- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

AI for Essay Writing — Exploring Top 10 Essay Writers

Table of Contents

Let’s admit it — essay writing is quite a challenging task for students. Especially with the stringent deadlines, conducting research, writing , editing, and addressing to-and-fro reviews — consumes a whole lot of time and often becomes stressful. Therefore, students are always on the lookout for tools that speed up the essay writing process.

And that’s when AI writing tools make their debut! Using the best AI for essay writing makes the lives of students much easier by automatically generating the essay for them.

The rise in the popularity of artificial intelligence technology and deep learning has paved the way for the numerous AI writer tools available today. To help you understand the different types of AI tools and their benefits, we’ve uncovered the features of the top 10 AI essay generators in this article.

Let’s explore the tools and learn how they are transforming the tedious task of essay writing!

What is essay writing?

Essay writing is a part of academic writing that emphasizes formulating an idea or argument. The main objective of academic essay writing is to present a well-reasoned argument or idea. Evidence, analysis, and interpretation are the three major components of essay writing . It should have a logical structure to support the argument or idea of the essay so that it communicates clearly and concisely.

What is an AI essay writer?

AI essay writers is a tool that is designed to help students generate essays using machine learning techniques. They can be used to generate a full essay or generate a few parts of the essay, for example, essay titles, introduction, conclusion, etc.

Why should researchers use AI essay generators?

There are infinite benefits to using AI tools for writing unique essays, especially for researchers or students. Here are a few of them —

1. Saves time

Using best AI for essay writing has its own benefits. Students can take care of the research process while these AI tools write the essays for them. Be it an essay topic or a full-length essay generation, it saves a bunch of students' time.

2. Boosts productivity

Writing is a tedious task especially when you want to write an essay about a novel topic, that writer’s block starts haunting and your productivity gets affected. But, with AI, it’s the other way around and increases productivity by quickly generating the essays for you.

3. Enhances writing skills — Vocabulary and Style

Adopting the best AI essay writing AI tool not only help with creating essays but also help us hone our writing skills by giving proper suggestions about grammar, sentence structure, tone, style, and word choice.

4. Reduces stress

Students often undergo a lot of pressure and stress because of deadlines and submissions. With the best AI essay generator, they help you write essays smarter thereby reducing stress and fear in no time.

5. Facilitates multidisciplinary research

AI essay writing tools foster interdisciplinary study through their ability to scan and combine knowledge from multiple domains. That way, it helps us quickly get a grasp of new subjects or topics without a heavy-lifting process.

6. Cost-effective

Most of the AI essay writing tools have lower pricing and also allow certain discounts for students. So, it is also a cost-effective approach to use AI writing tools.

The Top AI Essay Writing Tools and Their Features

Several AI essay writers are available based on the types of essays one would want to generate. Now, let's quickly understand the top 10 AI writing tools that generate essays within just a few minutes.

1. PerfectEssayWriter.ai

It is one of the best AI for essay writing that not only creates an essay but also comes up with advanced features including plagiarism detection, auto-referencing, and contextual analysis. As a result, it generates coherent essays that are well-researched and properly cited. It is best recommended for creating academic essays and essay outlines.

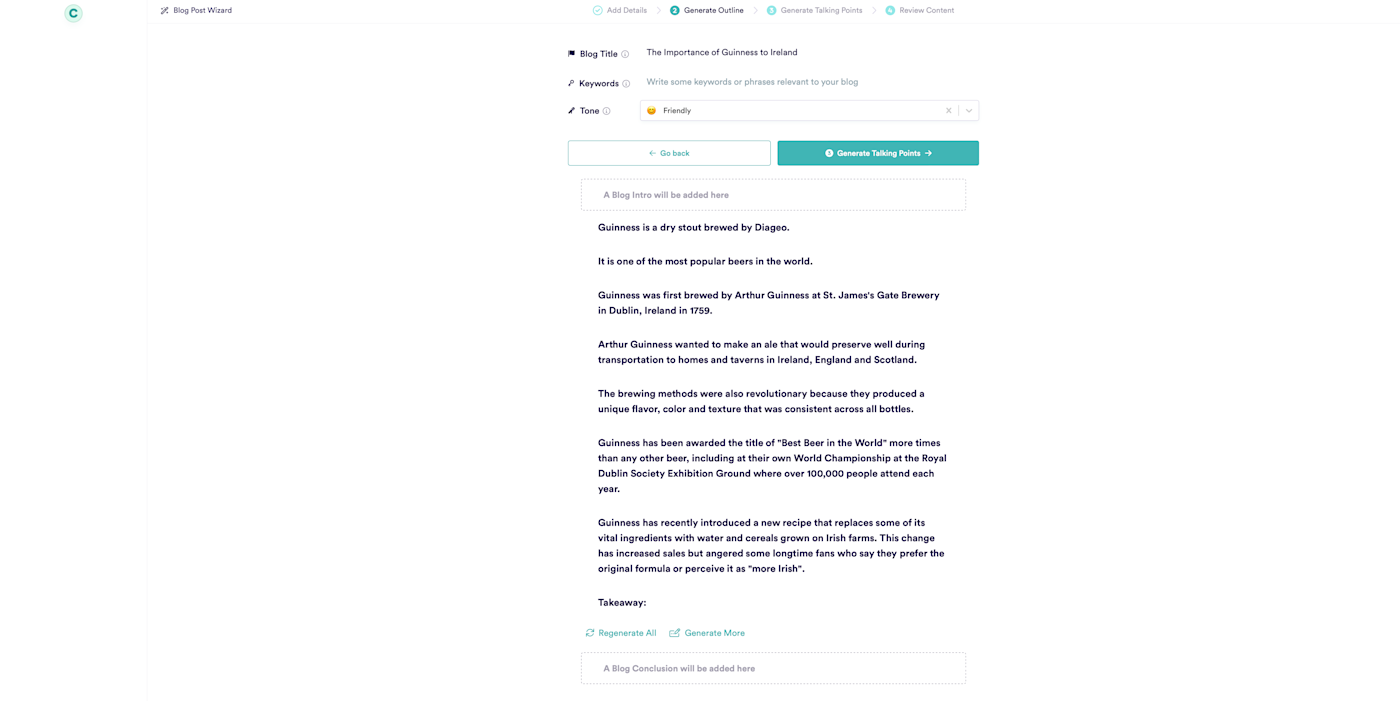

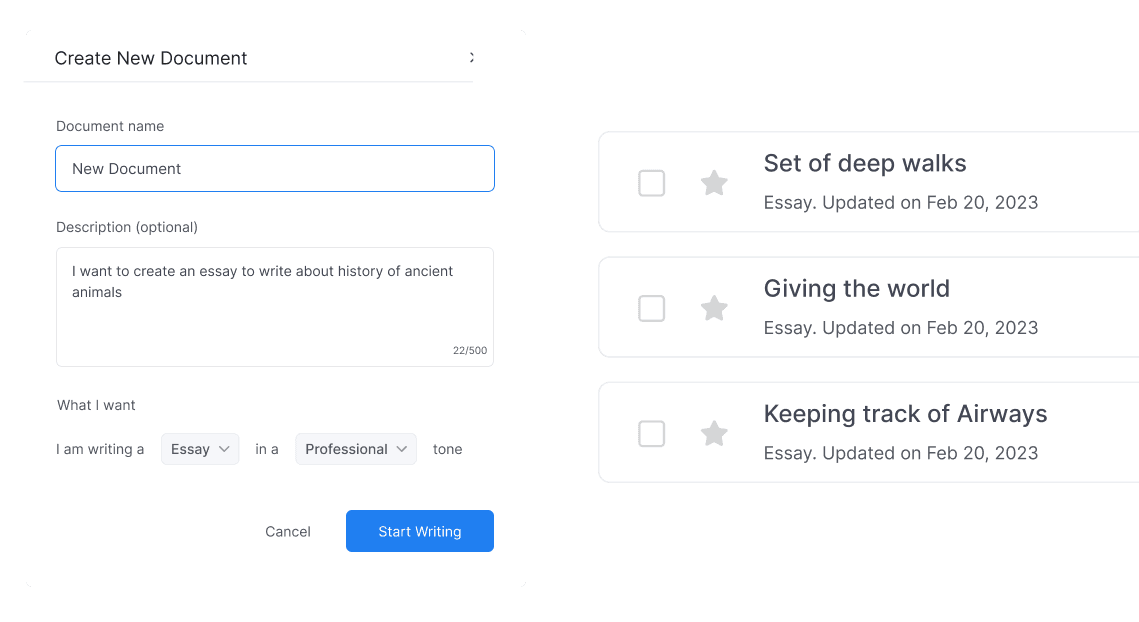

How does PerfectEssayWriter work?

- Pick the right tool for your purpose — Go with an essay writer if you want to generate a full essay or choose the essay outliner if you want to create just the outline of the essay.

- Enter your specific conditions and preferences. Add essay topic, academic level, essay type, number of pages, and special instructions, if any.

- Click on “generate” and wait for the result

- Once you have the essay generated, you can review, edit, or refine it and then download it.

- Generates a large chunk of data up to 2000 words

- Output is provided within 90 seconds

- Provides a plethora of other tools like Citation generator, grammar checker, thesis statement generator, and more

- Comes with 10+ essay writing templates

- Subscription-based and not a free tool

- Human review is a mandate

2. Essaybot - Personalized AI writing

Essaybot is the product of a reputed online essay-writing service, MyPerfectWords. It is meant to enhance academic essay writing and streamline the tasks of students. Its user friendly website makes it an instant and hassle-free essay generation saving a lot of time and effort for students.

How does Essaybot work?

- Enter the essay title or topic

- Click on “start writing” and wait for it to generate a well-reasoned essay.

- The tools come for free

- No sign-up is required

- 100% unique and High-quality output

- Very limited features that lack advanced functionalities

3. FreeEssayWriter.net

FreeEssayWriter is an organization that provides essay-writing services to students worldwide. It has an AI essay typer tool — that helps you generate essays instantly. What sets this essay typer apart is its initiative to help students with their free essay writer providing the students with a 2-page free essay.

How does FreeEssayWriter.net work?

It works similarly to Essaybot, input the title or the topic of your essay and wait for it to generate the essay. They also have an option to edit and download a free version of the generated essay instantly.

- Provides high-quality essays and is considered to be one of the reliable and trusted sources of information

- Students can improve their writing skills and learn more about essays by referring to their free essay database or sources

- Priority customer support is available 24*7

- The site is not optimized for mobile devices

- The quality of the essay output could still be improved

4. MyEssayWriter

This AI essay writing tool is no exception in terms of generating a high-quality essay. You can generate essays for various topics depending on the background of your research study. Be it academic or non-academic essay writing, this tool comes in handy.

How does MyEssay Writer work?

Add your preferences and then click on generate. It will give you a high-quality and 100% unique essay crafted based on your requirements.

- The tool comes for free — no subscription is required

- Knows for its consistency in the quality and the tone of the essay output

- Also has a paid custom writing service that provides human-written essays

- Might not provide quality output for complex and technical-based keywords or topic

5. College Essay AI

College essay AI stands unique as an ai writing tool as it not only uses an AI-based algorithm to generate essays but it also backs up the output as it is reviewed and approved by a team of professional experts. It is the best AI essay writing tool for college and graduate students where the output adheres to the graduate students' essay writing guidelines.

How does the College Essay AI generator work?

- Input the required information — essay topic, academic level, number of pages, sources, and specific instructions, if any.

- Click on “generate essay” and wait for the output

- Conduct plagiarism and grammar check

- Download the essay

- High-level output for academic essay writing

- Pocket-friendly premium plans

- Doesn’t provide multiple sets of templates

- Not quite suitable for non-academic essay writing

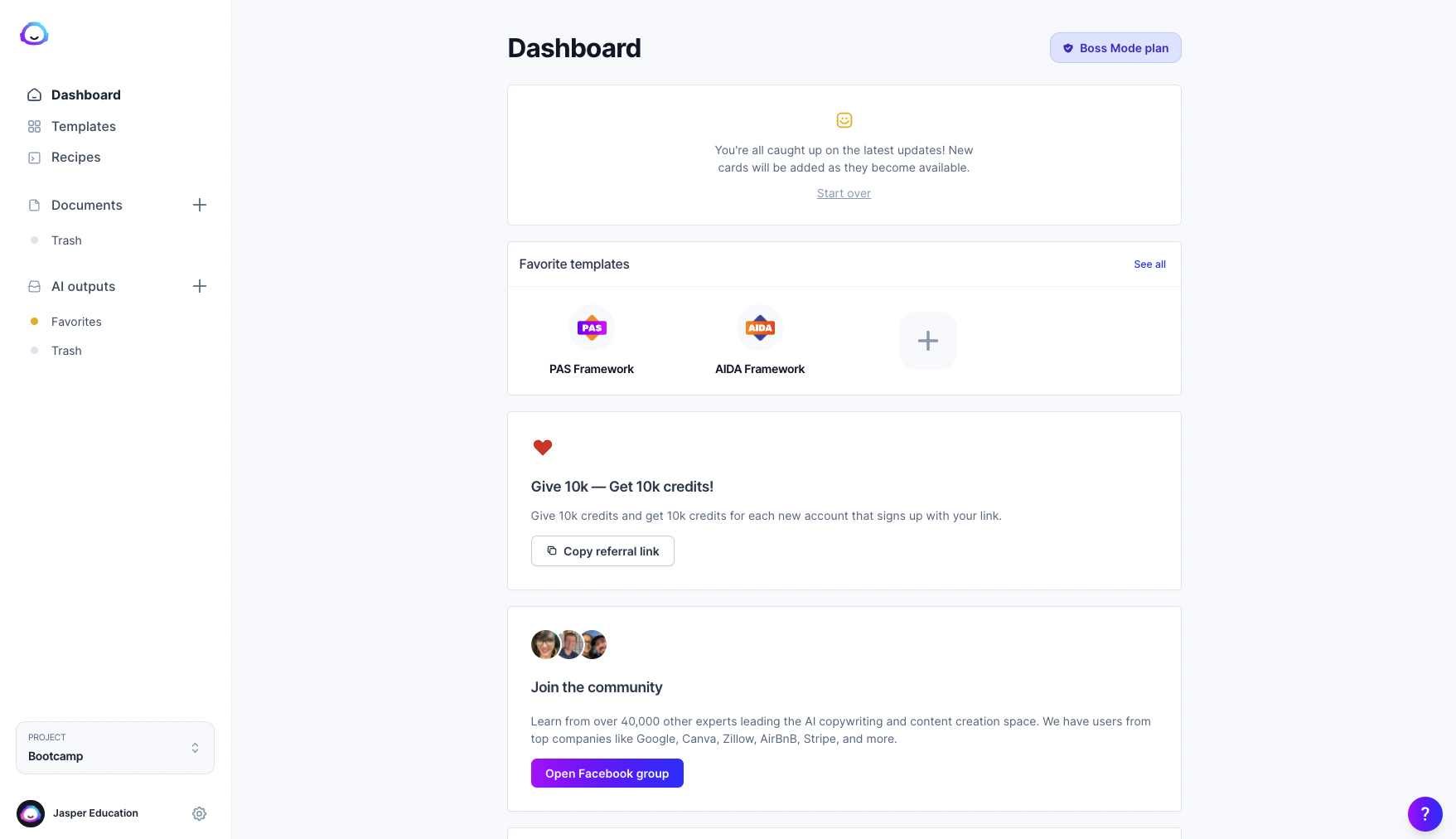

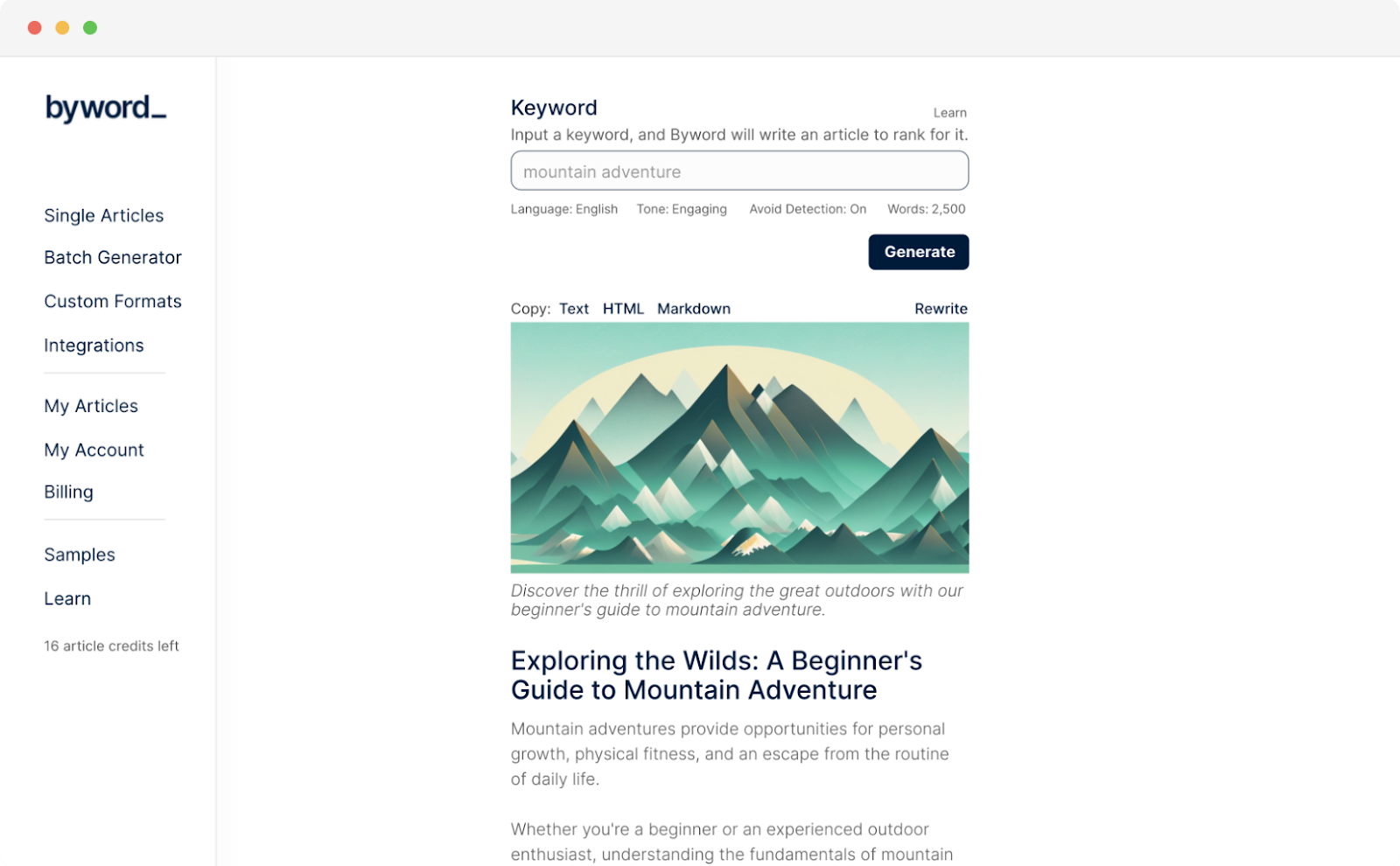

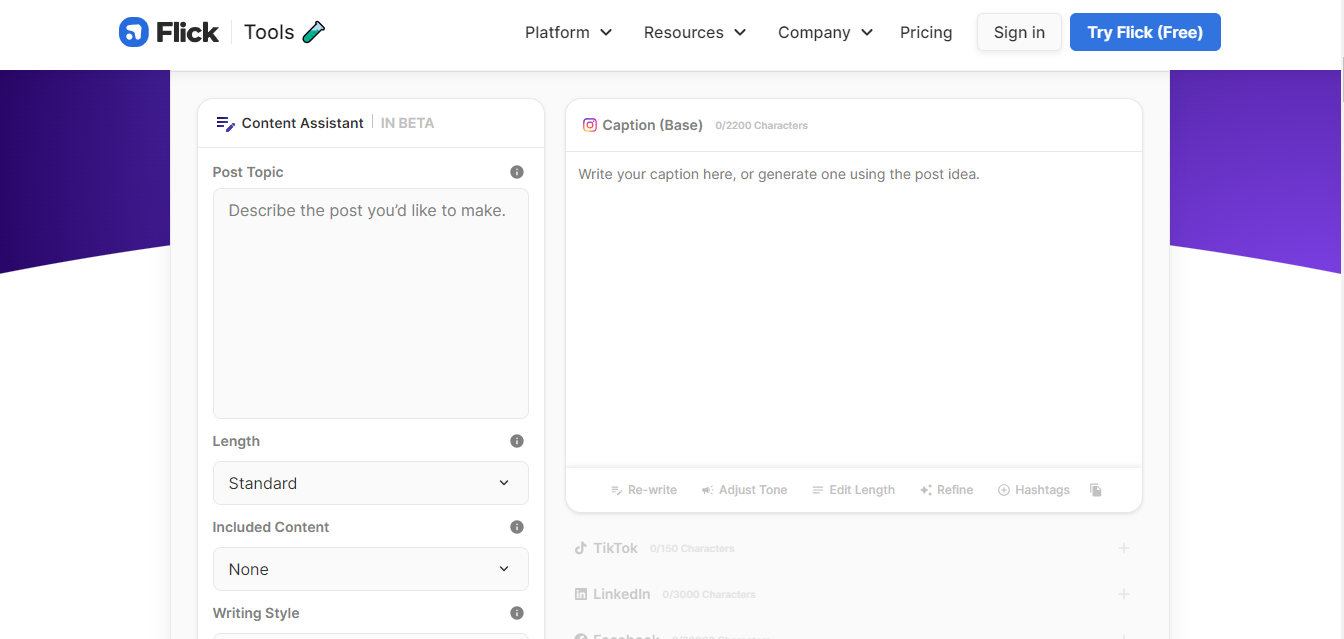

6. Jasper AI

Jasper AI has been the oldest player in the game of AI content writing. Fast forward to now, its features have been magnified with the inception of natural language processing algorithms and that’s how they are helping students write their essays as well. However, Jasper is the best AI tool for non-academic writing projects like content writing or creative writing.

How does Jasper AI work?

- Choose a template — if you are about to write an essay, go with the “document”

- Add your preferences

- Click “compose” and get the output

- Generates the essays instantly

- Provides well-structured output according to the tone and style of your preferences

- Not quite suitable for academic writing essays

7. Textero AI

Textero AI provides a few writing tools for students that facilitate their various academic papers and writing projects. Its essay generator helps you generate ideas for a full-length essay based on the topic and also suggests new topic ideas or thesis statement ideas for your academic assignments.

How does Textero AI work?

- Click on “Essay Generator” located on the LHS (Left-hand Side)

- Input the title and description based on which you want to generate the essay

- Pick the right citation style

- Click “generate” and wait for the output

- It also provides other tools like an outline generator, and summary generator and has an AI research assistant that answers all your questions relevant to the research

- The output is 100% unique and plagiarism and error-free

- Might fail to provide an essay focussed on complex or technical topics

8. Quillbot

Though Quillbot is essentially built for paraphrasing and summarizing tasks. It comes as a rescue when you have to revamp, improvise, or refine your already-composed essay. Its co-writer helps you transform your thoughts and ideas and make them more coherent by rephrasing them. You can easily customize your text based on the customization options available.

How does Quillbot Paraphraser work?

- Import or copy the content

- Click on “Paraphrase” “Summarize” or “Suggest text” based on your requirement

- Make the required customizations and save the document.

- Offers a plethora of tools required for students

- Both free and premium plans are available

- Enhances vocabulary and language skills

- Limited customization options with the free plan

- Only supports the English language

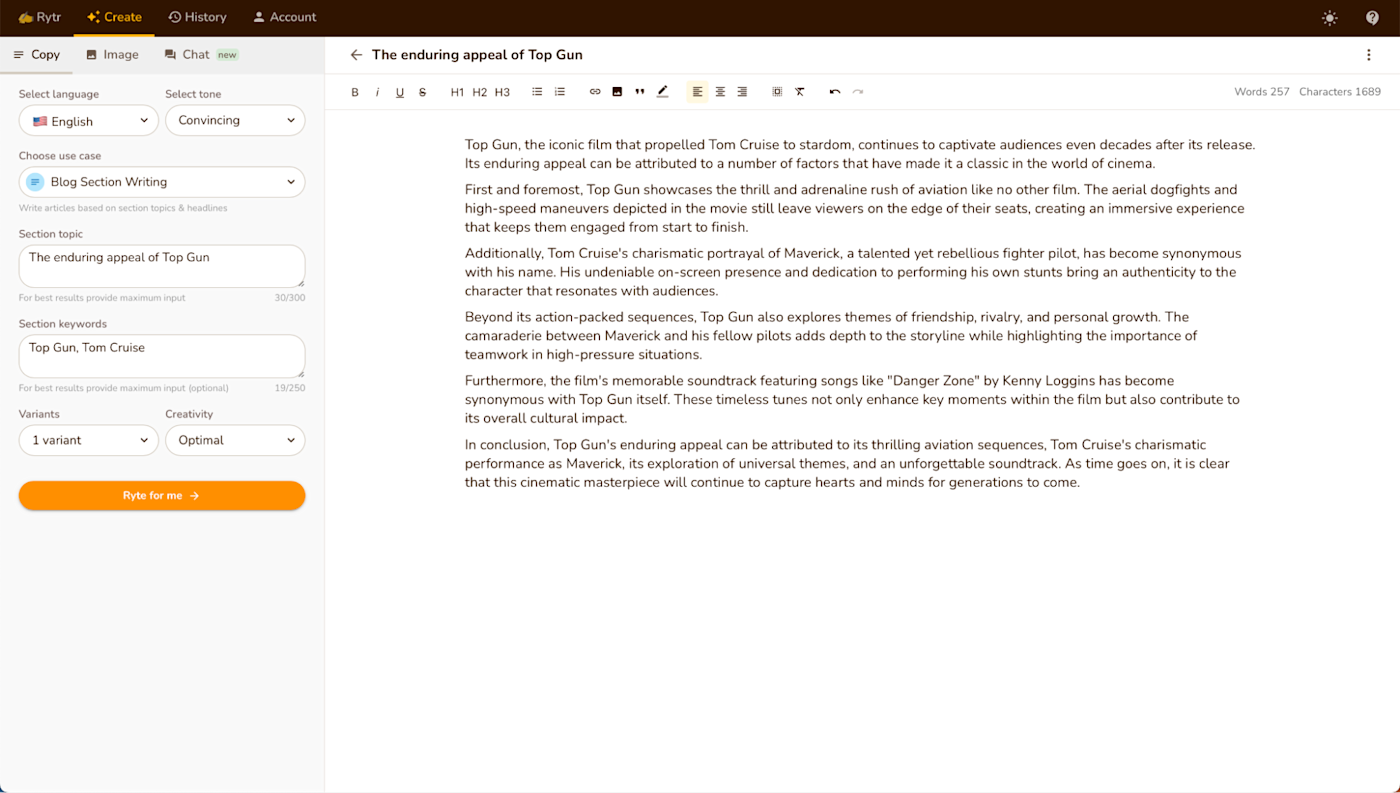

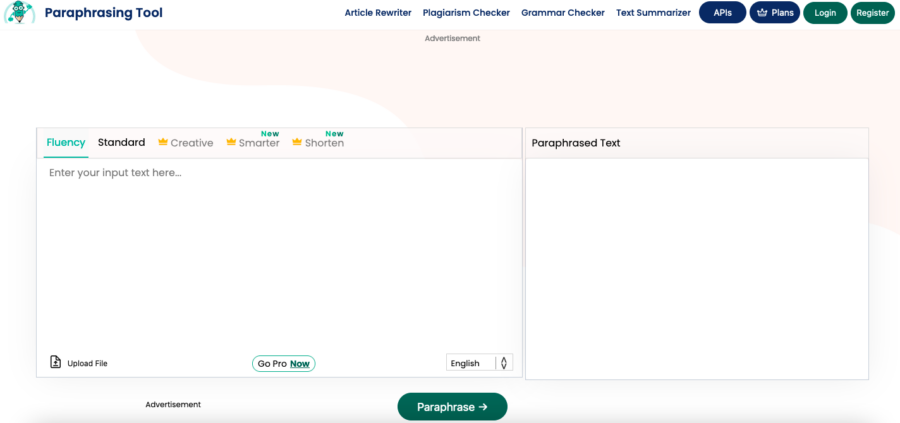

9. SciSpace Paraphraser

SciSpace is the best AI tool that helps you fine-tune your essay. If you feel your essay writing needs AI suggestions to improve the language, vocabulary, writing styles, and tone of your essay, SciSpace is at your rescue. It has more customized options than Quillbot and improves your essay by rephrasing it according to the required or preferred writing style, and tone. This is a very good alternative to Quillbot.

How does SciSpace Paraphrasing work?

- Simply paste the content to the screen

- Choose the length and variation properly

- Select the language

- Click “Paraphrase”

- Has 22 custom tones and all of them are available even on the free plan

- Supports 75+ languages

- Comes with an AI-detection report for English paraphrase output

- Delay in the output

10. ChatGPT

It would be unfair if we talk about AI tools and do not enlist ChatGPT. When it comes to automated essay writing tasks, ChatGPT is not trivial. With proper prompts, you can automate the essay writing process and generate a well-crafted and coherent essay. However, the quality and the accuracy cannot be trusted as the model hallucinates and doesn’t include sources.

How does ChatGPT work?

- Create a prompt based on your requirement

- Ask ChatGPT to write an essay about your topic, specify conditions and preferences

- Click enter and wait for the essay

- Comes for free

- Cannot rely on the output as the model hallucinates

- Lacks the upgraded features that other essay-writing tools have

Concluding!

Writing essays can be a real struggle. But, the inception of the best AI essay-generation tools makes the entire writing process a lot easier and smoother. However, you should be extra vigilant while relying on these tools and consciously use them only as a technological aid. Because over-reliance on these AI tools could diminish student's writing skills and the user can become more gripped by the tools. So, use it wisely without affecting your knowledge and skills.

You can explore the above tools whenever you need any help with essay writing, and reap the benefits of them without compromising on the quality of your writing.

And! If you're stuck exploring multiple research papers or want to conduct a comprehensive literature review , you know which tool to use? Yes, it's SciSpace Literature Review, our AI-powered workspace, which is meant to make your research workflow easier. Plus, it also comes with SciSpace Copilot , our AI research assistant that answers any question that you may have about the research paper.

If you haven't used it yet, you can use it here !

Choosing the best AI for writing long-form essays depends on your requirements. Here are the top 5 tools that help you create long-form and college essays —

1. Free Essay Writer AI

2. College Essay AI

3. My Essay Writer

4. Textero AI

5. Perfect Essay Writer

The Perfect Essay Writer AI and Textero AI are the two best AI essay generators that help you write the best essays.

ChatGPT is not specifically built to assist you with essay writing, however, you can use the tool to create college essays and long-form essays. It’s important to review, fact-check the essay, and refer to the sources properly.

Essaybot is a free AI essay generator tool that helps you create a well-reasoned essay with just a click.

Unless your university permits it, using AI essay generators or writing tools to write your essay can be considered as plagiarism.

You might also like

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

AI for Meta-Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Best AI writer of 2024

Use the best AI writers to create written content quickly

- Best AI writer overall

Best choice for marketers

Best for wordpress users, best for long-form writing.

- Best free version

- Best for short-form

Best for sourcing

- Industry rankings

How we test

1. Best AI writer overall 2. Best for marketers 3. Best for WordPress users 4. Best for long-form writing 5. Best free option 6. Best for short-form writing 7. Best for sourcing 8. TechRadar's AI writer rankings 9. FAQs 10. How we test

The word "AI" has been named the word of the year. ChatGPT has made waves since its introduction in late 2022. With every new iteration of this powerful tool, users have found innovative ways to use it to simplify and speed up their work.

Now, there are many AI writing assistants on the market, competing with ChatGPT to become the king of AI-powered writing tools. These new tools aim to simplify the writing process by generating long-form content, researching keywords, creating images from text, and more. Many bloggers are using these tools to improve their content and save time.

However, there are some drawbacks to using AI writers. The content generated may require additional editing to ensure it's polished and accurate. AI-generated content may also lack the unique voice and style a human writer can provide. Despite this, the benefits of using AI writers, such as cost and time savings, often outweigh these minor drawbacks.

In conclusion, AI writers are an excellent solution for creating high-quality content without spending countless hours or breaking the bank. With numerous writing tools available today, content creation can be easily sped up and simplified. If you're interested in trying one of these tools, we've got you covered with our list of the best AI writers of the year. Check it out!

The best AI writers of 2024 in full:

Why you can trust TechRadar We spend hours testing every product or service we review, so you can be sure you’re buying the best. Find out more about how we test.

See how our top picks compare in the following analysis and reviews as we discuss reasons to subscribe, reasons to avoid, our test results, and what we liked most about each cloud storage platform.

The best AI writer overall

1. GrammarlyGO

Our expert review:

Specifications

Reasons to buy, reasons to avoid.

✔️ You also need a grammar editor: Getting help from an AI writer is even better with one that also helps you with grammar, like Grammarly.

✔️ Need to use it across multiple apps: With Grammarly installed on your computer, you instantly gain access to it across your favorite apps like Microsoft Word and other word processing packages.

✔️ Want something that's easy to use — once you learn how to do it: Once you understand how GrammarlyGO works, it's going to make your life easier and assist you in making your text better.

❌ You're on a strict budget: No doubt, Grammarly itself is expensive, especially if you only want to pay for it on a month-to-month basis.

❌ You don't need a grammar tool: Maybe this is overkill, depending on your situation.

❌ You need social networking-specific tools: GrammarlyGO doesn't offer these types of tools, at least for now.

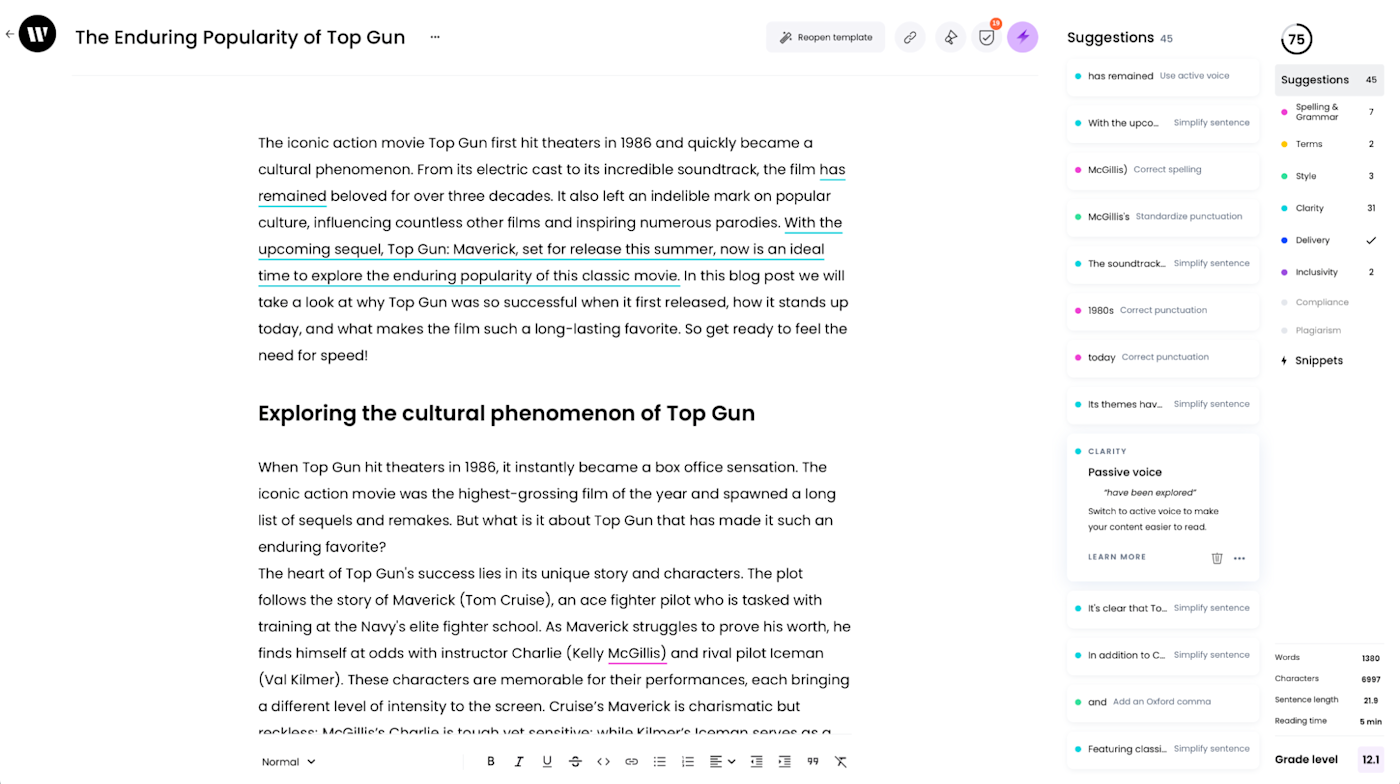

Even in beta, GrammarlyGO is an excellent addition to an already powerful Al-based writing tool. You can use it to become a much better writer in just a few steps.

Check out our in-depth GrammarlyGo review for a closer look at the service, and see why it's our top AI writer pick for 2024.

Grammarly has been a reliable companion for writers, helping them polish their craft by providing suggestions that make their writing clearer, more engaging, or more effective. And now, they've taken it up a notch by introducing GrammarlyGO, a feature-packed add-on that comes bundled with the rest of the software.

To get the most out of GrammarlyGO, you must understand how Grammarly works, as the two are closely intertwined. When using GrammarlyGO, it's essential to remember the number of prompts available to you, which varies depending on the plan you choose. Whenever you ask Grammarly to improve your text, one prompt is used, regardless of whether you use the suggestion. Grammarly Free users get access to 100 prompts per month, while Grammarly Premium subscribers receive 1,000 prompts per month. For Grammarly Business users, the number goes up to 1,000 prompts per user every month.

GoogleGO AI features are classified into five categories: ideate, compose, reply, rewrite, and personalize. The ideate feature helps you generate article ideas that are exciting and thought-provoking. With Grammarly's assistance, you can develop topics like "Five ways to motivate employees" or "Name five great topics about fall" that can capture the reader's attention and spark their interest.

The compose feature is perfect when you want Grammarly to help you write something from scratch. For instance, you could ask Grammarly to help you write an announcement about your engagement or a cover letter for a new job. The more information you provide, the better the results, and GrammarlyGO can help you create a masterpiece with its advanced suggestions and insights. Adding details like the name of your fiancé and the engagement date can make your announcement even more unique. In contrast, information about the job you're applying for can make your cover letter more effective.

If you're unsure how to respond to a message, Grammarly's reply feature can save the day. You can ask Grammarly to answer questions like "What should I say to Brent about the new job?" or "How can I congratulate Tom and Becky on their upcoming nuptials?" With Grammarly's superior writing skills, you can craft an engaging, effective, and impressive response.

With these incredible features, GrammarlyGO can help you take your writing to new heights and unleash your creativity.

Please read our full GrammarlyGo review .

- ^ Back to the top

✔️ You are a marketer: Anyword is the best AI writer for marketers on the planet. It helps you create content based on your company's "voice," and learns as it goes.

✔️ You enjoy trial and error: There's no "right" answer when it comes to AI text generation. Anyword makes it easier to tweak text once or unlimited times to help you get the text perfect for your needs.

✔️ You need to generate unlimited words: There are limits elsewhere, but Anyword doesn't limit how many words it will generate on a monthly basis.

❌ You want app integration: You'll need to copy and paste text from your favorite word processor to Anyword, which can get annoying for some.

❌ You want a free plan: Once you exhaust your trial, you'll need to pick a free plan to continue.

❌ You aren't a marketer: The heavy marketing focus can't be avoided.

Anyword offers a slick and easy-to-use interface. In mere moments, you'll be able to create excellent content that caters to your intended audience

Check out our in-depth Anyword review for a closer look .

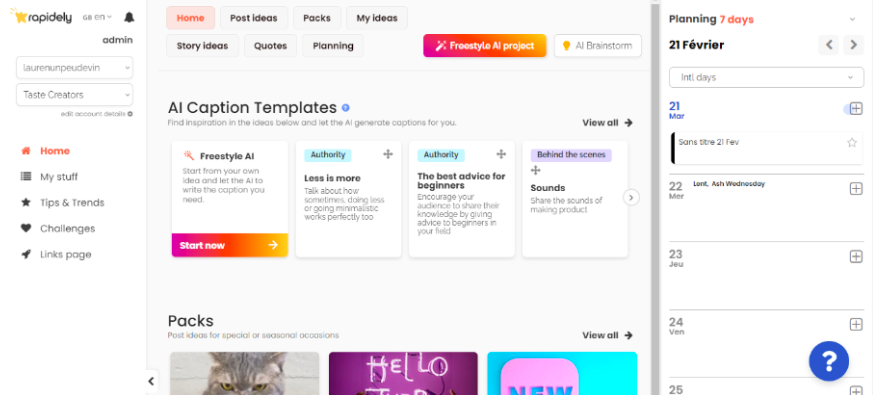

Are you tired of struggling to generate creative marketing copy or unsure how to optimize your existing content? Anyword is an innovative cloud-based writing tool that can help you overcome these challenges and achieve exceptional results. With Anyword's intuitive interface and user-friendly tools, you can generate, test, and optimize your copy in ways you never thought possible.

With unlimited words in each plan, Anyword gives you plenty of space to craft compelling content that truly resonates with your audience. Its advanced AI-powered algorithms can analyze your existing marketing materials and produce multiple variations of your copy, enabling you to compare and contrast different solutions and select the best option for your brand.

One of the key features of Anyword is its Brand Voice function, which enables businesses to establish a consistent identity across all their marketing materials. Whether you're refining your tone of voice, targeting your audience, or building out your messaging bank, Anyword can help you create copy that accurately reflects your brand's personality, tone, and style.

Additionally, Anyword seamlessly integrates with various platforms, from Hubspot to LinkedIn Ads, enabling you to use copy intelligence to enhance the quality of your future content. By analyzing the performance of your existing materials, Anyword empowers you to make informed decisions about optimizing your messaging for even better results.

But that's not all - Anyword's advanced algorithms can also analyze the performance of your competitors' marketing materials, giving you insights into their copy and enabling you to create content that sets you apart from the competition.

In summary, Anyword can help you unlock your creativity and produce exceptional marketing copy that resonates with your audience. With its range of user-friendly tools, advanced AI-powered algorithms, and seamless integration with various platforms, Anyword is the perfect writing tool for businesses looking to enhance their marketing efforts.

Please read our full Anyword review .

3. Articleforge

✔️ You use WordPress heavily: Articleforge works great with WordPress; get started in just a few steps.

✔️ You want package customization: The more you're willing to pay, the more words you can generate each month. It's flexible.

✔️ You need marketing-based tools: Offers SEO optimization, content in bulk, and more.

❌ You don't want to self-edit : Articleforge may require more post-generation editing than other options, which could slow you down.

❌ You don't want to deal with duplicates: Yes, sometimes Articleforge repeats suggestions.

❌ If you don't want to spend more for a monthly subscription: It's cheaper to buy this on a yearly basis, and that might not be a commitment you're willing to make.

Articleforge utilizes deep learning and AI to improve content over time, though heavy editing and fact-checking are often necessary.

Check out our in-depth Articleforge review for more information.

Articleforge is a tool that can greatly help speed up the writing process for users. It is a valuable resource for those who need to generate content quickly but do not have the time or resources to do so themselves. However, it is important to note that it is not a replacement for an experienced writer or editor. While it can provide recommendations for titles and automate SEO and WordPress publishing, it is not designed to produce ready-to-publish content.

One of the benefits of Articleforge is that it is available in seven languages, making it ideal for international blogs or multi-language sites. Users simply need to enter a few keywords and the topic they want to cover, and the platform will generate content in under 60 seconds. This generated content will use the provided keywords and cover the desired topic.

In addition to its quick and easy content generation, Articleforge also offers various integrations, including MS Word and WordPress integrations. The platform also provides integrations with other software systems like SEO AutoPilot, CyberSEO, RankerX, SEnuke TNG, and more. These integrations are easy to use, thanks to the API key offered by the platform.

While the platform is a convenient tool for creating content, its output quality falls short of expectations. As with any automated system, fact-checking is necessary for the majority of the content offered by the platform. The platform does offer better output quality with customized input. However, extensive testing is required, which can quickly exhaust the "word meter."

Overall, Articleforge can significantly expedite the writing process and help overcome writer's block. It is advisable to test it out and find a balance between the platform and tailored input to yield superior results. While it should not be relied upon as a sole source of content, using it in conjunction with other resources can help users quickly generate high-quality content.

Read our full Articleforge AI writer review .

✔️ You want a great plagiarism checker: You want to create original content, right? This checker makes sure that's true.

✔️ You need to create content in multiple languages: Some folks are writing content in multiple languages and Jasper lets you do this.

✔️ You want access to a lot of features: The team behind this solution tends to add new features on a regular basis without raising the price. That's sweet.

❌ You don't have time to learn: Any AI writer takes time to learn. Jasper takes a little bit more time.

❌ If you don't want to spend a lot: Some folks might not feel the Creator package is enough and the next one is expensive.

❌ If you aren't willing to edit a lot: Some of the content Jasper creates is better than others. Some extra editing is key.

Jasper is a platform that is highly customizable and comes with a user-friendly interface. All the necessary tools that you need are just a click away. The platform’s content generation capabilities are hidden behind easy-to-reach templates, making it an easy-to-use tool.

Check out our review of Jasper to learn more about the AI writer.

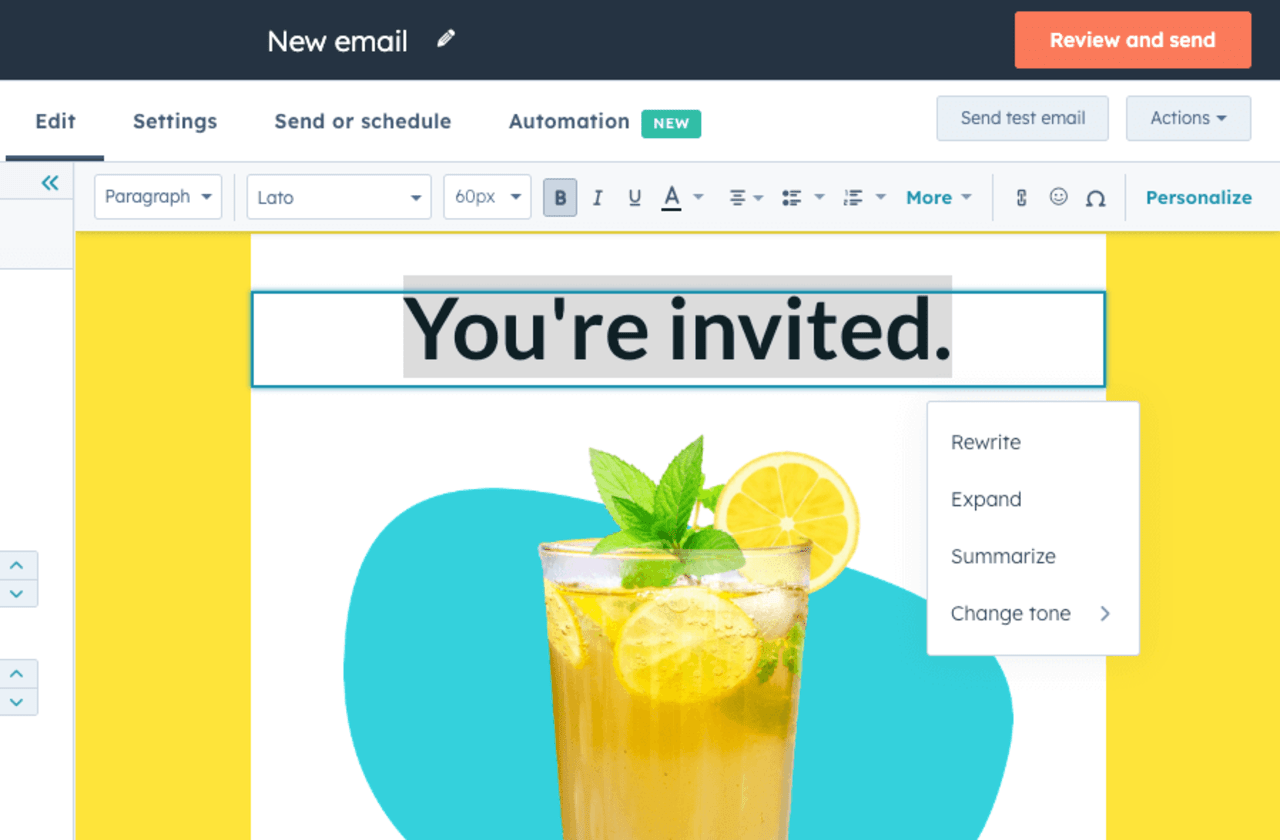

Jasper is a powerful platform that leverages natural language processing (NLP) algorithms to analyze data from various sources across the web. With this ability, it can generate content ideas based on the relevant data you input, such as keywords, topics, and more. Jasper can help create a wide range of content formats, including blog posts, social media content, emails, and much more.

One of the most significant advantages of Jasper is that it has a tone feature that allows you to assign a corresponding tone to the copy you create if you’re targeting a specific persona. This feature is incredibly useful because it helps ensure that the content you create resonates with your target audience. Additionally, Jasper can help you improve your content through optimization recommendations, which can be accessed through numerous templates available on the platform.

If you’re short on time and need to create content quickly, Jasper is the perfect solution. It can offer content in mere seconds with just a few clicks and some input. With Jasper, you can save time and increase productivity, allowing you to focus on other essential tasks.

Another unique feature that Jasper offers is the “Boss Mode” feature, which allows you to write 5x faster. With this mode, you can give commands to Jasper, and it will do all the work for you. You can even write a complete book using this mode in just minutes. This feature is incredibly useful for writers who need to create a large volume of content in a short amount of time.

In the Boss Mode, you can also use pre-built recipes offered by the Jasper team such as “Write about (keyword),” but you also have the option of creating your own, which can be incredibly helpful if you have specific requirements for your content. By automating your writing process, you can save time and focus on other critical tasks.

Read our full Jasper review .

The best free version

✔️ You want a free plan for minor work: If you're okay with only generating 2,000 words per month, there's a free plan for that.

✔️ You need unlimited word generation: You can create unlimited words each month with all the paid plans.

✔️ You want multiple tools: New features are added often, making the product even better.

❌ You are a marketer: There are better options if you primarily need to write marketing copy.

❌ You aren't willing to learn: Here's another option that is a little bit harder to learn, at least initially.

❌ You need app integration: Expect to stay on the CopyAI website to get your work done, which requires copy and paste.

CopyAI helps writers create high-quality copy with the power of AI, saving time and producing better content that resonates with your audience.

Check out our in-depth CopyAI review to see whether it's the tool for you.

CopyAI has been making waves in the world of AI writing tools, becoming a favorite among users who want to create high-quality content that can help them stand out in today's crowded digital space. The tool offers a wide range of options that allow users to get started and take their writing to the next level, from exploring various writing templates, settings, and features on the user dashboard to creating a compelling copy in minutes.

The user dashboard serves as the creative command center for CopyAI users, providing a user-friendly and intuitive interface that makes it easy to navigate through different features. From here, you can quickly access various options that can help you create content that resonates with your audience, whether you need to write a blog post about travel or an email to a potential client.

The chat feature is the default option that acts as a blank canvas to help generate inspiration. The brainstorm feature allows you to create copy such as "ten catchy Twitter headlines on holiday shopping," "the best Facebook headlines for marketing professionals," and more. If you're struggling to come up with a topic, don’t worry. CopyAI’s chat function provides prompt templates to give you a head start. These templates cover various topics, including content creation, SEO, email marketing, social media, PR and communication, sales, and strategy.

Moreover, you can create custom templates that cater to your specific needs. Each template in the collection provides various options, so whether you need a headline generator, a step-by-step guide, or a product description, CopyAI has you covered. You can even use the "rewrite content" option to enhance your written content, making it more engaging and effective.

To fully personalize your experience with CopyAI, you should create one or more brand voices. This process involves providing text that accurately describes you or your company's unique voice. This text should be between 50 and 500 words and can come from various sources such as blog articles, social media posts, website copy, marketing emails, and more. This allows CopyAI to tailor its AI-powered tools to better suit your brand's needs, making it easier for you to create content that resonates with your target audience and helps you achieve your goals.

In summary, CopyAI is a powerful AI writing tool that offers a wide range of features and options to help you create high-quality content. From the user dashboard to the chat and brainstorming features, CopyAI provides a user-friendly and intuitive interface that makes it easy to create compelling and engaging content. With custom templates and brand voices, you can personalize your experience with CopyAI and create content that resonates with your target audience, helping you stand out in today's crowded digital space.

Read our full CopyAI review .

The best for short-form

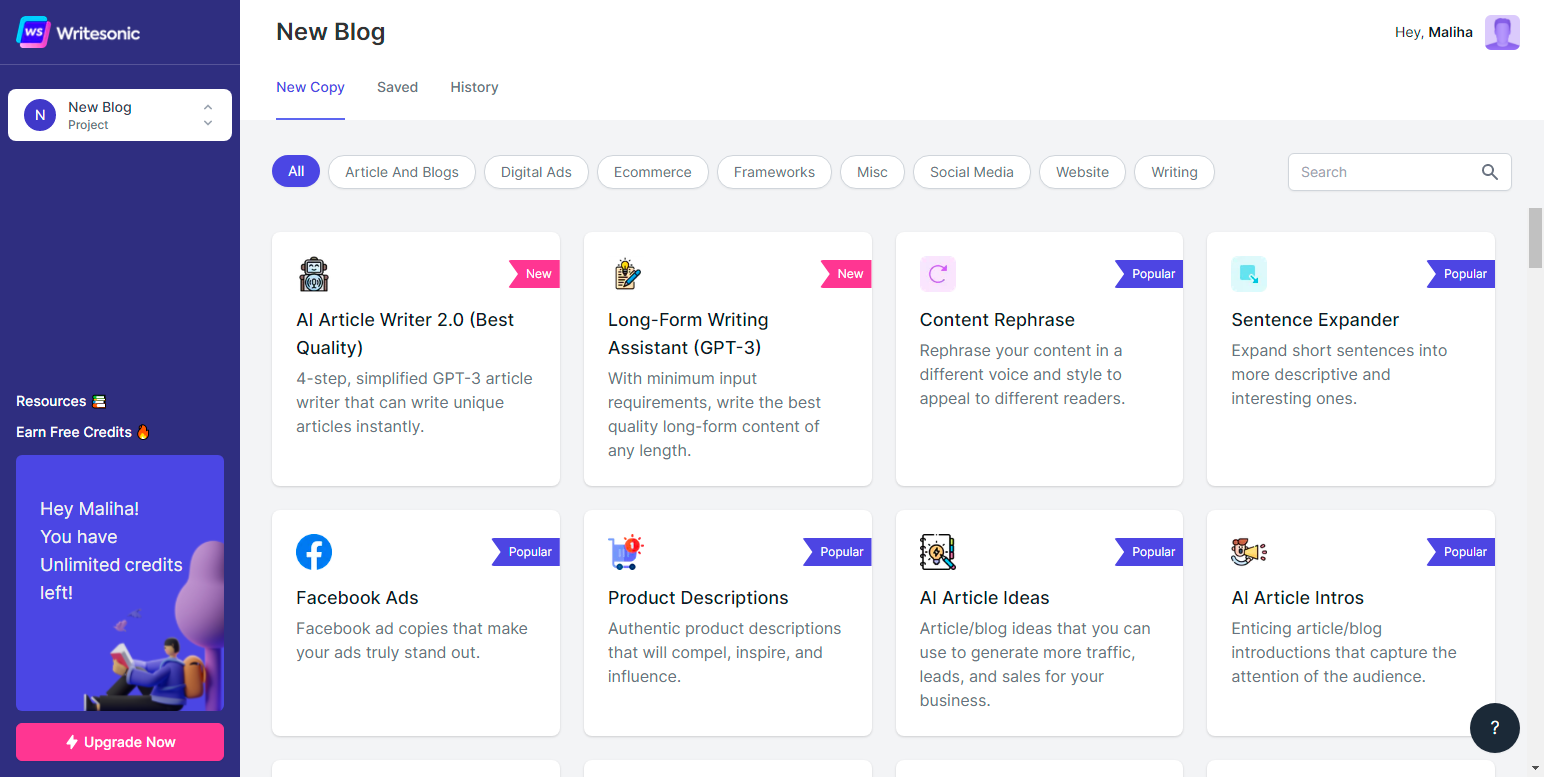

6. Writesonic

✔️ You aren't tech savvy: It's one of the easiest-to-use solutions on the market.

✔️ You need lots of languages: Writesonic supports 25 languages and counting.

✔️ You're a freelancer: There's a package just for you.

❌ You want to pay a lower price: Some have criticized Writesonic for being too expensive. That's true with the Smart Team options

❌ You need more third-party integrations: It doesn't really place nice with other software tools, which could add some time to your work.

❌ You don't like tackling a learning curve : Like others on this list, there's a slighter higher learning curve with this one

Writesonic is an expansive AI writing platform with an intuitive interface and versatile templates for all content creation scenarios.

Check out our in-depth Writesonic review to see if this is the AI writing tool for you.

Writesonic is an innovative content creation platform that provides users with various features and tools to generate high-quality, engaging content. One of the most impressive features of Writesonic is its versatility - it supports over 25 languages, including English, French, Italian, German, Japanese, Chinese, and more. This is a significant advantage for businesses that operate in multiple regions and need to produce content in different languages.

Another notable feature of Writesonic is its tone of voice customization tool. Users can choose from various tones, including "Excited," "Creative," and more. This feature adds a unique twist to the content, tailoring it to the user's needs. However, it's essential to note that the tone of voice feature may require additional editing to ensure the content is clear and coherent.

Regarding website copywriting, Writesonic provides users with an impressive range of tools. It can create landing pages, SEO meta descriptions, and feature-rich headers and subheaders. Additionally, it allows users to create social media ads on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Google . Content creators can also benefit from Writesonic's blog writing, point expansion, and text analysis tools, which can rephrase the content and improve its readability.

The platform also offers e-commerce copy creation and popular copywriting formulas, such as the "AIDA" and "Pain-Agitate-Solution" formulas. These formulas are tried and tested approaches to writing compelling, persuasive content that resonates with readers.

However, it's essential to note that the content generated by Writesonic may require significant editing from the user. While the platform does an excellent job of generating content, it's essential to ensure it's clear, coherent, and tailored to the user's needs. If you're looking for a completely hands-off approach to content creation, Writesonic may not be the best option. However, for businesses that need to generate high-quality, engaging content quickly, Writesonic is an excellent choice.

Please read our full Writesonic review .

7. Al-Writer

✔️ You want a cheap package: You can get an AI writer for as little as $19/month.

✔️ You need clear sourcing: No better solution is available for providing sources for all text provided.

✔️ You want an easy solution: A very low learning curve exists.

❌ You want app integration: There's seamless integration with WordPress, but that's about it.

❌ You need marketing-specific tools: Sorry, this one doesn't have it.

❌ You want unlimited word generation: If you need to generate more than 120 articles per month, this is a very expensive solution.

AI-Writer is a unique word-generating tool that simplifies text creation and editing through an intuitive user interface. However, it may not be suitable for everyone.

Check out our in-depth AI-Writer review to see if it's the solution for you.

AI-Writer is a word generator that is easily accessible and is popular among freelancers and bloggers. It may not be as extensive as Anyword or CopyAI, which are primarily aimed at marketing and sales, but it serves its intended audience well.

One of the most significant advantages of AI-Writer is its unparalleled sourcing capabilities. It is the only AI content generator that cites sources for "everything it writes." Additionally, it updates its sources frequently, ensuring that any article generated by it sources the latest information on the subject. This is a significant advantage, particularly for those who are writing about current events or trending topics. With AI-Writer, writers can create content that is well-researched and accurate, without having to spend hours scouring the internet for sources.

Another significant advantage of AI-Writer is that it recognizes that not all types of content require sourcing. For instance, op-eds or personal essays don't usually require sources. AI-Writer recognizes this and hides sources and links from the main results page, making it easier for writers to focus on their content and not worry about sources.

One of the drawbacks of using AI-Writer is that its extensive sourcing process can cause a minor delay in generating results compared to other AI writing tools. Although this may not be a significant issue, the noticeable delay should be mentioned. For instance, alternative tools like GrammarlyGO offer results without hesitation. However, it is worth noting that the issue with AI-Writer is primarily due to its thorough sourcing process.

In conclusion, AI-Writer is an excellent tool for freelancers and bloggers who want to create high-quality content. It excels in sourcing capabilities, making it a go-to tool for writers who need well-researched and accurate content. Its ability to recognize when sourcing is not required is also an added advantage. While it may not be the fastest tool on the market, its thorough sourcing process is worth the wait.

Read our full AI-Writer review .

TechRadar's AI writer rankings

Numerous AI writing solutions are already available in the market, and we can expect more to arrive in the future. Have a look at our rankings of popular services below, and also check out the honorable mentions that currently can’t compete with the top services available.

What is an AI writer?

An AI writer is a revolutionary tool, capable of creating text and content without human help; it utilizes algorithms and machine learning to generate various AI content. From data-driven, high-value pieces to conversion-focused content perfect for marketing campaigns, AI writers can easily create just about any content.

As AI writing assistants gain exposure to various forms of real-world information, they gain proficiency in generating natural-sounding output. With their data coming from human sources, the output created also has a human-like quality. Much like how humans rely on existing content to craft something new, AI content tools scour the web for relevant data to fulfill the user's instructions, thus creating original content.

This, in a nutshell, explains what AI writing is and how it functions.

How to choose the best AI writer for you?

Let’s get this out of the way. Whichever platform you choose, you will have to do some editing, if you want to create useful texts.

Here are some of the factors you should consider when choosing the right tool for you:

1. Ease of use

Tools that don’t require technical knowledge or prior experience should be on the top of your list. Investment in good UI means that other aspects of the tool are also likely to be of a higher quality.

While this may not be popular with everyone, the price should play a major role in deciding which tool to go for. Some are simply overpriced while not offering much more than their lower-priced competition. Pay attention to the amount of content each price plan offers.

3. High-quality output

Despite the fact that, in the end, you will be editing the texts and images the tool creates, having a tool that creates high-quality content will mean less time spent on fixing mistakes and editing.

4. Integrations

If you’re running a blog or business and have been doing so for some time, you probably have your set of tools that you use for writing content. Making sure that the new AI platform syncs well with your existing toolbox can be essential for how long and how well you utilize the AI tool.

The list above is not exhaustive, but does offer a great starting point in your quest to find the best AI writing tool for your needs.

During our assessment, we’ve evaluated various aspects such as the number of writing templates, categories, recipes, number of languages supported, grammar checkers, etc. Our goal was to create an extensive list of AI writing assistants that offer much more than simple rewording features.

We tested the overall capabilities of the AI software, the tool's interface and ease of use, monthly article limits, SEO optimization features, and pricing, among other aspects.

In addition, we gave each platform a test article to write for us (a simple topic) and checked its sentence structure and content relevance.

Read more on how we test, rate, and review products on TechRadar .

Get in touch

- Want to find out about commercial or marketing opportunities? Click here

- Out of date info, errors, complaints or broken links? Give us a nudge

- Got a suggestion for a product or service provider? Message us directly

- You've reached the end of the page. Jump back up to the top ^

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Bryan M. Wolfe is a staff writer at TechRadar, iMore, and wherever Future can use him. Though his passion is Apple-based products, he doesn't have a problem using Windows and Android. Bryan's a single father of a 15-year-old daughter and a puppy, Isabelle. Thanks for reading!

- Mike Jennings

- Sead Fadilpašić

More than half of Americans have tried generative AI already

How to code your way to manageable cloud costs

Fortnite dev reveals reason why Metroid's Samus didn't join the game, says Nintendo was 'hung up' about its characters being on other platforms

Most Popular

- 2 Sony dropped OLED for its flagship 2024 TV – here's why

- 3 'The party is over for developers looking for AI freebies' — Google terminates Gemini API free access within months amidst rumors that it could charge for AI search queries

- 4 Looking for a cheap OLED display? LG's highly-rated C2 OLED TV is on sale for $839

- 5 Amazon Prime Video's disappearing act could point to a future without the service

- 2 You can already buy cases for the iPad Air 6, but the tablet might lack a rumored change

- 3 Sony dropped OLED for its flagship 2024 TV – here's why

- 4 Meta rolls out new Meta AI website, and it might just bury Microsoft and Google's AI dreams

- 5 This gadget promises to increase productivity inside your vehicle by converting ICE screens into displays — and even includes Samsung DeX compatibility for free

The best AI writing generators

These 7 ai writing tools will take your content to the next level..

Of course, all AI writing software needs human supervision to deliver the best results. Left to its own devices, it tends to produce fairly generic and frequently incorrect content, even if it can pass for something a human wrote. Now that AI tools are increasingly popular, people also seem more aware of what bland AI-produced content reads like and are likely to spot it—or at least be suspicious of content that feels like it lacks something.

I've been covering this kind of generative AI technology for almost a decade. Since AI is supposedly trying to take my job, I'm somewhat professionally interested in the whole situation. Still, I think I'm pretty safe for now. These AI writing tools are getting incredibly impressive, but you have to work with them, rather than just letting them spit out whatever they want.

So, if you're looking for an AI content generator that will help you write compelling copy, publish blog posts a lot quicker, and otherwise take some of the slow-paced typing out of writing, you've come to the right place. Let's dig in.

The best AI writing software

Jasper for businesses

Copy.ai for copywriting

Anyword for assisting you with writing

Sudowrite for fiction

Writer for a non-GPT option

Writesonic for GPT-4 content

Rytr for an affordable AI writer

How do AI writing tools work?

Search Google for AI writing software, and you'll find dozens of different options, all with suspiciously similar features. There's a big reason for this: 95% of these AI writing tools use the same large language models (LLMs) as the back end.

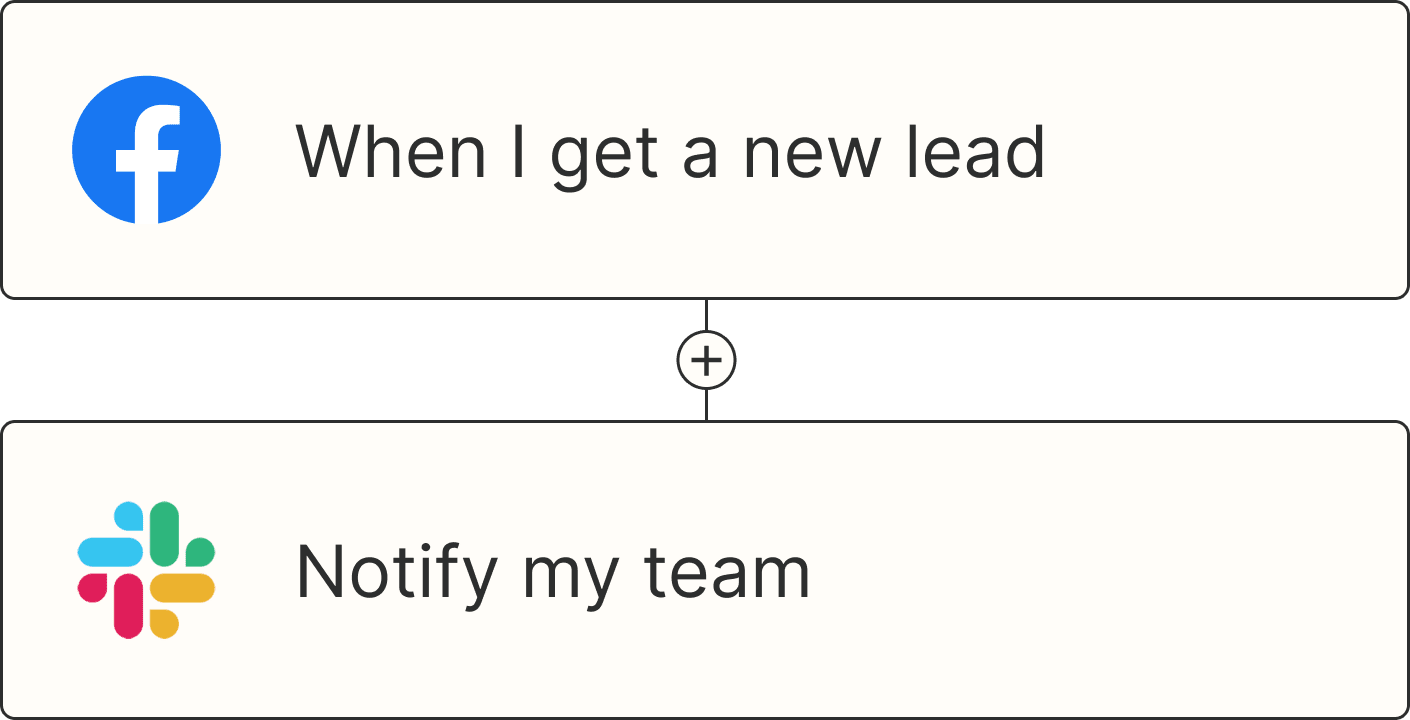

Some of the bigger apps are also integrating their own fine-tuning or using other LLMs like Claude . But most are really just wrappers connected to OpenAI's GPT-3 and GPT-4 APIs, with a few extra features built on top—even if they try to hide it in their own marketing materials. If you wanted to, you could even create your own version of an AI writing assistant without code using Zapier's OpenAI integrations —that's how much these apps rely on GPT.

See how one writer created an AI writing coach with GPT and other ways you can use OpenAI with Zapier .

Now this isn't to say that none of these AI-powered writing apps are worth using. They all offer a much nicer workflow than ChatGPT or OpenAI's playground , both of which allow you to generate text with GPT as well. And the better apps allow you to set a "voice" or guidelines that apply to all the text you generate. But the difference between these apps isn't really in the quality of their output. With a few exceptions, you'll get very similar results from the same prompt no matter which app you use—even if they use different LLMs. Where the apps on this list stand out is in how easy they make it to integrate AI text generation into an actual workflow.

As for the underlying LLM models themselves, they work by taking a prompt from you, and then predicting what words will best follow on from your request, based on the data they were trained on. That training data includes books, articles, and other documents across all different topics, styles, and genres—and an unbelievable amount of content scraped from the open internet . Basically, LLMs were allowed to crunch through the sum total of human knowledge to form a deep learning neural network—a complex, many-layered, weighted algorithm modeled after the human brain. Yes, that's the kind of thing you have to do to create a computer program that generates bad poems .

If you want to dive more into the specifics, check out the Zapier articles on natural language processing and how ChatGPT works . But suffice it to say: GPT and other large language models are incredibly powerful already—and because of that, these AI writing tools have a lot of potential.

What makes the best AI text generator?

How we evaluate and test apps.

Our best apps roundups are written by humans who've spent much of their careers using, testing, and writing about software. Unless explicitly stated, we spend dozens of hours researching and testing apps, using each app as it's intended to be used and evaluating it against the criteria we set for the category. We're never paid for placement in our articles from any app or for links to any site—we value the trust readers put in us to offer authentic evaluations of the categories and apps we review. For more details on our process, read the full rundown of how we select apps to feature on the Zapier blog .

We know that most AI text generators rely on the various versions of GPT, and even those that don't are using very similar models, so most apps aren't going to stand out because of some dramatic difference in the quality of their output. Creating effective, human-like text is now table stakes. It was required for inclusion on this list—but not sufficient on its own.

As I was testing these apps, here's what else I was looking for:

Tools powered by GPT or a similar large language model with well-documented efficacy. In practice, this means that most but not all of the AI writing tools on this list use GPT to a greater or lesser degree. Many apps are starting to hide what models they use and claim to have a lot of secret sauce built on top (because there's a marketing advantage in being different and more powerful), but the reality is that nine times out of ten, it's the GPT API that's doing the heavy lifting.

An interface that gives you a lot of control over the text output. The more options you have to influence the tone, style, language, content, and everything else, the better. I didn't want tools where you just entered a headline and let the AI do the rest; these are all tools that you collaborate with, so you can write great copy quickly. The best AI writing tools also let you set a default brand voice that's always on.

Ease of use. You shouldn't have to fight to get the AI to do what you want. With AI writing software like this, there will always be some redoing and reshaping to get the exact output you want, but working with the AI shouldn't feel like wrangling a loose horse. Similarly, great help docs and good onboarding were both a major plus.

Affordability. ChatGPT is currently free, and all these tools are built on top of an API that costs pennies . There was no hard and fast price limit, but the more expensive tools had to justify the extra expense with better features and a nicer app. After all, almost every app will produce pretty similar outputs regardless of what it costs.

Apps that weren't designed to make spam content. Previous text-generating tools could " spin " content by changing words to synonyms so that unscrupulous website owners could rip off copyrighted material and generally create lots of low-quality, low-value content. None of that on this list.

Even with these criteria, I had more than 40 different AI writing tools to test. Remember: it's relatively easy for a skilled developer to build a wrapper around the GPT API, so I had to dig deep into each one to find out if it was any good or just had a flashy marketing site.

I tested each app by getting it to write a number of different short- and long-form bits of copy, but as expected, there were very few meaningful quality differences. Instead, it was the overall user experience, depth of features, and affordability that determined whether an app made this list.

Zapier Chatbots lets you build custom AI chatbots and take action with built-in automation—no coding required. Try the writing assistant template to help you create high quality content, effortlessly.

The best AI writing generators at a glance

Best ai writing generator for businesses, jasper (web).

Jasper pros:

One of the most mature and feature-filled options on the list

Integrates with Grammarly, Surfer, and its own AI art generator

Jasper cons:

Expensive given that all the apps use similar language models

Jasper (formerly Jarvis) is one of the most feature-filled and powerful AI content generators. It was among the first wave of apps built on top of GPT, and its relative longevity means that it feels like a more mature tool than most of the other apps I tested. It's continued to grow and develop in the months since I first compiled this list.

If you have a business and budget isn't your primary concern, Jasper should be one of the first apps you try. It's pivoted to mostly focus on marketing campaigns rather than just generating generic AI content. That's not a bad thing, but it means that plans now start at $49/month for individual creators and $125/month for teams.

Jasper has also moved away from just being a GPT app. It claims to combine "several large language models" including GPT-4, Claude 2, and PaLM 2, so that "you get the highest quality outputs and superior uptime." While I can't say that I noticed a massive difference between Jasper's output and any other app's, it does give you a few solid controls so that your content matches your brand.

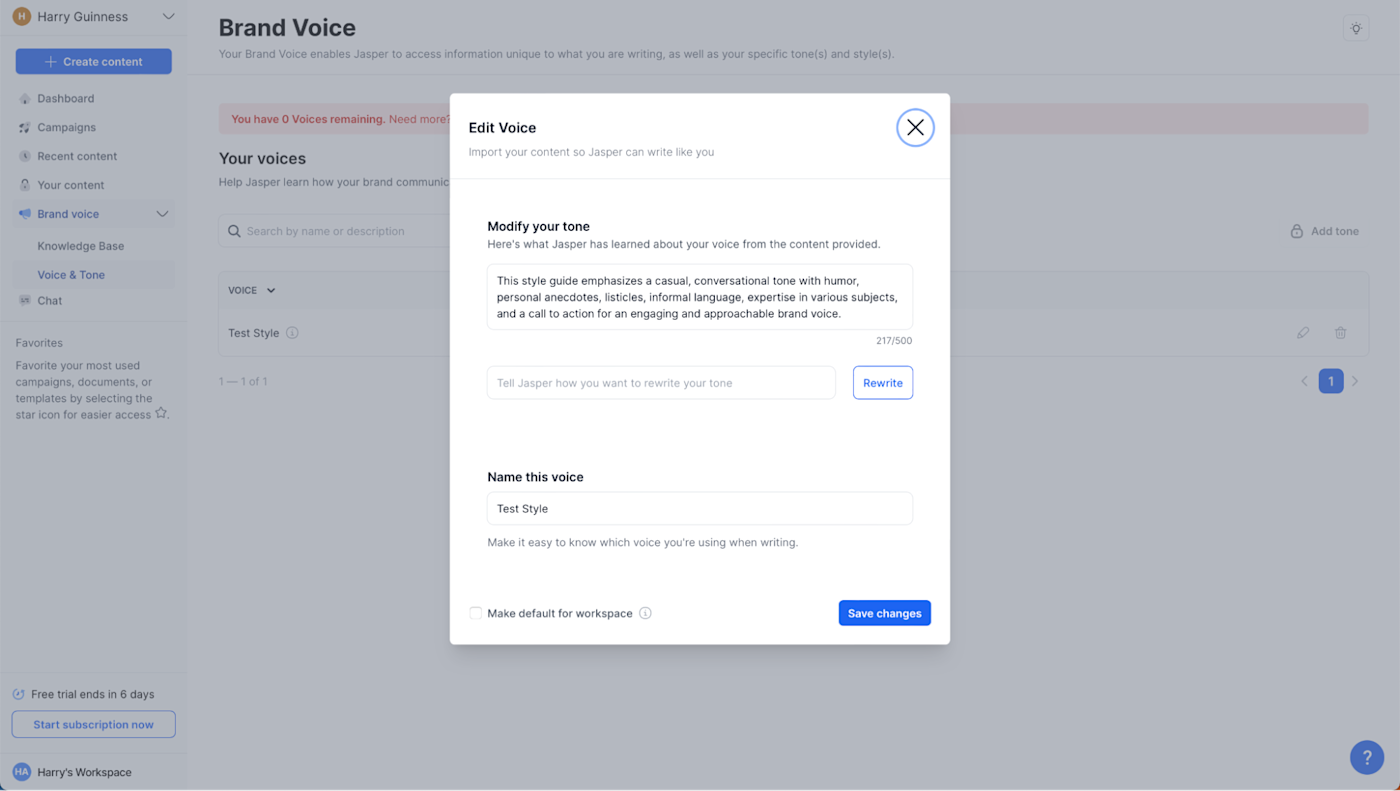

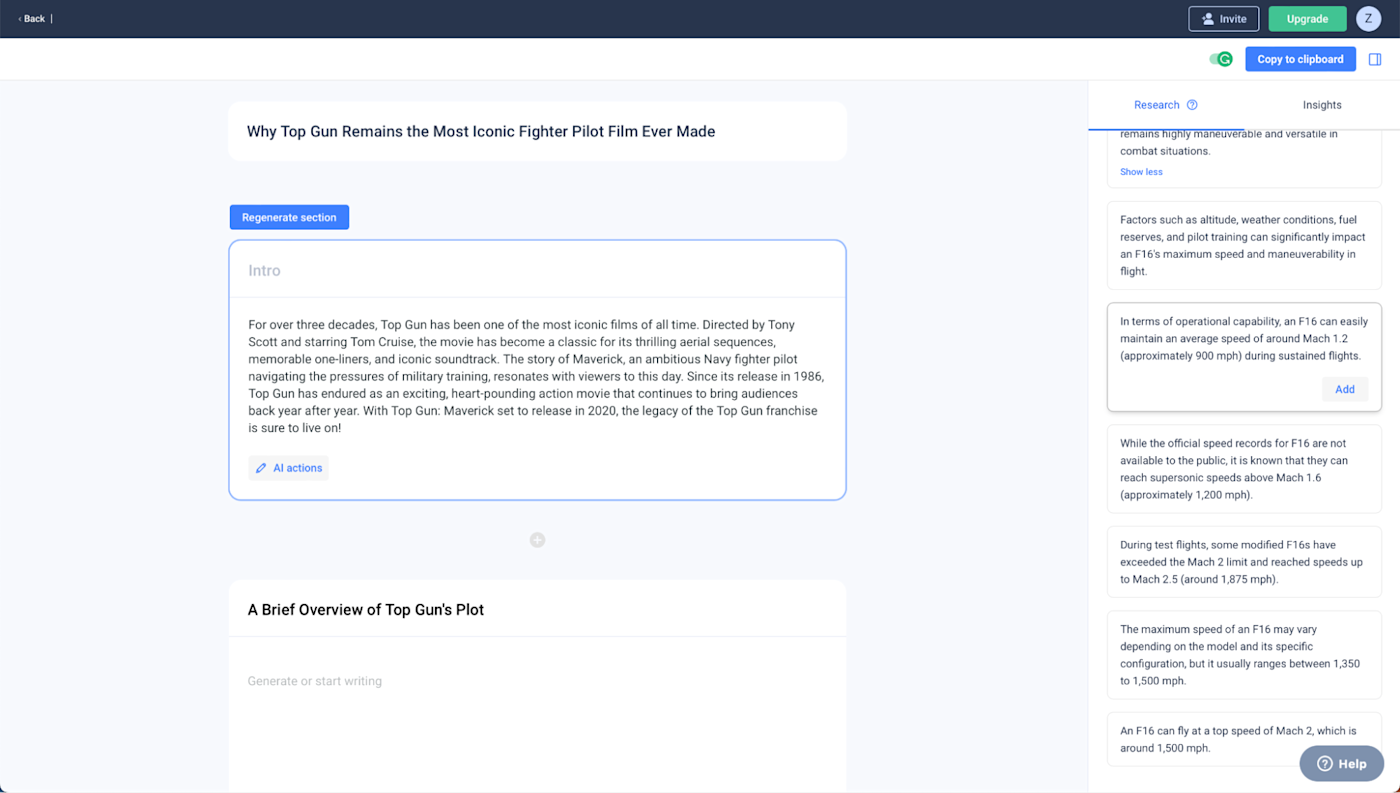

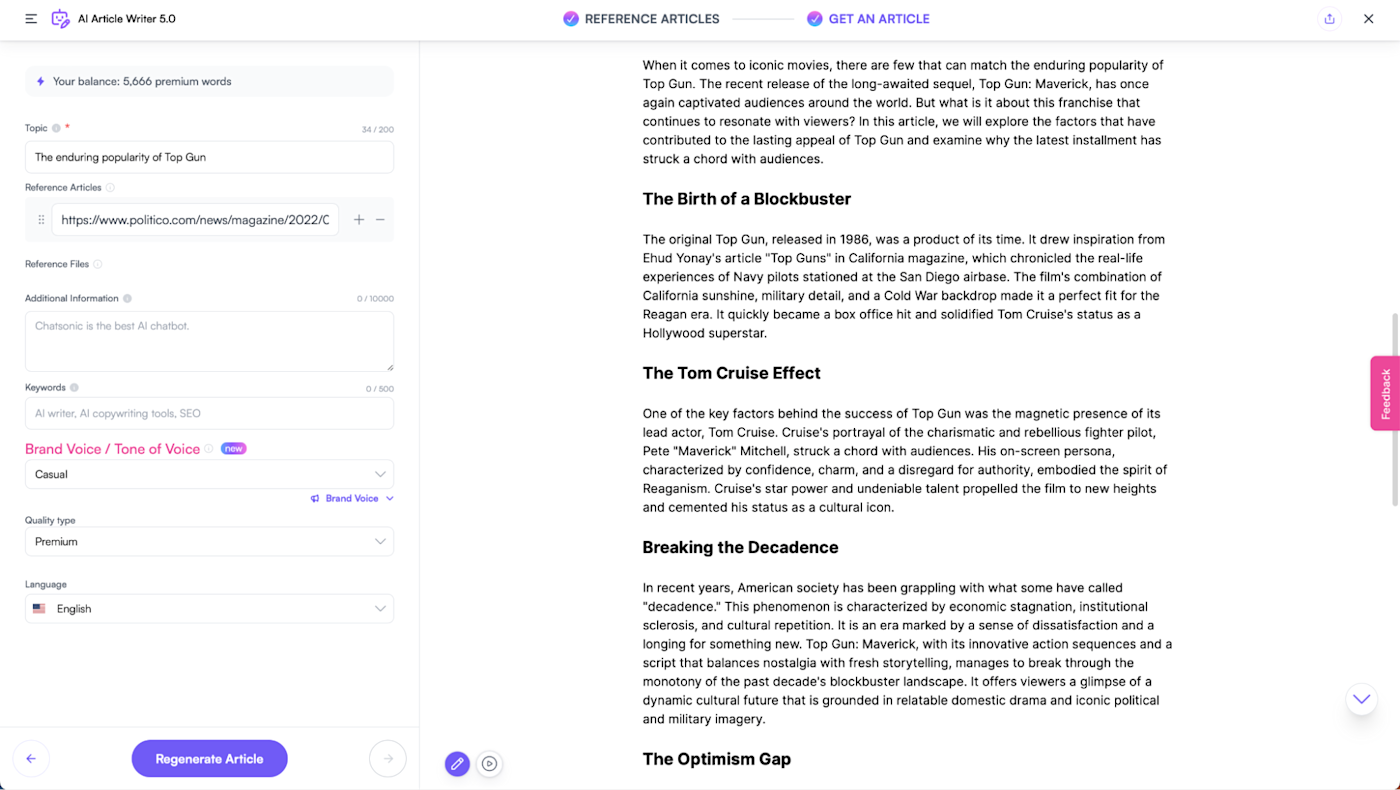

You can create a brand Voice and Tone by uploading some appropriate sample text. Based on a few examples of my writing, Jasper created a style that "emphasizes a casual, conversational tone with humor, personal anecdotes, listicles, informal language, expertise in various subjects, and a call to action for an engaging and approachable brand voice." I don't think that's a bad summary of the content I fed in, and its output for a few test blog posts like "The Enduring Popularity of Top Gun" felt closer to my writing than when I asked it to use a generic casual tone of voice. Similarly, there's a Knowledge Base where you can add facts about your business and products so Jasper gets important details right.

While other apps also offer similar features, Jasper's seemed to work better and are fully integrated with the rest of the app. For example, you can create entire marketing campaigns using your custom brand voice. Put a bit of work into fine-tuning it and uploading the right assets to your knowledge base, and I suspect that Jasper really could create some solid first drafts of marketing materials like blog outlines, social media campaign ads, and the like.

Otherwise, Jasper rounds things out with some nice integrations. It has a built-in ChatGPT competitor and AI art generator (though, again, lots of other apps have both), plays nice with the SEO app Surfer , and there's a browser extension to bring Jasper everywhere.

You can also connect Jasper to thousands of other apps using Zapier . Learn more about how to automate Jasper , or try one of the pre-built workflows below.

Create product descriptions in Jasper from new or updated Airtable records

Create Jasper blog posts from new changes to specific column values in monday.com and save the text in Google Docs documents

Run Jasper commands and send Slack channel messages with new pushed messages in Slack

Jasper pricing: Creator plan from $49/month with one brand voice and 50 knowledge assets. Teams plan starts at $125/month for three seats, three brand voices, and 150 knowledge assets.

Best AI writing app for AI copywriting

Copy.ai (web).

Copy.ai pros:

Has an affordable unlimited plan for high-volume users

Workflow actively solicits your input, which can lead to higher quality content

Copy.ai cons:

Expensive if you don't produce a lot of content

Pretty much anything Jasper can do, Copy.ai can do too. It has brand voices, an infobase, a chatbot, and team features (though there isn't a browser extension). Consider it the Burger King to Jasper's McDonalds.

And like the Home of the Whopper, Copy.ai appeals to slightly different tastes. While I could argue that Copy.ai has a nicer layout, the reality is it's geared toward a slightly different workflow. While Jasper lets you and the AI loose, Copy.ai slows things down a touch and encourages you to work with its chatbot or use a template that asks some deliberate, probing questions. For creating website copy, social media captions , product descriptions, and similarly specific things, it makes more sense. But for content marketing blog posts and other long-form content, it might annoy you.

The other big difference is the pricing. While both offer plans for $49/month, Copy.ai includes five user seats and unlimited brand voices. For a small team working with multiple brands, it can be a lot cheaper. Also, if you're looking for a free AI writing generator, Copy.ai also offers a free plan that includes 2,000 words per month.

Overall, there are more similarities than differences between Jasper and Copy.ai , and both can create almost all the same kinds of text. Even when it came to analyzing my voice, they both came to pretty similar conclusions. Copy.ai decided that, to mimic me, it had to "focus on creating content that is both educational and entertaining, using a conversational tone that makes readers feel like they're having a chat with a knowledgeable friend" and "not to be afraid to inject some humor or personal anecdotes." If you're in doubt, try them both out and then decide.

Copy.ai also integrates with Zapier , so you can do things like automatically sending content to your CMS or enriching leads straight from your CRM. Learn more about how to automate Copy. ai or try one of the pre-built workflows below.

Add new blog posts created with Copy.ai to Webflow

Copy.ai pricing: Free for 2,000 words per month; from $49/month for the Pro plan with 5 users and unlimited brand voices.

Best AI writing assistant

Anyword (web).

Anyword pros:

Makes it very easy for you to include specific details, SEO keywords, and other important information

Engagement scores and other metrics are surprisingly accurate

Anyword cons:

Can be slower to use

Pretty expensive for a more limited set of features than some of the other apps on this list

While you can direct the AI to include certain details and mention specific facts for every app on this list, none make it as easy as Anyword. More than any of the others, the AI here feels like an eager and moderately competent underling that requires a bit of micromanaging (and can also try to mimic your writing style and brand voice), rather than a beast that you have to tame with arcane prompts.

Take one of its main content-generating tools: the Blog Wizard. Like with Copy.ai, the setup process requires you to describe the blog post you want the AI to create and add any SEO keywords you want to target. Anyword then generates a range of titles for you to choose from, along with a predicted engagement score.

Once you've chosen a title—or written your own—it generates a suggested outline. Approve it, and you get the option for it to create an entire ~2,000-word blog post (boo!) or a blank document where you can prompt it with additional instructions for each section of the outline, telling it things like what facts to mention, what style to take, and what details to cover. There's also a chatbot-like research sidebar that you can ask questions of and solicit input from. While certainly a slower process than most apps, it gives you a serious amount of control over the content you're creating.

Anyword is definitely aimed at marketers, and its other tools—like the Data-Driven Editor and the Website Targeted Message—all allow you to target your content toward specific audiences and give things engagement scores. While I certainly can't confirm the validity of any of these scores, they at least pass the sniff test. I generally thought the AI-generated content that Anyword scored higher was better—and even when I disagreed, I still liked one of the top options.

Anyword pricing: Starter plan from $49/month for 1 user and 1 brand voice.

Best AI writing tool for writing fiction

Sudowrite (web).

Sudowrite pros:

The only AI tool on the list explicitly aimed at writing fiction

Super fun to use if you've ever wanted to play around with fiction

Sudowrite cons:

It's still an AI text generator, so it can produce nonsensical metaphors, clichéd plots, incoherent action, and has a short memory for details

Very controversial in fiction writing circles

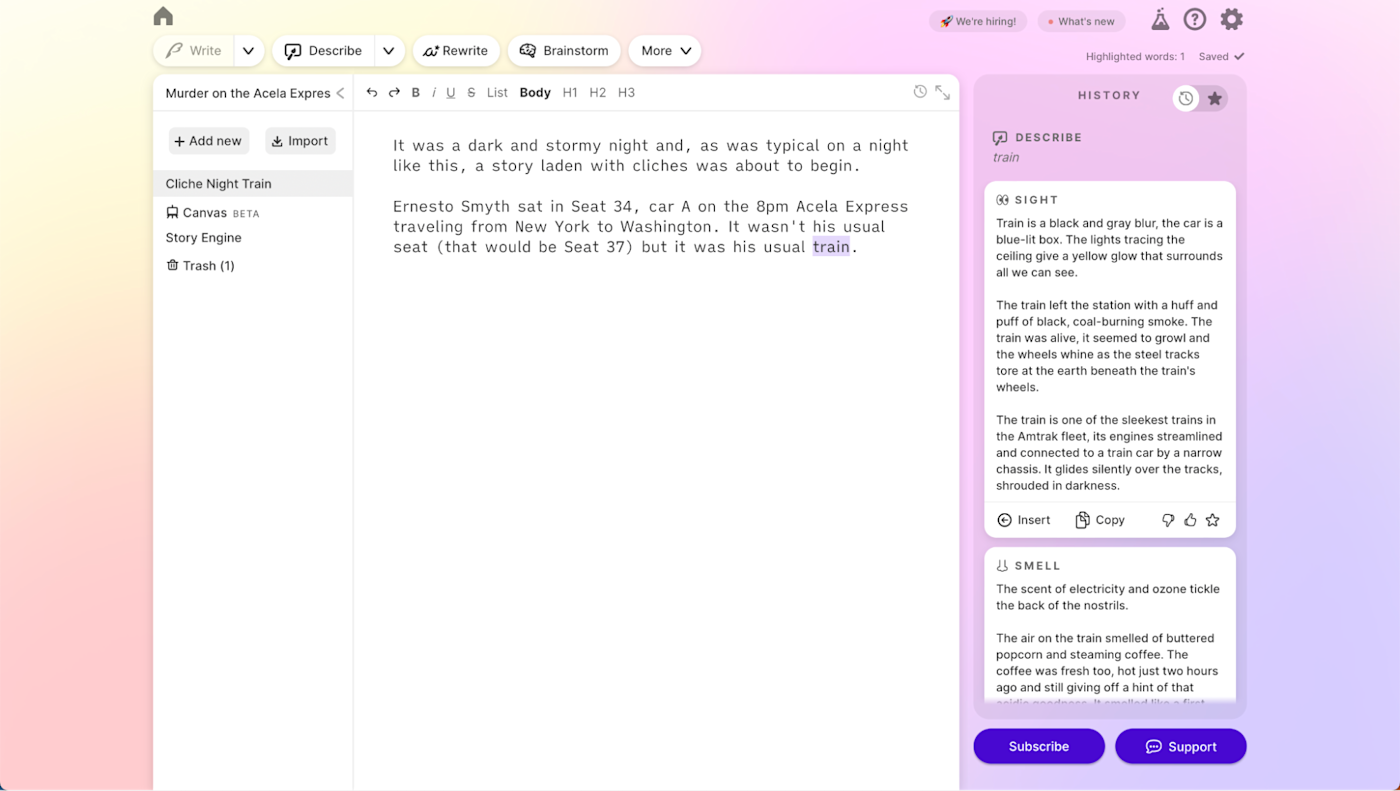

When I saw Sudowrite's marketing copy, I didn't think for a second it would make it onto this list. Then I tried it and…I kind of love it. Sudowrite is a totally different tool than all the others on this list because it's aimed at fiction writers. And with that, comes a lot of controversy. Sudowrite has been called " an insult to writers everywhere " and has been generally dismissed as a tool for hacks by a lot of Very Online writers. And while it's true that it's nowhere close to replacing a human author, it's fun, functional, and can genuinely help with writing a work of fiction.

The Story Engine feature, which allows you to generate a full work of fiction over a few days by progressively generating each story beat, has attracted the most attention ( it works but takes lots of hand-holding and your novel will be weird ). But I prefer its assistive tools.

Let's start with Describe. Select a word or phrase, click Describe , and the AI will generate a few suggestions for the sight, smell, taste, sound, and touch of the thing, as well as a couple of metaphors. If you're the kind of writer who struggles to add sensory depth to your short stories, it can help you get into the habit of describing things in more interesting ways.

Then there's Brainstorm. It allows you to use the AI to generate possible dialogue options, character names and traits, plot points, places, and other details about your world from your descriptions and cues. If you know you want a big hairy guy with a huge sword but can't think of a good name, it can suggest a few, like Thorgrim and Bohart.

And these are just scratching the surface. Sure, if you over-rely on the AI to solve all your problems, you'll probably end up with an impressively generic story. But if you use it as a writing buddy to bounce ideas off and get you out of a rut, it's got serious potential.

Best of all, Sudowrite is super easy to use. The onboarding, tool tips, and general helpful vibe of the app are something other developers could learn from.

Sudowrite pricing: Hobby & Student plan from $19/month for 30,000 AI words/month.

Best AI text generator for a non-GPT option

Writer (web).

Writer pros:

Not based on GPT, so free of a lot of the controversy surrounding LLMs

Surprisingly capable as an editor, making sure your team sticks to the style guide and doesn't make any wild claims

Writer cons:

Requires a lot more setup to get the most from

GPT comes with quite a lot of baggage. OpenAI has been less than transparent about exactly what data was used to create the various versions of GPT-3 and GPT-4, and it's facing various lawsuits over the use of copyrighted material in its training dataset. No one is really denying that protected materials— potentially from pirated databases —were used to train GPT; the question is just whether or not it falls under fair use.

For most people, this is a nebulous situation filled with edge cases and gray areas. Realistically, it's going to be years before it's all sorted out, and even then, things will have moved on so far that the results of any lawsuit are likely to be redundant. But for businesses that want to use AI writing tools without controversy attached, GPT is a no-go—and will be for the foreseeable future.

Which is where Writer comes in.

Feature-wise, Writer is much the same as any of my top picks. (Though creating a specific brand voice that's automatically used is an Enterprise-only feature; otherwise, you have to use a lot of checkboxes in the settings to set the tone.) Some features, like the chatbot, are a little less useful than they are in the GPT-powered apps, but really, they're not why you'd choose Writer.

Where it stands out is the transparency around its Palmyra LLM . For example, you can request and inspect a copy of its training dataset that's composed of data that is "distributed free of any copyright restrictions." Similarly, Palmyra's code and model weights (which determines its outputs) can be audited, it can be hosted on your own servers, and your data is kept secure and not used for training by default. As an AI-powered tool, it's as above board as it comes.

In addition to generating text, Writer can work as a company-specific Grammarly-like editor, keeping on top of legal compliance, ensuring you don't make any unsupported claims, and checking that everything matches your style guide—even when humans are writing the text. As someone who routinely has to follow style guides, this seems like an incredibly useful feature. I wasn't able to test it fully since I don't have a personal style guide to input, but Writer correctly fixed things based on all the rules that I set.

In side-by-side comparisons, Writer's text generations sometimes felt a little weaker than the ones from Jasper or Copy.ai, but I suspect a lot of that was down to how things were configured. Writer is designed as a tool for companies to set up and train with their own data, not run right out of the box. I'd guess my random blog posts were a poor test of how it should be used in the real world.

Writer also integrates with Zapier , so you can use Writer to create content directly from whatever apps you use most. Learn more about how to automate Writer , or take a look at these pre-made workflows.

Create new outlines or drafts in Writer based on briefs from Asana

Generate marketing content from project briefs in Trello

Writer pricing: Team from $18/user/month for up to 5 users; after that, it's an Enterprise plan.

Best AI text generator for GPT-4 content

Writesonic (web).

Writesonic pros:

Allows you to select what GPT model is used to generate text

Generous free plan and affordable paid plans

Writesonic cons:

A touch too focused on SEO content for my taste

While almost all the tools on this list use GPT, most are pretty vague about which particular version of it they use at any given time. This matters because the most basic version of the GPT-3.5 Turbo API costs $0.002/1K tokens (roughly 750 words), while GPT-4 starts at $0.06/1K tokens, and the most powerful version costs $0.12/1K tokens. All this suggests that most apps may not use GPT-4 in all circumstances, and instead probably rely on one of the more modest (though still great) GPT-3 models for most text generation.

If having the latest and greatest AI model matters to you, Writesonic is the app for you. Writesonic doesn't hide what AI model it uses. It even allows you to choose between using GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, at least on Business plans.

Whether the content you create will benefit from the extra power of GPT-4 or not depends. In my experience using GPT-4 through ChatGPT, the latest model is more accurate and, essentially, more sensible in how it responds. If you're churning out low-stakes copy variations for your product listings, you likely won't see much improvement. On the other hand, for long-form original blog posts, it could make a difference. Either way, the transparency in which model you're using at any given time is a huge bonus.

Feature-wise, Writesonic is much the same as any of the other apps on this list, with a Google Docs-style editor, the option to set a brand voice, a few dozen copy templates, a chatbot, a browser extension, and Surfer integration. It's cool that you can set reference articles when you're generating a blog post, but it introduces the real possibility of inadvertent plagiarism if you aren't careful with how you use it. (Its most offbeat feature is a surprisingly solid AI-powered custom chatbot builder that's due to be spun out into its own app soon.) Overall, it's pretty nice to use and skews more toward SEO-optimized content marketing—but like with all the apps, you can use it to generate whatever you want.

Writesonic also integrates with Zapier , so you can send new copy to any of the other apps you use in your writing workflow. Learn more about how to automate Writesonic , or get started with one of these examples.

Create a Google Doc with new content from Writesonic

Generate product descriptions with Writesonic from spreadsheet rows in Google Sheets

Writesonic pricing: Free for 10,000 GPT-3.5 words per month; Business from $19/month for 200,000 Premium words or 33,333 GPT-4 words.

Best free AI writing generator (with affordable upgrades)

A solid free plan and a cheap high-volume plan (though Writesonic offers better value for an unlimited plan)

It includes a basic AI art generator as part of every plan

The app is more basic than more expensive offerings

Unlimited plan isn't very competitive

Most of the apps on this list are aimed at professionals, businesses, and anyone else with a budget. The Jasper, Copy.ai, and Anyword plans I considered all started at $49/month. That isn't exactly a hobbyist-friendly sum of money, so if you want to explore AI text generators without spending as much, give Rytr a go.

There's a free plan that's good for 10,000 characters (around 2,500 words) per month, and it includes a lot of the features, like a plagiarism checker, and a few AI-generated images. The Saver plan starts at $9/month and allows you to generate 100,000 characters (around 25,000 words) per month. On that plan, you're also able to generate up to 20 images a month, which many other apps charge extra for. (There's also an unlimited plan for $29/month, but at that point, Writesonic is a better value.)

Feature-wise, there are some trade-offs. Rytr is a little less competent at generating long-form content without you guiding it through the process, and there are fewer templates for specific things. The interface also isn't as polished, and there isn't as much hand-holding to get you started. Still, as Rytr is using GPT like almost all the other apps on this list, you should be able to get it to produce substantially similar output.

Rytr Pricing: Free plan for 10,000 characters/month and lots of other features; Saver plan from $9/month for 100,000 characters; Unlimited plan from $29/month.

Other AI writing tools to consider

With so many AI text-generating tools out there, a few good ones worth considering didn't make this list, only because they didn't meet my initial criteria in some way. If none of the AI writers I chose fit the bill for you, here are a few other options worth looking into:

ChatGPT is surprisingly competent and fun to use. And best of all, it's free. ( Google Bard is a little less excellent on the content production side.)

Wordtune and Grammarly are both great tools for editing and improving your own writing . GrammarlyGO just isn't as flexible as my other picks.

Notion AI adds a powerful AI tool directly into Notion. If you already use Notion, it's worth checking out, but it's a lot to learn if you just want a text generator. (Same goes for AI within any other Notion alternative, like Coda AI .)

Surfer and Frase are both AI-powered SEO tools . They fell slightly out of scope for this list, but they can both help you optimize and improve your content—AI-generated or not.

All of the apps on this list offer at the very least a free trial, so I'd suggest trying some of them out for a few minutes until you find the one that seems to work best with your workflow.

Related reading:

How to use OpenAI's GPT to spark content ideas

How to create an AI writing coach with GPT and Zapier

8 ways real businesses are using AI for content creation

How to detect AI-generated content

The best AI marketing tools

This article was originally published in April 2023. The most recent update was in September 2023.

Get productivity tips delivered straight to your inbox

We’ll email you 1-3 times per week—and never share your information.

Harry Guinness

Harry Guinness is a writer and photographer from Dublin, Ireland. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Lifehacker, the Irish Examiner, and How-To Geek. His photos have been published on hundreds of sites—mostly without his permission.

- Artificial intelligence (AI)

- Media and editorial

- Content marketing

Related articles

40+ best digital marketing tools in 2024

The 12 best productivity apps for iPad in 2024

The 12 best productivity apps for iPad in...

The 4 best journal apps in 2024

The 8 best Trello alternatives in 2024

Improve your productivity automatically. Use Zapier to get your apps working together.

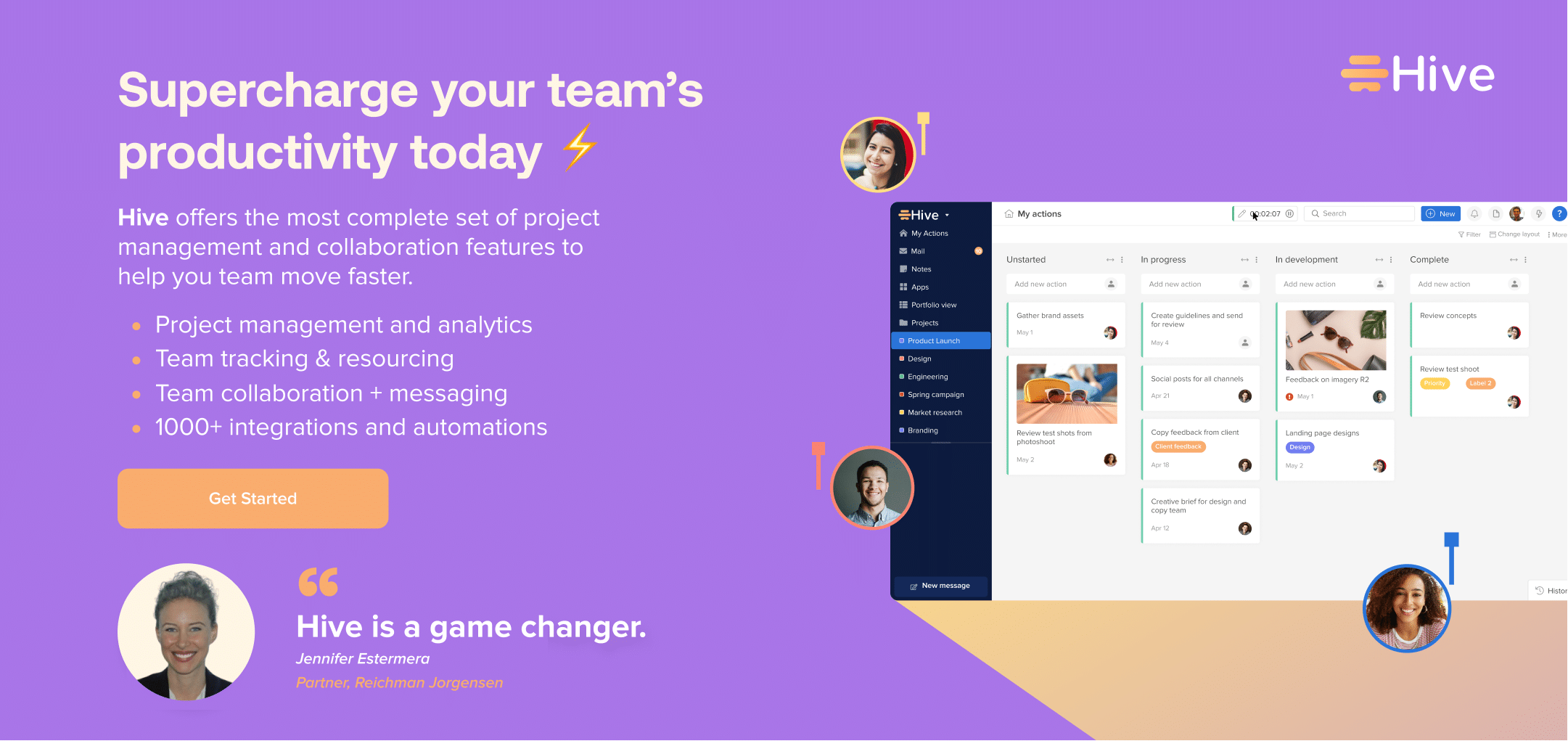

- Project management Track your team’s tasks and projects in Hive

- Time tracking Automatically track time spent on Hive actions

- Goals Set and visualize your most important milestones

- Collaboration & messaging Connect with your team from anywhere

- Forms Gather feedback, project intake, client requests and more

- Proofing & Approvals Streamline design and feedback workflows in Hive

- See all features

- Analytics Gain visibility and gather insights into your projects

- Automations Save time by automating everyday tasks

- Hive Apps Connect dozens of apps to streamline work from anywhere

- Integrations Sync Hive with your most-used external apps

- Templates Quick-start your work in Hive with pre-built templates

- Download Hive Access your workspace on desktop or mobile

- Project management Streamline initiatives of any size & customize your workflow by project

- Resource management Enable seamless resourcing and allocation across your team

- Project planning Track and plan all upcoming projects in one central location

- Time tracking Consolidate all time tracking and task management in Hive

- Cross-company collaboration Unite team goals across your organization

- Client engagement Build custom client portals and dashboards for external use

- All use cases

- Enterprise Bring your organization into one unified platform

- Agency Streamline project intake, project execution, and client comms

- University Marketing Maximize value from your marketing and admissions workflows with Hive

- Nonprofits Seamless planning, fundraising, event execution and more

- Marketing Streamline your marketing projects and timelines

- Business operations Track and optimize strategic planning and finance initiatives

- Education Bring your institutions’ planning, fundraising, and more into Hive

- Design Use Hive to map out and track all design initiatives and assets

- On-demand demo Access a guided walk through Hive

- Customers More on how Teams are using Hive now

- FAQ & support articles Find answers to your most asked questions

- Hive University Become a Hive expert with our free Hive U courses

- Webinars Learn about Hive’s latest features

- Hive Community Where members discuss and answer questions in the community

- Professional Services Get hands-on help from our Professional Services team

- Hive Partners Explore partners services or join as a partner

- FEATURED WEBINAR

Power Your Progress with Analytics in Hive

MediaLink's Will will take us through their organization's use of Hive Analytics and how it has helped power their agency progress.

- Request Demo

- Get Started

- Project management

- How teams work in Hive

- Productivity

- Remote and hybrid work

The 13 Best AI Writing Tools For Essays, Blogs & Content in 2024

- Julie Simpson

- February 23, 2024

If you have recently spent time on popular social media channels such as Twitter or LinkedIn, chances are you have read all about the amazing benefits of artificial intelligence for writing — but you’ve probably seen the “will AI replace all of our jobs” looming around the web as well. All of the pros and cons of AI writing tools can be hard to keep track of.

However, as a productivity platform whose ultimate goal is to help you work more efficiently, we believe that AI writing is here to stay — and here to help. As much as we can see the other side of the argument (not the machines taking over, but the stealing our jobs argument), AI can ultimately be used as a tool to help you do your job better, not completely take it over from you.

We are firmly in the camp that using AI for content creation can be highly beneficial. If you are also interested in how AI tools can maximize your content output, follow along to learn about the best AI writing tools and how you can implement them into your workflow today.

How to pick the best AI writing tool for your content

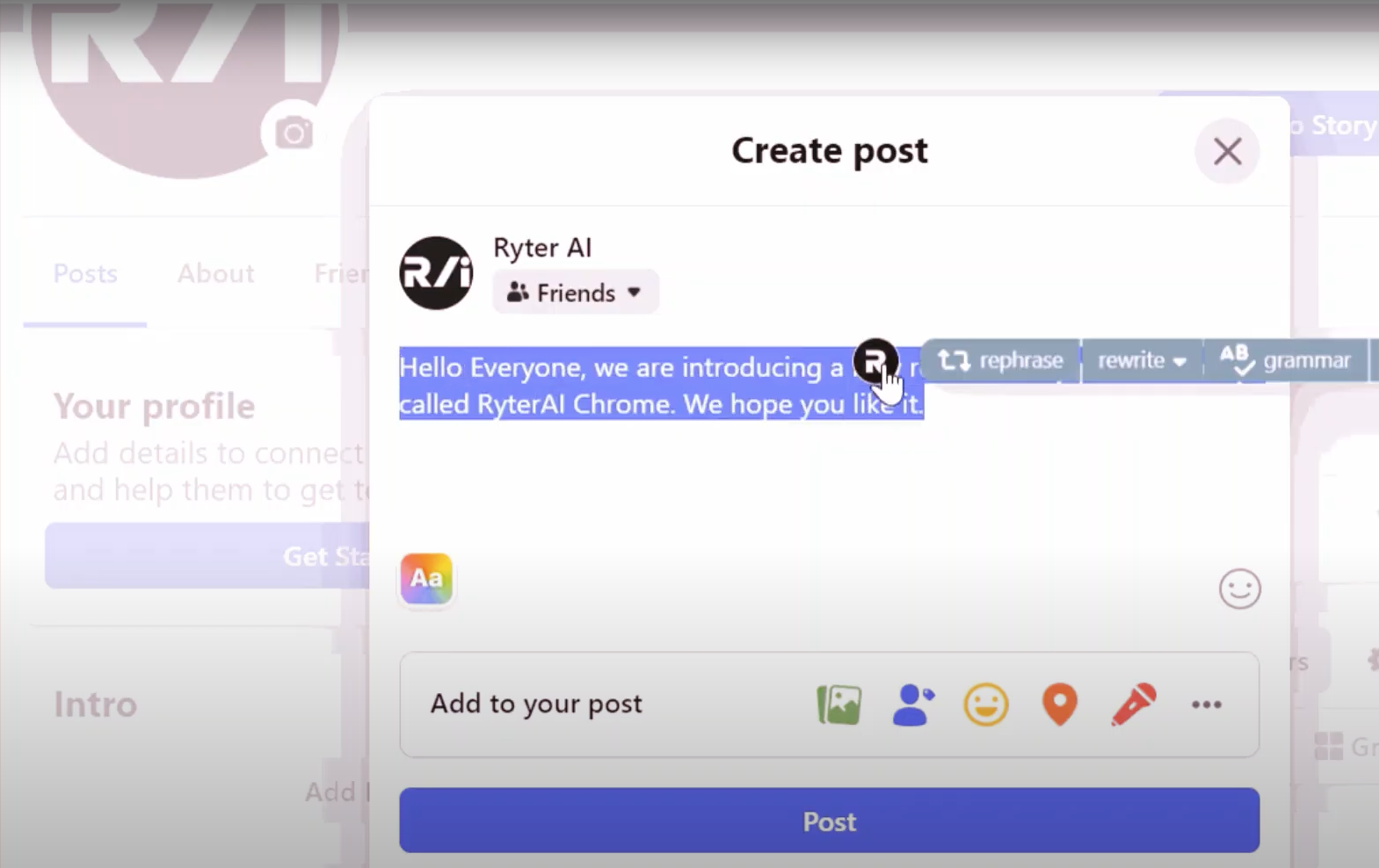

HiveMind and RyterAI and JasperAI, Oh my!

While it doesn’t have the same ring as lions, tigers, and bears, it still brings forth the same apprehension that Dorothy Gale from the Wizard of Oz felt: the fear of the unknown and so many to choose from. So w here do you start?

If you are overwhelmed by all the AI writing tools on the market today, and their use cases are all blurring together, here are my top AI tools that are definite content contenders.

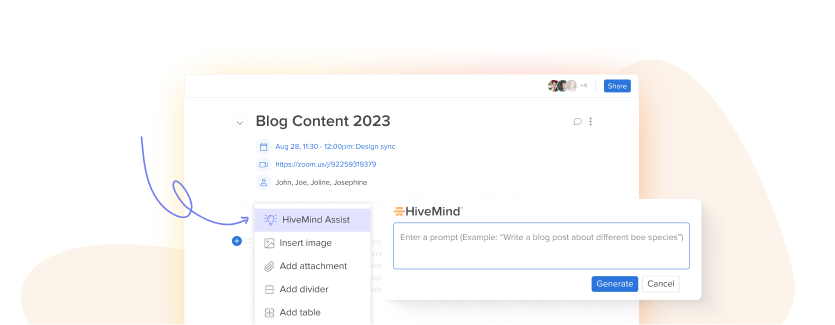

1. HiveMind