- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Writing a case report...

Writing a case report in 10 steps

- Related content

- Peer review

- Victoria Stokes , foundation year 2 doctor, trauma and orthopaedics, Basildon Hospital ,

- Caroline Fertleman , paediatrics consultant, The Whittington Hospital NHS Trust

- victoria.stokes1{at}nhs.net

Victoria Stokes and Caroline Fertleman explain how to turn an interesting case or unusual presentation into an educational report

It is common practice in medicine that when we come across an interesting case with an unusual presentation or a surprise twist, we must tell the rest of the medical world. This is how we continue our lifelong learning and aid faster diagnosis and treatment for patients.

It usually falls to the junior to write up the case, so here are a few simple tips to get you started.

First steps

Begin by sitting down with your medical team to discuss the interesting aspects of the case and the learning points to highlight. Ideally, a registrar or middle grade will mentor you and give you guidance. Another junior doctor or medical student may also be keen to be involved. Allocate jobs to split the workload, set a deadline and work timeframe, and discuss the order in which the authors will be listed. All listed authors should contribute substantially, with the person doing most of the work put first and the guarantor (usually the most senior team member) at the end.

Getting consent

Gain permission and written consent to write up the case from the patient or parents, if your patient is a child, and keep a copy because you will need it later for submission to journals.

Information gathering

Gather all the information from the medical notes and the hospital’s electronic systems, including copies of blood results and imaging, as medical notes often disappear when the patient is discharged and are notoriously difficult to find again. Remember to anonymise the data according to your local hospital policy.

Write up the case emphasising the interesting points of the presentation, investigations leading to diagnosis, and management of the disease/pathology. Get input on the case from all members of the team, highlighting their involvement. Also include the prognosis of the patient, if known, as the reader will want to know the outcome.

Coming up with a title

Discuss a title with your supervisor and other members of the team, as this provides the focus for your article. The title should be concise and interesting but should also enable people to find it in medical literature search engines. Also think about how you will present your case study—for example, a poster presentation or scientific paper—and consider potential journals or conferences, as you may need to write in a particular style or format.

Background research

Research the disease/pathology that is the focus of your article and write a background paragraph or two, highlighting the relevance of your case report in relation to this. If you are struggling, seek the opinion of a specialist who may know of relevant articles or texts. Another good resource is your hospital library, where staff are often more than happy to help with literature searches.

How your case is different

Move on to explore how the case presented differently to the admitting team. Alternatively, if your report is focused on management, explore the difficulties the team came across and alternative options for treatment.

Finish by explaining why your case report adds to the medical literature and highlight any learning points.

Writing an abstract

The abstract should be no longer than 100-200 words and should highlight all your key points concisely. This can be harder than writing the full article and needs special care as it will be used to judge whether your case is accepted for presentation or publication.

Discuss with your supervisor or team about options for presenting or publishing your case report. At the very least, you should present your article locally within a departmental or team meeting or at a hospital grand round. Well done!

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ’s policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

Case Report: A Beginner’s Guide with Examples

A case report is a descriptive study that documents an unusual clinical phenomenon in a single patient. It describes in details the patient’s history, signs, symptoms, test results, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. It also contains a short literature review, discusses the importance of the case and how it improves the existing knowledge on the subject.

A similar design involving a group of patients (with the similar problem) is referred to as case series.

Advantages of case reports

Case reports offer, in general a fast, easy and cheap way to report an unusual observation or a rare event in a clinical setting, as these have very small probability of being detected in an experimental study because of limitations on the number of patients that can be included.

These events deserve to be reported since they might provide insights on some exceptions to general rules and theories in the field.

Case reports are great to get first impressions that can generate new hypotheses (e.g. detecting a potential side effect of a drug) or challenge existing ones (e.g. shedding the light on the possibility of a different biological mechanism of a disease).

In many of these cases, additional investigation is needed such as designing large observational studies or randomized experiments or even going back and mining data from previous research looking for evidence for theses hypotheses.

Limitations of case reports

Observing a relationship between an exposure and a disease in a case report does not mean that it is causal in nature.

This is because of:

- The absence of a control group that provides a benchmark or a point of reference against which we compare our results. A control group is important to eliminate the role of external factors which can interfere with the relationship between exposure and disease

- Unmeasured Confounding caused by variables that influence both the exposure and the disease

A case report can have a powerful emotional effect (see examples of case reports below). This can lead to overrate the importance of the evidence provided by such case. In his book Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion , Paul Bloom explains how a powerful story affects our emotions, can distort our judgement and even lead us to make bad moral choices.

When a case report describes a rare event it is important to remember that what we’re reading about is exceptional and most importantly resist generalizations especially because a case report is, by definition, a study where the sample is only 1 patient.

Selection bias is another issue as the cases in case reports are not chosen at random, therefore some members of the population may have a higher probability of being included in the study than others.

So, results from a case report cannot be representative of the entire population.

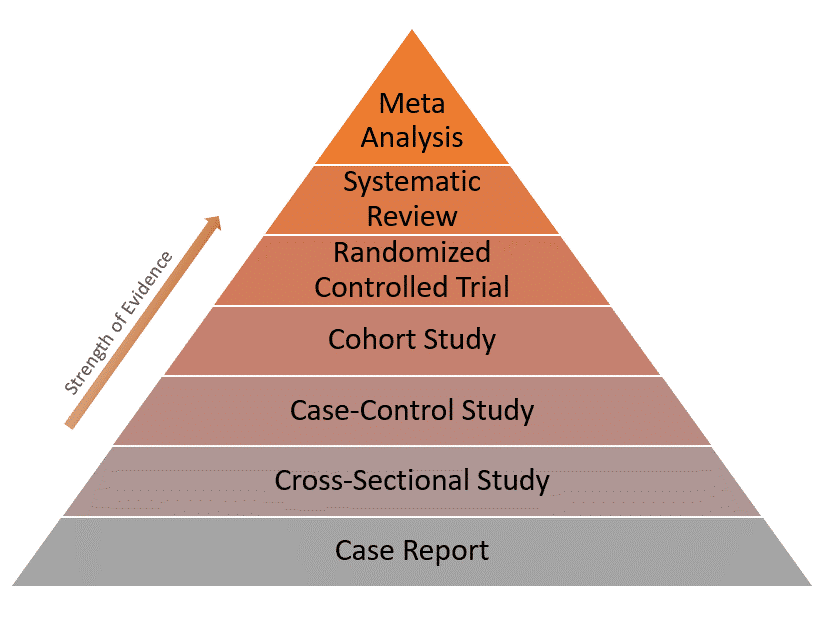

Because of these limitations, case reports have the lowest level of evidence compared to other study designs as represented in the evidence pyramid below:

Real-world examples of case reports

Example 1: normal plasma cholesterol in an 88-year-old man who eats 25 eggs a day.

This is the case of an old man with Alzheimer’s disease who has been eating 20-30 eggs every day for almost 15 years. [ Source ]

The man had an LDL-cholesterol level of only 142 mg/dL (3.68 mmol/L) and no significant clinical atherosclerosis (deposition of cholesterol in arterial walls)!

His body adapted by reducing the intestinal absorption of cholesterol, lowering the rate of its synthesis and increasing the rate of its conversion into bile acid.

This is indeed an unusual case of biological adaptation to a major change in dietary intake.

Example 2: Recovery from the passage of an iron bar through the head

This is an interesting case of a construction foreman named Phineas Gage. [ Source ]

In 1848, due to an explosion at work, an iron bar passed through his head destroying a large portion of his brain’s frontal lobe. He survived the event and the injury only affected 1 thing: His personality!

After the accident, Gage became profane, rough and disrespectful to the extent that he was no longer tolerable to people around him. So he lost his job and his family.

His case inspired further research that focused on the relationship between specific parts of the brain and personality.

- Sayre JW, Toklu HZ, Ye F, Mazza J, Yale S. Case Reports, Case Series – From Clinical Practice to Evidence-Based Medicine in Graduate Medical Education . Cureus . 2017;9(8):e1546. Published 2017 Aug 7. doi:10.7759/cureus.1546.

- Nissen T, Wynn R. The clinical case report: a review of its merits and limitations . BMC Res Notes . 2014;7:264. Published 2014 Apr 23. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-264.

Further reading

- Case Report vs Cross-Sectional Study

- Cohort vs Cross-Sectional Study

- How to Identify Different Types of Cohort Studies?

- Matched Pairs Design

- Randomized Block Design

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Clinical Case Study

In 1970, the world first got acquainted with Genie. It was also the little girl’s first time to see a world beyond the potty chair where she was often bound to. Barely a contact outside for most of her life, she was a ripe case for studying the effects of extreme isolation in young children. Clinical case studies shed light on rare and specific circumstances, like Genie’s ordeal, that help us understand the bigger picture. Largely qualitative research , these case studies are an attempt to understand a subject and the case, usually in relation to a general concept.

8+ Clinical Case Study Templates and Examples

Clinical case studies can focus on a person, group, or community. In contrast to case reports , these studies don’t end in reporting about the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients. Case studies abide by the research methodology and design to understand an experience. During a case study analysis, both subjective and objective accounts of the events are deemed valid data. By focusing on a pixel of the picture, you can learn something that you would have otherwise overlooked. We have prepared the following case study templates that you can use in your research. For your reference, we added examples of scenarios where clinical case studies are being used.

1. Case Study Analysis Template

- Google Docs

Size: A4 & US Letter Sizes

Case studies are a common method of research in medical and psychological sciences. They are vivid narratives about undocumented cases that strike researchers as irregular and interesting. Their highly descriptive content are valuable information to the respective scientific community. They also open new avenues of inquiry and offer an in-depth treatment of a topic that empirical research cannot give. Its comprehensive nature helps make case study a popular research option, even if it falls short of evidence-based data. Thinking of using this research method? Get started with this template!

2. Clinical Case Study Template

Size: 49 KB

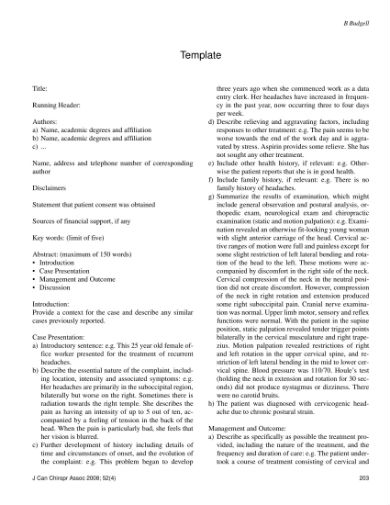

Since the studies contain detailed accounts, you have to format all the information into categories. The defined structure of the article makes all the information easy to absorb. A case study generally contains the following sections: abstract, introduction, patient information, review of related literature, methodology , findings, then the conclusion. The comprehensive nature of this research method might deter novice researchers, while veteran medical writers might just need a reminder. In either case, this sample outline is for you!

3. Clinical Case Study Sample

Size: 939 KB

This research method is usable in answering different inquiries. It is notable that case studies are heavy on the qualitative data. Researchers can obtain relevant data from interviews, questionnaires , personal and patients’ observations, journals, clinical reports, and existing literature. However, as seen in this attached example, quantitative data can also be collected as the researchers deem fit. Because the goal is not to derive data that can represent a population, researchers can use a smaller sample size. Study how to make both numbers and descriptions work to your advantage in preparing your clinical case study with this example!

4. Medical Case Study Example

Size: 563 KB

In a physician’s life, he or she is bound to come across a case that medical school and textbooks did not warn him or her. Clinical case studies are a form of communication about novel findings or observations in practice. Sort of like a medical buzz, the studies contain information like unreported health complications, adverse response to treatment, or new remedial methods. These case studies can also branch into new research directions. This case study illustrates how misdiagnosis can be harmful to the patient. Because some diseases can have overlapping symptoms, it can be hard to identify which is which. The case study alerted the medical community that a seemingly mundane skin condition can point to something more serious.

5. Psychological Case Study Example

Size: 425 KB

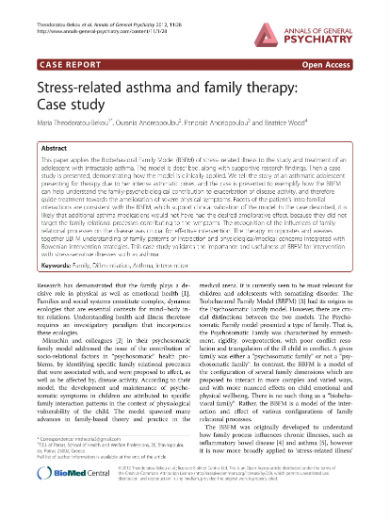

In the field of psychology, clinic psychologists and therapists can report about their interactions with the patient. Some of these cases can stand out as rare and unusual. Others may also serve as a useful reference. Practitioners can obtain information through semi-structured interviews wherein the patient talks with a mental health professional. After the sessions, the practitioner can interpret his or her findings into diagnosis and recommend a treatment plan . Psychology is not entirely removed from medicine. The specialist can incorporate the medical history of the patient in his or her interpretation. This sample case study shows medicine and psychology can work together in the prevention of stress-induced asthma attacks.

6. Sample Clinical Case Study

Size: 85 KB

The descriptive take of clinical case studies on a situation presents an exhaustive analysis that is not available in empirical research. However, the qualitative nature of these studies is a double-edged sword. The combination of subjective and objective analysis makes the content susceptible to personal biases. Because the case is unique to an individual or a group, researchers cannot replicate the result. The replicability of findings is a hallmark of reliable research. Therefore, clinical case studies have a low-reliability measure. The attached case study is an example of the use of descriptive analysis in the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with depression and adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety.

7. Medical Case Study Guide

Size: 266 KB

Another point raised against clinical case studies is the issue of memory distortion. The human memory is not a machine that can record and retrieve information at command. It is fallible, and it will make mistakes. The patients can emphasize a few parts of their history and overlook otherwise important pieces of the puzzle. Reliance on memory recall when writing the study can also fail the researchers. The sample clinical case study added here shows how a patient’s recollection of events in her life can be used in the presentation of the case. If the patient failed to recall important details, the researchers might have a different interpretations of the case.

8. Student Medical Case Study

Despite criticisms regarding susceptibility to biases and low-reliability measure, clinical case studies have been an indispensable tool for learning. Studies have reported a significant improvement in the academic performance of students after the integration of case studies into the learning ecosystem. Case studies are situation-based narratives about a textbook principle. Application-motivated learning is effective because the theoretical framework isn’t removed from the real-world experience. This case study is an example of those that are used in the classroom. The students are presented with a problem and series of follow up questions that will help them understand and address the issues exhibited.

9. Clinical Case Study Article

Size: 171 KB

Unlike empirical investigations, the goal is not to come up with results that can represent a population. Case studies focus on understanding an unusual plight through subjective and objective analysis. Understandably, such situation might not hold for most people. They are also the method of choice for understanding circumstances that cannot be reproduced in controlled testing environments, like Genie’s case earlier or the case discussed in the attached case study sample. Therapy for anorexia nervosa and obsessive personality disorder is hard to come by using quantitative research. Replicating such conditions will constitute a criminal offense. What case studies lack in the universality of the results, they make up for the richness of the insights obtained. It acknowledges that the human experience will always have a degree of subjectivity. This defense of clinical case studies makes them significant in their own right.

AI Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

- Policy & Compliance

- Clinical Trials

NIH Definition of Clinical Trial Case Studies

The case studies provided below are designed to help you identify whether your study would be considered by NIH to be a clinical trial. Expect the case studies and related guidance to evolve over the upcoming year. For continuity and ease of reference, case studies will retain their original numbering and will not be renumbered if cases are revised or removed.

The simplified case studies apply the following four questions to determine whether NIH would consider the research study to be a clinical trial:

- Does the study involve human participants?

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention?

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants?

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome?

If the answer to all four questions is “yes,” then the clinical study would be considered a clinical trial according to the NIH definition.

See this page for more information about the NIH definition of a clinical trial.

General Case Studies

Institute or center specific case studies.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants who are randomized to receive one of two approved drugs. It is designed to compare the effects of the drugs on the blood level of a protein.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, the study involves human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive an intervention, one of two drugs.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of the drugs on the level of the protein in the participants’ blood.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, the level of a protein, is a health-related biomedical outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with condition Y to receive a drug that has been approved for another indication. It is designed to measure the drug’s effects on the level of a biomarker associated with the severity of condition Y.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive an intervention, the approved drug.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the drug’s effect on the level of the biomarker.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, the level of a biomarker, is a health-related biomedical outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with condition X to receive investigational compound A. It is designed to assess the pharmacokinetic properties of compound A.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive an intervention, compound A.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate how the body interacts with compound A

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, pharmacokinetic properties, is a health-related biomedical outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with disease X to receive an investigational drug. It is designed to assess safety and determine the maximum tolerated dose of the drug.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive an intervention, the investigational drug.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to assess safety and determine the maximum tolerated dose of the investigational drug.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, safety and maximum tolerated dose, is a health-related biomedical outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with disease X to receive a chronic disease management program. It is designed to assess usability and to determine the maximum tolerated dose of the chronic disease program (e.g., how many in-person and telemedicine visits with adequate adherence).

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive an intervention, the chronic disease management program.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to determine the maximum tolerated dose of the program to obtain adequate adherence.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, tolerable intensity and adequate adherence of the intervention, is a health-related outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with disease X to receive either an investigational drug or a placebo. It is designed to evaluate the efficacy of the investigational drug to relieve disease symptoms.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive an intervention, the investigational drug or placebo.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of the investigational drug on the participants’ symptoms.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, relief of symptoms, is a health-related outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with disease X to receive an investigational drug. It is designed to assess whether there is a change in disease progression compared to baseline. There is no concurrent control used in this study.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of the investigational drug on the subject’s disease progression.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, disease progression, is a health-related outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with disease X to test an investigational in vitro diagnostic device (IVD). It is designed to evaluate the ability of the device to measure the level of an antibody in blood.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, in this context the IVD would not be considered an intervention. The IVD is being used to test its ability to measure antibody levels, but not to test its effects on any health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with disease X to be evaluated with an investigational in vitro diagnostic device (IVD). The study is designed to evaluate how knowledge of certain antibody levels impacts clinical management of disease.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to an intervention, measurement of an antibody level, with the idea that knowledge of that antibody level might affect clinical management.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate how knowledge of the level of an antibody might inform treatment.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being measured, how blood antibody levels inform treatment, is a health-related outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of healthy volunteers who will be randomized to different durations of sleep deprivation (including no sleep deprivation as a control) and who will have stress hormone levels measured. It is designed to determine whether the levels of stress hormones in blood rise in response to different durations of sleep deprivation.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, the healthy volunteers are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to an intervention, different durations of sleep deprivation followed by a blood draw.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to measure the effect of different durations of sleep deprivation on stress hormone levels.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, stress hormone levels, is a health-related biomedical outcome.

The study involves the analysis of de-identified, stored blood samples and de-identified medical records of patients with disease X who were treated with an approved drug. The study is designed to evaluate the level of a protein in the blood of patients that is associated with therapeutic effects of the drug.

- Does the study involve human participants? No, the study does not involve human participants because only de-identified samples and information are used.

The study involves the analysis of identifiable, stored blood samples and identified medical records of patients with disease X who were treated with an approved drug. The study is designed to evaluate the level of a protein in the blood of patients that is associated with therapeutic effects of the drug.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, patients are human participants because the blood and information are identifiable.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, secondary research with biospecimens or health information is not a clinical trial.

The study involves the recruitment of a healthy volunteers whose blood is drawn for genomic analysis. It is designed to identify the prevalence of a genetic mutation in the cohort and evaluate potential association between the presence of the mutation and the risk of developing a genetic disorder.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, sample collection (blood draw) is not an intervention in this context.

Physicians report that some patients being treated with drug A for disease X are also experiencing some improvement in a second condition, condition Y. The study involves the recruitment of research participants who have disease X and condition Y and are being treated with drug A. The participants are surveyed to ascertain whether they are experiencing an improvement in condition Y.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, participants are not prospectively assigned to receive an intervention as they are receiving drugs as part of their clinical care. The surveys are being used for measurement, not to modify a biomedical or behavioral outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of patients with disease X who are receiving one of three standard therapies as part of their clinical care. It is designed to assess the relative effectiveness of the three therapies by monitoring survival rates using medical records over a few years.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, there is no intervention. The therapies are prescribed as part of clinical care; they are not prospectively assigned for the purpose of the study. The study is observational.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with disease X vs. healthy controls and comparing these participants on a range of health processes and outcomes including genomics, biospecimens, self-report measures, etc. to explore differences that may be relevant to the development of disease X.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, the measures needed to assess the outcomes are not interventions in this context, as the study is not intended to determine whether the measures modify a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of healthy volunteers for a respiratory challenge study; participants are randomized to receive different combinations of allergens. The study evaluates the severity and mechanism of the immune response to different combinations of allergens introduced via inhalation.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, healthy volunteers are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, healthy volunteers are prospectively assigned to randomly selected combinations of allergens.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is evaluating the effects of different combinations of allergens on the immune response in healthy individuals.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the study evaluates the severity and mechanism of the immune reaction to allergens, which are health-related biomedical outcomes.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to evaluate the effects of an investigational drug on memory, and retention and recall of information.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, participants are prospectively assigned to receive the investigational drug.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is evaluating the effects of the drug on participants’ memory.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the study evaluates memory, and retention and recall of information in the context of AD.

The study involves the recruitment of individuals to receive a new behavioral intervention for sedentary behavior. It is designed to measure the effect of the intervention on hypothesized differential mediators of behavior change.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, participants are prospectively assigned to receive a behavioral intervention.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is evaluating the effects of the intervetion on mediators of behavior change.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, mediators of behavior change, are behavioral outcomes relevant to health.

The study involves the recruitment of patients with disease X to be evaluated with a new visual acuity task. It is designed to evaluate the ability of the new task to measure visual acuity as compared with the gold standard Snellen Test

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to an intervention, the new visual acuity test.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? No, the study is designed to evaluate the ability of the new visual acuity test to measure visual acuity as compared to the gold standard Snellen Test, but not to modify visual acuity.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with CHF who were hospitalized before or after implementation of the Medicare incentives to reduce re-hospitalizations. Morbidity, mortality, and quality of life of these participants are evaluated to compare the effects of these Medicare incentives on these outcomes.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, the intervention (incentives to reduce re-hospitalization) were assigned by Medicare, not by the research study.

The study involves the recruitment of healthcare providers to assess the extent to which being provided with genomic sequence information about their patients informs their treatment of those patients towards improved outcomes.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, both the physicians and the patients are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, physicians are prospectively assigned to receive genomic sequence information, which is the intervention.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of intervening with physicians, on the treatment they provide to their patients.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related, biomedical, or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, the extent to which providing specific information to physicians informs the treatment of patients, is a health-related outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants with a behavioral condition to receive either an investigational behavioral intervention or a behavioral intervention in clinical use. It is designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the investigational intervention compared to the intervention in clinical use in reducing the severity of the obsessive compulsive disorder.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to an intervention, either the investigational intervention or an intervention in clinical use.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate whether the investigational intervention is as effective as the standard intervention, at changing behavior.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related, biomedical, or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, the interventions’ effectiveness in reducing the severity of the condition, is a health-related behavioral outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of physicians who will be randomly assigned to use a new app or an existing app, which cues directed interviewing techniques. The study is designed to determine whether the new app is better than the existing app at assisting physicians in identifying families in need of social service support. The number of community service referrals will be measured.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, both the physicians and the families are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, physicians are prospectively assigned to use one of two apps, which are the interventions.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of intervening with physicians, on social service support referral for families.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related, biomedical, or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, the number of referrals, is a health-related outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of parents to participate in focus groups to discuss topics related to parental self-efficacy and positive parenting behaviors. It is designed to gather information needed to develop an intervention to promote parental self-efficacy and positive parenting behaviors.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, the parents are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, a focus group is not an intervention.

The study involves the recruitment of healthy volunteers to test a new behavioral intervention. It is designed to evaluate the effect of a meditation intervention on adherence to exercise regimens and quality of life to inform the design of a subsequent, fully-powered trial.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, study participants are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to a behavioral intervention.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on adherence, and quality of life.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, adherence and quality of life are health-related outcomes.

A study will test the feasibility a mobile phone app designed to increase physical activity. A group of sedentary individuals will use the app for a week while their interactions with the app are monitored. The number of interactions with the app will be measured, as well as any software issues. Participants will also complete a survey indicating their satisfaction with and willingness to use the app, as well as any feedback for improvement. The app’s effect on physical activity, weight, or cardiovascular fitness will not be evaluated.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, sedentary individuals will be enrolled.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? The participants will interact with the app for a week.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? No. While the participants’ interactions are monitored (steps or heart rate may be recorded in this process), the study is NOT measuring the effect of using the app ON the participant. The study is only measuring the usability and acceptability of the app, and testing for bugs in the software. The effect on physical activity is NOT being measured.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? N/A

The study involves the recruitment of healthy family members of patients hospitalized for disease X to test two CPR training strategies. Participants will receive one of two training strategies. The outcome is improved CPR skills retention.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, family members of patients are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to one of two CPR educational strategies.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of educational strategies on CPR skills.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, retention of CPR skills is a health-related behavioral outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of research participants in three different communities (clusters) to test three CPR training strategies. The rate of out-of- hospital cardiac arrest survival will be compared.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive one of three types of CPR training, which is the intervention.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of different CPR training strategies on patient survival rates post cardiac arrest.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival is a health-related outcome.

A study involves the recruitment of school children to evaluate two different tools for monitoring food intake. Food consumption behavior will be measured by asking children to activate a pocket camera during meals and to use a diary to record consumed food. The accuracy of the two food monitoring methods in measuring energy intake will be assessed.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, children are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, in this context the monitoring methods would not be considered an intervention. The study is designed to test the accuracy of two monitoring methods, but not to test the effect on any health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes.

A study involves the recruitment of school children to evaluate two different tools for monitoring food intake. Food consumption behavior will be measured by asking children to activate a pocket camera during meals and to use a diary to record consumed food. Changes to eating behavior will be assessed.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to two food monitoring methods.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to determine whether using the monitoring methods changes eating behavior.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, eating behavior is a health-related outcome.

A study involves the recruitment of children at two schools to monitor eating behavior. Children’s food choices will be monitored using a remote food photography method. Food consumption and the accuracy of food monitoring methods will be assessed.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, the children participating in this study are human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, not in this context. The study involves observing and measuring eating behavior, but not modifying it. This is an observational study.

A study involves the recruitment of children at two schools to evaluate their preferences for graphics and colors used in healthy food advertisements. Children will be presented with multiple health advertisements and their preferences for graphics and colors will be assessed.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to see different advertisements.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the advertisements.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? No, preferences are not health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes.

The study involves ambulatory patients who have new-onset stable angina and who are recruited from community practices. They are randomized to undergo CT angiography or an exercise stress test of the doctor’s choice. To keep the trial pragmatic, the investigators do not prescribe a protocol for how physicians should respond to test results. The study is designed to determine whether the initial test (CT angiography or stress test) affects long-term rates of premature death, stroke, or myocardial infarctions.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are randomized to undergo CT angiography or an exercise stress test.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to determine whether the initial test done affects long-term rates of certain clinical events.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, premature death, stroke, and myocardial infarction are health-related biomedical outcomes.

The study involves patients who present with stable angina to community practices. As part of their routine care some of their physicians refer them for CT angiography, while others refer them for exercise stress tests. The study is designed to see whether or not there's an association between the type of test that is chosen and long-term risk of death, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, the intervention is not prospectively assigned by the investigators. Rather, the intervention, in this case diagnostic study, occurs as part of routine clinical care.

The investigators conduct a longitudinal study of patients with schizophrenia. Their physicians, as part of their standard clinical care, prescribe antipsychotic medication. The investigators conduct an imaging session before starting treatment; they repeat imaging 4-6 weeks later.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, not in this context. Antipsychotic medications are given as part of clinical care, not as part of a prospective, approved research protocol.

The investigators conduct a longitudinal study of patients with schizophrenia. Their physicians, as part of their standard clinical care, prescribe antipsychotic medication. As part of the research protocol, all participants will be prescribed the same dose of the antipsychotic medication. The investigators conduct an imaging session before starting treatment; they repeat imaging 4-6 weeks later.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, although participants are all receiving antipsychotic medication as part of their standard medical care, the dose of the antipsychotic medication is determined by the research protocol, rather than individual clinical need.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of a dose of antipsychotic medication on brain function.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome ? Yes, brain function measured by imaging is a health-related outcome.

The study involves recruitment of healthy volunteers who will wear a thermal compression device around their legs. This pilot study is designed to examine preliminary performance and safety of a thermal compression device worn during surgery. Investigators will measure core temperature, comfort, and presence of skin injury in 15-minute intervals.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, participants are assigned to wear a thermal compression device.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of the thermal compression device on participant core temperature, comfort, and presence of skin injury.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome ? Yes, participant core temperature, comfort, and presence of skin injury are health-related biomedical outcomes.

The study involves collection of data on hospitalizations for various acute illnesses among people who live close to a border between two states that have recently implemented different laws related to public health (e.g. smoking regulations, soda taxes). The investigators want to take advantage of this “natural experiment” to assess the health impact of the laws.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, the study involves human participants.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, the interventions were assigned by state laws and state of residence, not by the research study.

The study involves recruitment of healthy volunteers to engage in working memory tasks while undergoing transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to induce competing local neuronal activity. The study is measuring task performance to investigate the neural underpinnings of working memory storage and processing.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, healthy volunteers are prospectively assigned to receive TMS stimulation protocols during a working memory task.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is evaluating the effects of local TMS stimulation on working memory performance and oscillatory brain activity in healthy individuals.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the study evaluates working memory processes, which are health-related biomedical outcomes.

The study involves recruitment of healthy volunteers to engage in a social valuation task while dopamine tone in the brain is manipulated using tolcapone, an FDA-approved medication. The study aims to understand the role of dopamine in social decision-making and to search for neural correlates of this valuation using fMRI.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, healthy volunteers are prospectively assigned to receive tolcapone during a social valuation task.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is evaluating the effects of modulating dopamine tone on social decision-making. Although this study uses an FDA-approved drug to modulate dopamine tone, the goal of this intervention is to understand the role of dopamine in a fundamental phenomenon (social valuation), and not to study the mechanism of action of the drug or its clinical effects.

The career development candidate proposes to independently lead a study to test a new drug A on patients with disease X. Patients will be randomized to a test and control group, with the test group receiving one dose of drug A per week for 12 months and controls receiving placebo. To assess presence, number, and type of any polyps, a colonoscopy will be performed. To assess biomarkers of precancerous lesions, colon mucosal biopsies will be collected. Complete blood count will be measured, and plasma will be stored for potential biomarker evaluation.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive an intervention, drug A or placebo.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of drug A and placebo on the presence and type of polyps.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, the presence and type of polyps, is a health-related biomedical outcome.

Ancillary Study to Case Study #42b: Some types of drug A being evaluated in Case Study #42a have been reported to impact renal function. An internal medicine fellow performs an ancillary study where stored plasma from Case Study #42a will be evaluated for multiple biomarkers of renal function.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, patients are human participants because the plasma and information are identifiable.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, because the assignment of participants to an intervention occurs as part of an existing, separately funded clinical trial. This proposal would be considered an ancillary study that is not an independent clinical trial.

Ancillary Study to Case Study #42a: An internal medicine fellow designs an independent ancillary trial where a subset of patients from the parent trial in Case Study #42a will also receive drug B, based on the assumption that a two-drug combination will work significantly better than a single drug at both improving renal function and reducing polyps. The test subjects will be evaluated for renal function via plasma clearance rates at 6 and 12 months after initiation of drugs A and B.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to receive an intervention, drugs A and B.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of drugs A and B on renal function.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the effect being evaluated, renal function, is a health-related biomedical outcome.

A group of healthy young adults will perform a Go/No-Go task while undergoing fMRI scans. The purpose of the study is to characterize the pattern of neural activation in the frontal cortex during response inhibition, and the ability of the participant to correctly withhold a response on no-go

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, healthy young adults will be enrolled in this study.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants will be prospectively assigned to perform a Go/No-Go task, which involves different levels of inhibitory control.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of the Go/No-Go task on neural activation in the frontal cortex. The study will measure inhibitory control and the neural systems being engaged. In this study, the Go/No-Go task is the independent variable, and behavioral performance and the associated fMRI activations are the dependent variables.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the neural correlates of inhibitory control and behavioral performance are health-related biomedical outcomes.

A group of adolescents will participate in a longitudinal study examining changes in executive function over the course of a normal school year. Color naming performance on the standard version of the Stroop test will be obtained. All measures will be compared at multiple time points during the school year to examine changes in executive function. The purpose is to observe changes in executive function and to observe if differences exist in the Stroop effect over the course of the school year for these adolescents.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, adolescents will be enrolled in this study.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, there is no intervention in this study and no independent variable manipulated. The adolescents are not prospectively assigned to an intervention, but instead the investigator will examine variables of interest (including the Stroop test) over time. The Stroop effect is used as a measurement of point-in-time data.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? No, there is no intervention. Performance on the Stroop test is a well-established measure of executive function and the test is not providing an independent variable of interest here. It is not being used to manipulate the participants or their environment. The purpose is simply to obtain a measure of executive function in adolescents over the course of the school year.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? N/A. No effect of an intervention is being evaluated.

A group of participants with social anxiety will perform an experimentally manipulated Stroop test. In this variant of the Stroop test, the stimuli presented are varied to include emotional and neutral facial expressions presented in different colors. Participants are instructed to name the colors of the faces presented, with the expectation that they will be slower to name the color of the emotional face than the neutral face. The purpose of the study is to examine the degree to which participants with social anxiety will be slower to process emotional faces than neutral faces.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, participants with social anxiety will be enrolled in this study.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants will be prospectively assigned to perform a modified Stroop test using different colored emotional/neutral faces to explore emotional processing in people with social anxiety. Note that the independent variable is the presentation of emotional vs neutral faces.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to measure the effect of emotional valence (i.e. emotional faces) on participant response time to name the color. The purpose is to determine whether the response time to emotional faces is exaggerated for people with social anxiety as compared to neutral faces. Note that the response time to name the colors is the dependent variable in this study.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the processing of emotional information is a health-related biomedical outcome.

The study involves healthy volunteers and compares temporal SNR obtained with a new fMRI pulse sequence with that from another sequence.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, in this context the different pulse sequences would not be considered an intervention. The pulse sequences are not being used to modify any biomedical or behavioral outcome; rather the investigator is comparing performance characteristics of the two pulse sequences.

The study is designed to demonstrate that a new imaging technology (e.g. MRI, PET, ultrasound technologies, or image processing algorithm) is equivalent to, or has better sensitivity/specificity than a standard of care imaging technology. Aim one will use the new imaging technology and the gold standard in ten healthy volunteers. Aim Two will use the new imaging technology and the gold standard before and after a standard care procedure in ten patients. In both aims the performance of the new technology will be compared to the gold standard. No clinical care decisions will be made based on the use of the device in this study.

- Does the study involve human participants? YES. Aim one will study ten healthy volunteers, and aim two will study ten patient volunteers.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, participants will be prospectively assigned to be evaluated with a new imaging technology and the gold standard technology.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? No, the study is not measuring the effect of the technologies ON the human subjects. The study is determining if the new technology is equivalent or better than the gold standard technology. No effect on the participant is being measured.

An investigator proposes to add secondary outcomes to an already funded clinical trial of a nutritional intervention. The trial is supported by other funding, but the investigator is interested in obtaining NIH funding for studying oral health outcomes. Participants in the existing trial would be assessed for oral health outcomes at baseline and at additional time points during a multi-week dietary intervention. The oral health outcomes would include measures of gingivitis and responses to oral health related quality of life questionnaires. Oral fluids would be collected for analysis of inflammatory markers and microbiome components.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, because the assignment of participants to an intervention (and the administration of the intervention) occur as part of an existing, separately funded clinical trial. This proposal would be considered an ancillary study that leverages an already existing clinical trial.

The goal of the project is to use functional neuroimaging to distinguish patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD) who experience TMD pain through centralized pain processes from those with TMD related to peripheral pain. Pain processing in a study cohort of TMD patients and healthy controls will be measured through functional magnetic resonance neuroimaging (fMRI) following transient stimulation of pain pathways through multimodal automated quantitative sensory testing (MAST QST). TMD patients will receive study questionnaires to better correlate the extent to which TMD pain centralization influences TMD prognosis and response to standard of care peripherally targeted treatment (prescribed by physicians, independently of the study).

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, not in this context. The transient stimulation of pain pathways and the fMRI are being performed to measure and describe brain activity, but not to modify it.

An investigator proposes to perform a study of induced gingivitis in healthy humans, to study microbial colonization and inflammation under conditions of health and disease. During a 3-week gingivitis induction period, each study participant will use a stent to cover the teeth in one quadrant during teeth brushing. A contralateral uncovered quadrant will be exposed to the individual's usual oral hygiene procedures, to serve as a control. Standard clinical assessments for gingivitis will be made and biospecimens will be collected at the point of maximal induced gingivitis, and again after normal oral hygiene is resumed. Biospecimens will be assessed for microbial composition and levels of inflammation-associated chemokines.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to an intervention, abstaining from normal oral hygiene for a portion of the mouth, to induce gingivitis.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to evaluate the effect of the induced gingivitis on microbial composition and levels of inflammatory chemokines in oral samples.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, the microbial composition and chemokine levels in oral samples are health-related biomedical outcomes.

The study will enroll older adults with hearing loss, comparing the effectiveness of enhanced hearing health care (HHC) to usual HHC. In addition to routine hearing-aid consultation and fitting, participants randomized to enhanced HCC will be provided patient-centered information and education about a full range of hearing assistive technologies and services. Study outcomes include the utilization of technology or services, quality of life, communication abilities, and cognitive function.

- Does the study involve human participants? Yes, the study enrolls older adults with hearing loss.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, participants are randomized to receive enhanced HCC or usual HCC interventions.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study will evaluate enhanced HCC’s effectiveness in modifying participant behavior and biomedical outcomes.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, rate of technology/service utilization is a behavioral outcome and quality of life, communications, and cognition are biomedical outcomes that may be impacted by the interventions.

The study involves the recruitment of obese individuals who will undergo a muscle biopsy before and after either exercise training or diet-induced weight loss. Sarcolemmal 1,2-disaturated DAG and C18:0 ceramide species and mitochondrial function will be measured. Levels will be correlated with insulin sensitivity.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are assigned to either exercise training or a diet.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to compare the effects of the interventions on muscle metabolism.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, muscle metabolism/signaling is a health-related outcome.

The study involves the recruitment of participants with type 2 diabetes who will undergo a muscle biopsy before and after a fast to measure acetylation on lysine 23 of the mitochondrial solute carrier adenine nucleotide translocase 1 (ANT1). Levels will be related to rates of fat oxidation.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are assigned to undergo a fast.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to compare the effects of the fast on molecular parameters of metabolism.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, metabolism is a health-related outcome.

Insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive nondiabetic adults who have a parent with type 2 diabetes will be followed over time to understand the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the development of diabetes. Oral glucose tolerance tests will be performed annually to measure insulin sensitivity and glycemic status. Participants will also undergo a brief bout of exercise, and mitochondrial ATP synthesis rates will be measured by assessing the rate of recovery of phosphocreatine in the leg muscle, using 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, the participants are not assigned to an intervention; the OGTT and 31P MRS are measures.

Participants with chronic kidney disease will be recruited to receive one of two drug agents. After 6 weeks of therapy, subjects will undergo vascular function testing and have measures of oxidative stress evaluated in their plasma and urine. Results of the function testing and the oxidative stress biomarkers will be related to drug treatment.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are assigned to receive two different drugs.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to compare the effects of the drugs on vascular function.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, vascular function is a health-related outcome.

Participants with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease will be recruited to receive an oral curcumin therapy or placebo and the participants will undergo vascular function testing, renal imaging to assess kidney size, and assessment of oxidative stress biomarkers in urine and plasma after an ascorbic acid challenge. Changes in these outcomes will be related to oral therapy.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are assigned to receive medication or placebo.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? Yes, the study is designed to compare the effects of the drugs on vascular function and kidney size.

- Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? Yes, vascular function and kidney size are health-related outcomes.

Kidney transplant recipients will be recruited to undergo an experimental imaging procedure at several timepoints up to 4 months post-transplantation. Output from the images will be related to pathological assessments of the transplant as well as clinical measures of renal function.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? No, the participants are not assigned to receive an intervention. They undergo transplantation as part of their routine clinical care. The imaging procedure is a measure and not an intervention.

The study proposes the development of a novel probe to assess clearance of a nutritional metabolite in a given disease state. The probe is a GMP grade, deuterated, intravenously administered tracer and clearance is assessed by mass spectrometry analysis of serial blood draws. Participants will either receive a micronutrient supplement or will receive no supplementation. The clearance rate of the probe will be compared in the two groups, to understand the performance of the probe.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are assigned to receive either a micronutrient supplement or nothing.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? No, the intervention is being used to assess the performance of the probe and is not looking at an effect on the participant.

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? Yes, the participants are assigned to receive a controlled diet for three days.

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? No, the intervention (controlled diet) is being used to minimize exogenous dietary sources of oxalate in the participants prior to the labeled tracer infusion. The study will not be evaluating the effect of the diet on the participants.

This page last updated on: April 28, 2021

- Bookmark & Share

- E-mail Updates

- Help Downloading Files

- Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

- NIH... Turning Discovery Into Health

Clinical Researcher

Lessons Learned from Challenging Cases in Clinical Research Ethics

Clinical Researcher April 12, 2024

Clinical Researcher—April 2024 (Volume 38, Issue 2)

RESOURCES & REVIEWS

Lindsay McNair, MD, MPH, MSB

[A review of Challenging Cases in Clinical Research Ethics . 2024. Wilfond BS, Johnson L-M, Duenas DM, Taylor HA (editors). CRC Press (Boca Raton, Fla.)]

Challenging Cases in Clinical Research Ethics may not be a book you take to the beach for a light read, but if you have a role, or an interest, in how we analyze the complex ethical challenges that are an integral part of conducting clinical research, it may be a good book for you. This is a reference book, a teaching tool, and, in some ways, a historical record.