- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Teach Essay Writing

Last Updated: June 26, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 88,977 times.

Teaching students how to write an essay is a big undertaking, but this is a crucial process for any high school or college student to learn. Start by assigning essays to read and then encourage students to choose an essay topic of their own. Spend class time helping students understand what makes a good essay. Then, use your assignments to guide students through writing their essays.

Choosing Genres and Topics

- Narrative , which is a non-fiction account of a personal experience. This is a good option if you want your students to share a story about something they did, such as a challenge they overcame or a favorite vacation they took. [2] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Expository , which is when you investigate an idea, discuss it at length, and make an argument about it. This might be a good option if you want students to explore a specific concept or a controversial subject. [3] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Descriptive , which is when you describe a person, place, object, emotion, experience, or situation. This can be a good way to allow your students to express themselves creatively through writing. [4] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Argumentative or persuasive essays require students to take a stance on a topic and make an argument to support that stance. This is different from an expository essay in that students won't be discussing a concept at length and then taking a position. The goal of an argumentative essay is to take a position right away and defend it with evidence. [5] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Make sure to select essays that are well-structured and interesting so that your students can model their own essays after these examples. Include essays written by former students, if you can, as well as professionally written essays.

Tip : Readers come in many forms. You can find readers that focus on a specific topic, such as food or pop culture. You can also find reader/handbook combos that will provide general information on writing along with the model essays.

- For example, for each of the essays you assign your students, you could ask them to identify the author's main point or focus, the structure of the essay, the author's use of sources, and the effect of the introduction and conclusion.

- Ask the students to create a reverse outline of the essay to help them understand how to construct a well-written essay. They'll identify the thesis, the main points of the body paragraphs, the supporting evidence, and the concluding statement. Then, they'll present this information in an outline. [8] X Research source

- For example, if you have assigned your students a narrative essay, then encourage them to choose a story that they love to tell or a story they have always wanted to tell but never have.

- If your students are writing argumentative essays, encourage them to select a topic that they feel strongly about or that they'd like to learn more about so that they can voice their opinion.

Explaining the Parts of an Essay

- For example, if you read an essay that begins with an interesting anecdote, highlight that in your class discussion of the essay. Ask students how they could integrate something like that into their own essays and have them write an anecdotal intro in class.

- Or, if you read an essay that starts with a shocking fact or statistic that grabs readers' attention, point this out to your students. Ask them to identify the most shocking fact or statistic related to their essay topic.

- For example, you could provide a few model thesis statements that students can use as templates and then ask them to write a thesis for their topic as an in-class activity or have them post it on an online discussion board.

Tip : Even though the thesis statement is only 1 sentence, this can be the most challenging part of writing an essay for some students. Plan to spend a full class session on writing thesis statements and review the information multiple times as well.

- For example, you could spend a class session going over topic sentences, and then look at how the authors of model essays have used topic sentences to introduce their claims. Then, identify where the author provides support for a claim and how they expand on the source.

- For example, you might direct students to a conclusion in a narrative essay that reflects on the significance of an author's experience. Ask students to write a paragraph where they reflect on the experience they are writing about and turn it in as homework or share it on class discussion board.

- For an expository or argumentative essay, you might show students conclusions that restate the most important aspect of a topic or that offer solutions for the future. Have students write their own conclusions that restate the most important parts of their subject or that outline some possible solutions to the problem.

Guiding Students Through the Writing Process

- Try giving students a sample timeline for how to work on their essays. For example, they might start brainstorming a topic, gathering sources (if required), and taking notes 4 weeks before the paper is due.

- Then, students might begin drafting 2 weeks before the paper is due with a goal of having a full draft 1 week before the essay's due date.

- Students could then plan to start revising their drafts 5 days before the essay is due. This will provide students with ample time to read through their papers a few times and make changes as needed.

- Freewriting, which is when you write freely about anything that comes to mind for a set amount of time, such as 10, 15, or 20 minutes.

- Clustering, which is when you write your topic or topic idea on a piece of paper and then use lines to connect that idea to others.

- Listing, which is when you make a list of any and all ideas related to a topic and ten read through it to find helpful information for your paper.

- Questioning, such as by answering the who, what, when, where, why, and how of their topic.

- Defining terms, such as identifying all of the key terms related to their topic and writing out definitions for each one.

- For example, if your students are writing narrative essays, then it might make the most sense for them to describe the events of a story chronologically.

- If students are writing expository or argumentative essays, then they might need to start by answering the most important questions about their topic and providing background information.

- For a descriptive essay, students might use spatial reasoning to describe something from top to bottom, or organize the descriptive paragraphs into categories for each of the 5 senses, such as sight, sound, smell, taste, and feel.

- For example, if you have just gone over different types of brainstorming strategies, you might ask students to choose 1 that they like and spend 10 minutes developing ideas for their essay.

- Try having students post a weekly response to a writing prompt or question that you assign.

- You may also want to create a separate discussion board where students can post ideas about their essay and get feedback from you and their classmates.

- You could also assign specific parts of the writing process as homework, such as requiring students to hand in a first draft as a homework assignment.

- For example, you might suggest reading the paper backward 1 sentence at a time or reading the paper out loud as a way to identify issues with organization and to weed out minor errors. [21] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

- Try peer-review workshops that ask students to review each others' work. Students can work in pairs or groups during the workshop. Provide them with a worksheet, graphic organizer, or copy of the assignment rubric to guide their peer-review.

Tip : Emphasize the importance of giving yourself at least a few hours away from the essay before you revise it. If possible, it is even better to wait a few days. After this time passes, it is often easier to spot errors and work out better ways of describing things.

Community Q&A

- Students often need to write essays as part of college applications, for assignments in other courses, and when applying for scholarships. Remind your students of all the ways that improving their essay writing skills can benefit them. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/index.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/narrative_essays.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/expository_essays.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/descriptive_essays.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/argumentative_essays.html

- ↑ https://wac.colostate.edu/jbw/v1n2/petrie.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uww.edu/learn/restiptool/improve-student-writing

- ↑ https://twp.duke.edu/sites/twp.duke.edu/files/file-attachments/reverse-outline.original.pdf

- ↑ https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide/brainstorming.shtml

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/faculty-resources/tips-on-teaching-writing/situating-student-writers/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/faculty-resources/tips-on-teaching-writing/in-class-writing-exercises/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Oct 13, 2017

Did this article help you?

Jul 11, 2017

Jan 26, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- All topics A-Z

- Grammar

- Vocabulary

- Speaking

- Reading

- Listening

- Writing

- Pronunciation

- Virtual Classroom

- Worksheets by season

- 600 Creative Writing Prompts

- Warmers, fillers & ice-breakers

- Coloring pages to print

- Flashcards

- Classroom management worksheets

- Emergency worksheets

- Revision worksheets

- Resources we recommend

- Copyright 2007-2021 пїЅ

- Submit a worksheet

- Mobile version

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

How to Teach Creative Writing | 7 Steps to Get Students Wordsmithing

“I don’t have any ideas!”

“I can’t think of anything!”

While we see creative writing as a world of limitless imagination, our students often see an overwhelming desert of “no idea.”

But when you teach creative writing effectively, you’ll notice that every student is brimming over with ideas that just have to get out.

So what does teaching creative writing effectively look like?

We’ve outlined a seven-step method that will scaffold your students through each phase of the creative process from idea generation through to final edits.

7. Create inspiring and original prompts

Use the following formats to generate prompts that get students inspired:

- personal memories (“Write about a person who taught you an important lesson”)

- imaginative scenarios

- prompts based on a familiar mentor text (e.g. “Write an alternative ending to your favorite book”). These are especially useful for giving struggling students an easy starting point.

- lead-in sentences (“I looked in the mirror and I couldn’t believe my eyes. Somehow overnight I…”).

- fascinating or thought-provoking images with a directive (“Who do you think lives in this mountain cabin? Tell their story”).

Don’t have the time or stuck for ideas? Check out our list of 100 student writing prompts

6. unpack the prompts together.

Explicitly teach your students how to dig deeper into the prompt for engaging and original ideas.

Probing questions are an effective strategy for digging into a prompt. Take this one for example:

“I looked in the mirror and I couldn’t believe my eyes. Somehow overnight I…”

Ask “What questions need answering here?” The first thing students will want to know is:

What happened overnight?

No doubt they’ll be able to come up with plenty of zany answers to that question, but there’s another one they could ask to make things much more interesting:

Who might “I” be?

In this way, you subtly push students to go beyond the obvious and into more original and thoughtful territory. It’s even more useful with a deep prompt:

“Write a story where the main character starts to question something they’ve always believed.”

Here students could ask:

- What sorts of beliefs do people take for granted?

- What might make us question those beliefs?

- What happens when we question something we’ve always thought is true?

- How do we feel when we discover that something isn’t true?

Try splitting students into groups, having each group come up with probing questions for a prompt, and then discussing potential “answers” to these questions as a class.

The most important lesson at this point should be that good ideas take time to generate. So don’t rush this step!

5. Warm-up for writing

A quick warm-up activity will:

- allow students to see what their discussed ideas look like on paper

- help fix the “I don’t know how to start” problem

- warm up writing muscles quite literally (especially important for young learners who are still developing handwriting and fine motor skills).

Freewriting is a particularly effective warm-up. Give students 5–10 minutes to “dump” all their ideas for a prompt onto the page for without worrying about structure, spelling, or grammar.

After about five minutes you’ll notice them starting to get into the groove, and when you call time, they’ll have a better idea of what captures their interest.

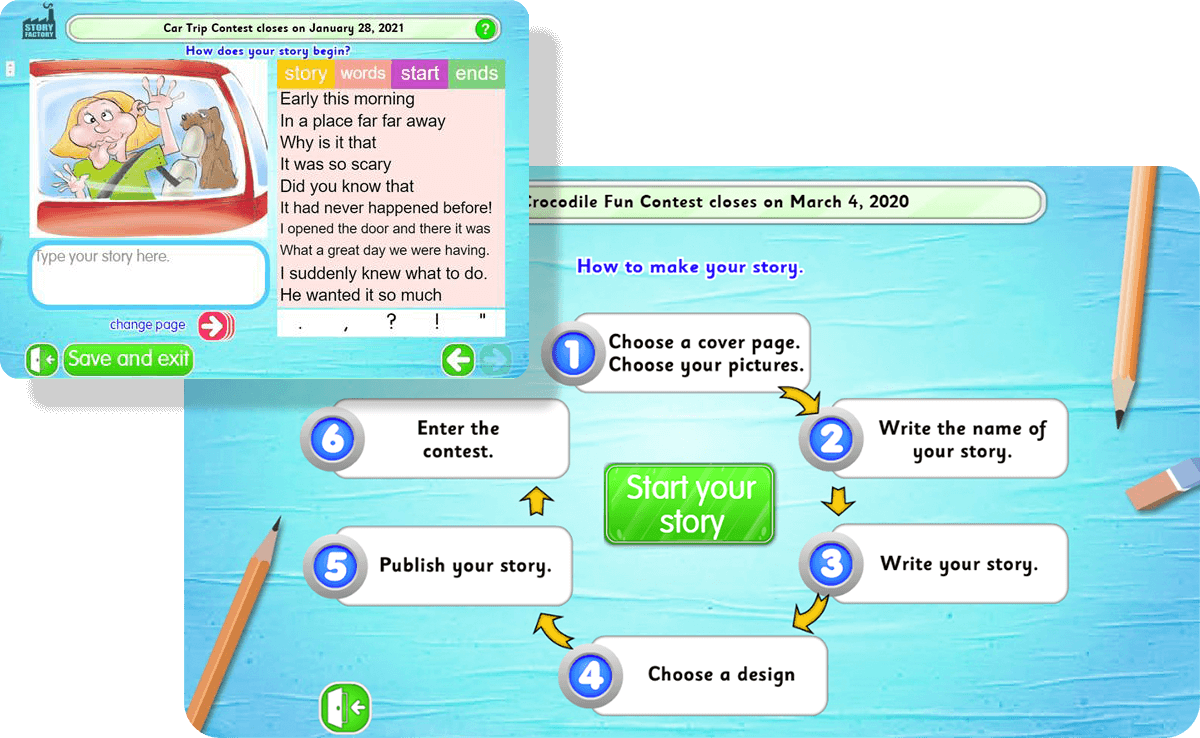

Did you know? The Story Factory in Reading Eggs allows your students to write and publish their own storybooks using an easy step-by-step guide.

4. Start planning

Now it’s time for students to piece all these raw ideas together and generate a plan. This will synthesize disjointed ideas and give them a roadmap for the writing process.

Note: at this stage your strong writers might be more than ready to get started on a creative piece. If so, let them go for it – use planning for students who are still puzzling things out.

Here are four ideas for planning:

Graphic organisers

A graphic organiser will allow your students to plan out the overall structure of their writing. They’re also particularly useful in “chunking” the writing process, so students don’t see it as one big wall of text.

Storyboards and illustrations

These will engage your artistically-minded students and give greater depth to settings and characters. Just make sure that drawing doesn’t overshadow the writing process.

Voice recordings

If you have students who are hesitant to commit words to paper, tell them to think out loud and record it on their device. Often they’ll be surprised at how well their spoken words translate to the page.

Write a blurb

This takes a bit more explicit teaching, but it gets students to concisely summarize all their main ideas (without giving away spoilers). Look at some blurbs on the back of published books before getting them to write their own. Afterward they could test it out on a friend – based on the blurb, would they borrow it from the library?

3. Produce rough drafts

Warmed up and with a plan at the ready, your students are now ready to start wordsmithing. But before they start on a draft, remind them of what a draft is supposed to be:

- a work in progress.

Remind them that if they wait for the perfect words to come, they’ll end up with blank pages .

Instead, it’s time to take some writing risks and get messy. Encourage this by:

- demonstrating the writing process to students yourself

- taking the focus off spelling and grammar (during the drafting stage)

- providing meaningful and in-depth feedback (using words, not ticks!).

Reading Eggs also gives you access to an ever-expanding collection of over 3,500 online books!

2. share drafts for peer feedback.

Don’t saddle yourself with 30 drafts for marking. Peer assessment is a better (and less exhausting) way to ensure everyone receives the feedback they need.

Why? Because for something as personal as creative writing, feedback often translates better when it’s in the familiar and friendly language that only a peer can produce. Looking at each other’s work will also give students more ideas about how they can improve their own.

Scaffold peer feedback to ensure it’s constructive. The following methods work well:

Student rubrics

A simple rubric allows students to deliver more in-depth feedback than “It was pretty good.” The criteria will depend on what you are ultimately looking for, but students could assess each other’s:

- use of language.

Whatever you opt for, just make sure the language you use in the rubric is student-friendly.

Two positives and a focus area

Have students identify two things their peer did well, and one area that they could focus on further, then turn this into written feedback. Model the process for creating specific comments so you get something more constructive than “It was pretty good.” It helps to use stems such as:

I really liked this character because…

I found this idea interesting because it made me think…

I was a bit confused by…

I wonder why you… Maybe you could… instead.

1. The editing stage

Now that students have a draft and feedback, here’s where we teachers often tell them to “go over it” or “give it some final touches.”

But our students don’t always know how to edit.

Scaffold the process with questions that encourage students to think critically about their writing, such as:

- Are there any parts that would be confusing if I wasn’t there to explain them?

- Are there any parts that seem irrelevant to the rest?

- Which parts am I most uncertain about?

- Does the whole thing flow together, or are there parts that seem out of place?

- Are there places where I could have used a better word?

- Are there any grammatical or spelling errors I notice?

Key to this process is getting students to read their creative writing from start to finish .

Important note: if your students are using a word processor, show them where the spell-check is and how to use it. Sounds obvious, but in the age of autocorrect, many students simply don’t know.

A final word on teaching creative writing

Remember that the best writers write regularly.

Incorporate them into your lessons as often as possible, and soon enough, you’ll have just as much fun marking your students’ creative writing as they do producing it.

Need more help supporting your students’ writing?

Read up on how to get reluctant writers writing , strategies for supporting struggling secondary writers , or check out our huge list of writing prompts for kids .

Watch your students get excited about writing and publishing their own storybooks in the Story Factory

You might like....

Essay Writing: A complete guide for students and teachers

P LANNING, PARAGRAPHING AND POLISHING: FINE-TUNING THE PERFECT ESSAY

Essay writing is an essential skill for every student. Whether writing a particular academic essay (such as persuasive, narrative, descriptive, or expository) or a timed exam essay, the key to getting good at writing is to write. Creating opportunities for our students to engage in extended writing activities will go a long way to helping them improve their skills as scribes.

But, putting the hours in alone will not be enough to attain the highest levels in essay writing. Practice must be meaningful. Once students have a broad overview of how to structure the various types of essays, they are ready to narrow in on the minor details that will enable them to fine-tune their work as a lean vehicle of their thoughts and ideas.

In this article, we will drill down to some aspects that will assist students in taking their essay writing skills up a notch. Many ideas and activities can be integrated into broader lesson plans based on essay writing. Often, though, they will work effectively in isolation – just as athletes isolate physical movements to drill that are relevant to their sport. When these movements become second nature, they can be repeated naturally in the context of the game or in our case, the writing of the essay.

THE ULTIMATE NONFICTION WRITING TEACHING RESOURCE

- 270 pages of the most effective teaching strategies

- 50+ digital tools ready right out of the box

- 75 editable resources for student differentiation

- Loads of tricks and tips to add to your teaching tool bag

- All explanations are reinforced with concrete examples.

- Links to high-quality video tutorials

- Clear objectives easy to match to the demands of your curriculum

Planning an essay

The Boys Scouts’ motto is famously ‘Be Prepared’. It’s a solid motto that can be applied to most aspects of life; essay writing is no different. Given the purpose of an essay is generally to present a logical and reasoned argument, investing time in organising arguments, ideas, and structure would seem to be time well spent.

Given that essays can take a wide range of forms and that we all have our own individual approaches to writing, it stands to reason that there will be no single best approach to the planning stage of essay writing. That said, there are several helpful hints and techniques we can share with our students to help them wrestle their ideas into a writable form. Let’s take a look at a few of the best of these:

BREAK THE QUESTION DOWN: UNDERSTAND YOUR ESSAY TOPIC.

Whether students are tackling an assignment that you have set for them in class or responding to an essay prompt in an exam situation, they should get into the habit of analyzing the nature of the task. To do this, they should unravel the question’s meaning or prompt. Students can practice this in class by responding to various essay titles, questions, and prompts, thereby gaining valuable experience breaking these down.

Have students work in groups to underline and dissect the keywords and phrases and discuss what exactly is being asked of them in the task. Are they being asked to discuss, describe, persuade, or explain? Understanding the exact nature of the task is crucial before going any further in the planning process, never mind the writing process .

BRAINSTORM AND MIND MAP WHAT YOU KNOW:

Once students have understood what the essay task asks them, they should consider what they know about the topic and, often, how they feel about it. When teaching essay writing, we so often emphasize that it is about expressing our opinions on things, but for our younger students what they think about something isn’t always obvious, even to themselves.

Brainstorming and mind-mapping what they know about a topic offers them an opportunity to uncover not just what they already know about a topic, but also gives them a chance to reveal to themselves what they think about the topic. This will help guide them in structuring their research and, later, the essay they will write . When writing an essay in an exam context, this may be the only ‘research’ the student can undertake before the writing, so practicing this will be even more important.

RESEARCH YOUR ESSAY

The previous step above should reveal to students the general direction their research will take. With the ubiquitousness of the internet, gone are the days of students relying on a single well-thumbed encyclopaedia from the school library as their sole authoritative source in their essay. If anything, the real problem for our students today is narrowing down their sources to a manageable number. Students should use the information from the previous step to help here. At this stage, it is important that they:

● Ensure the research material is directly relevant to the essay task

● Record in detail the sources of the information that they will use in their essay

● Engage with the material personally by asking questions and challenging their own biases

● Identify the key points that will be made in their essay

● Group ideas, counterarguments, and opinions together

● Identify the overarching argument they will make in their own essay.

Once these stages have been completed the student is ready to organise their points into a logical order.

WRITING YOUR ESSAY

There are a number of ways for students to organize their points in preparation for writing. They can use graphic organizers , post-it notes, or any number of available writing apps. The important thing for them to consider here is that their points should follow a logical progression. This progression of their argument will be expressed in the form of body paragraphs that will inform the structure of their finished essay.

The number of paragraphs contained in an essay will depend on a number of factors such as word limits, time limits, the complexity of the question etc. Regardless of the essay’s length, students should ensure their essay follows the Rule of Three in that every essay they write contains an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Generally speaking, essay paragraphs will focus on one main idea that is usually expressed in a topic sentence that is followed by a series of supporting sentences that bolster that main idea. The first and final sentences are of the most significance here with the first sentence of a paragraph making the point to the reader and the final sentence of the paragraph making the overall relevance to the essay’s argument crystal clear.

Though students will most likely be familiar with the broad generic structure of essays, it is worth investing time to ensure they have a clear conception of how each part of the essay works, that is, of the exact nature of the task it performs. Let’s review:

Common Essay Structure

Introduction: Provides the reader with context for the essay. It states the broad argument that the essay will make and informs the reader of the writer’s general perspective and approach to the question.

Body Paragraphs: These are the ‘meat’ of the essay and lay out the argument stated in the introduction point by point with supporting evidence.

Conclusion: Usually, the conclusion will restate the central argument while summarising the essay’s main supporting reasons before linking everything back to the original question.

ESSAY WRITING PARAGRAPH WRITING TIPS

● Each paragraph should focus on a single main idea

● Paragraphs should follow a logical sequence; students should group similar ideas together to avoid incoherence

● Paragraphs should be denoted consistently; students should choose either to indent or skip a line

● Transition words and phrases such as alternatively , consequently , in contrast should be used to give flow and provide a bridge between paragraphs.

HOW TO EDIT AN ESSAY

Students shouldn’t expect their essays to emerge from the writing process perfectly formed. Except in exam situations and the like, thorough editing is an essential aspect in the writing process.

Often, students struggle with this aspect of the process the most. After spending hours of effort on planning, research, and writing the first draft, students can be reluctant to go back over the same terrain they have so recently travelled. It is important at this point to give them some helpful guidelines to help them to know what to look out for. The following tips will provide just such help:

One Piece at a Time: There is a lot to look out for in the editing process and often students overlook aspects as they try to juggle too many balls during the process. One effective strategy to combat this is for students to perform a number of rounds of editing with each focusing on a different aspect. For example, the first round could focus on content, the second round on looking out for word repetition (use a thesaurus to help here), with the third attending to spelling and grammar.

Sum It Up: When reviewing the paragraphs they have written, a good starting point is for students to read each paragraph and attempt to sum up its main point in a single line. If this is not possible, their readers will most likely have difficulty following their train of thought too and the paragraph needs to be overhauled.

Let It Breathe: When possible, encourage students to allow some time for their essay to ‘breathe’ before returning to it for editing purposes. This may require some skilful time management on the part of the student, for example, a student rush-writing the night before the deadline does not lend itself to effective editing. Fresh eyes are one of the sharpest tools in the writer’s toolbox.

Read It Aloud: This time-tested editing method is a great way for students to identify mistakes and typos in their work. We tend to read things more slowly when reading aloud giving us the time to spot errors. Also, when we read silently our minds can often fill in the gaps or gloss over the mistakes that will become apparent when we read out loud.

Phone a Friend: Peer editing is another great way to identify errors that our brains may miss when reading our own work. Encourage students to partner up for a little ‘you scratch my back, I scratch yours’.

Use Tech Tools: We need to ensure our students have the mental tools to edit their own work and for this they will need a good grasp of English grammar and punctuation. However, there are also a wealth of tech tools such as spellcheck and grammar checks that can offer a great once-over option to catch anything students may have missed in earlier editing rounds.

Putting the Jewels on Display: While some struggle to edit, others struggle to let go. There comes a point when it is time for students to release their work to the reader. They must learn to relinquish control after the creation is complete. This will be much easier to achieve if the student feels that they have done everything in their control to ensure their essay is representative of the best of their abilities and if they have followed the advice here, they should be confident they have done so.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

ESSAY WRITING video tutorials

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Four Strategies for Effective Writing Instruction

- Share article

(This is the first post in a two-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is the single most effective instructional strategy you have used to teach writing?

Teaching and learning good writing can be a challenge to educators and students alike.

The topic is no stranger to this column—you can see many previous related posts at Writing Instruction .

But I don’t think any of us can get too much good instructional advice in this area.

Today, Jenny Vo, Michele Morgan, and Joy Hamm share wisdom gained from their teaching experience.

Before I turn over the column to them, though, I’d like to share my favorite tool(s).

Graphic organizers, including writing frames (which are basically more expansive sentence starters) and writing structures (which function more as guides and less as “fill-in-the-blanks”) are critical elements of my writing instruction.

You can see an example of how I incorporate them in my seven-week story-writing unit and in the adaptations I made in it for concurrent teaching.

You might also be interested in The Best Scaffolded Writing Frames For Students .

Now, to today’s guests:

‘Shared Writing’

Jenny Vo earned her B.A. in English from Rice University and her M.Ed. in educational leadership from Lamar University. She has worked with English-learners during all of her 24 years in education and is currently an ESL ISST in Katy ISD in Katy, Texas. Jenny is the president-elect of TexTESOL IV and works to advocate for all ELs:

The single most effective instructional strategy that I have used to teach writing is shared writing. Shared writing is when the teacher and students write collaboratively. In shared writing, the teacher is the primary holder of the pen, even though the process is a collaborative one. The teacher serves as the scribe, while also questioning and prompting the students.

The students engage in discussions with the teacher and their peers on what should be included in the text. Shared writing can be done with the whole class or as a small-group activity.

There are two reasons why I love using shared writing. One, it is a great opportunity for the teacher to model the structures and functions of different types of writing while also weaving in lessons on spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

It is a perfect activity to do at the beginning of the unit for a new genre. Use shared writing to introduce the students to the purpose of the genre. Model the writing process from beginning to end, taking the students from idea generation to planning to drafting to revising to publishing. As you are writing, make sure you refrain from making errors, as you want your finished product to serve as a high-quality model for the students to refer back to as they write independently.

Another reason why I love using shared writing is that it connects the writing process with oral language. As the students co-construct the writing piece with the teacher, they are orally expressing their ideas and listening to the ideas of their classmates. It gives them the opportunity to practice rehearsing what they are going to say before it is written down on paper. Shared writing gives the teacher many opportunities to encourage their quieter or more reluctant students to engage in the discussion with the types of questions the teacher asks.

Writing well is a skill that is developed over time with much practice. Shared writing allows students to engage in the writing process while observing the construction of a high-quality sample. It is a very effective instructional strategy used to teach writing.

‘Four Square’

Michele Morgan has been writing IEPs and behavior plans to help students be more successful for 17 years. She is a national-board-certified teacher, Utah Teacher Fellow with Hope Street Group, and a special education elementary new-teacher specialist with the Granite school district. Follow her @MicheleTMorgan1:

For many students, writing is the most dreaded part of the school day. Writing involves many complex processes that students have to engage in before they produce a product—they must determine what they will write about, they must organize their thoughts into a logical sequence, and they must do the actual writing, whether on a computer or by hand. Still they are not done—they must edit their writing and revise mistakes. With all of that, it’s no wonder that students struggle with writing assignments.

In my years working with elementary special education students, I have found that writing is the most difficult subject to teach. Not only do my students struggle with the writing process, but they often have the added difficulties of not knowing how to spell words and not understanding how to use punctuation correctly. That is why the single most effective strategy I use when teaching writing is the Four Square graphic organizer.

The Four Square instructional strategy was developed in 1999 by Judith S. Gould and Evan Jay Gould. When I first started teaching, a colleague allowed me to borrow the Goulds’ book about using the Four Square method, and I have used it ever since. The Four Square is a graphic organizer that students can make themselves when given a blank sheet of paper. They fold it into four squares and draw a box in the middle of the page. The genius of this instructional strategy is that it can be used by any student, in any grade level, for any writing assignment. These are some of the ways I have used this strategy successfully with my students:

* Writing sentences: Students can write the topic for the sentence in the middle box, and in each square, they can draw pictures of details they want to add to their writing.

* Writing paragraphs: Students write the topic sentence in the middle box. They write a sentence containing a supporting detail in three of the squares and they write a concluding sentence in the last square.

* Writing short essays: Students write what information goes in the topic paragraph in the middle box, then list details to include in supporting paragraphs in the squares.

When I gave students writing assignments, the first thing I had them do was create a Four Square. We did this so often that it became automatic. After filling in the Four Square, they wrote rough drafts by copying their work off of the graphic organizer and into the correct format, either on lined paper or in a Word document. This worked for all of my special education students!

I was able to modify tasks using the Four Square so that all of my students could participate, regardless of their disabilities. Even if they did not know what to write about, they knew how to start the assignment (which is often the hardest part of getting it done!) and they grew to be more confident in their writing abilities.

In addition, when it was time to take the high-stakes state writing tests at the end of the year, this was a strategy my students could use to help them do well on the tests. I was able to give them a sheet of blank paper, and they knew what to do with it. I have used many different curriculum materials and programs to teach writing in the last 16 years, but the Four Square is the one strategy that I have used with every writing assignment, no matter the grade level, because it is so effective.

‘Swift Structures’

Joy Hamm has taught 11 years in a variety of English-language settings, ranging from kindergarten to adult learners. The last few years working with middle and high school Newcomers and completing her M.Ed in TESOL have fostered stronger advocacy in her district and beyond:

A majority of secondary content assessments include open-ended essay questions. Many students falter (not just ELs) because they are unaware of how to quickly organize their thoughts into a cohesive argument. In fact, the WIDA CAN DO Descriptors list level 5 writing proficiency as “organizing details logically and cohesively.” Thus, the most effective cross-curricular secondary writing strategy I use with my intermediate LTELs (long-term English-learners) is what I call “Swift Structures.” This term simply means reading a prompt across any content area and quickly jotting down an outline to organize a strong response.

To implement Swift Structures, begin by displaying a prompt and modeling how to swiftly create a bubble map or outline beginning with a thesis/opinion, then connecting the three main topics, which are each supported by at least three details. Emphasize this is NOT the time for complete sentences, just bulleted words or phrases.

Once the outline is completed, show your ELs how easy it is to plug in transitions, expand the bullets into detailed sentences, and add a brief introduction and conclusion. After modeling and guided practice, set a 5-10 minute timer and have students practice independently. Swift Structures is one of my weekly bell ringers, so students build confidence and skill over time. It is best to start with easy prompts where students have preformed opinions and knowledge in order to focus their attention on the thesis-topics-supporting-details outline, not struggling with the rigor of a content prompt.

Here is one easy prompt example: “Should students be allowed to use their cellphones in class?”

Swift Structure outline:

Thesis - Students should be allowed to use cellphones because (1) higher engagement (2) learning tools/apps (3) gain 21st-century skills

Topic 1. Cellphones create higher engagement in students...

Details A. interactive (Flipgrid, Kahoot)

B. less tempted by distractions

C. teaches responsibility

Topic 2. Furthermore,...access to learning tools...

A. Google Translate description

B. language practice (Duolingo)

C. content tutorials (Kahn Academy)

Topic 3. In addition,...practice 21st-century skills…

Details A. prep for workforce

B. access to information

C. time-management support

This bare-bones outline is like the frame of a house. Get the structure right, and it’s easier to fill in the interior decorating (style, grammar), roof (introduction) and driveway (conclusion). Without the frame, the roof and walls will fall apart, and the reader is left confused by circuitous rubble.

Once LTELs have mastered creating simple Swift Structures in less than 10 minutes, it is time to introduce complex questions similar to prompts found on content assessments or essays. Students need to gain assurance that they can quickly and logically explain and justify their opinions on multiple content essays without freezing under pressure.

Thanks to Jenny, Michele, and Joy for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Utility Menu

- Writing Center

- Writing Program

- Guides to Teaching Writing

The Harvard Writing Project publishes resource guides for faculty and teaching fellows that help them integrate writing into their courses more effectively — for example, by providing ideas about effective assignment design and strategies for responding to student writing.

A list of current HWP publications for faculty and teaching fellows is provided below. Most of the publications are available for download as PDF files. If you would like to be added to the Bulletin mailing list or to receive printed copies of any of the guides listed below, email James Herron at [email protected].

HARVARD WRITING PROJECT BRIEF GUIDES TO TEACHING WRITING

OTHER HARVARD WRITING PROJECT TEACHING GUIDES

- Pedagogy Workshops

- Advice for Teaching Fellows

- HarvardWrites Instructor Toolkit

- Additional Resources for Teaching Fellows

- How to Teach Essay Writing

Don't just throw your homeschooled-student intoformal essay crafting. Focus on sentence structure and basic paragraph composition before movingto more complicated formal essay composition.

Are you a competent essay writer? Even if you know how to write an essay , chances are you are dreading the coming years of teaching homeschool writing just as much as your novice writer could be dreading learning how to write . Writing comes naturally for very few, but most view writing as an insurmountable abstract mountain. The Write Foundation writing curriculum is a divide and conquer method of teaching writing. Focusing on small portions of writing paragraphs and later five-paragraph college level essays, eventually you and your students will be able to use all the necessary writing skills to easily compose wonderfully crafted formal essays .

Start with a good foundation

That is, of course, what The Write Foundation teaches. Don’t just throw your homeschooled-child into the middle of essay crafting. Focus on sentence structure and basic paragraph composition before moving to more complicated formal essay composition . Learn to write essays one bite at a time. This helps students develop writing skills by using writing tools which helps them gain confidence and enables parents who are insecure about their own writing skills learn with their students.

Hold their hand as much as they need you hold their hand.

An abstract assignment with limited instructions can appear quite daunting to a reluctant, struggling, or new writer; tiny decisions can become writing blocks in a new writer’s mind.

Share the experience with your homeschooler. Discuss writing blocks and ways to overcome them. Discuss the planning process and experience how it helps flesh out an essay. Walk them through each lesson making sure they complete each step successfully before attempting to move on in the writing process. Working side by side with your student also helps you become a better instructor by solidifying the lesson for yourself. As students gain confidence with their new skills they will need your help less and less so they will shoo you away as they learn writing is much easier using the complete writing process.

Use concrete assignments

Creative writing is very subjective, and it is also very abstract for a new writer. You need a writing curriculum which focuses on concrete assignments and provides a variety of writing topics that fit the type of writing being taught in that assignment. Give your students a structure to work into a paragraph using their creative information. Leaving several factors to the unknown, such as type of writing, structure, and so on, leaves more decisions that the novice writer is not ready to determine. An abstract assignment with limited instructions can appear quite daunting to a reluctant, struggling, or just new writer; tiny decisions can become writing blocks in a new writer’s mind. Even experienced writers face writer’s block. Students need to be given tools and taught skills that overcome “But, what do I write about?”

Know your audience

Let your child select from a list of possible writing topics that may be interesting to them. Your child may enjoy the experience more if he is writing about his favorite pastime instead of writing about your favorite pastime. Choosing topics about things that directly influence your child, such as different views about their favorite sport, the influence of network TV or political topics that hit close to home may open the doors for lively discussion and insight into your child’s mind.

Writing is a necessary life skill. When teaching writing remember you are not alone. If you are worried about teaching formal writing to your homeschooler, use the support system of The Write Foundation for any questions you may have through the process, and know that you are not alone. Look into a homeschool writing co-op in your area to lighten the burden and give new perspective on your child’s essay writing development. Use The Write Foundation and use a proven writing system.

Questions or Comments?

Recent articles.

- Correcting Run-on Sentences

- How Does Skipping the Writing Process Affect your Writing?

- Graduating Homeschooling

- Is My Child Ready for Formal Writing?

- Teaching Spelling

- Evaluating Homeschool Writing Curriculums

- Why Most Writing Curriculums Fail (and How to Make Sure your Homeschooler Doesn't!)

- Top Five Reasons Students Hate to Write (and How You can Help!)

- College Preparation for Homeschooled Students

H e is like a man building a house, who dug deep and laid the foundation on the rock. Luke 6:48

View, Print, and Practice the Sample Lessons

(We're here to help you teach!)

Now Available!

Free Reading Lists Get your copy today!

Have a struggling writer? Maybe he hates writing? Does your student just need to learn how to write? Long for teacher-friendly lesson plans you can quickly prepare and teach? Desire a writing curriculum your children will enjoy while learning creatively?

- Complete Lesson Plans

- Free Assessment Tests

- Free Reading Lists

- Organization for Writing

- Checklists & Guidelines

- Brainstorm & Outline Forms

Open doors to writing success!

Contact Rebecca . Rebecca Celsor will answer your questions regarding how to easily teach your child to write.

" My 14 yr old is Autistic. This is the first time EVER that he is understanding composition AND enjoying it. He looks forward to it. He loves the mindbenders, and all the "silliness" that goes into the composition exercises. He actually wanted to know if he could do more sentences!!! This NEVER happens with him. Composition has been so difficult for him. Your program is such a difference. We could never afford the big, expensive programs, and I don't think they would have worked for him. "

- Course Selection Assistance

- Suggested Age Levels for Homeschool Writing

- Entry Level I - Prepare to Write

- Entry Level II - Creating Sentences

- Level 1 - Sentence to Paragraph

- Level 2 - Paragraph

- Level 3 - Essay

- Free Curriculum Writing Samples

- Example Teaching Videos

- Online Grading Service

- Writing Skills Reference Folder

- How to Present a Lesson

- Grading Writing

- Key Points for Grading Writing

- MindBenders®

- Order Curriculum Packages

- Order Worksheets Only

- Refund/Return Policy

- Selecting Home School Curriculum

- Writing Preparation

- Writing Development

- High School and Beyond

- Homeschool Co-ops

- Homeschool How To

- The Story Behind TWF

- Why Another Writing Curriculum?

- Copyright Information

He is like a man building a house, who dug deep and laid the foundation on the rock . Luke 6:48

Dedicated to equipping God's children with the ability to communicate His Truth to the world.

- Teaching Tools

- Curriculum Ordering

- homeschool writing curriculum

- home school writing samples

- Mind Benders®

- Online Grading

Copyright © 2021 TheWriteFoundation.org

web site design - evolvethebrand.com

- TARR’S TOOLBOX

Email Address

10 creative approaches for developing essay-writing skills

Overview: 10 tips for improving essay writing.

The knack of writing a good essay in a subject like history is a skill which is a challenge to acquire for many students, but immensely rewarding and useful. The ability to carry a reader along with a well-crafted argument is no easy feat, since it involves carefully synthesising the creative arts of the storyteller with the scientific rigour of the evidence-driven empiricist.

With this in mind, it is not enough to simply take in an essay, mark it and provide feedback, and then hurry on to the next lesson or activity. Much better is to take in a first draft of the essay, involve the students in some reflection and redrafting, and then take it in for final marking so that the advice is immediately being put into effect rather than going stale whilst the class awaits the next essay assignment several weeks later.

Listed below are a few activities that can be used to help students improve their essay-writing skills after their initial draft of work has been completed.

To accompany this post, you may wish to read these other entries on Tarr’s Toolbox:

- Compare first paragraph of several books to analyse stylistic techniques

- Develop links between factors using a “Connection Web” template

- “Linkage Bingo” to summarise and connect key factors

- Using Hexagon Learning for categorisation, linkage and prioritisation

- Visual essay-writing: cartoons, sticky-notes and plenty of collaboration!

- Use the “Keyword Checker” to ensure student essays cover the essentials

- Rubric Grids: Essay Marking Made Easy!

- Using the “Battleships” format to Teach Historical Interpretations

- Sticky-notes and project nests: collaborate, collate, categorise, connect

- Connecting Factors with “Paper People” display projects

Sample Exercises

1. analysis skills.

- “The Skeleton”

▪ Produce an essay plan which contains merely the first sentence of each paragraph. Leave space underneath each sentence so it can be completed.

▪ Pass your essay to a partner. Their job is to explain the points you make using evidence.

▪ Finally, take your essay back (or pass it to a third person) to write a conclusion.

- “Objection!”

▪ Take your own (or someone else’s) completed essay. Read out just the first sentence of each paragraph to a partner or to the class. If at any point anyone in the class thinks that an opening sentence is a narrative statement of fact rather than an analytical argument they should say “objection” and explain why. Develop your opening statements until the class is happy with the finished piece.

- “Flowchart”

▪ Take your own (or someone else’s) completed essay. Read out just the first sentence of each paragraph to someone else in the class, who has the task of summarising your argument on the board in the form of a flowchart.

▪ A poorly constructed essay will consist of simple narrative statements.

▪ An adequately constructed essay will consist of isolated analytical statements.

▪ A well constructed essay will consist of analytical statements, linked together in a logical way.

2. Narrative Skills: “Mr. Interpretation”

▪ Read out a sentence of factual detail to someone else in the class from your essay. Their job is to provide an analytical point that it illustrates, for example:

▪ Person 1 presents a fact – “Tsarina Alexandra was German by birth”

▪ Person 2 the interpretation – “Provides explanation for opposition to Tsar during WW1”

Any student unable to provide an interpretation promptly is “knocked out” of the game. The winner is the “last person standing”.

3. Source Evaluation Skills: “Mr. Sceptical”

▪ This is the same as “Mr. Interpretation” except a third person in each “round” has to show an awareness of the limitations of the evidence:

▪ Person 1 presents a fact – “Tsar Nicholas was ‘not fit to run a village post office’ (Trotsky)”

▪ Person 3 the limitations – “But Trotsky was a hostile witness”, “But the Russians were deeply loyal to the principle of Tsarism”.

4. Challenging the Question: “Mr. Angry”

▪ Take a list of sample questions from past exam papers. For each one, copy it down and then underneath explain

▪ What loaded assumptions are within it.

▪ Why these are quite obviously completely and utterly wrong.

5. Structural Skills: Where are the paragraphs?

▪The teacher should take an article available in a digital format (e.g. from the History Today archives), paste it into a Word document, and then remove all of the paragraph marks and (as a final act of stylistic sadism) make it ‘fully justified’. Students should then be presented with this essay from hell, and challenged to deduce by reading it carefully where they think that each of the original paragraphs began. This can then lead into a discussion about how a writer determines when to start a new paragraph – for example, when they are about to make a brand new point in relation to the question,

6. Structural Skills: How effective are the topic sentences?

7. avoiding stock responses: “rewrite the model essay”.

▪ Take a model essay or an article provided by your teacher which answers a central question.

▪ Now examine past exam papers to see what other questions have been asked on this theme. In what ways would you need to re-write and re-structure the essay to focus on this question given?

8. Focusing on the command terms: “Guess the title of the essay”

▪ Another technique is for the students to copy and paste the entire article / essay into a piece of Word Cloud software such as Wordle or Taxedo. Students then have to guess the title of the essay from the results. If a writer has clearly focused on the command terms then these will appear at a higher frequency in the word count and therefore will be displayed more prominently in the word cloud.

9. Only incorporate a quote / historiography when you DISAGREE with it

▪ Using quotes in essays is too often a technique used by students to avoid thinking for themselves. Worst of all is the paragraph which is effectively a potted summary of another writer’s point of view. To avoid this, students should be asked to remove any quotes which they actually agree with. Instead, they should use quotes as a means of setting up a debate and demonstrating clear evidence of independent thinking (“Although AJP Taylor argued that…(quote)…this does not bear close scrutiny because…(contrary evidence))”.

10. General advice: The shape of an essay

A. in the introduction….

▪ Demonstrate understanding of the question. Clarify any key concepts that are mentioned (“Marxist”, “Propaganda”); outline which events and time period you will consider, and why

▪ Signpost the reader through your essay . In other words, give a very brief overview of how you plan to tackle the question.

b. In the main body of the essay…

▪ Start each paragraph with an argument (analysis). If you read the first sentence of each paragraph when you have finished, you should find that you have a summary of your case.

▪ Proceed to explain this point using evidence (including quotes from historians). The more specific this evidence is, the better.

▪ Wherever possible, explain why this evidence is valuable, or acknowledge its limitations.

c. In the conclusion…

▪ Answer the question by such things as

▪ Showing how your factors link together

▪ Showing how it depends on where / when / at whom you are looking

▪ Challenge the question by tackling any assumptions within it:

▪ E.g. “Why did the League of Nations only last 20 years?” suggests that this is a dismal record; you could make the point that the surprising thing is that it lasted so long as this given all the overwhelming problems it faced.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

ESL Essay Writing: 7 Important Tips to Teach Students Plus Resources for Writing Lessons

“Every good story has a beginning, a middle and an end.”

This is true for a good essay, too.

An essay needs a coherent structure to successfully articulate its arguments. Strong preparation and planning is crucial to providing that structure.

Of course, essay writing can be challenging for ESL students. They must order their thoughts and construct their arguments—all in their second language.

So, here are seven ESL essay writing tips that will allow your students to weave together a coherent and persuasive essay, plus teacher resources for writing activities, prompts and lessons!

1. Build the Essay Around a Central Question

2. use the traditional 5-paragraph essay structure, 3. plan the essay carefully before writing, 4. encourage research and rewriting, 5. practice utilizing repetition, 6. aim to write a “full circle” essay, 7. edit the essay to the end, esl essay writing resources.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Encourage your students to build all their writing around one central question.

That central question is the engine of the writing—it should drive everything!

If a word or sentence is not assisting that forward motion toward the explication of that question and its possible answers, then it needs to be reworded, rephrased or just plain cut out and discarded.

Lean writing is merciless. Focusing on a central question throughout the prewriting, writing and rewriting stages helps develop the critical faculties required to discern what to keep and what to throw away.

Providing a clear structure for the student to approach essay writing can do a lot to build their confidence. The 5-paragraph essay, or “hamburger” essay, provides that clear structure for ESL writers.

Generally, this structure employs five separate paragraphs for the entire essay. Each paragraph serves a specific purpose, melding together to form a coherent whole:

- Paragraph 1: The introductory paragraph. This includes the thesis statement, orientating the reader to the purpose of the essay.

- Paragraphs 2 to 4: The body paragraphs. These make individual points that are further backed up by various forms of evidence.

- Paragraph 5: The conclusion paragraph. This provides a summation of the arguments and a final statement of the thesis.

While students do not need to rigidly follow this format forever, the simple structure outlined above can serve as excellent training wheels for your writers.

Using the 5-paragraph structure as outlined above makes planning clear cut.

Once they have their theses and are planning their paragraphs, share with the students the ridiculously useful acronym P.E.E. This stands for Point, Explanation and Evidence.

Each body paragraph should make a point or argument in favor of the central thesis, followed by an explanation of this point and relevant evidence to back it up.

Students can make note of all their points, explanations and evidence before they start writing them in essay form. This helps take away some of the pressure ESL writers feel when faced with a blank page.

Extol the necessity for students to constantly refer to their planning. The mind-mapping techniques popularized by Tony Buzan can be useful at the planning stage and make for easy reference points to ensure focus is maintained throughout the essay.

Having a visual reference such as this can help ensure that your student-writers see each piece of the whole as well as that elusive “bigger picture,” so it becomes a case of seeing the forest and the trees!

Just as planning is crucial, so too is research.

Often ideas or connections do not occur until the writing process has begun. This is a good thing! Essay writing is a creative act, so students can have more ideas along the way and work them in as they go.

The key is to always be able to back up these ideas. Students who have done their research on their subject will be much more confident and articulate in expressing their arguments in their writing.

One way you can help students with context and research is to show relevant video content via FluentU . This language learning program uses authentic videos made by and for native speakers to help students learn English.

You can watch videos as a class or assign them directly to students for individual viewing. Videos come equipped with interactive bilingual subtitles and other learning tools such as multimedia flashcards and personalized quizzes so you can see how each student is doing.

No matter how your students do their research, the important thing is that they explore and understand their topic area before beginning the big task of writing their essay.

Even with thorough planning and research, writing oneself into a linguistic cul-de-sac is a common error. Especially with higher-level students, unforeseen currents can pull the student-writer off course.

Sometimes abandoning such a sentence helps. Going back to the drawing board and rewriting it is often best.

Students can be creative with their sentence structures when expressing simpler ideas and arguments. However, when it comes to more complex concepts, help them learn to use shorter sentences to break their arguments into smaller, more digestible chunks.

Essay writing falls firmly in the camp of non-fiction. However, that doesn’t mean that essay writers can’t use some of the techniques more traditionally associated with fiction, poetry and drama .

One technique that’s particularly useful in essay writing is repetition. Just as poetry relies heavily on rhythm, so too does argument. Repetition can provide that sense of rhythm.

This is because written language has its origins in oral language. Think of the great orators and demagogues and their use of repetition. Speechwriters, too, are well aware of the power of repetition.

The writing principle of the “rule of 3” states that ideas expressed in these terms are more convincing and memorable. This is true of both spoken and written words and the ideas they express. Teach your students to use this method in their essay writing.

The very structure of the 5-paragraph essay lends itself to planning for this repetition, in fact. Each idea that is explored in a body paragraph should be outlined first in the introductory paragraph.

Then, the single body paragraph devoted to the idea will explore it at greater length, supported by evidence. And the third rap of the hammer occurs in the summation of the concluding paragraph, driving the point securely and convincingly home.

As mentioned at the start of this post, every good essay has a beginning, a middle and an end.

Each point made, explained and supported by evidence is a step toward what the writing teacher Roy Peter Clark calls “closing the circle of meaning.”

In planning for the conclusion of the essay, the students should take the opportunity to reaffirm their position. By referring to the points outlined in the introduction and driving them home one last time, the student-writer is bringing the essay to a satisfying full circle.

This may be accomplished by employing various strategies: an apt quotation, referring to future consequences or attempting to inspire and mobilize the reader.

Ending with a succinct quotation has the double benefit of lending some authoritative weight to the argument while also allowing the student to select a well-written, distilled expression of their central thesis. This can make for a strong ending, particularly for ESL students.

Often the essay thesis will suggest its own ending. If the essay is structured around a problem, it’s frequently appropriate to end the essay by offering solutions to the problem and outlining potential consequences if those solutions are not followed.

In the more polemical type of essay, the student may end with a call to arms, a plea for action on the part of the reader.

The strategy chosen by the student will depend largely on what fits the central thesis of their essay best.

For the ESL student, the final edit is especially important.

It offers a final chance to check form and meaning. For all writers, this process can be daunting, but more so for language students.

Often, ESL students will use the same words over and over again due to a limited vocabulary. Encourage your students to employ a thesaurus in the final draft before submission. This will freshen up their work, making it more readable, and will also increase their active vocabulary in the long run!

Another useful strategy at this stage is to encourage students to read their work aloud before handing it in.

This can be good pronunciation practice , but it also provides an opportunity to listen for grammatical errors. Further, it helps students hear where punctuation is required in the text, helping the overall rhythm and readability of the writing.

To really help your students become master essay writers, you’ll want to provide them with plenty of opportunities to test and flex their skills.

Writing prompts and exercises are a good place to start:

Descriptive writing activities encourage students to get creative and use their five senses, literary devices and diverse vocabulary. Read on for eight descriptive writing…

https://www.fluentu.com/blog/educator-english/esl-writing-projects/ https://www.fluentu.com/blog/educator-english/esl-picture-description/

Giving good ESL writing prompts is important because inspiring prompts inspire students to write more and writing more is how they improve. Read this post to learn 50…

You’ll likely also want to teach them more about the mechanics of writing :

Are you looking for ESL writing skills to share with your ESL students? In this guide, you’ll find different ESL writing techniques, such as helping students understand…

Would you like to introduce journal writing into your ESL classes? Fantastic idea! Here are 9 essential tips to make it creative, engaging and fun.

https://www.fluentu.com/blog/educator-english/esl-writing-lessons/

Essays are a great way not only for students to learn how the language works, but also to learn about themselves.

Formulating thoughts and arguments about various subjects is good exercise for not only the students’ linguistic faculties, but also for understanding who they are and how they see the world.

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Teach Persuasive Writing

Last Updated: November 3, 2022 References

This article was co-authored by Alexander Peterman, MA . Alexander Peterman is a Private Tutor in Florida. He received his MA in Education from the University of Florida in 2017. This article has been viewed 49,767 times.

There are many ways to teach persuasive writing, and utilizing more than one approach can be good for your students. Not all students learn the same way, so demonstrating by example how to write persuasively might reach some of your students. Carefully explaining written assignments or setting up in-class debates and then letting your students learn by doing are methods for teaching persuasive writing that might reach different learners in your class. And reviewing your students' work and giving them plenty of feedback can also be an effective way to teach persuasive writing.

Demonstrating Persuasive Writing

- For example, you might show elementary school age students a piece of writing that argues that one brand of soda is better than the other. The best brand of soda is based on opinion, but your students will still see that they still have to give reasons or justification that supports their opinion.

- For middle and high school age students, a good example might be an article that argues that older teens need more sleep than elementary age children. This article will likely use scientific research to support its claims, so your students will see that the reasons and justifications they give to support their position need to based on more than how they feel about a particular subject. [2] X Research source

- For example, if you've read a piece about the benefits of more sleep for older students, you could say "Do you think older students need more sleep? Why?" Your students therefore not only have to assess the article's argument, but how the author used evidence to support that argument. [3] X Research source

- For example, using an overhead projector, start drafting your own essay on a topic you've selected beforehand. Think out loud and write as you go so that your students can actually see what the writing process looks like, and so they can see that even teachers are not perfect in the way that they write and that quality writing takes time and practice. However, do some preparation in advance so that you do not end up wasting time or looking disorganized.

- This is an especially useful strategy when you're working with students who don't have a lot of experience with writing - elementary school students or perhaps students whose first language is not English. This method can also be useful for older students as the complexity of their assignments increases. [4] X Research source

Using Debates

- You can use an informal or formal debate, or both on successive days. The informal debate should be organized immediately after you tell your students what you'll be doing in class. The formal debate should take place after they've had some time to prepare. [5] X Research source

- You may even consider setting up a mock courtroom. Assigning roles to your students, such as prosecutor, defense, judge, and jury members will help to keep them focused and interested in the conversation.

- For example, read a statement like “Men and women have equal opportunities in life.” Then ask your students who agree with the statement to line up on one side of the room and those who disagree to line up on another side. [6] X Research source

- If you're using a more formal debate set up, at this point you can pass out supporting material to each side of the debate and either ask them to read it then or be prepared to use it the next day. You can ask them to collect their own supporting material for a future debate. [8] X Research source

- For example, you could point out that when they made a statement of fact and then gave a reason for it - for example, if they said older students need more sleep because they are generally involved in more after school activities - they set up what could be the first paragraph of their essay. They made a statement, then backed it up with evidence.

Having Your Students Write an Assignment

- For example, your students might feel strongly that there is not enough recess time. Or they might feel they should be allowed to watch more TV at home.

- In some situations, assigning a topic may be a good idea. For example, if you are trying to prepare your students to take a state exam, then assigning a topic will give them practice writing about a topic they may not be particularly interested in, which could be the case on test day.