Literary Devices & Terms

An acrostic is a piece of writing in which a particular set of letters—typically the first letter of each line, word, or paragraph—spells out a word or phrase with special significance to the text. Acrostics... (read full acrostic explanation with examples) An acrostic is a piece of writing in which a particular set of letters—typically the first letter of each line,... (read more)

An allegory is a work that conveys a hidden meaning—usually moral, spiritual, or political—through the use of symbolic characters and events. The story of "The Tortoise and The Hare" is a well-known allegory with a... (read full allegory explanation with examples) An allegory is a work that conveys a hidden meaning—usually moral, spiritual, or political—through the use of symbolic characters and... (read more)

Alliteration is a figure of speech in which the same sound repeats in a group of words, such as the “b” sound in: “Bob brought the box of bricks to the basement.” The repeating sound... (read full alliteration explanation with examples) Alliteration is a figure of speech in which the same sound repeats in a group of words, such as the... (read more)

In literature, an allusion is an unexplained reference to someone or something outside of the text. Writers commonly allude to other literary works, famous individuals, historical events, or philosophical ideas, and they do so in... (read full allusion explanation with examples) In literature, an allusion is an unexplained reference to someone or something outside of the text. Writers commonly allude to... (read more)

An anachronism is a person or a thing placed in the wrong time period. For instance, if a novel set in Medieval England featured a trip to a movie-theater, that would be an anachronism. Although... (read full anachronism explanation with examples) An anachronism is a person or a thing placed in the wrong time period. For instance, if a novel set... (read more)

Anadiplosis is a figure of speech in which a word or group of words located at the end of one clause or sentence is repeated at or near the beginning of the following clause or... (read full anadiplosis explanation with examples) Anadiplosis is a figure of speech in which a word or group of words located at the end of one... (read more)

An analogy is a comparison that aims to explain a thing or idea by likening it to something else. For example, a career coach might say, "Being the successful boss or CEO of a company... (read full analogy explanation with examples) An analogy is a comparison that aims to explain a thing or idea by likening it to something else. For... (read more)

An anapest is a three-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which two unstressed syllables are followed by a stressed syllable. The word "understand" is an anapest, with the unstressed syllables of "un" and "der" followed... (read full anapest explanation with examples) An anapest is a three-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which two unstressed syllables are followed by a stressed syllable.... (read more)

Anaphora is a figure of speech in which words repeat at the beginning of successive clauses, phrases, or sentences. For example, Martin Luther King's famous "I Have a Dream" speech contains anaphora: "So let freedom... (read full anaphora explanation with examples) Anaphora is a figure of speech in which words repeat at the beginning of successive clauses, phrases, or sentences. For... (read more)

An antagonist is usually a character who opposes the protagonist (or main character) of a story, but the antagonist can also be a group of characters, institution, or force against which the protagonist must contend.... (read full antagonist explanation with examples) An antagonist is usually a character who opposes the protagonist (or main character) of a story, but the antagonist can... (read more)

Antanaclasis is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated within a sentence, but the word or phrase means something different each time it appears. A famous example of antanaclasis is... (read full antanaclasis explanation with examples) Antanaclasis is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated within a sentence, but the word... (read more)

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics, emotions, and behaviors to animals or other non-human things (including objects, plants, and supernatural beings). Some famous examples of anthropomorphism include Winnie the Pooh, the Little Engine that Could, and Simba from... (read full anthropomorphism explanation with examples) Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics, emotions, and behaviors to animals or other non-human things (including objects, plants, and supernatural beings). Some famous... (read more)

Antimetabole is a figure of speech in which a phrase is repeated, but with the order of words reversed. John F. Kennedy's words, "Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you... (read full antimetabole explanation with examples) Antimetabole is a figure of speech in which a phrase is repeated, but with the order of words reversed. John... (read more)

Antithesis is a figure of speech that juxtaposes two contrasting or opposing ideas, usually within parallel grammatical structures. For instance, Neil Armstrong used antithesis when he stepped onto the surface of the moon in 1969... (read full antithesis explanation with examples) Antithesis is a figure of speech that juxtaposes two contrasting or opposing ideas, usually within parallel grammatical structures. For instance,... (read more)

An aphorism is a saying that concisely expresses a moral principle or an observation about the world, presenting it as a general or universal truth. The Rolling Stones are responsible for penning one of the... (read full aphorism explanation with examples) An aphorism is a saying that concisely expresses a moral principle or an observation about the world, presenting it as... (read more)

Aphorismus is a type of figure of speech that calls into question the way a word is used. Aphorismus is used not to question the meaning of a word, but whether it is actually appropriate... (read full aphorismus explanation with examples) Aphorismus is a type of figure of speech that calls into question the way a word is used. Aphorismus is... (read more)

Aporia is a rhetorical device in which a speaker expresses uncertainty or doubt—often pretended uncertainty or doubt—about something, usually as a way of proving a point. An example of aporia is the famous Elizabeth Barrett... (read full aporia explanation with examples) Aporia is a rhetorical device in which a speaker expresses uncertainty or doubt—often pretended uncertainty or doubt—about something, usually as... (read more)

Apostrophe is a figure of speech in which a speaker directly addresses someone (or something) that is not present or cannot respond in reality. The entity being addressed can be an absent, dead, or imaginary... (read full apostrophe explanation with examples) Apostrophe is a figure of speech in which a speaker directly addresses someone (or something) that is not present or... (read more)

Assonance is a figure of speech in which the same vowel sound repeats within a group of words. An example of assonance is: "Who gave Newt and Scooter the blue tuna? It was too soon!" (read full assonance explanation with examples) Assonance is a figure of speech in which the same vowel sound repeats within a group of words. An example... (read more)

An asyndeton (sometimes called asyndetism) is a figure of speech in which coordinating conjunctions—words such as "and", "or", and "but" that join other words or clauses in a sentence into relationships of equal importance—are omitted.... (read full asyndeton explanation with examples) An asyndeton (sometimes called asyndetism) is a figure of speech in which coordinating conjunctions—words such as "and", "or", and "but"... (read more)

A ballad is a type of poem that tells a story and was traditionally set to music. English language ballads are typically composed of four-line stanzas that follow an ABCB rhyme scheme. (read full ballad explanation with examples) A ballad is a type of poem that tells a story and was traditionally set to music. English language ballads... (read more)

A ballade is a form of lyric poetry that originated in medieval France. Ballades follow a strict rhyme scheme ("ababbcbc"), and typically have three eight-line stanzas followed by a shorter four-line stanza called an envoi.... (read full ballade explanation with examples) A ballade is a form of lyric poetry that originated in medieval France. Ballades follow a strict rhyme scheme ("ababbcbc"),... (read more)

Bildungsroman is a genre of novel that shows a young protagonist's journey from childhood to adulthood (or immaturity to maturity), with a focus on the trials and misfortunes that affect the character's growth. (read full bildungsroman explanation with examples) Bildungsroman is a genre of novel that shows a young protagonist's journey from childhood to adulthood (or immaturity to maturity),... (read more)

Blank verse is the name given to poetry that lacks rhymes but does follow a specific meter—a meter that is almost always iambic pentameter. Blank verse was particularly popular in English poetry written between the... (read full blank verse explanation with examples) Blank verse is the name given to poetry that lacks rhymes but does follow a specific meter—a meter that is... (read more)

A cacophony is a combination of words that sound harsh or unpleasant together, usually because they pack a lot of percussive or "explosive" consonants (like T, P, or K) into relatively little space. For instance, the... (read full cacophony explanation with examples) A cacophony is a combination of words that sound harsh or unpleasant together, usually because they pack a lot of... (read more)

A caesura is a pause that occurs within a line of poetry, usually marked by some form of punctuation such as a period, comma, ellipsis, or dash. A caesura doesn't have to be placed in... (read full caesura explanation with examples) A caesura is a pause that occurs within a line of poetry, usually marked by some form of punctuation such... (read more)

Catharsis is the process of releasing strong or pent-up emotions through art. Aristotle coined the term catharsis—which comes from the Greek kathairein meaning "to cleanse or purge"—to describe the release of emotional tension that he... (read full catharsis explanation with examples) Catharsis is the process of releasing strong or pent-up emotions through art. Aristotle coined the term catharsis—which comes from the... (read more)

Characterization is the representation of the traits, motives, and psychology of a character in a narrative. Characterization may occur through direct description, in which the character's qualities are described by a narrator, another character, or... (read full characterization explanation with examples) Characterization is the representation of the traits, motives, and psychology of a character in a narrative. Characterization may occur through... (read more)

Chiasmus is a figure of speech in which the grammar of one phrase is inverted in the following phrase, such that two key concepts from the original phrase reappear in the second phrase in inverted... (read full chiasmus explanation with examples) Chiasmus is a figure of speech in which the grammar of one phrase is inverted in the following phrase, such... (read more)

The word cinquain can refer to two different things. Historically, it referred to any stanza of five lines written in any type of verse. More recently, cinquain has come to refer to particular types of... (read full cinquain explanation with examples) The word cinquain can refer to two different things. Historically, it referred to any stanza of five lines written in... (read more)

A cliché is a phrase that, due to overuse, is seen as lacking in substance or originality. For example, telling a heartbroken friend that there are "Plenty of fish in the sea" is such a... (read full cliché explanation with examples) A cliché is a phrase that, due to overuse, is seen as lacking in substance or originality. For example, telling... (read more)

Climax is a figure of speech in which successive words, phrases, clauses, or sentences are arranged in ascending order of importance, as in "Look! Up in the sky! It's a bird! It's a plane! It's... (read full climax (figure of speech) explanation with examples) Climax is a figure of speech in which successive words, phrases, clauses, or sentences are arranged in ascending order of... (read more)

The climax of a plot is the story's central turning point—the moment of peak tension or conflict—which all the preceding plot developments have been leading up to. In a traditional "good vs. evil" story (like many superhero movies)... (read full climax (plot) explanation with examples) The climax of a plot is the story's central turning point—the moment of peak tension or conflict—which all the preceding plot... (read more)

Colloquialism is the use of informal words or phrases in writing or speech. Colloquialisms are usually defined in geographical terms, meaning that they are often defined by their use within a dialect, a regionally-defined variant... (read full colloquialism explanation with examples) Colloquialism is the use of informal words or phrases in writing or speech. Colloquialisms are usually defined in geographical terms,... (read more)

Common meter is a specific type of meter that is often used in lyric poetry. Common meter has two key traits: it alternates between lines of eight syllables and lines of six syllables, and it... (read full common meter explanation with examples) Common meter is a specific type of meter that is often used in lyric poetry. Common meter has two key... (read more)

A conceit is a fanciful metaphor, especially a highly elaborate or extended metaphor in which an unlikely, far-fetched, or strained comparison is made between two things. A famous example comes from John Donne's poem, "A... (read full conceit explanation with examples) A conceit is a fanciful metaphor, especially a highly elaborate or extended metaphor in which an unlikely, far-fetched, or strained... (read more)

Connotation is the array of emotions and ideas suggested by a word in addition to its dictionary definition. Most words carry meanings, impressions, or associations apart from or beyond their literal meaning. For example, the... (read full connotation explanation with examples) Connotation is the array of emotions and ideas suggested by a word in addition to its dictionary definition. Most words... (read more)

Consonance is a figure of speech in which the same consonant sound repeats within a group of words. An example of consonance is: "Traffic figures, on July Fourth, to be tough." (read full consonance explanation with examples) Consonance is a figure of speech in which the same consonant sound repeats within a group of words. An example... (read more)

A couplet is a unit of two lines of poetry, especially lines that use the same or similar meter, form a rhyme, or are separated from other lines by a double line break. (read full couplet explanation with examples) A couplet is a unit of two lines of poetry, especially lines that use the same or similar meter, form... (read more)

A dactyl is a three-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed syllables. The word “poetry” itself is a great example of a dactyl, with the stressed syllable... (read full dactyl explanation with examples) A dactyl is a three-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed syllables.... (read more)

Denotation is the literal meaning, or "dictionary definition," of a word. Denotation is defined in contrast to connotation, which is the array of emotions and ideas suggested by a word in addition to its dictionary... (read full denotation explanation with examples) Denotation is the literal meaning, or "dictionary definition," of a word. Denotation is defined in contrast to connotation, which is... (read more)

The dénouement is the final section of a story's plot, in which loose ends are tied up, lingering questions are answered, and a sense of resolution is achieved. The shortest and most well known dénouement, it could be... (read full dénouement explanation with examples) The dénouement is the final section of a story's plot, in which loose ends are tied up, lingering questions are answered, and... (read more)

A deus ex machina is a plot device whereby an unsolvable conflict or point of tension is suddenly resolved by the unexpected appearance of an implausible character, object, action, ability, or event. For example, if... (read full deus ex machina explanation with examples) A deus ex machina is a plot device whereby an unsolvable conflict or point of tension is suddenly resolved by... (read more)

Diacope is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated with a small number of intervening words. The first line of Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy, "Happy families are all alike;... (read full diacope explanation with examples) Diacope is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated with a small number of intervening... (read more)

Dialogue is the exchange of spoken words between two or more characters in a book, play, or other written work. In prose writing, lines of dialogue are typically identified by the use of quotation marks... (read full dialogue explanation with examples) Dialogue is the exchange of spoken words between two or more characters in a book, play, or other written work.... (read more)

Diction is a writer's unique style of expression, especially his or her choice and arrangement of words. A writer's vocabulary, use of language to produce a specific tone or atmosphere, and ability to communicate clearly... (read full diction explanation with examples) Diction is a writer's unique style of expression, especially his or her choice and arrangement of words. A writer's vocabulary,... (read more)

Dramatic irony is a plot device often used in theater, literature, film, and television to highlight the difference between a character's understanding of a given situation, and that of the audience. More specifically, in dramatic... (read full dramatic irony explanation with examples) Dramatic irony is a plot device often used in theater, literature, film, and television to highlight the difference between a... (read more)

A dynamic character undergoes substantial internal changes as a result of one or more plot developments. The dynamic character's change can be extreme or subtle, as long as his or her development is important to... (read full dynamic character explanation with examples) A dynamic character undergoes substantial internal changes as a result of one or more plot developments. The dynamic character's change... (read more)

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, especially one mourning the loss of someone who died. Elegies are defined by their subject matter, and don't have to follow any specific form in terms of... (read full elegy explanation with examples) An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, especially one mourning the loss of someone who died. Elegies are defined... (read more)

End rhyme refers to rhymes that occur in the final words of lines of poetry. For instance, these lines from Dorothy Parker's poem "Interview" use end rhyme: "The ladies men admire, I’ve heard, / Would shudder... (read full end rhyme explanation with examples) End rhyme refers to rhymes that occur in the final words of lines of poetry. For instance, these lines from... (read more)

An end-stopped line is a line of poetry in which a sentence or phrase comes to a conclusion at the end of the line. For example, the poet C.P. Cavafy uses end-stopped lines in his... (read full end-stopped line explanation with examples) An end-stopped line is a line of poetry in which a sentence or phrase comes to a conclusion at the... (read more)

Enjambment is the continuation of a sentence or clause across a line break. For example, the poet John Donne uses enjambment in his poem "The Good-Morrow" when he continues the opening sentence across the line... (read full enjambment explanation with examples) Enjambment is the continuation of a sentence or clause across a line break. For example, the poet John Donne uses... (read more)

An envoi is a brief concluding stanza at the end of a poem that can either summarize the preceding poem or serve as its dedication. The envoi tends to follow the same meter and rhyme... (read full envoi explanation with examples) An envoi is a brief concluding stanza at the end of a poem that can either summarize the preceding poem... (read more)

Epanalepsis is a figure of speech in which the beginning of a clause or sentence is repeated at the end of that same clause or sentence, with words intervening. The sentence "The king is dead,... (read full epanalepsis explanation with examples) Epanalepsis is a figure of speech in which the beginning of a clause or sentence is repeated at the end... (read more)

An epigram is a short and witty statement, usually written in verse, that conveys a single thought or observation. Epigrams typically end with a punchline or a satirical twist. (read full epigram explanation with examples) An epigram is a short and witty statement, usually written in verse, that conveys a single thought or observation. Epigrams... (read more)

An epigraph is a short quotation, phrase, or poem that is placed at the beginning of another piece of writing to encapsulate that work's main themes and to set the tone. For instance, the epigraph of Mary... (read full epigraph explanation with examples) An epigraph is a short quotation, phrase, or poem that is placed at the beginning of another piece of writing to... (read more)

Epistrophe is a figure of speech in which one or more words repeat at the end of successive phrases, clauses, or sentences. In his Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln urged the American people to ensure that,... (read full epistrophe explanation with examples) Epistrophe is a figure of speech in which one or more words repeat at the end of successive phrases, clauses,... (read more)

Epizeuxis is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated in immediate succession, with no intervening words. In the play Hamlet, when Hamlet responds to a question about what he's reading... (read full epizeuxis explanation with examples) Epizeuxis is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is repeated in immediate succession, with no intervening... (read more)

Ethos, along with logos and pathos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Ethos is an argument that appeals to the audience by emphasizing the... (read full ethos explanation with examples) Ethos, along with logos and pathos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective... (read more)

Euphony is the combining of words that sound pleasant together or are easy to pronounce, usually because they contain lots of consonants with soft or muffled sounds (like L, M, N, and R) instead of consonants with harsh, percussive sounds (like... (read full euphony explanation with examples) Euphony is the combining of words that sound pleasant together or are easy to pronounce, usually because they contain lots of consonants with soft... (read more)

Exposition is the description or explanation of background information within a work of literature. Exposition can cover characters and their relationship to one another, the setting or time and place of events, as well as... (read full exposition explanation with examples) Exposition is the description or explanation of background information within a work of literature. Exposition can cover characters and their... (read more)

An extended metaphor is a metaphor that unfolds across multiple lines or even paragraphs of a text, making use of multiple interrelated metaphors within an overarching one. So while "life is a highway" is a... (read full extended metaphor explanation with examples) An extended metaphor is a metaphor that unfolds across multiple lines or even paragraphs of a text, making use of... (read more)

An external conflict is a problem, antagonism, or struggle that takes place between a character and an outside force. External conflict drives the action of a plot forward. (read full external conflict explanation with examples) An external conflict is a problem, antagonism, or struggle that takes place between a character and an outside force. External conflict... (read more)

The falling action of a story is the section of the plot following the climax, in which the tension stemming from the story's central conflict decreases and the story moves toward its conclusion. For instance, the traditional "good... (read full falling action explanation with examples) The falling action of a story is the section of the plot following the climax, in which the tension stemming from... (read more)

Figurative language is language that contains or uses figures of speech. When people use the term "figurative language," however, they often do so in a slightly narrower way. In this narrower definition, figurative language refers... (read full figurative language explanation with examples) Figurative language is language that contains or uses figures of speech. When people use the term "figurative language," however, they... (read more)

A figure of speech is a literary device in which language is used in an unusual—or "figured"—way in order to produce a stylistic effect. Figures of speech can be broken into two main groups: figures... (read full figure of speech explanation with examples) A figure of speech is a literary device in which language is used in an unusual—or "figured"—way in order to... (read more)

A character is said to be "flat" if it is one-dimensional or lacking in complexity. Typically, flat characters can be easily and accurately described using a single word (like "bully") or one short sentence (like "A naive... (read full flat character explanation with examples) A character is said to be "flat" if it is one-dimensional or lacking in complexity. Typically, flat characters can be easily... (read more)

Foreshadowing is a literary device in which authors hint at plot developments that don't actually occur until later in the story. Foreshadowing can be achieved directly or indirectly, by making explicit statements or leaving subtle... (read full foreshadowing explanation with examples) Foreshadowing is a literary device in which authors hint at plot developments that don't actually occur until later in the... (read more)

Formal verse is the name given to rhymed poetry that uses a strict meter (a regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables). This two-line poem by Emily Dickinson is formal verse because it rhymes and... (read full formal verse explanation with examples) Formal verse is the name given to rhymed poetry that uses a strict meter (a regular pattern of stressed and... (read more)

Free verse is the name given to poetry that doesn’t use any strict meter or rhyme scheme. Because it has no set meter, poems written in free verse can have lines of any length, from... (read full free verse explanation with examples) Free verse is the name given to poetry that doesn’t use any strict meter or rhyme scheme. Because it has... (read more)

Hamartia is a literary term that refers to a tragic flaw or error that leads to a character's downfall. In the novel Frankenstein, Victor Frankenstein's arrogant conviction that he can usurp the roles of God... (read full hamartia explanation with examples) Hamartia is a literary term that refers to a tragic flaw or error that leads to a character's downfall. In... (read more)

Hubris refers to excessive pride or overconfidence, which drives a person to overstep limits in a way that leads to their downfall. In Greek mythology, the legend of Icarus involves an iconic case of hubris:... (read full hubris explanation with examples) Hubris refers to excessive pride or overconfidence, which drives a person to overstep limits in a way that leads to... (read more)

Hyperbole is a figure of speech in which a writer or speaker exaggerates for the sake of emphasis. Hyperbolic statements are usually quite obvious exaggerations intended to emphasize a point, rather than be taken literally.... (read full hyperbole explanation with examples) Hyperbole is a figure of speech in which a writer or speaker exaggerates for the sake of emphasis. Hyperbolic statements... (read more)

An iamb is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which one unstressed syllable is followed by a stressed syllable. The word "define" is an iamb, with the unstressed syllable of "de" followed by the... (read full iamb explanation with examples) An iamb is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which one unstressed syllable is followed by a stressed syllable.... (read more)

An idiom is a phrase that conveys a figurative meaning that is difficult or impossible to understand based solely on a literal interpretation of the words in the phrase. For example, saying that something is... (read full idiom explanation with examples) An idiom is a phrase that conveys a figurative meaning that is difficult or impossible to understand based solely on... (read more)

Imagery, in any sort of writing, refers to descriptive language that engages the human senses. For instance, the following lines from Robert Frost's poem "After Apple-Picking" contain imagery that engages the senses of touch, movement,... (read full imagery explanation with examples) Imagery, in any sort of writing, refers to descriptive language that engages the human senses. For instance, the following lines... (read more)

Internal rhyme is rhyme that occurs in the middle of lines of poetry, instead of at the ends of lines. A single line of poetry can contain internal rhyme (with multiple words in the same... (read full internal rhyme explanation with examples) Internal rhyme is rhyme that occurs in the middle of lines of poetry, instead of at the ends of lines.... (read more)

Irony is a literary device or event in which how things seem to be is in fact very different from how they actually are. If this seems like a loose definition, don't worry—it is. Irony is a... (read full irony explanation with examples) Irony is a literary device or event in which how things seem to be is in fact very different from how... (read more)

Juxtaposition occurs when an author places two things side by side as a way of highlighting their differences. Ideas, images, characters, and actions are all things that can be juxtaposed with one another. For example,... (read full juxtaposition explanation with examples) Juxtaposition occurs when an author places two things side by side as a way of highlighting their differences. Ideas, images,... (read more)

A kenning is a figure of speech in which two words are combined in order to form a poetic expression that refers to a person or a thing. For example, "whale-road" is a kenning for... (read full kenning explanation with examples) A kenning is a figure of speech in which two words are combined in order to form a poetic expression... (read more)

A line break is the termination of one line of poetry, and the beginning of a new line. (read full line break explanation with examples) A line break is the termination of one line of poetry, and the beginning of a new line. (read more)

Litotes is a figure of speech and a form of understatement in which a sentiment is expressed ironically by negating its contrary. For example, saying "It's not the best weather today" during a hurricane would... (read full litotes explanation with examples) Litotes is a figure of speech and a form of understatement in which a sentiment is expressed ironically by negating... (read more)

Logos, along with ethos and pathos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Logos is an argument that appeals to an audience's sense of logic... (read full logos explanation with examples) Logos, along with ethos and pathos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective... (read more)

A metaphor is a figure of speech that compares two different things by saying that one thing is the other. The comparison in a metaphor can be stated explicitly, as in the sentence "Love is... (read full metaphor explanation with examples) A metaphor is a figure of speech that compares two different things by saying that one thing is the other.... (read more)

Meter is a regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that defines the rhythm of some poetry. These stress patterns are defined in groupings, called feet, of two or three syllables. A pattern of unstressed-stressed,... (read full meter explanation with examples) Meter is a regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that defines the rhythm of some poetry. These stress patterns... (read more)

Metonymy is a type of figurative language in which an object or concept is referred to not by its own name, but instead by the name of something closely associated with it. For example, in... (read full metonymy explanation with examples) Metonymy is a type of figurative language in which an object or concept is referred to not by its own... (read more)

The mood of a piece of writing is its general atmosphere or emotional complexion—in short, the array of feelings the work evokes in the reader. Every aspect of a piece of writing can influence its mood, from the... (read full mood explanation with examples) The mood of a piece of writing is its general atmosphere or emotional complexion—in short, the array of feelings the work evokes... (read more)

A motif is an element or idea that recurs throughout a work of literature. Motifs, which are often collections of related symbols, help develop the central themes of a book or play. For example, one... (read full motif explanation with examples) A motif is an element or idea that recurs throughout a work of literature. Motifs, which are often collections of... (read more)

A narrative is an account of connected events. Two writers describing the same set of events might craft very different narratives, depending on how they use different narrative elements, such as tone or point of view. For... (read full narrative explanation with examples) A narrative is an account of connected events. Two writers describing the same set of events might craft very different narratives,... (read more)

Onomatopoeia is a figure of speech in which words evoke the actual sound of the thing they refer to or describe. The “boom” of a firework exploding, the “tick tock” of a clock, and the... (read full onomatopoeia explanation with examples) Onomatopoeia is a figure of speech in which words evoke the actual sound of the thing they refer to or... (read more)

An oxymoron is a figure of speech in which two contradictory terms or ideas are intentionally paired in order to make a point—particularly to reveal a deeper or hidden truth. The most recognizable oxymorons are... (read full oxymoron explanation with examples) An oxymoron is a figure of speech in which two contradictory terms or ideas are intentionally paired in order to... (read more)

A paradox is a figure of speech that seems to contradict itself, but which, upon further examination, contains some kernel of truth or reason. Oscar Wilde's famous declaration that "Life is much too important to be... (read full paradox explanation with examples) A paradox is a figure of speech that seems to contradict itself, but which, upon further examination, contains some kernel... (read more)

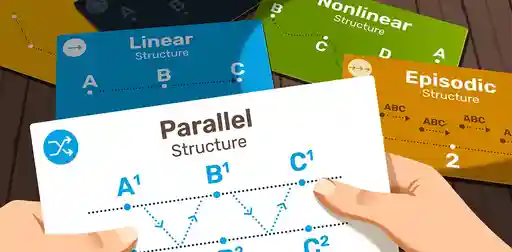

Parallelism is a figure of speech in which two or more elements of a sentence (or series of sentences) have the same grammatical structure. These "parallel" elements can be used to intensify the rhythm of... (read full parallelism explanation with examples) Parallelism is a figure of speech in which two or more elements of a sentence (or series of sentences) have... (read more)

Parataxis is a figure of speech in which words, phrases, clauses, or sentences are set next to each other so that each element is equally important. Parataxis usually involves simple sentences or phrases whose relationships... (read full parataxis explanation with examples) Parataxis is a figure of speech in which words, phrases, clauses, or sentences are set next to each other so... (read more)

A parody is a work that mimics the style of another work, artist, or genre in an exaggerated way, usually for comic effect. Parodies can take many forms, including fiction, poetry, film, visual art, and... (read full parody explanation with examples) A parody is a work that mimics the style of another work, artist, or genre in an exaggerated way, usually... (read more)

Pathetic fallacy occurs when a writer attributes human emotions to things that aren't human, such as objects, weather, or animals. It is often used to make the environment reflect the inner experience of a narrator... (read full pathetic fallacy explanation with examples) Pathetic fallacy occurs when a writer attributes human emotions to things that aren't human, such as objects, weather, or animals.... (read more)

Pathos, along with logos and ethos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Pathos is an argument that appeals to an audience's emotions. When a... (read full pathos explanation with examples) Pathos, along with logos and ethos, is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective... (read more)

Personification is a type of figurative language in which non-human things are described as having human attributes, as in the sentence, "The rain poured down on the wedding guests, indifferent to their plans." Describing the... (read full personification explanation with examples) Personification is a type of figurative language in which non-human things are described as having human attributes, as in the... (read more)

Plot is the sequence of interconnected events within the story of a play, novel, film, epic, or other narrative literary work. More than simply an account of what happened, plot reveals the cause-and-effect relationships between... (read full plot explanation with examples) Plot is the sequence of interconnected events within the story of a play, novel, film, epic, or other narrative literary... (read more)

Point of view refers to the perspective that the narrator holds in relation to the events of the story. The three primary points of view are first person, in which the narrator tells a story from... (read full point of view explanation with examples) Point of view refers to the perspective that the narrator holds in relation to the events of the story. The... (read more)

Polyptoton is a figure of speech that involves the repetition of words derived from the same root (such as "blood" and "bleed"). For instance, the question, "Who shall watch the watchmen?" is an example of... (read full polyptoton explanation with examples) Polyptoton is a figure of speech that involves the repetition of words derived from the same root (such as "blood"... (read more)

Polysyndeton is a figure of speech in which coordinating conjunctions—words such as "and," "or," and "but" that join other words or clauses in a sentence into relationships of equal importance—are used several times in close... (read full polysyndeton explanation with examples) Polysyndeton is a figure of speech in which coordinating conjunctions—words such as "and," "or," and "but" that join other words... (read more)

The protagonist of a story is its main character, who has the sympathy and support of the audience. This character tends to be involved in or affected by most of the choices or conflicts that... (read full protagonist explanation with examples) The protagonist of a story is its main character, who has the sympathy and support of the audience. This character... (read more)

A pun is a figure of speech that plays with words that have multiple meanings, or that plays with words that sound similar but mean different things. The comic novelist Douglas Adams uses both types... (read full pun explanation with examples) A pun is a figure of speech that plays with words that have multiple meanings, or that plays with words... (read more)

A quatrain is a four-line stanza of poetry. It can be a single four-line stanza, meaning that it is a stand-alone poem of four lines, or it can be a four-line stanza that makes up... (read full quatrain explanation with examples) A quatrain is a four-line stanza of poetry. It can be a single four-line stanza, meaning that it is a... (read more)

A red herring is a piece of information in a story that distracts readers from an important truth, or leads them to mistakenly expect a particular outcome. Most often, the term red herring is used to refer... (read full red herring explanation with examples) A red herring is a piece of information in a story that distracts readers from an important truth, or leads them... (read more)

In a poem or song, a refrain is a line or group of lines that regularly repeat, usually at the end of a stanza in a poem or at the end of a verse in... (read full refrain explanation with examples) In a poem or song, a refrain is a line or group of lines that regularly repeat, usually at the... (read more)

Repetition is a literary device in which a word or phrase is repeated two or more times. Repetition occurs in so many different forms that it is usually not thought of as a single figure... (read full repetition explanation with examples) Repetition is a literary device in which a word or phrase is repeated two or more times. Repetition occurs in... (read more)

A rhetorical question is a figure of speech in which a question is asked for a reason other than to get an answer—most commonly, it's asked to make a persuasive point. For example, if a... (read full rhetorical question explanation with examples) A rhetorical question is a figure of speech in which a question is asked for a reason other than to... (read more)

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in two or more words. Rhyming is particularly common in many types of poetry, especially at the ends of lines, and is a requirement in formal verse.... (read full rhyme explanation with examples) A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in two or more words. Rhyming is particularly common in many types... (read more)

A rhyme scheme is the pattern according to which end rhymes (rhymes located at the end of lines) are repeated in works poetry. Rhyme schemes are described using letters of the alphabet, such that all... (read full rhyme scheme explanation with examples) A rhyme scheme is the pattern according to which end rhymes (rhymes located at the end of lines) are repeated... (read more)

The rising action of a story is the section of the plot leading up to the climax, in which the tension stemming from the story's central conflict grows through successive plot developments. For example, in the story of "Little... (read full rising action explanation with examples) The rising action of a story is the section of the plot leading up to the climax, in which the tension stemming... (read more)

A character is said to be "round" if they are lifelike or complex. Round characters typically have fully fleshed-out and multi-faceted personalities, backgrounds, desires, and motivations. Jay Gatsby in F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby... (read full round character explanation with examples) A character is said to be "round" if they are lifelike or complex. Round characters typically have fully fleshed-out and... (read more)

Satire is the use of humor, irony, sarcasm, or ridicule to criticize something or someone. Public figures, such as politicians, are often the subject of satire, but satirists can take aim at other targets as... (read full satire explanation with examples) Satire is the use of humor, irony, sarcasm, or ridicule to criticize something or someone. Public figures, such as politicians,... (read more)

A sestet is a six-line stanza of poetry. It can be any six-line stanza—one that is, itself, a whole poem, or one that makes up a part of a longer poem. Most commonly, the term... (read full sestet explanation with examples) A sestet is a six-line stanza of poetry. It can be any six-line stanza—one that is, itself, a whole poem,... (read more)

Setting is where and when a story or scene takes place. The where can be a real place like the city of New York, or it can be an imagined location, like Middle Earth in... (read full setting explanation with examples) Setting is where and when a story or scene takes place. The where can be a real place like the... (read more)

Sibilance is a figure of speech in which a hissing sound is created within a group of words through the repetition of "s" sounds. An example of sibilance is: "Sadly, Sam sold seven venomous serpents to Sally and... (read full sibilance explanation with examples) Sibilance is a figure of speech in which a hissing sound is created within a group of words through the repetition... (read more)

A simile is a figure of speech that directly compares two unlike things. To make the comparison, similes most often use the connecting words "like" or "as," but can also use other words that indicate... (read full simile explanation with examples) A simile is a figure of speech that directly compares two unlike things. To make the comparison, similes most often... (read more)

Traditionally, slant rhyme referred to a type of rhyme in which two words located at the end of a line of poetry themselves end in similar—but not identical—consonant sounds. For instance, the words "pact" and... (read full slant rhyme explanation with examples) Traditionally, slant rhyme referred to a type of rhyme in which two words located at the end of a line... (read more)

A soliloquy is a literary device, most often found in dramas, in which a character speaks to him or herself, relating his or her innermost thoughts and feelings as if thinking aloud. In some cases,... (read full soliloquy explanation with examples) A soliloquy is a literary device, most often found in dramas, in which a character speaks to him or herself,... (read more)

A sonnet is a type of fourteen-line poem. Traditionally, the fourteen lines of a sonnet consist of an octave (or two quatrains making up a stanza of 8 lines) and a sestet (a stanza of... (read full sonnet explanation with examples) A sonnet is a type of fourteen-line poem. Traditionally, the fourteen lines of a sonnet consist of an octave (or... (read more)

A spondee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which both syllables are stressed. The word "downtown" is a spondee, with the stressed syllable of "down" followed by another stressed syllable, “town”: Down-town. (read full spondee explanation with examples) A spondee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which both syllables are stressed. The word "downtown" is a... (read more)

A stanza is a group of lines form a smaller unit within a poem. A single stanza is usually set apart from other lines or stanza within a poem by a double line break or... (read full stanza explanation with examples) A stanza is a group of lines form a smaller unit within a poem. A single stanza is usually set... (read more)

A character is said to be "static" if they do not undergo any substantial internal changes as a result of the story's major plot developments. Antagonists are often static characters, but any character in a... (read full static character explanation with examples) A character is said to be "static" if they do not undergo any substantial internal changes as a result of... (read more)

Stream of consciousness is a style or technique of writing that tries to capture the natural flow of a character's extended thought process, often by incorporating sensory impressions, incomplete ideas, unusual syntax, and rough grammar. (read full stream of consciousness explanation with examples) Stream of consciousness is a style or technique of writing that tries to capture the natural flow of a character's... (read more)

A syllogism is a three-part logical argument, based on deductive reasoning, in which two premises are combined to arrive at a conclusion. So long as the premises of the syllogism are true and the syllogism... (read full syllogism explanation with examples) A syllogism is a three-part logical argument, based on deductive reasoning, in which two premises are combined to arrive at... (read more)

Symbolism is a literary device in which a writer uses one thing—usually a physical object or phenomenon—to represent something more abstract. A strong symbol usually shares a set of key characteristics with whatever it is... (read full symbolism explanation with examples) Symbolism is a literary device in which a writer uses one thing—usually a physical object or phenomenon—to represent something more... (read more)

Synecdoche is a figure of speech in which, most often, a part of something is used to refer to its whole. For example, "The captain commands one hundred sails" is a synecdoche that uses "sails"... (read full synecdoche explanation with examples) Synecdoche is a figure of speech in which, most often, a part of something is used to refer to its... (read more)

A theme is a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature. One key characteristic of literary themes is their universality, which is to say that themes are ideas that not only... (read full theme explanation with examples) A theme is a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature. One key characteristic of literary... (read more)

The tone of a piece of writing is its general character or attitude, which might be cheerful or depressive, sarcastic or sincere, comical or mournful, praising or critical, and so on. For instance, an editorial in a newspaper... (read full tone explanation with examples) The tone of a piece of writing is its general character or attitude, which might be cheerful or depressive, sarcastic or sincere, comical... (read more)

A tragic hero is a type of character in a tragedy, and is usually the protagonist. Tragic heroes typically have heroic traits that earn them the sympathy of the audience, but also have flaws or... (read full tragic hero explanation with examples) A tragic hero is a type of character in a tragedy, and is usually the protagonist. Tragic heroes typically have... (read more)

A trochee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by an unstressed syllable. The word "poet" is a trochee, with the stressed syllable of "po" followed by the... (read full trochee explanation with examples) A trochee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by an unstressed syllable.... (read more)

Understatement is a figure of speech in which something is expressed less strongly than would be expected, or in which something is presented as being smaller, worse, or lesser than it really is. Typically, understatement is... (read full understatement explanation with examples) Understatement is a figure of speech in which something is expressed less strongly than would be expected, or in which something... (read more)

Verbal irony occurs when the literal meaning of what someone says is different from—and often opposite to—what they actually mean. When there's a hurricane raging outside and someone remarks "what lovely weather we're having," this... (read full verbal irony explanation with examples) Verbal irony occurs when the literal meaning of what someone says is different from—and often opposite to—what they actually mean.... (read more)

A villanelle is a poem of nineteen lines, and which follows a strict form that consists of five tercets (three-line stanzas) followed by one quatrain (four-line stanza). Villanelles use a specific rhyme scheme of ABA... (read full villanelle explanation with examples) A villanelle is a poem of nineteen lines, and which follows a strict form that consists of five tercets (three-line... (read more)

A zeugma is a figure of speech in which one "governing" word or phrase modifies two distinct parts of a sentence. Often, the governing word will mean something different when applied to each part, as... (read full zeugma explanation with examples) A zeugma is a figure of speech in which one "governing" word or phrase modifies two distinct parts of a... (read more)

- PDF downloads of each of the 136 Lit Terms we cover

- PDF downloads of 1916 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,380 quotes across 1916 Lit Guides

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Blog • Perfecting your Craft , Book Design

Last updated on Apr 22, 2024

60 Literary Devices With Examples: The Ultimate List

Literary devices are perhaps the greatest tools that writers have in literature. Just think — Shakespeare could have written: Everyone has a role in life.

Instead, he used a literary device and penned what is likely the most famous metaphor in literature:

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women merely players

And the rest is history.

What are literary devices?

A literary device is a writing technique that writers use to express ideas, convey meaning, and highlight important themes in a piece of text. A metaphor, like we mentioned earlier, is a famous example of a literary device.

These devices serve a wide range of purposes in literature. Some might work on an intellectual level, while others have a more emotional effect. They may also work subtly to improve the flow and pacing of your writing. No matter what, if you're looking to inject something special into your prose, literary devices are a great place to start.

How to identify literary devices

A writer using a literary device is quite different from a reader identifying it. Often, an author’s use of a literary device is subtle by design —you only feel its effect, and not its presence.

Therefore, we’ve structured this post for both purposes:

- If you’re a reader, we’ve included examples for each literary device to make it easier for you to identify them in the wild.

- If you’re a writer, we’ve included exercises for the literary devices, so that you can practice using them in your works.

Let’s get to it.

60 common literary devices, with examples

1. alliteration.

Alliteration describes a series of words in quick succession that all start with the same letter or sound. It lends a pleasing cadence to prose and Hamlet and the dollar as currency in Macbeth .

Example: “ One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die.” — “Death, Be Not Proud” by John Donne

Exercise: Pick a letter and write a sentence where every word starts with that letter or one that sounds similar.

2. Anaphora

Anaphora is the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of a series of clauses or sentences. It’s often seen in poetry and speeches, intended to provoke an emotional response in its audience.

Example: Martin Luther King’s 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech.

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.

"… and I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit together at the table of brotherhood.

"… I have a dream that little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

Exercise: Pick a famous phrase and write a paragraph elaborating on an idea, beginning each sentence with that phrase.

Similar term: repetition

3. Anastrophe

Anastrophe is a figure of speech wherein the traditional sentence structure is reversed. So a typical verb-subject-adjective sentence such as “Are you ready?” becomes a Yoda-esque adjective-verb-subject question: “Ready, are you?” Or a standard adjective-noun pairing like “tall mountain” becomes “mountain tall.”

Example: “Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing.” — “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

Exercise: Write a standard verb-subject-adjective sentence or adjective-noun pairing then flip the order to create an anastrophe. How does it change the meaning or feeling of the sentence?

4. Chiasmus

Chiasmus is when two or more parallel clauses are inverted. “Why would I do that?” you may be wondering. Well, a chiasmus might sound confusing and unnecessary in theory, but it's much more convincing in practice — and in fact, you've likely already come across it before.

Example: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” — John F. Kennedy

5. Congeries

Congeries is a fancy literary term for creating a list. The items in your list can be words, ideas, or phrases, and by displaying them this way helps prove or emphasize a point — or even create a sense of irony. Occasionally, it’s also called piling as the words are “piling up.”

Example: "Apart from better sanitation and medicine and education and irrigation and public health and roads and a freshwater system and baths and public order, what have the Romans done for us?" — Monty Python’s Life of Brian

6. Cumulative sentence

A cumulative sentence (or “loose sentence”) is one that starts with an independent clause, but then has additional or modifying clauses. They’re often used for contextual or clarifying details. This may sound complex, but even, “I ran to the store to buy milk, bread, and toilet paper” is a cumulative sentence, because the first clause, “I ran to the store,” is a complete sentence, while the rest tells us extra information about your run to the store.

Example: “It was a large bottle of gin Albert Cousins had brought to the party, yes, but it was in no way large enough to fill all the cups, and in certain cases to fill them many times over, for the more than one hundred guests, some of whom were dancing not four feet in front of him.” – Commonwealth by Ann Patchett

Example: Write three sentences that are related to each other. Can you combine the information into a cumulative sentence?

FREE RESOURCE

Literary Devices Cheatsheet

Master these 40+ devices to level up your writing skills.

7. Epistrophe

Epistrophe is the opposite of anaphora, with this time a word or phrase being repeated at the end of a sentence. Though its placement in a sentence is different it serves the same purpose—creating emphasis—as an anaphora does.

Example: “I’ll be ever’where – wherever you look. Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there . If Casy knowed, why, I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad an’ – I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry an’ they know supper’s ready. An’ when our folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build, why, I’ll be there .” — The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Similar terms: repetition, anaphora

Exercise: Write a paragraph where a phrase or a word is repeated at the end of every sentence, emphasizing the point you’re trying to make.

8. Erotesis

Erotesis is a close cousin of the rhetorical question. Rather than a question asked without expectation of an answer, this is when the question (and the asker) confidently expects a response that is either negative or affirmative.

Example: “ Do you then really think that you have committed your follies in order to spare your son them?” — Siddhartha by Herman Hesse

Similar term: rhetorical question

9. Hyperbaton

Hyperbaton is the inversion of words, phrases, or clauses in a sentence that differs from how they would normally be arranged. It comes from the Greek hyperbatos, which means “transposed” or “inverted.” While it is similar to anastrophe, it doesn’t have the same specific structure and allows you to rearrange your sentences in whatever order you want.

Example: “Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire.” — “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe

Similar terms: anastrophe, epistrophe

10. Isocolon

If you’re a neat freak who likes things just so , isocolon is the literary device for you. This is when two or more phrases or clauses have similar structure, rhythm, and even length — such that, when stacked up on top of each other, they would line up perfectly. Isocolon often crops up in brand slogans and famous sayings; the quick, balanced rhythm makes the phrase catchier and more memorable.

Example: Veni, vidi, vici (“I came, I saw, I conquered”)

11. Litotes

Litotes (pronounced lie-toe-teez ) is the signature literary device of the double negative. Writers use litotes to express certain sentiments through their opposites, by saying that that opposite is not the case. Don’t worry, it makes more sense with the examples. 😉

Examples: “You won’t be sorry” (meaning you’ll be happy); “you’re not wrong” (meaning you’re right); “I didn’t not like it” (meaning I did)

12. Malapropism

If Shakespeare is the king of metaphors, Michael Scott is the king of malapropisms . A malapropism is when similar-sounding words replace their appropriate counterparts, typically to comic effect — one of the most commonly cited is “dance a flamingo,” rather than a “flamenco.” Malapropisms are often employed in dialogue when a character flubs up their speech.

Example: “I am not to be truffled with.”

Exercise: Choose a famous or common phrase and see if you can replace a word with a similar sounding one that changes the meaning.

13. Onomatopoeia

Amusingly, onomatopoeia (itself a difficult-to-pronounce word) refers to words that sound like the thing they’re referring to. Well-known instances of onomatopoeia include whiz, buzz, snap, grunt, etc.

Example: The excellent children's book Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type . “Farmer Brown has a problem. His cows like to type. All day long he hears: Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. Clickety, clack, moo. ”

Exercise: Take some time to listen to the sounds around you and write down what you hear. Now try to use those sounds in a short paragraph or story.

14. Oxymoron

An oxymoron comes from two contradictory words that describe one thing. While juxtaposition contrasts two story elements, oxymorons are about the actual words you are using.

Example: "Parting is such sweet sorrow.” — Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. (Find 100 more examples of oxymorons here .)

Similar terms: juxtaposition, paradox

Exercise: Choose two words with opposite meanings and see if you can use them in a sentence to create a coherent oxymoron.

15. Parallelism

Parallelism is all about your sentence structure. It’s when similar ideas, sounds, phrases, or words are arranged in a way that is harmonious or creates a parallel, hence the name. It can add rhythm and meter to any piece of writing and can often be found in poetry.

Example: “ That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” — Neil Armstrong

Which famous author do you write like?

Find out which literary luminary is your stylistic soulmate. Takes one minute!

16. Polysyndeton

Instead of using a single conjunction in lengthy statements, polysyndeton uses several in succession for a dramatic effect. This one is definitely for authors looking to add a bit of artistic flair to their writing, or who are hoping to portray a particular (usually naïve) sort of voice.

Example: “Luster came away from the flower tree and we went along the fence and they stopped and we stopped and I looked through the fence while Luster was hunting in the grass.” — The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

Exercise: Write three or four independent sentences. Try combining them using conjunctions. What kind of effect does this have on the overall meaning and tone of the piece?

17. Portmanteau

A portmanteau is when two words are combined to form a new word which refers to a single concept that retains the meanings of both the original words. Modern language is full of portmanteaus. In fact, the portmanteau is itself a portmanteau. It’s a combination of the French porter (to carry) and manteau (cloak).

Example: Brunch (breakfast and lunch); cosplay (costume and roleplay); listicle (list and article); romcom (romance and comedy)

Exercise: Pick two words that are often used together to describe a single concept. See if there’s a way to combine them and create a single word that encompasses the meaning of both.

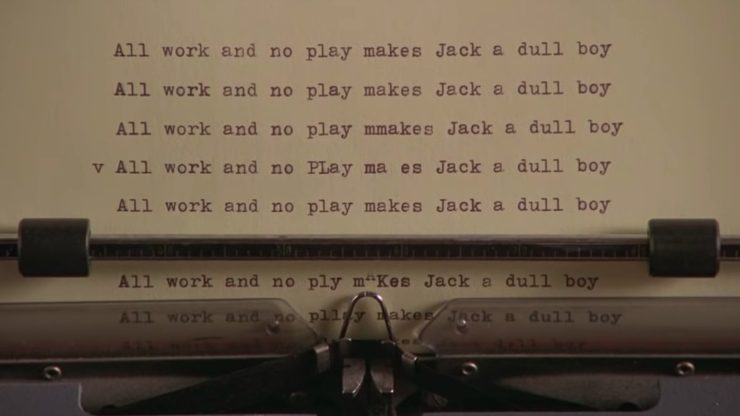

18. Repetition

Repetition , repetition, repetition… where would we be without it? Though too much repetition is rarely a good thing, occasional repetition can be used quite effectively to drill home a point, or to create a certain atmosphere. For example, horror writers often use repetition to make the reader feel trapped and scared.

Example: In The Shining , Jack Torrance types over and over again on his pages, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” In this case, obsessive repetition demonstrates the character’s unraveling mind.

Similar term: anaphora

Exercise: Repetition can be used to call attention to an idea or phrase. Pick an idea you want to emphasize and write a few sentences about it. Are there any places where you can add repetition to make it more impactful?

19. Tautology

A tautology is when a sentence or short paragraph repeats a word or phrase, expressing the same idea twice. Often, this is a sign that you should trim your work to remove the redundancy (such as “frozen ice”) but can also be used for poetic emphasis.

Example: "But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping, And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door" – “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

20. Tmesis

Tmesis is when a word or phrase is broken up by an interjecting word, such as abso-freaking-lutely. It’s used to draw out and emphasize the idea, often with a humorous or sarcastic slant.

Example: "This is not Romeo, he's some-other-where." – Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

21. Allegory

An allegory is a type of narrative that uses characters and plot to depict abstract ideas and themes . In an allegorical story, things represent more than they appear to on the surface. Many children's fables, such as The Tortoise and the Hare , are simple allegories about morality — but allegories can also be dark, complex, and controversial.

Example: Animal Farm by George Orwell. This dystopian novella is one of modern literature’s best-known allegories. A commentary on the events leading up to Stalin's rise and the formation of the Soviet Union, the pigs at the heart of the novel represent figures such as Stalin, Trotsky, and Molotov.

Exercise: Pick a major trend or problem in the world and consider what defines it. Try and create a story where that trend plays out on a smaller scale.

22. Anecdote

An anecdote is like a short story within a story. Sometimes, they are incredibly short—only a line or two—and their purpose is to add a character’s perspective, knowledge, or experience to a situation. They can be inspirational, humorous, or be used to inspire actions in others. Since anecdotes are so short, don’t expect them to be part of a main story. They’re usually told by a character and part of the dialogue.

Example: Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way , part of his series of novels, In Search of Lost Time, deals with the themes of remembrance and memory. In one section of this book, to illustrate these ideas, the main character recalls an important memory of eating a madeleine cookie. “Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, save what was comprised in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent out for one of those short, plump little cakes called ‘petites madeleines,’ which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted scallop of a pilgrim’s shell.”

23. Deus Ex Machina

Literally meaning “god in the machine” in Greek, deus ex machina is a plot device where an impossible situation is solved by the appearance of an unexpected or unheard of character, action, object, or event. This brings about a quick and usually happy resolution for a story and can be used to surprise an audience, provide comic relief, or provide a fix for a complicated plot. However, deus ex machinas aren’t always looked upon favorably and can sometimes be seen as lazy writing, so they should be used sparingly and with great thought.

Example: William Golding’s famous novel of a group of British boys marooned on a desert island is resolved with a deus ex machina. At the climax of The Lord of the Flies, just as Ralph is about to be killed by Jack, a naval officer arrives to rescue the boys and bring them back to civilization. It’s an altogether unexpected and bloodless ending for a story about the boys’ descent into savagery.

Exercise: Consider the ending of your favorite book or movie and then write an alternate ending that uses a deus ex machina to resolve the main conflict. How does this affect the overall story in terms of theme and tone?

If you struggle to write consistently, sign up for our How to Write a Novel course to finish a novel in just 3 months.

NEW REEDSY COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

24. Dramatic irony

Dramatic irony is when the readers know more about the situation going on than at least one of the characters involved. This creates a difference between the ways the audience and the characters perceive unfolding events. For instance, if we know that one character is having an affair, when that character speaks to their spouse, we will pick up on the lies and double-meanings of their words, while the spouse may take them at face value.

Example: In Titanic , the audience knows from the beginning of the movie that the boat will sink. This creates wry humor when characters remark on the safety of the ship.

25. Exposition

Exposition is when the narrative provides background information in order to help the reader understand what’s going on. When used in conjunction with description and dialogue, this literary device provides a richer understanding of the characters, setting, and events. Be careful, though — too much exposition will quickly become boring, thus undercutting the emotional impact of your work.

Example: “The Dursley’s had everything they wanted, but they also had a secret, and their greatest fear was that somebody would discover it.” – Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling

Exercise: Pick your favorite story and write a short paragraph introducing it to someone who knows nothing about it.

26. Flashback

Flashbacks to previous events split up present-day scenes in a story, usually to build suspense toward a big reveal. Flashbacks are also an interesting way to present exposition for your story, gradually revealing to the reader what happened in the past.

Example: Every other chapter in the first part of Gone Girl is a flashback, with Amy’s old diary entries describing her relationship with her husband before she disappeared.

Similar term: foreshadowing

27. Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is when the author hints at events yet to come in a story. Similar to flashbacks (and often used in conjunction with them), this technique is also used to create tension or suspense — giving readers just enough breadcrumbs to keep them hungry for more.

Example: One popular method of foreshadowing is through partial reveals — the narrator leaves out key facts to prompt readers’ curiosity. Jeffrey Eugenides does this in The Virgin Suicides : “On the morning the last Lisbon daughter took her turn at suicide — it was Mary this time, and sleeping pills, like Therese, the two paramedics arrived at the house knowing exactly where the knife drawer was, and the gas oven, and the beam in the basement from which it was possible to tie a rope.”

Similar term: flashback

Exercise: Go back to your favorite book or movie. Can you identify any instances of foreshadowing in the early portions of the story for events that happen in the future?

28. Frame story

A frame story is any part of the story that "frames" another part of it, such as one character telling another about their past, or someone uncovering a diary or a series of news articles that then tell the readers what happened. Since the frame story supports the rest of the plot, it is mainly used at the beginning and the end of the narrative, or in small interludes between chapters or short stories.

Example: In The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss, Kvothe is telling Chronicler the story of his life over the span of three days. Most of the novel is the story he is telling, while the frame is any part that takes place in the inn.

29. In Medias Res

In medias res is a Latin term that means "in the midst of things" and is a way of starting a narrative without exposition or contextual information. It launches straight into a scene or action that is already unfolding.

Example: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” — The opening line of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

Exercise: Pick a story you enjoy and rewrite the opening scene so that it starts in the middle of the story.

30. Point of view

Point of view is, of course, the mode of narration in a story. There are many POVs an author can choose, and each one will have a different impact on the reading experience.

Example: Second person POV is uncommon because it directly addresses the reader — not an easy narrative style to pull off. One popular novel that manages to employ this perspective successfully is Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney: “You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning. But here you are, and you cannot say that the terrain is entirely unfamiliar, although the details are fuzzy.”

Exercise: Write a short passage in either first, second, or third person. Then rewrite that passage in the other two points of view, only changing the pronouns. How does the change in POV affect the tone and feel of the story?

FREE COURSE

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

31. Soliloquy

Soliloquy involves a character speaking their thoughts aloud, usually at length (and often in a Shakespeare play). The character in question may be alone or in the company of others, but they’re not speaking for the benefit of other people; the purpose of a soliloquy is for a character to reflect independently.

Example: Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” speech, in which he ruminates on the nature of life and death, is a classic dramatic soliloquy.

Exercise: Pick a character from your favorite book or movie and write a soliloquy from their point of view where they consider their thoughts and feelings on an important part of their story or character arc.

Which writing app is right for you?

Find out here! Takes 30 seconds

Tone refers to the overall mood and message of your book. It’s established through a variety of means, including voice, characterization, symbolism, and themes. Tone sets the feelings you want your readers to take away from the story.

Example: No matter how serious things get in The Good Place , there is always a chance for a character to redeem themselves by improving their behavior. The tone remains hopeful for the future of humanity in the face of overwhelming odds.

Exercise: Write a short paragraph in an upbeat tone. Now using the same situation you came up with, rewrite that passage in a darker or sadder tone.

33. Tragicomedy

Tragicomedy is just what it sounds like: a blend of tragedy and comedy. Tragicomedy helps an audience process darker themes by allowing them to laugh at the situation even when circumstances are bleak.

Example: Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events uses wordplay, absurd situations, and over-the-top characters to provide humor in an otherwise tragic story.

34. Allusion

An allusion is a reference to a person, place, thing, concept, or other literary work that a reader is likely to recognize. A lot of meaning can be packed into an allusion and it’s often used to add depth to a story. Many works of classic Western literature will use allusions to the Bible to expand on or criticize the morals of their time.

Example: “The two knitting women increase his anxiety by gazing at him and all the other sailors with knowing unconcern. Their eerie looks suggest that they know what will happen (the men dying), yet don’t care.” The two women knitting in this passage from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness are a reference to the Fates from Greek mythology, who decide the fate of humanity by spinning and cutting the threads of life.

Exercise: In a relatively simple piece of writing, see how many times you can use allusions. Go completely crazy. Once you’re finished, try to cut it down to a more reasonable amount and watch for how it creates deeper meaning in your piece.

35. Analogy