An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clinics (Sao Paulo)

Approaching literature review for academic purposes: The Literature Review Checklist

Debora f.b. leite.

I Departamento de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, Faculdade de Ciencias Medicas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, BR

II Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Pernambuco, PE, BR

III Hospital das Clinicas, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Pernambuco, PE, BR

Maria Auxiliadora Soares Padilha

Jose g. cecatti.

A sophisticated literature review (LR) can result in a robust dissertation/thesis by scrutinizing the main problem examined by the academic study; anticipating research hypotheses, methods and results; and maintaining the interest of the audience in how the dissertation/thesis will provide solutions for the current gaps in a particular field. Unfortunately, little guidance is available on elaborating LRs, and writing an LR chapter is not a linear process. An LR translates students’ abilities in information literacy, the language domain, and critical writing. Students in postgraduate programs should be systematically trained in these skills. Therefore, this paper discusses the purposes of LRs in dissertations and theses. Second, the paper considers five steps for developing a review: defining the main topic, searching the literature, analyzing the results, writing the review and reflecting on the writing. Ultimately, this study proposes a twelve-item LR checklist. By clearly stating the desired achievements, this checklist allows Masters and Ph.D. students to continuously assess their own progress in elaborating an LR. Institutions aiming to strengthen students’ necessary skills in critical academic writing should also use this tool.

INTRODUCTION

Writing the literature review (LR) is often viewed as a difficult task that can be a point of writer’s block and procrastination ( 1 ) in postgraduate life. Disagreements on the definitions or classifications of LRs ( 2 ) may confuse students about their purpose and scope, as well as how to perform an LR. Interestingly, at many universities, the LR is still an important element in any academic work, despite the more recent trend of producing scientific articles rather than classical theses.

The LR is not an isolated section of the thesis/dissertation or a copy of the background section of a research proposal. It identifies the state-of-the-art knowledge in a particular field, clarifies information that is already known, elucidates implications of the problem being analyzed, links theory and practice ( 3 - 5 ), highlights gaps in the current literature, and places the dissertation/thesis within the research agenda of that field. Additionally, by writing the LR, postgraduate students will comprehend the structure of the subject and elaborate on their cognitive connections ( 3 ) while analyzing and synthesizing data with increasing maturity.

At the same time, the LR transforms the student and hints at the contents of other chapters for the reader. First, the LR explains the research question; second, it supports the hypothesis, objectives, and methods of the research project; and finally, it facilitates a description of the student’s interpretation of the results and his/her conclusions. For scholars, the LR is an introductory chapter ( 6 ). If it is well written, it demonstrates the student’s understanding of and maturity in a particular topic. A sound and sophisticated LR can indicate a robust dissertation/thesis.

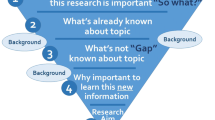

A consensus on the best method to elaborate a dissertation/thesis has not been achieved. The LR can be a distinct chapter or included in different sections; it can be part of the introduction chapter, part of each research topic, or part of each published paper ( 7 ). However, scholars view the LR as an integral part of the main body of an academic work because it is intrinsically connected to other sections ( Figure 1 ) and is frequently present. The structure of the LR depends on the conventions of a particular discipline, the rules of the department, and the student’s and supervisor’s areas of expertise, needs and interests.

Interestingly, many postgraduate students choose to submit their LR to peer-reviewed journals. As LRs are critical evaluations of current knowledge, they are indeed publishable material, even in the form of narrative or systematic reviews. However, systematic reviews have specific patterns 1 ( 8 ) that may not entirely fit with the questions posed in the dissertation/thesis. Additionally, the scope of a systematic review may be too narrow, and the strict criteria for study inclusion may omit important information from the dissertation/thesis. Therefore, this essay discusses the definition of an LR is and methods to develop an LR in the context of an academic dissertation/thesis. Finally, we suggest a checklist to evaluate an LR.

WHAT IS A LITERATURE REVIEW IN A THESIS?

Conducting research and writing a dissertation/thesis translates rational thinking and enthusiasm ( 9 ). While a strong body of literature that instructs students on research methodology, data analysis and writing scientific papers exists, little guidance on performing LRs is available. The LR is a unique opportunity to assess and contrast various arguments and theories, not just summarize them. The research results should not be discussed within the LR, but the postgraduate student tends to write a comprehensive LR while reflecting on his or her own findings ( 10 ).

Many people believe that writing an LR is a lonely and linear process. Supervisors or the institutions assume that the Ph.D. student has mastered the relevant techniques and vocabulary associated with his/her subject and conducts a self-reflection about previously published findings. Indeed, while elaborating the LR, the student should aggregate diverse skills, which mainly rely on his/her own commitment to mastering them. Thus, less supervision should be required ( 11 ). However, the parameters described above might not currently be the case for many students ( 11 , 12 ), and the lack of formal and systematic training on writing LRs is an important concern ( 11 ).

An institutional environment devoted to active learning will provide students the opportunity to continuously reflect on LRs, which will form a dialogue between the postgraduate student and the current literature in a particular field ( 13 ). Postgraduate students will be interpreting studies by other researchers, and, according to Hart (1998) ( 3 ), the outcomes of the LR in a dissertation/thesis include the following:

- To identify what research has been performed and what topics require further investigation in a particular field of knowledge;

- To determine the context of the problem;

- To recognize the main methodologies and techniques that have been used in the past;

- To place the current research project within the historical, methodological and theoretical context of a particular field;

- To identify significant aspects of the topic;

- To elucidate the implications of the topic;

- To offer an alternative perspective;

- To discern how the studied subject is structured;

- To improve the student’s subject vocabulary in a particular field; and

- To characterize the links between theory and practice.

A sound LR translates the postgraduate student’s expertise in academic and scientific writing: it expresses his/her level of comfort with synthesizing ideas ( 11 ). The LR reveals how well the postgraduate student has proceeded in three domains: an effective literature search, the language domain, and critical writing.

Effective literature search

All students should be trained in gathering appropriate data for specific purposes, and information literacy skills are a cornerstone. These skills are defined as “an individual’s ability to know when they need information, to identify information that can help them address the issue or problem at hand, and to locate, evaluate, and use that information effectively” ( 14 ). Librarian support is of vital importance in coaching the appropriate use of Boolean logic (AND, OR, NOT) and other tools for highly efficient literature searches (e.g., quotation marks and truncation), as is the appropriate management of electronic databases.

Language domain

Academic writing must be concise and precise: unnecessary words distract the reader from the essential content ( 15 ). In this context, reading about issues distant from the research topic ( 16 ) may increase students’ general vocabulary and familiarity with grammar. Ultimately, reading diverse materials facilitates and encourages the writing process itself.

Critical writing

Critical judgment includes critical reading, thinking and writing. It supposes a student’s analytical reflection about what he/she has read. The student should delineate the basic elements of the topic, characterize the most relevant claims, identify relationships, and finally contrast those relationships ( 17 ). Each scientific document highlights the perspective of the author, and students will become more confident in judging the supporting evidence and underlying premises of a study and constructing their own counterargument as they read more articles. A paucity of integration or contradictory perspectives indicates lower levels of cognitive complexity ( 12 ).

Thus, while elaborating an LR, the postgraduate student should achieve the highest category of Bloom’s cognitive skills: evaluation ( 12 ). The writer should not only summarize data and understand each topic but also be able to make judgments based on objective criteria, compare resources and findings, identify discrepancies due to methodology, and construct his/her own argument ( 12 ). As a result, the student will be sufficiently confident to show his/her own voice .

Writing a consistent LR is an intense and complex activity that reveals the training and long-lasting academic skills of a writer. It is not a lonely or linear process. However, students are unlikely to be prepared to write an LR if they have not mastered the aforementioned domains ( 10 ). An institutional environment that supports student learning is crucial.

Different institutions employ distinct methods to promote students’ learning processes. First, many universities propose modules to develop behind the scenes activities that enhance self-reflection about general skills (e.g., the skills we have mastered and the skills we need to develop further), behaviors that should be incorporated (e.g., self-criticism about one’s own thoughts), and each student’s role in the advancement of his/her field. Lectures or workshops about LRs themselves are useful because they describe the purposes of the LR and how it fits into the whole picture of a student’s work. These activities may explain what type of discussion an LR must involve, the importance of defining the correct scope, the reasons to include a particular resource, and the main role of critical reading.

Some pedagogic services that promote a continuous improvement in study and academic skills are equally important. Examples include workshops about time management, the accomplishment of personal objectives, active learning, and foreign languages for nonnative speakers. Additionally, opportunities to converse with other students promotes an awareness of others’ experiences and difficulties. Ultimately, the supervisor’s role in providing feedback and setting deadlines is crucial in developing students’ abilities and in strengthening students’ writing quality ( 12 ).

HOW SHOULD A LITERATURE REVIEW BE DEVELOPED?

A consensus on the appropriate method for elaborating an LR is not available, but four main steps are generally accepted: defining the main topic, searching the literature, analyzing the results, and writing ( 6 ). We suggest a fifth step: reflecting on the information that has been written in previous publications ( Figure 2 ).

First step: Defining the main topic

Planning an LR is directly linked to the research main question of the thesis and occurs in parallel to students’ training in the three domains discussed above. The planning stage helps organize ideas, delimit the scope of the LR ( 11 ), and avoid the wasting of time in the process. Planning includes the following steps:

- Reflecting on the scope of the LR: postgraduate students will have assumptions about what material must be addressed and what information is not essential to an LR ( 13 , 18 ). Cooper’s Taxonomy of Literature Reviews 2 systematizes the writing process through six characteristics and nonmutually exclusive categories. The focus refers to the reviewer’s most important points of interest, while the goals concern what students want to achieve with the LR. The perspective assumes answers to the student’s own view of the LR and how he/she presents a particular issue. The coverage defines how comprehensive the student is in presenting the literature, and the organization determines the sequence of arguments. The audience is defined as the group for whom the LR is written.

- Designating sections and subsections: Headings and subheadings should be specific, explanatory and have a coherent sequence throughout the text ( 4 ). They simulate an inverted pyramid, with an increasing level of reflection and depth of argument.

- Identifying keywords: The relevant keywords for each LR section should be listed to guide the literature search. This list should mirror what Hart (1998) ( 3 ) advocates as subject vocabulary . The keywords will also be useful when the student is writing the LR since they guide the reader through the text.

- Delineating the time interval and language of documents to be retrieved in the second step. The most recently published documents should be considered, but relevant texts published before a predefined cutoff year can be included if they are classic documents in that field. Extra care should be employed when translating documents.

Second step: Searching the literature

The ability to gather adequate information from the literature must be addressed in postgraduate programs. Librarian support is important, particularly for accessing difficult texts. This step comprises the following components:

- Searching the literature itself: This process consists of defining which databases (electronic or dissertation/thesis repositories), official documents, and books will be searched and then actively conducting the search. Information literacy skills have a central role in this stage. While searching electronic databases, controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings, or MeSH, for the PubMed database) or specific standardized syntax rules may need to be applied.

In addition, two other approaches are suggested. First, a review of the reference list of each document might be useful for identifying relevant publications to be included and important opinions to be assessed. This step is also relevant for referencing the original studies and leading authors in that field. Moreover, students can directly contact the experts on a particular topic to consult with them regarding their experience or use them as a source of additional unpublished documents.

Before submitting a dissertation/thesis, the electronic search strategy should be repeated. This process will ensure that the most recently published papers will be considered in the LR.

- Selecting documents for inclusion: Generally, the most recent literature will be included in the form of published peer-reviewed papers. Assess books and unpublished material, such as conference abstracts, academic texts and government reports, are also important to assess since the gray literature also offers valuable information. However, since these materials are not peer-reviewed, we recommend that they are carefully added to the LR.

This task is an important exercise in time management. First, students should read the title and abstract to understand whether that document suits their purposes, addresses the research question, and helps develop the topic of interest. Then, they should scan the full text, determine how it is structured, group it with similar documents, and verify whether other arguments might be considered ( 5 ).

Third step: Analyzing the results

Critical reading and thinking skills are important in this step. This step consists of the following components:

- Reading documents: The student may read various texts in depth according to LR sections and subsections ( defining the main topic ), which is not a passive activity ( 1 ). Some questions should be asked to practice critical analysis skills, as listed below. Is the research question evident and articulated with previous knowledge? What are the authors’ research goals and theoretical orientations, and how do they interact? Are the authors’ claims related to other scholars’ research? Do the authors consider different perspectives? Was the research project designed and conducted properly? Are the results and discussion plausible, and are they consistent with the research objectives and methodology? What are the strengths and limitations of this work? How do the authors support their findings? How does this work contribute to the current research topic? ( 1 , 19 )

- Taking notes: Students who systematically take notes on each document are more readily able to establish similarities or differences with other documents and to highlight personal observations. This approach reinforces the student’s ideas about the next step and helps develop his/her own academic voice ( 1 , 13 ). Voice recognition software ( 16 ), mind maps ( 5 ), flowcharts, tables, spreadsheets, personal comments on the referenced texts, and note-taking apps are all available tools for managing these observations, and the student him/herself should use the tool that best improves his/her learning. Additionally, when a student is considering submitting an LR to a peer-reviewed journal, notes should be taken on the activities performed in all five steps to ensure that they are able to be replicated.

Fourth step: Writing

The recognition of when a student is able and ready to write after a sufficient period of reading and thinking is likely a difficult task. Some students can produce a review in a single long work session. However, as discussed above, writing is not a linear process, and students do not need to write LRs according to a specific sequence of sections. Writing an LR is a time-consuming task, and some scholars believe that a period of at least six months is sufficient ( 6 ). An LR, and academic writing in general, expresses the writer’s proper thoughts, conclusions about others’ work ( 6 , 10 , 13 , 16 ), and decisions about methods to progress in the chosen field of knowledge. Thus, each student is expected to present a different learning and writing trajectory.

In this step, writing methods should be considered; then, editing, citing and correct referencing should complete this stage, at least temporarily. Freewriting techniques may be a good starting point for brainstorming ideas and improving the understanding of the information that has been read ( 1 ). Students should consider the following parameters when creating an agenda for writing the LR: two-hour writing blocks (at minimum), with prespecified tasks that are possible to complete in one section; short (minutes) and long breaks (days or weeks) to allow sufficient time for mental rest and reflection; and short- and long-term goals to motivate the writing itself ( 20 ). With increasing experience, this scheme can vary widely, and it is not a straightforward rule. Importantly, each discipline has a different way of writing ( 1 ), and each department has its own preferred styles for citations and references.

Fifth step: Reflecting on the writing

In this step, the postgraduate student should ask him/herself the same questions as in the analyzing the results step, which can take more time than anticipated. Ambiguities, repeated ideas, and a lack of coherence may not be noted when the student is immersed in the writing task for long periods. The whole effort will likely be a work in progress, and continuous refinements in the written material will occur once the writing process has begun.

LITERATURE REVIEW CHECKLIST

In contrast to review papers, the LR of a dissertation/thesis should not be a standalone piece or work. Instead, it should present the student as a scholar and should maintain the interest of the audience in how that dissertation/thesis will provide solutions for the current gaps in a particular field.

A checklist for evaluating an LR is convenient for students’ continuous academic development and research transparency: it clearly states the desired achievements for the LR of a dissertation/thesis. Here, we present an LR checklist developed from an LR scoring rubric ( 11 ). For a critical analysis of an LR, we maintain the five categories but offer twelve criteria that are not scaled ( Figure 3 ). The criteria all have the same importance and are not mutually exclusive.

First category: Coverage

1. justified criteria exist for the inclusion and exclusion of literature in the review.

This criterion builds on the main topic and areas covered by the LR ( 18 ). While experts may be confident in retrieving and selecting literature, postgraduate students must convince their audience about the adequacy of their search strategy and their reasons for intentionally selecting what material to cover ( 11 ). References from different fields of knowledge provide distinct perspective, but narrowing the scope of coverage may be important in areas with a large body of existing knowledge.

Second category: Synthesis

2. a critical examination of the state of the field exists.

A critical examination is an assessment of distinct aspects in the field ( 1 ) along with a constructive argument. It is not a negative critique but an expression of the student’s understanding of how other scholars have added to the topic ( 1 ), and the student should analyze and contextualize contradictory statements. A writer’s personal bias (beliefs or political involvement) have been shown to influence the structure and writing of a document; therefore, the cultural and paradigmatic background guide how the theories are revised and presented ( 13 ). However, an honest judgment is important when considering different perspectives.

3. The topic or problem is clearly placed in the context of the broader scholarly literature

The broader scholarly literature should be related to the chosen main topic for the LR ( how to develop the literature review section). The LR can cover the literature from one or more disciplines, depending on its scope, but it should always offer a new perspective. In addition, students should be careful in citing and referencing previous publications. As a rule, original studies and primary references should generally be included. Systematic and narrative reviews present summarized data, and it may be important to cite them, particularly for issues that should be understood but do not require a detailed description. Similarly, quotations highlight the exact statement from another publication. However, excessive referencing may disclose lower levels of analysis and synthesis by the student.

4. The LR is critically placed in the historical context of the field

Situating the LR in its historical context shows the level of comfort of the student in addressing a particular topic. Instead of only presenting statements and theories in a temporal approach, which occasionally follows a linear timeline, the LR should authentically characterize the student’s academic work in the state-of-art techniques in their particular field of knowledge. Thus, the LR should reinforce why the dissertation/thesis represents original work in the chosen research field.

5. Ambiguities in definitions are considered and resolved

Distinct theories on the same topic may exist in different disciplines, and one discipline may consider multiple concepts to explain one topic. These misunderstandings should be addressed and contemplated. The LR should not synthesize all theories or concepts at the same time. Although this approach might demonstrate in-depth reading on a particular topic, it can reveal a student’s inability to comprehend and synthesize his/her research problem.

6. Important variables and phenomena relevant to the topic are articulated

The LR is a unique opportunity to articulate ideas and arguments and to purpose new relationships between them ( 10 , 11 ). More importantly, a sound LR will outline to the audience how these important variables and phenomena will be addressed in the current academic work. Indeed, the LR should build a bidirectional link with the remaining sections and ground the connections between all of the sections ( Figure 1 ).

7. A synthesized new perspective on the literature has been established

The LR is a ‘creative inquiry’ ( 13 ) in which the student elaborates his/her own discourse, builds on previous knowledge in the field, and describes his/her own perspective while interpreting others’ work ( 13 , 17 ). Thus, students should articulate the current knowledge, not accept the results at face value ( 11 , 13 , 17 ), and improve their own cognitive abilities ( 12 ).

Third category: Methodology

8. the main methodologies and research techniques that have been used in the field are identified and their advantages and disadvantages are discussed.

The LR is expected to distinguish the research that has been completed from investigations that remain to be performed, address the benefits and limitations of the main methods applied to date, and consider the strategies for addressing the expected limitations described above. While placing his/her research within the methodological context of a particular topic, the LR will justify the methodology of the study and substantiate the student’s interpretations.

9. Ideas and theories in the field are related to research methodologies

The audience expects the writer to analyze and synthesize methodological approaches in the field. The findings should be explained according to the strengths and limitations of previous research methods, and students must avoid interpretations that are not supported by the analyzed literature. This criterion translates to the student’s comprehension of the applicability and types of answers provided by different research methodologies, even those using a quantitative or qualitative research approach.

Fourth category: Significance

10. the scholarly significance of the research problem is rationalized.

The LR is an introductory section of a dissertation/thesis and will present the postgraduate student as a scholar in a particular field ( 11 ). Therefore, the LR should discuss how the research problem is currently addressed in the discipline being investigated or in different disciplines, depending on the scope of the LR. The LR explains the academic paradigms in the topic of interest ( 13 ) and methods to advance the field from these starting points. However, an excess number of personal citations—whether referencing the student’s research or studies by his/her research team—may reflect a narrow literature search and a lack of comprehensive synthesis of ideas and arguments.

11. The practical significance of the research problem is rationalized

The practical significance indicates a student’s comprehensive understanding of research terminology (e.g., risk versus associated factor), methodology (e.g., efficacy versus effectiveness) and plausible interpretations in the context of the field. Notably, the academic argument about a topic may not always reflect the debate in real life terms. For example, using a quantitative approach in epidemiology, statistically significant differences between groups do not explain all of the factors involved in a particular problem ( 21 ). Therefore, excessive faith in p -values may reflect lower levels of critical evaluation of the context and implications of a research problem by the student.

Fifth category: Rhetoric

12. the lr was written with a coherent, clear structure that supported the review.

This category strictly relates to the language domain: the text should be coherent and presented in a logical sequence, regardless of which organizational ( 18 ) approach is chosen. The beginning of each section/subsection should state what themes will be addressed, paragraphs should be carefully linked to each other ( 10 ), and the first sentence of each paragraph should generally summarize the content. Additionally, the student’s statements are clear, sound, and linked to other scholars’ works, and precise and concise language that follows standardized writing conventions (e.g., in terms of active/passive voice and verb tenses) is used. Attention to grammar, such as orthography and punctuation, indicates prudence and supports a robust dissertation/thesis. Ultimately, all of these strategies provide fluency and consistency for the text.

Although the scoring rubric was initially proposed for postgraduate programs in education research, we are convinced that this checklist is a valuable tool for all academic areas. It enables the monitoring of students’ learning curves and a concentrated effort on any criteria that are not yet achieved. For institutions, the checklist is a guide to support supervisors’ feedback, improve students’ writing skills, and highlight the learning goals of each program. These criteria do not form a linear sequence, but ideally, all twelve achievements should be perceived in the LR.

CONCLUSIONS

A single correct method to classify, evaluate and guide the elaboration of an LR has not been established. In this essay, we have suggested directions for planning, structuring and critically evaluating an LR. The planning of the scope of an LR and approaches to complete it is a valuable effort, and the five steps represent a rational starting point. An institutional environment devoted to active learning will support students in continuously reflecting on LRs, which will form a dialogue between the writer and the current literature in a particular field ( 13 ).

The completion of an LR is a challenging and necessary process for understanding one’s own field of expertise. Knowledge is always transitory, but our responsibility as scholars is to provide a critical contribution to our field, allowing others to think through our work. Good researchers are grounded in sophisticated LRs, which reveal a writer’s training and long-lasting academic skills. We recommend using the LR checklist as a tool for strengthening the skills necessary for critical academic writing.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Leite DFB has initially conceived the idea and has written the first draft of this review. Padilha MAS and Cecatti JG have supervised data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read the draft and agreed with this submission. Authors are responsible for all aspects of this academic piece.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all of the professors of the ‘Getting Started with Graduate Research and Generic Skills’ module at University College Cork, Cork, Ireland, for suggesting and supporting this article. Funding: DFBL has granted scholarship from Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) to take part of her Ph.D. studies in Ireland (process number 88881.134512/2016-01). There is no participation from sponsors on authors’ decision to write or to submit this manuscript.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

1 The questions posed in systematic reviews usually follow the ‘PICOS’ acronym: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study design.

2 In 1988, Cooper proposed a taxonomy that aims to facilitate students’ and institutions’ understanding of literature reviews. Six characteristics with specific categories are briefly described: Focus: research outcomes, research methodologies, theories, or practices and applications; Goals: integration (generalization, conflict resolution, and linguistic bridge-building), criticism, or identification of central issues; Perspective: neutral representation or espousal of a position; Coverage: exhaustive, exhaustive with selective citations, representative, central or pivotal; Organization: historical, conceptual, or methodological; and Audience: specialized scholars, general scholars, practitioners or policymakers, or the general public.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, what is your plagiarism score.

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2022

- Volume 16 , pages 2577–2595, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sascha Kraus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4886-7482 1 , 2 ,

- Matthias Breier 3 ,

- Weng Marc Lim 4 , 8 , 22 ,

- Marina Dabić 5 , 6 ,

- Satish Kumar 7 , 8 ,

- Dominik Kanbach 9 , 10 ,

- Debmalya Mukherjee 11 ,

- Vincenzo Corvello 12 ,

- Juan Piñeiro-Chousa 13 ,

- Eric Liguori 14 ,

- Daniel Palacios-Marqués 15 ,

- Francesco Schiavone 16 , 17 ,

- Alberto Ferraris 18 , 21 ,

- Cristina Fernandes 19 , 20 &

- João J. Ferreira 19

65k Accesses

265 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Review articles or literature reviews are a critical part of scientific research. While numerous guides on literature reviews exist, these are often limited to the philosophy of review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures, triggering non-parsimonious reporting and confusion due to overlapping similarities. To address the aforementioned limitations, we adopt a pragmatic approach to demystify and shape the academic practice of conducting literature reviews. We concentrate on the types, focuses, considerations, methods, and contributions of literature reviews as independent, standalone studies. As such, our article serves as an overview that scholars can rely upon to navigate the fundamental elements of literature reviews as standalone and independent studies, without getting entangled in the complexities of review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Patrik Aspers & Ugo Corte

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Clara Busse & Ella August

Qualitative Research: Ethical Considerations

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A literature review – or a review article – is “a study that analyzes and synthesizes an existing body of literature by identifying, challenging, and advancing the building blocks of a theory through an examination of a body (or several bodies) of prior work (Post et al. 2020 , p. 352). Literature reviews as standalone pieces of work may allow researchers to enhance their understanding of prior work in their field, enabling them to more easily identify gaps in the body of literature and potential avenues for future research. More importantly, review articles may challenge established assumptions and norms of a given field or topic, recognize critical problems and factual errors, and stimulate future scientific conversations around that topic. Literature reviews Footnote 1 come in many different formats and purposes:

Some review articles conduct a critical evaluation of the literature, whereas others elect to adopt a more exploratory and descriptive approach.

Some reviews examine data, methodologies, and findings, whereas others look at constructs, themes, and theories.

Some reviews provide summaries by holistically synthesizing the existing research on a topic, whereas others adopt an integrative approach by assessing related and interdisciplinary work.

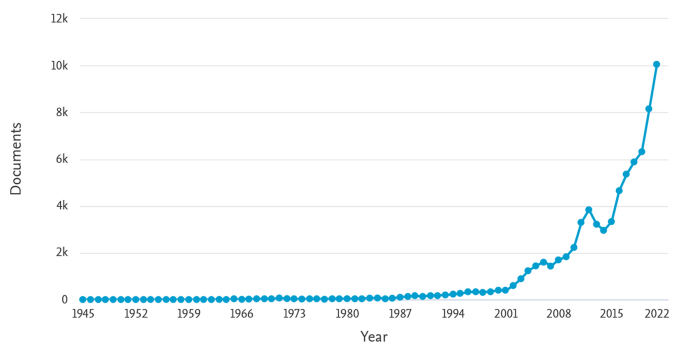

The number of review articles published as independent or standalone studies has been increasing over time. According to Scopus (i.e., search database ), reviews (i.e., document type ) were first published in journals (i.e., source type ) as independent studies in 1945, and they subsequently appeared in three digits yearly from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, four digits yearly from the early 2000s to the late 2010s, and five digits in the year 2021 (Fig. 1 ). This increase is indicative that reviewers and editors in business and management research alike see value and purpose in review articles to such a level that they are now commonly accepted as independent, standalone studies. This development is also reflected in the fact that some academic journals exclusively publish review articles (e.g., the Academy of Management Annals , or the International Journal of Management Reviews ), and journals publishing in various fields often have special issues dedicated to literature reviews on certain topic areas (e.g., the Journal of Management and the Journal of International Business Studies ).

Full-year publication trend of review articles on Scopus (1945–2021)

One of the most important prerequisites of a high-quality review article is that the work follows an established methodology, systematically selects and analyzes articles, and periodically covers the field to identify latest developments (Snyder 2019 ). Additionally, it needs to be reproducible, well-evidenced, and transparent, resulting in a sample inclusive of all relevant and appropriate studies (Gusenbauer and Haddaway 2020; Hansen et al. 2021 ). This observation is in line with Palmatier et al. ( 2018 ), who state that review articles provide an important synthesis of findings and perspectives in a given body of knowledge. Snyder ( 2019 ) also reaffirmed this rationale, pointing out that review articles have the power to answer research questions beyond that which can be achieved in a single study. Ultimately, readers of review articles stand to gain a one-stop, state-of-the-art synthesis (Lim et al. 2022a ; Popli et al. 2022) that encapsulates critical insights through the process of re-interpreting, re-organizing, and re-connecting a body knowledge (Fan et al. 2022 ).

There are many reasons to conduct review articles. Kraus et al. ( 2020 ) explicitly mention the benefits of conducting systematic reviews by declaring that they often represent the first step in the context of larger research projects, such as doctoral dissertations. When carrying out work of this kind, it is important that a holistic overview of the current state of literature is achieved and embedded into a proper synthesis. This allows researchers to pinpoint relevant research gaps and adequately fit future conceptual or empirical studies into the state of the academic discussion (Kraus et al., 2021 ). A review article as an independent or standalone study is a viable option for any academic – especially young scholars, such as doctoral candidates – who wishes to delve into a specific topic for which a (recent) review article is not available.

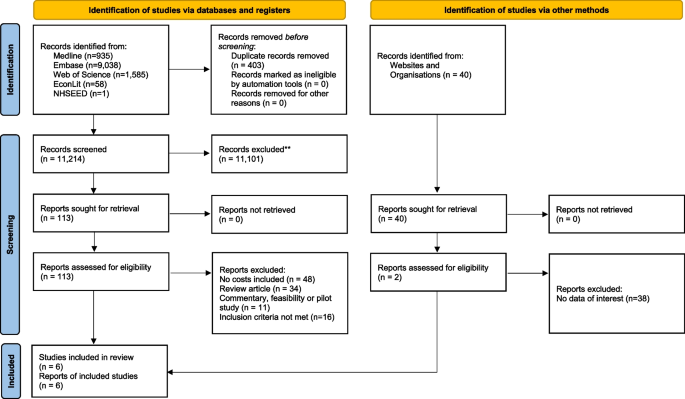

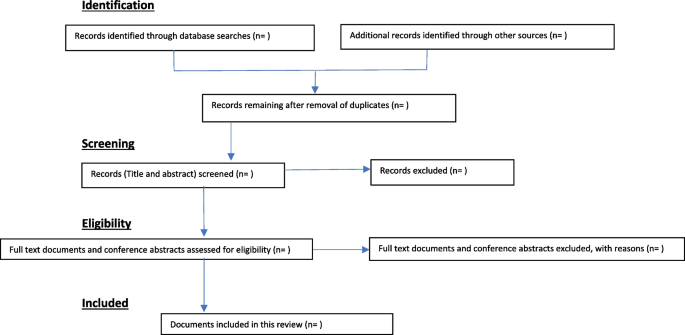

The process of conducting a review article can be challenging, especially for novice scholars (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic 2015 ). Therefore, it is not surprising that numerous guides have been written in an attempt to improve the quality of review studies and support emerging scholars in their endeavors to have their work published. These guides for conducting review articles span a variety of academic fields, such as engineering education (Borrego et al. 2014 ), health sciences (Cajal et al. 2020 ), psychology (Laher and Hassem 2020 ), supply chain management (Durach et al. 2017 ), or business and entrepreneurship (Kraus et al. 2020 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ) – the latter were among the first scholars to recognize the need to educate business/management scholars on the roles of review studies in assembling, ascertaining, and assessing the intellectual territory of a specific knowledge domain. Furthermore, they shed light on the stages (i.e., planning the review, conducting the review, reporting, and dissemination) and phases (i.e., identifying the need for a review, preparation of a proposal for a review, development of a review protocol, identification of research, selection of studies, study quality assessment, data extraction and monitoring progress, data synthesis, the report and recommendations, and getting evidence into practice) of conducting a systematic review. Other scholars have either adapted and/or developed new procedures (Kraus et al. 2020 ; Snyder 2019 ) or established review protocols such as the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher et al. 2015 ). The latter provides a checklist that improves transparency and reproducibility, thus reducing questionable research practices. The declarative and procedural knowledge of a checklist allows users to derive value from (and, in some cases, produce) methodological literature reviews.

Two distinct and critical gaps or issues provide impetus for our article. First, while the endeavors of the named scholars are undoubtedly valuable contributions, they often encourage other scholars to explain the methodology of their review studies in a non-parsimonious way ( 1st issue ). This can become problematic if this information distracts and deprives scholars from providing richer review findings, particularly in instances in which publication outlets impose a strict page and/or word limit. More often than not, the early parts (i.e., stages/phases, such as needs, aims, and scope) of these procedures or protocols are explained in the introduction, but they tend to be reiterated in the methodology section due to the prescription of these procedures or protocols. Other parts of these procedures or protocols could also be reported more parsimoniously, for example, by filtering out documents, given that scientific databases (such as Scopus or Web of Science ) have since been upgraded to allow scholars to select and implement filtering criteria when conducting a search (i.e., criterion-by-criterion filtering may no longer be necessary). More often than not, the procedures or protocols of review studies can be signposted (e.g., bracket labeling) and disclosed in a sharp and succinct manner while maintaining transparency and replicability.

Other guides have been written to introduce review nomenclatures (i.e., names/naming) and their equivalent philosophical underpinnings. Palmatier et al. ( 2018 ) introduced three clearly but broadly defined nomenclatures of literature reviews as independent studies: domain-based reviews, theory-based reviews, and method-based reviews. However, such review nomenclatures can be confusing due to their overlapping similarities ( 2nd issue ). For example, Lim et al. ( 2022a ) highlighted their observation that the review nomenclatures associated with domain-based reviews could also be used for theory-based and method-based reviews.

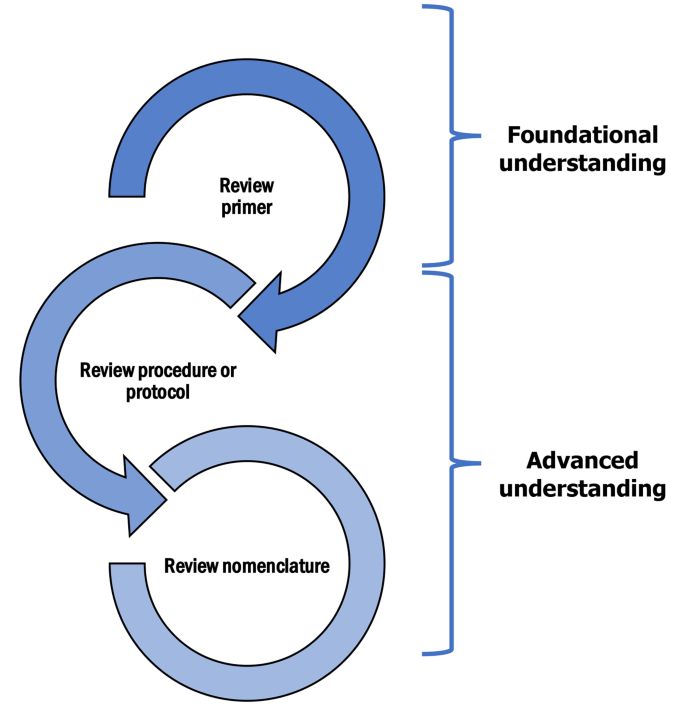

The two aforementioned issues – i.e., the lack of a parsimonious understanding and the reporting of the review methodology , and the confusion emerging from review nomenclatures – are inarguably the unintended outcomes of diving into an advanced (i.e., higher level) understanding of literature review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures from a philosophical perspective (i.e., underpinnings) without a foundational (i.e., basic level) understanding of the fundamental (i.e., core) elements of literature reviews from a pragmatic perspective. Our article aims to shed light on these issues and hopes to provide clarity for future scholarly endeavors.

Having a foundational understanding of literature reviews as independent studies is (i) necessary when addressing the aforementioned issues; (ii) important in reconciling and scaffolding our understanding, and (iii) relevant and timely due to the proliferation of literature reviews as independent studies. To contribute a solution toward addressing this gap , we aim to demystify review articles as independent studies from a pragmatic standpoint (i.e., practicality). To do so, we deliberately (i) move away from review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures, and (ii) invest our attention in developing a parsimonious, scaffolded understanding of the fundamental elements (i.e., types, focuses, considerations, methods, and contributions) of review articles as independent studies.

Three contributions distinguish our article. It is worth noting that pragmatic guides (i.e., foundational knowledge), such as the present one, are not at odds with extant philosophical guides (i.e., advanced knowledge), but rather they complement them. Having a foundational knowledge of the fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies is valuable , as it can help scholars to (i) gain a good grasp of the fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies ( 1st contribution ), and (ii) mindfully adopt or adapt existing review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures to better suit the circumstances of their reviews (e.g., choosing and developing a well-defined review nomenclature, and choosing and reporting on review considerations and steps more parsimoniously) ( 2nd contribution ). Therefore, this pragmatic guide serves as (iii) a foundational article (i.e., preparatory understanding) for literature reviews as independent studies ( 3rd contribution ). Following this, extant guides using a philosophical approach (i.e., advanced understanding) could be relied upon to make informed review decisions (e.g., adoption, adaptation) in response to the conventions of extant review procedures, protocols, and nomenclatures (Fig. 2 ).

Foundational and advanced understanding of literature reviews as independent studies

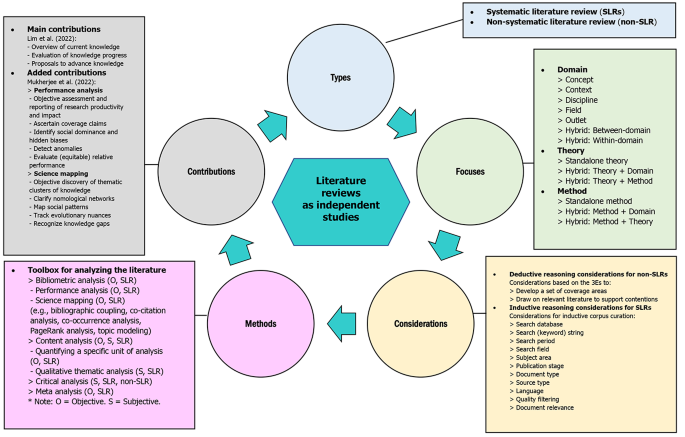

2 Fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies

A foundational understanding of literature reviews as independent studies can be acquired through the appreciation of five fundamental elements – i.e., types, focuses, considerations, methods, and contributions – which are illustrated in Fig. 3 and summarized in the following sections.

Fundamental elements of literature reviews as independent studies

There are two types of literature reviews as independent studies: systematic literature reviews ( SLRs ) and non-systematic literature reviews ( non-SLRs ). It is important to recognize that SLRs and non-SLRs are not review nomenclatures (i.e., names/naming) but rather review types (i.e., classifications).

In particular, SLRs are reviews carried out in a systematic way using an adopted or adapted procedure or protocol to guide data curation and analysis, thus enabling transparent disclosure and replicability (Lim et al. 2022a ; Kraus et al. 2020 ). Therefore, any review nomenclature guided by a systematic methodology is essentially an SLR. The origin of this type of literature review can be traced back to the evidence-based medicine movement in the early 1990s, with the objective being to overcome the issue of inconclusive findings in studies for medical treatments (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic 2015 ).

In contrast, non-SLRs are reviews conducted without any systematic procedure or protocol; instead, they weave together relevant literature based on the critical evaluations and (subjective) choices of the author(s) through a process of discovery and critique (e.g., pointing out contradictions and questioning assertions or beliefs); they are shaped by the exposure, expertise, and experience (i.e., the “3Es” in judgement calls) of the author(s). Therefore, non-SLRs are essentially critical reviews of the literature (Lim and Weissmann 2021 ).

2.2 Focuses

Unlike Palmatier et al. ( 2018 ) who considered domain-based reviews, theory-based reviews, and method-based reviews as review nomenclatures, we consider domain , theory , and method as three substantive focuses that can take center stage in literature reviews as independent studies. This is in line with our attempt to move away from review nomenclatures when providing a foundational understanding of literature reviews as independent studies.

A review that is domain-focused can examine: (i) a concept (e.g., customer engagement; Lim et al. 2022b ; digital transformation; Kraus et al. 2021 ; home sharing; Lim et al. 2021 ; sharing economy; Lim 2020 ), (ii) a context (e.g., India; Mukherjee et al. 2022a ), (iii) a discipline (e.g., entrepreneurship; Ferreira et al. 2015 ; international business; Ghauri et al. 2021 ), (iv) a field (e.g., family business; Lahiri et al. 2020 ; Rovelli et al. 2021 ; female entrepreneurship; Ojong et al. 2021 ), or (v) an outlet (e.g., Journal of Business Research ; Donthu et al. 2020 ; Management International Review ; Mukherjee et al. 2021 ; Review of Managerial Science ; Mas-Tur et al. 2020 ), which typically offer broad, overarching insights.

Domain-focused hybrids , such as the between-domain hybrid (e.g., concept-discipline hybrid, such as digital transformation in business and management; Kraus et al. 2022 ; religion in business and entrepreneurship; Kumar et al. 2022a ; personality traits in entrepreneurship; Salmony and Kanbach 2022 ; and policy implications in HR and OB research; Aguinis et al., 2022 ) and the within-domain hybrid (e.g., the concept-concept hybrid, such as customer engagement and social media; Lim and Rasul 2022 ; and global business and organizational excellence; Lim 2022 ; and the discipline-discipline hybrid, such as neuromarketing; Lim 2018 ) are also common as they can provide finer-grained insights.

A review that is theory-focused can explore a standalone theory (e.g., theory of planned behavior; Duan and Jiang 2008 ), as well as a theory in conjunction with a domain , such as the concept-theory hybrid (e.g., behavioral control and theory of planned behavior; Lim and Weissmann 2021 ) and the theory-discipline hybrid (e.g., theory of planned behavior in hospitality, leisure, and tourism; Ulker-Demirel and Ciftci 2020 ), or a theory in conjunction with a method (e.g., theory of planned behavior and structural equation modeling).

A review that is method-focused can investigate a standalone method (e.g., structural equation modeling; Deng et al. 2018 ) or a method in conjunction with a domain , such as the method-discipline hybrid (e.g., fsQCA in business and management; Kumar et al. 2022b ).

2.3 Planning the review, critical considerations, and data collection

The considerations required for literature reviews as independent studies depend on their type: SLRs or non-SLRs.

For non-SLRs, scholars often rely on the 3Es (i.e., exposure, expertise, and experience) to provide a critical review of the literature. Scholars who embark on non-SLRs should be well versed with the literature they are dealing with. They should know the state of the literature (e.g., debatable, underexplored, and well-established knowledge areas) and how it needs to be deciphered (e.g., tenets and issues) and approached (e.g., reconciliation proposals and new pathways) to advance theory and practice. In this regard, non-SLRs follow a deductive reasoning approach, whereby scholars initially develop a set of coverage areas for reviewing a domain, theory, or method and subsequently draw on relevant literature to shed light and support scholarly contentions in each area.

For SLRs, scholars often rely on a set of criteria to provide a well-scoped (i.e., breadth and depth), structured (i.e., organized aspects), integrated (i.e., synthesized evidence) and interpreted/narrated (i.e., describing what has happened, how and why) systematic review of the literature. Footnote 2 In this regard, SLRs follow an inductive reasoning approach, whereby a set of criteria is established and implemented to develop a corpus of scholarly documents that scholars can review. They can then deliver a state-of-the-art overview, as well as a future agenda for a domain, theory, or method. Such criteria are often listed in philosophical guides on SLR procedures (e.g., Kraus et al. 2020 ; Snyder 2019 ) and protocols (e.g., PRISMA), and they may be adopted/adapted with justifications Footnote 3 . Based on their commonalities they can be summarized as follows:

Search database (e.g., “Scopus” and/or “Web of Science”) can be defined based on justified evidence (e.g., by the two being the largest scientific databases of scholarly articles that can provide on-demand bibliographic data or records; Pranckutė 2021 ). To avoid biased outcomes due to the scope covered by the selected database, researchers could utilize two or more different databases (Dabić et al. 2021 ).

Search keywords may be developed by reading scholarly documents and subsequently brainstorming with experts. The expanding number of databases, journals, periodicals, automated approaches, and semi-automated procedures that use text mining and machine learning can offer researchers the ability to source new, relevant research and forecast the citations of influential studies. This enables them to determine further relevant articles.

Boolean operators (e.g., AND, OR) should be strategically used in developing the string of search keywords (e.g., “engagement” AND “customer” OR “consumer” OR “business”). Furthermore, the correct and precise application of quotation marks is important but is very frequently sidestepped, resulting in incorrect selection processes and differentiated results.

Search period (e.g., between a specified period [e.g., 2000 to 2020] or up to the latest full year at the time or writing [e.g., up to 2021]) can be defined based on the justified scope of study (e.g., contemporary evolution versus historical trajectory).

Search field (e.g., “article title, abstract, keywords”) can be defined based on justified assumptions (e.g., it is assumed that the focus of relevant documents will be mentioned in the article title, abstract, and/or keywords).

Subject area (e.g., “business, management, and accounting”) can be defined based on justified principles (e.g., the focus of the review is on the marketing discipline, which is located under the “business, management, and accounting” subject area in Scopus).

Publication stage (e.g., “final”) can be defined based on justified grounds (e.g., enabling greater accuracy in replication).

Document type (e.g., “article” and/or “review”), which reflects the type of scientific/practical contributions (e.g., empirical, synthesis, thought), can be defined based on justified rationales (e.g., articles selected because they are peer-reviewed; editorials not selected because they are not peer-reviewed).

Source type (e.g., “journal”) can be defined based on justified reasons (e.g., journals selected because they publish finalized work; conference proceedings not selected because they are work in progress, and in business/management, they are usually not being considered as full-fledged “publications”).

Language (e.g., “English”) can be determined based on justified limitations (e.g., nowadays, there are not many reasons to use another language besides the academic lingua franca English). Different spellings should also be considered, as the literature may contain both American and British spelling variants (e.g., organization and organisation). Truncation and wildcards in searches are recommended to capture both sets of spellings. It is important to note that each database varies in its symbology.

Quality filtering (e.g., “A*” and “A” or “4*”, “4”, and “3”) can be defined based on justified motivations (e.g., the goal is to unpack the most originally and rigorously produced knowledge, which is the hallmark of premier journals, such as those ranked “A*” and “A” by the Australian Business Deans Council [ABDC] Journal Quality List [JQL] and rated “4*”, “4”, and “3” by the Chartered Association of Business Schools [CABS] Academic Journal Guide [AJG]).

Document relevance (i.e., within the focus of the review) can be defined based on justified judgement (e.g., for a review focusing on customer engagement, articles that mention customer engagement as a passing remark without actually investigating it would be excluded).

Others: Screening process should be accomplished by beginning with the deduction of duplicate results from other databases, tracked using abstract screening to exclude unfitting studies, and ending with the full-text screening of the remaining documents.

Others: Exclusion-inclusion criteria interpretation of the abstracts/articles is obligatory when deciding whether or not the articles dealt with the matter. This step could involve removing a huge percentage of initially recognized articles.

Others: Codebook building pertains to the development of a codebook of the main descriptors within a specific field. An inductive approach can be followed and, in this case, descriptors are not established beforehand. Instead, they are established through the analysis of the articles’ content. This procedure is made up of several stages: (i) the extraction of important content from titles, abstracts, and keywords; (ii) the classification of this content to form a reduced list of the core descriptors; and (iii) revising the codebook in iterations and combining similar categories, thus developing a short list of descriptors (López-Duarte et al. 2016 , p. 512; Dabić et al. 2015 ; Vlacic et al. 2021 ).

2.4 Methods

Various methods are used to analyze the pertinent literature. Often, scholars choose a method for corpus analysis before corpus curation. Knowing the analytical technique beforehand is useful, as it allows researchers to acquire and prepare the right data in the right format. This typically occurs when scholars have decided upon and justified pursuing a specific review nomenclature upfront (e.g., bibliometric reviews) based on the problem at hand (e.g., broad domain [outlet] with a large corpus [thousands of articles], such as a premier journal that has been publishing for decades) (Donthu et al. 2021 ). However, this may not be applicable in instances where (i) scholars do not curate a corpus of articles (non-SLRs), and (ii) scholars only know the size of the corpus of articles once that corpus is curated (SLRs). Therefore, scholars may wish to decide on a method of analyzing the literature depending on (i) whether they rely on a corpus of articles (i.e., yes or no), and (ii) the size of the corpus of articles that they rely on to review the literature (i.e., n = 0 to ∞).

When analytical techniques (e.g., bibliometric analysis, critical analysis, meta-analysis) are decoupled from review nomenclatures (e.g., bibliometric reviews, critical reviews, meta-analytical reviews), we uncover a toolbox of the following methods for use when analyzing the literature:

Bibliometric analysis measures the literature and processes data by using algorithm, arithmetic, and statistics to analyze, explore, organize, and investigate large amounts of data. This enables scholars to identify and recognize potential “hidden patterns” that could help them during the literature review process. Bibliometrics allows scholars to objectively analyze a large corpus of articles (e.g., high hundreds or more) using quantitative techniques (Donthu et al. 2021 ). There are two overarching categories for bibliometric analysis: performance analysis and science mapping. Performance analysis enables scholars to assess the productivity (publication) and impact (citation) of the literature relating to a domain, method, or theory using various quantitative metrics (e.g., average citations per publication or year, h -index, g -index, i -index). Science mapping grants scholars the ability to map the literature in that domain, method, or theory based on bibliographic data (e.g., bibliographic coupling generates thematic clusters based on similarities in shared bibliographic data [e.g., references] among citing articles; co-citation analysis generates thematic clusters based on commonly cited articles; co-occurrence analysis generates thematic clusters based on bibliographic data [e.g., keywords] that commonly appear together; PageRank analysis generates thematic clusters based on articles that are commonly cited in highly cited articles; and topic modeling generates thematic clusters based on the natural language processing of bibliographic data [e.g., article title, abstract, and keywords]). Footnote 4 Given the advancement in algorithms and technology, reviews using bibliometric analysis are considered to be smart (Kraus et al. 2021 ) and technologically-empowered (Kumar et al. 2022b ) SLRs, in which a review has harnessed the benefits of (i) the machine learning of the bibliographic data of scholarly research from technologically-empowered scientific databases, and (ii) big data analytics involving various science mapping techniques (Kumar et al. 2022c ).