- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Is Online Learning Effective?

A new report found that the heavy dependence on technology during the pandemic caused “staggering” education inequality. What was your experience?

By Natalie Proulx

During the coronavirus pandemic, many schools moved classes online. Was your school one of them? If so, what was it like to attend school online? Did you enjoy it? Did it work for you?

In “ Dependence on Tech Caused ‘Staggering’ Education Inequality, U.N. Agency Says ,” Natasha Singer writes:

In early 2020, as the coronavirus spread, schools around the world abruptly halted in-person education. To many governments and parents, moving classes online seemed the obvious stopgap solution. In the United States, school districts scrambled to secure digital devices for students. Almost overnight, videoconferencing software like Zoom became the main platform teachers used to deliver real-time instruction to students at home. Now a report from UNESCO , the United Nations’ educational and cultural organization, says that overreliance on remote learning technology during the pandemic led to “staggering” education inequality around the world. It was, according to a 655-page report that UNESCO released on Wednesday, a worldwide “ed-tech tragedy.” The report, from UNESCO’s Future of Education division, is likely to add fuel to the debate over how governments and local school districts handled pandemic restrictions, and whether it would have been better for some countries to reopen schools for in-person instruction sooner. The UNESCO researchers argued in the report that “unprecedented” dependence on technology — intended to ensure that children could continue their schooling — worsened disparities and learning loss for hundreds of millions of students around the world, including in Kenya, Brazil, Britain and the United States. The promotion of remote online learning as the primary solution for pandemic schooling also hindered public discussion of more equitable, lower-tech alternatives, such as regularly providing schoolwork packets for every student, delivering school lessons by radio or television — and reopening schools sooner for in-person classes, the researchers said. “Available evidence strongly indicates that the bright spots of the ed-tech experiences during the pandemic, while important and deserving of attention, were vastly eclipsed by failure,” the UNESCO report said. The UNESCO researchers recommended that education officials prioritize in-person instruction with teachers, not online platforms, as the primary driver of student learning. And they encouraged schools to ensure that emerging technologies like A.I. chatbots concretely benefited students before introducing them for educational use. Education and industry experts welcomed the report, saying more research on the effects of pandemic learning was needed. “The report’s conclusion — that societies must be vigilant about the ways digital tools are reshaping education — is incredibly important,” said Paul Lekas, the head of global public policy for the Software & Information Industry Association, a group whose members include Amazon, Apple and Google. “There are lots of lessons that can be learned from how digital education occurred during the pandemic and ways in which to lessen the digital divide. ” Jean-Claude Brizard, the chief executive of Digital Promise, a nonprofit education group that has received funding from Google, HP and Verizon, acknowledged that “technology is not a cure-all.” But he also said that while school systems were largely unprepared for the pandemic, online education tools helped foster “more individualized, enhanced learning experiences as schools shifted to virtual classrooms.” Education International, an umbrella organization for about 380 teachers’ unions and 32 million teachers worldwide, said the UNESCO report underlined the importance of in-person, face-to-face teaching. “The report tells us definitively what we already know to be true, a place called school matters,” said Haldis Holst, the group’s deputy general secretary. “Education is not transactional nor is it simply content delivery. It is relational. It is social. It is human at its core.”

Students, read the entire article and then tell us:

What findings from the report, if any, surprised you? If you participated in online learning during the pandemic, what in the report reflected your experience? If the researchers had asked you about what remote learning was like for you, what would you have told them?

At this point, most schools have returned to in-person teaching, but many still use technology in the classroom. How much tech is involved in your day-to-day education? Does this method of learning work well for you? If you had a say, would you want to spend more or less time online while in school?

What are some of the biggest benefits you have seen from technology when it comes to your education? What are some of the biggest drawbacks?

Haldis Holst, UNESCO’s deputy general secretary, said: “The report tells us definitively what we already know to be true, a place called school matters. Education is not transactional nor is it simply content delivery. It is relational. It is social. It is human at its core.” What is your reaction to that statement? Do you agree? Why or why not?

As a student, what advice would you give to schools that are already using or are considering using educational technology?

Students 13 and older in the United States and Britain, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public and may appear in print.

Find more Student Opinion questions here. Teachers, check out this guide to learn how you can incorporate these prompts into your classroom.

Natalie Proulx joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2017 after working as an English language arts teacher and curriculum writer. More about Natalie Proulx

A Comparison of Student Learning Outcomes: Online Education vs. Traditional Classroom Instruction

Despite the prevalence of online learning today, it is often viewed as a less favorable option when compared to the traditional, in-person educational experience. Criticisms of online learning come from various sectors, like employer groups, college faculty, and the general public, and generally includes a lack of perceived quality as well as rigor. Additionally, some students report feelings of social isolation in online learning (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019).

In my experience as an online student as well as an online educator, online learning has been just the opposite. I have been teaching in a fully online master’s degree program for the last three years and have found it to be a rich and rewarding experience for students and faculty alike. As an instructor, I have felt more connected to and engaged with my online students when compared to in-person students. I have also found that students are actively engaged with course content and demonstrate evidence of higher-order thinking through their work. Students report high levels of satisfaction with their experiences in online learning as well as the program overall as indicated in their Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) at the end of every course. I believe that intelligent course design, in addition to my engagement in professional development related to teaching and learning online, has greatly influenced my experience.

In an article by Wiley Education Services, authors identified the top six challenges facing US institutions of higher education, and include:

- Declining student enrollment

- Financial difficulties

- Fewer high school graduates

- Decreased state funding

- Lower world rankings

- Declining international student enrollments

Of the strategies that institutions are exploring to remedy these issues, online learning is reported to be a key focus for many universities (“Top Challenges Facing US Higher Education”, n.d.).

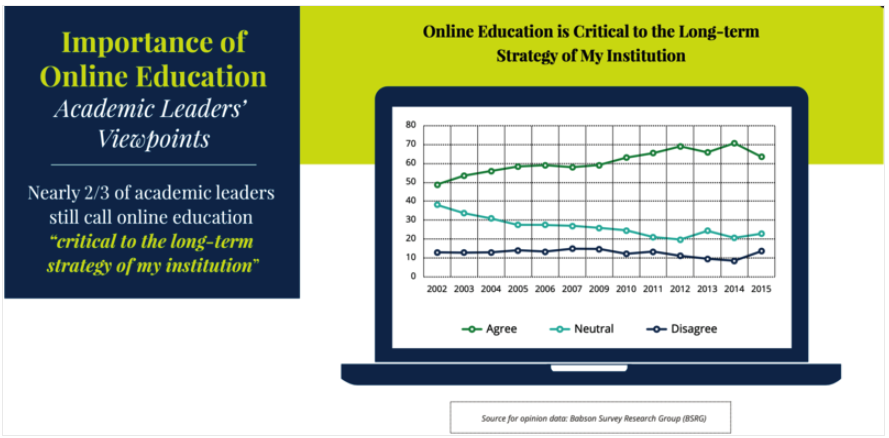

Babson Survey Research Group, 2016, [PDF file].

Some of the questions I would like to explore in further research include:

- What factors influence engagement and connection in distance education?

- Are the learning outcomes in online education any different than the outcomes achieved in a traditional classroom setting?

- How do course design and instructor training influence these factors?

- In what ways might educational technology tools enhance the overall experience for students and instructors alike?

In this literature review, I have chosen to focus on a comparison of student learning outcomes in online education versus the traditional classroom setting. My hope is that this research will unlock the answers to some of the additional questions posed above and provide additional direction for future research.

Online Learning Defined

According to Mayadas, Miller, and Sener (2015), online courses are defined by all course activity taking place online with no required in-person sessions or on-campus activity. It is important to note, however, that the Babson Survey Research Group, a prominent organization known for their surveys and research in online learning, defines online learning as a course in which 80-100% occurs online. While this distinction was made in an effort to provide consistency in surveys year over year, most institutions continue to define online learning as learning that occurs 100% online.

Blended or hybrid learning is defined by courses that mix face to face meetings, sessions, or activities with online work. The ratio of online to classroom activity is often determined by the label in which the course is given. For example, a blended classroom course would likely include more time spent in the classroom, with the remaining work occurring outside of the classroom with the assistance of technology. On the other hand, a blended online course would contain a greater percentage of work done online, with some required in-person sessions or meetings (Mayadas, Miller, & Sener, 2015).

A classroom course (also referred to as a traditional course) refers to course activity that is anchored to a regular meeting time.

Enrollment Trends in Online Education

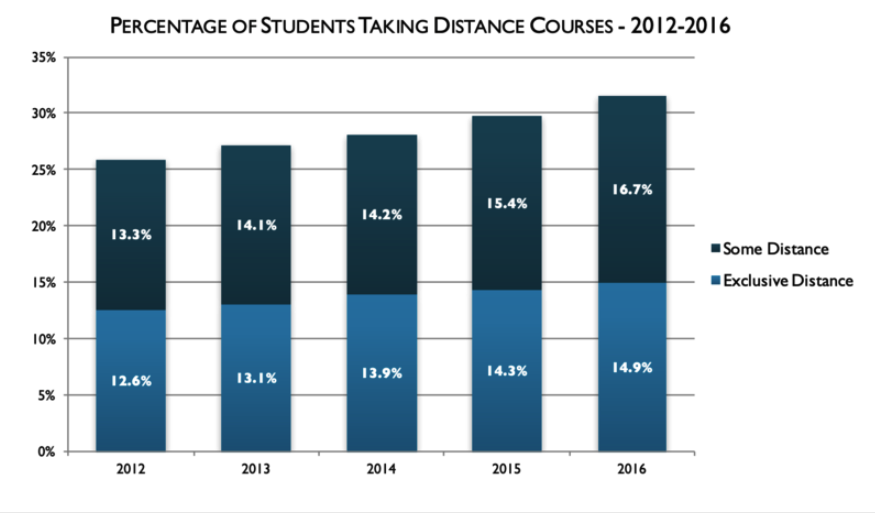

There has been an upward trend in the number of postsecondary students enrolled in online courses in the U.S. since 2002. A report by the Babson Survey Research Group showed that in 2016, more than six million students were enrolled in at least one online course. This number accounted for 31.6% of all college students (Seaman, Allen, & Seaman, 2018). Approximately one in three students are enrolled in online courses with no in-person component. Of these students, 47% take classes in a fully online program. The remaining 53% take some, but not all courses online (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019).

(Seaman et al., 2016, p. 11)

Perceptions of Online Education

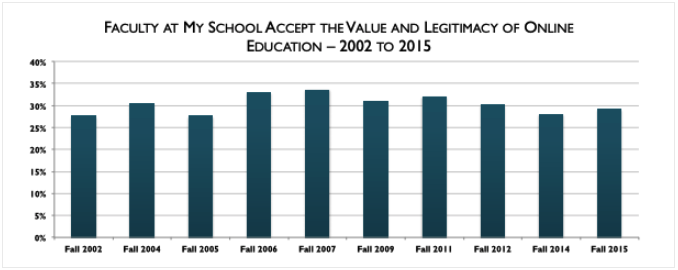

In a 2016 report by the Babson Survey Research Group, surveys of faculty between 2002-2015 showed approval ratings regarding the value and legitimacy of online education ranged from 28-34 percent. While numbers have increased and decreased over the thirteen-year time frame, faculty approval was at 29 percent in 2015, just 1 percent higher than the approval ratings noted in 2002 – indicating that perceptions have remained relatively unchanged over the years (Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016).

(Allen, I.E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., Taylor Strout, T., 2016, p. 26)

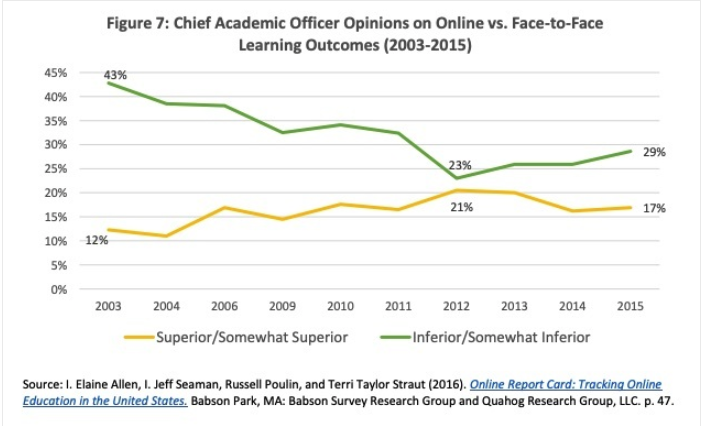

In a separate survey of chief academic officers, perceptions of online learning appeared to align with that of faculty. In this survey, leaders were asked to rate their perceived quality of learning outcomes in online learning when compared to traditional in-person settings. While the percentage of leaders rating online learning as “inferior” or “somewhat inferior” to traditional face-to-face courses dropped from 43 percent to 23 percent between 2003 to 2012, the number rose again to 29 percent in 2015 (Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016).

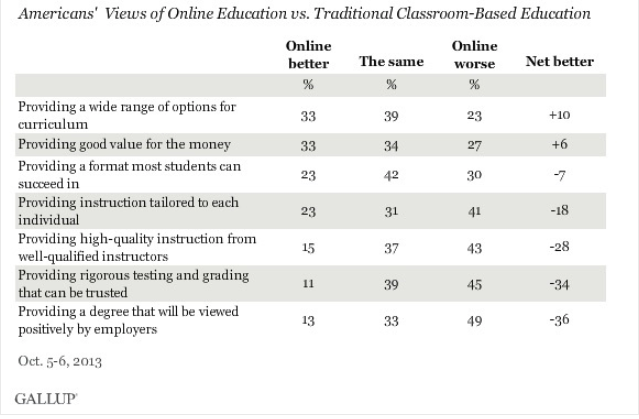

Faculty and academic leaders in higher education are not alone when it comes to perceptions of inferiority when compared to traditional classroom instruction. A 2013 Gallop poll assessing public perceptions showed that respondents rated online education as “worse” in five of the seven categories seen in the table below.

(Saad, L., Busteed, B., and Ogisi, M., 2013, October 15)

In general, Americans believed that online education provides both lower quality and less individualized instruction and less rigorous testing and grading when compared to the traditional classroom setting. In addition, respondents also thought that employers would perceive a degree from an online program less positively when compared to a degree obtained through traditional classroom instruction (Saad, Busteed, & Ogisi, 2013).

Student Perceptions of Online Learning

So what do students have to say about online learning? In Online College Students 2015: Comprehensive Data on Demands and Preferences, 1500 college students who were either enrolled or planning to enroll in a fully online undergraduate, graduate, or certificate program were surveyed. 78 percent of students believed the academic quality of their online learning experience to be better than or equal to their experiences with traditional classroom learning. Furthermore, 30 percent of online students polled said that they would likely not attend classes face to face if their program were not available online (Clienfelter & Aslanian, 2015). The following video describes some of the common reasons why students choose to attend college online.

How Online Learning Affects the Lives of Students ( Pearson North America, 2018, June 25)

In a 2015 study comparing student perceptions of online learning with face to face learning, researchers found that the majority of students surveyed expressed a preference for traditional face to face classes. A content analysis of the findings, however, brought attention to two key ideas: 1) student opinions of online learning may be based on “old typology of distance education” (Tichavsky, et al, 2015, p.6) as opposed to actual experience, and 2) a student’s inclination to choose one form over another is connected to issues of teaching presence and self-regulated learning (Tichavsky et al, 2015).

Student Learning Outcomes

Given the upward trend in student enrollment in online courses in postsecondary schools and the steady ratings of the low perceived value of online learning by stakeholder groups, it should be no surprise that there is a large body of literature comparing student learning outcomes in online classes to the traditional classroom environment.

While a majority of the studies reviewed found no significant difference in learning outcomes when comparing online to traditional courses (Cavanaugh & Jacquemin, 2015; Kemp & Grieve, 2014; Lyke & Frank 2012; Nichols, Shaffer, & Shockey, 2003; Stack, 2015; Summers, Waigandt, & Whittaker, 2005), there were a few outliers. In a 2019 report by Protopsaltis & Baum, authors confirmed that while learning is often found to be similar between the two mediums, students “with weak academic preparation and those from low-income and underrepresented backgrounds consistently underperform in fully-online environments” (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019, n.p.). An important consideration, however, is that these findings are primarily based on students enrolled in online courses at the community college level – a demographic with a historically high rate of attrition compared to students attending four-year institutions (Ashby, Sadera, & McNary, 2011). Furthermore, students enrolled in online courses have been shown to have a 10 – 20 percent increase in attrition over their peers who are enrolled in traditional classroom instruction (Angelino, Williams, & Natvig, 2007). Therefore, attrition may be a key contributor to the lack of achievement seen in this subgroup of students enrolled in online education.

In contrast, there were a small number of studies that showed that online students tend to outperform those enrolled in traditional classroom instruction. One study, in particular, found a significant difference in test scores for students enrolled in an online, undergraduate business course. The confounding variable, in this case, was age. Researchers found a significant difference in performance in nontraditional age students over their traditional age counterparts. Authors concluded that older students may elect to take online classes for practical reasons related to outside work schedules, and this may, in turn, contribute to the learning that occurs overall (Slover & Mandernach, 2018).

In a meta-analysis and review of online learning spanning the years 1996 to 2008, authors from the US Department of Education found that students who took all or part of their classes online showed better learning outcomes than those students who took the same courses face-to-face. In these cases, it is important to note that there were many differences noted in the online and face-to-face versions, including the amount of time students spent engaged with course content. The authors concluded that the differences in learning outcomes may be attributed to learning design as opposed to the specific mode of delivery (Means, Toyoma, Murphy, Bakia, Jones, 2009).

Limitations and Opportunities

After examining the research comparing student learning outcomes in online education with the traditional classroom setting, there are many limitations that came to light, creating areas of opportunity for additional research. In many of the studies referenced, it is difficult to determine the pedagogical practices used in course design and delivery. Research shows the importance of student-student and student-teacher interaction in online learning, and the positive impact of these variables on student learning (Bernard, Borokhovski, Schmid, Tamim, & Abrami, 2014). Some researchers note that while many studies comparing online and traditional classroom learning exist, the methodologies and design issues make it challenging to explain the results conclusively (Mollenkopf, Vu, Crow, & Black, 2017). For example, some online courses may be structured in a variety of ways, i.e. self-paced, instructor-led and may be classified as synchronous or asynchronous (Moore, Dickson-Deane, Galyan, 2011)

Another gap in the literature is the failure to use a common language across studies to define the learning environment. This issue is explored extensively in a 2011 study by Moore, Dickson-Deane, and Galyan. Here, the authors examine the differences between e-learning, online learning, and distance learning in the literature, and how the terminology is often used interchangeably despite the variances in characteristics that define each. The authors also discuss the variability in the terms “course” versus “program”. This variability in the literature presents a challenge when attempting to compare one study of online learning to another (Moore, Dickson-Deane, & Galyan, 2011).

Finally, much of the literature in higher education focuses on undergraduate-level classes within the United States. Little research is available on outcomes in graduate-level classes as well as general information on student learning outcomes and perceptions of online learning outside of the U.S.

As we look to the future, there are additional questions to explore in the area of online learning. Overall, this research led to questions related to learning design when comparing the two modalities in higher education. Further research is needed to investigate the instructional strategies used to enhance student learning, especially in students with weaker academic preparation or from underrepresented backgrounds. Given the integral role that online learning is expected to play in the future of higher education in the United States, it may be even more critical to move beyond comparisons of online versus face to face. Instead, choosing to focus on sound pedagogical quality with consideration for the mode of delivery as a means for promoting positive learning outcomes.

Allen, I.E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., & Straut, T. (2016). Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States [PDF file]. Babson Survey Research Group. http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/onlinereportcard.pdf

Angelino, L. M., Williams, F. K., & Natvig, D. (2007). Strategies to engage online students and reduce attrition rates. The Journal of Educators Online , 4(2).

Ashby, J., Sadera, W.A., & McNary, S.W. (2011). Comparing student success between developmental math courses offered online, blended, and face-to-face. Journal of Interactive Online Learning , 10(3), 128-140.

Bernard, R.M., Borokhovski, E., Schmid, R.F., Tamim, R.M., & Abrami, P.C. (2014). A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. Journal of Computing in Higher Education , 26(1), 87-122.

Cavanaugh, J.K. & Jacquemin, S.J. (2015). A large sample comparison of grade based student learning outcomes in online vs. face-fo-face courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 19(2).

Clinefelter, D. L., & Aslanian, C. B. (2015). Online college students 2015: Comprehensive data on demands and preferences. https://www.learninghouse.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/OnlineCollegeStudents2015.pdf

Golubovskaya, E.A., Tikhonova, E.V., & Mekeko, N.M. (2019). Measuring learning outcome and students’ satisfaction in ELT (e-learning against conventional learning). Paper presented the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 34-38. Doi: 10.1145/3337682.3337704

Kemp, N. & Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-face or face-to-screen? Undergraduates’ opinions and test performance in classroom vs. online learning. Frontiers in Psychology , 5. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01278

Lyke, J., & Frank, M. (2012). Comparison of student learning outcomes in online and traditional classroom environments in a psychology course. (Cover story). Journal of Instructional Psychology , 39(3/4), 245-250.

Mayadas, F., Miller, G. & Senner, J. Definitions of E-Learning Courses and Programs Version 2.0. Online Learning Consortium. https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/updated-e-learning-definitions-2/

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. US Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf

Mollenkopf, D., Vu, P., Crow, S, & Black, C. (2017). Does online learning deliver? A comparison of student teacher outcomes from candidates in face to face and online program pathways. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. 20(1).

Moore, J.L., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyan, K. (2011). E-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? The Internet and Higher Education . 14(2), 129-135.

Nichols, J., Shaffer, B., & Shockey, K. (2003). Changing the face of instruction: Is online or in-class more effective? College & Research Libraries , 64(5), 378–388. https://doi-org.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.5860/crl.64.5.378

Parsons-Pollard, N., Lacks, T.R., & Grant, P.H. (2008). A comparative assessment of student learning outcomes in large online and traditional campus based introduction to criminal justice courses. Criminal Justice Studies , 2, 225-239.

Pearson North America. (2018, June 25). How Online Learning Affects the Lives of Students . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPDMagf_oAE

Protopsaltis, S., & Baum, S. (2019). Does online education live up to its promise? A look at the evidence and implications for federal policy [PDF file]. http://mason.gmu.edu/~sprotops/OnlineEd.pdf

Saad, L., Busteed, B., & Ogisi, M. (October 15, 2013). In U.S., Online Education Rated Best for Value and Options. https://news.gallup.com/poll/165425/online-education-rated-best-value-options.aspx

Stack, S. (2015). Learning Outcomes in an Online vs Traditional Course. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , 9(1).

Seaman, J.E., Allen, I.E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade Increase: Tracking Distance Education in the United States [PDF file]. Babson Survey Research Group. http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradeincrease.pdf

Slover, E. & Mandernach, J. (2018). Beyond Online versus Face-to-Face Comparisons: The Interaction of Student Age and Mode of Instruction on Academic Achievement. Journal of Educators Online, 15(1) . https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1168945.pdf

Summers, J., Waigandt, A., & Whittaker, T. (2005). A Comparison of Student Achievement and Satisfaction in an Online Versus a Traditional Face-to-Face Statistics Class. Innovative Higher Education , 29(3), 233–250. https://doi-org.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.1007/s10755-005-1938-x

Tichavsky, L.P., Hunt, A., Driscoll, A., & Jicha, K. (2015). “It’s just nice having a real teacher”: Student perceptions of online versus face-to-face instruction. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 9(2).

Wiley Education Services. (n.d.). Top challenges facing U.S. higher education. https://edservices.wiley.com/top-higher-education-challenges/

July 17, 2020

Online Learning

college , distance education , distance learning , face to face , higher education , online learning , postsecondary , traditional learning , university , virtual learning

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

© 2024 — Powered by WordPress

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Home » Education » What is the Difference Between Online Learning and Offline Learning

What is the Difference Between Online Learning and Offline Learning

The main difference between online learning and offline learning lies in the method of teaching . Online learning permits the teachers to use digitalized tools and teaching methods while teaching tools and methods in offline teaching take a more traditional approach.

The current Covid-19 pandemic context has restricted education to online platforms, replacing offline physical classrooms. Simply put, online learning has become the new normal. However, we should keep in mind that online learning cannot completely take the place of offline learning as both online and offline learning have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Key Areas Covered

1. What is Online Learning – Definition, Features, Pros and Cons 2. What is Offline Learning – Definition, Features, Pros and Cons 3. Similarities Between Online Learning and Offline Learning – Outline of Common Features 4. Difference Between Online Learning and Offline Learning – Comparison of Key Differences

Online Learning, Offline Learning

What is Online Learning

Online learning is a process where students get access to education and knowledge via virtual classrooms. In online learning, learners get the opportunity to access learning materials published by educators and researchers in every corner of the world as long as they have the required equipment and a working internet connection.

Online education gives teachers a chance to incorporate many online learning tools such as audio, videos, virtual whiteboards, animations, live chats, and virtual conference rooms in order to facilitate the learning process.

Compared to offline learning and physical classrooms, online learning and education is a more flexible method of teaching as it gives both teachers and students easy access to study material in the comfort of home. Above all, online learning is quite beneficial for students who are unable to attend physical classes due to varying difficulties: distance, physical disabilities, etc. Furthermore, online learning makes students self-disciplined and helps them to improve their time management skills. Furthermore, this process allows students to learn at their own pace.

What is Offline Learning

Offline learning refers to traditional education that allows students to have face-to-face interactions with teachers and peer groups. Although online teaching and learning are considered to be the future of education, they cannot replace offline education in every aspect. Compared to online learning, offline learning is not disturbed by any technical issues. The traditional offline classroom also helps students improve their teamwork and interactive skills as they have to work in the same classroom collaborating with peers.

Most significantly, offline education allows teachers to monitor students’ responses and progress more efficiently and also observe and supervise their behavior catering to the individual need of each student as required. Therefore, it can be more convenient and easily accessible.

Similarities Between Online Learning and Offline Learning

- Online teaching and offline teaching involve both learners and teachers.

- These processes aim to impart knowledge to students.

- Both online and offline learning involve classrooms: online learning involves a virtual classroom, while offline learning involves a physical classroom.

Difference Between Online Learning and Offline Learning

Online learning refers to a process where students get access to education and knowledge via virtual classrooms, while offline learning refers to traditional education that allows students to have face-to-face interactions with teachers and peer groups.

Type of Classroom

Online learning happens in a virtual classroom, while offline learning can take place inside or outside the traditional classroom.

Mode of Education

When it comes to online education, the mode of teaching is more digitalized as teachers get the chance to use many online learning tools such as audios, videos, virtual whiteboards, animations, live chats, and virtual conference rooms in order to facilitate the learning process. In contrast, offline learning allows students to acquire knowledge inside a more practical environment, giving students a chance to interact with teachers and peers and allowing them to actively take part in live discussions.

Teacher’s Role

Offline education allows teachers to monitor students’ responses and progress more efficiently and observe and supervise their behavior, catering to the individual need of each student. But online education does not allow teachers to monitor students’ progress closely or supervise their behavior.

Students’ Role

In online education, students are more independent as they can learn at their own pace, but in offline education, students are under the strict supervision of teachers.

Student Engagement

Student engagement is more effective in offline education than in online education as offline education involves face-to-face interactions.

Interpersonal Skills of Students

Online learning is less effective than offline education in developing the interpersonal skills of students. Since online learning isolates the student, no competition can be seen among students. However, offline education tends to be more interactive and competitive.

Convenience

It’s easy to join online learning as long as students have a computer and a good internet connection, but to join offline learning, students need to travel to the education institute, which can be time consuming.

The main difference between online learning and offline learning is that online learning is a process where students get access to education and knowledge via virtual classrooms, while offline learning involves traditional education that allows students to have face-to-face interactions with teachers and peer groups.

1. “ Benefits of Online Education .” Community College of Aurora in Colorado: Aurora, Denver Metro, and Online. 2. “ Advantages of Offline Classes in School Campus .” SAGE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, 28 Oct. 2021.

Image Courtesy:

1. “ Education-online-learning-icon ” (CC0) via Pixabay 2. “ Blackboard-boys-chalkboard-children ” (CC0) via Pixabay

About the Author: Anuradha

Anuradha has a BA degree in English, French, and Translation studies. She is currently reading for a Master's degree in Teaching English Literature in a Second Language Context. Her areas of interests include Arts and Literature, Language and Education, Nature and Animals, Cultures and Civilizations, Food, and Fashion.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Online and face‐to‐face learning: Evidence from students’ performance during the Covid‐19 pandemic

Carolyn chisadza.

1 Department of Economics, University of Pretoria, Hatfield South Africa

Matthew Clance

Thulani mthembu.

2 Department of Education Innovation, University of Pretoria, Hatfield South Africa

Nicky Nicholls

Eleni yitbarek.

This study investigates the factors that predict students' performance after transitioning from face‐to‐face to online learning as a result of the Covid‐19 pandemic. It uses students' responses from survey questions and the difference in the average assessment grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown at a South African university. We find that students' performance was positively associated with good wifi access, relative to using mobile internet data. We also observe lower academic performance for students who found transitioning to online difficult and who expressed a preference for self‐study (i.e. reading through class slides and notes) over assisted study (i.e. joining live lectures or watching recorded lectures). The findings suggest that improving digital infrastructure and reducing the cost of internet access may be necessary for mitigating the impact of the Covid‐19 pandemic on education outcomes.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Covid‐19 pandemic has been a wake‐up call to many countries regarding their capacity to cater for mass online education. This situation has been further complicated in developing countries, such as South Africa, who lack the digital infrastructure for the majority of the population. The extended lockdown in South Africa saw most of the universities with mainly in‐person teaching scrambling to source hardware (e.g. laptops, internet access), software (e.g. Microsoft packages, data analysis packages) and internet data for disadvantaged students in order for the semester to recommence. Not only has the pandemic revealed the already stark inequality within the tertiary student population, but it has also revealed that high internet data costs in South Africa may perpetuate this inequality, making online education relatively inaccessible for disadvantaged students. 1

The lockdown in South Africa made it possible to investigate the changes in second‐year students' performance in the Economics department at the University of Pretoria. In particular, we are interested in assessing what factors predict changes in students' performance after transitioning from face‐to‐face (F2F) to online learning. Our main objectives in answering this study question are to establish what study materials the students were able to access (i.e. slides, recordings, or live sessions) and how students got access to these materials (i.e. the infrastructure they used).

The benefits of education on economic development are well established in the literature (Gyimah‐Brempong, 2011 ), ranging from health awareness (Glick et al., 2009 ), improved technological innovations, to increased capacity development and employment opportunities for the youth (Anyanwu, 2013 ; Emediegwu, 2021 ). One of the ways in which inequality is perpetuated in South Africa, and Africa as a whole, is through access to education (Anyanwu, 2016 ; Coetzee, 2014 ; Tchamyou et al., 2019 ); therefore, understanding the obstacles that students face in transitioning to online learning can be helpful in ensuring more equal access to education.

Using students' responses from survey questions and the difference in the average grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown, our findings indicate that students' performance in the online setting was positively associated with better internet access. Accessing assisted study material, such as narrated slides or recordings of the online lectures, also helped students. We also find lower academic performance for students who reported finding transitioning to online difficult and for those who expressed a preference for self‐study (i.e. reading through class slides and notes) over assisted study (i.e. joining live lectures or watching recorded lectures). The average grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown were about two points and three points lower for those who reported transitioning to online teaching difficult and for those who indicated a preference for self‐study, respectively. The findings suggest that improving the quality of internet infrastructure and providing assisted learning can be beneficial in reducing the adverse effects of the Covid‐19 pandemic on learning outcomes.

Our study contributes to the literature by examining the changes in the online (post‐lockdown) performance of students and their F2F (pre‐lockdown) performance. This approach differs from previous studies that, in most cases, use between‐subject designs where one group of students following online learning is compared to a different group of students attending F2F lectures (Almatra et al., 2015 ; Brown & Liedholm, 2002 ). This approach has a limitation in that that there may be unobserved characteristics unique to students choosing online learning that differ from those choosing F2F lectures. Our approach avoids this issue because we use a within‐subject design: we compare the performance of the same students who followed F2F learning Before lockdown and moved to online learning during lockdown due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Moreover, the study contributes to the limited literature that compares F2F and online learning in developing countries.

Several studies that have also compared the effectiveness of online learning and F2F classes encounter methodological weaknesses, such as small samples, not controlling for demographic characteristics, and substantial differences in course materials and assessments between online and F2F contexts. To address these shortcomings, our study is based on a relatively large sample of students and includes demographic characteristics such as age, gender and perceived family income classification. The lecturer and course materials also remained similar in the online and F2F contexts. A significant proportion of our students indicated that they never had online learning experience before. Less than 20% of the students in the sample had previous experience with online learning. This highlights the fact that online education is still relatively new to most students in our sample.

Given the global experience of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR), 2 with rapidly accelerating technological progress, South Africa needs to be prepared for the possibility of online learning becoming the new norm in the education system. To this end, policymakers may consider engaging with various organizations (schools, universities, colleges, private sector, and research facilities) To adopt interventions that may facilitate the transition to online learning, while at the same time ensuring fair access to education for all students across different income levels. 3

1.1. Related literature

Online learning is a form of distance education which mainly involves internet‐based education where courses are offered synchronously (i.e. live sessions online) and/or asynchronously (i.e. students access course materials online in their own time, which is associated with the more traditional distance education). On the other hand, traditional F2F learning is real time or synchronous learning. In a physical classroom, instructors engage with the students in real time, while in the online format instructors can offer real time lectures through learning management systems (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate), or record the lectures for the students to watch later. Purely online courses are offered entirely over the internet, while blended learning combines traditional F2F classes with learning over the internet, and learning supported by other technologies (Nguyen, 2015 ).

Moreover, designing online courses requires several considerations. For example, the quality of the learning environment, the ease of using the learning platform, the learning outcomes to be achieved, instructor support to assist and motivate students to engage with the course material, peer interaction, class participation, type of assessments (Paechter & Maier, 2010 ), not to mention training of the instructor in adopting and introducing new teaching methods online (Lundberg et al., 2008 ). In online learning, instructors are more facilitators of learning. On the other hand, traditional F2F classes are structured in such a way that the instructor delivers knowledge, is better able to gauge understanding and interest of students, can engage in class activities, and can provide immediate feedback on clarifying questions during the class. Additionally, the designing of traditional F2F courses can be less time consuming for instructors compared to online courses (Navarro, 2000 ).

Online learning is also particularly suited for nontraditional students who require flexibility due to work or family commitments that are not usually associated with the undergraduate student population (Arias et al., 2018 ). Initially the nontraditional student belonged to the older adult age group, but with blended learning becoming more commonplace in high schools, colleges and universities, online learning has begun to traverse a wider range of age groups. However, traditional F2F classes are still more beneficial for learners that are not so self‐sufficient and lack discipline in working through the class material in the required time frame (Arias et al., 2018 ).

For the purpose of this literature review, both pure online and blended learning are considered to be online learning because much of the evidence in the literature compares these two types against the traditional F2F learning. The debate in the literature surrounding online learning versus F2F teaching continues to be a contentious one. A review of the literature reveals mixed findings when comparing the efficacy of online learning on student performance in relation to the traditional F2F medium of instruction (Lundberg et al., 2008 ; Nguyen, 2015 ). A number of studies conducted Before the 2000s find what is known today in the empirical literature as the “No Significant Difference” phenomenon (Russell & International Distance Education Certificate Center (IDECC), 1999 ). The seminal work from Russell and IDECC ( 1999 ) involved over 350 comparative studies on online/distance learning versus F2F learning, dating back to 1928. The author finds no significant difference overall between online and traditional F2F classroom education outcomes. Subsequent studies that followed find similar “no significant difference” outcomes (Arbaugh, 2000 ; Fallah & Ubell, 2000 ; Freeman & Capper, 1999 ; Johnson et al., 2000 ; Neuhauser, 2002 ). While Bernard et al. ( 2004 ) also find that overall there is no significant difference in achievement between online education and F2F education, the study does find significant heterogeneity in student performance for different activities. The findings show that students in F2F classes outperform the students participating in synchronous online classes (i.e. classes that require online students to participate in live sessions at specific times). However, asynchronous online classes (i.e. students access class materials at their own time online) outperform F2F classes.

More recent studies find significant results for online learning outcomes in relation to F2F outcomes. On the one hand, Shachar and Yoram ( 2003 ) and Shachar and Neumann ( 2010 ) conduct a meta‐analysis of studies from 1990 to 2009 and find that in 70% of the cases, students taking courses by online education outperformed students in traditionally instructed courses (i.e. F2F lectures). In addition, Navarro and Shoemaker ( 2000 ) observe that learning outcomes for online learners are as effective as or better than outcomes for F2F learners, regardless of background characteristics. In a study on computer science students, Dutton et al. ( 2002 ) find online students perform significantly better compared to the students who take the same course on campus. A meta‐analysis conducted by the US Department of Education finds that students who took all or part of their course online performed better, on average, than those taking the same course through traditional F2F instructions. The report also finds that the effect sizes are larger for studies in which the online learning was collaborative or instructor‐driven than in those studies where online learners worked independently (Means et al., 2010 ).

On the other hand, evidence by Brown and Liedholm ( 2002 ) based on test scores from macroeconomics students in the United States suggest that F2F students tend to outperform online students. These findings are supported by Coates et al. ( 2004 ) who base their study on macroeconomics students in the United States, and Xu and Jaggars ( 2014 ) who find negative effects for online students using a data set of about 500,000 courses taken by over 40,000 students in Washington. Furthermore, Almatra et al. ( 2015 ) compare overall course grades between online and F2F students for a Telecommunications course and find that F2F students significantly outperform online learning students. In an experimental study where students are randomly assigned to attend live lectures versus watching the same lectures online, Figlio et al. ( 2013 ) observe some evidence that the traditional format has a positive effect compared to online format. Interestingly, Callister and Love ( 2016 ) specifically compare the learning outcomes of online versus F2F skills‐based courses and find that F2F learners earned better outcomes than online learners even when using the same technology. This study highlights that some of the inconsistencies that we find in the results comparing online to F2F learning might be influenced by the nature of the course: theory‐based courses might be less impacted by in‐person interaction than skills‐based courses.

The fact that the reviewed studies on the effects of F2F versus online learning on student performance have been mainly focused in developed countries indicates the dearth of similar studies being conducted in developing countries. This gap in the literature may also highlight a salient point: online learning is still relatively underexplored in developing countries. The lockdown in South Africa therefore provides us with an opportunity to contribute to the existing literature from a developing country context.

2. CONTEXT OF STUDY

South Africa went into national lockdown in March 2020 due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Like most universities in the country, the first semester for undergraduate courses at the University of Pretoria had already been running since the start of the academic year in February. Before the pandemic, a number of F2F lectures and assessments had already been conducted in most courses. The nationwide lockdown forced the university, which was mainly in‐person teaching, to move to full online learning for the remainder of the semester. This forced shift from F2F teaching to online learning allows us to investigate the changes in students' performance.

Before lockdown, classes were conducted on campus. During lockdown, these live classes were moved to an online platform, Blackboard Collaborate, which could be accessed by all registered students on the university intranet (“ClickUP”). However, these live online lectures involve substantial internet data costs for students. To ensure access to course content for those students who were unable to attend the live online lectures due to poor internet connections or internet data costs, several options for accessing course content were made available. These options included prerecorded narrated slides (which required less usage of internet data), recordings of the live online lectures, PowerPoint slides with explanatory notes and standard PDF lecture slides.

At the same time, the university managed to procure and loan out laptops to a number of disadvantaged students, and negotiated with major mobile internet data providers in the country for students to have free access to study material through the university's “connect” website (also referred to as the zero‐rated website). However, this free access excluded some video content and live online lectures (see Table 1 ). The university also provided between 10 and 20 gigabytes of mobile internet data per month, depending on the network provider, sent to students' mobile phones to assist with internet data costs.

Sites available on zero‐rated website

Note : The table summarizes the sites that were available on the zero‐rated website and those that incurred data costs.

High data costs continue to be a contentious issue in Africa where average incomes are low. Gilbert ( 2019 ) reports that South Africa ranked 16th of the 45 countries researched in terms of the most expensive internet data in Africa, at US$6.81 per gigabyte, in comparison to other Southern African countries such as Mozambique (US$1.97), Zambia (US$2.70), and Lesotho (US$4.09). Internet data prices have also been called into question in South Africa after the Competition Commission published a report from its Data Services Market Inquiry calling the country's internet data pricing “excessive” (Gilbert, 2019 ).

3. EMPIRICAL APPROACH

We use a sample of 395 s‐year students taking a macroeconomics module in the Economics department to compare the effects of F2F and online learning on students' performance using a range of assessments. The module was an introduction to the application of theoretical economic concepts. The content was both theory‐based (developing economic growth models using concepts and equations) and skill‐based (application involving the collection of data from online data sources and analyzing the data using statistical software). Both individual and group assignments formed part of the assessments. Before the end of the semester, during lockdown in June 2020, we asked the students to complete a survey with questions related to the transition from F2F to online learning and the difficulties that they may have faced. For example, we asked the students: (i) how easy or difficult they found the transition from F2F to online lectures; (ii) what internet options were available to them and which they used the most to access the online prescribed work; (iii) what format of content they accessed and which they preferred the most (i.e. self‐study material in the form of PDF and PowerPoint slides with notes vs. assisted study with narrated slides and lecture recordings); (iv) what difficulties they faced accessing the live online lectures, to name a few. Figure 1 summarizes the key survey questions that we asked the students regarding their transition from F2F to online learning.

Summary of survey data

Before the lockdown, the students had already attended several F2F classes and completed three assessments. We are therefore able to create a dependent variable that is comprised of the average grades of three assignments taken before lockdown and the average grades of three assignments taken after the start of the lockdown for each student. Specifically, we use the difference between the post‐ and pre‐lockdown average grades as the dependent variable. However, the number of student observations dropped to 275 due to some students missing one or more of the assessments. The lecturer, content and format of the assessments remain similar across the module. We estimate the following equation using ordinary least squares (OLS) with robust standard errors:

where Y i is the student's performance measured by the difference between the post and pre‐lockdown average grades. B represents the vector of determinants that measure the difficulty faced by students to transition from F2F to online learning. This vector includes access to the internet, study material preferred, quality of the online live lecture sessions and pre‐lockdown class attendance. X is the vector of student demographic controls such as race, gender and an indicator if the student's perceived family income is below average. The ε i is unobserved student characteristics.

4. ANALYSIS

4.1. descriptive statistics.

Table 2 gives an overview of the sample of students. We find that among the black students, a higher proportion of students reported finding the transition to online learning more difficult. On the other hand, more white students reported finding the transition moderately easy, as did the other races. According to Coetzee ( 2014 ), the quality of schools can vary significantly between higher income and lower‐income areas, with black South Africans far more likely to live in lower‐income areas with lower quality schools than white South Africans. As such, these differences in quality of education from secondary schooling can persist at tertiary level. Furthermore, persistent income inequality between races in South Africa likely means that many poorer black students might not be able to afford wifi connections or large internet data bundles which can make the transition difficult for black students compared to their white counterparts.

Descriptive statistics

Notes : The transition difficulty variable was ordered 1: Very Easy; 2: Moderately Easy; 3: Difficult; and 4: Impossible. Since we have few responses to the extremes, we combined Very Easy and Moderately as well as Difficult and Impossible to make the table easier to read. The table with a full breakdown is available upon request.

A higher proportion of students reported that wifi access made the transition to online learning moderately easy. However, relatively more students reported that mobile internet data and accessing the zero‐rated website made the transition difficult. Surprisingly, not many students made use of the zero‐rated website which was freely available. Figure 2 shows that students who reported difficulty transitioning to online learning did not perform as well in online learning versus F2F when compared to those that found it less difficult to transition.

Transition from F2F to online learning.

Notes : This graph shows the students' responses to the question “How easy did you find the transition from face‐to‐face lectures to online lectures?” in relation to the outcome variable for performance

In Figure 3 , the kernel density shows that students who had access to wifi performed better than those who used mobile internet data or the zero‐rated data.

Access to online learning.

Notes : This graph shows the students' responses to the question “What do you currently use the most to access most of your prescribed work?” in relation to the outcome variable for performance

The regression results are reported in Table 3 . We find that the change in students' performance from F2F to online is negatively associated with the difficulty they faced in transitioning from F2F to online learning. According to student survey responses, factors contributing to difficulty in transitioning included poor internet access, high internet data costs and lack of equipment such as laptops or tablets to access the study materials on the university website. Students who had access to wifi (i.e. fixed wireless broadband, Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line (ADSL) or optic fiber) performed significantly better, with on average 4.5 points higher grade, in relation to students that had to use mobile internet data (i.e. personal mobile internet data, wifi at home using mobile internet data, or hotspot using mobile internet data) or the zero‐rated website to access the study materials. The insignificant results for the zero‐rated website are surprising given that the website was freely available and did not incur any internet data costs. However, most students in this sample complained that the internet connection on the zero‐rated website was slow, especially in uploading assignments. They also complained about being disconnected when they were in the middle of an assessment. This may have discouraged some students from making use of the zero‐rated website.

Results: Predictors for student performance using the difference on average assessment grades between pre‐ and post‐lockdown

Coefficients reported. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

∗∗∗ p < .01.

Students who expressed a preference for self‐study approaches (i.e. reading PDF slides or PowerPoint slides with explanatory notes) did not perform as well, on average, as students who preferred assisted study (i.e. listening to recorded narrated slides or lecture recordings). This result is in line with Means et al. ( 2010 ), where student performance was better for online learning that was collaborative or instructor‐driven than in cases where online learners worked independently. Interestingly, we also observe that the performance of students who often attended in‐person classes before the lockdown decreased. Perhaps these students found the F2F lectures particularly helpful in mastering the course material. From the survey responses, we find that a significant proportion of the students (about 70%) preferred F2F to online lectures. This preference for F2F lectures may also be linked to the factors contributing to the difficulty some students faced in transitioning to online learning.

We find that the performance of low‐income students decreased post‐lockdown, which highlights another potential challenge to transitioning to online learning. The picture and sound quality of the live online lectures also contributed to lower performance. Although this result is not statistically significant, it is worth noting as the implications are linked to the quality of infrastructure currently available for students to access online learning. We find no significant effects of race on changes in students' performance, though males appeared to struggle more with the shift to online teaching than females.

For the robustness check in Table 4 , we consider the average grades of the three assignments taken after the start of the lockdown as a dependent variable (i.e. the post‐lockdown average grades for each student). We then include the pre‐lockdown average grades as an explanatory variable. The findings and overall conclusions in Table 4 are consistent with the previous results.

Robustness check: Predictors for student performance using the average assessment grades for post‐lockdown

As a further robustness check in Table 5 , we create a panel for each student across the six assignment grades so we can control for individual heterogeneity. We create a post‐lockdown binary variable that takes the value of 1 for the lockdown period and 0 otherwise. We interact the post‐lockdown dummy variable with a measure for transition difficulty and internet access. The internet access variable is an indicator variable for mobile internet data, wifi, or zero‐rated access to class materials. The variable wifi is a binary variable taking the value of 1 if the student has access to wifi and 0 otherwise. The zero‐rated variable is a binary variable taking the value of 1 if the student used the university's free portal access and 0 otherwise. We also include assignment and student fixed effects. The results in Table 5 remain consistent with our previous findings that students who had wifi access performed significantly better than their peers.

Interaction model

Notes : Coefficients reported. Robust standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is the assessment grades for each student on each assignment. The number of observations include the pre‐post number of assessments multiplied by the number of students.

6. CONCLUSION

The Covid‐19 pandemic left many education institutions with no option but to transition to online learning. The University of Pretoria was no exception. We examine the effect of transitioning to online learning on the academic performance of second‐year economic students. We use assessment results from F2F lectures before lockdown, and online lectures post lockdown for the same group of students, together with responses from survey questions. We find that the main contributor to lower academic performance in the online setting was poor internet access, which made transitioning to online learning more difficult. In addition, opting to self‐study (read notes instead of joining online classes and/or watching recordings) did not help the students in their performance.

The implications of the results highlight the need for improved quality of internet infrastructure with affordable internet data pricing. Despite the university's best efforts not to leave any student behind with the zero‐rated website and free monthly internet data, the inequality dynamics in the country are such that invariably some students were negatively affected by this transition, not because the student was struggling academically, but because of inaccessibility of internet (wifi). While the zero‐rated website is a good collaborative initiative between universities and network providers, the infrastructure is not sufficient to accommodate mass students accessing it simultaneously.

This study's findings may highlight some shortcomings in the academic sector that need to be addressed by both the public and private sectors. There is potential for an increase in the digital divide gap resulting from the inequitable distribution of digital infrastructure. This may lead to reinforcement of current inequalities in accessing higher education in the long term. To prepare the country for online learning, some considerations might need to be made to make internet data tariffs more affordable and internet accessible to all. We hope that this study's findings will provide a platform (or will at least start the conversation for taking remedial action) for policy engagements in this regard.

We are aware of some limitations presented by our study. The sample we have at hand makes it difficult to extrapolate our findings to either all students at the University of Pretoria or other higher education students in South Africa. Despite this limitation, our findings highlight the negative effect of the digital divide on students' educational outcomes in the country. The transition to online learning and the high internet data costs in South Africa can also have adverse learning outcomes for low‐income students. With higher education institutions, such as the University of Pretoria, integrating online teaching to overcome the effect of the Covid‐19 pandemic, access to stable internet is vital for students' academic success.

It is also important to note that the data we have at hand does not allow us to isolate wifi's causal effect on students' performance post‐lockdown due to two main reasons. First, wifi access is not randomly assigned; for instance, there is a high chance that students with better‐off family backgrounds might have better access to wifi and other supplementary infrastructure than their poor counterparts. Second, due to the university's data access policy and consent, we could not merge the data at hand with the student's previous year's performance. Therefore, future research might involve examining the importance of these elements to document the causal impact of access to wifi on students' educational outcomes in the country.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the helpful comments received from the editor, the anonymous reviewers, and Elizabeth Asiedu.

Chisadza, C. , Clance, M. , Mthembu, T. , Nicholls, N. , & Yitbarek, E. (2021). Online and face‐to‐face learning: Evidence from students’ performance during the Covid‐19 pandemic . Afr Dev Rev , 33 , S114–S125. 10.1111/afdr.12520 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

1 https://mybroadband.co.za/news/cellular/309693-mobile-data-prices-south-africa-vs-the-world.html .

2 The 4IR is currently characterized by increased use of new technologies, such as advanced wireless technologies, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, robotics, among others. This era has also facilitated the use of different online learning platforms ( https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-fourth-industrialrevolution-and-digitization-will-transform-africa-into-a-global-powerhouse/ ).

3 Note that we control for income, but it is plausible to assume other unobservable factors such as parental preference and parenting style might also affect access to the internet of students.

- Almatra, O. , Johri, A. , Nagappan, K. , & Modanlu, A. (2015). An empirical study of face‐to‐face and distance learning sections of a core telecommunication course (Conference Proceedings Paper No. 12944). 122nd ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Seattle, Washington State.

- Anyanwu, J. C. (2013). Characteristics and macroeconomic determinants of youth employment in Africa . African Development Review , 25 ( 2 ), 107–129. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anyanwu, J. C. (2016). Accounting for gender equality in secondary school enrolment in Africa: Accounting for gender equality in secondary school enrolment . African Development Review , 28 ( 2 ), 170–191. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arbaugh, J. (2000). Virtual classroom versus physical classroom: An exploratory study of class discussion patterns and student learning in an asynchronous internet‐based MBA course . Journal of Management Education , 24 ( 2 ), 213–233. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arias, J. J. , Swinton, J. , & Anderson, K. (2018). On‐line vs. face‐to‐face: A comparison of student outcomes with random assignment . e‐Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, , 12 ( 2 ), 1–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard, R. M. , Abrami, P. C. , Lou, Y. , Borokhovski, E. , Wade, A. , Wozney, L. , Wallet, P. A. , Fiset, M. , & Huang, B. (2004). How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta‐analysis of the empirical literature . Review of Educational Research , 74 ( 3 ), 379–439. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown, B. , & Liedholm, C. (2002). Can web courses replace the classroom in principles of microeconomics? American Economic Review , 92 ( 2 ), 444–448. [ Google Scholar ]

- Callister, R. R. , & Love, M. S. (2016). A comparison of learning outcomes in skills‐based courses: Online versus face‐to‐face formats . Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education , 14 ( 2 ), 243–256. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coates, D. , Humphreys, B. R. , Kane, J. , & Vachris, M. A. (2004). “No significant distance” between face‐to‐face and online instruction: Evidence from principles of economics . Economics of Education Review , 23 ( 5 ), 533–546. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coetzee, M. (2014). School quality and the performance of disadvantaged learners in South Africa (Working Paper No. 22). University of Stellenbosch Economics Department, Stellenbosch

- Dutton, J. , Dutton, M. , & Perry, J. (2002). How do online students differ from lecture students? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks , 6 ( 1 ), 1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Emediegwu, L. (2021). Does educational investment enhance capacity development for Nigerian youths? An autoregressive distributed lag approach . African Development Review , 32 ( S1 ), S45–S53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fallah, M. H. , & Ubell, R. (2000). Blind scores in a graduate test. Conventional compared with web‐based outcomes . ALN Magazine , 4 ( 2 ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Figlio, D. , Rush, M. , & Yin, L. (2013). Is it live or is it internet? Experimental estimates of the effects of online instruction on student learning . Journal of Labor Economics , 31 ( 4 ), 763–784. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman, M. A. , & Capper, J. M. (1999). Exploiting the web for education: An anonymous asynchronous role simulation . Australasian Journal of Educational Technology , 15 ( 1 ), 95–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert, P. (2019). The most expensive data prices in Africa . Connecting Africa. https://www.connectingafrica.com/author.asp?section_id=761%26doc_id=756372

- Glick, P. , Randriamamonjy, J. , & Sahn, D. (2009). Determinants of HIV knowledge and condom use among women in Madagascar: An analysis using matched household and community data . African Development Review , 21 ( 1 ), 147–179. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gyimah‐Brempong, K. (2011). Education and economic development in Africa . African Development Review , 23 ( 2 ), 219–236. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson, S. , Aragon, S. , Shaik, N. , & Palma‐Rivas, N. (2000). Comparative analysis of learner satisfaction and learning outcomes in online and face‐to‐face learning environments . Journal of Interactive Learning Research , 11 ( 1 ), 29–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lundberg, J. , Merino, D. , & Dahmani, M. (2008). Do online students perform better than face‐to‐face students? Reflections and a short review of some empirical findings . Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento , 5 ( 1 ), 35–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Means, B. , Toyama, Y. , Murphy, R. , Bakia, M. , & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence‐based practices in online learning: A meta‐analysis and review of online learning studies (Report No. ed‐04‐co‐0040 task 0006). U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development, Washington DC.

- Navarro, P. (2000). Economics in the cyber‐classroom . Journal of Economic Perspectives , 14 ( 2 ), 119–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Navarro, P. , & Shoemaker, J. (2000). Performance and perceptions of distance learners in cyberspace . American Journal of Distance Education , 14 ( 2 ), 15–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Neuhauser, C. (2002). Learning style and effectiveness of online and face‐to‐face instruction . American Journal of Distance Education , 16 ( 2 ), 99–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nguyen, T. (2015). The effectiveness of online learning: Beyond no significant difference and future horizons . MERLOT Journal of Online Teaching and Learning , 11 ( 2 ), 309–319. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paechter, M. , & Maier, B. (2010). Online or face‐to‐face? Students' experiences and preferences in e‐learning . Internet and Higher Education , 13 ( 4 ), 292–297. [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell, T. L. , & International Distance Education Certificate Center (IDECC) (1999). The no significant difference phenomenon: A comparative research annotated bibliography on technology for distance education: As reported in 355 research reports, summaries and papers . North Carolina State University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shachar, M. , & Neumann, Y. (2010). Twenty years of research on the academic performance differences between traditional and distance learning: Summative meta‐analysis and trend examination . MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching , 6 ( 2 ), 318–334. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shachar, M. , & Yoram, N. (2003). Differences between traditional and distance education academic performances: A meta‐analytic approach . International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning , 4 ( 2 ), 1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tchamyou, V. S. , Asongu, S. , & Odhiambo, N. (2019). The role of ICT in modulating the effect of education and lifelong learning on income inequality and economic growth in Africa . African Development Review , 31 ( 3 ), 261–274. [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu, D. , & Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Performance gaps between online and face‐to‐face courses: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas . The Journal of Higher Education , 85 ( 5 ), 633–659. [ Google Scholar ]

Advertisement

A Study on the Online-Offline and Blended Learning Methods

- Article of professional interests

- Published: 04 July 2022

- Volume 103 , pages 1373–1382, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Deepti Sharma 1 ,

- Ajay K. Sood 1 ,

- Preethi S. H. Darius 2 ,

- Edison Gundabattini 3 ,

- S. Darius Gnanaraj ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5321-5775 3 &

- A. Joseph Jeyapaul 4

12k Accesses

7 Citations

Explore all metrics

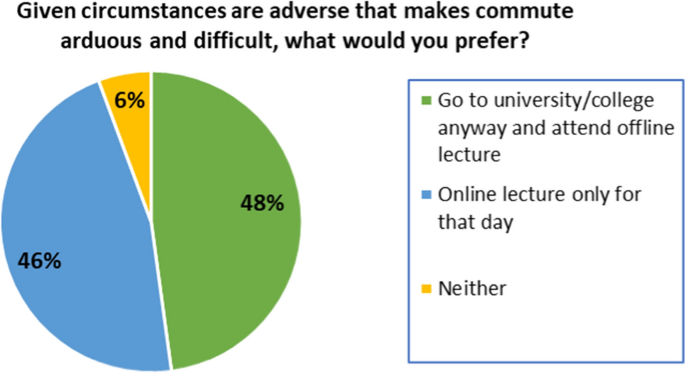

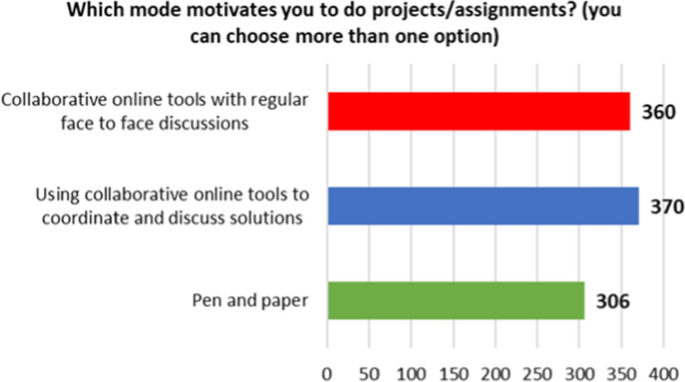

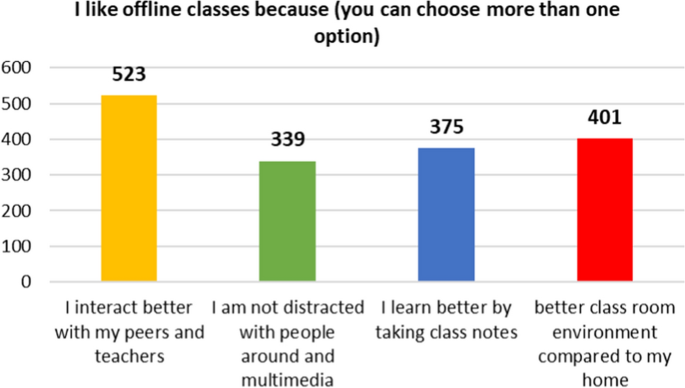

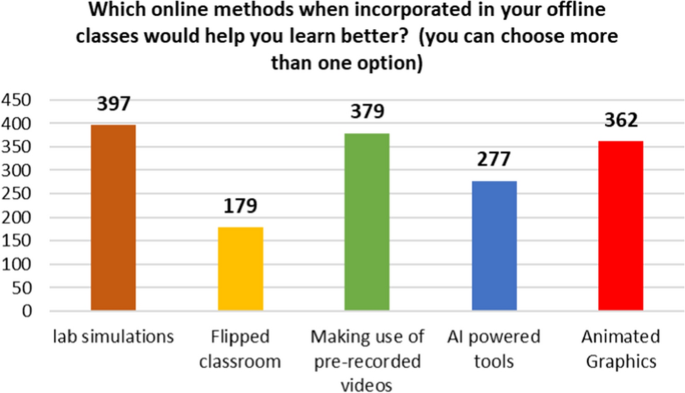

The education sector is witnessing a paradigm shift with the rapid and ongoing technological advancements. The online, offline, and blended modes of learning continue to evolve with time. The purpose of this survey is to collect students’ responses to understand their perspectives on the different modes of learning. The advantages, challenges, and requirements for conducting classes through online, offline, and blended learning methods are discussed. A questionnaire was designed, and a survey was conducted among undergraduate engineering students. The questions are carefully planned to understand the choice of students while selecting different modes of learning, various activities and tools, and the reasons for their preferences. 654 students took part in the survey and shared their feedback. The advantages and disadvantages of online and offline learning are presented. A chi-square test was conducted, and the association between the two questions is shown to be significant. Suggestions for enhancing teaching and learning based on the findings of the survey help faculty members to plan the teaching methodology to suit the requirements of students.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

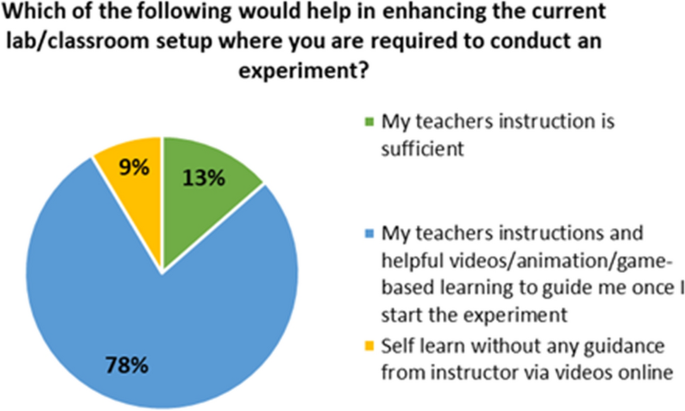

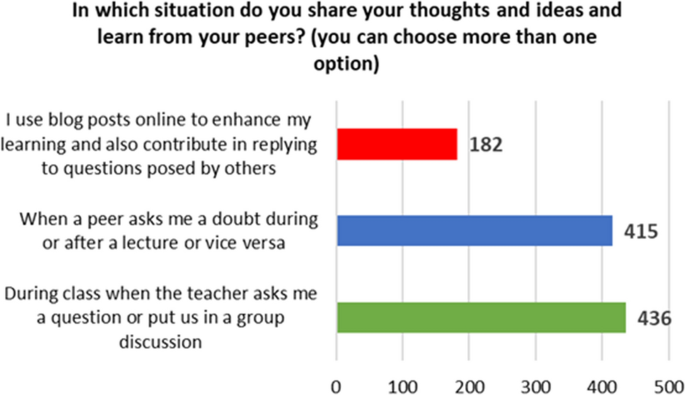

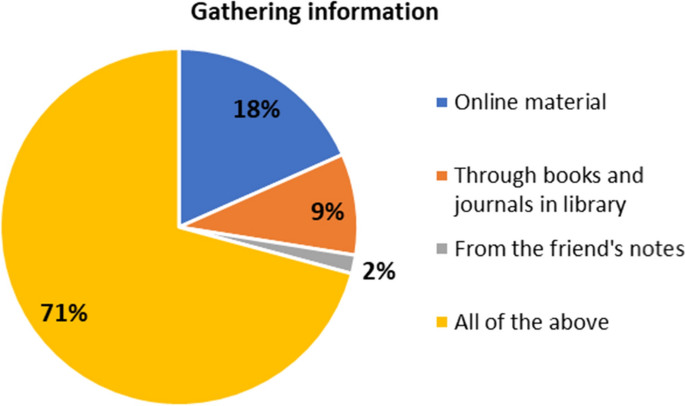

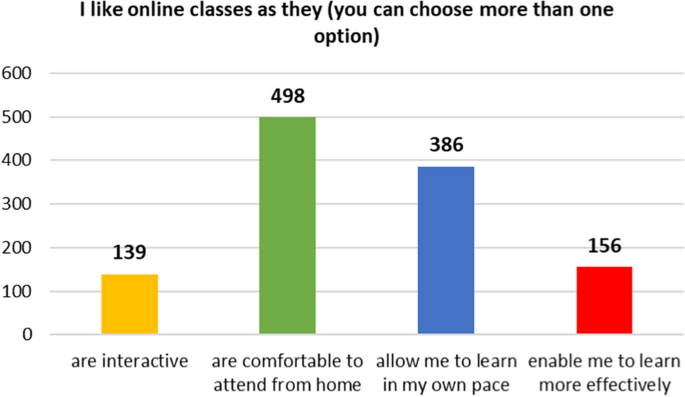

Learning is a dynamic phenomenon and it is evolved continually over the years. The effectiveness of learning depends on the methodology adopted. The methodology or the pedagogy depends on the skillsets that are expected to be acquired by the students. The COVID-19 pandemic has given an opportunity to experience and assess various online teaching and evaluation tools. In this the stake holders are students, teachers and institutional administrators. Chang et al. [ 1 ] had contrasted the physical classroom learning efficacy and online learning to estimate and enhance the quality of learning. Both the methods of learning were surveyed among the students, and results showed that the learning efficacy of online class learning was better than that of physical classroom learning. Survey results on the contrary indicated that the suitability and fairness of physical classroom evaluation were better than that of online examination. The students across various schools expressed their learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic period were to some extent effective and engaging. The study by Singh et al. emphasized the thrust to build an apt infrastructure and capacity building to support hybrid and blended learning methods. The capacity building also included familiarizing the faculty members with the various online learning methods and e-Learning tools. The study by Singh et al. suggested that both the learners and the teachers are to make use of the innovative technology to enable effective teaching and engaged learning [ 2 ]. Ghosh [ 3 ] presented an intelligent tutoring system (ITS) that behaves like a real teacher by having the dynamic response and dynamic review of the performance of students and their level of understanding. In the backdrop of COVID-19 and its multiple variants, the challenge was to design appropriate educational technologies to improve learning efficiency [ 4 , 5 ]. Darius et al. [ 6 ] found that animations, digital collaborations with fellow students, video lectures delivered by the same faculty, online quizzes, student version software, online interaction with faculty, and online materials provided by the faculty promote effective online learning.

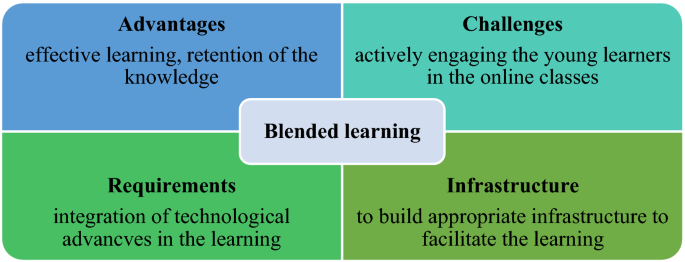

A study conducted by Michalíková and Povinský, Matej Bel University concluded that blended learning was one of the best ways of learning during this pandemic period [ 7 ]. The conclusions of a study conducted by Hysaj in Albania motivate the researchers to bring out more research on the employment of various technological tools to raise young learners' lively involvement in online learning [ 8 ]. Online learning tools provided a good learning space for learners to learn independently. Also, the proposed teaching model would enhance the students’ knowledge retention in comparison to traditional classroom learning. Hence, the proposed model proved to be feasible and effective although it requires necessary capacity-building measures in place, as shown in Fig. 1 [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. In all the e-learning, hybrid learning, and blended learning strategies, interactions between students and teachers are vital apart from the appropriate online settings. Nortvig et al. indicated that the designed influences between online and offline activities as well as between campus-related and practice-related activities are crucial factors for effective learning [ 12 ].

Employing Blended learning in the learning environment

This paper reports the outcome of a survey carried out among undergraduate students pursuing an engineering degree. The responses given by students are presented and discussed in the following sections. The comments and suggestions given in the last section are useful to faculty members in designing their teaching pedagogy to suit the requirements of students to improve the quality of teaching–learning.

Methodology