Online Students

For All Online Programs

International Students

On Campus, need or have Visa

Campus Students

For All Campus Programs

What is a Capstone Project in College?

The capstone project in college is the apogee, or completion marker, of a student's coursework leading to the culmination of their program with a degree in their chosen field of study. The original definition of a capstone focuses on the actual stone placed at the top of a wall or building, marking the successful completion of the structure. It's a significant and celebrated piece of architecture, considered to be the most important of an entire construction project.

"(Capstone projects are) the apex of all a student's work done throughout their college career," said Dr. Jeff Czarnec , a social sciences adjunct online and on-campus at Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU). Retired after 23 years in law enforcement, Czarnec served as an associate dean of criminal justice and social sciences at SNHU for nearly a decade. He now leverages his extensive background to teach social sciences, enriching the academic experience with his practical insights.

When entering a capstone course, there's an expectation that you have all the necessary skills and knowledge to be successful.

You have the opportunity to pick a research topic that is of interest to you and run with it. "After having to write research papers in all of their courses prior to (the capstone), the task is not one to dread, but to enjoy. It is their time to shine as students and to enjoy the journey," MacCarty said.

A capstone course is more than a potential degree requirement. It can serve as an opportunity to demonstrate knowledge mastery and creative thinking, which may help you stand out to potential employers.

What is Involved in a Capstone Project?

Each university, program and instructor may have different requirements — or models — for a capstone project. According to Czarnec, a general design might first include selecting a topic of interest that the instructor will approve.

Czarnec said that, depending on the program, a capstone may include anything from a video presentation or an architectural model to an art exhibit or short film; however, it almost always includes a paper demonstrating an introduction, theory, evaluation, research and individual issues relevant to the proposal.

"Students are expected to be ready to enter the world as professionals in their field upon completion of the capstone course," said MacCarty.

The time it takes to complete a capstone project usually depends on the course's length. If you're in an undergraduate online program at SNHU, for instance, your capstone course would take eight weeks to complete, Czarnec said.

Capstone courses are research-based, and you can choose your topic early on, allowing you more freedom to conduct research independently. Capstone topics usually align with a program's specific disciplines, too.

For example, in the social sciences realm, "our focus is on human behavior and cognition, which may be different from a capstone course in business or STEM," MacCarty said.

Find Your Program

Types of capstones.

There are many types of capstone projects that you could consider, and they vary from learner to learner, Czarnec said. "Some will investigate issues or phenomenon that they are familiar with either professionally, personally or courtesy of a discipline-related source, such (as) a police or human services agency," he said.

In a nutshell, a rough outline of a capstone, according to Czarnec, may look something like this:

- Select a topic and have it approved by the instructor

- Evaluate relevance to the proposal

- Perform necessary research

- Present results in the agreed-upon fashion

Czarnec said that if you're looking for a capstone topic, you may consider focusing on an area you're passionate about or you could also try to ask you instructor for some assistance. For example, Czarnec said that he can act as a guide, mentor, editor and research resource for his students to help them focus and narrow their search for a capstone topic.

Are Capstone Projects Difficult?

"Not necessarily," said Czarnec. "It does force you to be efficient and very specific to topic. No fluff. Straight forward. Razor sharp."

The capstone is more of an opportunity to catch your breath, he said, and to retrace and pull up what you have learned in a more stress-free environment .

"It helps validate students as learners," Czarnec said.

Depending on the major and course requirements, there may be opportunities to connect with outside contacts, not only to assist with the capstone project research and problem statement but also to provide a networking community .

"Not every research project is, nor should they be, the same," Czarnec said. "Everyone has a different approach."

What is the Difference Between a Thesis and a Capstone Project?

A capstone is similar to a thesis in that the starting point involves the strengths needed for a thesis or dissertation work. For example, you may need to consider the skeletal structure of research and form your theory, hypothesis and problem statement.

"While a capstone is certainly a scholarly piece of work and does share some aspects of a thesis, the time and detail that is required of a master's thesis is greater," MacCarty said.

A capstone paper may be 25 pages, whereas a thesis could be 100 or more. If you choose to further your education beyond a bachelor's degree, the capstone project could be an invaluable tool in preparing for a graduate thesis.

Capstone Projects are About Your Success

Capstones of all programs are leading you to the end game, Czarnec said. The goal is to develop you into a well-rounded thinker who can pull their work together in a coherent, articulate, well-organized fashion while considering the demands of the profession or vocation you're interested in.

The focus and intent of a capstone should be to create an effective device to assess and measure all that you've learned throughout your program in an aggregate fashion so you can demonstrate your life-long vocational skills in a nice, neat package.

"My goal is for students to leave the program confident about their skills and abilities," said Czarnec.

MacCarty said that capstone courses should be structured to support your success in fulfilling program requirements and allow you the opportunity to showcase your academic abilities and skills gained throughout your degree program.

A degree can change your life. Choose your program from 200+ SNHU degrees that can take you where you want to go.

Laurie Smith '14 is a writer, editor and communications specialist. Connect with her on LinkedIn .

Explore more content like this article

Is a University Degree Worth It?

How Long Does it Take to Get a Master's Degree?

How to Survive High School and Prepare for College

About southern new hampshire university.

SNHU is a nonprofit, accredited university with a mission to make high-quality education more accessible and affordable for everyone.

Founded in 1932, and online since 1995, we’ve helped countless students reach their goals with flexible, career-focused programs . Our 300-acre campus in Manchester, NH is home to over 3,000 students, and we serve over 135,000 students online. Visit our about SNHU page to learn more about our mission, accreditations, leadership team, national recognitions and awards.

Created by the Great Schools Partnership , the GLOSSARY OF EDUCATION REFORM is a comprehensive online resource that describes widely used school-improvement terms, concepts, and strategies for journalists, parents, and community members. | Learn more »

Capstone Project

Also called a capstone experience , culminating project , or senior exhibition , among many other terms, a capstone project is a multifaceted assignment that serves as a culminating academic and intellectual experience for students, typically during their final year of high school or middle school, or at the end of an academic program or learning-pathway experience . While similar in some ways to a college thesis, capstone projects may take a wide variety of forms, but most are long-term investigative projects that culminate in a final product, presentation, or performance. For example, students may be asked to select a topic, profession, or social problem that interests them, conduct research on the subject, maintain a portfolio of findings or results, create a final product demonstrating their learning acquisition or conclusions (a paper, short film, or multimedia presentation, for example), and give an oral presentation on the project to a panel of teachers, experts, and community members who collectively evaluate its quality.

Capstone projects are generally designed to encourage students to think critically, solve challenging problems, and develop skills such as oral communication, public speaking, research skills, media literacy, teamwork, planning, self-sufficiency, or goal setting—i.e., skills that will help prepare them for college, modern careers, and adult life. In most cases, the projects are also interdisciplinary, in the sense that they require students to apply skills or investigate issues across many different subject areas or domains of knowledge. Capstone projects also tend to encourage students to connect their projects to community issues or problems, and to integrate outside-of-school learning experiences, including activities such as interviews, scientific observations, or internships.

While capstone projects can take a wide variety of forms from school to school, a few examples will help to illustrate both the concept and the general educational intentions:

- Writing, directing, and filming a public-service announcement that will be aired on public-access television

- Designing and building a product, computer program, app, or robot to address a specific need, such as assisting the disabled

- Interning at a nonprofit organization or a legislator’s office to learn more about strategies and policies intended to address social problems, such as poverty, hunger, or homelessness

- Conducting a scientific study over several months or a year to determine the ecological or environmental impact of changes to a local habitat

- Researching an industry or market, and creating a viable business plan for a proposed company that is then “pitched” to a panel of local business leaders

For related discussions, see authentic learning , portfolio , relevance , and 21st century skills .

As a school-reform strategy, capstone projects are often an extension of more systemic school-improvement models or certain teaching philosophies or strategies, such as 21st century skills, community-based learning , proficiency-based learning , project-based learning , or student-centered learning , to name just a few.

The following are a few representative educational goals of capstone projects:

- Increasing the academic rigor of the senior year. Historically, high school students have taken a lighter course load or left school early during their twelfth-grade year, which can contribute to learning loss or insufficient preparation for first-year college work. A more academically and intellectually challenging senior year, filled with demanding but stimulating learning experiences such as a capstone project, the reasoning goes, can reduce senior-year learning loss , keep students in school longer (or otherwise engaged in learning), and increase preparation for college and work.

- Increasing student motivation and engagement. The creative nature of capstone projects, which are typically self-selected by students and based on personal interests, can strengthen student motivation to learn, particularly during a time (twelfth grade) when academic motivation and engagement tend to wane.

- Increasing educational and career aspirations. By involving students in long-term projects that intersect with personal interests and professional aspirations, capstone projects can help students with future planning, goal setting, postsecondary decisions, and career exploration—particularly for those students who may be unfocused, uncertain, or indecisive about their post-graduation plans and aspirations.

- Improving student confidence and self-perceptions. Capstone projects typically require students to take on new responsibilities, be more self-directed, set goals, and follow through on commitments. Completing such projects can boost self-esteem, build confidence, and teach students about the value of accomplishment. Students may also become role models for younger students, which can cultivate leadership abilities and have positive cultural effects within a school.

- Demonstrating learning and proficiency. As one of many educational strategies broadly known as demonstrations of learning , capstone projects can be used to determine student proficiency (in the acquisition of knowledge and skills) or readiness (for college and work) by requiring them to demonstrate what they have learned over the course of their project

In recent years, the capstone-project concept has also entered the domain of state policy. In Rhode Island, for example, the state’s high school graduation requirements stipulate that seniors must complete two out of three assessment options, one of which can be a capstone project. Several other states require students to complete some form of senior project, while in other states such projects may be optional, and students who complete a capstone project may receive special honors or diploma recognition.

Most criticism of or debate about capstone projects is not focused on the strategy itself, or its intrinsic or potential educational value, but rather on the quality of its execution—i.e., capstone projects tend to be criticized when they are poorly designed or reflect low academic standards, or when students are allowed to complete relatively superficial projects of low educational value. In addition, if teachers and students consider capstone projects to be a formality, lower-quality products typically result. And if the projects reflect consistently low standards, quality, and educational value year after year, educators, students, parents, and community members may come to view capstone projects as a waste of time or resources.

Alphabetical Search

What Is a Capstone Project in University?

Access thousands of exclusive scholarships for free

"Be Bold" No-Essay Scholarship

Importance of Capstone Courses

Characteristics of capstone projects, capstone project vs. capstone course, examples across various majors, capstone project process, benefits for students, challenges and tips, frequently asked questions about capstone in university.

Confused with the concept of a capstone project ? As you approach your senior year, you might be hearing about this culmination project—whether a research endeavor, final paper, application, or portfolio— this academic endeavor aims to showcase the depth of your learning throughout your college years and prepares you for the professional world.

In this blog post, I will explore what it means, how to prepare for it, and how you can bring this academic achievement to life. I'll guide you through this process, ensuring you have the support and resources you need. With the right guidance and understanding, you can transform this challenging task into an opportunity for growth and real-world application.

Start applying for school scholarships now ! There are thousands of applications open for the upcoming school year!

Capstone courses are part of university curricula and are strategically designed to prepare students for a seamless transition from academia to the workforce. They may include research endeavors and theses. However, each has a distinct focus and purpose.

These projects often highlight practical applications and skill enrichment, making them more aligned with professional practice (often done as a group project).

On the other hand, research and theses contribute to the academic body of knowledge, delving deeper into theoretical aspects. Bridging this knowledge gap is essential to empowering students with the understanding needed to make informed decisions about their final-year assessments.

In a broader context, a capstone project is designed to integrate theoretical knowledge with practical application. It provides a platform to reflect on academic journeys, apply acquired knowledge to real-world scenarios, and develop problem-solving skills. By addressing tangible challenges, learners enhance their readiness for the professional world.

The benefits of capstone projects extend beyond academic prowess. They empower students to navigate complex, work-related issues, through practical experience and fostering a deeper understanding on a particular subject.

This synthesis of knowledge and practical application enriches the graduate student's educational experience and typically involves graduates with a skill set essential for success in their higher education.

Although the terms "capstone project" and "capstone course" are often used interchangeably, it's necessary to understand their differences:

A capstone project is an independent assignment that encapsulates students' academic learning and demonstrates their proficiency in a specific discipline or field.

The focus is on individual research, problem-solving, or creative endeavors, providing a medium to demonstrate the knowledge acquired as students finish their studies. A capstone project is part of a course (think of it as a final assignment).

A capstone course contains a broader coursework and educational experience. It is an entire course (like any other) in which students incorporate and apply their knowledge gained throughout a program. It often requires students to collaborate on projects, engage in discussions, and participate in various activities. It can take longer to complete and varies depending on the institution.

Students across different degree programs engage in multifaceted capstone experiences at the end of their college careers. These experiences can vary widely, from individual research to collaborative group endeavors, reflecting the essence of their academic achievements.

For example, in fields such as political science, students may delve into a senior thesis, conducting extensive research and showcasing their critical thinking skills.

Alternatively, within literature courses, the last capstone course may involve a comprehensive literature review, illustrating the culmination of knowledge and skills acquired throughout the course of the degree program.

Get Matched to Thousands of Scholarships

Create your Bold.org profile to access thousands of exclusive scholarships, available only on Bold.org.

Many capstone courses extend beyond conventional research papers, requiring you to work on a final project addressing a real-world problem. This collaborative effort and practical method, which can be conducted in small groups, emphasizes teamwork, a significant amount of research, and a strong work ethic (fundamental skills that prepare students for the workplace).

In addition to meeting the degree program and requirements, these capstone experiences often involve a final exhibition, allowing students to present and demonstrate their problem statement to professors, other students, peers, and sometimes even external stakeholders.

A capstone course experience serves as a bridge to graduate degrees or even doctorates, honing research capabilities that are essential for success and develop the necessary skills for potential employers.

As Jolanta Burke and Majella Dempsey highlight in their Practical Guide for Students Book , commencing a capstone project is like constructing a house:

Firstly, you must establish solid foundations, much like a house, ensuring reliability. Then, continue learning and enhancing your skills to build it. Once armed with the necessary skills and information, the next step is to decide on the materials, devise a plan of action, and follow through until the house—your project—is complete and ready for use.

Just as a house requires a robust foundation, a capstone project initiates with meticulous planning. This phase encompasses defining content, goals, and methodologies, ensuring the project demonstrates most capstone courses.

For instance, if your project revolves around human-centered design, identify a problem, such as a shortage of shelters in a city, and conduct research. Then, the person and approach to solving this problem should be determined, perhaps by studying the owner of an existing shelter and identifying gaps in current approaches.

While delving into extensive research, it's crucial for students to hone academic capabilities by studying other courses and examining what has already been done about the specific problem. Seeking input from people, professors, and TAs are invaluable. Once enough material, like a literature review or interviews, is gathered, present it to your professor for feedback before progressing.

Pre-Execution

Jus like choosing construction materials for a house, students must decide on materials and formulate a detailed action plan, meeting degree or course requirements. This phase demands careful consideration of methodologies and strategies, emphasizing material determination—whether it's an app, a history psychology project, or any other course. Craft a structured plan and present it as a proposal before delving deeper into the subject.

The final stage involves executing the plan and completing the project, demonstrating the capstone experience. The research project needs to be prepared for use, showcasing the culmination of efforts.

Presentation

The presentation serves as the grand reveal of the completed project. A well-structured project and a compelling pitch, typically required, is essential to demonstrate its readiness for use.

This approach ensures a seamless transition from planning to execution, essential for success in capstone courses and the culmination of their academic journey.

The preparatory nature of these projects makes students discover what they enjoy the most, what comes easily, and the potential to find areas of improvement. The benefits are crucial for student' personal and professional development, providing a real connection between academic knowledge and real-world application.

Gaining Skills and Experiences

Capstone projects showcase the skills and experiences accumulated throughout a student's educational journey. From research prowess to critical thinking and effective communication, the project culminates in these proficiencies, bringing them to the student's forefront.

Practical Transition to the Next Phase

Capstone projects are vital in preparing students to transition to the professional world or advance in academic pursuits. It's a practical initiation into college career, familiarizing students with the challenges and responsibilities they'll encounter in their future careers or advanced degrees at other schools.

Initiation of Work or Advanced Studies

Working on a capstone project program allows students to navigate the complexities they'll encounter in their chosen field. This experiential learning program equips them with valuable insights and the confidence and adaptability required to transition to the professional world or pursue advanced degrees.

Holistic Development for Future Success

Capstone projects contribute significantly to students' and major programs' holistic development, ensuring they are academically qualified and possess the practical skills demanded by prospective employers for their future endeavors.

Here are some potential burdens and some capstone journey strategies that have helped me throughout my projects during school.

Choosing a Subject:

- Challenge: Defining the size of your capstone project can be daunting. I recommend balancing ambition with feasibility. For example, if you are trying to help dog shelters, maybe focus on how to prevent owners from abandoning them by educating dog owners. In the case of a more research-based project, look at the literature review of your research focus and build upon what has already been investigated.

- Strategy: Begin with a clear project scope and revisit the risks regularly. Prioritize key objectives to avoid complicating your project, and focus on a single issue .

Time Management:

- Challenge: Capstone projects often overlap with other academic commitments. Time management becomes paramount.

- Strategy: Create a detailed timeline, allocating specific tasks to manageable time frames. Regularly reassess and adjust as needed.

Research Roadblocks:

- Challenge: Conducting extensive research may lead to information overload or difficulty finding relevant sources.

- Strategy: Define research questions early. What is the project doing? For whom? In what builds upon? Utilize academic databases and seek guidance from mentors for targeted resource discovery.

Team Dynamics (if applicable):

- Challenge: Group projects may need help coordinating schedules, differing work styles, or conflicting ideas.

- Strategy: Establish clear communication channels, set expectations from the beginning, and address conflicts promptly.

What exactly is a capstone project?

A capstone project is a culmination endeavor in your last year of college. This final assignment showcases the knowledge you acquired throughout your college years. It's a bridge between academia and the professional world, demonstrating the complete scope of your learning.

How do capstone courses differ from capstone projects?

A capstone project is an independent culminating assignment reflecting academic individual proficiency. On the other hand, a capstone course is an entire academic course that may involve collaborative projects, discussions, diverse activities, and presentations.

What are the benefits and challenges of capstone projects?

Capstone projects offer transformative experiences, unveiling skills and experiences gained through academic years. The benefits include skill refinement, self-discovery, and a practical transition to the professional realm.

However, challenges such as choosing a subject, time management, research roadblocks, and team dynamics may arise. Strategies like clear project scoping, time management, focused research questions, and effective team communication can help overcome these challenges.

Start paying for school smarter. Register at Bold.org to discover simple scholarships for school!

Related Posts

Best colleges in new mexico, best colleges in hawaii, remote jobs for college students.

- Our Mission

6 Tips for Engaging Capstone Projects

Rather than creating a year-in-review capstone project, consider having students synthesize and personalize what they’ve learned, bringing it to a new level.

It’s that time of the year, the race to the finish, only weeks until school ends for the summer (at least for many of us). With the pressures of testing behind us, we often have a bit more freedom to create curriculum and activities for students. We can try out new ideas, give students more choice in what they want to learn, and celebrate the learning that we've accomplished this year. One way that many educators like to do these things is through capstone projects, year-end culminations that often invite students to engage in choosing what they want to learn, as well as how they learn it. Capstone projects are a great tool for personalizing learning, and they're effective for creating even more student engagement. Here are some tips to create excellent capstone projects.

Ensure "Main Course, Not Dessert"

This is always a good reminder. While capstone projects often draw on the entire year's learning, it's important to pose this question to students as well as reflecting upon it ourselves as educators: What new learning will occur in this capstone project? This is key to ensuring that a capstone project isn't simply a fun activity (although that's still a good intention), and it helps in creating a project that's more challenging and truly focused on new learning and experiences. This new learning could be in a different context or topic from what the class has done so far, it might require a variety of skills that they haven't previously combined, or it could be a synthesis of sorts. Reflect on how you can ensure that there will be new learning in your capstone projects.

Take It To Another Level

Projects should focus on depth, not breadth. If you have the ability to allow students choice in what they learn, consider having them revisit a previously learned concept, topic, or skill. To ensure not only engagement but also "Main Course," create rubrics with students that focus on their going deeper into the content. Instead of "meeting standard," focus the assessment and learning on "exceeding standard." When students engage with a challenge, we should take them beyond the opportunity to review learning by pushing the learning even farther in a capstone project.

More Voice and Choice

This is nothing new, but we can always think of new ways to offer choice to our students. At the end of the year, after we've pressed through most of our required curriculum and standards, we may have some wiggle room on what students can learn. We might offer choice in one way, but not in another. Perhaps we want to spiral review a writing skill for all students, but offer them a choice in what history topic they want to learn about. Or we might need students to learn a math concept that we haven't yet covered in the curriculum, but they can choose how they want to learn it and connect that concept to the real world. Have students make personal, meaningful choices. See my previous blog about voice and choice for ideas about how to create more engagement.

Make a Difference

One of my favorite ways of taking capstone projects to another level is through service and making a difference. When students see that their work matters, they will be engaged. There are, of course, lots of opportunities to make an impact outside of the walls of the classroom, whether in the community or globally. There are also great ways for students to make a difference in their own lives once they understand the personal impact that's possible. Start by asking then how they want to make a difference in their capstone projects.

Tell the Full Story Through Assessment

Often, capstone projects involve what could be called a portfolio of student learning, which includes many steps in their yearlong journey. These assessments, graded or not, are valuable artifacts that serve as a photo album of a learning continuum, rather than simple snapshots representing individual moments of learning. Capstone projects are about growth, and both teachers and students can use assessments from the capstone project as well as earlier in the year to celebrate the growth in learning. Students, parents, and teachers deserve to see this growth in order to be proud of their learning from the entire year as well as during the capstone project.

Experiment With "No Grades"

Often we use grades as a way to get students to learn rather than addressing a root problem -- our students are not engaged. While you might want to grade students on their work, you might also try the experiment of moving students away from grades as a motivator, and instead focus on the learning. Rather grading every part of the capstone project, consider grading only the capstone component. This is also in ideal place to start the conversation with students about how they want to be and should be graded. Consider using capstone projects to start a culture shift away from grades and toward learning.

I love implementing and watching students implement capstone projects. I'm inspired by the ways that teachers structure these projects and by the amazing learning that students share. Capstone projects are truly an opportunity to create meaningful learning along with powerful engagement and impact. How do you create engaging capstone projects?

Designing Capstone Experiences

Main navigation.

Starting with the graduating class of 2025, all Stanford undergraduates are required to complete a capstone project as part of their major (see capstone.stanford.edu ).

Capstones have been identified as a high-impact educational practice , providing opportunities for students to integrate and apply what they have learned during their major courses of study, strengthen relationships with instructors and mentors, and experience a range of personal and practical benefits.

CTL is excited to support departments and programs in the implementation of capstones. For all questions, email Kenneth Ligda at [email protected] , or file a CTL consultation request .

Exemplary capstone projects at Stanford

Capstones may take many forms, ranging from honors theses to community projects, seminars to group projects, e-Portfolios to research papers.

Many models for successful capstones already exist across Stanford departments and programs. Here, we provide a few exemplars to give a sense of both the possibilities and practicalities in this work.

Each of these capstone exemplars excel in two critical areas:

- providing opportunities for student-guided learning

- structuring experiences to help students meet challenging goals.

Through the capstone, students are often tasked with open-ended questions that push them to find novel or original answers. This offers students a unique opportunity to explore their own interests and direct their own learning. Whether students work on a team-based or individual project, they must use the knowledge and skills they have gained throughout their education to tackle complex problems that are often interdisciplinary in nature.

Preparing students for this kind of work can be challenging. A good place to start is with the learning goals from our capstone exemplars. The instructors identify important learning goals for their students that will help them transition into independent work and guide their own learning throughout the capstone.

But what happens when a student struggles with these ambitious learning goals? The capstone exemplars also discuss how their capstones have evolved over time to provide students with continuous support and feedback to help them throughout their capstone experience. The instructors describe how their capstones are structured to ensure students have clear guidelines at the start of their capstone and multiple checkpoints to meet the intended capstone learning goals.

Urban Studies

Bioengineering

Religious Studies

Human Biology

CTL offers the Capstone Experience Design (CapED) program to all departments and programs conferring undergraduate major degrees.

CapED is a two-day intensive to focus efforts on designing a successful capstone experiences. Modeled after CTL’s renowned Course Design Institute (CDI), CapED provides departments and programs a collaborative environment in which to design capstone experiences for their majors. Teams or individuals are welcome, and may include faculty, lecturers, staff, and undergraduate majors.

In CapED, we apply current research in teaching and learning to design effective and inclusive capstone projects suitable for diverse student majors. Learning goals for CapED participants include:

- Articulating student learning goals for the capstone project

- Drafting a capstone curriculum aligned with capstone learning goals and the major curriculum

- Integrating research-based practices into the capstone curriculum

- Evaluating capstone design to ensure equity and inclusion for all majors

- Receiving feedback from mentors in departments/programs with a capstone project

CapED Workshops and Materials

We are not currently planning another instance of CapED, but if you or your department/program are interested, please contact Kenny Ligda, [email protected] , for workshop materials or for a customized offering for your group.

Capstone Projects

The Capstone is a culminating academic project experience that is completed within the confines of a semester-length course. Several Master of Liberal Arts (ALM) fields either require a capstone or offer the option to pursue one. In addition to the information below, review Guide to the ALM Capstone Project website.

Types of Capstones

We offer two forms of capstone: Capstone Course (faculty directed) and Capstone Independent Project (student directed).

Capstone Course–Faculty Directed

For the ALM fields of anthropology, biotechnology, creative writing and literature, computer science, cybersecurity, data science, English, government, history, international relations, math for teaching, psychology, religion, and systems engineering capstones are courses designed by faculty members who bring together, in a structured syllabus, all the key learning outcomes of the field of study.

Our cybersecurity, data science, and computer science capstones are team-based projects that have a real-world industry partner as the client for your research.

While our creative writing capstone allows for ample room to work on individual artistic projects, but with the added benefit of weekly engagement with peers and the instructor–a supportive writer’s community.

Every effort is made to offer the same precapstone/capstone topics each year (e.g., human development, policy analysis, and social justice); however, topics are subject to change annually.

Good academic standing. You must be good academic standing to register for the capstone. If not, you’ll need to complete additional courses to bring your GPA up to the 3.0 minimum prior to registration. For detailed course description information, including specific registration requirements, such as credit minimums and academic standing requirements, use the Degree Course Search .

Tip: Register on the first day of early degree-candidate registration to obtain a seat in these limited-enrollment courses.

Precapstones

The ALM fields of anthropology, biotechnology, computer science, creative writing and literature, cybersecurity, data science, English, government, history, international relations, psychology, religion and systems engineering have a required precapstone course that must be completed with a grade of B- or higher.

Mandatory Sequencing of Precapstones/Capstones. You enroll in the precapstone and capstone courses in back-to-back semesters (fall/spring), with the same instructor, and in your final academic year.

Due to heavy workload demands, all your other degree requirements must be fulfilled prior to capstone registration. The capstone must be taken alone as your one-and-only remaining degree requirement. You cannot register in any other courses along with the capstone.

It is critical that you draw upon your entire ALM training to produce a project worthy of a Harvard degree by committing to full-time study in the capstone.

Engaging in Scholarly Conversation . For precapstones in anthropology, English, government, history, international relations, psychology or religion, you need to have completed Engaging in Scholarly Conversation prior to precapstone registration. If you were admitted after 9/1/2023, Engaging in Scholarly Conversation (A and B) is required; if admitted before 9/1/2023, this series is encouraged.

Attempts . You have a maximum of two attempts at the precapstone course to earn the required grade of B- or higher. If after two attempts, you have not fulfilled the requirement (a WD grade is considered an attempt), your degree candidacy will expire. If by not passing the precapstone you fall into poor academic standing, you will need to take additional degree-applicable courses to return to good standing before enrolling in the precapstone for your second and final time.

The second attempt policy is only available if your five-year, degree-completion deadline allows for more time. If you attempt to complete the precapstone in your final year and don’t pass (including a WD grade), your candidacy will automatically expire.

For detailed course description information, visit the Degree Course Search .

Capstone Independent Project–Student Directed

For global development practice, digital media design, journalism, museum studies, and sustainability, capstones are client-based or independent research projects focused on a current issue or problem that has become compelling for you during your course of study. The project represents your academic passion and professional interest. You complete the research individually (journalism) or in a classroom setting with fellow candidates (all other fields).

Journalism candidates should scroll down to Journalism Capstone. The following applies to:

- Global Development Practice

- Digital media design

- Museum studies

- Sustainability

Registration in the capstone for the above fields has the following prerequisites: (1) your specific research project must be approved several months in advance (prior to enrolling in the precapstone tutorial), (2) you must successfully complete the precapstone tutorial, and (3) the capstone must be your final, one-and-only remaining degree requirement. You cannot register for any other courses along with the capstone.

There are two major steps to obtain project approval.

Step one: obtain advice right away. Once admitted to the program, meet with your research advisor early and often about your initial capstone research interests. He or she can provide support as well as course selection advice as you develop preliminary ideas. Please note that while every effort is made to support your capstone interest, guidance is not available for all possible projects. Therefore, revision or a change of capstone topic may be necessary.

- For museum studies your capstone will have a main focus on (1) business of museums, (2) collections care, (3) exhibition design, (4) museum education, or (5) technology. Whatever focus you choose, you must have at least two courses completed in that area before enrolling in the precapstone tutorial. If not, your enrollment will not be approved.

- Due to the highly technical nature of their projects, digital media students must meet with their research advisor, Dr. Hongming Wang, to discuss their capstone topics according to the following schedule. Between January 2 and February 15 for summer precapstone and between May 1 and July for the fall precapstone. Appointments can be scheduled through the Degree Candidate Portal.

- Step two: register for the noncredit tutorial. The semester before capstone registration (no earlier), you are required to (1) enroll in the noncredit Precapstone tutorial, (2) visit the Guide to the ALM Capstone Project website to read through the tutorial guidelines, and (3) submit your prework by the required deadline (see below in bold).

Prework demonstrates that you have done enough prior reading and research on your topic to begin the capstone proposal process. Registration in the tutorial is limited to degree candidates who submit quality prework. If your prework is not approved, you will need to spend time revising in order to re-submit for the next offering of the tutorial, if your five-year, degree-completion deadline allows.

Once registered in the noncredit tutorial, you will receive guidance and mentoring while you iterate on your individual capstone proposal until the document reaches a satisfactory quality. The tutorial is not a course in the traditional sense. You work independently on your proposal with your research advisor by submitting multiple proposal drafts and scheduling individual appointments (ordinarily, during the hours of 9-5). You need to make self-directed progress on the proposal without special prompting from the research advisor. While the tutorial is noncredit, your due diligence throughout the semester is required.

If you do not have a proposal that is close to being approved by the semester’s withdrawal deadline, you’ll need to withdraw from the tutorial, delay capstone registration, and re-take the capstone proposal tutorial again in a future semester, if your five-year, degree-completion deadline allows.

- For the fall capstone, you complete the proposal tutorial during the prior summer term: Register for the Summer Precapstone tutorial March 1. Submit the first draft of the preproposal between March 1 and May 15 . Actively participate in the tutorial during the summer and end the term with an approved proposal. Register and complete capstone in fall.

- For the spring capstone, you complete the proposal tutorial during the prior fall term: Register for the Fall Precapstone tutorial when registration opens in mid-July. Submit the first draft of the preproposal between July 18 and August 1 . Actively participate in the tutorial during the fall and end the term with an approved proposal. Register and complete the capstone in spring.

- For the summer capstone, you complete the proposal tutorial during the prior spring: Register for the spring Precapstone tutorial when registration open in early November. Submit the first draft of the preproposal between November 7 and January 2 . Actively participate in the Capstone Proposal Tutorial during the spring and end the term with an approved proposal. Register and complete capstone in summer. This sequence (spring tutorial, summer capstone) is required for international students who need a student visa.

Please note that not all fields offer a capstone each term. Refer to your field’s Degree Course Search for the schedule.

Human Subjects

If your capstone will involve the use of human subjects (e.g., subject interviews, surveys, observations), review the Human Subjects section on the Guide to the ALM Capstone Project website to learn Harvard University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval process.

Journalism Capstone

Over the course of the capstone semester for JOUR E-599 , you’ll conduct an in-depth investigation of a single topic and emerge with a portfolio of new work suitable for publishing, posting, or broadcasting. The portfolio requires you to produce several (at least three) related stories on one topic written specifically for the capstone course. (No prior work can be used.) The stories are completed over the course of one semester.

You can register for the capstone once you complete 36 credits, and you work independently to complete the project within a semester time frame. The capstone can be, and often is, completed at a distance.

To begin the capstone approval process, you schedule an appointment with your research advisor, June Erlick, ( [email protected]) , to discuss your capstone ideas.

While every effort is made to support your capstone interest, guidance is not available for all possible projects. Therefore, revisions or a change of capstone topic may be necessary before it is approved. As in all traditional journalism, projects must take a fair and balanced view by bringing in differing points of view. Projects should not be one-sided or take an advocacy stance.

Once a topic is approved, you submit the first draft of your capstone proposal. (Visit the Guide to the ALM Capstone Project website to read the specific guidelines for Crafting the Capstone Proposal). Ms. Erlick supports you through the fine tuning of the proposal and works with the Journalism program office to identify a capstone director. Once approved, capstone topics cannot be changed. In the unlikely event that you cannot continue with the project as approved, you must request and receive written permission to pursue a new topic from Ms. Erlick.

A capstone director is a journalism instructor or professional in the field who has expertise relevant to your capstone topic. The final decision about who will serve as director is made by the Journalism program office; however, you are welcome to request a particular instructor. However, we ask that you not contact an instructor directly prior to capstone approval.

You are expected to work independently on your project with support and direction from the director. The capstone director will meet with you several times over the semester to answer questions, discuss your progress, read drafts, and offer feedback. The director also grades the final project.

Journalism Timeline

- Fall capstone: Meet to discuss capstone ideas by May 1. Submit first draft of capstone proposal by June 1.

- Spring capstone: Meet to discuss capstone ideas by September 1. Submit first draft of capstone proposal by October 1.

- Summer capstone: Meet to discuss capstone ideas by February 1. Submit first draft of capstone proposal by March 1

Final Capstone Grade

You need to earn a grade of B- or higher to earn degree credit for the capstone. If you earn a grade below a B– (including a WD), you will need to petition the Administrative Board for permission to enroll in the capstone for one final time. The Board only reviews cases in which extenuating circumstances prevented the successful completion of the capstone.

Moreover, the petition process is only available if your five-year, degree-completion deadline allows for more time. Your candidacy will automatically expire if you do not successfully complete the capstone requirement by your required deadline.

If approved for a second attempt, you may be required to repeat the precapstone course or the non-credit precapstone tutorial. Please note that you cannot choose a different precapstone/capstone sequence to gain additional (more than two) attempts at fulfilling the capstone requirement for your degree.

If by not passing the capstone you fall into poor academic standing, you’ll need to take additional degree-applicable courses to return to good standing before enrolling in the capstone for your second and final time. This is only an option if your five-year, degree-completion deadline allows for more time to take additional courses.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

Welcome to Capstone Projects in Education: Learning the Research Story. This book is designed to facilitate understanding of educational research and guide the development and the writing of a capstone project. Scholarly research follows a basic format, though each discipline has its own variations. The discipline of education is no different. In education, like other social sciences, we are investigating issues directly involving or influencing humans. Research involving humans can be a complex and awkward endeavor. However, if we view this endeavor through the lens of a research story, we find a familiar genre we can relate to and understand.

The book is divided into two parts. Part I – Research, Forms, Functions, and Skills explores the fundamental forms and functions of various graduate research projects. These chapters will introduce you to the ways in which we can tell a research story. We will also investigate the essential writing skills required to effectively write your research story. Academic writing rarely comes naturally to students. In these chapters, you will learn to tell your research story while also learning to write the story in a scholarly way.

Part II – Capstone Components of this book is dedicated to exploring each component for developing and writing a capstone project. We will explain each of the components through the story of a “slow cat.” The story of the slow cat is designed to assist the reader in drawing analogies to their research. As the story develops over the course of the chapters in Part II, you will see how a research project is created, how it progresses, and how it is concluded. Each chapter begins with a segment of the story of the slow cat, followed by an interpretation of the story related to the project component. The chapter continues with explanations, discussions, and information to facilitate your understanding and writing of the component.

The Capstone Projects in Education: Learning the Research Story is written for graduate students engaged in a research project. However, the components of research apply to any level of education research. The hope is this text will make the basics of educational research projects more accessible to all. Telling the research story is an important pursuit to support educational change and improvements. While most graduate education programs require some form of research, we believe that it does not have to be the “hardest,” “most challenging,” or “most painful thing” encountered. If we can connect students to the research story, perhaps we will see higher-quality projects and some amazing innovations to enhance education for the betterment of all humans!

As a final note, be aware this book does not include a deep dive into research design, nor does it contain an exhaustive treatment of the components of educational research. We encourage you to seek other resources that are specifically written about your research design of choice. There are many textbooks available on research. Supplement your learning as needed, is our advice.

Capstone Projects in Education: Learning the Research Story Copyright © 2023 by Kimberly Chappell and Greg I. Voykhansky is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- All Programs

- EdUprising Conference

- Innovation Zones

- X3 Internships

- X3 for Employers

- Youth Voices

Top 7 Myths About Capstones

The top 7 myths about capstones.

A student at Siembra Leadership High School presents her learning in a formal presentation in front of her teachers, mentors, and community members.

In New Mexico, a major policy shift is taking place: senior capstone projects will be a new pathway to graduation . This new project-based graduation pathway culminates with senior exhibitions—known as “capstones”—to demonstrate learning, as an alternative to standardized tests.

Across the state there is confusion about what a capstone is and how it will affect our students and educators . Read on to learn why many of these misunderstandings are myths that are readily debunked…

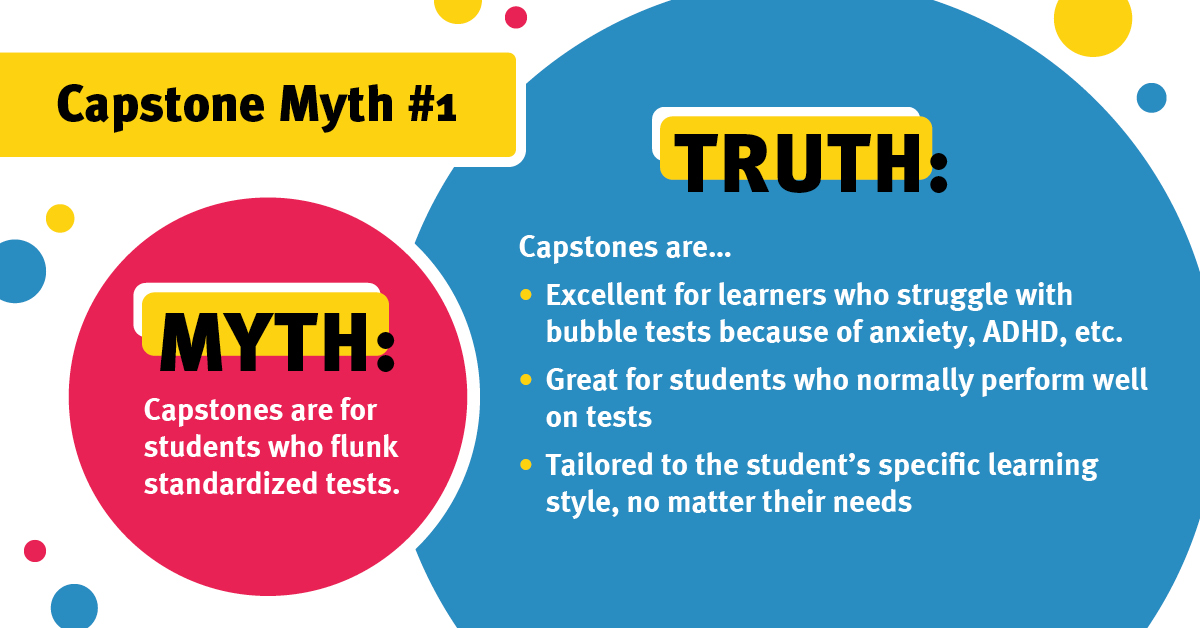

1. “Capstones are only for students who flunk the test.”

Capstones have been used as an “Alternate Demonstration of Competency” for graduation in New Mexico for many years—an option for students who did not pass the myriad exit exams offered. This has led to the misperception that capstones are a “last resort” option for students who struggle with standardized tests.

It is true that capstones are a great option for learners who under-perform on bubble tests because of anxiety, ADHD, or other factors. However, they also serve the needs of students who normally perform well on tests, too. This is because capstone projects are individualized and tailored to the student’s specific learning style.

New Mexico is moving to a new model where capstone assessments are not an “alternative” but are instead of equal weight and merit to the SAT.

“Capstones are completely student centered, allowing them to showcase their passions, intentions, joys and strengths. You really see kids shine.” -Local district leader

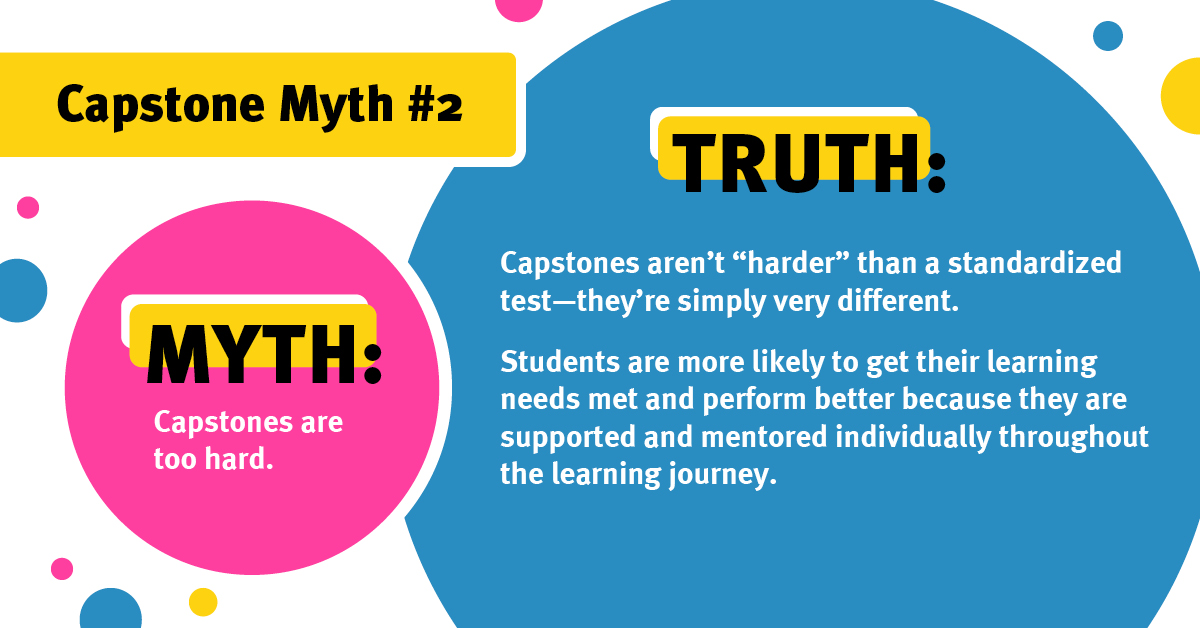

2. “Capstones are too hard.”

Yes, capstones do require preparation, practice, and deep learning to prepare and succeed at a cumulative exam. However, instead of compartmentalizing learning into strict subject areas, capstones give students opportunities to demonstrate a variety of skills, talents, and learnings over the course of a multi-dimensional project assignment on a subject of their choosing. Doing so removes the pressure of a snapshot assessment. In this way, a capstone isn’t “harder” than a traditional test, because the student has been thoroughly prepared and embedded in the learning.

Whether a capstone is “hard” compared to a bubble-test assessment is almost an “apples and oranges” comparison. The difference is, instead of a standardized test as the final demonstration and proof of mastery of key high school competencies, the student presents their semester-long (or multi-year in some cases) research and findings in a capstone presentation in front of their peers, teachers, and parents. The work is indeed challenging, but the student is supported and mentored by their teachers and community leaders throughout the entire learning journey.

“At our school we call capstone presentations ‘celebrations of learning’. It’s a time for students to show who they are culturally, showcase their identity and passions, and feel purposeful.” -Local principal

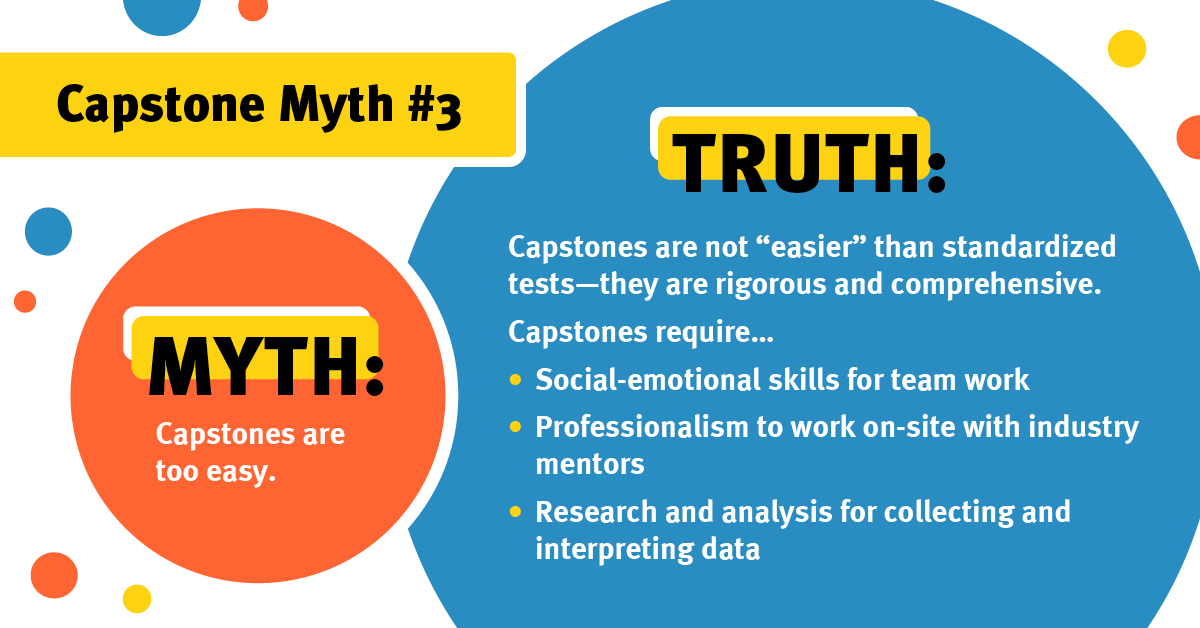

3. “Capstones are too easy.”

Capstones are sometimes misunderstood as busy work or simple community service hours. Rather, they are rigorous, well-rounded academic undertakings.

Capstones require research, community input, analysis, experimentation, public speaking and a formal presentation. Many educators compare the project to a National Science Fair presentation—or better yet, a Master’s dissertation.

The rigor of a capstone comes from its comprehensive nature: the work requires social-emotional skills for team work and community outreach, professionalism and office skills to work on-site with industry mentors, and research and analysis skills for collecting and interpreting data. Capstones are in no way “easier” than standardized testing—they are simply different, and more comprehensive.

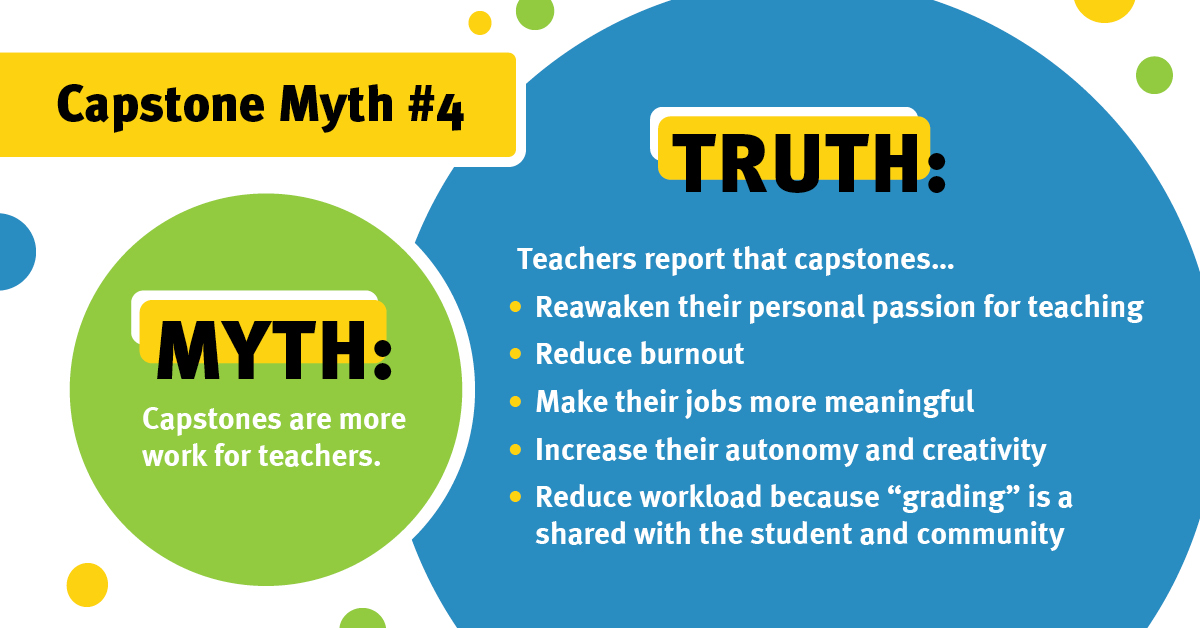

4. “Capstones make more work for the teacher.”

It’s true that capstone projects are highly individualized—meaning the teacher may manage up to 30 different student projects at once. This may seem like a larger workload for the teacher, but when capstones are implemented with adequate support and training, they do not require more effort.

In fact, students are given voice and choice in the process and guide much of the work with teacher and community support. Capstones can engage students as change agents in their communities and can be cultivated in partnership with community members, further lightening the load for educators.

Instead, many teachers report that capstone projects reawaken their personal passion for teaching. Unlike standardized tests which are disconnected from students’ lives, capstones give room for deep connection to students’ curiosities, cultures, interests, and community identity.

Capstones give teachers more autonomy and creativity to rethink assessment for themselves and their students. Instead of being judged solely on annual testing data, capstones give teachers the power and freedom to serve the academic, cultural, and linguistic needs of individual students and their specific communities.

“When I do this kind of work, I’m reminded why I began teaching. School is a place to make the community a better place, where students can truly shine. Capstone curriculum actually makes teaching so much more gratifying and purposeful.” -Local teacher

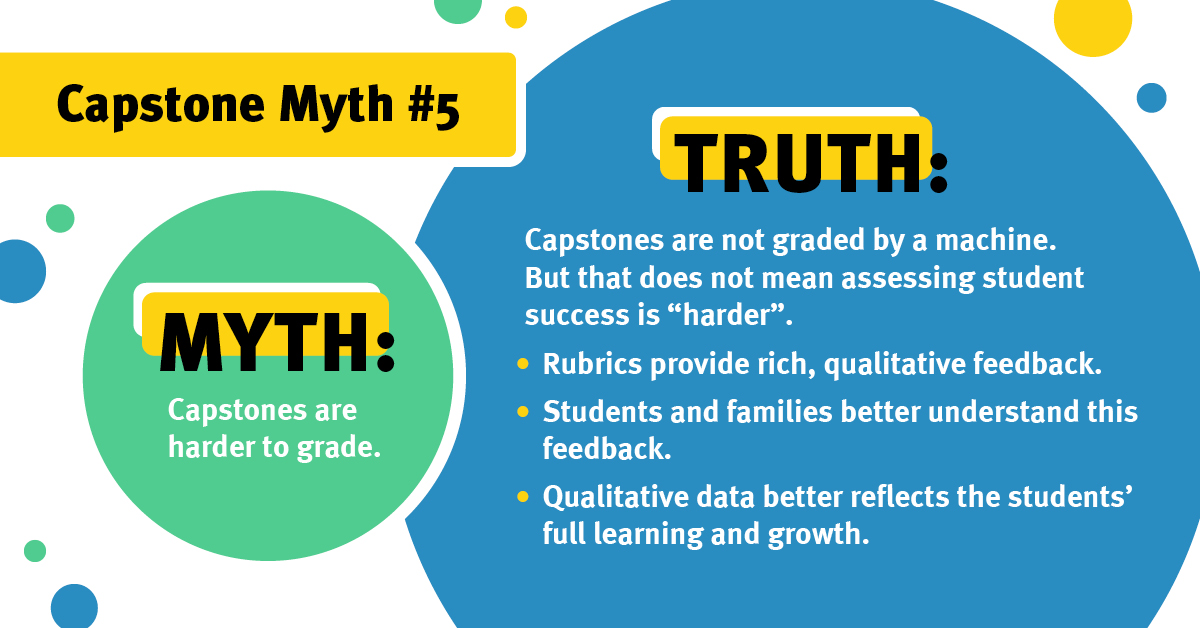

5. “Capstones are hard to grade. Standardized testing is the only way to get quantifiable results.”

While grading capstones is different from processing scantron sheets, it still results in quantifiable data and proof of mastery metrics.

Capstones change the culture of accountability. Because the rubric for demonstrations of learning is in-depth and multi-faceted, capstone data must be processed differently. One argument in favor of standardized testing is that by processing test scores with computers, the results are cheaper and more efficient. In turn, capstone assessments are more meaningful because they are scored by educators and community members, providing students with actionable feedback.

Capstone success can not be processed by a global testing conglomerate. And that is exactly why capstone assessments are a deeper, more community-centered measure of college readiness and subject mastery. This rich, qualitative data is of equal importance and easier to understand by students and families than quantified test reports that do not reflect their full learning and growth experiences in and out of school.

Graduate profiles are an important tool to understand the knowledge, skills, and attributes that young people should graduate with, in addition to key high school competencies. This process requires student, family, educator, employers, and community member input to define the graduate profile. Doing so creates more transparency for student outcomes and learning. Capstones defined by school and community provide a clearer understanding of student learning, community impact, and college readiness than scantron data. This ultimately leads to better performing schools that are in service to the needs of their students and community.

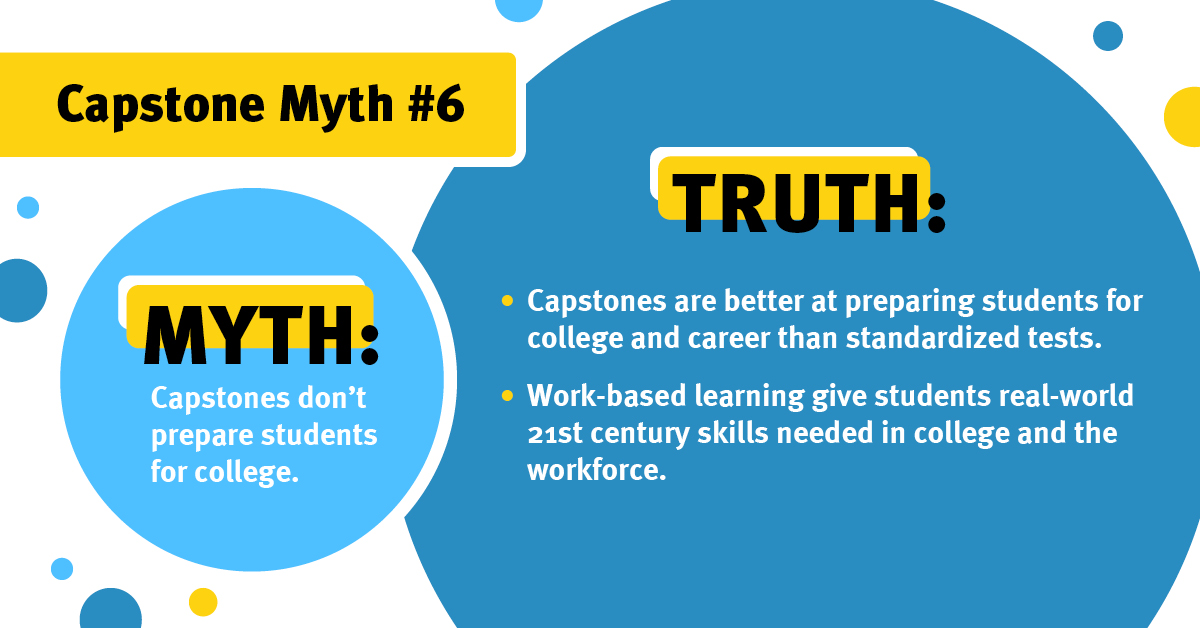

6. “Capstones don’t prepare students for college.”

Capstones are better at preparing students for college than standardized tests. Work-based and project-based learning equip students with the real-world 21st century skills needed in college and the workforce. Several capstone models already in New Mexican schools align capstone work with dual credit offerings, providing students an opportunity to earn college credit in classes that enrich their capstone learning experience.

Where standardized testing data would judge college readiness based on a math and reading score, a capstone would determine readiness based on a full range of soft and hard skills such as: empathy, critical-thinking, resilience, community-mindedness, scientific methodology, and problem-solving.

There is a growing number of colleges and universities that no longer require standardized test scores for admission, given that they are not a direct predictor of success in college. In fact, larger tech companies have also grown wary of hiring Ivy League graduates, many of whom were offered admission based on their standardized test scores. Tech companies have observed these students’ limited readiness to problem solve and work collaboratively.

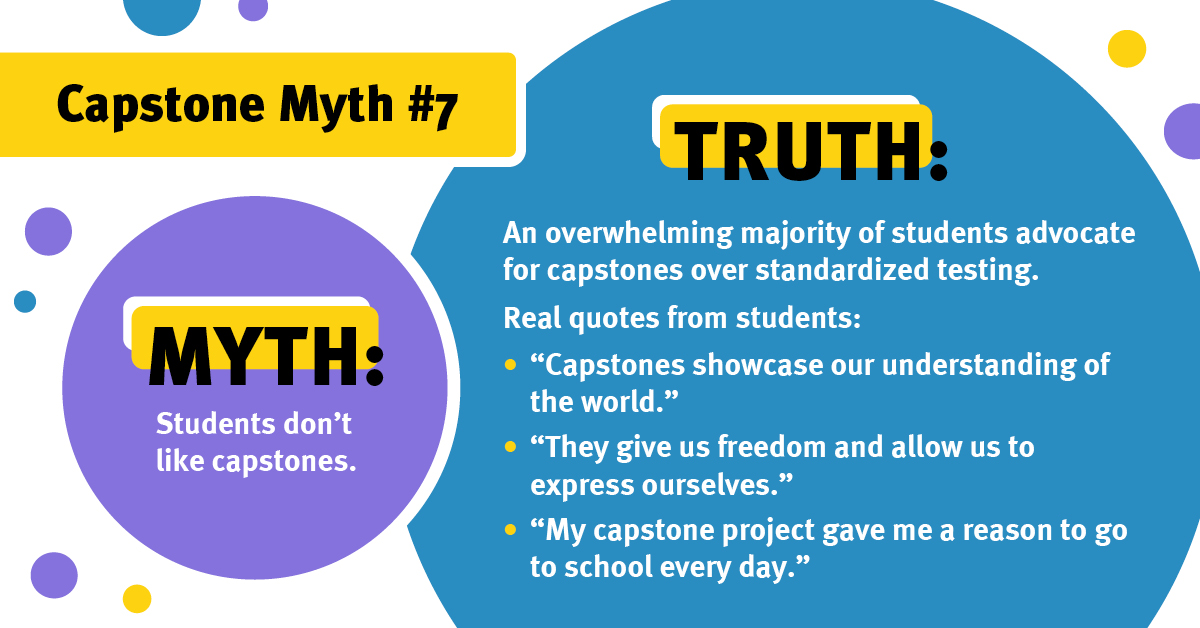

7. “Students don’t like capstones.”

In our work at Future Focused Education, the Leadership High Schools Network, and the New Mexico Graduation Equity Initiative, we see an overwhelming majority of students prefer and advocate for capstones over standardized testing.

The strongest argument is to hear from the students themselves. Here are some quotes from a recent focus group conducted by the New Mexico Graduation Equity Initiative:

“Capstones showcase our understanding of the world, and explore yourself as a person.” “They give us freedom, and allow us to express ourselves and be creative. It helped me feel independent.” “Standardized tests make me so nervous, and don’t accurately show what I’m capable of.” “My capstone project gave me a reason to go to school every day.” “You can pick anything! You get real work experience and it looks great on your resume. You find out what you love doing, and experience is hard to get on your resume in high school otherwise.” “Your community becomes your accountability. That’s way bigger than a test.” -Local students

Recent Articles

Youth civic infrastructure fund 101, the heart of a community: lake arthur municipal schools, eduprising 2024 & the future of education in new mexico.

Great information was provided in assisting me with writing my Capstone document. I am still learning how to write my Capstone paperwork. Sometimes it seems confusing for me. I will get this.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

DigitalCommons@Hamline

A service of the Bush Memorial Library

Home > HSEL > HSEL Student Capstone Projects

School of Education and Leadership Student Capstone Projects

Browse this collection of Capstone Projects submitted by students completing their master’s degrees in the Hamline School of Education and Leadership. Capstones are the culminating degree work and include research that draws from the student's formal study as well as professional and personal development. Submissions include a scholarly written description of the project and may include the project artifact (as a supplemental file).

Capstone Projects are documented in Digital Commons as a degree completion option, starting in 2017.

See also: School of Education Student Capstone Theses and Dissertations

- Master of Arts in Education (MAEd)

- Master of Arts in Education: Natural Science and Environmental Education (MAED: NSEE)

- Master of Arts in English as a Second Language (MAESL)

- Master of Arts in Literacy Education (MALED)

- Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT)

Capstone Projects from 2023 2023

Equity In The Math Classroom How Math Teachers Can Achieve Equity Despite District’s Budget , Tony Edward Kohanek

Implementing Nature-Based Play In Academically Focused Early Childhood Settings , Abbie Krohn

Best Practices: To Supporting and Including SLIFE, Preliterate, Pashtu Students in Secondary, Western, Schools , Claire Madden

Anxiety Disorders In Elementary Students: Interventions For Classroom Use , Jillian Maloney

How does Nutrition, Exercise, Sleep, and Phone Addiction affect Elementary Student Learning? , Madeline (Marston) Ballis

Folktale Friends: An After School Club Curriculum For Building Community And Cultural Competency , Abby Marta

Using Cooperative Groups to Enhance Student Learning in a High School Math Class , Caitlin McCain

Helping Female and Nonbinary Identifying Students Grow Confidence in the Science Classroom , Mari McDonald

English Language Arts Curricular Interventions and Achievement in Advanced First Grade Learners from Underserved Backgrounds , Nicole McKenzie

In what ways are schools, districts and states proactively supporting the mental health of their teachers to reduce teacher turnover and burnout? , Lauren Meyer

Educating Paramedics on the Importance of Postpartum Maternal Health and Related Emergencies , Jeffery Morgan

Increasing High School Students’ Environmental and Scientific Literacies Through Outdoor Investigations , Mack Mowen

Correlations between Outdoor Recreation and Environmental Awareness in Participants with Various Ages, Cultures, and Abilities , Jackie Murphy

Utilizing a School Garden to Promote Ecoliteracy in Elementary Aged Children , Kelsie Murphy

How to Design and Implement a Maker Space in the K-3 Classroom , Elizabeth Nelson

How Adult EFL Teachers Can Effectively Utilize Duolingo in Their Curriculum , Rebecca Nelson

Creating Inclusive Spaces: Using Book Clubs to Increase Diverse Literature in Schools , Clare Ng

A Need For Culturally Relevant Texts To Motivate K-2 Students In Reading , Thi Hoai Anh Nguyen

Role Playing Gamification in the Science Classroom , Timothy Normandt

Elevating Student Voices Through Rigorous Academic Discussion: A Unit of Study for the Middle School English Language Arts Classroom , Emily O’Brien

How Can Guest English-speaking Teachers Best Promote Students’ Identity and Culture in South Korean Schools , Tracy Olsen

Equitable and Inclusive Dance Assessment Resources , Christie Owens

Informal Education Builds Deeper Knowledge And Connections With Elasmobranchs To Develop An Understanding For Environmental Conservation , Lacie Ownbey

An Effective Small Group Reading Intervention Scope And Sequence For Students In Grades Three To Five , Caitlin Phan

Metaphor Matters: Teaching Metaphoric Competence , Linda Pope

Page 3 of 39

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

- Authors/Creators

For Authors/Creators

- Bush Library

- University Archives

- Faculty & Staff Works

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Cool Course: The Capstone Project for the MA in Teaching

- Posted by by Carrie Lynn Hawthorne

- April 22, 2024

“There’s a sense of fear that teachers have about getting their kids to think critically, or really challenge the narratives that are the common tropes that we hear, that aren’t actually true,” says Heather Cheney. This fear can come from trying to find ways to tackle difficult subjects like environmental catastrophes and wars, but it also comes out of the fear of discipline from state laws and local school boards that are increasingly targeting teachers with disciplinary action for, in some cases, teaching about slavery, gender identity, and LBGTQIA+ communities. As Cheney explains it, this fear and the silence it causes can stop teachers from “getting kids to think more critically about history and to think about links between what’s broadly happening in the world and how it affects their day-to-day lives.”

Today, Cheney works to resist this pattern and instead encourage critical thinking in her roles as Core Faculty in Antioch University’s School of Education and Co-Director of the Seattle-based MA in Teaching . And one of the key ways faculty in this program encourage teachers in training to resist the forces of fear and silencing is through the Capstone Project.

The Capstone Project is a student-driven project focusing on a topic of particular interest to students. In the course, which was developed by and is often taught by Caryn Park, faculty encourage student teachers to take what they have learned about teaching and put it all together to act as changemakers in their schools and in their communities.

A Project Combining Math and Storytelling

“Capstone allowed me to merge what I learned in the program with who I want to become as a teacher,” says Cheneka Shannon, an alum of MA in Teaching program. Shannon used her Capstone Project to explore using the power of storytelling to help teach math.

For Shannon, this was a problem that affected her own classroom. She was teaching second graders, and gradually, she realized that she was having as much trouble teaching math as her students were having understanding it.

Shannon decided to experiment with using storytelling to help her students who were struggling with math—this was not only a way to provide them with a very human connection, but it was also an opportunity to use diverse texts to help BIPOC students feel seen. Stories, she reasoned, are how we connect with people, and they’re also a great way to get kids to remember information.

The experiment was broadly a success. Using stories that spoke to students’ identities and interests taught Shannon the impact of putting the student first, not the curriculum. Shannon reflects, “I learned the importance of making sure all scholars, especially those who are marginalized, are prioritized and given space to feel seen and heard in my class.”

When she wrote up her report on the capstone project, she realized that it also started out with once upon a time . It was another powerful story to tell. Explains Shannon, “I wanted to navigate my audience through my journey, starting from who my students were—brilliant, diverse, funny—to how I taught most of the content areas using stories, to being very candid about my struggle with teaching math.”

Teaching as Social Activism

Cheney sees teaching as a form of social activism, and she says that today, we need the people educating our children to be fearless and to stand up for what’s right. That’s why so many of the programs in Antioch’s School of Education center around anti-racism and social justice. As MA in Teaching students come to the end of the one-year program, they have so many ideas around these topics. The Capstone Project offers a perfect chance to dig deeper into a topic and put it into action.

Cheney hopes these projects help teachers realize their own agency and the importance of sharing their gifts with their students. Today, many public schools require teachers to follow pre-written lesson plans that remove much of the creativity of teaching. “Especially as a new teacher, you feel vulnerable and think, I can’t take a risk, I can’t go off-script,” says Cheney. She says that at the start of a teaching career, it can feel overwhelming to jump into such weighty topics. She sees teachers telling themselves, “These things are just too big, and I don’t know enough about them to really dig into these questions.”

But Cheney encourages new teachers to do just that—to dig into the big ideas. And she explains that when they do, not only do their students learn from them, but so do their fellow teachers. As she says, “I think what they gain most from each other is inspiration and courage.”

For Cheney, the best thing about the Capstone Project is, as she puts it, the way that it “connects students’ vision and mission as social justice educators to the real needs of the context that they find themselves in and allows them to go deeper into those particulars.” Each project is different, but they share the characteristic of responding to the social justice needs of students and communities.

Shannon agrees that this is important. She says that as education becomes more politicized, “it has become much harder to safely teach with social justice as the foundation.” The Capstone Project can offer students a key testing ground.

“I think public education can be a space where we can move toward a more just society,” says Cheney. “And I think part of a thriving democracy is having a space where no information is put aside because it might make people in power uncomfortable, critical thinking is embraced, and important questions are asked about whether we’re living up to our best selves.”

Carrie Lynn Hawthorne

Carrie Lynn Hawthorne is a writer and mother from Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in Cultural Daily, The Hennepin Review, The Sunlight Press, and elsewhere. She is an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. For links to her recent publications, visit carrielynnhawthorne.com .

Post navigation

Three Counselor Education and Supervision Students Receive Prestigious NBCC Fellowships

Dissertation Watch: Developing More Equitable and Critically Conscious Organizations

Related posts.

- Undergraduate

Antioch University Launches New Transformative Learning Community Concentration

- April 30, 2020

- 2 minute read

This Online Concentration Allows Students to Design Their Educational Journey in an Intentional Learning Community Antioch University Online and Extended Programs has launched a Transformative Learning Community (TLC) Concentration in the…

Teaching Community Engagement and Encouraging Unapologetic Self-Care

- June 20, 2019

Three years after Yolande “Falami” Devoe earned her master’s in educational leadership from Antioch University Midwest, she suffered two mini-strokes. “I started on a self-care trek as a result of…

Reggio Conference held at AUM

- March 28, 2019

- 1 minute read

The Ohio Voices for Learning: A Reggio Inspired Forum (OVL) held its spring statewide conference at AUM on Saturday, March 16, 2019. OVL is a network of study groups from…

- Author Rights

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- JOLE 2023 Special Issue

- Editorial Staff

- 20th Anniversary Issue

- LEARNING FROM LEADERSHIP CAPSTONE PROJECTS

Andrew J. Wefald, Mac T. Benavides, Aliah K. Mestrovich Seay DOI: 10.12806/V21/I3/R3

Introduction