Assignment of Rights and Obligations under a Contract Philippines

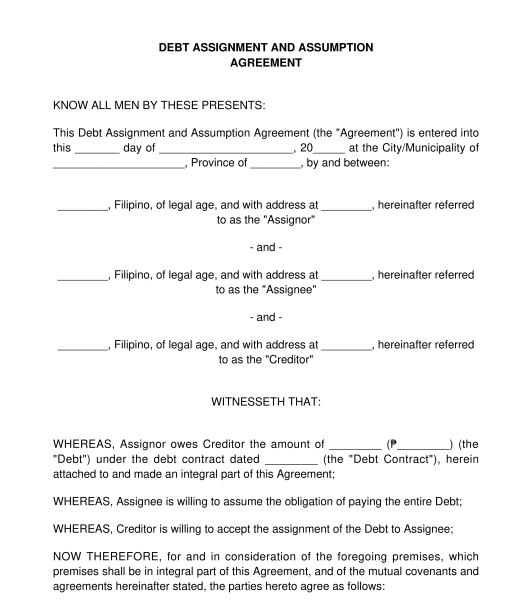

When entering into a contract, it is important to understand the assignment of rights and obligations. This refers to the transfer of these rights and obligations from one party to another. In the Philippines, the assignment of rights and obligations under a contract is governed by law and there are certain procedures that must be followed.

Firstly, it is important to understand what constitutes a right or obligation under a contract. A right is a legal entitlement to something, while an obligation is a duty or responsibility that a party has agreed to fulfill under the terms of the contract. These can include things such as payment obligations, delivery obligations, intellectual property rights, or the right to terminate the contract.

Once these rights and obligations have been identified, they can be assigned to another party. In the Philippines, this assignment must be done in writing and must be signed by both parties. The written agreement should clearly identify the parties involved, the rights and obligations being assigned, and the terms and conditions of the assignment.

It is also important to note that certain rights and obligations may not be assignable. For example, personal rights such as the right to use a trademark, or obligations that are specific to a particular person may not be assignable without the consent of the other party.

In addition to the written agreement, the parties should also take steps to notify any other relevant parties of the assignment. This could include notifying customers, suppliers, or other stakeholders. Failure to properly notify these parties could result in legal issues down the line.

Overall, the assignment of rights and obligations under a contract in the Philippines is a complex process that requires careful consideration and attention to detail. It is important to involve legal professionals to ensure that the assignment is done in accordance with the law and that all parties involved are fully aware of their rights and obligations. By doing so, you can avoid potential legal disputes and ensure that your business runs smoothly.

This entry was posted on May 30, 2023, 10:18 am and is filed under Uncategorized. You can follow any responses to this entry through RSS 2.0 . Responses are currently closed, but you can trackback from your own site.

Comments are closed.

- No categories

- Documentation

- Suggest Ideas

- Support Forum

- WordPress Blog

- WordPress Planet

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (7)

- July 2023 (1)

- June 2023 (5)

- May 2023 (4)

- April 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (4)

- February 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (1)

- December 2022 (2)

- November 2022 (6)

- October 2022 (2)

- September 2022 (1)

- August 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (5)

- May 2022 (8)

- April 2022 (2)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (5)

- January 2022 (7)

- December 2021 (3)

- November 2021 (5)

- October 2021 (6)

- Valid XHTML

- Ph: 860-572-7306

- Fax: 860-536-5325

- [email protected]

- Copyright © 2011 Peter J. Springsteel Architect LLC - All Rights Reserved

PHILIPPINE CIVIL LAW

This web page contains the Book IV o f Republic Act No. 386 June 18, 1949 The Civil Code of the Philippines AN ACT TO ORDAIN AND INSTITUTE THE CIVIL CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES

BOOK IV OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS Title. I. - OBLIGATIONS CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS

Art. 1157. Obligations arise from:

(2) Contracts;

(3) Quasi-contracts;

(4) Acts or omissions punished by law; and

(5) Quasi-delicts. (1089a)

Art. 1159. Obligations arising from contracts have the force of law between the contracting parties and should be complied with in good faith. (1091a)

Art. 1160. Obligations derived from quasi-contracts shall be subject to the provisions of Chapter 1, Title XVII, of this Book. (n)

Art. 1161. Civil obligations arising from criminal offenses shall be governed by the penal laws, subject to the provisions of Article 2177, and of the pertinent provisions of Chapter 2, Preliminary Title, on Human Relations, and of Title XVIII of this Book, regulating damages. (1092a)

Art. 1162. Obligations derived from quasi-delicts shall be governed by the provisions of Chapter 2, Title XVII of this Book, and by special laws. (1093a)

Art. 1164. The creditor has a right to the fruits of the thing from the time the obligation to deliver it arises. However, he shall acquire no real right over it until the same has been delivered to him. (1095)

Art. 1165. When what is to be delivered is a determinate thing, the creditor, in addition to the right granted him by Article 1170, may compel the debtor to make the delivery.

If the thing is indeterminate or generic, he may ask that the obligation be complied with at the expense of the debtor.

If the obligor delays, or has promised to deliver the same thing to two or more persons who do not have the same interest, he shall be responsible for any fortuitous event until he has effected the delivery. (1096)

Art. 1166. The obligation to give a determinate thing includes that of delivering all its accessions and accessories, even though they may not have been mentioned. (1097a)

Art. 1167. If a person obliged to do something fails to do it, the same shall be executed at his cost.

This same rule shall be observed if he does it in contravention of the tenor of the obligation. Furthermore, it may be decreed that what has been poorly done be undone. (1098)

Art. 1168. When the obligation consists in not doing, and the obligor does what has been forbidden him, it shall also be undone at his expense. (1099a)

Art. 1169. Those obliged to deliver or to do something incur in delay from the time the obligee judicially or extrajudicially demands from them the fulfillment of their obligation.

However, the demand by the creditor shall not be necessary in order that delay may exist:

(2) When from the nature and the circumstances of the obligation it appears that the designation of the time when the thing is to be delivered or the service is to be rendered was a controlling motive for the establishment of the contract; or

(3) When demand would be useless, as when the obligor has rendered it beyond his power to perform.

Art. 1170. Those who in the performance of their obligations are guilty of fraud, negligence, or delay, and those who in any manner contravene the tenor thereof, are liable for damages. (1101)

Art. 1171. Responsibility arising from fraud is demandable in all obligations. Any waiver of an action for future fraud is void. (1102a)

Art. 1172. Responsibility arising from negligence in the performance of every kind of obligation is also demandable, but such liability may be regulated by the courts, according to the circumstances. (1103)

Art. 1173. The fault or negligence of the obligor consists in the omission of that diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the place. When negligence shows bad faith, the provisions of Articles 1171 and 2201, paragraph 2, shall apply.

If the law or contract does not state the diligence which is to be observed in the performance, that which is expected of a good father of a family shall be required. (1104a)

Art. 1174. Except in cases expressly specified by the law, or when it is otherwise declared by stipulation, or when the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk, no person shall be responsible for those events which could not be foreseen, or which, though foreseen, were inevitable. (1105a)

Art. 1175. Usurious transactions shall be governed by special laws. (n)

Art. 1176. The receipt of the principal by the creditor without reservation with respect to the interest, shall give rise to the presumption that said interest has been paid.

The receipt of a later installment of a debt without reservation as to prior installments, shall likewise raise the presumption that such installments have been paid. (1110a)

Art. 1177. The creditors, after having pursued the property in possession of the debtor to satisfy their claims, may exercise all the rights and bring all the actions of the latter for the same purpose, save those which are inherent in his person; they may also impugn the acts which the debtor may have done to defraud them. (1111)

Art. 1178. Subject to the laws, all rights acquired in virtue of an obligation are transmissible, if there has been no stipulation to the contrary. (1112)

Every obligation which contains a resolutory condition shall also be demandable, without prejudice to the effects of the happening of the event. (1113)

Art. 1180. When the debtor binds himself to pay when his means permit him to do so, the obligation shall be deemed to be one with a period, subject to the provisions of Article 1197. (n)

Art. 1181. In conditional obligations, the acquisition of rights, as well as the extinguishment or loss of those already acquired, shall depend upon the happening of the event which constitutes the condition. (1114)

Art. 1182. When the fulfillment of the condition depends upon the sole will of the debtor, the conditional obligation shall be void. If it depends upon chance or upon the will of a third person, the obligation shall take effect in conformity with the provisions of this Code. (1115)

Art. 1183. Impossible conditions, those contrary to good customs or public policy and those prohibited by law shall annul the obligation which depends upon them. If the obligation is divisible, that part thereof which is not affected by the impossible or unlawful condition shall be valid.

The condition not to do an impossible thing shall be considered as not having been agreed upon. (1116a)

Art. 1184. The condition that some event happen at a determinate time shall extinguish the obligation as soon as the time expires or if it has become indubitable that the event will not take place. (1117)

Art. 1185. The condition that some event will not happen at a determinate time shall render the obligation effective from the moment the time indicated has elapsed, or if it has become evident that the event cannot occur.

If no time has been fixed, the condition shall be deemed fulfilled at such time as may have probably been contemplated, bearing in mind the nature of the obligation. (1118)

Art. 1186. The condition shall be deemed fulfilled when the obligor voluntarily prevents its fulfillment. (1119)

Art. 1187. The effects of a conditional obligation to give, once the condition has been fulfilled, shall retroact to the day of the constitution of the obligation. Nevertheless, when the obligation imposes reciprocal prestations upon the parties, the fruits and interests during the pendency of the condition shall be deemed to have been mutually compensated. If the obligation is unilateral, the debtor shall appropriate the fruits and interests received, unless from the nature and circumstances of the obligation it should be inferred that the intention of the person constituting the same was different.

In obligations to do and not to do, the courts shall determine, in each case, the retroactive effect of the condition that has been complied with. (1120)

Art. 1188. The creditor may, before the fulfillment of the condition, bring the appropriate actions for the preservation of his right.

The debtor may recover what during the same time he has paid by mistake in case of a suspensive condition. (1121a)

Art. 1189. When the conditions have been imposed with the intention of suspending the efficacy of an obligation to give, the following rules shall be observed in case of the improvement, loss or deterioration of the thing during the pendency of the condition:

(2) If the thing is lost through the fault of the debtor, he shall be obliged to pay damages; it is understood that the thing is lost when it perishes, or goes out of commerce, or disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown or it cannot be recovered;

(3) When the thing deteriorates without the fault of the debtor, the impairment is to be borne by the creditor;

(4) If it deteriorates through the fault of the debtor, the creditor may choose between the rescission of the obligation and its fulfillment, with indemnity for damages in either case;

(5) If the thing is improved by its nature, or by time, the improvement shall inure to the benefit of the creditor;

(6) If it is improved at the expense of the debtor, he shall have no other right than that granted to the usufructuary. (1122)

In case of the loss, deterioration or improvement of the thing, the provisions which, with respect to the debtor, are laid down in the preceding article shall be applied to the party who is bound to return.

As for the obligations to do and not to do, the provisions of the second paragraph of Article 1187 shall be observed as regards the effect of the extinguishment of the obligation. (1123)

Art. 1191. The power to rescind obligations is implied in reciprocal ones, in case one of the obligors should not comply with what is incumbent upon him.

The injured party may choose between the fulfillment and the rescission of the obligation, with the payment of damages in either case. He may also seek rescission, even after he has chosen fulfillment, if the latter should become impossible.

The court shall decree the rescission claimed, unless there be just cause authorizing the fixing of a period.

This is understood to be without prejudice to the rights of third persons who have acquired the thing, in accordance with Articles 1385 and 1388 and the Mortgage Law. (1124)

Art. 1192. In case both parties have committed a breach of the obligation, the liability of the first infractor shall be equitably tempered by the courts. If it cannot be determined which of the parties first violated the contract, the same shall be deemed extinguished, and each shall bear his own damages. (n)

Obligations with a resolutory period take effect at once, but terminate upon arrival of the day certain.

A day certain is understood to be that which must necessarily come, although it may not be known when.

If the uncertainty consists in whether the day will come or not, the obligation is conditional, and it shall be regulated by the rules of the preceding Section. (1125a)

Art. 1194. In case of loss, deterioration or improvement of the thing before the arrival of the day certain, the rules in Article 1189 shall be observed. (n)

Art. 1195. Anything paid or delivered before the arrival of the period, the obligor being unaware of the period or believing that the obligation has become due and demandable, may be recovered, with the fruits and interests. (1126a)

Art. 1196. Whenever in an obligation a period is designated, it is presumed to have been established for the benefit of both the creditor and the debtor, unless from the tenor of the same or other circumstances it should appear that the period has been established in favor of one or of the other. (1127)

Art. 1197. If the obligation does not fix a period, but from its nature and the circumstances it can be inferred that a period was intended, the courts may fix the duration thereof.

The courts shall also fix the duration of the period when it depends upon the will of the debtor.

In every case, the courts shall determine such period as may under the circumstances have been probably contemplated by the parties. Once fixed by the courts, the period cannot be changed by them. (1128a)

Art. 1198. The debtor shall lose every right to make use of the period:

(1) When after the obligation has been contracted, he becomes insolvent, unless he gives a guaranty or security for the debt;

(2) When he does not furnish to the creditor the guaranties or securities which he has promised;

(3) When by his own acts he has impaired said guaranties or securities after their establishment, and when through a fortuitous event they disappear, unless he immediately gives new ones equally satisfactory;

(4) When the debtor violates any undertaking, in consideration of which the creditor agreed to the period;

(5) When the debtor attempts to abscond. (1129a)

The creditor cannot be compelled to receive part of one and part of the other undertaking. (1131)

Art. 1200. The right of choice belongs to the debtor, unless it has been expressly granted to the creditor.

The debtor shall have no right to choose those prestations which are impossible, unlawful or which could not have been the object of the obligation. (1132)

Art. 1201. The choice shall produce no effect except from the time it has been communicated. (1133)

Art. 1202. The debtor shall lose the right of choice when among the prestations whereby he is alternatively bound, only one is practicable. (1134)

Art. 1203. If through the creditor's acts the debtor cannot make a choice according to the terms of the obligation, the latter may rescind the contract with damages. (n)

Art. 1204. The creditor shall have a right to indemnity for damages when, through the fault of the debtor, all the things which are alternatively the object of the obligation have been lost, or the compliance of the obligation has become impossible.

The indemnity shall be fixed taking as a basis the value of the last thing which disappeared, or that of the service which last became impossible.

Damages other than the value of the last thing or service may also be awarded. (1135a)

Art. 1205. When the choice has been expressly given to the creditor, the obligation shall cease to be alternative from the day when the selection has been communicated to the debtor.

Until then the responsibility of the debtor shall be governed by the following rules:

(2) If the loss of one of the things occurs through the fault of the debtor, the creditor may claim any of those subsisting, or the price of that which, through the fault of the former, has disappeared, with a right to damages;

(3) If all the things are lost through the fault of the debtor, the choice by the creditor shall fall upon the price of any one of them, also with indemnity for damages.

Art. 1206. When only one prestation has been agreed upon, but the obligor may render another in substitution, the obligation is called facultative.

The loss or deterioration of the thing intended as a substitute, through the negligence of the obligor, does not render him liable. But once the substitution has been made, the obligor is liable for the loss of the substitute on account of his delay, negligence or fraud. (n)

Art. 1208. If from the law, or the nature or the wording of the obligations to which the preceding article refers the contrary does not appear, the credit or debt shall be presumed to be divided into as many shares as there are creditors or debtors, the credits or debts being considered distinct from one another, subject to the Rules of Court governing the multiplicity of suits. (1138a)

Art. 1209. If the division is impossible, the right of the creditors may be prejudiced only by their collective acts, and the debt can be enforced only by proceeding against all the debtors. If one of the latter should be insolvent, the others shall not be liable for his share. (1139)

Art. 1210. The indivisibility of an obligation does not necessarily give rise to solidarity. Nor does solidarity of itself imply indivisibility. (n)

Art. 1211. Solidarity may exist although the creditors and the debtors may not be bound in the same manner and by the same periods and conditions. (1140)

Art. 1212. Each one of the solidary creditors may do whatever may be useful to the others, but not anything which may be prejudicial to the latter. (1141a)

Art. 1213. A solidary creditor cannot assign his rights without the consent of the others. (n)

Art. 1214. The debtor may pay any one of the solidary creditors; but if any demand, judicial or extrajudicial, has been made by one of them, payment should be made to him. (1142a)

Art. 1215. Novation, compensation, confusion or remission of the debt, made by any of the solidary creditors or with any of the solidary debtors, shall extinguish the obligation, without prejudice to the provisions of Article 1219.

The creditor who may have executed any of these acts, as well as he who collects the debt, shall be liable to the others for the share in the obligation corresponding to them. (1143)

Art. 1216. The creditor may proceed against any one of the solidary debtors or some or all of them simultaneously. The demand made against one of them shall not be an obstacle to those which may subsequently be directed against the others, so long as the debt has not been fully collected. (1144a)

Art. 1217. Payment made by one of the solidary debtors extinguishes the obligation. If two or more solidary debtors offer to pay, the creditor may choose which offer to accept.

He who made the payment may claim from his co-debtors only the share which corresponds to each, with the interest for the payment already made. If the payment is made before the debt is due, no interest for the intervening period may be demanded.

When one of the solidary debtors cannot, because of his insolvency, reimburse his share to the debtor paying the obligation, such share shall be borne by all his co-debtors, in proportion to the debt of each. (1145a)

Art. 1218. Payment by a solidary debtor shall not entitle him to reimbursement from his co-debtors if such payment is made after the obligation has prescribed or become illegal. (n)

Art. 1219. The remission made by the creditor of the share which affects one of the solidary debtors does not release the latter from his responsibility towards the co-debtors, in case the debt had been totally paid by anyone of them before the remission was effected. (1146a)

Art. 1220. The remission of the whole obligation, obtained by one of the solidary debtors, does not entitle him to reimbursement from his co-debtors. (n)

Art. 1221. If the thing has been lost or if the prestation has become impossible without the fault of the solidary debtors, the obligation shall be extinguished.

If there was fault on the part of any one of them, all shall be responsible to the creditor, for the price and the payment of damages and interest, without prejudice to their action against the guilty or negligent debtor.

If through a fortuitous event, the thing is lost or the performance has become impossible after one of the solidary debtors has incurred in delay through the judicial or extrajudicial demand upon him by the creditor, the provisions of the preceding paragraph shall apply. (1147a)

Art. 1222. A solidary debtor may, in actions filed by the creditor, avail himself of all defenses which are derived from the nature of the obligation and of those which are personal to him, or pertain to his own share. With respect to those which personally belong to the others, he may avail himself thereof only as regards that part of the debt for which the latter are responsible. (1148a)

Art. 1224. A joint indivisible obligation gives rise to indemnity for damages from the time anyone of the debtors does not comply with his undertaking. The debtors who may have been ready to fulfill their promises shall not contribute to the indemnity beyond the corresponding portion of the price of the thing or of the value of the service in which the obligation consists. (1150)

Art. 1225. For the purposes of the preceding articles, obligations to give definite things and those which are not susceptible of partial performance shall be deemed to be indivisible.

When the obligation has for its object the execution of a certain number of days of work, the accomplishment of work by metrical units, or analogous things which by their nature are susceptible of partial performance, it shall be divisible.

However, even though the object or service may be physically divisible, an obligation is indivisible if so provided by law or intended by the parties.

In obligations not to do, divisibility or indivisibility shall be determined by the character of the prestation in each particular case. (1151a)

The penalty may be enforced only when it is demandable in accordance with the provisions of this Code. (1152a)

Art. 1227. The debtor cannot exempt himself from the performance of the obligation by paying the penalty, save in the case where this right has been expressly reserved for him. Neither can the creditor demand the fulfillment of the obligation and the satisfaction of the penalty at the same time, unless this right has been clearly granted him. However, if after the creditor has decided to require the fulfillment of the obligation, the performance thereof should become impossible without his fault, the penalty may be enforced. (1153a)

Art. 1228. Proof of actual damages suffered by the creditor is not necessary in order that the penalty may be demanded. (n)

Art. 1229. The judge shall equitably reduce the penalty when the principal obligation has been partly or irregularly complied with by the debtor. Even if there has been no performance, the penalty may also be reduced by the courts if it is iniquitous or unconscionable. (1154a)

Art. 1230. The nullity of the penal clause does not carry with it that of the principal obligation.

The nullity of the principal obligation carries with it that of the penal clause. (1155)

(2) By the loss of the thing due:

(3) By the condonation or remission of the debt;

(4) By the confusion or merger of the rights of creditor and debtor;

(5) By compensation;

(6) By novation.

Art. 1233. A debt shall not be understood to have been paid unless the thing or service in which the obligation consists has been completely delivered or rendered, as the case may be. (1157)

Art. 1234. If the obligation has been substantially performed in good faith, the obligor may recover as though there had been a strict and complete fulfillment, less damages suffered by the obligee. (n)

Art. 1235. When the obligee accepts the performance, knowing its incompleteness or irregularity, and without expressing any protest or objection, the obligation is deemed fully complied with. (n)

Art. 1236. The creditor is not bound to accept payment or performance by a third person who has no interest in the fulfillment of the obligation, unless there is a stipulation to the contrary.

Whoever pays for another may demand from the debtor what he has paid, except that if he paid without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, he can recover only insofar as the payment has been beneficial to the debtor. (1158a)

Art. 1237. Whoever pays on behalf of the debtor without the knowledge or against the will of the latter, cannot compel the creditor to subrogate him in his rights, such as those arising from a mortgage, guaranty, or penalty. (1159a)

Art. 1238. Payment made by a third person who does not intend to be reimbursed by the debtor is deemed to be a donation, which requires the debtor's consent. But the payment is in any case valid as to the creditor who has accepted it. (n)

Art. 1239. In obligations to give, payment made by one who does not have the free disposal of the thing due and capacity to alienate it shall not be valid, without prejudice to the provisions of Article 1427 under the Title on " Natural Obligations ." (1160a)

Art. 1240. Payment shall be made to the person in whose favor the obligation has been constituted, or his successor in interest, or any person authorized to receive it. (1162a)

Art. 1241. Payment to a person who is incapacitated to administer his property shall be valid if he has kept the thing delivered, or insofar as the payment has been beneficial to him.

Payment made to a third person shall also be valid insofar as it has redounded to the benefit of the creditor. Such benefit to the creditor need not be proved in the following cases:

(2) If the creditor ratifies the payment to the third person;

(3) If by the creditor's conduct, the debtor has been led to believe that the third person had authority to receive the payment. (1163a)

Art. 1242. Payment made in good faith to any person in possession of the credit shall release the debtor. (1164)

Art. 1244. The debtor of a thing cannot compel the creditor to receive a different one, although the latter may be of the same value as, or more valuable than that which is due.

In obligations to do or not to do, an act or forbearance cannot be substituted by another act or forbearance against the obligee's will. (1166a)

Art. 1245. Dation in payment, whereby property is alienated to the creditor in satisfaction of a debt in money, shall be governed by the law of sales. (n)

Art. 1246. When the obligation consists in the delivery of an indeterminate or generic thing, whose quality and circumstances have not been stated, the creditor cannot demand a thing of superior quality. Neither can the debtor deliver a thing of inferior quality. The purpose of the obligation and other circumstances shall be taken into consideration. (1167a)

Art. 1247. Unless it is otherwise stipulated, the extrajudicial expenses required by the payment shall be for the account of the debtor. With regard to judicial costs, the Rules of Court shall govern. (1168a)

Art. 1248. Unless there is an express stipulation to that effect, the creditor cannot be compelled partially to receive the prestations in which the obligation consists. Neither may the debtor be required to make partial payments.

However, when the debt is in part liquidated and in part unliquidated, the creditor may demand and the debtor may effect the payment of the former without waiting for the liquidation of the latter. (1169a)

Art. 1249. The payment of debts in money shall be made in the currency stipulated, and if it is not possible to deliver such currency, then in the currency which is legal tender in the Philippines.

The delivery of promissory notes payable to order, or bills of exchange or other mercantile documents shall produce the effect of payment only when they have been cashed, or when through the fault of the creditor they have been impaired.

In the meantime, the action derived from the original obligation shall be held in the abeyance. (1170)

Art. 1250. In case an extraordinary inflation or deflation of the currency stipulated should supervene, the value of the currency at the time of the establishment of the obligation shall be the basis of payment, unless there is an agreement to the contrary. (n)

Art. 1251. Payment shall be made in the place designated in the obligation.

There being no express stipulation and if the undertaking is to deliver a determinate thing, the payment shall be made wherever the thing might be at the moment the obligation was constituted.

In any other case the place of payment shall be the domicile of the debtor.

If the debtor changes his domicile in bad faith or after he has incurred in delay, the additional expenses shall be borne by him.

These provisions are without prejudice to venue under the Rules of Court. (1171a)

If the debtor accepts from the creditor a receipt in which an application of the payment is made, the former cannot complain of the same, unless there is a cause for invalidating the contract. (1172a)

Art. 1253. If the debt produces interest, payment of the principal shall not be deemed to have been made until the interests have been covered. (1173)

Art. 1254. When the payment cannot be applied in accordance with the preceding rules, or if application can not be inferred from other circumstances, the debt which is most onerous to the debtor, among those due, shall be deemed to have been satisfied.

If the debts due are of the same nature and burden, the payment shall be applied to all of them proportionately. (1174a)

Consignation alone shall produce the same effect in the following cases:

(2) When he is incapacitated to receive the payment at the time it is due;

(3) When, without just cause, he refuses to give a receipt;

(4) When two or more persons claim the same right to collect;

(5) When the title of the obligation has been lost. (1176a)

The consignation shall be ineffectual if it is not made strictly in consonance with the provisions which regulate payment. (1177)

Art. 1258. Consignation shall be made by depositing the things due at the disposal of judicial authority, before whom the tender of payment shall be proved, in a proper case, and the announcement of the consignation in other cases.

The consignation having been made, the interested parties shall also be notified thereof. (1178)

Art. 1259. The expenses of consignation, when properly made, shall be charged against the creditor. (1178)

Art. 1260. Once the consignation has been duly made, the debtor may ask the judge to order the cancellation of the obligation.

Before the creditor has accepted the consignation, or before a judicial declaration that the consignation has been properly made, the debtor may withdraw the thing or the sum deposited, allowing the obligation to remain in force. (1180)

Art. 1261. If, the consignation having been made, the creditor should authorize the debtor to withdraw the same, he shall lose every preference which he may have over the thing. The co-debtors, guarantors and sureties shall be released. (1181a)

When by law or stipulation, the obligor is liable even for fortuitous events, the loss of the thing does not extinguish the obligation, and he shall be responsible for damages. The same rule applies when the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk. (1182a)

Art. 1263. In an obligation to deliver a generic thing, the loss or destruction of anything of the same kind does not extinguish the obligation. (n)

Art. 1264. The courts shall determine whether, under the circumstances, the partial loss of the object of the obligation is so important as to extinguish the obligation. (n)

Art. 1265. Whenever the thing is lost in the possession of the debtor, it shall be presumed that the loss was due to his fault, unless there is proof to the contrary, and without prejudice to the provisions of article 1165. This presumption does not apply in case of earthquake, flood, storm, or other natural calamity. (1183a)

Art. 1266. The debtor in obligations to do shall also be released when the prestation becomes legally or physically impossible without the fault of the obligor. (1184a)

Art. 1267. When the service has become so difficult as to be manifestly beyond the contemplation of the parties, the obligor may also be released therefrom, in whole or in part. (n)

Art. 1268. When the debt of a thing certain and determinate proceeds from a criminal offense, the debtor shall not be exempted from the payment of its price, whatever may be the cause for the loss, unless the thing having been offered by him to the person who should receive it, the latter refused without justification to accept it. (1185)

Art. 1269. The obligation having been extinguished by the loss of the thing, the creditor shall have all the rights of action which the debtor may have against third persons by reason of the loss. (1186)

One and the other kind shall be subject to the rules which govern inofficious donations. Express condonation shall, furthermore, comply with the forms of donation. (1187)

Art. 1271. The delivery of a private document evidencing a credit, made voluntarily by the creditor to the debtor, implies the renunciation of the action which the former had against the latter.

If in order to nullify this waiver it should be claimed to be inofficious, the debtor and his heirs may uphold it by proving that the delivery of the document was made in virtue of payment of the debt. (1188)

Art. 1272. Whenever the private document in which the debt appears is found in the possession of the debtor, it shall be presumed that the creditor delivered it voluntarily, unless the contrary is proved. (1189)

Art. 1273. The renunciation of the principal debt shall extinguish the accessory obligations; but the waiver of the latter shall leave the former in force. (1190)

Art. 1274. It is presumed that the accessory obligation of pledge has been remitted when the thing pledged, after its delivery to the creditor, is found in the possession of the debtor, or of a third person who owns the thing. (1191a)

Art. 1276. Merger which takes place in the person of the principal debtor or creditor benefits the guarantors. Confusion which takes place in the person of any of the latter does not extinguish the obligation. (1193)

Art. 1277. Confusion does not extinguish a joint obligation except as regards the share corresponding to the creditor or debtor in whom the two characters concur. (1194)

Art. 1279. In order that compensation may be proper, it is necessary:

(2) That both debts consist in a sum of money, or if the things due are consumable, they be of the same kind, and also of the same quality if the latter has been stated;

(3) That the two debts be due;

(4) That they be liquidated and demandable;

(5) That over neither of them there be any retention or controversy, commenced by third persons and communicated in due time to the debtor. (1196)

Art. 1281. Compensation may be total or partial. When the two debts are of the same amount, there is a total compensation. (n)

Art. 1282. The parties may agree upon the compensation of debts which are not yet due. (n)

Art. 1283. If one of the parties to a suit over an obligation has a claim for damages against the other, the former may set it off by proving his right to said damages and the amount thereof. (n)

Art. 1284. When one or both debts are rescissible or voidable, they may be compensated against each other before they are judicially rescinded or avoided. (n)

Art. 1285. The debtor who has consented to the assignment of rights made by a creditor in favor of a third person, cannot set up against the assignee the compensation which would pertain to him against the assignor, unless the assignor was notified by the debtor at the time he gave his consent, that he reserved his right to the compensation.

If the creditor communicated the cession to him but the debtor did not consent thereto, the latter may set up the compensation of debts previous to the cession, but not of subsequent ones.

If the assignment is made without the knowledge of the debtor, he may set up the compensation of all credits prior to the same and also later ones until he had knowledge of the assignment. (1198a)

Art. 1286. Compensation takes place by operation of law, even though the debts may be payable at different places, but there shall be an indemnity for expenses of exchange or transportation to the place of payment. (1199a)

Art. 1287. Compensation shall not be proper when one of the debts arises from a depositum or from the obligations of a depositary or of a bailee in commodatum.

Neither can compensation be set up against a creditor who has a claim for support due by gratuitous title, without prejudice to the provisions of paragraph 2 of Article 301. (1200a)

Art. 1288. Neither shall there be compensation if one of the debts consists in civil liability arising from a penal offense. (n)

Art. 1289. If a person should have against him several debts which are susceptible of compensation, the rules on the application of payments shall apply to the order of the compensation. (1201)

Art. 1290. When all the requisites mentioned in Article 1279 are present, compensation takes effect by operation of law, and extinguishes both debts to the concurrent amount, even though the creditors and debtors are not aware of the compensation. (1202a)

(2) Substituting the person of the debtor;

(3) Subrogating a third person in the rights of the creditor. (1203)

Art. 1293. Novation which consists in substituting a new debtor in the place of the original one, may be made even without the knowledge or against the will of the latter, but not without the consent of the creditor. Payment by the new debtor gives him the rights mentioned in Articles 1236 and 1237. (1205a)

Art. 1294. If the substitution is without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, the new debtor's insolvency or non-fulfillment of the obligations shall not give rise to any liability on the part of the original debtor. (n)

Art. 1295. The insolvency of the new debtor, who has been proposed by the original debtor and accepted by the creditor, shall not revive the action of the latter against the original obligor, except when said insolvency was already existing and of public knowledge, or known to the debtor, when the delegated his debt. (1206a)

Art. 1296. When the principal obligation is extinguished in consequence of a novation, accessory obligations may subsist only insofar as they may benefit third persons who did not give their consent. (1207)

Art. 1297. If the new obligation is void, the original one shall subsist, unless the parties intended that the former relation should be extinguished in any event. (n)

Art. 1298. The novation is void if the original obligation was void, except when annulment may be claimed only by the debtor or when ratification validates acts which are voidable. (1208a)

Art. 1299. If the original obligation was subject to a suspensive or resolutory condition, the new obligation shall be under the same condition, unless it is otherwise stipulated. (n)

Art. 1300. Subrogation of a third person in the rights of the creditor is either legal or conventional. The former is not presumed, except in cases expressly mentioned in this Code; the latter must be clearly established in order that it may take effect. (1209a)

Art. 1301. Conventional subrogation of a third person requires the consent of the original parties and of the third person. (n)

Art. 1302. It is presumed that there is legal subrogation:

(2) When a third person, not interested in the obligation, pays with the express or tacit approval of the debtor;

(3) When, even without the knowledge of the debtor, a person interested in the fulfillment of the obligation pays, without prejudice to the effects of confusion as to the latter's share. (1210a)

Art. 1304. A creditor, to whom partial payment has been made, may exercise his right for the remainder, and he shall be preferred to the person who has been subrogated in his place in virtue of the partial payment of the same credit. (1213)

Art. 1306. The contracting parties may establish such stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions as they may deem convenient, provided they are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy. (1255a)

Art. 1307. Innominate contracts shall be regulated by the stipulations of the parties, by the provisions of Titles I and II of this Book, by the rules governing the most analogous nominate contracts, and by the customs of the place. (n)

Art. 1308. The contract must bind both contracting parties; its validity or compliance cannot be left to the will of one of them. (1256a)

Art. 1309. The determination of the performance may be left to a third person, whose decision shall not be binding until it has been made known to both contracting parties. (n)

Art. 1310. The determination shall not be obligatory if it is evidently inequitable. In such case, the courts shall decide what is equitable under the circumstances. (n)

Art. 1311. Contracts take effect only between the parties, their assigns and heirs, except in case where the rights and obligations arising from the contract are not transmissible by their nature, or by stipulation or by provision of law. The heir is not liable beyond the value of the property he received from the decedent.

If a contract should contain some stipulation in favor of a third person, he may demand its fulfillment provided he communicated his acceptance to the obligor before its revocation. A mere incidental benefit or interest of a person is not sufficient. The contracting parties must have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon a third person. (1257a)

Art. 1312. In contracts creating real rights, third persons who come into possession of the object of the contract are bound thereby, subject to the provisions of the Mortgage Law and the Land Registration Laws. (n)

Art. 1313. Creditors are protected in cases of contracts intended to defraud them. (n)

Art. 1314. Any third person who induces another to violate his contract shall be liable for damages to the other contracting party. (n)

Art. 1315. Contracts are perfected by mere consent, and from that moment the parties are bound not only to the fulfillment of what has been expressly stipulated but also to all the consequences which, according to their nature, may be in keeping with good faith, usage and law. (1258)

Art. 1316. Real contracts, such as deposit, pledge and Commodatum, are not perfected until the delivery of the object of the obligation. (n)

Art. 1317. No one may contract in the name of another without being authorized by the latter, or unless he has by law a right to represent him.

A contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers, shall be unenforceable, unless it is ratified, expressly or impliedly, by the person on whose behalf it has been executed, before it is revoked by the other contracting party. (1259a)

(2) Object certain which is the subject matter of the contract;

(3) Cause of the obligation which is established. (1261)

Acceptance made by letter or telegram does not bind the offerer except from the time it came to his knowledge. The contract, in such a case, is presumed to have been entered into in the place where the offer was made. (1262a)

Art. 1320. An acceptance may be express or implied. (n)

Art. 1321. The person making the offer may fix the time, place, and manner of acceptance, all of which must be complied with. (n)

Art. 1322. An offer made through an agent is accepted from the time acceptance is communicated to him. (n)

Art. 1323. An offer becomes ineffective upon the death, civil interdiction, insanity, or insolvency of either party before acceptance is conveyed. (n)

Art. 1324. When the offerer has allowed the offeree a certain period to accept, the offer may be withdrawn at any time before acceptance by communicating such withdrawal, except when the option is founded upon a consideration, as something paid or promised. (n)

Art. 1325. Unless it appears otherwise, business advertisements of things for sale are not definite offers, but mere invitations to make an offer. (n)

Art. 1326. Advertisements for bidders are simply invitations to make proposals, and the advertiser is not bound to accept the highest or lowest bidder, unless the contrary appears. (n)

Art. 1327. The following cannot give consent to a contract:

(2) Insane or demented persons, and deaf-mutes who do not know how to write. (1263a)

Art. 1329. The incapacity declared in Article 1327 is subject to the modifications determined by law, and is understood to be without prejudice to special disqualifications established in the laws. (1264)

Art. 1330. A contract where consent is given through mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud is voidable. (1265a)

Art. 1331. In order that mistake may invalidate consent, it should refer to the substance of the thing which is the object of the contract, or to those conditions which have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract.

Mistake as to the identity or qualifications of one of the parties will vitiate consent only when such identity or qualifications have been the principal cause of the contract.

A simple mistake of account shall give rise to its correction. (1266a)

Art. 1332. When one of the parties is unable to read, or if the contract is in a language not understood by him, and mistake or fraud is alleged, the person enforcing the contract must show that the terms thereof have been fully explained to the former. (n)

Art. 1333. There is no mistake if the party alleging it knew the doubt, contingency or risk affecting the object of the contract. (n)

Art. 1334. Mutual error as to the legal effect of an agreement when the real purpose of the parties is frustrated, may vitiate consent. (n)

Art. 1335. There is violence when in order to wrest consent, serious or irresistible force is employed.

There is intimidation when one of the contracting parties is compelled by a reasonable and well-grounded fear of an imminent and grave evil upon his person or property, or upon the person or property of his spouse, descendants or ascendants, to give his consent.

To determine the degree of intimidation, the age, sex and condition of the person shall be borne in mind.

A threat to enforce one's claim through competent authority, if the claim is just or legal, does not vitiate consent. (1267a)

Art. 1336. Violence or intimidation shall annul the obligation, although it may have been employed by a third person who did not take part in the contract. (1268)

Art. 1337. There is undue influence when a person takes improper advantage of his power over the will of another, depriving the latter of a reasonable freedom of choice. The following circumstances shall be considered: the confidential, family, spiritual and other relations between the parties, or the fact that the person alleged to have been unduly influenced was suffering from mental weakness, or was ignorant or in financial distress. (n)

Art. 1338. There is fraud when, through insidious words or machinations of one of the contracting parties, the other is induced to enter into a contract which, without them, he would not have agreed to. (1269)

Art. 1339. Failure to disclose facts, when there is a duty to reveal them, as when the parties are bound by confidential relations, constitutes fraud. (n)

Art. 1340. The usual exaggerations in trade, when the other party had an opportunity to know the facts, are not in themselves fraudulent. (n)

Art. 1341. A mere expression of an opinion does not signify fraud, unless made by an expert and the other party has relied on the former's special knowledge. (n)

Art. 1342. Misrepresentation by a third person does not vitiate consent, unless such misrepresentation has created substantial mistake and the same is mutual. (n)

Art. 1343. Misrepresentation made in good faith is not fraudulent but may constitute error. (n)

Art. 1344. In order that fraud may make a contract voidable, it should be serious and should not have been employed by both contracting parties.

Incidental fraud only obliges the person employing it to pay damages. (1270)

Art. 1345. Simulation of a contract may be absolute or relative. The former takes place when the parties do not intend to be bound at all; the latter, when the parties conceal their true agreement. (n)

Art. 1346. An absolutely simulated or fictitious contract is void. A relative simulation, when it does not prejudice a third person and is not intended for any purpose contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy binds the parties to their real agreement. (n)

No contract may be entered into upon future inheritance except in cases expressly authorized by law.

All services which are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy may likewise be the object of a contract. (1271a)

Art. 1348. Impossible things or services cannot be the object of contracts. (1272)

Art. 1349. The object of every contract must be determinate as to its kind. The fact that the quantity is not determinate shall not be an obstacle to the existence of the contract, provided it is possible to determine the same, without the need of a new contract between the parties. (1273)

Art. 1351. The particular motives of the parties in entering into a contract are different from the cause thereof. (n)

Art. 1352. Contracts without cause, or with unlawful cause, produce no effect whatever. The cause is unlawful if it is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. (1275a)

Art. 1353. The statement of a false cause in contracts shall render them void, if it should not be proved that they were founded upon another cause which is true and lawful. (1276)

Art. 1354. Although the cause is not stated in the contract, it is presumed that it exists and is lawful, unless the debtor proves the contrary. (1277)

Art. 1355. Except in cases specified by law, lesion or inadequacy of cause shall not invalidate a contract, unless there has been fraud, mistake or undue influence. (n)

Art. 1357. If the law requires a document or other special form, as in the acts and contracts enumerated in the following article, the contracting parties may compel each other to observe that form, once the contract has been perfected. This right may be exercised simultaneously with the action upon the contract. (1279a)

Art. 1358. The following must appear in a public document:

(2) The cession, repudiation or renunciation of hereditary rights or of those of the conjugal partnership of gains;

(3) The power to administer property, or any other power which has for its object an act appearing or which should appear in a public document, or should prejudice a third person;

(4) The cession of actions or rights proceeding from an act appearing in a public document.

If mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct, or accident has prevented a meeting of the minds of the parties, the proper remedy is not reformation of the instrument but annulment of the contract.

Art. 1360. The principles of the general law on the reformation of instruments are hereby adopted insofar as they are not in conflict with the provisions of this Code.

Art. 1361. When a mutual mistake of the parties causes the failure of the instrument to disclose their real agreement, said instrument may be reformed.

Art. 1362. If one party was mistaken and the other acted fraudulently or inequitably in such a way that the instrument does not show their true intention, the former may ask for the reformation of the instrument.

Art. 1363. When one party was mistaken and the other knew or believed that the instrument did not state their real agreement, but concealed that fact from the former, the instrument may be reformed.

Art. 1364. When through the ignorance, lack of skill, negligence or bad faith on the part of the person drafting the instrument or of the clerk or typist, the instrument does not express the true intention of the parties, the courts may order that the instrument be reformed.

Art. 1365. If two parties agree upon the mortgage or pledge of real or personal property, but the instrument states that the property is sold absolutely or with a right of repurchase, reformation of the instrument is proper.

Art. 1366. There shall be no reformation in the following cases:

(3) When the real agreement is void.

Art. 1368. Reformation may be ordered at the instance of either party or his successors in interest, if the mistake was mutual; otherwise, upon petition of the injured party, or his heirs and assigns.

Art. 1369. The procedure for the reformation of instrument shall be governed by rules of court to be promulgated by the Supreme Court.

If the words appear to be contrary to the evident intention of the parties, the latter shall prevail over the former. (1281)

Art. 1371. In order to judge the intention of the contracting parties, their contemporaneous and subsequent acts shall be principally considered. (1282)

Art. 1372. However general the terms of a contract may be, they shall not be understood to comprehend things that are distinct and cases that are different from those upon which the parties intended to agree. (1283)

Art. 1373. If some stipulation of any contract should admit of several meanings, it shall be understood as bearing that import which is most adequate to render it effectual. (1284)

Art. 1374. The various stipulations of a contract shall be interpreted together, attributing to the doubtful ones that sense which may result from all of them taken jointly. (1285)

Art. 1375. Words which may have different significations shall be understood in that which is most in keeping with the nature and object of the contract. (1286)

Art. 1376. The usage or custom of the place shall be borne in mind in the interpretation of the ambiguities of a contract, and shall fill the omission of stipulations which are ordinarily established. (1287)

Art. 1377. The interpretation of obscure words or stipulations in a contract shall not favor the party who caused the obscurity. (1288)

Art. 1378. When it is absolutely impossible to settle doubts by the rules established in the preceding articles, and the doubts refer to incidental circumstances of a gratuitous contract, the least transmission of rights and interests shall prevail. If the contract is onerous, the doubt shall be settled in favor of the greatest reciprocity of interests.

If the doubts are cast upon the principal object of the contract in such a way that it cannot be known what may have been the intention or will of the parties, the contract shall be null and void. (1289)

Art. 1379. The principles of interpretation stated in Rule 123 of the Rules of Court shall likewise be observed in the construction of contracts. (n)

Art. 1381. The following contracts are rescissible:

(2) Those agreed upon in representation of absentees, if the latter suffer the lesion stated in the preceding number;

(3) Those undertaken in fraud of creditors when the latter cannot in any other manner collect the claims due them;

(4) Those which refer to things under litigation if they have been entered into by the defendant without the knowledge and approval of the litigants or of competent judicial authority;

(5) All other contracts specially declared by law to be subject to rescission. (1291a)

Art. 1383. The action for rescission is subsidiary; it cannot be instituted except when the party suffering damage has no other legal means to obtain reparation for the same. (1294)

Art. 1384. Rescission shall be only to the extent necessary to cover the damages caused. (n)

Art. 1385. Rescission creates the obligation to return the things which were the object of the contract, together with their fruits, and the price with its interest; consequently, it can be carried out only when he who demands rescission can return whatever he may be obliged to restore.

Neither shall rescission take place when the things which are the object of the contract are legally in the possession of third persons who did not act in bad faith.

In this case, indemnity for damages may be demanded from the person causing the loss. (1295)

Art. 1386. Rescission referred to in Nos. 1 and 2 of Article 1381 shall not take place with respect to contracts approved by the courts. (1296a)

Art. 1387. All contracts by virtue of which the debtor alienates property by gratuitous title are presumed to have been entered into in fraud of creditors, when the donor did not reserve sufficient property to pay all debts contracted before the donation.

Alienations by onerous title are also presumed fraudulent when made by persons against whom some judgment has been issued. The decision or attachment need not refer to the property alienated, and need not have been obtained by the party seeking the rescission.

In addition to these presumptions, the design to defraud creditors may be proved in any other manner recognized by the law of evidence. (1297a)

Art. 1388. Whoever acquires in bad faith the things alienated in fraud of creditors, shall indemnify the latter for damages suffered by them on account of the alienation, whenever, due to any cause, it should be impossible for him to return them.

If there are two or more alienations, the first acquirer shall be liable first, and so on successively. (1298a)

Art. 1389. The action to claim rescission must be commenced within four years.

For persons under guardianship and for absentees, the period of four years shall not begin until the termination of the former's incapacity, or until the domicile of the latter is known. (1299)

(2) Those where the consent is vitiated by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud.

Art. 1391. The action for annulment shall be brought within four years.

This period shall begin:

In case of mistake or fraud, from the time of the discovery of the same.

Art. 1392. Ratification extinguishes the action to annul a voidable contract. (1309a)

Art. 1393. Ratification may be effected expressly or tacitly. It is understood that there is a tacit ratification if, with knowledge of the reason which renders the contract voidable and such reason having ceased, the person who has a right to invoke it should execute an act which necessarily implies an intention to waive his right. (1311a)

Art. 1394. Ratification may be effected by the guardian of the incapacitated person. (n)

Art. 1395. Ratification does not require the conformity of the contracting party who has no right to bring the action for annulment. (1312)

Art. 1396. Ratification cleanses the contract from all its defects from the moment it was constituted. (1313)

Art. 1397. The action for the annulment of contracts may be instituted by all who are thereby obliged principally or subsidiarily. However, persons who are capable cannot allege the incapacity of those with whom they contracted; nor can those who exerted intimidation, violence, or undue influence, or employed fraud, or caused mistake base their action upon these flaws of the contract. (1302a)

Art. 1398. An obligation having been annulled, the contracting parties shall restore to each other the things which have been the subject matter of the contract, with their fruits, and the price with its interest, except in cases provided by law.

In obligations to render service, the value thereof shall be the basis for damages. (1303a)

Art. 1399. When the defect of the contract consists in the incapacity of one of the parties, the incapacitated person is not obliged to make any restitution except insofar as he has been benefited by the thing or price received by him. (1304)

Art. 1400. Whenever the person obliged by the decree of annulment to return the thing can not do so because it has been lost through his fault, he shall return the fruits received and the value of the thing at the time of the loss, with interest from the same date. (1307a)

Art. 1401. The action for annulment of contracts shall be extinguished when the thing which is the object thereof is lost through the fraud or fault of the person who has a right to institute the proceedings.

If the right of action is based upon the incapacity of any one of the contracting parties, the loss of the thing shall not be an obstacle to the success of the action, unless said loss took place through the fraud or fault of the plaintiff. (1314a)

Art. 1402. As long as one of the contracting parties does not restore what in virtue of the decree of annulment he is bound to return, the other cannot be compelled to comply with what is incumbent upon him. (1308)

(2) Those that do not comply with the Statute of Frauds as set forth in this number. In the following cases an agreement hereafter made shall be unenforceable by action, unless the same, or some note or memorandum, thereof, be in writing, and subscribed by the party charged, or by his agent; evidence, therefore, of the agreement cannot be received without the writing, or a secondary evidence of its contents:

(b) A special promise to answer for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another;

(c) An agreement made in consideration of marriage, other than a mutual promise to marry;

(d) An agreement for the sale of goods, chattels or things in action, at a price not less than five hundred pesos, unless the buyer accept and receive part of such goods and chattels, or the evidences, or some of them, of such things in action or pay at the time some part of the purchase money; but when a sale is made by auction and entry is made by the auctioneer in his sales book, at the time of the sale, of the amount and kind of property sold, terms of sale, price, names of the purchasers and person on whose account the sale is made, it is a sufficient memorandum;

(e) An agreement of the leasing for a longer period than one year, or for the sale of real property or of an interest therein;

(f) A representation as to the credit of a third person.

(3) Those where both parties are incapable of giving consent to a contract.

Art. 1405. Contracts infringing the Statute of Frauds, referred to in No. 2 of Article 1403, are ratified by the failure to object to the presentation of oral evidence to prove the same, or by the acceptance of benefit under them.

Art. 1406. When a contract is enforceable under the Statute of Frauds, and a public document is necessary for its registration in the Registry of Deeds, the parties may avail themselves of the right under Article 1357.

Art. 1407. In a contract where both parties are incapable of giving consent, express or implied ratification by the parent, or guardian, as the case may be, of one of the contracting parties shall give the contract the same effect as if only one of them were incapacitated.

If ratification is made by the parents or guardians, as the case may be, of both contracting parties, the contract shall be validated from the inception.

Art. 1408. Unenforceable contracts cannot be assailed by third persons.

(2) Those which are absolutely simulated or fictitious;

(3) Those whose cause or object did not exist at the time of the transaction;

(4) Those whose object is outside the commerce of men;

(5) Those which contemplate an impossible service;

(6) Those where the intention of the parties relative to the principal object of the contract cannot be ascertained;

(7) Those expressly prohibited or declared void by law.

Art. 1410. The action or defense for the declaration of the inexistence of a contract does not prescribe.

Art. 1411. When the nullity proceeds from the illegality of the cause or object of the contract, and the act constitutes a criminal offense, both parties being in pari delicto, they shall have no action against each other, and both shall be prosecuted. Moreover, the provisions of the Penal Code relative to the disposal of effects or instruments of a crime shall be applicable to the things or the price of the contract.

This rule shall be applicable when only one of the parties is guilty; but the innocent one may claim what he has given, and shall not be bound to comply with his promise. (1305)

Art. 1412. If the act in which the unlawful or forbidden cause consists does not constitute a criminal offense, the following rules shall be observed:

(2) When only one of the contracting parties is at fault, he cannot recover what he has given by reason of the contract, or ask for the fulfillment of what has been promised him. The other, who is not at fault, may demand the return of what he has given without any obligation to comply his promise. (1306)

Art. 1414. When money is paid or property delivered for an illegal purpose, the contract may be repudiated by one of the parties before the purpose has been accomplished, or before any damage has been caused to a third person. In such case, the courts may, if the public interest will thus be subserved, allow the party repudiating the contract to recover the money or property.

Art. 1415. Where one of the parties to an illegal contract is incapable of giving consent, the courts may, if the interest of justice so demands allow recovery of money or property delivered by the incapacitated person.

Art. 1416. When the agreement is not illegal per se but is merely prohibited, and the prohibition by the law is designated for the protection of the plaintiff, he may, if public policy is thereby enhanced, recover what he has paid or delivered.

Art. 1417. When the price of any article or commodity is determined by statute, or by authority of law, any person paying any amount in excess of the maximum price allowed may recover such excess.

Art. 1418. When the law fixes, or authorizes the fixing of the maximum number of hours of labor, and a contract is entered into whereby a laborer undertakes to work longer than the maximum thus fixed, he may demand additional compensation for service rendered beyond the time limit.

Art. 1419. When the law sets, or authorizes the setting of a minimum wage for laborers, and a contract is agreed upon by which a laborer accepts a lower wage, he shall be entitled to recover the deficiency.

Art. 1420. In case of a divisible contract, if the illegal terms can be separated from the legal ones, the latter may be enforced.

Art. 1421. The defense of illegality of contract is not available to third persons whose interests are not directly affected.

Art. 1422. A contract which is the direct result of a previous illegal contract, is also void and inexistent.

Art. 1424. When a right to sue upon a civil obligation has lapsed by extinctive prescription, the obligor who voluntarily performs the contract cannot recover what he has delivered or the value of the service he has rendered.

Art. 1425. When without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, a third person pays a debt which the obligor is not legally bound to pay because the action thereon has prescribed, but the debtor later voluntarily reimburses the third person, the obligor cannot recover what he has paid.

Art. 1426. When a minor between eighteen and twenty-one years of age who has entered into a contract without the consent of the parent or guardian, after the annulment of the contract voluntarily returns the whole thing or price received, notwithstanding the fact the he has not been benefited thereby, there is no right to demand the thing or price thus returned.

Art. 1427. When a minor between eighteen and twenty-one years of age, who has entered into a contract without the consent of the parent or guardian, voluntarily pays a sum of money or delivers a fungible thing in fulfillment of the obligation, there shall be no right to recover the same from the obligee who has spent or consumed it in good faith. (1160A)

Art. 1428. When, after an action to enforce a civil obligation has failed the defendant voluntarily performs the obligation, he cannot demand the return of what he has delivered or the payment of the value of the service he has rendered.

Art. 1429. When a testate or intestate heir voluntarily pays a debt of the decedent exceeding the value of the property which he received by will or by the law of intestacy from the estate of the deceased, the payment is valid and cannot be rescinded by the payer.

Art. 1430. When a will is declared void because it has not been executed in accordance with the formalities required by law, but one of the intestate heirs, after the settlement of the debts of the deceased, pays a legacy in compliance with a clause in the defective will, the payment is effective and irrevocable.

Art. 1432. The principles of estoppel are hereby adopted insofar as they are not in conflict with the provisions of this Code, the Code of Commerce, the Rules of Court and special laws.

Art. 1433. Estoppel may be in pais or by deed.

Art. 1434. When a person who is not the owner of a thing sells or alienates and delivers it, and later the seller or grantor acquires title thereto, such title passes by operation of law to the buyer or grantee.

Art. 1435. If a person in representation of another sells or alienates a thing, the former cannot subsequently set up his own title as against the buyer or grantee.

Art. 1436. A lessee or a bailee is estopped from asserting title to the thing leased or received, as against the lessor or bailor.

Art. 1437. When in a contract between third persons concerning immovable property, one of them is misled by a person with respect to the ownership or real right over the real estate, the latter is precluded from asserting his legal title or interest therein, provided all these requisites are present:

(2) The party precluded must intend that the other should act upon the facts as misrepresented;

(3) The party misled must have been unaware of the true facts; and

(4) The party defrauded must have acted in accordance with the misrepresentation.

Art. 1439. Estoppel is effective only as between the parties thereto or their successors in interest.

Art. 1441. Trusts are either express or implied. Express trusts are created by the intention of the trustor or of the parties. Implied trusts come into being by operation of law.

Art. 1442. The principles of the general law of trusts, insofar as they are not in conflict with this Code, the Code of Commerce, the Rules of Court and special laws are hereby adopted.

Art. 1444. No particular words are required for the creation of an express trust, it being sufficient that a trust is clearly intended.

Art. 1445. No trust shall fail because the trustee appointed declines the designation, unless the contrary should appear in the instrument constituting the trust.

Art. 1446. Acceptance by the beneficiary is necessary. Nevertheless, if the trust imposes no onerous condition upon the beneficiary, his acceptance shall be presumed, if there is no proof to the contrary.

Art. 1448. There is an implied trust when property is sold, and the legal estate is granted to one party but the price is paid by another for the purpose of having the beneficial interest of the property. The former is the trustee, while the latter is the beneficiary. However, if the person to whom the title is conveyed is a child, legitimate or illegitimate, of the one paying the price of the sale, no trust is implied by law, it being disputably presumed that there is a gift in favor of the child.

Art. 1449. There is also an implied trust when a donation is made to a person but it appears that although the legal estate is transmitted to the donee, he nevertheless is either to have no beneficial interest or only a part thereof.

Art. 1450. If the price of a sale of property is loaned or paid by one person for the benefit of another and the conveyance is made to the lender or payor to secure the payment of the debt, a trust arises by operation of law in favor of the person to whom the money is loaned or for whom its is paid. The latter may redeem the property and compel a conveyance thereof to him.

Art. 1451. When land passes by succession to any person and he causes the legal title to be put in the name of another, a trust is established by implication of law for the benefit of the true owner.

Art. 1452. If two or more persons agree to purchase property and by common consent the legal title is taken in the name of one of them for the benefit of all, a trust is created by force of law in favor of the others in proportion to the interest of each.

Art. 1453. When property is conveyed to a person in reliance upon his declared intention to hold it for, or transfer it to another or the grantor, there is an implied trust in favor of the person whose benefit is contemplated.

Art. 1454. If an absolute conveyance of property is made in order to secure the performance of an obligation of the grantor toward the grantee, a trust by virtue of law is established. If the fulfillment of the obligation is offered by the grantor when it becomes due, he may demand the reconveyance of the property to him.

Art. 1455. When any trustee, guardian or other person holding a fiduciary relationship uses trust funds for the purchase of property and causes the conveyance to be made to him or to a third person, a trust is established by operation of law in favor of the person to whom the funds belong.

Art. 1456. If property is acquired through mistake or fraud, the person obtaining it is, by force of law, considered a trustee of an implied trust for the benefit of the person from whom the property comes.

Art. 1457. An implied trust may be proved by oral evidence.

A contract of sale may be absolute or conditional. (1445a)

Art. 1459. The thing must be licit and the vendor must have a right to transfer the ownership thereof at the time it is delivered. (n)

Art. 1460. A thing is determinate when it is particularly designated or physical segregated from all other of the same class.

The requisite that a thing be determinate is satisfied if at the time the contract is entered into, the thing is capable of being made determinate without the necessity of a new or further agreement between the parties. (n)

Art. 1461. Things having a potential existence may be the object of the contract of sale.

The efficacy of the sale of a mere hope or expectancy is deemed subject to the condition that the thing will come into existence.

The sale of a vain hope or expectancy is void. (n)

Art. 1462. The goods which form the subject of a contract of sale may be either existing goods, owned or possessed by the seller, or goods to be manufactured, raised, or acquired by the seller after the perfection of the contract of sale, in this Title called " future goods ."

There may be a contract of sale of goods, whose acquisition by the seller depends upon a contingency which may or may not happen. (n)

Art. 1463. The sole owner of a thing may sell an undivided interest therein. (n)