to understand. Thank you .

That was incredibly useful. Thanks Grad Coach Crew!

My stress level just dropped at least 15 points after watching this. Just starting my thesis for my grad program and I feel a lot more capable now! Thanks for such a clear and helpful video, Emma and the GradCoach team!

Do we need to mention the number of words the dissertation contains in the main document?

It depends on your university’s requirements, so it would be best to check with them 🙂

Such a helpful post to help me get started with structuring my masters dissertation, thank you!

Great video; I appreciate that helpful information

It is so necessary or avital course

This blog is very informative for my research. Thank you

Doctoral students are required to fill out the National Research Council’s Survey of Earned Doctorates

wow this is an amazing gain in my life

This is so good

How can i arrange my specific objectives in my dissertation?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is A Literature Review (In A Dissertation Or Thesis) - Grad Coach - […] is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Research Paper Writing Guides

Research Paper Thesis

Last updated on: Mar 27, 2024

How to Write a Research Paper Thesis: A Detailed Guide

By: Donna C.

20 min read

Reviewed By: Jared P.

Published on: Jan 6, 2024

Have you ever had trouble making a thesis for your research paper? It's a common challenge, often leaving writers uncertain about where to begin and how to structure their thoughts.

A thesis statement is what your research paper revolves around. The argument, evidence, and facts stated in the thesis are carried out throughout the research paper .

Having said that, the importance of creating a thesis statement that stands out, cannot be denied. But, not everyone is competent enough to craft effective thesis statements.

Fear not!

We've streamlined the process for you, breaking it down into manageable steps. From brainstorming your topic to crafting a clear thesis, we’ll help you write the optimal thesis.

Let’s get going!

On this Page

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

What is a Research Paper Thesis?

To understand the question, “What is a thesis for a research paper?” we’ll look at the standard definition :

“A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.”

Think of it as the roadmap for your readers that guides them throughout the entire research paper.

Usually, thesis statements consist of one or, at most, two sentences . A good thesis isn't just about summarizing; it's about making a clear point and an arguable claim.

The thesis takes place in the research paper introduction. It is a good practice to include the thesis at the end of the introduction paragraph.

For example, If you're exploring how technology affects learning, a strong thesis statement could be:

Now that you know what a research paper thesis is, let’s discuss some characteristics of a good thesis statement in the context of research.

Elements of a Good Research Paper Thesis

A solid research paper thesis is like a well-built foundation for your research work. Here are the key elements that make it strong:

A good thesis is crystal clear, leaving no room for confusion. It conveys the main point clearly and makes sure that the readers grasp the essence of the argument.

Specificity

It goes beyond generalities, providing specific aspects about the focus of the paper. Specificity adds depth and helps in guiding the research process.

Arguability

A strong thesis statement takes a stance on an issue and presents an arguable claim. It sparks curiosity and encourages discussion rather than stating an obvious fact.

Conciseness

Keeping it short and to the point is key. A good thesis doesn’t go off-track—it gets straight to the heart of your message in a sentence or two.

Alignment with Paper Content

A good thesis aligns seamlessly with the content, reflecting the direction and purpose of the research.

Incorporation of Main Ideas

It serves as a preview of the main ideas in the research. A good thesis introduces the key concepts that will be explored and substantiated throughout the research.

A relevant thesis statement connects directly to the research and questions that the author aims to answer. It avoids unnecessary information that might divert from the main focus.

Guidance for Research

An effective thesis summarizes the point and provides a roadmap for your research. It outlines the direction of the research and sets expectations for the reader.

Adaptability

A good thesis remains flexible. As the research progresses, it can be refined to accommodate new insights or changes in the direction of the paper.

Now, let’s see what are the different types of research paper theses.

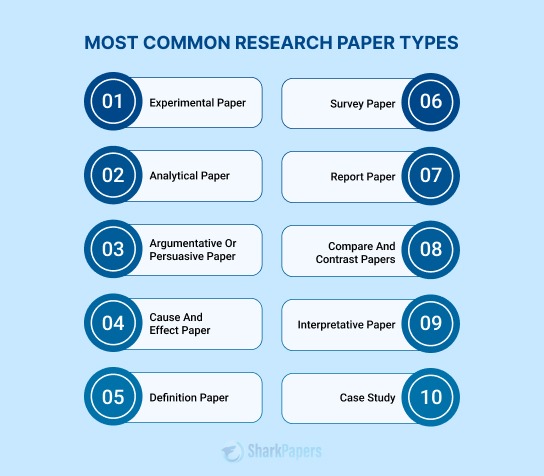

Different Research Paper Thesis Types

Depending on different types of research papers, the thesis can take any of the following forms:

Argumentative Thesis

An argumentative thesis takes a firm stance on a controversial issue and aims to persuade the reader to adopt the same position on the topic. Your goal is not just to present information but to convince others that your perspective is valid.

Including supporting evidence and well-structured arguments play an important role in an argumentative thesis.

Analytical Thesis

An analytical thesis approaches a complex topic by breaking it down into its fundamental components. It aims to understand how these parts interact and contribute to the overall understanding of the subject.

Explanatory Thesis

An explanatory thesis aims to clarify a concept, process, or phenomenon by offering detailed information. It helps explain a topic without picking sides or breaking it into pieces.

These are the most common types of research paper theses. Although there are some other types as well.

- Comparative Thesis: Examines similarities and differences between two or more subjects, presenting an analysis of their relationships.

- Cause and Effect Thesis: Identifies a relationship between events, asserting that one event leads to another and explaining the consequences.

- Descriptive Thesis: Paints a vivid picture of a subject, providing detailed information to create a clear and rich understanding.

- Problem-Solution Thesis: Highlights an issue and proposes specific solutions to address the identified problem.

- Exploratory Thesis: Explores a subject with an open mind, aiming to understand different aspects and perspectives without necessarily forming a definite conclusion.

Now that you have a better understanding of what a research paper thesis is, we’ll get straight to the writing steps.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

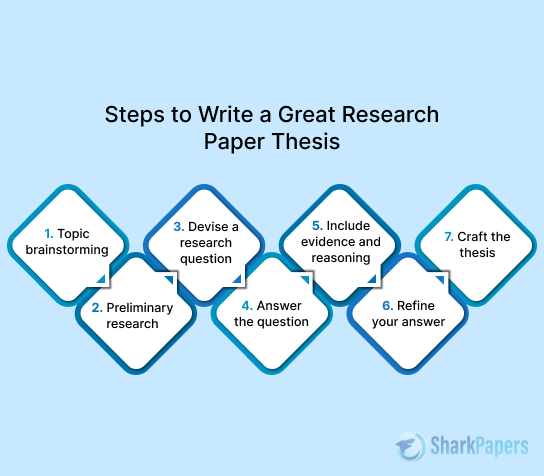

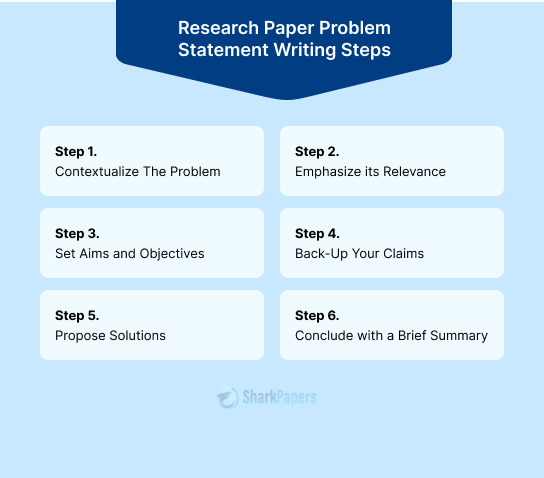

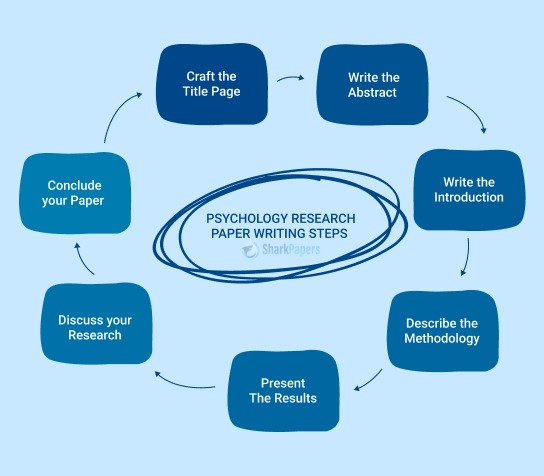

How to Write a Thesis for a Research Paper?

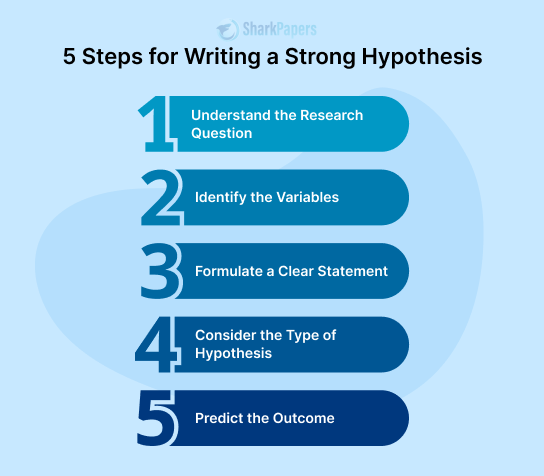

Follow these steps, and you’ll be writing compelling research thesis statements in no time.

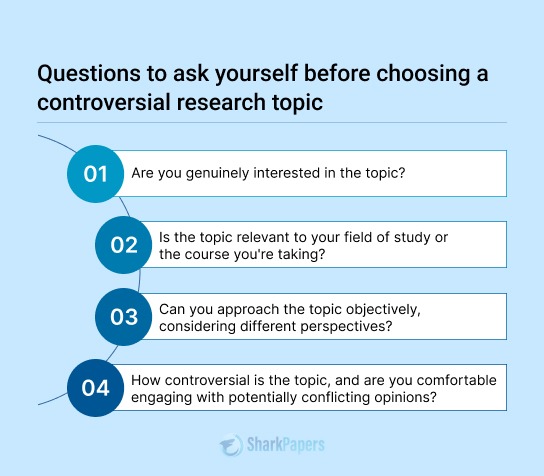

Step 1. Brainstorm Your Topic

If you haven’t yet decided on the research paper topic , the first step is to brainstorm ideas.

- Start with identifying your key research areas and interests.

- Once you pick a general idea, dig deeper.

- Think about what makes you curious about the topic.

For example, if you’ve chosen climate change, your brainstorming might lead you to questions like:

- How does climate change affect wildlife in specific regions?

- What are the human activities contributing to climate change?

Topic brainstorming helps you create a roadmap and aids you in pinpointing areas within the broader topic that you’re most interested in.

Step 2. Conduct Preliminary Research

After brainstorming, the next step is to conduct research and explore what others have discovered about your topic.

You can read books, articles, and reliable sources. Gather information to understand the current state of knowledge on your topic.

Doing preliminary research helps build the foundation of your research thesis. You’ll have a better insight and understanding of your topic if you know it’s background.

Step 3. Choose a Clear Research Question

Now, it's time to narrow down your focus to a specific and well-defined research problem .

Make sure your question is relevant and it aligns with your interests and the assignment.

Here’s how you should narrow down your research questions:

- Get Specific

After looking at the overall topic, narrow it down to a specific aspect.

For example, Instead of saying “climate change,” think about something like “How does cutting down trees (deforestation) add to climate change?” It's like getting focused on one part of the bigger picture.

- Make it Matter

Your question should be important. Ask yourself why it's a big deal to you and why it matters for your assignment.

For example, instead of just wondering about technology and people, ask, “How do smartphones affect our work every day?” This makes your question relevant and calculated.

Be clear about your question and try not to make it confusing. Craft a question that's easy to understand. If your assignment doesn't come with a set question, make one up.

Ask yourself, “What do I want to find out about my topic?” Your self-made question becomes your guide for exploring.

Step 4. Answer the Research Question

After you’ve crafted your research question, comes the time to compose your answer. What you need to do is to think about why this is your response and how you will convince readers.

- First Answer, or Working Thesis:

This is your starting answer, kind of like a rough draft.

For example, If your question is “How does cutting down trees affect climate change?” your first answer could be something like:

- Get Your Direction:

Think of this answer as a compass. It helps you know where you're going in your research project. It's the beginning of your thesis statement, which is the big idea that leads your whole research paper.

Remember, it's okay if this answer changes later as you learn more. It's like starting with a map and adjusting your path as you find new stuff. The point is to start with a thoughtful and informed beginning for your research project.

Step 5. Include Evidence and Reasoning

After making your first educated guess (working thesis), it's time to collect evidence that supports your idea. This is like finding puzzle pieces that fit with your initial thoughts.

If your working thesis is “ Cutting down trees lets out carbon, adding to the warming of the Earth ,” find data that shows how deforestation releases carbon. This data is like your evidence that makes your thesis more convincing.

Use real-life examples and expert opinions to strengthen your thesis.

For instance, if case studies show the environmental impact of deforestation or if reputable scientists have published articles supporting your point, include them.

- Include data showing the correlation between deforestation rates and increased carbon emissions.

- Provide examples of regions where deforestation has led to changes in climate patterns.

- Reference scholarly articles written by environmental experts that discuss the impact of deforestation on global warming.

This step elevates your working thesis to a solid thesis statement by grounding it in concrete evidence and expert perspectives. It transforms your idea into a well-supported argument that has the potential to engage readers from the get-go.

Step 6. Refine Your Answer

Now that you've presented your initial answer backed by evidence and reasoning, it's time to fine-tune it.

- Take a step back and look at your initial answer or working thesis . Does it still hold up in light of the evidence you've gathered? Consider if any adjustments or clarifications are needed.